Abstract

Willingness to get the COVID-19 vaccine is crucial to reduce the current strain on healthcare systems and increase herd immunity, but only 71% of the U.S. public said they would get the vaccine. It remains unclear whether Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI), a population with existing inequalities in COVID-19 infection and mortality, are willing to get the vaccine, and the factors associated with vaccine willingness.

Given this imperative, we used data from a national, cross-sectional, community-based survey called COVID-19 Effects on the Mental and Physical Health of AAPI Survey Study (COMPASS), an ongoing survey study that is available in English and Asian languages (i.e., Simplified or Traditional Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese) to examine vaccine willingness among AAPI.

A total of 1,646 U.S. adult AAPI participants completed the survey. Self-reported vaccine willingness showed the proportion who were “unsure” or “probably/definitely no” to getting the COVID-19 vaccine was 25.4%. The odds for vaccine willingness were significantly lower for were Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders (vs. Asian Americans), Korean Americans (vs. Chinese and Vietnamese Americans), women (vs. men), heterosexuals (vs. non-heterosexuals), those aged 30–39 and 50–59 (vs. aged < 30), and those who reported having any vaccine concerns (vs. no concerns).

AAPIs’ willingness to get COVID-19 vaccine varied by groups, which underscores the need for disaggregated AAPI data. A multi-pronged approach in culturally appropriate and tailored health communication and education with AAPI is critical to achieve the goal of health equity for AAPI as it pertains to COVID-19 mortality and morbidity.

Keywords: COVID-19, Vaccine willingness, Asian Americans, Pacific Islanders

1. Introduction

As the number of Americans infected and dying from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) continues to increase (33,470,212 and 601,808 respectively, as of June 29, 2021 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021), it is vital that the U.S. population receive the COVID-19 vaccines to effectively mitigate this pandemic. In December 2020, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authorized Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines for emergency use. (Food and Administration, 2021, Food and Administration, 2021)On February 27, 2021, the FDA provided an emergency use authorization for Janssen COVID-19 vaccine. (Food and Administration, 2021)As of June 29, 2021, 381,831,830 COVID-19 vaccine doses had been distributed and 325,152,847 persons had received one or more doses in the U.S. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Vaccinations in the United States., 2021)

Vaccine uptake is crucial to reduce the strain on healthcare systems and increase herd immunity, albeit the percent that must receive the vaccine to achieve herd immunity remains unknown. (World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Herd immunity, lockdowns and COVID-19., 2021)Surveys conducted in the early months of the pandemic revealed that 31–50% of Americans were hesitant about receiving the COVID-19 vaccine. (Fisher et al., 2020, Callaghan et al., 2020)A recent poll found 27% said they “probably/definitely would not” despite its safety or availability at no-cost. (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020)Factors reportedly associated with vaccine hesitancy included being younger in age (Fisher et al., 2020), self-identification as Black (Fisher et al., 2020, Callaghan et al., 2020, Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020, Reiter et al., 2020), being a woman (Callaghan et al., 2020), lower educational attainment7, (Head et al., 2020), being an essential worker (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020), and working in a health care setting9, (Head et al., 2020). Some reasons for vaccine hesitancy included vaccine-specific concerns (e.g., safety) (Fisher et al., 2020, Callaghan et al., 2020, Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020, Reiter et al., 2020), a need for more information (Fisher et al., 2020), antivaccine attitudes/beliefs7, (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020), concerns about getting COVID-19 from the vaccine (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020), and a lack of trust (Fisher et al., 2020).

There remains limited understanding about willingness to get the COVID-19 vaccineamong Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI), the fastest growing U.S. racial population. (Pew Research Center. Key facts about Asian Americans, a diverse and growing population., 2021)While two surveys had found that Asian Americans (vs. Whites) are more likely to say they would get vaccinated (e.g., 56–83%% of Asians; 46–61% of Whites (Franklin Templeton-Gallup Economics of Recovery Study. Roundup of Recent Gallup Data on Vaccines., 2021, Pew Research Center. Intent to Get a COVID-19 Vaccine Rises to 60% as Confidence in Research and Development Process Increases., 2021), these surveys were limited to English-speaking Asian Americans and data were aggregated. AAPI are heterogenous in their histories, cultures, and languages (Pew Research Center. Key facts about Asian Americans, a diverse and growing population., 2021); and, having disaggregated data would be crucial in public health vaccine efforts to AAPI. The Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity (OMB Statistical Policy Directive No. 15) define minimum federal standards for collecting and presenting data on race and ethnicity, including “Asian” and “Native Hawaiians or Pacific Islander (NHPI)” as separate racial groups. (Office of Management and Budget. Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity., 2021)Additionally, research has shown that language accessibility has important implications for health, health care access, and research participation. (Chen et al., Nov 2007, Jacobs et al., 2006, Watson et al., Apr 2014) (Census Bureau, 2021) AAPI are also heterogenous in other aspects such as wealth/income. (Ishimatsu et al., 2021, Center for American Progress, 2021)For example, the median annual earnings for full-time, year-round women workers vary widely by AAPI subpopulation with Asian Indian, Malaysian, and Taiwanese earning $70,000 and Southeast Asian and NHPI earning about half or less. (Center for American Progress, 2021)AAPI are also heterogenous in health burdens. For example, AAPI groups were substantially different in the prevalence of obesity, smoking, and diabetes (e.g., Filipinos had the highest age-sex adjusted prevalence of diabetes among AAPI, but also greater than all other racial/ethnic groups). (Gordon et al., 2019)Aggregated data contributes to the “model minority” stereotypes (e.g., having economic success; no health problems), but the realities are clear with disaggregated data. (Ishimatsu et al., 2021, Gordon et al., 2019)

COVID-19 morbidity and mortality are not as well studied for AAPI (vs. other major racial/ethnic populations). Data suggest that AAPI, as a whole or specific groups, experience high rates of COVID-19 cases and deaths. Based on electronic health record data of 50 million patients from 53 health systems across 21 states, Asians (vs. White) had higher hospitalization (15.9 vs 7.4 per 10,000) and death rates (4.3 vs. 2.3 per 10,000) from COVID-19 as of July 2020. (Rubin-Miller et al., 2021)Based on the National Center for Health Statistics’ data on attributable death from COVID-19 from February-October 2020, AAPI had higher attributable COVID-19 deaths than Whites among age groups 45–84; NHPI also had higher attributable mortality among those aged 15–24. (Chu et al., 2021)In San Francisco, Asian Americans had a four times higher case fatality rate vs. the overall population (5.2% vs. 1.3%) a few months into the pandemic. (Yan et al., 2020)The sparse disaggregated data for AAPI revealed that some groups had disproportionate COVID-19-related burdens. For example, based on data from 85,328 patients who tested for COVID-19 at New York City’s public hospital system, South Asians had the highest rates of positivity and hospitalization among all Asians, which was only second to Hispanics for positivity and Blacks for hospitalization; and, Chinese patients had the highest mortality rate of all groups and were about 1.5 times more likely to die from COVID-19 (vs. Whites). (Marcello et al., 2020)

Without important data about COVID-19 vaccine willingness, it remains unclear whether health disparities for AAPI, a population with existing inequalities in COVID-19 infection and mortality, (Marcello et al., 2020) may be exacerbated. As such, this study examined the proportion and factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine willingness among AAPI using data from a national ongoing, multilingual survey, COVID-19 Effects on the Mental and Physical Health of AAPI Survey Study (COMPASS).

2. Methods

2.1. Study Eligibility, recruitment and procedures

COMPASS is a cross-sectional, community-based national survey that assesses the COVID-19 effects on AAPI. To be eligible, participants must self-identify as AAPI; be able to read English/Chinese/Korean/Vietnamese; be ≥ 18 years old; and reside in the U.S. The survey is available online (https://compass.ucsf.edu/), phone, and limited in-person. This paper reports on 1,646 participants who completed the survey from October 24-December 11, 2020, which was selected as the cutoff date for this analysis since it was the first day that the FDA authorized a COVID-19 vaccine. (Food and Administration, 2021)Mean survey completion time was 21.6 (standard deviation (SD) = 15.5) minutes. There were 100 incomplete surveys. Single persons (vs. married) were significantly less likely to be incomplete responders. There were no significant differences by other background/social characteristics or by vaccine willingness. Each participant was provided an option of receiving a $10 gift card upon survey completion.

Convenience sampling was employed in this study. Participants heard about COMPASS through organizations who serve AAPI, personal/professional networks, social media, email/listservs, flyers, and ethnic media. COMPASS also leveraged the Collaborative Approach for AAPI Research and Education (CARE) Registry (Collaborative Approach for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders Research Education. CARE Registry for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders., 2021) to recruit participants.

Participants provided e-informed consent (n = 1,535) or verbal phone consent (n = 111). The survey used the Research Electronic Data Capture hosted at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). (Harris et al., Apr 2009, Harris et al., 2019)The World Health Organization’s process of translation and adaptation of instruments (World Health Organization. Process of translation and adaptation of instruments., 2018) was used to guide the translations of the study materials that were not already available in the targeted language(s).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Dependent variable

Willingness to Get the COVID-19 Vaccine Item was modified from another survey. (Neumann-Böhme et al., 2020)Participants were asked, “If a vaccine becomes available for COVID-19, would you get it?” Likert response options included: definitely yes; probably yes; unsure; probably no; and, definitely no.

2.2.2. Independent variables

Socio-demographic items were drawn from CARE. (Collaborative Approach for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders Research Education. CARE Registry for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders., 2021)Variables included race (Asian; NHPI; American Indian/Alaskan Native; Black/African American; White/Caucasian), cultural group (Asian Indian/Chinese/Huaren/Filipino/Korean/Japanese/Native Hawaiian/Samoan/Taiwanese/Vietnamese/Other/Mixed), sex (Female/Male; Other/Prefer not to answer), sexual orientation (Heterosexual/Not heterosexual/Prefer not to answer), year of birth, nativity (country of birth), years lived in the U.S., marital status (Single; Married; Living with a partner; Separated/Divorced; Widowed), employment (Full-time/Part-time/Homemaker/Unemployed/Retired/Other), education (option ranged from grade to Graduate school), and household income (options ranged from ≤$25,000 to ≥$200,0001). Participants were asked how well they could speak/read/write English (very well/well/some/a little bit/not at all).

Participants completed several existing surveys related to COVID-19 including the Coronavirus Impact Scale (CIS) related to changes in family income/employment (School, 2020) and COVID-19 status (Cawthon et al., 2020) (yes, no, unsure diagnosis). COVID-19 Vaccine Concerns (Neumann-Böhme et al., 2020) included the following response options (check all that apply): 1) I do not have any concerns; 2) I'm concerned about potential side effects; 3) I think COVID-19 vaccine may not be safe; 4) I do not think that COVID-19 is dangerous to my health; 5) I am against vaccination in general; 6) The best way is for nature to take its course; 7) I believe natural or traditional remedies; 8) I'm afraid of injections; 9) Religious reasons; and, 10) Other.

Participants answered duration of Shelter-in-Place (SIP) questions based on region, per the Census Bureau’s definition of region (Midwest/Northeast/South/West), (Bureau, 2021)which was obtained by converting the zip code, or internet protocol address in the case of missing zip codes (n = 188). SIP and Perceived Severity of COVID-19 items were developed by COMPASS.

General Health was measured by asking participants to indicate their health “today” on a scale from 0 (worst) to 100 (the best health you can imagine) using the EQ-5D (EuroQol, Dec 1990, Rabin and de Charro, Jul 2001) item, which was categorized into quintiles.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Chi-squared tests were used to examine the association between vaccine willingness, modeled as a 5-level categorical variable (definitely yes/probably yes/unsure/probably no/definitely no) and hypothesized factors associated with vaccine willingness, specifically race, cultural group, sex, sexual orientation, age, nativity, marital status, employment, education, household income, vaccine concerns, length of shelter in place, perceived severity of COVID-19, effect of coronavirus on family income, region, and general health status. Participants who responded that they could speak/read/write English less than very well (“some”, “a little bit”, or “not at all”) were categorized as having limited English proficiency (LEP). (Census Bureau, 2021)COVID-19 concerns were first classified as none, side-effects only, unsafe only, and multiple reasons for descriptive purposes. Then, it was further categorized as a binary variable (none or any concerns) in subsequent regression analyses to examine the association between vaccine willingness and any type of vaccine concerns.

This study used multinomial logistic regression to model the association between vaccine willingness, categorized as “definitely yes” (reference group), “probably yes”, “unsure/probably no/definitely no”, and these same factors. The “definitely yes” and “probably yes” responses differed conceptually. “Definitely” implied commitment whereas “probably” implied ambivalence and unwillingness to commit, which have differential associations with behavioral outcomes. (Baca-Motes et al., 2013, Rice et al., 2017)Consistent with previous research on vaccine willingness (Brandt et al., 2021, Ernesto, 2020)and guided by the data revealing differences in the two response groups in their proportion of participants with no vaccine concerns (44.1% vs, 9.7%, p < 0.01), the two responses were treated as separate outcome categories. The ‘unsure,’ ‘probably no,’ and ‘definitely no’ were combined into a single outcome category due to sample size considerations and the 3 groups appear to be similar in their associations with other factors. This study first conducted bivariate multinomial logistic regression to identify candidate variables for the final model. Since it was important not to miss variables that may become significant in the presence of others, this study retained variables that that attained a p-value of < 0.10 in bivariate analyses in the final modelLin et al., 2020–12–17 2020;14 (Zoran Bursac et al., 2008, Ranganathan et al., 2017). All statistical tests were two-sided. Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test (Hosmer and Lemesbow, 1980) indicated an acceptable fit of the final model (p = 0.27). The variables included in the final model were race, cultural group, sex, sexual orientation, age, nativity, marital status, employment status, income, vaccine concerns, and COVID severity. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS Software. (SAS Institute Inc, 2014)

2.4. Human subjects protection

This study was approved by UCSF’s Institutional Review Board (protocol 20-31925).

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

The mean age of participants (N = 1,646) was 40.6 years (SD: 15.8) and ranged from 18 to 88. Participants included 62.6% female, 90.0% heterosexuals, and 97.6% Asian Americans. Major cultural groups included ethnic Chinese (including persons from Hong Kong and Taiwan; 37.1%), Vietnamese (29.0%), and Korean (20.5%). Overall, 61.5% of participants were foreign-born who had lived in the U.S. an average of 47.8% of their lives (SD: 24.0%), 20% spoke limited English, and 73.3%completed the survey in English (Table 1)

Table 1.

Study Sample Characteristics (N = 1,646).

| Characteristics | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Willingness to be vaccinated | ||

| Definitely yes | 725 | 44.0 |

| Probably yes | 503 | 30.6 |

| Unsure | 295 | 17.9 |

| Probably no | 82 | 5.0 |

| No | 41 | 2.5 |

| Race | ||

| Asian | 1,607 | 97.6 |

| NHPI | 39 | 2.4 |

| Cultural Group | ||

| Asian-Indian | 28 | 1.7 |

| Ethnic Chinese1 | 611 | 37.1 |

| Filipino | 71 | 4.3 |

| Japanese | 29 | 1.8 |

| Korean | 337 | 20.5 |

| Native Hawaiian | 17 | 1.0 |

| Samoan | 13 | 0.8 |

| Vietnamese | 477 | 29.0 |

| Other/Mixed | 63 | 6.9 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1,028 | 62.5 |

| Male | 601 | 36.5 |

| Other/Decline2 | 17 | 1.0 |

| Sex -orientation | ||

| Heterosexual | 1,478 | 90.0 |

| Not heterosexual | 95 | 5.8 |

| Decline to state | 69 | 4.2 |

| Age | 40.6 (15.8)3; Range: 18 – 88 | |

| <30 | 535 | 32.5 |

| 30–39 | 339 | 20.6 |

| 40–49 | 237 | 14.4 |

| 50–59 | 295 | 17.9 |

| >60 | 240 | 14.6 |

| Nativity | ||

| US-born | 619 | 37.6 |

| Foreign-born | 1,012 | 61.5 |

| Percent of life lived in the U.S. | 47.8 (24.0)3; Range: 0 – 100 | |

| Don't know | 15 | 0.9 |

| Limited English Proficiency (LEP)4 | ||

| LEP in speaking | 335 | 20.4 |

| LEP in reading | 309 | 18.8 |

| LEP in writing | 337 | 20.5 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 564 | 34.3 |

| Married/Living with partner | 988 | 60.0 |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 83 | 5.0 |

| Declined | 11 | 0.7 |

| Employment Status | ||

| Full time | 735 | 44.7 |

| Part-time | 287 | 17.4 |

| Homemaker | 150 | 9.1 |

| Unemployed | 213 | 12.9 |

| Retired | 141 | 8.6 |

| Other/declined | 120 | 7.3 |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | 247 | 15.2 |

| Some college or technical school | 238 | 14.6 |

| Bachelor's degree | 633 | 39.0 |

| Master's degree or higher | 507 | 31.2 |

| Household Income ($) | ||

| ≤ 25,000 | 283 | 17.2 |

| > 25,000 –75,000 | 530 | 32.2 |

| >75,000 – 150,000 | 408 | 24.8 |

| > 150,000 | 258 | 15.7 |

| Decline to state | 167 | 10.2 |

| Tested positive for coronavirus | ||

| Yes | 33 | 2.0 |

| No | 1485 | 90.2 |

| Not sure | 108 | 6.7 |

| Missing | 20 | 1.2 |

| Concerns about COVID-19 vaccines | ||

| None | 386 | 23.5 |

| Side effects only | 562 | 34.1 |

| Unsafe only | 99 | 6.0 |

| Multiple reasons | 599 | 36.4 |

| Length of SIP5order | ||

| No order | 93 | 5.7 |

| < 1 month | 111 | 6.8 |

| 1 to < 2 months | 227 | 13.8 |

| 2 to < 3 months | 223 | 13.6 |

| 3 months or longer | 855 | 52.1 |

| Don't know | 132 | 8.0 |

| The severity of COVID where you live | ||

| A lot less | 146 | 8.9 |

| Somewhat less | 338 | 20.6 |

| About the same | 417 | 25.4 |

| Somewhat more | 502 | 30.6 |

| A lot more | 236 | 14.4 |

| Effect on family income/employment | ||

| No change | 587 | 35.9 |

| Mild | 554 | 33.9 |

| Moderate | 439 | 26.8 |

| Severe | 56 | 3.4 |

| Census Region | ||

| Midwest | 90 | 5.8 |

| Northeast | 142 | 8.6 |

| South | 305 | 18.5 |

| West | 1109 | 67.4 |

| Self-reported HealthQuintiles (range of health score) | 78.2 (15.7)3; Range: 1–100 | |

| Q1 (1 – 70) | 345 | 22.2 |

| Q2 (71 – 78) | 264 | 17.0 |

| Q3 (79 – 83) | 324 | 20.8 |

| Q4 (84 – 90) | 351 | 22.6 |

| Q5 (91 – 100) | 270 | 17.4 |

Ethnic Chinese includes mainland Chinese, Hongkonger, Taiwanese, and Huaren.

Other: n = 7; Decline: n = 6

Mean (SD)

English proficiency categorized as limited if speak/read/write English indicated as “some”, “a little” or “not at all”

SIP: Shelter-in-Place

3.2. COVID-19 analyses

As shown in Table 1, 44.0% of participants said, “definitely yes”, 30.6% “probably yes”, 17.9% “unsure”, 5.0% “probably no”, and 2.5% “definitely no” to getting the COVID-19 vaccine. About 24% reported no vaccine concerns. One in three (34.1%) were only concerned about side effects, 6.0% were only concerned about vaccine safety, and 36.4% reported multiple concerns. >64% reported that the COVID-19 had impacted their family income and employment. Over half (52.1%) indicated their SIP was ≥ 3 months; 45.0% perceived the COVID-19 severity of where they lived was “somewhat” to “a lot” more than other areas. Few (2.0%) said they had tested positive for COVID-19, 90.2% had tested negative, and 7.9% who were unsure or did not provide a response.

3.3. Bivariate analyses

In bivariate analyses, race, cultural group, sex, sexual orientation, age, nativity, marital status, income, vaccine concerns, and COVID-19 severity were significantly associated with vaccine willingness, but LEP, employment status, education, length of SIP order, effect on family income/employment, region, and self-reported health status, and caregiver status were not (Table 2).

Table 2.

Willingness to Be Vaccinated, by Participant Characteristics (N = 1,646).

| Characteristics | Definitely yes | Probably yes | Unsure | Probably no | Definitely no | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 725 | N = 503 | N = 295 | N = 82 | N = 41 | ||

| Race | <0.001 | |||||

| Asian | 715 (44.5) | 493 (30.7) | 288 (17.9) | 76 (4.7) | 35 (2.2) | |

| NHPI | 10 (25.6) | 10 (25.6) | 7 (18.0) | 6 (15.4) | 6 (15.4) | |

| Cultural Group | <0.001 | |||||

| Ethnic Chinese | 246 (40.3) | 216 (35.4) | 113 (18.5) | 24 (3.9) | 12 (2.0) | |

| Filipino | 27 (38) | 25 (35.2) | 13 (18.3) | 5 (7) | 1 (1.4) | |

| Korean | 114 (33.8) | 120 (35.6) | 62 (18.4) | 26 (7.7) | 15 (4.5) | |

| Vietnamese | 273 (57.2) | 105 (22) | 76 (15.9) | 19 (4) | 4 (0.8) | |

| Other/Mixed | 65 (43.3) | 37 (24.7) | 31 (20.7) | 8 (5.3) | 9 (6) | |

| Sex | <0.001 | |||||

| Female | 430 (41.8) | 304 (29.6) | 216 (21.0) | 49 (4.8) | 29 (2.8) | |

| Male | 288 (47.9) | 195 (32.5) | 76 (12.7) | 32 (5.3) | 10 (1.7) | |

| Other/Decline | 7 (41.2) | 4 (23.5) | 3 (17.7) | 1 (5.9) | 2 (11.8)) | |

| Sexual Orientation | 0.002 | |||||

| Heterosexual | 643 (43.5) | 457 (30.9) | 269 (18.2) | 72 (4.9) | 37 (2.5) | |

| Not heterosexual | 56 (59.0) | 26 (27.4) | 6 (6.3) | 7 (7.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Decline to state | 25 (36.2) | 19 (27.5) | 19 (27.5) | 2 (2.9) | 4 (5.8) | |

| Age | <0.001 | |||||

| <30 | 239 (44.7) | 173 (32.3) | 84 (15.7) | 29 (5.4) | 10 (1.9) | |

| 30–39 | 120 (35.4) | 125 (36.9) | 67 (19.8) | 17 (5.0) | 10 (3.0) | |

| 40–49 | 98 (41.4) | 69 (29.1) | 45 (19.0) | 16 (6.8) | 9 (3.8) | |

| 50–59 | 124 (42.0) | 82 (27.8) | 63 (21.4) | 17 (5.8) | 9 (3.1) | |

| >60 | 144 (60.0) | 54 (22.5) | 36 (15.0) | 3 (1.3) | 3 (1.3) | |

| Nativity | 0.007 | |||||

| Foreign-born | 475 (46.9) | 284 (28.1) | 180 (17.8) | 47 (4.6) | 26 (2.6) | |

| US-born | 246 (39.7) | 212 (34.3) | 113 (18.3) | 35 (5.7) | 13 (2.1) | |

| Don't know | 4 (26.7) | 7 (46.7) | 2 (13.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (13.3) | |

| LEP1in speaking | 0.622 | |||||

| Yes | 155 (46.3) | 93 (27.8) | 65 (19.4) | 14 (4.2) | 8 (2.4) | |

| No | 570 (43.5) | 410 (31.3) | 230 (17.5) | 68 (5.2) | 33 (2.5) | |

| LEP1in reading | 0.879 | |||||

| Yes | 141 (45.6) | 87 (28.2) | 58 (18.8) | 16 (5.2) | 7 (2.3) | |

| No | 584 (43.7) | 416 (31.1) | 237 (17.7) | 66 (4.9) | 34 (2.5) | |

| LEP1in writing | 0.929 | |||||

| Yes | 149 (44.2) | 99 (29.4) | 64 (19) | 18 (5.3) | 7 (2.1) | |

| No | 576 (44) | 404 (30.9) | 231 (17.7) | 64 (4.9) | 34 (2.6) | |

| Marital Status | 0.095 | |||||

| Single | 245 (43.4) | 173 (30.7) | 102 (18.1) | 31 (5.5) | 13 (2.3) | |

| Married/Living with partner | 422 (42.7) | 313 (31.7) | 176 (17.8) | 50 (5.1) | 27 (2.7) | |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 52 (62.6) | 13 (15.7) | 16 (19.3) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.2) | |

| Declined | 6 (54.5) | 4 (35.4) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Employment Status | 0.083 | |||||

| Full time | 310 (24.2) | 238 (32.4) | 124 (16.9) | 44 (6.0) | 19 (2.6) | |

| Part-time | 117 (40.8) | 85 (29.6) | 58 (20.2) | 17 (5.9) | 10 (3.5) | |

| Homemaker | 61 (40.7) | 46 (30.7) | 35 (23.3) | 6 (7.3) | 2 (1.3) | |

| Unemployed | 100 (47.0) | 64 (30.0) | 35 (16.4) | 10 (4.7) | 4 (1.9) | |

| Retired | 82 (58.2) | 34 (24.1) | 23 (16.3) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | |

| Other/declined | 55 (45.8) | 36 (30.0) | 20 (26.7) | 4 (4.9) | 5 (4.2) | |

| Education | 0.702 | |||||

| High school or less | 110 (44.5) | 74 (30.0) | 48 (19.4) | 12 (4.9) | 3 (1.2) | |

| Some college or technical school | 102 (42.9) | 71 (29.8) | 46 (19.3) | 12 (5.0) | 7 (2.9) | |

| Bachelor's degree | 271 (42.8) | 198 (31.3) | 121 (19.1) | 31 (4.9) | 12 (1.9) | |

| Master's degree or higher | 231 (45.6) | 155 (30.6) | 77 (15.2) | 26 (5.1) | 18 (3.6) | |

| Household Income ($) | 0.001 | |||||

| ≤ 25,000 | 156 (55.1) | 64 (22.6) | 50 (17.7) | 9 (3.2) | 4 (1.4) | |

| > 25,000 –75,000 | 223 (42.1) | 168 (31.7) | 101 (19.1) | 26 (4.9) | 12 (2.3) | |

| >75,000 – 150,000 | 170 (41.7) | 136 (33.3) | 68 (16.7) | 24 (5.9) | 10 (2.5) | |

| > 150,000 | 111 (43) | 86 (33.3) | 41 (15.9) | 17 (6.6) | 3 (1.2) | |

| Decline to state | 65 (38.9) | 49 (29.3) | 35 (21.0) | 6 (3.6) | 12 (7.2) | |

| Concerns about the Vaccine | <0.001 | |||||

| None | 320 (82.9) | 49 (12.7) | 12 (3.1) | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.8) | |

| Any | 405 (32.1) | 454 (36.0) | 283 (22.5) | 80 (6.4) | 38 (3.0) | |

| Length of SIP2order | 0.145 | |||||

| No order | 37 (39.8) | 29 (31.2) | 15 (16.1) | 10 (10.8) | 2 (2.2) | |

| < 1 month | 39 (35.1) | 46 (41.4) | 18 (16.2) | 4 (3.6) | 4 (3.6) | |

| 1 to < 2 months | 103 (45.4) | 69 (30.4) | 36 (15.9) | 12 (5.3) | 7 (3.1) | |

| 2 to < 3 months | 103 (46.2) | 74 (33.2) | 30 (13.5) | 13 (5.8) | 3 (1.4) | |

| 3 months or longer | 383 (44.8) | 247 (28.9) | 163 (19.1) | 39 (4.6) | 23 (2.7) | |

| Don't know | 57 (43.2) | 37 (28.0) | 32 (24.2) | 4 (3.0) | 2 (1.5) | |

| The severity of COVID where you live | 0.019 | |||||

| A lot less | 73 (50.0) | 28 (19.2) | 31 (21.2) | 8 (5.5) | 6 (4.1) | |

| Somewhat less | 163 (48.2) | 97 (28.7) | 57 (16.9) | 12 (3.6) | 9 (2.7) | |

| About the same | 168 (40.3) | 152 (36.5) | 72 (17.3) | 18 (4.3) | 7 (1.7) | |

| Somewhat more | 220 (43.8) | 161 (32.1) | 86 (17.1) | 25 (5.0) | 10 (2.0) | |

| A lot more | 100 (42.4) | 61 (25.9) | 48 (20.3) | 19 (8.1) | 8 (3.4) | |

| COVID-19 Effect on family income/employment | 0.122 | |||||

| No change | 263 (44.8) | 170 (29.0) | 103 (17.6) | 34 (5.8) | 17 (2.9) | |

| Mild | 228 (41.2) | 192 (34.7) | 102 (18.4) | 23 (4.2) | 9 (1.6) | |

| Moderate | 208 (47.4) | 125 (28.5) | 76 (17.3) | 20 (4.6) | 10 (2.3) | |

| Severe | 23 (41.1) | 14 (25.0) | 10 (17.9) | 5 (8.9) | 4 (7.1) | |

| Census Region | 0.116 | |||||

| Midwest | 37 (41.1) | 35 (38.9) | 15 (16.7) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.2) | |

| Northeast | 55 (38.7) | 45 (31.7) | 31 (21.8) | 7 (4.9) | 4 (2.8) | |

| South | 120 (39.3) | 98 (32.1) | 54 (17.7) | 25 (8.2) | 8 (2.6) | |

| West | 513 (46.3) | 325 (29.3) | 195 (17.6) | 49 (4.4) | 27 (2.4) | |

| Self-reported Health, quintiles | 0.411 | |||||

| Quintile 1 (lowest) | 154 (44.6) | 106 (30.7) | 58 (16.8) | 17 (4.9) | 10 (2.9) | |

| Quintile 2 | 122 (46.2) | 74 (28.0) | 53 (20.1) | 10 (3.8) | 5 (1.9) | |

| Quintile 3 | 149 (43.5) | 114 (35.1) | 53 (16.4) | 13 (4.0) | 3 (0.9) | |

| Quintile 4 | 150 (42.7) | 100 (28.5) | 72 (20.5) | 17 (4.8) | 12 (3.4) | |

| Quintile 5 (highest) | 119 (44.1) | 86 (31.9) | 39 (14.4) | 18 (6.7) | 8 (3.0) |

LEP: Limited English Proficiency

SIP: Shelter-in-Place

3.4. Multivariate analyses

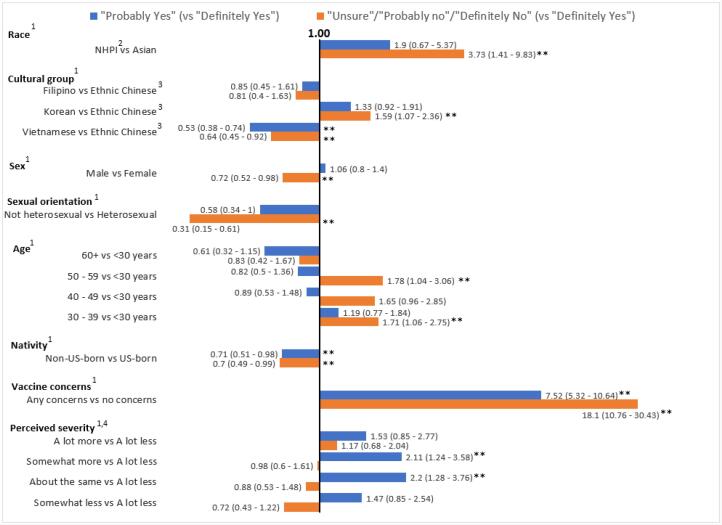

The adjusted multinomial models are shown in Table 3 and depicted in Fig. 1. NHPI were significantly more likely to be “unsure/probably no/definitely no” versus “definitely yes” about getting the vaccine (vs. Asian Americans) (adjusted Odds Ratio (aOR), 3.73 [95% CI, 1.41–9.83], P < 0.01).

Table 3.

Crude and Adjusted1 Odds Ratios (ORs) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) for Willingness to be Vaccinated.

| Crude OR | Adjusted OR1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Probably Yes | Unsure/ Probably No/Definitely No | Probably Yes | Unsure/Probably No/Definitely No | |

| Race | |||||

| Asian | 1607 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| NHPI2 | 39 | 1.45 (0.60–3.51) | 3.41 (1.57–7.39) | 1.90 (0.67–5.37) | 3.73 (1.41 – 9.83) |

| Cultural Group | |||||

| Ethnic Chinese3 | 524 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Filipino | 1.06 (0.59–1.87) | 1.16 (0.62–2.16) | 0.85 (0.45–1.61) | 0.81 (0.40–1.63) | |

| Korean | 337 | 1.20 (0.88–1.64) | 1.49 (1.07–2.09) | 1.33 (0.92–1.91) | 1.59 (1.08–2.36) |

| Vietnamese | 478 | 0.44 (0.33–0.59) | 0.60 (0.44–0.81) | 0.53 (0.38–0.74) | 0.64 (0.45–0.92) |

| Other/Mixed | 307 | 0.65 (0.42–1.01) | 1.22 (0.80–1.87) | 0.58 (0.35–0.98) | 1.00 (0.59–1.69) |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 1028 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Male | 601 | 0.96 (0.76–1.21) | 0.60 (0.46–0.78) | 1.06 (0.80–1.40) | 0.72 (0.52–0.98) |

| Sexual Orientation | |||||

| Heterosexual | 1478 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Non-Heterosexual | 95 | 0.65 (0.4–1.06) | 0.40 (0.21–0.73) | 0.58 (0.34 – 1.00) | 0.31 (0.15–0.61) |

| Age, years | |||||

| < 30 | 535 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 30 – 39 | 339 | 1.44 (1.05–1.98) | 1.52 (1.08–2.15) | 1.19 (0.77–1.84) | 1.71 (1.06–2.75) |

| 40 – 49 | 237 | 0.97 (0.68–1.40) | 1.39 (0.95–2.02) | 0.89 (0.53–1.48) | 1.65 (0.96–2.85) |

| 50 – 59 | 295 | 0.91 (0.65–1.28) | 1.40 (0.98–1.98) | 0.82 (0.50–1.36) | 1.78 (1.04–3.06) |

| ≥ 60 | 240 | 0.52 (0.36–0.75) | 0.57 (0.38–0.85) | 0.61 (0.32–1.15) | 0.83 (0.42–1.67) |

| Nativity | |||||

| US born | 1012 | Reference | N/Aa | Reference | Reference |

| Foreign born | 619 | 0.69 (0.55–0.88) | 0.81 (0.63–1.05) | 0.71 (0.51 – 0.99) | 0.70 (0.49–0.99) |

| LEP4in speaking | |||||

| Yes | 335 | 0.83 (0.63–1.11) | 0.97 (0.72–1.30) | N/A1 | N/A1 |

| No | 1311 | Reference | Reference | ||

| LEP4in reading | |||||

| Yes | 309 | 0.87 (0.65–1.16) | 1.00 (0.73–1.35) | N/A1 | N/A1 |

| No | 1337 | Reference | Reference | ||

| LEP4in writing | |||||

| Yes | 337 | 0.95 (0.71–1.26) | 1.05 (0.78–1.41) | N/A1 | N/A1 |

| No | 1309 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Marital Status | |||||

| Single | 564 | 0.95 (0.75–1.21) | 0.99 (0.77 – 1.29) | 0.88 (0.60 – 1.30) | 1.23 (0.81 – 1.87) |

| Married/Living with partner | 988 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 83 | 0.34 (0.18 – 0.63) | 0.58 (0.33 – 1.01) | 0.59 (0.29 – 1.18) | 0.71 (0.36 – 1.37) |

| Employment Status | |||||

| Full time | 735 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Part-time | 287 | 0.95 (0.68 – 1.31) | 1.20 (0.86 – 1.68) | 1.19 (0.81 – 1.75) | 1.30 (0.87 – 1.96) |

| Homemaker | 150 | 0.98 (0.65 – 1.49) | 1.17 (0.76 – 1.80) | 1.05 (0.63 – 1.75) | 0.96 (0.57 – 1.64) |

| Unemployed | 213 | 0.83 (0.58 – 1.19) | 0.81 (0.55 – 1.20) | 1.09 (0.71 – 1.67) | 0.92 (0.58 – 1.46) |

| Retired | 141 | 0.54 (0.35 – 0.83) | 0.50 (0.31 – 0.82) | 1.14 (0.58 – 2.21) | 1.08 (0.53 – 2.23) |

| Other/declined | 120 | 0.85 (0.54 – 1.34) | 0.87 (0.54 – 1.42) | 0.98 (0.57 – 1.67) | 0.92 (0.51 – 1.66) |

| Education | |||||

| ≤ High school | 247 | Reference | Reference | N/A1 | N/A1 |

| Some college or technical | 238 | 1.04 (0.68–1.58) | 1.11 (0.72–1.73) | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 633 | 1.09 (0.77–1.54) | 1.06 (0.73–1.52) | ||

| ≥ Master’s degree | 507 | 1.00 (0.70–1.43) | 0.92 (0.63–1.34) | ||

| Household Income ($) | |||||

| ≤ 25,000 | 283 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| > 25,000 –75,000 | 530 | 1.84 (1.29–2.61) | 1.54 (1.08–2.22) | 1.24 (0.82–1.87) | 1.10 (0.71 – 1.71) |

| >75,000 – 150,000 | 408 | 1.95 (1.35–2.82) | 1.49 (1.01–2.18) | 1.16 (0.75–1.78) | 0.94 (0.60–1.49) |

| > 150,000 + | 127 | 1.89 (1.26–2.83) | 1.36 (0.89–2.09) | 1.19(0.72–1.97) | 0.87 (0.50–1.49) |

| Concerns about the Vaccine | |||||

| None | 386 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Any | 1260 | 7.32 (5.27–10.17) | 18.64 (11.23–30.94) | 7.52 (5.32–10.64) | 18.10 (10.76–30.43) |

| Length of SIP5Order | |||||

| No order | 93 | Reference | Reference | N/A1 | N/A1 |

| < 1 month | 111 | 1.51 (0.79–2.87) | 0.91 (0.45–1.84) | ||

| 1 - < 2 months | 227 | 0.86 (0.48–1.52) | 0.73 (0.40–1.33) | ||

| 2 - < 3 months | 223 | 0.92 (0.52–1.62) | 0.61 (0.33–1.12) | ||

| ≥ 3 months | 855 | 0.82 (0.49–1.37) | 0.81 (0.48–1.36) | ||

| Severity of COVID-19 | |||||

| A lot less | 146 | Reference | Reference | Reference | N/A1 |

| Somewhat less | 338 | 1.55 (0.94–2.57) | 0.78 (0.49–1.23) | 1.47 (0.85–2.54) | 0.72 (0.43–1.22) |

| About the same | 417 | 2.36 (1.45–3.84) | 0.94 (0.60–1.47) | 2.20 (1.28–3.76) | 0.88 (0.53–1.48) |

| Somewhat more | 502 | 1.91 (1.18–3.09) | 0.89 (0.58–1.38) | 2.11 (1.24–3.58) | 0.98 (0.60–1.61) |

| A lot more | 236 | 1.59 (0.93–2.73) | 1.22 (0.76–1.96) | 1.53 (0.85–2.77) | 1.17 (0.68–2.04) |

| COVID-19 Effect on Family Income/employment | |||||

| No change | 587 | Reference | Reference | N/A1 | N/A1 |

| Mild | 554 | 1.30 (0.99–1.71) | 1.00 (0.75–1.34) | ||

| Moderate | 439 | 0.93 (0.69–1.25) | 0.87 (0.64–1.18) | ||

| Severe | 56 | 0.94 (0.47–1.88) | 1.41 (0.75–2.67) | ||

| Census Region | |||||

| Midwest | 90 | 1.49 (0.92–2.42) | 0.92 (0.51–1.65) | N/A1 | N/A1 |

| Northeast | 142 | 1.29 (0.85–1.96) | 1.45 (0.94–2.22) | ||

| South | 305 | 1.29 (0.95–1.74) | 1.37 (1.00–1.88) | ||

| West | 1109 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Self-reported Health, quintiles | |||||

| Quintile 1 (lowest) | 345 | Reference | Reference | N/A1 | N/A1 |

| Quintile 2 | 264 | 0.88 (0.60 – 1.29) | 1.01 (0.68–1.50) | ||

| Quintile 3 | 324 | 1.18 (0.83 – 1.67) | 0.89 (0.60 – 1.31) | ||

| Quintile 4 | 351 | 0.97 (0.68 – 1.38) | 1.22 (0.85 – 1.76) | ||

| Quintile 5 (highest) | 270 | 1.05 (0.72 – 1.52) | 0.99 (0.67 – 1.48) | ||

Adjusted for age, sex, race, cultural group, sexual orientation, nativity, COVID-19 severity, marital status, employment status, vaccine concerns

NHPI: Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders

Ethnic Chinese includes mainland Chinese, Hongkonger, Taiwanese, and Huaren.

English proficiency categorized as limited if speak/read/write English indicated as “some”, “a little” or “not at all”

SIP: Shelter-in-Place

Fig. 1.

Adjusted Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals for Willingness to be Vaccinated (N = 1,646) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021) Reference groups for independent variables: Race- Asian; Cultural group- Ethnic Chinese; Sex- Female; Sexual orientation- Heterosexual; Age- < 30 years; Nativity- US-born; Vaccine concerns- No concerns; Perceived severity- A lot less. (Food and Administration, 2021) NHPI: Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders. Ethnic Chinese includes mainland Chinese, Hongkonger, Taiwanese, and Huaren. (Food and Administration, 2021) Perceived severity: How would you rate the severity of COVID-19 outbreak at where you live in comparison to other locations in the US? ** p < 0.05.

Compared to Chinese, the adjusted OR for Koreans being “unsure/probably no/definitely no” versus “definitely yes” was 1.59 [95% CI, 1.08–2.36], P = 0.02 and for Vietnamese was 0.64 [95% CI, 0.45–0.92], P < 0.01. There were no statistically significant differences between Filipinos and Chinese. In post-hoc testing, compared to Koreans, Vietnamese were significantly less likely to be “unsure/probably no/definitely no” (aOR, 0.40 [95% CI, 0.27–0.62], P < 0.01 and “probably yes” about taking the vaccine, versus “definitely yes” (aOR, 0.40 [95% CI, 0.27–0.59], P < 0.01). There were no statistically significant differences between Filipinos and Vietnamese or Koreans (data not shown).

Sex and sexual orientation remained significantly associated with vaccine willingness in the adjusted model, with males (vs. females) and non-heterosexuals (vs. heterosexuals) less likely to be “unsure/probably no/definitely no” versus “definitely yes”.

Compared to those aged < 30 years, those aged 30–39 years were significantly more likely to state they were “unsure/probably no/definitely no” about getting the vaccine compared to those who said “definitely yes” (aOR,1.71 [95% CI, 1.06–2.75], P = 0.03). Those aged 30–39 years were significantly more likely to report “probably yes” about getting the vaccine compared to “definitely yes” (aOR, 1.44 [95% CI, 1.05–1.98], P < 0.01). Those aged 50–59 years were significantly more likely than those < 30 years to state they were “unsure/probably no/definitely no” about getting the vaccine (aOR, 1.78 [95% CI, 1.04–3.06], P = 0.04) compared to “definitely yes”.

Vaccine concerns (had concerns vs. not) were significantly associated with vaccine willingness: those who reported “unsure/probably no/definitely no” versus “definitely yes” (aOR, 18.10 [95% CI, 10.76–30.43], P < 0.01), and for those who reported “probably yes” versus “definitely yes” (aOR, 7.52 [95% CI, 5.32–10.64], P < 0 0.01).

4. Discussion

This paper reports willingness to receive the vaccine and factors related to willingness among 1,646 AAPI from a national multi-lingual survey before the safety and efficacy data were widely known, thus future research may investigate the potential changes in attitudes and factors associated with vaccination willingness. Results highlight the heterogeneity in vaccine willingness for AAPI. The study sought to provide these data to inform public health officials, community partners, and health care systems of potential outreach targets to improve vaccine willingness and thereby provide a defense against COVID-19 that has disproportionately affected AAPI. (Rubin-Miller et al., 2021, Chu et al., 2021)

From a health equity lens, the study provides disaggregated data for AAPI, which is significant because such data are scarce. These findings are among the first to reveal that AAPI groups are heterogeneous in COVID-19 vaccine willingness. This study found that NHPI were significantly less willing to receive the vaccine (vs. Asian Americans). This finding is critical as several U.S. states with large numbers of NHPI report higher rates of COVID-19 infections (vs. other racial/ethnic groups). (Kaholokula et al., 2020)Low vaccine willingness and high infection rates highlight the need for concentrated efforts to address COVID-19 health inequities for NHPI. The study also found that Korean Americans were less willing to receive the COVID-19 vaccine (vs. both Chinese and Vietnamese Americans), consistent with a global online survey that found that 25% of South Koreans (vs. 20% of respondents from China) indicated little/low vaccine intention. (Ipsos. Global attitudes on a COVID-19 vaccine: Ipsos survey for The World Economic Forum., 2021)The study found that Vietnamese Americans were more willing to receive the COVID-19 vaccine (vs. Chinese Americans), and such differences could not be explained by vaccine concerns or other correlates examined in this study. Results suggest targeted efforts for outreach to NHPI and Korean Americans, who were less willing to get the COVID-19 vaccine. Outreach in these languages and in areas where NHPI and Korean Americans are located may help to increase vaccine uptake. Public health campaigns with spokespersons from these cultural backgrounds may also help. Providers serving NHPI, Korean Americans, women and age groups that were less willing to receive the vaccine, could educate their patients about the importance of COVID-19 vaccination.

Overall, 25.4% of participants reported that they were unsure/unlikely to receive the vaccine, which closely mirrors the proportion (27%) reported in a national poll. (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020)This study also found that those aged 30–39 (vs. < 30) were significantly less likely to be willing to get the vaccine, which is consistent with prior studies that found that being younger in age (Fisher et al., 2020) (e.g., 30–49) (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020)was associated with vaccine hesitancy. However, the anomaly study finding was that those 50–59 (vs. aged < 30) were also less likely to be willing to get the vaccine; future research may investigate this association. Similar to prior findings, (Fisher et al., 2020, Callaghan et al., 2020, Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020, Reiter et al., 2020)those who reported having any vaccine concerns (vs. none) were less willing to receive the vaccine.

Consistent with another survey, this study found that men are more willing to get the vaccine than women. (Callaghan et al., 2020)This study also found that non-heterosexual AAPI were less likely to state that they were unwilling to get the vaccine (vs. heterosexual). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and intersex (LGBTQI + ) individuals experience health inequities that have become heightened with the pandemic. Reasons for greater vaccine willingness may be related to historical experiences of discrimination and health inequity such as lack of health insurance, (Kline, 2020)which may motivate individuals in sexual minority groups to access vaccination to reduce their risk for COVID-related morbidity/mortality. Greater vaccine willingness may also be related to the increased risk of infection that LGBTQI + individuals perceive with lower self-reported health status, higher rates of substance use, higher rates of HIV/AIDS (and compromised immune systems), and worse mental health (vs. general population). (Kline, 2020, Cancer, 2020, Pedrosa et al., 2020, Salerno et al., Aug 2020)Furthermore, in a poll of 174 adults who identified as LGBT, 75% viewed vaccination as a responsibility to protect others (vs. 48% of non-LGBT individuals). (Kaiser Family Foundation. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on LGBT People., 2021)

It is possible that participants who indicated that they were “unsure/probably no/definitely no” about getting the vaccine were waiting to receive additional information that could alleviate their concerns; this group can be considered the “wait and see” group. (National Academies of Sciences, 2020)A potential model that may be used as a guide to increase COVID-19 vaccine willingness is the World Health Organization BeSD Increasing Vaccination Model, (National Academies of Sciences, 2020)which stipulates “what people think and feel” (e.g., perceived risk) and the “social processes” (e.g., provider recommendations; social norms) lead up to the core of the model, “motivation” (e.g., willingness; hesitancy). By addressing “motivation” and barriers (e.g., cost; availability), individuals may be more likely to get the COVID-19 vaccine. (January, 2021)Culturally appropriate/tailored strategies are likely to play pivotal roles in vaccine uptake. For example, faith-based organizations may be important community partners for COVID-19 vaccine uptake, as they have been for other health promotion activities such hypertension prevention. (Kwon et al., 2017)Removing access barriers will be essential for the vaccine rollout. By providing multilingual helpline and resources and being geographically relevant (i.e., taking services to neighborhoods with higher density of Asian Americans), Asian Health Services (a Federally Qualified Health Center in the San Francisco Bay Area) saw an increase in both COVID-19 testing and vaccinations among Asian American individuals. (Quach et al., 2021)On a national scale, National Asian Pacific Center on Aging (NAPCA, a community partner of COMPASS) operates a helpline available in 6 AAPI languages to provide information and support with booking vaccination appointments. (Center, 2021)Additionally, recommendations from research for other types of vaccine uptake (e.g., HPV vaccine among Asian Americans) may be useful to apply in COVID-19 vaccine intention/uptake for AAPI (e.g., culturally appropriate educational information; family involvement). (Vu et al., 2020)

5. Limitations

There are a few limitations. First, this study is not an etiological study; however, future work may include repeated measures to assess change over time. Second, due to feasibility, not all AAPI languages were available, thus, limiting the ability to generalize findings to all AAPI. Thirdthe online survey limits the potential reach to AAPI with limited access to digital technology; however, COMPASS does offer toll-free numbers in the target languages. Fourth, the sample size for certain AAPI groups (e.g., NHPI; Asian Indians) were small; COMPASS’ present targeted outreach with NHPI and Asian Indian community partners may help to improve this. A strength of COMPASS is that community partners were engaged to help in the outreach/recruitment, and administration, which research has shown to be critical to successful AAPI. (Rabinowitz and Gallagher-Thompson, 2010, Grill and Galvin, 2014)

6. Conclusions

Strong willingness to get the COVID-19 vaccine is vital for personal, public, economic, and social health. (National Academies of Sciences, 2020) More than 25% of the participants indicated an unwillingness to get the COVID-19 vaccine; however, unwillingness significantly differed across AAPI groups, which underscore the need for data disaggregation, as an understanding of vaccine unwillingness (among a variety of other important outcomes) may be obscured by lumping AAPI together. A multi-pronged approach in culturally appropriate and tailored health communication and education is critical to achieve the goal of health equity for AAPI especially given the high burden of COVID-19-related morbidity and mortality among AAPI. (Marcello et al., 2020)Additionally, COMPASS was a multi-lingual survey available in multiple mediums (online, phone, and limited in-person) that allowed for a diverse sample of AAPI. Future research is encouraged to include non-English languages as well to help diversify their samples.

7. Role of the Funder/Sponsor

The funding source has no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Data Sharing Statement

We will follow the NIH data sharing policy, https://grants.nih.gov/grants/policy/data_sharing/.

Funding

This study was supported by a COVID-19 administrative supplement grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging (NIH/NIA) (3R24AG063718-02S1). Part of < named co-author > effort was supported by NIH/NIA R01AG067541.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Van M. Ta Park: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Investigation, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Marcelle Dougan: Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Oanh L. Meyer: Project administration, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Bora Nam: Project administration, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Marian Tzuang: Project administration, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Linda G. Park: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Quyen Vuong: Project administration. Janice Y. Tsoh: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We want to acknowledge our community partners who have helped in the outreach and administration of COMPASS.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. United States COVID-19 Cases and Deaths by State. Accessed May 14, 202https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#cases_casesper100klast7days.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine. Accessed January 9, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/pfizer-biontech-covid-19-vaccine.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine. Accessed January 9, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/moderna-covid-19-vaccine.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Janssen COVID-19 Vaccine. Accessed May 14, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/janssen-covid-19-vaccine.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Vaccinations in the United States. Accessed June 29, 2021. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccinations.

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Herd immunity, lockdowns and COVID-19. Accessed Janaury 10, 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/herd-immunity-lockdowns-and-covid-19.

- Fisher K.A., Bloomstone S.J., Walder J., Crawford S., Fouayzi H., Mazor K.M. Attitudes Toward a Potential SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine : A Survey of U.S. Adults. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(12):964–973. doi: 10.7326/M20-3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan T, Moghtaderi A, Lueck JA, et al. Correlates and Disparities of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. August 5, 2020 2020.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: December 2020. Accessed January 9, 2021. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/report/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-december-2020/.

- Reiter P.L., Pennell M.L., Katz M.L. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among adults in the United States: How many people would get vaccinated? Vaccine. 2020;38(42):6500–6507. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head K.J., Kasting M.L., Sturm L.A., Hartsock J.A., Zimet G.D. A National Survey Assessing SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination Intentions: Implications for Future Public Health Communication Efforts. Sci Commun. 2020;42(5):698–723. doi: 10.1177/1075547020960463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. Key facts about Asian Americans, a diverse and growing population. Accessed January 9, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/09/08/key-facts-about-asian-americans/.

- Franklin Templeton-Gallup Economics of Recovery Study. Roundup of Recent Gallup Data on Vaccines. Accessed January 10, 2021. https://news.gallup.com/opinion/gallup/324527/roundup-recent-gallup-data-vaccines.aspx.

- Pew Research Center. Intent to Get a COVID-19 Vaccine Rises to 60% as Confidence in Research and Development Process Increases. Accessed January 10, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2020/12/03/intent-to-get-a-covid-19-vaccine-rises-to-60-as-confidence-in-research-and-development-process-increases/.

- Office of Management and Budget. Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity. Accessed May 12, 2021. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/omb/fedreg_1997standards.

- Chen A.H., Youdelman M.K., Brooks J. The legal framework for language access in healthcare settings: Title VI and beyond. J Gen Intern Med. Nov 2007;22(Suppl 2):362–367. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0366-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs E., Chen A.HM., Karliner L.S., Agger-Gupta niels, Mutha S. The need for more research on language barriers in health care: a proposed research agenda. Milbank Q. 2006;84(1):111–133. doi: 10.1111/milq.2006.84.issue-110.1111/j.1468-0009.2006.00440.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson J.L., Ryan L., Silverberg N., Cahan V., Bernard M.A. Obstacles and opportunities in Alzheimer's clinical trial recruitment. Health Aff (Millwood). Apr 2014;33(4):574–579. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Language Spoken At Home. Accessed February 5, 2021. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/newsroom/press-kits/2017/esri/esri_uc2017_language_spoken_at_home.pdf.

- Ishimatsu J, Harrison A, Watsky C. The Economic Reality of The Asian American Pacific Islander Community Is Marked by Diversity and Inequality, Not Universal Success. Prosperity Now,. Accessed May 12, 2021. https://prosperitynow.org/resources/economic-reality-asian-american-pacific-islander-community-marked-diversity-and.

- Center for American Progress. The Economic Status of Asian American and Pacific Islander Women. Accessed May 12, 20https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/reports/2021/03/04/496703/economic-status-asian-american-pacific-islander-women/.

- Gordon NP, Lin TY, Rau J, Lo JC. Aggregation of Asian-American subgroups masks meaningful differences in health and health risks among Asian ethnicities: an electronic health record based cohort study. BMC Public Health. Nov 25 2019;19(1):1551. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-7683-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rubin-Miller L, Alban C, Artiga S, Sullivan S. COVID-19 Racial Disparities in Testing, Infection, Hospitalization, and Death: Analysis of Epic Patient Data. Kaiser Family Foundation,. Accessed January 11, 2021. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/covid-19-racial-disparities-testing-infection-hospitalization-death-analysis-epic-patient-data/.

- Chu J.N., Tsoh J.Y., Ong E., Ponce N.A. The Hidden Colors of Coronavirus: the Burden of Attributable COVID-19 Deaths. J Gen Intern Med. Jan 22. 2021;36(5):1463–1465. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06497-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan BW, Ng F, Chu J, Tsoh J, Nguyen T. Asian Americans Facing High COVID-19 Case Fatality Health Affairs Blog blog. May 14, 2020.

- Marcello RK, Dolle J, Tariq A, et al. Disaggregating Asian Race Reveals COVID-19 Disparities among Asian Americans at New York City’s Public Hospital System. medRxiv. 2020:2020.11.23.20233155. doi:10.1101/2020.11.23.20233155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Marcello RK, Dolle J, Tariq A, et al. Disaggregating Asian Race Reveals COVID-19 Disparities among Asian Americans at New York City’s Public Hospital System. medRxiv. 2020;2021(January 9)doi:https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.23.20233155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Collaborative Approach for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders Research & Education. CARE Registry for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. Accessed January 9, 2021. https://careregistry.ucsf.edu/.

- Harris P.A., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., Conde J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. Apr 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris P.A., Taylor R., Minor B.L., Elliott V., Fernandez M., O'Neal L., McLeod L., Delacqua G., Delacqua F., Kirby J., Duda S.N. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Process of translation and adaptation of instruments. Accessed September 11, 2018. http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/.

- Neumann-Böhme S., Varghese N.E., Sabat I., Barros P.P., Brouwer W., van Exel J., Schreyögg J., Stargardt T. Once we have it, will we use it? A European survey on willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Eur J Health Econ. 2020;21(7):977–982. doi: 10.1007/s10198-020-01208-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. Coronavirus Impact Scale. Accessed April 28, 2020. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/dr2/Coronavirus_Impact_Scale.pdf.

- P.M. Cawthon E.S. Orwoll K.E. Ensrud J.A. Cauley S.B. Kritchevsky S.R. Cummings A. Newman Assessing the impact of the covid-19 pandemic and accompanying mitigation efforts on older adults 75 9 2020 2020 e123 e125 10.1093/gerona/glaa099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bureau USC. Census Regions and Divisions of the United States. Available at https://www2censusgov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdivpdf Accessed January 29, 2021.

- EuroQol G. EuroQol–a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. Dec 1990;16(3):199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabin R., de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med. Jul 2001;33(5):337–343. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Language Use. Accessed January 31, 2021. https://www.census.gov/topics/population/language-use.html.

- Baca-Motes K., Brown A., Gneezy A., Keenan E.A., Nelson L.D. Commitment and behavior change: Evidence from the field. Journal of Consumer Research. 2013;39(5):1070–1084. [Google Scholar]

- Rice S.L., Hagler K.J., Martinez-Papponi B.L., Connors G.J., H.D. D. Ambivalence about behavior change: Utilizing motivational interviewing network of trainers' perspectives to operationalize the construct. Addiction Research & Theory. 2017;25(2):154–162. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt E.J., Rosenberg J., Waselewski M.E., Amaro X., Wasag J., Chang T. National Study of Youth Opinions on Vaccination for COVID-19 in the U.S. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2021–05-01 2021;68(5):869–872. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yulan Lin Zhijian Hu Qinjian Zhao Haridah Alias Mahmoud Danaee Li Ping Wong Ernesto T. A. Marques Understanding COVID-19 vaccine demand and hesitancy: A nationwide online survey in China PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 14 12 2020–12-17 2020;14(12):e0008961. e0008961 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zoran Bursac C Heath Gauss David Keith Williams David W Hosmer 3 1 2008 10.1186/1751-0473-3-17.

- Ranganathan P., Pramesh C.S., Aggarwal R. Common pitfalls in statistical analysis: Logistic regression. Perspect Clin Res. Jul-Sep. 2017;8(3):148–151. doi: 10.4103/picr.PICR_87_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D.W. Hosmer S. Lemesbow Goodness of fit tests for the multiple logistic regression model Communications in Statistics - Theory and Methods. 9 10 1980/01/01 1980, 1043 1069 10.1080/03610928008827941.

- SAS Institute Inc . SAS Institute Inc; Cary, NC: 2014. SAS® OnDemand for Academics: User's Guide. [Google Scholar]

- Kaholokula J.K., Samoa R.A., Miyamoto R.E.S., Palafox N., Daniels S.A. COVID-19 Special Column: COVID-19 Hits Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Communities the Hardest. Hawaii J Health Soc Welf. 2020;79(5):144–146. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ipsos. Global attitudes on a COVID-19 vaccine: Ipsos survey for The World Economic Forum. Accessed February 7, 2021. https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2020-12/global-attitudes-on-a-covid-19-vaccine-december-2020-report.pdf.

- Kline N.S. Rethinking COVID-19 Vulnerability: A Call for LGTBQ+ Im/migrant Health Equity in the United States During and After a Pandemic. Health Equity. 2020;4(1):239–242. doi: 10.1089/heq.2020.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National LGBT Cancer Network. Open letter about coronavirus and the LGBTQ+ communities: Over 100 organizations ask media & health officials to weigh added risk. Updated March 11, 2020. https://cancer-network.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Press-Release-Open-Letter-LGBTQ-Covid19-17.pdf.

- Pedrosa A.L., Bitencourt L., Fróes A.Cláudia.F., Cazumbá M.Luíza.B., Campos R.G.B., de Brito S.B.C.S., Simões e Silva A.C. Emotional, Behavioral, and Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front Psychol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.566212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salerno J.P., Williams N.D., Gattamorta K.A. LGBTQ populations: Psychologically vulnerable communities in the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma. Aug 2020;12(S1):S239–S242. doi: 10.1037/tra0000837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on LGBT People. Accessed May 16, 2021. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/the-impact-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-on-lgbt-people/.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Framework for Equitable Allocation of COVID-19 Vaccine. In: Gayle H, Foge W, Brown L, Kahn B, eds. Framework for Equitable Allocation of COVID-19 Vaccine. National Academies Press; 2020:chap 7, Achieving Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccine. [PubMed]

- Accessed January 9 http://awareness.who.int/immunization/programmes_systems/vaccine_hesitancy/en/#:~:text=The%20Increasing%20Vaccination%20Model%20(see 2021 the%20motivation%20and%20get%20vaccinated.

- Kwon SC, Patel S., Choy C., Zanowiak J., Rideout C., Yi S., Wyatt L., Taher MD, Garcia-Dia MJ, Kim SS, Denholm TK, Kavathe R., Islam NS. Implementing health promotion activities using community-engaged approaches in Asian American faith-based organizations in New York City and New Jersey. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7(3):444–466. doi: 10.1007/s13142-017-0506-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quach T, Ethoan LN, Liou J, Ponce NA. A Rapid Assessment of the Impact of COVID-19 on Asian Americans: Cross-sectional Survey Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. Jun 11 2021;7(6):e23976. doi:10.2196/23976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- National Asian Pacific Center on Aging. NAPCA launches a national COVID-19 vaccine resource map and in-language support to book vaccination appointments. Accessed June 29, 2021. https://napca.org/news/press-releases/napca-launches-a-national-covid-19-vaccine-resource-map-and-in-language-support-to-book-vaccination-appointments/.

- Vu M., Berg C.J., Escoffery C., Jang H.M., Nguyen T.T., Travis L., Bednarczyk R.A. A systematic review of practice-, provider-, and patient-level determinants impacting Asian-Americans' human papillomavirus vaccine intention and uptake. Vaccine. 2020;38(41):6388–6401. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.07.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz Y.G., Gallagher-Thompson D. Recruitment and retention of ethnic minority elders into clinical research. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. Jul-Sep. 2010;24(Suppl):S35–S41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill J.D., Galvin J.E. Facilitating Alzheimer disease research recruitment. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. Jan-Mar. 2014;28(1):1–8. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]