Abstract

A major driver of the U.S. opioid crisis is limited access to effective medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) that reduce overdose risks. Traditionally, jails and prisons in the U.S. have not initiated or maintained MOUD for incarcerated individuals with OUD prior to their return to the community, which places them at high risk for fatal overdose. A 2018 law (Chapter 208) made Massachusetts (MA) the first state to mandate that five county jails deliver all FDA-approved MOUDs (naltrexone [NTX], buprenorphine [BUP], and methadone). Chapter 208 established a 4-year pilot program to expand access to all FDA-approved forms of MOUD at five jails, with two more MA jails voluntarily joining this initiative. The law stipulates that MOUD be continued for individuals receiving it prior to detention and be initiated prior to release among sentenced individuals where appropriate. The jails must also facilitate continuation of MOUD in the community on release.

The Massachusetts Justice Community Opioid Innovation Network (MassJCOIN) partnered with these seven diverse jails, the MA Department of Public Health, and community treatment providers to conduct a Type 1 hybrid effectiveness-implementation study of Chapter 208. We will: (1) Perform a longitudinal treatment outcome study among incarcerated individuals with OUD who receive NTX, BUP, methadone, or no MOUD in jail to examine postrelease MOUD initiation, engagement, and retention, as well as fatal and nonfatal opioid overdose and recidivism; (2) Conduct an implementation study to understand systemic and contextual factors that facilitate and impede delivery of MOUDs in jail and community care coordination, and strategies that optimize MOUD delivery in jail and for coordinating care with community partners; (3) Calculate the cost to the correctional system of implementing MOUD in jail, and conduct an economic evaluation from state policy-maker and societal perspectives to compare the value of MOUD prior to release from jail to no MOUD among matched controls.

MassJCOIN made significant progress during its first six months until the COVID-19 pandemic began in March 2020. Participating jail sites restricted access for nonessential personnel, established other COVID-19 mitigation policies, and modified MOUD programming. MassJCOIN adapted research activities to this new reality in an effort to document and account for the impacts of COVID-19 in relation to each aim. The goal remains to produce findings with direct implications for policy and practice for OUD in criminal justice settings.

Keywords: Opioid use disorder, Massachusetts Justice Community Opioid Innovation Network (MassJCOIN), Criminal justice settings, Buprenorphine, Methadone, Naltrexone, Medications for opioid use disorder, MOUD, Research protocol

1. Introduction

Massachusetts (MA) has been especially affected by the opioid public health crisis (Hedegaard et al., 2020), with more than 4.4% of the population estimated to have opioid use disorder (OUD) (Barocas et al., 2018), and 2,020 opioid overdose deaths in 2019 (Massachusetts Department of Public Health, 2020). In 2019, MA became the first state to mandate the availability of all FDA-approved medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) for patients with OUD (naltrexone [NTX e.g. Vivitrol®], buprenorphine [BUP e.g. Suboxone®], and methadone) in county jail settings. A 2018 law (House Bill 4742 or “Chapter 208”) established a 4-year pilot program to expand access to all FDA-approved forms of MOUD at five county Houses of Correction (HOCs, i.e. jails); two more county jails in MA voluntarily joined this initiative. The law stipulates that MOUD must be continued in individuals receiving it prior to detention, and be initiated prior to release among sentenced individuals where appropriate. These jails must also facilitate continuation of MOUD in the community upon release. The implementation of Chapter 208 will have important implications for future policy and practice in the legal and OUD treatment systems at the national, state, and local levels. Understanding the impacts of Chapter 208 is, therefore, crucial to the development of future strategies to address OUD in jail populations. The Massachusetts Justice Community Opioid Innovation Network (MassJCOIN) partnered with these jails, and its specific aims are to:

Perform a longitudinal treatment outcome study among individuals with OUD who receive NTX, BUP, methadone, or no MOUD in jail.

Conduct an implementation study to understand systemic and contextual factors that facilitate and impede delivery of MOUD in jail and community care coordination, and strategies that optimize MOUD provision and linkage to community MOUD care.

Conduct an economic evaluation to compare the cost-effectiveness of no MOUD, NTX, BUP, and methadone prior to release from jail from the local policy-maker and societal perspectives.

1.1. Conceptual framework

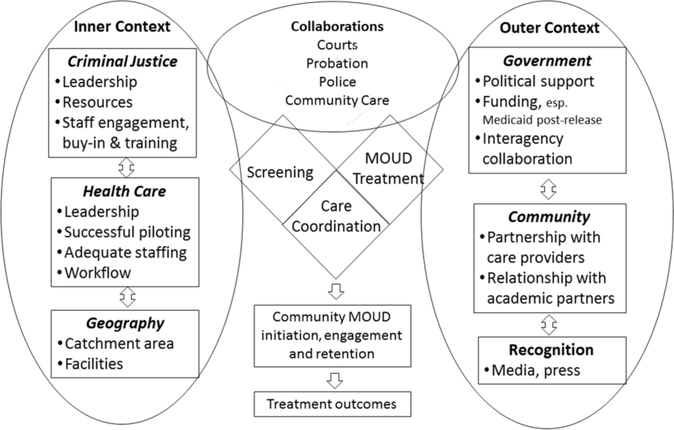

Implementation of new practices like MOUD in correctional settings (Brinkley-Rubinstein et al., 2019; Friedmann et al., 2012; Friedmann et al., 2015; Grella et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2018; Mace et al., 2019; MA Chapter 208 of the Acts of 2018; Taxman & Belenko, 2012) depends on the organizational capacity and culture of the systems to implement and sustain them (Landenberger & Lipsey, 2005; Lee et al., 2018; Lipsey, 2010). MassJCOIN is grounded in the exploration, preparation, implementation, sustainment (EPIS) framework as adapted for criminal justice settings (Aarons et al., 2011; Gleicher, 2017; Moullin et al., 2019). Building on prior work (Becan et al., 2018; Ferguson, 2018; Ferguson et al., 2019), we anticipate variation across the jails in the three core components required for successful MOUD implementation: screening, treatment (including MOUD and behavioral counseling), and care coordination with community treatment postrelease (Ferguson, 2018; Ferguson et al., 2019). We hypothesize that contextual factors and strategies will influence variability in these three core components (Fig. 1), which, in turn, will influence MOUD initiation, engagement, and retention. This framework includes the OUD treatment cascade (Guerrero et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2018, 2019), modified for jail release in which an additional stepdown and treatment gap are expected between MOUD treatment in jail and community MOUD initiation. The extent to which care coordination can bridge this gap will be a major determinant of the effectiveness of jail delivery of MOUD in improving treatment outcomes, e.g., reducing overdose and recidivism.

Fig. 1: MassJCOIN conceptual framework.

Adapted from Aarons, and Ferguson et al.

MOUD - medications for opioid use disorder

2. Methods

MassJCOIN is a partnership among academic researchers, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (MDPH), and seven HOCs to conduct a Type 1 hybrid effectiveness-implementation study of MA Chapter 208 (MA Chapter 208 of the Acts of 2018; Curran, et al., 2012). The study will be conducted over 5 years, and started September 1, 2019.

2.1. Aim 1: An MOUD treatment outcome study in Massachusetts jails

2.1.1. Overall design.

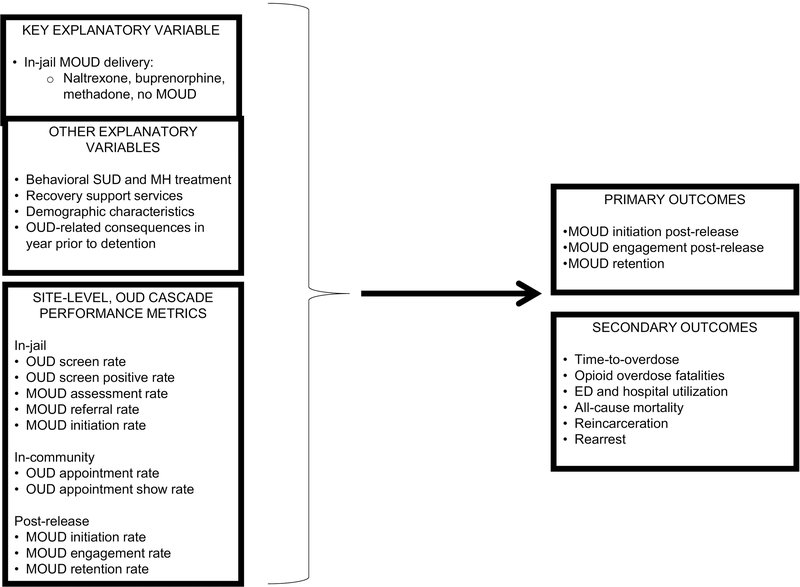

We will conduct a quasi-experimental, comparative effectiveness, treatment outcome study that leverages the innovative Public Health Data Warehouse (PHD) developed and managed by the MDPH (Gordon et al., 2012, 2014; Lee et al., 2018; Magura et al., 2009; Zaller et al., 2013). The PHD is an innovative analytic environment that the MDPH developed and maintains; it draws on multi-sector data to answer critical public health questions while ensuring data security and individual privacy. It operates under the authority of Massachusetts General Laws (M.G.L.) Chapter 111, §237, which allows for the analysis of population health trends focusing on opioids as well as other health priorities that the MDPH Commissioner determins. Within the PHD, we will identify the approximately 7,500 incarcerated persons with OUD released from the seven participating jails during the first 18 months of the project, whether they received MOUD during their incarceration, and if treated, which MOUD type (NTX, BUP, or methadone) they received. The data received from the PHD during the last year of the project will allow assessment of the outcomes associated with receipt of MOUD and MOUD type during the year after community reentry. We will also assess treatment outcomes in relation to variability in site-level implementation practices across sites (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: MassJCOIN treatment outcome study.

ED – emergency department

MH – mental health

MOUD - medications for opioid use disorder

OUD – opioid use disorder

SUD – substance use disorder

2.1.2. Hypotheses.

Initial analyses will examine whether longitudinal treatment outcomes among incarcerated persons with OUD vary by receipt of MOUD in jail and MOUD type. We hypothesize that incarcerated persons with OUD who initiate MOUD in jail will…

H1. …be more likely to utilize MOUD postrelease in the community (initiation, engagement, and retention) than those who do not initiate in jail [primary outcome].

H2. …be less likely to overdose and die, and will take more time to do so, compared to those who do not initiate in jail [secondary outcome].

H3. …be less likely to recidivate (rearrest, reincarceration), and will take more time to do so, compared to those who do not initiate in jail [secondary outcome].

H4. …experience varied outcomes by MOUD type.

We will utilize aggregated site-level variables that model the OUD Care Cascade (Guerrero et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2018, 2019; Fig. 2) to examine hypotheses about site-level care. For example, better postrelease primary outcomes will be associated with…

H5. …a higher jail MOUD initiation rate,

H6. …comprehensive and responsive services provision (e.g., MOUD plus behavioral counseling), and

H7. …care coordination with community treatment postrelease (e.g., patient navigators). Such practices will be associated with better postrelease MOUD utilization in the community (MOUD initiation and retained in MOUD beyond 6 months) which, in turn, will be associated with better long-term treatment outcomes (e.g., lower rates of overdose, recidivism, and death).

2.1.3. Study population.

Eligible subjects will be identified within the PHD as being (1) released from one of the seven Chapter 208 pilot jails between the start date for the Chapter 208 pilot in that jail (between April 1 and September 1, 2019) and March 1, 2021; and (2) screened positive for OUD at jail intake. We expect to identify 7,500 patients with OUD in the seven counties over 18 months. Preliminary data from 2018 indicate that the proportion of incarcerated persons who screen positive for OUD will vary by month (range=27–65%), as will MOUD provision (range=9–61%).

2.1.4. Data sources and measures.

Initially established by statute (Chapter 55 of the Acts of 2015) to inform the Commonwealth’s response to the opioid epidemic, the PHD now operates under the authority of M.G.L. c. 111, §237, which allows individual-level linkage of datasets from several state agencies to inform analyses of population health trends focusing on opioids as well as other health priorities that the MDPH Commissioner determines. PHD includes all MA residents with public or private health insurance. The dataset, covering more than 98% of the state’s population, has a “backbone” built on the MA all-payer claims database (APCD), to which more than 20 state datasets are linked, including state-funded addiction treatment records from the Bureau of Substance Addiction Services (BSAS), the prescription monitoring program (PMP), opioid-related incidents from the MA Ambulance Trip Record Information System (MATRIS), mortality records (including autopsy and postmortem toxicology), and criminal justice records, including data from all county jails. Direct identifiers from component datasets are matched to identifiers in the APCD through probabilistic matching processes, and are then de-identified. The PHD data have been critical to understanding the opioid epidemic in MA. MDPH will continue to update the PHD for the duration of the study. The PHD data will enable examination of individual and site-specific outcomes.

Administrative data will be acquired from Sheriff’s Departments and the PHD for all persons who are incarcerated. The Sheriff’s Departments routinely collect data from community providers on whether treated releasees keep their first appointment. We will provide research staffing support to the study jails to help collect and convey the Sheriff’s Department data to MDPH. Given the 12 to 18 month lag in availability of the PHD data, we will collaborate with MDPH to acquire these data at least twice, once in Year 3 to examine the pre-detention and in-jail characteristics of our cohort, and again early in Year 5. In Year 5, we will construct a PHD data extract that will provide a full 12 months of observation prior to and after jail release.

2.1.5. Planned analyses.

We will use baseline characteristics to construct a propensity score based on a logistic regression to adjust for potential selection bias associated with group membership in subsequent analyses of treatment outcomes (Mark et al., 2001; Socias et al., 2016). Potential predictors will consider age, gender, race, ethnicity, marital status, residence, living arrangement, education, type of crime, sentenced or presentenced, new MOUD initiate or continuing MOUD, and Level of Service Inventory – Revised (LSI-R) risk/needs score. Next, we will test group differences in treatment outcomes by index MOUD (NTX, BUP, methadone, no MOUD). The primary outcome will be postrelease MOUD utilization (e.g., MOUD initiation, engagement, and retention). Secondary outcomes will include health status (e.g., time-to-overdose, time-to-death) and recidivism (e.g., rearrest, reincarceration). We will also examine receipt of services (e.g., behavioral SUD treatment, mental health services, recovery support services) as lagged, time-varying covariates. Finally, given the multi-site study design, in which individuals are nested within sites, we will apply multilevel modeling to account for clustering of the observations within jails, and thereby produce more appropriate standard errors of parameters (Mark et al., 2001). This framework allows for the inclusion of covariates measured at different levels, thereby facilitating the probing of questions involving effects of cross-level interactions. To further define the jail OUD treatment cascade in preparation for Aim 2, we will also compare aggregated jail rates of OUD screening; MOUD initiation in jail; community MOUD initiation, engagement, and retention. The study will also examine site-level covariates (e.g., screening, MOUD treatment rates, services provision, intensive care coordination) as well as individual-level covariates (e.g., MOUD type, age, race/ethnicity, gender).

2.2. Aim 2: An MOUD implementation study

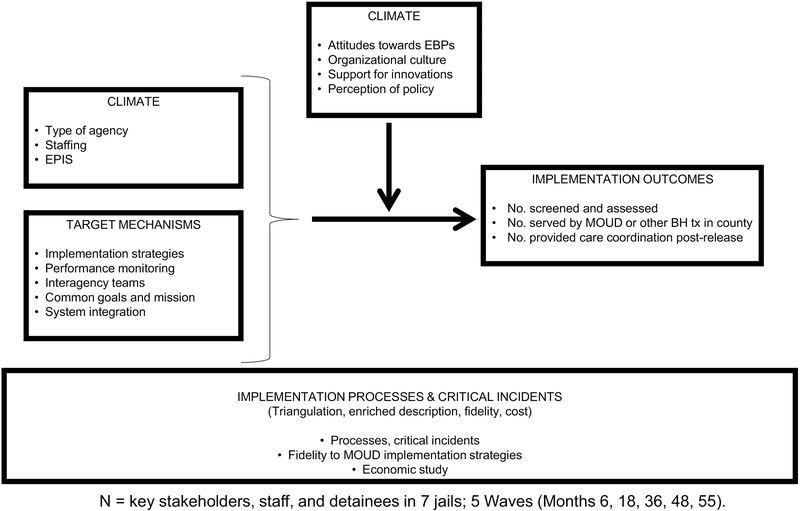

2.2.1. Overall design.

We will conduct an implementation study to understand systemic and contextual factors that facilitate and impede delivery of MOUD in jail and community care coordination, and key practices that optimize MOUD provision and linkage to community MOUD care. The key practices include: (1) the ability to screen and diagnose OUD in jail settings, (2) the process of delivering and managing individuals on MOUD, as well as provision of adjunctive behavioral treatment in jails, and (3) the provision of care coordination postrelease with MOUD community providers. The implementation study will examine the facilitators and barriers to provision of different types of MOUD in jail as well as the strategies, processes, and procedures that the jails and their communities employ to deliver them (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3: MassJCOIN implementation study.

BH tx – behavioral health treatment

EBP – evidence-based practice

MOUD - medications for opioid use disorder

The specific aims of the implementation study are to characterize: (1) implementation strategies and targets used to implement these practices, (2) association between MOUD implementation and implementation outcomes, and (3) implementation processes and critical incidents during MOUD implementation.

2.2.2. Study respondents and data collection.

We will collect data via surveys, focus groups, and in-depth semi-structured interviews, involving the MOUD program administrators, other key jail administrators, MOUD treatment teams, and community treatment providers. Survey respondents will include the MOUD program administrators, and other key administrators in the jails, and community treatment providers. We will survey these respondents at multiple waves to learn about their implementation efforts and then collect data at the last wave on the number of clients screened, assessed, treated, and in community care. This procedure will allow us to monitor the implementation progress of each site for the duration of the study.

2.2.3. Survey instrumentation.

Study staff will conduct surveys at month 6 (wave 1) to characterize the stage of implementation in the EPIS model, and again at months 18 (wave 2), 36 (wave 3), and 48 (wave 4) to examine changes in these key dimensions of the EPIS model. This instrumentation will enable examination of descriptors, predictors, and moderators (agency-level). The study will use a series of measures to describe the inner context of each county agency. The study will also gather contextual measures at both the agency and county levels, which include type of agency; staffing; attitudes toward evidence-based practices (EBPs); organizational culture support for innovation; perception of policy context; and EPIS domains. For implementation study aim 1, we will measure implementation strategies and targets in each jail. Constructs of interest include performance monitoring; interagency teams; common goals/missions across agencies; and system integration. For implementation study aim 2, we will measure associations between MOUD implementation and implementation outcomes, as indicated by the number of individuals screened and assessed for OUD; number of individuals provided MOUD and/or behavioral health treatment; and number of individuals provided with care coordination with community-based providers postrelease. For implementation study aim 3, we will measure implementation processes and critical incidents. We will use qualitative data to triangulate quantitative findings and enrich our understanding of how the target mechanisms work and lead to outcomes.

2.2.4. Qualitative data collection.

We will conduct focus groups and in-depth interviews with jail MOUD treatment teams and community treatment staff at months 6 and 48. The study will develop focus group and interview guides to assess the EPIS domains, as well as the barriers and facilitators that are most critical to MOUD treatment implementation and retention attainment outcomes. We will also obtain documents and archival materials and attend relevant local and statewide briefing meetings to supplement qualitative and quantitative findings focused on barriers, facilitators, and implementation strategies. We will use qualitative methods to characterize implementation strategies in each jail and compare them against jail-based MOUD practice guidelines that the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Admnistration (SAMHSA) has recently promulgated (SAMHSA, 2019).

2.2.5. Analyses.

For the quantitative analyses, we will use baseline (i.e., wave 1) values as covariates in analyses of mechanisms and outcomes (waves 2–4); therefore, our analyses will examine differences between groups and within-county change rates among the study waves, controlling for wave 1. We will assess implementation outcomes at waves 2–4 time points, as well as at month 55 (wave 5). The repeated measures and longitudinal techniques will allow us to test for predictive associations among group membership, hypothesized target mechanisms, and implementation outcomes over time, controlling for wave 1 values. Our analyses will focus on examining rates of change for each county/jail using the longitudinal design, and identification of which implementation strategies affect which MOUD related outcomes. Primary tests of association will be 2-sided with alpha=0.05.

For the qualitative analyses, we will use inductive and deductive approaches to develop coding schemes. The EPIS framework will serve as the basis for deductive, a priori code development. We will then review interviews and focus groups to identify additional codes, using inductive methods, to supplement the EPIS-based codes. To establish reliability, masters-level research assistants and co-investigators will double code all qualitative data (interviews and focus groups). We will use a mixed-methods approach to integrate quantitative and qualitative data, using salient themes and quotes from our qualitative data to place our quantitative findings in context, allowing us to ascertain facilitators that MOUD programs should promote and barriers that they should avert or eliminate. We will use a joint display framework to integrate our quantitative and qualitative results.

2.3. Aim 3: An economic study of jail-based MOUD provision

2.3.1. Overall design.

We will estimate costs associated with implementing and managing MOUD in jails, and perform an economic evaluation to determine whether in-jail MOUD is cost-effective from both local policy-maker and societal perspectives. We selected these two stakeholder perspectives because they are most relevant for OUD interventions among justice-involved populations. We will collect sufficient information to examine the economic impact from other perspectives, if necessary. The local policy-maker perspective is crucial to informing public resource allocation decisions, given that the public is ultimately responsible for funding services in jails and detention centers, community interventions for substance use disorders, and health care for persons who were formerly incarcerated. Resources that we will value as part of this perspective include all OUD- and non-OUD-related health care services (e.g., inpatient, residential, outpatient, emergency department, pharmacotherapy), the direct costs associated with recidivism, and other services that taxpayers fund. The societal perspective is broader and includes all mentioned health care services, direct costs to the criminal justice sector, and indirect costs associated with recurrent opioid use, such as costs that victims of crime incur, costs of premature mortality, and so on (McCollister et al., 2010; Neuman et al., 2017). Failure to account for these indirect costs, as well as any potential value offsets, can undermine the true value of an intervention. Moreover, the societal perspective is recommended as most appropriate for economic evaluation studies such as this one where indirect costs may be substantial (Neuman et al., 2017).

2.3.2. Study population and data sources.

Our estimation of the intervention costs will be guided by a tailored version of the Drug Abuse Treatment Cost Analysis Program (DATCAP) instrument. The DATCAP is a standardized, customizable tool designed to measure the costs of programs in various settings (French et al., 1997; French, 2003). The resources that each participant cohort uses will be captured from the PHD, as already discussed. The study will derive the unit cost(s) associated with each resource type from sources reflecting national “real-world” costs that local policy-makers and society face (Table 1).

Table 1.

MassJCOIN economic study.

| Unit cost sources |

Unit cost source by perspective |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Utilization data | Policymaker | Societal |

|

| |||

| Healthcare services | Source | ||

| Hospitalization | PHD | MMS | Medicare FFS |

| Outpatient visit | PHD, CP | MMS | Medicare FFS |

| ED | PHD | MMS | Medicare FFS |

| Mental health substance use | PHD, CP | MMS | Medicare FFS |

| Inpatient detox | PHD, CP | MMS | Medicare FFS |

| Residential treatment | PHD, CP | MMS | Medicare FFS |

| Medications | |||

| MOUD Prescriptions | PHD | MMS | FSS |

| Other resources | |||

| Criminal justice activities | PHD, BLS | McCollister et al. (2010) | McCollister et al. (2010) |

| Social services | PHD | McCollister et al. (2017) | McCollister et al. (2017) |

Notes: ED = Emergency Department; MOUD = medications for opioid use disorder; PHD = Public Health Data Warehouse; CP = community partner; BLS = Bureau of Labor Statistics; FSS = Federal Supply Schedule; MMS = Medicaid Market Scan.

2.3.3. Analysis.

Our comprehensive economic evaluation of MOUD over the study period will follow well-established guidelines (Drummond et al., 2008; Glick et al., 2014; Neumann et al., 2017). Our primary health economic outcomes will be: (1) the costs of implementing and continually managing each jail MOUD program; and (2) incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs).

We will estimate the resources and associated costs required to implement and manage the program, using a combination of macro-costing (“top down”) and micro-costing (“bottom up”) methods. The macro-costing approach is based on administrative records, which typically contain some, but not all, necessary information. The micro-costing approach is based on site visits and semi-structured interviews with jail and community treatment leaders and staff. We will conduct micro-costing assessments while the study is in progress, once the programs have reached a steady state, to ensure that all resources used are captured appropriately. Cost results will be summarized to express total implementation costs over the duration of the intervention (for each MOUD), as well as the average participant cost per MOUD treatment episode.

The ICER is the incremental predicted cost of a chosen strategy relative to another, divided by the incremental predicted effectiveness of the two strategies. The study will use the resource costing method to estimate unadjusted individual-level costs. This method involves determining a unit price weight for each resource and stakeholder perspective and multiplying them by the number of relevant resource units consumed (Drummond et al., 2015; Glick et al., 2014; Neumann et al., 2017). The measure of effectiveness for the ICERs will be the predicted number of opioid overdoses (fatal and nonfatal) in the primary analysis (aim 1).

We will model the monthly person period, and calculate predicted mean costs for each resource category, as well as number of overdoses, using multivariable generalized-linear mixed models (GLMM) to allow for the inclusion of random effects and multilevel modeling, as discussed. Our multivariable models will control for factors relevant to the economic analysis that were not accounted for in the propensity-scoring process. The GLMM will also allow us to choose the most appropriate mean and variance functions according to the observed data distributions, and use all available data for each participant (Glick et al., 2014). We will use the statistical method of recycled predictions to obtain the final predicted mean values, which will be summed and tested for each perspective over the study period (Glick et al., 2014).

We will use nonparametric bootstrapping techniques within the multivariable framework to estimate p-values and standard errors for each cost and effectiveness measure, while accounting for sampling uncertainty. In line with current recommendations, we will calculate ICERs, and construct cost-effectiveness acceptability curves to estimate the uncertainty around each ICER, regardless of the significance level for the cost and effectiveness differentials individually (Glick et al., 2014). Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves will illustrate the probability that the strategy of interest is cost-effective relative to the others, across a wide range of different value thresholds. We will also conduct sensitivity analyses by modifying model assumptions and parameter estimates for which we are uncertain (Neumann et al., 2017). The study will adjust all monetary values for inflation, and the study will discount all values exceeding a 12-month observation period to control for time preference (Glick et al., 2014; Neumann et al., 2017).

3. Adaptations due to COVID-19

Our MassJCOIN team made significant progress during its first six months of operation. Key accomplishments included establishment of a communication infrastructure to collaborate with our multi-disciplinary multi-institutional team and, for each jail, hiring and onboarding of research staff to assist jail staff with collection of baseline jail data for the treatment outcome study (aim 1), completion of site visits, collection of most wave 1 qualitative data, and protocols to collect data as participants enter and exit jail. In March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted all research activities.

The COVID-19 pandemic caused MA to declare a state of emergency on March 10, 2020. Participating jails restricted access to allow only essential security and health personnel, and implemented other mitigation policies. As a result, no research staff or behavioral health staff could enter the jails. In response, MassJCOIN reassigned research staff who had been assisting with aim 1 data collection to assist with transcription and coding of aim 2 qualitative data and other tasks. All jails managed to maintain a master list of participants with key variables needed for aim 1. However, the ability to collect and compile the needed data from jail databases and files has been limited and has varied by site depending on virtual access to data.

These jails deemed MOUD as an essential health service. Thus, despite COVID-19 mitigation activities, all jails continued to deliver MOUD. However, to ensure social distancing, jails no longer administer MOUD in groups but instead in housing units. Also, jails have canceled in-person behavioral health groups. Some sites have transitioned to now using telehealth to deliver some behavioral health services. Jails also made many other adaptations to MOUD programming (e.g., see Donelan et al., 2020). The research team has been considering how to incorporate measurement of these adaptations into future waves of aim 2 qualitative data collection.

A major COVID-19 impact on MassJCOIN was the rapid mandated release of nonviolent detainees, resulting in rapid decreases in the jail population at all sites. Our jail partners have reported that many rapid releases were MOUD patients released on short notice, making it difficult to arrange for continued receipt of community-based MOUD and other care-continuity planning. At the same time, police reportedly made fewer arrests and courts operated on an emergency basis only, resulting in fewer prosecutions and potentially reducing the number of individuals detained pre-trial. Thus, fewer individuals with OUD have been entering the jails. Also, our jail partners have reported that those who have been incarcerated appear to be more likely to be charged with violent crimes or indigent than before COVID-19 occurred. Given the MassJCOIN study design and protocols, we are positioned to document and account for the impacts of COVID-19 in relation to each aim.

On July 5, 2020, MA entered Phase 3 of its post-COVID-19 Reopening Plan. As MassJCOIN research staff have begun to return to work at the jails, the first priority has been ensuring the safe return of research staff to these environments where space is at a premium and social distancing is challenging. The first order of business has been to review the jails’ electronic health records and other documentation to extract the needed information for persons who received MOUD or screened positive for OUD, assess missingness of data, and determine the actual enrollment in relation to expected enrollment.

4. Conclusion

Through the MassJCOIN study, we will assess MOUD treatment outcomes, implementation, and costs within seven HOCs across MA. We will produce findings with direct implications for policy and practice for OUD in criminal justice settings as well as MOUD treatment options. More broadly, MassJCOIN will establish a network of criminal justice stakeholders, community-based providers, and researchers as a foundation for future cooperative research to develop and test new opioid treatment options for jail populations returning to the community.

Highlights.

A 2018 law mandated that seven jails in Massachusetts provide all FDA-approved medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) during incarceration and also facilitate continuation of MOUD in the community on release.

The Massachusetts Justice Community Opioid Innovation Network (MassJCOIN) is conducting a Type 1 hybrid effectiveness-implementation study of the program.

MassJCOIN adapted research activities in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

MassJCOIN will produce findings with direct implications for policy and practice for OUD in criminal justice settings.

Acknowledgements

MassJCOIN Research Group:

Essex County Sheriff’s Department:

Sheriff Kevin F. Coppinger

Jason Faro

Franklin County Sheriff’s Office:

Sheriff Christopher J. Donelan

Edmond Hayes

Hampden County Sheriff’s Department:

Sheriff Nicholas Cocchi

Martha Lyman, Ed.D

Thomas Lincoln, M.D.

Hampshire County Sheriff’s Office:

Sheriff Patrick J. Cahillane

Melinda Cady

Middlesex County Sheriff’s Office:

Sheriff Peter J. Koutoujian

Kashif Siddiqi

Dan Lee

Norfolk County Sheriff’s Office

Sheriff Jerome P. McDermott

Tara Flynn

Erika Sica

Suffolk County Sheriff’s Department:

Sheriff Steven W. Tompkins

Rachelle Steinberg

Marjorie Bernadeau-Alexandre

Financial support: The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) 1UG1DA050067–01; Pivovarova - K23DA049953

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 191st Court of the Commonweath of Massachusetts. An Act For Prevention And Access To Appropriate Care And Treatment Of Addiction. Chapter 208 of the Acts of 2018, §98.https://malegislature.gov/Laws/SessionLaws/Acts/2018/Chapter208.Accessed 2/2/2019. [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SM (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidencebased practice implementation in public service sectors. Admininstartion and Policy in Mental Health, 38(1), 4–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barocas JA, White LF, Wang J, Walley AY, LaRochelle MR, Bernson D, Land T, Morgan JR, Samet JH, Linas BP(2018). Estimated prevalence of opioid use disorder in Massachusetts, 2011–2015: A capture-recapture analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 108(12), 1675–1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becan JE, Bartkowski JP, Knight DK, Wiley TRA, DiClemente R, Ducharme L, Welsh WN, Bowser D, McCollister K, Hiller M, Spaulding AC, Flynn PM, Swartzendruber A, Dickson MF, Fisher JH, & Aarons GA (2018). A model for rigorously applying the exploration, preparation, implementation, sustainment (EPIS) framework in the design and measurement of a large scale collaborative multi-site study. Health & Justice, 6(1), 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Peterson M, Clarke J, Macmadu A, Truong A, Pognon K, Parker M, Marshall B, Green T, Martin R, Stein L, & Rich JD (2019). The benefits and implementation challenges of the first state-wide comprehensive medication for addictions program in a unified jail and prison setting. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 205, 107514. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman Bb, Pyne JM, & Stetler C (2012). Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care, 50(3), 217–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donelan CJ, Hayes E, Potee RA, Schwartz L, Evans EA (2020). COVID-19 and treating incarcerated populations for opioid use disorder. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. E-pub ahead of print Dec 2:108216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, O’Brien B, & Stoddart G (2008). Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Third ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond MF, Schulpher MJ, Claxton K, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW (2015). Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Fourth ed. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson WJ (2018, March 22). Studying implementation of medication-assisted treatment in prisons and jails [abstract]. Academic and Health Policy Conference on Correctional Health; Houston, TX, United States. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson WJ, Johnston J, Clarke J, Koutoujian PJ, Maurer K, Gallagher C, White J, Nickl D, & Taxman FS (2019). Advancing the implementation and sustainment of Medication Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorders in prisons and jails. Health & Justice, 7(19). 10.1186/s40352-019-0100-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French MT (2003). Drug Abuse Treatment Cost Anslysis Program (DATCAP): User’s Manual. University of Miami, Florida. [Google Scholar]

- French MT, Dunlap LJ, Zarkin GA, McGeary KA, & McLellan AT (1997). A structured instrument for estimating the economic cost of drug abuse treatment: The Drug Abuse Treatment Cost Analysis Program (DATCAP). Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 14(5), 445–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann PD, Hoskinson R Jr., Gordon M, Schwartz R, Kinlock T, Knight K, Flynn PM, Welsh WN, Steain LAR, Sacks S, O’Connell DJ, Knudsen HK, Shafer MS, Hall E, Frisman LK, et al. (2012). Medication-assisted treatment in criminal justice agencies affiliated with the criminal justice-drug abuse treatment studies (CJ-DATS): availability, barriers, and intentions. Substance Abuse, 33(1), 9–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann PD, Wilson D, Knudsen HK, Ducharme LJ, Welsh WN, Frisman L, Knight K, Lin H, James A, Albizu-Garcia CE, Pankow J, Hall EA, Urbine TF, Abdel-Salam S, Duvall JL, & Vocci FJ (2015). Effect of an organizational linkage intervention on staff perceptions of medication-assisted treatment and referral intentions in community corrections. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 50, 50–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleicher L (2017) Implementation Science In Criminal Justice: How Implementation Of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices Affects Outcomes. Springfield, IL: Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority; http://www.icjia.state.il.us/articles/implementationscience-in-criminal-justice-how-implementation-of-evidence-based-programs-and-practices-affects-outcomes. Accessed 2/11/2019. [Google Scholar]

- Glick HA, Doshi JA, Sonnad SS, & Polsky D (2014). Economic evaluation in clinical trials. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon MS, Kinlock TW, Couvillion KA, Schwartz RP, & O’Grady K (2012). A Randomized Clinical Trial of Methadone Maintenance for Prisoners: Prediction of Treatment Entry and Completion in Prison. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 51(4), 222–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon MS, Kinlock TW, Schwartz RP, Fitzgerald TT, O’Grady KE, & Vocci FJ (2014). A randomized controlled trial of prison-initiated buprenorphine: Prison outcomes and community treatment entry. Drug and Alcohol Dependence,142, 33–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Ostile E, Scott CK, Dennis M, & Carnavale J (2020). A scoping review of barriers and facilitators to implementation of medications for treatment of Opioid Use Disorder within the criminal justice system. International Journal of Drug Policy, 81, 102768. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero EG, Frimpong J, Kong Y, Fenwick K, & Aarons GA (2018). Advancing theory on the multilevel role of leadership in the implementation of evidence-based health care practices. Health Care Management Review, 45(2), 151–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M (2020). Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2018. NCHS Data Brief, no 356. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Landenberger NA, & Lipsey MW (2005). The positive effects of cognitive-behavioral programs for offenders: A meta-analysis of factors associated with effective treatment. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 1, 451–476. [Google Scholar]

- Lee JD, Nunes EV Jr., Novo P, Bachrach K, Bailey GL, Bhatt S, Farkas S, Fishman M, Gauthier P, Hodgkins CC, King J, Lindblad R, Liu D, Matthews AG, May J, Peavy KM, Ross S, Slaazar D, Schkolnik P, Shmueli-Blumberg D, Stablein D, Subramaniam G, & Rotrosen J (2018). Comparative effectiveness of extended-release naltrexone versus buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid relapse prevention (X:BOT): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 391(10118), 309–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW (2010). Improving the effectiveness of juvenile justice programs: A new perspective on evidence-based practice. Justice Research and Policy, 14(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Mace S, Siegler A, Wu KC, Latimore A, Flynn H (2019). Medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder in jails and prisons: a planning & implementation toolkit. The National Council. [Google Scholar]

- Magura S, Lee JD, Hershberger J, Joseph H, Marsch L, Shropshire C & Rosenblum A (2009). Buprenorphine and methadone maintenance in jail and post-release: A randomized clinical trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 99(1–3), 222–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark TL, Woody GE, Juday T, & Kleber HD (2016). The economic costs of heroin addiction in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 61(2), 195–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massachusetts Department of Public Health. (2020). Data Brief: Opioid-Related Overdose Deaths among Massachusetts Residents. https://www.mass.gov/doc/opioid-related-overdose-deaths-among-ma-residents-november-2020/download

- McCollister KE, French MT, & Fang H (2010). The cost of crime to society: new crime-specific estimates for policy and program evaluation. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 108(1–2), 98–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCollister K, Yang X, Sayed B, French MT, Leff JA, & Schackman BR (2017) Monetary conversion factors for economic evaluations of substance use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 81, 25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moullin JC, Dickson KS, Stadnick NA, Rabin B,& Aarons GA (2019). Systematic review of the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework. Implementation Science, 14(1), 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann PJ, Sanders GD, Russell LB, Siegel JE, & Ganiats TG (2017) Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Socias ME, Volkow N, & Wood E (2016). Adopting the ‘cascade of care’ framework: An opportunity to close the implementation gap in addiction care? Addiction, 111(12), 2079–2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2019). Use of medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder in criminal justice settings. HHS Publication No. PEP19-MATUSECJSRockville, MD: National Mental Health and Substance Use Policy Laboratory. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Taxman FS & Belenko S (2012). Implementing evidence-based practices in community corrections and addiction treatment. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Williams AR, Nunes EV, Bisaga A, Levin FR, & Olfson M (2019). Development of a Cascade of Care for responding to the opioid epidemic. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 45(1), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AR, Nunes EV, Bisaga A, Pincus HA, Johnson KA, Campbell AN, Remien RH, Crystal S, Friedmann PD, Levin FR, & Olfson M (2018). Developing an opioid use disorder treatment cascade: A review of quality measures. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 91, 57–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaller N, McKenzie M, Friedmann PD, Green TC, McGowan S, & Rich JD (2013). Initiation of buprenorphine during incarceration and retention in treatment upon release. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 45(2), 222–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]