Abstract

Although Epirubicin (EPI) is a commonly used anthracycline for the treatment of breast cancer in clinic, the serious side effects limit its long-term administration including myelosuppression and cardiomyopathy. Nanomedicines have been widely utilized as drug delivery vehicles to achieve precise targeting of breast cancer cells. Herein, we prepared a DSPE-PEG nanocarrier conjugated a peptide, which targeted the breast cancer overexpression protein Na+/K+ ATPase α1 (NKA-α1). The nanocarrier encapsulated the EPI and grafted with the NKA-α1 targeting peptide through the click reaction between maleimide and thiol groups. The EPI was slowly released from the nanocarrier after entering the breast cancer cells with the guidance of the targeting NKA-α1 peptide. The precise and controllable delivery and release of the EPI into the breast cancer cells dramatically inhibited the cells proliferation and migration in vitro and suppressed the tumor volume in vivo. These results demonstrate significant prospects for this nanocarrier as a promising platform for numerous chemotherapy drugs.

Keywords: breast cancer, NKA-α1, epirubicin, targeted therapy, peptide

Introduction

Breast cancer incidence is rapidly growing since the late 1970s and has become the most frequently occurring cancer among females by far. 1,2 Female mammary gland is composed of skin, fiber texture, mammary gland, and adipose tissue. Breast mass, nipple discharge, skin change, nipple and areola abnormal, and axillary lymph node mass are typical signs of breast cancer. 3 -5 Breast cancer is a kind of malignant tumor originating in the mammary epithelial tissue and affect the health of female and even male seriously. 6,7 In order to diagnose and treat breast cancer efficiently, various studies have been conducted. 8 -10 Until now, for the non-metastatic breast cancer, surgical resection, axillary lymph node resection, and postoperative radiation are the main treatments; while for the metastatic breast cancer, endocrine therapy, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy are widely used. 11 -14 Among these aforementioned therapies, chemotherapy is a vital treatment for breast cancer in clinical. 15 Moreover, the commonly used drugs for chemotherapy, such as epirubicin, doxorubicin, and taxol are always accompanied by underestimated side effects, including but not limited to anemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, fatigue, and nausea. 15,16

To enhance the therapeutic effect of breast cancer drugs and reduce the side effects simultaneously, researchers develops various kinds of nanocarriers-based drug delivery systems which can target breast cancer cells firstly and then slowly release drugs inside tumor cells to reach precision breast cancer therapy. 17 -23 The most common nanocarriers can broadly be divided into 2 categories: inorganic nanoparticles, such as metal nanoparticles and silicon dioxide (SiO2) nanoparticles, and organic nanoparticles, such as liposomes, micellar nanoparticles, and polymer vesicles. 24 -32 Among the above mentioned nanocarriers, liposome, which is able to encapsulate both hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs, occupy a key position due to the excellent biocompatibility and easy preparation. 33 However, the blood circulation time of liposome is unsatisfactory because of the elimination by reticuloendothelial system (RES). 34 Therefore, Poly (ethylene glycol) (PEG) modified liposomes (PEG-LP) are developed as long-circulating liposomes. This is because that the hydrophilic PEG in the surface of the modified liposomes can be highly hydrated in humoral environment to form a hydration layer to avoid the rapid recognition by the RES. 35,36

To guarantee the targeting efficiency of nanoparticles, various kinds of targeting ligands including targeting peptides are grafted on the surface of nanocarriers. 37 -40 A significantly upregulated expression of the sodium pump Na+/K+ ATPase α1 subunit (NKA α1) is observed on a large proportion of human malignancies. 37 -40 The sodium pump NKA α1 subunit is established with an attractive cancer-related biomarker and therapeutic target in numerous cancers including breast cancer. Also, it is closely related to the development and progression of several cancers. Therefore, NKA α1 is recognized as an effective target for cancer therapy including breast cancer. A facile small peptide named S3 peptide (CSISSLTHC) screened from the phage display shows a high binding affinity toward cancer cells with NKA α1 overexpression. 41 It makes S3 peptide a helpful targeting peptide candidate for NKA α1 based cancer therapy. Benefiting from the active chemical groups, such as amino group and carboxyl group in PEG, the PEG-Liposomes can be easily modified by targeting ligands to reach precise drug delivery in vivo.

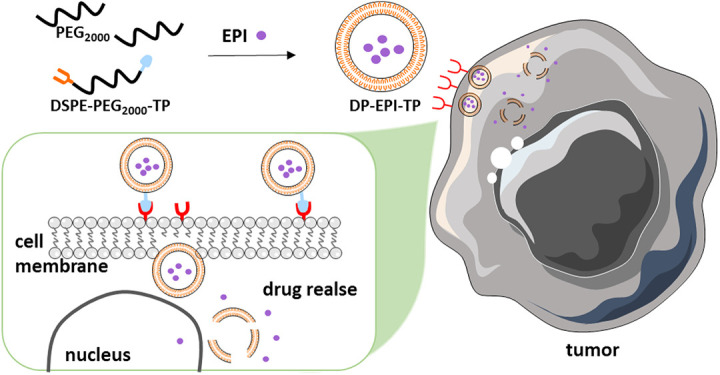

Herein, we choose 1,2-Distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-Poly (ethylene glycol)2000 (DSPE-PEG) as the main raw amphiphilic polymer for nanocarriers formation. 42 Moreover, NKA α1 targeting peptide grafted DSPE-PEG (DSPE-PEG-TP) is prepared based on the reaction between the carboxyl groups of PEG and the amino groups of NKA α1 peptide. Epirubicin (EPI) is used as the model drugs in this study. 4,43 The final EPI delivered and NKA α1 targeting small peptide grafted DSPE-PEG liposomes (DP-EPI-TP) are self-assembled by using the one-step lipid-based film method. Both the in vitro and in vivo results demonstrated that the well-designed DP-EPI-TP nanoparticle is a promising system for breast cancer treatment. In addition, this nanocarrier system can be further developed to a potential platform for other solid tumor therapy.

Materials and Methods

Materials

1,2-Dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane (chloride salt) (DOTAP), cholesterol (Chol), 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[maleimide(polyethylene glycol)-2000] (DSPE-PEG-Mal), 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy(polyethylene glycol)-2000] (DSPE-PEG) and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-carboxyfluorescein (CFPE) were purchased from Ruixibio (Xi’an, Shanxi, China). All organic reagents are of analytical grade and purchased from Aladdin (Shanghai, China). FAM-labeled NKA α1 peptide and FAM-labeled control peptide were synthesized by Gene-Pharma Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA). The NKA α1 primary antibody (Catalog number: ab7671, Abcam), GAPDH primary antibody (Catalog number: ab8245, Abcam), and the relative second HRP-antibody (Catalog number: ab6728, Abcam) were purchased from Abcam (Shanghai, China).

Cell Lines

The human normal breast epithelial cells MCF-10A and the human breast cancer cells MDA-MB-231 were purchased from ATCC (American Type Culture Collection, VA, USA). The cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 25 mM HEPES buffer, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Preparation of Targeted Nanoparticles

DP-EPI-TP nanoparticles were fabricated by the lipid-based film method. Briefly, EPI methanol solution with the concentration as 1 mg/mL were prepared firstly and then this solution were mixed with the lipid mixture containing DSPE-PEG2000-TP/DSPE-PEG2000 with mass ratio 1:4 in chloroform. After 4 hours stirring at 35°C, the solvent was stirring removed by vacuum rotary evaporation to obtain EPI-containing lipid film. The dried film was immersed in PBS for 40 min and then collected the final DP-EPI-TP nanoparticles by using the 200 nm polycarbonate membrane. The DP-EPI nanoparticles were obtained with the similar method.

Characterization of Targeted Liposomes

The size, size distribution (PDI), and zeta potential of liposomes were analyzed using a Zeta sizer (Nano-ZS, Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, UK) equipped with a He-Ne laser (633 nm) at a scattering angle 173. About 5 µL micellar solution with a concentration 1 mg/mL diluted from the stocked micelle solution by Milli-Q water was dropped on 100-mesh Formvar-free carbon-coated copper grids (Ted Pella Type-A; nominal carbon thickness 2e3 nm). After evaporating the water by exposing to air at room temperature, the sample was inversely covered on a small drop of an aqueous hydrodated phosphotungstate (PTA) solution with a mass fraction of 2%. The micelle morphology was analyzed using the transmission electron microscope assay TEM (Hitachi, H-7000 Electron Microscope). The conventional TEM images were obtained at 75 kV.

In Vitro Drug Release

The EPI release rate from the DP-EPI-TP was studied by a dialysis method. Briefly, the PEG-pp-PEI-PE/PTX/siRNA (0.5 mL) was dialyzed (MWCO 2000 Da) against 40 mL of water containing 1 M sodium salicylate to maintain the condition at 37°C. The EPI in the outside media was determined by RP-HPLC during the experiment.

In Vitro Cellular Uptake

For in vitro cellular uptake analysis, MDA-MB-231 and MCF-10A cells were seeded in confocal dish at a density of 3 × 105 cells per well overnight. Cells were treated with the FAM labeled nanoparticles at a concentration of 10 μm for 1 h. After washing with PBST (PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20), the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). The immunofluorescence of the cells was visualized with Leica TCS SP5 Confocal Microscope.

Cell Viability Assay

The cells MDA-MB-231 and MCF-10A were seeded into 96 wells (2 × 103 per well) and incubated overnight. Then the cells were incubated with PBS, free EPI, TP, DP-EPI, and DP-EPI-TP, respectively. 10 µL CCK-8 solution and 90 µL medium were added into each well after 24 or 72 h incubation. Then the cells were incubated for 2 h at 37°C. The absorbance was determined at 450 nm using Microplate reader (ELx808 Absorbance Reader, Biotek).

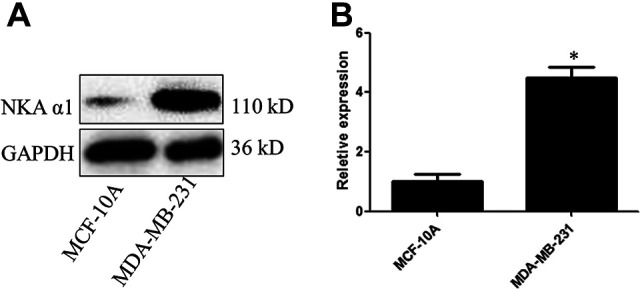

Western Blot

For the protein expression of NKA α1 in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-10A cells, 5 × 105 cells were seeded in 10 cm dish overnight. Cells were washed twice with PBS, and then the cells were treated as described in the cell viability assay. Cells were washed by PBS 3 times and lysed after 48 h incubation. Recombinant anti-NKA-α1 (1:2000 dilution) and GAPDH (1:10000 dilution) antibodies were used to detect the proteins expression.

Real-Time Quantitative PCR

The expression level of NKA-α1 in MDA-MB-231 cells or MCF-10A cells was detected by RT-PCR. Total RNA was extracted from the 2 cells with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and the first-strand cDNA was reversely transcribed from RNA using the Reverse Transcription System kit (Promega, USA). RT-PCR reactions were performed using an Applied Biosystems 7500 Sequence Detection system (Applied Biosystems, USA).

Transwell Migration Assay

MDA-MB-231 cells migration in response to DP-EPI-TP was measured using the Transwell system (polycarbonate, 8 µm pores, from Corning, USA). 600 μL 10% FBS medium were added into the low chambers. 5 × 104 cells in 200 µL of FBS free medium were placed in the top chambers and treated with the nanoparticles as the above description. Then the cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 18 h. The cells were fixed by methanol and stained with crystal violet. The stained cells were counted under a microscope with a 20× objective.

The Anti-Tumor Effectivity of DP-EPI-TP In Vivo

Female 4-6 weeks BALB/c nude mice were obtained from the laboratory animal center of Tongji University. All animal experiments were performed according to the protocols and guidelines approved by the Tongji University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Approval number: TJLAC-020-147). The mice were maintained on a standard laboratory under a 12 h/12 h light/dark schedule. Mice were randomly divided into 4 groups of 5 mice each. Each mouse was subcutaneously injected with 5 × 106 MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. When the tumor volume reached approximately 100 mm3, mice were injected intravenously via the tail vein with a single dose (0.8 mg per mouse) of the different formulations (1 injection every 2 days for 6 days). Tumor size and mouse body weight were monitored every 5 days with Vernier calipers. The volume (V) was calculated as: (V) = 1/2 × (width 2 × length).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by a Student’s t-test for direct comparisons and one-way analysis of variance for multiple groups. All the quantitative data are expressed using the mean ± SD (standard deviations). A P value less 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and Characterization of DSPE-PEG Based Nanocarriers

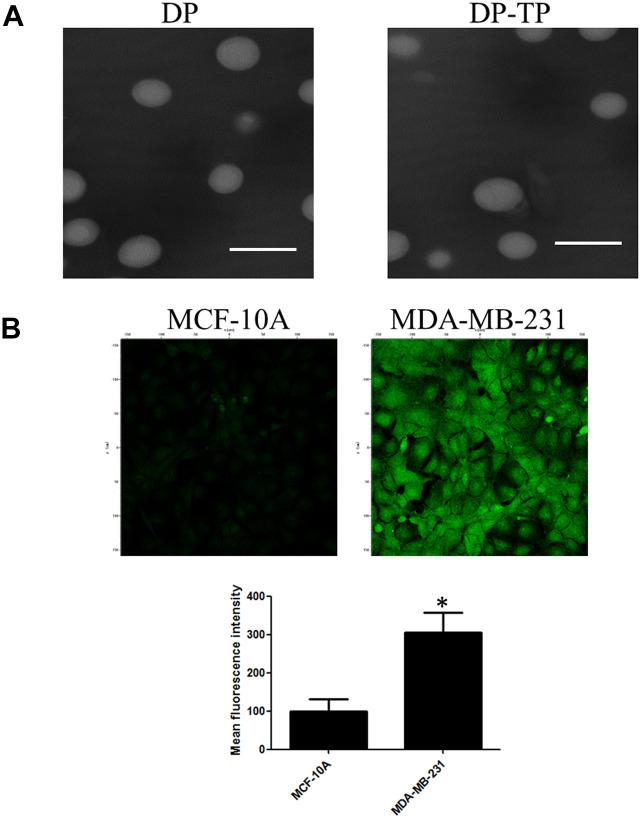

The DSPE-PEG based nanocarriers were fabricated by the lipid-based film method (Figure 1). As shown in the Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) (Figure 2A), both the pure DSPE-PEG liposomes (DP) and the NKA α1 targeting peptide (CSISSLTHC) conjugated and Epirubicin (EPI) encapsulated DSPE-PEG liposomes (DP-EPI-TP) are clearly uniform spherical structure diameter. Notably, the diameter of DP-EPI-TP is around 140 nm, which is similar to that of DP, demonstrating that the conjugation of NKA α1 targeting peptide and the encapsulation of EPI drug have no negative influence on the morphology of DSPE-PEG based liposome system. In addition, the zeta potential DP-EPI-TP (+24.9 ± 3.9) is significantly lower than that of DP (+32.7 ± 5.5) and DP-EPI (+26.4 ± 4.3) is due to the negative charge of the NKA α1 peptides, proving the successful targeting peptide grafting on the surface on the DP-EPI-TP nanocarrier (Table 1 and Figure S1).

Figure 1.

Preparation of EPI-loaded DSPE-PEG2000-TP nanomicelles and the mechanism of action of DP-EPI-TP in breast cancer cells.

Figure 2.

The characterization of DP-TP nanomicelles and the correlation between the targeting nanomicelles and the NKA α1 expression levels. A, Transmission electron microscope image of DP and DP-TP. The scale bar is 200 nm. B, Confocal fluorescent images of cellular uptake of FAM-DP and FAM-DP-TP. Nanoparticles at 10 μM were incubated with MDA-MB-231 or MCF-10A cells for 1 h at 37°C and extra nanoparticles in the medium was washed away before the cells were imaged. The lower panel shows the mean fluorescent intensity of different cells (*P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Characterization of Liposomes. Size, Polydispersity Indices (PDI), and Zeta Potential.a

| Liposomes | Size (nm) | PDI | Zeta potential (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DP | 138.4 ± 6.6 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | +32.7 ± 5.5 |

| DP-EPI | 140.1 ± 5.7 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | +26.4 ± 4.3 |

| DP-EPI-TP | 143.3 ± 6.9 | 0.18 ± 0.04 | +24.9 ± 3.9 |

a Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3).

Cellular Targeting Efficiency of DP-EPI-TP In Vitro

Only about 20% of the loaded EPI was released from DP-EPI-TP complexes after 4 h incubation, while more than 80% drug was released after 20 h incubation (Figure S2). This appropriate drug release profile ensured the efficient cell internalization of the loaded EPI as well as the sufficient dose of the released EPI for effective anticancer activity after endocytosis.

To determine the cellular targeting efficiency of DP-TP in the breast cancer cells, FAM-DP and FAM-DP-TP were incubated in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-10A cells for 1 h and any free nanomicells in the buffer was removed by washing with PBS. FAM-DP-TP efficiently targeted and entered the MDA-MB-231 cells with high florescence, while the non-targeting FAM-DP group shows low florescence (Figure 2B). We detected the relative NKA α1 expression of protein and mRNA in human breast cancer cell MDA-MB-231 and a normal human breast epithelial cell MCF-10A. The NKA α1 protein expression in MDA-MB-231 was significantly higher than that in normal human breast epithelial cell MCF-10A (Figure 3A). Meanwhile, the NKA α1 mRNA showed the similar expression with the protein expression in the 2 types of cells (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

NKA α1 protein (A) and mRNA (B) expression in human breast normal epithelial cells MCF-10A and human breast cancer cells MDA-MB-231 (*P < 0.05).

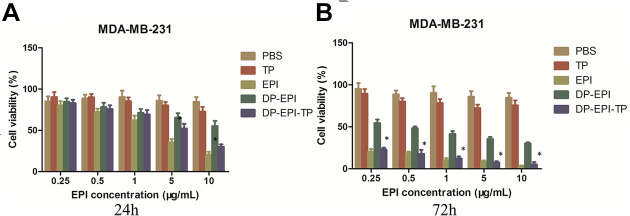

In Vitro Cytotoxicity of DSPE-PEG Based Nanocarriers

To evaluate the therapeutic effect of DP-EPI-TP nanocarriers, the human breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells and the human normal breast MCF-10A cells were treated with pure NKA α1 targeting peptide (TP), pure drug EPI, DP-EPI, DP-EPI-TP, and negative control PBS, respectively. As presented in Figure 4, both TP and PBS groups show around 100% cell viability after 24 h or 72 h in vitro culture, demonstrating the non-toxicity of NKA α1 targeting peptide. EPI and DP-EPI-TP groups show obviously lower cell viability than TP and PBS groups, and the cell viability of EPI and DP-EPI-TP groups decrease with the increasing of EPI concentration and the prolonging of cell culture time. Moreover, compared to DP-EPI groups which is without NKA α1 targeting peptide, DP-EPI-TP still show significantly lower cell viability in human normal breast cells MCF-10A (Figure S3). These results strongly certify that the conjugation of NKA α1 targeting peptide on the DSPE-PEG based liposomes can efficiently help the precise drug delivery and releasing for breast cancer cells.

Figure 4.

Viability of MDA-MB-231 cells in response to the different treatments. Cells were treated with the different groups incubated for 24 (A) and 72 h (B) before counting by CCK-8 assay (DP-EPI-TP vs the other groups, *P < 0.05).

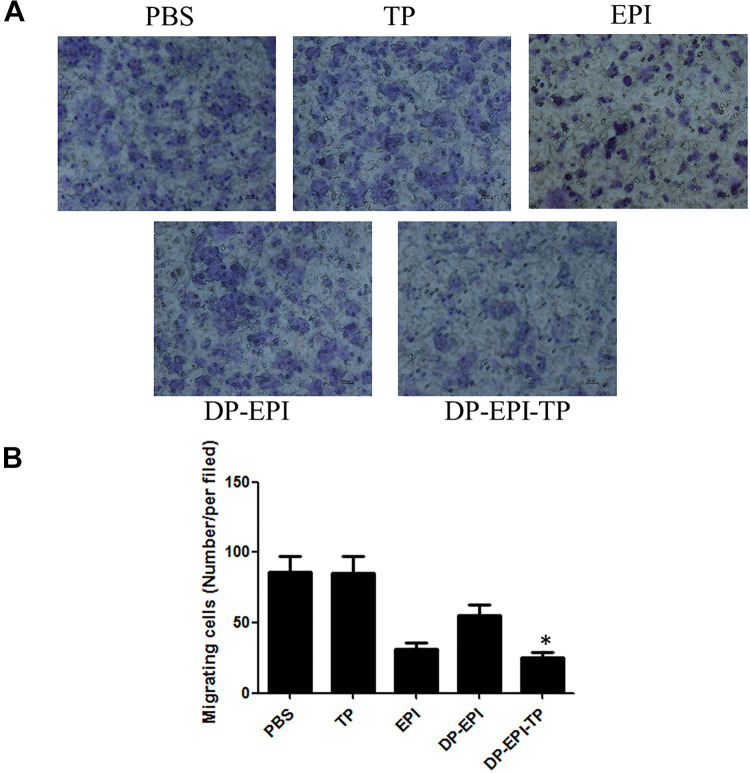

NKA α1 Targeted Nanoparticles Inhibits the Migration of Breast Cancer Cells

Cell migration was closely related to numerous tumor biological phenomena including progression and morphogenesis. We next measured whether targeting group DP-EPI-TP would lead to the inhibition of breast cancer cells migration in vitro. The ability of breast cancer cells migration was determined by the quantification of the staining of cells number using of the Transwell system. The results showed that free EPI, DP-EPI, and DP-EPI-TP inhibited cellular migration compared with the PBS or TP groups after 16 h incubation (Figure 5A and B). Moreover, DP-EPI-TP group demonstrated significant inhibition of cell migration compared with the DP-EPI group. This suggests that DP-EPI-TP can specifically inhibit cell migration in NKA α1-overexpressing breast cancer cells.

Figure 5.

Effect of DP-EPI-TP on breast cancer cells migration. A, The representative images of staining of cells that have migrated under a microscope. B, Quantification of the migrating cancer cells with different groups. The migrating cells markedly decreased with treatment of DP-EPI-TP and EPI in MDA-MB-231 cancer cells (DP-EPI-TP vs the other groups, *P < 0.05).

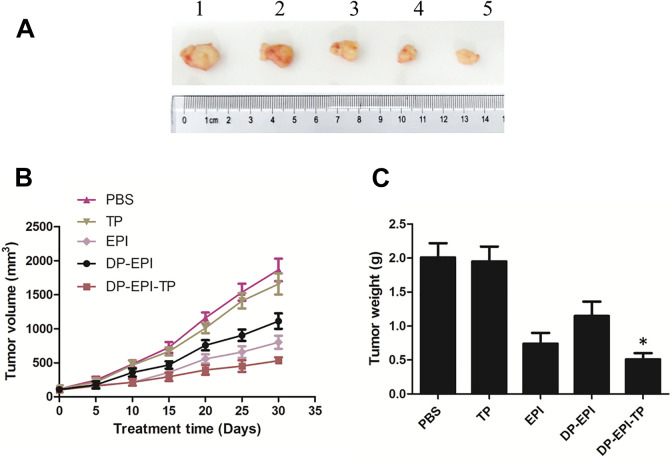

In Vivo Therapeutic Efficacy of DP-EPI-TP Nanomicelles

We further measure the therapeutic effect of DSPE-PEG nanocarriers system in vivo. The breast cancer xenograft model was established through subcutaneous injection of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells into BALB/c nude mice. When the tumor volume reached to around 100 mm3, mice were treated with PBS, TP, EPI, DP-EPI, and DP-EPI-TP via tail vein injection randomly. By testing the tumor volume and weight (Figure 6A and B), we can observe without the conjugation of NKA α1 targeting peptide, DP-EPI show unsatisfactory inhibition effect of tumor growth. However, DP-EPI-TP groups show the same level of tumor inhibition effect as EPI groups, which is much lower than the PBS negative control groups and DP-EPI groups. It demonstrates that the grafted NKA α1 targeting peptide greatly improve the efficiency of drug delivery. While the DP-EPI-TP groups play a most significantly role in inhibiting the volume and weight of tumor than other groups, indicating the DP-EPI-TP nanomicelles have the effectively active in anti-breast cancer treatment. These results were consistent with the cytotoxicity test. Furthermore, the advantages of the DP-EPI-TP nanomicelles include accurately peptide targeting and effectively delivery of drugs.

Figure 6.

In vivo antitumoral effect of DP-EPI-TP nanomicelles in tumor-bearing mice. (A) A representative picture of the excised tumors of each group (1: PBS; 2: TP; 3: DP-EPI; 4: EPI; 5: DP-EPI-TP). Tumor volume (B) and tumor weight (C) measurement throughout the treatments (DP-EPI-TP vs the other groups, *P < 0.05).

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-tct-10.1177_15330338211027898 for Controllable Drug Delivery by Na+/K+ ATPase α1 Targeting Peptide Conjugated DSPE-PEG Nanocarriers for Breast Cancer by Yayan Yang, Qian Feng, Chuanfeng Ding, Wei Kang, Xiufeng Xiao, Yongsheng Yu and Qian Zhou in Technology in Cancer Research & Treatment

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: All animal experiments were performed according to the protocols and guidelines approved by the Tongji University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Approval number: TJLAC-020-147).

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Financial support for this work was provided via the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81902622, 81771659, 31900963, and 21807043), the Shanghai “Science and Technology Innovation Action Plan” Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan Science and Technology Cooperation Project (20430760100), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (DUT20RC(3)069).

ORCID iDs: Wei Kang, PhD  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2288-3540

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2288-3540

Yongsheng Yu, PhD  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5139-3439

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5139-3439

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Anastasiadi Z, Lianos GD, Ignatiadou E, Harissis HV, Mitsis M. Breast cancer in young women: an overview. Updates Surg. 2017;69(3):313–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Desantis C, Howlader N, Cronin KA, Jemal A. Breast cancer. Soins. 1977;22(19):25–31. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schmidt T, Mackelenbergh MV, Wesch D, Mundhenke C. Physical activity influences the immune system of breast cancer patients. J Cancer Res Ther. 2017;13(3):392–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vulsteke C, Pfeil AM, Maggen C, et al. Clinical and genetic risk factors for epirubicin-induced cardiac toxicity in early breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;152(1):67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. American Association for Cancer Research. Asparagine bioavailability drives breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Discov. 2018;8(4):381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tray N, Taff J, Adams S. Therapeutic landscape of metaplastic breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2019;79:101888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Bellon JR, et al. Concurrent veliparib with chest wall and nodal radiotherapy in patients with inflammatory or locoregionally recurrent breast cancer: the TBCRC 024 phase I multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(13):JCO2017772665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yaraki MT, Tan YN. Recent advances in metallic nanobiosensors development: colorimetric, dynamic light scattering and fluorescence detection. Sensors Int. 2020;1:100049. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yaraki MT, Tan YN. Metal nanoparticles-enhanced biosensors: synthesis, design and applications in fluorescence enhancement and surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Chem Asian J. 2020;15(20):3180–3208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rabiee N, Yaraki MT, Garakani SM, et al. Recent advances in porphyrin-based nanocomposites for effective targeted imaging and therapy. Biomaterials. 2020;232:119707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maughan KL, Lutterbie MA, Ham PS. Treatment of breast cancer. New England J Med. 2010;81(11):1339–1346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sun WT, Yan K, Han J, et al. Bone-targeted nanoplatform combining zoledronate and photothermal therapy to treat breast cancer bone metastasis. ACS Nano. 2019;13(7):7556–7567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang Y, Lin YX, Qiao ZY, et al. Self-assembled autophagy-inducing polymeric nanoparticles for breast cancer interference in-vivo. Adv Mater. 2015;27(16):2627–2634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Plassat V, Wilhelm C, Marsaud V, et al. Anti-estrogen-loaded superparamagnetic liposomes for intracellular magnetic targeting and treatment of breast cancer tumors. Adv Funct Mater. 2011;21(1):83–92. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Veronesi U, Boyle P, Goldhirsch A, Orecchia R, Viale G. Breast cancer. Lancet. 2005;365(9472):1727–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee H, Park S, Kim JB, Kim J, Kim H. Entrapped doxorubicin nanoparticles for the treatment of metastatic anoikis-resistant cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2013;332(1):110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Herrera Estrada L, Padmore TJ, Champion JA. Bacterial effector nanoparticles as breast cancer therapeutics. Mol Pharm. 2016;13(3):710–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liu Y, Qiao L, Zhang S, et al. Dual pH-responsive multifunctional nanoparticles for targeted treatment of breast cancer by combining immunotherapy and chemotherapy. Acta Biomater. 2017;66(15):310–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Akbarzadeh I, Yaraki MT, Ahmadi S, Chiani M, Nourouzian D. Folic acid-functionalized niosomal nanoparticles for selective dual-drug delivery into breast cancer cells: an in-vitro investigation. Adv Powder Technol. 2020;31(9):4064–4071. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ghafelebashi R, Yaraki MT, Saremi LH, et al. A pH-responsive citric-acid/α-cyclodextrin-functionalized Fe3O4 nanoparticles as a nanocarrier for quercetin: an experimental and DFT study. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2020;109:110597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Akbarzadeh I, Yaraki MT, Bourhour M, et al. Optimized doxycycline-loaded niosomal formulation for treatment of infection-associated prostate cancer: an in-vitro investigation. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2020;57:101715. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Haggag Y, Elshikh M, Tanani ME, Bannat IM, McCarron P, Tambuwala MM. Nanoencapsulation of sophorolipids in PEGylated poly(lactide-co-glycolide) as a novel approach to target colon carcinoma in the murine model. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2020;10(5):1353–1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Haggag YA, Ibrahim RR, Hafiz AA. Design, formulation and in vivo evaluation of novel honokiol-loaded PEGylated PLGA nanocapsules for treatment of breast cancer. Int J Nanomedicine. 2020;15:1625–1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Heleg Shabtai V, Aizen R, Sharon E, et al. Gossypol-capped mitoxantrone-loaded mesoporous SiO2 NPs for the cooperative controlled release of two anti-cancer drugs. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8(23):14414–14422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Goodman AM, Neumann ON, Rregaard K, et al. Near-infrared remotely triggered drug-release strategies for cancer treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(47):12419–124242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ali W, Ilyas A, Bui L, et al. Differentiating metastatic and non-metastatic tumor cells from their translocation profile through solid-state micropores. Langmuir. 2016;32(19):4924–4934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cao H, Dan Z, He X, et al. Liposomes coated with isolated macrophage membrane can target lung metastasis of breast cancer. ACS Nano. 2016;10(8):7738–7748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu JQ, Liu XS, Liao YP, et al. Breast cancer chemo-immunotherapy through liposomal delivery of an immunogenic cell death stimulus plus interference in the IDO-1 pathway. ACS Nano. 2018;12(11):11041–11061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 29. Boweman CJ, Byrne JD, Chu KS, et al. Docetaxel-loaded PLGA nanoparticles improve efficacy in taxane-resistant triple-negative breast cancer. Nano Lett. 2017;17(1):242–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ghafelehbashi R, Akbarzadeh I, Yaraki MT, Lajevardi A, Fatemizadeh M, Heidarpoor Saremi L. Preparation, physicochemical properties, in vitro evaluation and release behavior of cephalexin-loaded niosomes. Int J Pharm. 2019;569:118580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yaraki MT, Pan Y, Hu F, Yu Y, Liu B, Tan YN. Nanosilver-enhanced AIE photosensitizer for simultaneous bioimaging and photodynamic therapy. Mater Chem Front. 2020;4(10):3074–3095. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yaraki MT, Wu M, Middha E, et al. Gold nanostars-AIE theranostic nanodots with enhanced fluorescence and photosnesitization towards effective image-guided photodynamic therapy. Nano-Micro Lett. 2021;13(1):1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Haggag Y, Ras BA, Tanani YE, et al. Co-delivery of a RanGTP inhibitory peptide and doxorubicin using dual-loaded liposomal carriers to combat chemotherapeutic resistance in breast cancer cells. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2020;17(11):1655–1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lane RS, Michael HF, Chavaroche AAE, Andrew A, Deangelis PL. Heparosan-coated liposomes for drug delivery. Glycobiology. 2017;27(11):1062–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hu J, Youssefian S, Obayemi J, Malatesta K, Rahbar N, Soboyejo W. Investigation of adhesive interactions in the specific targeting of triptorelin-conjugated PEG-coated magnetite nanoparticles to breast cancer cells. Acta Biomater. 2018;71(15):363–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Peng J, Chen J, Xie F, et al. Herceptin-conjugated paclitaxel loaded PCL-PEG worm-like nanocrystal micelles for the combinatorial treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer. Biomaterials. 2019;222:119420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Brinkman AM, Chen G, Wang Y, et al. Aminoflavone-loaded EGFR-targeted unimolecular micelle nanoparticles exhibit anti-cancer effects in triple negative breast cancer. Biomaterials. 2016;101:20–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Garcia DG, de Castro-Faria-Neto HC, da Silva CI, et al. Na/K-ATPase as a target for anticancer drugs: studies with perillyl alcohol. Mol Cancer. 2015;14:105–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Winnicka K, Bielawski K, Bielawska A, Surayński A. Antiproliferative activity of derivatives of ouabain, digoxin and proscillaridin A in human MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2008;31(6):1131–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Xiao Y, Meng C, Lin J, et al. Ouabain targets the Na+/K+ATPase α3 isoform to inhibit cancer cell proliferation and induce apoptosis. Oncol Lett. 2017;14(6):6678–6684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wang Q, Li SB, Zhao YY, et al. Identification of a sodium pump Na+/K+ ATPase α1-targeted peptide for PET imaging of breast cancer. J Control Release. 2018;281(10):178–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hye D, Kim NB, Sook H, Hwang HS, Na K. Gemcitabine-loaded DSPE-PEG-PheoA liposome as a photomediated immune modulator for cholangiocarcinoma treatment. Biomaterials. 2018;183:139–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhang J, Kinoh H, Hespel L, et al. Effective treatment of drug resistant recurrent breast tumors harboring cancer stem-like cells by staurosporine/epirubicin co-loaded polymeric micelles. J Control Release. 2017;264(28):127–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-tct-10.1177_15330338211027898 for Controllable Drug Delivery by Na+/K+ ATPase α1 Targeting Peptide Conjugated DSPE-PEG Nanocarriers for Breast Cancer by Yayan Yang, Qian Feng, Chuanfeng Ding, Wei Kang, Xiufeng Xiao, Yongsheng Yu and Qian Zhou in Technology in Cancer Research & Treatment