Abstract

Purpose.

In this secondary analysis we tested whether 12 hours of Senior WISE (Wisdom Is Simply Exploration) memory or health training with older adults would produce better outcomes by gender in perceptions of anxiety and bodily pain and whether the effects of the Senior WISE training on pain were mediated by anxiety.

Design.

An implemented Phase III randomized clinical trial with follow up for 24 months in Central Texas. The sample was mostly female (79%), 71% Caucasian, 17% Hispanic, and 12% African American with an average age of 75 and 13 years of education.

Results.

The effects of the memory intervention on anxiety were consistent across time, with effects present for males but not females at post-treatment and end-of-study. Although males had more anxiety in the health promotion group, the memory training reduced males’ anxiety such that no gender difference was present in this group. The Senior WISE intervention reduced pain for both males and females at post-intervention but not at end-of-study. Although gender differences did not depend on the treatment group for pain, females reported somewhat, but not significantly, less pain at post-treatment and end-of-study. Mediation analysis indicated that, for males, the memory intervention indirectly affected pain at post-treatment, in part, by reducing anxiety, which lowered pain. However, at end-of-study, no indirect effect was present. Males responded to memory training. Training tailored to gender may increase the efficacy of the programs and “buy-in” from male participants, especially if tailored to anxiety and pain.

Keywords: Memory Training, Psychosocial Intervention, Gender differences, Trait Anxiety, Bodily Pain

Background

In 2018, 52 million people age 65 and older lived in the United States, and the population of this group grew from 12.4% in 2000 to 16.0% in 2018 (Census Bureau’s Vintage Population Estimates, 2019). An estimated 65% of US adults over the age of 65 reported suffering from some level of pain and up to 30% of older adults reported suffering from chronic pain with arthritis and back or neck pain being the most prevalent painful conditions (Dahlhamer, Lucas, Zelaya, et al. (2018).

A review of clinical and pre-clinical research found that pain was associated with cognitive impairment and neuroplastic changes (Moriarty, McGuire, Finn. 2011). Individuals with chronic pain demonstrated worse memory performance (Berryman, Stanton, Bowering, Tabor, McFarlane, & Lorimer, 2013), and brain volume loss (Buckalew, Haut, Morrow, & Weiner, 2008). Declining memory performance was also associated with anxiety and depression (Dux et al., 2008; Fiocco, Wan, Weekes, Pim, & Lupien, 2006). Among older adults with cognitive impairment, pain interference and depression severity were under reported (Wang, Dietrich, Simmons, Cowan, & Monroe, 2018). Similarly, higher levels of pain interference were associated with a higher risk of dementia (Ezzati, Wang, Katz, Derby, Zammit, et al. 2019). In the Einstein longitudinal aging study, participants (N=1,114), 70 years of age or older, evaluated pain intensity and interference with the SF-36. Those who experienced high levels of pain as assessed by the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) pain severity scale, developed memory impairment at higher levels compared with individuals who had lower levels of pain (van der Leeuw, Ayers, Leveille, Blankenstein, van der Horst, & Verghese, 2019).

The International Association for the Study of Pain’s (IASP) definition of pain was recently updated to “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage” (IASP, 2011; Raja, Carr, Cohen, Finer,. et al. 2020). While the IASP definition of pain is likely the most widely accepted and used in clinical and research practice, the critical point is that the definition relies on self-report of pain, which is considered the gold standard for assessment.

The Biopsychosocial Model of Pain introduced to healing professions the notion that pain and disability are dynamic interactions among physiological, psychological, and social factors (Engel, 1977). Multiple psychosocial factors contribute to the pain experience, such as anxiety, stress, attitudes, beliefs, employment/occupation, lifestyle, physical activity, and catastrophizing (Edwards, Dworkin, Sullivan, Turk & Wasan, 2016; Mills, Nicolson, Smith, 2019). In middle-aged adults, anxiety disorder and a co-morbid depressive, are associated with significantly greater disabling musculoskeletal pain (de Heer, Gerrits, Beekman, Dekker, van Marwijk, et al. 2014). Other unique aspects of the pain experience include gender and age differences. Compared to males, women living with chronic pain reported pain more frequently and with greater intensity (Fillingim, King, Ribeiro-Dasilva, Rahim-Williams, & Riley, 2009).

Interestingly, a pilot study that examined experimental thermal pain across the cognitive spectrum demonstrated that females reported pain as more intense however males reported pain as more unpleasant (Romano, Anderson, Failla, Dietrich, Atalla, et al. 2019). Therefore, the experience of pain is personal and characterized by individual differences (Fillingim, 2017). Given the importance of psychosocial factors related to pain in older adults, non-pharmacological interventions hold great promise for managing pain and was the premise for this study.

Psychosocial Interventions to Assist with Pain Management

Psychosocial interventions, such as Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT), Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), Mindfulness-Based interventions (MBI) stress reduction provide non-pharmacological methods for managing persistent pain in older adults (Bevers, Brecht, Jones, & Gatchel, 2018; Keefe, Porter, Somers, Shelby, & Wren, 2013; Veehof, Trompetter, Bohlmeijer, Schreurs, 2016). Implementation concerns with these therapies are problematic, and brief interventions were considered an adaption to enhance the treatments. These brief versions are categorized if they consist of two and less than ten sessions (Cape, Whittington, Buszewicz, Wallace, & Underwood, 2010).

In CBT, the emphasis is changing thought content such as catastrophizing cognitions. After meta-analyzing forty-two studies that met criteria with 4788 participants, CBT had weak effects for improving pain, but was effective in altering mood and reducing catastrophizing outcomes, when compared with treatment as usual/waiting list and was maintained at six months Williams, Eccleston, & Morley, 2012).

The philosophy guiding ACT therapy emphasizes psychological flexibility such that painful sensations, feelings, and thoughts are accepted, attention is focused on the opportunities of the current situations rather than on ruminating or catastrophizing, and behavior is focused on realizing valued goals instead of pain control (McCracken & Vowles, 2014).

In MBI, formal meditation is the primary emphasis of the intervention. Mindfulness is intentional and non-judgmental awareness (Turner, Holtzman, & Mancl, 2007). Although these integrative therapies are gaining in acceptance by both patients and providers, they are moderately effective. A review of five RCTs of MBI of stress reduction with family caregivers (N=201) of relatives with dementia (Liu, Sun, & Zhong, 2018) found that after completing the intervention, the caregivers had short term reduced anxiety and depressive symptoms. An RCT of a brief 15-minute MBI for 71 older adults with persistent pain found no significant intervention effects (Juul, Pallesen, Bjerggaard, Fjorback, 2020). A recent meta-analysis of 30 randomized controlled trials (RCT) found that mindfulness meditation significantly lowered the depression scores and symptoms and moderate improvements for mental health-related quality of life. Only four studies reported use of analgesics and there were reductions in the short term, but not at three months. However, the intervention was associated with a small effect of improved pain (Hilton, Hempel, Ewing, Apaydin, Xenakis et al., 2017).

Notably, psychosocial interventions did not target cognitive decline and other cognitive issues associated with pain and anxiety in older adults. Therefore, the purpose of this secondary analysis study was to determine if memory training (MT) and/or health training (HT) affected pain in cognitively intact older adults without dementia and whether effects varied by gender and anxiety level.

Research Questions

Are there gender differences in anxiety and pain in community residing older adults in a memory or health training intervention study?

Does the memory or health intervention affect pain at post-treatment and end-of-study for males and females?

What are the effects of the interventions on bodily pain mediated by trait anxiety for males and females?

Methods

Design.

This original Senior WISE (Wisdom Is Simply Exploration) study was a Phase III RCT with longitudinal follow up over 24 months (McDougall, Becker, Vaughan, et al., 2010). We tested the efficacy of a memory intervention against health promotion training. The classes were presented in 8 sessions that met twice a week for 1.5 hours each. Participants were post tested within two weeks after completing the 12 hours of training. Three months later the groups attended 4 booster classes, 2-hours each session, once a week over a month. All cognitive and self-report measures were administered at each measurement occasion, first at baseline, following the screening and eligibility, next, at post-class (2-months after baseline), again at post-booster (6-months), then at post-classroom follow-up (14-months), and end of study (26-months).

Participants.

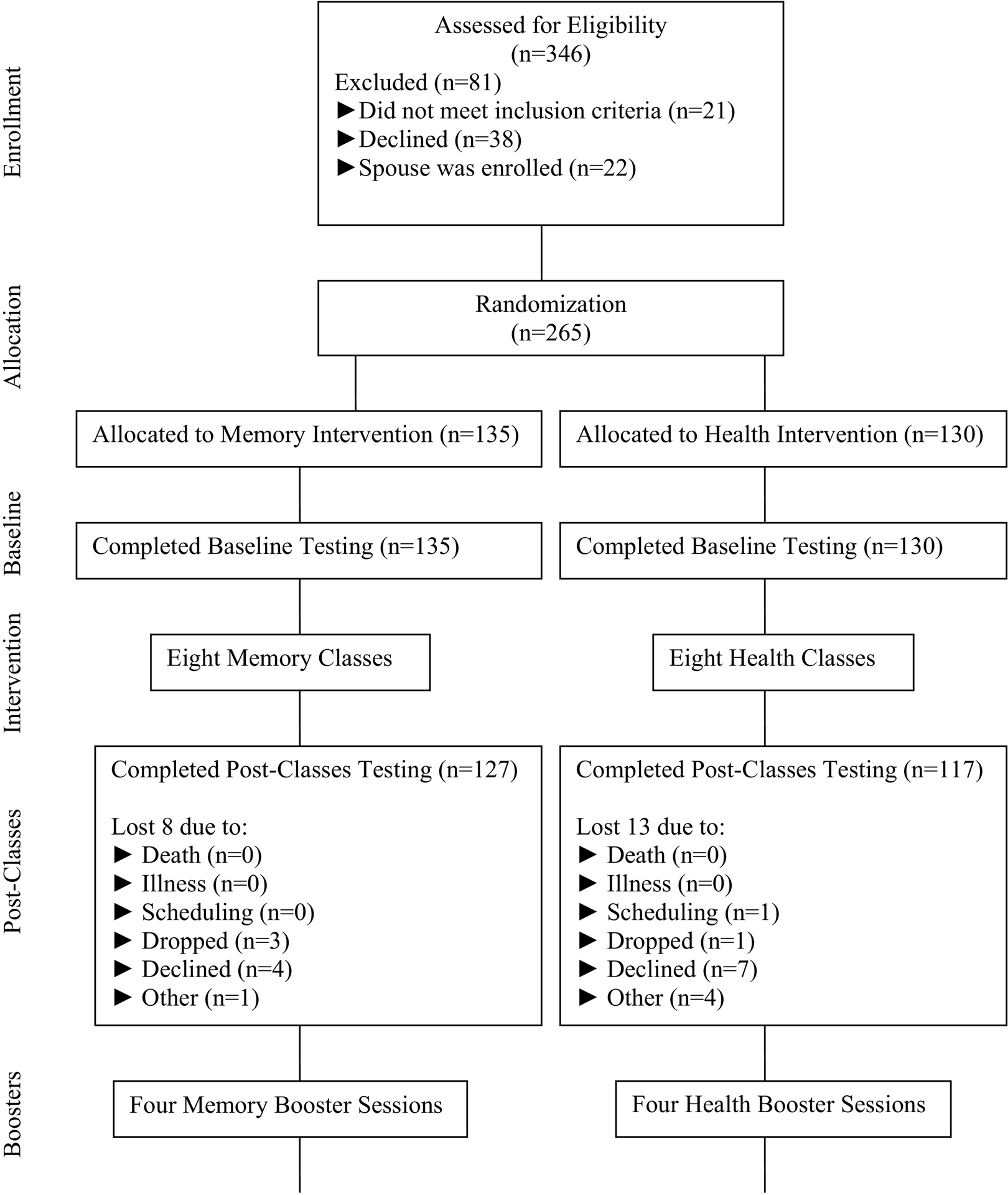

A total of 346 adults were recruited from a metropolitan area in Central Texas via print and TV media, as well as direct recruitment at city-run senior activity centers, churches, health fairs and festivals (Figure 1). The university’s Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart.

Power Analysis.

With an alpha level of .05 for analysis with each dependent measure and an effect size of .37, a sample size of 84 subjects would be needed to yield a power level of .80 for a one sample repeated measures design (Elashoff, 1997). Therefore, it was estimated that 84 subjects were required for each of the two groups (experimental and comparison) in the proposed study. The overall sample size of 168 was sufficient for the multiple regression analysis and would yield a power of .90 for a multiple regression analysis with 15 predictor variables, a cumulative r2 of .15 and an alpha level of .025.

Screening and Eligibility.

Sensory loss was determined either over the telephone or in person by a self-report evaluation of hearing and vision. Visual and hearing acuity were subsequently evaluated at the “in-person” eligibility screening by evaluator observation and by a self-report checklist developed for this study. Communication was assessed using a 7-item checklist designed for this study and completed by a member of the Team at the initial screening. Other eligibility criteria included age (≥65), ability to speak and understand English, and willingness to participate in the study for 24 months. Diagnoses that precluded people from participating in the study included: Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia, Hodgkin’s disease, neuroblastoma or cancer of the liver, and lung or brain. Medical eligibility was assessed verbally at screening using a Health Status checklist designed for this project. Testing with the Hispanic elders often occurred over many days to accommodate their literacy skills and their frustration with the complex battery of measures. It is possible that practice effects were sometimes greater for Blacks and Hispanics.

Cognitive Screening Variables.

The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975) was used to screen for cognitive impairment. The MMSE was also used to monitor potential cognitive decline throughout the longitudinal study. Subjects with scores >23 participated in the study. However, the eligibility score was changed to ≥20 to recruit Hispanics at all locations that served Hispanic adults. We did not lower MMSE scores for Hispanics to increase the sample size. We evaluated baseline scores for the MMSE by ethnicity.

The minimum values suggested that the cut score of 20 was applied uniformly across all individuals, regardless of ethnicity. However, when the MMSE is used for cognitive screening with individuals who have lower education, e.g., less than eighth grade, the sensitivity and specificity are reduced and adjusted scores are needed to avoid misclassifying someone as cognitively impaired (Matallana, Santacruz, Cano et al 2011).

The Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT) from the Multilingual Aphasia Examination (Sumerall, Timmons, James, Ewing, & Oehlert, 1997) and The Trail-Making Test were administered (Reitan, 1958). Participants were required to pass Trails A and/or Trails B at or above the 10th percentile for their age group for inclusion in the study.

Interventions.

The MT intervention was based on self-efficacy theory. Self-efficacy is the belief in one’s ability to execute as plan and complete a task successfully, thereby achieving a goal (Bandura, 2012). General self-efficacy refers to our overall belief in our ability to succeed, but there are many domain specific measures, such as memory self-efficacy. The Senior WISE intervention had two components: The first component was mindfulness-based stress reduction techniques including relaxation and stress inoculation, were taught, demonstrated, and practiced during the first 20–30 minutes at the beginning of each session. Participants learned to cope with anxiety linked to both general stressful situations and testing via the use of cognitive behavioral techniques.

Next, participants received memory strategy training which included, internal external strategy use, and other mnemonic techniques. Managing false beliefs about cognitive aging was included throughout the sessions., During the exercises, the participants received additional feedback for practice and homework. All sessions were delivered with Power Point slides. The trainer of the MT was a septuagenarian psychologist, and the HT was led by a middle-aged male who was not a professional health care provider. Implementation of the memory training intervention was designed to ensure treatment fidelity in the three areas of delivery, receipt, and enactment, as recommended by the Consortium guidelines proposed by Bellg and colleagues (2004).

The HT intervention consisted of eighteen different health promotion topics, which emphasized successful aging. The various topics included alternative medicine, sleep, depression, and many more of interest to older adults. Memory and/or cognitions was not discussed on any of the PowerPoint slides (McDougall & Becker, 2010). These topics were developed after conducting three focus groups in the community with diverse older adults before the recruitment began for the clinical trial (Austin-Wells, Zimmerman, & McDougall, 2003).

Demographic Measures

The demographic measures included age and education in years and gender. Race variable included the categories of White, Black, and Hispanic to reflect the triethnic sample. Marital status included the four categories of married, never married, divorced, and widowed. We also inquired about financial status as both a categorical variable with six choices as well as reporting the 6 choices as a frequency count from 1–6.

Performance Measures

Verbal Memory.

This memory task was tested with the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (HVLT-R), which assessed immediate recall, delayed recall, and recognition memory (Brandt, 1991). Each form consists of a list of 12 nouns (targets) with four words drawn from each of three semantic categories. Test/retest correlation was .66 for the Delayed Recall Subscale, which was used in these data analyses.

Visual Memory.

The Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised (BVMT-R), measured visual memory by reproducing a series of geometric designs (Benedict, 1997). Items include six equivalent; alternate stimulus forms consist of six geometric figures printed in a 2 × 3 array on separate pages. Reliability coefficients ranged from .96 to .97 for the three Learning trials, .97 for Total Recall, and .97 for Delayed Recall. Test-retest reliability coefficients ranged from .60 for Trial 1 to .84 for Trial 3. The BVMT-R correlated most strongly with other tests of visual memory and less strongly with tests of verbal memory.

Episodic Memory.

The Rivermead Behavioral memory Test (RBMT) test bridges laboratory-based measures of memory and assessments obtained by self-report and observation (Cockburn & Smith, 1989). The test components are remembering a name (first and surname), hidden belonging, appointment, picture recognition, newspaper article, face recognition, new route (immediate), new route (delayed), message, orientation, and date. The standardized profile score (SPS) has a range from 0–24 and is sometimes interpreted with regard to cut-off points for four groups of memory function: normal (22–24), poor memory (17–21), moderately impaired (10–16), and severely impaired memory (0–9). Alpha reliability was .73.

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs).

The Direct Assessment of Functional Status (DAFS), measures performance in test time orientation, communication abilities, transportation, financial skills, shopping skills, eating skills and dressing/grooming skills (Loewenstein et al., 1989; 1992). The DAFS has demonstrated high interrater and test-retest reliabilities for both patients presenting to a memory disorder clinic (English and Spanish speaking) and for normal controls. Participants were given a task, such as making change and were required to demonstrate competency on the task. Scoring is based on the protocol reported in the protocol manual (McDowd, Hafia Han, McDougall, 2010). Alpha reliability was .79.

Self-Report Measures

Health.

Besides using a psychometric measure of health, we were interested in other factors that may influence bodily pain. We asked participants to check whether they lived with adverse symptoms, such as anxiety, depression, dizziness, nerve damage or neuropathy, a total of 30 symptoms that may lead to bodily pain. Observed scores ranged from 0–9. We also included drinking alcohol and smoking as a choice of --Yes or No.

Bodily Pain.

The Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 (SF-36) is a self-report measure of health and function, to collect patients’ views of their health status (Fleishman, Cohen, Manning, & Kosinski, 2006; McHorney, 1996; McHorney, Ware, Raczek, 1993). The scale measures health related quality of life usually over the previous week. The items and scales on the SF-36 are scored so that a higher score indicates a better health state. The Bodily Pain scale (i.e., “How much bodily pain have you had during the past 4 weeks”) is scored so that a high score indicates freedom from pain. The items use Likert-type scales, some with 5 or 6 points and others with 2 or 3 points. Alpha reliability was .863.

State-Trait Anxiety.

The Spielberger Anxiety Inventory (STAI) measured both state and trait anxiety and was developed for the expressed purpose of detecting anxiety in adults (Spielberger, Gorsuch, & Lushene, 1970) and to differentiate between the temporary condition of “state anxiety” and the chronic condition of “trait anxiety.” We used state anxiety to measure anxiety changes over time. Alpha reliability was .853 and .893.

Depressive Symptoms.

The Centers for Epidemiologic Studies Scale (CES-D) evaluated depressive symptoms (Radloff & Teri, 1986). Somatic complaints were emphasized on this measure and individuals responded on a 4-point Likert scale. Reliability coefficients from .85 to .91 have been obtained when the CES-D was used with older adults. Alpha reliability was .776.

Data Randomization and Treatment Fidelity

Once participants were screened and consented, randomization occurred using Excel to randomly assign participants’ numeric codes to either the experimental or the comparison condition. There were 7 different community sites consisting of 11 different randomly assigned groups within the sites. The group membership was community residing older adults. Regardless of the group assignment, memory or health, each group participated in twelve classroom experiences. The dose of the intervention was attendance at six of eight classes. One hundred thirty-five individuals were assigned to the memory intervention and 130 were assigned to the health promotion groups. No class was smaller than 4 individuals or larger than 15; however, we strove for an average class size of 12 individuals. Classes were purposely designed for multiple interactions, practice, and feedback.

Treatment fidelity was maintained in two ways. First, there was always one observer in the classroom to track individual’s performance and mastery on practice activities. The observer debriefed with the instructor and pointed out areas that need to be reviewed in the next session to prevent the development of poor habits. Second, after each class, each participant wrote down some aspect of the learning, or essential point for the day such as a memory strategy. The individual participant was given either a plus or minus (0, 1) for the class session. Between the 8-session CBMEM, and the 4-booster sessions, a participant would have a possible score between 0 and 12. Data from the classroom tests was utilized to determine relationships between classroom performance and memory mastery, post educational and booster sessions.

Analytic Approach

To assess if treatment group and gender differences were present, we estimated a bivariate longitudinal model that simultaneously included anxiety and pain as outcomes for each of the post-treatment assessments. For each outcome, we included treatment, gender, and the gender-by-treatment product term, along with covariates baseline pain, anxiety, smoking status, number of adverse health conditions, drinking status, and finance. The effect of each predictor was different at each time point. For the mediation analysis, we used the same models but added anxiety assessed at post-treatment as a predictor of pain. To account for the clustered nature of the study design (i.e., study participants located in each of 11 locations), we used a “fixed-effects model” approach, in which 10 dummy-coded variables representing location were included as predictors in the model. The fixed-effect approach provided for accurate parameter estimates and statistical inference in designs having a small number of clusters (McNeish & Stapleton, 2016).

Of the 265 cases in the final sample, 3 cases were removed because they had missing values on the predictor. For the remaining 262 cases, we used a maximum likelihood procedure (i.e., MLR), implemented in Mplus (Version 8.4; Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017), which used information from all cases except those not providing responses to any of the repeated measures (resulting in an analytic sample size of 242). This procedure was robust to violations of normality and provides for optimal parameter estimates when response data were incomplete (Enders & Bandalos, 2001; Savalei, 2010). The z tests provided by Mplus with the robust standard errors were used to test all effects except for indirect effects, for which we used a percentile bootstrapping approach (with 10,000 bootstrap samples). Bootstrapping was a recommended method for mediation analysis given that indirect effects are non-normally distributed (Hayes, 2017; MacKinnon, 2008).

Results

The Results were reported according to the CONSORT guidelines. The number of participants at each phase of the trial is illustrated by the CONSORT diagram (see Figure 1). A total of 81 individuals were excluded, 21 did not meet inclusion criteria, 38 declined, and 22 were couples, of which the female spouse was excluded from the testing so that adequate numbers of males would be represented in the sample. The memory and health groups did not differ significantly at baseline on either the demographics or outcome measures (t-test). A total of 265 adults were randomized by site to the two conditions, of those 244 completed post testing after participating in the eight sessions. Of those who completed the study (M=209), there were no statistically significant differences in MMSE scores (M = 28.01 vs. 27.48). The proportional dropout for males (30%) was somewhat greater than for females (18.5%), however the difference in the dropout rate between males and females was not statistically significant.

Gender differences. Table 1 describes the demographic and study variables of the participants by gender and intervention group. In the health training group, the females were significantly (p = .02) older than males (75.51 versus 72.57). There was one significant (p < .01) gender difference in the cognitive measure of verbal memory in the memory training group with females at baseline scoring higher than males (49.89 versus 42.50). On the self-report measures in the health training group, females had significantly (p = .02) greater anxiety (33.10 versus 28.97) than males and had significantly more adverse health conditions (p < .01) (3.71 versus 2.47) than the males.

Table 1.

Demographics, Screening Measures, and Study Variables at Baseline by Treatment and Sex

| Comparison group (n = 130) | Intervention group (n = 135) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females (n = 100) | Males (n = 30) | Females (n = 105) | Males (n = 30) | ||||

| Variable | M ± SD or n (%) | M ± SD or n (%) | Pa | M ± SD or n (%) | M ± SD or n (%) | Pa | Pb |

| Demographics | |||||||

| Education | 13.59 ± 3.69 | 14.53 ± 3.78 | .22 | 13.11 ± 3.54 | 14.37 ± 4.89 | .12 | .37 |

| Race | .85 | .24 | .98 | ||||

| White | 70 (70.0) | 23 (76.7) | 78 (74.3) | 18 (60.0) | |||

| Black | 12 (12.0) | 3 (10.0) | 11 (10.5) | 4 (13.3) | |||

| Hispanic | 18 (18.0) | 4 (13.3) | 16 (15.2) | 8 (26.7) | |||

| Marital Status | < .01 | <.01 | .67 | ||||

| Married | 16 (16.0) | 21 (70.0) | 23 (22.1) | 22 (75.9) | |||

| Never married | 2 (2.0) | 1 (3.3) | 4 (3.8) | 1 (3.4) | |||

| Divorced | 22 (22.0) | 4 (13.3) | 22 (21.2) | 3 (10.3) | |||

| Widowed | 60 (60.0) | 4 (13.3) | 55 (52.9) | 3 (10.3) | |||

| Finances | |||||||

| Not enough for bills | 2 (2.0) | 0 (0) | .71 | 6 (5.8) | 1 (3.3) | .25 | .62 |

| Just enough for bills | 15 (15.0) | 2 (6.7) | 18 (17.3) | 1 (3.3) | |||

| Enough for bills and things | 17 (17.0) | 6 (20.0) | 21 (20.2) | 6 (20.0) | |||

| Enough for bills and outings | 18 (18.0) | 4 (13.3) | 11 (10.6) | 7 (23.3) | |||

| Enough for bills, things, and outings | 38 (38.0) | 13 (43.3) | 36 (34.6) | 12 (40.0) | |||

| Enough not to worry | 10 (10.0) | 5 (16.7) | 12 (11.5) | 3 (10.0) | |||

| Finances (6 point-scale) | 4.05 ± 1.32 | 4.43 ± 1.19 | .16 | 3.86 ±1.49 | 4.23 ±1.19 | .21 | .24 |

| Depression | 10.09 ± 7.18 | 7.4 ± 5.29 | .06 | 9.45 ± 6.52 | 8.00 ± 7.34 | .30 | .69 |

| Cognitive performance screening variables | |||||||

| Attention | 47.62 ± 41.02 | 38.63 ± 14.30 | .24 | 45.42 ± 33.01 | 43.33 ± 38.23 | .92 | .89 |

| Cognitive Flexibility | 135.20 ± 101.33 | 133.93 ± 90.71 | .95 | 126.97 ± 76.18 | 119.47 ± 68.02 | .47 | .37 |

| Organizational Strategy | 39.88 ± 10.93 | 42.90 ± 11.80 | .20 | 41.44 ± 11.75 | 40.67 ± 10.57 | .75 | .62 |

| Cognition | 27.87 ± 2.27 | 27.57 ± 2.14 | .52 | 28.08 ± 1.94 | 27.7 ± 2.37 | .38 | .46 |

| Visual Memory | 43.26 ± 14.99 | 40.50 ± 14.04 | .37 | 43.34 ± 13.90 | 39.87 ± 12.65 | .22 | .98 |

| Verbal Memory | 47.83 ± 11.12 | 43.37 ± 11.03 | .06 | 49.89 ± 9.95 | 42.50 ± 13.99 | < .01 | .30 |

| Everyday Memory | 18.02 ± 4.76 | 18.40 ± 3.64 | .69 | 18.86 ± 3.68 | 18.77 ± 3.65 | .91 | .15 |

| Instrumental Activities | 81.77 ± 6.27 | 81.00 ± 5.25 | .54 | 82.48 ± 4.48 | 82.00 ± 4.88 | .62 | .24 |

| Study outcomes and predictors | |||||||

| Anxiety | 33.10 ± 8.54 | 28.97 ± 7.90 | .02 | 32.63 ± 9.23 | 29.31 ± 8.92 | .09 | .82 |

| Pain | 71.14 ± 24.40 | 76.33 ± 22.07 | .30 | 72.13 ± 21.85 | 66.27 ± 25.75 | .22 | .60 |

| Age | 75.51 ± 6.33 | 72.57 ± 5.35 | .02 | 74.90 ± 5.74 | 73.97 ± 5.76 | .47 | .85 |

| Number of Adverse Symptoms | 3.71 ± 1.91 | 2.47 ± 1.91 | < .01 | 3.43 ± 2.19 | 2.33 ± 1.73 | .01 | .35 |

| Smoking status | .03 | .65 | .24 | ||||

| Yes | 6 (6.1) | 6 (20.0) | 5 (4.8) | 2 (6.7) | |||

| No | 93 (93.9) | 24 (80.0) | 100 (95.2) | 28 (93.3) | |||

| Drinking status | .15 | .10 | .81 | ||||

| Yes | 41 (41.4) | 17 (56.7) | 45 (42.9) | 18 (60.0) | |||

| No | 58 (58.6) | 13 (43.3) | 60 (57.1) | 12 (40.0) | |||

Note. Depression = CES-D; Attention = Trail-Making Test A; Cognitive Flexibility = Trail-Making Test B; Organizational Strategy = Controlled Oral Word Association; Cognition = MMSE; Visual Memory = Delayed recall T score from the BVMT-R; Verbal Memory = Delayed recall T score from the HVLT-R; Everyday Memory = Standard profile score from the RBMT; Instrumental Activities = DAFS.

Is the p value for the independent-samples t test, for numeric variables, or Fisher’s exact test, for categorical variables, assessing gender differences within each treatment group.

Is the p value for the independent-samples t test, for numeric variables, or Fisher’s exact test, for categorical variables, assessing treatment group differences.

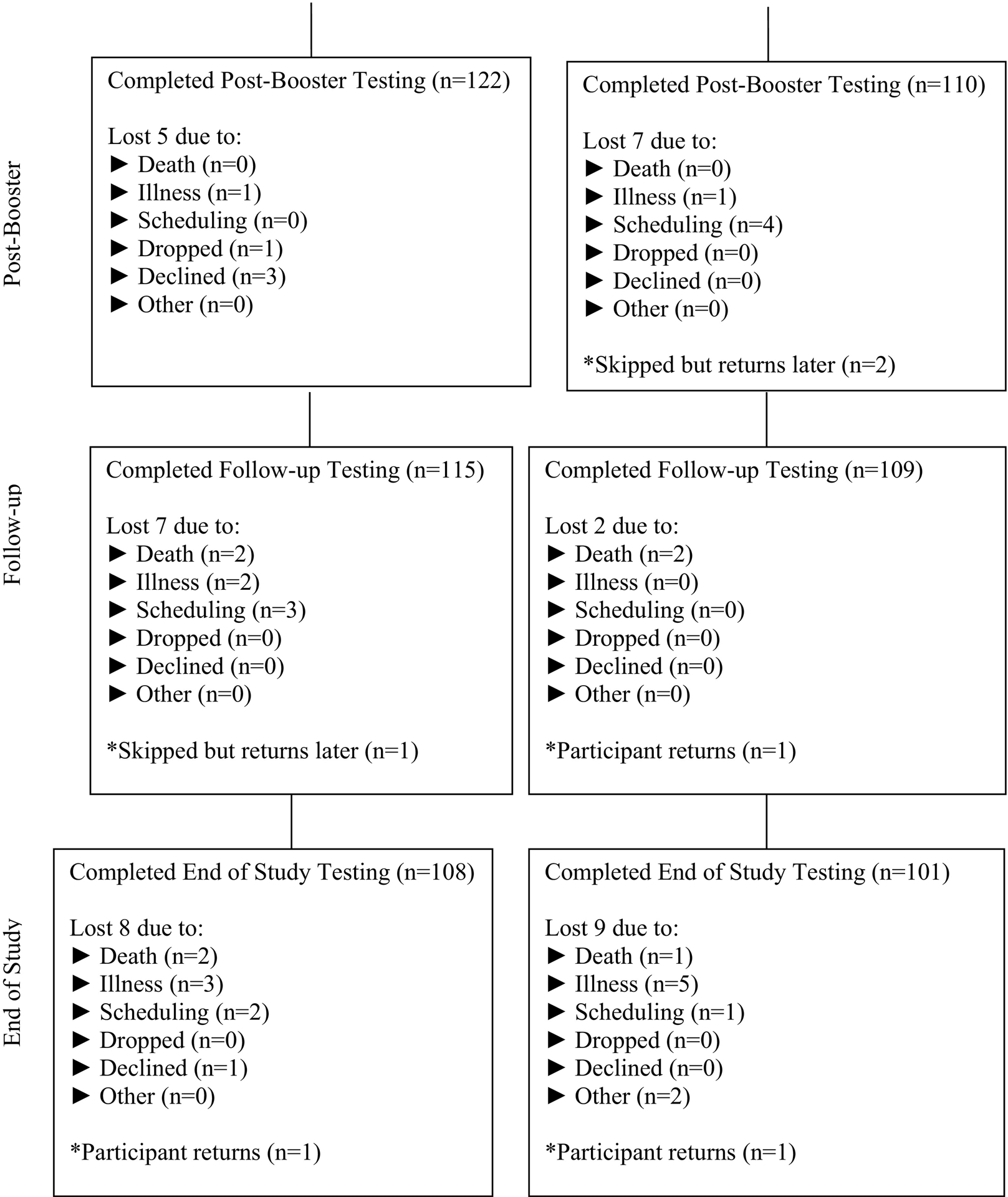

The bivariate longitudinal model initially estimated included treatment group-by-gender interactions for the pain and anxiety outcomes at each post-treatment assessment. Given that this interaction was not significant at post-treatment (p = .54) and end-of-study (p = .79) for pain, we removed this group-by-gender product term from the model for pain. Table 2 presented the results for the final longitudinal model for both outcomes at the post-treatment and end-of-study assessments. As shown in Table 2, the group-by-gender interaction was significant for anxiety at post-treatment (p < .01) and nearly so at end-of-study (p = .06), suggesting that, for anxiety, gender differences depend on treatment group. Table 2 shows that, in the HT group, post-treatment anxiety for females was 4.0 points, or 0.48 standard deviations, lower (p < .01) than for males. This difference is evident in Figure 2 where, at post-treatment, male anxiety was much greater than female anxiety in the HT group. Note that at post-treatment, the memory intervention reduced anxiety—particularly for males—such that the difference between females and males in the memory intervention group was small, at 0.56 points or 0.05 standard deviations, and not statistically significant (p = .52). At end-of-study, although males again had greater anxiety than females in the HT group (3.14 points or 0.32 standard deviations) and that males had lower anxiety than females in the MT group (1.79 points or 0.17 standard deviations), these differences were not significant at post-treatment (p = .15) or end-of-study (p = .23). For pain, as noted above, gender differences did not depend on treatment group. In addition, Table 2 shows that although females reported somewhat less pain, these gender differences were not statistically significant at post-treatment (p = .20) or end-of-study (p = .45).

Table 2.

Estimates from the Bivariate Longitudinal Regression Model for Anxiety and Pain

| Variable | Post-Treatment | Follow-up | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Pain | Anxiety | Pain | |

| Group | −5.39*** | 5.93* | −5.08* | 0.40 |

| Female | −4.01*** | 3.56 | −3.14 | 2.47 |

| Group*Female | 4.57** | -- | 4.93 | -- |

| Baseline Anxiety | 0.65*** | −.04 | 0.66*** | −0.31* |

| Baseline Pain | −0.02 | 0.50*** | 0.03 | 0.45*** |

| Age | 0.14** | 0.24 | 0.10 | 0.24 |

| Smoke | −3.99*** | 4.49 | −3.04* | −0.27 |

| Health Conditions | −0.28 | −1.51* | 0.69* | −2.27** |

| Drink | −0.70 | −0.33 | −2.25* | −1.51 |

| Finance | −0.51 | −0.12 | 0.28 | −1.12 |

| R2 | 0.58*** | 0.35*** | 0.47*** | 0.34*** |

N = 241.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Note: Group is coded as 1 = memory intervention; 0 = health training; Female is coded as 1 = female and 0 = male; Smoke is coded as 1 = smoke and 0 = otherwise; Drink is coded as 1 = drink and 0 = otherwise.

Figure 2.

Post-Treatment and End-of-Study Anxiety Means by Treatment and Gender.

Given the group-by-gender interaction noted above for anxiety, the impact of the memory intervention on anxiety depended on gender. Specifically, Table 2 showed that—for males—the memory intervention reduced anxiety by 5.4 points (p < .001) and 5.1 points (p =.03) at post-treatment and end-of-study, respectively. These mean differences, when divided by the anxiety standard deviations at their respective time point, represent treatment group differences of 0.64 and 0.51 standard deviations. In contrast, for females, no treatment group difference was present as the memory intervention reduced anxiety at post-treatment by just 0.82 points, or 0.10 standard deviations (p = .32) and by 0.14 points, or 0.02 standard deviations, at end-of-study (p = .90). Figure 2 displays the anxiety means, adjusted by the covariates, by treatment group, gender, and assessment period. Small group differences for females are depicted in Figure 2 by the solid and nearly flat lines, whereas anxiety group differences for males are depicted by the downwardly sloping dashed lines reflecting significantly decreased anxiety in the memory group at each of the 2 time points. For the covariates, Table 2 also shows that those with less baseline anxiety as well as those who smoke reported less anxiety at post-treatment and end-of-study. Further, at post-treatment only, older participants reported greater anxiety, and, at end-of study only, those who reported that they drink alcohol reported less anxiety than non-drinkers whereas those who reported a greater number of adverse health conditions reported greater anxiety.

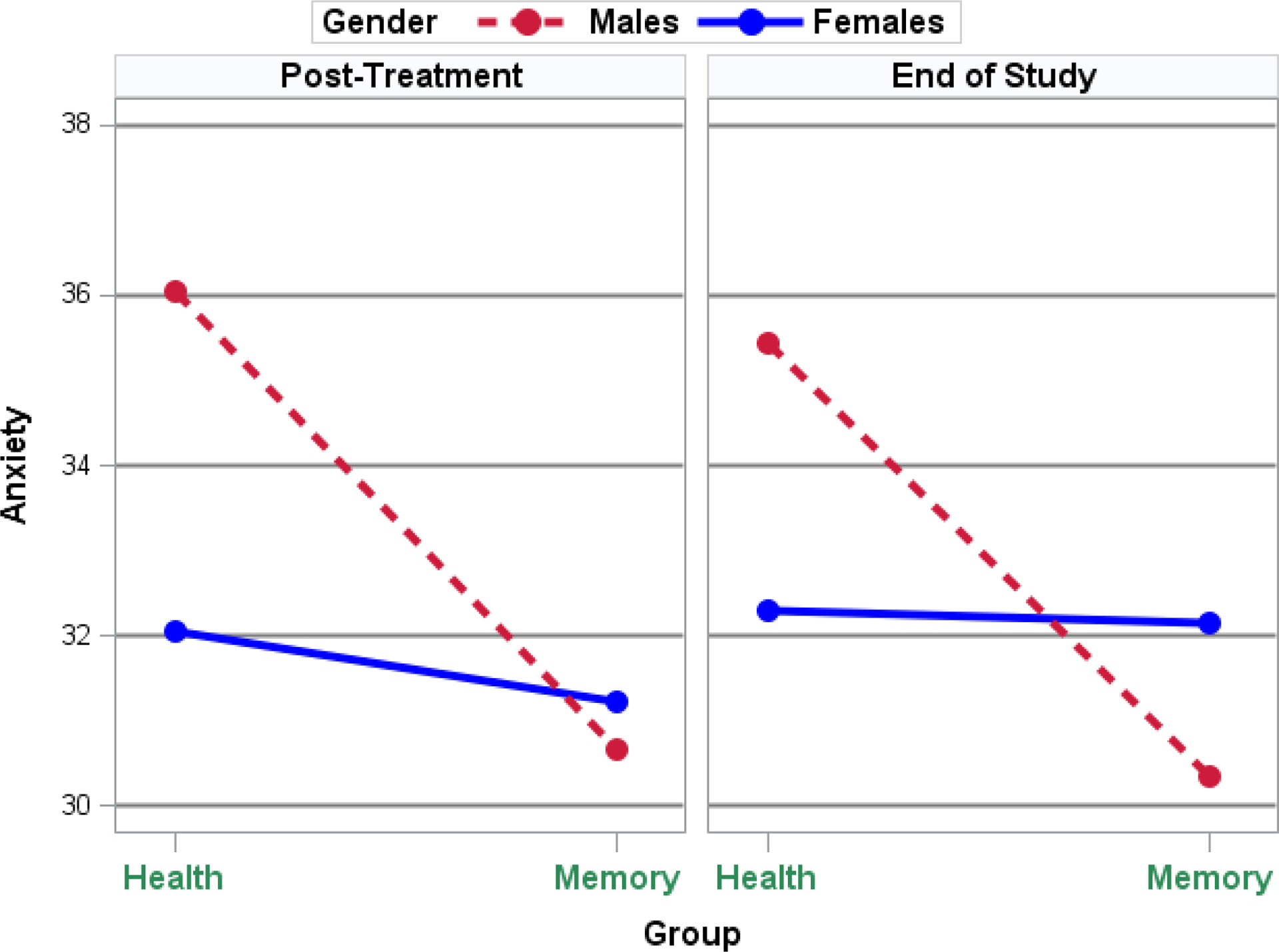

For pain, Table 2 shows that participants in the memory intervention, on average, reported approximately 6 points (p = .02), or 0.26 standard deviations, less pain than those in the HT group. However, at end-of-study, no treatment group mean difference was present. Figure 3 shows these adjusted pain means for the 2 groups at each of the time periods where the sharply sloping line at post-treatment represents significantly less pain for the memory group (as higher scores represent less pain) and the relatively flat line at end-of-study indicates no group difference. Table 2 also shows that those with greater pain at baseline and those with more adverse health conditions reported greater pain at post-treatment and end-of-study. In addition, at end-of-study only, those with greater baseline anxiety reported greater pain.

Figure 3.

Adjusted Pain Means by Time and Treatment Group.

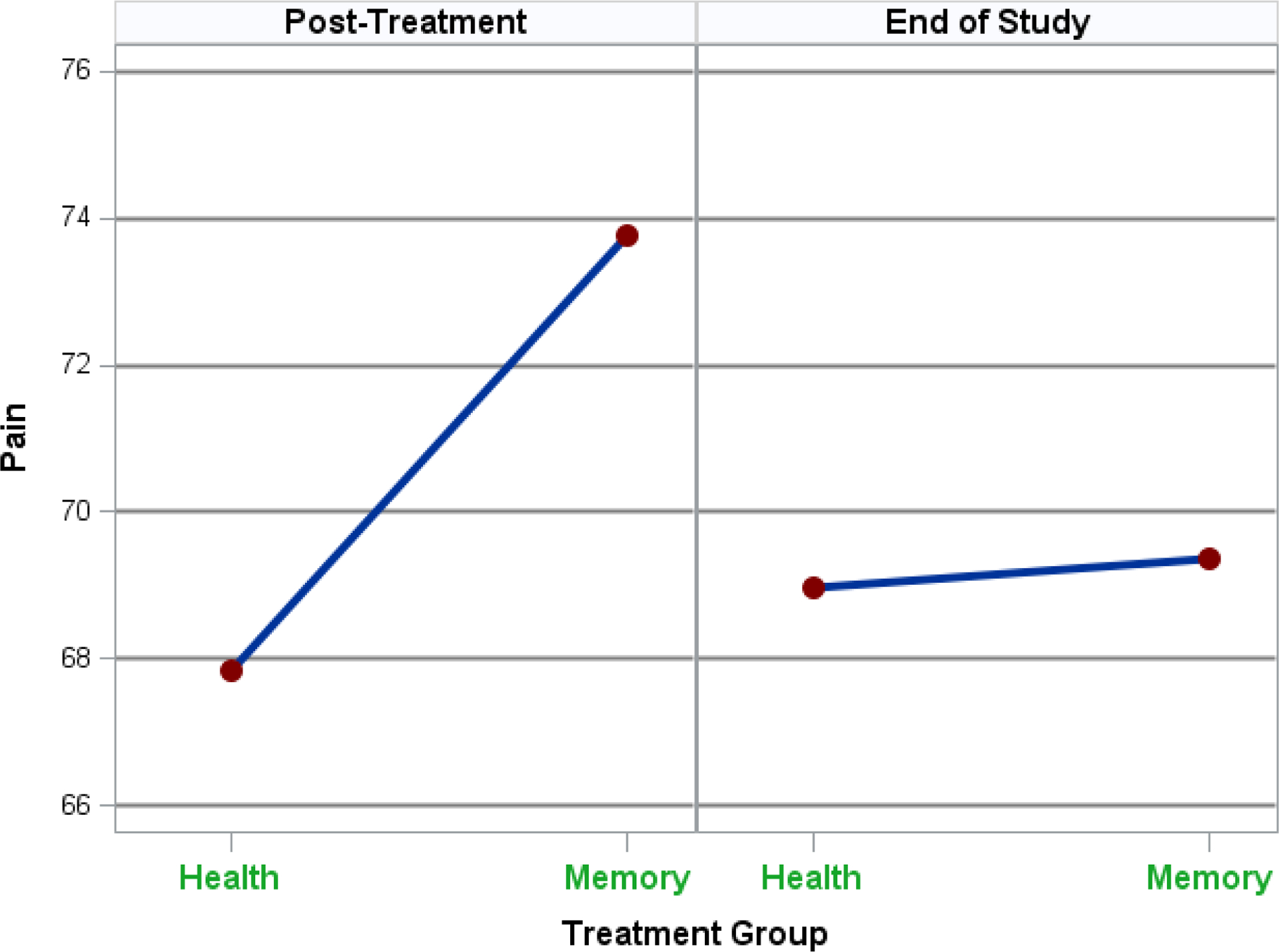

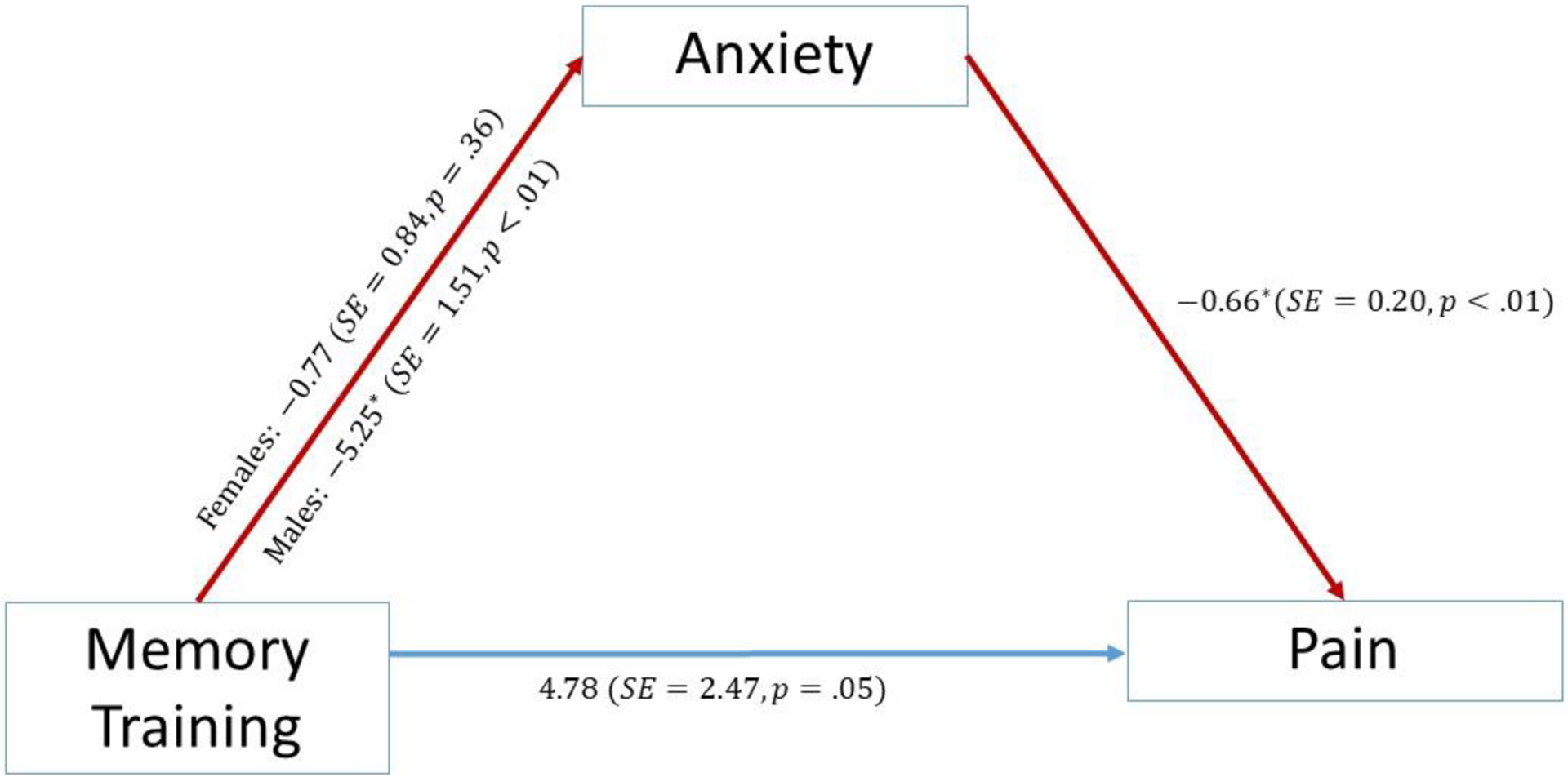

Given that no treatment group differences were present for pain at end-of-study, the mediation analysis focuses on the immediate post-treatment period. The process we studied was a moderated mediation, since a treatment-by-gender interaction was present for anxiety. Figure 4 shows the treatment had different effects on males and females for anxiety. The memory intervention significantly reduced post-treatment anxiety for males but not for females, and participants with reduced post-treatment anxiety reported significantly less pain at post-treatment.

Figure 4.

Moderated Mediation Path Model with Estimates.

Table 3 shows that the indirect effect of the memory intervention on pain was significant for males, but not females, with the indirect effect also being significantly greater for males than females. Specifically, the indirect effect for males indicates that the memory intervention reduced pain, in part, by reducing post-treatment anxiety which, in turn, diminished pain. For females, the indirect effect of the memory intervention was much smaller and not significant. Figure 4 also shows that for participants having the same post-treatment anxiety, those in the memory intervention reported less post-treatment pain than did participants in the HT group, with the significance level of this direct effect of the treatment of 4.78 points being just above the .05 level (p = .053).

Table 3.

Indirect Effects of the Memory Intervention on Pain Through Anxiety by Gender

| Post-Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | SE Bootstrap | Bootstrap 95% C.I. | |

| Male | 3.46 | 1.50 | (0.82, 6.68) |

| Female | 0.56 | 0.64 | (−0.57, 2.02) |

| Difference | 2.89 | 1.50 | (0.34, 6.16) |

N = 241.

Note: Number of bootstrap samples = 10,000.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine if a MT and/or HT intervention affected overall bodily pain and anxiety in cognitively intact older adults, whether such effects varied by gender, and whether intervention effects on pain were mediated by anxiety. We found that after the memory intervention, males in the MT group reported significantly less anxiety than males in the HT group, and this decrease was maintained over time. As a result, whereas males reported greater anxiety than females in the HT condition, males and females had similar anxiety in the MT group, suggesting beneficial equalizing effects of MT. In addition, we found that overall bodily pain was reduced for males and females generally, and this decrease in bodily pain was in response to the memory intervention. Further, the reduction in pain in males resulted indirectly via their decrease in anxiety. However, decreased bodily pain in females could not be attributed to a reduction in anxiety.

Although there is controversy around the impact of gender on central pain processing and pain sensitivity (Monroe et al., 2017; Monroe et al., 2015), these differences could influence mechanisms and efficacy of interventions. A study in the context of a rehabilitation program found that women have better activity level, pain acceptance and social support while men reported more fear of movement and mood disturbances (Rovner et al., 2017). Of interest, men reported altered mood states that were associated with increased pain unpleasantness but not pain intensity (Loggia, Mogil, & Bushnell, 2008). Our finding that males experienced decreased bodily pain indirectly via reduced anxiety resulting from the memory intervention is supported, in part, by previous work. In response to topical capsaicin, and despite females reporting greater pain intensity and unpleasantness, males demonstrated a positive correlation between anxiety and pain intensity and unpleasantness whereas women did not. Thus, even though females rated pain higher than men, yet despite expressing lower pain ratings, males have more anxiety related to pain (Frot, Feine, & Bushnell, 2004).

Regarding anxiety not being a mediator for women, even though there was a mindfulness component in the intervention, other psychosocial determinants such as acceptance may be operating as a mechanism. Women used a variety of pain coping strategies such as catastrophizing and self-efficacy (Bartley & Fillingim, 2013). Our study was based on memory self-efficacy, a domain specific component of the MT designed to increase enactive mastery through performance accomplishments. Specific mechanisms designed to influence pain-specific coping were not the emphasis of the training. According to Bandura (2012), efficacy differs across individuals and not only across different domains of functioning but also across various facets within an activity domain. This theoretical mechanism precludes a single all-purpose measure of self-efficacy. Although there is disagreement around the impact of gender on central pain processing and pain sensitivity, these differences could influence mechanisms and efficacy of interventions (Monroe et al., 2017; Monroe et al., 2015).

Another possibility is tailoring the intervention according to gender, anxiety level and pain levels. This type of matching may be accomplished by assessing the level before a session and matching the content according to the results. Content matching is the most important ingredient in tailored interventions and has been lacking in pain management interventions (Martorella, Boitoe, Berube et al., 2017). In addition, enhancing the effect on pain reduction and maintaining the latter over time is expanding the intervention based on the biopsychosocial model of pain might empower patients in their daily life and promote pain self-management. To our knowledge, interventions have not been tailored for gender differences. Understanding women’s as opposed to men’s pain experience and coping styles could inform the refinement/tailoring of interventions resulting in improved pain outcomes.

The potential for introducing error into the internal validity of all self-report measures was a concern. All self-report measures used were reliable and valid known measures of the constructs. To reduce fear among the minority participants we implemented strategies such as referring to the testing session as “interviews”, had multiple sessions to reduce fatigue, sat with the participants to reduce test anxiety and answered any questions (Austin, Gibson, Deary et al. 1998).

Another contribution of the study was to demonstrate significant differences in perception of bodily pain. After the intervention, females reported less pain (as higher scores indicated less pain), but this was significant only at first follow-up. So, other than this time point, there were no significant gender differences in pain perception. Health conditions was a significant predictor of pain at each time point, with higher numbers of health conditions predicting greater pain and as expected, baseline pain predicts subsequent pain.

Strengths and Limitations

This study had multiple strengths. First, the multi factorial psychosocial intervention included the components of both memory strategy and mindfulness training. Next, the volunteer triethnic sample was highly motivated and maintained their interest in this longitudinal study as evidenced by a 79% retention rate for the entire sample. Next, the range of outcomes was comprehensive, and the cognitive measures were administered at each measurement occasion. For a description of the overall study findings, the reader is referred to the main study findings (McDougall, Becker, Pituch, Vaughan, Acee, & Delville, 2010). Finally, by teasing apart gender differences, the study contributed new knowledge of differences between males and females in bodily pain, and trait anxiety that were affected by the memory intervention.

This study had limitations. First, from a measurement perspective, one question measured the effect of bodily pain over the past four weeks. Nevertheless, this item in the SF-36 is considered a domain of overall health. Next, medication intake was not documented however we addressed this limitation by counting chronic conditions and symptoms based on the individuals’ perception of their health. Next, in the biopsychosocial model of pain, social support plays an important role with older adults who are often more isolated. Third, no class was smaller than four individuals or larger than 15; however, we strove for an average class size of 12 individuals. Classes were purposely designed for multiple interactions, practice, and feedback but since randomization occurred at each site, we were limited by the number of participants who volunteered. We did not measure social support. However, we used financial status as a variable in our statistical model. Future studies should consider measuring functional and structural support and their impact on mental health.

Psychiatric Nursing Implications

CBT training that is tailored to gender and/or gender may increase the efficacy of the programs and “buy-in” from male participants, especially if the CBT intervention is tailored to anxiety and pain. The need for improved gender and gender based mental health care policies is also evidenced by beliefs about masculinity and ‘gender role conflict’ being associated with a decrease in males’ willingness to seek psychological counseling (Enns, 2000).

Day, Jensen, Ehde, Thorn (2014) provided specific recommendations for future inquiries that stylize a chronic pain model of mindfulness-based pain management. Their concerns emphasized theoretical and research considerations. The 45-minute dosage recommendation of the typical intervention requires support of effectiveness. The concept of reperceiving pain as a meta-mechanism has not been integrated into studies. The idea of motivation, either internal or external is considered a crucial element to the success of the intervention. Moderators of pain treatments are rarely included in studies, such as baseline characteristics. Finally, measures that operationalize the mindfulness construct are rare. Two examples of measures include the Pain Catastrophizing Scale and the Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire. Furthermore, previous research has demonstrated that current anxiety is a significant predictor of chronic pain discomfort (Feeney, 2004) and the current findings supported this work in that reducing anxiety in males leads to their improved pain perception. Ultimately, since pain is a multidimensional experience, using assessment tools to capture this holistic phenomenon will improve outcomes.

Acknowledgements:

National Institute on Aging R01 AG15384

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson AR, Deng J, Anthony RS, Atalla SA, & Monroe TB (2017). Using complementary and alternative medicine to treat pain and agitation in dementia: A review of randomized controlled trials from long-term care with potential use in critical care. Critical Care Nursing Clinics North America, 29(4), 519–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin EJ, Gibson GJ, Deary IJ, McGregor MJ, & Dent JB (1998). Individual response spread in self-report scales: personality correlations and consequences. Personality and Individual Differences, 24, 421–438. [Google Scholar]

- Austin-Wells V, Zimmerman T, & McDougall GJ (2003). An optimal delivery format for lectures targeting mature adults. Educational Gerontology, 29(6), 493–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB, & Danish SJ (1980). Intervention in life-span development and aging. In Turner RR, & Reese HW (Eds.), Life-span developmental psychology (pp. 49–78). New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (2012). On the functional properties of perceived self-efficacy revisited. Journal of Management, 38(1), 9–44. DOI: 10.1177/0149206311410606 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartley EJ, & Fillingim RB (2013). Gender differences in pain: a brief review of clinical and experimental findings. British Journal Anaesthesia, 111(1), 52–58. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellg AJ, Borrelli B, Resnick B, Hecht J, Minicucci DS, Ory M, et al. (2004). Treatment Fidelity Workgroup of the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: Best practices and recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Health Psychology, 23, 443–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevers K, Brecht D, Jones C & Gatchel RJ (2018). Pain Intervention Techniques for Older Adults: A Biopsychosocial Perspective.: EC Anesthesia, 4(3), 75–88 [Google Scholar]

- Bell-McGinty S, Podell K, Franzen M, Baird AD, & Williams MJ, (2002). Standard measures of executive function in predicting instrumental activities of daily living in older adults. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17, 828–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berryman C, Stanton TR, Jane Bowering K, Tabor A, McFarlane A, & Lorimer Moseley G (2013). Evidence for working memory deficits in chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain, 154(8), 1181–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckalew N, Haut MW, Morrow L, & Weiner D (2008). Chronic pain is associated with brain volume loss in older adults: preliminary evidence. Pain Medicine, 9(2), 240–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess DJ, Evans R, Allen KD, Bangerter A, Bronfort G, Cross LJ, Ferguson JE, Haley A, Hagel Campbell EM, Mahaffey MR, Matthias MS, Meis LA, Polusny MA, Serpa JG, Taylor SL, Taylor BC. Learning to Apply Mindfulness to Pain (LAMP): Design for a Pragmatic Clinical Trial of Two Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Chronic Pain. Pain Med. 2020. December 12;21(Suppl 2):S29–S36. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnaa337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cape J, Whittington C, Buszewicz M, Wallace P, Underwood L. Brief psychological therapies for anxiety and depression in primary care: meta-analysis and meta-regression. BMC Med. 2010;8(1):38. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Census Bureau’s Vintage Population Estimates (2019). 2020 Census Will Help Policymakers Prepare for the Incoming Wave of Aging Boomers. Retrieved from: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2019/12/by-2030-all-baby-boomers-will-be-age-65-or-older.html

- Cockburn J, & Smith PT (1989). The Rivermead Behavioural Memory Test. Supplement 3: Elderly People. Thames Valley Test Company: Bury St. Edmonds, Suffolk. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control (2018). Prevalence of Chronic Pain and High-Impact Chronic Pain Among Adults — United States, 2016. Retrieved 5/15/2020 https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/mm6736a2.htm [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya C, et al. (2018). Prevalence of Chronic Pain and High-Impact Chronic Pain Among Adults — United States, 2016. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Morbiidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67 (36), 1001–1006. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6736a2externalicon. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day MA, Jensen MP, Ehde DM, Thorn BE (2014). Toward a theoretical model for mindfulness-based pain management. Journal of Pain, 15(7), 691–703. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Heer EW, Gerrits MM, Beekman AT, Dekker J, van Marwijk HW, de Waal MW, Spinhoven P, Penninx BW, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM (2014). The association of depression and anxiety with pain: a study from NESDA. PLoS One, 15;9(10):e106907. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon RA, Hultsch DF, & Hertzog C (1988). The metamemory in adulthood (MIA) questionnaire. Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 24, 671–688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dux MC, Woodard JL, Calamari JE, Messina M, Arora S, Chik H, et al. (2008). The moderating role of negative affect on objective verbal memory performance and subjective memory complaints in healthy older adults. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 14(2), 327–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards RR, Dworkin RH, Sullivan MD, Turk D & Wasan AD (2016). The role of psychosocial processes in the development and maintenance of chronic pain disorders. Journal of Pain, 17 (9 Supplement 1), T70–T92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, & Bandalos DL (2001). The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling, 8, 430–457. 10.1207/S15328007SEM0803_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel GL (1977). The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science, 196(4286), 129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enns CZ (2000). Gender issues in counseling. Handbook of counseling psychology, 3, 601–638. [Google Scholar]

- Ezzati A, Wang C, Katz MJ, Derby CA, Zammit AR, Zimmerman ME, Pavlovic JM, Sliwinski MJ, Lipton RB (2019). The temporal relationship between pain intensity and pain interference and incident dementia. Current Alzheimer Research, 16(2):109–115. doi: 10.2174/1567205016666181212162424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzati A, Katz MJ, Derby CA, Zimmerman ME, & Lipton RB (2019). Depressive symptoms predict incident dementia in a community sample of older adults: results from the Einstein aging study. Journal Geriatric Psychiatry & Neurology, January 10:891988718824036. doi: 10.1177/0891988718824036. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney SL (2004). The relationship between pain and negative affect in older adults: anxiety as a predictor of pain. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 18(6), 733–744. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0887618504000398?via%3Dihub [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillingim RB, King CD, Ribeiro-Dasilva MC, Rahim-Williams B, & Riley JL 3rd. (2009). Gender, gender, and pain: a review of recent clinical and experimental findings. Journal of Pain 10(5), 447–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillingim RB (2017). Individual differences in pain: Understanding the mosaic that makes pain personal. Pain, 158(Suppl 1), S11–S18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiocco AJ, Wan N, Weekes N, Pim H, & Lupien SJ (2006). Diurnal cycle of salivary cortisol in older adult men and women with subjective complaints of memory deficits and/or depressive symptoms: Relation to cognitive functioning. Stress, 9(3), 143–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, & McHugh PR (1975) ‘Mini-Mental State’: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12, 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frot M, Feine JS, & Bushnell MC (2004). Gender differences in pain perception and anxiety. A psychophysical study with topical capsaicin. Pain, 108(3), 230–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2017). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis; A Regression-Based Approach (2nd ed.). New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hilton L, Hempel S, Ewing BA, Apaydin E, Xenakis L, Newberry S, Colaiaco B, Maher AR, Shanman RM, Sorbero ME, & Maglione MA (2017). Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals Behavioral Medicine, 51(2), 199–213. doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9844-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howarth A, Riaz M, Perkins-Porras L, Smith JG, Subramaniam J, Copland C, Hurley M, Beith I, & Ussher M (2019). Pilot randomised controlled trial of a brief mindfulness-based intervention for those with persistent pain. Journal Behavioral Medicine, 42(6), 999–1014. doi: 10.1007/s10865-019-00040-5. Epub 2019 Apr 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe FJ, Porter L, Somers T, Shelby R, & Wren AV (2013). Psychosocial interventions for managing pain in older adults: outcomes and clinical implications. British Journal Anaesthesia, 111(1), 89–94. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton L, Hempel S, Ewing BA, Apaydin E, Xenakis L, Newberry S, Colaiaco B, Maher AR, Shanman RM, Sorbero ME, & Maglione MA (2017). Mindfulness Meditation for Chronic Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Annals Behavioral Medicine, 51, 199–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Association for the Study of Pain. (2011). IASP Taxonomy. Retrieved from http://www.iasp-pain.org/Taxonomy.

- Juul L, Pallesen KJ, Bjerggaard M, Nielsen C, Fjorback LO (2020). A pilot randomised trial comparing a mindfulness-based stress reduction course, a locally developed stress reduction intervention and a waiting list control group in a real-life municipal health care setting. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 409. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08470-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Sun YY, & Zhong BL (2018). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for family carers of people with dementia. Cochrane Database Systematic Review, 8(8), CD012791. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012791.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein DA, Amigo E, Duara R, Guterman A, Hurwitz D, & Berkowitz N et al. , (1989). A new scale for the assessment of functional status in Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences 44(4), 114–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loggia ML, Mogil JS, & Bushnell MC (2008). Experimentally induced mood changes preferentially affect pain unpleasantness. The Journal of Pain, 9(9), 784–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP (2008). Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Martorella G, Boitor M, Berube M, Fredericks S, Le May S, Gélinas C (2017). Tailored Web-Based Interventions for Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal Medical Internet Research, 19(11):e385. Published 2017 Nov 10. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matallana D, Santacruz CD, Cano C, Reyes P, Samper-Ternent R, Markides K, Ottenbacher KJ, & Reyes-Ortiz CA (2011). The relationship between education level and Mini Mental State Examination domains among older Mexican Americans. International Journal Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 24(1), 9–18. doi: 10.1177/0891988710373597. Epub 2010 Jun 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken LM, & Vowles KE (2014). Acceptance and commitment therapy and mindfulness for chronic pain: Model, process, and progress. American Psychologist, 69, 178–187. doi: 10.1037/a0035623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougall GJ, Becker H, Pituch K, Vaughan P, Acee T, & Delville C (2010). The Senior WISE study: Improving everyday memory in older adults. Archives Psychiatric Nursing, 24(5), 291–306. PMC2946102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougall GJ, & Becker H (2010). Health-training intervention for community-dwelling elderly in the Senior WISE study. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 24(2), 125–136. PMC2844656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowd J, Hafia G, Han AR in collaboration with McDougall G (2010). Direct assessment of functional status – Extended Version: Protocol. Kansas City, KS. Landon Center on Aging, University of Kansas Medical Center. [Google Scholar]

- McHorney C (1996). Measuring and monitoring general health status in elderly persons: Practical and methodological issues in using the SF-36 health survey. The Gerontologist, 36(5), 571–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHorney CA, Ware JE, & Raczek AE (1993). The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Medical Care, 31, 247–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeish D & Stapleton LM (2016) Modeling clustered data with very few clusters. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 51, 495–518. DOI: 10.1080/00273171.2016.1167008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills SEE, Nicolson KP, Smith BH (2019). Chronic pain: a review of its epidemiology and associated factors in population-based studies. British Journal Anesthesia, 123(2), e273–e283. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.03.023. Epub 2019 May 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molton IR & Terrill AL (2014). Overview of persistent pain in older adults. American Psychologist, 69(2), 197–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe TB, Fillingim RB, Bruehl SP, Rogers BP, Dietrich MS, Gore JC, Cowan RL (2017). Gender differences in brain regions modulating pain among older adults: a cross-sectional resting state functional connectivity study. Pain Medicine, 10.1093/pm/pnx084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe TB, Gore JC, Bruehl SP, Benningfield MM, Dietrich MS, Chen LM, … Atalla S (2015). Gender differences in psychophysical and neurophysiological responses to pain in older adults: a cross-sectional study. Biology of Gender Differences, 6(25), 1–20. doi: 10.1186/s13293-015-0041-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriarty O, McGuire BE, Finn DP (2011). The effect of pain on cognitive function: a review of clinical and preclinical research. Progress in Neurobiology, 93(3), 385–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2017). Mplus User’s Guide (8th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Penney LS, Haro E. Qualitative evaluation of an interdisciplinary chronic pain intervention: outcomes and barriers and facilitators to ongoing pain management. J Pain Res. 2019. March 1;12:865–878. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S185652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS, & Teri L (1986). Use of the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale with older adults. Clinical Gerontologist, 5, 119–136. [Google Scholar]

- Raja Srinivasa N., Carr Daniel B., Cohen Milton, Finnerup Nanna B., Flor Herta, Gibson Stepheng; Keefe Francis J., Mogil Jeffrey S., Ringkamp Matthias, Sluka Kathleen A., Song Xue-Jun, Stevens Bonniem; Sullivan Mark D., Tutelman Perri R., Ushida Takahirop; Vader Kyle. The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain. Pain: May 23, 2020. - 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano RR, Anderson AR, Failla MD, Dietrich MS, Atalla S, Carter MA, & Monroe TB (2019). Gender Differences in Associations of Cognitive Function with Perceptions of Pain in Older Adults. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 70(3), 715–722. doi: 10.3233/JAD-190142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovner GS, Sunnerhagen KS, Bjorkdahl A, Gerdle B, Borsbo B, Johansson F, Gillanders D (2017). Chronic pain and gender-differences; women accept and move, while men feel blue. PLoS One,12:e0175737. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savalei V (2010). Expected versus observed information in SEM with incomplete normal and nonnormal data. Psychological Methods, 15, 352–367. DOI: 10.1037/a0020143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan FA, & Wang J (2005). Disparities among older adults in measures of cognitive function by race or ethnicity. Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60(5), P242–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, & Lushene RE (1970). Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Self-Evaluation Questionnaire). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Turner JA, Holtzman S, Mancl L (2007). Mediators, moderators, and predictors of therapeutic change in cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain. Pain, 127, 276–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Leeuw G, Ayers E, Leveille SG, Blankenstein AH, van der Horst HE, & Verghese J (2018). The effect of pain on major cognitive impairment in older adults. Journal of Pain, 19(12), 1435–1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veehof MM, Trompetter HR, Bohlmeijer ET, Schreurs KM (2016). Acceptance- and mindfulness-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: a meta-analytic review. Cognitive Behavior Therapy, 45(1):5–31. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2015.1098724. Epub 2016 Jan 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Dietrich MS, Simmons SF, Cowan RL, & Monroe TB (2018). Pain interference and depressive symptoms in communicative people with Alzheimer’s disease: a pilot study. Aging & Mental Health, 22(6), 808–812. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2017.1318258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, & Sherbourne CD (1992). The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). Medical Care, 30(6), 473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westoby CJ, Mallen CD, & Thomas E (2009). Cognitive complaints in a general population of older adults: prevalence, association with pain and the influence of concurrent affective disorders. European Journal Pain, 13(9), 970–976. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.11.011. Epub 2008 Dec 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AC, Eccleston C, & Morley S (2012). Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Systematic Review, 11(11), CD007407. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007407.pub3. Update in Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Aug 12;8:CD007407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson BA, Cockburn J, & Baddeley AD, (1991). The Rivermead Behavioral Memory Test. Suffolk, UK: Thames Valley Test Company. [Google Scholar]