Abstract

Objective

To explore experiences, preferences and engagement with HIV testing and prevention among urban refugee and displaced adolescents and youth in Kampala, Uganda, with a focus on the role of contextual factors in shaping access and uptake.

Methods

This qualitative community‐based study with urban refugee and displaced youth aged 16–24 living in Kampala’s informal settlements involved five focus groups (FG), including two with young women, two with young men, and one with sex workers from March to May 2019. We also conducted five in‐depth key informant interviews. We conducted thematic analysis informed by Campbell and Cornish’s conceptualisation of material and symbolic contexts.

Results

Refugee/displaced youth participants (n = 44; mean age: 20.25, SD: 2.19; men: n = 17; women: n = 27) were from the Democratic Republic of Congo (n = 29), Rwanda (n = 11), Burundi (n = 3) and Sudan (n = 1). Participant narratives reflected material and symbolic contexts that shaped HIV testing awareness, preferences and uptake. Material contextual factors that presented barriers to HIV testing and prevention engagement included transportation costs to clinics, overcrowded living conditions that limited access to private spaces, low literacy and language barriers. Symbolic contexts that constrained HIV testing engagement included medical mistrust of HIV testing and inequitable gender norms. Religion emerged as an opportunity to connect with refugee communities and to address conservative religious positions on HIV and sexual health.

Conclusion

Efforts to increase access and uptake along the HIV testing and prevention cascade can meaningfully engage urban refugee and displaced youth to develop culturally and contextually relevant services to optimise HIV and sexual health outcomes.

Keywords: refugee and internally displaced, HIV testing, HIV self‐testing, stigma, Uganda, adolescent and youth

Introduction

Forty per cent of the world’s 79.5 million displaced persons are under 18 years old [1]. People in humanitarian contexts experience elevated exposure to sexual and gender‐based violence (SGBV), poverty, and unmet sexual and reproductive health (SRH) needs [2]. Barriers to accessing SRH services such as HIV prevention and testing in humanitarian contexts include a lack of information, insufficient healthcare services and language barriers [3, 4]. These SRH barriers may be exacerbated for young refugee/displaced persons [5] who often experience stigma, poverty, and are at a developmental phase where they value privacy [3, 4, 5]. Non‐judgmental and empowering enabling environments are key to facilitating access to, and uptake of, HIV preventive resources [6, 7].

Little is known, however, of refugee/displaced youths’ experiences and preferences for HIV testing or prevention services [2, 5, 8]. This is particularly true for urban refugee/displaced youth; there is a growing trend of urbanisation among refugees and displaced persons, [1, 9, 10] yet most sexual health research focuses on refugee settlements [11, 12]. Uganda hosts 1.4 million refugees [13]. More than 80,000 refugee and displaced persons live in the capital city Kampala [13] largely in informal settlements (slums) where they experience poverty, overcrowding, and precarious living environments [12]. There are critical HIV prevention gaps among young people in Uganda. Adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) aged 14–24 reported new HIV infections double that of male counterparts [14]; their reported HIV prevalence of 9.1% is threefold higher than male counterparts and higher than the national prevalence of 5.7% [15]. Less than 20% of refugee AGYW in Nakivale refugee settlement reported condom use during sex in the past 3 months [16]. Only 46% of young persons in Uganda aged 15–24 demonstrated HIV prevention knowledge [14].

While these youth HIV prevention gaps are notable, urban refugee/displaced youths' specific needs remain understudied. A study reported that lifetime HIV testing uptake is low (56%) among urban refugee/displaced youth in Kampala [4]. Among young women, adolescent SRH stigma was associated with poorer HIV testing outcomes [4]. STI testing was also suboptimal among this population, with 26% of urban refugee/displaced youth in Kampala ever testing for STI, and among those ever tested, nearly 40% reported a lifetime STI diagnosis [3]. Socio‐environmental factors such as stigma and food insecurity were associated with STI testing practices, underscoring the need to better understand the role of social environments in influencing engagement with HIV/STI services. Studies with refugee/displaced persons outside of Kampala also document the important role of the social environment. For instance, a study in Nakivale refugee settlement documented the primacy of meeting daily priorities of food, safety and shelter before engaging with HIV testing [17]. A study of young internally displaced persons in Gulu reported an HIV prevalence of 12.8%, with increased odds for persons with recent STI symptoms, and those reporting non‐consensual sexual debut [18]. Young refugee/displaced persons are at elevated risk for SGBV [19, 20], including in Kampala where more than half of young refugee women reported experiencing violence at 16 years old and above [21]. Together, these findings point to the urgent need to identify opportunities to improve access to HIV testing and prevention services among urban refugee/displaced youth [5].

We address key knowledge gaps regarding experiences and perspectives of the role of social environments in shaping engagement with HIV prevention [6, 22] among urban refugee and displaced youth aged 16–24 in Kampala. Specifically, we aimed to understand experiences accessing HIV prevention resources and testing among urban refugee/displaced youth in Kampala.

Methods

We conducted a qualitative study focused on HIV prevention and testing, including HIV self‐testing, among urban refugee/ displaced youth in Kampala, Uganda in collaboration with community and humanitarian agencies, academics and the Ministry of Health. Focus groups (n = 5) were conducted by trained interviewers with refugee/displaced youth living in five of Kampala’s informal settlements (Nsamyba, Katwe, Rubaga, Kansanga, Kabalagala). We held two focus groups (45 min in duration) with young women, two with young men, and one with refugee youth sex workers. Trained interviewers also conducted five in‐depth key informant (KI) interviews (30 min in duration) with persons working with refugee/displaced youth at community‐based and humanitarian agencies, and government and non‐government clinics providing HIV/STI services.

We hired and trained peer navigators, refugees aged 18–24 (n = 12, six women and six men) who lived in the target informal settlements to conduct purposive recruitment using word‐of‐mouth strategies for focus group participants. Trained interviewers were supported by translators to conduct focus groups (in English, French, Swahili, Kinyarwanda, Kirundi) and KI interviews. All participants provided written informed consent prior to the focus group/interview. Focus groups and KI interviews were audio‐recorded, transcribed verbatim, translated to English and verified with community collaborators. Focus group inclusion criteria: aged 16–24, able to provide informed consent, identify as a refugee, displaced person, or seeking asylum, or having parents who identified as a refugee, displaced or seeking asylum. We received research ethics approval from Mildmay Uganda, Uganda National Council for Science and Technology, and University of Toronto.

Our study was informed by the conceptualisation of health‐enabling social environments as interconnected material and symbolic contexts where persons are supported to practice behavioural changes such as HIV prevention [7]. The material context, inclusive of access to resources such as clinics, economic security and transportation, can enhance agency to participate in health care [7]. Symbolic components refer to environments in which persons’ dignity and value are recognised and respected, including cultural values and worldviews that shape perspectives of self, others and health practices [7]. We applied thematic analysis [23, 24] informed by this conceptualisation of context [7]. Transcripts were double coded using NVIVO software, following thematic analysis steps of producing initial codes, compiling codes into initial themes, refining themes into sub‐themes, discussing and member checking themes with community collaborators and refining themes [23]. Applying a contextual framework [7], we applied deductive analysis [23] to explore potential material (e.g. poverty) and symbolic (e.g. gender norms) factors associated with enabling environments. Thematic analysis [23] also involves inductive analysis – data‐driven coding – that involves exploring novel findings (e.g. medical mistrust).

Results

There were 44 focus group participants (mean age: 20.25, SD: 2.19, range 16–24), including young men (n = 17) and young women (n = 27). Participants’ countries of origin included Democratic Republic of Congo (n = 29), Rwanda (n = 11), Burundi (n = 3) and Sudan (n = 1). Most identified as refugees (n = 42/44; 95.5%), with one person (n = 1) identifying as undocumented and one (n = 1) seeking asylum. More than two‐thirds (n = 31/44; 70.5%) of participants had ever received an HIV test, and over three‐quarters (n = 35/44; 79.5%) were unemployed.

Material contextual factors

Transportation

Transportation and location emerged as a common concern regarding accessing HIV testing and other resources such as condoms. Participants described not knowing where services were and how to reach them, and reported having insufficient funds to pay for transportation due to poverty and widespread unemployment. As a key informant working at a hospital offering HIV testing described ‘They are complaining a lot about transport, food, clothes and rent… During counseling sessions and when you tell them to come on such a day, they will be like "if I don’t have transport I won’t come" since some of them are jobless’. (key informant [KI], hospital‐based HIV clinic)

This was corroborated by a refugee youth sex worker participant: ‘The government services are free but we have had issues with the transport …. if you use a motorcycle (boda boda) it is too much for us’. (FG, refugee sex workers, ID #3) Others discussed that they would not be able to access free HIV testing services if they needed to pay for the transportation costs: ‘there are some who stay very far [from HIV testing venues] but have friends who stay nearby who can tell them that "by the way, there is a free service here". If she is very far, transport becomes a challenge because not everyone is well facilitated with transport’. (focus group [FG], young women, aged 20–24, ID #3)

At times, refugee/displaced youth did not know the location of testing clinics. Participants recommended researchers and service providers offer transportation to clinics to mitigate these barriers. Most persons discussed that a far distance to clinics would be a deterrent from accessing HIV testing, as illustrated by a young woman participant: ‘There are both public and private hospitals like Mulago, Nsambya but you have to pay for some. Nsambya is also private but some are for free, but sometimes you find that someone stopped going for testing because the place is very far’. (FG, young women, aged 16–19, ID #8)

However, others discussed wanting to travel for HIV testing to a community far from their own due to privacy and confidentiality concerns. Some described that stigma would be a barrier for accessing testing in one’s community: ‘Even some people, if it is a community service they are scared of finding their friends there and how they will look at them. So they would rather stay at home than come to that community service for testing’. (FG, young women, aged 20–24, ID #1)

Private spaces

Access to private spaces for HIV self‐testing also emerged as a challenge, as urban refugee youth commonly lived in crowded homes. A key informant at a humanitarian agency described: ‘There are other factors that should also be looked at like privacy and confidentiality. When you look at refugees, you will find that ninety or ninety‐five per cent of refugee families live in slums. You might find a family of eight or nine people living in one room, a husband, wife and seven children, because of the poor living standards, they can't afford like a house whereby the children will be living in their separate rooms, so privacy and confidentiality at home will hinder that. In organisations like (blinded), we can provide a room and shade for self‐testing’.

Other considerations for HIV self‐testing in informal settlements were private spaces to dispose of HIV self‐test kits: ‘if a family member gives you a test kit then they would want to know the results, even a friend, even if they don't ask you directly but still will try to find a way to ask some questions, like "where did you dispose it?" such that I go and have a look at it’. (KI, sex work agency)

Participants across focus groups with adolescent boys and young men identified pharmacies as a good place to access HIV test‐kits and condoms. To illustrate: ‘the best way would be like the way we distribute condoms if we put them (HIV‐ST kits) at different pharmacies and a person can pick them at any time’. (FG, young men, aged 16–19, ID #1)

Literacy

Literacy emerged as another material barrier to being able to access HIV‐ST. For instance, a participant described ‘in case a person is educated, it is easy for him to read and understand but how about those who are not educated? She can’t read and understand anything’. (FG, young women, aged 20–24, ID #1) Others discussed how literacy varied, in part due to not being able to access education and disrupted schooling : ‘Some people are literate others are not, they never went to school’. (FG, young men, aged 20–24, ID #8) When asked to describe the literacy situation among refugee youth, a key informant at a young refugee agency described: ‘50% can read and write’.

Some participants described that even if there were illustrations, that may not be sufficient for persons with low literacy to understand: ‘if you are illiterate even pictures become complicated to interpret, remember even at school you are told, “study the pictures.” Those who went to school are used to interpreting pictures, but not the illiterate’. (FG, young women, aged 20–24, ID #3) To access persons with low literacy, participants suggested using creative mediums such as community radio.

Language

Language barriers emerged as a challenge for HIV testing, and as a barrier to accessing healthcare more generally: ‘in most cases when they go to these health centres, the language is a problem and they feel like, maybe they did not understand me very well, maybe I was not treated very well’. (KI, young refugee agency) This quotation also illustrated the potential for misunderstanding and negative healthcare experiences due to language barriers.

Participants also suggested that all materials regarding HIV prevention and HIV self‐testing be provided in multiple languages: ‘Some of them cannot understand the language in which the instructions are written’. (FG, young women, aged 16–19, ID #6)

Symbolic context

Religion

Participants highlighted the important role that religion played in their communities and suggested that HIV outreach leverage connections that people had with religious institutions. Participants described that religion for refugees remained an important way to retain cultural ties with communities and countries of origin: ‘most of us depend on religion in our country. Though we are refugees here, we are still having the same culture we had before’. (FG, young men, aged 20–24, ID #6) For this reason, many participants recommended HIV and STI outreach target churches.

There were alternative perspectives regarding religion. For instance, some noted challenges with this approach, as religious leaders may be unsupportive toward HIV prevention: ‘I suspect that the perception of pastors, they may have some prejudice. To some, using a condom is a sin. But we can use the leadership of the churches, so, if we call them in the meeting, train them, discuss with them, so, I think and believe they can do testing and spread the message to other churches’. (KI, youth refugee agency) This concern was also corroborated by a KI at a humanitarian agency: ‘when we organize them [HIV prevention programs] at churches, mainly religious leaders don't allow us to distribute condoms, because they believe that when we distribute condoms we are giving them a chance to fornicate, that we are supporting adultery’.

Medical mistrust

Mistrust of healthcare workers conducting community‐based outreach focused on refugees emerged as a barrier to HIV testing uptake. A participant discussed: ‘We fear also these people that are coming in our area to do the (HIV) test. Because, when they are coming in our areas we fear and ask ourselves, “are they the real people that are supposed to test? Are they not going to give us the virus?” Do we trust them more than we do the hospitals? So, I think it depends on the religion, culture and the community you’re staying in and the people you are staying with.’ (FG, young men, aged 20–24, ID #6)

This medical mistrust may in part be due to the understanding of HIV as a Western illness: ‘they might reject [testing], you know some people might say, “these are western things, maybe there’s a disease they may want to spread.” So, maybe people may have never tried testing because of that attitude, they might think they would want to spread something’. (KI, refugee youth agency) Others discussed that they understood HIV antibodies were in the blood, so they did not trust an oral HIV self‐test kit.

Inequitable gender norms

Participants described inequitable gender norms produced contexts of SGBV across trajectories of the refugee journey. Inequitable gender norms reduced adolescent girls’ and young women’s agency in sexual relationships and harmed their intimate relationships, contributed to child and early marriage, and SGBV was exacerbated among sex working refugees. Participants discussed SGBV targeting women as a weapon of war with lasting impacts of trauma on women and intimate partners: ‘During flight when they are travelling or moving from their country of origin, in their transit they get a number of SGBV issues like rape, soldiers rape them. Even when you look at the number of refugees who are HIV positive under our care, because now we have like four hundred refugees who are on ART, who are HIV positive. But when you talk to them, they are both young and old, the majority were raped during flight when they were trying to get refuge into Uganda, rebels raped them. Rebels use that rape tactic to traumatize those women or those families because you find that they can tie the husband on the tree and they rape the wife, like five soldiers, while the husband is watching so that they traumatize the husband’. (KI, humanitarian agency)

Inequitable gender norms constrained women’s agency in heterosexual relationships. Young women shared that asking partners to test could harm their marriage: ‘in my community, in Burundi, if you keep on showing that you don't trust your partner, then there is already an issue, you are breaking the marriage’. (FG, young women, aged 20–24, ID#2) Another participant described that young women had less agency in intimate partnerships than friendships: ‘Some girlfriends when we are together, we can talk, you are safe. But when you are with your boyfriend, you feel inferior, what the boyfriend tells you is what you follow’ (FG, young women, aged 16–19, ID #8). These relationship power discrepancies were in part attributed to the young age at which refugee girls and young women often married: ‘for refugees, it is from eighteen, but we have even young mothers or child mothers, but for marriage it is eighteen and nineteen. Those are very common, and you find refugee women of twenty‐two years having like three kids’. (KI, refugee youth agency)

Sex workers experienced harassment by police that limited HIV prevention outreach: ‘On giving out condoms and lubricant, we are sometimes a bit limited by police where by they arrest you, who is giving them such things. But still we find out ways of giving them out because at night is when they are on demand more…do you know how many times we have fallen into a choking grip by them? Because of giving out condoms’. (KI, sex worker agency)

To sum up, gender differences emerged regarding place of access, medical mistrust and the impact of gender norms. First, while both young men and women spoke of the importance of transportation and location to facilitate HIV testing uptake, young men were more likely to discuss preferences for accessing testing outside of their community due to confidentiality concerns, while young women discussed preferences for HIV testing close to home to reduce transportation cost barriers. Second, young men were more likely to bring up medical mistrust than young women. Finally, inequitable gender norms were largely discussed in the context of young women’s lower agency and sexual relationship power (Table 1).

Table 1.

Material contexts associated with HIV and STI prevention and testing engagement with urban refugee adolescents and youth in Kampala, Uganda

| Material context | Sub‐theme | Illustrative quotation |

|---|---|---|

| Transportation and location | Close proximity helpful to access HIV/STI testing |

‘Some people get interested since they want to know their status, so if that service comes nearby in a community which you are living in, it becomes an advantage. It is for free’. (focus group [FG], young women, aged 20–24, ID#6) ‘There can be still some challenges so far, for example transport, to find transport is very difficult because most of them they don’t work and they are jobless. They don’t have money. So, the distance also can be a challenge and the means of reaching there’. (KI, young refugee agency) ‘Let them know if there will be transport, once you explain to them, maybe we shall need one day a campaign where you mobilise all youths’. (FG, young men, aged 20–24, ID #3) ‘Sometimes you find that someone stopped going for testing because the place is very far’. (FG, young women, aged 16–19, ID #8) ‘Up to now we still find sex workers that are shy, yet are in Kampala town; you can't tell them to go to a street in Kampala..most times if we mobilize them to come here we get them transportation’. (KI, sex work agency) |

| Need far distance from home for privacy | ‘We need privacy and it’s an assurance that no one will know whether you’re positive or negative, no one will see you going to hospital for test. After that you may go on for treatment but at least you are doing it alone because you may choose any hospital which is farther from your house’. (FG, young men, aged 20–24, ID #6) | |

| Private spaces | For self‐testing implementation and disposal | ‘Have (testing) at these centres, tents in schools, and in the community because it allows some people to go and do their test not in the centres that are near them, but attend centres that are farther because they don’t trust health workers there, and they need privacy’. (FG, young men, aged 20–24, ID #8) |

| To access self‐testing kits |

‘It’s better to have them [HIV self‐test kits] in all centres like clinics, pharmacies, its more accessible’ (FG, young men, aged 20–24, ID #7) ‘We can put them [HIV self‐testing kits] in churches and universities’ (FG, young women, aged 16–19, ID #2) |

|

| Literacy | Literacy and a lack of access to formal education is a barrier |

‘There are people who know how to read and those who don’t know how to read, so I think during the period of distribution, you first teach them so that they can also use without reading those instructions. I think you can first explain to them, and even if they don’t read the instructions they can still use that test kit’. (FG, young women, aged 20–24, ID #3) ‘We as community members have to create a lot of awareness first, because there are people who have never been to school and they know nothing about this self‐test’. (FG, young women, aged 16–19, ID #2) |

| Illustrations may not be sufficient so there is a need for alternative ways of educating |

‘I think we can use the community radio and make an announcement that these young people can come and test for free, so most of the time if you have tested recently or know your status they don’t tend to go there but those ones who have never tested or those ones who tested a long time ago are the ones who come. So when you call out like that, the people who come are the exact people that you want’. (FG, young women, aged 16–19, ID #9) ‘When it comes to sex workers, you still have to physically show them how these instructions are practically done. Even beyond the pictures. At some point, stand there and show them exactly the whole process as they are looking. Because some of the sex workers are not educated’. KI, sex work agency) ‘It is not a matter of just reading the instructions, it is better if someone comes to buy it and you explain to them how it is used and how long it takes to wait for the results, that it is twenty minutes. Because you might just give it out and on reaching at home they wonder where to insert it, whether in the armpit, so it is good you first teach them how to use it’. (FG, young women, aged 20–24, ID #2) |

|

| Language | For HIV self‐testing instructions |

‘You can add as many languages as you can, because here we have refugees from different locations’. (FG, young women, aged 16–19, ID #3) ‘If (HIV/STI) leaflets are distributed, they should also be translated into French and Swahili’. (KI, humanitarian agency) ‘You should also have persons that speak different languages, say Lingala, French, since these refugees may not feel comfortable speaking Luganda or English. When they realize that you have someone who speaks their language, they open up’. (KI, HIV service provider) ‘There are those who are educated but don't know English, yet most of these instructions are in English. Now if I take it to an old person and I tell them it is here, and I go away, they cannot know what is there because the instructions are in English. For example, if the instructions say open the box, they should also put it in Swahili, French’. (FG, young women, aged 20–24, ID #1) |

| For HIV services and healthcare |

‘Most times we can't go for an outreach without a counsellor who we attach to an interpreter, because sometimes they trust that person who speaks their language who explains very well in their own language’. (KI, sex work agency) ‘At a facility, refugees mainly have a language barrier because most of them speak French and Lingala like the Congolese, the Burundians French and Kirundi, then Rwandese French and Kinyarwanda… majority like eighty percent are affected by language barrier. We tried to help them access health services by placing volunteers… to support their fellow refugees access health services because they understand the local languages for refugees and also English so that they can interpret for refugees when they go to health centers during sessions with doctors and nurses’. (KI, humanitarian agency) |

Discussion

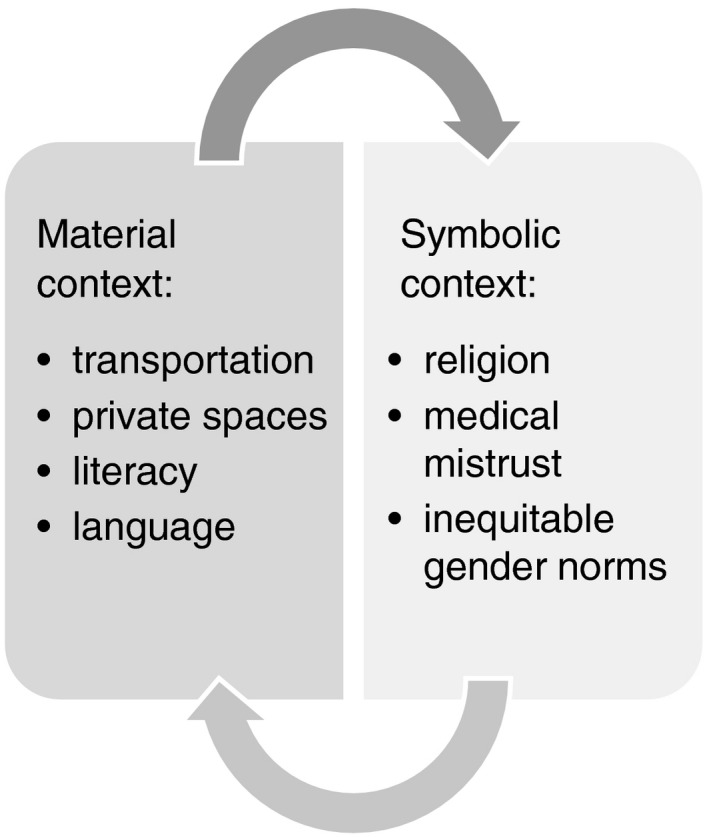

Urban refugee/displaced youth narratives revealed socio‐environmental factors that shaped engagement in HIV prevention and testing. Material barriers included transportation costs, overcrowded living conditions, low literacy and language barriers. Symbolic contexts included the salient role of religion, mistrust of outreach workers and inequitable gender norms. These findings produce a conceptualisation of material and symbolic contexts relevant to developing health‐enabling environments [7, 25] among urban refugee/displaced youth (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Material and symbolic contextual factors associated with HIV and STI testing and prevention engagement among urban refugee and displaced adolescents and youth in Kampala, Uganda.

Our study corroborates research on the importance of providing technical information, resources and skills alongside addressing the social circumstances that constrain people’s agency over addressing their sexual health [7, 25]. First, our study reflected the need for technical information to be provided in creative ways for refugees with low literacy, including pictures, radio and demonstrating in‐person how to use HIV self‐testing kits. In other global regions, people with low literacy levels were willing to access HIV testing [26], yet also struggled with technologies such as HIV self‐testing [27], signalling the need to prepare low literacy service delivery [26]. Second, transportation costs were a barrier to travelling to clinics for SRH services, yet some participants wanted SRH services away from their community to maintain confidentiality. That produces the challenge of providing transportation and/or testing via community‐based mobile clinics and pharmacies. These findings corroborate studies with adults in Nakivale refugee settlement who also noted transportation costs as barriers to both HIV testing [17] and antiretroviral adherence [28]. Overcrowded living spaces produced privacy challenges for HIV self‐testing and disposal of test kits, reinforcing the challenges that youth have realising optimal SRH outcomes in slums in Uganda [29] and other contexts [30]. Alternative means of HIV self‐test kit disposal can be explored, such as lay health worker pick‐up [27]. Language barriers are a well‐established barrier to realising SRH among young refugees [31]. As Kampala hosts refugees from many neighbouring countries, multi‐lingual health services are critical (Table 2).

Table 2.

Symbolic contexts associated with HIV and STI prevention and testing engagement with urban refugee adolescents and youth in Kampala, Uganda

| Theme | Sub‐theme | Illustrative quotation |

|---|---|---|

| Religion & religious institution involvement | Potential for HIV and STI testing and prevention outreach |

‘It will also be good to involve churches because there you find people of different ages’. (FG, young women, aged 16–19, ID #6) ‘Also [outreaches] at churches and NGOs that work with refugees, radio talk shows’. (FG, young women, aged 16–19, ID #2) ‘I think the best way is how we have been doing outreaches, most cases are the churches, from there you can get them because there are many churches for refugees, for Congolese, Banyarwanda’. (FG, young women, aged 20–24, ID #3) ‘Everyone here has a church they go to; in the area where we stay there are different churches for refugees, if you approach most of them it becomes easy…you give information to me and I go to my church and everyone goes to their church, that is how you will get people’. (FG, young women, aged 20–24, ID #9) |

| Conflicting beliefs | ‘It might be tricky, it might work out. The tricky part might be when you look at the scenarios like when you go to do HIV testing in churches… So they need sensitization, we need to organize like workshops for religious leaders specifically and local leaders so that they can understand and you can take the program to them’. (KI, humanitarian agency) | |

| Medical mistrust | Mistrust of people coming in the community to offer HIV testing | ‘It’s something he heard in the community but never experienced it. That these people who come in the tents, sometimes they inject you with HIV also. So, people cannot trust them because they fear maybe they are also giving the same sickness since we don’t trust the needles they’re using and stuff like that’. (FG, young men, aged 20–24, ID #7) |

| Mistrust of the HIV self‐test kit |

‘You know they are used to blood tests and know that HIV is in the blood, not just in the mouth. They will think that it’s just a lie’. (FG, young men, aged 20–24, ID #3) ‘If I want to go and test myself but then I take milk, can it still show that I have HIV in case I have it? Because some people say that if you go with maybe a boyfriend for an HIV test and you take milk or Coca Cola that they affect the results and cannot show that you are HIV positive’. (FG, refugee sex workers, ID #6) |

|

| Inequitable gender norms | Do you think if a woman fears the husband like that, what about the child who is seventeen years…. So for them from eighteen and even seventeen they can be married off. Because of cultural beliefs and egos among these refugee men, mainly it was brought about by their cultures for women to respect their husbands and fear them. (KI, humanitarian agency) |

In addition to addressing these logistic issues, participant narratives amplified the importance of addressing symbolic contexts. Religion maintained a connection to home communities and cultures; hence, participants noted that churches could be harnessed as a platform to share HIV information once religious leaders were trained. Prior work in Kenya documented that facilitated engagement of religious leaders contributed to supportive views of sexual health [32]. Medical mistrust emerged; in other contexts, medical mistrust among refugees has been linked with past and current experiences of being mistrusted, social contexts of discrimination and not knowing people sufficiently [33, 34]. Peer‐led services could circumvent this mistrust. Our findings that gender‐based stigma and discrimination presented barriers to realising SRH corroborates prior research [35]. SGBV in war targeting girls/women not only increases HIV exposure, but exacerbates trauma and existing gender inequities [36]. Police violence and criminalisation targeting sex workers in other contexts was associated with constrained access to condom use and increased HIV vulnerabilities [37, 38]. A large body of research describes gender‐based stigma and discrimination, and its intersection with other stigmatised health concerns such as HIV, and social identities such as sex work, as profound barriers to HIV testing and prevention [27], including with young refugees in Kampala [3].

Our study has limitations, including recruiting participants from community partners. We may have overrepresented youth more knowledgeable about, and connected to, HIV resources. The focus group design may have presented a barrier for some participants sharing personal experiences. Future research could conduct in‐depth interviews with refugee youth to further explore contexts linked with their knowledge and engagement with HIV prevention. Despite these limitations, our study offers a unique contribution by identifying contextual factors pertinent to HIV testing among urban refugee youth – HIV testing preferences among young refugees are understudied [2, 5, 8], and this is particularly true in urban settings where refugees are underrepresented in research [39] and often lack access to humanitarian support systems [40]. Our findings also signal the need for integration of gender‐based differences and priorities in implementation of HIV testing initiatives with urban refugee youth [41].

Together these findings point to the need to move beyond information and skills provision to transforming informal settlements where urban refugee/displaced youth live into health‐enabling social environments [7]. Findings reveal the need for interventions to nurture a landscape where refugee/displaced youth can easily navigate transportation, literacy and language issues, access outreach programmes and manage privacy concerns to access SRH services. Relationships can be developed between HIV prevention programmes and religious leaders to offer contextually relevant services. Gender transformative approaches can address the traumatic, long‐lasting impacts of SGBV in war to disrupt inequitable gender norms [36]. Nurturing trusting relationships between service providers and refugee communities, and dismantling gender discrimination and other forms of stigma [42], are essential components of creating a social context conducive to HIV prevention and testing. Findings can inform multilevel approaches to alter material and symbolic contexts in ways that increase agency among urban refugee/displaced youth over their sexual health and well‐being.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all of the peer navigators and participants, as well as collaborating agencies: Ugandan Ministry of Health, Office of the Prime Minister, Young African Refugees for Integral Development (YARID), Most At Risk Populations Initiative (MARPI) and InterAid Uganda. Funding: Canadian Institutes of Health Research Project Grant. CHL also supported by the Canada Research Chairs Program, Canada Foundation for Innovation and Ontario Ministry of Research & Innovation.

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Good health and well‐being, gender equality; universal health coverage

Contributor Information

Carmen H. Logie, Email: carmen.logie@utoronto.ca.

the Migrant Health Dermatology Working Group:

Grace Bandow, Aileen Chang, Ser‐Ling Chua, Ncoza Dlova, Wendemagegn Enbiale, Amy Forrestel, Claire Fuller, Christopher Griffiths, Rod Hay, Jenny Hughes, Sidra Khan, Alexia Knapp, Eleni Linos, Carmen Logie, Su Lwin, Ismael Maatouk, Toby Maurer, Aldo Morrone, Kayria Muttardi, Bayanne Olabi, Valeska Padovese, Aisha Sethi, Kari Wanat, and Tori Williams

References

- 1. UNHCR . UNHCR ‐ Global Trends 2019: Forced Displacement in 2019 [Internet]. 2020 Oct. (Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/globaltrends2019/). Accessed January 1, 2021.

- 2. Singh NS, Smith J, Aryasinghe S, Khosla R, Say L, Blanchet K. Evaluating the effectiveness of sexual and reproductive health services during humanitarian crises: a systematic review. PLoS One 2018:13: e0199300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Logie CH, Okumu M, Mwima S et al. Sexually transmitted infection testing awareness, uptake and diagnosis among urban refugee and displaced youth living in informal settlements in Kampala, Uganda: a cross‐sectional study. BMJ Sex Reprod Heal 2020: 46:192–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Logie CH, Okumu M, Mwima SP et al. Exploring associations between adolescent sexual and reproductive health stigma and HIV testing awareness and uptake among urban refugee and displaced youth in Kampala Uganda. Sex Reprod Heal Matters 2019: 27: 86–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jennings L, George AS, Jacobs T, Blanchet K, Singh NSA. A forgotten group during humanitarian crises: a systematic review of sexual and reproductive health interventions for young people including adolescents in humanitarian settings. Confl Health 2019: 13: 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hargreaves JR, Delany‐Moretlwe S, Hallett TB et al. The HIV prevention cascade: integrating theories of epidemiological, behavioural, and social science into programme design and monitoring. Lancet HIV 2016: 3: e318–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Campbell C, Cornish F. How can community health programmes build enabling environments for transformative communication? Experiences from India and South Africa. AIDS Behav 2012: 16: 847–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Singh NS, Aryasinghe S, Smith J, Khosla R, Say L, Blanchet K. A long way to go: a systematic review to assess the utilisation of sexual and reproductive health services during humanitarian crises. BMJ Glob Heal 2018: 3: e000682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kamal B. Now 1 in 2 World’s Refugees Live in Urban Areas | Inter Press Service. Inter Press Serv. 2016: 10–1. (Available from: http://www.ipsnews.net/2016/05/now‐1‐in‐2‐worlds‐refugees‐live‐in‐urban‐area/). [Google Scholar]

- 10. Park H. The power of cities [Internet]. UNHCR; 2016 (Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/innovation/the‐power‐of‐cities/). Accessed January 1, 2021.

- 11. Rees M. Foreword: Time for cities to take centre stage on forced migration. Forced Migr Rev 2020: 3: 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sabila S, Silver I. Cities as partners: the case of Kampala. Forced Migr Rev 2020: 3: 41–43. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Country: Uganda [Internet]. UNHCR. 2020. (Available from: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/country/uga).

- 14. Uganda [Internet]. UNAIDS. 2018. (Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/uganda).

- 15. Press Release on HIV Situation in Uganda [Internet]. UN in Uganda. 2017. (Available from: http://ug.one.un.org/press‐releases/press‐release‐hiv‐situation‐uganda‐february‐23‐2017#).

- 16. Ivanova Olena, Rai Masna, Mlahagwa Wendo, Tumuhairwe Jackline, Bakuli Abhishek, Nyakato Viola N., Kemigisha Elizabeth. A cross‐sectional mixed‐methods study of sexual and reproductive health knowledge, experiences and access to services among refugee adolescent girls in the Nakivale refugee settlement, Uganda. Reproductive Health. 2019: 16: 1: 10.1186/s12978-019-0698-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. O’Laughlin KN, Rouhani SA, Faustin ZM, Ware NC. Testing experiences of HIV positive refugees in Nakivale Refugee Settlement in Uganda: informing interventions to encourage priority shifting. Confl Health 2013: 7: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Patel S, Schechter MT, Sewankambo NK, Atim S, Kiwanuka N, Spittal PM. Lost in transition: HIV prevalence and correlates of infection among young people living in post‐emergency phase transit camps in Gulu District. Northern Uganda. PLoS One 2014: 9: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stark L, Asghar K, Yu G, Bora C, Baysa AA, Falb KL. Prevalence and associated risk factors of violence against conflict‐affected female adolescents: a multi‐country, cross‐sectional study. J Glob Health 2017: 7: 10416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vu A, Adam A, Wirtz A et al. The prevalence of sexual violence among female refugees in complex humanitarian emergencies: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. PLoS Curr. 2014. 10.1371/currents.dis.835f10778fd80ae031aac12d3b533ca7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Logie CH, Okumu M, Mwima S et al. Social ecological factors associated with experiencing violence among urban refugee and displaced adolescent girls and young women in informal settlements in Kampala, Uganda: a cross‐sectional study. Confl Health 2019: 13: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Garnett GP, Hallett TB, Takaruza A et al. Providing a conceptual framework for HIV prevention cascades and assessing feasibility of empirical measurement with data from east Zimbabwe: a case study. Lancet HIV 2016: 3: e297–e306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006: 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Attride‐Stirling J. Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research. Qual Res 2001: 1: 385–405. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gibbs A, Jewkes R, Sikweyiya Y. “I Tried to resist and avoid bad friends”: the role of social contexts in shaping the transformation of masculinities in a gender transformative and livelihood strengthening intervention in South Africa. Men Masc 2018: 21: 501–520. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Khatoon S, Budhathoki SS, Bam K et al. Socio‐demographic characteristics and the utilization of HIV testing and counselling services among the key populations at the Bhutanese Refugees Camps in Eastern Nepal. BMC Res Notes 2018: 11: 535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bwalya C, Simwinga M, Hensen B et al. Social response to the delivery of HIV self‐testing in households: experiences from four Zambian HPTN 071 (PopART) urban communities. AIDS Res Ther 2020: 17: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. O’Laughlin KN, Rouhani SA, Kasozi J et al. A qualitative approach to understand antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence for refugees living in Nakivale Refugee Settlement in Uganda. Confl Health. 2018: 12: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Renzaho AMN, Kamara JK, Georgeou N, Kamanga G. Sexual, reproductive health needs, and rights of young people in Slum Areas of Kampala, Uganda: a cross sectional study. PLoS One 2017: 12: 1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wado YD, Bangha M, Kabiru CW, Feyissa GT. Nature of, and responses to key sexual and reproductive health challenges for adolescents in urban slums in sub‐Saharan Africa: a scoping review. Reprod Health 2020: 17: 149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tirado V, Chu J, Hanson C, Ekström AM, Kågesten A. Barriers and facilitators for the sexual and reproductive health and rights of young people in refugee contexts globally: a scoping review. PLoS One 2020: 15: 1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gichuru E, Kombo B, Mumba N, Sariola S, Sanders EJ, van der Elst EM. Engaging religious leaders to support HIV prevention and care for gays, bisexual men, and other men who have sex with men in coastal Kenya. Crit Public Health 2018: 28: 294–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Renzaho A, Polonsky M, McQuilten Z, Waters N. Demographic and socio‐cultural correlates of medical mistrust in two Australian States: Victoria and South Australia. Heal Place 2013: 24: 216–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Níraghallaigh M. The causes of mistrust amongst asylum seekers and refugees: Insights from research with unaccompanied asylum‐seeking minors living in the republic of Ireland. J Refug Stud 2014: 27: 82–100. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Logie CH, James L, Tharao W, Loutfy MR. HIV, gender, race, sexual orientation, and sex work: a qualitative study of intersectional stigma experienced by HIV‐positive women in Ontario, Canada. PLoS Med 2011: 8: e1001124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jones N, Cooper J, Presler‐Marshall E, Walker D. The fallout of rape as a weapon of war: the life‐long and intergenerational impacts of sexual violence in conflict. Odi [Internet]. 2014;(June):1–7 (Available from:http://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi‐assets/publications‐opinion‐files/8990.pdf). Accessed January 1, 2021.

- 37. Logie CH, Wang Y, Marcus N, Lalor P, Williams D, Levermore K. Pathways from police, intimate partner, and client violence to condom use outcomes among sex workers in Jamaica. Int J Behav Med 2020: 27: 378–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Logie CH, Wang Y, Lalor P, Williams D, Levermore K, Sherman SG. Exploring associations between place of sex work and HIV vulnerabilities among sex workers in Jamaica. Int J STD AIDS 2020: 31: 1186–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Anzellini V, Leduc C. Urban internal displacement: data and evidence. Forced Migr Rev 2020: 3: 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hirsch‐holland A. Applying camp management methods to urban displacement in Afghanistan. Forced Migr Rev 2020: 3: 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tannenbaum C, Greaves L, Graham ID. Why sex and gender matter in implementation research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2016: 16: 145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stangl AL, Earnshaw VA, Logie CH et al. The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework: a global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health‐related stigmas. BMC Med. 2019: 17: 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]