Abstract

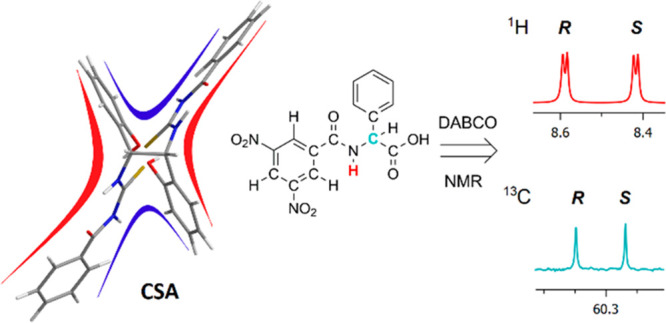

The reaction of benzoyl isothiocyanate with (1R,2R)-1,2-bis(2-hydroxyphenyl)ethylenediamine afforded a new thiourea chiral solvating agent (CSA) with a very high ability to differentiate 1H and 13C NMR signals of simple amino acid derivatives, even at low concentrations. The enantiodiscrimination efficiency was higher with respect to that of the parent monomer, a thiourea derivative of 2-((1R)-1-aminoethyl)phenol, thus putting into light the relevance of the cooperativity between the two molecular portions of the dimer in a cleft conformation stabilized by interchain hydrogen bond interactions. An achiral base additive (DABCO or DMAP) played an active role in the chiral discrimination processes, mediating the interaction between the CSA and the enantiomeric mixtures. The chiral discrimination mechanism was investigated by NMR spectroscopy through the determination of complexation stoichiometries, association constants, and the stereochemistry of the diastereomeric solvates.

Introduction

Oftentimes, dramatic differences in the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of pure enantiomeric forms of therapeutic agents have increasingly brought to light the outstanding role of chirality and a generated great awareness of the need for rigorous and reproducible methods to properly identify and quantify stereoisomeric forms of chiral substrates, with a strong preference toward noninvasive methods involving minimum manipulative procedures, such as spectroscopic methods. Among them, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is notable because it provides several measurable parameters for each of the observable NMR-active nuclei of the enantiomeric products as long as they are made intrinsically anisochronous and hence differentiable by the use of a suitable chiral auxiliary that is enantiomerically pure and able to transfer enantiomers into a diastereomeric environment. Three main classes of chiral auxiliaries for NMR spectroscopy have been developed to this purpose, among which chiral solvating agents (CSAs)1−4 stand out for their practicality of use, being simply mixed to the enantiomeric mixtures into the NMR tube without need for chemical derivatization and subsequent purification procedures. The majority of CSAs are simple chiral platforms, the functional groups of which may be modified to address the enantiodiscriminating efficiencies and versatilities. In some cases, rigid structures are privileged with a hydrogen-bond donor or acceptor and aromatic groups, the anisotropic effects of which are ultimately responsible for the chemical shift differentiation of the enantiomeric pairs. Design efforts are sometimes pursued to develop highly preorganized macrocyclic structures in favor of a pronounced enantiodiscriminating efficiency toward selected classes of chiral substrates, and more flexible structures could be preferred in view of enhancing the enantiodiscriminating versatility.

In spite of the vastness of structural features of CSAs, which makes them able to cover the chiral analysis of the majority of organic chiral compounds, the enantiomeric differentiation of amino acids remains a challenging task. As a matter of fact, only very few cases of the direct analysis of underivatized amino acids have been reported, such as in the case of the chiral crown ether reported by Wenzel5 or the flavonoid epigallocatechin gallate.6 Other CSAs offered interesting opportunities for the analysis of the N-tosyl7−11 and N-phthaloyl12,13 derivatives of amino acids, where the methyl group of the tosyl moiety also acts as the probe for the NMR enantiodifferentiation.

Therefore, leaving behind the ambitious purpose of obtaining CSAs for underivatized systems, the development of new versatile and efficient CSAs for the differentiation of amino acid derivatives remains a relevant topic, particularly when simple synthetic procedures are involved in the syntheses of both the CSA and the amino acid derivatives and, possibly, the moiety introduced in the amino acid affords itself suitable probe signals for the differentiation and quantification of the enantiomeric substrates in the NMR spectra.

Treat potential of thiourea CSAs13−25 has been shown mainly in the past few years, and the TMA derivative (Figure 1) of commercially available 2-((1R)-1-aminoethyl)phenol (MA, Figure 1) has been recently proposed.25 Here, we explore the potentialities of a C2-symmetric chiral bis-thiourea derivative, BTDA (Figure 1), of commercially available (1R,2R)-1,2-bis(2-hydroxyphenyl)ethylenediamine (DA, Figure 1) as a chiral solvating agent for amino acid derivatives (Figure 1). BTDA is endowed with a tweezer-like structure that potentially has cooperative binding sites. Possible beneficial effects of a third achiral base additive (1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane, DABCO, or N,N-dimethylpyridin-4-amine, DMAP) were also taken into consideration. 1H and 13C NMR enantiodiscrimination experiments were performed, and the chiral discrimination mechanism was carefully investigated by NMR.

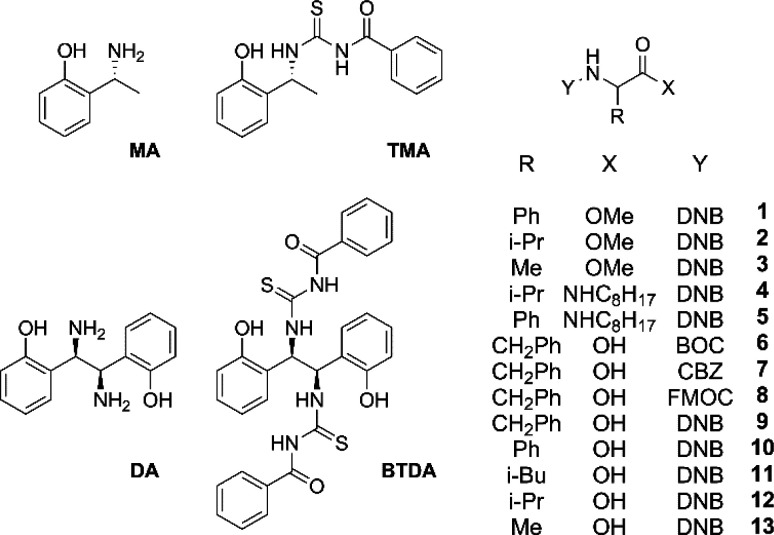

Figure 1.

Amine precursors (MA and DA), their respective CSAs (TMA and BTDA), and derivatives 1–13 (DNB = 3,5-dinitrobenzoyl, BOC = tert-butyloxycarbonyl, CBZ = benzyloxycarbonyl, FMOC = fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl).

Results and Discussion

The reaction of DA with 2 equiv of benzoyl isothiocyanate proceeded selectively at the amino groups, leading to the thiourea derivative BTDA in a quantitative yield. No purification steps were required. BTDA showed a good solubility in CDCl3, which is privileged as a solvent in NMR enantiodiscrimination experiments.

The good solubility of both the CSA and the enantiomeric substrates in the same solvent constitutes a prerequisite for the optimization of enantiodiscrimination experiments to affect the stereoselective complexation equilibrium by changing the total concentration and either the CSA-to-substrate molar ratio or temperature. Therefore, different derivatizations of amino acids were searched to improve their CDCl3 solubility. Amino acids derivatized both at the amino and carboxyl functions showed very good solubilities in organic solvents.

In particular, amino acids with a 3,5-dinitrobenzoyl linked to the amino group offered a dual advantage. First, their 3,5-dintrophenyl protons resonate in a spectral region that is free of interference from the CSA signals and can therefore be used as basis for the detection and quantification of enantiomers. Importantly, the same aromatic moiety can favor π–π stacking interactions with aromatic groups of the CSA, thus stabilizing the diastereomeric solvates. The derivatization of the carboxyl group as a methyl ester (1–3) affords a sharp singlet, which is very useful for the quantification of enantiomers and also accurate when the magnitude of the nonequivalence is scarce. On the other hand, having an additional amide function at the carboxyl group, such as in 4 and 5, could favor brush-type interactions with polyamide CSAs. In the case of amino acids with a free carboxylic group, the use of a base additive was needed as a solubilizing promoter, which in principle could play an active role in mediating the enantioselective interactions with the chiral auxiliary as was also demonstrated for the monomeric TMA.

1H NMR Enantiodiscrimination Experiments

Enantiodiscrimination experiments were carried out by adding one equivalent of BTDA to the CDCl3 solution of the selected amino acid derivative. Splittings of the NMR signals of enantiomeric substrates were detected and, for selected cases, the magnitude of the splittings (nonequivalence, i.e., the difference, in either hertz or parts per million, between the chemical shifts of the corresponding signals of the two enantiomers in the mixtures containing the CSA, ΔΔδ = |ΔδR – ΔδS| = |δR – δS|, where ΔδR = δmixtureR – δfree and ΔδS = δmixture – δfree are the complexation shifts) was compared to that obtained in the presence of the previously reported chiral auxiliary TMA.25

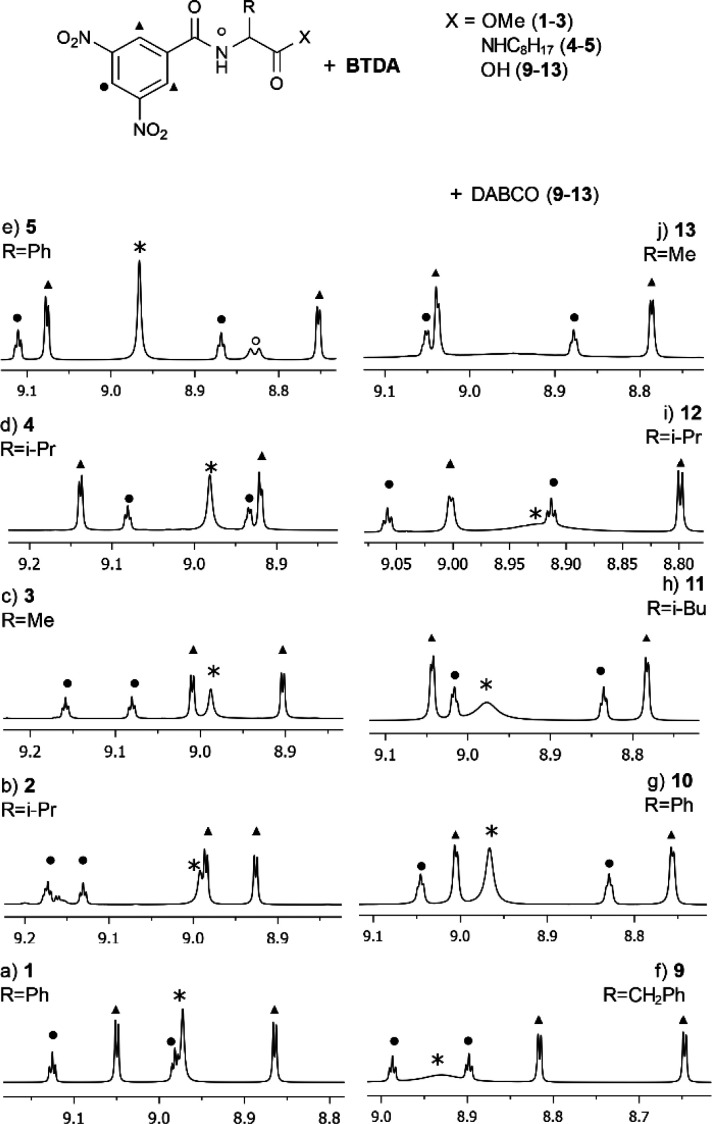

Nonequivalences obtained for the derivatives 1–13 at 30 mM in the presence of 1 equiv of BTDA are collected in Table 1. NMR spectra corresponding to 3,5-dinitrophenyl, NH, and CH protons of 1–5 and 9–13 are shown in Figure 2 and Figures S1 and S2 in the Supporting Information, respectively.

Table 1. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) Nonequivalences (ΔΔδ, ppm) of 1–5 (30 mM) in the Presence of an Equimolar Amount of BTDA and 6–13 (30 mM) in the Presence of Equimolar Amounts of BTDA and DABCO.

| substrate | pDNBa | oDNBb | NH | CHc | CO-R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.141 | 0.186 | 0.210 | 0.043 | 0.036d |

| 2 | 0.041 | 0.060 | 0.021 | 0.008 | 0.007d |

| 3 | 0.078 | 0.106 | 0.009 | 0.005 | 0.008d |

| 4 | 0.147 | 0.219 | 0.047 | 0.034 | 0.055e |

| 5 | 0.243 | 0.324 | 0.113 | 0.028 | 0.160e |

| 6f | 0.089 | 0.030 | |||

| 7 | 0.103 | 0.030 | |||

| 8 | 0.147 | 0.021 | |||

| 9 | 0.089 | 0.169 | 0.042 | 0.050 | |

| 10 | 0.216 | 0.247 | 0.173 | 0.049 | |

| 10g | 0.209 | 0.256 | 0.074 | 0.042 | |

| 11 | 0.180 | 0.260 | 0.053 | 0.080 | |

| 12 | 0.145 | 0.202 | 0.045 | 0.096 | |

| 13 | 0.174 | 0.253 | 0.074 | 0.081 |

para-Proton of the DNB moiety.

ortho-Protons of DNB moiety.

Methine proton of the chiral center.

R = OMe.

R = NHC8H17.

A nonequivalence of 0.031 ppm was measured on the methyl signal of BOC.

In the presence of DMAP.

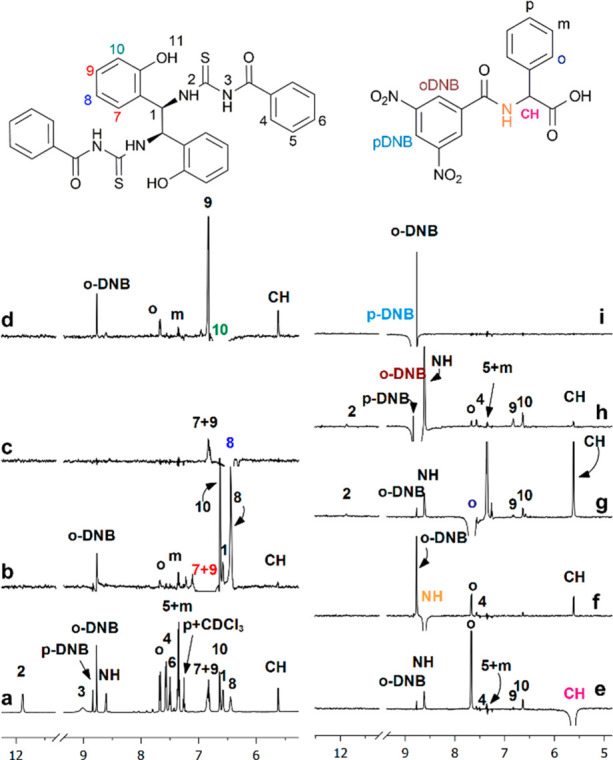

Figure 2.

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) spectral regions corresponding to the ortho- and para-DNB protons of a 1:1 mixture of BTDA (30 mM)/racemic (a) 1, (b) 2, (c) 3, (d) 4, or (e) 5. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) spectral regions corresponding to the ortho- and para-DNB protons of a 1:1:1 mixture of BTDA (30 mM)/DABCO/racemic (f) 9, (g) 10, (h) 11, (i) 12, and (j) 13. The asterisk (*) indicates the resonance of CSA.

Regarding amino acid derivatives 1–5 with protected NH and COOH functions, BTDA induced very high nonequivalences for proton nuclei of the phenylglycine derivative 1, which ranged from the minimum value of 0.036 ppm for the singlet of the methoxy group at the carboxyl function up to the very high value of 0.210 ppm for the NH proton. Lower values were measured in the analogous derivatives of valine (2) and alanine (3), but in any case the splittings at the 3,5-dinitrobenzoyl proton resonances guaranteed the accurate quantification of enantiomers. Improving hydrogen-bond donor and hydrogen-bond acceptor interactions, such as those for 4 and 5, remarkably enhanced the differentiation of the 3,5-dinitrophenyl protons with nonequivalences, up to 0.243 and 0.324 ppm in the case of 5 for the para- and ortho-DNB, respectively. It is noteworthy that alkylamide derivatives 4 and 5 afforded a further NH signal, the nonequivalences of which were of 0.055 (4) and 0.160 ppm (5).

In the search for simplified derivatization procedures for the amino acids, several kinds of N-derivatizations of phenylalanine were attempted (6–9), leaving the carboxyl function underivatized. The above-mentioned derivatives were scarcely soluble in CDCl3, but their solubility could be improved by adding equimolar amounts of a strong organic base (DABCO or DMAP). Nonequivalences detected in the ternary mixtures 6–9/BTDA/DABCO (1:1:1) were once again very high and scarcely affected by the nature of the derivatizing group linked to the amino group, since quite similar values were obtained for NH and CH protons (Table 1). While FMOC, BOC, and CBZ substrates 6–8 could be more relevant from a daily life perspective, the slow-exchanging syn- and anti-stereoisomeric forms could make the quantification of the enantiomers unreliable. In any case, nonequivalences spanning from 0.089 to 0.147 ppm were measured for the NH proton. Such interconverting species were not present in the case of 9, which contained a 3,5-dinitrobenzoyl group at the nitrogen. Interestingly the enantiodiscrimination of BOC and CBZ derivatives of amino acids was reported by Tanaka et al.12 in the presence of substoichiometric amounts of a macrocyclic CSA.

NMR data collected for compounds 1–9 suggested favoring the analysis of N-3,5-dinitrobenzoyl derivatives of amino acids with free carboxyl functions in ternary mixtures CSA/substrate/base, as they had the best balance between the practicality of the synthesis of amino acid derivatives and the efficiency of the NMR enantiodiscrimination. Therefore, analogous derivatives of phenylglycine (10), leucine (11), valine (12), and alanine (13) were taken into consideration and analyzed in ternary mixtures containing equimolar amounts of DABCO and BTDA. In the case of 10, nonequivalences of 0.247, 0.216, 0.173, and 0.049 ppm were measured for ortho- and para-protons of DNB and NH and the methine proton at the chiral center, respectively. Aromatic protons of the phenyl moiety were themselves remarkably perturbed, as demonstrated by 1D-ROESY and 1D-TOCSY experiments, allowing the extraction of their resonances. There was a nonequivalence of 0.170 ppm for the ortho-protons (Figure S3 in Supporting Information).

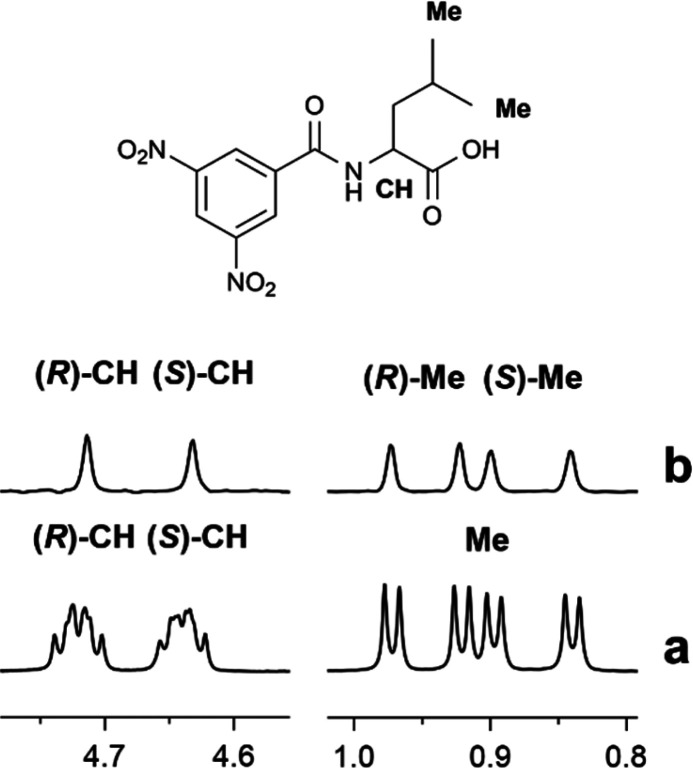

Similarly, high nonequivalence values were also recorded for amino acid derivatives with branched aliphatic moieties, such as in the case of leucine 11 (Figure 3) and valine 12 in which remarkable doublings were induced on the diastereotopic methyl groups of the isopropyl moiety. Suppressing homonuclear scalar couplings by means of suitable pulse sequences allows an extension of the chiral analysis to complex or partially superimposed NMR signals, as shown in Figure 3. Singlets were obtained for the methyl and methine resonances of 11 by means of pure-shift experiments.

Figure 3.

(a) 1H NMR (600 MHz, 30 mM, CDCl3, 25 °C) spectrum of the equimolar mixture 11/BTDA/DABCO. (b) Pure-shift 1H NMR (600 MHz, 30 mM, CDCl3, 25 °C) spectrum of the equimolar mixture 11/BTDA/DABCO.

The high efficiency of BTDA was confirmed even in the case of the simplest amino acid derivative 13, with the ortho- and para-protons of electron-poor ring differentiated by 0.253 and 0.174 ppm, respectively. Nonequivalences about of 0.080 ppm were obtained for the amide and methine protons. In any case, significantly higher nonequivalences were measured for N-3,5-dinitrobenzoyl derivatives with a free carboxylic function compared to those of the corresponding methyl ester compounds (10 vs 1, 12 vs 2, and 13 vs 3).

Interestingly, the high nonequivalences of almost every derivative were due to major complexation shifts of the (R)-enantiomer with respect to the (S)-enantiomer (Table S1 in Supporting Information). As the result of the interaction with the CSA, the ortho- and para-protons of the dinitrobenzoyl moiety of the (R)-enantiomer were more shielded than those of the (S)-enantiomer. Unexpectedly, an enhanced low-frequency complexation shift was also detected for the NH proton of the (R)-enantiomer, suggesting that complexation shifts were heavily affected by the anisotropic effects produced by the aromatic moieties of the CSA rather than by the reinforcement of hydrogen bond interactions, which should have produced a major deshielding for the enantiomer that formed the tighter diastereomeric pair with the CSA ((R)-enantiomer, vide infra). Only the methine protons underwent a deshielding effect upon complexation, which was more enhanced for the (R)-enantiomer.

Concerning the effect of the nature of the third achiral component in the ternary CSA/substrate/base mixture, DMAP was also tried in the same experimental conditions (CDCl3, 30 mM, 10/BTDA/base 1:1:1 mixture). The nonequivalences measured for the ortho- and para-protons of the 3,5-dinitrobenzoyl moiety were very similar to those of DABCO, whereas a smaller value was measured for the amide proton (Table 1, Figure S4 in the Supporting Information). In any case, DABCO was preferred due to the fact that it produced one singlet at 2.78 ppm.

To understand the role of the base beyond its solubilizing properties, binary 10/BTDA and ternary 10/BTDA/DABCO mixtures were compared using a CDCl3/DMSO-d6 solvent mixture that contained the minimum amount of DMSO-d6 (40 μL in 640 μL of CDCl3) needed to solubilize 10. As shown in Figure S5 in the Supporting Information, larger nonequivalences were attained in the mixture containing DABCO (nonequivalences of 0.003 and 0.017 ppm in the absence and in the presence of DABCO, respectively), confirming the active role of the base in the stabilization of diastereomeric solvates.

Comparing BTDA to previously reported monomeric TMA shone light on the eventual cooperative behavior of the two thiourea moieties of BTDA in the interaction with the enantiomeric substrates (Table 2). TMA produced significantly lower differentiations of 1–5 and 9–13 resonances than BTDA did in the same experimental conditions (equimolar amounts of CSA at 30 mM, Table 2). BTDA and TMA showed very different dependencies on the dilution. In the 30–5 mM range, the enantiodifferentiation of 10 and 11 underwent 35% and 80% reductions for DNB protons in the presence of BTDA and TMA, respectively (Tables 2 and 3). Therefore, the use of BTDA as a CSA seemed greatly advantageous compared to the corresponding monomeric CSA, including when the scarce dependence on concentration gradients was considered. The nonequivalences measured for 10 were still remarkable at 5 mM with doublings of 0.140, 0.159, 0.113, and 0.052 ppm for ortho-DNB, para-DNB, NH, and methine protons, respectively (Table 3).

Table 2. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) Nonequivalences (ΔΔδ = |δR – δS|, ppm) of 1–5 (30 mM) and 9–13/DABCO (30 mM, 1:1) in the presence of 1 equiv of BTDA or TMA.

|

BTDA |

TMA |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pDNBa | oDNBb | NH | CHc | pDNBa | oDNBb | NH | CHc | |

| 1 | 0.141 | 0.186 | 0.210 | 0.043 | 0.045 | 0.071 | 0.076 | 0.003 |

| 2 | 0.041 | 0.060 | 0.021 | 0.008 | 0.021 | 0.028 | 0.036 | 0.006 |

| 3 | 0.078 | 0.106 | 0.009 | 0.005 | 0.036 | 0.049 | n.d.d | |

| 4 | 0.147 | 0.219 | 0.047 | 0.034 | 0.028 | 0.056 | 0.009 | |

| 5 | 0.243 | 0.324 | 0.113 | 0.028 | 0.072 | 0.126 | 0.012 | n.d.d |

| 9 | 0.089 | 0.169 | 0.042 | 0.050 | 0.021 | 0.047 | n.d.d | |

| 10 | 0.216 | 0.247 | 0.173 | 0.049 | 0.079 | 0.129 | 0.010 | 0.034 |

| 11 | 0.180 | 0.260 | 0.053 | 0.080 | 0.076 | 0.123 | 0.014 | n.d.d |

| 12 | 0.145 | 0.202 | 0.045 | 0.096 | 0.061 | 0.087 | 0.030 | 0.003 |

| 13 | 0.174 | 0.253 | 0.074 | 0.081 | 0.090 | 0.124 | 0.079 | 0.035 |

para-Proton of the DNB moiety.

ortho-Protons of the DNB moiety.

Methine proton of the chiral center.

Not determined.

Table 3. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) Nonequivalences (ΔΔδ = |δR – δS|, ppm) of 10 or 11/DABCO (1:1) in the presence of BTDA or TMA at Different Molar Ratios and Concentrations.

| ΔΔδ of 10 |

ΔΔδ of 11 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [sub] (mM) | CSA/sub molar ratio | BTDA | TMA | BTDA | TMA | |

| 15 | 1:1 | 0.185 | 0.058 | 0.167 | 0.054 | pDNBa |

| 0.208 | 0.094 | 0.239 | 0.086 | oDNBb | ||

| 0.146 | 0.024 | 0.044 | 0.014 | NH | ||

| 0.055 | 0.024 | 0.075 | 0.001 | CHc | ||

| 15 | 2:1 | 0.247 | 0.096 | 0.082 | pDNBa | |

| 0.294 | 0.156 | 0.132 | oDNBb | |||

| 0.172 | 0.045 | 0.025 | NH | |||

| 0.060 | 0.039 | 0.004 | CHc | |||

| 5 | 1:1 | 0.140 | 0.016 | 0.139 | pDNBa | |

| 0.159 | 0.027 | 0.194 | oDNBb | |||

| 0.113 | 0.014 | 0.032 | NH | |||

| 0.052 | - | 0.060 | CHc | |||

para-Proton of the DNB moiety.

ortho-Protons of the DNB moiety.

Methine proton of the chiral center.

Not determined.

Then CSA/substrate/DABCO (substrate/DABCO 1:1, 15 mM) solutions containing 1 equiv of dimeric CSA BTDA or 2 equiv of monomeric TMA were compared (Table 3). Adding 2 equiv of TMA to the 10/DABCO mixture increased the nonequivalences of the ortho- and para- protons of DNB moiety of 10 to 0.156 and 0.096 ppm, respectively (Table 3). Additionally, 1 equiv of BTDA at 15 mM caused larger nonequivalences, thus confirming the existence of cooperative effects involving the two thiourea chains of the dimeric structure of BTDA in the interaction with the substrate.

To go deeper into this aspect, complexation stoichiometries of the systems (R)-10/BTDA/DABCO and (S)-10/BTDA/DABCO were compared via Job’s method26 (Figure S6 in the Supporting Information). In both cases, a well-defined maximum at the 0.5 mole fraction, corresponding to a 1:1 stoichiometry, was found. It is noteworthy that additional independently interacting units of BTDA should have caused a 1:2 complexation stoichiometry.

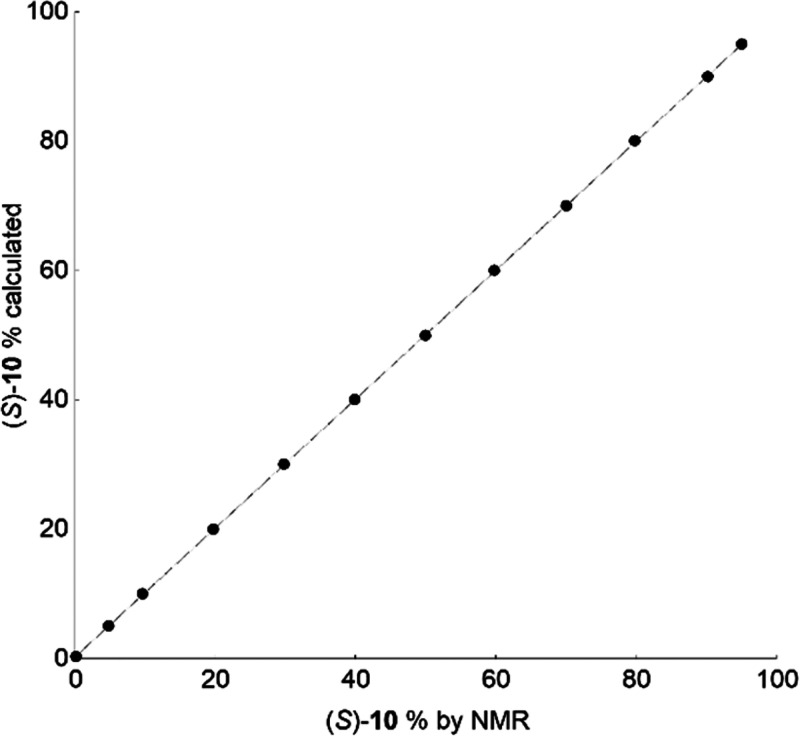

1H NMR Enantiomeric Purity Determination

The bis-thiourea derivative BTDA was employed in the quantitative determination of the enantiomeric composition of enantiomerically enriched samples of 10 by integrating amide resonances of the two enantiomers in the ternary mixture 10/BTDA/DABCO (1:1:1) at 30 mM. Values from the integration were in very good agreement with the values obtained on the basis of the knowledge of the volumes of stocks solutions employed for the preparation of NMR samples, as shown in Figure 4 (Tables S2). The good agreement was also confirmed in the analysis of mixtures with different contents of enantiomers for 9–13 (enantiomeric excess of 98%, Table S3 in the Supporting Information).

Figure 4.

BTDA (30 mM)/DABCO (1:1) mixtures containing an equimolar amount of enantiomerically enriched 10 showing the correlation between the percentage of (S)-10, calculated from the mixed volumes of pure enantiomer stock solutions, and from that from the NMR integration of NH signals of 10.

13C NMR Enantiodiscrimination Experiments

Usually, enantiodifferentiation experiments are performed by observing nuclei with a high sensitivity (1H, 19F, 31P, etc.), whereas low-sensitivity nuclei such as 13C and 15N are avoided. However, during the past decades27−31 technical advances have led to the reconsideration of observing such nuclei, which instead show great advantages in terms of spectral resolution in X{1H} decoupled spectra. As a matter of fact, in enantiodiscrimination experiments at the same signal-to-noise ratio, enantiomeric quantitative determinations by 13C{1H} NMR are more accurate than those by 1H NMR due to the lower line width of 13C{1H} NMR resonances.

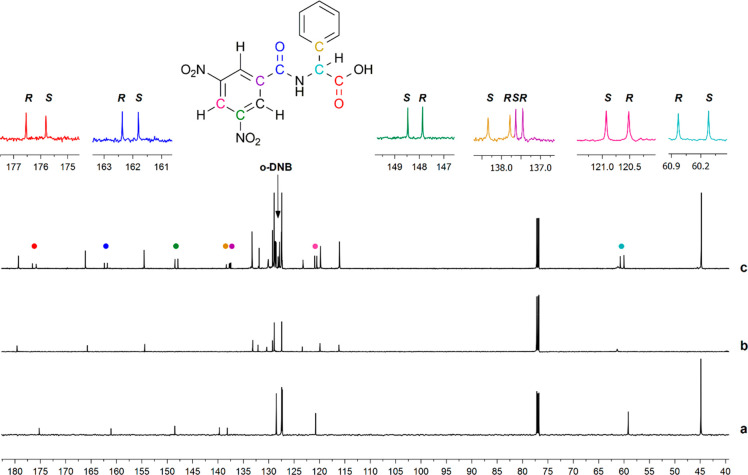

To evaluate the possibility of using 13C nuclei observation in enantiodiscrimination experiments based on CSA BTDA, 13C{1H} NMR spectra of 10/DABCO (1:1), BTDA, and 10/BTDA/DABCO (1:1:1) were compared (Figure 5). 13C NMR signals of the ternary mixtures were characterized by means of the assignment of the protonated and quaternary carbons in 2D heteronuclear correlation experiments (HSQC and HMBC, Figures S7 and S8 in Supporting Information, respectively).

Figure 5.

13C{1H} NMR spectra (150 MHz, 30 mM, 25 °C, CDCl3) of (a) the racemic 10/DABCO equimolar mixture, (b) BTDA, and (c) the racemic 10/BTDA/DABCO equimolar mixture.

Remarkably high enantiodifferentiations were detected in the ternary mixture, and nonequivalence data are collected in Table 4. Nonequivalence values up to 0.7 ppm, the best separations, were detected for the carbonyl quaternary carbons of carboxyl and amide functions as well as for the C–NO2 carbons. Like in the case of 10, remarkably high differentiations of 13C nuclei were detected in the ternary mixtures containing the other N-3,5-dinitrobenzoyl amino acid derivatives 11 and 13 with free carboxyl functions, with better nonequivalences for the carbonyl moieties, stereogenic carbon, para-DNB carbon, and quaternary carbons directly bound to the nitro groups (Table 4).

Table 4. 13C NMR (150 MHz, 30 mM, 25 °C, CDCl3) Nonequivalences of Derivatives 10, 11, and 13 in the Presence of Equimolar Amounts of BTDA/DABCO.

| 10 | 11 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| –CO–OH | 0.73 | 0.20 | 0.08 |

| –C–H | 0.71 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| –CO–NH– | 0.55 | 0.44 | 0.23 |

| ortho-DNB | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.21 |

| para-DNB | 0.41 | 0.35 | 0.38 |

| –C–NO2 | 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.53 |

| –C–CH– | 0.56 | 0.19 | 0.42 |

| –C–CONH– | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.18 |

Enantiodifferentiation Mechanism

To ascertain the molecular basis of the enantiodiscriminating efficiency of 10, an accurate NMR investigation on the diastereomeric solvates (R)-10/BTDA/DABCO and (S)-10/BTDA/DABCO was carried out.

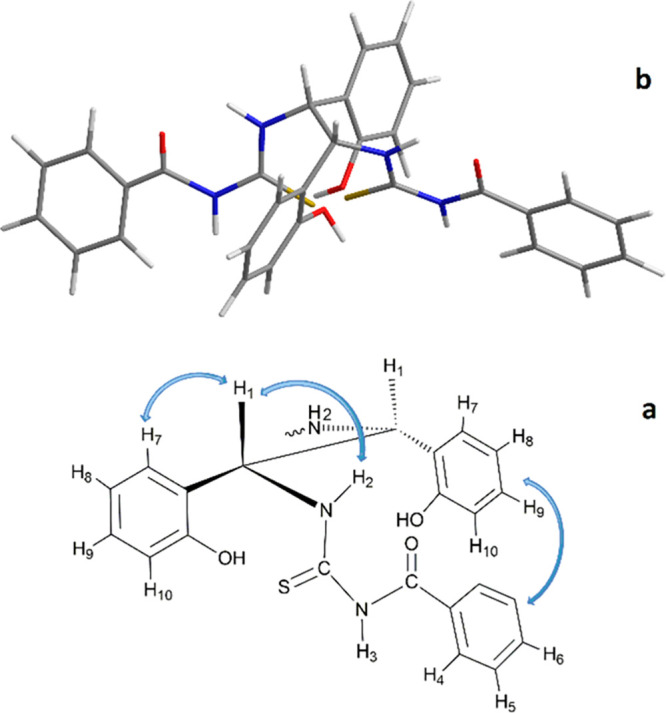

CSA Conformation

The conformation of pure CSA (30 mM) was defined by measuring through-space dipolar interactions by 1D and 2D ROE experiments. Due to the symmetry of the system, a unique set of signals was detected for both units that constitute dimeric CSA, which made the interpretation of the ROEs quite difficult. Interestingly, the inter-ROE H7–H1 was more intense with respect to the H7–H8 one (Figure S9b in Supporting Information), in accordance with the fact that the H7 proton of each phenolic moiety must lie in the proximity of the two cisoid C–H1 bonds in conformation A (depicted in Figure 6a). N–H2 protons belonging to the thiourea moiety (Figure S10 in Supporting Information) produced an intense ROE at the methine proton H1 frequency and a very weak dipolar interaction with H3 for which an intense ROE at the frequency of proton H4 of the proximal benzoyl moiety was found, which is in accordance with the conformation of the thiourea chain having cisoid and transoid N–H2/C–H1 and N–H2/N–H3 bonds, respectively, and an almost coplanar N–H3 and benzoyl moiety. Therefore, a cleft structure endowed with two major and minor grooves (Figure 6b) that are stabilized by an extended network of hydrogen-bond donor–hydrogen-bond acceptor interactions is supported by NMR data.

Figure 6.

(a) Sawhorse projection of BTDA along the C(NH)–C(NH) bond in the cisoid arrangement and (b) 3D representation of BTDA according to NMR data. The blue arrows indicate ROE effects.

10/BTDA/DABCO

Regarding ternary mixtures 10/BTDA/DABCO, ROE effects were detected between H9 and H10 (superimposed with H7) of BTDA and Ho-DNB of 10 (Figure 7b and d) in accordance with proximity of the electron-rich phenol of CSA and the electron-poor dinitrobenzoyl ring of 10. Interestingly, any ROEs between Hp-DNB and phenolic protons were not detected (Figure 7f), favoring an edge-to-edge interaction rather than π–π stacking between the two aromatic moieties. Moreover, weak ROE effects between the protons Ho of the phenyl ring of 10 and H10 of the CSA were detected (Figure 7g). Dipolar interactions between phenolic protons of CSA and both phenyl and DNB groups of 10 can only coexist if the two groups are in the proximity of two distinct phenolic moieties of the CSA, with 10 bisecting the two major grooves originated by BTDA.

Figure 7.

(a) 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3, 30 mM, 25 °C) spectrum of the (R)-10/BTDA/DABCO equimolar mixture. 1D-ROESY experiments (mix 0.4 s) with the selective perturbation of (b) H7 + H9, (c) H8, (d) H10, (e) CH, (f) NH, (g) Ho, (h) Ho-DNB, and (i) Hp-DNB protons.

The CSA–substrate interaction was mediated by DABCO. As a matter of fact, DABCO protons produced relevant dipolar interactions (Figure S11 in Supporting Information) with amino acid protons, the π-acidic aromatic moiety of the CSA (benzoyl group), and its π-donor aromatic moiety (o-hydroxyphenyl moiety), which means that the base lies between all of these groups. This mechanism is also reasonable in consideration of the complexation stoichiometry. Due to the presence of the two nitrogens of DABCO, we could expect that 1 equiv of base binds 2 equiv of the amino acid derivative, giving rise at least to a certain population of 1:2 CSA/substrate complexes. However, we found a pure 1:1 complexation stoichiometry (Figure S6 in Supporting Information), which is in agreement with a favored interaction mechanism where one nitrogen of DABCO binds the carboxylate of the amino acid and the other one binds the acidic hydroxyl of the phenolic moiety. Interestingly, the intermolecular dipolar interaction with the amide proton of 10 was negligible, confirming that, as expected, the carboxyl function of 10 is involved in the interaction with the base.

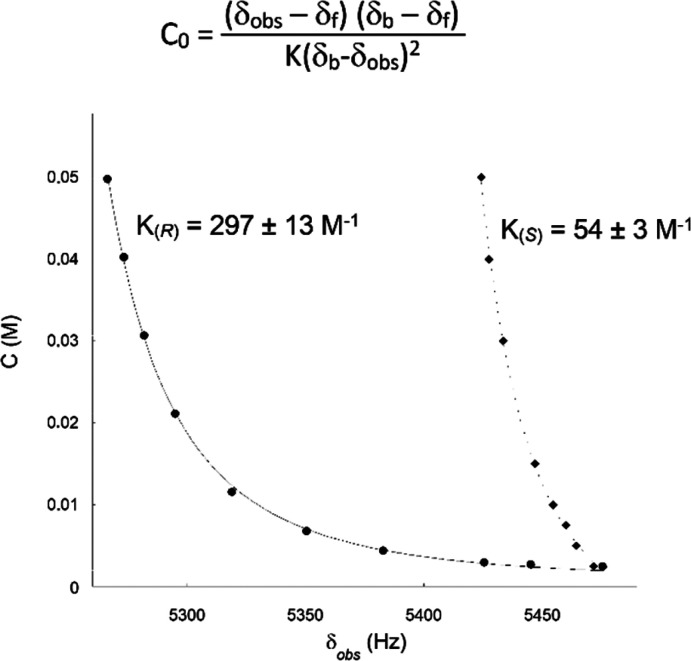

Regarding CSA, a remarkably high ROE was detected between DABCO and the H10 phenolic proton adjacent to the OH group together with other non-negligible ROEs with protons of the benzoyl moiety of BTDA, in contrast to the negligible ROEs at the frequencies of NH protons of CSA. Therefore, it seems that DABCO is located at the central part of the cleft structure of the CSA, interacting mainly at its more acidic polar groups, i.e., phenolic hydroxyls, but simultaneously interacting with the carboxylate function of the enantiomeric substrates. In this way, the two enantiomers are both anchored to CSA through DABCO and bisect its major grooves. Interestingly, dipole–dipole interactions were qualitatively similar for both (R)- and (S)-enantiomers, but the interactions were weaker for the latter (Figures S11 and S12 in Supporting Information, respectively). Accordingly, the association constants, which calculated on the basis of the 1:1 stoichiometry using dilution data32 (Figure 8), were 297 ± 13 and 54 ± 3 M–1 for the (R)-10/BTDA/DABCO and (S)-10/BTDA/DABCO complexes, respectively.

Figure 8.

Nonlinear fitting of dilution data from the observed chemical shift of the para-DNB proton dependence on the concentration of 10 in equimolar mixtures of (R)-10/BTDA/DABCO (1:1:1) and (S)-10/BTDA/DABCO (1:1:1). δobs, δb, and δf in equation are the observed chemical shift and the chemical shift in the bound state and the free state, respectively.

Conclusion

Nowadays, a major contribution to the design of new CSAs comes from receptors that are specifically oriented to increment the efficiency or versatility of enantiodiscrimination, avoiding complex derivatization procedures to analyze the enantiomeric substrates. Dimeric thiourea CSA BTDA is well-channelled in this trend, constituting a new tweezer-like artificial receptor endowed with a very high enantiodiscriminating ability toward N-3,5-dinitrobenzoyl derivatives of amino acids. The CSA is able to anchor the enantiomeric substrates through a complex network of hydrogen-bond donor and hydrogen-bond acceptor interactions and to cap them using a pool of aromatic moieties, which exert relevant anisotropic effects and hence cause sensitive changes of the chemical shifts. Among the aromatic moieties of the CSA, an especially relevant dual role is played by the phenolic units by virtue of the presence of an acidic hydroxy group and the electron-rich character of the aromatic ring, creating attractive interactions with the electron poor 3,5-dinitrophenyl group of derivatized enantiomers. The use of DABCO as a solubilizing additive makes it possible to employ the operatively simple derivatization of the sole amino group of the amino acid, leaving their carboxyl function underivatized. DABCO, beyond its role as solubilizing agent, actively assists the stabilization of the diastereomeric solvates by acting as a bridge, which enhances the hydrogen-bond donor character of the most acidic functional groups, i.e., the OH of CSA and the carboxyl function of the amino acid derivative. On this basis, the two enantiomers are bound by the CSA always preserving two kinds of attractive interactions that respectively occur at their carboxyl function and 3,5-dinitrophenyl moiety, the strengths of which are affected by the interchange of the two groups bound to the chiral center in the (R)-enantiomer with respect to the (S)-enantiomer. Hence, chiral discrimination is guaranteed.

Experimental Section

Materials

All commercially available substrates (6–8), reagents and solvents were purchased from Aldrich and used without further purification. Tetrahydrofuran (THF) was dried by distillation on potassium. Deuterated chloroform (CDCl3) used for the NMR analysis was acquired by Deutero GmbH. Derivatives 1–5 and 9–13 were prepared as described in refs (33) and (25), respectively. The NMR characterization is reported in ref (25).

General Methods

1H and 13C{1H} NMR measurements were carried out on a spectrometer operating at 600 and 150 MHz for 1H and 13C nuclei, respectively. The samples were analyzed in a CDCl3 solution. 1H and 13C chemical shifts were referenced to tetramethylsilane (TMS) as the secondary reference standard, and the temperature was controlled (25 °C). For all the 2D NMR spectra, the spectral width used was the minimum required in both dimensions. The gCOSY (gradient correlation spectroscopy) and TOCSY (total correlation spectroscopy) maps were recorded using a relaxation delay of 1 s and 256 increments of four transients, each with 2K-points. For TOCSY maps, a mixing time of 80 ms was set. The 2D-ROESY (rotating-frame overhauser enhancement spectroscopy) maps were recorded using a relaxation time of 5 s and a mixing time of 0.4 s, and 256 increments of 16 transients of 2K-points each were collected. The 1D-ROESY spectra were recorded using a selective inversion pulse with transients ranging from 256 to 1024, a relaxation delay of 5 s, and a mixing time of 0.5 s. The gHSQC (gradient heteronuclear single quantum coherence) and gHMBC (gradient heteronuclear multiple bond correlation) spectra were recorded with a relaxation time of 1.2 s and 128–256 increments with 32 transients, each owith 2K-points. The gHMBC experiments were optimized for a long-range coupling constant of 8 Hz. 1H NMR and 13C{1H} NMR characterization data, reported below, refer to numbered protons and carbons from the chemical structures reported in Figures S13 and S14 in Supporting Information.

Synthesis of BTDA

Benzoyl isothiocyanate (0.653 g, 4 mmol, 2 equiv) was added to DA (0.489 g, 2 mmol, 1 equiv) in CH2Cl2 (20 mL) at room temperature under a nitrogen atmosphere. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h and monitored by 1H NMR. The solvent was removed by evaporation under vacuum to afford chemically pure BTDA in a nearly quantitative yield.

BTDA. White amorphous solid (1.126 g, 1.97 mmol, 98.7% yield), mp 164–166 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): δ 11.99 (d, 1H, J = 2.5 Hz), 9.00 (s, 1H), 8.14 (br s, 1H), 7.77 (d, 2H, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.54 (t, 1H, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.42 (t, 2H, J = 7.6 Hz); 7.09 (d, 1H, J = 7.5 Hz), 6.98 (t, 1H, J = 7.5 Hz), 6.78 (d, 1H, J = 7.5 Hz), 6.72 (d, 1H, J = 2.5 Hz), 6.62 (t, 1H, J = 7.5 Hz). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz): δ 179.6, 165.8, 154.5, 133.2, 132.1, 130.4, 129.3, 128.9, 127.5, 123.4, 119.9, 116.2, 61.4. Anal. Calcd for C30H26N4S2O4: C, 63.14; H, 4.59; N, 9.82. Found: C, 63.01; H, 4.57; N, 9.87.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.joc.1c00340.

Nonequivalences of NH and CH protons of amino acid derivatives, 1D ROESY and TOCSY spectra, 1H complexation shifts of amino acid derivatives, enantiodiscrimination of 10, stoichiometry and enantiomeric purity determinations, 2D gHSQC maps, and 1H NMR spectra (PDF)

Author Contributions

† The authors contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Wenzel T. J.Differentiation of Chiral Compounds Using NMR Spectroscopy, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons. Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel T. J. Chiral Derivatizing Agents, Macrocycles, Metal Complexes, and Liquid Crystals for Enantiomer Differentiation in NMR Spectroscopy. Top. Curr. Chem. 2013, 341, 1–68. 10.1007/128_2013_433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzano F.; Uccello-Barretta G.; Aiello F.. Chiral Analysis by NMR Spectroscopy: Chiral Solvating Agents. In: Chiral Analysis: Advances in Spectroscopy, Chromatography and Emerging Methods, 2nd ed.; Polavarapu P. L., Ed.; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp 367–427. [Google Scholar]

- Uccello-Barretta G.; Balzano F. Chiral NMR Solvating Additives for Differentiation of Enantiomers. Top. Curr. Chem. 2013, 341, 69–131. 10.1007/128_2013_445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel T. J.; Thurston J. E. Enantiomeric discrimination in the NMR spectra of underivatized amino acids and α-methyl amino acids using (+)-(18-crown-6)-2,3,11,12-tetracarboxylic acid. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 3769–3772. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)00499-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari D.; Bandyopadhyay P.; Suryaprakash N. Discrimination of α-Amino Acids Using Green Tea Flavonoid (−)-Epigallocatechin Gallate as a Chiral Solvating Agent. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 2373–2378. 10.1021/jo3025016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv C.; Feng L.; Zhao H.; Wang G.; Stavropoulos P.; Ai L. Chiral discrimination of α-hydroxy acids and N-Ts-α-amino acids induced by tetraaza macrocyclic chiral solvating agents by using 1H NMR spectroscopy. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 1642–1650. 10.1039/C6OB02578A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G.; Lv C.; Li Q.; Ai L.; Zhang J. Enantiomeric discrimination of α-hydroxy acids and N-Ts-α-amino acids by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015, 56, 6742–6746. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2015.10.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S.; Wang G.; Ai L. Synthesis of macrocycles and their application as chiral solvating agents in the enantiomeric recognition of carboxylic acids and α-amino acid derivatives. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2013, 24, 480–491. 10.1016/j.tetasy.2013.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W.; Shen X.; Ma F.; Li Z.; Zhang C. Chiral amino alcohols derived from natural amino acids as chiral solvating agents for carboxylic acids. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2008, 19, 1193–1199. 10.1016/j.tetasy.2008.04.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z.; Zhong C.; Wu X.; Fu E. Amphiphilic chiral receptor as efficient chiral solvating agent for both lipophilic and hydrophilic carboxylic acids. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 3385–3390. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.03.113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K.; Iwashita T.; Sasaki C.; Takahashi H. Ring-expanded chiral rhombamine macrocycles for efficient NMR enantiodiscrimination of carboxylic acid derivatives. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2014, 25, 602–609. 10.1016/j.tetasy.2014.03.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.; Fan H.; Yang S.; Bian G.; Song L. Chiral sensors for determining the absolute configurations of α-amino acid derivatives. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 8311–8317. 10.1039/C8OB01933A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunal S. E.; Tuncel S. T.; Dogan I. Enantiodiscrimination of carboxylic acids using single enantiomer thioureas as chiral solvating agents. Tetrahedron 2020, 76, 131141. 10.1016/j.tet.2020.131141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S.; Okuno M.; Asami M. Differentiation of enantiomeric anions by NMR spectroscopy with chiral bisurea receptors. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 213–222. 10.1039/C7OB02318A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian G.; Yang S.; Huang H.; Zong H.; Song L. A bisthiourea-based 1H NMR chiral sensor for chiral discrimination of a variety of chiral compounds. Sens. Actuators, B 2016, 231, 129–134. 10.1016/j.snb.2016.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cios P.; Romanski J. Enantioselective recognition of sodium carboxylates by an 1,8-diaminoanthracene based ion pair receptor containing amino acid units. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 3866–3869. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.07.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bian G.; Fan H.; Huang H.; Yang S.; Zong H.; Song L.; Yang G. Highly Effective Configurational Assignment Using Bisthioureas as Chiral Solvating Agents in the Presence of DABCO. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 1369–1372. 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulatowski F.; Jurczak J. Chiral Recognition of Carboxylates by a Static Library of Thiourea Receptors with Amino Acid Arms. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 4235–4243. 10.1021/acs.joc.5b00403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian G.; Fan H.; Yang S.; Yue H.; Huang H.; Zong H.; Song L. A Chiral Bisthiourea as a Chiral Solvating Agent for Carboxylic Acids in the Presence of DMAP. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 9137–9142. 10.1021/jo4013546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trejo-Huizar K. E.; Ortiz-Rico R.; Peña-González M. d. L. A.; Hernández-Rodriguez M. Recognition of chiral carboxylates by 1,3-disubstituted thioureas with 1-arylethyl scaffolds. New J. Chem. 2013, 37, 2610–2613. 10.1039/c3nj00644a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foreiter M. B.; Gunaratne H. Q. N.; Nockemann P.; Seddon K. R.; Stevenson P. J.; Wassell D. F. Chiral thiouronium salts: Synthesis, characterisation and application in NMR enantio-discrimination of chiral oxoanions. New J. Chem. 2013, 37, 515–533. 10.1039/C2NJ40632B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Rodrıguez M.; Juaristi E. Structurally simple chiral thioureas as chiral solvating agents in the enantiodiscrimination of α-hydroxy and α-amino carboxylic acids. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 7673–7678. 10.1016/j.tet.2007.05.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kyne G. M.; Light M. E.; Hursthouse M. B.; de Mendoza J.; Kilburn J. D. Enantioselective amino acid recognition using acyclic thiourea receptors. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 2001, 1258–1263. 10.1039/b102298a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Recchimurzo A.; Micheletti C.; Uccello-Barretta G.; Balzano F. Thiourea Derivative of 2-[(1R)-1-Aminoethyl]phenol: A Flexible Pocket-like Chiral Solvating Agent (CSA) for the Enantiodifferentiation of Amino Acid Derivatives by NMR Spectroscopy. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 5342–5350. 10.1021/acs.joc.0c00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Job P. Formation and Stability of Inorganic Complexes in Solution. Ann. Chim. 1928, 9, 113–203. [Google Scholar]

- Lankhorst P. P.; van Rijn J. H. J.; Duchateau A. L. L. One-Dimensional 13C NMR is a Simple and Highly Quantitative Method for Enantiodiscrimination. Molecules 2018, 23, 1785.and references cited therein. 10.3390/molecules23071785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva M. S. Recent Advances in Multinuclear NMR Spectroscopy for Chiral Recognition of Organic Compounds. Molecules 2017, 22, 247.and references cited therein. 10.3390/molecules22020247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Trujillo M.; Parella T.; Kuhn L. T. NMR-aided differentiation of enantiomers: Signal enantioresolution. Anal. Chim. Acta 2015, 876, 63–70. 10.1016/j.aca.2015.02.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Trujillo M.; Monteagudo E.; Parella T. 13C NMR Spectroscopy for the Differentiation of Enantiomers Using Chiral Solvating Agents. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 10887–10894. and references cited therein. 10.1021/ac402580j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudzińska-Szostak E.; Górecki L.; Berlicki L.; ŚLepokura K.; Mucha A. Zwitterionic Phosphorylated Quinines as Chiral Solvating Agents for NMR Spectroscopy. Chirality 2015, 27, 752–760. 10.1002/chir.22494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uccello-Barretta G.; Balzano F.; Caporusso A. M.; Iodice A.; Salvadori P. Permethylated/β-cyclodextrin as Chiral Solvating Agent for the NMR Assignment of the Absolute Configuration of Chiral Trisubstituted Allenes. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 2227–2231. 10.1021/jo00112a050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balzano F.; Uccello-Barretta G. Chiral mono- and dicarbamates derived from ethyl (S)-lactate: convenient chiral solvating agents for the direct and efficient enantiodiscrimination of amino acid derivatives by 1H NMR spectroscopy. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 4869–4875. 10.1039/D0RA00200C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.