SUMMARY

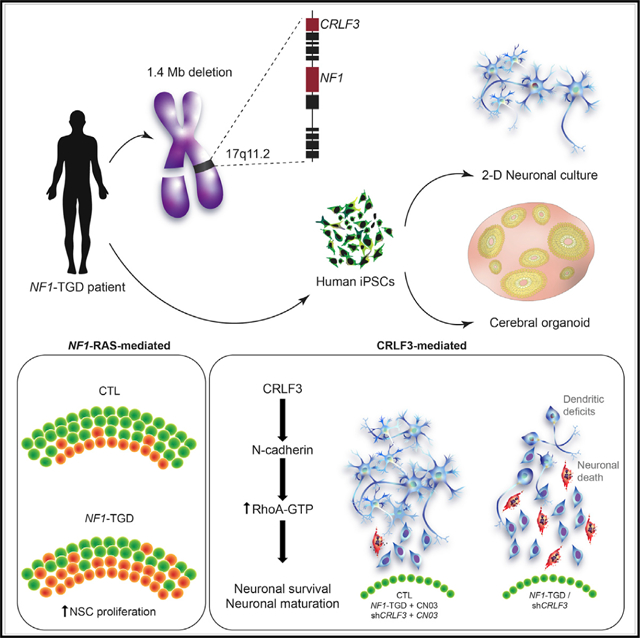

Neurodevelopmental disorders are often caused by chromosomal microdeletions comprising numerous contiguous genes. A subset of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) patients with severe developmental delays and intellectual disability harbors such a microdeletion event on chromosome 17q11.2, involving the NF1 gene and flanking regions (NF1 total gene deletion [NF1-TGD]). Using patient-derived human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC)-forebrain cerebral organoids (hCOs), we identify both neural stem cell (NSC) proliferation and neuronal maturation abnormalities in NF1-TGD hCOs. While increased NSC proliferation results from decreased NF1/RAS regulation, the neuronal differentiation, survival, and maturation defects are caused by reduced cytokine receptor-like factor 3 (CRLF3) expression and impaired RhoA signaling. Furthermore, we demonstrate a higher autistic trait burden in NF1 patients harboring a deleterious germline mutation in the CRLF3 gene (c.1166T>C, p.Leu389Pro). Collectively, these findings identify a causative gene within the NF1-TGD locus responsible for hCO neuronal abnormalities and autism in children with NF1.

Graphical Abstract

In brief

To critically evaluate the impact of NF1 locus genomic microdeletion (17q11.2) on the development of human brain cells, Wegscheid et al. generated patient-derived hiPSC forebrain cerebral organoids (hCOs). Although increased hCO neural stem cell proliferation is RAS-dependent, the neuronal survival, differentiation, and maturation defects resulted from reduced CRLF3-dependent RhoA activation.

INTRODUCTION

Neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) comprise a diverse collection of syndromes in which affected children exhibit autism spectrum symptomatology, cognitive delays, and intellectual disabilities. Genomic sequencing and chromosomal analyses have revealed that many NDDs are associated with chromosomal copy number variations (CNVs) (Coe et al., 2019; Grayton et al., 2012), leading to altered expression of specific genes. As such, microdeletion syndromes have been highly instructive for identifying pathology-causing genes, as well as dissecting the underlying mechanisms responsible for these neurodevelopmental abnormalities (Frega et al., 2019; Pucilowska et al., 2018; Ramocki et al., 2010; Shcheglovitov et al., 2013).

Microdeletions on chromosome 17q11.2 most commonly encompass 1.4 Mb of genomic DNA, including the entire NF1 gene and its flanking regions (type 1 NF1-total gene deletion [NF1-TGD]). These microdeletion events are found in 4.7%–11% of patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) (MIM: 162200) (Kluwe et al., 2004; Rasmussen et al., 1998), where children with NF1-TGD mutations manifest profound developmental delays, intellectual disability (IQ < 70), and an elevated risk of cancer (Descheemaeker et al., 2004; Mautner et al., 2010; Ottenhoff et al., 2020; Pasmant et al., 2010; Venturin et al., 2004). While it is possible that these clinical abnormalities result from the total deletion of one copy of the NF1 gene, the NF1-TGD locus contains 13 other protein-coding and 4 microRNA genes, which could also contribute to these manifestations. To this end, only the deletion of one of these genes, SUZ12, has been previously correlated with the increased cancer incidence in these patients (De Raedt et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2014; Wassef et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2014). In contrast, the underlying molecular etiologies for the neurodevelopmental deficits in this population are unknown.

To define the molecular and cellular cause(s) for the neurodevelopmental abnormalities in patients with 17q11.2 microdeletions, we established human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC)-forebrain cerebral organoid (hCO) models from several NF1 patients with a 1.4-Mb NF1-TGD mutation (TGD hCOs). Leveraging this platform, we identified neuronal survival, differentiation, and maturation abnormalities in the TGD hCOs, which were not observed in hCOs harboring intragenic NF1 mutations or an atypical deletion (aTGD). Using a number of converging strategies, we identified a single gene (CRLF3) and signaling pathway (RhoA activation) responsible for the neuronal maturation defects observed in TGD hCOs. Moreover, we demonstrated a higher autistic trait burden in NF1 patients harboring a deleterious germline mutation in the CRLF3 gene (p.Leu389-Pro). Collectively, these experiments reveal a causative gene and mechanism responsible for the profound neurodevelopmental abnormalities of TGD hCOs.

RESULTS

TGD hCOs have neuronal defects

Using hCOs from three neurologically normal control individuals and three individuals harboring a 1.4-Mb NF1-TGD (Figures 1A and S1A–S1E; Table S1), we first assessed neural stem cell (NSC) proliferation. Similar to hCOs harboring intragenic NF1 patient NF1 gene point mutations (Anastasaki et al., 2020) (Table S1), TGD hCOs also exhibited increased NSC proliferation (% Ki67+ NSCs per hCO ventricular zone [VZ]) at 16 and 35 days in vitro (DIV) (Figures 1B and 1D) and 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) incorporation at 16 DIV (Figure S2A) relative to control hCOs.

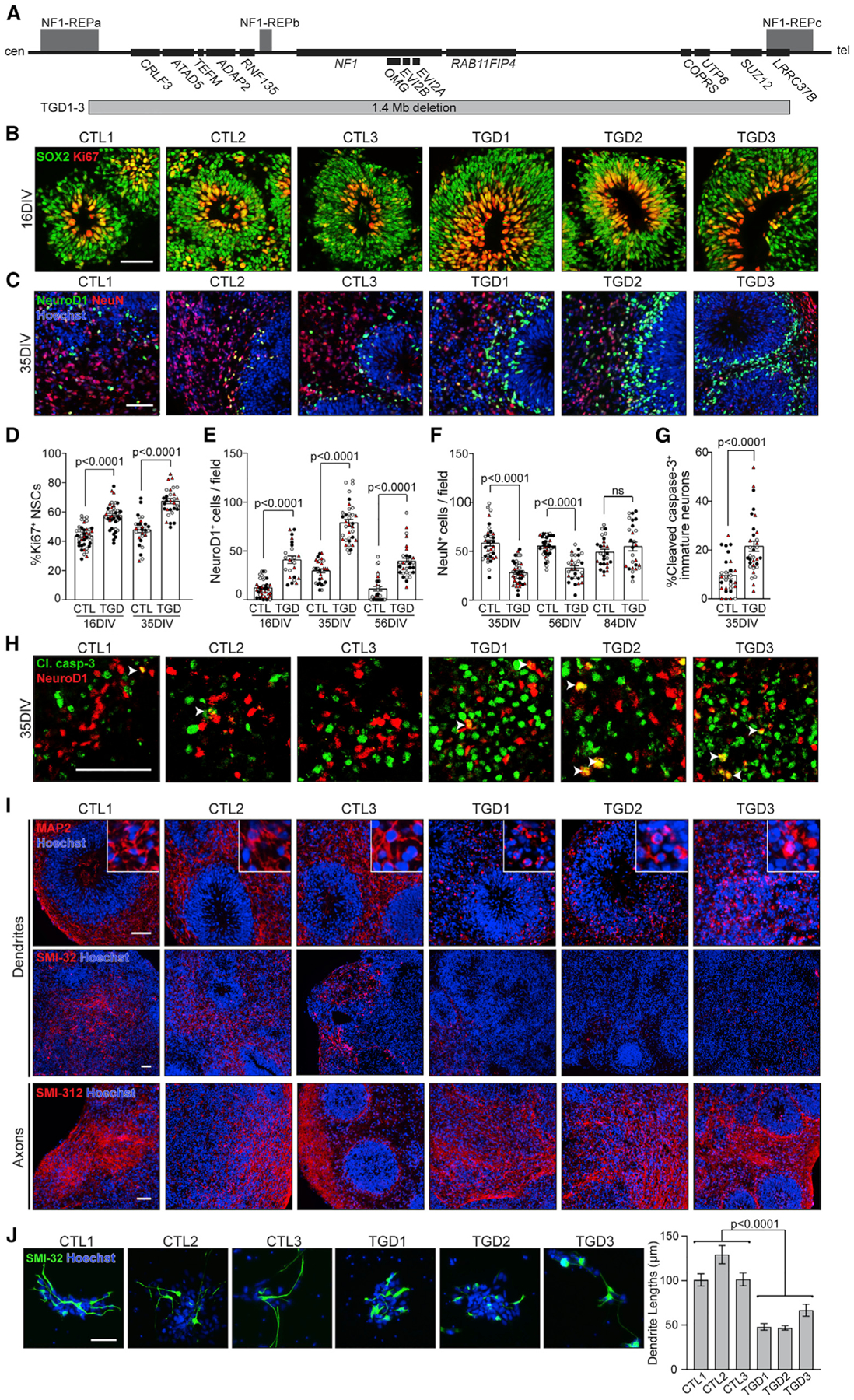

Figure 1. TGD hCOs and neurons exhibit neuronal defects.

(A) Protein-coding genes within the 17q11.2 microdeletion region, denoting the length and location of the 1.4-Mb deletion (adapted from Kehrer-Sawatzki et al. [2017]).

(B and D) Images and quantification of VZ NSC proliferation (Ki67+, red) in control (CTL) and TGD hCOs at 16 and 35 DIV.

(C) Images of 35 DIV hCOs immunolabeled for NeuroD1+ (green) and NeuN+ (red) neuronal markers.

(E and F) Number of (E) NeuroD1+ and (F) NeuN+ neurons per image field in the SVZs of TGD hCOs relative to CTL.

(G) Increased apoptotic immature neurons in TGD hCOs compared to CTL at 35 DIV.

(D–G) Each data point represents 1 hCO, 2–6 hCOs per experimental replicate, and 3–5 experimental replicates per genotype. Independent hiPSC lines representing three different CTL or TGD lines (black, CTL1/ TGD1; white, CTL2/ TGD2; red, CTL3/ TGD3) are shown.

(H) White arrowheads indicate co-localization of NeuroD1+ neurons (red) and cleaved caspase-3 (green) in CTL and TGD hCOs at 35 DIV.

(I) Images of hCOs immunolabeled for dendrites (MAP2+, SMI-32+) and axons (SMI-312+) at 35 DIV.

(J) Images of 2D CTL and TGD neurons immunolabeled for SMI-32, with a graph depicting the mean dendrite lengths per genotype.

Three independent experimental replicates per genotype, 48–112 neurites per replicate. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses by unpaired (D–G) two-tailed t test or (J) one-way ANOVA. Scale bars: (B–I) 50 μm; (J) 100 μm.

Next, to assess the temporal course of neurogenesis in these PAX6+/OTX2+ dorsal telencephalic forebrain hCOs (Figure S1E), cryosections were immunostained for markers of early-stage (NeuroD1+)- and late-stage (NeuN+) immature neurons, as well as deep-layer (TBR1+) and upper-layer (SATB2+) neurons (Figures 1C and S1G–S1F). The TGD hCOs produced increased numbers of NeuroD1+ immature neurons relative to control hCOs from 16 to 56 DIV (Figure 1E), after which time, NeuroD1+ neurons were no longer present. Late-stage immature NeuN+ neurons and deep-layer TBR1+ neurons were first detected at 35 DIV in both control and TGD hCOs; however, the TGD hCOs had reduced numbers of NeuN+ and TBR1+ neurons (Figures 1F and S1G) at 35 and 56 DIV. Despite normalization of NeuN+ neuronal numbers at 84 DIV (Figure 1H) and no microcephalic defects (Figures S1B–S1D), the TGD hCOs had reduced numbers of upper-layer SABT2+ neurons at 84 DIV (Figure S1H), demonstrating a persistent imbalance in the neuronal subtypes generated. This impaired neuronal differentiation was unique to the TGD hCOs, as it was not observed in hCOs harboring five distinct intragenic NF1 gene mutations (Table S1; Figure S2B).

As the increased numbers of early-stage immature neurons in the TGD hCOs did not generate a compensatory increase in late-stage immature neurons, we hypothesized that the TGD NeuroD1+ neurons were being eliminated by programmed cell death. To measure apoptosis, 35 and 56 DIV hCOs were immunolabeled for the early-stage (cleaved caspase-3) and late-stage (TUNEL) apoptotic markers, respectively. Greater caspase-3 cleavage (11.8% increase; Figures 1G and 1H) and DNA fragmentation (6.3% TUNEL increase; Figure S2C) were observed in the TGD NeuroD1+ neurons relative to controls, establishing a concurrent increase in production and apoptosis of early-stage immature neurons in TGD hCOs. The increased apoptosis of NeuroD1+ neurons in TGD hCOs, coupled with differentiation of the remaining NeuroD1+ neurons in TGD hCOs at 56 DIV, accounts for normalization of late-stage immature neurons at 84 DIV.

The finding of neuronal differentiation defects in the TGD hCOs prompted us to determine whether there were also defects in dendrite and axonal extension, as reported in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and intellectual disability (Hutsler and Zhang, 2010; Lazar et al., 2014; Mukaetova-Ladinska et al., 2004; Wolff et al., 2012). While the TGD hCOs produced normal SMI-312+ axonal projections, they had reduced MAP2+ and SMI-32+ dendrites in hCOs from 35 to 84 DIV (Figures 1I, S1F, S2D, and S2E), abnormalities not observed in hCOs harboring intragenic NF1 mutations (Figure S2F). Similar to TGD hCOs, hiPSC-derived neurons in 2D cultures also exhibited reduced MAP2+ and SMI-32+ dendrites (Figure 1J)

Taken together, these results reveal that TGD hCOs and hCOs harboring intragenic NF1 mutations have increased NSC proliferation, reflecting impaired NF1 gene function, but additionally exhibit neuronal abnormalities (dendritic maturation) unique to TGD hCOs.

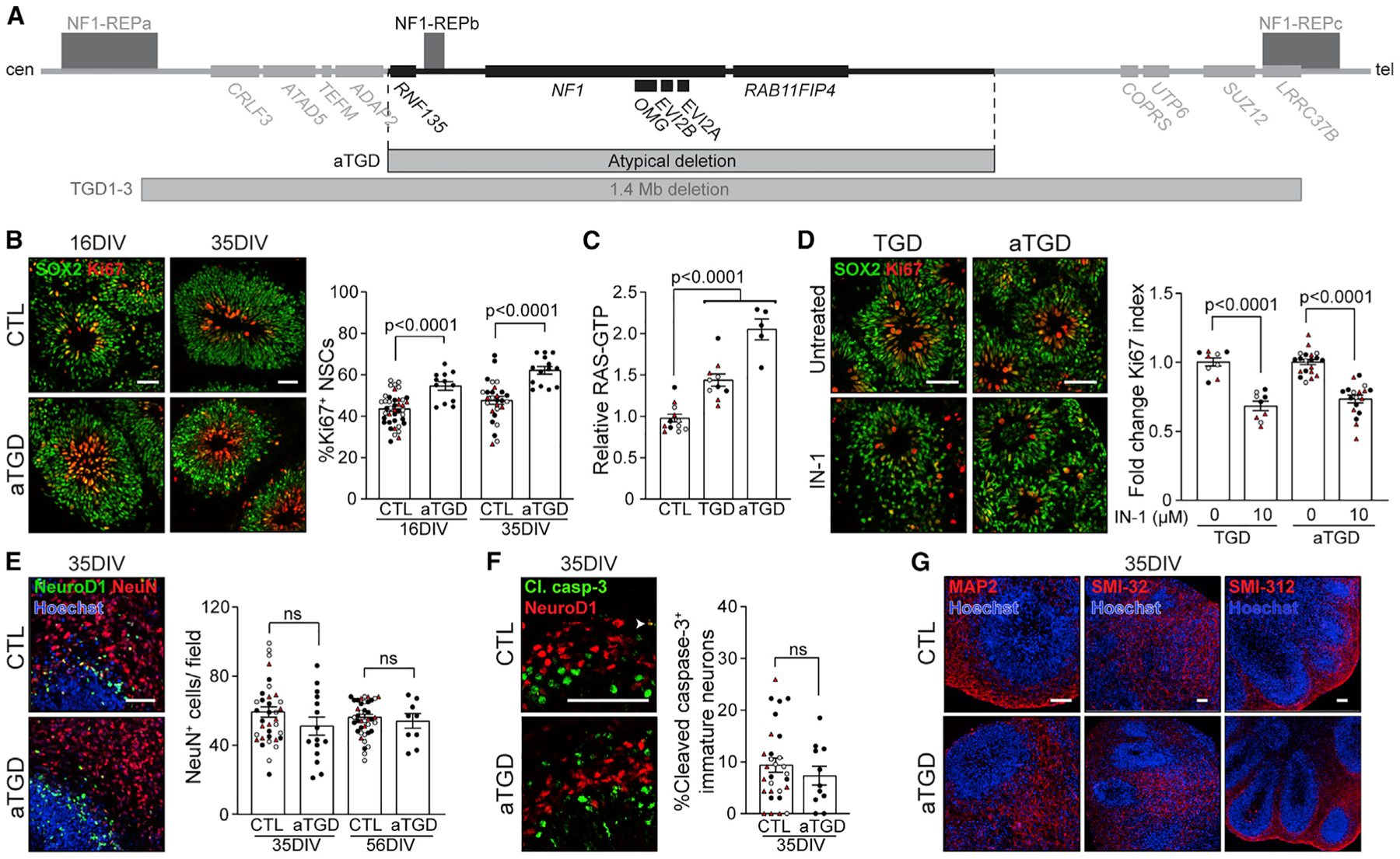

NSC hyperproliferation in TGD hCOs is RAS-dependent

To further explore the impact of complete NF1 deletion on NSC proliferation in the absence of other genetic contributors, we generated hCOs from the single available patient-derived hiPSC line harboring a rare atypical (0.6–0.9 Mb) deletion (aTGD), involving the loss of six protein-coding genes, including NF1, but not the eight protein-coding genes deleted in the common 1.4-Mb NF1-TGD (Figure 2A). Similar to the TGD and intragenic NF1 mutant hCOs (Anastasaki et al., 2020), the aTGD hCOs had increased NSC proliferation (%Ki67+ NSCs; Figure 2B) relative to controls. Since the NF1 protein (neurofibromin) has previously been shown to mediate increased cell proliferation through RAS regulation in numerous NF1-mutant cell types (Chen et al., 2015; Hegedus et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2010; Sanchez-Ortiz et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2012), we hypothesized that the increased NSC proliferation observed in the NF1-mutant hCOs was RAS dependent. Similar to the intragenic NF1-mutant hCOs (Anastasaki et al., 2020), TGD and aTGD hCOs had increased RAS activity (1.4- and 2.1-fold, respectively) relative to controls (Figure 2C). To investigate the relationship between RAS hyperactivation and increased NSC proliferation in the NF1-mutant hCOs, we incubated control, TGD, and aTGD hCOs with an experimentally determined concentration of the pan-RAS inhibitor IN-1(IN-1) for 48 h (Figures S3A–S3C). While IN-1 had no effect on NSC proliferation in control hCOs (Figure S3D) or neuronal differentiation and dendrite maturation in TGD and aTGD hCOs (Figures S3E–S3F), it reduced the NSC hyperproliferation in TGD and aTGD hCOs (Figure 2D), confirming that RAS hyperactivation is solely responsible for the increased NSC proliferation observed in NF1-mutant hCOs.

Figure 2. RAS hyperactivation drives the increased NSC proliferation in TGD hCOs.

(A) Diagram illustrating the 1.4-Mb (TGD) and atypical (aTGD) microdeletions, highlighting their commonly deleted region.

(B) Images and quantification of NSC (SOX2+) proliferation (Ki67+) in CTL and aTGD hCOs at 16 and 35 DIV.

(C) TGD and aTGD hCOs have increased RAS activity relative to CTL hCOs at 16 DIV. Each data point represents an independent experimental replicate consisting of 4 pooled hCOs.

(D) Images and quantification of NSC proliferation (fold change in %Ki67+ NSCs) in three clones of TGD and aTGD hCOs at 16 DIV with or without IN-1 treatment.

(E–G) Images and quantification of CTL and aTGD hCOs showing normal (E) production of NeuN+ neurons at 35 and 56 DIV, (F) early-stage immature neuron apoptosis, and (G) production of dendrites (MAP2+, SMI-32+) and axons (SMI-312+) at 35 DIV.

(B and D–F) Each data point represents 1 hCO, 2–6 hCOs per experimental replicate, 3–5 experimental replicates per genotype. Independent hiPSC lines representing three different CTL or aTGD lines (black, CTL1/ aTGD1; white, CTL2/ aTGD2; red, CTL3/ aTGD3) are shown. All data are shown as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple-comparisons test or unpaired, two-tailed t test. Scale bars: 50 μm.

TGD hCOs have reduced CRLF3 expression

In striking contrast to the TGD hCOs, the aTGD hCOs lacked neuronal survival, differentiation, and maturation abnormalities. In this regard, the aTGD hCOs produced normal numbers of late-stage immature neurons (Figure 2E), exhibited no increase in immature neuron apoptosis (Figure 2F), and had normal dendrites (Figure 2G) relative to controls. These observations demonstrate that genes outside of the atypical deletion region are responsible for the neuronal differentiation and maturation defects observed in the TGD hCOs.

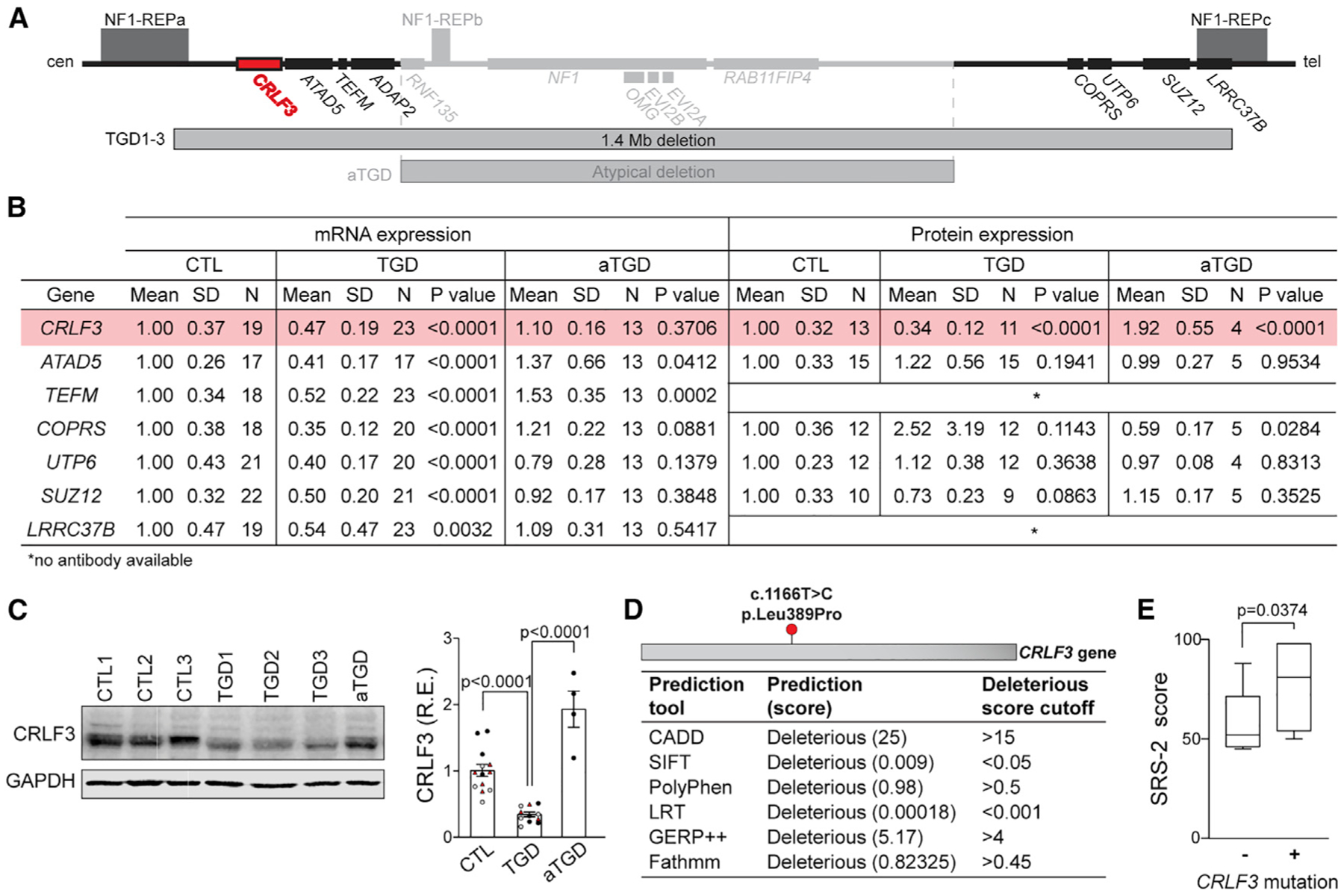

To identify the responsible gene(s), we conducted a systematic analysis of the genes contained within the 1.4-Mb deletion region, but not in the atypical deletion region (Figure 3A). First, the deletion status of two genes in the aTGD hCOs (COPRS and RAB11FIP4) was assayed by quantitative real-time PCR (Figures 3B and S3G), revealing reduced expression of RAB11-FIP4 (within the aTGD region), but not COPRS (outside the aTGD region). Next, we excluded the three microRNA genes that exhibited highly variable mRNA expression (Figure S3H), as well as one protein-coding gene (ADAP2) and one microRNA gene (MIR4733), which were not expressed in control hCOs. We then analyzed the differential gene expression of the seven remaining protein-coding genes at an experimentally determined time point where the highest levels of mRNA expression were detected in control hCOs (Figure S3I).

Figure 3. CRLF3 is uniquely disrupted in TGD hCOs and NF1 patients with increased SRS-2 scores.

(A) 17q11.2 region highlighting the loci uniquely deleted in TGD microdeletions and the CRLF3 gene (red).

(B) mRNA and protein expression analysis at 56 DIV of protein-coding genes uniquely deleted in TGD hCOs. Each mRNA data point represents 1 hCO, 3 hCOs per experimental replicate. Each protein data point represents an independent replicate consisting of 4 pooled hCOs.

(C) Western blot and quantification demonstrating reduced CRLF3 protein levels in TGD relative to CTL and aTGD 56 DIV hCOs. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM. Independent hiPSC lines representing 3 different CTL or TGD lines (black, CTL1/ TGD1; white, CTL2/ TGD2; red, CTL3/ TGD3) are shown.

(D) Position of the deleterious CRLF3 c.1166T>C mutation found in 7/17 NF1 patients, with mutational effect predictions using six methods.

(E) NF1 patients with the CRLF3 c.1166T>C mutation (n = 7) have higher SRS-2 scores than those without it (n = 10). Boxplot indicates median (central line), interquartile range (box), and minimum and maximum values (whiskers).

(C and E) Statistical analysis by unpaired, two-tailed t test.

All seven genes had reduced mRNA expression in the TGD hCOs relative to controls (Figure 3B). However, cytokine receptor-like factor 3 (CRLF3) was the only gene with reduced protein levels in the TGD hCOs relative to the aTGD and control hCOs (82% and 66%, respectively) (Figures 3B, 3C, and S3J–S3N), implicating CRLF3 in the neuronal defects observed only in TGD hCOs.

CRLF3 mutation is associated with increased autism trait burden in patients with NF1

To further investigate CRLF3 as a potential gene involved in neurodevelopment, we evaluated CRLF3 mutation status in a previously assembled cohort of individuals with NF1 from the Washington University NF Center. We specifically chose patients who underwent Social Responsiveness Scale, Second Edition (SRS-2) testing as part of routine NF1 clinical screening, had DNA banked under an approved Human Studies protocol (Constantino et al., 2015), and were between the ages of 10 and 19, based on the World Health Organization definition of adolescence (World Health Organization, 2017) and previously described age-dependent differences in autistic trait burden in children, adolescents, and adults with NF1 (Morris et al., 2016). After excluding patients with CNVs (n = 1), 17 patients were analyzed (Table S2).

Genomic DNA was whole-exome sequenced (WES) to identify genetic variants, which were prioritized according to their annotated impact (STAR Methods). A single deleterious CRLF3 missense mutation (c.1166T>C, p.Leu389Pro) affecting a highly conserved amino acid within the CRLF3 protein (Figure S4A) was identified in 7/17 of the NF1 patients (Figure 3D). Grouping of patients by CRLF3 c.1166T>C mutation status revealed higher SRS-2 scores in NF1 patients with this mutation than in those without it (p = 0.0374) (Figure 3E). The neuronal differentiation, survival, and maturation abnormalities in TGD hCOs harboring a heterozygous CRLF3 deletion, coupled with the observed increase in autistic trait burden in patients harboring a deleterious mutation in the CRLF3 gene, suggests an essential role for CRLF3 in human brain development. This notion is further supported by the high amino acid sequence conservation of CRLF3 across vertebrates (Hahn et al., 2017, 2019; Ostrowski and Heinrich, 2018) and enriched CRLF3 expression found in human embryonic brain tissues (Yang et al., 2009) (Figure S4B).

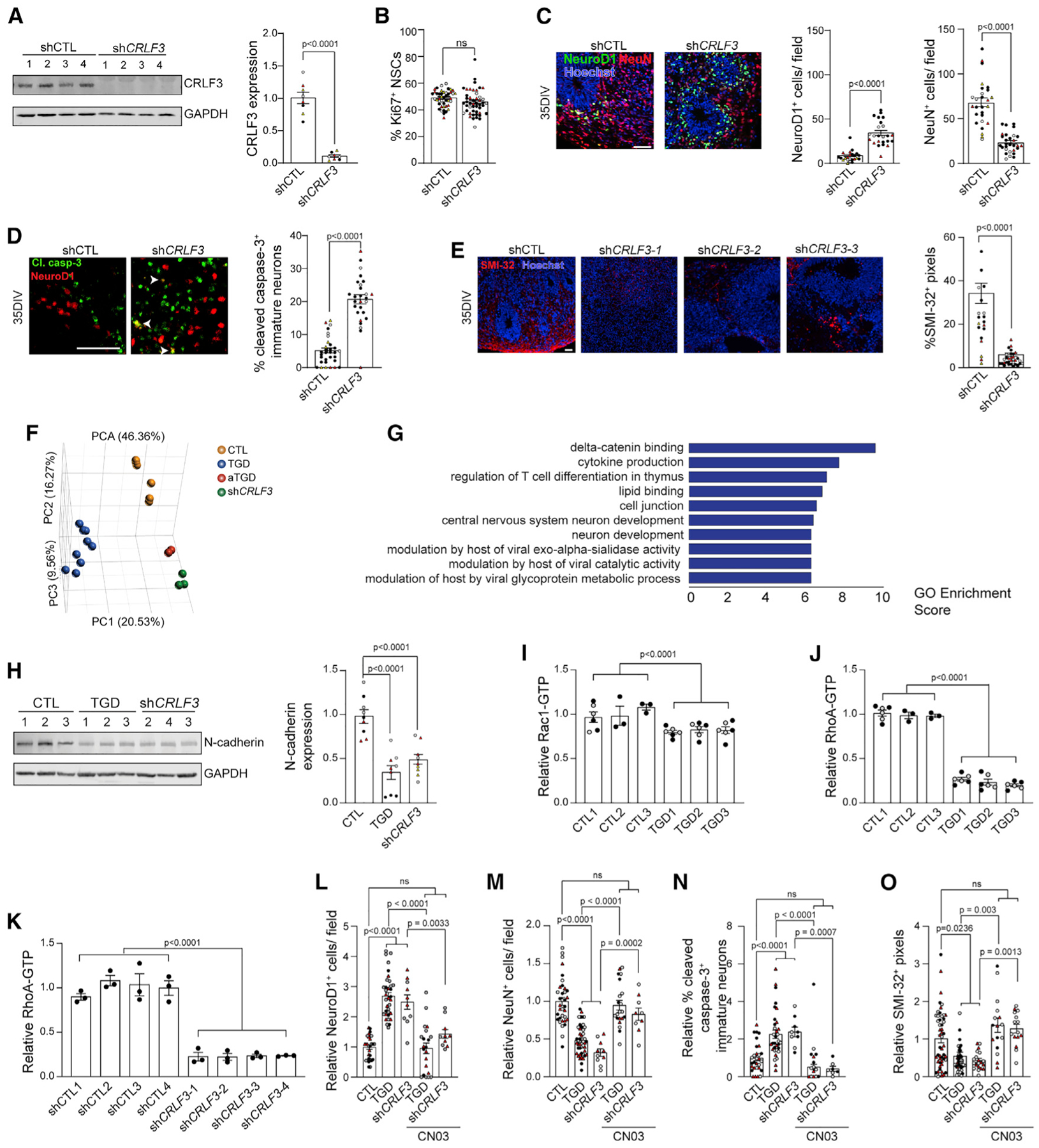

CRLF3 reduction recapitulates the TGD neuronal defects

To determine whether reduced CRLF3 expression was responsible for the neuronal maturation defects observed in TGD hCOs, control hiPSCs were infected with four unique CRLF3 (shCRLF3) and four unique control (shCTL) short hairpin RNA constructs. All four shCRLF3 constructs had reduced CRLF3 expression relative to shCTLs (Figures 4A and S4C). While CRLF3 reduction had no effect on NSC proliferation (Figure 4B) or neurofibromin protein expression and subcellular localization (Figures S4D–S4F), it fully replicated the neuronal abnormalities observed in the TGD hCOs. In this regard, shCRLF3 hCOs had increased numbers of early-stage immature neurons at 16 DIV, reduced numbers of late-stage immature neurons at 35 DIV (Figure 4C), increased immature neuron apoptosis (Figure 4D), and reduced SMI-32+ dendrites (Figure 4E) and SATB2+ upper layer neurons (Figure S4G) compared to shCTL hCOs. These results demonstrate that reduced CRLF3 expression is sufficient to produce the TGD neurogenic abnormalities, establishing CRLF3 as a key regulator of human neuron differentiation, survival, and maturation.

Figure 4. Impaired RhoA signaling drives CRLF3-mediated neuronal defects.

(A)Western blot showing reduced CRLF3 protein levels in CTL1 hiPSCs infected with shCRLF3 constructs relative to shCTL.

(B) NSC proliferation (%Ki67+ NSCs) in 16 DIV hCOs from shCTL and shCRLF3 lines.

(C–E) Images and quantification of shCTL and shCRLF3 hCOs showing (C) increased production of NeuroD1+ (green) neurons and reduced NeuN+ (red) neurons, (D) increased apoptotic (Cl. casp-3, green) immature (NeuroD1, red) neurons, and (E) reduced SMI-32+ dendrites in shCRLF3 compared to shCTL hCOs. Each data point represents 1 hCO, 3–10 hCOs per hiPSC line. Statistical analysis by unpaired, two-tailed t test.

(F) Principal component analysis showing distinct transcriptional profiles in CTL, TGD, aTGD, and shCRLF3 NSCs.

(G) Enrichment scores of the top 10 gene ontologies (p value ≤ 0.01) in shCRLF3 and TGD relative to CTL and aTGD NSCs.

(H) Western blot and quantification of N-cadherin protein levels in CTL, TGD, and shCRLF3 NSCs. n = 3 biological replicates per genotype. Statistical analysis by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple-comparisons test.

(I–K) Rac1 (I) and RhoA (J and K) activity levels in CTL and TGD (J) or shCTL and shCRLF3 (K) NSCs. Each data point represents an independently generated biological replicate, 3 biological replicates per genotype. Statistical analysis by unpaired, two-tailed t test.

(L–O) Quantitation of (L) NeuroD1+ neurons, (M) NeuN+ neurons, (N) cl. Caspase-3+ apoptotic immature neurons, and (O) SMI-32+ immunopositive dendrites in 35 DIV TGD and shCRLF3 hCOs with and without CN03 treatment relative to control hCOs. Data are represented as fold-change relative to controls. Each data point represents 1 hCO, 2–6 hCOs per experimental replicate, and 3–5 experimental replicates per genotype.

(A–O) All data are shown as the mean ± SEM. Independent hiPSC lines representing (A–D) four different shCTL or shCRLF3 lines (black, shCTL1/shCRLF3-1; white, shCTL2/shCRLF3-2; red, shCTL3/shCRLF3-3; yellow, shCTL4/shCRLF3-4), (H and L–O) three different CTL, TGD, or shCRLF3 lines (black, CTL1/TGD1/shCRLF3-1; white, CTL2/TGD2/shCRLF3-2; red, CTL3/TGD3/shCRLF3-3), or (I and J) two different clones for each line (black, clone 1; gray, clone 2) are shown. Scale bars: 50 μm.

CRLF3-mediated dendritic defects result from impaired RhoA activation

To gain mechanistic insights into CRLF3-mediated signaling in human brain cells, we performed RNA sequencing on CTL, TGD, shCRLF3, and aTGD NSCs (Figures 4F, 4G, and S4H). First, we identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (p values, false discover rates [FDRs] ≤ 0.01; log-fold changes ≥ ±5) in TGD NSCs relative to CTL and aTGD NSCs. This DEG list was filtered for non-significant genes in the comparison of TGD and shCRLF3 NSCs (Table S3). Subsequent gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis demonstrated δ-catenin binding as the most highly enriched GO term (Figure 4G). Notably, dysregulation of δ-catenin signaling has been implicated in autism (Turner et al., 2015), dendritic spine morphogenesis, maintenance, and function during development (Arikkath et al., 2009; Matter et al., 2009) through regulation of N-cadherin levels (Fukata and Kaibuchi, 2001; Tan et al., 2010) and activation of Rho-family GTPases, RhoA, and Rac1 (Arikkath et al., 2009; Elia et al., 2006; Gilbert and Man, 2016). To determine whether CRLF3 regulates this pathway in cells and tissues harboring a TGD, we measured N-cadherin protein levels, as well as Rac1 and RhoA activation in CTL, TGD, and shCRLF3 NSCs (Figures 4H–4K and S4I–S4K). Consistent with this proposed mechanism, TGD and shCRLF3 NSCs had reduced N-cadherin levels (TGD, 65% reduction; shCRLF3, 52% reduction; Figures 4H and S4G), decreased Rac1 activation (TGD, 18.5% reduction; Figure 4I; shCRLF3, 13.1% reduction; Figure S4I), and decreased RhoA activation (TGD, 76.6% reduction; Figure 4J; shCRLF3, 77.1% reduction; Figure 4K) relative to controls. Moreover, treatment of TGD and shCRLF3 hCOs with an experimentally determined concentration of the RhoA activator CN03 (Figure S4K) rescued the neuron maturation defect (TGD, 35.8% reduction in NeuroD1, 1.9-fold increase in NeuN; Figure 4J; shCRLF3, 57.7% reduction in NeuroD1, 2.6-fold increase in NeuN; Figures 4L, 4M, and S4L), neuronal apoptosis (TGD, 23% reduction; shCRLF3, 17.6% reduction in Cl. Caspase-3; Figures 4N and S4M), and dendrite maturation defect (TGD, 2.5-fold increase; shCRLF3, 2.6-fold increase in SMI-32 immunopositivity; Figures 4O and S4N), normalizing them to control levels in 35 DIV hCOs. These results establish reduced RhoA signaling as the etiologic mechanism responsible for the impaired neuron maturation and neurite outgrowth in TGD hCOs.

DISCUSSION

The successful deployment of the hCO platform to identify the cellular and molecular etiologies for human 17q11.2 microdeletion-related neurodevelopmental abnormalities raises several important points. First, it adds CRLF3 to the growing list of genes contained within the NF1-TGD locus that could contribute to specific clinical phenotypes observed not only in patients with NF1, but also in the general population. For example, mutations in RNF135 have been reported in patients with autism (Tastet et al., 2015) and in families with dysmorphic facial features and learning disabilities (Douglas et al., 2007). Biallelic loss of SUZ12 is frequently observed in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs) (Lee et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014), while ADAP2 is required for normal cardiac morphogenesis (Venturin et al., 2014) relevant to cardiovascular malformations observed in 17q11.2 microdeletion patients (Venturin et al., 2004). Further investigation into the roles of other deleted genes within this interval may provide insights relevant to the diagnosis and treatment of human disease. Second, using a combination of lentiviral CRLF3 genetic silencing and pharmacologic rescue of RhoA activity experiments (CN03 treatments), we establish that CRLF3 regulates human neurogenesis, neuron survival, and dendritic development through RhoA activation, extending prior studies on the role of RhoA signaling in murine neuron maturation relevant to neurodevelopment and cognition (Richter et al., 2019). Third, the provocative early-phase clinical analyses suggest that CRLF3 mutation might identify a high-risk group of NF1 patients more likely to harbor an increased autism trait burden. While CRLF3 has not been previously implicated as an autism risk gene (Abrahams et al., 2013; Banerjee-Basu and Packer, 2010), it constitutes a potential therapeutic target and a risk assessment tool in future studies involving larger numbers of individuals, with a focus on its sensitivity and specificity for predicting ASD symptomatology in children with NF1.

Limitations of the study

While we show that CRLF3 reduction accounts for the impaired neuronal maturation and dendritic outgrowth in NF1-TGD hCOs, further work will be required to establish a link between NF1-TGD dendritic dysfunction and autism. Additionally, analysis of an in vivo model would be required to validate the translatability of these results. Similarly, as aTGD mutations are quite rare, additional studies should focus on the neuronal function in this subset of TGD patients. Last, with the availability of reliable antibodies that recognize the proteins encoded by other genes in the microdeletion locus and CRLF3 expression constructs, future studies could explore the relationship between these deleted genes and brain development.

STAR⋆METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Dr. David H. Gutmann (gutmannd@wustl.edu).

Materials availability

hiPSC lines generated for this study are available upon request to Dr. David H. Gutmann.

Data and code availability

This study did not generate any codes. The whole exome sequencing data are available under accession number PRJNA698597 (SRA database). The RNA sequencing data are available in the GEO repository (GSE166080). Any other relevant data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Human induced pluripotent stem cells

Patient-derived hiPSC lines were reprogrammed by the Washington University Genome Engineering and iPSC Core Facility (GEiC) using biospecimens (skin, blood, urine) acquired from three individuals harboring a 1.4 Mb NF1-total gene deletion (TGD) and one patient harboring an atypical TGD (aTGD) (Table S1) with an established diagnosis of NF1 under an approved Human Studies Protocol at Washington University. As atypical TGD mutations are rare in the NF1 population (Messiaen et al., 2011), no additional patients with this genomic alteration were available to generate hiPSC lines. Briefly, fibroblasts, renal cells or peripheral blood cells were infected with a Sendai virus carrying four stem cell reprogramming factors (OCT4, KLF4, SOX2, C-MYC), as previously reported (Anastasaki et al., 2015, 2020). hiPSC colonies were isolated and pluripotency was confirmed by morphological assessment and expression of stem cell markers (Figure S1A). Two to three different clones were expanded for each line, tested and verified negative for Mycoplasma contamination, and used to generate human cerebral organoids (hCOs) (Figures S1B–S1E), neural progenitor cells (NSCs) (Figure S4E) and neurons. The sizes of the NF1 locus deletions were determined by MLPA assay (MRC Holland) at the Medical Genomics Laboratory (University of Alabama, Birmingham). Single clones of two patient-derived neurologically normal controls were provided by Drs. Matthew B. Harms (CTL2, male) and Fumihiko Urano (CTL3, male) at Washington University. Five distinct isogenic human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC) lines harboring NF1 patient germline NF1 gene mutations (Transcript ID NM_000267; c.1149C > A, c.1185+1G > A, c.3431–32_dupGT, c.5425C > T, c.6619C > T) were individually engineered into a single commercially available male control human iPSC line (BJFF.6, CTL1) as previously described (Anastasaki et al., 2020) (Table S1). All hiPSC lines generated by CRISPR/Cas9 engineering were subjected to subcloning and Illumina deep sequencing to verify the presence of the introduced mutation. These renewable resources are continuously frozen at low passage (< 5). All hiPSC clones were used for analysis and relative to prior frozen aliquots of the same clone to ensure reproducibility. hiPSCs have been authenticated by (a) routine testing for Mycoplasma infection, (b) regular quality control checks for pluripotency by monitoring expression of pluripotency markers, and (c) competence to undergo multi-lineage differentiation.

Human subject details

Samples for exome sequencing were acquired from a previously assembled cohort of individuals with NF1 from Washington University Neurofibromatosis Center whose DNA was banked under a Human Studies protocol approved by the Washington University Human Research Protection Office (Constantino et al., 2015). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Patients with copy number variants (CNVs) (n = 1) were excluded. Of the patients between 10 and 19 years of age with clinically indicated SRS-2 testing, 11 were male (64.7%) and 6 were female (35.3%). Selected individuals ranged in age from 10 to 18 years (median, 13 years), with SRS-2 T scores from 45 to 98 (Table S2). There was no significant difference between males (n = 11) and females (n = 6) with respect to SRS-2 scores, between males (n = 5) and females (n = 2) in the group with a deleterious p.Leu389Pro CRLF3 mutation (n = 7), or between males (n = 6) and females (n = 4) without a CRLF3 mutation (n = 10).

METHOD DETAILS

Human iPSC, cerebral organoid, NSC and 2D neuron cultures

hiPSCs were cultured on Matrigel (Corning)-coated culture flasks and were fed daily with mTeSR Plus (05825, STEMCELL Technologies). hiPSCs were passaged with ReLeSR (05873, STEMCELL technologies) following manufacturer’s instructions. hCOs were generated as previously described (Anastasaki et al., 2020). Briefly, cerebral organoids were cultured from hiPSCs by first aggregating 40,000 hiPSCs per well of an ultra-low binding 96-well U-bottom plate (Corning) to allow for embryoid body (EB) formation. EBs were fed every other day with STEMdiff Neural Induction Medium (05835, STEMCELL technologies) supplemented with low concentration bFGF (4ng/mL; 100-18B, PeproTech) and ROCK inhibitor (20 μM; Y27632, Millipore) for the first 6 days, followed by NIM minus bFGF and ROCK inhibitor for an additional 3 days. Tissues were then transferred to Corning Costar 24 Well Clear Flat Bottom Ultra Low Attachment plates (1 organoid per well) in hCO differentiation medium (125 mL DMEM-F12, 125 mL Neurobasal medium, 1.25 mL N2 supplement, 62.5 μl insulin, 2.5 mL GlutaMAX supplement, 1.25 mL MEM-NEAA, 2.5 mL B27 supplement, 2.5 mL penicillin-streptomycin, 87.5μl of a 1:100 dilution of 2-mercaptoethanol in DMEM-F12) on an orbital shaker rotating at 80 rpm. hCO differentiation media was changed every 3 days. hCOs were maintained for up to 84DIV. Neural progenitor cells (NSCs) were generated using previously described methods (Anastasaki et al., 2020). For non-specific neuronal differentiation, NSCs were cultured in PLO/Laminin-coated plates in neuronal differentiation media (490 mL Neurobasal media, 5 mL N2 supplement, 5 mL MEM-NEAA) supplemented with 0.01 μg/ml BDNF (450-02, PeproTech), IGF-I (100-11, PeproTech), GDNF (78058, STEMCELL technologies), cAMP (1μM; 1698950, PeproTech), and Compound E (0.2 μM; 73954, STEMCELL technologies) for 7 days.

Whole exome sequencing

Genomic DNA samples were whole exome sequenced (Otogenetics Ltd), and FASTQ files aligned to the human reference genome assembly (GRCh37/hg19) using Samtools 1.4.1 software. Sequence variants of CRLF3 were called, filtered, and prioritized according to their impact annotation obtained from SnpEff. Pathogenicity of resulting variants was additionally confirmed using CADD, SIFT, PolyPhen, likelihood ratio test (LRT), GERP++, and Fathmm.

Next generation RNA sequencing and analysis

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) was performed on CTL1, CTL2, TGD1, TGD2, TGD3, aTGD and shCRLF3-1 NSCs as previously described (Anastasaki et al., 2020). Sequencing analyses were generated using Partek Flow software, version 9.0.20 (Partek Inc, 2020). RNA-seq reads were aligned to the Ensembl transcripts release 100 top-level assembly with STAR version 2.7.3a (Dobin et al., 2013). Gene counts and isoform expression were derived from Ensembl output. Sequencing performance was assessed for the total number of aligned reads, total number of uniquely aligned reads, and features detected. Normalization size factors were calculated for all gene counts by median ratio. Differential genetic analysis was then performed using DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014) to analyze for differences between conditions. Results for TGD samples compared separately with CTLs and aTGD samples were filtered for only those genes with P values and false discovery rates (FDR) ≤ 0.01 and log fold-changes ≥ ± 5. This gene list was then filtered further for only non-significant genes in the comparison of TGD samples versus shCRLF3 samples. This resulted in a gene list of 31 genes (Table S3). Gene Ontology enrichment (Ashburner et al., 2000) was run on the resulting gene list. Deep sequencing data is in the process of being submitted to GEO.

Immunohistochemistry

hCOs were fixed, embedded and cryosectioned at 12 μm as previously described (Sloan et al., 2018). Tissues were permeabilized in 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 minutes. After three PBS washes, tissues were blocked in a solution of 10% goat serum (GS) in PBS for one hour at room temperature, then immunolabeled with primary antibodies, diluted in a solution of 2% GS, overnight at 4°C. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-SOX2 (1:400, 4900, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-SOX2 (1:200, ab92494, Abcam), anti-OCT4A (1:400, 2840, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-NANOG (1:800, 3580, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-SMI-32 (2.5 μg/mL, 801701, Biolegend), anti-SMI-312 (2.5 μg/mL, 837904, Biolegend), anti-NeuroD1 (1:250, ab205300, Abcam), anti-NeuroD1 (1:500, ab60704, Abcam), anti-NeuN (1:500, MAB377, Millipore), anti-Ki67 (1:100, BD556003, BD Biosciences), anti-MAP2 (1:500, ab11267, Abcam), anti-cleaved caspase-3 (1:250, 9664, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-active caspase-3 (1:100, AF835, R&D systems), anti-PAX6 (1:250, ab19504, Abcam), anti-OTX2 (1:200, MA5-15854, Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-EN1 (1:50, PA5-14149, Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-GBX2 (1:50, LS-C197281, Lifespan Biosciences), anti-TBR1 (1:200, ab31940, Abcam), anti-SATB2 (1:100, ab51502, Abcam), anti-Vimentin (1:100, 5741, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-Nestin (1:250, ab92391, Abcam). The following day, slides were washed three times with PBS and labeled with relevant secondary antibodies [AlexaFluor488/568 (1:200, Invitrogen)] for one hour at room temperature. Hoechst (1:5000 in PBS) was used for cell nucleus staining. For EdU pulse-chase analyses, 16DIV hCOs were incubated with 10 μM EdU for 1.5 hours. EdU staining was performed using Click-IT EdU Alexa Fluor 488 Imaging Kit (C10337, Invitrogen). TUNEL assays were performed using In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, Fluorescein (11684795910, Roche). All imaging was done on a Leica fluorescent microscope (Leica DMi8) using Leica Application Suite X software for initial processing. Cell counter plugin of ImageJ was used to quantify cells in images of immunolabeled hCOs.

RAS, Rac1, and RhoA activity assays

For small molecule treatments, 14DIV hCOs were incubated with 10 μM Pan-RAS-IN-1 (HY-101295, MedChemExpress) for 48 hours, and RAS activity (STA-440, Cell Biolabs) was determined on liquid nitrogen snap frozen specimens according to the manufacturer’s instructions. NSCs or 8DIV EBs were treated for 24h with 1 μg/ml Rho Activator II (CN-03; Cytoskeleton; CN03) to induce Rho activation. RhoA (BK124, Cytoskeleton) and Rac1 (BK128, Cytoskeleton) activity assays were performed on liquid nitrogen snap frozen NSC and hCO specimens, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted (RNeasy Mini Kit, QIAGEN) from hiPSC-derived hCOs according to manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentrations and purity were assessed using a NanoDrop 2000 Spectrophotometer prior to reverse transcription using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (4374966, Applied Biosystems). RT-qPCR was performed using TaqMan gene expression assays [CRLF3 (Hs00367579_m1), ATAD5 (Hs00227495_m1), TEFM (Hs00895248_m1), ADAP2 (Hs01106939_m1), COPRS (Hs0104 7650_m1), UTP6 (Hs00251161_m1), SUZ12 (Hs00248742_m1), LRRC37B (Hs03045845_m1), MIR193A (Hs04273253_s1), MIR365B (Hs04231549_s1), MIR4725 (Hs06637953_s1), MIR4733 (Hs04274676_s1)] and TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix, no UNG (4444964, Applied Biosystems) according to manufacturer’s instructions. All reactions were performed using the Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time PCR system equipped with Bio-Rad CFX Manager 3.1 software. Gene expression levels of technical replicates were estimated by ΔΔCt method using GAPDH (Hs02786624_g1) as a reference gene.

Western blot analysis

hCO, NSC and iPSC samples were collected, sonicated in RIPA buffer (89900, Thermo Scientific) containing 2 μg/mL aprotinin (ab146286, Abcam), 10 μg/mL leupeptin (L2884, Sigma-Aldrich), and 1 mM PMSF (10837091001, Sigma-Aldrich), and total protein concentrations determined (Pierce BCA protein assay kit, 23225, Thermo Scientific). Reducing Laemmli buffer (1610747, Bio-Rad) was added and samples incubate at 95°C for 5 minutes. Equal amounts of protein (30 to 45 μg) were loaded into each well of 8% or 10% SDS-PAGE gels and run for 1.5 hours at 120 V, followed by transfer to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes using an Invitrogen power blotting system. The membranes were blocked for 1 hour in 5% milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS), followed by incubation overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies in TBS: anti-SUZ12 (1 μg/mL, ab12073, Abcam), anti-COPRS (1:500, NBP2-30884, Novus Biologicals), anti-CRLF3 (1:100, HPA007596, Sigma-Aldrich), anti-ATAD5 (1:500, LS-C19118, Lifespan Biosciences), anti-UTP6 (1:300, 17671-1-AP, Proteintech), anti-N-cadherin (1:1000, ab18203, Abcam), anti-neurofibromin (1:100; unpublished data), anti-Vinculin (1:5000, ab129002, Abcam) and anti-GAPDH (1:2,000, ab8245, Abcam). After washing with TBS, blots were incubated with a 1:5,000 dilution of goat anti-rabbit IRDye 680RD (926-68071, LI-COR Biosciences) and goat anti-mouse IRDye 800CW (925-32210, LI-COR Biosciences) secondary antibodies in TBS for one hour at room temperature. Imaging of immunoblots was performed using a LI-COR Odyssey Fc imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences). Protein bands were quantified using LI-COR Image Studio Software v5.2, and experimental protein values were normalized to GAPDH or Vinculin as an internal loading control.

RNA interference

CTL1 hiPSCs were infected with four independent CRLF3 shRNA lentiviral particles (sc-94066-V, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; shCRLF3 A: AAAGGCTTCGCACATTCAGTTGGACAGCT; shCRLF3 B: TACAGTCTGAGCAGTCGAAGAAATATAGC; shCRLF3 C: GACATTGAAGCCGTGACTCTAGGAACCAC; TL305215V, Origene) (MOI = 5) or control shRNA lentiviral particles (sc-108080, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; TR30021V shRNA scramble control particles, Origene) (MOI = 5). Infected cultures were incubated with mTeSR Plus medium (05825, STEMCELL Technologies) containing 0.4 μg/mL puromycin (73342, STEMCELL Technologies) for selection, and the medium was replaced every other day until drug-resistant colonies formed (~14 days). Resulting colonies were expanded, assayed for CRLF3 gene expression by western blotting and were differentiated into NSCs or hCOs.

Ortholog sequence comparison

NCBI’s Eukaryotic Genome Annotation pipeline was used to identify vertebrate orthologs of human CRLF3. Amino acid sequence alignments were generated by NCBI’s constraint-based multiple alignment tool (Cobalt) that finds a collection of pairwise constraints derived from conserved domain database, protein motif database, and sequence similarity, using RPS-BLAST, BLASTP, and PHIBLAST (Papadopoulos and Agarwala, 2007). Alignment results were visualized by Jalview.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. Sample size was deemed satisfactory based on the magnitude and consistency of differences between groups. No randomization of samples was performed, and investigators were not blinded during experiments and outcome assessment. Image fields for NeuroD1+ neuronal quantifications were selected from the inner subventricular zones of hCOs. Image fields for NeuN+, TBR1+ and SATB2+ neuronal quantifications were selected from the outer subventricular zones of hCOs. The number of biological replicates (hCOs) per independent experimental replicate per genotype is provided in the figure legends. For each genotype, all available clones were analyzed. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 software. Statistical significance was determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, Bonferroni multiple comparisons test, Tukey multiple comparison’s test, two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test, or unpaired, two-tailed t test. The exact values from the tests are indicated in the figures. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. Bar graphs indicate the mean ± SEM. Boxplot indicates median (central line), interquartile range (box) and minimum and maximum values (whiskers).

A summary table summarizing all the experiments is now included in Table S4, discriminating the samples in each figure panel with the statistical methods used for analysis.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Mouse monoclonal anti-SOX2 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 4900; RRID: AB_10560516 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-SOX2 | Abcam | Cat# ab92494; RRID: AB_10585428 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-Oct-4A | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 2840; RRID: AB_2167691 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Nanog | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 3580; RRID: AB_2150399 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-SMI-32 | Biolegend | Cat# 801701; RRID: AB_2564642 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-SMI-312 | Biolegend | Cat# 837904; RRID: AB_2566782 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-NeuroD1 | Abcam | Cat# ab205300 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-NeuroD1 | Abcam | Cat# ab60704; RRID: AB_943491 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-NeuN | Millipore | Cat# MAB377; RRID: AB_2298772 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-Ki-67 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 556003; RRID: AB_396287 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-MAP2 [HM-2] | Abcam | Cat# ab11267; RRID: AB_297885 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-Cleaved Caspase-3 (Asp175) (5A1E) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 9664; RRID: AB_2070042 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-active Caspase-3 | R&D systems | Cat# AF835; RRID: AB_2243952 |

| Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A-11034; RRID: AB_2576217 |

| Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A-11029; RRID: AB_138404 |

| Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 568 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A-11011; RRID: AB_143157 |

| Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 568 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A-11004; RRID: AB_2534072 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-SUZ12 | Abcam | Cat# ab12073; RRID: AB_442939 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-COPRS | Novus Biologicals | Cat# NBP2-30884 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-CRLF3 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# HPA007596; RRID: AB_1847241 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-ATAD5 | Lifespan Biosciences | Cat# LS-C19118-100; RRID: AB_1569353 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-UTP6 | Proteintech | Cat# 17671-1-AP; RRID: AB_2214465 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH [6C5] | Abcam | Cat# ab8245; RRID: AB_2107448 |

| IRDye 680RD Goat anti-Rabbit IgG antibody | LI-COR Biosciences | Cat# 926-68071; RRID: AB_10956166 |

| IRDye 800CW Goat anti-Mouse IgG antibody | LI-COR Biosciences | Cat# 925-32210; RRID: AB_2687825 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-PAX6 | Abcam | Cat# ab19504; RRID: RRID:AB_2750924 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-OTX2 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# MA5-15854; RRID:AB_11155193 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-EN1 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# PA5-14149; RRID:AB_2231168 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-GBX2 | Lifespan Biosciences | Cat# LS-C197281; NA |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-TBR1 | Abcam | Cat# ab31940; RRID:AB_2200219 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-SATB2 | Abcam | Cat# ab51502; RRID:AB_882455 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-N-cadherin | Abcam | Cat# ab18203; RRID:AB_444317 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-Neurofibromin | Unpublished data | N/A |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Nestin | Abcam | Cat# ab92391; RRID:AB_10561437 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-Vimentin | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 5741; RRID:AB_10695459 |

| Rabbit monoclonal Anti-Vinculin | Abcam | Cat# ab129002; RRID:AB_11144129 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-neurofibromin | proprietary | N/A |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| CRLF3 shRNA lentiviral particles | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-94066-V |

| Control shRNA lentiviral particles | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-108080 |

| CRLF3-Human shRNA lentiviral particles (4 unique 29-mer target-specific shRNA, 1 scramble control) | OriGene Technologies | Cat# TL305215V |

| Control Lenti particles, scrambled shRNA | OriGene Technologies | Cat# TR30021V |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Matrigel® Basement Membrane Matrix | Corning | Cat# 354234 |

| mTeSR Plus | STEMCELL Technologies | Cat# 05825 |

| ReLeSR | STEMCELL technologies | Cat# 05873 |

| STEMdiff Neural Induction Medium | STEMCELL technologies | Cat# 05835 |

| Recombinant Human FGF-basic (154 a.a.) | PeproTech | Cat# 100-18B |

| Y27632 RHO/ROCK pathway inhibitor | STEMCELL technologies | Cat# 72307 |

| GIBCO B-27 Plus Supplement (50X) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A3582801 |

| GIBCO Neurobasal Medium | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 21-103-049 |

| GIBCO DMEM/F-12, HEPES | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 11330057 |

| GIBCO N-2 Supplement (100X) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 17502001 |

| Human recombinant insulin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# I2643-25MG |

| GIBCO Penicillin-Streptomycin (5,000 U/mL) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 15070063 |

| RIPA Lysis and Extraction Buffer | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 89900 |

| GIBCO MEM Non-Essential Amino Acids Solution (100X) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 11140050 |

| GIBCO GlutaMax Supplement | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 35050061 |

| 2-Mercaptoethanol | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# M6250 |

| Recombinant Human Erythropoietin/EPO (Tissue Culture Grade) | R&D Systems | Cat# 287-TC-500 |

| Triton X-100 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# X100 |

| Shandon Immu-Mount | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 9990402 |

| Tissue-Tek® O.C.T. Compound, Sakura® Finetek | Electron Microscopy Sciences | Cat# 4583 |

| Hoechst 33258, Pentahydrate (bis-Benzimide) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# H3569 |

| Pan-RAS-IN-1 | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-101295 |

| 4x Laemmli Sample Buffer | Bio-Rad | Cat# 1610747 |

| Aprotinin, serine protease inhibitor | Abcam | Cat# ab146286 |

| Leupeptin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# L2884 |

| PMSF | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 10837091001 |

| Puromycin | STEMCELL Technologies | Cat# 73342 |

| GIBCO Goat serum | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 16210064 |

| Poly-L-Ornithine Solution (0.01%) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# A-004-C |

| CellAdhere Laminin-521 | STEMCELL Technologies | Cat# 77003 |

| SB 431542 | Tocris | Cat# 1614 |

| Compound E | STEMCELL Technologies | Cat# 73952 |

| Dorsomorphin | Abcam | Cat# ab120843 |

| Recombinant Human LIF | PeproTech | Cat# 300-05 |

| Accutase® Cell Detachment Solution | Fisher Scientific | Cat# MT25058CI |

| RhoA activator CN03A | Cytoskeleton | Cat# NC0272107 |

| Recombinant Human/Murine/Rat BDNF | PeproTech | Cat# 450-02 |

| Recombinant Human IGF-I | PeproTech | Cat# 100-11 |

| Human Recombinant GDNF | STEMCELL Technologies | Cat# 78058 |

| Dibutyryl-cAMP, sodium salt 250mg | PeproTech | Cat# 1698950 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Click-iT EdU Cell Proliferation Kit for Imaging, Alexa Fluor 488 dye | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# C10337 |

| In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, Fluorescein | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 11684795910 |

| Ras Activation ELISA, Colorimetric | Cell Biolabs | Cat# STA-440 |

| RNeasy Mini Kit | QIAGEN | Cat# 74104 |

| Applied Biosystems High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit with RNase Inhibitor | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 4374966 |

| Applied Biosystems TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix, no UNG | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A44359 |

| Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 23225 |

| RhoA G-LISA Activation Assay, colorimetric | Cytoskeleton | Cat# BK124 |

| Rac1 G-LISA Activation Assay, colorimetric | Cytoskeleton | Cat# BK128 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Whole exome sequencing data | This paper | SRA: PRJNA698597 |

| RNA sequencing data | This paper | GEO: GSE166080 |

| Human RNA-seq time-series of the development of seven major organs | Expression Atlas | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gxa/experiments/E-MTAB-6814/Results |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| BJFF.6 (CTL1) hiPSCs | GeiC – Washington University | RRID: CVCL_VU02 |

| TGD1 hiPSCs | This paper | N/A |

| TGD2 hiPSCs | This paper | N/A |

| TGD3 hiPSCs | This paper | N/A |

| aTGD hiPSCs | This paper | N/A |

| shCTL1 hiPSCs | This paper | N/A |

| shCTL2 hiPSCs | This paper | N/A |

| shCTL3 hiPSCs | This paper | N/A |

| shCTL4 hiPSCs | This paper | N/A |

| shCRLF3-1 hiPSCs | This paper | N/A |

| shCRLF3-2 hiPSCs | This paper | N/A |

| shCRLF3-3 hiPSCs | This paper | N/A |

| shCRLF3-4 hiPSCs | This paper | N/A |

| c.1149C > A NF1-mutant hiPSCs | Anastasaki et al., 2020 | N/A |

| c.1185+1G > A NF1-mutant hiPSCs | Anastasaki et al., 2020 | N/A |

| c.3431-32_dupGT NF1-mutant hiPSCs | Anastasaki et al., 2020 | N/A |

| c.5425C > T NF1-mutant hiPSCs | Anastasaki et al., 2020 | N/A |

| c.6619C > T NF1-mutant hiPSCs | Anastasaki et al., 2020 | N/A |

| CTL2 hiPSCs | GeiC – Washington University (Dr. Matthew B. Harms) |

N/A |

| CTL3 hiPSCs | GeiC – Washington University (Dr. Fumihiko Urano) |

N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Human CRLF3 - TaqMan® Gene Expression Assay FAM-MGB | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Hs00367579_m1 |

| Human ATAD5 TaqMan® Gene Expression Assay FAM-MGB | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Hs00227495_m1 |

| Human TEFM TaqMan® Gene Expression Assay FAM-MGB | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Hs00895248_m1 |

| Human ADAP2 TaqMan® Gene Expression Assay FAM-MGB | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Hs01106939_m1 |

| Human COPRS TaqMan® Gene Expression Assay FAM-MGB | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Hs01047650_m1 |

| Human UTP6 TaqMan® Gene Expression Assay FAM-MGB | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Hs00251161_m1 |

| Human SUZ12 TaqMan® Gene Expression Assay FAM-MGB | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Hs00248742_m1 |

| Human LRRC37B TaqMan® Gene Expression Assay FAM-MGB | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Hs03045845_m1 |

| Human MIR193A TaqMan® Gene Expression Assay FAM-MGB | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Hs04273253_s1 |

| Human MIR365B TaqMan® Gene Expression Assay FAM-MGB | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Hs04231549_s1 |

| Human MIR4725 TaqMan® Gene Expression Assay FAM-MGB | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Hs06637953_s1 |

| Human MIR4733 TaqMan® Gene Expression Assay FAM-MGB | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Hs04274676_s1 |

| Human GAPDH TaqMan® Gene Expression Assay FAM-MGB | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Hs02786624_g1 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Samtools 1.4.1 | http://samtools.sourceforge.net/ | RRID: SCR_002105 |

| SnpEff | http://snpeff.sourceforge.net/ | RRID: SCR_005191 |

| Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD) | https://cadd.gs.washington.edu/ | RRID: SCR_018393 |

| SIFT | https://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/ | RRID: SCR_012813 |

| PolyPhen: Polymorphism Phenotyping | http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/ | RRID: SCR_013189 |

| Likelihood ratio test (LRT) | http://www.genetics.wustl.edu/jflab/lrt_query.html | N/A |

| GERP++ | http://mendel.stanford.edu/SidowLab/downloads/gerp/ | RRID: SCR_000563 |

| Fathmm | http://fathmm.biocompute.org.uk/fathmm-xf/about.html | N/A |

| Leica Application Suite X software | https://www.bio-rad.com/enus/sku/1845000-cfx-managersoftware?ID=1845000 | RRID: SCR_013673 |

| ImageJ/ Fiji v1.8 | https://fiji.sc | RRID: SCR_002285 |

| Bio-Rad CFX Manager 3.1 | https://www.bio-rad.com/enus/sku/1845000-cfx-managersoftware?ID=1845000 | N/A |

| LI-COR Image Studio Software v5.2 | https://www.licor.com/bio/image-studio/ | RRID: SCR_015795 |

| COBALT: Constraint-based Multiple Alignment Tool | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/cobalt/cobalt.cgi?link_loc=BlastHomeAd | RRID: SCR_004152 |

| GraphPad Prism 8 | https://www.graphpad.com:443/ | RRID: SCR_002798 |

| Adobe Illustrator 2020 | https://www.adobe.com/products/illustrator.html | RRID: SCR_010279 |

| Adobe Photoshop 2020 | https://www.adobe.com/products/photoshop.html | RRID: SCR_014199 |

| Jalview | http://www.jalview.org/ | RRID: SCR_006459 |

| Samtools | http://samtools.sourceforge.net/ | RRID:SCR_002105 |

| bcl2fastq | https://support.illumina.com/sequencing/sequencing_software/bcl2fastq-conversion-software.html | RRID:SCR_015058 |

| STAR version 2.7.3a | https://github.com/alexdobin/STAR | RRID:SCR_015899 |

| Ensembl | http://www.ensembl.org//useast.ensembl.org/?redirectsrc=//www.ensembl.org%2F | RRID:SCR_002344 |

| DESeq2 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DESeq2.html | RRID:SCR_015687 |

| Partek Flow software, version 9.0.20 | https://www.partek.com/?q=partekgs | RRID:SCR_011860 |

| Gene Ontology enrichment | http://geneontology.org/ | RRID:SCR_002811 |

| Other | ||

| Corning® Costar® Ultra-Low Attachment 96 well round bottom plate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# CLS7007 |

| Corning® Costar® Ultra-Low Attachment 24 well plate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# CLS3473 |

| 25cm2 Tissue Culture Flask - Vent Cap, Sterile | CELLTREAT | Cat# 229331 |

| 6 Well Tissue Culture Plate, Sterile | Celltreat | Cat# 229106 |

Highlights.

Increased NSC proliferation in NF1-TGD hCOs is RAS-dependent

NF1-TGD hCOs have elevated neuronal survival and maturation deficits

Increased neuronal death and dendritic deficits in NF1-TGD hCOs are CRLF3-dependent

RhoA activation rescues neuronal survival and maturation deficits in NF1-TGD hCOs

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Matthew B. Harms and Dr. Fumihiko Urano (Washington University, St. Louis, MO) for providing neurologically normal control patient-derived hiPSC lines. This work was supported by a Young Investigator’s Award grant from the Children’s Tumor Foundation (2018-01-003 to M.L.W.) and a Research Program Award grant from the National Institutes of Health (1-R35-NS07211-01 to D.H.G.). The GeiC facility at WUSM engineered the hiPSCs and is subsidized by NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30-CA091842.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109315.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- Abrahams BS, Arking DE, Campbell DB, Mefford HC, Morrow EM, Weiss LA, Menashe I, Wadkins T, Banerjee-Basu S, and Packer A (2013). SFARI Gene 2.0: a community-driven knowledgebase for the autism spectrum disorders (ASDs). Mol. Autism 4, 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anastasaki C, Woo AS, Messiaen LM, and Gutmann DH (2015). Eluci-dating the impact of neurofibromatosis-1 germline mutations on neurofibromin function and dopamine-based learning. Hum. Mol. Genet 24, 3518–3528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anastasaki C, Wegscheid ML, Hartigan K, Papke JB, Kopp ND, Chen J, Cobb O, Dougherty JD, and Gutmann DH (2020). Human iPSC-derived neurons and cerebral organoids establish differential effects of germline NF1 gene mutations. Stem Cell Reports 14, 541–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arikkath J, Peng IF, Ng YG, Israely I, Liu X, Ullian EM, and Reichardt LF (2009). Delta-catenin regulates spine and synapse morphogenesis and function in hippocampal neurons during development. J. Neurosci 29, 5435–5442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. ; The Gene Ontology Consortium (2000). Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet 25, 25–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee-Basu S, and Packer A (2010). SFARI Gene: an evolving database for the autism research community. Dis. Model. Mech 3, 133–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YH, Gianino SM, and Gutmann DH (2015). Neurofibromatosis-1 regulation of neural stem cell proliferation and multilineage differentiation operates through distinct RAS effector pathways. Genes Dev. 29, 1677–1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe BP, Stessman HAF, Sulovari A, Geisheker MR, Bakken TE, Lake AM, Dougherty JD, Lein ES, Hormozdiari F, Bernier RA, and Eichler EE (2019). Neurodevelopmental disease genes implicated by de novo mutation and copy number variation morbidity. Nat. Genet 51, 106–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino JN, Zhang Y, Holzhauer K, Sant S, Long K, Vallorani A, Malik L, and Gutmann DH (2015). Distribution and within-family specificity of quantitative autistic traits in patients with neurofibromatosis type I. J. Pediatr 167, 621–626.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Raedt T, Beert E, Pasmant E, Luscan A, Brems H, Ortonne N, Helin K, Hornick JL, Mautner V, Kehrer-Sawatzki H, et al. (2014). PRC2 loss amplifies Ras-driven transcription and confers sensitivity to BRD4-based therapies. Nature 514, 247–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descheemaeker MJ, Roelandts K, De Raedt T, Brems H, Fryns JP, and Legius E (2004). Intelligence in individuals with a neurofibromatosis type 1 microdeletion. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 131, 325–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, and Gingeras TR (2013). STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas J, Cilliers D, Coleman K, Tatton-Brown K, Barker K, Bernhard B, Burn J, Huson S, Josifova D, Lacombe D, et al. ; Childhood Overgrowth Collaboration (2007). Mutations in RNF135, a gene within the NF1 microdeletion region, cause phenotypic abnormalities including overgrowth. Nat. Genet 39, 963–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elia LP, Yamamoto M, Zang K, and Reichardt LF (2006). p120 catenin regulates dendritic spine and synapse development through Rho-family GTPases and cadherins. Neuron 51, 43–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frega M, Linda K, Keller JM, Gümüş-Akay G, Mossink B, van Rhijn JR, Negwer M, Klein Gunnewiek T, Foreman K, Kompier N, et al. (2019). Neuronal network dysfunction in a model for Kleefstra syndrome mediated by enhanced NMDAR signaling. Nat. Commun 10, 4928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukata M, and Kaibuchi K (2001). Rho-family GTPases in cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2, 887–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert J, and Man HY (2016). The X-linked autism protein KIAA2022/KIDLIA regulates neurite outgrowth via N-cadherin and δ-catenin signaling. eNeuro 3, ENEURO.0238-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayton HM, Fernandes C, Rujescu D, and Collier DA (2012). Copy number variations in neurodevelopmental disorders. Prog. Neurobiol 99, 81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn N, Knorr DY, Liebig J, Wüstefeld L, Peters K, Büscher M, Bucher G, Ehrenreich H, and Heinrich R (2017). The insect ortholog of the human orphan cytokine receptor CRLF3 is a neuroprotective erythropoietin receptor. Front. Mol. Neurosci 10, 223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn N, Büschgens L, Schwedhelm-Domeyer N, Bank S, Geurten BRH, Neugebauer P, Massih B, Göpfert MC, and Heinrich R (2019). The orphan cytokine receptor CRLF3 emerged with the origin of the nervous system and is a neuroprotective erythropoietin receptor in locusts. Front. Mol. Neurosci 12, 251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegedus B, Dasgupta B, Shin JE, Emnett RJ, Hart-Mahon EK, Elghazi L, Bernal-Mizrachi E, and Gutmann DH (2007). Neurofibromatosis-1 regulates neuronal and glial cell differentiation from neuroglial progenitors in vivo by both cAMP- and Ras-dependent mechanisms. Cell Stem Cell 1, 443–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutsler JJ, and Zhang H (2010). Increased dendritic spine densities on cortical projection neurons in autism spectrum disorders. Brain Res. 1309, 83–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehrer-Sawatzki H, Mautner VF, and Cooper DN (2017). Emerging genotype-phenotype relationships in patients with large NF1 deletions. Hum. Genet 136, 349–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluwe L, Siebert R, Gesk S, Friedrich RE, Tinschert S, Kehrer-Sawatzki H, and Mautner VF (2004). Screening 500 unselected neurofibromatosis 1 patients for deletions of the NF1 gene. Hum. Mutat 23, 111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazar M, Miles LM, Babb JS, and Donaldson JB (2014). Axonal deficits in young adults with High Functioning Autism and their impact on processing speed. Neuroimage Clin. 4, 417–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DY, Yeh TH, Emnett RJ, White CR, and Gutmann DH (2010). Neurofibromatosis-1 regulates neuroglial progenitor proliferation and glial differentiation in a brain region-specific manner. Genes Dev. 24, 2317–2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W, Teckie S, Wiesner T, Ran L, Prieto Granada CN, Lin M, Zhu S, Cao Z, Liang Y, Sboner A, et al. (2014). PRC2 is recurrently inactivated through EED or SUZ12 loss in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Nat. Genet 46, 1227–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love MI, Huber W, and Anders S (2014). Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matter C, Pribadi M, Liu X, and Trachtenberg JT (2009). Delta-catenin is required for the maintenance of neural structure and function in mature cortex in vivo. Neuron 64, 320–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mautner VF, Kluwe L, Friedrich RE, Roehl AC, Bammert S, Högel J, Spöri H, Cooper DN, and Kehrer-Sawatzki H (2010). Clinical characterisation of 29 neurofibromatosis type-1 patients with molecularly ascertained 1.4 Mb type-1 NF1 deletions. J. Med. Genet 47, 623–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messiaen L, Vogt J, Bengesser K, Fu C, Mikhail F, Serra E, Garcia-Linares C, Cooper DN, Lazaro C, and Kehrer-Sawatzki H (2011). Mosaic type-1 NF1 microdeletions as a cause of both generalized and segmental neurofibromatosis type-1 (NF1). Hum. Mutat 32, 213–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SM, Acosta MT, Garg S, Green J, Huson S, Legius E, North KN, Payne JM, Plasschaert E, Frazier TW, et al. (2016). Disease burden and symptom structure of autism in neurofibromatosis type 1: a study of the International NF1-ASD Consortium Team (INFACT). JAMA Psychiatry 73, 1276–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukaetova-Ladinska EB, Arnold H, Jaros E, Perry R, and Perry E (2004). Depletion of MAP2 expression and laminar cytoarchitectonic changes in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in adult autistic individuals. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol 30, 615–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowski D, and Heinrich R (2018). Alternative erythropoietin receptors in the nervous system. J. Clin. Med 7, 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottenhoff MJ, Rietman AB, Mous SE, Plasschaert E, Gawehns D, Brems H, Oostenbrink R, ENCORE-NF1 Team; van Minkelen R, Nellist M, et al. (2020). Examination of the genetic factors underlying the cognitive variability associated with neurofibromatosis type 1. Genet. Med 22, 889–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos JS, and Agarwala R (2007). COBALT: constraint-based alignment tool for multiple protein sequences. Bioinformatics 23, 1073–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partek Inc (2020). Partek Flow software, version 9.0 (St. Louis, MO: Partek Inc.). [Google Scholar]

- Pasmant E, Sabbagh A, Spurlock G, Laurendeau I, Grillo E, Hamel MJ, Martin L, Barbarot S, Leheup B, Rodriguez D, et al. ; Members of the NF France Network (2010). NF1 microdeletions in neurofibromatosis type 1: from genotype to phenotype. Hum. Mutat 31, E1506–E1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pucilowska J, Vithayathil J, Pagani M, Kelly C, Karlo JC, Robol C, Morella I, Gozzi A, Brambilla R, and Landreth GE (2018). Pharmacological inhibition of ERK signaling rescues pathophysiology and behavioral phenotype associated with 16p11.2 chromosomal deletion in mice. J. Neurosci 38, 6640–6652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramocki MB, Bartnik M, Szafranski P, Kołodziejska KE, Xia Z, Bravo J, Miller GS, Rodriguez DL, Williams CA, Bader PI, et al. (2010). Recurrent distal 7q11.23 deletion including HIP1 and YWHAG identified in patients with intellectual disabilities, epilepsy, and neurobehavioral problems. Am. J. Hum. Genet 87, 857–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen SA, Colman SD, Ho VT, Abernathy CR, Arn PH, Weiss L, Schwartz C, Saul RA, and Wallace MR (1998). Constitutional and mosaic large NF1 gene deletions in neurofibromatosis type 1. J. Med. Genet 35, 468–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter M, Murtaza N, Scharrenberg R, White SH, Johanns O, Walker S, Yuen RKC, Schwanke B, Bedürftig B, Henis M, et al. (2019). Altered TAOK2 activity causes autism-related neurodevelopmental and cognitive abnormalities through RhoA signaling. Mol. Psychiatry 24, 1329–1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Ortiz E, Cho W, Nazarenko I, Mo W, Chen J, and Parada LF (2014). NF1 regulation of RAS/ERK signaling is required for appropriate granule neuron progenitor expansion and migration in cerebellar development. Genes Dev. 28, 2407–2420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shcheglovitov A, Shcheglovitova O, Yazawa M, Portmann T, Shu R, Sebastiano V, Krawisz A, Froehlich W, Bernstein JA, Hallmayer JF, and Dolmetsch RE (2013). SHANK3 and IGF1 restore synaptic deficits in neurons from 22q13 deletion syndrome patients. Nature 503, 267–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan SA, Andersen J, Pașca AM, Birey F, and Pașca SP (2018). Generation and assembly of human brain region-specific three-dimensional cultures. Nat. Protoc 13, 2062–2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan ZJ, Peng Y, Song HL, Zheng JJ, and Yu X (2010). N-cadherin-dependent neuron-neuron interaction is required for the maintenance of activity-induced dendrite growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 9873–9878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tastet J, Decalonne L, Marouillat S, Malvy J, Thépault RA, Toutain A, Paubel A, Tabagh R, Bénédetti H, Laumonnier F, et al. (2015). Mutation screening of the ubiquitin ligase gene RNF135 in French patients with autism. Psychiatr. Genet 25, 263–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner TN, Sharma K, Oh EC, Liu YP, Collins RL, Sosa MX, Auer DR, Brand H, Sanders SJ, Moreno-De-Luca D, et al. (2015). Loss of δ-catenin function in severe autism. Nature 520, 51–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venturin M, Guarnieri P, Natacci F, Stabile M, Tenconi R, Clementi M, Hernandez C, Thompson P, Upadhyaya M, Larizza L, and Riva P (2004). Mental retardation and cardiovascular malformations in NF1 microdeleted patients point to candidate genes in 17q11.2. J. Med. Genet 41, 35–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venturin M, Carra S, Gaudenzi G, Brunelli S, Gallo GR, Moncini S, Cotelli F, and Riva P (2014). ADAP2 in heart development: a candidate gene for the occurrence of cardiovascular malformations in NF1 microdeletion syndrome. J. Med. Genet 51, 436–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Kim E, Wang X, Novitch BG, Yoshikawa K, Chang LS, and Zhu Y (2012). ERK inhibition rescues defects in fate specification of Nf1-deficient neural progenitors and brain abnormalities. Cell 150, 816–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassef M, Luscan A, Aflaki S, Zielinski D, Jansen PWTC, Baymaz HI, Battistella A, Kersouani C, Servant N, Wallace MR, et al. (2019). EZH1/2 function mostly within canonical PRC2 and exhibit proliferation-dependent redundancy that shapes mutational signatures in cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 6075–6080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff JJ, Gu H, Gerig G, Elison JT, Styner M, Gouttard S, Botteron KN, Dager SR, Dawson G, Estes AM, et al. ; IBIS Network (2012). Differences in white matter fiber tract development present from 6 to 24 months in infants with autism. Am. J. Psychiatry 169, 589–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2017). Global accelerated action for the health of adolescents (AA-HA!): guidance to support country implementation: summary (Geneva: World Health Organization; ). [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Xu YP, Li J, Duan SS, Fu YJ, Zhang Y, Zhao Y, Qiao WT, Chen QM, Geng YQ, et al. (2009). Cloning and characterization of a novel intracellular protein p48.2 that negatively regulates cell cycle progression. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol 41, 2240–2250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Wang Y, Jones S, Sausen M, McMahon K, Sharma R, Wang Q, Belzberg AJ, Chaichana K, Gallia GL, et al. (2014). Somatic mutations of SUZ12 in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Nat. Genet 46, 1170–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This study did not generate any codes. The whole exome sequencing data are available under accession number PRJNA698597 (SRA database). The RNA sequencing data are available in the GEO repository (GSE166080). Any other relevant data are available from the corresponding author upon request.