Abstract

The transition from pluripotent to somatic states marks a critical event in mammalian development, but remains largely unresolved. Here we report the identification of SS18 as a regulator for pluripotent to somatic transition or PST by CRISPR-based whole genome screens. Mechanistically, SS18 forms microscopic condensates in nuclei through a C-terminal intrinsically disordered region (IDR) rich in tyrosine, which, once mutated, no longer form condensates nor rescue SS18−/− defect in PST. Yet, the IDR alone is not sufficient to rescue the defect even though it can form condensates indistinguishable from the wild type protein. We further show that its N-terminal 70aa is required for PST by interacting with the Brg/Brahma-associated factor (BAF) complex, and remains functional even swapped onto unrelated IDRs or even an artificial 24 tyrosine polypeptide. Finally, we show that SS18 mediates BAF assembly through phase separation to regulate PST. These studies suggest that SS18 plays a role in the pluripotent to somatic interface and undergoes liquid-liquid phase separation through a unique tyrosine-based mechanism.

Subject terms: Intrinsically disordered proteins, Cell biology, Molecular biology, Embryonic stem cells

Emerging evidence suggests that exit from pluripotency is a regulated, rather than passive process. Here the authors identify a requirement for SS18-mediated Brg/Brahma-associated factors (BAF) chromatin remodeling complex assembly during exit from pluripotency, and that SS18 promotes BAF assembly through liquidliquid phase separation.

Introduction

At the start of mammalian development, a fertilized egg is totipotent, then undergoes successive cell divisions to become a blastocyst from which naive pluripotent stem cells can be derived1–5. Then, blastocysts undergo implantation to mark the beginning of fetal development for both the fetus and the placenta. During or immediately after implantation, cells from the inner cell mass in a blastocyst begin to differentiate and eventually endow the three germ layers and germ cells. While this process occurs without any appreciable difficulty in vivo and naive ESCs undergo spontaneous differentiation once cultured under conditions without LIF or other supporting factors2,6–8, one may assume that little regulatory mechanism is required for or built into this process.

Given the precision nature during mammalian development, one would argue that each cell division is a fate decision process meticulously regulated. One such example is the pluripotent to somatic transition or PST during early embryonic development. Derived from inner cell mass or ICM of mouse blastocysts1,5, mESCs are in vitro copies of ICM, representing the pluripotent state quite faithfully by virtue of their ability to regenerate all fetal tissues when reintroduced to blastocysts even after prolong culture and storage in vitro9. In vitro, mESCs are capable of differentiating into cells for all lineages as well3,10. Tcf3 (a.k.a. Tcf7l1) has been reported to play a dominant role in pluripotency exit by mediating lineage commitment11–14. On the other hand, Tfe3, a master regulator of lysosomal biogenesis15, mediates pluripotency exit by targeting Esrrb through stage-specific subcellular localization16. In addition, pluripotency exit can be regulated at various levels, including but not limited to transcription factors11,12,16, signal transduction pathway12,16,17, epigenetics18, lincRNAs19. While these sophisticated methods and elegant models used for mESC differentiation in vitro and in vivo, mechanistic insights at the molecular and chromatin level are still lacking at the present.

The ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes BAFs (Brg/Brahma-associated factors), are also mammalian switch/sucrose nonfermentable (SWI-SNF) initially found in yeast, that consist of 15 subunits encoded by 29 genes, have been shown to play critical roles in self-renewal and pluripotency of ESCs, development20 and human tumor21. Among these subunits, BRG1 is the enzyme core of BAF complexes and has been shown to be required for the maintenance of stem cells22–24 and DPF2, as the canonical BAF specific subunit, is required for maintaining pluripotency and ESCs differentiation25. However, it remains to be determined if any of the BAFs are required for pluripotency exit.

CRISPR-Cas9 is an emerging technology that has been adopted for whole genome screen26. In this report, we describe a PST system based on inducible over-expression of cJUN in naive mESCs and its adaption for whole genome screening to identify regulators for PST. We identify SS18, a component of BAFs, as a regulator at the pluripotent-somatic interface.

Results

Genome-wide Cas9 screen identifies factors regulating PST

Mouse ESCs or mESCs are naïve pluripotent stem cells capable of self-renewal indefinitely while preserving the capacity to differentiate into any of the three somatic germ layer lineages, thus representing an ideal system to study pluripotent to somatic transition or PST. To identify regulators for PST, we took advantage of our early finding that cJUN behaves as a guardian for the somatic fate in MEFs and is capable of driving mESCs to differentiate rapidly27 (Supplementary Fig. 1a–c). Using this inducible system, we further show that exposure to cJUN for up to 6 h results in about 50% of the starting mESCs capable of regaining naive pluripotency (Supplementary Fig. 1d). However, exposure beyond 8 h leads to <15% of the cells regaining the naive state, suggesting that there is a window of sensitivity between 6–8 h that marks the point of no return or a checkpoint between pluripotent and somatic states (Supplementary Fig. 1d, e). RNAseq analysis further reveals rapid down- and up- regulation of pluripotent genes and somatic ones between 4–8 h, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1f, g), thus confirming the observed fate transition at the molecular level.

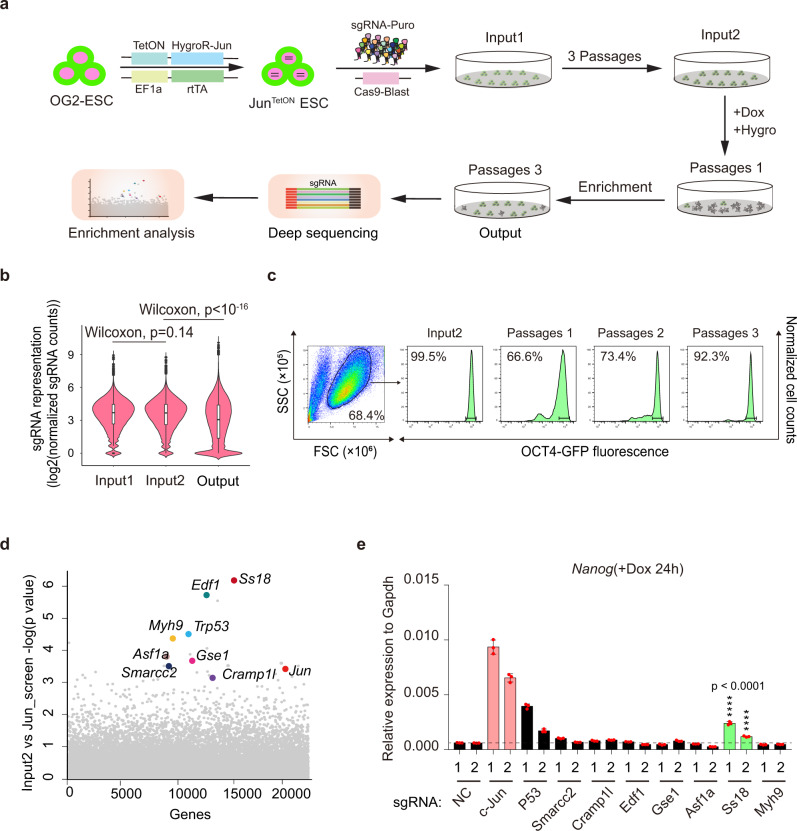

We hypothesize that cJUN accomplishes this rapid PST by cooperating with a cellular machinery critical to cell fate transitions. To gain insight into such machinery, we design a CRISPR based screening system as illustrated (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1h). The rationale behind this design is our prediction that any colonies become resistant to cJUN induced PST must harbor a guide RNA targeting a critical component of this machinery (Fig. 1a). We first performed quality control tests to assure proper execution of the screens (Fig. 1b, c, Supplementary Fig. 1i). We then performed the screen as illustrated and identified multiple hits (Fig. 1d). Among the hits, SS18 scored high (Fig. 1d) and can be validated by knockout experiments with the corresponding sgRNA sequences (Fig. 1e) as measured by Nanog expression during cJUN induced PST. Interestingly, p53 appears to play a role in PST, in addition to Ss18 (Fig. 1e). We then performed a second screen and identified similar hits plus Brg1 (also known as Smarca4) (Supplementary Fig. 1j). Since both SS18 and BRG1 are subunits of the BAF complex28, we decided to focus on SS18 for further analysis.

Fig. 1. Genome-wide screen for factors regulating PST.

a The workflow for GeCKO screening strategy by HygroR-JunTetON OG2ES. TetON cell line was successively infected with viruses expressing Cas9 and sgRNA. Dox and hygromycin were added after three cell passages. Dox and hygromycin were removed in 24 h and 48 h, respectively. Cells that survived after three passages were collected and analyzed. Hygro, hygromycin; HygroR, hygromycin resistance gene; GeCKO: Genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 knockout. b Violin plot showing the distribution of sgRNA frequencies at different stages of screen. The distribution of sgRNA library was significantly polarized after the screening (output) compared to input 1 and input 2. Two-sided Wilcoxon test adjusted for multiple comparisons. n = 65959 sgRNAs. Input 1, Minimum 0, 25%Percentile 2.672, Median 3.693, 75%Percentile 4.452, Maximum 8.934; Input 2, Minimum 0, 25%Percentile 2.611, Median 3.672, 75%Percentile 4.456, Maximum 8.764; Output, Minimum 0, 25%Percentile 1.366, Median 3.064, 75%Percentile 4.391, Maximum 10.07. Two independent experiments. c Distribution of OG2-GFP signaling at different passages by FACS during this screening. d Identification of top candidate genes using the MAGeCK43 algorithm. e Validation of the hits in (d) by corresponding sgRNAs within GeCKO library during c-JUN induced PST. Data are mean ± s.d., two-sided, unpaired t test; n = 3 independent experiments, ****p < 0.0001.

SS18 regulates cJUN-induced PST

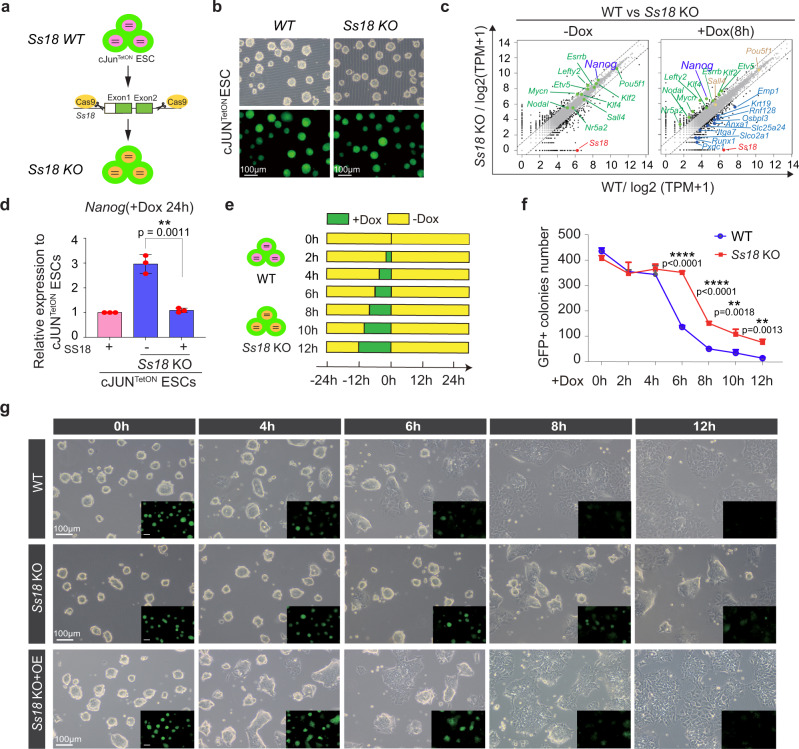

Unlike p5329, Ss18 has not been reported to be involved in pluripotency nor mESC differentiation. To probe its likely function, we generated Ss18−/− mESCs as illustrated in Fig. 2a. We obtained KO cell lines (Fig. 2b) that can be confirmed by western blotting for SS18 protein (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Ss18−/− mESCs are morphologically identical to their wild type counterparts (Fig. 2b) and express similar naive genes under naive conditions (Fig. 2c, left panel). When induced to undergo PST, Ss18−/− mESCs are resistant to cJUN induced PST with substantial cells maintaining Nanog expression at 8 h (Fig. 2c, right panel; Supplementary Fig. 2b). Over-expression of SS18 in Ss18−/− cells can rescue the defect as measured by Nanog expression (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Fig. 2c) or morphology/GFP expression (Fig. 2g). At 6 h post induction, ~90% Ss18−/− colonies remain pluripotent morphologically, while only 30% wild type ESCs can do so (Fig. 2e–g, Supplementary Fig. 2d). Taken together, these results demonstrate that SS18 deficiency confers resistance to cJUN induced PST. We further validated the role of SS18 in other differentiation systems (Supplementary Fig. 2e), such as spontaneous differentiation, naïve-primed differentiation and neuroectodermal differentiation, and show that the deficiency of SS18 delays all these differentiation processes as measured by Nanog/Esrrb/Klf4 expression (Supplementary Fig. 2f) or morphology (Supplementary Fig. 2g).

Fig. 2. SS18 Regulates cJUN-induced PST.

a Construct design for SS18 knockout in mESC. The cleavage sites of Cas9 were designed flanking exon1 and exon2 within Ss18 loci. b SS18KO mESCs are similar to WT ones in morphology. Three biological replicates. c Gene expression profiles by RNA-seq for WT and SS18 KO mESCs. SS18 knockout has little impact on most pluripotent genes but delays the c-JUN induced PST process significantly. d Rescue of the delayed PST as indicated by Nanog expression in SS18 KO mESCs with SS18 in lentiviral vector. Data are mean ± s.d., two-sided, unpaired t test; n = 3 independent experiments, **p < 0.01. e The experimental design to test the window of sensitivity for SS18 response to c-Jun-induced PST. f Results from (e) to show that OCT4-GFP positive colony numbers recovered for 48 h in 2i/LIF medium after c-Jun induction at the indicated time points for wild type and SS18 KO ESCs. Data are mean ± s.d., two-sided, unpaired t test; n = 3 independent experiments. **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001. Note no change for 4 h and the greatest change at 6 h for the window of sensitivity. g Representative images for the c-Jun-induced PST in WT, Ss18−/− and Ss18−/− overexpressing Ss18, respectively. Three biological replicates.

SS18 forms condensates in nuclei

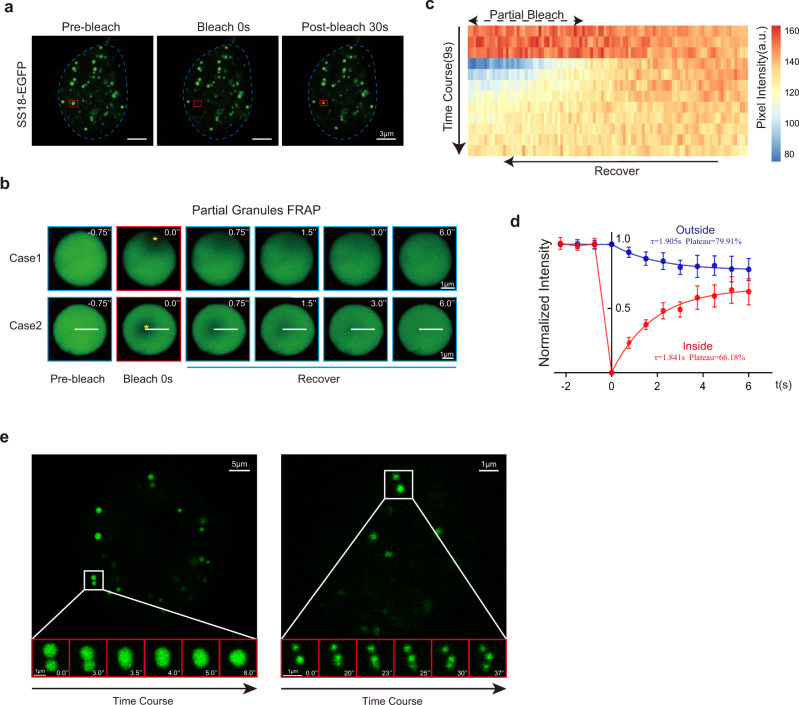

To probe the potential mechanisms associated with SS18 mediated PST, we carried out immunostaining experiments and show that endogenous SS18 forms punctate condensates during PST (Supplementary Fig. 3a). To help visualize SS18, we tagged it with EGFP and show that SS18-EGFP forms condensates readily when expressed in mESCs. We then analyzed the response of the condensates to 3% 1,6-hexanediol, an aliphatic alcohol which could disrupt weak hydrophobic interactions specifically30 and show that it can effectively disperse SS18-GFP condensates in 10 s, and more than half of the condensates recover after 1,6-hexanediol removal in 10 s (Supplementary Fig. 3b, c). To characterize the condensates in more detail, we performed FRAP experiments, and show that SS18-EGFP condensates recover rapidly in ~10 s after bleaching (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 3d). We further bleached the SS18-GFP condensates in the edge (Case1) or middle (Case 2) and observed a quick florescence recovery within 6 s in both conditions (Fig. 3b). When we measured the pixel intensity along the white line in case 2, we can show a clear recovery in kymography (Fig. 3c). We then quantified the mobility of SS18 protein by measuring the pixel intensity during fluorescence recovery inside or outside of eight bleached regions within condensates, and show that τ(inside) = 1.841 s, τ(outside) = 1.905 s; Plateau(inside) = 66.18%, Plateau(outside) = 79.91% (Fig. 3d), suggesting a quick movement of SS18 in the condensates. Moreover, the condensates appear to be able to divide or fuse quite rapidly as well (Fig. 3e). We further performed quantitative analysis of fusion and fission events for the condensates in cells (Supplementary Fig. 3e) and show that the time scale for SS18-EGFP condensate fusion increases almost linearly with their diameters, resulting a fitting slope K = 0.65 ± 0.19. These data suggest that SS18 forms liquid-like condensates readily31.

Fig. 3. SS18 forms condensates.

a Representative images of FRAP experiments with lentiviral SS18-EGFP expressed in mESCs. The droplet undergone bleaching was indicated in the red box. The blue dotted line represents the nuclear boundary. Scale bars,3 μm. laser intensity 2.5%, detector gain 500 V, background subtraction treatment. Seven condensates from two independent experiments. b Time course microscopy images of fluorescence recovery in SS18-EGFP condensates after partial photobleaching at the edge (case 1) and middle (case 2). SS18-EGFP was expressed by transient transfection in 293 cells to obtain the large enough condensates. The bleached regions were marked by yellow asterisks. Scale bars, 1 μm. laser intensity 2.5%, detector gain 500 V, background subtraction treatment. Eight condensates from two independent experiments. c Kymography for the time course of pixel intensity along the white line in the condensate of case 2 in (b). The intensity recovered in the bleached region inside the condensate as the unbleached part decreased. Pixel number = 103. d The intensity dynamics inside and outside of the bleached regions within condensates (n = 8) was fit to an exponential function. t = 0 was the bleached time point. τ(inside) = 1.841 s, τ(outside) = 1.905 s; Plateau(inside) = 66.18%, Plateau(outside) = 79.91%, diffusion coefficient on the order of D ~ L2/τ ~5 μm2/s, L is the diameter of the bleached region. Data are mean ± s.d., two-sided, unpaired t test; n = 8 condensates. e Representative droplet fusion events are shown by time course images. SS18-EGFP was expressed by transient transfection to obtain the large condensates as in (b). Scale bars, 2 μm. laser intensity 2.5%, detector gain 500 V, background subtraction treatment. Nine fusion/fission cases.

SS18 has IDRs critical for its activity

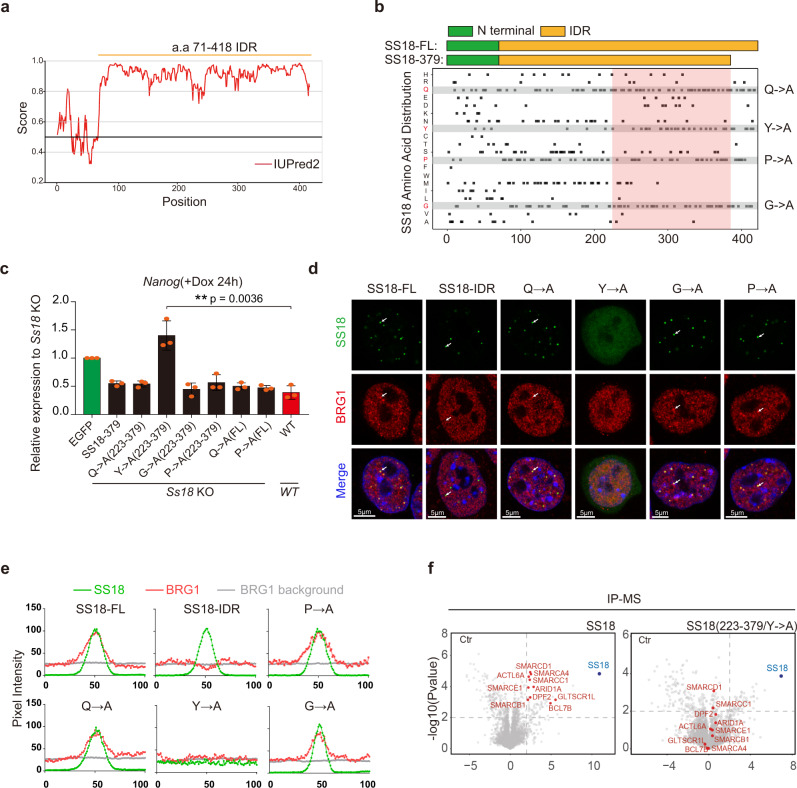

Proteins that undergo liquid-liquid phase separation to form punctate condensates as we described for SS18 often contain IDR or Intrinsically Disordered Region30,32–35. To test if SS18 has similar IDR, we analyzed amino acid sequence of SS18, and show that except the first 70 residues at the N terminus, the rest 71-418 residue domain have a strong IDR (Fig. 4a). We then constructed a series of mutants for the IDR (Supplementary Fig. 4a), confirming their expression by western blot (Supplementary Fig. 4b), and show that its ability to rescue Ss18−/− mESCs is dependent on the length of IDR left in the mutants (Supplementary Fig. 4c). Based on the rescue activities, we reason that IDR223-379 may be most critical (pink box in Fig. 4b). This sub region appears to be enriched with Q, Y, P and G (Fig. 4b). We then constructed four mutants, Q-A, Y-A, P-A and G-A by substituting each of those residues with A (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. 4d). Among them, Y-A mutant lost its ability to form condensates, while the other three mutants appear to be retaining the ability to form condensates, compared to the WT SS18 or the truncated form SS18-IDR (Fig. 4c, d, Supplementary Fig. 4e–g). Importantly, we show that this Y-A mutant fails to rescue Ss18−/− mESCs in PST (Fig. 4c). We further investigated the co-localization of SS18 or mutants with BRG1 by immunostaining and pixel intensity analysis, and show that except Y-A mutant, all the other three mutants can colocalize with BRG1 in the same condensates (Fig. 4d, e). Surprisingly, we find that SS18-IDR (71-418) is sufficient to form condensates, but unable to colocalize with BRG1 (Fig. 4d, e), suggesting that the N-terminal residues are not required for condensates formation, but critical for recruiting BRG1. We further performed IP-MS experiments to investigate whether the SS18 Y-A mutant can pull down the components in BAF complex (Supplementary Fig. 4h) and show that Y-A mutant lost the capability to interact with BAF subunits (Fig. 4f). Taking together, these results suggest that SS18 contains a Y-type IDR required for BRG1 interaction and PST.

Fig. 4. SS18 condensates through a tyrosine-based mechanism.

a Graph plotting intrinsic disorder of SS18 by the IUPred2A algorithm (https://iupred2a.elte.hu/). IUPred2 scores are shown on the y axis, and the amino acid positions are shown on the x axis. b Schematic illustration for Ss18 truncations shown in the upper panel with the amino acid distribution of SS18 indicated in the lower panel. The pink box highlights the necessary region of C-terminal for the function of SS18 in PST. Q->A, Y->A, P->A, G->A indicate the amino acid Glutamine, Tyrosine, Proline, Glycine mutated to Alanine, respectively. c The expression of Nanog in Ss18−/− mESCs overexpressing the indicated Ss18 mutants during c-Jun based PST. Note the failure of Y-A to rescue PST. Data are mean ± s.d., two-sided, unpaired t test; n = 3 independent experiments, **p < 0.01. d Representative images for the indicated WT, IDR and SS18-mutant-EGFP fusion proteins and immunofluorescence imaging for BRG1 in mESCs. Scale bars, 5 μm. Note the failure of Y-A mutant to form condensates. SS18-EGFP, laser intensity 2.5%, detector gain 500 V. BRG1 immunofluorescence, laser intensity 3.5%, detector gain 750 V. Both SS18-EGFP and BRG1 immunofluorescence were processed by background subtraction. Eight condensates. e The graphs showing the pixel intensity in Fig. 4d. The green curves indicate the pixel intensity dynamic across six condensates of various SS18 mutants and the corresponding pixel intensity of BRG1 indicated by the red curves; the average pixel intensity of BRG1 within nuclei and outside of the nucleoli were indicated by gray curves. f Volcano plots of IP-MS results for FLAG tagged SS18 and SS18Y-A mutant expressed in SS18−/− mESCs by anti-Flag antibody with label-free quantification. SS18−/− cells serves as control. Every point represents a single protein. SS18 and BAF components are marked blue and red. IP-MS experiments were performed in triplicates and a two-sample t test was applied. P = 0.01 and fold change = 2 are used as threshold.

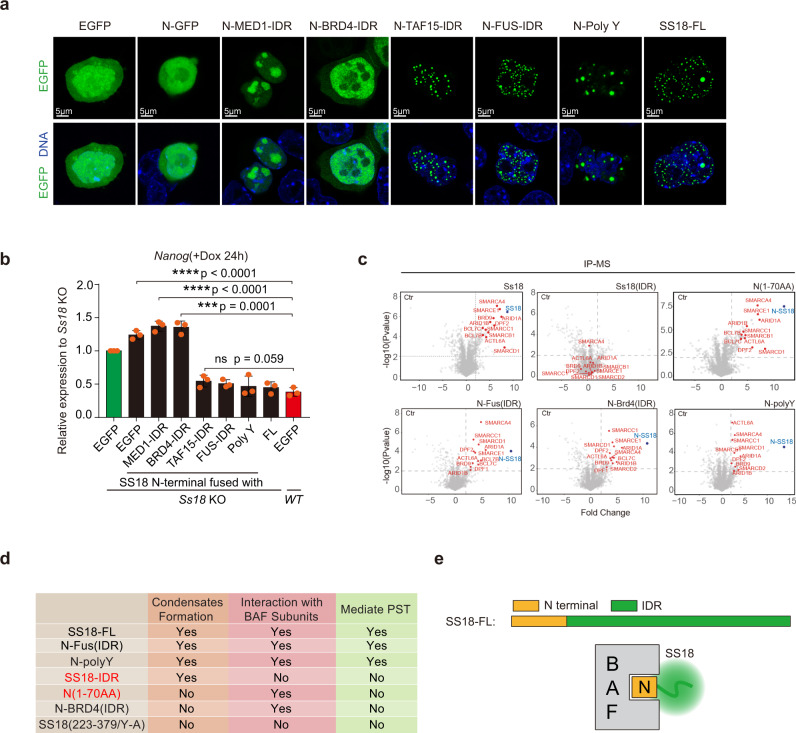

Functional rescue of SS18 IDR

Condensate formation through phase separation is a physic property mediated by several distinct mechanisms34,35. Our results from the Y-A mutant further suggest that SS18 may rely on Y residues to form condensates (Fig. 4d). To test if SS18 IDR can be replaced by other types of IDRs, we constructed a set of fusions between the N-terminal domain of SS18 and poly-Y, S centered/enriched IDRs from MED1 and P/Q enriched IDRs from BRD432, Y centered/enriched IDRs from TAF15 and FUS33 (Supplementary Fig. 5a). We show that poly-Y, TAF15-IDR and FUS-IDR, but not MED1-IDR nor BRD4-IDR, can rescue condensates formation (Fig. 5a). Consistently, poly-Y, TAF15- and FUS- PLDs can functionally replace SS18-IDR in rescuing SS18−/− defect during cJUN-based PST (Fig. 5b). We further performed IP-MS experiments to investigate whether these SS18 truncation/fusions can pull down the subunits in BAF complex (Supplementary Fig. 5b), and show by pairwise comparison scatterplots that SS18 N-terminal, N-polyY and N-FUS(IDR) can pull down the subunits of BAF complex while SS18(IDR) could not (Fig. 5c). Notably, we show that N-BRD4 could pull down the subunits in BAF complex, but still fails to mediate PST (Fig. 5b, c), perhaps due to the type of condensates formed (Fig. 5a). We summarize the results into a table in Fig. 5d and show that SS18 mediates PST by forming BAF complex through its N-70 domain and condensates with a C-terminal IDR (Fig. 5e). These results further suggest that IDRs are interchangeable among the Y-type ones and can be designed artificially like the poly-Y.

Fig. 5. SS18 interacts with BAF through its N-terminal 70 residues.

a Representative images for EGFP fusions expressed in mESCs as indicated. Note the similar condensates formed by SS18, FUS and TAF IDRs as compared to those for MED1 and BRD4. Poly Y is an artificial 24 tyrosine residue polypeptide. FL full length. Scale bars, 5 μm. laser intensity 2.5%, detector gain 500 V, background subtraction treatment. Three biological replicates. b Rescue of Ss18KO by constructs in (a) to show that IDRs from TAF and FUS or even polyY can substitute that of SS18. Data are mean ± s.d., two-sided, unpaired t test; n = 3 independent experiments, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. c Volcano plots of IP-MS results from flag tagged Ss18-FL, SS18(IDR), N terminal 70aa of Ss18 alone or fused with IDRs from FUS or Brd4 and polyY expressed in Ss18KO mESCs by Flag antibody with label-free quantification. Every point represents a single protein. SS18 and BAF components are marked in blue and red, respectively. IP-MS experiments were performed in triplicates and a two-sample t test was applied. P = 0.01 and fold change = 2 were used as threshold. d Summary table for various constructs for their abilities to condensate, interact with BAF and mediate PST. e A proposed structure and function relationship for SS18: N-terminal BAF interacting domain or BID and C-terminal condensate forming IDR domain (CFD).

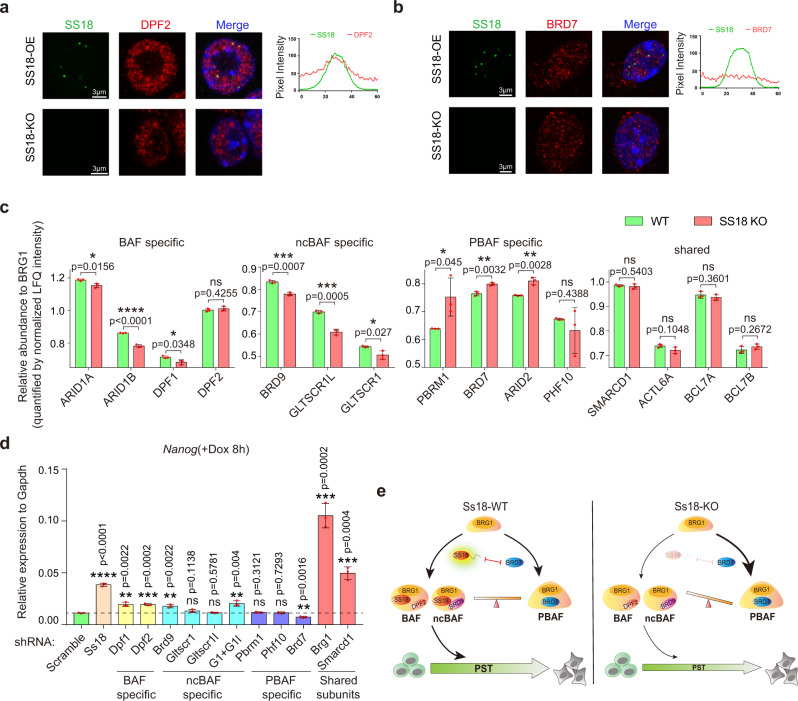

SS18 promotes BAF/ncBAF but impedes PBAF assembly during PST

mSWI/SNF ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes have three subtypes that share many core subunits such as BRG1, SMARCD1, ACTL6A and BCL7A/B/C, but differ in specific ones, i.e., the canonical BAF with DPF1, DPF2, ARID1A, and ARID1B, the PBAF (Polybromo-associated BAF) with PBRM1, PHF10, ARID2 and BRD7 and the recently reported ncBAF (non-canonical BAF) containing BRD9, GLTSCR1/1 L. Among them, SS18 is involved in the assembly of BAF and ncBAF (Supplementary Fig. 6a)20,36,37.

To investigate condensates associated with SS18, we stained SS18KO mESCs expressing SS18-GFP with antibodies against endogenous BAF specific subunit DPF2 or PBAF specific subunit BRD7 and show that DPF2, not BRD7, is enriched with SS18 (Fig. 6a, b, Supplementary Fig. 6b), which is also consistent with endogenous SS18 (Supplementary Fig. 6c, d, e). These results demonstrate that SS18 is associated exclusively with BAF, not PBAF, in mESCs.

Fig. 6. SS18 regulates PST through mediating the assembly balance among BAF ncBAF and PBAF.

a Representative images of immunofluorescence for endogenous BAF specific subunit DPF2 in SS18KO mESCs infected with lentiviral SS18-EGFP. The graph on the right shows pixel intensity across five condensates of SS18-EGFP (green) and DPF2 (red). Scale bars, 3 μm. SS18-EGFP, laser intensity 2.5%, detector gain 500 V. DPF2 immunofluorescence, laser intensity 3.5%, detector gain 750 V. Both SS18-EGFP and DPF2 immunofluorescence were processed by background subtraction. Three independent experiments. b Representative images of the immunofluorescence for endogenous PBAF specific subunit BRD7 in SS18KO mESCs with exogenous SS18-EGFP. The graph on the right shows pixel intensity across five condensates of SS18-EGFP and BRD7 (red). Note no co-localization between SS18 and BRD7. Scale bars, 3 μm. SS18-EGFP, laser intensity 2.5%, detector gain 500 V. BRD7 immunofluorescence, laser intensity 3.5%, detector gain 750 V. Both SS18-EGFP and BRD7 immunofluorescence were processed by background subtraction. Three independent experiments. c The histogram shows the relative precipitated abundance of indicated proteins to BRG1 as quantified by normalized LFQ intensity from IP-MS experiments by anti-BRG1 antibody performed on WT and SS18KO mESCs. IP-MS experiments were performed in triplicates and a two-sample t test was applied. Data are mean ± s.d., two-sided, unpaired t test; n = 3 independent experiments, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. d The expression levels of Nanog by Jun-FlagTetON mESCs at 8 h during PST with knocking down of indicated components of BAF ncBAF or PBAF. G1 + G1l, knockdown Gltscr1 and Gltscr1l jointly. Data are mean ± s.d., two -sided, unpaired t test; n = 3 independent experiments, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. e A working model for SS18-mediated PST. SS18 functions by interacting with BAF or ncBAF subunits through its N-terminal 70aa, and forming condensates through a tyrosine-rich IDR. Meanwhile, the full length of SS18, co-localizing with BAF-specific component and isolating PBAF-specific one, can promote the BAF complex assembly and impair that of PBAF. In WT cells, BAF ncBAF and PBAF reach a balance. In SS18KO cells, the balance shifts towards PBAF to cause a delay in PST.

To test the role of SS18 in BAF assembly, we immunoprecipitated the common subunit BRG1 in SS18 WT and SS18 KO mESCs and then analyzed the complexes by IP-MS to detect the relative abundance of each components. We found SS18 deficiency decreases the assembly of canonical BAF and ncBAF, but promotes that of PBAF (Fig. 6c). In addition, the full length not N terminal of SS18 can rescue BAF assembly in SS18 KO mESCs (Supplementary Fig. 7a, b). Given the two unbiased screens we performed that identified both SS18 and Brg1 but no PBAF specific subunits, we speculate that PST relies on primarily BAF or/and ncBAF, not PBAF. We indeed can show that BAF ncBAF and PBAF serve different roles in PST by shRNA knockdown of BAF/ncBAF/PBAF specific subunits and shared ones (Fig. 6d, Supplementary Fig. 7c, Supplementary Data 2). The depletion of BAF specific components, DPF1/2, and ncBAF specific ones can delay this transition, while depleting PBAF specific subunit BRD7 promotes PST (Fig. 6d). Unlike Ss18, Brg1 knockdown in mESCs leads to defects in self-renewal and survival morphologically (Supplementary Fig. 7d), consistent with a previous report22–24. We further performed RNA-Seq experiments to investigate the downstream targets of Brg1 in mESC, and show by GO analysis that the 572 genes affected by Brg1 knockdown are involved in cell-substrate adhesion, positive regulation of cell migration and epithelial cell development (Supplementary Fig. 7e). However, BRD9 inhibitor BI-9564 has no effect in the process (Supplementary Fig. 7f). We knocked down the specific components of ncBAF and PBAF in SS18 KO mESCs and found the deficiency of ncBAF will delay PST further, on the contrary, the knockdown of PBAF will rescue that (Supplementary Fig. 7g), which suggests that BAF and ncBAF play similar/redundant roles against PBAF in cJUN induced PST.

To further investigate the mechanism underlying the different effects between BAF and PBAF within PST, we performed ChIP-seq of H3K27ac, cJUN, SS18, and PBAF specific subunits PBRM1 and BRD7 at different time points during PST (Supplementary Fig. 7h). All the H3K27ac occupancy sites ± 5 kb of 0 h and 8 h are divided into three categories (8 h down, permanent and 8 h up) according to the dynamic changes of intensity by fold change >2. Both BAF and PBAF complexes relocate to the same sites occupied by cJUN. We can estimate the relocation rate from the ratio of average intensity of up sites and down sites from the graph. Contrary to PBAF subunits, SS18 has higher relocation rate at 4 h and 8 h during PST (Supplementary Fig. 7h), suggesting that BAF containing SS18, compared with PBAF, can facilitate cell fate transition more efficiently. Taken together, these data suggest that SS18 promotes BAF but inhibits PBAF assembly to mediate PST (Fig. 6e).

Discussion

Broadly speaking, the mammalian cell fate continuum can be divided into two categories: pluripotent and somatic. Pluripotent cells have the capacity to give rise to all somatic cells9. On the other hand, somatic cells can be reprogrammed to a pluripotent state38–40. The inter-conversion between somatic and pluripotent cells through differentiation and reprogramming suggests that there may be an interface between somatic and pluripotent states. We have proposed previously that cJUN serves as a guardian of somatic fate as opposed to factors such as Oct4 that specify the pluripotent fate27. In this report, we further define a molecular link at the pluripotent-somatic interface. Mechanistically, we propose that cJUN drives a rapid transition through this interface with the help of SS18, a well-known member of the BAF complex. We provided evidence that SS18 is a bipartite protein with an N-terminal 70aa domain specific for BAF interaction and a C-terminal IDR for forming condensate through a unique tyrosine-based mechanism.

It is of interest to note that the IDR of SS18 can be replaced by similar IDRs from FUS and TAF1533, but not BRD4 and MED132 (Fig. 5b). We noted that the IDRs of FUS and TAF15, like that of SS18, are enriched with tyrosine residues, while those of BRD4 and MED1 are not (Supplementary Fig. 5a). Based on these observations, we further reasoned that perhaps a polymer of tyrosine residues can also function as an IDR to form condensates. Indeed, when we replaced the IDR of SS18 with a 24-tyrosine residue polypeptide, similar condensates can be also observed (Fig. 5A, N-Poly Y). This construct can also rescue full length SS18 function in PST assays (Fig. 5b). Based on these results, we would like to propose that the 24-residue polymer can serve as a model tool to further analyze liquid-liquid phase separation or condensate formation in vitro and in vivo. The simple composition as well as well-behaved pattern of condensates may help further illuminate principles and rules associated with phase separation. More generally, it may be possible to design additional polymers that behave similarly to other classes of IDRs such as those from BRD4 or MED1.

Chromosome translocation t(X;18) (p11.2; q11.2) has been suggested as a cause of synovial sarcoma28. Our dissection of its structure into two main domains, i.e., the N-terminal BAF interacting domain and the C-terminal IDR, may further encourage innovative strategies to design targeted therapies.

Methods

Cell culture

HEK293T cells are cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, GlutaMAX and NEAA. Mouse ESCs are maintained under feeder-free condition with mESC-2i/LIF medium containing DMEM, 15% FBS, NEAA, GlutaMAX, PD0325901 (Targetmol T6189), Chir99021 (Targetmol T2310), LIF (Millipore ESGE107). HEK293T was obtained from ATCC (CRL-1126). mESCs were derived in-house by crossing Oct-GFP trans genetic allele carrying male mice (male CBA/cAJ x female C57bl/6 J) and female 129/Sv mice. All the cell lines have been confirmed as mycoplasma free with Lonza LT07-318. For random differentiation, mouse ESCs were dissociated and plated at 2 × 104/cm2 in mESC medium without LIF and analyzed after 24 h incubation. For Naïve-Primed differentiation, mouse ESCs were dissociated and plated at 2 × 104/cm2 in mESC-2i/LIF medium. After 24 h medium was replaced with FA medium (50% DMEM/F12 (GIBCO), 50% Neurobasal (GIBCO), 0.5× N-2 (GIBCO), 0.5× B-27 (GIBCO), 1% GlutaMAX (GIBCO), 1% non-essential amino acids (GIBCO), 1% sodium pyruvate (GIBCO), 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (GIBCO), 15 ng/ml bFGF (PeproTech), 20 ng/ml Activin A (PeproTech) and 1 μM XAV939 (Selleck S1180)) for a further 24 h prior to analysis. For neuroectodermal differentiation, mouse ESCs were dissociated and plated onto 0.2% gelatin-coated plastic at a density of 2 × 104/cm2 in N2B27 medium (50% DMEM/F12 (GIBCO), 50% Neurobasal (GIBCO), 0.5× N-2 (GIBCO), 0.5× B-27 (GIBCO), 1% GlutaMAX (GIBCO), 1% non-essential amino acids (GIBCO), 1% sodium pyruvate (GIBCO) and 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (GIBCO)) and analyzed after 24 h incubation.

Gene knockout in mESCs

Knockout mouse ESCs lines were generated using the CRISPR/Cas9 system41,42. Guide RNAs were designed using crispr.mit.edu. and cloned downstream of the human U6 promoter of pX330 (Addgene). For SS18 KO in mouse ESCs, two pairs of Guide RNAs were designed for each gene to delete critical exons. For Ss18, the gene locus of exon1 to exon2 were deleted. Mouse ESCs clones carrying deletions in both alleles were identified by genotyping and western blot.

Immunoblotting

Cells were collected and lysed in lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) on ice for 15 min, and then cells were boiled in 100 °C for 10 min. After centrifugation, the cell supernatants were subjected to SDS–PAGE and incubated with corresponding primary antibody and secondary antibodies. The following antibodies were used in the project: anti-SS18 (CST no. 21792. 1:1000), anti-EGFP (CST no. 2555 s, 1:1000), anti-GAPDH (KangChen Bio-tech, no. KC-5G5, 1:1000), anti-JUN (abcam, no. ab31419, 1:1000), anti-BAF155 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, no. sc-32763, 1:500).

Immunofluorescence

Cells growing on coverslips were washed three times with PBS, then fixed with 4% PFA for 30 min, and subsequently penetrated and blocked with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 3% BSA for 30 min at room temperature. Then, the cells were incubated with primary antibody for half hour. After five washes in PBS, 1 h of incubation in secondary antibodies, cells were then incubated in DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich D9542) for 2 min. Then, the coverslips were mounted on the slides for observation on the confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 900 with Airyscan detector). The following antibodies were used in this project: anti-SS18, (CST no. 21792. 1:1000). anti-BRG1, (CST no. 52251 1:1000). anti-DPF2, (Proteintech, no. 12111-1-AP-50 μl,1:100). anti-BRD7, (Proteintech, no.51009-2-AP-50 μl, 1:100).

qRT–PCR and RNA-seq

Total RNAs were prepared with TRIzol. For quantitative PCR, cDNAs were synthesized with ReverTra Ace (Toyobo) and oligo-dT (Takara), and then analysed by qPCR with ChamQ SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme). The qRT-PCR primers used in this study are provided in Supplementary Data 1. VAHTS mRNA-seq V3 Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NR611, Vazyme) was used for library constructions and sequencing done with NextSeq500 Mid output 150 cycles (FC-404-2001, Illumina) for RNA-seq. RNA-seq data was analyzed by DEseq2, GO.db and Mfuzz.

Genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 screens

The lentiviral gRNA plasmid library and CRISPR/Cas9 expressing plasmid for genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 screen were obtained from Addgene (#1000000053). Amplification of the library and preparation of the lentivirus were performed following the protocol provided by Addgene with electrocompetent E. coli (TaKaRa). HygroR-cJunTetONESCs stably expressing Cas9 were seeded in the 15-cm dishes (about 3 × 106 cells per dish) and a total of 2.5 × 107 cells were infected with the gRNA lentivirus library to keep the diversity of library. Meanwhile, the MOI of infection was <0.3. Puromycin (1 µg/ml GIBCO A1113802) was used to eliminate non-infected cells after 48 h. The infected cells were collected as the sample of input 1 and the cells of further three passages were collected as the sample of input 2. Next, 2 µg/ml doxycycline was used to trigger the expression of HygroR-cJun fusion protein and 10 µg/ml hygromycin was added in the culture medium to eliminate the cells without response to doxycycline. Dox was added only for the first 24 h at passage1 to drive PST but withdrew in the following three passages. The GFP positive cells were analyzed by FACS when passed in 24 h after Dox withdrawal. Almost all the cells would have transitioned from pluripotency to somatic state. The cells resisting PST or apoptosis were enriched for three passages in mESC medium, while the rest ones were eliminated gradually. Finally, the enriched cells were collected as the sample of output group.

Illumina sequencing of gRNAs and statistical analysis

The genomic DNA of the three samples (input 1, 2 and output group) were extracted and the Illumina sequencing of gRNAs were conducted as described previously26. The counts of unique sgRNA for a given sample were normalized as follows:

| 1 |

Enrichment and depletion of guides and genes were analysed using MAGeCK statistical package543 by comparing read counts between input 2 and input 1 or output group and input 2.

FACS analysis

For OCT4-GFP analysis in the process of screen, cells were suspended in DPBS supplemented with 2% FBS (FACS buffer) for direct detection. DAPI was used to exclude the nonviable cells. The cells were then analyzed on Accuri C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). The GFP fluorescence intensity was detected in the FITC channel. Data analysis was done using FlowJo7.6.1. software (LLC).

ChIP-Seq

Briefly, cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min and then followed by the reaction with 0.125 M glycine. Cells were then lysed in ChIP-buffer A (50 mM HEPES-KOH, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 10% glycerol, 0.5% NP-40, 0.25% Triton X-100, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and protease inhibitor cocktail) for 10 min at 4 °C. Samples were centrifuged at 1400 g for 5 min at 4 °C. Pellets were lysed in ChIP-buffer B (1% SDS, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10 mM EDTA and protease inhibitor cocktail) for 5 min at 4 °C. The DNA was fragmented to 100–500 bp by sonication, and then centrifuged at 12,000 g for 2 min. The supernatant was diluted with ChIP IP buffer (0.01% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl and protease inhibitor cocktail). Immunoprecipitation was performed with 1 µg anti-H3K27ac antibody (Abcam, ab4729) coupled to Dynabeads with proteinA/G overnight at 4 °C. Beads were washed, eluted and reverse crosslinked. DNA was extracted by phenol/chloroform for sequencing. The ChIP DNA library was constructed following the Illumina ChIP-seq library generation protocol. Briefly, 5 ng ChIP DNA was blunt-ended, and then a dA tail was added. Illumina genomic adapters with index sequences were ligated to the DNA. The adapter-ligated DNA was amplified by PCR for 18 cycles, and the resulting DNA libraries were quantified and tested by qPCR with positive primers to assess the quality of the library. The ChIP DNA library for NextSeq 500 sequencing was constructed with VAHTS Turbo DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (Vazyme) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The ChIP-seq for other factors in mESCs was constructed with NovoNGS CUT&Tag 2.0 High-Sensitivity Kit for Illumina (novoprotein N259-YH01) according to manufacturer’s instructions. ChIP-seq data are mapped to the 10 mm mouse genome assembly using bowtie2, version 2.4.1.

SS18 endogenous immunoprecipitation and on-bead digestion

Whole cell extracts of mES cells with cJun overexpression were prepared using lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 10% Glycerol, 0.5% NP40) with fresh added 1x Complete Protease inhibitors (Sigma, 1187358001). Cells were incubated for 2 h at 4 °C on a rotation wheel. Soluble cell lysates were collected after maximum speed centrifugation at 4 °C for 15 min. 1 mg of cell lysates were incubated with either SS18 antibody or matched IgG overnight at 4 °C on a rotation wheel. Combined Protein A/G magnetic beads (Bio-rad, 1614833) were added for another 1.5 h. Beads were then washed three times with wash cell lysis buffer and one time with PBS. After completely removal of PBS, immunoprecipitated proteins were digested using on-bead digestion protocol as described before 17. Briefly, beads were incubated with 100 mL of elution buffer (2 M urea, 10 mM DTT and 100 mM Tris pH 8.5) for 20 min. Afterwards, iodoacetamide (Sigma, I1149) was added to a final concentration of 50 mM for a 10 min in the dark, following with 250 ng of trypsin (Promega, V5280) partially digestion for 2 hr. After incubation, the supernatant was collected in a separate tube. The beads were then incubated with 100 mL of elution buffer for another 5 min, and the supernatant was collected in the same tube. All these steps were performed at RT in a thermo shaker at 500 g. Combined elutes were digested with 100 ng of trypsin overnight at RT. Finally, tryptic peptides were acidified to pH < 2 by adding 10 mL of 10% TFA (Sigma, 1002641000) and desalted using C18 Stage tips (Sigma, 66883-U) prior to MS analyses. Each experiment was performed in technical triplicate.

Mass spectrometry analysis

Tryptic peptides were separated by AcclaimTM PepMapTM 100 C18 column (Thermo, 164941) using a 140 min of total data collection (100 min of 2–22%, 20 min 22–28% and 12 min of 28–36% gradient of B buffer (80% acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid in H2O) for peptide separation, following with two steps washes: 2 min of 36–100% and 6 min of 100% B buffer) with an Easy-nLC 1200 connected online to a Fusion Lumos mass spectrometer (Thermo). Scans were collected in data-dependent top-speed mode with dynamic exclusion at 90 s. Raw data were analyzed using MaxQuant version 1.6.0.1 search against Mouse Fasta database, with label free quantification and match between runs functions enabled. The output protein group was analyzed and visualized using DEP package as described before44.

Statistical information

Data are presented as mean ± s.d. as indicated in the figure legends. Unpaired two-tailed student t test, The P value was calculated with the Prism 6 software. A P < 0.05 was considered as statistically, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. The experiments were not randomized. The investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiment and outcome assessment.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by National Natural Science Foundation of China (31830060, 32022019, U20A2013, 31530038, 31770889, 31801180); the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFA0504100, 2018YFE0204800, 2017YFA0105001, 2018YFA0108700) “Strategic Priority Research Program” of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA16010505), Key Research Program of Frontier Sciences of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (QYZDJ-SSW-SMC009), Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province (2017B030314056, 2018B030306047) Guangzhou Regenerative Medicine and Health Guangdong Laboratory project (2018GZR110104003, 2018GZR110105012). We would like to thank Liman Guo from Metabolomics and Proteomics Center, Bioland Laboratory for proteomics measurements. The authors also are grateful for the support from the Guangzhou Branch of the Supercomputing Center of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. All the animal experiments were performed with the approval and according to the guidelines of the animal care and use committee of the Guangzhou Institutes of Biomedicine and Health.

Source data

Author contributions

J.L. and J.K. designed the project; J.K. set up the CRISPR/cas9 screening system and phase separate analysis; J.K., C.W., S.Y., Z.Z., J.G., and W.L. performed the screening experiments, Z.Z., Z.C., W.L., Y.Q. and S.C. performed the RNA-seq experiments; W.G., Z.Z., performed FRAP experiments. P.L. and Z.Z. constructed the plasmids. T.Y. provided glial cells. J.K., C.B., Z.W., B.W., and X.L. performed the ChIP-seq experiments; R.S., D.L., and X.Z. performed the IP-MS experiments, J.K., Y.Y., S.X., J.H., J.C., and G.Z. analyzed the data; J.L. and D.P. supervised the whole study, conceived the whole study, wrote the paper, and approved the final version.

Data availability

The RNA-Seq, ChIP-seq data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database under the accession code GSE135451. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the iProX partner repository45 with the dataset identifier PXD026208. Source data are provided with this paper. The source data underlying Figs. 1e, 2d, f, 3c, d, 4c, 5b,6c, d and Supplementary Figs. 1d, g, 2b, d, f, 3c–e, 4c, e–g, 6e, 7b, c, f, g are provided as a Source Data file. Supplementary Data 1 and 2 are primers used in this study. The Cas9 screen data and IP-MS data are provided in Supplementary Data 3 and 4, respectively. The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary information files or from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Junqi Kuang, Ziwei Zhai.

Contributor Information

Jing Liu, Email: liu_jing@gibh.ac.cn.

Duanqing Pei, Email: peiduanqing@westlake.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-24373-5.

References

- 1.Evans MJ, Kaufman MH. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature. 1981;292:154–156. doi: 10.1038/292154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ying QiLong, Nichols J, Chambers Ian, Smith Austin. BMP induction of Id proteins suppresses differentiation and sustains embryonic stem cell self-renewal in collaboration with STAT3. Cell. 2003;115:281–292. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00847-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ying, Q.-L. & Smith, A. G. Defined Conditions for Neural Commitment and Differentiation. Methods Enzymol.365, 327–341 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Nichols J, Smith A. Naive and primed pluripotent states. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:487–492. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin GR. Isolation of a pluripotent cell line from early mouse embryos cultured in medium conditioned by teratocarcinoma stem cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1981;78:7634–7638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith AG, et al. Inhibition of pluripotential embryonic stem cell differentiation by purified polypeptides. Nature. 1988;336:688–690. doi: 10.1038/336688a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ying QL, et al. The ground state of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nature. 2008;453:519–523. doi: 10.1038/nature06968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams RL, et al. Myeloid leukaemia inhibitory factor maintains the developmental potential of embryonic stem cells. Nature. 1988;336:684–687. doi: 10.1038/336684a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.A Nagy JR, Nagy R, Abramow-Newerly W, Roder JC. Derivation of completely cell culture-derived mice from early-passage embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:8424–8428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kunath T, et al. FGF stimulation of the Erk1/2 signalling cascade triggers transition of pluripotent embryonic stem cells from self-renewal to lineage commitment. Development. 2007;134:2895–2902. doi: 10.1242/dev.02880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tam WL, et al. T-cell factor 3 regulates embryonic stem cell pluripotency and self-renewal by the transcriptional control of multiple lineage pathways. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2019–2031. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leeb M, Dietmann S, Paramor M, Niwa H, Smith A. Genetic exploration of the exit from self-renewal using haploid embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:385–393. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang, B. et al. Screening Genes Promoting Exit from Naive Pluripotency Based on Genome-Scale CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout. Stem Cells Int2020, 8483035 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Li M, et al. Genome-wide CRISPR-KO screen uncovers mTORC1-Mediated Gsk3 regulation in naive pluripotency maintenance and dissolution. Cell Rep. 2018;24:489–502. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Willett, R. et al. TFEB regulates lysosomal positioning by modulating TMEM55B expression and JIP4 recruitment to lysosomes. Nat Commun8, 1580 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Betschinger J, et al. Exit from pluripotency is gated by intracellular redistribution of the bHLH transcription factor Tfe3. Cell. 2013;153:335–347. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li QV, et al. Genome-scale screens identify JNK-JUN signaling as a barrier for pluripotency exit and endoderm differentiation. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:999–1010. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0408-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaji K, et al. The NuRD component Mbd3 is required for pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:285–292. doi: 10.1038/ncb1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guttman M, et al. lincRNAs act in the circuitry controlling pluripotency and differentiation. Nature. 2011;477:295–U260. doi: 10.1038/nature10398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho L, Crabtree GR. Chromatin remodelling during development. Nature. 2010;463:474–484. doi: 10.1038/nature08911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kadoch C, et al. Proteomic and bioinformatic analysis of mammalian SWI/SNF complexes identifies extensive roles in human malignancy. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:592–601. doi: 10.1038/ng.2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kidder BL, Palmer S, Knott JG. SWI/SNF-Brg1 regulates self-renewal and occupies core pluripotency-related genes in embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27:317–328. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ho L, et al. An embryonic stem cell chromatin remodeling complex, esBAF, is an essential component of the core pluripotency transcriptional network. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:5187–5191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812888106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho L, et al. An embryonic stem cell chromatin remodeling complex, esBAF, is essential for embryonic stem cell self-renewal and pluripotency. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:5181–5186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812889106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang WS, et al. The BAF and PRC2 complex subunits Dpf2 and Eed Antagonistically Converge on Tbx3 to control ESC differentiation. Cell Stem Cell. 2019;24:138–152.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shalem Ophir, et al. Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening in human cells. Science. 2014;343:84–87. doi: 10.1126/science.1247005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu J, et al. The oncogene c-Jun impedes somatic cell reprogramming. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015;17:856–867. doi: 10.1038/ncb3193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kadoch C, Crabtree GR. Reversible disruption of mSWI/SNF (BAF) complexes by the SS18-SSX oncogenic fusion in synovial sarcoma. Cell. 2013;153:71–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin T, et al. p53 induces differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells by suppressing Nanog expression. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7:165–171. doi: 10.1038/ncb1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strom AR, et al. Phase separation drives heterochromatin domain formation. Nature. 2017;547:241–245. doi: 10.1038/nature22989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brangwynne CP, et al. Germline P Granules are liquid droplets that localize by controlled dissolution/condensation. Science. 2009;324:1729–1732. doi: 10.1126/science.1172046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sabari, B. R. et al. Coactivator condensation at super-enhancers links phase separation and gene control. Science361, eaar3958 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Wang J, et al. A molecular grammar governing the driving forces for phase separation of prion-like RNA binding proteins. Cell. 2018;174:688–699 e616. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alberti S, Gladfelter A, Mittag T. Considerations and challenges in studying liquid-liquid phase separation and biomolecular condensates. Cell. 2019;176:419–434. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Banani SF, Lee HO, Hyman AA, Rosen MK. Biomolecular condensates: organizers of cellular biochemistry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017;18:285–298. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gatchalian J, et al. A non-canonical BRD9-containing BAF chromatin remodeling complex regulates naive pluripotency in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:5139. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07528-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mashtalir N, et al. Modular organization and assembly of SWI/SNF family chromatin remodeling complexes. Cell. 2018;175:1272–1288 e1220. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takahashi K, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu J, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mali P, et al. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013;339:823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Slaymaker IM, et al. Rationally engineered Cas9 nucleases with improved specificity. Science. 2016;351:84–88. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li W, et al. MAGeCK enables robust identification of essential genes from genome-scale CRISPR/Cas9 knockout screens. Genome Biol. 2014;15:554. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0554-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang X, et al. Proteome-wide identification of ubiquitin interactions using UbIA-MS. Nat. Protoc. 2018;13:530–550. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2017.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ma J, et al. iProX: an integrated proteome resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D1211–D1217. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The RNA-Seq, ChIP-seq data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database under the accession code GSE135451. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the iProX partner repository45 with the dataset identifier PXD026208. Source data are provided with this paper. The source data underlying Figs. 1e, 2d, f, 3c, d, 4c, 5b,6c, d and Supplementary Figs. 1d, g, 2b, d, f, 3c–e, 4c, e–g, 6e, 7b, c, f, g are provided as a Source Data file. Supplementary Data 1 and 2 are primers used in this study. The Cas9 screen data and IP-MS data are provided in Supplementary Data 3 and 4, respectively. The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary information files or from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.