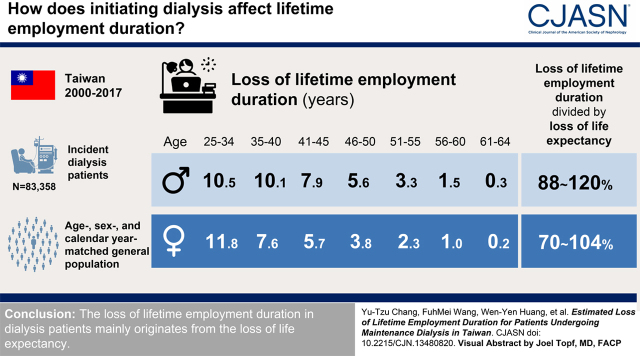

Visual Abstract

Keywords: loss of lifetime employment duration, productivity loss, employment, cost-effectiveness, end-stage kidney disease, dialysis, maintenance

Abstract

Background and objectives

An accurate estimate of the loss of lifetime employment duration resulting from kidney failure can facilitate comprehensive evaluation of societal financial burdens.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

All patients undergoing incident dialysis in Taiwan during 2000–2017 were identified using the National Health Insurance Research Database. The corresponding age-, sex-, and calendar year-matched general population served as the referents. The survival functions and the employment states of the index cohort (patients on dialysis) and their referents for each age strata were first calculated, and then extrapolated until age 65 years, where the sum of the product of the survival function and the employment states was the lifetime employment duration. The difference in lifetime employment duration between the index and referent cohort was the loss of lifetime employment duration. Extrapolation of survival function and relative employment-to-population ratios were estimated by the restricted cubic spline models and the quadratic/linear models, respectively.

Results

A total of 83,358 patients with kidney failure were identified. Men had a higher rate of employment than women in each age strata. The expected loss of lifetime employment duration for men with kidney failure was 11.8, 7.6, 5.7, 3.8, 2.3, 1.0, and 0.2 years for those aged 25–34, 35–40, 41–45, 46–50, 51–55, 56–60, and 61–64 years, respectively; and the corresponding data for women was 10.5, 10.1, 7.9, 5.6, 3.3, 1.5, and 0.3 years, respectively. The values for loss of lifetime employment duration divided by loss of life expectancy were all >70% for women and >88% for men across the different age strata. The sensitivity analyses indicated that the results were robust.

Conclusions

The loss of lifetime employment duration in patients undergoing dialysis mainly originates from loss of life expectancy.

Introduction

The rapid global increase in the number of patients with kidney failure is a growing threat to the global health care system (1). Because of advancements in medical care technologies for patients with kidney failure, we have witnessed improvements in life expectancy and a higher prevalence of kidney failure during the past several decades (1,2). According to the annual report of the United States Renal Data System, the median increase in the rate of occurrence from 2003 to 2016 was 43%, ranging from an 11% to 548% increase for all reported countries (1). This explains why the inflation rate of health care expenditures for kidney failure has been disproportionately higher than that in the general population (1,3). In Taiwan, patients undergoing dialysis represent only 0.3% of the total population, but they contribute to approximately 7% of the annual health care expenditures. A similar phenomenon has also been observed in other countries (1,3,4). It is estimated that around 40%–50% of patients receiving dialysis therapy are of working age (1,5). There is widespread concern that societal financial burdens may be further increased by the potential loss of productivity of these patients (1). In addition, these financial strains also aggravate anxiety and depression among affected patients.

Employment is associated with improved quality of life and relief of financial difficulties in the dialysis population (6,7). Nevertheless, patients undergoing dialysis who are seeking employment face tremendous challenges, including adverse effects from medical procedures, high incidence of cardiovascular diseases and disability, transportation issues, cognitive impairment, scheduling conflicts with dialysis appointments, and employer concerns about absenteeism and dependability (8 –10). This inevitably leads to low employment rates in the dialysis population (11 –16). Encouraging patients on dialysis to remain in or return to the workforce could potentially mitigate the financial burden these patients impose on society, at least through contributions to income taxes. Although quite a few studies have focused on this issue, no previous studies have comprehensively quantified lifetime loss of employment among patients undergoing dialysis (11 –16). In this study, we aimed to estimate the lifetime employment duration and loss of lifetime employment duration of patients undergoing dialysis until 65 years of age, which facilitates stakeholders in establishing appropriate policies for both patients and society as a whole.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources

The protocol for this study was approved by the ethics committee at National Cheng Kung University (approval number 106–009) before commencement. The data originated from the National Health Insurance (NHI) database. The NHI is a universal health care coverage program in Taiwan, launched in 1995 (17,18). In addition to common demographic data and reimbursement information related to clinical diagnosis, treatment, and hospitalization, the NHI database contains employment types on the basis of premium collection as follows: employed in public or private sectors, unemployed, or dependent on family members for insurance. To ensure personal privacy, any individual identification information is encrypted before being recorded in the NHI database. Therefore, informed consent was waived for these participants because of the anonymous nature of the NHI research dataset. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments, or comparable ethical standards.

Design and Study Population

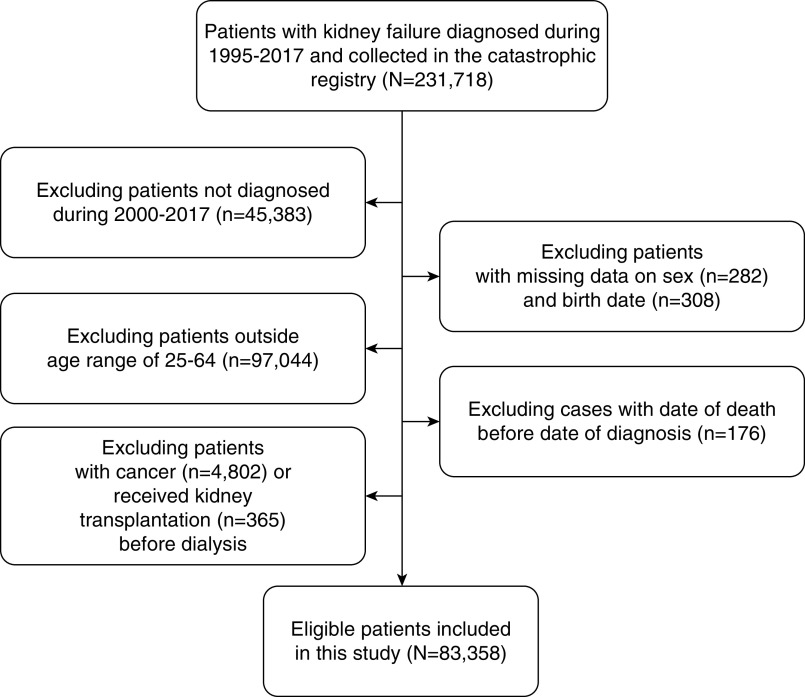

The loss of lifetime employment duration represents how long employment can be retained because of successful prevention of a specific disease such as kidney failure, which could be regarded as a proxy for expected productivity loss. To meet our study objective, we first excluded patients with missing variables, coding errors, and malignancy, and those who received kidney transplantation before the initiation of dialysis therapies. Inclusion criteria were age 25–64 years and initiation of maintenance dialysis therapy during January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2017, from a national dialysis cohort (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code: 585; International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] code: N18.6) (Figure 1). Patients who withdrew from the NHI program for reasons other than mortality, or who received kidney transplantation after enrollment or at the end of the study period, were treated as censored. Because patients receiving kidney transplantation have been shown to have improved survival and employment rates (12,19), censoring such conditions would more accurately quantify the effect of maintenance dialysis. The established dialysis cohort served as the index cohort. Then, we separately estimated the lifetime survival function and the proportion of participants who were employed up to the retirement age of 65 years, for both the index cohort and the reference cohort (the corresponding age-, sex-, and calendar year-matched general population in Taiwan). Consequently, the survival function multiplied by the employment-to-population ratio (EMRATIO) of both the index and reference cohort added up to age 65 were used to obtain the estimates of lifetime employment duration.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the establishment of patients on dialysis as the index cohort.

Estimation of Lifetime Survival Functions of the Index Cohort and Referents

By interlinkage with the longitudinal database of the National Mortality Registry, we ascertained the survival status of each patient on dialysis, and estimated the survival rates of the index cohort up to the end of follow-up by using the Kaplan–Meier method. Using the hazard functions of life tables (20) for different calendar years in Taiwan, we simulated the age-, sex-, and calendar year-matched referents’ lifetime survival functions from the longitudinal database of vital statistics in Taiwan. The survival ratio, which is defined as the ratio between S(t|index) and S(t|reference), at time t between the index group [S(t|index)] and the referents [S(t|reference)], was also calculated up to the end of follow-up. Then, we performed a logit transformation of the survival ratio, which was constructed into a restricted cubic spline model and extrapolated to lifetime with a month-by-month, rolling-over algorithm using the iSQoL2 R Package (21). By taking the advantages of the accurate short-term (namely, 1 month) extrapolation of the restricted cubic spline model after the last knot, we were able to extrapolate the survival function of the index cohort for the following month. We thus adopted the newly estimated month as almost “real,” and refitted the restricted cubic spline model again to extrapolate the next month. Through such a month-by-month, rolling-over extrapolation algorithm, we estimated the lifetime survival function of the index cohort until the survival rate was <0.01. The detailed method of model construction and validation of accuracy has been demonstrated in another study (22).

Construction of the Employment Model and Estimation of Lifetime Employment Duration

During the process of aging, higher prevalence of frailty (23,24), malnutrition (25), cognitive impairment (10,24), and cardiovascular diseases (9) in the dialysis population inevitably leads to dynamic changes in the employment rate over time. The tendency slowly declines after dialysis for 5–10 years because of comorbidities and/or complications, which develop more quickly as these patients grow older. Thus, we stratified our cohort by age (25–34, 35–40, 41–45, 46–50, 51–55, 56–60, and 61–64 years) for estimation instead of simply putting all of them together. The employment status of the index population and their corresponding referents was confirmed by the employment types included in the NHI longitudinal database, where the information is updated every month as long as individuals are paying the premium.

The conventional employment rate in labor economics usually excludes people unwilling to work or not seeking jobs in the denominator. However, such information is unavailable from Taiwan’s NHI dataset. Instead, we applied another widely used alternative employment measure, the EMRATIO, to estimate the lifetime employment duration (26). EMRATIO is the ratio of those currently employed to the total number of people of their corresponding age- and sex-specific strata, which directly reflects the employment status for people with a specific health condition. Because the follow-up time of the current NHI dataset is only 18 years, we had to construct models to extrapolate the probability of employment for young patients, especially those aged between 25 and 50, up to 65 years of age. In this study, we borrowed data from the age-, sex-, and calendar year-matched population’s EMRATIO for modeling and extrapolating up to 65 years of age. To control for dynamic changes under different rates of economic recession and expansion, we calculated the EMRATIO of each age- and sex-stratified subcohort for every month after diagnosis during the follow-up period, and for the matched general population. Assuming that a specific trend exists for the relative ratio between the EMRATIOs of the index and reference cohorts, we constructed models (linear and quadratic) for extrapolations after 18 years of follow-up, if necessary (Supplemental Figure 1). Specifically, we obtained the extrapolated EMRATIO of the index cohort by multiplying the relative EMRATIO by the corresponding referents’ EMRATIO. In the model construction, we stratified data according to sex and seven age strata: 25–34, 35–40, 41–45, 46–50, 51–55, 56–60, and 61–64 years. To avoid the influence of outliers because of the small sample size at the end of the follow-up period, we excluded monthly EMRATIOs of index cohorts with a sample size <100 patients. To check the robustness, we further conducted an extrapolation without excluding the age- and sex-specific subcohort sample. Finally, quadratic models were applied in the extrapolation of the relative EMRATIOs, and linear models were used for the sensitivity analyses.

Results

A total of 83,358 patients undergoing dialysis incident during 2000–2017 were identified for the study (Figure 1). Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the index cohort of patients with kidney failure at the beginning of follow-up. We found that the youngest patients made up a lower proportion of patients with kidney failure in recent years. Regarding employment, men had a higher proportion of employment than women in all age groups, except those aged 41–45 years and 51–55 years. The EMRATIOs for both sexes were the highest for those aged 46–50 years (66% and 66% for men and women, respectively), and were the lowest for those aged 61–64 years (44% and 38%). Women became unemployed at an earlier age than men, and the proportion of employment was <50% for women aged 56–60 years and for both sexes aged 61–64 years. The mean follow-up period (±SD) for estimating life expectancies and EMRATIOs were 78.9±58.1 and 72.7±56.4 months for men and 65.9±51.0 and 60.1±49.7 months for women, respectively. The total follow-up period for estimating life expectancies and EMRATIOs were 3,137,712 and 2,861,994 months for men and 2,818,131 and 2,598,521 months for women, respectively.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the index cohort with kidney failure at the beginning of follow-up (n=83,358)

| Characteristic | Men, n=47,622 | Women, n=35,736 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aged 25–34 years | Aged 35–40 years | Aged 41–45 years | Aged 46–50 years | Aged 51–55 years | Aged 56–60 years | Aged 61–64 years | Aged 25–34 years | Aged 35–40 years | Aged 41–45 years | Aged 46–50 years | Aged 51–55 years | Aged 56–60 years | Aged 61–64 years | |

| Total | 2548 | 3365 | 4520 | 7202 | 9953 | 11,092 | 8942 | 2142 | 2518 | 3384 | 5150 | 6607 | 8162 | 7773 |

| Calendar year, n (%) | ||||||||||||||

| 2000–2005 | 865 (34) | 1067 (32) | 1487 (33) | 2280 (32) | 2735 (28) | 2613 (24) | 2387 (27) | 784 (37) | 1111 (44) | 1573 (47) | 2222 (43) | 2390 (36) | 2485 (30) | 2606 (34) |

| 2006–2011 | 891 (35) | 1039 (31) | 1498 (33) | 2436 (34) | 3581 (36) | 3904 (35) | 2536 (28) | 736 (34) | 655 (26) | 1013 (30) | 1674 (33) | 2309 (35) | 2884 (35) | 2271 (29) |

| 2012–2017 | 792 (31) | 1259 (37) | 1535 (34) | 2486 (35) | 3637 (37) | 4575 (41) | 4019 (45) | 622 (29) | 752 (30) | 798 (24) | 1254 (24) | 1908 (29) | 2793 (34) | 2896 (37) |

| Classification of employment, n (%) | ||||||||||||||

| Employer | 36 (1) | 77 (2) | 162 (4) | 287 (4) | 431 (4) | 448 (4) | 296 (3) | 12 (1) | 32 (1) | 60 (2) | 87 (2) | 115 (2) | 120 (2) | 87 (1) |

| Government sector | 79 (3) | 155 (5) | 263 (6) | 418 (6) | 498 (5) | 452 (4) | 222 (3) | 73 (3) | 115 (5) | 139 (4) | 184 (4) | 151 (2) | 100 (1) | 56 (1) |

| Private sector | 1386 (54) | 1885 (56) | 2464 (55) | 4045 (56) | 5247 (53) | 5073 (46) | 3450 (39) | 1096 (51) | 1407 (56) | 1975 (58) | 3109 (60) | 3861 (58) | 3611 (44) | 2819 (36) |

| Unemployed | 1047 (41) | 1248 (37) | 1631 (36) | 2452 (34) | 3777 (38) | 5119 (46) | 4974 (56) | 961 (45) | 964 (38) | 1210 (36) | 1770 (34) | 2480 (38) | 4331 (53) | 4811 (62) |

| Monthly insurance premium (US$), median (IQR) | ||||||||||||||

| 730 (640–1010) | 760 (640–1273) | 760 (640–1210) | 760 (667–1273) | 760 (700–1273) | 760 (700–1367) | 760 (640–1110) | 700 (640–920) | 700 (640–920) | 700 (640–840) | 700 (640–840) | 730 (640–920) | 730 (640–1010) | 730 (640–800) | |

| Dialysis type, n (%) | ||||||||||||||

| Hemodialysis | 1979 (78) | 2717 (81) | 3840 (85) | 6299 (88) | 8812 (89) | 9984 (91) | 8238 (93) | 1494 (70) | 1921 (77) | 2691 (80) | 4306 (84) | 5691 (87) | 7221 (89) | 7092 (92) |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | ||||||||||||||

| Diabetes | 685 (27) | 1345 (40) | 2296 (51) | 4366 (61) | 6728 (68) | 7955 (72) | 6274 (70) | 513 (24) | 620 (25) | 1047 (31) | 2249 (44) | 3678 (56) | 5236 (64) | 5314 (68) |

| Hypertension | 1504 (59) | 2199 (65) | 3107 (69) | 5116 (71) | 7400 (74) | 8480 (77) | 7040 (79) | 1117 (52) | 1449 (58) | 2176 (64) | 3535 (69) | 4879 (74) | 6179 (76) | 6045 (78) |

| Congestive heart failure | 369 (15) | 585 (17) | 923 (20) | 1640 (23) | 2555 (26) | 3147 (28) | 2750 (31) | 270 (13) | 340 (14) | 567 (17) | 1132 (22) | 1807 (27) | 2541 (31) | 2633 (34) |

| Coronary artery disease | 103 (4) | 282 (8) | 501 (11) | 1002 (14) | 1806 (18) | 2505 (23) | 2221 (25) | 52 (2) | 95 (4) | 224 (7) | 511 (10) | 982 (15) | 1544 (19) | 1731 (22) |

| Myocardial infarction | 23 (1) | 72 (2) | 127 (3) | 258 (4) | 524 (5) | 726 (7) | 704 (8) | 11 (1) | 21 (1) | 46 (1) | 104 (2) | 199 (3) | 382 (5) | 432 (6) |

| Cardiac dysrhythmias | 36 (1) | 71 (2) | 131 (3) | 233 (3) | 456 (5) | 616 (6) | 619 (7) | 34 (2) | 25 (1) | 75 (2) | 152 (3) | 248 (4) | 459 (6) | 611 (8) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 39 (2) | 72 (2) | 125 (3) | 226 (3) | 386 (4) | 542 (5) | 528 (6) | 39 (2) | 49 (2) | 77 (2) | 145 (3) | 216 (3) | 310 (4) | 372 (5) |

| Stroke | 56 (2) | 156 (5) | 286 (6) | 592 (8) | 935 (9) | 1291 (12) | 1111 (12) | 35 (2) | 58 (2) | 118 (4) | 181 (4) | 383 (6) | 616 (8) | 723 (9) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 531 (21) | 914 (27) | 1368 (30) | 2283 (32) | 3410 (34) | 3887 (35) | 3021 (34) | 457 (21) | 524 (21) | 756 (22) | 1449 (28) | 2343 (36) | 3062 (38) | 2877 (37) |

| Rheumatologic disease | 103 (4) | 56 (2) | 54 (1) | 59 (1) | 85 (1) | 101 (1) | 89 (1) | 400 (19) | 271 (11) | 234 (7) | 207 (4) | 206 (3) | 234 (3) | 207 (3) |

| Chronic liver disease and viral hepatitis | 201 (8) | 385 (11) | 618 (14) | 956 (13) | 1307 (13) | 1312 (12) | 954 (11) | 86 (4.0) | 165 (7) | 207 (6) | 402 (8) | 474 (7) | 641 (8) | 653 (8) |

IQR, interquartile range.

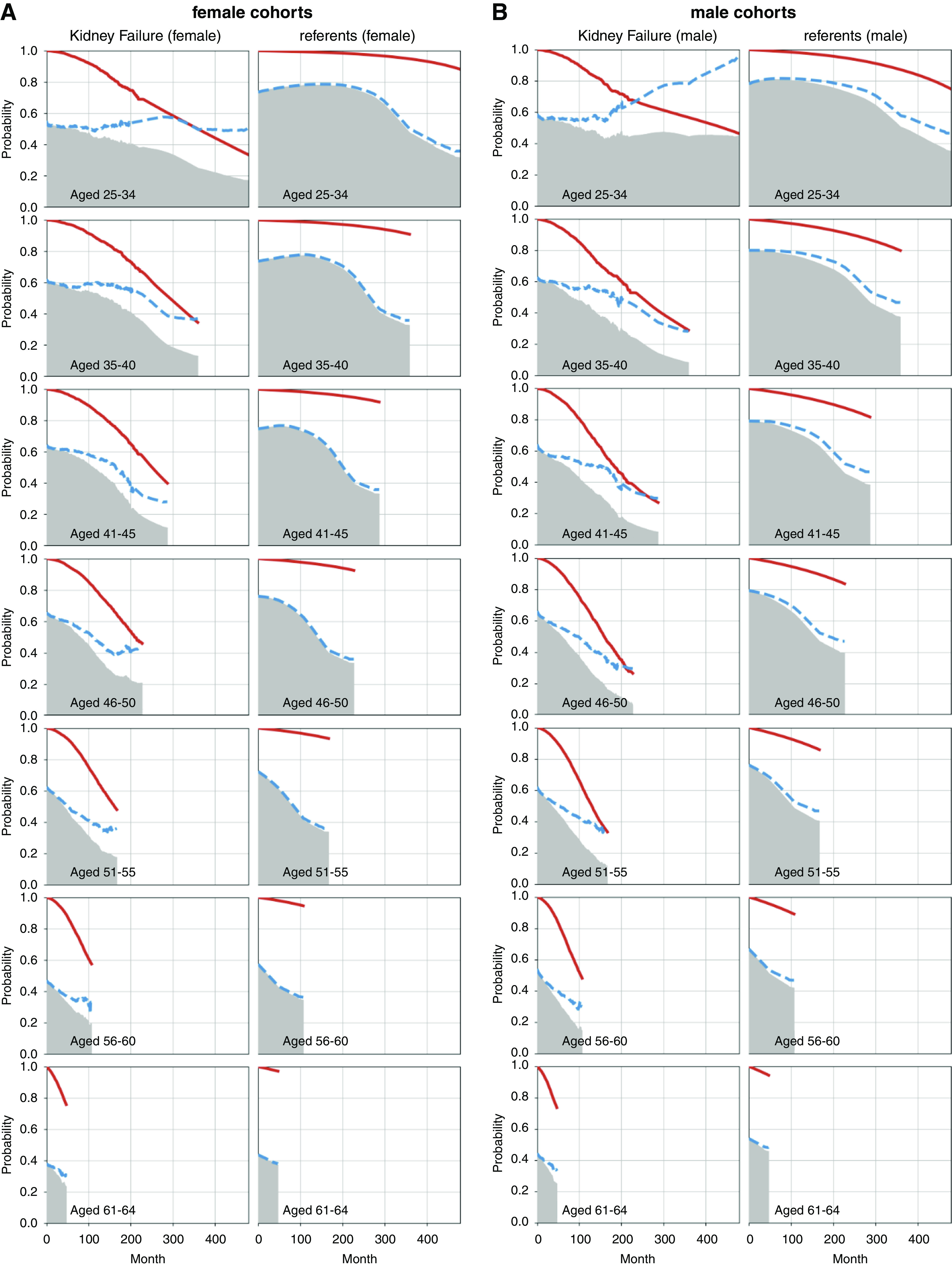

Figure 2 and Supplemental Figure 2 show the survival function curves, EMRATIOs (estimated by the quadratic and linear model, respectively), the products of the two functions, the employment-adjusted survival curves of the index cohort (left column), and the corresponding referents (right column) until 65 years of age. The areas below the employment-adjusted survival curves can be summarized as lifetime employment durations. Our results showed that survival rates in both the referents and lifetime employment duration were better than those of the index cohorts. Although the referents’ EMRATIOs were higher than those of the index cohorts most of the time, in Figure 2, the latter showed higher EMRATIOs than the corresponding referents in some age groups close to the regular retirement age of 65 years. The real and estimated relative ratios of the EMRATIO of the index and referent cohorts are provided in Supplemental Figure 1. In addition, the real EMRATIOs fluctuated over time, so the derived employment-adjusted survival curves naturally fluctuated as well.

Figure 2.

Expected lifetime employment duration (shadowed areas) of (A) female and (B) male patients with kidney failure and corresponding age-, sex-, and calendar year-matched general population (referents), stratified by age. Red lines indicate the survival curves, and the dashed blue lines indicate the employment ratios of the corresponding population, which are estimated by the quadratic model.

Table 2 shows that kidney failure did affect the patients’ life expectancies and lifetime employment durations up to age 65 years. For both sexes, the loss of lifetime employment duration was negatively correlated with the age of the index cohorts, which implies that later onset of kidney failure has a smaller effect on the patient’s career, from an employment perspective. The highest mean and SEM of loss of lifetime employment duration for men and women were 10.5±1.3 and 11.8±1.1 years, respectively, in the 25–34 years age group. The values of loss of lifetime employment duration were only 0.3±0.0 and 0.2±0.0 years for men and women aged 61–64 years, respectively. Male patients appeared to suffer from a longer loss of lifetime employment duration compared with female patients. Furthermore, the difference between loss of life expectancy and loss of lifetime employment duration in each strata appeared to be small, i.e., ranging from 0.0 to 1.0 years. The loss of lifetime employment duration divided by loss of life expectancy values were all >70% for women and >88% for men across the different age strata. This highlights that the loss of lifetime employment duration results mainly from the loss of life expectancy in the dialysis population. In other words, the typically lower EMRATIOs of the index cohort compared with the age-, sex-, and calendar year-matched referents in each stratum may play a relatively minor role in the loss of lifetime employment duration.

Table 2.

Life expectancy up to age 65 years and loss of lifetime employment duration of patients with kidney failure (index group), compared with age-, sex-, and calendar year-matched referents

| Age at Diagnosis of Kidney Failure, Yr | Life Expectancy up to Age 65 Yr | Lifetime Employment Duration | Loss of Lifetime Employment Duration/Loss of Life Expectancy up to Age 65 Yr (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Referents, Yr, Mean±SEM | Index, Yr, Mean±SEM | Loss of Life Expectancy up to Age 65 Yr, Yr, Mean±SEM (%) | Referents, Yr, Mean±SEM | Index, Yr, Mean±SEM | Loss of Lifetime Employment Duration, Yra, Mean±SEM (%) | ||

| Women | |||||||

| Aged 25–34 | 33.5±0.1 | 22.1±1.0 | 11.4±1.0 (34) | 23.5±0.1 | 11.6±1.1 | 11.8±1.1 (50) | 104 |

| Aged 35–40 | 26.0±0.0 | 18.1±0.5 | 7.9±0.5 (30) | 17.6±0.0 | 10.0±0.4 | 7.6±0.4 (43) | 97 |

| Aged 41–45 | 20.8±0.0 | 14.5±0.3 | 6.3±0.3 (30) | 13.5±0.0 | 7.8±0.2 | 5.7±0.2 (42) | 91 |

| Aged 46–50 | 16.0±0.0 | 11.1±0.3 | 4.8±0.3 (30) | 9.7±0.0 | 5.9±0.2 | 3.8±0.2 (39) | 79 |

| Aged 51–55 | 11.2±0.0 | 8.0±0.2 | 3.2±0.2 (29) | 6.2±0.0 | 3.9±0.1 | 2.3±0.1 (37) | 70 |

| Aged 56–60 | 6.3±0.0 | 4.9±0.1 | 1.4±0.1 (23) | 2.9±0.0 | 1.9±0.0 | 1.0±0.0 (35) | 71 |

| Aged 61–64 | 1.9±0.0 | 1.7±0.0 | 0.3±0.0 (14) | 0.8±0.0 | 0.6±0.0 | 0.2±0.0 (26) | 79 |

| Men | |||||||

| Aged 25–34 | 32.2±0.1 | 21.2±0.9 | 10.9±0.9 (34) | 23.9±0.0 | 13.5±1.3 | 10.5±1.3 (44) | 96 |

| Aged 35–40 | 25.1±0.0 | 15.1±0.6 | 10.0±0.6 (40) | 18.1±0.0 | 8.0±0.4 | 10.1±0.4 (56) | 100 |

| Aged 41–45 | 20.0±0.0 | 11.7±0.3 | 8.2±0.3 (41) | 14.0±0.0 | 6.1±0.2 | 7.9±0.2 (56) | 96 |

| Aged 46–50 | 15.4±0.0 | 9.3±0.3 | 6.1±0.3 (54) | 10.4±0.0 | 4.8±0.1 | 5.6±0.1 (54) | 91 |

| Aged 51–55 | 10.9±0.0 | 7.1±0.2 | 3.8±0.2 (35) | 6.8±0.0 | 3.5±0.1 | 3.3±0.1 (49) | 88 |

| Aged 56–60 | 6.2±0.0 | 4.6±0.1 | 1.6±0.1 (26) | 3.5±0.0 | 2.0±0.0 | 1.5±0.0 (44) | 96 |

| Aged 61–64 | 2.0±0.0 | 1.7±0.0 | 0.3±0.0 (14) | 1.0±0.0 | 0.7±0.0 | 0.3±0.0 (32) | 120 |

Percentage of loss of lifetime employment duration was calculated by dividing the loss of lifetime employment duration by the lifetime employment duration of the referents.

Sensitivity Analyses

Besides the adoption of quadratic models and the exclusion of extreme values, we conducted sensitivity analyses of the lifetime employment duration and loss of lifetime employment duration related to kidney failure with linear models, and the inclusion of all 216 months of data. Although the 18 years of follow-up covered all data needed to calculate the lifetime employment duration up to age 65 years for patients aged ≥51 years, predictive models were needed for extrapolation to age 65 years for young patients aged <50 years. In general, the higher the age, the less likely that different models would predict different values for the extrapolated periods up to 65 years of age.

Table 3 shows the results of sensitivity analyses for the various models, with exclusion of sample sizes <100. We found that variations were the largest among the youngest cohort (aged 25–34 years). For patients aged 25–34 years, the losses of lifetime employment duration (±SEM) varied from 11.4±1.2 years to 12.9±0.6 years for women, and from 10.5±1.3 years to 13.5±1.3 years for men. However, the maximum differences under the different models were only 1.3 and 1.7 years for the youngest women and men, respectively. In general, the older the age, the smaller the difference in both sexes. The maximum differences in the estimated losses of lifetime employment duration in patients aged 41–45 years and 46–50 years were smaller than 0.1 years for both women and men. The results of sensitivity analyses indicated the robustness of this study.

Table 3.

Sensitivity analyses of the lifetime employment duration of the kidney failure group and the loss of lifetime employment duration from quadratic models and linear models, stratified by exclusion of sample sizes <100

| Age at Diagnosis of Kidney Failure, Yr | Lifetime Employment Duration of General Population, Yr, Mean±SEM | Quadratic Model | Linear Model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With Exclusion | No Exclusion | With Exclusion | No Exclusion | ||||||

| Lifetime Employment Duration of Dialysis Group, Yr, Mean±SEM | Loss of Lifetime Employment Duration of Dialysis Group, Yr, Mean±SEM | Lifetime Employment Duration of Dialysis Group, Yr, Mean±SEM | Loss of Lifetime Employment Duration of Dialysis Group, Yr, Mean±SEM | Lifetime Employment Duration of Dialysis Group, Yr, Mean±SEM | Loss of Lifetime Employment Duration of Dialysis Group, Yr, Mean±SEM | Lifetime Employment Duration of Dialysis Group, Yr, Mean±SEM | Loss of Lifetime Employment Duration of Dialysis Group, Yr, Mean±SEM | ||

| Women | |||||||||

| Aged 25–34 | 23.5±0.1 | 11.6±1.1 | 11.8±1.1 | 12.1±1.2 | 11.4±1.2 | 10.5±0.6 | 12.9±0.6 | 10.8±0.7 | 12.7±0.7 |

| Aged 35–40 | 17.6±0.0 | 10.0±0.4 | 7.6±0.4 | 9.9±0.4 | 7.7±0.4 | 9.8±0.3 | 7.8±0.3 | 9.8±0.3 | 7.8±0.3 |

| Aged 41–45 | 13.5±0.0 | 7.8±0.2 | 5.7±0.2 | 7.7±0.2 | 5.8±0.2 | 7.8±0.2 | 5.7±0.2 | 7.7±0.2 | 5.8±0.2 |

| Aged 46–50 | 9.7±0.0 | 5.9±0.2 | 3.8±0.2 | 5.9±0.2 | 3.8±0.2 | 5.9±0.2 | 3.8±0.2 | 5.9±0.2 | 3.8±0.2 |

| Men | |||||||||

| Aged 25–34 | 23.9±0.0 | 13.5±1.3 | 10.5±1.3 | 13.1±1.3 | 10.8±1.3 | 11.7±0.7 | 12.2±0.7 | 11.8±0.7 | 12.1±0.7 |

| Aged 35–40 | 18.1±0.0 | 8.0±0.4 | 10.1±0.4 | 8.3±0.5 | 9.8±0.5 | 8.0±0.4 | 10.1±0.4 | 8.1±0.4 | 10.0±0.4 |

| Aged 41–45 | 14.0±0.0 | 6.1±0.2 | 7.9±0.2 | 6.1±0.2 | 7.9±0.2 | 6.1±0.2 | 7.9±0.2 | 6.1±0.2 | 7.9±0.2 |

| Aged 46–50 | 10.4±0.0 | 4.8±0.1 | 5.6±0.1 | 4.8±0.1 | 5.5±0.1 | 4.8±0.1 | 5.6±0.1 | 4.8±0.1 | 5.5±0.1 |

Discussion

Conventional economic evaluations of the burden of specific illnesses, including kidney failure, on health care systems or individuals typically use quality-adjusted life years, disability-adjusted life years, and loss of life years as indicators (27 –29). After 2 to 3 decades of development, however, experts have begun to quantify effects from societal perspectives, including loss of productivity, need for social services, and crime incidence (30). Although human capital loss from mortality has previously been quantified as potential working life loss (31), this study endeavors to estimate loss of lifetime employment duration as a proxy for productivity loss among those with kidney failure, on the basis of real-world data. Although kidney failure indeed causes loss of lifetime employment duration, our study results clearly demonstrate that the loss of lifetime employment duration in the dialysis population mainly results from loss of life expectancy (Table 2). This highlights the phenomenon that many patients with kidney failure in Taiwan remain as productive as those without kidney failure, and their contributions should not be ignored from a societal perspective. In our clinical experience, most patients with kidney failure who are employed typically suffer from emotional distress because of fear of losing their jobs when they initiated maintenance dialysis therapy. Therefore, our results strongly corroborate the assertion that dialysis not only saves lives, but also increases lifetime employment duration, which hopefully contributes to patient trust and self-confidence when initiating dialysis. Because patients receiving maintenance dialysis are usually comorbid with many chronic illnesses, the loss of lifetime employment duration should be attributed not just to kidney failure, but also the associated comorbidities. Furthermore, our study results highlight the importance of the timely integration of a CKD educational plan and modern medical therapies to ameliorate kidney function decline in young patients with CKD (32,33). The slower the decline to kidney failure, the longer the life expectancy, which would reciprocally contribute to longer employment duration, reduced financial burden of those with CKD, and increased funding to the health care system through tax or insurance payments.

In contrast to intuitive conjecture, we found that, after receiving long-term dialysis therapy, the estimated EMRATIOs of patients with kidney failure can be equal to, or even slightly higher than, those of patients without kidney failure among patients aged 25–34 years in both sexes and in women aged 46–50 years (Figure 2). One of the major reasons for this may be attributed to the promulgation of the People with Disabilities Rights Protection Act in Taiwan (34). This act stipulates that public and private agencies should hire individuals with permanent functional disabilities at a ratio of no less than 3% and 1%, respectively, relative to their total number of employees. Furthermore, agencies are rewarded by the government if they hire people with disabilities, up to the required percentage. This generally creates economic incentives and directly protects the rights and interests of people with disabilities (34), including patients under maintenance dialysis. In fact, the choice of home dialysis, peritoneal dialysis, or hemodialysis after work hours can help patients to continue their employment (11,12,35). Therefore, this policy in Taiwan might be a good example of reducing the potential loss of productivity in the dialysis population, and further mitigating the financial burden of this disease on society.

Our study results revealed that the employment rates among the dialysis population in Taiwan were higher than those in other countries (11 –16). Several factors associated with employment among patients undergoing dialysis have been commonly proposed, including dialysis modalities (11,12,35,36) and predialysis employment (16,37). Although a direct causal relationship may still be debatable (16), it is known that peritoneal dialysis and home hemodialysis are associated with higher employment rates compared with other dialysis modalities (11,12,35,36). Because the penetration rates of peritoneal dialysis are <10%, and the utilization of home hemodialysis is uncommon in Taiwan (38), these two modalities may contribute to only a minor proportion of the high employment rates among patients undergoing dialysis in Taiwan. In contrast, the predialysis employment rates in our study were generally above 55%–60% among those younger than 55 years, which seems higher than those found in other studies (13,16,37). In addition, the density of dialysis centers is high in Taiwan, and most of them provide regular services after 5:00 pm. Therefore, patients undergoing dialysis can choose any dialysis center convenient to them. Because providing evening/night services may enhance employment for these patients (11), the flexible dialysis schedule fully reimbursed by Taiwan’s health care system appears to be the main reason for the high employment rate among patients under maintenance dialysis. Because the progression of uremic symptoms (anemia, poor appetite, fatigue), malnutrition, and multiple comorbidities could force patients to leave the workforce temporarily or permanently, before and after the initiation of dialysis, a multidisciplinary intervention program for patients with kidney failure to maintain or rejoin the workforce should be encouraged in clinical practice (39). Future studies comparing different policies implemented in different countries are warranted for long-term improvements in employment rates and the welfare of people receiving dialysis.

There are several limitations in our study. First, because it was necessary to extrapolate the EMRATIOs of patients undergoing dialysis and matched referents after 18 years of follow-up, there are concerns about the estimation accuracy for such a disease with major complications and comorbidities, especially in the subgroup of those aged 25–40 years. However, we applied two different models, linear and quadratic, to estimate the dynamic changes in the EMRATIO, and the results indicated that the differences in the estimated lifetime employment duration between these two models were minimal (Table 3). Specifically, the differences between the two ranged from 0 to 1.6 of a year, indicating the robustness of these estimations. Second, we only considered whether the patient was currently employed or not, but did not consider any possible changes in occupation, position, assigned tasks, or types of employment. In general, patients may have shifted from a full-time to part-time job after receiving dialysis because of physical and psychologic barriers (9,10,40). We recommend that future research considers monetary or salary/wage losses because this information may more closely reflect the productivity loss associated with changes in position or type of employment. Third, because the comorbidities, survival, life expectancies, and employment rates of dialysis populations in different countries are usually quite different, our results cannot be directly generalized to populations outside of Taiwan. For example, the life expectancies and employment rates are lower in several Western countries than in Taiwan (2,11 –16,29), which might result in a different magnitudes of loss of life expectancy and loss of lifetime employment duration. Therefore, the generalization of our study findings to other countries must be carried out with care. However, because all of the estimations in our study were adjusted to the age-, sex-, and calendar year-matched general population of Taiwan, the internal validity or comparison within the same country would be good under the conceptual difference-in-differences framework. Fourth, we chose to censor patients undergoing dialysis at transplantation to quantify the pure effect of kidney failure on loss of lifetime employment duration. Therefore, it might overestimate the contribution of mortality on loss of lifetime employment duration. The potential estimation bias would be larger in the youngest group (25–34 years), who have a higher probability of receiving kidney transplantation. As this study only followed participants for 18 years, it would inevitably increase the uncertainties of extrapolating survival and employment status for them. In addition, we did not explore the effect of kidney transplantation and the subsequent dialysis period after graft failure on loss of lifetime employment duration. Therefore, our study results might not comprehensively reflect all different conditions, and the interpretation of data on this group should be cautious.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that patients undergoing dialysis had lower lifetime employment duration than corresponding age-, sex-, and calendar year-matched normal individuals. Because the absolute differences in loss of life expectancy and loss of lifetime employment duration were generally <1 year between the patients undergoing dialysis and their corresponding referents, it appears that the loss of lifetime employment duration in patients undergoing dialysis in Taiwan mainly resulted from a loss of life expectancy.

Disclosures

Y.-T. Chang reports honoraria from Baxter, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Merck Sharp and Dohme, and Novo Nordisk. H. Hsiao reports employment with National Cheng Kung University. W.-Y. Huang reports employment with Taiwan National Cheng Kung University. C.-C. Lin reports employment with National Cheng Kung University and research funding from The Ministry of Science and Technology in Taiwan (grant numbers MOST 107-2410-H-006-015, MOST 108-2410-H-006-009, MOST 108-2627-M-006-001, and MOST 109-2410-H-006-081). F. Wang reports employment with National Cheng Kung University. The remaining author has nothing to disclose.

Funding

The present research was supported by Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology grant MOST108-2627-M006-001 and by grant NCKUH-11002022 from National Cheng-Kung University Hospital.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Health Data Science Center, National Cheng Kung University Hospital, for providing administrative and technical support.

None of the funding sources had any role in the study design, analysis and interpretation of the data, the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

The content of this publication does not reflect the views or policies of the National Health Insurance Administration.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related Patient Voice, “A Dialysis Patient’s View on Dialysis Employment Loss,” on pages 669–670.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.13480820/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Figure 1. Predicted index group’s employment-to-population ratio (EMRATIO) compared with the general population group’s EMRATIO trend in (A) women and (B) men.

Supplemental Figure 2. Expected lifetime employment duration (shadowed areas) of (A) female and (B) male patients with kidney failure and those of the corresponding age-, sex-, and calendar year-matched general population (referents), stratified by age. Red lines indicate the survival curves and the dashed blue lines indicate the employment ratios of the corresponding population which are estimated by the linear model.

References

- 1. United States Renal Data System : Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2018. Available at: https://www.usrds.org/annual-data-report/previous-adrs/. Accessed Febuary 20, 2021.

- 2. Foster BJ, Mitsnefes MM, Dahhou M, Zhang X, Laskin BL: Changes in excess mortality from end stage renal disease in the United States from 1995 to 2013. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 91–99, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Klarenbach SW, Tonelli M, Chui B, Manns BJ: Economic evaluation of dialysis therapies. Nat Rev Nephrol 10: 644–652, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Manns BJ, Mendelssohn DC, Taub KJ: The economics of end-stage renal disease care in Canada: Incentives and impact on delivery of care. Int J Health Care Finance Econ 7: 149–169, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Taiwan Society of Nephrology: Annual Report of Kidney Disease in Taiwan, 2018. Available at: https://www.tsn.org.tw/UI/L/L002.aspx. Accessed July 1, 2020

- 6. Blake C, Codd MB, Cassidy A, O’Meara YM: Physical function, employment and quality of life in end-stage renal disease. J Nephrol 13: 142–149, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kusek JW, Greene P, Wang SR, Beck G, West D, Jamerson K, Agodoa LY, Faulkner M, Level B: Cross-sectional study of health-related quality of life in African Americans with chronic renal insufficiency: The African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension trial. Am J Kidney Dis 39: 513–524, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hallab A, Wish JB: Employment among patients on dialysis: An unfulfilled promise. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 203–204, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chang YT, Wu JL, Hsu CC, Wang JD, Sung JM: Diabetes and end-stage renal disease synergistically contribute to increased incidence of cardiovascular events: A nationwide follow-up study during 1998-2009. Diabetes Care 37: 277–285, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kuo Y-T, Li C-Y, Sung J-M, Chang C-C, Wang J-D, Sun C-Y, Wu J-L, Chang Y-T: Risk of dementia in patients with end-stage renal disease under maintenance dialysis-A nationwide population-based study with consideration of competing risk of mortality. Alzheimers Res Ther 11: 31, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kutner N, Bowles T, Zhang R, Huang Y, Pastan S: Dialysis facility characteristics and variation in employment rates: A national study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 111–116, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Helanterä I, Haapio M, Koskinen P, Grönhagen-Riska C, Finne P: Employment of patients receiving maintenance dialysis and after kidney transplant: A cross-sectional study from Finland. Am J Kidney Dis 59: 700–706, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Erickson KF, Zhao B, Ho V, Winkelmayer WC: Employment among patients starting dialysis in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 265–273, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kutner NG, Brogan D, Fielding B: Employment status and ability to work among working-age chronic dialysis patients. Am J Nephrol 11: 334–340, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lakshmi BS, Kumar ACV, Reddy HK, Gopal J, Chaitanya V, Chandra VS, Sandeep P, Nagaraju RD, Ram R, Kumar VS: Employment status of patients receiving maintenance dialysis - peritoneal and hemodialysis: A cross-sectional study. Indian J Nephrol 27: 384–388, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. van Manen JG, Korevaar JC, Dekker FW, Reuselaars MC, Boeschoten EW, Krediet RT; NECOSAD Study Group: Changes in employment status in end-stage renal disease patients during their first year of dialysis. Perit Dial Int 21: 595–601, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. National Health Insurance Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare: 2017-2018 National Health Insurance Annual Report, 2017. Available at: https://www.nhi.gov.tw/Nhi_E-LibraryPubWeb/Periodical/P_Detail.aspx?CPT_TypeID=8&CP_ID=207. Accessed July 1, 2020

- 18. Wu TY, Majeed A, Kuo KN: An overview of the healthcare system in Taiwan. London J Prim Care (Abingdon) 3: 115–119, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kaballo MA, Canney M, O’Kelly P, Williams Y, O’Seaghdha CM, Conlon PJ: A comparative analysis of survival of patients on dialysis and after kidney transplantation. Clin Kidney J 11: 389–393, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Department of Statistics , Ministry of the Interior: Abridged Life Table in Republic of China Area, 2021. Available at: https://www.moi.gov.tw/english/cl.aspx?n=7780&page=1&PageSize=10. Accessed January 22, 2021

- 21. Hwang JS: iSQoL2 Package for Windows. Available at: http://sites.stat.sinica.edu.tw/isqol/. Accessed July 1, 2020

- 22. Hwang JS, Hu TH, Lee LJ, Wang JD: Estimating lifetime medical costs from censored claims data. Health Econ 26: e332–e344, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McAdams-DeMarco MA, Tan J, Salter ML, Gross A, Meoni LA, Jaar BG, Kao WH, Parekh RS, Segev DL, Sozio SM: Frailty and cognitive function in incident hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 2181–2189, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kallenberg MH, Kleinveld HA, Dekker FW, van Munster BC, Rabelink TJ, van Buren M, Mooijaart SP: Functional and cognitive impairment, frailty, and adverse health outcomes in older patients reaching ESRD-A systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1624–1639, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fouque D, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kopple J, Cano N, Chauveau P, Cuppari L, Franch H, Guarnieri G, Ikizler TA, Kaysen G, Lindholm B, Massy Z, Mitch W, Pineda E, Stenvinkel P, Treviño-Becerra A, Wanner C: A proposed nomenclature and diagnostic criteria for protein-energy wasting in acute and chronic kidney disease [published correction appears in Kidney Int 74:393, 2008]. Kidney Int 73: 391–398, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Key Indicators of the Labour Market, 2016. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—stat/documents/publication/wcms_498929.pdf. Accessed July 1, 2020

- 27. Neumann PJ, Cohen JT: QALYs in 2018-Advantages and concerns. JAMA 319: 2473–2474, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, O'Brien BJ, Stoddart GL: Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes, United Kingdom, Oxford University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chang YT, Hwang JS, Hung SY, Tsai MS, Wu JL, Sung JM, Wang JD: Cost-effectiveness of hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis: A national cohort study with 14 years follow-up and matched for comorbidities and propensity score. Sci Rep 6: 30266, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Neumann PJ: Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine, 2nd Ed., edited by Sanders GD, Russell LB, Siegel JE, Ganiats TG, New York, Oxford University Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bradley CJ, Yabroff KR, Dahman B, Feuer EJ, Mariotto A, Brown ML: Productivity costs of cancer mortality in the United States: 2000-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst 100: 1763–1770, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Xie X, Liu Y, Perkovic V, Li X, Ninomiya T, Hou W, Zhao N, Liu L, Lv J, Zhang H, Wang H: Renin-angiotensin system inhibitors and kidney and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with CKD: A Bayesian network meta-analysis of randomized clinical Trials. Am J Kidney Dis 67: 728–741, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Heerspink HJL, Stefánsson BV, Correa-Rotter R, Chertow GM, Greene T, Hou FF, Mann JFE, McMurray JJV, Lindberg M, Rossing P, Sjöström CD, Toto RD, Langkilde AM, Wheeler DC; DAPA-CKD Trial Committees and Investigators: Dapagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 383: 1436–1446, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ministry of Health and Welfare: People with Disabilities Rights Protection Act, 2015. Available at: https://law.moj.gov.tw/Eng/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?PCode=D0050046. Accessed July 1, 2020

- 35. Julius M, Kneisley JD, Carpentier-Alting P, Hawthorne VM, Wolfe RA, Port FK: A comparison of employment rates of patients treated with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis vs in-center hemodialysis (Michigan End-Stage Renal Disease Study). Arch Intern Med 149: 839–842, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wolcott DL, Nissenson AR: Quality of life in chronic dialysis patients: A critical comparison of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) and hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 11: 402–412, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Curtin RB, Oberley ET, Sacksteder P, Friedman A: Differences between employed and nonemployed dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 27: 533–540, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jain AK, Blake P, Cordy P, Garg AX: Global trends in rates of peritoneal dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 533–544, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rasgon S, Schwankovsky L, James-Rogers A, Widrow L, Glick J, Butts E: An intervention for employment maintenance among blue-collar workers with end-stage renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis 22: 403–412, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Palmer S, Vecchio M, Craig JC, Tonelli M, Johnson DW, Nicolucci A, Pellegrini F, Saglimbene V, Logroscino G, Fishbane S, Strippoli GF: Prevalence of depression in chronic kidney disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Kidney Int 84: 179–191, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.