Abstract

Background

Sudden death accounts for up to 15% of all deaths among working age adults. A better understanding of victims’ medical care and symptoms reported at their last medical encounter may identify opportunities for interventions to prevent sudden deaths.

Methods

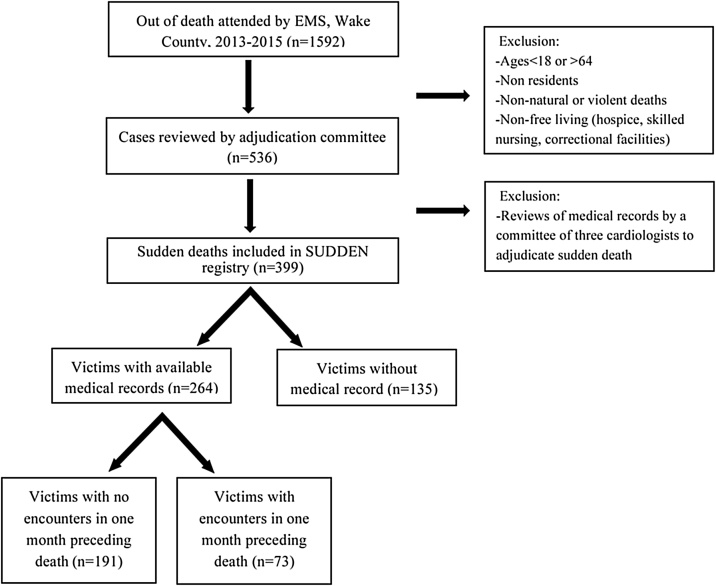

From 2013−15, all out-of-hospital deaths, ages 18–64 reported by Emergency Medical Services (EMS) in Wake County, North Carolina were screened and adjudicated to identify 399 victims of sudden death, 264 of whom had available medical records. Demographic and clinical characteristics and prescribed medications were compared between victims with versus without a medical encounter within one month preceding death with chi-square tests and t-tests, as appropriate. Symptoms reported in medical encounters within one month preceding death were analyzed.

Results

Among the 264 victims with available medical records, 73 (27.7%) had at least one encounter within a month preceding death. These victims were older and more likely to have multiple chronic illnesses, yet most were not prescribed evidence-based medicines. Of these 73 victims, 30 (41.1%) reported cardiac symptoms including dyspnea, edema, and chest pain.

Conclusions

Many victims seek medical care and report cardiac symptoms in the month prior to sudden death. However, medications that might prevent sudden death are under prescribed. These findings suggest that there are opportunities for intervention to prevent sudden death.

Keywords: Sudden death, Symptoms, Access to care, Medical care, Paramedicine

Introduction

Sudden death is a major public health concern in the US. The annual incidence in working age adults in the United States is estimated to be 35 per 100,000, or 15% of all deaths in individuals aged 18–64.1, 2, 3 Despite improvements in medical care and cardiopulmonary resuscitation, the incidence of sudden death has not decreased in proportion to the observed decline in cardiovascular mortality.4 Resuscitation outcomes for out-of-hospital sudden death are poor, but identifying precipitating factors and intervening may lower the incidence of sudden death.5

Previous studies demonstrated that sudden death may be preceded by premonitory symptoms in the days, weeks, or months before the event.6, 7, 8 Less is known about the frequency of medical encounters and symptoms at last medical visits prior to sudden death. Such information may identify high-risk individuals and guide intervention programs to prevent sudden death. Due to increasing health care demand and healthcare service gaps, home-based care teams such as community paramedicine have been utilized to address urgent but low acuity illnesses and injuries and provide chronic care and preventive services. The current COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated challenges in accessing medical care, prompting healthcare systems to turn to novel health care delivery systems. Provision of care through home-based care teams is a nascent model of care that may address gaps in access to care and ameliorate the increased burden on Emergency Medical Services (EMS) during the current pandemic. For these reasons, we assessed the symptoms in last medical encounters, chronic illnesses, and evidence-based medicine prescriptions in victims of sudden death.

Methods

All out-of-hospital deaths aged 18–64 in Wake County, North Carolina attended by EMS from 2013 to 2015 were screened. Detailed screening and adjudication methods have been previously described.9 Sudden death in our study included all types of sudden death not attributed to trauma, suicide, or natural expected death. Accordingly, person with terminal disease, evidence of overdose or other obvious non-natural cause (e.g., trauma, violent death, drowning) were excluded. Additionally, persons not community-dwelling (e.g., primary residence was in a skilled nursing facility or correctional facility) were excluded. Records from EMS reports, outpatient and inpatient medical records, death certificates, and medical examiner and toxicology reports were collected. Adjudication identified cases as sudden death if the circumstances surrounding the event suggested an abrupt pulseless condition in the absence of terminal disease such as cancers, or non-natural death (overdose, suicide, trauma). Demographic and clinical characteristics were abstracted from medical records. Medication prescriptions were assessed from the most current medication list in the medical record. All symptoms from the “chief complaint” and “history of present illness” sections of medical visits in the month prior to sudden death were abstracted. “Chest pain”, “dyspnea”, “dizziness”, “palpitation”, “syncope” and “pre-syncope” and “edema” and their synonyms were considered cardiac symptoms.

After continuous data was assessed for normality, demographic and clinical characteristics were compared between victims with versus without medical encounters in one month prior to death using chi-square tests and t-tests, as appropriate. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Results

Of 399 adjudicated cases of sudden death, medical records were available for 264 subjects (Fig. 1). Of the 135 subjects without medical records, mean age was 51.7 years, 103 (76.3%) were male, and 46 (33.3%) were African American. Among the 264 subjects with medical records, mean age was 53.3 years, 171 (64.8%) were male, and 92 (34.8%) were African American. Of these 264 subjects, 73 (27.7%) had at least one medical encounter and 26 (35.6%) of those 73 had more than one encounter in the month before death. Most encounters (79%) were outpatient visits. Chronic medical conditions were commonly present. Victims with recent encounters were older, more often prescribed evidence-based cardiovascular medications, and more likely to have many comorbidities including tobacco use disorder, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, chronic respiratory disease, chronic kidney disease, and heart failure (Table 1). Of the 73 victims, 30 (41.1%) reported cardiac symptoms, accounting for 59% of all reported symptoms with dyspnea (17.8 %), edema (17.8 %), and chest pain (13.7%) predominating (Table 2). Less commonly reported were syncope or presyncope (5.5%), dizziness (2.7%), or palpitations (1.4%). More than one cardiac symptom was reported in 9 (12%) victims. Demographic characteristics and comorbidities did not differ between victims with and without cardiac symptoms (Table 3). Despite a high prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and coronary disease, only 25 victims (34.2%) were on aspirin, 36 (49.3%) on beta blockers, 29 (39.7%) on statins, and 26 (35.6%) on an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE-I) or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of case ascertainment of sudden death and identification of victims with and without medical encounters preceding death.

Abbreviation: EMS, Emergency Medical Services.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of sudden death victims by recent health care encounter.

| Victims with medical visits within one month prior to death, N = 73 n (%) |

Victims without visits within one month prior to death, N = 191 n (%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average number of visits per person in 2 years | 14.0 | 4.6 | < 0.01 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 55.5 (8.6) | 52.5 (9.4) | <0.01 |

| Male | 45 (61.6%) | 126 (66.0%) | 0.46 |

| African-American | 31 (42.5%) | 61 (31.9%) | 0.09 |

| Medical comorbidities | |||

| Tobacco use disorder | 49 (67.1%) | 103 (53.9%) | <0.01 |

| Mental illnessa | 47 (64.4%) | 95 (49.7%) | <0.01 |

| Hypertension | 62 (84.9%) | 125 (65.4%) | <0.01 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 53 (72.6%) | 83 (43.5%) | <0.01 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 36 (49.3%) | 57 (29.8%) | <0.01 |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 37 (50.7%) | 71 (37.2%) | <0.01 |

| Coronary artery disease | 24 (32.9%) | 51 (26.7%) | 0.64 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 22 (30.1%) | 20 (10.5%) | <0.01 |

| Heart failure | 19 (26.0%) | 25 (13.1%) | <0.01 |

| Medications | |||

| Aspirin | 25 (34.2%) | 41 (21.5%) | 0.03 |

| Beta blocker | 36 (49.3%) | 55 (28.8%) | <0.01 |

| ACE-I/ARBb | 26 (35.6%) | 52 (27.2%) | 0.18 |

| Statin | 29 (39.7%) | 46 (24.1%) | 0.01 |

Mental illness includes depression, bipolar disease, anxiety, schizophrenia, substance abuse, and alcohol abuse.

ACE-I/ARB: Angiotensin Converting Enzyme/ Angiotensin II Receptor Blocker.

Table 2.

Symptoms reported by sudden death victims in recent health care encounters.

| Symptoms | Prevalence, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Noncardiac symptom | 43 (58.9) |

| Cardiac symptom | 30 (41.1) |

| Dyspnea | 13 (17.8) |

| Edema | 13 (17.8) |

| Chest pain | 10 (13.7) |

| Presyncope or syncope | 4 (5.5) |

| Dizziness | 2 (2.7) |

| Palpitations | 1 (1.4) |

| More than one cardiac symptom | 9 |

Table 3.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of sudden death victims with medical visits within one month prior to death by report of cardiac versus noncardiac symptoms.

| Cardiac symptoms, N = 30 n (%) |

Noncardiac symptoms, N = 43 n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 56.6 (7.1) | 55.5 (9.5) |

| Male | 18 (60.0) | 27 (62.8) |

| Medical comorbidities | ||

| Tobacco use disorder | 21 (70.0) | 28 (65.1) |

| Mental illnessa | 21 (70.0) | 23 (53.5) |

| Hypertension | 24 (80.0) | 38 (88.4) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 22 (73.3) | 31 (72.1) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 15 (50.0) | 21 (48.8) |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 19 (63.3) | 18 (41.7) |

| Coronary artery disease | 11 (36.7) | 13 (30.2) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 10 (33.3) | 12 (27.9) |

| Heart failure | 11 (36.7) | 8 (18.6) |

Mental illness includes depression, bipolar disease, anxiety, schizophrenia, substance abuse, and alcohol abuse.

Discussion

Approximately one third of sudden death victims had a medical encounter in the month preceding death. These victims were older and more likely to have comorbidities compared to victims without an encounter in the month preceding death. About half of these victims, representing 11.4% of all sudden death victims with medical records, reported probable cardiac symptoms such as dyspnea, edema, and chest pain. Our results are consistent with previous studies that showed that many victims see a physician in the month before their death and many cardiac arrests are preceded by warning symptoms.5, 6, 7, 8 An important limitation of our study is that 135 (33.8%) of the victims lacked medical records, precluding them from analysis, which may have introduced bias. Victims without medical records may be systematically different to victims with medical records. For example, compared to victims with medical records, victims with medical records were more likely to be male (76.3% versus 64.8%). Even among victims with medical records, those with a medical encounter in the month prior to death were more likely to be African-American (42.5% versus 31.9%). These sociodemographic differences may reflect unmeasured differences in comorbid conditions, access to medical care, or other social determinants. Furthermore, among patients with medical records, we are unable to ascertain whether evidence-based preventive medications were appropriately prescribed or to assess for patient adherence to evidence-based medications.

Our findings of prevalent medical comorbidities, frequent recent medical encounters, and antecedent cardiac symptoms suggest an opportunity for intervention to prevent sudden death. Possible interventions include modifying primary care provider practices or use of home-based interventions such as telehealth or mobile integrated healthcare to improve the prescription of and compliance with evidence-based medications and recommendations that may prevent sudden death. Further studies are needed to identify specific barriers to addressing cardiac symptoms presented during medical encounters in order to better target intervention strategies.

Conclusion

Some victims of sudden death present for medical care in the month preceding death, often with cardiac symptoms and without receipt of evidence-based medications. Intervention strategies targeting patients with prodromal symptoms may prevent sudden death.

Credit author statement

We verify that all authors have made substantial contributions to the draft. The specific authors contributions are as follows: EAM, MM, and RJS conceived and designed the analysis. FCL completed the statistical analyses. SKK, EAM, JGW, and STK wrote and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the revised manuscript for accuracy. The authors did not have any writing assistance.

Funding

The SUDDEN project is funded by individual, private donations, The Heart and Vascular Division of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and the McAllister Heart Institute. The project described was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health, through Grant Award Number UL1TR002489.

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ross J. Simpson, Jr. has served as consultant for Amgen, Merck, Pfizer, CEROBS, and ISS. He is currently the UNC site Principal Investigator for an Amgen sponsored observational research project. All remaining authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the North Carolina Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, SUDDEN team of researchers, and the North Carolina Translational and Clinical Sciences Institute at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The Wake County EMS Data System supports, maintains, and monitors EMS service delivery, patient care, and disaster preparedness for the Wake County, NC, community at large. This manuscript has been reviewed by Wake County EMS Data System investigators for scientific content and consistency of data interpretation with previous Wake County EMS Data System publications.

References

- 1.Lewis M.E., Lin F.C., Nanavati P. Estimated incidence and risk factors of sudden unexpected death. Open Heart. 2016;3(1) doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2015-000321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kong M.H., Fonarow G.C., Peterson E.D. Systematic review of the incidence of sudden cardiac death in the United States. J Am College Cardiol. 2011;57(7):794–801. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mirzaei M.J.G., Bogle B., Chen S., Simpson R., Jr Years of Life and Productivity Loss Because of Adult Sudden Unexpected Death in the United States. Med Care. 2019 doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larribau R., Deham H., Niquille M., Sarasin F.P. Improvement of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survival rate after implementation of the 2010 resuscitation guidelines. PloS one. 2018;13(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marijon E., Uy-Evanado A., Dumas F. Warning Symptoms Are Associated With Survival From Sudden Cardiac Arrest. Ann Internal Med. 2016;164(1):23–29. doi: 10.7326/M14-2342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muller D., Agrawal R., Arntz H.R. How sudden is sudden cardiac death? Circulation. 2006;114(11):1146–1150. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.616318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenfeld A., Christensen V., Daya M. Long enough to act? Symptom and behavior patterns prior to out-of-hospital sudden cardiac death. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2013;28(2):166–175. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3182452410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Binz A., Sargsyan A., Mariani R. Who Gets Warning Symptoms Before Sudden Cardiac Arrest? An In-Person Commun Based Invest Surv. 2017;136(suppl_1) A16948-A16948. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joodi G., Maradey J.A., Bogle B. Coronary Artery Disease and Atherosclerotic Risk Factors in a Population-Based Study of Sudden Death. J Gen Internal Med. 2020;35(2):531–537. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05486-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]