Abstract

With a continuous threat of antimicrobial resistance on human health worldwide, efforts for new alternatives are ongoing for the management of bacterial infectious diseases. Natural products of land and sea, being conceived to be having fewer side effects, pose themselves as a welcome relief. In this respect, we have taken a scaffolded approach to unearthing the almost unexplored chemical constituents of Malaysian red seaweed, Gracilaria edulis. Essentially, a preliminary evaluation of the ethyl acetate and acetone solvent extracts, among a series of six such, revealed potential antibacterial activity against six MDR species namely, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella enterica, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Streptococcus pyogenes, and Bacillus subtilis. Detailed analyses of the inlying chemical constituents, through LC-MS and GC-MS chromatographic separation, revealed a library of metabolic compounds. These were led for further virtual screening against selected key role playing proteins in the virulence of the aforesaid bacteria. To this end, detailed predictive pharmacological analyses added up to reinforce Eplerenone as a natural alternative from the plethora of plausible bioactives. Our work adds the ongoing effort to re-discover and repurpose biochemical compounds to combat the antimicrobial resistance offered by the Gram-positive and the -negative bacterial species.

Keywords: antimicrobial resistance, Gracilaria edulis, red seaweed, bioactive compounds, virtual screening, eplerenone

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has become a critical concern for public health worldwide. Numerous pathogens have started to evolve and progressively develop resistance toward currently in-practice antibiotics, thereby adding, in essence, to global morbidity and mortality for the diseases caused by these pathogens (Subramani et al., 2017). Besides such evolutionary constraints, multidrug resistance (MDR) in bacterial strains, also spreads from irrational usages of antibiotics (Shrestha et al., 2018). In this regard, several pathogens have posed resistance toward different types of antibiotics. Notable among them is vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, clarithromycin-resistant Helicobacter pylori, fluoroquinolone-resistant Salmonella and Campylobacter spp., cephalosporin- and fluoroquinolone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae and carbapenem-resistant and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) creating Enterobacteriaceae (World Health Organization [WHO], 2017). Moreover, the development of new antibiotics has slowed down over the past few decades while the emergence rate of resistant pathogens is high (Ventola, 2015). This necessitates an immediate exploration of novel antibacterials to combat the MDR threats.

To unearth novel antimicrobials for clinicians and pharmacological industries, efforts are focused on exploring the natural products from land and sea. This is due to the fact that natural products, with effective antimicrobial potency, have been proven successful in sufficiently reducing the worldwide load of infectious illnesses (Mérillon and Rivière, 2018). They are, therefore, used as alternative agents to eradicate the extensive use of synthetic drugs and related antibiotics (Cheesman et al., 2017). In fact, marine organisms, such as seaweeds and diatoms, are considered as novel sources of bioactive constituents which produce a vast diversity of secondary metabolites, revealing a broad spectrum of biological actions (El Shafay et al., 2016). In this context, Ismail et al. (2016) have screened different types of seaweeds, namely, green Cladophora pellucida, brown Padina tetrastromatica, and red Laurencia papillosa for the isolation of antimicrobial agents.

In line with the exploration of seaweeds for novel antimicrobials, secondary metabolites like phlorotannins, acrylic acid, terpenoids, phenolic compounds, steroids, halogenated ketones, alkaline, fatty acid and cyclic polysulphides have been unearthed (Cheung et al., 2015; Khelil-Radji et al., 2017). These bioactive constituents have biological potentials including dietary, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, anti-ageing, antibacterial, antioxidant, anticancer, anticoagulation, anti-malarial and anti-proliferation (Chan et al., 2015; Agregán et al., 2017). Moreover, growing evidence has revealed that red seaweeds contain a broad spectrum of secondary metabolites with antibacterial potentials (Kasanah et al., 2019). In fact, in Asian countries, red seaweeds are generally used as food materials and find extensive usages as seasonings, sushi wrappings, condiments, vegetables, noodles, and for polysaccharide production for the food and pharmaceutical industries (Seedevi et al., 2017). In this regard, the red seaweed, Gracilaria edulis, has attracted extensive consideration due to its biological and pharmacological applications and several therapeutic benefits.

With a broad range of biological activities of G. edulis, encompassing antibacterial, anticoagulant, antidiabetic, antioxidant, antiproliferative and anti-inflammatory activities (De Almeida et al., 2011), they have been considered as likely natural functional foods (Rosemary et al., 2019). In fact, few researchers have even reported its in vitro antibacterial activities. For instance, Hemasudha et al. (2019) determined the antibacterial activity of the methanol extract of G. edulis against S. aureus and P. aeruginosa, having a significant activity, with inhibition zone of 18mm and 19mm being recorded, respectively. Similarly, Umakanthan et al. (2017) described the antibacterial effects of the crude extract of G. edulis against S. aureus and Escherichia coli. Moreover, Kasanah et al. (2019) reported the antibacterial activity against bacterial fish pathogens like Vibrio fluvialis and Vibrio compbelii. Again, Arulkumar et al. (2018) confirmed the methanol extract of G. edulis to have remarkable inhibitory activity toward Bacillus subtilis, S. aureus, E. coli and Pseudomonas fluorescens.

In this study, thus, we have detailed a stepwise approach of determining the efficacy of different solvent-based crude extracts of Malaysian G. edulis against clinically important MDR bacterial species namely, Klebsiella pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, Salmonella enterica, MRSA, Streptococcus pyogenes and B. subtilis. Further chemical profiling of the extracts through LC-MS and GC-MS revealed their potential chemical determinants. These were screened virtually and pharmacologically to unveil potential novel bioactive compounds. To this end, a molecular dynamics simulation by our shortlisted bioactive compounds, Eplerenone, on selected virulent protein targets of the aforementioned bacteria, revealed its high potential as an effective antibacterial compound, targeting both the gram-positive and the -negative pathogens.

Materials and Methods

Collection of Materials

Solvents

For crude extractions, HPLC grade organic solvents with increasing polarities were used. These comprised chloroform (99.9%, Sigma-Aldrich, LiChrosolv, Malaysia), ethyl acetate, acetone (99.5% Chemiz, Malaysia), ethanol, methanol (99.8%, ChemAR, Systerm, Malaysia) and double-distilled Milli-Q Type 1 water (MilliporeMerck, Germany). For LC-MS and GC-MS analyses, however, MS grade solvents were used.

Seaweeds

Healthy specimens of Gracilaria edulis were collected from Pantai Morib, Selangor, Malaysia.

Bacterial Strains

A total of six clinical isolates, including three each of Gram-positive and Gram-negative, were used in the study. These comprised Bacillus subtilis (ATCC-11774), Streptococcus pyogenes (ATCC-49399), methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (MTCC-381123), Klebsiella pneumoniae (ATCC-700603), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC-10145), and Salmonella enterica (ATCC-14028), these strains were received from the Department of Biological Sciences (DBS), School of Medical and Life Sciences, Sunway University, Malaysia. All these six bacterial strains were found to be resistant to at least five of the ten antibiotics tested for their resistivity/sensitivity profile and thus, considered to be multidrug resistant (Supplementary Table 1).

Crude Extracts Preparation

Extracts of G. edulis were prepared through two different approaches, namely, sequential and direct, following the procedure of Subermaniam et al. (2020). For the sequential process, the aforementioned solvents were used in the order of increasing polarity viz. chloroform < ethyl acetate < acetone < ethanol < methanol < water. For the direct extracts, ethyl acetate and acetone were used only. Essentially, for both approaches, the seaweeds were rinsed sequentially with seawater followed by normal tap and then double distilled water to eradicate dirt and impurities. Clean samples were then dried using a freeze-dryer and later crushed into fine granule powder using an electric grinder. Different fractions of extracts were prepared using 10 grams of each powder to dissolve them in 100 mL of the above-mentioned solvents. All the prepared mixtures were made homogeneous using a rotating shaker (Yihder LM-530D, Shaker, Taiwan) for 24 h and finally centrifuged (Eppendorf 5810 R Centrifuge, Germany) at 4000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C to separate the supernatant. Each of the clear supernatants of the extracts was concentrated via a Rotary evaporator (Thermo Fisher Scientific EYELA N-1200A Rotary Evaporator, Tokyo). A further concentration using a vacuum concentrator (LaboGene, Brigachtal, Germany) was done to obtain a viscous liquid for storage at 4°C and future experiments.

Potential in vitro Antibacterial Activities

Disc-Diffusion Test

All the microorganisms were tested for their response against the crude extract fractions (CEF) of G. edulis. Essentially, a loopful of inocula was swabbed on plates containing Mueller-Hinton Agar (MHA, Oxoid). This was followed by soaking 6 mm sterilized paper discs with different crude extract fractions and placing them on those plates to be incubated for 16 h at 37°C. Gentamicin having a concentration of 10 μg/disc served as a positive control along with DMSO (<1%) as solvent control. The activities of each of the CEF were recorded by measurement of the diameter of inhibition zones. All experiments were performed with technical triplicates, and twice, to render two biological duplicates.

Broth Dilution Assay

To assess the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of the CEF, broth dilution assay was used, following Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) measures. This was initiated by adding 5 μL of each CEF onto 96-well plates, containing 5 × 105 CFU/mL bacterial cells, to a range of final concentrations from 250 to 2000 μg/mL. These plates were incubated for 16 h at 37°C. Three different controls were maintained for each trial. These were Gentamicin (10 μg/mL) as the positive control, DMSO < 1% as solvent control and bacterial inoculum as the negative control. The MIC50 value was determined from the lowest concentration of the tested CEF, displaying inhibitory result toward the pathogens, as recorded through the Microplate reader (TECAN, Infinite-M200-PRO). Biological duplicates were used to confirm each trial having technical triplicates. The CEF of ethyl acetate (EA) and acetone (AC), having notable results, were utilized for further chromatographic separation analyses.

Statistical Tests

All the tests in the present study were performed in triplicates and the data obtained are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (S.D). The P-values were determined using student’s T-test, two-tailed distribution, where ∗ refers to P ≤ 0.05. These have been reflected in Tables 1, 2, Supplementary Figure 1, and Supplementary Tables 4, 5.

TABLE 1.

Antibacterial activity of G. edulis rhizome sequential and direct crude extracts via disc diffusion.

| Zones of Inhibition (mm) | ||||||

| Bacteria | P.C | S.C | EA | AC | EA(D) | AC(D) |

| B. subtilis | 32.00 ± 0.70 | − | − | − | 9.26 ± 0.52 | 7.00 ± 0.56 |

| MRSA | − | − | − | − | − | |

| S. pyogenes | − | − | − | − | − | |

| P. aeruginosa | − | − | − | − | − | |

| K. pneumoniae | − | − | − | 6.5 ± 0.42 | 6.8 ± 0.14 | |

| S. enterica | − | − | − | − | − | |

“−” no activity, P.C: positive control (Gentamicin 10 μg), SC: solvent control (DMSO < 1%), EA: ethyl acetate, AC: acetone, EA(D): ethyl acetate direct; AC(D): acetone direct. The data is expressed as the mean ± standard error of two independent experiments performed in technical triplicates.

TABLE 2.

MIC50 of the G. edulis sequential and direct extracts against all tested pathogens.

| MIC50 (μ g/mL) | ||||

| Microorganisms | EA | AC | EA(D) | AC(D) |

| B. subtilis | 2000 | 2000 | 250 | 250 |

| MRSA | ND | ND | 250 | 250 |

| S. pyogenes | ND | ND | 250 | 250 |

| P. aeruginosa | ND | 2000 | 250 | 250 |

| K. pneumonia | ND | ND | 250 | 250 |

| S. enterica | 2000 | ND | 1000 | 250 |

ND: not determined, AC: acetone, ET: ethanol, EA(D): ethyl acetate direct; AC(D): acetone direct. The illustrated MIC50 values are the lowest inhibitory concentrations achieved from two independent trials performed in triplicate.

Exploration of Chemical Constituents Through Chromatographic Analyses

Liquid Chromatography With Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS)

To gain a detailed understanding of the standard and novel chemical constituents of G. edulis, the EA and AC CEF were analyzed via LC-MS as per the method described by Yap et al. (2019). Systematic errors were eliminated by using reference solution along with the two ions, having m/z of 121.0508 and 92266.0097, being selected for mass calibration. To this end, the mass spectra for the chemical constituents for the said CEF were run against the database of NIST (National Institutes of Standard and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, United States) via the Mass Spectral Search Program-2009 version 2, for the documentation of homologous chemical compounds through the Agilent Mass-Hunter Qualitative Analysis B.05.00 software.

Gas Chromatography With Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

To gain a further understanding of the constituents in the CEF of the volatile solvents EA and AC, they were subjected to gas chromatographic followed by mass spectrometric analysis, using Agilent technologies model 7890B GC System coupled with Pegasus HT High Throughput TOFMS (Leco Corp., MI, The United States). Typically, an aliquot of an extract of 1ml was injected into the GC-MS apparatus. To this end, Agilent J&W HP-5MS analytic column comprising phenyl methyl siloxane and having the dimensions of length 30 m, Dia. 0.32 mm, Film, 0.25 μm, was used to separate components under an inert atmosphere of helium (1.5 mL/min). Additional standardized parameters utilized during the process comprised an initial oven temperature of 80°C (2 min) increased to 300°C at the rate of 3°C/min, a solvent delay time of 5 min, an inlet line temperature of 225°C, along with an ion source temperature of 250°C. Keeping a GC run time of sixty-four (64) mins, the mass spectra readings were taken at 70 eV along with an acquisition mode-scan of 20-1000 amu. Using a database of NIST libraries, these mass spectral results were interpreted and deciphered phytochemicals were documented.

In silico Analysis of Chemical Determinants on Selected Protein Targets

Database Searching and Model Acquisition

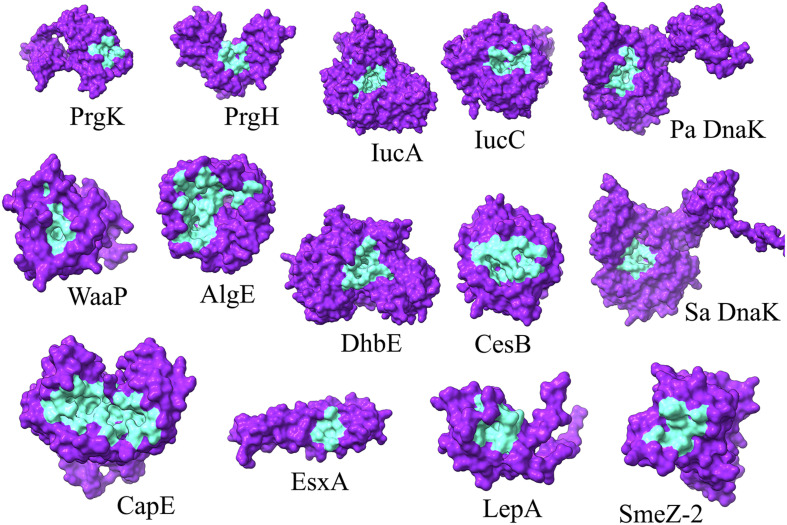

An estimation of the efficacies of the chemical determinants as antibacterials were obtained through their in silico analyses against target proteins of the six bacteria namely, S. enterica, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, Methicillin-Resistant S. aureus, S. pyogenes, and B. subtilis. In this regard, all virulence factors (VFs), occurring in the proteome of these bacteria were identified through the Virulence Factor Database (VFDB) (Liu et al., 2019). These VFs were being queried on Protein Data Bank (PDB) (Berman et al., 2000) to search for the available crystallized 3D structures of the proteins. Of these, two were selected from each bacteria of interest based on their physiological importance, the resolution, and sequence coverage for subsequent analyses, prioritizing the full-length crystallized proteins (Supplementary Table 2). Essentially, PrgK and PrgH for S. enterica, IucA and IucC for K. pneumoniae, WaaP and AlgE for P. aeruginosa, CapE and EsxA for S. aureus, LepA and SmeZ-2 for S. pyogenes as well as DhbE and CesB for B. subtilis, were selected. Moreover, validated homology models of the DnaK protein from P. aeruginosa and S. aureus were retrieved from a previous study (Asghar et al., 2020).

Prediction of Druggable Pockets

To identify the druggable pockets of each selected target protein for further structure-based screening, the 3D localization of the druggable pockets were predicted via a template-independent machine learning-based approach known as P2Rank (Krivák and Hoksza, 2018). The top-ranked predicted pockets, for each protein, were carried over for further analyses (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

3D representation of the P2Rank predicted druggable pockets (cyan) of selected proteins (indigo). Pa and Sa denote P. aeruginosa and S. aureus, respectively.

Structure-Based Virtual Screening of Chemical Compounds

The ability of each chemical compounds identified from prior chromatographic extractions to target the selected target proteins at the predicted druggable pockets were assessed via POAP, an in silico virtual screening pipeline powered by AutoDock 4.2 (Morris et al., 2009; Samdani and Vetrivel, 2018). Before the preparation of the ligands, those consisting of uncommon atoms, such as Silicon, Nickel, and Molybdenum, were excluded from further analyses to avoid inaccuracies. Moreover, ligands with more than 32 torsions were excluded as well as per AutoDock 4.2’s limitation. Following the POAP Ligand Preparation pipeline, SMILES notations of the ligands were converted into 3D structures. The MMFF94 force field was utilized for ligand optimization before virtual screening. Moreover, the best conformers were selected for each ligand from the 50 conformers generated through Weighted Rotor Search. Furthermore, the ligands were minimized via the conjugate gradient algorithm for 5000 steps. Before PDBQT file generation, physiological protonation states of the ligands were generated using the Chimera addH function (Pettersen et al., 2004).

For the target proteins, the PDB retrieved structures were cleaned before their PDBQT structures were generated, of which non-amino acid residues were removed and structural optimizations were carried out via the Chimera Dock Prep function (Pettersen et al., 2004). The grids, for virtual screening space of search, were set to encompass the docking pockets previously predicted by P2Rank (Supplementary Table 3).

Pharmacological Properties Screening

The chemical compounds were screened for drug-likeness rules and ADME properties via SwissADME (Daina et al., 2017). Essentially, the potentially druggable molecules were screened through pharmacological properties encompassing the properties of absorption, good gastrointestinal (GI) absorption, bad BBB permeability and non-P-glycoprotein (PGP) substrates. Moreover, concerning metabolism, we prioritize non-cytochrome P450 inhibitors to avoid adverse effects upon the co-administration of drugs. Furthermore, we have considered five rules for ascertaining the drug-likeness, namely, Lipinski, Ghose, Veber, Egan, and Muegge rules (Ghose et al., 1999; Egan et al., 2000; Muegge et al., 2001; Veber et al., 2002; Lipinski, 2004). Finally, higher bioavailability scores (Abbot Bioavailability Score) were preferred to ensure high drug efficiency (more than 10%) upon oral administration (Hann and Keseru, 2012).

Results

Variable Antibacterial Activity of Crude Extracts by Disc Diffusion

Disc diffusion technique was utilized to perform an initial screening for the antibacterial activities of the G. edulis different solvent-based CEF, prepared freshly, for all the trials. In each case, the solvent control (SC), DMSO, displayed no inhibition zone thereby establishing no antibacterial activity toward the tested bacterial species (TBS). Furthermore, none of the sequential CEF revealed activity toward the TBS (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 4), although, in the case of direct CEF, the scenario was fairly different. Extract EA(D) and AC(D) showed moderate ZOI toward B. subtilis and P. aeruginosa but did not show activity against the rest of the TBS (RTBS) (Table 1).

Antibacterial Screening of Crude Extracts via Broth Dilution

A broth dilution test was used for estimating the antibacterial activity of G. edulis crude extracts by calculating the inhibition percentage of each TBS. This, in turn, demonstrated the percentages of antibacterial effect of EA and AC, toward the TBS, at concentrations of 250 and 2000 μg/mL, respectively for direct and sequential CEF. In the case of sequential fraction, the extract from EA revealed the maximum percentage (60) of antibacterial activity against B. subtilis followed by S. enterica (50) while that from AC exhibited 50% effect toward B. subtilis and 60% against K. pneumoniae. No positive results were detected either against the RTBS (Supplementary Figures 1a-f) or for the other solvent CEF of chloroform (CF), ethanol (ET), methanol (MT), and aqueous (water, WT) toward all TBS (Supplementary Table 5). In direct extracts, CEF of EA displayed inhibition of 90% against B. subtilis along with 80, 70, 78, 75, and 72% for MRSA, S. pyogenes, P. aeruginosa, K. pneumonia and S. enterica, respectively. Remarkably, all TBS were inhibited by AC CEF and the percentage of antibacterial effects were 85, 82, 85, 89, 80, and 80, respectively, for B. subtilis, MRSA, S. pyogenes, P. aeruginosa, K. pneumonia and S. enterica (Supplementary Figures 1g-l). The MIC50 value of all the extracts are presented in Table 2.

The results obtained from the G. edulis CEF of EA and AC offered prominent antibacterial efficacy. This enabled us to use the CEF to further process them for the identification of bioactive compounds through LC-MS and GC-MS analyses.

Exploration of Chemical Components Through Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) Analysis

For a fast, mass-directed investigation of the probable chemical components of G. edulis, its EA and AC sequential CEF were exposed to LC-MS analysis (Supplementary Figures 2, 3). The compounds were matched with the identity of known molecules on the Metlin database, a threshold Molecular Formula Generator (MFG) with scores above 86% along with a ± 2% difference. This revealed 22 and 29 matched (Supplementary Tables 6, 7) and 40 and 32 unmatched compounds, for EA and AC CEF, respectively (Supplementary Tables 8, 9). The 51 matched compounds, above the MFG threshold value, were further explored for their reported antibacterial activities and carried forward for virtual screening. Notably, out of a total of 51, 13 compounds from both groups of EA and AC CEF were redundant and the rest 31 have not been reported to date with any antibacterial activities (Supplementary Tables 6, 7).

Identification of Volatile Constituents by Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

To find any volatile organic bioactive compounds, existing in the EA and AC sequential & direct CEF of Malaysian G. edulis, they were subjected to GC-MS analysis (Supplementary Figures 4-7). The chromatogram of the compounds presented mentionable area% scores (above 0.5%). This revealed 12 and 8 compounds, for the sequential EA and AC CEF, respectively (Table 3) along with 15 and 7 for the direct CEF of EA & AC, respectively (Table 4). Combining the total number of 42 compounds obtained from the GC-MS analyses of EA and AC sequential & direct CEF and removing the redundant ones, the unique number appears to be 28 out of which 25 compounds revealed to have not been associated with any antibacterial activities (Tables 3, 4).

TABLE 3.

Compounds existing in G. edulis ethyl acetate and acetone (S) extract identified by GC-MS analysis.

| No | Extracts | Identified compounds | Molecular formula | R.T. (Min) | Area% | Antibacterial activity report |

| 1 | EA(S) | 3,8,13,18-Tetraethyl-2,7,12,17-tetramethyl-7, 8-(diacetyl) methylene-7,8-dihydro-21H,23H-porphine copper (II) | C37H42CuN4O2 | 32.09 | 4.035 | NR |

| 2 | Phenol, 2,4-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl) | C14H22O | 14.41 | 3.925 | Reported (Padmavathi et al., 2014) | |

| 3 | Phytol | C20H40O | 26.67 | 2.3 | Reported (Ghaneian et al., 2015) | |

| 4 | Decanoic acid, ethyl ester | C12H24O2 | 24.54 | 1.787 | NR | |

| 5 | n-Hexadecanoic acid | C16H32O2 | 23.98 | 5.008 | NR | |

| 6 | 3-Methyl-1,2-diazirine | C2H4N2 | 3.01 | 7.529 | NR | |

| 7 | 1-Octadecyne | C18H34 | 21.52 | 2.2 | NR | |

| 8 | Diisooctyl phthalate | C24H38O4 | 33.77 | 0.914 | NR | |

| 9 | 1,2-Benzenediol bis(trimethylsilyl) ether | C12H22O2Si2 | 57.93 | 2.052 | NR | |

| 10 | Nickel tetracarbonyl | C4NiO4 | 3.1 | 1.797 | NR | |

| 11 | 4-Penten-2-one, 4-methyl- | C6H10O | 10.91 | 1.628 | NR | |

| 12 | Molybdenum, bis[(1,2,3,4,5-ü)-1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-2,4-cyclopentadien-1-yl] di-ae- carbonyldicarbonyldi-, (mo-mo) | C16H10Mo2O6–6 | 52.89 | 0.646 | NR | |

| 1 | AC(S) | Phenol, 2,4-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)- | C14H22O | 14.41 | 0.771 | Reported (Padmavathi et al., 2014) |

| 2 | n-Hexadecanoic acid | C16H32O2 | 24.08 | 9.078 | NR | |

| 3 | Diisooctyl phthalate | C24H38O4 | 33.77 | 3.878 | NR | |

| 4 | 26-Nor-5-cholesten-3á-ol-25-one | C26H42O2 | 45.57 | 1.725 | NR | |

| 5 | Hexadecanoic acid, ethyl ester | C18H36O2 | 24.54 | 2.074 | NR | |

| 6 | Arachidonic acid | C20H32O2 | 30.23 | 1.039 | Reported (Beavers et al., 2019) | |

| 7 | Nickel tetracarbonyl | C4NiO4 | 7.51 | 1.329 | NR | |

| 8 | 2-Heptyl-1,3-dioxolane | C10H20O2 | 53.21 | 2.882 | NR |

NR, Not reported; S, sequential extracts.

TABLE 4.

Compounds existing in G. edulis ethyl acetate and acetone (D) extracts identified by GC-MS analysis.

| No | Extracts | Identified compounds | Molecular formula | R.T. (Min) | Area% | Antibacterial activity reports |

| 1 | EA(D) | Phenol, 2-methoxy-3-(2-propenyl)- | C10H12O2 | 10.73283 | 6.3257 | NR |

| 2 | Phenol, 2,4-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl) | C14H22O | 14.44737 | 7.7157 | Reported (Padmavathi et al., 2014) | |

| 3 | n-Hexadecanoic acid | C16H32O2 | 24.12967 | 9.1086 | NR | |

| 4 | Diisooctyl phthalate | C24H38O4 | 33.80467 | 0.56258 | NR | |

| 5 | Cholesterol | C27H46O | 45.68133 | 32.831 | NR | |

| 6 | Non-adecane | C19H40 | 18.65483 | 4.034 | NR | |

| 7 | Decanoic acid, ethyl ester | C12H24O2 | 24.5795 | 5.3174 | NR | |

| 8 | Arachidonic acid | C20H32O2 | 30.26833 | 1.4028 | Reported (Beavers et al., 2019) | |

| 9 | 1-Octadecyne | C18H34 | 21.55767 | 0.63897 | NR | |

| 10 | Silane, tetramethyl | C4H12Si | 61.334 | 0.18473 | NR | |

| 11 | 2-Tridecanone | C13H26O | 21.6535 | 0.66248 | NR | |

| 12 | Oxalic acid, cyclobutyl octadecyl ester | C24H44O4 | 28.1485 | 0.15812 | NR | |

| 13 | Ribo-ribo disaccharide | C10H18O9 | 59.13117 | 0.59025 | NR | |

| 14 | [2,2′-Bifuran]-3-carboxylic acid, 5′- methyl-, methyl ester | C11H10O4 | 14.44403 | 7.7157 | NR | |

| 15 | á Carotene | C40H56 | 27.802 | 0.9908 | NR | |

| 1 | AC(D) | Phenol, 2-methoxy-3-(2-propenyl)- | C10H12O2 | 10.73117 | 8.9936 | NR |

| 2 | Decanoic acid, ethyl ester | C12H24O2 | 24.57283 | 2.2412 | NR | |

| 3 | n-Hexadecanoic acid | C16H32O2 | 23.96033 | 1.2408 | NR | |

| 4 | Diisooctyl phthalate | C24H38O4 | 33.79967 | 0.85802 | NR | |

| 5 | Cholest-5-en-3-ol | C27H48O | 45.63817 | 3.4662 | NR | |

| 6 | Ar-tumerone | C15H20O | 17.86533 | 1.7063 | Reported (Marliyana et al., 2019) | |

| 7 | Phenol, 2,4-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)- | C14H22O | 14.44403 | 4.6668 | Reported (Padmavathi et al., 2014) |

NR, Not reported; D, direct extracts.

Virtual Screening and Pharmacological Screening

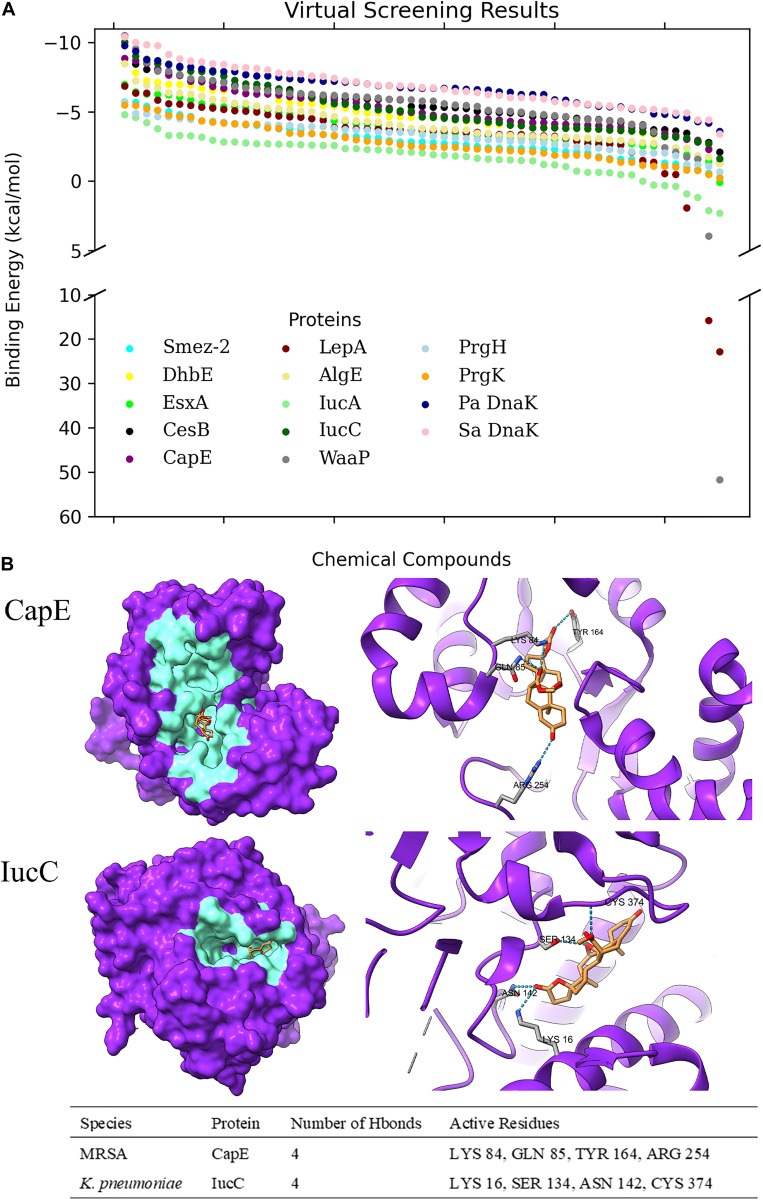

Among the total 65 chemical determinants obtained from different chromatographic analyses, 3 having chemical structure redundancies, and 7 which fall into the limitation of AutoDock 4, were discarded from further virtual screening pipeline to avoid inaccuracies in prediction parameterizations. Structure-based virtual screening of the rest 55 chemical determinants was conducted upon the top-ranked P2rank predicted druggable pockets (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 2) of a set of 12 different bacterial key proteins from S. enterica (PrgK and PrgH), K. pneumoniae (IucA and IucC), P. aeruginosa (WaaP and AlgE), Methicillin-Resistant S. aureus (CapE and EsxA), S. pyogenes (LepA and SmeZ-2), and B. subtilis (DhbE and CesB) (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 2). This has been utilized as the possible role players in determining the antibacterial activity of the G. edulis CEF. The complexes of these ligands with the proteins having binding energies around and lower than -7 kcal/mol indicate potentially druggable molecules or drug targets.

FIGURE 2.

Virtual Screening of Chemical Determinants against selected target proteins. (A) Scatter plot of virtual screening through multiple bacterial virulent proteins based on their binding energies to each chemical determinant. Pa DnaK refers to P. aeruginosa DnaK protein, while Sa DnaK refers to S. aureus DnaK protein. (B) 3D representation of Eplerenone binding to CapE of MRSA and IucC of K. pneumoniae. The localization of active residues involved in binding and hydrogen bonding interactions are shown in the table format.

With a simultaneous consideration of the structure-based virtual screening and the predicted pharmacological properties of each chemical determinant, Eplerenone turned out to be a highly potentially druggable molecule. This is due to its strong binding affinity to most of the aforesaid proteins, which can be inferred from its moderate average binding score of -6.1007 kcal/mol. Moreover, it has a near-perfect predicted pharmacological properties for which adverse effects, due to ADME complications, would not be expected after intake.

Regarding Eplerenone, three target proteins, namely, CesB, CapE, and IucC, have manifested potential druggability due to stable binding energy lower than -7 kcal/mol viz. -7.66 kcal/mol, -7.21 kcal/mol, and -8.8 kcal/mol, respectively. The protein-ligand hydrogen bonding network has been observed for all three proteins (Figure 2). CesB, however, has been ceased for further analysis due to the absence of detectable protein-ligand hydrogen bonds. On the contrary, CapE and IucC have manifested rich intermolecular electrostatic interactions with Eplerenone having 4 hydrogen bonds each, and, therefore, was nominated to be potential drug targets of Eplerenone.

Discussion

Resistance development of bacteria, to antibiotics, makes them ineffective, thereby resulting in the continuous demand for novel antibacterial agents. Marine organisms are potential sources of antibacterial agents that can probably inhibit the development of MDR bacteria. In the current study, we explored the antibacterial properties of Malaysian G. edulis, which are edible red seaweeds, largely found in Southeast Asian countries. Essentially, the G. edulis CEF, with various organic solvents, were screened against six MDR bacterial species, namely, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, S. enterica, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), S. pyogenes, and B. subtilis. The screened CEF, showing promising antibacterial activities, were chromatographed through LC-MS and GC-MS to reveal a plethora of 65 compounds. A virtual screening of these compounds, followed by analyzing pharmacological properties, against selected key role playing proteins of the aforementioned bacteria, revealed Eplerenone as potential drug candidate for future pharmacological industries.

Among the set of six chosen solvents, in order of increasing polarity, i.e., chloroform (CF), ethyl acetate (EA), acetone (AC), ethanol (ET), methanol (MT), and water (WT), our findings confirmed that EA and AC sequential CEF were potentially effective in inhibiting the growth of all TBS. The remaining CEF responded either moderately or poorly, thereby providing a clear indication to proceed for further direct extraction from EA and AC. A moderate zone of inhibition was observed in EA and AC direct CEF against B. subtilis and P. aeruginosa. A concentration of 250 μg/mL was effective for EA and AC direct CEF against the TBS excluding S. enterica for this was 2000 μg/mL. On the contrary, however, in the case of sequential CEFs, EA displayed the inhibitory effect, at 2000 μg/ml, toward only B. subtilis and S. enterica whereas AC confirmed effect against B. subtilis, MRSA and K. pneumoniae at the same concentration.

Our findings revealed that EA and AC CEF are suitable for further exploration of the antibacterial properties of the red seaweed G. edulis. Our findings were more commensurate with related studies on the EA and AC CEF of red seaweeds, other than G. edulis. For instance, Salem et al. (2011) reported that the EA CEF of the red seaweed Actinotrichia fragilis showed positive antibacterial activity against S. aureus, Bacillus cereus, E. coli, Salmonella sp. and P. aeruginosa. Likewise, Abdel-Latif et al. (2018) confirmed that the, EA CEF of the red algae, Grateloupia doryphora had promising in vitro antibacterial potential toward B. subtilis, E. faecalis, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and E. coli. Again, Banu and Mishra (2018) reported the antibacterial effect of AC CEF of Tricleocarpa fragilis against S. aureus and B. cereus. However, there are few reports on the antibacterial potential of other solvents CEF of G. edulis as well. One of the earlier reports by Kolanjinathan et al. (2009) confirmed antibacterial potency of G. edulis ET CEF against E. coli, Enterobacter aerogenes, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and Streptococcus faecalis. Later, Kolanjinathan and Saranraj (2014) explored the antibacterial potential of MT CEF from G. edulis against, S. pyogenes, B. subtilis, S. aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, B. cereus, K. pneumoniae, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi, P. aeruginosa, and E. coli. Recently, Umakanthan et al. (2017) described antibacterial effects of petroleum ether, hexane, AC, ET and MT CEF of G. edulis against S. aureus and E. coli. Thus, it turns out that our tested EA and AC CEF could reveal a better profile of the chemical compounds or metabolites present in G. edulis.

Based on the prominent antibacterial actions of the EA and AC CEF of G. edulis, we expected that both these CEF could harbour important bioactive compounds. Thus, sequential extracts of EA and AC CEF were subjected to a detailed mass-oriented LC-MS analysis (Supplementary Tables 6, 7). This revealed a widespread range of chemical classes existing in both the CEF. Amongst these, only 2 of the 22 compounds (with above 86% MFG scores) of the EA CEF have been reported to possess antibacterial activities (Supplementary Table 6). For example, the antibacterial effects of L13 (Gingerol) and L19 (Pheophorbide a) have been reported with by Prieto Rodríguez et al. (2011); Ghasemzadeh et al. (2016), respectively. Similarly, the AC extract fractions contained only 5, from a total of 29 compounds, with reported antibacterial activities (Supplementary Table 7). These are for L11 (6-Paradol) reported by El Dine et al. (2019), L22 (Carindone) by Lindsay et al. (2000), L23 (Pyropheophorbide a) by Kraatz et al. (2014), L24 (Pheophorbide-a) by Prieto Rodríguez et al. (2011), and L28 (Non-oxynol-9) by Hooton et al. (1991). Thus, possibilities exist for those 40 and 32 compounds from EA and AC fractions, respectively, with no matched identity with the library (Supplementary Tables 8, 9), to be therapeutically significant, though, further classification is obligatory to assess their usages.

Additional disclosure of important bioactive compounds was authenticated via GC-MS (Tables 3, 4). Notably, both sequential and direct CEF of EA and AC were subjected for GC-MS analysis. In contrast to the LC-MS reported compounds, about 95% of the chemical determinants, extracted through GC-MS, are unidentified for their antibacterial potentials. For example, among the 20 compounds from the sequential CEF of EA and AC (with area% scores above 0.5%) only 2 of the 12 compounds of the EA CEF have been reported with antibacterial properties (Table 3). These are SGEA2 reported by Padmavathi et al. (2014) and SGEA3 by Ghaneian et al. (2015). Along with 10 other compounds from EA CEF, the AC CEF contained 8 compounds without any a priori reported antibacterial activity (Table 3). Likewise, for the direct CEF of EA, only 1 out of 15 compounds detected (with area% scores above 0.5%) were known to possess such activity (Table 4). These are DGEA2 reported by Padmavathi et al. (2014), DGEA8 by Beavers et al. (2019), Again, for the AC CEF, 2 out of total 7 compounds detected, were reported with antibacterial effects (Table 4). These are DGAC6 by Marliyana et al. (2019) and DGAC7 by Padmavathi et al. (2014).

Over time, creditable progress in the field of virtual screening has permitted time- and cost-efficient drug discovery with repurposing (Abdella et al., 2020). Thus, we have considered a similar approach to antibacterial drug discovery from the CEF of Malaysian red seaweed, G. edulis. With a set of 65 compounds obtained through chromatographic analyses, we have conducted a series of computational analyses. This ensued with the selection of crucial target proteins from the TBS followed by a virtual screening of the set of chemicals onto the targets through molecular docking and finally analyzing their pharmacological properties to predict their bioavailability and toxicity (Supplementary Table 10). This culminated in the pinning of Eplerenone as the selected and predicted chemical compound from the EA and AC CEF of G. edulis. Importantly, Eplerenone is known as a potassium-sparing diuretic and has been used for patients with chronic heart diseases (CHD), but is more selective and thus, having fewer side effects, among the spironolactone class of steroidal antimineralocorticoids (Struthers et al., 2008; Pierson-Marchandise et al., 2017). As it is already in use in the market as a drug against CHD, it is imperative to have passed the clinical trials. Hence, it was not considered in this study to be further purified from the crude extracts and checked for cytotoxicity test (Tam et al., 2017). Thus, in essence, the proposal for the compound Eplerenone, for its antibacterial potential, reflects the concept of drug repurposing. It is important to note that, Eplerenone serves to be an alternative to antibiotics and is not proposed to be a new antibiotic per se.

To this end, our consideration of the proteins to be utilized for the aforementioned virtual screening also needs detailing in terms of their virulence potential. It is to be noted that virulence factors have gained traction over the years for considering the future plausible drug targets of MDR bacterial strains (Ogawara, 2021). Notably, without any imposition, on a bacterial population, for a highly selective pressure, anti-virulence drugs are better alternatives to antibiotics. Moreover, impaired virulence factors render the virulent pathogens to be pathobionts or avirulent bacteria. This might help the peaceful coexistence of the human population with these pathobionts. Thus, different representative virulent proteins from different bacteria were considered. These were a set of 12 different bacterial key proteins from S. enterica (PrgK and PrgH), K. pneumoniae (IucA and IucC), P. aeruginosa (WaaP and AlgE), methicillin-resistant S. aureus (CapE and EsxA), S. pyogenes (LepA and SmeZ-2) and B. subtilis (DhbE and CesB) (Figure 1). These proteins were selected due to their available crystal structure in PDB for further docking studies during virtual screening. On the contrary, earlier homology modelled and validated DnaK structure was utilized for P. aeruginosa and S. aureus. Essentially, DnaK acts as a molecular chaperone, mediated by its ATPase activities (Chiappori et al., 2015), and has been reported to be central in mediating bacterial stress responses due to its mutants exhibiting an increase in antimicrobial susceptibilities and decrease in survivability in the host (Wolska et al., 2000; Yamaguchi et al., 2003; Singh et al., 2007). Again, a study on the whole-genome analysis (WGA) of protein interaction network (PIN) reported that DnaK protein was crucial in mediating quorum sensing in multidrug resistant Proteus mirabilis (Pawar et al., 2018). Furthermore, WGA analyses of PIN from MDR pathogens like P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, S. enterica, S. pneumoniae, P. mirabilis, Acinetobacter baumannii, Escherichia coli, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis revealed DnaK to be among the top 10 crucial proteins indispensable for the cellular integrity of the bacteria (Mujawar et al., 2020). Hence, DnaK protein has also been selected for the in silico study, herein, as a promising drug target for selected MDR bacteria.

The proteins PrgK and PrgH, of Salmonella species, form the inner rings of the structurally complex syringe-like inject some, at the base substructure, which mediates the transfer of virulent factors into the host cell during invasion (Hu et al., 2017). IucA and IucC proteins are crucial mediators in the aerobactin synthesis pathway in bacteria (Mydy et al., 2020) and have been recently proposed as antivirulence targets in K. pneumoniae (Russo and Gulick, 2019). WaaP is a lipopolysaccharide heptose kinase, essential for P. aeruginosa growth due to its indispensable role in bacterial outer membrane synthesis by aiding in lipid-A core biosynthesis (Zhao and Lam, 2002). Again, in Pseudomonas species, the AlgE protein is essential in the alginate biosynthesis pathway which eventually leads to biofilm formation in bacteria and eventually results in virulence (Xu et al., 2019). To this end, we have also considered DnaK for P. aeruginosa. This protein is a bacterial molecular chaperone of the Heat Shock Protein 70 kDa (HSP70) family which mediates bacterial survival under stress conditions, especially antibiotic administration (Singh et al., 2012). It has been proposed as an attractive druggable target as well as a vaccine candidate (Fourie and Wilson, 2020). Moreover, DnaK has also been identified to be important in quorum sensing, as well as cellular integrity in bacteria by other studies (Pawar et al., 2018; Mujawar et al., 2020).

DnaK has also been considered for S. aureus, besides the CapE protein. The latter is involved in the biosynthesis of capsular polysaccharide (Miyafusa et al., 2013) which constitutes the cell surface carbohydrate layer to confer immunological and physiological protective effects to the bacteria thereby preventing phagocytic events and aiding in bacterial survival in host bloodstream. Moreover, the EsxA protein of S. aureus has an important role in establishing infections in the host by acting as adaptor proteins aiding protein transport during pathogenesis (Sundaramoorthy et al., 2008) and has been reported as a druggable target as well as a vaccine candidate in coping with S. aureus infections (Sze and Kao, 2020). LepA, being ranked 3rd in the aspect of the highest level of conservation in bacteria, acts as an elongation factor during the gene translation events in S. pyogenes (Evans et al., 2008) and has been reported to be crucial in aiding bacterial growth in a stressed environment, both chemically and physically (Heller et al., 2017). SmeZ, or Streptococcal mitogenic endotoxin Z, is the most potent superantigens as per the discovery thus far (Popugailo et al., 2019). It inhibits the inflammatory reactions in the host, as well as inducing immunological complications by acting on the crucial molecules of the immune system such as MHC-II and T cell receptor, thereby inducing T cell hyperactivation and eventually unnecessary tissue damage (Popugailo et al., 2019). The DhbE protein is involved in bacterial biosynthesis of siderophore thereby enabling the survival of bacteria like Bacillus species in high iron concentration environment, especially the blood (May et al., 2001). Again, in Bacillus species, the cesB gene encodes the protein cereulide (CesB), a notorious bacterial toxin with high heat and acid tolerance which has been haunting the food industry by eventuating foodborne diseases outbreaks (Ducrest et al., 2019; Rouzeau-Szynalski et al., 2020).

Cultivation of seaweed in a laboratory is not an easy task. Moreover, large-scale algae cultivation and production are affected by several prominent factors, such as light intensity, temperature, pH, salinity, nutrients availability, and the presence of oxygen, carbon dioxide and inorganic carbon. However, in Malaysia, large-scale cultivation of seaweeds is conducted at the open sea of the eastern coast of Sabah, which is situated below the monsoon and typhoon belt. Nevertheless, seaweeds possess a vast diversity of secondary metabolites, which are potential novel sources of bioactive constituents with a broad spectrum of biological actions. Moreover, some metabolites derived from seaweeds have not been found in terrestrial plants.

Conclusion

The current study re-defines a method to reveal bioactive compounds from the crude extracts of Malaysian red seaweed G. edulis, having promising antibacterial activities against selected bacterial species. Three species of Gram-positive and -negative characters were remarkably inhibited by the sequential and direct extracts of ethyl acetate and acetone. These were further separated through chromatographic methods to reveal a plethora of chemical constituents to be considered for a downstream virtual screening against selected crucial proteins of the six bacteria. The additional pharmacological screening revealed Eplerenone with a potential to be repurposed as an alternate source for an antibacterial compound. While more studies are needed to establish such activity of Eplerenone, our metabolic profiling paves the way for future researchers to further explore such unseen potentials of the Malaysian natural product G. edulis.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in the study are deposited in the Metabolomics Workbench repository, http://dx.doi.org/10.21228/M8N11H.

Author Contributions

CL conceived the concepts and planned and designed the analyses. AA extracted the natural product and assessed its antibacterial activity. AA analyzed the data for LC-MS and GC-MS with the help of CL. Y-YY provided the plant product and co-supervisory inputs. Y-CT and MS conducted the computational studies with occasional inputs from CL. AA and Y-CT generated the figures and tables with guidance provided and primarily wrote the manuscript aided by complete editorial upgradation by CL. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the Sunway University, Selangor, Malaysia for the provision of necessary computational facilities. The authors thank Syafiq Asnawi of the Monash University, Malaysia and K. C. Kong of Cytomics, Malaysia, for providing the results of LC-MS and GC-MS, respectively. The co-supervisory feedback of Ezzat Khan is also, hereby, acknowledged.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2021.653562/full#supplementary-material

References

- Abdella M., Abdella B., Lahiri C. (2020). “Rediscovering and repurposing natural microbial macromolecules through computational approaches,” in Microbial and Natural Macromolecules, eds Das S., Dash H. R. (Amsterdam: Elsevier; ), 373–400. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Latif H. H., Shams El-Din N. G., Ibrahim H. A. H. (2018). Antimicrobial activity of the newly recorded red alga Grateloupia doryphora collected from the Eastern Harbor, Alexandria, Egypt. J. Appl. Microbiol. 125 1321–1332. 10.1111/jam.14050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agregán R., Munekata P. E., Domínguez R., Carballo J., Franco D., Lorenzo J. M. (2017). Proximate composition, phenolic content and in vitro antioxidant activity of aqueous extracts of the seaweeds Ascophyllum nodosum, Bifurcaria bifurcata and Fucus vesiculosus. effect of addition of the extracts on the oxidative stability of canola oil under accelerated storage conditions. Int. Food. Res. J. 99 986–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arulkumar A., Rosemary T., Paramasivam S., Rajendran R. B. (2018). Phytochemical composition, in vitro antioxidant, antibacterial potential and GC-MS analysis of red seaweeds (Gracilaria corticata and Gracilaria edulis) from Palk Bay, India. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 15 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Asghar A., Tan Y. C., Zahoor M., Asnawi S., Yow Y.-Y., Khan E., et al. (2020). Chromatographic Analyses, Virtual Screening and Pharmacokinetics of Yellow Malaysian Rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum L.) Fruit Epicarp Extracts Reveal Potential Antibacterial Compounds. Available online at 10.21203/rs.3.rs-125241/v1 (accessed January 14,2021). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banu V. S., Mishra J. K. (2018). Antimicrobial activity of different solvent based crude extracts from red seaweed Tricleocarpa fragilis (L.) Huisman & RA Towns from the coast of South Andaman. Pharma Innov. 7 123–127. [Google Scholar]

- Beavers W. N., Monteith A. J., Amarnath V., Mernaugh R. L., Roberts L. J., Chazin W. J., et al. (2019). Arachidonic acid kills Staphylococcus aureus through a lipid peroxidation mechanism. Mbio 10:e01333–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman H. M., Westbrook J., Feng Z., Gilliland G., Bhat T. N., Weissig H., et al. (2000). The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 28 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan P. T., Matanjun P., Yasir S. M., Tan T. S. (2015). Antioxidant activities and polyphenolics of various solvent extracts of red seaweed, Gracilaria changii. J. Appl. Phycol. 27 2377–2386. [Google Scholar]

- Cheesman M. J., Ilanko A., Blonk B., Cock I. E. (2017). Developing new antimicrobial therapies: are synergistic combinations of plant extracts/compounds with conventional antibiotics the solution? Pharmacogn. Rev. 11 57–72. 10.4103/phrev.phrev_21_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung R. C. F., Wong J. H., Pan W., Chan Y. S., Yin C., Dan X., et al. (2015). Marine lectins and their medicinal applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 99 3755–3773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiappori F., Fumian M., Milanesi L., Merelli I. (2015). DnaK as antibiotic target: hot spot residues analysis for differential inhibition of the bacterial protein in comparison with the human HSP70. PLoS One 10:e0124563. 10.1371/journal.pone.0124563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daina A., Michielin O., Zoete V. (2017). SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 7:42717. 10.1038/srep42717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Almeida C. L., Falcao Hde S., Lima G. R., Montenegro Cde A., Lira N. S., de Athayde-Filho P. F., et al. (2011). Bioactivities from marine algae of the genus Gracilaria. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 12 4550–4573. 10.3390/ijms12074550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducrest P. J., Pfammatter S., Stephan D., Vogel G., Thibault P., Schnyder B. (2019). Rapid detection of Bacillus ionophore cereulide in food products. Sci. Rep. 9:5814. 10.1038/s41598-019-42167-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan W. J., Merz K. M., Baldwin J. J. (2000). Prediction of drug absorption using multivariate statistics. J. Med. Chem. 43 3867–3877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Dine R. S., Elfaky M. A., Asfour H., El Halawany A. M. (2019). Anti-adhesive activity of Aframomum melegueta major phenolics on lower respiratory tract pathogens. Nat. Prod. Res. 35 539–547. 10.1080/14786419.2019.1585843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Shafay S. M., Ali S. S., El-Sheekh M. M. (2016). Antimicrobial activity of some seaweeds species from Red sea, against multidrug resistant bacteria. Egypt. J. Aquat. Res. 42 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Evans R. N., Blaha G., Bailey S., Steitz T. A. (2008). The structure of LepA, the ribosomal back translocase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 4673–4678. 10.1073/pnas.0801308105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourie K. R., Wilson H. L. (2020). Understanding GroEL and DnaK stress response proteins as antigens for bacterial diseases. Vaccines. 8:773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaneian M. T., Ehrampoush M. H., Jebali A., Hekmatimoghaddam S., Mahmoudi M. (2015). Antimicrobial activity, toxicity and stability of phytol as a novel surface disinfectant. Environ. Health. Eng. Manag. 2 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemzadeh A., Jaafar H. Z., Rahmat A. (2016). Changes in antioxidant and antibacterial activities as well as phytochemical constituents associated with ginger storage and polyphenol oxidase activity. BMC Compl. Alternative. Med. 16:382. 10.1186/s12906-016-1352-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghose A. K., Viswanadhan V. N., Wendoloski J. J. (1999). A knowledge-based approach in designing combinatorial or medicinal chemistry libraries for drug discovery. 1. a qualitative and quantitative characterization of known drug databases. J. Comb. Chem. 1 55–68. 10.1021/cc9800071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hann M. M., Keseru G. M. (2012). Finding the sweet spot: the role of nature and nurture in medicinal chemistry. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 11 355–365. 10.1038/nrd3701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller J. L. E., Kamalampeta R., Wieden H. J. (2017). Taking a step back from back-translocation: an integrative view of LepA/EF4’s cellular function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 37 e00653–16. 10.1128/MCB.00653-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemasudha T. S., Thiruchelvi R., Balashanmugam P. (2019). Antioxidant, antibacterial, and anticancer activity from marine red algae Gracilaria Edulis. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 12 276–279. 10.22159/ajpcr.2019.v12i2.29883 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hooton T. M., Fennell C. L., Clark A. M., Stamm W. E. (1991). Nonoxynol-9: differential antibacterial activity and enhancement of bacterial adherence to vaginal epithelial cells. J. Infect. Dis. 164 1216–1219. 10.1093/infdis/164.6.1216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B., Lara-Tejero M., Kong Q., Galan J. E., Liu J. (2017). In situ molecular architecture of the Salmonella type. Cell 168 1065–1074.e10. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail M. M., Gheda S. F., Pereira L. (2016). Variation in bioactive compounds in some seaweeds from Abo Qir bay, Alexandria, Egypt. Rend. Lincei 27 269–279. [Google Scholar]

- Kasanah N., Amelia W., Mukminin A., Triyanto, Isnansetyo A. (2019). Antibacterial activity of Indonesian red algae Gracilaria edulis against bacterial fish pathogens and characterization of active fractions. Nat. Prod. Res. 33 3303–3307. 10.1080/14786419.2018.1471079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khelil-Radji F., Belhouari M., Chemlal-Kherraz D., Matallah-Boutiba A., Boutiba Z. (2017). Antimicrobial activity of aqueous and ethanol extracts of two marine algae collected from Algerian west coast. Electron. J. Environ. Agric. Food Chem. 6655 100–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kolanjinathan K., Saranraj P. (2014). Pharmacological efficacy of marine seaweed Gracilaria edulis extracts against clinical pathogens. Glob. J. Pharmacol. 8 268–274. [Google Scholar]

- Kolanjinathan K., Ganesh P., Govindarajan M. (2009). Antibacterial activity of ethanol extracts of seaweeds against fish bacterial pathogens. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 13 173–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraatz M., Whitehead T. R., Cotta M. A., Berhow M. A., Rasmussen M. A. (2014). Effects of chlorophyll-derived efflux pump inhibitor pheophorbide a and pyropheophorbide a on growth and macrolide antibiotic resistance of indicator and anaerobic swine manure bacteria. J. Antibiot. 2014 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Krivák R., Hoksza D. (2018). P2Rank: machine learning based tool for rapid and accurate prediction of ligand binding sites from protein structure. J Cheminformatics 10:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay E. A., Berry Y., Jamie J. F., Bremner J. B. (2000). Antibacterial compounds from Carissa lanceolata R.Br. Phytochemistry 55 403–406. 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00343-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski C. A. (2004). Lead- and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 1 337–341. 10.1016/j.ddtec.2004.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Zheng D., Jin Q., Chen L., Yang J. (2019). VFDB 2019: a comparative pathogenomic platform with an interactive web interface. Nucleic Acids Res. 47 D687–D692. 10.1093/nar/gky1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marliyana S., Wibowo F., Wartono M., Munasah G. (2019). Evaluation of antibacterial activity of sesquiterpene Ar-Turmerone from Curcuma soloensis Val. rhizome. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 578:012060. [Google Scholar]

- May J. J., Wendrich T. M., Marahiel M. A. (2001). The dhb operon of bacillus subtilisEncodes the biosynthetic template for the catecholic siderophore 2, 3-dihydroxybenzoate-glycine-threonine trimeric ester bacillibactin. J. Biol. Chem. 276 7209–7217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mérillon J. M., Rivière C. (2018). Natural Antimicrobial Agents. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Miyafusa T., Caaveiro J. M., Tanaka Y., Tsumoto K. (2013). Dynamic elements govern the catalytic activity of CapE, a capsular polysaccharide-synthesizing enzyme from Staphylococcus aureus. FEBS Lett. 587 3824–3830. 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris G. M., Huey R., Lindstrom W., Sanner M. F., Belew R. K., Goodsell D. S., et al. (2009). AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 30 2785–2791. 10.1002/jcc.21256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muegge I., Heald S. L., Brittelli D. (2001). Simple selection criteria for drug-like chemical matter. J. Med. Chem. 44 1841–1846. 10.1021/jm015507e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mujawar S., Abd El-Aal A. A. A., Lahiri C. (2020). “Variant analysis from bacterial isolates affirms DnaK crucial for multidrug resistance,” in International Work-Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering, eds Rojas I., Valenzuela O., Rojas F., Herrera L., Ortuño F. (Berlin: Springer; ), 237–248. [Google Scholar]

- Mydy L. S., Bailey D. C., Patel K. D., Rice M. R., Gulick A. M. (2020). The siderophore synthetase IucA of the aerobactin biosynthetic pathway uses an ordered mechanism. Biochemistry 59 2143–2153. 10.1021/acs.biochem.0c00250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawara H. (2021). Possible drugs for the treatment of bacterial infections in the future: anti-virulence drugs. J. Antibiot. 74 24–41. 10.1038/s41429-020-0344-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmavathi A. R., Abinaya B., Pandian S. K. (2014). Phenol, 2,4-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl) of marine bacterial origin inhibits quorum sensing mediated biofilm formation in the uropathogen Serratia marcescens. Biofouling 30 1111–1122. 10.1080/08927014.2014.972386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawar S., Ashraf M. I., Mujawar S., Mishra R., Lahiri C. (2018). In silico identification of the indispensable quorum sensing proteins of multidrug resistant Proteus mirabilis. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 8:269. 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen E. F., Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Couch G. S., Greenblatt D. M., Meng E. C., et al. (2004). UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25 1605–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierson-Marchandise M., Gras V., Moragny J., Micallef J., Gaboriau L., Picard S., et al. (2017). The drugs that mostly frequently induce acute kidney injury: a case− noncase study of a pharmacovigilance database. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 83 1341–1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popugailo A., Rotfogel Z., Supper E., Hillman D., Kaempfer R. (2019). Staphylococcal and streptococcal superantigens trigger B7/CD28 costimulatory receptor engagement to hyperinduce inflammatory cytokines. Front. Immunol. 10:942. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto Rodríguez J. A., Patiño Ladino O. J., Lesmes L., Lozano J. M., Cuca Suárez L. E. (2011). Phytochemical study of Uncaria guianensis leaves and antibacterial activity evaluation. Acta Amazon. 41 303–310. [Google Scholar]

- Rosemary T., Arulkumar A., Paramasivam S., Mondragon-Portocarrero A., Miranda J. M. (2019). Biochemical, micronutrient and physicochemical properties of the dried red seaweeds Gracilaria edulis and Gracilaria corticata. Molecules 24:2225. 10.3390/molecules24122225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouzeau-Szynalski K., Stollewerk K., Messelhäusser U., Ehling-Schulz M. (2020). Why be serious about emetic Bacillus cereus: cereulide production and industrial challenges. Food Microbiol. 85:103279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo T. A., Gulick A. M. (2019). Aerobactin synthesis proteins as antivirulence targets in hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. ACS Infect. Dis. 5 1052–1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salem W. M., Galal H., El-deen N. (2011). Screening for antibacterial activities in some marine algae from the red sea (Hurghada, Egypt). Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 5 2160–2167. [Google Scholar]

- Samdani A., Vetrivel U. (2018). POAP: a GNU parallel based multithreaded pipeline of open babel and AutoDock suite for boosted high throughput virtual screening. Comput. Biol. Chem. 74 39–48. 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2018.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seedevi P., Moovendhan M., Viramani S., Shanmugam A. (2017). Bioactive potential and structural chracterization of sulfated polysaccharide from seaweed (Gracilaria corticata). Carbohydr. Polym. 155 516–524. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha P., Cooper B. S., Coast J., Oppong R., Thuy N. D. T., Phodha T., et al. (2018). Enumerating the economic cost of antimicrobial resistance per antibiotic consumed to inform the evaluation of interventions affecting their use. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 7:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh V. K., Syring M., Singh A., Singhal K., Dalecki A., Johansson T. (2012). An insight into the significance of the DnaK heat shock system in Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 302 242–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh V. K., Utaida S., Jackson L. S., Jayaswal R. K., Wilkinson B. J., Chamberlain N. R. (2007). Role for dnaK locus in tolerance of multiple stresses in Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiology 153(Pt. 9), 3162–3173. 10.1099/mic.0.2007/009506-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struthers A., Krum H., Williams G. H. (2008). A comparison of the aldosterone-blocking agents eplerenone and spironolactone. Clin. Cardiol. 31 153–158. 10.1002/clc.20324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subermaniam K., Yow Y. Y., Lim S. H., Koh O. H., Wong K. H. (2020). Malaysian macroalga padina australis hauck attenuates high dose corticosterone-mediated oxidative damage in PC12 cells mimicking the effects of depression. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 27 1435–1445. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.04.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramani R., Narayanasamy M., Feussner K. D. (2017). Plant-derived antimicrobials to fight against multi-drug-resistant human pathogens. 3 Biotech 7:172. 10.1007/s13205-017-0848-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaramoorthy R., Fyfe P. K., Hunter W. N. (2008). Structure of Staphylococcus aureus EsxA suggests a contribution to virulence by action as a transport chaperone and/or adaptor protein. J. Mol. Biol. 383 603–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sze K. H., Kao R. Y. T. (2020). Characterisation of Staphylococcus aureus virulence factor EsxA and structure-based screening of EsxA inhibitors for combating methicillin-resistant S aureus: abridged secondary publication. Hong Kong Med. J. 26(Suppl. 4), 35–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam T. S., Wu M. H., Masson S. C., Tsang M. P., Stabler S. N., Kinkade A., et al. (2017). Eplerenone for hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2:CD008996. 10.1002/14651858.CD008996.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umakanthan G., Vinobaba P., Radampola K. (2017). Antioxidant activity of Gracilaria edulis (Rhodophyseae) in Sri Lanka. Int. J. Res. 4 1455–1472. [Google Scholar]

- Veber D. F., Johnson S. R., Cheng H.-Y., Smith B. R., Ward K. W., Kopple K. D. (2002). Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates. J. Med. Chem. 45 2615–2623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventola C. L. (2015). The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 1: causes and threats. P T. 40 277–283. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolska K. I., Bugajska E., Jurkiewicz D., Kuc M., Jozwik A. (2000). Antibiotic susceptibility of Escherichia coli dnaK and dnaJ mutants. Microb. Drug Resist. 6 119–126. 10.1089/107662900419429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization [WHO] (2017). WHO Publishes List of Bacteria for Which New Antibiotics are Urgently Needed. Geneva: WHO. Available online at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2017/bacteria-antibiotics-needed/en/ (accessed December 20, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Li K., Pan T., Liu J., Li B., Li C., et al. (2019). Lonicerin, an anti-algE flavonoid against Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence screened from Shuanghuanglian formula by molecule docking based strategy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 239:111909. 10.1016/j.jep.2019.111909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi Y., Tomoyasu T., Takaya A., Morioka M., Yamamoto T. (2003). Effects of disruption of heat shock genes on susceptibility of Escherichia coli to fluoroquinolones. BMC Microbiol. 3:16. 10.1186/1471-2180-3-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap W. F., Tay V., Tan S. H., Yow Y. Y., Chew J. (2019). Decoding antioxidant and antibacterial potentials of malaysian green seaweeds: Caulerpa racemosa and Caulerpa lentillifera. Antibiotics 8:152. 10.3390/antibiotics8030152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Lam J. S. (2002). WaaP of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a novel eukaryotic type protein-tyrosine kinase as well as a sugar kinase essential for the biosynthesis of core lipopolysaccharide. J. Biol. Chem. 277 4722–4730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in the study are deposited in the Metabolomics Workbench repository, http://dx.doi.org/10.21228/M8N11H.