Abstract

Accessing aldehydes from carboxylate moieties is often a challenging task. In this regard, carboxylate reductases (CARs) are promising catalysts provided by nature that are able to accomplish this task in just one step, avoiding over‐reduction to the alcohol product. However, the heterologous expression of CARs can be quite difficult due to the excessive formation of insoluble protein, thus hindering further characterization and application of the enzyme. Here, the heterologous production of the carboxylate reductase from Nocardia otitidiscaviarum (NoCAR) was optimized by a combination of i) optimized cultivation conditions, ii) post‐translational modification with a phosphopantetheinyl transferase and iii) selection of an appropriate expression strain. Especially, the selection of Escherichia coli tuner cells as host had a strong effect on the final 110‐fold increase in the specific activity of NoCAR. This highly active NoCAR was used to reduce sodium benzoate to benzaldehyde, and it was successfully assembled with an in vitro regeneration of ATP and NADPH, being capable of reducing about 30 mM sodium benzoate with high selectivity in only 2 h of reaction.

Keywords: aldehydes, carboxylate reductase, in vitro cofactor regeneration, inclusion bodies, soluble protein

Biocatalytic reduction of carboxylates: Optimization of cultivation parameters and host strain selection were fundamental to decreasing the formation of inclusion bodies and enhancing the production of NoCAR, which was able to reduce up to 65 mM sodium benzoate to benzaldehyde in 24 h with integrated in vitro recycling of NADPH and ATP.

Introduction

Chemicals with aldehyde moieties are useful substrates for the synthesis of pharmaceuticals and high‐value compounds, such as metaraminol ((1R,2S)‐3‐(2‐amino‐1‐hydroxy‐propyl)phenol) and substituted tetrahydroisoquinolines, which are compounds with a wide range of bioactivities, including cardiovascular and antitumor, antiparasitic, and anticholinergic properties, respectively.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ] Classical chemical approaches to obtain aldehydes from carboxylic acids are often expensive, rich in reaction steps, environmentally harmful, and/or predominantly not sustainable.[ 8 , 9 , 10 ] Alternatively, more sustainable approaches to access aldehydes involve the reduction of carboxylic acids obtained by microbial transformations from second generation feedstock. [11] The exploitation of alternative synthetic routes based on organic acids, for example, gained from renewables, plays an important role in biocatalysis.[ 12 , 13 ]

In this context, carboxylate reductases (CARs, E.C.1.2.1.30) are a group of single enzymes capable of carrying out the mentioned reduction reaction in only one step. CARs activate the carboxylate substrate with the aid of ATP and catalyze the reduction step using NADPH as hydride donor. They could satisfy the demand for a green and chemoselective path from carboxylic acids to their respective aldehydes. [14]

Mechanistically, CARs are multi‐domain enzymes that require an auxiliary phosphopantetheinyl transferase (PPTase) to achieve full enzymatic activity.[ 14 , 15 ] CARs expressed in Escherichia coli are apoenzymes. These are converted into holoenzymes by post‐translational modification either in vivo through co‐expression of a PPTase or in vitro by incubation with a PPTase in the presence of CoA. [15]

Another remarkable feature of CAR enzymes is their broad substrate tolerance, ranging from aliphatic acids to aromatic, polycyclic and heterocyclic acids, besides a wide variety of additionally allowed substituents.[ 16 , 17 ] Hence, CARs have been applied in various synthetic routes and, in several cases, combined prosperously with other enzymes and chemical steps through cascade reactions to synthesize high‐value compounds.[ 12 , 18 , 19 ] CARs are potentially the missing link between (substituted) aromatic carboxylic acids produced by microbial cell factories from renewables [11] and aldehyde motifs, which are building blocks of many active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). Conclusively, CARs could be the key to a promising hybrid process that combines microbial transformations and both enzymatic and chemoenzymatic cascades towards the implementation of a bioeconomy that is both sustainable and competitive concerning ecologic and economic demands.

One of the primary challenges that can hinder the successful application of CARs is their typically rather low recombinant expression levels together with a severe aggregation in inclusion bodies (IBs). This aggregation is accelerated by the low tolerance of E. coli for large (>100 kDa) heterologous proteins. [20] As bacterial CARs are of typically 130 kDa in size, their aggregation in IBs is not unexpected,[ 21 , 22 ] especially as post‐translational modifications are additionally needed, as described above. Proteins in IBs are often completely devoid of biological activity or show severely reduced activity. [23] Therefore, strategies to overcome such problems are crucial for the production of active CAR enzymes.

As such, the best strategy is often to reduce the formation of insoluble protein and to maximize soluble and active protein production. The production of soluble and active proteins is influenced by several factors including expression host, fusion tags, induction temperature and point in time, and culture conditions (the type of media, type of induction, additives, aeration, etc.).[ 20 , 24 ] Even though several methods to improve soluble protein expression have been suggested, none offers a universal protocol. [24]

To employ CAR enzymes in large‐scale applications, continuous regeneration of the cofactors ATP and NADPH is required. In vivo approaches using resting whole cells or fermentation processes are quite cheap and offer a simple strategy to recycle both cofactors, but they have several limitations.[ 12 , 25 ] Especially when high product concentrations are targeted, these high aldehyde concentrations can toxify the cells when no other measures are taken to protect them.[ 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ] Alternatively, in vitro recycling of ATP and NADPH can overcome some of these limitations and prevent undesired reactions, but on the drawback of reducing economic efficiency due to addition of several co‐enzymes and co‐substrates.[ 12 , 25 , 30 ]

Herein, we focused on the expression and production of the carboxylate reductase from Nocardia otitidiscaviarum (NoCAR), a bacterial type CAR from the subclass Actinobacteridae. [31] Up‐to‐date, only few studies have reported the use of this enzyme in biotransformations of carboxylic acids.[ 13 , 14 , 16 ] Therefore, further characterization of this enzyme is still necessary to better understand its catalytic performance and expand the existing toolbox of carboxylate reductases.

As an excessive formation of IBs complicated the production of NoCAR, optimizing the expression conditions to maximize the total soluble protein yield was fundamental. A central composite design of experiments (CCD) using the response surface methodology (RSM) technique was applied. The experimental data was modeled with a second‐order polynomial function, which was then used to determine the optimal process conditions for the production of recombinant NoCAR. Next, to improve the activity of NoCAR, two strategies of post‐translational modification with the PPTase from E. coli (EcPPTase) were performed and evaluated in terms of their efficiency. The selection of an appropriate host strain enabled the production of a highly active NoCAR. Finally, the storage stability of NoCAR was evaluated for long‐term use of this biocatalyst.

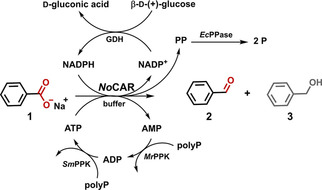

The last step was the efficient application of the improved NoCAR for the reduction of sodium benzoate (1) to benzaldehyde (2) with an in vitro recycling of ATP and NADPH. The full recycling of both cofactors was achieved by using the following auxiliary enzymes (Scheme 1): [25] the simultaneous action of polyphosphate kinases from Meiothermus ruber (MrPPK) and Sinorhizobium meliloti (SmPPK)[ 25 , 32 , 33 ] for the regeneration of ATP and a glucose dehydrogenase from Pseudomonas sp. (GDH) for the regeneration of NADPH. Finally, the inhibitory effects of pyrophosphate (PP),[ 14 , 34 ] which is generated in situ during the catalytic cycle of CARs, is surpassed by using the pyrophosphatase from E. coli (EcPPase).[ 25 , 35 ]

Scheme 1.

Reaction scheme for the in vitro reduction of sodium benzoate (1) to benzaldehyde (2) with full recycling of all cofactors. Benzyl alcohol (3) is a by‐product of undesired over‐reduction. polyp: polyphosphate, PP: pyrophosphate, P: ortho‐phosphate. (Adapted from Strohmeier et al. [25] ).

Results and Discussion

Expression and medium optimization

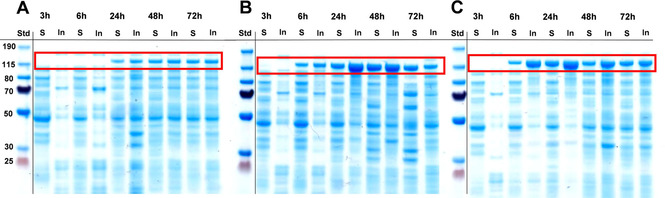

The recombinant production of soluble protein is still one of the major challenges in biology. [24] E. coli is the most widely used expression host for the production of recombinant protein but its low tolerability to relatively large proteins may facilitate their aggregation in an insoluble form. As such, the production of soluble NoCAR appeared to be a challenging task. The first experiments in this direction started with a medium optimization using E. coli BL21(DE3) as host strain, as shown in Figure 1. Three different media and induction conditions (namely auto‐induction (AI) medium, lysogeny broth (LB) medium, and terrific broth (TB) medium) were evaluated for the expression of NoCAR at different time points for up to 72 h. From these experiments, TB medium in combination with induction by 0.1 mM isopropyl β‐d‐1‐thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at OD600 of 0.9–1.0 and 48 h of cultivation showed to be suitable conditions to yield good overall expression of the recombinant NoCAR (Figure 1C). Besides, the amount of soluble protein achieved under these conditions was considerably high, although IBs were present in high amounts. (Table S3 and Section S3.1. in the Supporting Information). Although a full optimization of the heterologous production of the carboxylate reductase from Mycobacterium marinum (MmCAR) using TB medium in combination with autoinduction was recently reported [29] IPTG induction in TB medium was herein selected for further optimization studies. AI medium could also be a good choice but it initiates a very strong expression from the T7 promoter. This may not be optimal if the protein has moderate or low solubility. Thus, IPTG is preferred as expression from the T7 promoter as it can be more sensitively regulated and may provide a better yield of soluble protein. However, the total amount of soluble NoCAR was still low and most of the target protein accumulated in the insoluble fraction.

Figure 1.

Expression of NoCAR in three different media: A) lysogeny broth (LB), B) auto‐induction medium (AI), and C) Terrific Broth (TB); IPTG (0.1 mM final concentration) was added to A and C after 3 hours of cultivation (OD600 of 0.9–1.0). The time points in which samples were collected (after 3, 6, 24, 48, and 72 h of cultivation) are given on top of each SDS gel scan. For each sample, soluble (S) and insoluble (In) protein fractions were analyzed/visualized. The red box highlights the band corresponding to NoCAR (∼130 kDa; n biological=1).

Introducing E. coli Tuner as host strain for the production of NoCAR and optimization of cultivation parameters

The second approach to improve the production of NoCAR was to switch the host strain from E. coli BL21(DE3) to E. coli Tuner(DE3). Latter is a lacZY deletion mutant of the BL21 strain, which enables the adjustable expression of protein. The lacY (lac permease) mutation allows for the uniform entry of IPTG into all cells of a culture. [36] This results in a concentration‐dependent, homogeneous level of induction. Therefore, adjusting the concentration of IPTG allows for a more sensitively regulated gene expression and was expected to reduce IB formation.[ 36 , 37 ]

Besides cell selection, cultivation parameters were optimized in the same setting. As already mentioned, adjusting inducer concentrations might help to enhance solubility for delicate and large proteins. As it is not reasonable to evaluate every single factor that can have influence on the production of soluble protein, the most important ones were selected. Besides IPTG concentration, two additional factors to increase the production of soluble NoCAR were the optical density (OD600) at the induction and the cultivation temperature after induction, those three factors are relatively easy to control and manipulate.

Instead of using a trial and error approach, such as by optimizing one variable at a time, a factorial approach based on a central composite design (CCD) was applied. In general, factorial approaches, such as response surface methodology (RSM) are reported to capture the interactions between the different factors more accurately, rapidly and, optimally, in a reduction of the total number of experiments[ 24 , 38 ] (Section S3.2.).

One of the first observations was that the decrease of the temperature of cultivation from 20 °C down to 15 °C provided a slower gene expression (and, consequently, less biomass was formed) but better folding of the protein in a soluble form. Formation of IBs was diminished for the cultivations performed under lower temperature conditions.

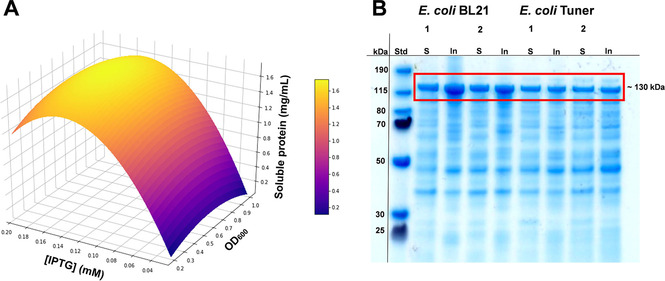

Figure 2A shows how the amount of soluble NoCAR [mg mL−1] expressed in E. coli Tuner at 15 °C varies by changing the concentration of inducer and the OD600 at the induction time.

Figure 2.

A) Visualization of the response surface curve generated from a quadratic model for the optimization of three variables with the temperature fixed at 15 °C. The curve shows how the total amount of soluble NoCAR [mg/mL] expressed in E. coli Tuner varies by changing the concentration of the inducer IPTG and the OD600 at the induction time (n=1). B) Expression analysis of NoCAR (ca. 130 kDa) expressed in E.coli BL21 and E.coli Tuner in TB medium for 48 h. Soluble (S) and insoluble (In) protein fractions of NoCAR were produced under the conditions: Lane 1: 0.1 mM IPTG and 20 °C; lane 2: 0.18 mM IPTG and 15 °C. SDS‐PAGE® using Novex® 4–12 % Bis⋅Tris gels (200 V, 0.10 mA, 60 min in MOPS buffer), staining: Simply Blue™ solution, ladder: PageRuler™ Prestained Protein Ladder (15–190 kDa; n biological=1).

Overall, the amount of soluble NoCAR ranged from 0.2 to approximately 1.6 mg mL−1 when the IPTG concentration increased from 0.04 to 0.18 mM, respectively. There, a rapid decrease of the soluble protein produced with higher concentrations of IPTG was observed. Interestingly, OD600 had no major influence on the total amount of soluble NoCAR. Lower temperatures of cultivation and slightly higher inducer concentrations were the factors that mostly influenced the production of soluble protein. As a result, the best cultivation conditions to obtain mostly soluble NoCAR cultivated in TB medium were 0.9–1.0 OD600 at induction, 0.18 mM IPTG concentration, and a cultivation temperature of 15 °C.

Figure 2B shows the production of NoCAR under the optimized cultivation conditions (0.18 mM IPTG, 15 °C) and the previous conditions (0.1 mM IPTG, 20 °C) in both, E. coli BL21 and E. coli Tuner. As can be observed, the bands for the insoluble protein fractions are generally larger for the cultivations in E. coli BL21 than in E. coli Tuner, in both cultivation conditions evaluated. Therefore, the major difference is related to the selection of the production host.

It is important to note that the overall production of NoCAR in E. coli Tuner was not better compared to the expression in E.coli BL21. As already mentioned, E. coli Tuner allows for a more regulated gene expression compared to the BL21 strain, [36] which might result in less biomass produced within the same period. Still, the motivation was to increase the amount of soluble protein. At this stage, full elimination of IBs was not possible, but E. coli Tuner has proved to be a much more suitable host for the production of soluble protein. So far, only the efficient production of soluble NoCAR was targeted. Enzyme activity was addressed in the next step.

Post‐translational modification of NoCAR with EcPPTase

PPTases catalyze post‐translational modifications of proteins by covalently attaching the 4’‐phosphopantetheine (4’‐Ppant) moiety of CoA usually to a conserved serine residue of an apoenzyme. [15] A 4’‐Ppant prosthetic group in active CAR serves as a “swinging arm” that reacts with acyl‐AMP intermediates at the N‐terminal adenylating domain to form a covalently linked thioester that “swings” to the C‐terminal reductase domain for reduction by NADPH, subsequent aldehyde release, thiol regeneration, and a new catalytic cycle.[ 12 , 15 ] Thus, post‐translational modification on CARs is essential to install their activity. Recently, non‐exhaustive phosphopantetheinylation during cultivation was found to be a limiting factor. [29]

To determine whether also NoCAR was an inhomogeneous mixture of apo‐ and holo‐CAR, NoCAR expressed in E. coli Tuner was purified and incubated with purified EcPPTase and acetyl‐CoA (in vitro activation). Here, different parameters were evaluated during the incubation, such as the amount of EcPPTase and acetyl‐CoA used for the activation of NoCAR as well as the time of incubation. The best incubation conditions were found to be as follows: 0.143 mg mL−1 of EcPPTase, 2 mM acetyl‐CoA and 2 h of incubation (more details about the optimization of the incubation approach is available in Table S5 and Section S4). The second approach was the co‐expression of NoCAR and EcPPTase in the same pET system (in vivo activation). In vivo co‐expression is a well‐known strategy and has been used with a variety of proteins and for different purposes.[ 39 , 40 ] At this stage, NoCAR was produced in both E. coli BL21 and E. coli Tuner to verify if different host strains could affect the enzyme activity. The results obtained for the post‐translational modification of NoCAR with EcPPTase regarding both strategies are compiled in Table 1.

Table 1.

Specific activity of NoCAR in different incubation[a} and co‐expression conditions.

|

Conditions |

Specific activity [U mg−1][g] |

|---|---|

|

holo‐NoCAR (in vitro activation)[b] |

|

|

in E. coli Tuner |

0.15 |

|

+acetyl‐CoA[c] |

0.19 |

|

+EcPPTase[d] |

0.18 |

|

+acetyl‐CoA and EcPPTase[c,d] |

0.22 |

|

holo‐NoCAR (in vivo activation)[e,f] |

|

|

in E. coli BL21 |

6.14 |

|

in E. coli Tuner |

16.5 |

[a] Incubation conditions: 2 h, 28 °C, 600 rpm. [b] In vitro activation of purified apo‐NoCAR (expressed in E. coli Tuner). [c] Incubation with 2 mM acetyl‐CoA. [d] Incubation with 0.143 mg mL−1 EcPPTase (purified form, liquid stock). [e] In vivo activation of NoCAR (co‐expressed with EcPPTase) applying optimized cultivation conditions. [f] Specific activity of the purified holo‐NoCAR determined after the desalting purification step (desalting buffer composition: 10 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.0). [g] One enzyme unity (U) is defined as the amount of enzyme that consumes one μmol of NADPH per minute under used assay conditions. Ten‐milimolar sodium benzoate was used in the assay. Data shown are the average of three technical replicates (n biological=1).

As shown in Table 1, the incubation of NoCAR simultaneously with EcPPTase and acetyl‐CoA yielded a slightly more active enzyme compared to NoCAR before any activation. For instance, before incubating purified NoCAR with purified EcPPTase and acetyl‐CoA, its specific activity was 0.15 U mg−1. After applying the best incubation conditions, the specific activity of NoCAR had a 1.6‐fold increase (0.22 U mg−1), which was considered to be still low for further applications of this enzyme. Nevertheless, these results support evidence that post‐translational modification of CARs with PPTases is fundamental to improve the catalytic power of this group of enzymes.

Contrarily, the co‐expression of NoCAR with EcPPTase showed a greater improvement on the specific activity of NoCAR compared to the incubation approach. Holo‐NoCAR expressed in E.coli BL21, for example, had a specific activity of 6.14 U mg−1, which is almost twenty‐eight times higher compared to the activity achieved with the in vitro activation. However, the activity was even higher when the host strain was changed. As shown in Table 1, holo‐NoCAR expressed in E. coli Tuner was the most active form of this CAR, showing a specific activity of 16.5 U mg−1. This corresponds to a 2.7‐fold increase compared to the holo‐NoCAR produced in E. coli BL21 and a 110‐fold increase compared to the NoCAR without any post‐translational modification.

In vitro applications of NoCAR

The application of CARs is dependent on their demand for expensive cofactors. [41] Besides, it is known that all of the by‐products of the reaction (PP, AMP, and NADP+) appear to be inhibitors..[ 14 , 34 ] For this reason, an efficient process requires both a robust, soluble holo‐CAR and an integrated cofactor‐recycling system.

Herein, we exploited an established cell‐free regeneration system to recycle both, ATP and NADPH, and maximize the production of the targeted product benzaldehyde 2 (Scheme 1). [25]

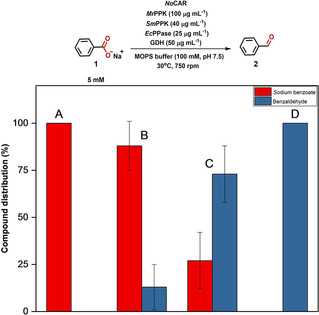

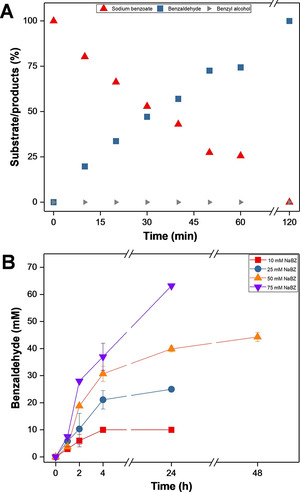

Purified NoCAR preparations were assembled with the regeneration of ATP and NADPH to access benzaldehyde 2 from sodium benzoate 1. As can be observed in Figure 3A, within 1 h of reaction, the in vitro activated NoCAR was unable to convert any of the substrate (5 mM) into benzaldehyde. Holo‐NoCAR produced in E. coli BL21 was able to convert less than 20 % of the substrate after the same period (Figure 3B). In contrast, holo‐NoCAR produced in E. coli Tuner converted about 80 % of the substrate under the same reaction conditions (Figure 3C), confirming the results from the photometric‐based activity assay (Table 1). Therefore, not only the in vivo activation of NoCAR was much more successful than the in vitro activation, but also changing the host strain had a significant impact on the enzyme performance.

Figure 3.

Comparing the ability of activated holo‐NoCAR to reduce sodium benzoate (5 mM) to benzaldehyde assembled with the in vitro cofactor recycling system during 1 h of reaction: A) holo‐NoCAR (after in vitro incubation with EcPPTase and acetyl‐CoA). In this case, no product was detected (below the detection limit of HPLC), B) holo‐NoCAR produced in E. coli BL21, and C) holo‐NoCAR produced in E. coli Tuner. In (A), (B), and (C), the concentration of holo‐NoCAR used was 18 μg mL−1. D) holo‐NoCAR produced in E. coli Tuner and assembled with the in vitro cofactor recycling system (100 μg mL−1 NoCAR, 2 h of reaction). Data points show the compound distribution in percentage after HPLC detection and are the average of three technical replicates±range (n biological=1).

The optimized reaction conditions (Section S5.3) for the in vitro reduction of 1 (Scheme 1) were applied using holo‐NoCAR with the highest enzyme activity (expressed in E. coli Tuner). As shown in Figure 4A, full conversion of 1 into 2 was obtained after 2 h of reaction, confirming the efficient application of holo‐NoCAR in the in vitro reaction system with recycling of both cofactors. In addition, it is important to highlight that no benzyl alcohol 3 (undesired product) was detected in the reaction mixture even after a longer period (up to 20 h of reaction, data not shown), demonstrating that NoCAR is indeed a very selective enzyme for the production of aldehydes.

Figure 4.

A) In vitro reduction of sodium benzoate 1 (5 mM) by using holo‐NoCAR (produced in E. coli Tuner) assembled with the in vitro recycling of cofactors. Data points show the compound distribution in percentage and are the average of three technical replicates (n biological=1). [42] Error bars were too small to indicate. B) Product amount [mM] for the reduction of different concentrations of sodium benzoate 1 (10–75 mM) to benzaldehyde 2 by holo‐NoCAR (100 μg mL−1) for up to 48 h of reaction with in vitro recycling of all cofactors. Data points show the compound distribution in percentage and are the average of three technical replicates (n biological=1). Error bars represent the standard deviation. As no over‐reduction was observed, no benzyl alcohol 3 was detected and is therefore not given. Reaction conditions: 100 mM MOPS buffer (pH 7.5), 6.25–100 mM MgCl2, 50–200 mM glucose, 4–25 mg mL−1 sodium polyphosphate, 100 μg mL−1 holo‐NoCAR, 100 μg mL−1 MrPPK, 40 μg mL−1 SmPPK, 25 μg mL−1 EcPPase, 50 μg mL−1 GDH, 30 °C, 800 rpm.

Figure 4B shows the accumulation of benzaldehyde obtained for in vitro biotransformations with varying concentrations of sodium benzoate. According to the data shown, holo‐NoCAR fully converted 10 mM sodium benzoate within 4 h. In the same time period, 21 mM of benzaldehyde (84 % conversion) were produced for the reactions starting with 25 mM sodium benzoate. For higher concentrations of sodium benzoate, high conversions into benzaldehyde were also observed. After 24 h of reaction, 40 mM benzaldehyde (80 % conversion) and 63 mM benzaldehyde (90 % conversion) were produced for the reactions starting with 50 and 75 mM sodium benzoate, respectively. However, running the reactions for longer periods (48 h) enhanced conversion of 40 mM benzaldehyde to 44 mM (88 % conversion), but did not yield full conversion. Still, these results show the potential of holo‐NoCAR in working with significant concentrations of the chosen model substrate with encouraging performance.

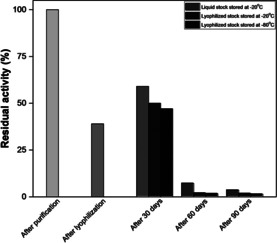

Storage stability of holo‐NoCAR

Storing enzymes for long‐term use and shipping is a conventional practice in several laboratories and industries. However, limited enzyme stability might be an obstacle depending on the chosen storage method. In general, selecting an appropriate storage method is crucial to preserve enzyme activity as much as possible.[ 43 , 44 ] Therefore, the enzyme activity of holo‐NoCAR was monitored over time to evaluate how stable this enzyme was under different storage conditions.

For the storage studies, purified holo‐NoCAR was stored under three different conditions: i) kept as liquid stocks and stored at −20 °C (10 mM Tris⋅HCl buffer, pH 7.0); kept in a lyophilized form and stored ii) at −20 °C or iii) at −80 °C (freeze‐drying conditions: 0.46 mbar, −46 °C, 72 h).

The specific activity of holo‐NoCAR after the desalting step of the purification was 16.5 U/mg, here set to 100 % (t=0). Subsequently, aliquots containing purified holo‐NoCAR in buffer was stored at −20 °C. The remaining holo‐NoCAR solution was freeze‐dried for 72 h. After this period, the specific activity of the lyophilized enzyme was determined (6.69 U/mg) and the enzyme was stored at −20 or −80 °C.

After the freeze‐drying process (day 3), holo‐NoCAR retained approximately 40 % of its original activity. One possible reason for this drop on the enzyme activity is because the freeze‐drying technique removes water from frozen samples by sublimation and desorption and this can affect the protein activity. A minimum of water to keep the enzyme molecule catalytically active is necessary and, by freeze‐drying it, the protein can lose activity.[ 45 , 46 ]

Additionally, the specific activity of holo‐NoCAR was monitored during 90 days of storage. Figure 5 shows the residual activity of the enzyme in this period of storage. As can be seen, after 30 days of storage, lyophilized holo‐NoCAR at −20 and −80 °C showed slightly higher enzyme activity (50 and 48 % residual activity, respectively) compared to the activity directly after free‐drying, at day 3 (before being stored as lyophilized stocks). The liquid stocks stored at −20 °C, however, had a considerable loss of activity after the same period of storage (59 % retained activity). Still, best activity could be achieved with this formulation.

Figure 5.

Storage stability of holo‐NoCAR over 90 days under different conditions. The residual activity was calculated in relation to the specific activity of holo‐NoCAR after purification (16.5 U mg−1, day 0). After lyophilization (day 3), the specific activity was determined before storing the enzyme (6.69 U mg−1). Data points show the relative specific activity in percentage and are the average of two or three technical replicates (n biological=1).

A huge drop on the activity was observed for all enzyme stocks after 60 days of storage. For instance, lyophilized holo‐NoCAR stored at −20 and −80 °C had both retained less than 5 % activity compared to the initial activity (t=0). Similarly, liquid stocks of holo‐NoCAR stored at −20 °C retained only 7 % activity. A month later, the activities were even lower (3–5 % retained activity) for all formulations. Although holo‐NoCAR proved to be a highly active enzyme, these results showed that this enzyme is rather unstable under the tested storage conditions. Conclusively, a more elaborate investigation including different storage buffers and additives would be needed prior to big batch productions. Fresh preparations seem to be the optimal formulation form. Future studies will focus on the evaluation of other storage methods, including the use of additives to stabilize the enzyme.

Conclusions

Carboxylate reductases (CARs) are powerful enzymes for the one‐step production of aldehydes directly from carboxylic acids. We showed that optimizing the production of recombinant NoCAR was crucial to lower the formation of inclusion bodies and, therefore, enhance production of active catalyst. Appropriate host strain selection was the most crucial factor for soluble and active CAR production. E. coli Tuner provided a slow but more regulated gene expression for soluble NoCAR production.

In addition, NoCAR had its activity improved by post‐translational modification with the PPTase from E. coli (EcPPTase). The co‐expression of both genes in E. coli Tuner under optimized cultivation conditions resulted in a highly active enzyme (holo‐NoCAR, 16.5 U mg−1), enabling further use of this enzyme in reactions targeting high conversions.

The biocatalytic reduction of sodium benzoate catalyzed by holo‐NoCAR to obtain benzaldehyde was successfully assembled with the in vitro regeneration of ATP and NADPH (>99 % conversion in 2 h of reaction). Storage stability studies showed that after a month of storage the activity of NoCAR decreased immensely, independently of the storage method used. Up to now, NoCAR had been used mostly for screening purposes and, therefore, its thorough catalytic power was still not fully known. Our results give the opportunity to expand the existing toolbox of carboxylate reductases, revealing NoCAR as a biocatalyst with high activity if freshly prepared in an active, soluble form. Currently, a screening of various substrates is under investigation, exploring the full potential of NoCAR.

Experimental Section

General: ATP and MgCl2 were obtained from Fluka Biochemika. NADPH was purchased from PanReac AppliChem (Darmstadt, Germany). Sodium polyphosphate was obtained from Merck (order no. 1.065.291.000; medium chain length n=25). Glucose dehydrogenase (GDH) from Pseudomonas sp. was purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich. HPLC‐MS grade acetonitrile was purchased from Biosolve Chimie (Dieuze, France). All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma‐Aldrich/Fluka or Carl Roth and used without further purification. CAR‐catalyzed reactions were performed on a Thermomixer comfort (Eppendorf) in 1.5 mL polypropylene tubes (Eppendorf).

Overexpression and protein purification: A literature known protein sequence with NCBI accession code WP 029928026.1 (NoCAR) [47] was ordered as synthetic gene in a pET151 vector with optimization of the genetic code for expression in E. coli (for sequence, see Section S2.1., Table S2). A literature known protein with a NCBI code CAQ31055.1 (EcPPTase) [48] was also ordered as a synthetic gene in a pET151 (for sequence, see Section S2, Figure S2). Both genes harbored a His tag on the N terminus. The NoCAR gene was co‐expressed in a pETDuet1 vector with the EcPPTase cloned into the first multiple cloning site and the N‐terminally His‐tagged CAR sequence in the second multiple cloning site (for the cloning protocol, see Section S2.1, Table S2). E. coli BL21(DE3) or E. coli Tuner(DE3) were transfected with the plasmid and colonies selected on LB/ampicillin agar plates. The final concentration of ampicillin used in the agar plates and in the shaking cultures was 100 mg/mL.

For the optimization of the production of NoCAR using E. coli Tuner(DE3), 2 mL of an overnight LB‐grown pre‐cultures were inoculated to 100 mL of TB medium at a final concentration of 2 % (v/v). The OD600 at induction, IPTG concentration, and temperature of cultivation after induction were evaluated. Five mL samples were collected at intervals (after 3, 6, 24, 48, and 72 h of cultivation). Samples were centrifuged (4000 rpm or 1800 g, 12 min, 4 °C), the supernatant was discarded and the pellet stored at −20 °C until further processing. After thawing, pellets were re‐suspended in 250 μL lysis buffer (50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0, containing 1 mg/mL lysozyme and 1 μL benzonase nuclease). After incubation on ice for 30 min, lysed cells were centrifuged (15 000 rpm or 20 000 g, 30 min, 4 °C), and the supernatant was designated as soluble protein fraction. Subsequently, the resultant pellet was re‐suspended in 90 μL 7 M urea and left on ice for 20 min. After centrifugation (15 000 rpm or 20 000 g, 45 min, 4 °C) the supernatant was designated as insoluble protein fraction. Both soluble and insoluble fractions were analyzed with respect to their protein content by Bradford assay and the expression levels were visualized by SDS‐PAGE® using Novex® 4–12 % Bis⋅Tris gels (200 V, 0.10 mA, 60 min in MOPS buffer) and SimplyBlue SafeStain (Invitrogen).

Using the optimal conditions (TB medium, 0.18 mM IPTG for induction, 15 °C, and 48 h cultivation), large‐scale cultivations in shake flasks (6 L total volume) were performed. After 48 h, cells were harvested (8000 rpm using a Beckman JLA‐8.1000 rotor, 45 min, 4 °C), and the pellet (70–80 g) was stored at −20 °C until further use. After thawing, cells were re‐suspended in Tris⋅HCl buffer (50 mM, pH 7.0, 1 M NaCl) containing lysozyme (1 mg/mL). The resulting suspension (ca. 15 % w/v) was disrupted by sonication (Sonotrode S1, 70 % amplitude, 0.5 s cycle). The crude cell extract was centrifuged (18 000 rpm using a Beckman JA‐20 rotor„ 40 min, 4 °C) and purified by nickel affinity chromatography (Ni‐NTA) using the gravity flow protocol on an Äkta purification system. For this, the column was first equilibrated with Tris‐HCl buffer (50 mM pH 7.0, 1 M NaCl) equilibration buffer. Next, the crude cell extract was loaded into the column and washed with equilibration buffer. Subsequently, the column was washed with 50 mM Tris⋅HCl buffer (pH 7.0, 1 M NaCl) containing 30 mM imidazole and the recombinant His‐tagged protein eluted with 50 mM Tris⋅HCl buffer (pH 7.5, 1 M NaCl) containing 250 mM imidazole. The protein containing fractions were pooled and loaded into a column for size‐exclusion chromatography (Sephadex® G‐25). The sample was desalted with 10 mM Tris⋅HCl buffer (pH 7.0). Protein content was estimated by Bradford assay. Aliquots of the resultant, slightly turbid protein solution were stored at −20 °C and/or freeze‐dried subsequently.

Biological and technical replicates: In this work, a biological replicate (n biological=1) was defined as different shaken flask batch cultivations to produce the same type of protein. This batch production, also called protein preparation, was later purified and used in our experimental setup. Each CAR‐catalyzed reduction reaction was performed independently multiple times. Therefore, the statement n=1 [42] in the legend of the figures means that the enzyme preparation used in that particular reaction was resulted from one single cultivation batch and not from several independent batches. However, it is important to mention that the reaction itself was performed multiple times and the results were shown as mean values of technical replicates. When the error bars representing the standard deviation from the mean are visible in the plot, they were indicated. If the bars are too small to be visualized, it is indicated in the figure legend.

Bradford assay: The Bradford assay performed in this report was adapted from the original reference. [49] The Bradford reagent was prepared by dissolving 100 mg Coomassie brilliant blue G‐250 in 50 mL 95 % (v/v) ethanol. Subsequently, 100 mL of 85 % (w/v) ortho‐phosphoric acid was added. Once the dye was completely dissolved, deionized water was added to a final volume of 1 L. The obtained solution was boiled and filtered to remove the precipitates. Subsequently, the reagent was stored in a dark flask and covered with aluminum foil until further use. The assay was done with a UV‐spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV‐1800 spectrophotometer, Switzerland) using the Bradford reagent prepared and calibrated with BSA protein (concentration of standard BSA ranged from 0.00625 mg/mL to 0.1 mg/mL). For the assay, 100 μL of protein containing samples were added into semi‐micro PMMA cuvettes, filled with 900 μL of the Bradford reagent, and incubated in the dark for ten minutes. Afterwards, the absorbance of the samples was measured at 595 nm and the protein content calculated based on the calibration curve constructed using BSA standard. The assay was performed in triplicates and the protein content expressed as the mean value.

Photometric‐based assay for the determination of enzyme activity: The depletion of NADPH at 340 nm is a photometric‐based assay that was used to determine initial rates activity of NoCAR. For the assay, ATP, and NADPH were freshly dissolved in ultrapure water. Sodium benzoate was used as model substrate and it was solubilized in KOH. Lyophilized enzyme was dissolved in assay buffer. The total volume of the assay was 1 mL and its composition was as follows: 100 mM Tris⋅HCl assay buffer (pH 7.5, 1 mM 1,4‐dithiothreitol and 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), 10 mM sodium benzoate (100 mM in 0.1 M KOH), 30 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, 0.045 mM NADPH. Subsequently, the measurement started after the addition of enzyme (100 μL from the enzyme stock, from either lyophilized form or frozen liquid stocks). The depletion of NADPH was followed on semi‐micro PMMA cuvettes using a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV‐1800 spectrophotometer) at 340 nm and 28 °C for 2 min, similarly as described elsewhere.[ 21 , 50 ] Appropriate blank reactions were carried out in parallel and each reaction was carried in technical duplicates or triplicates (n biological=1; a biological sample was considered different batches of produced and purified enzyme) and the results were shown as average values.[ 42 , 51 ] One enzyme unity (U) was defined as the amount of enzyme that consumes one μmol of NADPH per min under the applied assay conditions. Equations (1) and (2) [44] were used to determine the volumetric activity [U mL−1] and specific activity [U mg−1].

| (1) |

in which: α is the angular coefficient derived from the plot absorbance x time [min−1]; V 1 is the assay volume [mL], d is the dilution factor applied to the enzyme stock; ϵ NADPH is the molar extinction coefficient of NADPH (6300 L mol−1 cm−1), [44] l is the path length in the cuvette [cm], V 2 is the volume of enzyme from the stock used in the assay [mL]; 10 000 is the multiplier due to unity conversions.

| (2) |

in which: volumetric activity [mL−1] is obtained from Equation (1); protein content [mg mL−1] is the total protein content present in the enzyme volume used in the assay and determined by Bradford assay.

Analysis of post‐translational modification of No CAR: For the post‐translational modification of NoCAR with purified EcPPTase and acetyl‐CoA, a standard incubation assay was performed as follows: 50 μL of the NoCAR stock solution (prepared with lyophilized NoCAR in 100 mM Tris⋅HCl buffer, pH 7.5) was added to 25 μL EcPPTase (frozen liquid stock) and 25 μL acetyl‐CoA (initially, from 1 mM stock). The mixture was incubated under the following conditions: 1 h, 28 °C, and 600 rpm. Afterwards, the enzyme activity was determined using the photometric‐based assay described previously. Controls with only NoCAR, NoCAR with acetyl‐CoA, and NoCAR with EcPPTase were also performed and the total assay volume (100 μL) was adjusted with ultrapure water in these cases. Subsequently, parameters such as the amount of EcPPTase (0.075–0.272 mg mL−1 total protein content) and acetyl‐CoA (1–5 mM) as well as the incubation time (30–120 min) were evaluated (for the optimization of the post‐translational assay, see Table S4 and Section 4). The assay was performed in technical triplicates (n biological=1) and the results were shown as average values. [39]

Biocatalytic reduction of sodium benzoate with cofactor regeneration: The reduction reaction was performed with purified NoCAR/EcPPTase (expressed in E. coli Tuner) at a protein concentration of 100 μg/mL in 100 mM MOPS buffer at pH 7.5 containing 6.25 mM MgCl2 and 50 mM β‐d‐(+)‐glucose. Five mM sodium benzoate, 4 mg mL−1 sodium polyphosphate, 0.5 mM NADPH, and 1 mM ATP were added to the reaction mixture. A co‐enzyme mixture containing purified MrPPK (100 μg/mL protein concentration), SmPPK (40 μg/mL protein concentration), EcPPase (25 μg/mL protein concentration) and lyophilized GDH (50 μg/mL) was added to the reaction mixture, totalizing 250 μL of reaction volume. Reactions were carried out for 2 h at 30 °C and 750 rpm. The analysis of sodium benzoate 1, benzaldehyde 2 and benzyl alcohol 3 was carried out in a HPLC Agilent 1100 TC Thermo G1 equipped with a Diode Array Detector (DAD) and an Agilent XDB‐C18 column. The mobile phases were ammonium acetate (5 mM) and 0.5 % v/v acetic acid in water and acetonitrile (ACN) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL min−1. A stepwise gradient was used: 10–50 % ACN (5 min) and 50–90 % ACN (5.0–9.0 min). After additional 30 s, the column was re‐equilibrated to the starting conditions. The compounds were detected at 254 nm. For 1, 2, and 3, calibration curves were determined at 254 nm and linear interpolation used for their quantification (for the visualization of calibration curves, see Section S6). In addition, ethyl para‐hydroxybenzoate (stock solution of 0.5 mg/mL in acetonitrile) was used as internal standard for constructing the external calibration curves and measuring samples in the HPLC. For the analysis, samples were taken over time and the reaction stopped by the addition of quenching buffer (containing ACN/formic acid at 19 : 1 ratio). Subsequently, samples were centrifuged (15 000 rpm or 20 000 g, 5 min, 4 °C) and 100 μL were transferred to HPLC vials for the measurement. The retention times observed for compounds 1, 2, and 3 were 5.0, 5.9, and 4.2 min, respectively.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Biographical Information

Douglas Weber received his M.Sc. (2018) in chemistry from the Federal University of Santa Catarina (Brazil) and is currently undertaking his Ph.D. studies under the guidance of Prof. Dr. Dörte Rother at the Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH and RWTH Aachen University. His research is focused on establishing a toolbox composed of various carboxylate reductases and applying them in multistep cascades to access active pharmaceutical ingredients.

Biographical Information

Annika Neumann completed her B.Sc. in boengineering at Rhine‐Waal University of Applied Sciences in Kleve (2020). As part of her thesis, she worked on synthetic applications of carboxylic acid reductases under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Dörte Rother and Douglas Weber at the Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH.

Biographical Information

David Patsch worked at the Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH for his Master's thesis in biotechnology under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Dörte and Douglas Weber, which he completed in 2019. His work focused on the optimization of cultivation parameters to produce soluble proteins. He is now working at ZHAW in Switzerland on machine learning supervised directed evolution.

Biographical Information

Margit Winkler is a Senior Researcher at the Austrian Center of Industrial Biotechnology and independent Researcher at Graz University of Technology. She was Erwin‐Schrödinger fellow at the University of St. Andrews and Elise‐Richter fellow at Graz University of Technology. In 2019, she received her venia docendi in biotechnology. The focus in the Winkler lab is the discovery and detailed study of enzymes that are not (well) known yet, in order to understand them in depth and to determine whether and how they could become applicable for the synthesis of desired compounds in satisfying amounts and quality.

Biographical Information

Dörte Rother is head of the “biocatalysis” group at the IBG‐1: Biotechnology, Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH and full professor for “synthetic enzyme cascades” at RWTH Aachen University. She received the DECHEMA‐Prize 2018 and the Biotrans Junior Award 2019 for her research on multistep biocatalysis and sustainable process development. In her group bio(techno)logists, chemists and engineers work on solutions to economically and ecologically efficient (multistep) biocatalysis combining enzyme engineering, reaction optimization and process design.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the technical assistance of Doris Hahn and Ursula Mackfeld with plasmid preparation, cloning, and with HPLC analytics. The authors also thank Prof. Dr. Jennifer Andexer (University of Freiburg, Germany) and Prof. Dr. Bernd Nidetzky (Graz University of Technology, Austria) for the donation of the genes encoding for the ATP‐recycling enzymes and EcPPase. The authors received funding in frame of the BioSC FocusLab “HyImPAct” (Hybrid processes for Important Precursor and Active pharmaceutical ingredients) by the Federal State of North‐Rhine Westphalia. The COMET center acib: Next Generation Bioproduction is funded by BMK, BMDW, SFG, Standortagentur Tirol, Government of Lower Austria und Vienna Business Agency in the framework of COMET‐Competence Centers for Excellent Technologies. The COMET‐Funding Program is managed by the Austrian Research Promotion Agency FFG. Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

D. Weber, D. Patsch, A. Neumann, M. Winkler, D. Rother, ChemBioChem 2021, 22, 1823.

References

- 1.R. J. Ouellette, J. D. Rawn, Organic Chemistry, Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2014.

- 2. Hollmann F., Arends I. W. C. E., Holtmann D., Green Chem. 2011, 13, 2285–2313. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sheldon R. A., Woodley J. M., Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 801–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Erdmann V., Lichman B. R., Zhao J., Simon R. C., Kroutil W., Ward J. M., Hailes H. C., Rother D., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 12503–12507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sehl T., Hailes H. C., Ward J. M., Wardenga R., Von Lieres E., Offermann H., Westphal R., Pohl M., Rother D., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 6772–6775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ruff B. M., Bräse S., O'Connor S. E., Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 1071–1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Process for the Preparation of Metaraminol, V. Brenna, D. Marchesi, A. Mihali (Laboratori Alchemia Srl.), US 10087136, 2018.

- 8. Rosenmund K. W., Chem. Ber. 1918, 51, 585. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Iosub A. V., Wallentin C. J., Bergman J., Nat. Catal. 2018, 1, 645–648. [Google Scholar]

- 10.R. Adamn, Organic Reactions, Wiley, New York, 1948.

- 11. Kallscheuer N., Marienhagen J., Microb. Cell Fact. 2018, 17, 1, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Derrington S. R., Turner N. J., France S. P., J. Biotechnol. 2019, 304, 78–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Winkler M., Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2018, 43, 23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Finnigan W., Thomas A., Cromar H., Gough B., Snajdrova R., Adams J. P., Littlechild J. A., Harmer N. J., ChemCatChem 2017, 9, 1005–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Venkitasubramanian P., Daniels L., Rosazza J. P. N., J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 478–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Qu G., Guo J., Yang D., Sun Z., Green Chem. 2018, 4, 777–792. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Napora-Wijata K., Strohmeier G. A., Winkler M., Biotechnol. J. 2014, 9, 822–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. France S. P., Hussain S., Hill A. M., Hepworth L. J., Howard R. M., Mulholland K. R., Flitsch S. L., Turner N. J., ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 3753–3759. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Akhtar M. K., Turner N. J., Jones P. R., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 87–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kaur J., Kumar A., Kaur J., Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 106, 803–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Winkler M., Winkler C. K., Monatsh. Chem. 2016, 147, 575–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Horvat M., Fritsche S., Kourist R., Winkler M., ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 4171–4181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gräslund S., Nordlund P., Weigelt J., Hallberg B. M., Bray J., Gileadi O., Knapp S., Oppermann U., Arrowsmith C., Hui R., et al., Nat. Methods 2008, 5, 135–146.18235434 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Papaneophytou C. P., Kontopidis G., Protein Expression Purif. 2014, 94, 22–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Strohmeier G. A., Eiteljörg I. C., Schwarz A., Winkler M., Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 6119–6123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kunjapur A. M., Prather K. L. J., Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 1892–1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wachtmeister J., Rother D., Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2016, 42, 169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xie M. Z., Shoulkamy M. I., Salem A. M. H., Oba S., Goda M., Nakano T., Ide H., Mutat. Res. Fund. Mol. Mech. Mut. 2016, 786, 41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Horvat M., Winkler M., ChemCatChem 2020, 12, 5076–5090. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Finnigan W., Cutlan R., Snajdrova R., Adams J. P., Littlechild J. A., Harmer N. J., ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 3474–3489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Snijders E., Ned. Geneeskd. Tijdschr. 1924, 64, 85–87. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Parnell A. E., Mordhorst S., Kemper F., Giurrandino M., Prince J. P., Schwarzer N. J., Hofer A., Wohlwend D., Jessen H. J., Gerhardt S., Einsle O., Oyston P. C. F., Andexer J. N., Roach P. L., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 3350–3355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mordhorst S., Siegrist J., Müller M., Richter M., Andexer J. N., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 4037–4041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kunjapur A. M., Cervantes B., Prather K. L. J., Biochem. Eng. J. 2016, 109, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pfeiffer M., Bulfon D., Weber H., Nidetzky B., Adv. Synth. Catal. 2016, 358, 3809–3816. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Te Chu I., Speer S. L., Pielak G. J., Biochemistry 2020, 59, 733–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Competent Cells Overview, http://wolfson.huji.ac.il/expression/procedures/bacterial/novagen-CompCells.pdf, 2003.

- 38. Bezerra M. A., Santelli R. E., Oliveira E. P., Villar L. S., Escaleira L. A., Talanta 2008, 76, 965–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Alexandrov A., Vignali M., LaCount D. J., Quartley E., de Vries C., De Rosa D., Babulski J., Mitchell S. F., Schoenfeld L. W., Fields S., Hol W. G., Dumont M. E., Phizicky E. M., Grayhack E. J., Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2004, 3, 934–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Goedhart J., van Weeren L., Adjobo-Hermans M. J. W., Elzenaar I., Hink M. A., T. W. J. Gadella Jr , PLoS One 2011, 6, 11, e 10.1371/journal.pone.0027321 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Strohmeier G. A., Schwarz A., Andexer J. N., Winkler M., J. Biotechnol. 2020, 307, 202–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cumming G., Fidler F., Vaux D. L., J. Cell Biol. 2007, 177, 7–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.R. R. Burgess, M. P. Deutscher, Methods of Immunology: Guide to Protein Purification, Academic Press, San Diego, 2009.

- 44.H. Bisswanger, Practical Enzymology, 2nd ed., Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken, 2011.

- 45. Jiang S., Nail S. L., Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 1998, 45, 249–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Roy I., Gupta M. N., Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2004, 39, 165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.“Carboxylic acid reductase [Nocardia otitidiscaviarum],” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/WP_029928026.1, 2020.

- 48.“Phosphopantetheinyl transferase, subunit of enterobactin synthase multienzyme complex [Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)],” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/CAQ31055.1/, 2020.

- 49. Bradford M. M., Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schwendenwein D., Fiume G., Weber H., Rudroff F., Winkler M., Adv. Synth. Catal. 2016, 358, 3414–3421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Vaux D. L., Fidler F., Cumming G., EMBO Rep. 2012, 13, 291–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary