Abstract

Background and Purpose

Randomized trials demonstrated the benefit of dual antiplatelet therapy in minor ischemic stroke or high-risk transient ischemic attack (TIA) patients. We sought to determine whether the presence of carotid stenosis was associated with increased risk of ischemic stroke and whether the addition of clopidogrel to aspirin was associated with more benefit in patients with versus without carotid stenosis.

Methods

This is a post-hoc analysis of the POINT trial that randomized patients with minor ischemic stroke or high-risk TIA within 12 hours from last known normal to receive either clopidogrel plus aspirin or aspirin alone. The primary predictor was the presence of ≥50% stenosis in either cervical internal carotid artery. The primary outcome was ischemic stroke. We built Cox regression models to determine the association between carotid stenosis and recurrent ischemic stroke and whether the effect of clopidogrel was modified by ≥50% carotid stenosis.

Results

Among 4881 patients enrolled POINT, 3941 patients met the inclusion criteria. In adjusted models, ≥50% carotid stenosis was associated with ischemic stroke risk (HR 2.45 95% CI 1.68-3.57, p<0.001). The effect of clopidogrel (versus placebo) on ischemic stroke risk was not significantly different in patients with <50% carotid stenosis (adjusted HR 0.68 95% CI 0.50-0.93, p=0.014) versus those with ≥50% carotid stenosis (adjusted HR 0.88 95% CI 0.45 – 1.72, p = 0.703), p-value for interaction = 0.573.

Conclusion

The presence of carotid stenosis was associated with increased risk of ischemic stroke during follow-up. The effect of added clopidogrel was not significantly different in patients with versus without carotid stenosis.

Clinical Trial Registration Information

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00991029; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03354429

Keywords: carotid stenosis, clopidogrel, stroke, recurrence

Introduction

Randomized controlled trials showed benefit of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) over single antiplatelet therapy in reducing ischemic stroke risk in patients with minor ischemic stroke and high risk TIA.1-3 Previous studies showed that carotid stenosis is associated with increased risk of recurrence in patients with TIA or minor ischemic stroke.4 We sought to determine whether the presence of carotid stenosis was associated with ischemic stroke risk and whether addition of clopidogrel to aspirin was more beneficial in patients with versus without carotid stenosis.

Methods

Patient cohort

The New York Langone Health Institutional Review Board waived the need for formal review because this study used existing de-identified data. Data from this study is publicly available by the NIH upon reasonable request. This is a post-hoc analysis of the Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke (POINT) trial that enrolled patients with minor stroke (NIHSS ≤ 3) and high-risk TIA (ABCD2 score ≥ 4) within 12 hours from last known normal and randomized to receive either DAPT (aspirin and clopidogrel) or aspirin alone, followed for 90 days. In the present study, we included patients enrolled in the POINT trial who: (1) underwent at least one carotid imaging study, (2) had at least one day of follow-up and (3) did not undergo carotid endarterectomy.

Primary predictor

The presence and degree of carotid stenosis were determined by participating sites based on the results of vascular imaging studies (carotid ultrasound, CT angiography [CTA], MR angiography [MRA], or conventional cerebral angiography). We dichotomized patients to <50% versus ≥50% stenosis in either cervical internal carotid artery. We allowed conventional angiography measurement to replace all other measurements and CTA or MRA measurements to replace carotid ultrasound. The infarct territory on brain imaging was determined by the site investigator. In a sensitivity analysis, we trichotomized the cohort to <50% stenosis, ≥50% stenosis with no infarct OR infarct that is not ipsilateral to the stenotic carotid (asymptomatic stenosis), and ≥50% stenosis with an infarct ipsilateral to the stenotic carotid (symptomatic stenosis).

Outcome

The outcome of interest was 90-day ischemic stroke using a tissue-based definition of stroke.

Statistical analysis

We tested for intergroup differences with Student’s t-test for continuous variables and chi-squared test for categorical variables. We fit Cox proportional hazards models to our outcome and report unadjusted hazard ratios and hazard ratios adjusted for patient age, sex, race, ethnicity, qualifying event (stroke vs. TIA), smoking status, diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and statin use. The proportional hazards assumption was tested and met for the adjusted Cox models by testing Schoenfeld residuals (p=0.2). To test our hypothesis that the effect of DAPT treatment differed by categories of carotid stenosis, we included stenosis*treatment arm (DAPT versus aspirin) interaction in the model with p<0.1 for a statistically significant interaction effect. Subsequently, we stratified Cox models by carotid stenosis and reported the hazard ratio for the DAPT arm in the stratifications. Kaplan-Meier failure curves were used to show events in the stratifications. Analyses were performed using Stata 16.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Among 4881 patients randomized in POINT, 3941 patients met the inclusion criteria (Supplemental Figure I, Supplemental Table I). Baseline characteristics and outcomes of patients with versus with <50% carotid stenosis are shown in Table 1. On unadjusted analysis, presence of ≥50% (versus <50%) carotid stenosis was associated with higher ischemic stroke rate during follow up (13.0% versus 4.9%, p <0.001). In sensitivity analysis, recurrent stroke rate was greater in patients with symptomatic versus asymptomatic stenosis (23.5% vs. 10.4%, p<0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics in patients with and without carotid stenosis ≥ 50%

| Variable | Full cohort (n=3,941) |

Carotid stenosis <50% (n=3,665) |

Carotid stenosis ≥50% (n=276) |

p value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 64.6±13.0 | 64.1±13.0 | 70.3±11.1 | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 2,196 (55.7%) | 2,019 (55.1%) | 177 (64.1%) | 0.004 |

| Race | 0.001 | |||

| White | 2,924 (74.2%) | 2,695 (73.5%) | 229 (83.0%) | |

| Black | 739 (18.8%) | 697 (19.0%) | 42 (15.2%) | |

| Asian | 119 (3.0%) | 118 (3.2%) | 1 (0.4%) | |

| Other | 159 (4.0%) | 155 (4.2%) | 4 (1.5%) | |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 278 (7.1%) | 266 (7.3%) | 12 (4.4%) | 0.069 |

| Final diagnosis of infarct (n=3,937) | 1,498 (38.1%) | 1,351 (36.9%) | 147 (53.3%) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension (n=3,925) | 2,708 (69.0%) | 2,481 (68.0%) | 227 (82.9%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes (n=3,933) | 1,050 (26.7%) | 966 (26.4%) | 84 (30.4%) | 0.145 |

| Atrial fibrillation (n=3,931) | 37 (0.9%) | 34 (0.9%) | 3 (1.1%) | 0.790 |

| Coronary artery disease (n=3,932) | 397 (10.1%) | 343 (9.4%) | 54 (19.7%) | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure (n=3,937) | 99 (2.5%) | 90 (2.5%) | 9 (3.3%) | 0.412 |

| Statin at 7 days from randomization (n=3,911) | 3,107 (79.4%) | 2,860 (78.7%) | 247 (89.8%) | <0.001 |

| Smoking status | <0.001 | |||

| Never | 2,055 (52.2%) | 1,942 (53.0%) | 113 (40.9%) | |

| Past | 1,083 (27.5%) | 986 (26.9%) | 97 (35.1%) | |

| Current | 802 (20.3%) | 736 (20.1%) | 66 (23.9) | |

| NIH Stroke Scale at randomization (n=2,809) | 1, 0-2 | 1, 0-2 | 1, 0-2 | 0.430 |

| First measured systolic blood pressure (n=3,936) | 161.8±27.5 | 161.7±27.5 | 162.5±27.0 | 0.656 |

| First measured diastolic blood pressure (n=3,937) | 88.1±16.8 | 88.3±16.7 | 85.5±17.6 | 0.007 |

| Baseline glucose (n=3,941) | 130.2±60.4 | 129.8±65.8 | 135.0±67.3 | 0.169 |

| Clopidogrel treatment arm | 1,969 (50.0%) | 1,830 (49.9%) | 139 (50.4%) | 0.890 |

| Ischemic stroke during follow-up | 276 (7.0%) | 178 (4.9%) | 36 (13.0%) | <0.001 |

Binary variables presented as n (%); ordinal variables as median, IQR; interval variables as mean±standard deviation. P values for difference between carotid stenosis groups, calculated with the chi-squared test for binary variables, the Wilcoxon rank sum test for ordinal variables, and Student’s t-test for interval variables.

In adjusted models, when compared to patients with <50% carotid stenosis, ischemic stroke risk was increased in patients with ≥50% asymptomatic stenosis (adjusted HR 2.54, 95% CI 1.52-4.23, p<0.001) and symptomatic ≥50% carotid stenosis (adjusted HR 3.50, 95% CI 2.06-5.98, p<0.001), respectively (Supplementary Table II).

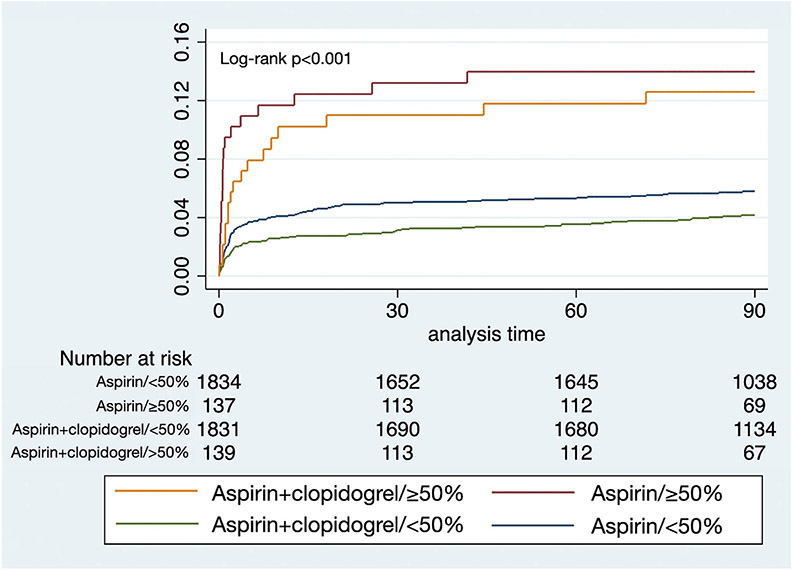

Recurrent ischemic stroke risk reduction by clopidogrel seemed more pronounced in patients without carotid stenosis (adjusted HR 0.68 95% CI 0.50-0.93, p=0.014) as opposed to those with carotid stenosis (adjusted HR 0.88 95% CI 0.45 – 1.72, p = 0.703), but the stenosis*treatment arm interaction was not significant (p = 0.573; Table 2; Figure 1).

Table 2.

Event rates and Cox models showing hazard ratios for the clopidogreal treatment arm, stratified by carotid stenosis <50% versus ≥ 50%, and a model with the interaction term of stenosis*treatment.

| Stratification | Placebo event rate (n, %) |

Clopidogrel event rate (n, %) |

Unadjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) |

p value | Adjusted hazard ratio* (95% CI) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stenosis <50% (n=3,665) |

105/1835, 5.7% | 73/1830, 4.0% | 0.69 (0.51-0.93) |

0.014 | 0.68 (0.50-0.93) |

0.014 |

| Stenosis ≥50% (n=276) |

19/137, 13.9% | 17/139, 12.2% | 0.86 (0.45-1.65) |

0.650 | 0.88 (0.45-1.72) |

0.703 |

| Interaction of stenosis*treatment | 0.573 | |||||

Adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, qualifying event (stroke vs transient ischemic attack), smoking status, diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and statin use.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves for ischemic stroke events within 90 days, shown stratified by stenosis <50% versus ≥ 50% and randomization arms.

We conducted additional analyses by trichotomizing the degree of carotid stenosis to 0% versus 1-49% versus ≥50%. Kaplan-Meier analysis indicated a similar risk of stroke recurrence for patients with 0% versus 1-49% stenosis (Supplemental Figure II).

Discussion

Presence of a ≥50% carotid stenosis among patients with minor-ischemic stroke or high-risk TIA significantly increases the risk for recurrent ischemic stroke; this risk was highest for patients considered to have a symptomatic carotid stenosis. The effect of DAPT on recurrence was not significantly different in patients with or without arterial stenosis, in line with prior studies.5, 6

Patients with high-risk TIA or minor stroke and ≥50% carotid stenosis were at high risk for recurrence despite DAPT, indicating the importance of further secondary prevention strategies. In addition to carotid revascularization when deemed symptomatic, promising approaches include the use of anti-inflammatory drugs (colchicine), novel lipid lowering agents (evolocumab, alirocumab, and ezetimibe), and direct oral anticoagulants.

Strengths of our study relate to the use of data from a large multicenter randomized controlled trial. Limitations include its retrospective nature, modest number of patients with carotid stenosis, exclusion of patients in whom carotid revascularization was planned, as well as lack of data on ischemic stroke mechanism, intracranial stenosis, reasons why patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis were not considered for carotid revascularization, and potential misclassification of carotid artery stenosis as asymptomatic in patients with a TIA.

Conclusion

Presence of carotid stenosis is associated with higher ischemic stroke risk but the effect of clopidogrel versus placebo is not significantly different in patients with versus without carotid stenosis. DAPT is recommended in patients with carotid stenosis who qualify when acute intervention is not anticipated. Further study is required to test the safety and efficacy of DAPT prior to planned carotid intervention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We would like to acknowledge the POINT trial investigators for conducting the study and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) for funding the study.

Funding Sources:

The POINT trial was funded by NIH/NINDS grant 1U01S062835-01A1. This study was partly funded by NIH/NINDS grants K23NS105924 (de Havenon) and K08NS091499 (Henninger). Dr. Johnston received funding from Sanofi.

Disclosures:

Dr. Johnston reports research support from AstraZeneca as well as funding from Sanofi. Dr. de Havenon reports research support from AMAG and Regeneron. Dr. Kim reports funding from SanBio. Dr. Rostanski reports personal expert witness fees outside the submitted work. All other authors report no disclosures.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms:

- CI

Confidence interval

- DAPT

Dual antiplatelet therapy

- HR

Hazard ratio

- POINT

Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke

- TIA

transient ischemic attack

Footnotes

Supplementary Materials: Online Supplementary Tables I and II, Online Supplementary Figures I and II.

References

- 1.Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, Liu L, Wang D, Wang C, Wang C, Li H, Meng X, Cui L, et al. Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;369:11–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnston SC, Easton JD, Farrant M, Barsan W, Conwit RA, Elm JJ, Kim AS, Lindblad AS, Palesch YY. Clopidogrel and aspirin in acute ischemic stroke and high-risk tia. The New England journal of medicine. 2018;379:215–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnston SC, Amarenco P, Denison H, Evans SR, Himmelmann A, James S, Knutsson M, Ladenvall P, Molina CA, Wang Y. Ticagrelor and aspirin or aspirin alone in acute ischemic stroke or tia. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:207–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yaghi S, Rostanski SK, Boehme AK, Martin-Schild S, Samai A, Silver B, Blum CA, Jayaraman MV, Siket MS, Khan M, et al. Imaging parameters and recurrent cerebrovascular events in patients with minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73:572–578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amarenco P, Denison H, Evans SR, Himmelmann A, James S, Knutsson M, Ladenvall P, Molina CA, Wang Y, Johnston SC. Ticagrelor added to aspirin in acute nonsevere ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack of atherosclerotic origin. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2020;51:3504–3513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu L, Wong KS, Leng X, Pu Y, Wang Y, Jing J, Zou X, Pan Y, Wang A, Meng X, et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy in stroke and icas: Subgroup analysis of chance. Neurology. 2015;85:1154–1162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.