Significance Statement

Although reports from around the world have indicated the case fatality rate of novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) among patients with ESKD is between 20% and 30%, the population-level effect of COVID-19 is uncertain. In a retrospective analysis of data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, during epidemiologic weeks 13–27 of 2020, adjusted relative rates of death were 17% higher among patients undergoing dialysis, and 30% higher among patients with a kidney transplant relative to corresponding weeks in 2017 to 2019. COVID-19 hospitalization rates and excess mortality both exhibited racial disparities. The severe effects of COVID-19 on patients with ESKD should be considered in the prioritization of these patients for COVID-19 vaccination.

Keywords: COVID-19, dialysis, hospitalization, mortality, transplantation

Abstract

Background

Reports from around the world have indicated a fatality rate of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the range of 20%–30% among patients with ESKD. Population-level effects of COVID-19 on patients with ESKD in the United States are uncertain.

Methods

We identified patients with ESKD from Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services data during epidemiologic weeks 3–27 of 2017–2020 and corresponding weeks of 2017–2019, stratifying them by kidney replacement therapy. Outcomes comprised hospitalization for COVID-19, all-cause death, and hospitalization for reasons other than COVID-19. We estimated adjusted relative rates (ARRs) of death and non–COVID-19 hospitalization during epidemiologic weeks 13–27 of 2020 (March 22 to July 4) versus corresponding weeks in 2017–2019.

Results

Among patients on dialysis, the rate of COVID-19 hospitalization peaked between March 22 and April 25 2020. Non-Hispanic Black race and Hispanic ethnicity associated with higher rates of COVID-19 hospitalization, whereas peritoneal dialysis was associated with lower rates. During weeks 13–27, ARRs of death in 2020 versus 2017–2019 were 1.17 (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.16 to 1.19) and 1.30 (95% CI, 1.24 to 1.36) among patients undergoing dialysis or with a functioning transplant, respectively. Excess mortality was higher among non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and Asian patients. Among patients on dialysis, the rate of non–COVID-19 hospitalization during weeks 13–27 in 2020 was 17% lower versus hospitalization rates for corresponding weeks in 2017–2019.

Conclusions

During the first half of 2020, the clinical outcomes of patients with ESKD were greatly affected by COVID-19, and racial and ethnic disparities were apparent. These findings should be considered in prioritizing administration of COVID-19 vaccination.

Approximately 800,000 patients receive treatment for ESKD in the United States.1 Seven in ten undergo maintenance dialysis, whereas the remainder live with a kidney transplant.1 Patients undergoing dialysis carry numerous factors—aside from kidney disease itself2,3—that are associated with higher risk of novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) hospitalization and death. Nearly half are elderly (age ≥65 years), and relative to the general population, Black race is overrepresented (33% versus 13%).1 Among patients on dialysis with Medicare coverage, the prevalence of diabetes, heart failure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is 68%, 54%, and 32%, respectively; in the population of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries, the prevalence of these three conditions is 27%, 14%, and 11%.4 Over one-third of patients who initiate dialysis live in postal codes where ≥20% of the population is below the federal poverty level.5 Moreover, nearly nine in ten patients undergo thrice-weekly in-facility hemodialysis (HD),1 and many depend on public transport services between home and their dialysis facility. Patients with a kidney transplant, who are less likely to carry noted risk factors, require treatment with immunosuppressants, placing them at higher risk of severe COVID-19.6

Registry reports in Europe have indicated that the fatality rate of COVID-19 among patients with ESKD is between 20% and 30%,7–10 a range corroborated by single-center studies in the United States.11,12 However, the initial effect of COVID-19 on population-level outcomes in the United States has not yet been assessed. We estimated rates of COVID-19 hospitalization among patients on dialysis with Medicare coverage during the first half of 2020 and excess rates of all-cause mortality among all patients on dialysis or with a transplant in 2020, relative to 2017–2019. To assess the indirect effect of the pandemic on clinical outcomes, we also estimated changes in rates of non-COVID-19 hospitalization among patients on dialysis between 2017–2019 and 2020.

Methods

We analyzed an extract of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Renal Management Information System (REMIS), encompassing data available at the end of the third quarter of 2020. REMIS enumerates the ESKD population and includes submissions of forms CMS-2728 (ESKD Medical Evidence Report, completion of which is mandated after ESKD onset) and CMS-2746 (ESKD Death Notification), dialysis facility admission, and discharge records from the Consolidated Renal Operations in a Web-Enabled Network (CROWNWeb), kidney transplant records from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, and Medicare claims for hospitalization and outpatient dialysis. In REMIS, dates of death are extracted from submissions of form CMS-2746 and the Medicare Enrollment Database. Due to lags in form submission, data are essentially complete only through the second quarter of 2020.

We analyzed the incidence of clinical outcomes during epidemiologic weeks 3–27 of 2020 (January 12 to July 4) and, for comparison, during corresponding weeks of 2017–2019. An epidemiologic week, which begins on a Sunday and ends on the next Saturday, is a widely used construct in infectious disease surveillance and is used by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to facilitate year-over-year comparisons. We identified adult patients with ESKD at the beginning of each week, as established by four criteria: (1) a date of ESKD diagnosis before the first day of the week, (2) the absence of death records before the first day of the week, (3) the absence of a CROWNWeb record indicating recovery of kidney function immediately before the first day of the week, and (4) age ≥18 years at the beginning of the week. Patients were stratified by kidney replacement therapy—either dialysis or a functioning kidney transplant. Patients with a transplant were identified by a record of a functioning transplant that overlapped the first day of the week and the absence of a CROWNWeb record indicating dialysis facility admission immediately before the first day of the week. In the subgroup of patients undergoing dialysis, Medicare fee-for-service coverage was identified by an outpatient dialysis claim during the 3-month interval preceding the first day of the week. Those patients with Medicare coverage were stratified by modality—either HD or peritoneal dialysis (PD)—on the basis of the revenue center code listed on the last claim before the first day of the week. Approximately 98% of patients undergoing HD are treated in a facility, whereas nearly all patients undergoing PD are treated at home.1 For every patient, we identified age at the beginning of the week, race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Asian, other), sex, and state of residence; all factors were ascertained from form CMS-2728, which is typically completed by staff in dialysis facilities.

In each epidemiologic week, we measured the incidence of COVID-19 hospitalization, all-cause mortality, and non-COVID-19 hospitalization. We focused on these outcomes for three reasons. First, COVID-19 hospitalization was the only direct measure of COVID-19 infection in REMIS data. Second, all-cause mortality facilitated estimation of the effect of COVID-19 without concern for coding quality; form CMS-2746 did not include specific codes to document COVID-19 as a cause of death until late April. Third, for the sake of contrast, hospitalization for reasons other than COVID-19 offered a window into an alternative systemic mechanism for excess mortality.

Incidence of death was measured among all patients with ESKD, whereas incidence of hospitalization was measured only among patients on dialysis with Medicare coverage. For death, we measured whether death occurred during the week. Among patients undergoing dialysis during weeks 13–27 of 2020, we identified COVID-19 deaths, as defined by submission of the ESKD Death Notification with primary cause of death code 105 (COVID-19, virus identified); 106 (COVID-19, virus not identified); or 98 (other cause of death), in tandem with a text string including “COVID.” For hospitalization outcomes, we measured whether ≥1 admission occurred during the week, on the basis of Medicare claims; we ignored whether patients were already hospitalized at the beginning of the week. A COVID-19 hospitalization was established by either a principal or secondary discharge diagnosis of COVID-19, as evidenced by International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition, Clinical Modification diagnosis code U07.1 (COVID-19, virus identified) with date of admission on or after February 16, 2020, or International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition, Clinical Modification diagnosis code B97.29 (other coronavirus as the cause of diseases classified elsewhere) with date of admission between March 8 and April 4, 2020.13 Per CMS policy, diagnosis code U07.1 was recorded on claims with dates of discharge on or after April 1 (week 14), although corresponding dates of admission among patients on dialysis occurred as early as middle February.14 Diagnosis code B97.29 is long-standing and nonspecific, but per CMS reports, use of the code spiked during late March, before the use of diagnosis code U07.1 was allowed, justifying its use here.15 Unlike in other Medicare claims datasets, data in REMIS do not distinguish between principal and secondary discharge diagnoses. A non-COVID-19 hospitalization was established by the absence of diagnosis code U07.1 and, between March 8 and April 4, the absence of diagnosis code B97.29.

We summarized demographic characteristics in week 3 of 2017–2019 and 2020; for 2017–2019, we calculated an arithmetic mean of characteristic distributions in 2017, 2018, and 2019. We summarized characteristics only in week 3 because the demography of the ESKD population is relatively stable during a 4-year interval. For COVID-19 hospitalization, we calculated crude rates during weeks 8–27 of 2020, and during 5-week intervals therein, overall and within strata defined by age, race/ethnicity, sex, and dialysis modality. We estimated adjusted relative rates (ARRs) of COVID-19 hospitalization among patients on dialysis with Medicare coverage during weeks 13–17, 18–22, and 23–27, using generalized estimating equations with a Poisson-distributed response, a log link function, and an exchangeable working correlation matrix. Age, race/ethnicity, sex, and dialysis modality were included as independent factors. To assess secular trends in ARRs, the model was refit within each 5-week interval.

For mortality and non-COVID-19 hospitalization, we calculated crude rates during weeks 3–27 of 2017–2020, and during 5-week intervals therein, both overall and within strata defined by demographic characteristics. For mortality, we estimated ARRs of death during weeks 13–27 of 2020 versus 2017–2019, using the same modeling approach as for COVID-19 hospitalization, but with only demographic characteristics as independent factors. We fit the model separately in patients undergoing dialysis and patients with a functioning transplant, and we added interaction effects to estimate ARRs within strata. For non-COVID-19 hospitalization among patients on dialysis with Medicare coverage, we estimated ARRs during weeks 13–27 of 2020 versus 2017–2019, using the same modeling approach as for COVID-19 hospitalization; ARRs in weeks 13–17, 18–22, and 23–27 were estimated by adding an interaction of era (2020 versus 2017–2019) and 5-week interval.

We also compared outcomes among patients with ESKD during the first half of 2020 with concurrent outcomes in the general population. First, during weeks 10–27 of 2020, we compared weekly rates of COVID-19 hospitalization among patients on dialysis with Medicare coverage and weekly rates in the general population of the 14 states included in the COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network, a population-based surveillance system that collects data concerning laboratory-confirmed COVID-19–associated hospitalizations in a network of over 250 acute care hospitals.16 Second, we compared relative rates of death among patients undergoing dialysis during weeks 13–17, 18–22, and 23–27 of 2020 versus 2017–2019 with concurrent ratios of expected versus observed deaths in the general population, according to weekly counts estimated by the National Center for Health Statistics.17 Due to small numbers of deaths of patients on dialysis in some states and the goal of using a common statistical approach in all 50 states, we used the same modeling approach as for COVID-19 hospitalization, but without adjustment for age, race, sex, and dialysis modality. Finally, we compared unadjusted RRs of death among patients with a functioning transplant during weeks 13–27 of 2020 versus 2017–2019 with concurrent ratios of expected versus observed deaths in the general population.

Data were accessed under the auspices of a data-use agreement with CMS and research was approved by the institutional review board at the Hennepin Healthcare Research Institute (Minneapolis, MN). All analyses were executed in SAS, version 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

In 2020 week 3, there were 568,533 patients receiving dialysis and 237,746 patients with a functioning transplant in the United States. Among those receiving dialysis, 55% had Medicare coverage; in that subgroup, 10% performed PD. In strata defined by either kidney replacement therapy or dialysis modality, distributions of age, race, and sex in 2020 were not different than corresponding distributions in 2017–2019 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics in epidemiologic wk 3 of 2017–2020, among all patients with ESKD, stratified by kidney replacement therapy, and among patients on dialysis with Medicare coverage, stratified by dialysis modality

| Characteristic | All Patients with ESKD | Patients on Dialysis with Medicare Coverage | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dialysis | Transplant | HD | PD | |||||

| 2017–2019 | 2020 | 2017–2019 | 2020 | 2017–2019 | 2020 | 2017–2019 | 2020 | |

| Sample size (n) | 537,379 | 568,533 | 218,713 | 237,746 | 287,459 | 280,433 | 28,622 | 30,695 |

| Age, yr (%) | ||||||||

| 18–44 | 12.2 | 11.7 | 21.3 | 20.7 | 10.5 | 10.2 | 16.3 | 15.3 |

| 45–64 | 41.0 | 40.0 | 49.6 | 48.4 | 39.9 | 39.4 | 40.9 | 39.6 |

| 65–74 | 25.9 | 26.6 | 22.2 | 23.4 | 27.4 | 28.0 | 26.3 | 27.3 |

| ≥75 | 21.0 | 21.7 | 6.9 | 7.6 | 22.2 | 22.4 | 16.5 | 17.9 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 38.8 | 38.8 | 48.7 | 48.0 | 40.2 | 40.9 | 54.5 | 55.0 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 32.5 | 31.9 | 19.7 | 20.2 | 35.3 | 34.9 | 23.9 | 23.3 |

| Hispanic | 18.6 | 19.3 | 14.1 | 14.8 | 15.3 | 15.5 | 12.9 | 13.3 |

| Asian | 4.7 | 5.0 | 4.6 | 4.9 | 4.0 | 4.2 | 5.7 | 5.7 |

| Other/unknown | 5.5 | 5.1 | 12.9 | 12.1 | 5.2 | 4.6 | 3.0 | 2.8 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 42.7 | 42.2 | 40.5 | 40.6 | 44.1 | 43.5 | 45.4 | 44.8 |

| Male | 57.3 | 57.8 | 59.5 | 59.4 | 55.9 | 56.5 | 54.6 | 55.2 |

Statistics in 2017–2019 columns reflect means of corresponding statistics in epidemiologic wk 3 of 2017, 2018, and 2019.

COVID-19 Hospitalization

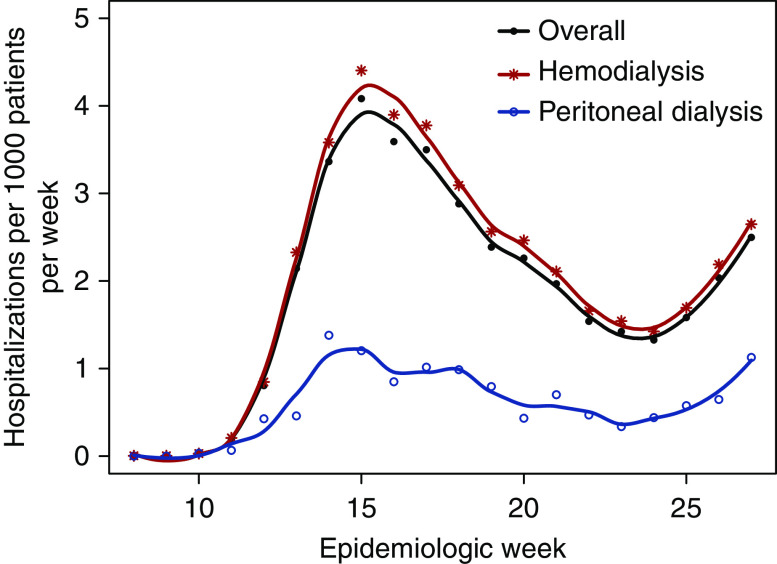

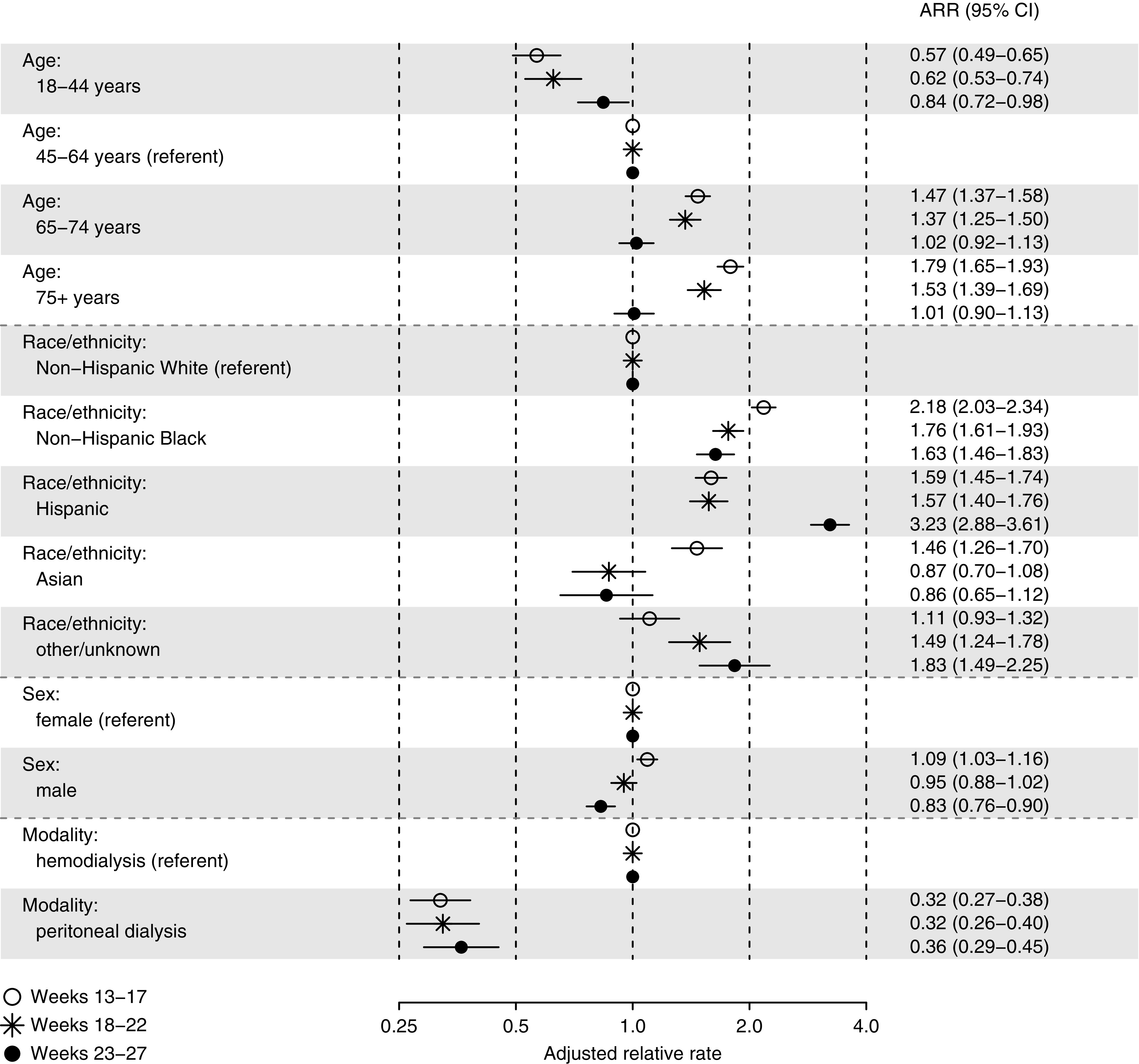

Among patients on dialysis with Medicare coverage, the rate of COVID-19 hospitalization increased sharply between weeks 11 and 15, declined through week 24, and rebounded afterward (Figure 1). In almost all subgroups, crude rates of COVID-19 hospitalization peaked during weeks 13–17; the exception was Hispanic patients, in whom rates peaked during weeks 23–27 (Supplemental Table 1). Before adjustment, older age and Asian race were associated with higher rates during weeks 13–17, but not weeks 23–27; male sex was associated with lower rates during weeks 23–27, but not weeks 13–17; and both non-Hispanic Black race and Hispanic ethnicity were consistently associated with higher rates. After adjustment, both non-Hispanic Black race (ARRs, 1.6–2.2) and Hispanic ethnicity (ARRs, 1.6–3.2), each relative to non-Hispanic White race, were consistently associated with higher risk during weeks 13–27 (Figure 2). In contrast, PD was associated with lower risk than HD (ARRs, 0.3–0.4). Although age 18–44 years was also associated with lower risk than age 45–64 years, the magnitude of the association attenuated as time elapsed.

Figure 1.

Weekly rate of COVID-19 hospitalization during epidemiologic weeks 8–27 of 2020 among patients on dialysis with Medicare coverage, overall and by modality.

Figure 2.

ARRs of COVID-19 hospitalization during epidemiologic weeks 13–27 of 2020, by 5-week intervals, among patients on dialysis with Medicare coverage. Referent categories include age 45–64 years, non-Hispanic White race, female sex, and HD.

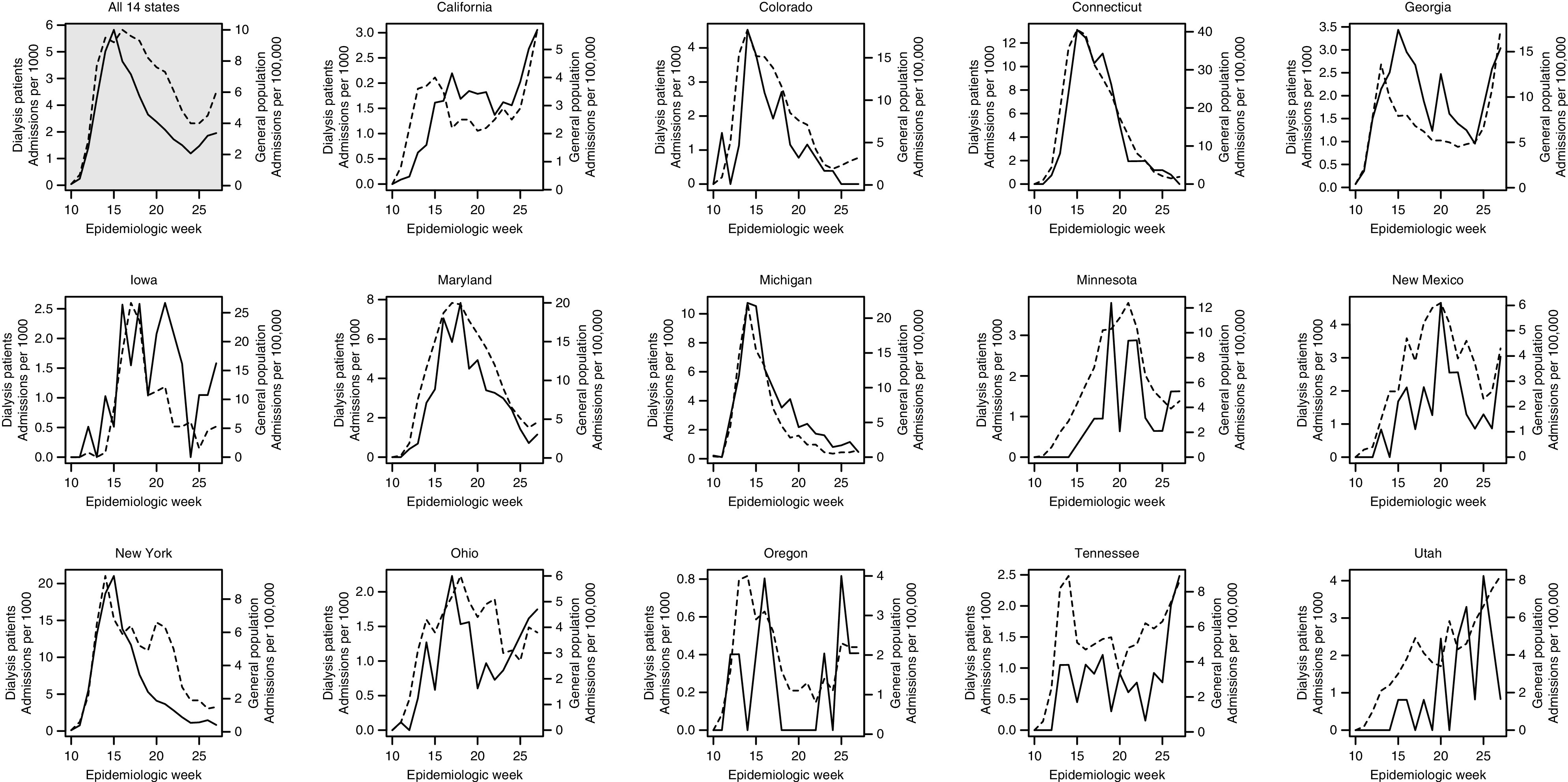

Among 14 states included in COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network, the temporal association of weekly rates of COVID-19 hospitalization among patients on dialysis with Medicare coverage and corresponding rates in the general population was high, although rates among patients on dialysis were roughly 40 times higher than rates in the general population (Figure 3). Among all 14 states, the correlation of weekly rates among patients on dialysis and in the general population was 0.90 during weeks 10–27; within states, the median correlation was 0.72, with a range from 0.49 to 0.95.

Figure 3.

Weekly rates of COVID-19 hospitalization during epidemiologic weeks 8–27 of 2020 among patients on dialysis with Medicare coverage and in the general population of 14 states participating in the COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network. In each panel, the rate among patients on dialysis is depicted with a solid line and measured by the left vertical axis, whereas the rate in the general population is depicted with a dashed line and measured by the right vertical axis.

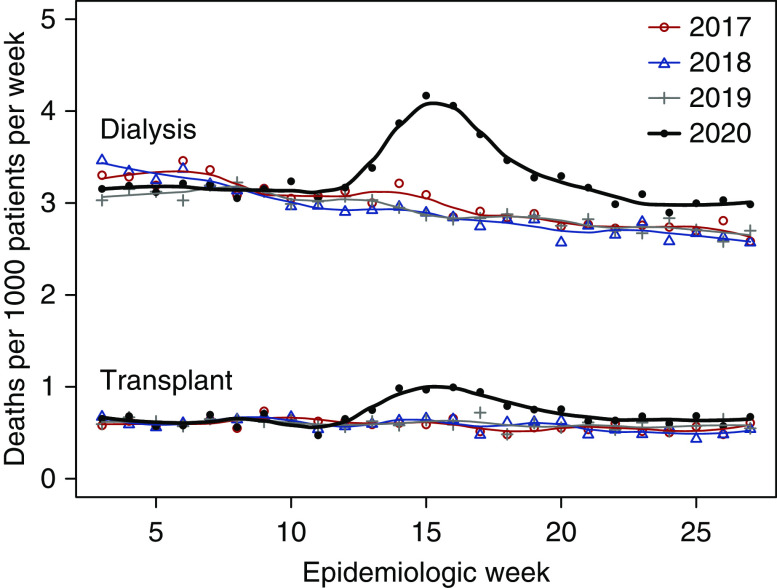

All-Cause Mortality

Among all patients undergoing dialysis, rates of all-cause mortality followed a consistent seasonal trend in weeks 3–27 of 2017–2019. During 2020, rates followed the same trend in weeks 3–12 but diverged upward thereafter (Figure 4, Supplemental Table 2). During weeks 13–27, there were a total of 28,670 deaths, of which 25,839 (90.1%) were documented by submission of the ESKD Death Notification. The percentage of deaths primarily caused by COVID-19 rapidly increased from 2.6% in week 13 to 13.0% in week 18, and subsequently receded to a range of 4.0%–5.0% during weeks 25–27.

Figure 4.

Weekly rates of death during epidemiologic weeks 3–27 of 2017–2020 among all patients with ESKD, stratified by kidney replacement therapy.

In weeks 13–27, the ARR of death among all patients undergoing dialysis during 2020 versus 2017–2019 was 1.17 (95% CI, 1.16 to 1.19). Within demographic strata (except for other/unknown race/ethnicity), ARRs ranged from 1.07 to 1.35; ARRs were higher in younger versus older patients, and in non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and Asian patients, each relative to White patients (Table 2). Among patients with a functioning transplant, mortality rate patterns were similar (Figure 4, Supplemental Table 3). In weeks 13–27, the ARR of death during 2020 versus 2017–2019 was 1.30 (95% CI, 1.24 to 1.36). Within demographic strata (except for other/unknown race/ethnicity), ARRs ranged from 1.20 to 1.90. As was observed among patients undergoing dialysis, ARRs were relatively higher in non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic patients with a functioning transplant.

Table 2.

ARRs of death during epidemiologic wk 13–27 of 2020 versus 2017–2019 among all patients with ESKD, within strata defined by demographic characteristics and kidney replacement therapy

| Characteristic | Dialysis | Transplant | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARR | 95% CI | ARR | 95% CI | |

| All patients | 1.17 | (1.16 to 1.19) | 1.30 | (1.24 to 1.36) |

| Age (yr) | ||||

| 18–44 | 1.24 | (1.15 to 1.33) | 1.35 | (1.10 to 1.65) |

| 45–64 | 1.23 | (1.20 to 1.26) | 1.37 | (1.27 to 1.48) |

| 65–74 | 1.16 | (1.13 to 1.19) | 1.29 | (1.20 to 1.39) |

| 75+ | 1.14 | (1.11 to 1.16) | 1.20 | (1.09 to 1.32) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-hispanic White | 1.07 | (1.05 to 1.09) | 1.20 | (1.12 to 1.28) |

| Non-hispanic Black | 1.35 | (1.32 to 1.39) | 1.84 | (1.67 to 2.03) |

| Hispanic | 1.27 | (1.23 to 1.32) | 1.90 | (1.67 to 2.17) |

| Asian | 1.28 | (1.20 to 1.38) | 1.38 | (1.07 to 1.77) |

| Other/unknown | 1.01 | (0.94 to 1.08) | 0.76 | (0.67 to 0.86) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 1.16 | (1.13 to 1.18) | 1.24 | (1.15 to 1.33) |

| Male | 1.19 | (1.17 to 1.21) | 1.33 | (1.26 to 1.41) |

Excess mortality was highest during weeks 13–17: ARRs of death in 2020 versus 2017–2019 were 1.29 (95% CI, 1.26 to 1.32) and 1.48 (95% CI, 1.38 to 1.59) among patients undergoing dialysis and with a functioning transplant, respectively (Table 3). Within states, the median correlation of excess mortality, by 5-week intervals, among patients undergoing dialysis and in the general population was 0.61 (Supplemental Figure 1). Correlations were >0.9 in 12 states, and in the Middle Atlantic, correlations were >0.99 in New Jersey, 0.97 in New York, and 0.36 in Pennsylvania. The correlation of per-state excess mortality during weeks 13–27 among patients with a functioning transplant and in the general population was 0.39 (Supplemental Figure 2).

Table 3.

Per-interval ARRs of death during epidemiologic wk 13–27 of 2020 versus 2017–2019 among all patients with ESKD, stratified by kidney replacement therapy

| Epidemiologic Wks | Dialysis | Transplant | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARR | 95% CI | ARR | 95% CI | |

| 13–17 | 1.29 | (1.26 to 1.32) | 1.48 | (1.38 to 1.59) |

| 18–22 | 1.14 | (1.12 to 1.17) | 1.23 | (1.14 to 1.34) |

| 23–27 | 1.09 | (1.07 to 1.12) | 1.16 | (1.06 to 1.26) |

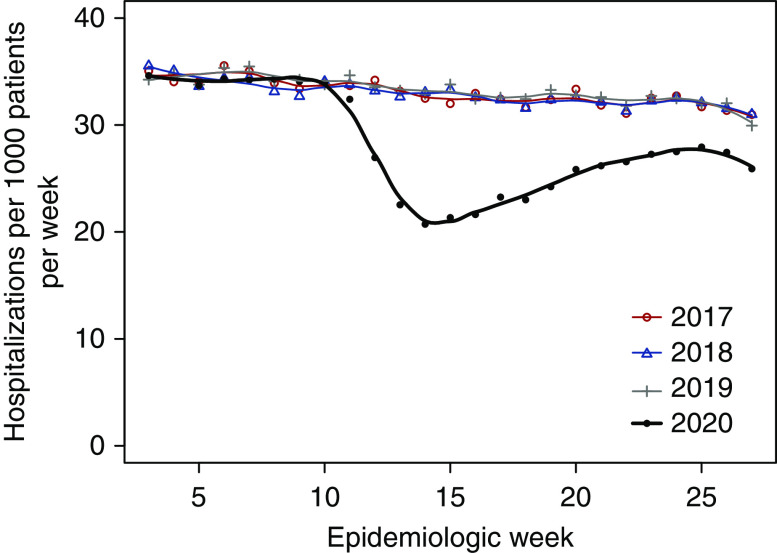

Non–COVID-19 Hospitalization

In contrast to rates of all-cause mortality, rates of non–COVID-19 hospitalization among patients on dialysis with Medicare coverage diverged downward in 2020, beginning in week 11; the non–COVID-19 hospitalization rate reached its minimum in week 14 (March 29 to April 4) and partially rebounded toward historic norms afterward (Figure 5). In weeks 13–17, the overall rate was 21.9 hospitalizations per 1000 patients during 2020 versus 32.8 hospitalizations per 1000 patients during 2017–2019 (Supplemental Table 4). In weeks 13–27, the ARR of hospitalization during 2020 versus 2017–2019 was 0.83 (95% CI, 0.82 to 0.83); within demographic strata, ARRs were similar. As crude rates suggested, ARRs of non–COVID-19 hospitalization during 2020 versus 2017–2019 attenuated during the spring: 0.76 (95% CI, 0.75 to 0.77) in weeks 13–17, 0.88 (95% CI, 0.87 to 0.89) in weeks 18–22, and 0.95 (95% CI, 0.94 to 0.96) in weeks 23–27.

Figure 5.

Weekly rates of non–COVID-19 hospitalization during epidemiologic weeks 3–27 of 2017–2020 among patients on dialysis with Medicare coverage.

Discussion

Patients with ESKD constitute a highly vulnerable subset of people with underlying medical conditions. The effects of COVID-19 on these patients appear to have been profound. Among patients undergoing dialysis during the first half of 2020, the rate of COVID-19 hospitalization peaked between March 22 and April 25. During that interval, all-cause mortality among patients on dialysis or with a transplant was 29% and 48% higher, respectively, than during the same 5 weeks in preceding years. Excess mortality persisted throughout the spring. Perhaps most surprisingly, the rate of hospitalization for reasons other than COVID-19 declined sharply among patients undergoing dialysis in the spring—after having been nearly constant since 2013.

Unsurprisingly, the trajectory of COVID-19 hospitalization rates in patients undergoing dialysis during the spring mirrored the trajectory in the general population.18 However, the array of factors associated with risk of COVID-19 hospitalization was complex. Older age was initially associated with higher risk, but there was little heterogeneity in risk among patients aged ≥45 years in June, raising the question of whether age might reflect not only biologic risk, but also behavioral response to community spread.19 Even in a population whose members all have high risk of severe COVID-19, non-Hispanic Black patients had hospitalization rates that were 60%–120% higher than non-Hispanic White patients, whereas Hispanic patients had rates that were 60%–220% higher than non-Hispanic White patients. The disparities highlight the troubling racial and ethnic inequities that have characterized COVID-19 in the United States.20 Roughly 60% of Black patients receive dialysis in facilities located in postal codes where Blacks constitute a median of 34% of the general population, suggesting that location, not race per se, may be a key risk factor.21 Finally, PD was associated with much lower risk of hospitalization than HD. PD occurs in the home setting, with only monthly visits in the clinic, reducing the exposure risks that are inherent with in-facility HD, including medical transport, dialysis facility staff, and fellow patients on dialysis—some of whom reside in skilled nursing facilities. Nevertheless, other studies about COVID-19 outcomes in PD and home HD patients have produced conflicting findings.22–24

Death rates among patients with ESKD were relatively high before COVID-19 emerged. Among people aged 66–74 years, death rates are 10–15 times higher among patients treated with dialysis and 2.5–3.5 times higher among those with a transplant, relative to the Medicare beneficiary population.1 COVID-19 has clearly worsened mortality further. Excess mortality among transplant patients in 2020, relative to preceding years, was higher than among patients on dialysis, despite the (relative) ability of transplant patients to shelter during the pandemic. The highest levels of excess mortality during the spring were observed among non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and Asian patients, again highlighting the inequitable effect of COVID-19 on people of color, regardless of kidney replacement therapy. As COVID-19 hospitalization rates declined, excess mortality attenuated, but even in June, mortality was 9% and 16% higher among those treated with dialysis and with a transplant, respectively, relative to preceding years. The net result of this is an unprecedented decline in the number of people with ESKD: between the ends of the first and second quarters of 2020, the ESKD census declined by 0.4%.25 This decline will reverberate through capacity and financial forecasts of dialysis providers and CMS.

Although it is now well known that inpatient care of the general population was disrupted during the spring of 2020,26 it may be assumed that the hospitalization rate of patients on dialysis was stable, considering that the incidence of severe complications related to volume overload and infection would not be altered by COVID-19. However, from March 22 to April 25, the hospitalization rate of patients on dialysis declined by 24% in 2020, as compared with 2017–2019. At least three narratives are possible. One suggests that patients with ESKD lacked usual access to acute care, thus contributing to excess mortality. Another suggests that those undergoing in-facility HD missed fewer treatment sessions during the spring, in a putatively successful attempt to minimize risk of hospitalization and accompanying risk of COVID-19 infection. A third narrative suggests that almost all excess mortality was directly attributable to COVID-19 infection, generating the hypothesis that “missing” hospitalizations were not truly necessary to satisfactorily address usual complications. Because CMS expends over $28,000 per patient-year on inpatient care for patients receiving dialysis,1 future studies should aim to resolve which narrative is most likely true.

Although COVID-19 has surged for a third time during late fall and early winter 2020, mortality among patients with ESKD has probably increased again. Aside from the care of infected patients, the most pressing issue now is COVID-19 vaccination. On December 20, 2020, the Advisory Committee on Vaccination Practices recommended that phase 1b of vaccination include all adults aged ≥75 years—roughly 21% of adult patients undergoing dialysis and 7% of those with a transplant—and phase 1c include all adults aged 65–74 years and adults aged 16–64 years with underlying medical conditions—presumably subsuming all remaining patients with ESKD.27 Phase 1c includes roughly 130 million people.27 Although the efficacy of vaccination in patients with ESKD has not been established by randomized clinical trials, our findings suggest that prioritization of patients with ESKD among those 130 million should be seriously considered by state governments. In fact, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Maine, and Minnesota have already allocated vaccine supply to dialysis-provider organizations.28 Future studies should measure both vaccine uptake and vaccine effectiveness in patients with ESKD.

This study has several limitations. First, hospitalization outcomes were assessed among patients on dialysis with Medicare-fee-for-service coverage. Patients on dialysis who were enrolled in Medicare Advantage or carried private insurance were excluded, as were patients with a kidney transplant. Many subgroups of the excluded population will be accessible for analysis in the future, when final-action claims are released. Second, associations of demographic factors with COVID-19 hospitalization risk were not adjusted for comorbid conditions, due to the absence of outpatient (e.g., physician office) claims with diagnosis codes. The risk contrast of PD versus HD may be particularly sensitive to unmeasured confounding. Although adjustment for age tends to resolve much of the comorbidity imbalance between the dialysis modalities, unmeasured differences in health-seeking behavior, housing stability, and social support may account for some of the observed difference in COVID-19 hospitalization risk. Third, outcome data were slightly incomplete. Epidemiologic week 27 ended on July 4, 2020, and REMIS data were extracted on September 30. On the basis of a series of five quarterly extracts of REMIS data, we estimated that cumulative numbers of deaths and hospitalizations during the second quarter of 2020 were negatively biased by 1.5% and 2.7%, respectively. Considering the magnitude of ARRs of death and non–COVID-19 hospitalization during 2020 versus 2017–2019, these bias parameters do not alter conclusions about population-level effects of COVID-19. Fourth, data in REMIS have inherent limitations, as they lack the richness of other Medicare claims datasets. We could not identify COVID-19 testing, telehealth utilization, or skilled nursing facility care. We relied on COVID-19 hospitalization as a direct measure of disease incidence, but hospitalization practices themselves likely changed as the pandemic unfolded: as hospitals reached capacity, the threshold for admitting clinically stable patients with COVID-19 likely increased. Nevertheless, our findings paint a detailed picture of available data from the initial phase of the pandemic.

Left unidentified by this study are the dominant mechanisms of COVID-19 transmission. It is likely that outbreaks in skilled nursing facilities and nursing homes contributed to high rates of COVID-19 hospitalization among patients undergoing dialysis, considering that 15% of all patients on dialysis annually receive care in such facilities. However, it is striking that per-state rates of COVID-19 hospitalization were so highly correlated with corresponding rates in the general population, suggesting that community transmission of COVID-19 may overwhelm infection control practices inside dialysis facilities. Although precise identification of COVID-19 transmission mechanisms is beyond the scope of this study or any other retrospective analysis, effort should be expended to assess whether relatively disruptive practices, such as cohort patients on in-facility HD with COVID-19, were associated with improved outcomes.

Patients with ESKD were severely affected by COVID-19 during the first half of 2020, to the extent that excess mortality in patients on dialysis and with a transplant led to contraction of the ESKD census. Racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19 hospitalization and excess mortality further demonstrated the health inequities that have been widely discussed during 2020. Although data from patients performing PD at home suggest potential risk modification, the dominant aspects of ESKD care today are in-facility HD and transplant-related immunosuppression. Vaccination may be the only intervention that can significantly stem morbidity and mortality.

Disclosures

D. Gilbertson reports having a consulting relationship with Amgen, providing general input in epidemiologic and biostatistical research; reports consultancy agreements with Amgen; reports receiving research funding from Acadia, Amgen, AstraZeneca, DaVita, Genentech, Gilead, HRSA, Merck, National Institutes of Health, and Opko Renal. E. Weinhandl reports a consulting relationship with Fresenius Medical Care North America, providing input in epidemiologic research about home dialysis; reports being employed by NxStage Medical and Fresenius Medical Care North America (after the acquisition of NxStage Medical) between March 2016 and April 2020; and reports being scientific advisor or member via the Advisory Board of Home Dialyzors United, and the Board of Directors of the Medical Education Institute; and reports having other interests/relationships on the Scientific Methods Panel for the National Quality Forum. J. Wetmore reports participation in advisory boards of Aurinia Pharmaceuticals, OPKO Health, and Reata Pharmaceuticals; reports receiving honoraria for academic continuing medical education from Healio and NephSAP; reports consultancy agreements via ad hoc consulting for Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS)-Pfizer Alliance; reports receiving research funding from Amgen, AstraZeneca, BMS/Pfizer, Genentech, Merck, and OPKO Health; reports receiving honoraria from BMS-Pfizer Alliance (for advisory board activities, as noted below); reports being a scientific advisor or member with BMS-Pfizer Alliance, and occasional participate on ad hoc advisory boards. K. Johansen reports participation in the steering committee of Anemia Studies in Chronic Kidney Disease (ASCEND), a clinical trial program evaluating the efficacy and safety of daprodustat and supported by GlaxoSmithKline; because K. Johansen is an editor of the JASN, she was not involved in the peer review process for this manuscript. A guest editor oversaw the peer review and decision-making process for this manuscript. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

The data reported here have been supplied by the United States Renal Data System (USRDS), which is funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) through contract 75N94019C00006.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was completed by the USRDS Coordinating Center, as part of its contract with the NIDDK. The originally submitted manuscript was approved by NIDDK contracting officer representatives, Dr. Kevin Abbott, and Dr. Kevin Chan. The NIDDK had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation, or writing of the report. The USRDS Coordinating Center is located at the Chronic Disease Research Group, a division of the Hennepin Healthcare Research Institute in Minneapolis, MN. The USRDS director is K.L. Johansen, the deputy director is J. B. Wetmore, and the project director is D.T. Gilbertson. D.T. Gilbertson, K.L. Johansen, J. Liu, E.D. Weinhandl, and J.B. Wetmore designed the study; Y. Peng acquired and processed the data; E. D. Weinhandl analyzed the data; and K.L. Johansen, Y. Peng, E.D. Weinhandl, and J.B. Wetmore drafted and revised the article. All authors approved the final version of the article.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Data Sharing Statement

The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the US Government.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2021010009/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Weekly rates of COVID-19 hospitalization during epidemiologic weeks 8–27 of 2020, by 5-week intervals, among patients on dialysis with Medicare coverage.

Supplemental Table 2. Weekly rates of death during epidemiologic weeks 3–27 of 2017–2020 among all patients with ESKD undergoing dialysis.

Supplemental Table 3. Weekly rates of death during epidemiologic weeks 3–27 of 2017–2020 among all patients with ESKD with a functioning transplant.

Supplemental Table 4. Weekly rates of non–COVID-19 hospitalization during epidemiologic weeks 3–27 of 2017–2020 among patients on dialysis with Medicare coverage.

Supplemental Figure 1. Per-interval relative rates of death during epidemiologic weeks 13–27 of 2020 versus 2017–2019 among all patients with ESKD undergoing dialysis and per-interval ratios of observed versus expected deaths in the general population, stratified by state.

Supplemental Figure 2. Relative rates of death during epidemiologic weeks 13–27 of 2020 versus 2017–2019 among all patients with ESKD with a functioning transplant and ratios of observed versus expected deaths in the general population, by state.

References

- 1. United States Renal Data System : 2020 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2020. Available at: https://adr.usrds.org/2020. Accessed March 18, 2021

- 2. Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, Bacon S, Bates C, Morton CE, et al.: Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 584: 430–436, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Oetjens MT, Luo JZ, Chang A, Leader JB, Hartzel DN, Moore BS, et al.: Electronic health record analysis identifies kidney disease as the leading risk factor for hospitalization in confirmed COVID-19 patients. PLoS One 15: e0242182, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Dialysis facility reports for fiscal year, 2020. Available at: https://data.cms.gov/dialysis-facility-reports. Accessed December 22, 2020

- 5. Garrity BH, Kramer H, Vellanki K, Leehey D, Brown J, Shoham DA: Time trends in the association of ESRD incidence with area-level poverty in the US population. Hemodial Int 20: 78–83, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Azzi Y, Bartash R, Scalea J, Loarte-Campos P, Akalin E: COVID-19 and solid organ transplantation: A review article. Transplantation 105: 37–55, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bell S, Campbell J, McDonald J, O’Neill M, Watters C, Buck K, et al.; Scottish Renal Registry: COVID-19 in patients undergoing chronic kidney replacement therapy and kidney transplant recipients in Scotland: Findings and experience from the Scottish renal registry. BMC Nephrol 21: 419, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jager KJ, Kramer A, Chesnaye NC, Couchoud C, Sánchez-Álvarez JE, Garneata L, et al.: Results from the ERA-EDTA Registry indicate a high mortality due to COVID-19 in dialysis patients and kidney transplant recipients across Europe. Kidney Int 98: 1540–1548, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Savino M, Casula A, Santhakumaran S, Pitcher D, Wong E, Magadi W, et al.: Sociodemographic features and mortality of individuals on haemodialysis treatment who test positive for SARS-CoV-2: A UK Renal Registry data analysis. PLoS One 15: e0241263, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hilbrands LB, Duivenvoorden R, Vart P, Franssen CFM, Hemmelder MH, Jager KJ, et al.; ERACODA Collaborators: COVID-19-related mortality in kidney transplant and dialysis patients: Results of the ERACODA collaboration. Nephrol Dial Transplant 35: 1973–1983, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fisher M, Yunes M, Mokrzycki MH, Golestaneh L, Alahiri E, Coco M: Chronic hemodialysis patients hospitalized with COVID-19: Short-term outcomes in the Bronx, New York. Kidney360 1: 755–762, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Flythe JE, Assimon MM, Tugman MJ, Chang EH, Gupta S, Shah J, et al.: Characteristics and outcomes of individuals with pre-existing kidney disease and COVID-19 admitted to intensive care units in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 77: 190–203.e1, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kadri SS, Gundrum J, Warner S, Cao Z, Babiker A, Klompas M, et al.: Uptake and accuracy of the diagnosis code for COVID-19 among US hospitalizations. JAMA 324: 2553–2554, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Update to the international classification of diseases, tenth revision (ICD-10) diagnosis codes for vaping related disorder and diagnosis and procedure codes for the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Available at: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/mm11623.pdf. Accessed December 22, 2020

- 15. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Preliminary Medicare COVID-19 data snapshot. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-systems/preliminary-medicare-covid-19-data-snapshot. Accessed February 26, 2021

- 16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: COVID-NET. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/covid-net/purpose-methods.html. Accessed February 26, 2021

- 17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Excess deaths associated with COVID-19. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/covid19/excess_deaths.htm. Accessed February 26, 2021

- 18. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: COVIDView. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/covidview/index.html. Accessed December 22, 2020

- 19. Kim JK, Crimmins EM: How does age affect personal and social reactions to COVID-19: Results from the national Understanding America Study. PLoS One 15: e0241950, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mackey K, Ayers CK, Kondo KK, Saha S, Advani SM, Young S, et al.: Racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19-related infections, hospitalizations, and deaths : A systematic review. Ann Intern Med 174[3]: 362–373, 2021. 10.7326/M20-6306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Golestaneh L, Cavanaugh KL, Lo Y, Karaboyas A, Melamed ML, Johns TS, et al.: Community racial composition and hospitalization among patients receiving in-center hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 76: 754–764, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maldonado M, Ossorio M, Del Peso G, Santos C, Álvarez L, Sánchez-Villanueva R, et al.: COVID-19 incidence and outcomes in a home dialysis unit in Madrid (Spain) at the height of the pandemic [published online ahead of print November 5, 2020]. Nefrologia 10.1016/j.nefro.2020.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Michel PA, Piccoli GB, Couchoud C, Fessi H: Home hemodialysis during the COVID-19 epidemic: Comment on the French experience from the viewpoint of a French home hemodialysis care network. J Nephrol 33: 1125–1127, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Couchoud C, Bayer F, Ayav C, Béchade C, Brunet P, Chantrel F, et al.; French REIN registry: Low incidence of SARS-CoV-2, risk factors of mortality and the course of illness in the French national cohort of dialysis patients. Kidney Int 98: 1519–1529, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. United States Renal Data System: ESRD quarterly update. Available at: https://www.usrds.org/esrd-quarterly-update/. Accessed December 22, 2020

- 26. Birkmeyer JD, Barnato A, Birkmeyer N, Bessler R, Skinner J: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital admissions in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood) 39: 2010–2017, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dooling K, Marin M, Wallace M, McClung N, Chamberland M, Lee GM, et al.: The advisory committee on immunization practices’ updated interim recommendation for allocation of COVID-19 vaccine — United States, December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 69: 1657–1660, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Charnow JA: Dialysis providers push for direct allocation of COVID-19 vaccines. Renal & Urology News. February 8, 2021. Available at: https://www.renalandurologynews.com/home/news/nephrology/hemodialysis/covid-19-coronavirus-vaccination-dialysis-facilities. Accessed March 18, 2021

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.