Key Points

Question

What is the association between general surgery resident grit and burnout, thoughts of attrition, and suicidal thoughts?

Findings

In this national survey study of 7464 general surgery residents, grit scores varied significantly among residents and residency programs. Residents with higher grit scores were 47% less likely to experience burnout, 39% less likely to have thoughts of attrition, and 42% less likely to report suicidal thoughts.

Meaning

The results of this survey study suggest that, among all US general surgery residents, there was an inverse association between grit and burnout, thoughts of attrition, and suicidal thoughts.

This survey study investigates the association between US general surgery resident grit and burnout, thoughts of attrition, and suicidal thoughts.

Abstract

Importance

Grit, defined as perseverance and passion for long-term goals, is predictive of success and performance even among high-achieving individuals. Previous studies examining the effect of grit on attrition and wellness during surgical residency are limited by low response rates or single-institution analyses.

Objectives

To characterize grit among US general surgery residents and examine the association between resident grit and wellness outcomes.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A cross-sectional national survey study of 7464 clinically active general surgery residents in the US was administered in conjunction with the 2018 American Board of Surgery In-Training Examination and assessed grit, burnout, thoughts of attrition, and suicidal thoughts during the previous year. Multivariable logistic regression models were constructed to assess the association of grit with resident burnout, thoughts of attrition, and suicidal thoughts. Statistical analyses were performed from June 1 to August 15, 2019.

Exposures

Grit was measured using the 8-item Short Grit Scale (scores range from 1 [not at all gritty] to 5 [extremely gritty]).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was burnout. Secondary outcomes were thoughts of attrition and suicidal thoughts within the past year.

Results

Among 7464 residents (7413 [99.3%] responded; 4469 men [60.2%]) from 262 general surgery residency programs, individual grit scores ranged from 1.13 to 5.00 points (mean [SD], 3.69 [0.58] points). Mean (SD) grit scores were significantly higher in women (3.72 [0.56] points), in residents in postgraduate training year 4 or 5 (3.72 [0.58] points), and in residents who were married (3.72 [0.57] points; all P ≤ .001), although the absolute magnitude of the differences was small. In adjusted analyses, residents with higher grit scores were significantly less likely to report duty hour violations (odds ratio [OR], 0.85; 95% CI, 0.77-0.93), dissatisfaction with becoming a surgeon (OR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.48-0.59), burnout (OR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.49-0.58), thoughts of attrition (OR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.55-0.67), and suicidal thoughts (OR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.47-0.71). Grit scores were not associated with American Board of Surgery In-Training Examination performance. For individual residency programs, mean program-level grit scores ranged from 3.18 to 4.09 points (mean [SD], 3.69 [0.13] points).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this national survey evaluation, higher grit scores were associated with a lower likelihood of burnout, thoughts of attrition, and suicidal thoughts among general surgery residents. Given that surgical resident grit scores are generally high and much remains unknown about how to employ grit measurement, grit is likely not an effective screening instrument to select residents; instead, institutions should ensure an organizational culture that promotes and supports trainees across this elevated range of grit scores.

Introduction

Burnout in medicine is receiving considerable attention owing to its detrimental effect on health care professionals and their patients.1,2,3,4 The hardships and stress experienced during general surgery residency can disproportionately compromise wellness among surgical residents compared with other specialties.5,6 Moreover, resident attrition (leaving a training program) has long been a concern in surgery.7 The general surgery resident attrition rate is greater than that of other surgical specialties.8,9,10,11 Historical audits and recent studies report 1 in 5 categorical general surgery residents will leave to pursue an alternative career.11,12,13 Finally, and most concerning, among all residents training at Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)–accredited programs across all specialties, suicide is the leading cause of death in male residents and the second most common cause of death overall.14

Grit, a personality trait defined as perseverance and passion for long-term goals, is predictive of success and performance in many professions and areas of society independent of traditional cognitive assessments (eg, intelligence quotient) or prior achievement.15 Individuals with higher grit are more likely to graduate from the US Military Academy, reach the finals of the National Spelling Bee, and obtain higher educational achievements during their lives.15 Higher grit scores are also associated with improved mental well-being and increased resilience.16

Over the last decade, researchers have begun exploring the association between grit and trainee wellness. In general surgery residents, studies show an inverse association between grit and burnout and attrition, both of which are markers of compromised wellness.17,18,19 However, these studies were limited by a number of design and data considerations, including sampling bias, selection bias, low response rates, and/or inclusion of a small number of participating institutions. We used data from a comprehensive national survey of residents in all ACGME-accredited US general surgery residency programs to (1) characterize the grit of US general surgery residents, (2) assess variation in residency program–level grit, and (3) examine the association of resident grit with resident burnout, thoughts of attrition, and suicidal thoughts.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

In collaboration with the American Board of Surgery (ABS), a voluntary, multiple-choice survey was administered to all examinees from ACGME-accredited general surgery training programs immediately following the January 2018 American Board of Surgery In-Training Examination (ABSITE). The survey was preceded by a statement explaining that the purpose of the survey was research, the data would be deidentified before analysis, and programs would never have access to individual responses. There were no incentives or disincentives to participate in the survey. Responses were collected by the ABS and deidentified before transferring to Northwestern University for analysis. After review of this survey study, the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board office determined that it did not meet the definition of human subjects research. Survey participation was taken as consent because survey participation was elective. This study followed the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) guidelines.

Survey Instrument

Survey items were adapted from previously published and validated instruments and included content on resident wellness, duty hour adherence, and grit.20,21,22 Pretest cognitive interviews were conducted with a sample of general surgery residents to assess overall survey coherence, balance, and clarity. The survey was then iteratively revised and retested with a larger sample of general surgery residents from multiple institutions.

Grit was measured using the Short Grit Scale (GRIT-S), a validated 8-item questionnaire to which individuals respond on a 5-point Likert scale: “very much like me,” “mostly like me,” somewhat like me,” “not much like me,” and “not like me at all.” Four items are reverse coded.22 Individual scores were summed and then divided by 8. Final scores ranged from 1 (not at all gritty) to 5 (extremely gritty). Grit was used as a continuous variable throughout the study.

Characteristics and Wellness Outcomes

Resident and program characteristics provided by the ABS included sex, postgraduate year, 2018 ABSITE performance, program size, program type, and program location (Table 1). Residents reported their relationship status. Residents also reported the number of months during which they exceeded the ACGME 80-hour-per-week maximum, averaged over a 4-week period (dichotomized for analysis as 0 vs any month with a violation) within their current academic year. Resident satisfaction with duty hour regulations, time for rest, and the decision to become a surgeon were evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale (dichotomized for analysis into “satisfied,” ie, very satisfied/satisfied, vs “dissatisfied,” ie, neutral/dissatisfied/very dissatisfied). Program-level passage rates for the ABS Qualifying and Certifying Examinations were provided by the ABS. As prior work suggested that top-ranked health care institutions might be more stressful learning environments with differential effects on trainees (ie, some trainees thrive and some do not), residency program affiliation with 2018-2019 US News and World Report “Honor Roll” hospitals was used as an indicator of program ranking.23

Table 1. General Surgery Resident Characteristics From 262 General Surgery Training Programs in the US.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | Mean (SD) grit score, points |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | 7464 (100) | 3.69 (0.58) |

| Male | 4469 (60.2) | 3.67 (0.59) |

| Female | 2956 (39.8) | 3.72 (0.56) |

| Postgraduate year | ||

| 1 | 2131 (28.6) | 3.70 (0.57) |

| 2 or 3 | 2911 (39.0) | 3.66 (0.58) |

| 4 or 5 | 2420 (32.4) | 3.72 (0.58) |

| Relationship status | ||

| Married | 3130 (42.2) | 3.72 (0.57) |

| Relationship | 2340 (31.6) | 3.67 (0.58) |

| No relationship | 1812 (24.4) | 3.66 (0.58) |

| Divorced or widowed | 131 (1.8) | 3.66 (0.60) |

| Program size (total No. of residents) | ||

| Quartile 1 (6-25) | 2053 (27.5) | 3.70 (0.58) |

| Quartile 2 (26-37) | 1736 (23.3) | 3.66 (0.58) |

| Quartile 3 (38-51) | 1933 (25.9) | 3.69 (0.57) |

| Quartile 4 (52-81) | 1740 (23.3) | 3.71 (0.57) |

| Program type | ||

| Academic | 4477 (60.2) | 3.69 (0.58) |

| Community | 2743 (36.9) | 3.69 (0.57) |

| Military | 219 (2.9) | 3.69 (0.55) |

| Program location | ||

| Northeast | 2436 (32.7) | 3.69 (0.61) |

| Southeast | 1519 (20.4) | 3.70 (0.56) |

| Midwest | 1580 (21.2) | 3.69 (0.57) |

| Southwest | 880 (11.8) | 3.70 (0.56) |

| West | 1037 (14.0) | 3.67 (0.57) |

| 2018 ABSITE score | ||

| Quartile 1 (lowest) | 1882 (25.2) | 3.68 (0.60) |

| Quartile 2 | 1990 (26.7) | 3.69 (0.57) |

| Quartile 3 | 1831 (24.5) | 3.69 (0.57) |

| Quartile 4 (highest) | 1759 (23.6) | 3.70 (0.57) |

| 80-h Rule violations in the last 6 mo | ||

| Zero (none) | 4519 (61.0) | 3.73 (0.59) |

| At least 1 mo with a violation | 2891 (39.0) | 3.63 (0.56) |

| Satisfaction with duty hour regulations | ||

| Satisfied | 5218 (70.4) | 3.74 (0.60) |

| Dissatisfied/neutral | 2191 (29.6) | 3.58 (0.57) |

| Satisfaction with time for rest | ||

| Satisfied | 3533 (47.7) | 3.77 (0.57) |

| Dissatisfied/neutral | 3876 (52.3) | 3.62 (0.58) |

| Satisfaction with becoming a surgeon | ||

| Satisfied | 5622 (75.9) | 3.75 (0.60) |

| Dissatisfied/neutral | 1787 (24.1) | 3.51 (0.58) |

| Thoughts of attrition | ||

| Yes/neutral | 1756 (23.7) | 3.53 (0.58) |

| No | 5653 (76.3) | 3.74 (0.56) |

| Burnouta | ||

| Yes | 2849 (38.5) | 3.57 (0.59) |

| No | 4560 (61.6) | 3.77 (0.57) |

| Suicidal thoughts | ||

| Yes | 333 (4.5) | 3.47 (0.60) |

| No | 7061 (95.5) | 3.70 (0.57) |

Abbreviation: ABSITE, American Board of Surgery In-Training Examination.

Burnout defined as at least weekly symptoms of emotional exhaustion or depersonalization.

To measure burnout, a modified, abbreviated Maslach Burnout Inventory Human Services Survey for Medical Personnel, a well-validated tool for assessing burnout, was used.21,24,25,26 The 6-item instrument assessed emotional exhaustion and depersonalization with 3 questions for each subscale. Because of survey administration and design concerns, the abbreviated Maslach Burnout Inventory Human Services Survey for Medical Personnel item responses were modified from the original 7-point scale to a 5-point scale: never, a few times a year or less, a few times a month, a few times a week, or every day, as has been done in previous published reports.27,28 As these subscale scores represent a continuum from engagement (lower scores, less frequent symptoms) to burnout (higher scores, more frequent symptoms), we kept them as continuous variables when possible. Burnout was defined as reporting at least weekly symptoms of either emotional exhaustion or depersonalization.2

Thoughts of attrition were assessed with the survey item, “I have considered leaving my program in the last year.” Responses were measured on a 5-point Likert scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” and then dichotomized for analysis into “yes” (strongly agree/agree/neutral) and “no” (disagree/strongly disagree). Suicidal thoughts were assessed with a validated, single question: “During the past 12 months, have you had thoughts of taking your own life?”29 Affirmative responses were immediately followed by a screen providing the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline and urging residents to reach out to their program directors for assistance. No active outreach was possible because all data were deidentified, and confidentiality was assured as a precondition of survey completion.

Statistical Analysis

Resident and program characteristics were described using univariate statistics and frequencies. Bivariate associations were examined with t tests and 1-way analysis of variance tests for continuous and categorical data, respectively. Multivariable logistic regression models were constructed to examine the association between grit and each outcome of interest, adjusting for gender, postgraduate year, relationship status, and program size. Grit was used in each regression model as a continuous predictor variable, meaning the odds ratios (ORs) for the outcome variable are for each 1-unit change in grit score. To examine the unique effect of grit on wellness outcomes in this study independent of established effects of burnout on other wellness outcomes, burnout was included as an independent variable in all models except when it was used as the outcome (models 2-7 were adjusted for resident burnout) because burnout is associated with both thoughts of attrition and suicidality.1,2 All models were estimated with robust SEs to account for resident clustering within programs. Multivariable analyses included only those residents who provided complete survey responses. Individual resident grit scores were summed and divided by the number of residents in each program to achieve a mean program-level grit score. Program-level associations were examined using Pearson correlation coefficients. All tests were 2-sided with significance set at 0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted from June 1 to August 15, 2019, using Stata, version 15.1 (StataCorp LLC).

Results

Of 8301 surgical residents taking the 2018 ABSITE from all 263 ACGME-accredited programs, 837 were not clinically active and excluded from survey participation. Forty-nine of the remaining residents did not provide responses to any survey items and were dropped from analysis. One program contained only 2 residents, so these residents were dropped as well. A total of 7413 of 7464 residents (99.3%) responded to the survey.

Residents were predominantly male (4469 [60.2%]), married (3130 [42.2%]), and training at an academic program (4477 [60.2%]) (Table 1). In the 6 months preceding the survey, 2891 residents (39.0%) reported at least 1 month in which they averaged more than 80 hours per week over the course of the month. More than half of residents (3876 [52.3%]) were dissatisfied with their time for rest, and nearly a quarter (1787 [24.1%]) were dissatisfied with their decision to become a surgeon.

Resident-Level Grit and Wellness Outcomes

The mean (SD) grit score for the entire cohort was 3.69 (0.58) points on a 5-point scale (range, 1.13-5.00 points) (Table 1). Significantly higher grit scores (all P ≤ .001) were noted for women (mean [SD], 3.72 [0.56] points vs male, 3.67 [0.59] points), residents in their first postgraduate year (3.70 [0.57] points vs postgraduate year 2 or 3, 3.66 [0.58] points), those in postgraduate year 4 or 5 (3.72 [0.58] points vs postgraduate year 2 or 3, 3.66 [0.58] points), and those who were married (3.72 [0.57] points vs not married but in a relationship, 3.67 [0.58] points; not married and not in a relationship, 3.66 [0.58] points; and divorced or widowed, 3.66 [0.60] points). Furthermore, residents reporting no duty hour violations (4519 [61.0%]; mean [SD], 3.73 [0.59] points), satisfaction with time for rest (3533 [47.7%]; mean [SD], 3.77 [0.57] points), or satisfaction with their decision to become a surgeon (5622 [75.9%]; mean [SD], 3.75 [0.60] points) also had significantly higher grit scores (all P ≤ .001). The mean grit scores across ABSITE quartiles were not significantly different.

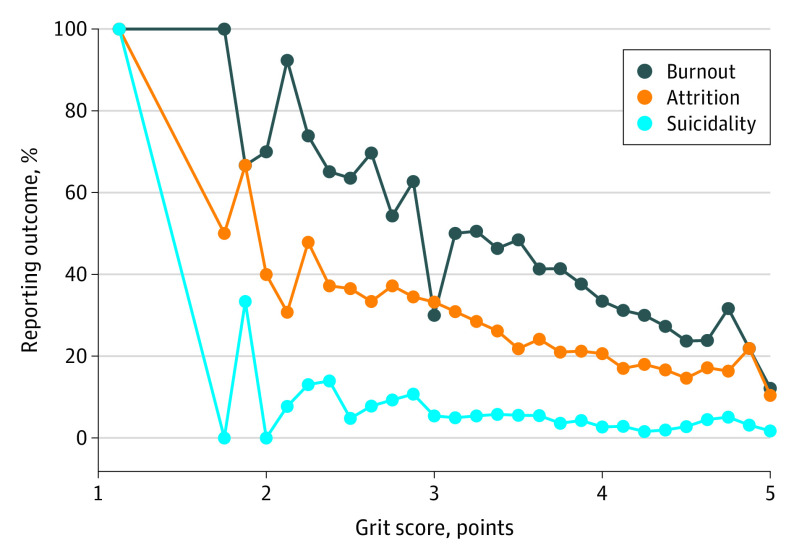

Burnout, defined as at least weekly symptoms of either emotional exhaustion or depersonalization, was reported by 2849 of 7409 residents (38.5%) (Table 1). Thoughts of attrition over the past year were reported by 1756 residents (23.7%). A total of 333 residents (4.5%) reported having suicidal thoughts. Grit scores were inversely correlated with burnout, thoughts of attrition, and suicidal thoughts (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Percent of Residents Reporting Burnout, Thoughts of Attrition, and Suicidal Thoughts by Grit Score.

Grit was measured with the 8-item Short Grit Scale. Scores ranged from 1 (low grit) to 5 (high grit). Burnout was defined as at least weekly symptoms of emotional exhaustion or depersonalization.

In multivariable analyses (Table 2), grit was assessed as a continuous variable. For each 1-unit change in grit scores, residents with higher grit scores were 47% less likely to report burnout symptoms compared with residents who had lower grit scores (eg, grit score 4.1 points vs 3.1 points; OR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.49-0.58). Compared with residents who had lower grit scores, residents with higher grit scores were also 39% less likely to report thoughts of attrition (OR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.55-0.67) and 42% less likely to report suicidal thoughts (OR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.47-0.71).

Table 2. Associations Between Higher Grit Scores and Wellness Outcomes.

| Outcome | OR (95% CI)a | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1b: burnout | ||

| Yes | 0.53 (0.49-0.58) | <.001 |

| No | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Model 2c: thoughts of attrition | ||

| Yes | 0.61 (0.55-0.67) | <.001 |

| No | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Model 3: suicidal thoughts | ||

| Yes | 0.58 (0.47-0.71) | <.001 |

| No | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Model 4: 80-h violations | ||

| Zero (none) | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Any month with a violation | 0.85 (0.77-0.93) | <.001 |

| Model 5: satisfaction with duty hour regulations | ||

| Satisfied | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Dissatisfied | 0.69 (0.63-0.76) | <.001 |

| Model 6: satisfaction with time for rest | ||

| Satisfied | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Dissatisfied | 0.72 (0.65-0.79) | <.001 |

| Model 7: satisfaction with becoming a surgeon | ||

| Satisfied | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Dissatisfied | 0.53 (0.48-0.59) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio.

The ORs in the table are for each interval change in grit score, ie, a general surgical resident with a grit score of 4.1 is 47% less likely to experience burnout compared with a general surgery resident with a grit score of 3.1.

Model 1 adjusts for gender, postgraduate year, relationship status, and program size.

Models 2-7 adjust for gender, postgraduate year, relationship status, program size, and burnout.

Furthermore, residents with higher grit scores were 15% less likely to report 1 or more months with a violation of the 80-hour rule (OR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.77-0.93), 31% less likely to report dissatisfaction with duty hour regulations (OR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.63-0.76), 28% less likely to report dissatisfaction with time for rest (OR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.65-0.79), and 47% less likely to report dissatisfaction with becoming a surgeon (OR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.48-0.59).

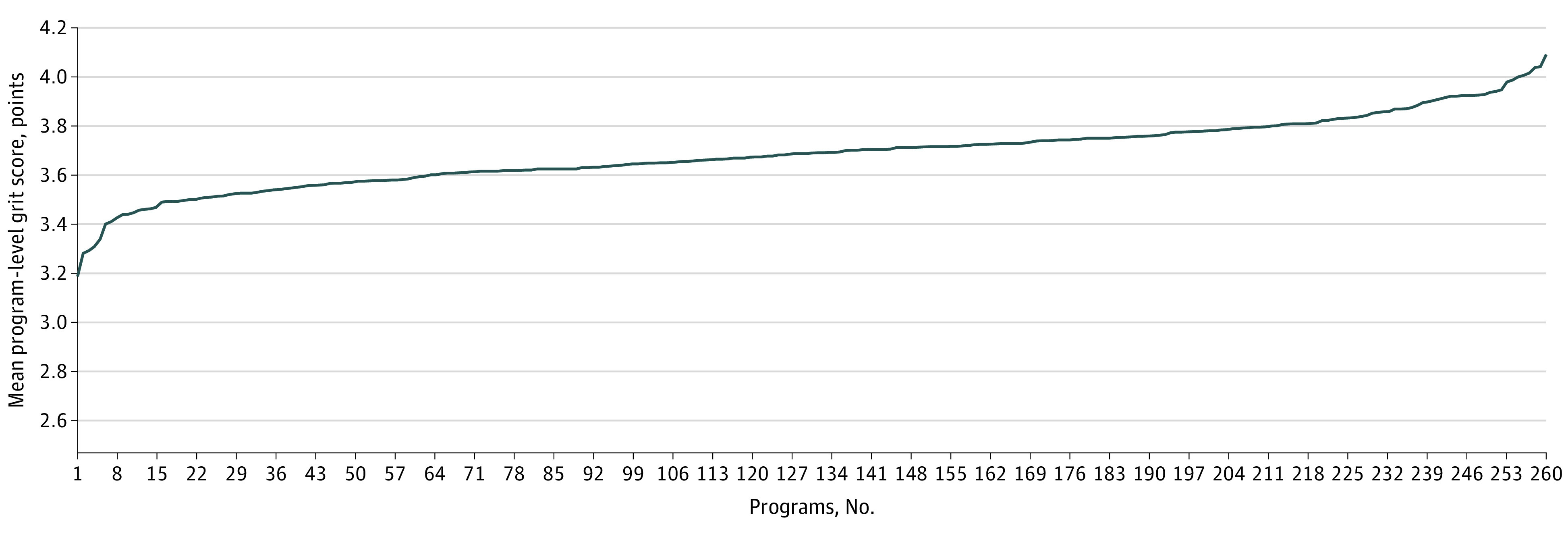

Program-Level Grit

Program-level analyses demonstrated considerable variation among general surgery training programs. For individual programs, mean program-level grit scores ranged from 3.18 to 4.09 points (mean [SD], 3.69 [0.13] points) (Figure 2). Higher mean program-level grit scores were associated with higher program-level qualifying (written) examination passage rates (r = 0.04; P < .01) but not program-level certifying (oral) examination passage rates (r = −0.01; P > .05). Residents at training programs affiliated with US News and World Report Honor Roll Hospitals had somewhat higher mean grit scores (OR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.00-1.28).

Figure 2. Variation in Mean Program-Level Grit Scores for 262 General Surgery Training Programs in the US.

Program-level grit scores range from 3.18 to 4.09 points.

Discussion

In this national survey of all ACGME-accredited US general surgery residency programs and more than 99% of clinically active general surgery residents, grit varied significantly among residents and residency programs. In addition, there was an inverse association between grit and burnout, thoughts of attrition, and suicidal thoughts. Even after adjusting for resident burnout, residents with higher grit scores were still 39% less likely to report thoughts of attrition and 42% less likely to report suicidal thoughts.

This study provides the largest and most extensive evaluation to date of grit and wellness outcomes in medicine. The mean grit score in this national study was higher than that of age-matched peers in the general population and similar to prior reports including general surgery residents and other high-achieving professionals.15,18,30,31 Female residents had slightly higher grit scores (statistically higher, but similar absolute values) compared with male residents. One explanation for this finding may be the existence of differential hurdles that male and female residents face, which lead to differential competitive selection processes that require greater grit among women to progress.32,33 In order to reach similar levels of accomplishment, female trainees experience more bias, sex discrimination, and sexual harassment compared with their male colleagues at each level of training.2,34 As a result, female trainees who persevere despite these barriers may have higher grit compared with their male colleagues.

Previous studies have demonstrated associations between lower grit scores and compromised wellness among trainees in multiple different specialties.17,18,19,31,35,36 In a longitudinal study, grit was inversely associated with the burnout domains of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization.17 A separate, single-institution evaluation examined 141 residents from multiple subspecialties and found that residents with higher grit scores reported significantly lower rates of burnout 6 months later; however, in a subgroup analysis of 40 general surgery residents, grit was not significantly associated with overall burnout or any of the individual burnout domains.31 An inverse association between grit and burnout exists in studies of emergency medicine residents35 and neurosurgery residents.36 However, these studies are limited by relatively small sample sizes from single institutions or have low response rates, which limit generalizability and make them vulnerable to nonresponse bias.

Despite the abolition of pyramidal training programs by the Residency Review Committee for Surgery in 1996 and the implementation of duty hour reforms by the ACGME in 2003, 2011, and again in 2016, high attrition rates among general surgery residents persist at around 20% over the course of training, exceeding attrition rates in other residencies.8,9,10,11,13,37 Individual reasons for leaving residency vary, but studies demonstrate higher attrition in residents lacking a realistic understanding of surgical residency demands.7,38 Similar to our findings examining all residency programs in the US, studies demonstrate an inverse association between grit and thoughts of attrition but not a significant association between grit and actual attrition. Although we found that resident grit was associated with hospital rankings, the reasons for this association are unclear; however, this finding should not be justification alone for choosing a particular program, as a recent study demonstrates higher actual attrition rates among general surgery interns who chose training programs based on reputation.39

Studies evaluating the association between grit and suicide in health care are lacking. Evidence from studies of non–health care professionals suggests an inverse association between grit and suicidal ideation. In a study of 209 college students, investigators found a near absence of suicidal ideations in individuals endorsing both high gratitude and high grit.40 Furthermore, high levels of grit may buffer the severity of suicidal ideation after negative life experiences, whereas individuals with lower grit showed higher rates of suicidal ideation after negative experiences.41,42 We found that higher grit scores were significantly associated with a lower likelihood of suicidal thoughts in accordance with previous studies of nonmedical populations.

Individuals with high grit are defined by their ability to overcome hardships in part because they can focus beyond negative events to their long-term goal. In practice, these individuals have shown a propensity for additional achievement in the future compared with cognitively matched peers (ie, similar standardized test scores).15 This outcome has led some to suggest the inclusion of grit scales in the medical school and residency admissions processes.43,44 However, the available evidence does not support the use of grit scales as screening tools for such high-stakes decision-making, and this practice should be repudiated.45 First, grit instruments have not been validated as screening tools in any setting, as they have the same limitations as other self-report instruments, including reference bias (eg, one respondent’s “rarely” may be another respondent’s “often”),46 acquiescence bias (eg, tendency for respondent to agree rather than disagree with the statement),47 or purposeful misrepresentation of their true response for any number of reasons.48 Second, surgical residents, having already passed multiple rounds of selection during premedical and medical training, have high grit as a population compared with aged-matched peers.18 Any population will demonstrate a range of grit scores, even a highly selected one, but whether that variation is meaningful is unknown, especially given the small absolute differences in grit scores between certain cohorts seen in this study (ie, gender, clinical postgraduate year, or relationship status). Third, although grit may be associated with future success, which in the case of medical trainees equals completion of training and beginning a career as a practicing physician, it does not comment on the quality of the physician at the completion of training. Are grittier residents better technical surgeons? Do they provide a higher quality of care? Do they have better relationships with patients? The association between grit and care quality remains unclear. Finally, even “gritty” residents are susceptible to burnout, thoughts of attrition, and suicidal ideation (Figure 1), a finding also demonstrated in the most resilient of physicians.49 This reality highlights the limitation of relying on personal attributes to reduce burnout and promote physician wellness, as well as the importance of system-level wellness determinants.49,50

Ethical and psychometric concerns limit the screening ability of any grit scale; however, the foundational grit concepts of passion and perseverance and the strong associations with wellness outcomes as demonstrated in the current study offer insight into developing and maintaining a wellness-centric organization. Although grit is often conceptualized as an innate trait, like all psychological traits, grit is influenced by experience as well as genes.51 At the individual level, resilience training and positive psychological training (ie, growth mindset) may increase grit by providing a sense of hope and control over outcomes, particularly in difficult situations.51 At the organizational level, promoting professional development in areas that interest a health care professional and that foster a sense of purpose can increase grit and protect against burnout. For example, protected time for a physician to pursue an area of professional development (eg, research, education, community outreach, or mentorship) that they are passionate about significantly reduces the risk of burnout.52 The formation of an organizational culture that supports grit development may effectively mitigate burnout and promote wellness despite the immutable challenges facing health care professionals.

Limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, owing to the anonymity afforded participants and our cross-sectional design, we cannot specify the direction of the association between grit and resident wellness or examine the association between grit and actual attrition. Second, survey questions asked residents to recall events that occurred up to 12 months prior; thus, the responses to these questions are subject to recall bias. Third, the timing of survey administration immediately following the ABSITE may influence resident wellness reporting. However, analysis of burnout progression suggests that burnout is robust to isolated, infrequent stress exposure and more reflective of stress over time. Furthermore, residents may experience relief at the end of the test, which could mitigate much of this concern.53 Finally, although we used the GRIT-S as is, other researchers have recently raised questions regarding its psychometric properties, including whether it truly measures a single, coherent construct.54 This question is beyond the scope of our current work and requires a separate psychometric evaluation of GRIT-S in our population.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated significant variation in grit among US general surgery residents and suggests that grit is independently associated with burnout, thoughts of attrition, and suicidal ideation even after adjusting for basic sociodemographic and residency program characteristics. These results, along with previous research by other investigators and institutions, should encourage stakeholders to incorporate grit assessment in their efforts to improve resident and physician wellness; however, great care and caution must be observed in doing so. Grit is a construct with explanatory power in understanding systematic variation in personal achievement and wellness. More work is necessary to translate these empirical findings into practical action amid ongoing efforts to promote the well-being of health care professionals throughout their career trajectories.

References

- 1.Hewitt DB, Ellis RJ, Chung JW, et al. Association of surgical resident wellness with medical errors and patient outcomes. Ann Surg. Published online April 8, 2020. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu YY, Ellis RJ, Hewitt DB, et al. Discrimination, abuse, harassment, and burnout in surgical residency training. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(18):1741-1752. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1903759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Notice of retraction: Panagioti M, et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(10):1317-1331. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):931. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.West CP, Tan AD, Shanafelt TD. Association of resident fatigue and distress with occupational blood and body fluid exposures and motor vehicle incidents. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(12):1138-1144. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.07.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, et al. Prevalence of burnout among physicians: a systematic review. JAMA. 2018;320(11):1131-1150. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.12777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Low ZX, Yeo KA, Sharma VK, et al. Prevalence of burnout in medical and surgical residents: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(9):E1479. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16091479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellis RJ, Holmstrom AL, Hewitt DB, et al. A comprehensive national survey on thoughts of leaving residency, alternative career paths, and reasons for staying in general surgery training. Am J Surg. 2020;219(2):227-232. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2019.10.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hatton MP, Loewenstein J. Attrition from ophthalmology residency programs. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138(5):863-864. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.06.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prager JD, Myer CM IV, Myer CM III. Attrition in otolaryngology residency. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145(5):753-754. doi: 10.1177/0194599811414495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu DW, Hartman ND, Druck J, Mitzman J, Strout TD. Why residents quit: national rates of and reasons for attrition among emergency medicine physicians in training. West J Emerg Med. 2019;20(2):351-356. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2018.11.40449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeo H, Bucholz E, Sosa JA, et al. A national study of attrition in general surgery training: which residents leave and where do they go? Ann Surg. 2010;252(3):529-534. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f2789c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bell RH Jr, Banker MB, Rhodes RS, Biester TW, Lewis FR. Graduate medical education in surgery in the United States. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87(4):811-823, v-vi. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2007.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Longo WE, Seashore J, Duffy A, Udelsman R. Attrition of categoric general surgery residents: results of a 20-year audit. Am J Surg. 2009;197(6):774-778. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.06.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yaghmour NA, Brigham TP, Richter T, et al. Causes of death of residents in ACGME-accredited programs 2000 through 2014: implications for the learning environment. Acad Med. 2017;92(7):976-983. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Duckworth AL, Peterson C, Matthews MD, Kelly DR. Grit: perseverance and passion for long-term goals. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;92(6):1087-1101. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kannangara CS, Allen RE, Waugh G, et al. All that glitters is not grit: three studies of grit in university students. Front Psychol. 2018;9:1539. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cortez AR, Winer LK, Kassam AF, et al. Exploring the relationship between burnout and grit during general surgery residency: a longitudinal, single-institution analysis. Am J Surg. 2020;219(2):322-327. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2019.09.041 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Burkhart RA, Tholey RM, Guinto D, Yeo CJ, Chojnacki KA. Grit: a marker of residents at risk for attrition? Surgery. 2014;155(6):1014-1022. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salles A, Lin D, Liebert C, et al. Grit as a predictor of risk of attrition in surgical residency. Am J Surg. 2017;213(2):288-291. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2016.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bilimoria KY, Chung JW, Hedges LV, et al. Development of the Flexibility in Duty Hour Requirements for Surgical Trainees (FIRST) trial protocol: a national cluster-randomized trial of resident duty hour policies. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(3):273-281. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.4990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McManus IC, Winder BC, Gordon D. The causal links between stress and burnout in a longitudinal study of UK doctors. Lancet. 2002;359(9323):2089-2090. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08915-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duckworth AL, Quinn PD. Development and validation of the Short Grit Scale (GRIT-S). J Pers Assess. 2009;91(2):166-174. doi: 10.1080/00223890802634290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ellis RJ, Hewitt DB, Hu YY, et al. An empirical national assessment of the learning environment and factors associated with program culture. Ann Surg.2019;270(4):585-592. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riley MR, Mohr DC, Waddimba AC. The reliability and validity of three-item screening measures for burnout: evidence from group-employed health care practitioners in upstate New York. Stress Health. 2018;34(1):187-193. doi: 10.1002/smi.2762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maslach C, Jackson S. Maslach Burnout Inventory human services survey for medical personnel. Accessed July 8, 2017. https://www.mindgarden.com/315-mbi-human-services-survey-medical-personnel

- 26.Desai SV, Asch DA, Bellini LM, et al. ; iCOMPARE Research Group . Education outcomes in a duty-hour flexibility trial in internal medicine. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(16):1494-1508. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reise SP, Haviland MG. Item response theory and the measurement of clinical change. J Pers Assess. 2005;84(3):228-238. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8403_02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edelen MO, Reeve BB. Applying item response theory (IRT) modeling to questionnaire development, evaluation, and refinement. Qual Life Res. 2007;16(suppl 1):5-18. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9198-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Massie FS, et al. Burnout and suicidal ideation among U.S. medical students. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(5):334-341. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-5-200809020-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halliday L, Walker A, Vig S, Hines J, Brecknell J. Grit and burnout in UK doctors: a cross-sectional study across specialties and stages of training. Postgrad Med J. 2017;93(1101):389-394. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salles A, Cohen GL, Mueller CM. The relationship between grit and resident well-being. Am J Surg. 2014;207(2):251-254. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weuve J, Tchetgen EJ, Glymour MM, et al. Accounting for bias due to selective attrition: the example of smoking and cognitive decline. Epidemiology. 2012;23(1):119-128. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318230e861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hernán MA, Alonso A, Logroscino G. Cigarette smoking and dementia: potential selection bias in the elderly. Epidemiology. 2008;19(3):448-450. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31816bbe14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dahlke AR, Johnson JK, Greenberg CC, et al. Gender differences in utilization of duty-hour regulations, aspects of burnout, and psychological well-being among general surgery residents in the United States. Ann Surg. 2018;268(2):204-211. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002700 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Dam A, Perera T, Jones M, Haughy M, Gaeta T. The relationship between grit, burnout, and well-being in emergency medicine residents. AEM Educ Train. 2018;3(1):14-19. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shakir HJ, Cappuzzo JM, Shallwani H, et al. Relationship of grit and resilience to burnout among U.S. neurosurgery residents. World Neurosurg. 2020;134:e224-e236. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.10.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khoushhal Z, Hussain MA, Greco E, et al. Prevalence and causes of attrition among surgical residents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(3):265-272. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.4086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Engelhardt KE, Bilimoria KY, Johnson JK, et al. A national mixed-methods evaluation of preparedness for general surgery residency and the association with resident burnout. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(9):851-859. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.2420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yeo HL, Abelson JS, Symer MM, et al. Association of time to attrition in surgical residency with individual resident and programmatic factors. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(6):511-517. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.6202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kleiman E, Adams L, Kashdan T, Riskind J. Gratitude and grit indirectly reduce risk of suicidal ideations by enhancing meaning in life: evidence for a mediated moderation model. J Res Pers. 2013;47:539-546. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2013.04.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blalock DV, Young KC, Kleiman EM. Stability amidst turmoil: grit buffers the effects of negative life events on suicidal ideation. Psychiatry Res. 2015;228(3):781-784. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.04.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marie L, Taylor SE, Basu N, et al. The protective effects of grit on suicidal ideation in individuals with trauma and symptoms of posttraumatic stress. J Clin Psychol. 2019;75(9):1701-1714. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shih AF, Maroongroge S. The importance of grit in medical training. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(3):399. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00852.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller-Matero LR, Martinez S, MacLean L, Yaremchuk K, Ko AB. Grit: a predictor of medical student performance. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2018;31(2):109-113. doi: 10.4103/efh.EfH_152_16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duckworth AL, Yeager DS. Measurement matters: assessing personal qualities other than cognitive ability for educational purposes. Educ Res. 2015;44(4):237-251. doi: 10.3102/0013189X15584327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pace CR, Friedlander J. The meaning of response categories: how often is “occasionally,” “often,” and “very often”? Res High Educ. 1982;17(3):267-281. doi: 10.1007/BF00976703 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Willem S, Melanie R, Jon AK, Eric MS. Comparing questions with agree/disagree response options to questions with item-specific response options. Sur Res Methods. 2010;4(1):61-79. doi: 10.18148/srm/2010.v4i1.2682 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones EE, Sigall H. The bogus pipeline: a new paradigm for measuring affect and attitude. Psychol Bull. 1971;76(5):349-364. doi: 10.1037/h0031617 [DOI]

- 49.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, et al. Resilience and burnout among physicians and the general US working population. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7):e209385. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.9385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brigham T, Barden C, Dopp AL, et al. A Journey to Construct an All-Encompassing Conceptual Model of Factors Affecting Clinician Well-Being and Resilience. National Academy of Medicine; 2018. doi: 10.31478/201801b [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Duckworth A.Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance. Scribner/Simon & Schuster; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129-146. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spiegler MD, Morris LW, Liebert RM. Cognitive and emotional components of test anxiety: temporal factors. Psychol Rep. 1968;22(2):451-456. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1968.22.2.451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Credé M, Tynan MC, Harms PD. Much ado about grit: a meta-analytic synthesis of the grit literature. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2017;113(3):492-511. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]