ABSTRACT

Social, environmental, and behavioural factors impact human health. Integrating these social determinants of health (SDOH) into electronic health records (EHR) may improve individual and population health. But how these data are collectedand their use in clinical settings remain unclear. We reviewed efforts to integrate SDOH into EHR in the U.S. and Canada, especially how this implementation serves Indigenous peoples. We followed an established scoping review process, performing iterative keyword searches in subject-appropriate databases, reviewing identified works’ bibliographies, and soliciting recommendations from subject-matter experts. We reviewed 20 articles from an initial set of 2,459. Most discussed multiple SDOH indicator standards, with the National Academy of Medicine’s (NAM) the most frequently cited (n = 10). Common SDOH domains were demographics, economics, education, environment, housing, psychosocial factors, and health behaviours. Twelve articles discussed project acceptability and feasibility; eight mentioned stakeholder engagement (none specifically discussed engaging ethnic or social minorities); and six adapted SDOH measures to local cultures . Linking SDOH data to EHR as related to Indigenous communities warrants further exploration, especially how to best align cultural strengths and community expectations with clinical priorities. Integrating SDOH data into EHR appears feasible and acceptable may improve patient care, patient-provider relationships, and health outcomes.

KEYWORDS: Social determinants of health, electronic health records, stakeholder engagement, culturally competent care, American Indian and Alaska Native people

Background & significance

Extensive research has shown the profound impact of adverse environmental, social, and behavioural conditions on human health [1–21], emphasising the importance of what are commonly referred to as social determinants of health (SDOH) [22,23]. Clinical care has been cited to influence 10 to 20% of a patient’s outcomes, while SDOH impact the remainder [22,23]. In a comprehensive analysis of the contribution of social factors to mortality, researchers examined data from adult deaths in 2000 and found that poverty, low levels of education, poor social support, and racial segregation contribute about as many deaths in the U.S. as heart attacks, strokes, and lung cancer [24]. A broader understanding of SDOH that is informed by community and stakeholder input may improve the health of populations, particularly Indigenous populations who have experienced social, economic, and political disadvantages through colonialism. Across the Arctic, ministries of health and leaders have focused on health disparities of Indigenous peoples and the impacts of determinants, such as food security, climate change, and health systems [25]. In developing a collaborative research agenda for health systems in circumpolar regions, experts have emphasised the need to understand context and values underlying health and wellness, specifically in Indigenous populations. They have also called for broader definitions of health and health systems that recognised the underlying determinants of health [26]. Circumpolar regions have shared values and contexts [26], and identifying social determinants of health will help national, territorial and northern regional authorities in the Arctic develop policies and programmes to address health disparities.

Healthcare providers have integrated SDOH-like data into medical practice since at least the early 1900s [4]. As soon as electronic health records (EHR) became available in the 1970s, providers began advocating for acquiring, storing, and using SDOH data in EHR [27]. Half a century later, there is still no universal standard set of SDOH indicators [28,29]. International groups, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organisations have attempted to develop standardised lists of SDOH to integrate into EHR. Primary drivers of this work have included the World Health Organization (WHO) Commission on SDOH [30]; National Academy of Medicine (NAM) (formerly the Institute of Medicine (IOM)) Committee on the Recommended Social and Behavioural Domains and Measures for EHR [31,32]; U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [33]; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) Healthy People 2020 (HP2020) framework [34]; Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Meaningful Use EHR standards [4,9,10,27,29,35–40]; Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) County Health Rankings and Roadmaps [6]; and the National Association of Community Health Centers (NACHC) Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks, and Experiences (PRAPARE) EHR toolkit [37,41]. Most SDOH paradigms emphasise risk, that is, the degree to which social and behavioural factors increase the odds of developing or maintaining negative health states [42]. However, as with any health risk indicator (e.g. high cholesterol), not all people who screen positive for an SDOH factor will have equivalent outcomes. Some SDOH, such as having a high income or an advanced degree, is protective factors that can increase the odds of attaining or maintaining positive health states. Elements that mitigate risk and promote resilience and social-relational competence are often called protective factors. Identifying to what extent SDOH contribute to protective factors and how these aspects of SDOH should be annotated in EHRs, is particularly relevant for health organisations serving Indigenous populations who face higher burdens of disease.

SDOH can have unique expressions in Indigenous communities [17,43–46]. For example, a WHO report [17] noted that political self-determination, connection to the land, and colonial damages to traditional social structures and cultures are important drivers of health in Indigenous communities. The cultural-relevancy of SDOH indicators, and the cultural-sensitivity of the process of collecting SDOH data and integrating them into EHR, should be taken into consideration when working with social or ethnic minority groups, such as Indigenous people. This review emphasised stakeholder engagement in the process of integrating SDOH into EHR.

Objective

This scoping review analyzes efforts to integrate SDOH data into EHR systems. It emphasises the cultural-relevancy and cultural-sensitivity of that process and examines stakeholder engagement. Since the authors work in a health setting serving Indigenous people, and due to the pressing need for and unique challenges of providing high-quality medical care to Indigenous populations, we were particularly interested in the integration of SDOH into EHR among health organisations serving Indigenous peoples.

Materials and methods

We followed Arksey and O’Malley’s scoping review methodology [47] and iteratively refined our research question. Per their recommendation, our research questions addressed three key areas: context (integrating SDOH data into EHR systems), population (healthcare systems in the U.S. and Canada, especially those serving Indigenous peoples), and concept (strategies including stakeholder engagement processes in integrating SDOH into EHR). Our research question was: “How have healthcare systems in the U.S. and Canada integrated SDOH and protective factors into EHR, and what strategies did they use to tailor SDOH to the population they serve?”

Search strategy

We conducted preliminary searches in PubMed and Google Scholar from a priori and inductive understandings of the topic. From these, we iteratively expanded our keyword lists then translated those keywords into the hierarchically-arranged Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) used by PubMed [48].

Keywords form three categories: SDOH, EHR, and Stakeholder Engagement, linked together with Boolean operators (e.g. AND, OR, NOT). All search results included at least one keyword from all three MeSH lists (SDOH “AND” EHR “AND” Stakeholder Engagement) but “NOT” any keywords marked irrelevant. Table 1 includes primary keywords used in our search. We also identified articles by reviewing the cited references of included articles (bibliography review) and requesting recommendations from subject-matter experts within our organisation.

Table 1.

Primary keywords and syntax used for literature search

| #1 |

Social determinants of healtha OR Social behavioural determinants of health OR health related social needs OR social justice OR health equity |

| #2 |

Electronic health recordsa OR Electronic medical records OR medical record system OR health information OR patient records OR digital health records OR health information exchange |

| #3 |

Stakeholder engagementa OR Patient participation OR community participation OR community-based participatory research OR data sharing OR feasibility OR acceptability OR sensitivity OR adaptation OR cultural relevance OR cultural sensitivity OR community advisory board OR interviews OR focus groups OR surveys |

aLower order MESH terms under each primary keyword term were also included in searches. See Supplements 1 and 2 for more detail.

Article selection

We started by first reviewing the title and abstract of each article, filtering out the ones that were not relevant to integrating SDOH into EHR or using stakeholder engagement to discuss SDOH and EHR. We then reviewed the full-text each remaining article for relevancy. Data elements were manually extracted and analysed for themes. Data elements included bibliographic information (e.g. publication year, journal), study focus (SDOH, EHR, or stakeholder engagement), study type (original research, commentary, and review), population of interest (e.g. Indigenous peoples), type of healthcare setting (e.g. FQHC), SDOH domains, attempts to culturally adapt SDOH indicators, how the study integrated SDOH data into the EHR, and acceptability and feasibility outcomes.

After preliminary review, we realised the articles were not consistently relevant in topic and approach. Per Arksey and O’Malley’s scoping review methodology [47], we iteratively refined our research question and revised our eligibility criteria by limiting the time frame and narrowing our scope. Articles included in the scoping review were written after 2004 (i.e. after EHRs became more common), and addressed either technical processes or stakeholder engagement around integrating SDOH into EHR. Articles were excluded if they were set outside the U.S. and Canada, exclusively used EHR as data sources (i.e. did not integrate SDOH data into EHR), or did not address more than one SDOH. We applied this eligibility refinement to articles that passed preliminary title and abstract review and reviewed the full text of each article.

In reviewing each article, we paid close attention to the extent to which SDOH had been integrated in the EHR. Across the 20 articles, we examined the type of standard used, the frequency in which specific SDOH domains that were mentioned, extent of stakeholder engagement, cultural adaptations, acceptability and feasibility of implementation, and barriers to implementation and any proposed strategies to mitigate barriers.

Results

Article selection

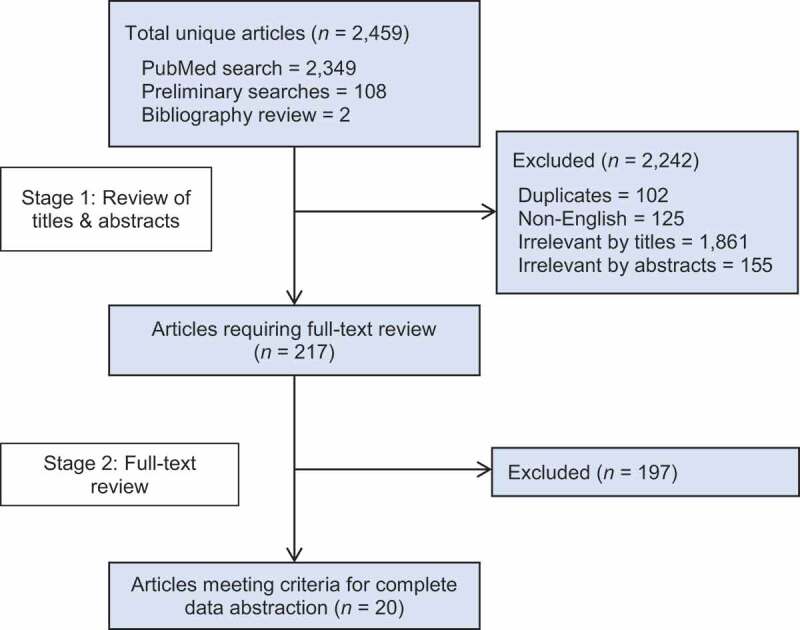

Figure 1 presents a flow chart of the article selection process and results from the complete systematic search.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection process

The total number of unique articles (n = 2,459) was the result of our PubMed search, preliminary background searches, and bibliography review. After reviewing titles and abstracts of the 2,459 articles, we excluded 2,242 articles due to them being duplicates, written in a language other than English, or irrelevant to SDOH, EHR, and/or stakeholder engagement. We reviewed 217 articles and included 20 articles for our scoping review due to their direct relevance.

Study characteristics

Of the 20 articles included in this scoping review, 18 were based in the U.S.; Mayo et al. [49] and Pinto et al. [50] were set in Canada. Five documents were grey literature from the Society of Behavioural Medicine, NACHC and NAM. The selected articles were published between 2004 and 2018, though most were dated between 2014 and 2017. Only 1 of the 20 articles focused primarily on stakeholder engagement in the context of integrating SDOH in EHR. Extent to which SDOH has been Integrated into EHR

For each of the 20 articles, we list the SDOH standard source used, whether stakeholder engagement occurred, and whether the SDOH was culturally adapted (Table 2). Almost half the study articles (n = 8) examined multiple standardised SDOH indicator lists. The most commonly cited standard (n = 10) was from the NAM, although eight articles did not report which standard they followed. The most frequently discussed SDOH domains in descending order were demographics, psychosocial factors, economics, health behaviours, education, environmental factors, housing, and relationships.

Table 2.

SDOH domains addressed in study articles

| Author | SDOH Standard | SDOH Domain |

Stakeholder Engagement? | SDOH Culturally Adapted? | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Economics | Employment | Education | Political/Historical Conditions and Colonialism | Environment | Housing | Non-Clinical Medical | Governmental | Public Health | Psycho-Social | Health Behaviours | Transportation | Relationships | Cultural Identity | ||||

| Adler et al [28]. | National Academy of Medicine | X | X | X | X | No | No | |||||||||||

| Ancker et al [52]. | Not reported | No | No | |||||||||||||||

| Bakken et al [56]. | Not reported | X | No | No | ||||||||||||||

| Bazemore et al [27]. | National Academy of Medicine | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | No | No | ||||

| Estabrooks et al [38]. | Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; National Academy of Medicine | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | Yes | No | ||||||

| Foucher-Urcuyo et al [53]. | Not reported | X | X | No | No | |||||||||||||

| Glasgow et al [55]. | Healthy People 2020; National Academy of Medicine | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | Yes | No | ||||

| Gold et al [7]. | National Academy of Medicine; National Association of Community Health Centers, OTH | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Gottlieb et al [9]. | National Academy of Medicine | X | X | X | X | X | X | No | No | |||||||||

| NAM (a) [31] | Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; National Academy of Medicine | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| NAM (b) [32] | Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; National Academy of Medicine | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Lewis et al [14]. | Healthy People 2020; National Academy of Medicine; World Health Organization; | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | No | Yes | |||||

| Mayo et al [49]. | Not reported | X | X | X | X | X | No | No | ||||||||||

| NACHC (a) [37] | Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, National Association of Community Health Centers | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | Yes | No | ||||

| Nguyen et al [51]. | Not reported | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | Yes | No | |||||

| Palacio et al [19]. | National Academy of Medicine | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| Pincus [58] | Not reported | X | X | X | X | X | X | No | No | |||||||||

| Pinto et al [50]. | Not reported | X | X | X | X | X | X | No | Yes | |||||||||

| Society of Behavioural Medicine [54] | Not reported | X | X | X | X | X | X | No | No | |||||||||

| Total counts | 17 | 14 | 8 | 12 | 0 | 11 | 9 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 15 | 14 | 5 | 9 | 3 | 8 | 6 | |

Eighteen of the 20 articles focused on individual-level SDOH, but Nguyen et al. [51] and Bazemore et al. [27] both addressed community-level indicators. Nguyen et al. [51] explored the feasibility of developing a social health information exchange to share data between healthcare and social service organisations, built on a “patient-centered medical neighborhood” model. Community-level SDOH they discussed included tracking eligibility requirements and availability of local social service programmes, and number and type of social service referrals made by providers.

Bazemore et al. [27] discussed SDOH in terms of “community vital signs”, using data from the U.S. Census and other Federal agencies (e.g. CDC and Environmental Protection Agency) to build profiles of the built environment (e.g. liquor stores per 100,000 people), environmental hazards (e.g. ozone pollution), and neighbourhood composition (e.g. racial/ethnic composition, andsocioeconomic status), as well as using the Robert Graham Center’s Social Deprivation Index. Geocoded data can be automatically imported into EHR by a HIPAA-compliant custom application programming interface (API) as long as the patient has a valid address (i.e. one that a geotag can be attached to).

Among health systems considering which SDOH to include in the EHR, most health systems focused on community deficits, such as pollution, presence of liquor stores, percent living in poverty. Health systems also include individual barriers, such as low-income or lack of a car. However, few mentioned incorporating community assets, such as libraries, presence of civic groups, green space, or individual protective factors, such as strong social support or access to reliable transportation. Many times, this means important reframing to also document the presence of a positive attribute rather than only the presence of a negative attribute.

Degree of stakeholder engagement

Eight articles mentioned stakeholder engagement. All reported engaging with healthcare and social services staff (i.e. providers and administrators) but only two with patients or clients. None of these 20 articles specifically reported engaging with specific racial, ethnic, or minority patients, such as Indigenous, LGBTQ, or people with disabilities, about the use of SDOH information in healthcare delivery.

Estabrooks et al. [38] engaged in three phases of stakeholder engagement. In Phase I, they convened subject-matter experts from government healthcare agencies, EHR vendors, non-profits, and national medical organisations and professional societies. These expert panels nominated SDOH domains to prioritise. Phase II then utilised an online tool, the grid-enabled measures (GEM) wiki-platform run by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), to have stakeholders rate the candidate measures according to select criteria. Finally, Phase III reconvened stakeholders, including some patient advocacy group representatives, in a large town hall style meeting to review the candidate domains and measures identified in Phases I and II, and select one final measure for each domain. The authors state their next step for the project would be continuing stakeholder engagement with patients and providers to assess their impression on the appropriateness of these domains and measures.

Glasgow et al. [55] conducted online discussions through the NCI GEM forum, mentioned above, to select candidate measures that fit their SDOH domains. These discussions included providers, patients, and policymakers. Gold et al. [7] engaged with expert stakeholders from three CHC clinic locations, OCHIN (a non-profit that administers approximately 440 CHC EHR systems), NACHC’s PRAPARE leadership team, Kaiser Permanente, Epic (the EHR vendor), and other SDOH experts. CHC clinic participants included providers, clinic administrators, and support staff. Estabrooks et al. [38] explicitly built on the work of Glasgow et al. [55], such as using their domain selection criteria.

The NAM [31,32] relied on a Committee of experts to compile its recommendations. The Committee primarily consisted of academics and educators working in fields such as medical informatics, behavioural health, primary care, paediatrics, medical schools, epidemiology, and public health, or those with an expertise in research methods and measurement. Additional input was provided to the Committee from invited health experts in government (e.g. from the NIH or CDC or State health agencies), medical insurance, and health-related non-profits. Per Federal policy, the NAM’s two Phase I and four Phase II half-day community engagement meetings had opportunities for public input, but it was not reported if general community members participated in these events nor if anyone else provided patient-level input.

Nguyen et al. [51] conducted 50 interviews for their project, but none with patients. The data from these interviews helped develop a list of SDOH indicators they could track in their proposed social health information exchange. They reviewed this draft list with stakeholders in a town hall meeting to prioritise the most important indicators, but did not report the indicators ultimately selected. Town hall attendees were all healthcare and social service organisation staff.

Palacio et al. [19] assembled a committee of “champions” to support their project, including “the chief executive, chief operating, and chief information, officers [sic] and dean, clinical committees, clinic administrators, quality improvement committees, nursing and ancillary staff for specific clinics, and patients”. Champions advised which SDOH were most relevant and what challenges the system might face in integrating SDOH into EHR. Alongside Glasgow et al. [55], this was the only other article that mentioned patient engagement, but it was not clear what proportion of their “champions” were patients. Pinto et al. [50] conducted key informant interviews with staff at allied local healthcare organisations to better understand which SDOH screening questions they should ask and in which languages.

Cultural adaptation

Six articles discussed adapting SDOH measures to their local culture and environment. Strategies implemented included adding locally relevant domains to existing standardised SDOH domains and reprioritizing domains that were actionable for populations served or indicators that were reliably measured. Additional strategies included meeting community preferences by tailoring the wording of screening questionnaires to be culturally appropriate or screening in multiple languages. Gold et al. [7] reviewed the recommendations from the NAM, NACHC, and others, selecting some elements and creating others to suit their local needs. Additional elements included food security and gender and sexual identity. The wording of many screener questions was changed to better fit the preferences of the low-income population served by their community health centre.

Lewis et al. [14] reviewed the SDOH indicator lists from NAM, HP2020, and WHO, and identified the SDOH most relevant to the marginalised populations served in their CHCs. For example, their rural-serving California CHCs added immigrant status as an SDOH, while their urban-based New York and Illinois CHCs added insurance coverage, homelessness, and housing stability.

Palacio et al. [19] adapted the NAM indicator list by adding SDOH for their Florida location, namely, “country of origin, years living in the USA, language preference, acculturation, health literacy, food insecurity, living arrangements, and transportation”. This acculturation measure was the only example we found of our SDOH cultural identity domain being used in practice.

Pinto et al. [50], did not report following a SDOH standard, but chose indicators based on reviews of published literature and adapted their list over 4 years in consultation with their four partner organisations in the urban Toronto area. Their indicators included religious or spiritual affiliation, disability status, and sexual orientation.

Acceptability and feasibility

Twelve articles reported on the acceptability and feasibility of integrating SDOH into the EHR. Acceptability was lower among patient populations with low health literacy, in situations in which the purpose was not adequately communicated or understood, where screening questions were not actionable by the provider, and when screening administration and review processes did not allow for timely follow-up by provider. Bakken et al. [56], performing a secondary analysis of survey data from 2,000+ Latinx residents in a New York City neighbourhood, reported 96% of their respondents would find it acceptable to link SDOH data to their EHR. Respondents on government insurance like Medicare or Medicaid (a proxy for low socioeconomic status), or who had low health literacy, were less likely to find such linkage acceptable. In general, there was limited information about engaging patients to better understand acceptability.

To increase acceptability, NAM [31,32] prioritised SDOH domains that were evidence- based, came from existing reliable sources of data, and were actionable in a clinical setting. In addition, it was important that these data were already routinely collected by health care organisations nationwide and would not greatly disrupt the clinical workflow. Another important consideration was that the SDOH information, when viewed together, provided a comprehensive and holistic understanding of the person in context.

For providers, acceptability of integrating SDOH into the EHR was closely tied to its feasibility. Information about SDOH must first be collected from patients – for example, through self-report in a screening questionnaire – and then stored in the EHR. Gold et al. [7] noted that two of their three CHC study locations used paper screeners, rather than tablets, which created an implementation barrier. Paper forms must be manually entered into the EHR, which was not always completed by the appointment, and can interrupt clinical workflow. Similarly, they stated that even when using online portals for SDOH data self-entry, patients struggled to complete the form before their appointment.

Lewis et al. [14] ran an observational study looking at how well providers could assess, code, and bill for addressing the SDOH needs of patients. Providers reported being comfortable assessing their patients’ SDOH needs and were able to address 31% of their problems, but they provided a diagnosis code for only 7% of these problems and billed for only 1% of them. Lewis et al. noted that although ICD-10 Z-codes can be used for SDOH-related problems, they are not specific to SDOH, do not always capture the specific nature of the SDOH problem, and may be unfamiliar to providers.

NACHC [37,57] reported their PRAPARE screening tool was easy to use (e.g. took <9 minutes to complete) and helped them identify unmet SDOH needs that often led to forming new community partnerships. PRAPARE was set up to align with the CMS’ Meaningful Use standards and ICD-10 codes, to streamline data collection and communications with payers. NACHC reported a “very high” patient completion rate, noting that commonly unanswered questions seemed to result from a lack of health literacy mitigatable by having opportunities to ask staff questions. Staff reported the screener helped them understand and build relationships with their patients; patients appreciated being asked questions about their SDOH needs and were comfortable answering them. However, challenges reported included staff initially not understanding why SDOH screening was being implemented, why they should screen for things the provider could not address, and how to integrate the screener into workflows. NACHC addressed these challenges via internal messaging to explain to staff the utility of screening, the need to screen to identify which new services to add to address unmet needs, and to encourage staff to minimise workflow disruption by offering patients the screener while either waiting to be seen or after the visit. They also stated that providers were initially frustrated screening for issues they could not fix. However, the longer they used the screener, the more issues they realised the health system could address. When the screener led to establishing new partnerships in the community to help meet additional unmet needs, providers experienced an increased sense of empowerment and job satisfaction. Yet, NACHC also noted the need to “develop the trauma-informed care skills to learn about people’s difficult experiences without causing re-traumatisation”, and similarly reported that screening for SDOH needs took an “emotional toll on staff”. NACHC has used these SDOH data to identify new services to meet individual-level needs; to identify which community partnerships to prioritise to meet population-level needs (e.g. to establish bi-directional referral procedures, or discount programmes); and to inform their advocacy work on state and national policy.

During pilot testing, Palacio et al. [19] mentioned several issues affecting clinical workflow with their screener, for which they tested several deployment options. Deploying it through their online patient portal drew attention to challenges around data security and their patients’ generally low utilisation of the portal. Following pilot implementation, they removed depression, alcohol, and domestic violence from their screener. These topics required “timely reaction” to a positive screen, so providers instead asked about them during the visit where they could be addressed immediately. Additionally, they assigned a dedicated staff member to steward the SDOH data and present regular reports to clinical leadership on potential improvements.

Pincus [58] reported on an effort to update the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) – originally developed by Stanford in 1980 – to a multidimensional HAQ (MDHAQ). The HAQ takes about 5–10 min to quantitatively assess functionality in rheumatoid arthritis patients (e.g. limitations in activities of daily living), as well as SDOH-like income and health behaviours. The questionnaire was administered by the clinic receptionist, who explained to patients that it was designed to help the doctor provide the best care possible. Pincus observed, if the patient or staff believed the form was only for research or to collect a medical history, they would lose interest. But if they thought it would improve care, they typically found it not difficult to implement. Noting that the tool takes seconds to scan with the eye, Pincus stated the HAQ screener is a faster way to assess patient function, pain, and status than standard clinical interview. He emphasised the importance of completing the form in the waiting room so it would be available to the provider during the encounter. He envisioned developing an electronic multidimensional HAQ (eMDHAQ) to allow patients to send a copy of their form to a secure online patient portal, where they could print off additional copies of the screener for other entities requesting similar documentation.

Barriers and facilitators to integrating SDOH into EHR

Table 3 summarises some of the main barriers and facilitators to integrating SDOH into EHR as noted by the reviewed study articles.

Table 3.

Barriers and facilitators of integrating SDOH data into EHRs

| Category | Barriers | Facilitators |

|---|---|---|

| Domain Indicators |

|

|

| Screening and Measurement |

|

|

|

Screener Data Collection Methods and Procedures |

|

|

| Patient-Provider Relationships |

|

|

| Health System |

|

|

| Payers |

|

|

Discussion

SDOH have received increasing attention in recent years, but relatively little has been written about how to integrate SDOH into EHR, or how to comprehensively engage stakeholders in that process to increase its utility in improving health outcomes. We did not find any literature specific to integrating SDOH into EHR for Indigenous people. Further, protective factors were not widely recognised nor documented as SDOH. For Indigenous populations, cultural identity, extended family, sense of community, social supports, community networks, organisational involvement are all strengths and assets that can play a large role in health promotion and advancing health outcomes.

This review suggests that integrating SDOH data into EHR systems is likely acceptable among providers and clinical leadership. Wording screening questions carefully to avoid retraumatising patients, training staff to manage secondary trauma, communicating the rationale for screening to both staff and patients, and managing data securely appear to be key conditions for acceptability among patients. For healthcare systems seeking to integrate SDOH into EHR, engaging patients about the process can build acceptability and consensus around its value and utility.

In addition, integrating SDOH into EHR is a feasible endeavour that can be accomplished by capturing data through a screening questionnaire of social needs – or from a strengths-based approach, a screening questionnaire of social assets. Paper and computer-based screeners both have limitations and advantages, and no best practice has emerged to guide when or how to collect, store, and cross-reference SDOH data. Finally, the integration of SDOH into EHR may improve patient care and patient-provider relationships by stimulating conversation, promoting shared decision-making, expanding social service referrals, identifying unmet needs, and guiding the formation of community partnerships.

As mentioned earlier, there is a substantial need for comprehensive stakeholder engagement processes concerning the integration of SDOH into EHR. Archer et al. [59] note that the adoption of Personal Health Records (PHRs), which are often tethered to physician EHRs, often fail due “to little consumer involvement during planning, design, and implementation”. While we did identify eight articles on SDOH-EHR stakeholder engagement, they almost exclusively engaged healthcare and social services staff, despite “the maxim ‘Nothing about me without me’ … used to summarise the principles of patient-centered care and shared decision-making”. [60] While it is encouraging to see provider engagement reported in our study articles, according to Lintern and Motavalli [61], all too often, computerised health applications are designed by software engineers with little input even from providers experienced in day-to-day healthcare provision. The lack of user input in the design of systems to capture data has resulted in workflow inefficiencies, degraded customer service, and increased safety risks. However, while only two of our study articles reported directly engaging with patients, Lewis et al. [14]. noted that all CHCs are “governed by a board of directors consisting of local community members with a makeup of at least 51% health center patients”. Four of our studies took place in CHCs, and their stakeholder engagement may have included patients, even if not specifically reported in their publications. Comprehensive stakeholder engagement (e.g. with medical and social service providers, leadership, support staff, and consumers) can align SDOH domains and data collection with community values, create buy-in, prevent workflow disruptions, and assist staff in managing secondary trauma exposure.

Patient engagement is important for any health system. It is especially relevant for health organisations serving Indigenous populations or geographically isolated Arctic populations, as self-determination over health reinforces the need for robust stakeholder engagement [17,44,62]. The substantial gap in the literature around integrating SDOH into EHR in health settings servicing Indigenous populations indicates ample opportunity for further research. For example, integrating Indigenous concepts of health and wellness into medical care may improve outcomes for Indigenous peoples [17,44–46]. Some have even called for the integration of “traditional healers and medicine people” into stakeholder engagement carried out in Indigenous communities [44]. Likewise, many studies recognise colonialism and historical trauma as SDOH for Indigenous peoples [13,17,44,46,63]. Indigenous peoples – and other racial, ethnic, gender, and sexual minorities – have their own sense of what factors influence health and wellbeing, and it is incumbent on the systems that serve them to recognise and honour those understandings. Similarly, social determinants of health are driven by geographic constraints. Engaging patients to better understand and measure those distinct social determinants of health that exist in those the geographic constraints of the Arctic will inform efforts to address health disparities. Just as several of health systems adapted measures of social determinants of health by geography [14,16], it appears that adaptation of measures to context would be critical in circumpolar health systems. For example, many Arctic communities have substantial seasonal employment in fishing, tourism, and oil and natural gas which contrasts to the emphasis in migrant farm work outside of the Arctic. Other examples, often to do to the Arctic context or lack of redundancy of systems, may include extremely high-cost or unreliable utilities, seasonality in reliable transportation, and unpredictability of ice conditions or animals hunted for food due to climate change.

There is a major gap in the literature around how SDOH can serve as protective factors or resilience indicators. The studies we reviewed tacitly or explicitly characterised SDOH as risk factors, following a deficit model of healthcare delivery. There is a significant opportunity to discuss challenges and potential advantages of categorising some SDOH as protective factors (e.g. based on the presence or absence, or positionality along a spectrum), as well as integrating other strength-based approaches to healthcare into EHR systems. For example, many EHR systems incorporate a “problem list” (deficits and risk factors, like diagnoses and struggles) but few incorporate a “resource list” (adequacy and protective factors, like support networks, community resources being utilised by the patient).

Strides continue to be made to integrate SDOH into medical care. For example, strategies to code SDOH in EHR have been explored for ICD-10 Z-codes [10,14,16,19,57], the Systematised Nomenclature of Medicine – Clinical Terms (SNOWMED CT) [16,27], geospatial data [4,27,64], and the Omaha System (a nursing EHR) [16]. One of the more comprehensive efforts to integrate SDOH into EHR is the PRAPARE toolkit discussed above. PRAPARE [57] provides SDOH screening and action item templates for four EHR systems: Epic, GE Centricity, eClinicalWorks, and NextGen, and templates are in development or have been requested for Greenway, Allscripts, Athena, and Cerner [37]. The ultimate utility of these efforts will depend on the relevance of the SDOH indicators to, and the needs of, the populations being served by the healthcare system.

Integrating sensitive non-medical data into EHR requires careful consideration. Even without reflecting on SDOH data, the majority of adults in the US are “concerned about the privacy and security of their health information”. [59] Nor are data breaches strictly hypothetical. In 2018, a major medical testing company’s billing system was breached, exposing the “names, dates of birth, addresses, phone numbers, dates of service, providers and balance information” (but no medical data) of 20 million customers, as well as credit card or bank account information from 200,000 customers [65]. Digital vulnerabilities can be difficult to spot and disclosure of medical diagnoses or SDOH factors can result in stigma or discrimination [66]. Finally, any efforts to integrate multiple systems, such as healthcare and social services records, will have to deal with the general lack of EHR system interoperability [67,68].

Limitations

While the PubMed search strategy was comprehensive, not all PubMed articles are appropriately tagged with MeSH terms. Our study was limited to post-2004 articles from the U.S. and Canada. Adding more keyword searches in other databases, exploring more grey literature, and expanding inclusion criteria may identify additional articles. Future efforts should expand the extent of the investigation to other countries and to non-English journals.

Conclusion

Healthcare organisations already collect substantial SDOH data, but that collection is not always systematic nor are the data necessarily leveraged adequately to improve care in context. Integrating SDOH data into EHRs systematically, such as through a paper or digital screener, seems feasible and acceptable to most stakeholders, and can improve patient care and patient-provider relationships. It is important to demonstrate to patients that the information they share is valued, informs practice, and improves health, and will not be used against them or cause them harm (e.g. discrimination, stigma, shame). There remain opportunities to better document the process of integrating SDOH into EHR and any stakeholder engagement that might accompany that task, and to comprehensively engage all stakeholders in the integration process, especially patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the members of the study team who were not part of the writing process: Ellen Tyler, Mike Hirst, Monroe Golovin, Charles Fletcher, Linda Erdmann, John Trainor, Kim Hilliard, and Freda Berlin. Thanks also to our former study team members Joe Ambrosio and Julia Smith. Finally, we would like to thank those who provided valuable editorial assistance during the writing process: Sue Brown Trinidad and Krista Schaefer.

Funding Statement

The authors were supported by Award #1CPIMP171148 from the U.S. DHHS Office of Minority Health. The contents of this manuscript are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the Office of Minority Health; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [1CPIMP171148];

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Disclosure of statement

The authors have no financial disclosures to report.

Ethical approval

This study was deemed quality assurance/quality improvement by the relevant Southcentral Foundation tribal review bodies and does not involve human subjects research.

References

- [1].Koh HK, Piotrowski JJ, Kumanyika S, et al. Healthy people: a 2020 vision for the social determinants approach. Health Educ Behav. 2011;38(6):551–12. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Byhoff E, Cohen AJ, Hamati MC, et al. Screening for social determinants of health in michigan health centers. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30(4):418–427. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Clark MA, Gurewich D.. Integrating measures of social determinants of health into health care encounters: opportunities and challenges. Med Care. 2017;55(9):807–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].DeVoe JE, Bazemore AW, Cottrell EK, et al. Perspectives in primary care: a conceptual framework and path for integrating social determinants of health into primary care practice. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(2):104–108. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].OHIT . Review of social determinants of health used in electronic health records and related semantic standards. St Paul, MN: Office of Health Information Technology, Minnesota e-Health; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Carger RWJF,E, Westen D, A new way to talk about the social determinants of health. R.W.J. Foundation , Editor. 2010.

- [7].Gold R, Cottrell E, Bunce A, et al. Developing Electronic Health Record (EHR) strategies related to health center patients’ social determinants of health. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30(4):428–447. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gottlieb L, Hessler D, Long D, et al. A randomized trial on screening for social determinants of health: the iScreen study. Pediatrics. 2014;134(6):e1611–8. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Gottlieb LM, Tirozzi KJ, Manchanda R, et al. Moving electronic medical records upstream: incorporating social determinants of health. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(2):215–218. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gottlieb L, Tobey R, Cantor J, et al. Integrating social and medical data to improve population health: opportunities and barriers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(11):2116–2123. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hillemeier M, Lynch J, Casper M. Data set directory of social determinants of health at the local level. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Controle and Prevention; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [12].RHIH . Social determinants of health for rural people. Grand Forks, ND: Rural Health Information Hub; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kolahdooz F, Forouz N, Kyoung J, Sangita S. Understanding the social determinants of health among Indigenous Canadians: priorities for health promotion policies and actions. Global Health Action, 2015. 8: p. 10.3402/gha.v8.27968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lewis JH, Whelihan K, Navarro I, et al. Community health center provider ability to identify, treat and account for the social determinants of health: a card study. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17(1):121. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Marmot M. Social determinants and the health of Indigenous Australians. Med J Aust. 2011;194(10):512–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Monsen KA, Kapinos N, Rudenick JM, et al. Social determinants documentation in electronic health records with and without standardized terminologies. West J Nurs Res. 2016;38(10):1399–1400. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mowbray M, Social determinants & indigenous health: the international experience and its policy implications, in International Symposium on the Social Determinants of Indigenous Health. 2007, Adelaide, NSW: Commission on Social Determinants of Health, World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- [18].WHO . Social determinants of mental health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Palacio A, Suarez M, Tamariz L, Seo D. A road map to integrate social determinants of health into electronic health records. New Rochelle, NY: Popul Health Manag; 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Raphael D. The health of Canada’s children. Part III: public policy and the social determinants of children’s health. Paediatr Child Health. 2010;15(3):143–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Solar O, Irwin A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. C.o.S.D.o. Health , Editor. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [22].McGinnis JM, Williams-Russo P, Knickman JR. The case for more active policy attention to health promotion. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21(2):78–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Booske B, Athens J, Kindig D, Remington P. Different perspectives for assigning weights to determinants of health. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [24].School W. Why addressing social factors could improve U.S. health care., in knowledge@Wharton. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Chatwood S, Paulette F, Baker G, et al. Indigenous values and health systems stewardship in circumpolar countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(12):1462. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Chatwood S, Bytautas J, Darychuk A, et al. Approaching a collaborative research agenda for health systems performance in circumpolar regions. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2013;72(1):21474. 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.21474. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bazemore AW, Cottrell EK, Gold R, et al. “Community vital signs” : incorporating geocoded social determinants into electronic records to promote patient and population health. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(2):407–412. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Adler NE, Stead WW. Patients in context--EHR capture of social and behavioral determinants of health. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(8):698–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hripcsak G, Forrest CB, Brennan PF, et al. Informatics to support the IOM social and behavioral domains and measures. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015;22(4):921–924. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].WHO . Commission on social determinants of health, 2005-2008. 2019. [cited 2019 Oct 30]; Available from: https://www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/en/.

- [31].IOM . Capturing social and behavioral domains in electronic health records: phase 1. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2014. p. 136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].IOM . Capturing social and behavioral domains and measures in electronic health records: phase 2. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2014. p. 374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].CDC , Data set directory of social determinants of health at the local level, D.o.H.H. Services , Editor. 2004: Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- [34].DHSS , Phase I report: recommendations for the framework and format of healthy people 2020, D.o.H.H. Services , Editor. 2008.

- [35].CMS , CMS finalizes definition of meaningful use of certified Electronic Health Record (EHR) technology, D.o.H.H. Services , Editor. 2010.

- [36].Alley DE, Asomugha CN, Conway PH, et al. Accountable health communities — addressing social needs through medicare and medicaid. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(1):8–11. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Collecting social determinants of health data using PRAPARE to reduce disparities, improve outcomes, and transform care, N.A.o.C.H. Centers , Editor. 2016.

- [38].Estabrooks PA, Boyle M, Emmons KM, et al. Harmonized patient-reported data elements in the electronic health record: supporting meaningful use by primary care action on health behaviors and key psychosocial factors. J Am Med Inf Assoc. 2012;19(4):575–582. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Hasnain-Wynia R, Baker DW. Obtaining data on patient race, ethnicity, and primary language in health care organizations: current challenges and proposed solutions. Health Serv Res. 2006;41(4 Pt 1):1501–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Billioux A,Verlander K, Anthony S, Alley D. Standardized screening for health-related social needs in clinical settings: the accountable health communities screening tool N.A.o. Medicine , Editor. 2017: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- [41].NACHC , PRAPARE - Protocol for responding to and assessing patient assets, risks, and experiences, N.A.o.C.H. Centers , Editor. 2016.

- [42].ALDERWICK H, GOTTLIEB LM. Meanings and misunderstandings: a social determinants of health lexicon for health care systems. Milbank Q. 2019;97(2):407–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Richmond CAM, Ross NA. The determinants of first nation and inuit health: a critical population health approach. Health Place. 2009;15(2):403–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].AMC . Manitoba first nations health & wellness strategy: a 10-year plan for action. Winnipeg, MB: Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Nelson S. Challenging hidden assumptions: colonial norms as determinants of aboriginal mental health. Prince George, BC: National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [46].HHS . Report of the secretary’s task force on black and minority health. Heckler M, Editor. Washington, D.C: US Department of Health & Human Services’ Task Force on Black & Minority Health; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- [48].NIH . Introduction to MeSH. 2018. July 24, 2018 [cited 2018 Nov 15]; Available from: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/introduction.html.

- [49].Mayo NE, Poissant L, Ahmed S, et al. Incorporating the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) into an electronic health record to create indicators of function: proof of concept using the SF-12. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;11(6):514–522. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Pinto AD, Glattstein-Young G, Mohamed A, et al. Building a foundation to reduce health inequities: routine collection of sociodemographic data in primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(3):348–355. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Nguyen OK, Chan CV, Makam A, et al. Envisioning a social-health information exchange as a platform to support a patient-centered medical neighborhood: a feasibility study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(1):60–67. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Ancker JS, Miller MC, Patel V, et al. Sociotechnical challenges to developing technologies for patient access to health information exchange data. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(4):664–670. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Foucher-Urcuyo J, Longworth D, Roizen M, et al. Patient-Entered wellness data and tailored electronic recommendations increase preventive care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30(3):350–361. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Glasgow R, Emmons KM. The public health need for Patient-Reported measures and health behaviors in electronic health records: a policy statement of the Society of Behavioral Bedicine. 201. 1. Behav. Med. Pract. Policy Res. 1, 108-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Glasgow RE, Kaplan RM, Ockene JK, et al. Patient-reported measures of psychosocial issues and health behavior should be added to electronic health records. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(3):497–504. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Bakken S, Yoon S, Suero-Tejeda N. Factors influencing consent for electronic data linkage in urban latinos. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2015;216:984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].NACHC . PRAPARE Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ). Bathesda, MD: National Association of Community Health Centers , Editor. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [58].Pincus T. Electronic multidimensional health assessment questionnaire (eMDHAQ): past, present and future of a proposed single data management system for clinical care, research, quality improvement, and monitoring of long-term outcomes. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016;34(5 Suppl 101): S17–s33. 5 Suppl 101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Archer N, Fevier-Thomas U, Lokker C, McKibbon KA, Straus SE. Personal health records: a scoping review. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association: JAMIA. 2011;18(4):515–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Prey JE, Woollen J, Wilcox L, et al. Patient engagement in the inpatient setting: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(4):742–750. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Lintern G, Motavalli A. Healthcare information systems: the cognitive challenge. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2018;18(1):3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Rhoades ER, Rhoades DA. The public health foundation of health services for American Indians & Alaska Natives. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(Suppl 3):S278–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Allen J, Hopper K, Wexler L, et al. Mapping resilience pathways of Indigenous youth in five circumpolar communities. Transcult Psychiatry. 2014;51(5):601–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Roth C, Foraker RE, Payne PR, et al. Community-level determinants of obesity: harnessing the power of electronic health records for retrospective data analysis. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2014;14(1):36. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Dellinger A 19 million patient records were stolen from Quest Diagnostics and LabCorp. 2019. [cited 2019 Jun 25]; Available from: https://www.engadget.com/2019/06/05/quest-diagnostics-labcorp-amca-data-breach.

- [66].Vaas L “Deeply personal medical” records exposed online. 2019. [cited 2019 Jun 25]; Available from: https://nakedsecurity.sophos.com/2019/06/20/deeply-personal-medical-records-exposed-online/.

- [67].Hawks J Father turns grief over son’s loss into healthtech solution for speedier medical records transfers. 2019. [cited 2019 Jun 25]; Available from: https://www.startlandnews.com/2019/06/chris-jones-matchrite-care/.

- [68].Stanford Medicine. How doctors feel about electronic health records. Stanford, CA: Stanford Medicine, Harris Poll, Editors. 2018. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.