Abstract

Exosomes are single-membrane, secreted organelles with a diameter of 30–200 nm, containing diverse bioactive constituents, including DNAs, RNAs, proteins, and lipids, with prominent molecular heterogeneity. Extensive studies indicate that exosomal RNAs (e.g., microRNAs, long non-coding RNAs, and circular RNAs) can interact with many types of cancers, associated with several hallmark features like tumor growth, metastasis, and resistance to therapy. Pancreatic cancer (PaCa) is among the most lethal cancers worldwide, emerging as the seventh foremost cause of cancer-related death in both sexes. Hence, revealing the specific pathogenesis and improving the clinical diagnosis and treatment process are urgently required. As the study of exosomes has become an active area of research, the functional connections between exosomes and PaCa have been deeply investigated. Among these, exosomal RNAs seem to play a significant role in the development, diagnosis, and treatment of PaCa. Exosomal RNAs delivery ultimately modulates the various features of PaCa, and many scholars have interpreted how exosomal RNAs contribute to the proliferation, angiogenesis, migration, invasion, metastasis, immune escape, and drug resistance in PaCa. Besides, recent studies emphasize that exosomal RNAs may serve as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers or therapeutic targets for PaCa. In this review, we will introduce these recent insights focusing on the discoveries of the relationship between exosomal RNAs and PaCa, and the potentially diagnostic and therapeutic applications of exosomes in PaCa.

Keywords: Exosome, Exosomal RNAs, Pancreatic cancer, Biomarker

Background

Pancreatic cancer (PaCa) is among the most common and devastating malignancies worldwide. Globally, there were reported cases 495,773 and reported deaths 466,003 from PaCa in 2020, with approximately as many deaths as cases due to its poor prognosis; it ranks, the seventh foremost cause of cancer-related death for both sexes [1]. PaCa is one of the highest case-fatality cancer types among all solid tumors, as the 5-year survival rate is only 10% [2, 3]. The poor prognosis of PaCa may be attributed to several factors, including a lack of typical symptoms, difficulties in early diagnosis, high metastatic potential, and resistance to conventional treatment. PaCa, which has no significant symptoms in the early stage, is commonly caught late, which causes a delay in treatment [4, 5]. In particular, existing methods, including surgical techniques, chemotherapy, radiation, and immunotherapy, each faces its own challenges, such as recurrence after resection, resistance to chemotherapy and radiation, and uncertainty whether the immunotherapy can be effective for the individual [6, 7]. Hence, it is urgently needed to identify the specific pathogenesis mechanism and facilitate early diagnosis.

Introduction to exosomes

Exosomes, first recognized in the 1980s by Trams et al., are single-membrane, secreted organelles with a diameter of 30–200 nm [8, 9]. Exosomes are membrane-bound extracellular vesicles (EVs) that are produced in the endosomal compartment of most eukaryotic cells. Exosomes contain diverse bioactive constituents, including mRNAs, non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), proteins, and lipids, with prominent molecular heterogeneity [10–13]. Exosomes are originate from double invagination of the membranes of plasma and endosome, and this process is a dedicated mechanism that refers to protein selection, RNA packaging, and EV release [14]. Endosomes form at the plasma membrane or the Golgi, which are membrane-delimited intracellular transport carriers. Once released, exosomes can extend a new paradigm of cell-to-cell communication by transferring those cargoes from donor cells to recipient cells [15]. It is widely documented exosomes are associated with both normal physiology and acquired pathological activities, including but not limited to reproduction, immunity, infection, and tumors [16–19]. As for tumor development, exosomes have diverse activities, such as formation of the tumor microenvironment (TME), initiation, proliferation, angiogenesis, and metastasis [20–22]. Furthermore, the molecular heterogeneity of exosomes has been observed among cancer patients and healthy individuals, and the cargoes and the amounts of exosomes created by the same cell may be dramatically different if educated with different treatments [23–25]. In theory, the heterogeneity of tumor cell-derived exosomes (TDEs) allows them to fulfill diagnostic functions. Cargoes of TDEs, such as microRNAs (miRNAs), long RNAs (lncRNAs), and circular RNAs (circRNAs), have been detected in PaCa and become novel non-invasive biomarkers for PaCa [26, 27]. Moreover, exosomes are emerging as therapeutic tools in several diseases, including PaCa [28, 29]. Therefore, we will summarize the biological activities of exosomal RNAs in the initiation and development of PaCa, and introduce the potential clinical applications of exosomes in PaCa.

Formation, secretion, and uptake of exosomes (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1.

Formation, secretion, and uptake of exosomes

Exosomes are nanosized EVs enriched in specific nucleic acids, lipids, proteins, and glycoconjugates [30]. Overall, exosomes originate from the first invagination of the plasma membrane, giving rise to early endosomes, and the sequential engulfment of cytoplasmic contents to form multivesicular bodies (MVBs). MVBs are named for their appearance, with a specialized subset of endosomes that contain many small vesicles inside the larger body. After fusion with plasma membrane, MVBs are released as intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) [31, 32]. First, the invagination of the cell membrane forms the early endosome, and in this process, the extracellular fluids and constituents (e.g., proteins, lipids, and other metabolites) can be internalized into the early endosome and the cell membrane proteins. Next, MVBs are derived from the subsequent inward invagination of the endosomal membrane, allowing cytoplasmic components to be engulfed into the endosomes and enrich the cargoes of ILVs. Endosomes are membrane-delimited intracellular transport carriers. Three main endosome compartments exist: early, late, and recycling endosomes. Early endosomes mature into late endosomes that subsequently fuse with lysosomes. Recycling endosomes are a sub-compartment of early endosomes that return material to the plasma membrane. Endosomes form at the plasma membrane or the Golgi. MVBs may fuse with lysosomes, and their cargoes will be degraded and recycled. Some MVBs fuse with the cell membrane and are transported into the extracellular milieu as exosomes [33, 34]. Such endosomes are called MVBs because of their appearance, with many small vesicles ILVs, inside the larger body. The ILVs become exosomes if the MVB merges with the cell membrane, releasing the internal vesicles into the extracellular space. Several proteins are indispensable in the formation of exosomes, including endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT), ALG-2 interacting protein X (ALIX), soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptors (SNAREs), tumor susceptibility 101 (TSG101), Rab GTPases, CD9, CD63, and CD81, some of which serve as markers of exosomes [15, 35, 36]. All these proteins play an integral role in the origin or biogenesis of EVs, and the precise functions of these proteins deserve further in-depth investigation. Once secreted into the extracellular milieu or bloodstream, exosomes can be recognized by recipient cells and then dock the cellular membrane, resulting in alterations in the behavior and phenotype of recipient cells [37]. The fate of the exosomes and their effects on recipient cells may vary because of their different cargoes, as the manners of uptake and utilization are complex. Upon docking at the plasma membrane, exosomes can fuse with the cellular membrane and deliver cargoes into the cytoplasm. In this process, recipient cells can internalize exosomes in several possible ways, including phagocytosis, macropinocytosis, caveolae-dependent endocytosis, and clathrin-dependent endocytosis [38, 39]. The different uptake pathways might rely on the types and physiologic state of recipient cells. For example, oncogenic KRAS expression can enhance exosome uptake efficacy by macropinocytosis in PaCa [40]. Cardiomyocytes can uptake circulating exosomal miRNAs via clathrin-mediated endocytosis, and human melanoma cells more readily rely on fusion with the plasma membrane for exosome uptake [41, 42]. After internalization, exosomes can deliver functional cargoes as the endpoint. In many cases, those exosomes can be released de novo by recipient cells, or the contents of exosomes are secreted into the endoplasmic reticulum and/or cytoplasm after the disintegration of intracellular vesicles such as endosomes or MVBs [43]. The different fates may depend on specific ligand receptors on the surface of exosomes and acceptor cells, but the exact mechanisms await further investigation.

Current methods and challenges of the purification of exosomes

As critical mediators of intercellular crosstalk, exosomes exist in virtually all body fluids, and highly purified exosomes are indispensable for further structural and functional study [44]. However, the acquirement of high‐quality exosomes is still challenging due to exosome heterogeneity in the source, size, and content [45]. The International Society for Extracellular Vesicles has suggested that differential ultracentrifugation (DC) is the most frequently used method, with several other methods, such as density gradient ultracentrifugation (DGC), ultrafiltration (UF), precipitation, size-exclusion chromatography (SEC), and immunoaffinity capture [46]. We introduce the principles, advantages, and disadvantages of each of these conventional methods in Table 1. Although these conventional methods are widely available, several problems exist, such as labor- and time-consuming process, co-existence with impurities, and potential risk of exosomal damage. These disadvantages make it challenging to apply in clinical practice, especially for point-of-care testing (POCT). Recently, microfluidic techniques and aptamer-based magnetic techniques have been introduced as novel strategies of exosomal purification, which may provide compensation for the limitations of conventional methods [47, 48]. Microfluidic devices, including physical property-based methods, immune-chips capture, and comprehensive separation, have been developed for exosome purification [49, 50]. Compared with conventional methods, microfluidic techniques have apparent strengths, such as smaller sample volumes, faster assay times, lower reagent volumes, and higher portability. However, several problems are still to be overcome, such as a lack of standardized protocol, further improvement in purity, and additional reduction in cost. Aptamer-based magnetic techniques have been reported to achieve the rapid capture, adequate enrichment, and safe release of exosomes [51]. Therefore, this exosome purification method can potentially be applied to further investigations of exosomes and clinical translation of diagnosis and therapeutics. Nevertheless, there is neither sufficient evidence on the stability nor enough aptamer selection, which has limited the broad adaptability of their applications.

Table 1.

The principles, advantages, and disadvantages of conventional methods of exosomal purification

| Method | Principle | Advantage | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| DC | By sequential increase in the centrifugal force, exosomes can be purified according to size and density |

Suitable for large-volume samples Applied to purifying Exosomes from cell medium, plasma, and urine Relative technical simplicity |

Time and labor cost Expensive equipment Damage due to centrifugal forces Large sample volumes requirement A mix of protein aggregates and lipoproteins |

| DGC | With the sample added to the medium of specific density, exosomes can be purified from multiple contaminants by density, mass, and size | Higher purity than that of DC | Same as those of DC |

| UF | By using a nanomembrane with a specific pore size and molecular weight cut-off, exosomes can be purified according to size or molecular weight |

Saved time and labor consumption Fewer instruments cost Reduced technical difficulty |

Damage to exosomes A mix of impurities with similar size or molecular weight Loss of small size exosomes Membrane blocking |

| SEC | By using a porous stationary phase with a specific pore size, exosomes can be purified while crossing the pores |

Reservation of the biological activity and structural integrity of exosomes Saved time and labor consumption High yields Good reproducibility for purification from serum, plasma, ascites, and saliva |

A mix of albumin and lipoproteins Special equipment |

| Precipitation | With precipitation reagents added to the sample and incubation, exosomes can be enriched from serum or plasma |

Ease of use High yield Lower instruments requirements Commercialization of precipitation kits |

A mix of lipoproteins, proteins, and ectosomes Difficult to remove the reagents from exosomes |

| Immunoaffinity capture | With antibodies that can recognize specific proteins deposited on the surfaces of magnetic beads, exosomes can be purified while modified beads capture the exosomal proteins |

High purity Commercialization of immunoaffinity capture kits Able to separate sub-population exosomes |

Damage due to elution Expensive reagents Low capacity A mix of apoptotic bodies and microvesicles |

DC differential ultracentrifugation, DGC density gradient ultracentrifugation, UF ultrafiltration, SEC size-exclusion chromatography

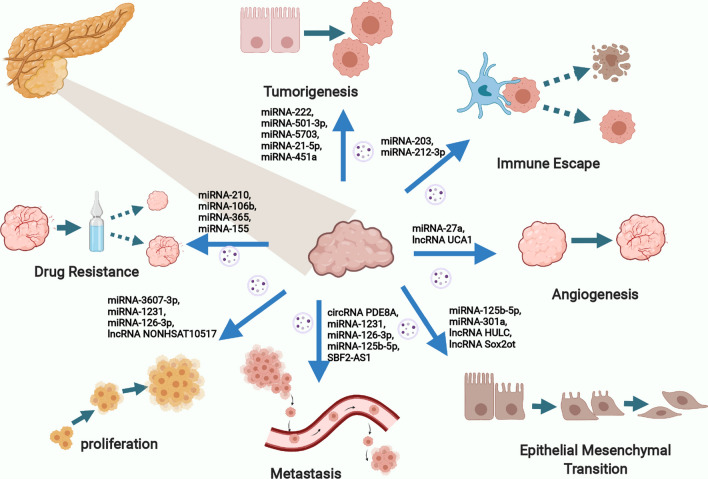

Exosomal RNAs play pivotal roles in PaCa development and progression (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2.

Exosomal RNAs play pivotal roles in Paca development and progression

Exosomes are loaded with multiple cargoes, such as RNAs, DNAs, proteins, and lipids, and thus the delivery of exosomes plays pivotal roles in diverse physiological and pathophysiological processes [9]. Investigations into the correlation between exosomes and tumors have progressed rapidly, which has led to numerous significant discoveries in the development and progression of tumors, including proliferation, apoptosis, angiogenesis, migration, invasion, metastasis, immune escape, and drug resistance [20, 52–56]. Among these, exosomal RNAs have been intensively studied due to their essential roles in regulating all aspects of tumor metabolism and function [57]. In PaCa, cancer cells can be influenced by exosomal RNAs secreted from neighboring cancer cells or other cells, such as pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs), tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), and cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) [58–60]. Exosomal RNA delivery ultimately modulates the various features of PaCa, and many scholars have interpreted the role of exosomal RNAs in PaCa development and progression (Table 2).

Table 2.

Exosomal RNAs involved in the development and progression in PaCa

| RNA Type | Molecules | Origin | Effects | Targets | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA | miRNA-222 | TDEs |

Proliferation ↑ Invasion ↑ |

p27/Akt | [61] |

| miRNA-501-3p | TAMs |

Tumorigenesis ↑ Metastasis ↑ |

TGFBR3/ TGF-β | [62] | |

| miRNA-5703 | PSCs | Proliferation ↑ | CMTM4/PI3K/Akt | [63] | |

| miRNA-3607-3p | NK cells |

Proliferation ↓ Migration ↓ Invasion ↓ |

IL-26 | [64] | |

| miRNA-1231 | BM-MSCs |

Proliferation ↓ Migration ↓ Invasion ↓ |

Not mentioned | [65] | |

| miRNA-126-3p | BM-MSCs |

Proliferation ↓ Migration ↓ Invasion ↓ |

ADAM9 | [66] | |

| miRNA-27a | TDEs | Angiogenesis ↑ | BTG2 | [68] | |

| miRNA-10a-5p | CAFs |

Migration ↑ Invasion ↑ |

VDR | [71] | |

| miRNA-21 | CAFs |

Migration ↑ Invasion ↑ |

Not mentioned | [72] | |

| miRNA-221 | CAFs |

Migration ↑ Invasion ↑ |

NF-κ B/KRAS | [72] | |

| miRNA-21-5p | PSCs |

Proliferation ↑ Migration ↑ |

Not mentioned | [73] | |

| miRNA-451a | PSCs |

Proliferation ↑ Migration ↑ |

Not mentioned | [73] | |

| miRNA-125b-5p | TDEs |

Migration ↑ Invasion ↑ EMT ↑ |

MEK2/ERK2 | [85] | |

| miRNA-301a | TDEs |

Migration ↑ Invasion ↑ EMT ↑ |

PTEN/PI3Kγ | [86] | |

| miRNA-203 | TDEs | Immune Escape ↑ | TNF-α/IL-12/TLR4 | [94] | |

| miRNA-212-3p | TDEs | Immune Escape ↑ | RFXAP/ MHC II | [95] | |

| miRNA-210 | TDEs | GEM-resistance ↑ | mTOR | [99] | |

| miRNA-106b | CAFs | GEM-resistance ↑ | TP53INP1 | [100] | |

| miRNA-365 | TAMs | GEM-resistance ↑ | NTP/CDA | [101] | |

| miRNA-155 | TDEs | GEM-resistance ↑ | SOD/CAT/DCK | [103] | |

| miRNA-194-5p | TDEs | Radiotherapy-resistance ↑ | E2F3 | [105] | |

| lncRNA | UCA1 | TDEs | Angiogenesis ↑ | miRNA-96-5p/AMOTL2 | [69] |

| SBF2-AS1 | TAMs |

Migration ↑ Invasion ↑ Metastasis ↑ |

miRNA-122-5p/XIAP | [74] | |

| HULC | TAMs |

EMT ↑ Invasion ↑ Migration ↑ |

Not mentioned | [75] | |

| NONHSAT105177 | TDEs |

Proliferation ↓ Migration ↓ EMT ↓ |

Clusterin | [76] | |

| Sox2ot | TDEs |

Invasion ↑ Metastasis ↑ EMT ↑ |

miRNA-200 family/ Sox2 | [77] | |

| circRNA | PDE8A | TDEs | Invasion ↑ | miRNA-338/MACC1/MET | [78] |

| IARS | TDEs | Metastasis ↑ | HUVECs | [79] | |

| hsa_circ_0002130 | TDEs | Radiotherapy-resistance ↑ | Not mentioned | [106] |

Proliferation and angiogenesis

Proliferation and angiogenesis are crucial elements in the rapid growth and development of PaCa, contributing to the severity of the disease. Recently, researchers have demonstrated that exosomal RNAs regulate the proliferation of PaCa by influencing the expression of multiple genes and activating different signaling pathways. For instance, tumor-derived exosomal miRNA-222 was reported to promote the proliferation and invasion of PaCa cells via increasing p27 phosphorylation by activating Akt signaling [61]. In another study, TAM-derived exosomal miRNA-501-3p was found to increase tumorigenesis and metastasis through the transforming growth factor-β receptor 3 (TGFBR3) -mediated TGF-β signaling pathway [62]. In addition, PSC-derived exosomal miRNA-5703 was found to promote PaCa proliferation by downregulating CKLF like MARVEL transmembrane domain-containing protein 4 (CMTM4) and activating the PI3K/Akt pathway [63]. Although the origins and targeted signaling pathways vary, exosomal RNAs appear to play multiple crucial roles in PaCa proliferation. In contrast, some exosomal RNAs have opposite effects, such as inducing apoptosis. In this regard, Sun et al. found that natural killer (NK) cell-derived exosomal miRNA-3607-3p inhibits PaCa proliferation, migration, and invasion by targeting IL-26 [64]. Additionally, exosomal miRNA-1231 and miRNA-126-3p, secreted by bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs), are implicated in inhibiting the proliferation, migration, and invasion of PaCa cells [65, 66]. Likewise, miRNA-126-3p promotes the apoptosis of PaCa cells by silencing of a disintegrin and a metalloproteinase 9 (ADAM9)[66]. In summary, exosomal RNAs are capable of both promoting and inhibiting carcinogenesis depending on their different mechanisms. As a unique link between proliferation and apoptosis, angiogenesis is deeply involved in tumor growth and metastatic dissemination [67]. Several exosomal RNAs have been identified to be associated with angiogenesis in PaCa. Tumor-derived exosomal miRNA-27a was found to promote angiogenesis in PaCa via B-cell translocation gene 2 (BTG2) [68]. Additionally, hypoxic tumor-derived exosomal lncRNA urothelial cancer-associated 1 (UCA1) was shown to promote angiogenesis via miRNA-96-5p/AMOTL2 (angiomotin-like 2) in PaCa [69]. Above all, these studies show how exosomal RNAs with different functions from diverse origins can affect tumor growth. However, we cannot attribute the poor prognosis only to the presence of highly proliferative cancer cells, as the prognosis is affected by multiple factors, including migration, invasion, metastasis, immune escape, and drug resistance.

Migration, invasion, and metastasis

PaCa is characterized by aggressive features including migration, invasion, and metastasis, which always cause early treatment failure [58]. With these features, cancer cells are able to move to adjacent and distant areas and even settle in secondary tissues and organs [70]. As mentioned above, several exosomal RNAs (including miRNA-222, miRNA-501-3p, miRNA-5703, miRNA-3607-3p, miRNA-1231, miRNA-126-3p) have been found to promote or inhibit PaCa migration, invasion, and metastasis [61–66]. Additionally, CAF-secreted exosomal miRNA-10a-5p was found to promote migration and invasion in PaCa cells, while activating vitamin D receptor (VDR) signaling could inhibit these supportive effects on PaCa cells [71]. Similarly, CAF-derived exosomal miRNA-21, miRNA-221, PSC-derived exosomal miRNA-21-5p, and miRNA-451a were reported to confer aggressive features in PaCa cells [72, 73]. In the context of inhibitory effects, NK cell-derived exosomal miRNA-3607-3p was reported to inhibit the migration and invasion of PaCa cells by directly targeting IL-26 [64]. In addition, BM-MSCs-derived exosomal miRNA-1231 and miRNA-126-3p were also indicated to act inhibitory roles of the migration and invasion of PaCa cells [65, 66]. Interestingly, exosomal lncRNAs and circRNAs seem to be more active in migration, invasion, and metastasis than that in proliferation in PaCa. Tumor-derived exosomal lncRNA SBF2 antisense RNA 1 (SBF2-AS1), highly upregulated in liver cancer (HULC), NONHSAT105177, SOX2 overlapping transcript (Sox2ot), circRNA phosphodiesterase 8A (PDE8A), and isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase (IARS) have already been reported to affect the migration, invasion, and metastasis of PaCa cells [74–79]. Naturally, exosomal RNAs can also act as suppressive factors, as mentioned above. Thus, exosomal RNAs can act as major regulators of migration, invasion, and metastasis, promoting (or inhibiting) the progression of PaCa. Moreover, epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a special biological process involved in the migration, invasion, and metastasis [80]. In this process, in which epithelial cells become mesenchymal cells via loss of cell polarity and gain of molecular alterations [81].EMT is characterized by the loss of epithelial E-cadherin and the acquisition of mesenchymal markers such as N-cadherin, fibronectin, and vimentin [82–84]. Recently, several exosomal RNAs have been reported to promote EMT in PaCa [29]. For instance, tumor-derived exosomal miRNA-125b-5p was found to be upregulated in highly invasive PaCa cells, facilitating migration, invasion, and EMT via the activation of MEK2/ERK2 signaling [85]. In addition, exosomal miRNA-301a, lncRNA HULC, and NONHSAT105177 were also reported to contribute to EMT in PaCa [75, 76, 86]. Above all, we believe that these findings will be of great value if these factors are applied as targets for therapeutic intervention.

Immune escape

The immune system is a complicated network of diverse cells and biomolecules that prospect the body against infection, cancer, and other harmful circumstances. Gene mutations and the abnormal proliferation of cancer cells can produce different types of antigens; these antigens allow the detection and elimination of cancer cells by a large variety of immune response factors, preventing potential malignant transformation. Exosomes have been previously well studied in the context of the immune response, and scholars have proposed many mechanisms that explain how cancer cells promote immune escape and cancer development [18, 87, 88]. Several studies have pointed out that tumor-derived exosomes realized immune escape by inhibiting the activation of immune cells, causing a functional loss in immune responses[89–92]. Dendritic cells (DCs) serve as the most critical antigen-presenting cells (APCs) of the human immune system, and they function by promoting the expression of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and generating multiple interleukins (ILs). Among TLRs, TLR4 exhibits a powerful antitumor effect [93]. In PaCa, tumor-derived exosomal miRNA-203 was reported to downregulate TLR4 and downstream tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and IL-12 in DCs, which may help PaCa cells achieve immune escape [94]. In another study, tumor-derived exosomal miRNA-212-3p was found to inhibit the expression of RFX-associated protein (RFXAP), which decreased the expression of major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II) and mediated the immune tolerance of DCs [95]. These findings infer that exosomal RNAs can harbor functional immune activity, allowing PaCa cells to escape immune surveillance. However, relative to that in other research areas, our knowledge about how exosomes help cancers cells escape the immune system in PaCa is still limited, and additional work is needed to address this issue. Deeper insight into the relationship between exosomes and immune escape is likely to be beneficial for the identification of potential biomarkers and the development of therapeutics.

Drug resistance

Systemic chemotherapy combinations, including gemcitabine (GEM) plus other drugs, are still the cornerstone of treatment for advanced PaCa [3], while drug resistance remains a severe challenge in the context of antitumor therapy. To our knowledge, cancer cells can develop drug resistance via enhanced DNA repair, altered membrane transport, defective apoptotic pathways, etc. [96]. The effect of exosomes in the process cannot be ignored. In normal cells, exosomes are responsible for the transport of many cargoes from one cell to another. Studies have demonstrated that, once drug-resistant cancer cells develop, exosomes loaded with so-called “anti-chemotherapy” information can confer drug resistance to sensitive cells [97, 98]. In PaCa, several exosomal RNAs have been discovered to play essential roles in drug resistance. For example, exosomes derived from GEM-resistant PaCa cells were found to enhance the drug resistance of other cancer cells by delivering miRNA-210 [99]. Another study indicated that CAF-derived exosomal miRNA-106b promoted PaCa GEM-resistance via tumor protein 53-induced nuclear protein 1 (TP53INP1) [100]. Likewise, the delivery of miRNA-365 in TAM-derived exosomes was shown to potentiate the GEM-response in PaCa[101]. Notably, with a series of successive validation studies, tumor-derived exosomal miRNA-155 was proven to be a vital related to GEM-resistance [102, 103]. These studies highlight the relationship between exosomal RNAs and GEM-resistance that exosomal RNAs can accelerate the acquisition of GEM-resistance and mitigate the cell-killing effect. In addition to newer therapeutic strategies, chemotherapy and radiotherapy still have considerable prospects for PaCa [104]. Similar to their regulatory roles in drug resistance, exosomal RNAs can also impact the outcome of radiotherapy. It has been reported that dying post-radiotherapy PaCa cells can deliver exosomal miRNA-194-5p to potentiate cell repopulation survival by modulating the expression of E2F transcription factor 3 (E2F3) [105]. In another study, exosomal hsa_circ_0002130 was considered to modulate cancer cell repopulation after radiation [106]. Overall, exosomal RNAs are related to the emergence of both drug resistance and radiotherapy resistance, and we believe that novel treatments targeting exosome‐specific therapeutic resistance markers will be developed soon.

Exosomal RNAs as potential biomarkers for PaCa

With very few specific symptoms in the early period, PaCa is often diagnosed in an advanced stage, which leads to a high fatality rate [107]. Traditional imaging examinations, such as ultrasound, CT, and MRI, are widely used in the clinical evaluation of PaCa. Although CA-199 is the only FDA-approved biomarker of PaCa, its accuracy is far from satisfactory due to the poor sensitivity at an early stage and the relatively low specificity overall [108–110]. Therefore, a more precise method is urgently needed for non-invasive diagnosis. As mentioned earlier, exosomes are enriched with biological cargoes, so they have gained interest as potential biomarkers for the early diagnosis of multiple malignancies [111]. Among these, exosomal RNAs are emerging as novel biomarkers for PaCa (Table 3). Accumulated evidence has revealed that exosomal RNAs can be more valuable in diagnosis than peripheral blood-free RNA as they have several advantages: exosomes can prevent RNAs from being degraded via RNases; exosomal RNAs are more closely associated with those of the original cells; and there is a higher concentration of RNAs in exosomes, which can yield more information [112–114].

Table 3.

Exosomal RNAs as biomarkers for Paca

| RNA Type | Molecules | Origin | Potential functions | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA | miRNA‑21 | Peripheral blood | Early diagnosis/tumor stage/survival evaluation | [116–119] |

| miRNA-210 | Peripheral blood | Early diagnosis/tumor stage | [116] | |

| miRNA-10b | Peripheral blood | Early diagnosis | [117, 120] | |

| miRNA-1246 | Peripheral blood | Early diagnosis | [121] | |

| miRNA-451a | Peripheral blood | Tumor stage/survival evaluation | [122] | |

| miRNA-222 | Peripheral blood | Tumor stage/survival evaluation | [61] | |

| miRNA-4525 | Portal vein blood | Recurrence prediction/survival evaluation | [124] | |

| miRNA-451a | Portal vein blood | Recurrence prediction/survival evaluation | [124] | |

| miRNA-21 | Portal vein blood | Recurrence prediction/survival evaluation | [124] | |

| miRNA-21 | Pancreatic juice | Early diagnosis | [125] | |

| miRNA-155 | Pancreatic juice | Early diagnosis | [125] | |

| miRNA-1246 | Salivary | Early diagnosis | [126] | |

| miRNA-4644 | Salivary | Early diagnosis | [126] | |

| lncRNA | Sox2ot | Peripheral blood | Tumor stage/survival evaluation | [77] |

| HULC | Peripheral blood | Early diagnosis | [75] | |

| CRNDE | Peripheral blood | Early diagnosis | [136] | |

| MALAT-1 | Peripheral blood | Early diagnosis | [136] | |

| circRNA | PDE8A | Peripheral blood | Tumor stage/survival evaluation | [78] |

| IARS | Peripheral blood | Tumor stage/survival evaluation | [79] | |

| mRNA | WASF2 | Peripheral blood | Early diagnosis/tumor stage/ | [139] |

| GPC1 | Peripheral blood | Early diagnosis/tumor stage/ | [140] |

Among all exosomal cargoes, exosomal miRNAs are currently regarded as the most promising biomarkers because of their abundance and easy accessibility, indicating that they can be used as potential diagnostic tools; in addition, they are closely related to the outcome and recurrence of PaCa [115]. For example, several studies indicated that elevated exosomal miRNA‑21 levels can not only discriminate PaCa patients from healthy individuals and patients with other pancreatic diseases (e.g., chronic pancreatitis and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm) but can also help make an early diagnosis and evaluate tumor stage [116–119]. Moreover, other exosomal miRNAs, including miRNA-210, miRNA-10b, miRNA-451a and miRNA-1246, can be applied for the accurate and early diagnosis of PaCa [116, 117, 120, 121]. Notably, some exosomal miRNAs may be correlated with tumor recurrence or may even be independent prognostic factors for PaCa. For instance, high-level expression of exosomal miRNA-451a was found to be associated with an increased risk of cancer recurrence and poorer prognosis in PaCa [122]. Similarly, another study illustrated that a higher exosomal miRNA-222 level was one of the independent risk factors for PaCa patients, which could reflect an enlarged tumor size and a high TNM stage [61]. Apart from peripheral blood, exosomes collected from other bodily fluids may also contribute to PaCa diagnosis and prognosis prediction [123]. First, portal vein blood assessment of exosomal miRNA-4525, miRNA-451a, and miRNA-21 was confirmed to outperform peripheral blood assessment evaluating both disease-free survival and overall survival in PaCa patients [124]. Next, pancreatic juice exosomal miRNA-21 and miRNA-155 levels were shown to discriminate PaCa patients from chronic pancreatitis patients with better performance than blood-free exosomal miRNA and CA-199 levels [125]. In addition, salivary miRNA-1246 and miRNA-4644 were found to be promising biomarkers for PaCa [126]. Naturally, some researchers preferred combinations of multiple exosomal miRNAs or of exosomal miRNAs and other biomarkers to achieve better diagnostic yield in PaCa evaluation [127–129]. For example, a 3D microfluidic chip was designed to assess multiple exosomal biomarkers including surface proteins (CD81, EphA2, and CA-199) and exosomal miRNAs (miRNA-451a, miRNA-21, and miRNA-10b), and the accuracy of diagnosis and stage monitoring reached up to approximately 100% [130]. In another study, a six-miRNA panel, including let-7b-5p, miRNA-192-5p, miRNA-19a-3p, miRNA-19b-3p, miRNA-223-3p, and miRNA-25-3p, was introduced to facilitate early and noninvasive diagnosis of PaCa early from both serum and exosomal specimens [131]. In addition to improving diagnostic yield, researchers have introduced many new techniques to better detect exosomal RNAs [132–134]. Typically, Pang et al. invented a biosensor for one-step detection of exosomal miRNAs, which could be of great value for applying point-of-care cancer diagnosis in terms of accuracy and convenience [135]. Overall, we believe that exosomal miRNAs can certainly be applied to improve the diagnosis and prognosis of PaCa.

Although existing studies on exosomal lncRNAs, circRNAs, and mRNAs are limited compared to those on exosomal miRNAs, these molecules can also facilitate PaCa diagnosis. Some scholars have suggested that many exosomal lncRNAs serve as tumor biomarkers for PaCa. For example, high expression of Sox2ot in plasma exosomes was shown to predict late TNM stage and poor survival in PaCa patients [77]. Additionally, exosomal lncRNA HULC, colorectal neoplasia differentially expressed (CRNDE), and metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (MALAT-1) were proven to have potential value in discriminating PaCa from other pancreatic diseases [75, 136]. Exosomal circRNAs are another kind of endogenous non-coding RNAs, and information on their importance in tumors and other diseases is emerging [137, 138]. In PaCa, both exosomal circRNA PDE8A and IARS are correlated with progression and prognosis [78, 79]. Studies have proposed that exosomal circRNAs will soon serve as novel biomarkers for PaCa. Moreover, exosomal mRNAs have recently been discovered as potential diagnostic biomarkers. For example, exosomal mRNA Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein Verprolin-homologous protein 2 (WASF2) provided excellent accuracy for distinguishing PaCa patients from healthy individuals, and distinguishing PaCa patients between stage 0/I/IIA and stage IIB/III/IV [139]. Another exosomal mRNA, glypican-1 (GPC1), provided excellent diagnostic performance in differentiating PaCa patients from patients with other pancreatic diseases and from healthy individuals, approaching 100% sensitivity and specificity [140].

Above all, exosomal RNAs are implied to be potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for PaCa, as summarized in Table 3. With the emphasis on their potential value as PaCa biomarkers, we still need more experiments to verify their significance in the diagnosis and prognosis evaluation of PaCa. Ultimately, there remains an endless challenge to identify additional sensitive and specific exosomal biomarkers with the growth of our knowledge in the field of exosomes. Even though substantial advancements have been achieved, there is a long path ahead before discovering a perfect PaCa biomarker.

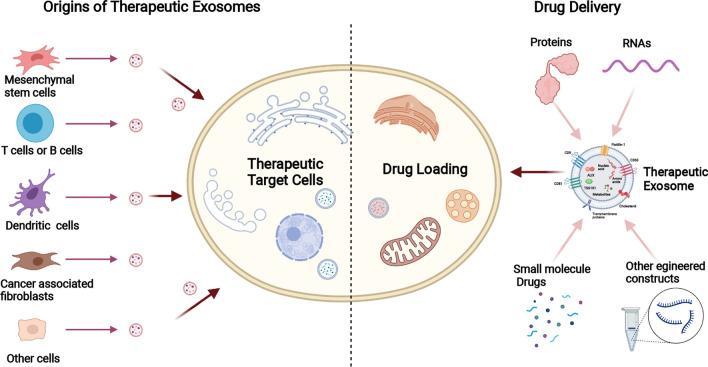

The therapeutic value of exosomes in the treatment of PaCa

PaCa is one of the deadliest malignant tumors, and thus scientists have devoted significant efforts to seek better-targeted therapies [141, 142]. With the function of drug-payload delivery, exosomes have been increasingly explored as therapeutic agents [14, 143] (Fig. 3). Among all the drug cargoes loaded into exosomes, nucleic acids, especially miRNAs, small interfering RNA (siRNA), and hairpin RNA (shRNA), are the most favorite constructs [144]. Generally, those cargoes can be loaded into exosomes either before or after purification. In most cases, those cargoes can be loaded via incubation, transfection-based methods, or ultraviolet irradiation before purification [145–147]; whereas after purification, they can be loaded into exosomes by either physical methods (such as electroporation, plain incubation, and sonication), or chemical procedures (such as transfection kit, and mix with organic solvent) [148–152]. In contrast to previous drug carriers (e.g., liposomes), injected exosomes can be taken up by other cells more effectively and confer bioactive cargoes with less immune interference [23, 153, 154]. In addition, the heterogeneity of surface molecules on exosomes is more suitable for receptor-targeted features, which realize exosome-targeted therapy [155]. Hence, the therapeutic utilization of exosomes as nanocarriers has excellent potential. Currently, researchers are committed to engineering exosomes for the encapsulation of therapeutic ingredients. For example, Zhou et al. loaded purified exosomes with paclitaxel and gemcitabine monophosphate, and these exosomes showed extraordinary penetrating abilities and yielded excellent targeted chemotherapy efficacy [156]. It is well known that the KRAS gene is closely associated with cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation, so multiple studies have been conducted on the KRAS gene. Kamerkar et al. engineered exosomes to deliver siRNA or shRNA targeting KRAS in PaCa cells, which successfully inhibited tumor growth in mouse models and improved overall survival [40]. Likewise, Mendt et al. engineered exosomes with siRNA to target KRAS G12D, which increased the survival of several mouse models with Paca [157]. Moreover, the MD Anderson Cancer Center is leading a phase I clinical trial of MSC-derived exosomes with KRAS G12D siRNA to treat patients with KRAS G12D mutation–associated PaCa (NCT03608631).

Fig. 3.

The potential of exosomes to act as therapeutic vehicles

Regardless of the exciting progress and these pioneering developments, using engineered exosomes as vehicles in the clinical treatment of PaCa still presents several challenges. First, it is not easy to ensure the homogeneity of the treatment effect of different exosomes, as the alignments probably having varying degrees of the same therapeutic implication. Subsequently, the present isolation techniques of exosomes are relatively suboptimal for the requirement of immunotherapy. Overall, increasing studies and achievements in exosome extraction techniques will facilitate the application of exosomes in the clinical treatment of PaCa.

Conclusions and perspective

Above all, exosomes are special vesicles that mediate diverse biological functions. In this review, we highlighted the vital role of exosomal RNAs in PaCa. These discoveries may spark more studies to elucidate the pathogenesis and mechanism of PaCa, offering a new direction and important guidance for the diagnosis and treatment of PaCa. Nevertheless, the question remains whether observed biological activities, including the phenotypic and molecular alterations, can still persist under physiological conditions, which merits further validation.

Characterized by high specificity and minimally invasive nature, exosomal RNAs exhibit outstanding value as potential biomarkers for PaCa. However, large-scale studies are warranted to validate the clinical application of exosomal RNAs. To gain a greater value of the management of PaCa, exosomal RNAs may need to be more intensively studied to develop new utilities monitoring the outcome of therapy. In addition to simple prediction of recurrence and prognosis, if we can adjudicate a certain recurrence, judge the existence of metastasis, observe the therapeutic efficacy, or even determine the length of survival by just testing a specific exosomal RNA (or a set of exosomal RNAs), it will be of great convenience for both the patients and doctors. In terms of therapeutic applications of exosomes (represented by engineered exosomes), several major challenges remain for investigators, such as the evaluation of adverse effects and the identification of tolerated doses. In addition, it is vital to discover more active pharmaceutical ingredients, and identify their specific mechanisms, ensuring the homogeneity of in the treatment effect. Finally, back to the basics, the acquirement of high‐quality exosomes is still challenging, and several obstacles are still formidable, including standardization, improvements in throughput and purity, cost reduction, and increased exosome recovery. These problems, when resolved, will bring the bottom-up promotion to the application of exosomes to every degree.

Acknowledgements

Many important contributions could not be cited due to space constraints, and we apologize to our colleagues for any relevant exclusion. The figures in this manuscript were created with BioRender.com

Abbreviations

- PaCa

Pancreatic cancer

- ncRNAs

Non-coding RNAs

- EVs

Extracellular vesicles

- TME

Tumor microenvironment

- TDEs

Tumor cell-derived exosomes

- miRNAs

MicroRNAs

- lncRNAs

Long non-coding RNAs

- circRNAs

Circular RNAs

- MVBs

Multivesicular bodies

- ILVs

Intraluminal vesicles

- ESCRT

Endosomal sorting complex required for transport

- ALIX

ALG-2 interacting protein X

- SNAREs

Soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptors

- TSG101

Tumor susceptibility 101

- DC

Differential ultracentrifugation DGC: density gradient ultracentrifugation

- UF

Ultrafiltration

- SEC

Size-exclusion chromatography

- POCT

Point-of-care testing

- PSCs

Pancreatic stellate cells

- TAMs

Tumor-associated macrophages

- CAFs

Cancer-associated fibroblasts

- PPP2R2A

Protein phosphatase 2 regulatory subunit Balpha

- Akt

Protein kinase B

- TGFBR3

Transforming growth factor-β receptor 3

- PI3K

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- CMTM4

CKLF like MARVEL transmembrane domain-containing protein 4

- NK cell

Natural killer cell

- BM-MSCs

Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- ADAM9

A disintegrin and a metalloproteinase 9

- BTG2

B-cell translocation gene 2

- UCA1

Urothelial cancer-associated 1

- AMOTL2

Angiomotin-like 2

- VDR

Vitamin D receptor

- SBF2-AS1

SBF2 antisense RNA 1

- HULC

Highly upregulated in liver cancer

- Sox2ot

SOX2 overlapping transcript

- PDE8A

Phosphodiesterase 8A

- IARS

Isoleucyl-tRNA synthetizes

- EMT

Epithelial–mesenchymal transition

- MEK2

Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 2

- ERK2

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 PTEN: Phosphatase and tensin homolog

- MACC

Metastasis-associated in colon cancer

- MET

MET proto-oncogene, receptor tyrosine kinase

- HUVECs

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- DCs

Dendritic cells

- APCs

Antigen-presenting cells

- TLRs

Toll-like receptors

- ILs

Interleukins TNF: Tumor necrosis factor

- RFXAP

RFX-associated protein

- MHC II

Major histocompatibility complex class II

- GEM

Gemcitabine

- mTOR

Mammalian target of rapamycin

- TP53INP1

Tumor protein 53-induced nuclear protein 1

- NTP

Nucleoside triphosphate

- CDA

Cytidine deaminase

- SOD

Superoxide dismutase 2

- CAT

Catalase

- DCK

Deoxycytidine kinase

- E2F3

E2F transcription factor 3

- CA-199

Carbohydrate antigen 199 XIAP: X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein

- EphA2

Ephrin type-A receptor 2

- IPMN

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm

- CP

Chronic pancreatitis

- CRNDE

Colorectal neoplasia differentially expressed

- MALAT-1

Metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1

- WASF2

Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome Protein Family Member 2

- GPC1

Glypican-1

- siRNA

Small interfering RNA

- shRNA

Small hairpin RNA

Authors’ contributions

ZZ and GZ conceived of the presented idea. ZZ wrote the manuscript with support from GZ, SY, and SZ (Shengtao Zhu). SZ (Shutian Zhang) and PL supervised the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (82070575), and Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation (J180010).

Availability of data and materials

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate:

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Guiping Zhao, Email: zhaoguiping@ccmu.edu.cn.

Peng Li, Email: lipeng@ccmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viale PH. The American Cancer Society's facts & figures: 2020 edition. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2020;11(2):135–136. doi: 10.6004/jadpro.2020.11.2.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mizrahi JD, Surana R, Valle JW, Shroff RT. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 2020;395(10242):2008–2020. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30974-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henrikson NB, Aiello Bowles EJ, Blasi PR, Morrison CC, Nguyen M, Pillarisetty VG, Lin JS. Screening for pancreatic cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2019;322(5):445–454. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.6190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Force USPST. Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, Barry MJ, Cabana M, Caughey AB, Curry SJ, Doubeni CA, Epling JW, Jr, et al. Screening for pancreatic cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. JAMA. 2019;322(5):438–444. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.10232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuehn BM. Looking to long-term survivors for improved pancreatic cancer treatment. JAMA. 2020;324(22):2242–2244. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.21717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sohal DPS, Kennedy EB, Cinar P, Conroy T, Copur MS, Crane CH, Garrido-Laguna I, Lau MW, Johnson T, Krishnamurthi S, et al. Metastatic pancreatic cancer: ASCO guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:3217–3230. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.01364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trams EG, Lauter CJ, Salem N, Jr, Heine U. Exfoliation of membrane ecto-enzymes in the form of micro-vesicles. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;645(1):63–70. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(81)90512-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pegtel DM, Gould SJ. Exosomes. Annu Rev Biochem. 2019;88:487–514. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-013118-111902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lasda E, Parker R. Circular RNAs co-precipitate with extracellular vesicles: a possible mechanism for circRNA clearance. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(2):e0148407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Balkom BW, Eisele AS, Pegtel DM, Bervoets S, Verhaar MC. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of small RNAs in human endothelial cells and exosomes provides insights into localized RNA processing, degradation and sorting. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4:26760. doi: 10.3402/jev.v4.26760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pathan M, Fonseka P, Chitti SV, Kang T, Sanwlani R, Van Deun J, Hendrix A, Mathivanan S. Vesiclepedia 2019: a compendium of RNA, proteins, lipids and metabolites in extracellular vesicles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D516–D519. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keerthikumar S, Chisanga D, Ariyaratne D, Al Saffar H, Anand S, Zhao K, Samuel M, Pathan M, Jois M, Chilamkurti N, et al. ExoCarta: a web-based compendium of exosomal Cargo. J Mol Biol. 2016;428(4):688–692. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalluri R, LeBleu VS. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science. 2020;367(6478):eaau6977. doi: 10.1126/science.aau6977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mathieu M, Martin-Jaular L, Lavieu G, Thery C. Specificities of secretion and uptake of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles for cell-to-cell communication. Nat Cell Biol. 2019;21(1):9–17. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0250-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rajagopal C, Harikumar KB. The origin and functions of exosomes in cancer. Front Oncol. 2018;8:66. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Y, Hu YW, Zheng L, Wang Q. Characteristics and roles of exosomes in cardiovascular disease. DNA Cell Biol. 2017;36(3):202–211. doi: 10.1089/dna.2016.3496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurywchak P, Tavormina J, Kalluri R. The emerging roles of exosomes in the modulation of immune responses in cancer. Genome Med. 2018;10(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s13073-018-0535-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foster BP, Balassa T, Benen TD, Dominovic M, Elmadjian GK, Florova V, Fransolet MD, Kestlerova A, Kmiecik G, Kostadinova IA, et al. Extracellular vesicles in blood, milk and body fluids of the female and male urogenital tract and with special regard to reproduction. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2016;53(6):379–395. doi: 10.1080/10408363.2016.1190682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stefanius K, Servage K, de Souza Santos M, Gray HF, Toombs JE, Chimalapati S, Kim MS, Malladi VS, Brekken R, Orth K. Human pancreatic cancer cell exosomes, but not human normal cell exosomes, act as an initiator in cell transformation. Elife. 2019;8:e40226. doi: 10.7554/eLife.40226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang H, Deng T, Liu R, Bai M, Zhou L, Wang X, Li S, Wang X, Yang H, Li J, et al. Exosome-delivered EGFR regulates liver microenvironment to promote gastric cancer liver metastasis. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15016. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Costa-Silva B, Aiello NM, Ocean AJ, Singh S, Zhang H, Thakur BK, Becker A, Hoshino A, Mark MT, Molina H, et al. Pancreatic cancer exosomes initiate pre-metastatic niche formation in the liver. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17(6):816–826. doi: 10.1038/ncb3169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barile L, Vassalli G. Exosomes: therapy delivery tools and biomarkers of diseases. Pharmacol Ther. 2017;174:63–78. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang M, Ji S, Shao G, Zhang J, Zhao K, Wang Z, Wu A. Effect of exosome biomarkers for diagnosis and prognosis of breast cancer patients. Clin Transl Oncol. 2018;20(7):906–911. doi: 10.1007/s12094-017-1805-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang H, Lu Z, Zhao X. Tumorigenesis, diagnosis, and therapeutic potential of exosomes in liver cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12(1):133. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0806-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng J, Hernandez JM, Doussot A, Bojmar L, Zambirinis CP, Costa-Silva B, van Beek E, Mark MT, Molina H, Askan G, et al. Extracellular matrix proteins and carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecules characterize pancreatic duct fluid exosomes in patients with pancreatic cancer. HPB (Oxford) 2018;20(7):597–604. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2017.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melo SA, Luecke LB, Kahlert C, Fernandez AF, Gammon ST, Kaye J, LeBleu VS, Mittendorf EA, Weitz J, Rahbari N, et al. Glypican-1 identifies cancer exosomes and detects early pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2015;523(7559):177–182. doi: 10.1038/nature14581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Su D, Tsai HI, Xu Z, Yan F, Wu Y, Xiao Y, Liu X, Wu Y, Parvanian S, Zhu W, et al. Exosomal PD-L1 functions as an immunosuppressant to promote wound healing. J Extracell Vesicles. 2019;9(1):1709262. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2019.1709262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ariston Gabriel AN, Wang F, Jiao Q, Yvette U, Yang X, Al-Ameri SA, Du L, Wang YS, Wang C. The involvement of exosomes in the diagnosis and treatment of pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer. 2020;19(1):132. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-01245-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han C, Kang H, Yi J, Kang M, Lee H, Kwon Y, Jung J, Lee J, Park J. Single-vesicle imaging and co-localization analysis for tetraspanin profiling of individual extracellular vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles. 2021;10(3):e12047. doi: 10.1002/jev2.12047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor DD, Gercel-Taylor C. The origin, function, and diagnostic potential of RNA within extracellular vesicles present in human biological fluids. Front Genet. 2013;4:142. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hessvik NP, Llorente A. Current knowledge on exosome biogenesis and release. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2018;75(2):193–208. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017-2595-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Niel G, D'Angelo G, Raposo G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19(4):213–228. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kahlert C, Kalluri R. Exosomes in tumor microenvironment influence cancer progression and metastasis. J Mol Med (Berl) 2013;91(4):431–437. doi: 10.1007/s00109-013-1020-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ciardiello C, Cavallini L, Spinelli C, Yang J, Reis-Sobreiro M, de Candia P, Minciacchi VR, Di Vizio D. Focus on extracellular vesicles: new frontiers of cell-to-cell communication in cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(2):175. doi: 10.3390/ijms17020175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bebelman MP, Smit MJ, Pegtel DM, Baglio SR. Biogenesis and function of extracellular vesicles in cancer. Pharmacol Ther. 2018;188:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mulcahy LA, Pink RC, Carter DR. Routes and mechanisms of extracellular vesicle uptake. J Extracell Vesicles. 2014;3:24641. doi: 10.3402/jev.v3.24641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tian T, Zhu YL, Zhou YY, Liang GF, Wang YY, Hu FH, Xiao ZD. Exosome uptake through clathrin-mediated endocytosis and macropinocytosis and mediating miR-21 delivery. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(32):22258–22267. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.588046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feng D, Zhao WL, Ye YY, Bai XC, Liu RQ, Chang LF, Zhou Q, Sui SF. Cellular internalization of exosomes occurs through phagocytosis. Traffic. 2010;11(5):675–687. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kamerkar S, LeBleu VS, Sugimoto H, Yang S, Ruivo CF, Melo SA, Lee JJ, Kalluri R. Exosomes facilitate therapeutic targeting of oncogenic KRAS in pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2017;546(7659):498–503. doi: 10.1038/nature22341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eguchi S, Takefuji M, Sakaguchi T, Ishihama S, Mori Y, Tsuda T, Takikawa T, Yoshida T, Ohashi K, Shimizu Y, et al. Cardiomyocytes capture stem cell-derived, anti-apoptotic microRNA-214 via clathrin-mediated endocytosis in acute myocardial infarction. J Biol Chem. 2019;294(31):11665–11674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.007537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parolini I, Federici C, Raggi C, Lugini L, Palleschi S, De Milito A, Coscia C, Iessi E, Logozzi M, Molinari A, et al. Microenvironmental pH is a key factor for exosome traffic in tumor cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(49):34211–34222. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.041152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Corbeil D, Santos MF, Karbanova J, Kurth T, Rappa G, Lorico A. Uptake and fate of extracellular membrane vesicles: nucleoplasmic reticulum-associated late endosomes as a new gate to intercellular communication. Cells. 2020;9(9):1931. doi: 10.3390/cells9091931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wallis R, Josipovic N, Mizen H, Robles-Tenorio A, Tyler EJ, Papantonis A, Bishop CL. Isolation methodology is essential to the evaluation of the extracellular vesicle component of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. J Extracell Vesicles. 2021;10(4):e12041. doi: 10.1002/jev2.12041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ding L, Yang X, Gao Z, Effah CY, Zhang X, Wu Y, Qu L. A holistic review of the state-of-the-art microfluidics for exosome separation: an overview of the current status, existing obstacles, and future outlook. Small. 2021 doi: 10.1002/smll.202007174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thery C, Witwer KW, Aikawa E, Alcaraz MJ, Anderson JD, Andriantsitohaina R, Antoniou A, Arab T, Archer F, Atkin-Smith GK, et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J Extracell Vesicles. 2018;7(1):1535750. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2018.1535750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin S, Yu Z, Chen D, Wang Z, Miao J, Li Q, Zhang D, Song J, Cui D. Progress in microfluidics-based exosome separation and detection technologies for diagnostic applications. Small. 2020;16(9):e1903916. doi: 10.1002/smll.201903916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang K, Yue Y, Wu S, Liu W, Shi J, Zhang Z. Rapid capture and nondestructive release of extracellular vesicles using aptamer-based magnetic isolation. ACS Sens. 2019;4(5):1245–1251. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.9b00060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang F, Liao X, Tian Y, Li G. Exosome separation using microfluidic systems: size-based, immunoaffinity-based and dynamic methodologies. Biotechnol J. 2017;12(4):1600699. doi: 10.1002/biot.201600699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liga A, Vliegenthart AD, Oosthuyzen W, Dear JW, Kersaudy-Kerhoas M. Exosome isolation: a microfluidic road-map. Lab Chip. 2015;15(11):2388–2394. doi: 10.1039/C5LC00240K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jiang Y, Shi M, Liu Y, Wan S, Cui C, Zhang L, Tan W. Aptamer/AuNP biosensor for colorimetric profiling of exosomal proteins. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2017;56(39):11916–11920. doi: 10.1002/anie.201703807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao G, Li H, Guo Q, Zhou A, Wang X, Li P, Zhang S. Exosomal Sonic Hedgehog derived from cancer-associated fibroblasts promotes proliferation and migration of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2020;9(7):2500–2513. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Q, Len TY, Zhang SX, Zhao QH, Yang LH. Exosomes transferring long non-coding RNA FAL1 to regulate ovarian cancer metastasis through the PTEN/AKT signaling pathway. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24(21):10921. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202011_23560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Plebanek MP, Angeloni NL, Vinokour E, Li J, Henkin A, Martinez-Marin D, Filleur S, Bhowmick R, Henkin J, Miller SD, et al. Pre-metastatic cancer exosomes induce immune surveillance by patrolling monocytes at the metastatic niche. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1319. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01433-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee HY, Chen CK, Ho CM, Lee SS, Chang CY, Chen KJ, Jou YS. EIF3C-enhanced exosome secretion promotes angiogenesis and tumorigenesis of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2018;9(17):13193–13205. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.24149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qu L, Ding J, Chen C, Wu ZJ, Liu B, Gao Y, Chen W, Liu F, Sun W, Li XF, et al. Exosome-transmitted lncARSR promotes sunitinib resistance in renal cancer by acting as a competing endogenous RNA. Cancer Cell. 2016;29(5):653–668. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Robless EE, Howard JA, Casari I, Falasca M. Exosomal long non-coding RNAs in the diagnosis and oncogenesis of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett. 2021;501:55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2020.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sun W, Ren Y, Lu Z, Zhao X. The potential roles of exosomes in pancreatic cancer initiation and metastasis. Mol Cancer. 2020;19(1):135. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-01255-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moeng S, Son SW, Lee JS, Lee HY, Kim TH, Choi SY, Kuh HJ, Park JK. Extracellular vesicles (EVs) and pancreatic cancer: from the role of EVs to the interference with EV-mediated reciprocal communication. Biomedicines. 2020;8(8):267. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines8080267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fang Z, Xu J, Zhang B, Wang W, Liu J, Liang C, Hua J, Meng Q, Yu X, Shi S. The promising role of noncoding RNAs in cancer-associated fibroblasts: an overview of current status and future perspectives. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13(1):154. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00988-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li Z, Tao Y, Wang X, Jiang P, Li J, Peng M, Zhang X, Chen K, Liu H, Zhen P, et al. Tumor-secreted exosomal miR-222 promotes tumor progression via regulating P27 expression and re-localization in pancreatic cancer. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;51(2):610–629. doi: 10.1159/000495281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yin Z, Ma T, Huang B, Lin L, Zhou Y, Yan J, Zou Y, Chen S. Macrophage-derived exosomal microRNA-501-3p promotes progression of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma through the TGFBR3-mediated TGF-beta signaling pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38(1):310. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1313-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li M, Guo H, Wang Q, Chen K, Marko K, Tian X, Yang Y. Pancreatic stellate cells derived exosomal miR-5703 promotes pancreatic cancer by downregulating CMTM4 and activating PI3K/Akt pathway. Cancer Lett. 2020;490:20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sun H, Shi K, Qi K, Kong H, Zhang J, Dai S, Ye W, Deng T, He Q, Zhou M. Natural killer cell-derived exosomal miR-3607-3p inhibits pancreatic cancer progression by targeting IL-26. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2819. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 65.Shang S, Wang J, Chen S, Tian R, Zeng H, Wang L, Xia M, Zhu H, Zuo C. Exosomal miRNA-1231 derived from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells inhibits the activity of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Med. 2019;8(18):7728–7740. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wu DM, Wen X, Han XR, Wang S, Wang YJ, Shen M, Fan SH, Zhang ZF, Shan Q, Li MQ, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomal microRNA-126-3p inhibits pancreatic cancer development by targeting ADAM9. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2019;16:229–245. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 67.Hosein AN, Brekken RA, Maitra A. Pancreatic cancer stroma: an update on therapeutic targeting strategies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17(8):487–505. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-0300-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shang D, Xie C, Hu J, Tan J, Yuan Y, Liu Z, Yang Z. Pancreatic cancer cell-derived exosomal microRNA-27a promotes angiogenesis of human microvascular endothelial cells in pancreatic cancer via BTG2. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24(1):588–604. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Guo Z, Wang X, Yang Y, Chen W, Zhang K, Teng B, Huang C, Zhao Q, Qiu Z. Hypoxic tumor-derived exosomal long noncoding RNA UCA1 promotes angiogenesis via miR-96-5p/AMOTL2 in pancreatic cancer. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2020;22:179–195. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2020.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Steinbichler TB, Dudas J, Riechelmann H, Skvortsova II. The role of exosomes in cancer metastasis. Semin Cancer Biol. 2017;44:170–181. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kong F, Li L, Wang G, Deng X, Li Z, Kong X. VDR signaling inhibits cancer-associated-fibroblasts' release of exosomal miR-10a-5p and limits their supportive effects on pancreatic cancer cells. Gut. 2019;68(5):950–951. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ali S, Suresh R, Banerjee S, Bao B, Xu Z, Wilson J, Philip PA, Apte M, Sarkar FH. Contribution of microRNAs in understanding the pancreatic tumor microenvironment involving cancer associated stellate and fibroblast cells. Am J Cancer Res. 2015;5(3):1251–1264. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Takikawa T, Masamune A, Yoshida N, Hamada S, Kogure T, Shimosegawa T. exosomes derived from pancreatic stellate cells: microRNA signature and effects on pancreatic cancer cells. Pancreas. 2017;46(1):19–27. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yin Z, Zhou Y, Ma T, Chen S, Shi N, Zou Y, Hou B, Zhang C. Down-regulated lncRNA SBF2-AS1 in M2 macrophage-derived exosomes elevates miR-122-5p to restrict XIAP, thereby limiting pancreatic cancer development. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24(9):5028–5038. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.15125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Takahashi K, Ota Y, Kogure T, Suzuki Y, Iwamoto H, Yamakita K, Kitano Y, Fujii S, Haneda M, Patel T, et al. Circulating extracellular vesicle-encapsulated HULC is a potential biomarker for human pancreatic cancer. Cancer Sci. 2020;111(1):98–111. doi: 10.1111/cas.14232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang X, Li H, Lu X, Wen C, Huo Z, Shi M, Tang X, Chen H, Peng C, Fang Y, et al. Melittin-induced long non-coding RNA NONHSAT105177 inhibits proliferation and migration of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9(10):940. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0965-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li Z, Jiang P, Li J, Peng M, Zhao X, Zhang X, Chen K, Zhang Y, Liu H, Gan L, et al. Tumor-derived exosomal lnc-Sox2ot promotes EMT and stemness by acting as a ceRNA in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncogene. 2018;37(28):3822–3838. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li Z, Yanfang W, Li J, Jiang P, Peng T, Chen K, Zhao X, Zhang Y, Zhen P, Zhu J, et al. Tumor-released exosomal circular RNA PDE8A promotes invasive growth via the miR-338/MACC1/MET pathway in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett. 2018;432:237–250. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Li J, Li Z, Jiang P, Peng M, Zhang X, Chen K, Liu H, Bi H, Liu X, Li X. Circular RNA IARS (circ-IARS) secreted by pancreatic cancer cells and located within exosomes regulates endothelial monolayer permeability to promote tumor metastasis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37(1):177. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0822-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pastushenko I, Blanpain C. EMT transition states during tumor progression and metastasis. Trends Cell Biol. 2019;29(3):212–226. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dongre A, Weinberg RA. New insights into the mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and implications for cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20(2):69–84. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Diepenbruck M, Christofori G. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and metastasis: yes, no, maybe? Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2016;43:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Greening DW, Gopal SK, Mathias RA, Liu L, Sheng J, Zhu HJ, Simpson RJ. Emerging roles of exosomes during epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer progression. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2015;40:60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kim H, Lee S, Shin E, Seong KM, Jin YW, Youn H, Youn B. The emerging roles of exosomes as EMT regulators in cancer. Cells. 2020;9(4):861. doi: 10.3390/cells9040861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wu M, Tan X, Liu P, Yang Y, Huang Y, Liu X, Meng X, Yu B, Wu Y, Jin H. Role of exosomal microRNA-125b-5p in conferring the metastatic phenotype among pancreatic cancer cells with different potential of metastasis. Life Sci. 2020;255:117857. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang X, Luo G, Zhang K, Cao J, Huang C, Jiang T, Liu B, Su L, Qiu Z. Hypoxic tumor-derived exosomal miR-301a mediates M2 macrophage polarization via PTEN/PI3Kgamma to promote pancreatic cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 2018;78(16):4586–4598. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-3841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gehrmann U, Naslund TI, Hiltbrunner S, Larssen P, Gabrielsson S. Harnessing the exosome-induced immune response for cancer immunotherapy. Semin Cancer Biol. 2014;28:58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Robbins PD, Morelli AE. Regulation of immune responses by extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(3):195–208. doi: 10.1038/nri3622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sharma P, Diergaarde B, Ferrone S, Kirkwood JM, Whiteside TL. Melanoma cell-derived exosomes in plasma of melanoma patients suppress functions of immune effector cells. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):92. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-56542-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cox MJ, Lucien F, Sakemura R, Boysen JC, Kim Y, Horvei P, Manriquez Roman C, Hansen MJ, Tapper EE, Siegler EL, et al. Leukemic extracellular vesicles induce chimeric antigen receptor T cell dysfunction in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Mol Ther. 2021;29(4):1529–1540. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Czystowska-Kuzmicz M, Sosnowska A, Nowis D, Ramji K, Szajnik M, Chlebowska-Tuz J, Wolinska E, Gaj P, Grazul M, Pilch Z, et al. Small extracellular vesicles containing arginase-1 suppress T-cell responses and promote tumor growth in ovarian carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):3000. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10979-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ludwig S, Floros T, Theodoraki MN, Hong CS, Jackson EK, Lang S, Whiteside TL. Suppression of lymphocyte functions by plasma exosomes correlates with disease activity in patients with head and neck cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(16):4843–4854. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tucci M, Passarelli A, Mannavola F, Felici C, Stucci LS, Cives M, Silvestris F. Immune system evasion as hallmark of melanoma progression: the role of dendritic cells. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1148. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.01148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhou M, Chen J, Zhou L, Chen W, Ding G, Cao L. Pancreatic cancer derived exosomes regulate the expression of TLR4 in dendritic cells via miR-203. Cell Immunol. 2014;292(1–2):65–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ding G, Zhou L, Qian Y, Fu M, Chen J, Chen J, Xiang J, Wu Z, Jiang G, Cao L. Pancreatic cancer-derived exosomes transfer miRNAs to dendritic cells and inhibit RFXAP expression via miR-212-3p. Oncotarget. 2015;6(30):29877–29888. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Housman G, Byler S, Heerboth S, Lapinska K, Longacre M, Snyder N, Sarkar S. Drug resistance in cancer: an overview. Cancers (Basel) 2014;6(3):1769–1792. doi: 10.3390/cancers6031769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chen WX, Liu XM, Lv MM, Chen L, Zhao JH, Zhong SL, Ji MH, Hu Q, Luo Z, Wu JZ, et al. Exosomes from drug-resistant breast cancer cells transmit chemoresistance by a horizontal transfer of microRNAs. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e95240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hu Y, Yan C, Mu L, Huang K, Li X, Tao D, Wu Y, Qin J. Fibroblast-derived exosomes contribute to chemoresistance through priming cancer stem cells in colorectal cancer. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(5):e0125625. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yang Z, Zhao N, Cui J, Wu H, Xiong J, Peng T. Exosomes derived from cancer stem cells of gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer cells enhance drug resistance by delivering miR-210. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 2020;43(1):123–136. doi: 10.1007/s13402-019-00476-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fang Y, Zhou W, Rong Y, Kuang T, Xu X, Wu W, Wang D, Lou W. Exosomal miRNA-106b from cancer-associated fibroblast promotes gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic cancer. Exp Cell Res. 2019;383(1):111543. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2019.111543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Binenbaum Y, Fridman E, Yaari Z, Milman N, Schroeder A, Ben David G, Shlomi T, Gil Z. Transfer of miRNA in macrophage-derived exosomes induces drug resistance in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2018;78(18):5287–5299. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mikamori M, Yamada D, Eguchi H, Hasegawa S, Kishimoto T, Tomimaru Y, Asaoka T, Noda T, Wada H, Kawamoto K, et al. MicroRNA-155 controls exosome synthesis and promotes gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42339. doi: 10.1038/srep42339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Patel GK, Khan MA, Bhardwaj A, Srivastava SK, Zubair H, Patton MC, Singh S, Khushman M, Singh AP. Exosomes confer chemoresistance to pancreatic cancer cells by promoting ROS detoxification and miR-155-mediated suppression of key gemcitabine-metabolising enzyme, DCK. Br J Cancer. 2017;116(5):609–619. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Neoptolemos JP, Kleeff J, Michl P, Costello E, Greenhalf W, Palmer DH. Therapeutic developments in pancreatic cancer: current and future perspectives. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15(6):333–348. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jiang MJ, Chen YY, Dai JJ, Gu DN, Mei Z, Liu FR, Huang Q, Tian L. Dying tumor cell-derived exosomal miR-194-5p potentiates survival and repopulation of tumor repopulating cells upon radiotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer. 2020;19(1):68. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-01178-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chen YY, Jiang MJ, Tian L. Analysis of exosomal circRNAs upon irradiation in pancreatic cancer cell repopulation. BMC Med Genom. 2020;13(1):107. doi: 10.1186/s12920-020-00756-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Soreide K. Sweet predictions speak volumes for early detection of pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(2):265–268. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Pelzer U, Hilbig A, Sinn M, Stieler J, Bahra M, Dorken B, Riess H. Value of carbohydrate antigen 19–9 in predicting response and therapy control in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer undergoing first-line therapy. Front Oncol. 2013;3:155. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Humphris JL, Chang DK, Johns AL, Scarlett CJ, Pajic M, Jones MD, Colvin EK, Nagrial A, Chin VT, Chantrill LA, et al. The prognostic and predictive value of serum CA199 in pancreatic cancer. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(7):1713–1722. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ballehaninna UK, Chamberlain RS. The clinical utility of serum CA 19–9 in the diagnosis, prognosis and management of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: an evidence based appraisal. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2012;3(2):105–119. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2011.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kahroba H, Hejazi MS, Samadi N. Exosomes: from carcinogenesis and metastasis to diagnosis and treatment of gastric cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2019;76(9):1747–1758. doi: 10.1007/s00018-019-03035-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Fitts CA, Ji N, Li Y, Tan C. Exploiting exosomes in cancer liquid biopsies and drug delivery. Adv Healthc Mater. 2019;8(6):e1801268. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201801268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Thind A, Wilson C. Exosomal miRNAs as cancer biomarkers and therapeutic targets. J Extracell Vesicles. 2016;5:31292. doi: 10.3402/jev.v5.31292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Salehi M, Sharifi M. Exosomal miRNAs as novel cancer biomarkers: challenges and opportunities. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(9):6370–6380. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Yee NS, Zhang S, He HZ, Zheng SY. Extracellular vesicles as potential biomarkers for early detection and diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Biomedicines. 2020;8(12):581. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines8120581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wu L, Zhou WB, Zhou J, Wei Y, Wang HM, Liu XD, Chen XC, Wang W, Ye L, Yao LC, et al. Circulating exosomal microRNAs as novel potential detection biomarkers in pancreatic cancer. Oncol Lett. 2020;20(2):1432–1440. doi: 10.3892/ol.2020.11691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Pu X, Ding G, Wu M, Zhou S, Jia S, Cao L. Elevated expression of exosomal microRNA-21 as a potential biomarker for the early diagnosis of pancreatic cancer using a tethered cationic lipoplex nanoparticle biochip. Oncol Lett. 2020;19(3):2062–2070. doi: 10.3892/ol.2020.11302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]