Abstract

Background:

The ACTION IO study (NCT03584191) aimed to identify perceptions, attitudes, behaviors, and potential barriers to effective obesity care across people with obesity (PwO) and healthcare professionals (HCPs). Results from Saudi Arabia are presented here.

Methods:

A survey was conducted from June to September 2018. In Saudi Arabia, eligible PwO were ≥18 years with a self reported body mass index of ≥30 kg/m2. Eligible HCPs were in direct patient care.

Results:

The survey was completed by 1,000 PwO and 200 HCPs in Saudi Arabia. Many PwO (68%) and HCPs (62%) agreed that obesity is a chronic disease. PwO felt responsible for their weight management (67%), but 71% of HCPs acknowledged their responsibility to contribute. Overall, 58% of PwO had discussed weight with their HCP in the past 5 years, 46% had received a diagnosis of obesity, and 44% had a follow up appointment scheduled. Although 50% of PwO said they were motivated to lose weight, only 39% of HCPs thought their patients were motivated to lose weight. Less than half of PwO (39%) and HCPs (49%) regarded genetic factors as a barrier to weight loss. Many PwO had seriously attempted weight loss (92%) and achieved ≥5% weight loss (61%), but few maintained their weight loss for >1 year (5%).

Conclusion:

Saudi Arabian results have revealed misperceptions among PwO and HCPs about obesity, highlighting opportunities for further education and training about obesity including the biologic basis and clinical management.

Keywords: ACTION-IO, obesity, obesity management, perceptions, Saudi Arabia

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is a chronic, relapsing disease that has a multifactorial origin, including genetic, metabolic, psychological, sociocultural, and environmental factors.[1,2] With only recent recognition of obesity as a disease that requires early detection and effective management,[2,3] the global prevalence is rising and represents a major public health problem.[4] Prevalence rates of obesity in Saudi Arabia for men (30.0%) and women (44.4%) were similar to global prevalence rates of obesity (36.9% for men, 38.0% for women).[5] In Saudi Arabia, obesity is associated with diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and elevated blood pressure.[6] One of the most recent discoveries is that obesity is likely to increase risk for vulnerability to COVID 19.[7]

Recommended treatment for obesity includes lifestyle modification, with addition of pharmacotherapy or bariatric surgery depending on the disease severity and response to lifestyle modification alone.[1,8] However, in the routine setting people with obesity (PwO) experience varied care.[9] Therefore, to explore the barriers to effective obesity management, the ACTION IO (Awareness, Care, and Treatment In Obesity maNagement – an International Observation) study investigated the perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors related to obesity and its management for PwO and healthcare professionals (HCPs) across 11 countries.[9] The study highlighted that many HCPs (88%) and PwO (68%) considered obesity as a disease, yet >81% of PwO felt that weight loss was their responsibility.[9] This could play a role in why some patients do not approach HCPs to discuss weight management at an early stage of their disease. In addition, 68% of HCPs thought that PwO were not motivated or were not interested in losing weight.[9] These perceptions were considered as a barrier for effective and timely weight management discussions.

To understand the barriers to effective obesity management in Saudi Arabia, we analyzed the Saudi Arabian data collected in the ACTION IO study from PwO and HCPs. Here we report the main points related to the perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors of PwO and HCPs in Saudi Arabia with respect to the global results from all participating countries. We also assessed the potential barriers to optimizing treatment and providing effective care for PwO in Saudi Arabia.

METHODS

Methodology for the ACTION IO survey has been reported previously;[9] it was a non interventional, cross sectional, descriptive study (NCT03584191). Data were collected using a survey of PwO and HCPs from 11 countries. The questionnaires used for this study were developed by an international steering committee of obesity experts, including three medical doctors employed by Novo Nordisk, the study sponsor, and a representative from Saudi Arabia. Questionnaire items were phrased and presented in the same order for each respondent. Items presented in a list were displayed either alphabetically, categorically, chronologically, or randomly, as deemed relevant for each set of responses. Saudi Arabian participants completed the survey between June 4, 2018 and July 25, 2018. An independent review board at King Fahad Medical City, Riyadh, approved the surveys in Saudi Arabia (IRB number H 01 R 012). The survey was conducted by a third party vendor (KJT Group [Honeoye Falls, NY, USA]) who also managed data collection and analysis of de identified data.

To reduce sampling bias and achieve a representative sample, a stratified sampling approach was used for PwO; outbound samples were sent in accordance to demographic targets that were pre determined such as those based on gender, age, household income, and region. To ensure population representativeness, targets were monitored throughout the data collection process. Before participation, PwO were not informed of specific study goals, but only that the purpose was “to determine treatment experiences of patients with a specific condition”.

A series of screening questions were used to determine eligibility of PwO and HCPs based on pre determined demographic targets; PwO were eligible if they were ≥18 years, with a body mass index (BMI) of ≥30 kg/m2 based on self reported height and weight, while HCPs were eligible if they had ≥2 years of experience in direct patient care, and had seen ≥100 patients in the past month as well as ≥10 patients who had a BMI of ≥30 kg/m2. More information about eligibility criteria has been published previously.[9] Respondents who met these eligibility criteria and other study criteria could complete the full survey in their native language. The final sample for PwO was weighted to representative demographic targets (gender, age, household income, and region). Although HCP data were monitored for specialist types, they were not weighted. All respondents provided electronic informed consent before completing the screening questions and survey. In Saudi Arabia, recruitment for respondents was held through online panel companies, to which consent was given to permit contact for research purposes, and via telephone or in person.

This study was sponsored by Novo Nordisk and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki,[10] and the Guidelines for Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices.[11]

RESULTS

Participants

A total of 2,669 PwO and 638 HCPs in Saudi Arabia were invited to participate in the survey, with a response rate of 60% for PwO and 68% for HCPs. A total of 1,000 PwO and 200 HCPs completed the survey. The mean completion time was 31 minutes for PwO and 28 minutes for HCPs. Baseline demographics and characteristics for PwO and HCPs are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample demographics and characteristics of PwO and HCPs in Saudi Arabia

| PwO (n=1,000) | HCPs (n=200) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (range), years | 37 (18-74) | 47 (27-71) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 565 (57%) | 135 (68%) |

| Female | 435 (43%) | 65 (32%) |

| BMI classification* | ||

| Respondents | 1,000 (100%) | 81 (100%) |

| Underweight | 0 | |

| Normal Range | 19 (23%) | |

| Overweight | 42 (52%) | |

| Obesity Class I (30-34.9 kg/m2) | 665 (67%) | 19 (23%) |

| Obesity Class II (35-39.9 kg/m2) | 296 (30%) | 1 (1%) |

| Obesity Class III (≥40 kg/m2) | 39 (4%) | 0 |

| Number of comorbidities | ||

| 0 | 322 (29%) | |

| 1 | 307 (33%) | |

| 2 | 171 (17%) | |

| 3 | 110 (12%) | |

| ≥4 | 90 (9%) | |

| HCP category† | ||

| PCP | 52 (26%) | |

| Specialist | 148 (74%) | |

| Diabetologist/endocrinologist | 25 (13%) | |

| Cardiologist | - | |

| Internal medicine (non-PCP) | 72 (36%) | |

| Gastroenterologist | 26 (13%) | |

| Obstetrician/gynecologist | 25 (13%) | |

| Obesity specialist‡ | ||

| Yes | 147 (74%) | |

| No | 53 (26%) | |

| Regions in Saudi Arabia§ | ||

| Central | 299 (30%) | 37 (19%) |

| West | 358 (36%) | 76 (38%) |

| North | 28 (3%) | 17 (9%) |

| South | 166 (17%) | 5 (3%) |

| East | 149 (15%) | 65 (33%) |

Data are numbers (%), unless otherwise specified, and are reported for the final unweighted sample except for the PwO characteristics - denoted by (*) - which represent weighted percentages. †Bariatric surgeons were ineligible, per protocol pre-specified criteria. ‡A physician who meets at least one of the following criteria: at least 50% of their patients are seen for obesity/weight management, or has advanced/formal training in treatment of obesity/weight management beyond medical school, or considers themselves to be an expert in obesity/weight loss management, or works in an obesity service clinic. §Geographical regions include the following 13 administrative provinces: Central - Qassim and Riyadh; West - Tabuk, Madinah, and Makkah; North - Northern Borders, Jawf, and Ha’il; South - Bahah, Jizan, ‘Asir, and Najran; East - the Eastern Province. BMI: Body mass index; HCP: Healthcare professional; PCP: Primary care physician

Perceptions of obesity as a chronic disease

Most PwO (87%) and 65% of HCPs agreed that obesity has a large impact on overall health, but fewer PwO (68%) and 62% of HCPs categorized obesity as a chronic disease. In comparison, 83–93% of PwO and 61–86% of HCPs believed that chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke, cancer, and diabetes had a large impact on overall health.

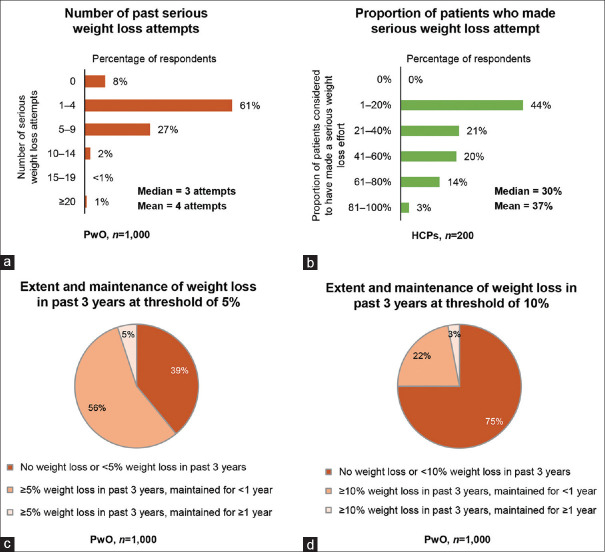

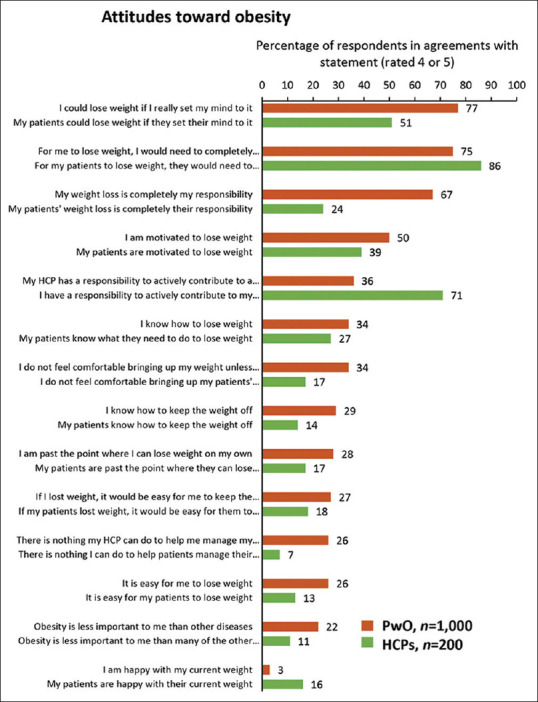

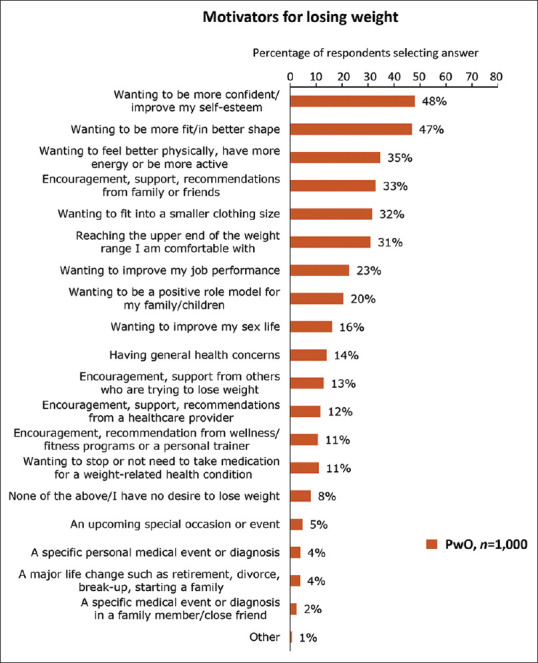

Responsibility and motivation for obesity treatment

Two thirds of PwO (67%) thought that weight loss was their own responsibility and only 36% felt that their HCP should actively contribute [Figure 1]. Conversely, 24% of HCPs considered weight loss to be the responsibility of PwO, and 71% of HCPs acknowledged their own responsibility to contribute to their patients’ weight loss efforts. Additionally, while 50% of PwO were motivated to lose weight, only 39% of HCPs agreed that their patients were motivated. The top two motivators for PwO to lose weight were to be more confident and improve self esteem (48%), and to be more fit and in better shape (47%) [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Level of agreement with statements describing attitudes toward obesity for PwO and HCPs in Saudi Arabia. Rated on a scale of 1 (do not agree at all) to 5 (completely agree). HCP, healthcare professional; PwO, people with obesity

Figure 2.

Motivators for weight loss in PwO in Saudi Arabia (n=1,000). PwO, people with obesity

Previous weight loss attempts and outcomes

Most PwO (92%) reported making ≥1 serious weight loss attempt (mean four attempts) [Figure 3], whereas HCPs thought that only a mean of 37% of their patients had seriously attempted weight loss. Although most PwO (77%) believed they could lose weight [Figure 1], many struggled and had difficulty with maintaining any weight loss. A proportion of PwO (61%) reported a weight loss of ≥5% body mass over the past 3 years, of which 8% maintained the weight loss for ≥1 year (5% of all PwO). Only 25% of PwO reported a weight loss of ≥10% body mass, of which 11% maintained the weight loss for ≥1 year (3% of all PwO) [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Weight loss efforts and weight loss response in Saudi Arabia. (a) Number of past serious weight loss attempts by PwO. (b) Proportion of patients considered by HCPs to have made a serious weight loss attempt. (c and d) Weight loss and weight loss maintenance for PwO in past 3 years at (c) 5% or (d) 10% of total body weight. HCP, healthcare professional; PwO, people with obesity

The top two reported barriers to weight loss were unhealthy eating habits (71% of PwO; 90% of HCPs) and lack of exercise (60% of PwO; 80% of HCPs). Only 39% of PwO and 49% of HCPs regarded genetic factors as a barrier. PwO reported that the most important factors contributing to regaining weight after weight loss efforts were: no longer following their eating plan (45%); difficulties with staying motivated (45%); lack of exercise (37%); and adherence (29%).

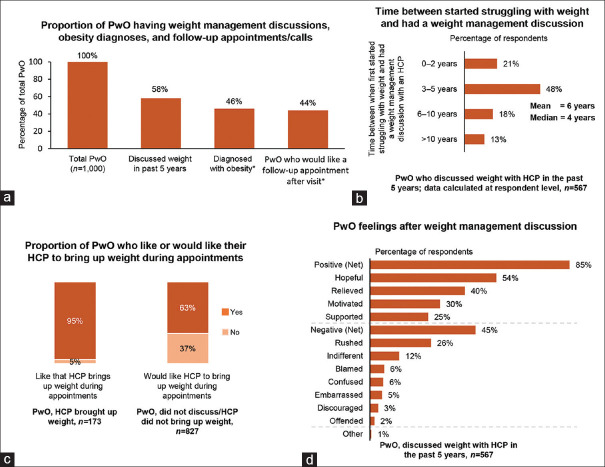

Discussions between PwO and HCPs

Over half of PwO (58%) had weight management discussions with their HCP in the past 5 years [Figure 4]. PwO spent a mean of 6 years (median 4 years) between starting to struggle with their weight and when they first discussed their weight with an HCP.

Figure 4.

PwO–HCP weight management discussions in Saudi Arabia. (a) Proportion of PwO who reported having a weight management discussion with an HCP, a diagnosis of obesity, and a follow up appointment related to weight. (b) For PwO who had a weight management discussion with an HCP in the past 5 years, proportion who had a discussion less than 2 years, 3–5 years, 6–10 years, or more than 10 years after their weight first became an issue. (c) Proportion of PwO who like/would like their HCP to raise the issue of weight during their appointments. (d) Feelings of PwO following discussion about their weight with an HCP. + =nsize less than total due to respondents selecting “not sure” for attributes. HCP, healthcare professional; PwO, people with obesity

In total, 38% of PwO who had discussed weight with an HCP in the past 5 years found the conversation very or extremely helpful, with almost all PwO (95%) being satisfied that their HCP discussed their weight with them. Most PwO (85%) reported positive feelings after weight management discussions with their HCP and only 2% of PwO reported feeling offended. For weight management, 84% of PwO reported that they trusted their HCP’s advice, and 79% stated that they followed all advice given. In contrast, HCPs felt that only 47% of PwO followed their suggestions and were somewhat successful or successful in managing their weight.

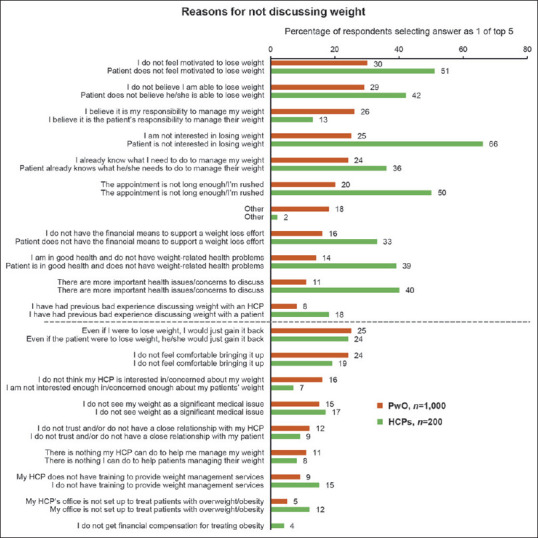

Barriers to weight loss discussion

The top two barriers for PwO not discussing weight with their HCP were lack of motivation (30%) and belief (29%) that they would be able to lose weight [Figure 5]. The top two barriers for HCPs not discussing weight with their patients were their perceptions that their patients were not interested (66%) or motivated (51%) to lose weight [Figure 5]. Additional factors for HCPs not discussing weight loss included limited appointment time (50%) and that there were more important health issues and concerns to discuss (40%).

Figure 5.

Reasons reported by PwO and HCPs for not discussing weight with an HCP or patient, respectively, in Saudi Arabia; reasons with ≥10% difference between the PwO and HCP groups are above the dotted line. HCP, healthcare professional; PwO, people with obesity

Obesity diagnosis and scheduling of follow up appointments

Of the PwO who had discussed their weight with an HCP in the past 5 years, 80% had been diagnosed with obesity (46% of total PwO). HCPs reported informing their patients about an obesity diagnosis 59% of the time, and a small proportion of HCPs (8%) reported never informing their patients of their obesity diagnosis. Most PwO (76%) who had discussed their weight with an HCP were scheduled a follow‐up appointment (44% of PwO in total) [Figure 4]; most PwO (88%) reported attending or planning to attend the appointment if scheduled. HCPs reported that they scheduled follow‐up appointments with 35% of their patients and only 46% of their patients kept these follow‐up appointments always or most of the time.

DISCUSSION

The Saudi Arabian ACTION IO results highlighted opportunities for improving the management of obesity by indicating the mismatches between PwO and HCPs in their perceptions and attitudes toward obesity. Recognition of obesity as a chronic disease was lower among Saudi Arabian HCPs (62%) than the global population (88%).[9] This under recognition of obesity as a chronic disease may stem from an insufficient understanding of the biologic basis of obesity and management strategies.[12,13] This warrants an opportunity to raise PwO and HCP awareness in Saudi Arabia through further education, supported by evidence based guidelines.[1,8] Considering obesity as a disease may lead to a positive change and result in experienced HCPs specializing in obesity, inducing better quality treatment and management strategies.[12]

The study highlighted that many PwO attempted weight loss efforts overall in Saudi Arabia (92%) and the global population (81%). However, weight loss of ≥5% body mass was higher in PwO in Saudi Arabia (61%) than globally (37%) and a similar pattern was observed for weight loss of ≥10% body mass in PwO (25% for Saudi Arabia vs 16% globally).[9] However, sustained weight loss of ≥5% for ≥1 year was lower for PwO in Saudi Arabia (5%) than globally (11%), which could be due to PwO feeling responsible for managing their own weight loss and as a result not seeking help from HCPs.

A potential barrier to effective obesity care was the identification of PwO struggling with weight management for a mean of 6 years before initiating discussions about weight management with an HCP. In the global population, a similar delay in the length of time before PwO had their first discussion with an HCP was reported.[9] We believe it is important to identify and implement strategies that encourage initiating a dialogue between PwO and HCPs earlier as a preventative approach prior to the development of obesity related complications.[9] A higher proportion (76%) of Saudi Arabian PwO had a follow up appointment related to weight scheduled after their last visit compared with the global population of PwO (39%).[9] Yet, as mentioned above, fewer Saudi Arabian PwO than global PwO maintained their weight loss. Therefore, a multidisciplinary approach to obesity care using specialized centers, and a better referral system to these facilities, may be necessary to improve rates of sustained weight loss.

Other identified potential barriers to effective obesity management were the HCP perceptions, in both Saudi Arabia and globally,[9] that PwO were not motivated or interested in losing weight, which was contrary to the opinions of the PwO. This reflects a need for HCP education on the misperceptions of PwO attitudes and behaviors, and the importance of initiating weight management dialogue with PwO.

Potential solutions to tackle misconceptions about obesity, and increase conversations between HCPs and PwO include, considering improvements to local healthcare systems such as multidisciplinary obesity care[14,16] or evaluating patients holistically with the goal of empowering individuals to proactively ask health related questions and make appropriate decisions.[17] Another approach is to provide individualized care with a focus on patient preferences, physical comfort, and involvement of family and friends, as these have been shown to improve clinical outcomes,[14,16] which may also resolve the mismatch between PwO and HCP perceptions.[18,20]

Strengths of the study included high response rates compared with the global ACTION IO study,[9] which could be attributed to some of the surveys being taken in person and may have also increased the accuracy of information obtained from the respondents. In addition, the broad geographic distribution of study samples represented various locations in Saudi Arabia. Key limitations of the study included the cross sectional and descriptive nature, reliance of self reported weight and height measurements, and accuracy of participant recall. In addition, PwO may have under or overestimated their metrics, thus impacting the BMI calculations.

In conclusion, the Saudi Arabian results have indicated that PwO were motivated and interested in losing weight, which needs to be recognized and used as an opportunity to initiate weight management conversations. Results from our study have revealed a need for further education and training of HCPs and PwO on the physiology, causes, and treatment of obesity to increase clinical success rates in the management of obesity.

Financial support and sponsorship

Research relating to this manuscript was funded by Novo Nordisk.

Conflicts of interests

AA Alfadda received financial support to attend an obesity conference during the conduct of the study and for meeting travel expenses, and received consultancy fees during data analysis and manuscript development from Novo Nordisk, and non financial support outside the submitted work from Novo Nordisk.

M Shams and W Abdelfattah are employees of Novo Nordisk.

A Al Qarni, K Alamri, SS Ahamed, S Abo’Ouf, and A Al Shaikh have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants and the site personnel who assisted with the trial. Waleed Abdelfattah was an employee of Novo Nordisk A/S at the time of study conduct and manuscript development. This study was sponsored by Novo Nordisk, which also provided financial support for medical editorial assistance from Luli Randell, PhD and Cassandra Krone, PhD of Articulate Science, Ltd.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alfadda AA, Al Dhwayan MM, Alharbi AA, Al Khudhair BK, Al Nozha OM, Al Qahtani NM, et al. The Saudi clinical practice guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults. Saudi Med J. 2016;37:1151–62. doi: 10.15537/smj.2016.10.14353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray GA, Kim KK, Wilding JPH. World Obesity Federation. Obesity: A chronic relapsing progressive disease process. A position statement of the World Obesity Federation. Obes Rev. 2017;18:715–23. doi: 10.1111/obr.12551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, Reitsma MB, Sur P, Estep K, Lee A, et al. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:13–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frühbeck G, Busetto L, Dicker D, Yumuk V, Goossens GH, Hebebrand J, et al. The ABCD of Obesity: An EASO position statement on a diagnostic term with clinical and scientific implications. Obes Facts. 2019;12:131–6. doi: 10.1159/000497124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:766–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Memish ZA, El Bcheraoui C, Tuffaha M, Robinson M, Daoud F, Jaber S, et al. Obesity and associated factors – Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2013. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E174. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.140236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kassir R. Risk of COVID 19 for patients with obesity. Obes Rev. 2020;21:e13034. doi: 10.1111/obr.13034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, Ard JD, Comuzzie AG, Donato KA, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines and the Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129(suppl 2):S102–38. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caterson ID, Alfadda AA, Auerbach P, Coutinho W, Cuevas A, Dicker D, et al. Gaps to bridge: Misalignment between perception, reality and actions in obesity. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21:1914–24. doi: 10.1111/dom.13752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310:2191–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology (ISPE). Guidelines for Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices (GPP): ISPE. 2020. [updated 2015]. Available from: https://www.pharmacoepi.org/resources/policies/guidelines-08027/

- 12.Allison DB, Downey M, Atkinson RL, Billington CJ, Bray GA, Eckel RH, et al. Obesity as a disease: A white paper on evidence and arguments commissioned by the Council of the Obesity Society. Obesity. 2008;16:1161–77. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghanemi A, Yoshioka M, St Amand J. Broken energy homeostasis and obesity pathogenesis: The surrounding concepts. J Clin Med. 2018;7:453. doi: 10.3390/jcm7110453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rathert C, Williams ES, McCaughey D, Ishqaidef G. Patient perceptions of patient centred care: Empirical test of a theoretical model. Health Expect. 2015;18:199–209. doi: 10.1111/hex.12020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meterko M, Wright S, Lin H, Lowy E, Cleary PD. Mortality among patients with acute myocardial infarction: The influences of patient centered care and evidence based medicine. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:1188–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01138.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient centered care is associated with decreased health care utilization. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24:229–39. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.03.100170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fastenau J, Kolotkin RL, Fujioka K, Alba M, Canovatchel W, Traina S. A call to action to inform patient centred approaches to obesity management: Development of a disease illness model. Clin Obes. 2019;9:e12309. doi: 10.1111/cob.12309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baum C, Andino K, Wittbrodt E, Stewart S, Szymanski K, Turpin R. The Challenges and opportunities associated with reimbursement for obesity pharmacotherapy in the USA. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33:643–53. doi: 10.1007/s40273-015-0264-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan LM, Golden A, Jinnett K, Kolotkin RL, Kyle TK, Look M, et al. Perceptions of barriers to effective obesity care: Results from the national ACTION Study. Obesity. 2018;26:61–9. doi: 10.1002/oby.22054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sogg S, Grupski A, Dixon JB. Bad words: Why language counts in our work with bariatric patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14:682–92. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2018.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]