Abstract

Background:

An expert panel convened by the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs and the Center for Evidence-Based Dentistry conducted a systematic review and formulated clinical recommendations for the urgent management of symptomatic irreversible pulpitis with or without symptomatic apical periodontitis, pulp necrosis and symptomatic apical periodontitis, or pulp necrosis and localized acute apical abscess using antibiotics, either alone or as adjuncts to definitive, conservative dental treatment (DCDT) in immunocompetent adults.

Types of Studies Reviewed:

The authors conducted a search of the literature in MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library, and CINAHL to retrieve evidence on benefits and harms associated with antibiotic use. Authors used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach to assess the certainty in the evidence, and the Evidence-to-Decisions Framework.

Results:

The panel formulated five clinical recommendations and two good practice statements, each specific to the target conditions, for settings where DCDT is and is not immediately available. With likely negligible benefits and potentially large harms, the panel recommended against using antibiotics in the majority of clinical scenarios, irrespective of DCDT availability. They recommended antibiotics in patients with systemic involvement (e.g., malaise, fever) due to the dental conditions, or when the risk of progression to systemic involvement is high.

Conclusion and Practical Implications:

Evidence suggests that antibiotics for the target conditions may provide negligible benefits and probably contributes to large harms. The expert panel only suggests antibiotics for target conditions when systemic involvement is present, and immediate DCDT should be prioritized in all cases.

Keywords: Antibiotics, symptomatic irreversible pulpitis, symptomatic apical periodontitis, pulp necrosis, localized acute apical abscess, Clinical practice guideline, antibiotic stewardship

INTRODUCTION

Dental pain and/or intra-oral swelling is not only a concern for dental providers but is also the most cited oral health-related reason for a patient contacting an emergency department (ED) or physician.1–3 These signs and symptoms are associated with pulpal and periapical conditions, which usually result from dental caries. Bacteria associated with caries can cause symptomatic irreversible pulpitis, an inflammation of the pulpal tissue. This condition may manifest as occasional sharp pain, usually stimulated by temperature change, and can worsen to spontaneous, constant, and dull or severe pain. Progressive pulp inflammation in the apical region (i.e. symptomatic apical periodontitis) may result in necrotic pulp (i.e. pulp necrosis and symptomatic apical periodontitis). The infection can continue to move into and through the alveolar bone to the soft tissues surrounding the jaw (i.e. localized acute apical abscess). Depending on location and patient status, this can further develop into systemic infection (Table 1).4, 5

Table 1.

Pulpal and periapical target conditions and their clinical signs and symptoms

| Target condition | Characteristics of clinical signs and symptoms |

|---|---|

| Symptomatic irreversible pulpitis | Spontaneous pain that may linger with thermal changes due to vital inflamed pulp that is incapable of healing |

| Symptomatic apical periodontitis | Pain with mastication and/or percussion or palpation, with or without evidence of radiographic periapical pathosis, and without swelling |

| Pulp necrosis and symptomatic apical periodontitis | Non-vital pulp, with pain with mastication and/or percussion or palpation, with or without evidence of radiographic periapical pathosis, and without swelling |

| Pulp necrosis and localized acute apical abscess | Non-vital pulp, with spontaneous pain with or without mastication and/or percussion or palpation, with formation of purulent material, localized swelling, and without evidence of fascial space or local lymph node involvement, fever, or malaise |

| Acute apical abscess with systemic involvement | Necrotic pulp with spontaneous pain, with or without mastication and/or percussion or palpation, with formation of purulent material, swelling, evidence of fascial space or local lymph node involvement, fever, and/or malaise |

Dentists and physicians often prescribe antibiotics to relieve dental pain and/or intra-oral swelling. General and specialty dentists are the third highest prescribers of antibiotics in all outpatient settings in the United States.6 In addition, current reports suggest that 30–85% of dental antibiotic prescriptions are “suboptimal or not indicated.”7–9 Due to major public health and cost related concerns, the appropriate use of antibiotics has become a critical issue in the healthcare agenda.

Although countries and clinical practice guideline development groups have produced recommendations on the use of systemic antibiotics to treat pulpal and periapical infections,10–14 there are currently no guidelines by the American Dental Association (ADA) for dentists in the United States. Many national and international agencies, including the United States federal government and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have joined forces with the ADA to help prevent a post-antibiotic era wherein antibiotics will no longer be effective in treating bacterial infections.15–19

The ADA Council on Scientific Affairs convened an expert panel comprised of academic and clinical experts specializing in dentistry, medicine, and pharmacology to develop this guideline and its accompanying systematic review.20 The ADA Center for Evidence-Based Dentistry (EBD) provided methodological support, drafted manuscripts, and led stakeholder engagement efforts.

Scope, purpose, target audience

The purpose of this guideline is to assist clinicians and patients with determining the appropriate use of systemic antibiotics for the urgent management of the following target conditions: symptomatic irreversible pulpitis (SIP) with or without symptomatic apical periodontitis (SAP), pulp necrosis and symptomatic apical periodontitis (PN-SAP), and pulp necrosis and localized acute apical abscess (PN-LAAA) with or without access to immediate, definitive, conservative (tooth preserving) dental treatment (DCDT) (i.e. pulpotomy, pulpectomy, nonsurgical root canal treatment, or incision and drainage). The scope of this guideline focuses on immunocompetent adult patients (18 years of age or older), with the target conditions, and without additional comorbidities. The management of adults with cellulitis and/or compromised immune systems (defined as those with the inability to appropriately respond to a bacterial challenge (e.g., patients undergoing chemotherapy)), and the management of adults undergoing tooth extraction are not within the scope of this guideline (Appendix Introduction). Though these recommendations are primarily intended for use by general dentists, they may also be used by specialty and public health dentists, dental educators, emergency and primary care physicians, infectious disease specialists, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, and policy makers. These recommendations might also be discussed during chairside conversations with patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of clinical recommendations for the urgent management of symptomatic irreversible pulpitis with or without symptomatic apical periodontitis, pulp necrosis and symptomatic apical periodontitis, and pulp necrosis and localized acute apical abscess.

| Setting | Clinical questions | Expert panel recommendations and good practice statements |

|---|---|---|

| Urgent situations in dental settings where pulpotomy, pulpectomy, non-surgical root canal treatment, or incision for drainage of abscess are not an immediate option (same visit). | 1. For immunocompetent* adults with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis† with or without symptomatic apical periodontitis,‡ should we recommend the use of oral systemic antibiotics compared with the non-use of oral systemic antibiotics to improve health outcomes? | Recommendation 1: The expert panel recommends dentists do not prescribe oral systemic antibiotics for immunocompetent* adults with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis† with or without symptomatic apical periodontitis‡ (Strong recommendation, low certainty in the evidence). Clinicians should refer§ patients for definitive, conservative dental treatment while providing interim monitoring.¶ |

| 2. For immunocompetent* adults with pulp necrosis and symptomatic apical periodontitis‡ or localized acute apical abscess,# should we recommend the use of oral systemic antibiotics compared with the non-use of oral systemic antibiotics to improve health outcomes? | Recommendation 2A: The expert panel suggests dentists do not prescribe oral systemic antibiotics for immunocompetent* adults with pulp necrosis and symptomatic apical periodontitis‡ (Conditional recommendation, very low certainty in the evidence). Clinicians should refer§ patients for definitive, conservative dental treatment while providing interim monitoring.¶ If definitive, conservative dental treatment is not feasible, a delayed prescription** for oral amoxicillin (500 milligrams, three times a day, 3–7d) or oral penicillin VK (500 milligrams, four times a day, 3–7d)††, ‡‡,§§,¶¶,## should be provided. | |

| Recommendation 2B: The expert panel suggests dentists prescribe oral amoxicillin (500 milligrams, three times a day, 3–7d) or oral penicillin VK (500 milligrams, four times a day, 3–7d)††,‡‡,§§,¶¶,## for immunocompetent* adults with pulp necrosis and localized acute apical abscess# (Conditional recommendation, very low certainty in the evidence). Clinicians should additionally provide urgent referral§ as definitive, conservative dental treatment should not be delayed.¶ | ||

| No corresponding clinical question | Good practice statement: The expert panel suggests dentists prescribe oral amoxicillin (500 milligrams, three times a day, 3–7d) or oral penicillin VK (500 milligrams, four times a day, 3–7d)††,‡‡,§§,¶¶,## for immunocompetent adults with pulp necrosis and acute apical abscess with systemic involvement.*** Clinicians should additionally provide urgent referral§ as definitive, conservative dental treatment should not be delayed.¶ If the clinical condition worsens or if there is concern for deeper space infection or immediate threat to life, refer patient for emergent evaluation.††† | |

| Urgent situations in dental settings and pulpotomy, pulpectomy, non-surgical root canal treatment, or incision for drainage of abscess are an immediate option (same visit). | 3. For immunocompetent* adults with pulp necrosis and symptomatic apical periodontitis‡ or localized acute apical abscess,# should we recommend the use of oral systemic antibiotics compared with the non-use of oral systemic antibiotics as adjuncts to definitive, conservative dental treatment‡‡‡ to improve health outcomes? | Recommendation 3: The expert panel recommends dentists do not prescribe oral systemic antibiotics as an adjunct to definitive, conservative dental treatment‡‡‡ for immunocompetent* adults with pulp necrosis and symptomatic apical periodontitis‡ or localized acute apical abscess# (Strong recommendation, very low certainty in the evidence). |

| 4. For immunocompetent* adults with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis† with or without symptomatic apical periodontitis,‡ should we recommend the use of oral systemic antibiotics compared with the non-use of oral systemic antibiotics as adjuncts to definitive, conservative dental treatment§§§ to improve health outcomes? | Recommendation 4: The expert panel suggests dentists do not prescribe oral systemic antibiotics as an adjunct to definitive, conservative dental treatment§§§ for immunocompetent* adults with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis† with or without symptomatic apical periodontitis‡ (Conditional recommendation, very low certainty in the evidence). | |

| No corresponding clinical question | Good practice statement: The expert panel suggests dentists perform urgent definitive, conservative dental treatment‡‡‡ in conjunction with prescribing oral amoxicillin (500 milligrams, three times a day, 3–7d) or oral penicillin VK (500 milligrams, four times a day, 3–7d)††,‡‡,§§,¶¶,## for immunocompetent adults with pulp necrosis and acute apical abscess with systemic involvement.*** If the clinical condition worsens or if there is concern for deeper space infection or immediate threat to life, refer for urgent evaluation.††† |

Immunocompetent is defined as the ability of the body to mount an appropriate immune response to an infection. Immunocompromised patients do not meet the criteria for this recommendation and they can include but are not limited to patients with HIV with an AIDS defining opportunistic illness, cancer, organ or stem cell transplants, and autoimmune conditions on immunosuppressive drugs (American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 2016).

Symptomatic irreversible pulpitis is characterized by spontaneous pain that may linger with thermal changes due to vital inflamed pulp that is incapable of healing (American Association for Endodontists 2016).

Symptomatic apical periodontitis is characterized by pain with mastication and/or percussion or palpation, with or without evidence of radiographic periapical pathosis, and without swelling (American Association for Endodontists 2016).

Clinicians including dentists, dental hygienists, and other members of the dental care team may refer patients to an endodontist, oral-maxillofacial surgeon, or general dentist who is trained to perform the definitive, conservative dental treatment. Definitive, conservative dental treatment refers to pulpotomy, pulpectomy, root canal debridement, non-surgical root canal treatment, or incision for drainage of abscess. Extractions are not within the scope of this guideline.

Patients should be instructed to call if their condition deteriorates (progression of disease to a more severe state) or if the referral to receive definitive, conservative dental treatment within 1–2 days is not possible. Evidence suggests that NSAIDS and acetaminophen (specifically 400–600 mg ibuprofen + 1000 mg acetaminophen) may be effective in managing dental pain (Moore 2018).

Localized acute apical abscess is characterized by spontaneous pain with or without mastication and/or percussion or palpation, with formation of purulent material, localized swelling, and without evidence of fascial space or local lymph node involvement, fever, or malaise (fatigue, reduced energy) (American Association for Endodontists 2016).

Dentists should communicate to the patient that if their symptoms worsen and they experience swelling or pus formation, the delayed prescription should be filled. Delayed prescribing is defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as a prescription that is “used for patients with conditions that usually resolve without treatment but who can benefit from antibiotics if the conditions do not improve… [Dentists] can apply delayed prescribing practices by giving the patient a postdated prescription and providing instructions to fill the prescription after a predetermined period or by instructing the patient to call or return to collect a prescription if symptoms worsen or do not improve” (Sanchez 2016).

Although the expert panel recommends both amoxicillin and penicillin as first-line treatments, amoxicillin is preferred over penicillin because it is more effective against various gram-negative anaerobes and its lower incidence of gastrointestinal side effects.

As an alternative for individuals with a history of a penicillin allergy, but without a history of anaphylaxis, angioedema, or hives with penicillin, ampicillin, or amoxicillin, the panel suggests dentists prescribe oral cephalexin (500 milligrams, four times a day, 3–7d). Of note, the anaerobic activity of cephalexin is not well described for some oral pathogens. Clinicians should have a low threshold to add metronidazole to cephalexin therapy in patients with a delayed response to antibiotics. As an alternative for individuals with a history of a penicillin allergy, and with a history of anaphylaxis, angioedema, or hives with penicillin, ampicillin, or amoxicillin, the panel suggests dentists prescribe oral azithromycin (loading dose of 500 milligrams on day 1, followed by 250 milligrams for an additional four days), or oral clindamycin (300 milligram,s four times a day, 3–7d) (Stein 2018). Bacterial resistance rates for azithromycin are higher than for other antibiotics, and clindamycin substantially increases the risk of C. difficile infection even after a single dose (Thornhill 2015). Due to concerns about antibiotic resistance, patients who receive azithromycin should be instructed to closely monitor their symptoms and call a dentist or primary care provider if their infection worsens while on therapy. Similarly, clindamycin has a U.S. Food and Drug Administration Black Box warning for Clostridium difficile infection, which can be fatal. Patients should be instructed to call their primary care provider if they develop fever, abdominal cramping, or ≥3 loose bowel movements per day (Leffler 2015). An antibiotic with a similar spectrum of activity to those recommended above can be continued if the antibiotic was initiated prior to patient presentation. As with any antibiotic use, the patient should be instructed on symptoms that may indicate lack of antibiotic efficacy and adverse drug events.

Clinicians should reevaluate patient within 3 days (e.g., in-person visit or phone call). Dentists should instruct patients to discontinue antibiotics 24 hours after patient’s symptoms resolve, irrespective of reevaluation after 3 days.

In cases where patients without a penicillin allergy fail to respond to first-line treatment (i.e. patient shows no improvement in symptoms and/or the condition progresses to a more severe state) with oral amoxicillin or oral penicillin VK, the panel suggests that dentists should broaden antibiotic therapy to either complement first-line treatment with oral metronidazole (500 milligrams, three times a day, 7d), or discontinue first-line treatment and prescribe oral amoxicillin/clavulanate (500/125 milligrams, three times a day, 7d). Clinicians should reevaluate patient within 3 days (e.g., in-person visit or phone call). Dentists should instruct patients to discontinue antibiotics 24 hours after patient’s symptoms resolve, irrespective of reevaluation after 3 days.

In cases where patients with a history of a penicillin allergy and with or without a history of anaphylaxis, angioedema, or hives with penicillin, ampicillin, or amoxicillin fail to respond to first-line treatment (i.e. patient shows no improvement in symptoms and/or the condition progresses to a more severe state) with oral cephalexin, oral azithromycin, or oral clindamycin, the panel suggests that dentists should broaden antibiotic therapy to complement first-line treatment with oral metronidazole (500 milligrams, three times a day, 7d). Clinicians should reevaluate patient within 3 days (e.g., in-person visit or phone call). Dentists should instruct patients to discontinue antibiotics 24 hours after patient’s symptoms resolve, irrespective of reevaluation after 3 days.

Acute apical abscess with systemic involvement is characterized by necrotic pulp with spontaneous pain, with or without mastication and/or percussion or palpation, with formation of purulent material, swelling, evidence of fascial space or local lymph node involvement, fever, and/or malaise.

Urgent evaluation will most likely be conducted in an urgent care setting or an emergency room.

Definitive, conservative dental treatment refers to non-surgical root canal treatment or incision for drainage of abscess. Only clinicians who are authorized or trained to perform the specified treatments should do so.

Definitive, conservative dental treatment refers to pulpotomy, pulpectomy, or non-surgical root canal treatment. Only clinicians who are authorized or trained to perform the specified treatments should do so.

METHODS

The guideline and development of this manuscript was conducted according to the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation Reporting II Checklist21 and Guidelines International Network-McMaster Guideline Development Checklist22. The expert panel and methodologists met in person twice; the first meeting commenced by reviewing panelists’ conflicts of interests, followed by defining the scope, purpose, target audience, and clinical questions.23 The panel defined desirable and undesirable outcomes for decision making. After the first meeting, methodologists at the ADA Center for Evidence-Based Dentistry (L.P., M.P.T., O.U., A.C.L.) worked with an informationist (K.O.) to develop a systematic review of the evidence,20 which included updating two pre-existing Cochrane systematic reviews.24, 25 The second in person meeting was facilitated by a methodologist at the ADA Center for Evidence-Based Dentistry (M.P.T.) using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Evidence-to-Decision framework.26–30 During this meeting, the expert panel discussed the evidence to formulate recommendations and good practice statements (GPS), all decisions were developed through consensus, and the panel only voted if consensus was difficult to achieve. Recommendations formulated using GRADE can be strong or weak/conditional with varying implications for different users (Table 3). Additional efforts to inform this guideline include a robust stakeholder and public engagement process and a plan for updating the guideline whenever the direction and strength of recommendations may be affected by newly published evidence (or within five years). Additional details about the methodology we used to develop this clinical practice guideline are available in the Appendix (available online at the end of this article) and the associated systematic review.20

Table 3.

Definitions of the certainty in the evidence and strength of recommendations, and implications for patients, clinicians, and policy makers*

| Definition of certainty (quality) in the evidence | ||

|---|---|---|

| Category | Definition | |

| High | We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. | |

| Moderate | We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. | |

| Low | Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. | |

| Very low | We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |

| Definition of strong and conditional recommendations and implications for users | ||

| Implications | Strong recommendations | Conditional recommendations |

| For patients | Most individuals in this situation would want the recommended course of action and only a small proportion would not. Formal decision aids are not likely to be needed to help individuals make decisions consistent with their values and preferences. | The majority of individuals in this situation would want the suggested course of action, but many would not. |

| For clinicians | Most individuals should receive the intervention. Adherence to this recommendation according to the guideline could be used as a quality criterion or performance indicator. | Recognize that different choices will be appropriate for individual patients and that you must help each patient arrive at a management decision consistent with his or her values and preferences. Decision aids may be useful helping individuals making decisions consistent with their values and preferences. |

| For policy makers | The recommendation can be adapted as policy in most situations. | Policymaking will require substantial debate and involvement of various stakeholders. |

Sources: Andrews 2013, Guyatt 2008

Andrews J, Guyatt G, Oxman AD, et al. GRADE guidelines: 14. Going from evidence to recommendations—the significance and presentation of recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(7):719–725.

Andrews JC, Schunemann HJ, Oxman AD, et al. GRADE guidelines: going from evidence to recommendation—determinants of a rec ommendation’s direction and strength. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(7):726–735.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336(7650):924–6.

RESULTS

Recommendations and good practice statements (GPS)

Recommendations are informed by a comprehensive search for the best available evidence and a formal process for assessing the certainty of the evidence. In contrast, GPSs are appropriate when there is an excess of indirect evidence suggesting that its implementation will result in large and unequivocal net positive or negative consequences. Recommendations are associated with a certainty of the evidence in contrast to GPSs (Table 2).31

How to use these recommendations and good practice statements

The expert panel graded the strength of recommendations (i.e. strong or conditional) to provide clinicians’, patients, and policy makers with orientation as to how to proceed in the face of the recommendation statement (Table 3). These recommendations and GPSs aim to help clinicians, policy makers, and patients make decisions about antibiotic use for immunocompetent adults (most typical patient) presenting with the target conditions. Clinicians should use informed clinical judgement32 to identify the appropriate course of action in situations that deviate from these recommendations and GPSs.

Recommendations

Recommendations in settings where definitive, conservative dental treatment is not immediately available

Question 1. For immunocompetent adults with SIP with or without SAP, should we recommend the use of oral systemic antibiotics compared with the non-use of oral systemic antibiotics to improve health outcomes (Appendix Methods)?

Desirable and undesirable effects from randomized controlled trials

For this comparison, the panel judged anticipated desirable effects as potentially negligible. Evidence suggests that 24 hours after starting antibiotics, pain intensity may increase slightly, but after seven days, it may reduce slightly (low certainty). In absolute terms, over a range of different time points up to seven days follow-up, out of 1,000 people taking antibiotics, anywhere from 49 fewer to 100 more people may experience pain (low certainty). Additionally, those taking antibiotics may also have half of an ibuprofen tablet less and two more rescue analgesic tablets than those who did not take antibiotics over seven days (low certainty) (eTable 1).20, 33 We identified no randomized controlled trials meeting our selection criteria that reported undesirable effects.

Undesirable effects from observational studies

From observational studies, the panel identified a large burden of anticipated undesirable effects directly or indirectly associated with antibiotic prescriptions including mortality due to antibiotic-resistant infections (23,000 deaths annually in the United States, low certainty), community-associated Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) (6,400 out of 10,000 people with community-associated CDI were exposed to antibiotics, moderate certainty), and mortality due to community-associated CDI (80 out of 10,000 people with community-associated CDI died and were exposed to antibiotics, moderate certainty), anaphylaxis due to antibiotics (46 and 6 out of 10,000 hospitalizations were due to anaphylaxis associated with the use of a penicillin and cephalosporin drug classes, respectively), amongst others (eTable 2, eTable 3).34–40 The panel is moderately certain that most estimates for critical harm outcomes represent a large burden, with a high chance for an underestimation. No direct evidence informed the impact of dental antibiotic prescriptions in the outcomes presented above. The panel calculated an adjusted estimate to illustrate the burden of antibiotics prescribed by dentists, and rated the certainty of these estimates down due to serious issues of indirectness41 (eTable 2, etable 3).

Values and preferences

Though patients’ values and preferences (PVP) will likely vary due to access to care issues, the panel considered values and preferences a crucial factor for decision making, in part, due to evidence informing beneficial outcomes being of low certainty. Unfortunately, no studies on values and preferences related to the clinical questions were found, and we used studies on antibiotic use for other (medical) conditions to inform these factors. For complete details on PVP, see Appendix Results.

Acceptability

From the panel’s perspective, key stakeholders will likely accept a recommendation against the use of antibiotics in most situations for the target conditions. Clinicians and patients may find a recommendation for antibiotics more acceptable in settings and situations where access to dental care is an issue, and the possibility of patients having a high expectation for receiving an antibiotic.

Feasibility

The panel agreed that not prescribing antibiotics for these target conditions in the absence of immediate DCDT is feasible if DCDT can be performed shortly (a few days) after the initial visit.

Recommendation 1

The expert panel recommends dentists do not prescribe oral systemic antibiotics for immunocompetent adults with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis with or without symptomatic apical periodontitis (Strong recommendation, low certainty of the evidence). Clinicians should refer patients for definitive, conservative dental treatment while providing interim monitoring (Table 2).

Remarks

Antibiotics may result in little to no difference in beneficial outcomes (low certainty), while likely resulting in a potentially large increase in harm outcomes (moderate certainty), warranting a strong recommendation against their use (2nd paradigmatic situation from GRADE guidance27).

From a physiopathological perspective, patient populations with SAP with or without SAP do not require antibiotics, given that the inflamed pulpal tissue associated with this condition is not due to an infection.

Providers, especially in EDs, other healthcare settings, or rural settings, should ask patients if they have access to dental care. If not, clinicians and patients may not find this recommendation acceptable or feasible for implementation given that patients may have high expectations for receiving an antibiotic.

Question 2. For immunocompetent adults with PN-SAP or PN-LAAA, should we recommend the use of oral systemic antibiotics compared with the non-use of oral systemic antibiotics to improve health outcomes (Appendix Methods)?

Desirable and undesirable effects from randomized controlled trials

We did not identify any eligible studies to inform this comparison for patients with PN-SAP or PN-LAAA. The panel decided to inform this recommendation with the same body of evidence summarized for question 1, and rated down the certainty of the evidence for beneficial outcomes from low to very low due to serious issues of indirectness due to differing patient populations (eTable 1).

Undesirable effects from observational studies

The panel used the same body of evidence informing harm outcomes (moderate certainty) for question 1 (eTable 2, eTable 3) to inform these factors in question 2.

Values and preferences

The same evidence on patients’ values and preferences described for question 1, informed this recommendation (link to Question 1 PVP factor). Additionally, the panel identified patients in this comparison to be at higher risk for systemic involvement because they have necrotic pulp (indicating an infectious process) and because they may not have immediate access to DCDT (link to acceptability section under question 1). Finally, regarding delayed prescribing (i.e. “a prescription that is used for patients with conditions that usually resolve without treatment but who can benefit from antibiotics if the conditions do not improve”),42 a Cochrane review reported that there were no significant differences in patient satisfaction when comparing delayed to immediate antibiotic prescriptions (91% vs. 86% satisfaction, moderate certainty).43

Acceptability

According to the panel, since patients with necrotic pulp are at a higher risk for disease progression with systemic involvement, and DCDT is not an immediate option in this question, and/or patients may lack access to care, clinicians may be less inclined to send patients home without antibiotics as compared to patients with SIP with or without SAP (who may be comparatively at lower risk for disease progression with systemic involvement).

Feasibility

The panel agreed that not providing antibiotics for these patients when DCDT is not immediately available is feasible, if DCDT can be performed shortly (a day or two) after initial visit.

When formulating recommendations, the panel was more concerned about the risk of disease progression with systemic involvement for patients with PN-LAAA compared to those with PN-SAP, and decided to provide separate guidance for each population.

Recommendation 2a

The expert panel suggests dentists do not prescribe oral systemic antibiotics for immunocompetent adults with pulp necrosis and symptomatic apical periodontitis (Conditional recommendation, very low certainty of the evidence). Clinicians should refer patients for definitive, conservative dental treatment while providing interim monitoring. If definitive, conservative dental treatment is not feasible, a delayed prescription for oral amoxicillin (500 milligrams, three times a day, 3–7d) or oral penicillin VK (500 milligrams, four times a day, 3–7d) should be provided (Table 2).

Remarks

For patients with PN-SAP, the panel suggests the use of a delayed antibiotic prescription for use if patients’ symptoms worsen and/or DCDT has yet to be performed. Clinicians should provide the prescription and instruct patients to fill it 24–48 hours post-initial visit.

Recommendation 2b

The expert panel suggests dentists prescribe oral amoxicillin (500 milligrams, three times a day, 3–7d) or oral penicillin VK (500 milligrams, four times a day, 3–7d) for immunocompetent adults with pulp necrosis and localized acute apical abscess (Conditional recommendation, very low certainty). Clinicians should additionally provide urgent referral as definitive, conservative dental treatment should not be delayed (Table 2).

Remarks

Though the evidence on antibiotics suggests both potential negligible benefits and likely substantial harms, there is an increased risk of disease progression to systemic involvement without immediate access to DCDT when compared to patients with PN-SAP. The panel thus judged that prescribing antibiotics in the absence of immediate DCDT may be appropriate for patients with PN-LAAA to reduce the potential risk for patient’s developing systemic involvement.

Remarks applicable to both recommendations 2a and 2b

Indirect evidence suggests that antibiotics may have little to no effect in beneficial outcomes (very low certainty), while likely resulting in a large increase in harm outcomes (moderate certainty), warranting a conditional recommendation against antibiotic use.

Providers, especially in EDs, other healthcare settings, or rural settings, should ask patients if they have access to dental care. If not, clinicians and patients may find that an immediate antibiotic prescription is the best course of action for patients with PN-SAP in addition to those with PN-LAAA.

Diagnostic tests readily available to dentists (e.g., pulp vitality tests) are usually unavailable in medical settings. Physicians should consider evaluating patients based on their signs and symptoms (Table 1).

Resources for discussing delayed prescribing are available online.44

Recommendations in settings where definitive, conservative dental treatment is immediately available

Question 3. For immunocompetent adults with PN-SAP or PN-LAAA, should we recommend the use of oral systemic antibiotics compared with the non-use of oral systemic antibiotics as adjuncts to DCDT to improve health outcomes (Appendix Methods)?

Desirable and undesirable effects from randomized controlled trials

The panel judged that the anticipated desirable effects of antibiotics as adjuncts to DCDT for patients with PN-SAP or PN-LAAA to be negligible. During the first 72 hours, the evidence suggests that pain intensity may be slightly higher in patients taking antibiotics, compared to patients not taking antibiotics (very low certainty). Up to seven days, antibiotics might result in a slight reduction in pain intensity (low certainty). The results over a range of different time points, up to seven days of follow-up, suggests that out of 1,000 people taking antibiotics, anywhere from 88 fewer people to 128 more people may experience pain (very low to low certainty). Additionally, the evidence on the effect of antibiotics on intra-oral swelling may suggest both an slight increase and reduction in the outcome over seven days. Out of 1,000 patients taking antibiotics, anywhere from 0 to 175 more people may experience intra-oral swelling (very low to low certainty). Additionally, those taking antibiotics may take two more ibuprofen tablets, and about a half tablet less of rescue analgesic than those who did not take antibiotics over seven days (low certainty)(eTable 4). The panel judged that the anticipated undesirable effects of antibiotics as adjuncts to DCDT for patients with PN-SAP or PN-LAAA may be negligible. When taking antibiotics, adverse events such as endodontic flare up and diarrhea may infrequently occur (all very low certainty) (eTable 4).20, 45, 46

Undesirable effects from observational studies

The panel applied the same interpretation of the anticipated undesirable effects in settings where DCDT is not immediately available, to this clinical setting (link to undesirable effects section) (eTable 2, eTable 3).

Values and preferences

The same evidence for patients’ values and preferences previously described informed this recommendation (link to Question 1 PVP factor; Appendix Results). Additionally, the panel acknowledged that for patients with PN-SAP or PN-LAAA, procedures for DCDT may take an hour or more to complete. They hypothesized that implementing these procedures may reduce patients’ expectations for receiving antibiotics.

Acceptability

The panel agreed that not prescribing antibiotics as adjuncts to DCDT for this population will probably be acceptable to key stakeholders. They hypothesized that stakeholders would be willing to accept a recommendation for implementing DCDT alone, given the biological mechanism underlying these conditions (oral antibiotics not reaching to the affected tooth because the lack of vascular supply, or the antibiotics prescribed empirically may not be effective for the dominant microflora in the infection), and balance between benefits and harms favoring the nonuse of antibiotics as adjuncts.

Feasibility

The panel judged that not using antibiotics as adjuncts to DCDT would be feasible.

Recommendation 3

The expert panel recommends dentists do not prescribe oral systemic antibiotics as an adjunct to definitive, conservative dental treatment for immunocompetent adults with pulp necrosis and symptomatic apical periodontitis or localized acute apical abscess (Strong recommendation, very low certainty) (Table 2).

Remarks

Antibiotics may result in little to no difference in beneficial outcomes (very low certainty), while likely results in a potentially large increase in harm outcomes (moderate certainty), warranting a strong recommendation against their use (2nd paradigmatic situation from GRADE guidance27).

Question 4: For immunocompetent adults with SIP with or without SAP, should we recommend the use of oral systemic antibiotics compared with the non-use of oral systemic antibiotics as adjuncts to DCDT to improve health outcomes (Appendix Methods)?

Desirable and undesirable effects from randomized controlled trials

We did not identify any studies specific to patients with SIP with or without SAP who have immediate access to DCDT. The panel decided to use the same body of evidence (eTable 4) used for Question 3 to inform this recommendation. The panel rated down the certainty of the evidence due to serious issues of indirectness due to differing patient populations, resulting in very low certainty.

Undesirable effects from observational studies

The panel used the same body of evidence summarized above (eTable 2, eTable 3) to inform the undesirable effects of antibiotics as adjuncts to DCDT.

Values and preferences

The panel used the same evidence on patients’ values and preferences previously described (link to Question 1 PVP factor; Appendix Results) to inform this factor. One additional consideration specific to this patient population is that removing the pulp tissue by means of DCDT may alleviate symptoms, and the panel hypothesized that these procedures may reduce patients’ expectations for receiving antibiotics.

Acceptability

The panel agreed that not prescribing antibiotics as adjuncts to DCDT will be highly acceptable to key stakeholders, since these patients have vital pulp and the risk of disease progression with systemic involvement is low.

Feasibility

The panel does not anticipate feasibility issues regarding implementing a recommendation against using antibiotics as adjunct to DCDT.

Recommendation 4

The expert panel suggests dentists do not prescribe oral systemic antibiotics as an adjunct to definitive, conservative dental treatment for immunocompetent adults with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis with or without symptomatic apical periodontitis (Conditional recommendation, very low certainty) (Table 2).

Remarks

Indirect evidence suggests that antibiotics may have little to no effect in beneficial outcomes (very low certainty), while likely results in a potentially large increase in harm outcomes (moderate certainty), warranting a conditional recommendation against their use.

From a physiopathological perspective, patient populations with SIP with or without SAP, especially those with the option of DCDT, do not require antibiotics, given that the inflamed pulpal tissue associated with this condition is not due to an infection.

Patients with pulp necrosis and acute apical abscess with systemic involvement

The panel provided GPSs for the use of antibiotics in patients with systemic involvement (fever, malaise, etc.) given that the role of antibiotics, irrespective of whether they are provided alone or as adjuncts to DCDT has been largely studied, and the balance between benefits and harms when systemic involvement is present is well established.

For adults with PN-AAA with systemic involvement, when considering the use of antibiotics alone or as adjuncts to DCDT, the panel formulated two GPS.

Good practice statements

The expert panel suggests dentists prescribe oral amoxicillin (500 milligrams, three times a day, 3–7d) or oral penicillin VK (500 milligrams, four times a day, 3–7d) for immunocompetent adults with pulp necrosis and acute apical abscess with systemic involvement. Clinicians should additionally provide urgent referral as definitive, conservative dental treatment should not be delayed. If the clinical condition worsens or if there is concern for deeper space infection or immediate threat to life, refer patient for urgent evaluation (Table 2).

The expert panel suggests dentists perform urgent definitive, conservative dental treatment in conjunction with prescribing oral amoxicillin (500 milligrams, three times a day, 3–7d) or oral penicillin VK (500 milligrams, four times a day, 3–7d) for immunocompetent adults with pulp necrosis and acute apical abscess with systemic involvement. If the clinical condition worsens or if there is concern for deeper space infection or immediate threat to life, refer for urgent evaluation (Table 2).

Summary of the rationale for the type of antibiotic and regimen

To inform the current status of antibiotic prescribing behaviors of dentists, including antibiotic types, doses, and durations, we used a 2018 scoping review.47 We also included input from stakeholders and expert panelists, and data on antibiotic sensitivity48–52 to determine the most appropriate course of action when first-line treatment fails, guidance to avoid recommending for antibiotics prone to cause severe drug-drug interactions, and guidance to balance the potential efficacy of a selected antibiotic with its potential serious adverse events.

General Remarks:

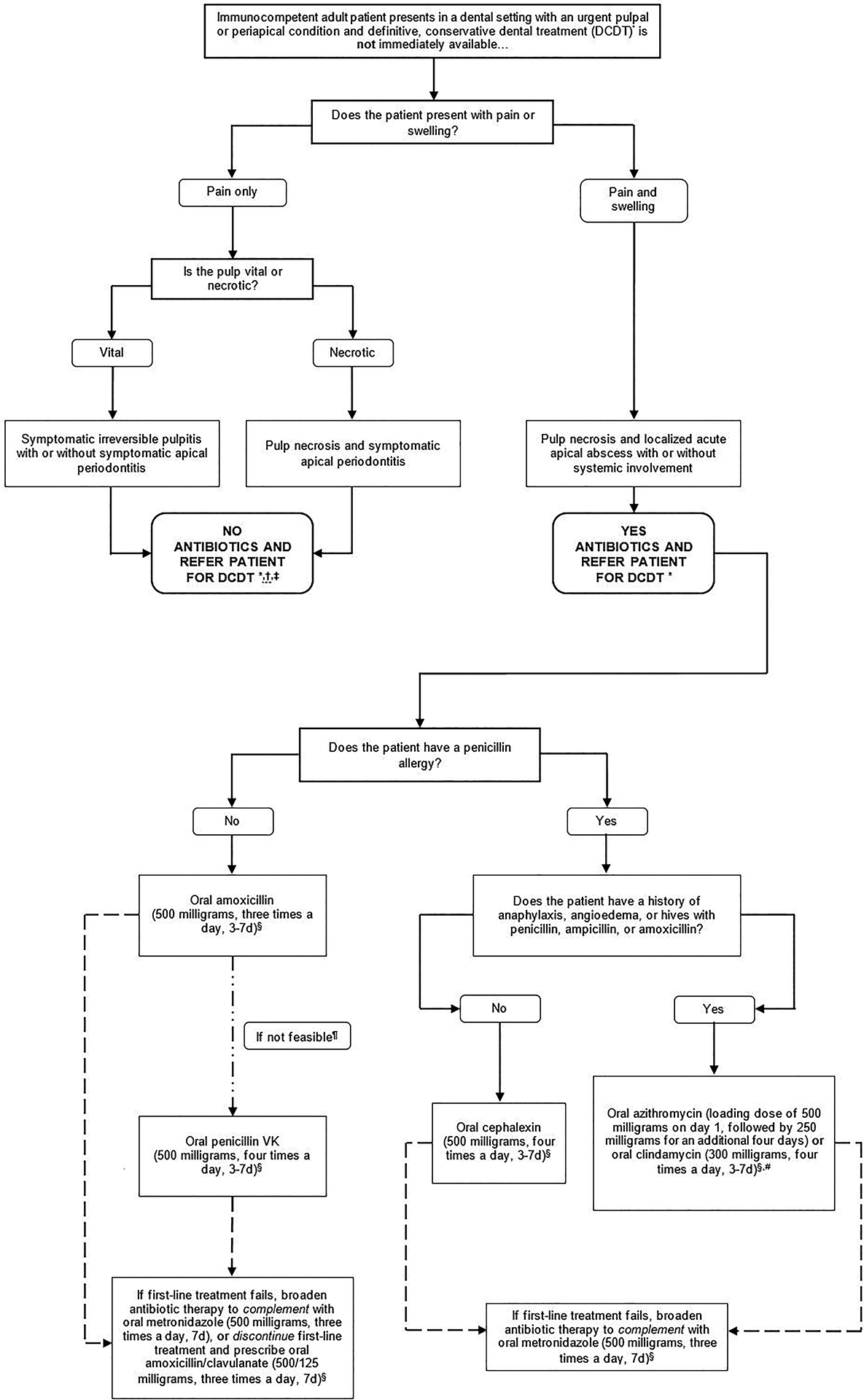

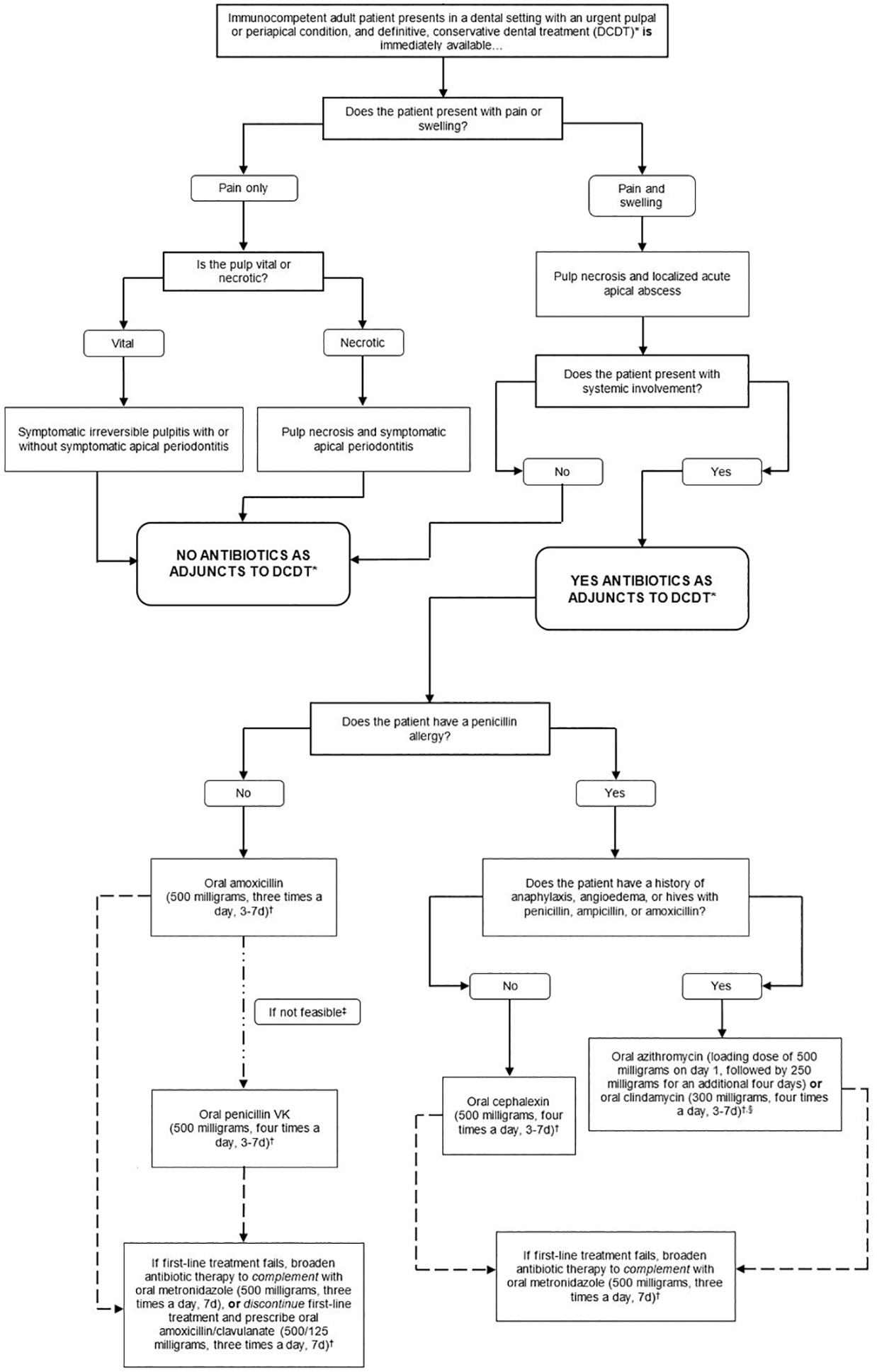

To facilitate the implementation of these recommendations and GPSs in practice, they were integrated in an algorithm (Figure 1, Figure 2).

In the case of a reported penicillin allergy, we have detailed non-penicillin drug class antibiotics for this patient population in Table 2.

Although approximately 10% of the population self-reports a penicillin allergy, less than 1% of the entire population is truly allergic.53, 54 Clinicians should proceed with non-penicillin drug class antibiotics until further confirmation of a true penicillin allergy. The panel suggests prescribing oral cephalexin, oral azithromycin, or oral clindamycin.

Some antibiotics may be less effective, or carry a greater risk for harming patients through allergic reactions (penicillin) or CDI (clindamycin).55, 56 Therefore, the list of antibiotics presented in this guideline is ordered balancing desirable and undesirable consequences of the use of each antibiotic.57

The prevention of CDI should be a community priority in addition to a hospital priority.37 According to a United Kingdom based study, the incidence of CDI can be reduced through the appropriate use of antibiotics.58

The panel acknowledges that other antibiotics have a reasonable spectrum of activity for the treatment of oral infections, such as moxifloxacin; however, there are U.S. Food and Drug Administration Black Box warnings (indicating a serious safety hazard) for this antibiotic.59

For cases that do not respond promptly to antibiotics, clinicians may consider either complementing first-line treatment with oral metronidazole, or discontinue first-line treatment and prescribe oral amoxicillin/clavulanate, to enhance the efficacy against Gram negative anaerobic organisms.

An antibiotic with a similar spectrum of activity of those recommended in Table 2 can be continued if the antibiotic was initiated prior to patient presentation. As with any antibiotic use, the patient should be instructed on symptoms that may indicate lack of antibiotic efficacy and adverse drug events.

- There is currently little to no evidence supporting the common belief that a shortened course of antibiotics contributes to antimicrobial resistance.57, 60

- Clinicians should reevaluate or follow-up with their patient after three days to assess if there is resolution of systemic signs and symptoms.

- If the patient’s signs and symptoms begin to resolve, clinicians should instruct the patient to discontinue antibiotics 24 hours after complete resolution, irrespective of reevaluation after 3 days.

Prescription medications, including antibiotics, should not be saved for later use nor shared with others. The panel emphasizes the importance of patients discarding antibiotics safely at local disposal centers.61

Estimates for pain outcomes reported in this review may be influenced by the use of analgesics in both intervention and control groups; therefore, when considering the effect of antibiotics on pain experience and intensity, authors interpreted any improvement in pain as additional pain relief attributable to antibiotics.

- Providers often prescribe antibiotics even when they are not appropriate due to the patient being in severe pain and expecting antibiotics to relieve this pain. Currently, the best available evidence for the management of acute pain can be found in an overview of five systematic reviews.62

- The evidence suggests that NSAIDS (specifically 400–600 mg ibuprofen + 1000 mg acetaminophen) could be effective and less harmful than any opioid containing medication or medication combination for the temporary relief of dental pain.62

Figure 1.

Clinical pathway for the treatment of immunocompetent adult patients presenting in a dental setting with a pulpal or periapical condition, where definitive conservative, dental treatment is not immediately available

Footnotes.

* Definitive conservative dental treatment refers to pulpotomy pulpectomy, non-surgical root canal treatment, or incision for drainage of abscess. Only clinicians who are authorized or trained to perform the specified treatments should do so.

† Adult patients with pulp necrosis and symptomatic apical periodontitis should be instructed to call if their condition deteriorates (progression of disease to a more severe state) or if the reterral to receive definitive conservative dental treatment within 1–2 days is not possible

‡ For adult patients with pulp necrosis and symptomatic apical periodontitis, a delayed prescription should be provided if definitive, conservative dental treatment is not immediately available. Dentists should communicate to the patient that if their symptoms worsen and they experience swelling or formulation of purulent material. the delayed prescription should be filled A delayed prescription is defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as a prescription that is used for patients with conditions that usually resolve without treatment but who can benefit from antibiotics if the conditions do not improve (Sanchez. 2016).

§ Clinicians should reevaluate patient within 3 days (e.g., in-person visit or phone call) Dentists should instruct patients to discontinue antibiotics 24 hours after patient’s symptoms resolve, irrespective of reevaluation after three days.

¶ Although the expert panel recommends both amoxicillin and penicillin as first-line treatments., amoxicillin is preferred over penicillin because it is more effective against various gram-negative anaerobes and its lower incidence of gastrointestinal side effects.

* Bacterial resistance rates tor azithromycin are higher than for other antibiotics, and clindamycin substantially increases the risk of Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) even after a single dose (Thornhill, 2015) Due to concerns about antibiotic resistance, patients who receive azithromycin should be instructed to closely monitor their symptoms and call a dentist or primary care provider if their infection worsens while on therapy Similarly, clindamycin has a U.S. Food and Drug Administration Black Box warning for CDI which can be fatal Patients should be instructed to call their primary care provider if they develop fever abdominal cramping, or ≥3 loose bowel movements per day (Leffler 2015) If the patient is currently taking an antibiotic within the same spectrum as the one indicated additional antibiotics do not need to be prescribed If the patient is currently taking an antibiotic outside of the spectrum as the one indicated, the intended antibiotic can still be prescribed, considering potential contraindications. An antibiotic with a similar spectrum of activity to those recommended can be continued if the antibiotic was initiated prior to patient presentation. As with any antibiotic use, the patient should be instructed on symptoms that may indicate lack of antibiotic efficacy and adverse drug events.

Figure 2.

Clinical pathway for the treatment of immunocompetent adult patients presenting in a dental setting with a pulpal or periapical condition where treatment is immediately available

Footnotes

* Definitive, conservative dental treatment refers to pulpotomy, pulpectomy, non-surgical root canal treatment, or incision for drainage of abscess. Only clinicians who are authorized or trained to perform the specified treatments should do so.

† Clinicians should reevaluate patient within 3 days (e.g., in-person visit or phone call). Dentists should instruct patients to discontinue antibiotics 24 hours after patient’s symptoms resolve, irrespective of reevaluation after three days.

‡ Although the expert panel recommends both amoxicillin and penicillin as first-line treatments, amoxicillin is preferred over penicillin because it is more efficacious against various gram-negative anaerobes and its lower incidence of gastrointestinal side effects.

§ Bacterial resistance rates for azithromycin are higher than for other antibiotics, and clindamycin substantially increases the risk of Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) even after a single dose (Thornhill. 2015). Due to concerns about antibiotic resistance, patients who receive azithromycin should be instructed to closely monitor their symptoms and call a dentist or primary care provider if their infection worsens while on therapy. Similarly, clindamycin has a U.S. Food and Drug Administration Black Box warning for CDI, which can be fatal. Patients should be instructed to call their primary care provider if they develop fever, abdominal cramping, or ≥3 loose bowel movements per day (Leffler, 2015). If the patient is currently taking an antibiotic within the same spectrum as the one indicated, additional antibiotics do not need to be prescribed. If the patient is currently taking an antibiotic outside of the spectrum as the one indicated, the intended antibiotic can still be prescribed, considering potential contraindications. An antibiotic with a similar spectrum of activity to those recommended can be continued if the antibiotic was initiated prior to patient presentation. As with any antibiotic use, the patient should be instructed on symptoms that may indicate lack of antibiotic efficacy and adverse drug events.

Discussion

Recent studies suggest that clinicians often prescribe antibiotics for patients with dental pain and/or intra-oral swelling to reduce the uncertainty associated with the “watch and wait” model, barriers in the health system, gaps in knowledge or disagreement with existing guidelines, diagnostic/prognostic uncertainties, patient expectations, or access to care issues.63–67 However, a shift in the paradigm of antibiotic prescribing in dentistry is necessary; the profession is encouraged to move from a “just in case” approach of antibiotic prescribing to a “when absolutely needed” approach.17

If there are no signs or symptoms of systemic involvement and if DCDT is immediately available, evidence suggests antibiotics may not provide substantial, additional improvement in pain intensity and experience, and probably cause large harms or undesirable effects (e.g., serious adverse events, antibiotic resistance, CDI, high costs, etc.). In contrast, if systemic involvement such as fever and malaise are present, good practice indicates that antibiotics should be prescribed in conjunction with DCDT or referral for DCDT. Ultimately, for the management of pain, other strategies, such as the use of NSAIDS and acetaminophen (400–600 mg ibuprofen + 1000 mg acetaminophen), should be considered instead.62

Patients with the target dental conditions usually refer to pain as their chief complaint. Even though there is no physiopathological rationale for the use of antibiotics for the management of inflammatory conditions and even the management of pain for patients with a dental infection, patients and clinicians would still be interested in learning the extent to which antibiotics would play any role in offering pain relief. To make sure that these recommendations are informed by a complete set of patient-important outcomes, the panel decided to include pain as one of the potential desirable effects of antibiotics.

Comparison to other guidelines*

This document is the first guideline on the topic by the ADA, the first developed by a multidisciplinary panel, and the first intended primarily for general dentists in the United States. Reports from other groups provide similar recommendations to ours; the American Association of Endodontists,11 Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme,10 Faculty of General Dental Practice,14 and the Journal of the Canadian Dental Association68, 69 have previously provided recommendations against antibiotic use for pulpal and periapical conditions, unless there is systemic involvement. Unlike ours, they omitted guidance on first- and second-line antibiotic regimens, did not use GRADE methodology to assess certainty in the evidence and strength of recommendations, and did not incorporate a robust stakeholder engagement process.

Though more broad and medical in scope, a guideline by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America57 also presents a wide range of clinical questions and recommendations related to antibiotic stewardship in inpatient settings. Authors of the report provided recommendations for facility-specific guidelines and algorithms for antibiotic prescribing (conditional recommendation, low certainty), shorter duration of antibiotics (strong recommendation, moderate certainty), and stewardship interventions designed to reduce CDI (strong recommendation, moderate certainty) amongst others.

Implications for research

At the moment, there is a dearth of published evidence on the effect of antibiotic prescribing in outpatient and dental settings on population-level harms; the majority of published research is based on inpatient, medical settings. Also, national observational studies on the harms of antibiotic use presented in both absolute and relative terms would allow guideline developers to better summarize and use this evidence to make decisions.

Furthermore, evidence informing benefits of antibiotics for the target conditions was limited. High-quality, powered studies, especially those using validated scales for measuring patient-reported outcomes like pain, and being careful to provide DCDT to all patients, may provide more trustworthy evidence to inform beneficial outcomes. Also, future studies providing a robust evaluation of antibiotic sensitivity for dental infections, comparative safety and effectiveness of common antibiotic regimens, and optimal antibiotic prescription duration would be useful for decision-making.

Finally, an initial study on antibiotic stewardship programming in an academic dental setting suggests a 73% decrease in antibiotic prescribing7; guideline and policy developers would benefit from more research on the implementation of guidelines/antibiotic stewardship programs in community dental practices to better inform decisions.

Implications for practice

In many cases, some patients with target conditions may present in dental clinics where DCDT is not immediately available and may need repeat visits or a referral to a specialist. Other patients may present in EDs, which may not have easy access to DCDT nor the possibility for further monitoring.70, 71 Clinicians may find that for patients with access to care issues, this guideline’s recommendations may be difficult to implement. However, additional system-level changes to increase access to dental care, a task outside of the scope of this guideline, is needed to resolve this disparity.72

Patient expectation for antibiotics may also present a significant barrier for clinicians implementing these recommendations. The ADA is supplementing this clinical practice guideline with additional materials including an Oral Health Topic73 and a For the Patient Page74 to provide additional insight into antibiotic stewardship and facilitate shared decision-making respectively (both available on ebd.ada.org). National, state, and local health policies, additional community-level partnerships between dentists, pharmacists, and physicians, and the increased use of electronic health records and clinical decision support systems (with the right training/time/resources) can also assist in the implementation of our recommendations.57, 63

Conclusion

An ADA expert panel suggests prescribing antibiotics for immunocompetent adult patients (patients with an ability to respond to a bacterial challenge) with pulp necrosis and localized acute apical abscess in settings where definitive, conservative dental treatment is not available. This recommendation is specific to situations where the risk for systemic involvement is high and a patient may lack immediate access to care. The expert panel suggests not prescribing antibiotics for immunocompetent adult patients with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis with or without symptomatic apical periodontitis, pulp necrosis and symptomatic apical periodontitis, or pulp necrosis and localized acute apical abscess in settings where definitive, conservative dental treatment is available due to potentially negligible benefits and likely large harms associated with their use. *Guidance from other associations has not been formally assessed or endorsed by the ADA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the special contributions of Jeff Huber, MBA and Tyharrie Woods, MA, Science Institute, ADA, Chicago, IL, and Laura Pontillo, Library and Archives, ADA, Chicago, IL.

The authors also acknowledge Michele Junger, DDS, MPH, Division of Oral Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the ADA Council on Scientific Affairs’ Clinical Excellence Subcommittee; Marcelo W.B. Araujo, DDS, MS, PhD, Ruth Lipman, PhD, Jim Lyznicki, MS, MPH, Roger Connolly, Jay Elkareh, PharmD, PhD, Anita Mark, and Sarah Pahlke, MSc, from the Science Institute, ADA, Chicago, IL; Hannah Cho, BS, dental student at Midwestern University College of Dental Medicine-Illinois, Chicago, IL; the ADA Council on Scientific Affairs, the ADA Council on Advocacy for Access and Prevention, and the ADA Council on Dental Practice; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; American College of Emergency Physicians; American Association of Oral Maxillofacial Surgeons; American Association of Endodontists; American Pharmacists Association; American Academy of Physician Assistants; American Association of Public Health Dentistry; National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; American Academy of Periodontology; American Academy of Oral Medicine; American Association of Nurse Practitioners; Organization for Safety Asepsis and Prevention; Veterans Health Administration Office of Dentistry; Infectious Diseases Society of America; Society of Infectious Disease Pharmacists; Dwayne Boyers, M. Econ. Sc, PhD, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, Scotland; Radhika Tampi, MHS, INOVA, Fairfax, VA.; Anwen Cope, BDS, PhD, MPH, Cardiff University, Cardiff, Wales; Douglas Stirling, BSc, PhD, Samantha Rutherford, BSc, PhD, and Michele West, BSc, PhD from the Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme, Dundee, Scotland.

Disclosure. Dr. Durkin receives salary support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes for Health, and the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services. Dr. Fouad receives funding from the Foundation for Endodontics. Dr. Lockhart receives funding from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Patton receives grant funding from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; she is the President of the American Academy of Oral Medicine; a member of the ADA Council on Scientific Affairs; the co-editor of “The ADA Practical Guide to Patients with Medical Conditions”; and the Oral Medicine Section Editor of the journal Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Oral Radiology. Dr. Suda receives funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, the Veteran’s Affairs Health Services Research and Division, the Veteran’s Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development, and the Veteran’s Affairs Quality Enhancement Research Initiative. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government. Drs. Abt, Aminoshariae, Gopal, Hatten, Kennedy, Lang, Paumier, and Ms. O’Brien did not report any disclosures.

APPENDIX

INTRODUCTION

Scope, purpose, target audience

The scope of this guideline is limited to immunocompetent adults. Immunocompetent is broadly defined as the ability of a patient to respond to a bacterial challenge. For practical reasons, clinicians may benefit from specific diagnoses that are not within the scope of this guideline (i.e., immunocompromised patients). We have adapted a list of conditions which may constitute an immunocompromised patient, though it is possible to have one of the below conditions and be able to respond to a bacterial challenge::e1

- Patient with AIDS with an ANC count below, which is defined as HIV with a CD4 T cell count of <200 cells/mm3 or HIV with an AIDS defining opportunistic illness.e2

- AIDS defining opportunistic infections, as defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, include:e3

- Bacterial infections, multiple or recurrent

- Candidiasis of bronchi, trachea, or lungs

- Candidiasis of esophagus

- Cervical cancer, invasive

- Coccidioidomycosis, disseminated or extrapulmonary

- Cryptococcosis, extrapulmonary

- Cryptosporidiosis, chronic intestinal (>1 month’s duration)

- Cytomegalovirus disease (other than liver, spleen, or nodes), onset at age >1 month

- Cytomegalovirus retinitis (with loss of vision)

- Encephalopathy attributed to HIV

- Herpes simplex: chronic ulcers (>1 month’s duration) or bronchitis, pneumonitis, or esophagitis (onset at age >1 month)

- Histoplasmosis, disseminated or extrapulmonary

- Isosporiasis, chronic intestinal (>1 month’s duration)

- Kaposi sarcoma

- Lymphoma, Burkitt (or equivalent term)

- Lymphoma, immunoblastic (or equivalent term)

- Lymphoma, primary, of brain

- Mycobacterium avium complex or Mycobacterium kansasii, disseminated or extrapulmonary

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis of any site, pulmonary, disseminated, or extrapulmonary

- Mycobacterium, other species or unidentified species, disseminated or extrapulmonary

- Pneumocystis jirovecii (previously known as “Pneumocystis carinii”) pneumonia

- Pneumonia, recurrent

- Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

- Salmonella septicemia, recurrent

- Toxoplasmosis of brain, onset at age >1 month

- Wasting syndrome attributed to HIV

Patients with cancer undergoing immunosuppressive chemotherapy with febrile (Celsius 39) neutropenia (ANC <2000) OR severe neutropenia irrespective of fever (ANC <500)

Patients with autoimmune conditions with concomitant use of potent immunosuppressive drugs, such as biologic agents (e.g., tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors) or steroids (e.g., prednisone >10 mg per day). Please note, methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, azathioprine, and other medications with a similar potency should not be considered immunocompromising agents.

Patients with solid organ transplant on immunosuppressants

Inherited diseases of immunodeficiency (e.g., congenital agammaglobulinemia, congenital IgA deficiency)

- Patients with bone marrow transplant in one of the following phases of treatment:

- Pretransplantation period

- Preengraftment period (approximately 0–30 d posttransplantation)

- Postengraftment period (approximately 30–100 d posttransplantation)

- Late posttransplantation period (≥100 d posttransplantation) while still on immunosuppressive medications to prevent GVHD (typically 36 months post transplantation)

METHODS

Panel configuration and conflicts of interest

In 2018, the ADA Council on Scientific Affairs convened a multidisciplinary panel of subject matter experts from general and public health dentistry, endodontics, oral and maxillofacial surgery, oral medicine, infectious diseases, emergency medicine, pharmacology, and epidemiology. Panel nominees completed financial and intellectual conflict of interest forms that were reviewed by methodologists from the ADA Center for EBD. Conflict of interests were disclosed and updated at the beginning of each panel meeting. When relevant conflicts were identified in relation to a particular recommendation, the panel member was asked to abstain from discussion and not participate in formulating that recommendation. In the first panel meeting in April 2018, we defined the scope, purpose, clinical questions and outcomes, and target audience. In the second panel meeting in December 2018, we formulated recommendations.

Body of evidence and outcomes informing this guideline

A complete list of outcomes for total analgesics used refers to total number of NSAIDS used and total number of rescue analgesics used. A complete list of outcomes for progression of disease to more severe state refers to malaise, trismus, fever, cellulitis, additional dental visit, and additional medical visit.

A complete list of outcomes for community-associated CDI is community-associated CDI, community-associated CDI related to a dental prescription for antibiotics, and mortality due to community-associated CDI.

A complete list of outcomes for antibiotic-resistant infections include antibiotic-resistant infections and mortality due to antibiotic-resistant infections.

A complete list of outcomes for costs include community-associated CDI related costs, community-associated CDI related costs associated with a dental prescription for antibiotics, antibiotic-resistant infections related costs, antibiotic-resistant infections related costs associated with a dental prescriptions for antibiotics, and cost-effectiveness of antibiotics to treat symptomatic irreversible pulpitis with or without symptomatic apical periodontitis, pulp necrosis and symptomatic apical periodontitis, or pulp necrosis and localized acute apical.

A complete list of outcomes of hospitalizations include admission to hospital due to community associated CDI, admission to hospital due to community-associated CDI related to a dental prescription for antibiotics, admission to hospital due to antibiotic-resistant infection, admission to hospital due to antibiotic-resistant infection associated with a dental prescription for antibiotics, length of hospital stay due to community-associated CDI, length of hospital stay to community-associated CDI related to a dental prescription for antibiotics, length of hospital stay due to antibiotic-resistant infection, and length of hospital stay due to antibiotic-resistant infections associated with a dental prescription for antibiotics.

A complete list of outcomes of anaphylaxis include allergic reaction to antibiotics, allergic reaction to antibiotics associated with a dental prescription, anaphylaxis due to antibiotics, anaphylaxis due to antibiotics associated with a dental prescription, fatal anaphylaxis due to antibiotics, and fatal anaphylaxis due to antibiotics associated with a dental prescription. The panel ranked allergic reaction due to antibiotics, anaphylaxis due to antibiotics, and fatal anaphylaxis due to antibiotics as critical outcomes. The panel defined and ranked (critical, important, or not important for decision-making) outcomes a priori. The panel ranked pain and intra-oral swelling as a critical outcomes. The panel ranked total number of NSAIDS used and total number of rescue analgesics used, malaise, trismus, fever, cellulitis, additional dental visit, and additional medical visit, allergic reaction, endodontic flare-up, diarrhea, CDI, and repeat procedure as important outcomes. The panel ranked community-associated CDI and mortality due to community-associated CDI as critical outcomes, and community-associated CDI related to a dental prescription for antibiotics as an important outcome. The panel ranked mortality due to antibiotic-resistant infections as a critical outcome, and antibiotic-resistant infections as an important outcome.

The panel ranked community-associated CDI related costs, antibiotic-resistant infections related costs, and cost-effectiveness of antibiotics to treat symptomatic irreversible pulpitis with or without symptomatic apical periodontitis, pulp necrosis and symptomatic apical periodontitis, or pulp necrosis and localized acute apical as critical outcomes. The panel ranked community-associated CDI related costs associated with a dental prescription for antibiotics and antibiotic-resistant infection related costs associated with a dental prescriptions for antibiotics as important outcomes. The panel ranked all hospitalization and anaphylaxis outcomes as important.

Anticipating limited evidence to inform harm outcomes from randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the panel decided to include evidence from RCTs and observational studies to inform this guideline, in that order of priority.

Retrieving the evidence

For beneficial outcomes, the informationist (K.O.), methodologists, and the expert panel updated a 2014 and 2016 Cochrane systematic review.24,25 The published search strategy for the 2016 systematic review24 was adapted for inclusivity by combining the antibiotics search string used in the 2014 systematic review25 with a new, simple pulpectomy/dental pulp concept. Other outcomes required additional evidence, and considering the scope of the Cochrane reviews, we conducted a search for systematic reviews on antibiotic resistance, to identify primary studies related to these outcomes. All searches were ran in MEDLINE via PubMed, Embase via embase.com, the Cochrane Library, and CINAHL in May and early June 2018. In addition, we searched grey literature and national healthcare agency websites and databases, and contacted the CDC to retrieve evidence that may not be available from the electronic databases cited above.20 Using similar methods, we also searched for systematic reviews and primary studies on patients’ values and preferences, and provider acceptability and feasibility related to the use of antibiotics for the target conditions in dentistry, and if not available, from its use in medicine.

Pairs of reviewers (E.K., L.P., M.P.T., O.U., and an author of the related systematic review) independently screened titles and abstracts and full-text articles, and determined final eligibility. Reviewers (L.P., M.P.T., O.U.) then independently and in duplicate extracted data from included studies. We prioritized data specific to outpatient dental settings over inpatient medical settings. When dealing with population-level harm outcomes accounting for all prescriptions in the health system, we adjusted our estimates by 10% to illustrate the impact of antibiotic prescription rate from dentistry in regards to the total outpatient antibiotic prescriptions in the United States in 2011.41

Evidence synthesis and measures of association

Using random-effects model, we pooled data and calculated relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for dichotomous data, and mean difference (MDs) and 95% CIs for continuous data. When meta-analysis was not possible, we reported data at an individual-study level. When comparative effect estimations (e.g., measures of association) were not possible to obtain, we calculated frequency estimates.

Certainty in the evidence

We assessed the certainty in the evidence using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.28 The certainty in the evidence represents the panel’s confidence that the treatment effects are appropriate to inform the recommendations (Table 3).

Moving from evidence to decisions

The expert panel formulated recommendations using the GRADE Evidence-to-Decisions (EtD) framework, facilitated by a methodologist (M.P.T.) during the second panel meeting. The EtD framework allows for a structured display of the pros and cons of implementing an intervention, allowing for guided discussion when formulating recommendations.29 This framework considers eight factors: importance of the healthcare problem, magnitude of desirable and undesirable effects, certainty in the evidence, patient’s values and preferences, balance of desirable versus undesirable effects, acceptability, and feasibility. Once judgments were made for each factor, the expert panel decided the direction and strength of the recommendation (Table 2).26–28

Stakeholder and public engagement

We contacted internal and external stakeholders and invited them to participate in the development of the guideline. Using an electronic survey, we solicited feedback on two occasions. First, we requested input regarding the initial draft of the guideline’s scope, purpose, clinical questions, outcomes, and target audience; and second, input on the final draft of the recommendations and good practice statements (GPS). We also invited the general public to provide input on the recommendations and GPS through social media and the ADA Center for EBD’s Web site (ebd.ada.org). Methodologists classified and prioritized all comments for discussion and resolution with the panel.

Updating Process

The ADA Center for EBD continuously monitors relevant literature. We will update this guideline every five years or when new evidence may affect the direction and strength of the recommendations. Any updated versions of this guideline will be available at ebd.ada.org.

RESULTS

Values and Preferences