Abstract

Introduction

Pregnancy is a vulnerable period that affects long-term health of pregnant women and their unborn infants. Health literacy plays a crucial role in promoting healthy behaviour and thereby maintaining good health. This study explores the role of health literacy in the GeMuKi (acronym for ‘Gemeinsam Gesund: Vorsorge plus für Mutter und Kind’—Strengthening health promotion: enhanced check-up visits for mother and child) Project. It will assess the ability of the GeMuKi lifestyle intervention to positively affect health literacy levels through active participation in preventive counselling. The study also explores associations between health literacy, health outcomes, health service use and effectiveness of the intervention.

Methods and analysis

The GeMuKi trial has a hybrid effectiveness–implementation design and is carried out in routine prenatal health service settings in Germany. Women (n=1860) are recruited by their gynaecologist during routine check-up visits before 12 weeks of gestation. Trained healthcare providers carry out counselling using motivational interviewing techniques to positively affect health literacy and lifestyle-related risk factors. Healthcare providers (gynaecologists and midwives) and women jointly agree on Specific, Measurable, Achievable Reasonable, Time-Bound goals. Women will be invited to fill in questionnaires at two time points (at recruitment and 37th−40th week of gestation) using an app. Health literacy is measured using the German version of the Health Literacy Survey-16 and the Brief Health Literacy Screener. Lifestyle is measured with questions on physical activity, nutrition, alcohol and drug use. Health outcomes of both mother and child, including gestational weight gain (GWG) will be documented at each routine visit. Health service use will be assessed using social health insurance claims data. Data analyses will be conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 26.0. These include descriptive statistics, tests and regression models. A mediation model will be conducted to answer the question whether health behaviour mediates the association between health literacy and GWG.

Ethics and dissemination

The study was approved by the University Hospital of Cologne Research Ethics Committee (ID: 18-163) and the State Chamber of Physicians in Baden-Wuerttemberg (ID: B-F-2018-100). Study results will be disseminated through (poster) presentations at conferences, publications in peer-reviewed journals and press releases.

Trail registration

German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00013173). Registered pre-results, 3rd of January 2019, https://www.drks.de

Keywords: public health, education & training (see medical education & training), primary care, maternal medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Health literacy will be measured subjectively as well as objectively.

All questionnaires are self-administered, which might lead to overestimation.

A comprehensive recruitment strategy, supported by all German statutory health insurance companies, will contribute to inclusion of pregnant women with different health literacy levels.

Women not proficient in German language are not included, which might result in exclusion of migrants and illiterate women.

As inclusion takes place before the 12th week of gestation, other vulnerable groups that are less likely to use early antenatal care might not be included (such as women under the age of 18 years, heavy drug or alcohol users).

Introduction

Health literacy describes a person’s ability to access, understand, appraise and apply health information to make informed decisions regarding their health.1 Inadequate health literacy is associated with a diversity of negative outcomes, such as more hospital visits and medication use, less utilisation of screening as well as negative health behaviours, such as drug and alcohol use and unhealthy nutrition.2 3 Accordingly, adequate health literacy is important to achieve and maintain good health.

A population-based study in 2014 revealed that more than 50% of the German population has an inadequate health literacy level.4 As a result, a group of experts from academia, practice and policy was formed to develop a ‘National Action Plan Health Literacy’ (NAP) to improve health literacy in Germany.5 6 The action plan advocates for addressing health literacy both early in life and through measures at the healthcare system level, for example, by facilitating navigation, creating user-friendly information as well as comprehensible communication between health professionals and users.5 The action plan points out that measures to strengthen health literacy should focus on various user groups in the healthcare system, particularly vulnerable groups, for example, people with limited socioeconomic resources and people with migration backgrounds.

Pregnancy is a vulnerable time in which women are confronted with a diversity of changes, not only physically, but also with regards to the responsibilities of being pregnant and becoming a parent. These changes make women and parents sensible to preventive health information.7 However, the large quantity and diverse quality of the available information make it difficult for women to understand and decide which information is relevant to them.8 Studies demonstrate that compared to women with adequate health literacy, women with inadequate level of health literacy more frequently smoke during pregnancy, do not exclusively breast feed their child the first months after birth and do not engage in prenatal care at the beginning of the pregnancy.9–13 These lifestyle behaviours are likely to impact long-term health outcomes for both mother and child. Through a process referred to as perinatal programming, external factors such as maternal health behaviours influence the fetal development alongside genetic factors and thereby affect the risk of developing obesity and chronic diseases.14 For example, a pregnant woman’s nutrition and physical activity can result in excessive gestational weight gain (GWG). GWG is linked to increased pregnancy and birth complications, including the risk of obesity or chronic conditions, such as type 2 diabetes in the offspring.15 Therefore, to reduce these risk factors, it seems important that pregnant women find, understand and apply health information relevant to a healthy lifestyle and GWG during pregnancy.

Research suggests that health literacy-sensitive educational interventions promote desirable health outcomes such as self-care behaviour, particularly physical activity.16 To date however, little is known about the role of health literacy during pregnancy. Health literacy interventions for pregnant women and studies examining the effectiveness of such are also lacking.17 18 Interventions that exist do not measure health literacy directly, which leads to the lack of evidence in this area.17 18 This study seeks to address this gap. It explores the relationship of health literacy with other variables within the GeMuKi (acronym for ‘Gemeinsam Gesund: Vorsorge plus für Mutter und Kind’—Strengthening health promotion: enhanced check-up visits for mother and child) Project. The GeMuKi Project examines a novel lifestyle intervention during pregnancy. The intervention consists of a brief lifestyle intervention implemented during routine prenatal check-ups (also often referred to as antenatal appointments) in the German state of Baden-Wuerttemberg. The intervention aims to contribute to a healthy lifestyle and adequate GWG by strengthening health literacy of pregnant women. Building on the NAP, GeMuKi seeks to strengthen health literacy through (a) involving pregnant women actively in the counselling, (b) enabling participation when setting joint goals to improve health behaviour and (c) making health information understandable in counselling sessions.

For the present study, it is hypothesised that (a) health literacy levels are positively affected by the GeMuKi intervention through increased knowledge, more active participation, better adherence to lifestyle goals; and (b) health literacy has an impact on further variables, including health outcomes, health behaviour as well as health service use during pregnancy. The following research questions will be answered:

Can health literacy levels in pregnant women be improved by means of the GeMuKi lifestyle intervention during regular check-ups?

Do health outcomes, health behaviour and health service use differ between pregnant women with high and low health literacy levels participating in the GeMuKi lifestyle intervention trial?

Is the association between health literacy and weight development during pregnancy mediated by health behaviour?

Methods

Data on health literacy, health outcomes and health service use during pregnancy will be collected in the GeMuKi Project, which started in October 2017 and will end in March 2022. The project uses a hybrid effectiveness–implementation design (type II). Hybrid effectiveness–implementation designs allow for the blended assessment of clinical effectiveness and implementation to rapidly translate research results into practice. Type II indicates that clinical and implementation areas are tested simultaneously as opposed to other types.19 The study consists of two arms: the intervention group receives a brief counselling (GeMuKi) in addition to regular care, while the control group receives regular care. The lifestyle intervention takes place within the 11 regular check-up visits during pregnancy and the infants’ first year. The present study will focus on the period from the first check-up during pregnancy until birth. It will consider only check-ups conducted by gynaecologists and midwives. Since the study takes place in Germany, the setting needs explanation: in the German healthcare system, women usually visit a gynaecologist to confirm a pregnancy and from then onward visit their gynaecologist and if possible a midwife for check-up appointments. A detailed description of the general design of the GeMuKi Project can be found elsewhere.20 Health literacy is a complex concept that has been insufficiently studied during the time of pregnancy. Therefore, a separate in-depth analysis of health literacy-related aspects is warranted. This paper particularly focuses on health literacy and addresses research questions that have not been described elsewhere, as they go beyond the evaluation of effectiveness and implementation of the GeMuKi Project.

Study sample

The study sample is recruited in participating gynaecologist practices. Gynaecologists determine the eligibility of pregnant women, using the following inclusion criteria: ≥18 years old, <12 weeks of gestation at recruitment and proficient German language skills. Women are not eligible when scoring high on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, defined as a total score of greater than 9 (probability of a depression) or a score of 3 (answering ‘yes, very often’) on item number 10 ‘The thought of harming myself has occurred to me’. The exclusion is justified by the probability of depression and/or suicidal thoughts for which women need urgent and particular care. In the event of the explained scoring, the project team also suggests another project, which takes place simultaneously with a focus on maternal depression. This procedure aims to reduce the risk of bias that could be introduced by co-interventions.20

The sample is expected to include a wide range of health literacy levels, since inclusion criteria are widely defined and different statutory health insurance companies partake in the project with different characteristics of the insured people. The inclusion of different insurance companies that exist in Germany allows to include women with diverse socioeconomic status, migration background and health status (e.g., smoking behaviour, obesity and cardiovascular disease).21 Moreover, about 84% of all pregnant women come for the first check-up before the 13th week of pregnancy; 80% attend at least 10 preventive examinations during pregnancy.22

A more detailed description of the study sample is provided by Alayli et al.20 They estimated 1860 participants to be needed in the study. For the health literacy-related research questions described here, this sample size is considered sufficient. To counteract cumulating type 1 errors due to multiple testing, Bonferroni corrections will be made.

Health literacy strengthening intervention

GeMuKi is a multiprofessional computer-assisted lifestyle intervention.23 During pregnancy, the intervention is carried out by gynaecologists and midwives. It aims at strengthening health literacy and positively affecting lifestyle-related risk factors in women and their infants.

Preventive counselling to strengthen health literacy

Health literacy will be strengthened during the counselling sessions by actively involving pregnant women in the decision-making process, wich lifestyle topic to focus on in the counselling. This way, women reveal themselves in which areas they need further counselling and the healthcare provider does not provide information when it is not needed. Participation is one of the recommendations of the NAP to improve health literacy. The topics of the counselling are based on the national recommendations on a health-promoting lifestyle during pregnancy and after birth from the ‘Healthy Start—Young Family Network’ (Netzwerk Gesund ins Leben).24 The recommendations provide gynaecologists, midwives, paediatricians and other medical professionals with a basis for counselling a healthy lifestyle.24 The first recommendations from 2012 were updated in 2018, adding recommendations for the time before pregnancy and around the conception phase.24

To strengthen health literacy of the participants, healthcare providers receive a training, focusing on lifestyle during pregnancy, including nutrition and physical activity. Healthcare providers are trained to communicate key messages from the recommendations by means of Motivational Interviewing (MI). The counselling is practised in role-plays with all participants. As behaviour change is considered a health literacy skill, MI is used, which is built on the notion that people autonomously change their behaviour.25 This should be considered by healthcare providers when carrying out the counselling: healthcare providers are supposed to actively listen and react with open-ended questions to trigger behaviour change. It is in line with the NAP, which recommends that health professionals should communicate sensitively to the health literacy levels of the individuals in order to positively affect their health literacy and thus health behaviour. At the end of each counselling appointment, the participant, along with the support of the healthcare provider, will set up SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Reasonable, Time-Bound) goals to positively change behaviour, which can be accomplished until the next appointment. The SMART goals are individualised and adapted to the capacities of women. This way, the counselling and the SMART goals are tailored to the health literacy levels of women.

Digital intervention component to strengthen health literacy

Digitalisation is used as recommended by the NAP to strengthen health literacy by providing pregnant women with the GeMuKi app. The app is used by the participants to (1) receive health information on pregnancy and (2) receive the SMART goals as push notifications. The app is designed in an easy-to-handle way, which is accessible for women with different health literacy levels. App usage on mobiles phones is the most appropriate way to reach women, as research suggests that women with low level of health literacy rather use mobile phones than email communication or the internet.26 For purposes of the evaluation study, the app is also used by pregnant women to fill in questionnaires.

Healthcare providers enter results from the prenatal check-ups into the maternity and child medical record booklets. These data, along with GWG and the chosen lifestyle topic, are entered into the GeMuKi-Assist counselling tool. The tool is a component of the telehealth platform GeMuKi-Assist, which was particularly developed for the healthcare providers. The counselling tool also provides supporting questions on each counselling topic that healthcare providers can ask during the counselling, which are built on the tenets of MI. In this platform, healthcare providers document the SMART goals during each counselling, which later will be displayed in the women’s app. Via the counselling tool, the gynaecologist and midwife of a particular woman have access to the chosen lifestyle topics, goals and medical record booklet data to ensure continuity of the counselling. Study coordinators are available in every study region to support healthcare providers with any question arising, including questions on the content of the counselling, the counselling procedure, data entry and technical support. In addition to that, handouts and folders are handed to all participating healthcare providers before patient recruitment starts.

Variables

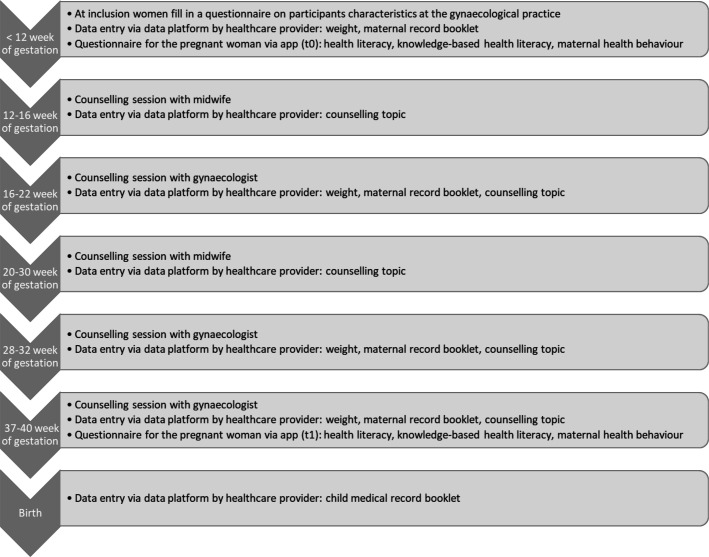

Table 1 provides a summary of the variables that will be used in the data analysis. Data will be derived from various data sources collected in the GeMuKi Project: weight, data from the maternity record booklet and child medical record booklet are entered by healthcare providers in the GeMuKi-Assist counselling tool. The app entails questionnaires that women fill in at two time points during pregnancy (figure 1). Participating health insurance companies provide health insurance claims data.

Table 1.

Variables and data sources

| Variable | Data source | Measures |

| Participant characteristics | Paper-based questionnaire | Age, weight, height (also from the child’s father) |

| Health literacy | Questionnaires, answered in the app | HLS-EU-16, BHLS, knowledge-based questions |

| Maternal health outcomes (including GWG) | Maternity record booklet data, entered into the counselling tool | Health data such as weight, gestational diabetes mellitus |

| Fetal and neonatal health outcomes | Child medical record booklet data, entered into the counselling tool | Health data such as large for gestational age |

| Maternal health behaviour | Questionnaires, answered in the app | PPAQ, FFQ, alcohol and smoking |

| Health service use | Health insurance claims data | Inpatient and outpatient treatment, medication use, aids and remedies, sick leave |

BHLS, Brief Health Literacy Screener; FFQ, Food Frequency Questionnaire; GWG, gestational weight gain; HLS-EU-16, Health Literacy Survey-16 items; PPAQ, Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire.

Figure 1.

Overview of counselling sessions and time points of data collection.

Participant characteristics

Demographic information and anthropometric data (such as height and length) to characterise the sample will be derived from a paper-based questionnaire handed out at baseline in the GeMuKi Project (before the 12th week of gestation; figure 1) of both the pregnant woman and the infant’s father. These data will give information on the body mass index (BMI) of the parents, which later will be included in the analysis.20

Health literacy

Health literacy is assessed using different instruments: the Health Literacy Survey (HLS-EU-16) will be used at baseline, to assess a detailed description of the general health literacy levels of pregnant women. When applied in the German general population, it has shown a high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90).27 Additionally, this instrument has been used in other studies in Germany, offering the possibility to compare results with our study population. Questions can be answered on a 5-point Likert scale (‘very difficult’–‘very easy’; ‘I don’t know’). Since the HLS-EU-16 also includes questions on illness, these questions may not be suitable for our study population as we cannot assume that all pregnant women have some kind of illness and pregnancy cannot be translated into illness. Therefore, we have supplemented the regular 16-item HLS-EU with two further questions, which particularly aim at pregnancy (‘How easy would you say it is to find information on your pregnancy?’ and ‘How easy would you say it is to use information the doctor gives you to make decisions about your pregnancy?’). Since paper-based questionnaires provide the option to not tick an answer and skip questions, for all questions the additional response category ‘I do not want to answer this question’ is included in the app-based survey. To asses change in health literacy as a result of the GeMuKi intervention, the Brief Health Literacy Screener (BHLS) will be used at both time points (t0 and t1). The tool screens for inadequate health literacy using three questions, which can be answered on a 5-point Likert scale (‘never’–‘always’ and additionally ‘I do not want to answer this question’). Other studies demonstrated high internal consistency for this instrument with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.80 among hospital patients.28 Modification of health literacy levels will be observed by assessing changes in the proportion of study participants with inadequate health literacy between the beginning and end of pregnancy.

Knowledge-based health literacy

In addition to the above described measures, which provide subjective estimates of health literacy, an objective measure of health literacy was developed, consisting of knowledge-based questions. Knowledge-based questionnaires can be used to assess health literacy because knowledge acts as a proxy for health literacy.29 Each question was developed based on the topics of the national recommendations discussed during counselling. They cover the following topics: weight development, nutrition, alcohol and drug use, physical activity, water intake and breast feeding. The questionnaire was developed by researchers of the project with the support of nutritionists who work in the project. Answers can be given on a ‘yes/no/I don’t know’ scale. The questionnaire will be statistically analysed calculating frequencies of correct answers.

Maternal health outcomes

During every routine prenatal visit, practice assistants enter data from the maternity record booklet into the GeMuKi-Assist counselling tool. To evaluate maternal health outcomes, one composite measure will be used, derived from the following variables: pre-eclampsia or pregnancy-induced hypertension, gestational diabetes mellitus, caesarean section and preterm delivery. This measure has been proposed in a Delphi study on the evaluation of lifestyle interventions during pregnancy.30

Fetal and neonatal health outcomes

Health data of the child will be recorded at birth in the child medical record booklet. It entails among others the following variables: small for gestational age and large for gestational age.

Maternal health behaviour

Physical activity will be measured using the Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire. This instrument assesses the duration, frequency and intensity of physical activity in pregnant women. It has been used internationally and exhibits Cronbach’s alphas above the threshold of 0.70.31 32 Nutrition will be assessed using an adjusted version of the Food Frequency Questionnaire from the German Health Examination Survey for Adults.33 This instrument evaluates the frequency of consumption of food groups. Alcohol and smoking is assessed using questions from the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents.34

Gestational weight gain

Maternal weight is documented in every pregnancy check-up visit using the maternity record booklet and entered into the telehealth platform GeMuKi-Assist. In this study, the recommended range of GWG is defined according to the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine.35 The recommendations are based on prenatal BMI and are displayed in table 2.

Table 2.

Weight gain recommendations adjusted by BMI

| Weight | BMI (kg/m2) | Recommended weight gain (range in kg) |

| Underweight | <18.5 | 12.5–18 |

| Normal weight | 18.5–24.9 | 11.5–16 |

| Overweight | 25.0–29.9 | 7–11.5 |

| Obese | ≥30.0 | 5–9 |

BMI, body mass index.

Weight gain above the recommendation is classified as excessive weight gain. These recommendations were recently confirmed by 25 pooled cohort studies.36

Health service use

Data on health service use will be based on health insurance claims and delivered by the participating health insurance companies. These data are pseudonymised and entail data on inpatient and outpatient treatment (diagnosis, duration of hospital stay and costs), medication use (pharmaceuticals, amount and costs), aids and remedies (duration of service and costs), and sick leave periods (duration of sick leave and sick pay).37

Data analysis

Plausibility checks of the data will be performed continuously during data collection and before data analysis. Multiple imputation methods will be used to deal with missing values. Descriptive statistics will be used to analyse participant characteristics, such as age and BMI at baseline. Correlations will be calculated to examine whether health literacy levels vary depending on BMI, health outcomes, socioeconomic status and migration background.

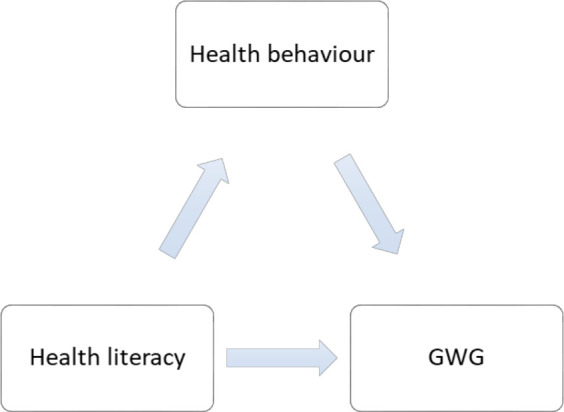

Differences in means will be calculated to answer whether the intervention improved health literacy levels in pregnant women. Health literacy change will be analysed comparing the proportion of women with inadequate health literacy at baseline and end of pregnancy. Regression analysis will be used to answer the question whether health literacy levels influence the effectiveness of GeMuKi as well as maternal and fetal health outcomes and health service use. A mediation analysis will be conducted to answer the question whether health behaviour (mediator) mediates the association between health literacy (independent variable) and GWG (dependent variable) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mediation model. GWG, gestational weight gain.

Patient and public involvement

Within the frame of the GeMuKi Project, a process evaluation will be conducted, including interviews with participating pregnant women. The interviews aim to answer questions on hindering and supporting factors of the intervention. The overall results of the GeMuKi Project will be made available to all participants at the end of the project period.

Ethics and dissemination

The GeMuKi Project was approved by the University Hospital of Cologne Research Ethics Committee (ID: 18-163) and the State Chamber of Physicians in Baden-Wuerttemberg (ID: B-F-2018-100). Inference to study participants is not possible since the collected data are pseudonymised in accordance with the European Union General Data Protection Regulation. Written informed consent will be obtained from all study participants at baseline. Participants are reassured that they are free to withdraw from the study at any time during the study without consequences. Study results will be disseminated through (poster) presentation at conferences and publications in peer-reviewed journals. Additionally, press releases are made to inform the general public. A closing event is planned with stakeholders to discuss the potential implementation of GeMuKi into regular care.

Discussion

To date there is little research on health literacy in pregnant women and interventions to improve health literacy in this population according to two newly published systematic reviews.17 18 Even though pregnant women are confronted with a lot of health information during pregnancy, it is difficult to differentiate between the quality of information and which one is important.8 This is particularly important in light of informed decision-making, not only to make a decision for their own health but also for the infant.38 For instance, adequate health literacy supports pregnant women in deciding to use complementary medicine products.39

Studies on health literacy in pregnant women are scarce and if they exist, they do not evaluate the change of health literacy as a result of an intervention.17 To our knowledge, this is the first study assessing the impact of an intervention that aims at improving health literacy in pregnant women and the influence of health literacy on various outcomes during pregnancy, such as GWG, lifestyle and health service use. It is hypothesised that health literacy is increased by a lifestyle intervention that is health literacy-sensitive.

Pregnancy offers an important phase, in which the health literacy level of pregnant women is not only relevant to their own health but also to that of the (unborn) child. This study is set up at the very beginning of the pregnancy to explore the impact of health literacy on the health of both mother and child. The GeMuKi Project evaluates a low-threshold lifestyle intervention that is accessible for all pregnant women as it is provided in the regular check-ups during pregnancy. Previous research supports that low-threshold interventions are easily accessible for women with both high and low health literacy levels and lead to successful implementation of an intervention.40 The intervention consists of brief counselling sessions conducted by means of MI, a technique with which healthcare providers can tailor the counselling to the health literacy levels of pregnant women. MI techniques also allow women to participate actively in the counselling sessions, strengthening the autonomy, which is a skill that positively affects health literacy.1 Research suggests that MI is effective in promoting and positively changing health behaviour,41 which in turn results in better health outcomes according to the model of Sorensen et al.1 To be health literacy-sensitive, the intervention makes use of digitalisation. Each counselling session is concluded with a SMART goal, defined by both the healthcare provider and the woman and recorded in the counselling tool, which will then be displayed in the GeMuKi app of the pregnant woman. The app also provides further information on topics that pregnant women might be concerned with and are easily accessible. Using digitalisation to promote health literacy has been part of other studies and is proven to be effective.40 Briefly worded, the GeMuKi Project focuses on the empowerment of participating women, which is a crucial health literacy skill1 and is seen as an empowerment tool for mothers.42 The empowerment is supported by active participation of the women in the counselling and goal setting, which will strengthen the autonomy, support behaviour change and thus result in better health outcomes.

An advantage of this study is that we will answer questions that arise with regards to health literacy in pregnant women. Studies to date have measured health literacy in pregnant women, however it was only one of many secondary outcome variables.17 18 To better understand the association between health literacy of pregnant women and (health) outcomes in both mother and child, we analyse different data using questionnaires, data entry from the healthcare provider and health insurance data of participants. Additionally, health literacy is measured using different instruments. The HLS-EU-16 is tailored to the study participant’s situation by adding questions regarding pregnancy. The BHLS is used at the beginning and end of the pregnancy to assess for changes in the health literacy levels. Knowledge-based health literacy questions were developed to assess objectively whether women understand health information on lifestyle during pregnancy and answer these questions correctly.

However, some limitations have to be taken into consideration with regard to this study. Associations between health literacy and other variables are examined within the GeMuKi Project. Hence, we cannot conclude that the results can be generalised to other interventions. Additionally, the implementation of the counselling is not monitored, which is why it is not guaranteed that healthcare providers follow the principles of promoting health literacy and implement what was taught in the training. With regard to the training, it must be mentioned that health literacy is a secondary outcome of the GeMuKi Project, which is why health literacy did not take as much time as lifestyle topics during the training. Even with the inclusion of different health insurance companies, illiterate pregnant women might not be able to fill in the baseline questionnaire and will be excluded from the study, which rules out an important group that most likely requires health literacy strengthening. Even though the GeMuKi app was developed to be easily manageable, it cannot be guaranteed that this is sufficient for women who have low digital health literacy skills. This might impact the handling of the app. The app entails self-administered questionnaires, which are prone to overestimation, a further limitation we have to take into account.

Results of this study can contribute to the better understanding of health literacy on various outcomes and health service use, particularly during pregnancy. Study findings can provide insights for researchers and policymakers, who want to develop and fund health literacy-sensitive interventions starting during pregnancy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the GeMuKi consortium: Platform Nutrition and Physical Activity (peb), Institute of Health Economics and Clinical Epidemiology, University Hospital of Cologne (IGKE), Fraunhofer Institute for Open Communication Systems (FOKUS), BARMER and Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians (KVBW). We would like to acknowledge in particular Michael John and his team, who developed the telehealth platform GeMuKi-Assist, used for data collection. We would also like to thank the health insurance companies that provide health insurance claims data. Moreover, we would like to thank Isabel Lück and Judith Kuchenbecker for the input in developing the knowledge-based health literacy questions.

Footnotes

Contributors: FN, AA and SS developed the study protocol. FK, LL and AS are members of the research team, contributed to the design of the study and provided continuous feedback. A-MB is the coordinator of the GeMuKi consortium, who also provided feedback. FN wrote the manuscript. All authors provided comments and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study is funded by the Innovation Fund of the Federal Joint Committee (G-BA) from October 2017 to September 2021 in the section 'New forms of care', module 3: Improving communication with patients and promoting health literacy (project no. 01NVF17014).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.Sørensen K, Van den Broucke S, Fullam J, et al. Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012;12:80. 10.1186/1471-2458-12-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, et al. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:97–107. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aaby A, Friis K, Christensen B, et al. Health literacy is associated with health behaviour and self-reported health: a large population-based study in individuals with cardiovascular disease. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2017;24:1880–8. 10.1177/2047487317729538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schaeffer D, Berens E-M, Vogt D. Health literacy in the German population. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2017;114:53–60. 10.3238/arztebl.2017.0053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schaeffer D, Hurrelmann K, Bauer U, et al. [National Action Plan Health Literacy: Need, Objective and Content]. Gesundheitswesen 2019;81:465–70. 10.1055/a-0667-9414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schaeffer D, Gille S, Hurrelmann K. Implementation of the National action plan health literacy in Germany-Lessons learned. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17. 10.3390/ijerph17124403. [Epub ahead of print: 19 06 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Briscoe L, Lavender T, McGowan L. A concept analysis of women's vulnerability during pregnancy, birth and the postnatal period. J Adv Nurs 2016;72:2330–45. 10.1111/jan.13017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sayakhot P, Carolan-Olah M. Internet use by pregnant women seeking pregnancy-related information: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:65. 10.1186/s12884-016-0856-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smedberg J, Lupattelli A, Mårdby A-C, et al. Characteristics of women who continue smoking during pregnancy: a cross-sectional study of pregnant women and new mothers in 15 European countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:213. 10.1186/1471-2393-14-213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaufman H, Skipper B, Small L, et al. Effect of literacy on breast-feeding outcomes. South Med J 2001;94:293–6. 10.1097/00007611-200194030-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lupattelli A, Picinardi M, Einarson A, et al. Health literacy and its association with perception of teratogenic risks and health behavior during pregnancy. Patient Educ Couns 2014;96:171–8. 10.1016/j.pec.2014.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poorman E, Gazmararian J, Elon L, et al. Is health literacy related to health behaviors and cell phone usage patterns among the text4baby target population? Arch Public Health 2014;72:13. 10.1186/2049-3258-72-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Endres LK, Sharp LK, Haney E, et al. Health literacy and pregnancy preparedness in pregestational diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004;27:331–4. 10.2337/diacare.27.2.331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pico C, Palou A. Perinatal programming of obesity: an introduction to the topic. Front Physiol 2013;4:255. 10.3389/fphys.2013.00255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freeman DJ. Effects of maternal obesity on fetal growth and body composition: implications for programming and future health. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2010;15:113–8. 10.1016/j.siny.2009.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osborn CY, Paasche-Orlow MK, Bailey SC, et al. The mechanisms linking health literacy to behavior and health status. Am J Health Behav 2011;35:118–28. 10.5993/AJHB.35.1.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nawabi F, Krebs F, Vennedey V, et al. Health literacy in pregnant women: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18. 10.3390/ijerph18073847. [Epub ahead of print: 06 04 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zibellini J, Muscat DM, Kizirian N, et al. Effect of health literacy interventions on pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review. Women Birth 2021;34:180–6. 10.1016/j.wombi.2020.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, et al. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care 2012;50:217–26. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alayli A, Krebs F, Lorenz L, et al. Evaluation of a computer-assisted multi-professional intervention to address lifestyle-related risk factors for overweight and obesity in expecting mothers and their infants: protocol for an effectiveness-implementation hybrid study. BMC Public Health 2020;20:482. 10.1186/s12889-020-8200-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffmann F, Koller D. [Different Regions, Differently Insured Populations? Socio-demographic and Health-related Differences Between Insurance Funds]. Gesundheitswesen 2017;79:e1–9. 10.1055/s-0035-1564074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.RKI . Schwerpunktbericht Der Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes: Gesundheit von Kindern und Jugendlichen. Berlin: Robert Koch Institut, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lück I, Kuchenbecker J, Moreira A. Development and implementation of the Ge-MuKi lifestyle intervention: motivating parents-to-be and young parents with brief interventions. Ernahrungs Umschau 2020;67:S77–83. 10.4455/eu.2020.056 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koletzko B, Cremer M, Flothkötter M, et al. Diet and Lifestyle Before and During Pregnancy - Practical Recommendations of the Germany-wide Healthy Start - Young Family Network. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 2018;78:1262–82. 10.1055/a-0713-1058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: helping people change. 3rd edn. New York: Guilford Press, 2013: 3. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barber MN, Staples M, Osborne RH, et al. Up to a quarter of the Australian population may have suboptimal health literacy depending upon the measurement tool: results from a population-based survey. Health Promot Int 2009;24:252–61. 10.1093/heapro/dap022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jordan S, Hoebel J. [Health literacy of adults in Germany: Findings from the German Health Update (GEDA) study]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2015;58:942–50. 10.1007/s00103-015-2200-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wallston KA, Cawthon C, McNaughton CD, et al. Psychometric properties of the brief health literacy screen in clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:119–26. 10.1007/s11606-013-2568-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu C, Wang D, Liu C, et al. What is the meaning of health literacy? A systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Fam Med Community Health 2020;8:e000351. 10.1136/fmch-2020-000351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rogozinska E, D'Amico MI, Khan KS, et al. Development of composite outcomes for individual patient data (IPD) meta-analysis on the effects of diet and lifestyle in pregnancy: a Delphi survey. BJOG 2016;123:190–8. 10.1111/1471-0528.13764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tosun OC, Solmaz U, Ekin A, et al. The Turkish version of the pregnancy physical activity questionnaire: cross-cultural adaptation, reliability, and validity. J Phys Ther Sci 2015;27:3215–21. 10.1589/jpts.27.3215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fathnezhad Kazemi A, Hajian S, Sharifi N. The psychometric properties of the Persian version of the pregnancy physical activity questionnaire. Int J Women’s Health Reprod Sci 2019;7:54–60. 10.15296/ijwhr.2019.09 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haftenberger M, Heuer T, Heidemann C, et al. Relative validation of a food frequency questionnaire for national health and nutrition monitoring. Nutr J 2010;9:36. 10.1186/1475-2891-9-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koch-Institut R. Studie Zur Gesundheit von Kindern und Jugendlichen. Elternfragebogen 6690-2. Berlin, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rasmussen KM, Yaktine AL, eds. Weight gain during pregnancy: reexamining the guidelines. The National academies collection: reports funded by National Institutes of health. Washington (DC), 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.LifeCycle Project-Maternal Obesity and Childhood Outcomes Study Group, Voerman E, Santos S, et al. Association of gestational weight gain with adverse maternal and infant outcomes. JAMA 2019;321:1702–15. 10.1001/jama.2019.3820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neubauer S, Zeidler J, Graf von der Schulenburg JM. Grundlagen und Methoden von GKV-Routinedatenstudien. Leibniz Universität Hannover, center for health economics research Hannover (CHERH), 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA, eds. Health literacy: a prescription to end confusion. Washington (DC), 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barnes LAJ, Barclay L, McCaffery K, et al. Women's health literacy and the complex decision-making process to use complementary medicine products in pregnancy and lactation. Health Expect 2019;22:1013–27. 10.1111/hex.12910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lanpher MG, Askew S, Bennett GG. Health literacy and weight change in a digital health intervention for women: a randomized controlled trial in primary care practice. J Health Commun 2016;21 Suppl 1:34–42. 10.1080/10810730.2015.1131773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morton K, Beauchamp M, Prothero A, et al. The effectiveness of motivational interviewing for health behaviour change in primary care settings: a systematic review. Health Psychol Rev 2015;9:205–23. 10.1080/17437199.2014.882006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Porr C, Drummond J, Richter S. Health literacy as an empowerment tool for low-income mothers. Fam Community Health 2006;29:328–35. 10.1097/00003727-200610000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.