Abstract

Objective

To develop and validate a midwifery-led task list in the task-shifting context.

Design

An extensive literature review followed by a two-iterative Delphi survey.

Setting

Twenty university hospitals, three non-university hospitals and four university colleges from nine provincial regions of China.

Participants

Purposive non-probability sampling of a national panel of experts in maternal healthcare, obstetrics, nursing and midwifery. Experts in the panel were asked to rate each midwifery service item regarding importance, feasibility and advancement on a 5-point scale, in order to determine those best suited for midwifery-led practice in China.

Results

Two rounds of Delphi surveys were completed before consensus was achieved, with effective response rate ranging from 96.4% (27/28) to 100% (27/27), indicating a high positive coefficient of the experts. The authority coefficient of experts was 0.882, indicating the high reliability of this study. The Kendall harmony coefficient (W) in the two rounds of consultations was 0.196 (p<0.001) and 0.324 (p<0.001), respectively. A detailed, three-level midwifery-led task list was developed, including 3 domains of midwifery practice (first-level indicators), 13 types of task (second-level indicators) and 58 midwifery service items (third-level indicators). The 3 domains of midwifery practice involved the appropriate scope of practice for Chinese midwives, including antenatal care, intrapartum care and postnatal care. The 58 service items embraced core components of caring task in the Chinese midwifery profession.

Conclusion

This study outlines the first midwifery-led task list that defines clearly the Chinese midwives’ scope of practice. It will provide a foundational framework for future midwifery practice in China and abroad, and can be used to inform the design of midwifery-led task shifting interventions in various maternity settings.

Keywords: organisation of health services, obstetrics, perinatology, public health, health services administration & management

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first multicentre Delphi study to develop and validate a midwifery-led task list that is tailored to midwifery practice in the task-shifting context.

The new task list expands Chinese midwives’ current scope of practice and provides a foundational framework for the development of specific midwifery-led task shifting interventions in maternity settings.

We recruited a national panel of Chinese experts to formulate this task list, thus causing a limitation of its generalisability and applicability to other cultural contexts. Additionally, this midwifery service task list is still at a theoretical level and no practical experiences have been gained yet.

Introduction

Nurses and midwives are critical for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals and Universal Healthcare Coverage.1 2 Task shifting has been identified as a strategy by the WHO to optimise health worker roles to improve access to key maternal and newborn interventions.3 The WHO defined ‘task shifting’ as the redistribution of tasks between healthcare workers for improving healthcare coverage and quality.4 Deller et al defined it as either developing a cadre of care providers to perform tasks which are normally performed by professionals with higher qualifications; or extending the scope of practice of an existing cadre to perform extra tasks.5

As the primary professional group to provide midwifery,6 midwives are a cadre of health worker familiar with the concept of task shifting.7 8 Evidence derived from randomised controlled trials and from practical experience demonstrates that midwifery care and task shifting in midwifery has essential contribution to high quality sexual, reproductive, maternal and newborn health care services.9–11 Midwives have the potential to provide cost effective and excellent quality of care, which increases access to and availability of midwifery services, and leads to positive health outcomes.12–14

The International Confederation of Midwives (ICM) defines the work of midwives15 and core competencies and standards for their education and practice.16 Internationally a midwife is recognised as a responsible and accountable health professional who works in partnership with women to provide the necessary support, care and advice from the point at which a woman or girl becomes sexually active, through pregnancy, childbirth and the postnatal period.15 The midwife has an important task in health counselling and education, such as antenatal education and preparation for parenthood.17 This work may also extend to women’s health, sexual or reproductive health and child care.15 According to the WHO,3 promotion of maternal and newborn heath interventions, administration of oxytocin and misoprostol, and oral supplement distribution are identified as being within the competency of midwives. In addition, the WHO also recommended the use of midwives to undertake tasks including administration of external cephalic version, antibiotics for preterm prelabour rupture of membranes, contraceptive service and delivery of other specific interventions.

The international midwife-led model of care advocates woman-centred philosophy of care and is based on the premise that pregnancy and childbirth are, in the main, normal life events. The medicalisation of childbirth, however, has impacted on the midwifery profession and midwifery models of care globally.18 19 In China, the overall annual rate of caesarean deliveries reached 36.7% in 2018,20 still far beyond the WHO’s recommended level between 10% and 15%.21 Currently, midwives and midwifery services in China are not effectively integrated into the national health system. Pregnant women usually receive fragmented care and lack individualised continuity of care from midwives throughout perinatal period. During each antenatal visit, women can only spend a few minutes with their obstetrician due to the large number of women requiring assessment and time constraints.22 The full scope of care provided by Chinese midwives is limited due to the obstetrician-led maternity care model. In past decades, the midwifery profession in China has been on the wane as China aspired to medical and technical modernisation.23 The belief that obstetricians were better trained and safer practitioners than midwives prevails.22 Almost all midwives employed in hospitals are confined to work in labour and delivery units, whereas antenatal care is provided by obstetricians and postnatal care provided by obstetric nurses.24 As such, the Chinese midwives are facing deskilling or loss of skills when their practice is restricted. One study conducted in western China demonstrated that 94.34% of the midwives had an initial educational level below a bachelor’s degree, and 69.75% had less than 10 years of working experience.25 In addition, no midwifery services are available at the community level in China.26

As one of the world’s most populous countries without the balancing effect of the full spectrum of midwifery care, China has now taken steps to address the over-medicalisation of childbirth and over-reliance on obstetric-led care through enhancement of midwifery services.27 The Chinese government has realised the pivotal role that midwives can play in a functioning health system and launched the 4-year bachelor degree midwifery programmes since 2014. Gao et al published a review of midwifery in Mainland China and stated that midwifery in China must continue to develop in parallel with international trends. The visibility of the midwife’s role is urgently needed.23 In recent years, a few pioneering trials on midwife-led services or interventions addressing specific task-shifting initiatives involving midwives have been conducted in China, which has proved the feasibility and effectiveness of midwife-led services on improving maternal and neonatal health outcomes.22 28–30 For instance, Cheung et al reported the first midwife-led normal birth unit in China and indicated the potential of the midwife-led model of care to reduce obstetric intervention and increase women’s satisfaction with care within a context of extraordinary high caesarean section rates.28 Hua et al conducted a cohort study in Shanghai and pointed out that continuity of midwife-led care model is the optimal service for low-risk women and is worthwhile for a general implementation across China.31 Nevertheless, most of these studies were either descriptive or interventional studies that focused on performing some kind of specific midwifery task. No consensus has been reached yet on the scope of practice and content of Chinese midwifery care in the context of global task shifting and China’s reintroduction of midwifery. Therefore, we consider it essential and urgent to define the appropriate scope of practice and task content of Chinese midwifery services, which may provide a foundational framework that policymakers, administrators and care providers, can apply to the design of tailored midwifery-led task shifting interventions in China and abroad.

Method

The aim of this study was to develop and validate a midwifery-led task list for Chinese midwives in the task-shifting context. First, we conducted a literature review to draft an initial task list of midwifery services for Chinese midwives. Then we performed a Delphi method to obtain consensus within a panel of experts and developed the final midwifery task list. Our study was carried out within nine various provincial regions of China (Shanghai, Beijing, Chongqing, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Hunan, Hubei, Shandong and Shanxi) between 1 July and 30 September 2019. The Delphi method is a research technique that draws on the ‘pooled intelligence’ of an expert panel to achieve consensus on a specific topic through the use of iterative rounds of questionnaires with controlled feedback.32–34 The Delphi method, through the provision of expert professional judgement, can be used to generate content-related validity evidence for midwifery service content.

Identifying potential task items in midwifery practice

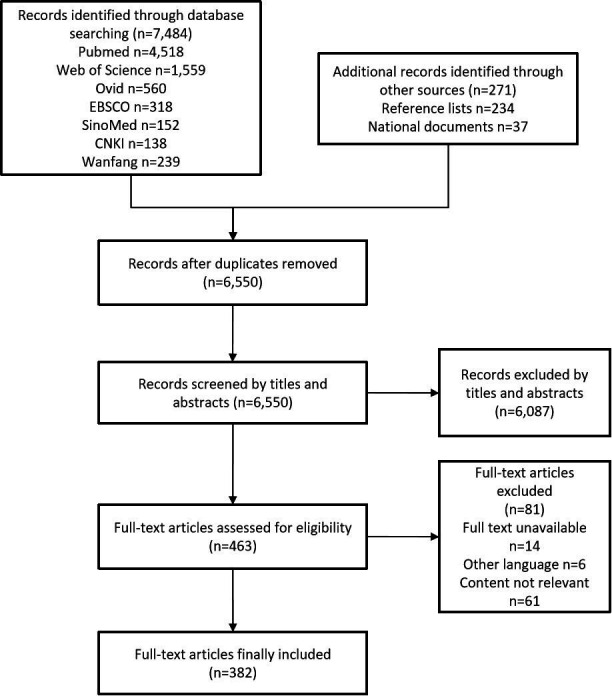

Potential midwifery service items were generated from literature and key documents published in English or Chinese. We searched databases (Web of Science, Ovid, EBSCO, SinoMed, CNKI and Wanfang), PubMed, reference lists as well as national documents from regulatory and professional bodies from inception until March 2019. We entered ‘midwifery’; ‘midwife’; ‘midwifery care’; ‘midwife-led care’; ‘midwifery service’; ‘midw*’; ‘maternity care’; ‘task shifting’; and ‘needs of pregnant/postnatal women’ as the main keywords in the search to retrieve the relevant literature. Two investigators performed the selection process independently using NoteExpress and data were tabulated using standardised forms. Discrepancies were resolved using consensus discussion.

Delphi expert panel recruitment

A Delphi group of Chinese experts was established based on the following criteria: (1) at least 8 years of working experience as a professional in maternal healthcare, obstetrics, nursing and midwifery; (2) with senior or chief professional titles; and (3) being familiar with midwifery practice. There is no consensus about the ideal sample size for Delphi studies. A sample of 15 has been suggested and larger panels have also been used.35 In this study, we aimed to include 20–40 experts for stable results.36 A purposive non-probability sampling was used to ensure that the appropriate experts were invited to participate. Considering the diverse cultural groups and imbalance of healthcare resources in China, a total of 28 prospective panellists from different regions were invited, covering areas from Eastern, Central and Western China (nine provinces: Shanghai, Beijing, Chongqing, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Hunan, Hubei, Shandong and Shanxi). They were sent email invitations explaining the study purpose and methodology. Membership of the Delphi panel was kept confidential. Informed consent was obtained from all participants at the start of the Delphi round.

Developing the Delphi questionnaire

Renfrew et al27 developed the framework for quality maternal and newborn care and defined the practice of midwifery across the continuum throughout prepregnancy, pregnancy, birth, postpartum and the early weeks of life. They mapped the scope of midwifery practice using competencies of midwives as defined by the ICM. Core characteristics of this framework include optimising normal biological, psychological, social and cultural processes of reproduction and early life; timely prevention and management of complications; consultation with and referral to other services; respect for women’s individual circumstances and views; and working in partnership with women to strengthen women’s own capabilities to care for themselves and their families.

In this study, we used Renfrew et al’s evidence-informed framework for quality maternal and newborn care to map the scope of practice of Chinese midwives. Guided by this theoretical framework and based on literature review and interviews with key informants (n=52), a draft of the midwifery task list was developed as a starting point for the consultation process. The drafted three-level task list of midwifery services was comprised of 4 domains of midwifery practice (first-level indicators), 16 types of task (second-level indicators) and 67 service items (third-level indicators). The four first-level indicators included prepregnancy care, antenatal care, intrapartum care and postnatal care. The 16 second-level indicators involved the practice categories of midwifery including education, information, health promotion; assessment, screening, care planning; promotion of normal processes, prevention of complications; first-line management of complications; and medical, obstetric, neonatal services. The 67 third-level indicators referred to the specific service items within the midwifery practice categories. A consensus meeting between investigators (CG, XW, ZZ, SL) decided which indicators should be included and how indicators were rephrased. Then a final Delphi questionnaire was developed by the research investigators.

Delphi procedure

Iterative rounds of Delphi surveys were used to complete the Delphi questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of four parts: (1) experts’ demographic characteristics, (2) instructions to fill in the questionnaire, (3) the three-level task list of midwifery services and (4) experts’ self-rated authority and their familiarity with items. A pilot study was conducted to pretest the questionnaire. The questionnaire was sent to six experts including two senior midwives, two clinical supervisors in midwifery, one obstetrician and one nurse manager. Through this pretest, we further revised the questionnaire. To maximise response rates, the surveys were designed and distributed to panellists using clear and easy-to-understand language. During each round, panellists were provided with a link to the survey and they were required to individually rated the importance, advancement and feasibility of each midwifery task item on a 5-Likert scale. ‘Importance’ represents the necessity and significance of task items tailored to women’s needs. ‘Advancement’ represents the progressiveness of midwifery task items conforming to the current best evidence. ‘Feasibility’ represents the technical viability and acceptability of midwifery task items if implemented in current China. Additionally, participant experts were asked to comment on the items and identify any additional items they felt should be included in the midwifery-led task list during the rounds of the Delphi process.

The first Delphi round was completed within 2 weeks. Data were collected, analysed and discussed by the research group to generate the second-round Delphi questionnaire. During the second round, the first-round results were attached to the questionnaire. Participants rerated the items using the same 5-Likert scale and were given the opportunity to provide new suggestions and remarks. Consensus among the expert panel was finally achieved after two-round Delphi process.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed using mean, proportion and frequency. The effective response rate of the Delphi questionnaire indicated experts’ positive coefficient. Experts’ degree authority (Cr) was determined by coefficient of determination (Ca) and degree of familiarity (Cs). A descriptive analysis of the scores on importance, advancement and feasibility, and a qualitative thematic content analysis of the comments were performed after each Delphi round. The mean rating and full mark rate of each item were calculated and illustrated the convergence level of expert opinions. Three authors (CG, XW and SL) reviewed experts’ ratings and qualitative comments. Items and their wording were modified according to comments from the expert panel. The coefficient of variation (CV) and Kendall harmony coefficient (W) were used to reflect the coordination level of expert opinions. A χ2 test was performed to test the significant degree of coordination among the expert opinions. Consensus indicated the condition of homogeneity or consistency of opinion of the expert panellists.33 37 It was predetermined that items rated ≥4.0, with a full mark rate ≥20% and CV ≤0.25 were considered ‘core’ midwifery-led tasks while items rated 3.5–4.0 would be considered potential midwifery tasks to be discussed by the research group to reach a consensus. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS, V.22.0 (IBM Corp).

Results

Literature review

The literature search resulted in a total of 7484 articles through databases and an additional 271 papers through other sources. We excluded duplicates (n=1205) and screened all the records by titles and abstracts (n=6550), leaving 463 potential papers to be assessed for eligibility. After a full-text reading of the 463 articles, 81 papers were removed. The remaining 382 articles were finally included and further reviewed by the authors (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of literature search and selection process. Our searches yielded 7755 records, and finally 382 full-text articles were included.

Consensus results of the Delphi process

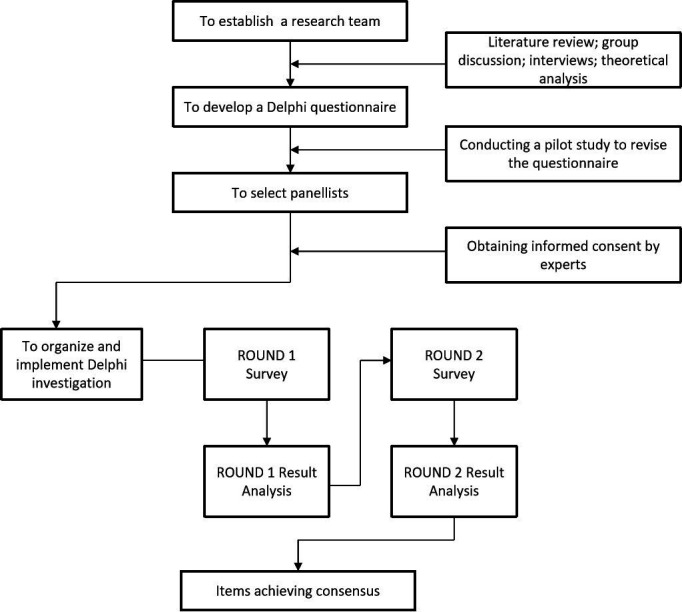

The flow of topics through each round of the Delphi process is outlined in figure 2. Twenty-seven of the 28 experts from nine provincial regions of China actively responded to the first Delphi round. In the second Delphi round, 27 experts completed the survey. The effective response rate was 96.4% (27/28) in the first round and 100% (27/27) in the second round, indicating a high positive coefficient of the experts. The Delphi panel member demographics are outlined in table 1. The average age of experts was (41.78±7.43) years and their experience in the relevant fields was (20.07±9.02) years. Among them, 74.1% (20/27) held senior-level professional titles and 63.0% (17/27) obtained the educational level of master or doctorate degree.

Figure 2.

Technical route of the Delphi process. A Delphi questionnaire was developed through literature review, group discussion, interviews and theoretical analysis. Then a two-iterative Delphi survey was conducted to reach consensus among the expert panel.

Table 1.

The Delphi panel member demographics (N=27)

| Item | N (%) |

| Age, year (mean±SD) | 41.78±7.43 |

| Working experience, year (mean±SD) | 20.07±9.02 |

| Professional title: | |

| Senior-level title | 20 (74.1) |

| Chief-level title | 7 (25.9) |

| Educational level: | |

| Doctorate degree | 10 (37.1) |

| Master degree | 7 (25.9) |

| Bachelor degree | 10 (37.0) |

| Organisation: | |

| University hospital | 20 (74.1) |

| Non-university hospital | 3 (11.1) |

| University college | 4 (14.8) |

| Midwifery supervision experience: | |

| Doctoral supervisor | 3 (11.1) |

| Master supervisor | 7 (25.9) |

| Bachelor supervisor | 12 (44.5) |

| Non-supervision experience | 5 (18.5) |

In this study, experts’ coefficient of determination of the experts (Ca) was 0.967, and the degree of familiarity (Cs) of the experts was 0.798. Thus the authority coefficient of experts (Cr= (Ca +Cs)/2) was 0.882, indicating the high reliability of this study.

Delphi round 1

In the first round, the mean scores of 1 first-level indicator, 3 second-level indicators and 13 third-level indicators were less than 4 points in feasibility. The majority of these indicators (1 first-level indicator, 3 second-level indicators and 10 third-level indicators) were related to prepregnancy care (see table 2), while 3 third-level indicators referred to screening and referral of women with mental health problems during pregnancy and after childbirth, and the postpartum follow-up for all women. Experts raised concerns about the feasibility of providing prepregnancy care by Chinese midwives in current China. As for screening and referral of women with mental health problems, and postpartum follow-up service, experts made suggestions that further training was needed to improve midwives’ knowledge and skills in performing these tasks.

Table 2.

Removed indicators related to prepregnancy care during Delphi round 1

| Level Ⅰ | Level Ⅱ | Level Ⅲ |

| Prepregnancy care | Education, information and health promotion | 1) To inform couples of existing risks and their adverse effects on pregnancy outcomes |

| 2) To provide information on health maintenance and health promotion | ||

| 3) To provide consultation and intstruction on eugenics | ||

| Assessment, screening and referral | 4) To assess preconceptional risk factors | |

| 5) To screen and identify risk factors that may lead to adverse pregnancy outcomes | ||

| 6) To perform and instruct women to complete preconceptional examinations | ||

| 7) To identify abnormal results of examinations and to make appropriate referrals | ||

| Intervention measures | 8) To help couples diminish or eliminate risk factors | |

| 9) To assist in the treatment and follow-up of related diseases or risk factors | ||

| 10) To help couples make plans for pregnancy |

Mean scores reflected that all other midwifery task items including first-level indicators (n=3), second-level indicators (n=13) and third-level indicators (n=54) were perceived important, advanced and feasible for midwives in current China (mean scores≥4). The Kendall harmony coefficient (W) in the first round of consultations was 0.196 (p<0.001). In this round, a total of 75 comments and suggestions were presented by 17 experts, resulting in a 63.0% (17/27) rate of comments. The experts pointed out that items related to medical/laboratory examinations and critical care management of women with complications were less appropriate for midwifery-led service task and further revisions were needed. Finally 48 comments and suggestions were adopted after discussion within the research group and confirmation with the relevant experts. Analysis of the themes reflected in the comments involved 2 second-level indicators and 25 third-level indicators. Based on the comments, the researchers decided to add a new third-level indicator in relation to breastfeeding (to identify women with previous or potential breastfeeding problems and to offer a referral if necessary) and delete 1 first-level indicator, 3 second-level indicators and 10 third-level indicators that were all related to prepregnancy care (see table 2). Then a second round Delphi questionnaire was formed and mainly consisted of 3 first-level indicators, 13 second-level indicators and 58 third-level indicators.

Delphi round 2

During the second round, all midwifery task indicator items from the first round were presented again to the panel. They were also informed about the changes to the task list and the deletion of indicators. In this round, a rather small number of comments and suggestions were presented by three experts (n=4). Finally, one comment was adopted after discussion within the research group and confirmation with the relevant experts. Content analysis of the comment resulted in a minor revision of the midwifery task list, by revising one third-level indicator ‘to conduct screening of newborn hearing, congenital and genetic diseases’ to ‘to provide consultation on screening of newborn hearing, congenital and genetic diseases’. The mean values of the importance, advancement, and feasibility of each midwifery task item in table 3 were greater than 3.5, and the full mark rates of the majority of the midwifery service items were greater than 20%, indicating that the convergence level of the expert opinions was relatively high. The full mark rates of only three midwifery service items in feasibility were less than 20% (18.52%, 11.11% and 14.81%, respectively). The three items were (1) Ⅱ−4: first-line management of pregnancy complications; (2) Ⅲ−50: to conduct screening and to make referrals for women with postpartum mental problems; and (3) Ⅲ−55: to provide postnatal follow-up. Considering their high values in importance and advancement (mean scores≥4), we still included the above three items in the final task list. The Kendall harmony coefficient (W) in the second round of consultations was 0.324 (p<0.001), and the CV of each item was less than 0.25. Consensus was obtained after two rounds. All assessment criteria turned out to be validated and included in the final midwifery service task list, which was comprised of 3 first-level indicators, 13 second-level indicators and 58 third-level indicators (see table 3). That is, a total of 58 midwifery service items were generated and categorised into 13 types of task and 3 domains of midwifery practice (see figure 3).

Table 3.

Final version of a midwifery-led task list and its scoring of assessment criteria

| Level Ⅰ | Level Ⅱ | Level Ⅲ | Importance (mean±SD) |

Advancement (mean±SD) | Feasibility (mean±SD) |

| Ⅰ−1 Antenatal care | 4.92±0.27 | 4.58±0.57 | 4.65±0.48 | ||

| Ⅱ−1 Education, information and health promotion | 4.88±0.32 | 4.54±0.57 | 4.62±0.56 | ||

| Ⅲ−1 To provide information on health maintenance and promotion | 4.88±0.32 | 4.62±0.56 | 4.77±0.42 | ||

| Ⅲ−2 To provide consultation and instruction on antenatal care | 4.89±0.32 | 4.66±0.55 | 4.69±0.46 | ||

| Ⅲ−3 To help couples make birth plan | 4.91±0.27 | 4.73±0.52 | 4.54±0.63 | ||

| Ⅲ−4 To provide education and consultation on reproductive healthcare during pregnancy | 4.73±0.44 | 4.54±0.57 | 4.46±0.63 | ||

| Ⅱ−2 Assessment, screening, referral and care planning | 4.76±0.42 | 4.41±0.57 | 4.44±0.57 | ||

| Ⅲ−5 To provide registration service for women during early pregnancy | 4.88±0.32 | 4.54±0.69 | 4.66±0.55 | ||

| Ⅲ−6 To collect health history and family history | 4.96±0.19 | 4.66±0.68 | 4.84±0.36 | ||

| Ⅲ−7 To assess and identify pregnancy risk factors and serious complications | 4.89±0.32 | 4.42±0.69 | 4.54±0.50 | ||

| Ⅲ−8 To make referrals and follow-ups for women with high risks or complications | 4.80±0.40 | 4.49±0.70 | 4.43±0.63 | ||

| Ⅲ−9 To perform checkups and to instruct women to complete examinations | 4.84±0.36 | 4.47±0.69 | 4.53±0.57 | ||

| Ⅲ−10 To help women make antenatal care plan | 4.89±0.32 | 4.54±0.69 | 4.61±0.68 | ||

| Ⅲ−11 To assess women’s health status | 4.88±0.32 | 4.54±0.69 | 4.38±0.56 | ||

| Ⅲ−12 To assess women’s body mass index and to develop a weight management plan | 4.96±0.19 | 4.62±0.68 | 4.50±0.69 | ||

| Ⅲ−13 To assess fetal condition including fetal growth and development | 4.93±0.27 | 4.73±0.65 | 4.53±0.63 | ||

| Ⅲ−14 To perform screening and referral for women with mental health problems | 4.88±0.32 | 4.54±0.64 | 3.85±0.86 | ||

| Ⅲ−15 To identify women with previous or potential breastfeeding problems and to offer a referral if necessary | 4.66±0.47 | 4.31±0.68 | 4.05±0.89 | ||

| Ⅱ−3 Promotion of normal pregnancy and prevention of complications | 4.92±0.27 | 4.54±0.57 | 4.49±0.57 | ||

| Ⅲ−16 To identify symptoms of genital tract infections and to provide precautions | 4.50±0.64 | 4.39±0.56 | 4.20±0.68 | ||

| Ⅲ−17 To provide interventions for women with common physical symptoms | 4.77±0.50 | 4.54±0.64 | 4.33±0.78 | ||

| Ⅲ−18 To provide preventative measures for women with preeclampsia or eclampsia | 4.69±0.54 | 4.51±0.57 | 3.93±0.87 | ||

| Ⅲ−19 To perform appropriate midwifery skills during pregnancy | 4.73±0.44 | 4.36±0.62 | 4.28±0.66 | ||

| Ⅱ−4 First-line management of pregnancy complications | 4.77±0.50 | 4.31±0.67 | 3.85±0.77 | ||

| Ⅲ−20 To cooperate with medical staff in obstetric emergencies | 4.92±0.27 | 4.66±0.55 | 4.70±0.54 | ||

| Ⅲ−21 To cooperate with medical staff for treatment of pregnancy complications | 4.92±0.27 | 4.63±0.56 | 4.66±0.48 | ||

| Ⅲ−22 To cooperate with medical staff for treatment of infectious diseases during pregnancy | 4.93±0.27 | 4.63±0.49 | 4.54±0.63 | ||

| Ⅲ−23 To provide basic emergent obstetric care | 4.93±0.27 | 4.57±0.57 | 4.53±0.57 | ||

| Ⅰ−2 Intrapartum care | 4.96±0.19 | 4.69±0.54 | 4.96±0.19 | ||

| Ⅱ−5 Education, information and health promotion | 4.89±0.42 | 4.74±0.52 | 4.84±0.36 | ||

| Ⅲ−24 To encourage women to choose trial of vaginal birth, and to provide information on promoting normal birth | 5.00±0.00 | 4.69±0.54 | 4.81±0.39 | ||

| Ⅲ−25 To inform women of labour progress and maternal/fetal conditions | 4.96±0.19 | 4.69±0.61 | 4.66±0.55 | ||

| Ⅱ−6 Assessment, identification and care plan | 4.92±0.27 | 4.70±0.54 | 4.73±0.44 | ||

| Ⅲ−26 To make admission assessment on maternal/fetal conditions and pregnancy progress | 5.00±0.00 | 4.73±0.52 | 4.92±0.27 | ||

| Ⅲ−27 To observe labour progress and use the partogram | 5.00±0.00 | 4.77±0.58 | 4.96±0.19 | ||

| Ⅲ−28 To identify abnormal labour, to make timely referrals, and to cooperate with obstetricians | 5.00±0.00 | 4.85±0.36 | 4.77±0.42 | ||

| Ⅲ−29 To provide continuity of care and labour support | 5.00±0.00 | 4.77±0.50 | 4.40±0.63 | ||

| Ⅲ−30 To perform restrictive use of episiotomy | 5.00±0.02 | 4.81±0.39 | 4.58±0.49 | ||

| Ⅱ−7 Promotion of normal labour and prevention of complications | 4.96±0.19 | 4.81±0.48 | 4.88±0.32 | ||

| Ⅲ−31 To manage labour pain | 4.93±0.27 | 4.73±0.44 | 4.46±0.63 | ||

| Ⅲ−32 To manage hydration and oral intake in labour | 4.89±0.32 | 4.76±0.51 | 4.39±0.63 | ||

| Ⅲ−33 To take measures to promote labour progress | 4.96±0.19 | 4.62±0.49 | 4.51±0.50 | ||

| Ⅲ−34 To perform appropriate midwifery skills in labour | 5.00±0.00 | 4.66±0.62 | 4.74±0.44 | ||

| Ⅲ−35 To use uterotonic agents during the third stage of labour to prevent postpartum haemorrhage | 5.00±0.00 | 4.73±0.52 | 4.89±0.32 | ||

| Ⅲ−36 To provide early essential newborn care | 4.96±0.19 | 4.66±0.62 | 4.54±0.50 | ||

| Ⅲ−37 To observe maternal and neonatal conditions 2 hours post partum | 5.00±0.00 | 4.70±0.61 | 4.92±0.27 | ||

| Ⅱ−8 First-line management of childbirth complications | 4.85±0.46 | 4.66±0.62 | 4.65±0.55 | ||

| Ⅲ−38 To identify and initiate emergency interventions for post partum haemorrhage | 5.00±0.00 | 4.77±0.50 | 4.93±0.27 | ||

| Ⅲ−39 To perform initial neonatal resuscitation or further resuscitation assistance | 5.00±0.00 | 4.77±0.50 | 4.96±0.19 | ||

| Ⅱ−9 Obstetric critical and emergency care and collaboration | 4.74±0.59 | 4.69±0.54 | 4.35±0.68 | ||

| Ⅲ−40 To make preparations for emergency caesarean sections | 5.00±0.00 | 4.81±0.48 | 4.80±0.39 | ||

| Ⅲ−41 To perform safe blood transfusion | 5.00±0.02 | 4.81±0.39 | 4.88±0.32 | ||

| Ⅰ−3 Postnatal care | 4.73±0.52 | 4.50±0.50 | 4.15±0.72 | ||

| Ⅱ−10 Education, information and health promotion | 4.84±0.36 | 4.58±0.57 | 4.42±0.63 | ||

| Ⅲ−42 To provide health promotion information on breastfeeding | 4.96±0.19 | 4.81±0.48 | 4.58±0.49 | ||

| Ⅲ−43 To inform women of the postpartum rehabilitation process and common postnatal health problems | 4.89±0.32 | 4.70±0.54 | 4.62±0.49 | ||

| Ⅲ−44 To provide consultation and instruction on nutrition, hygiene, activities, mental care, postnatal contraceptive, and reproductive healthcare | 4.93±0.27 | 4.58±0.63 | 4.20±0.74 | ||

| Ⅱ−11 Overall check-up and assessment of neonatal condition | 4.73±0.44 | 4.43±0.57 | 4.27±0.65 | ||

| Ⅲ−45 To perform overall check-up and assessment of neonatal health condition | 4.92±0.27 | 4.69±0.54 | 4.69±0.46 | ||

| Ⅲ−46 To assess uterine contraction, fundus height and lochia to early identify postpartum haemorrhage | 4.96±0.19 | 4.73±0.52 | 4.85±0.36 | ||

| Ⅲ−47 To assess postpartum recovery state | 5.00±0.00 | 4.69±0.54 | 4.69±0.46 | ||

| Ⅲ−48 To assess breastfeeding condition | 4.96±0.19 | 4.74±0.52 | 4.53±0.57 | ||

| Ⅲ−49 To identify abnormal postpartum women | 4.96±0.19 | 4.66±0.48 | 4.50±0.57 | ||

| Ⅲ−50 To conduct screening and to make referrals for women with postpartum mental problems | 4.77±0.42 | 4.50±0.69 | 3.70±0.67 | ||

| Ⅲ−51 To identify abnormal neonates and to make referrals | 4.73±0.44 | 4.50±0.64 | 4.23±0.75 | ||

| Ⅲ−52 To provide consultation on screening of newborn hearing, congenital and genetic diseases | 4.68±0.54 | 4.54±0.57 | 4.16±0.82 | ||

| Ⅱ−12 Promotion of normality and prevention of complications | 4.77±0.42 | 4.61±0.56 | 4.37±0.63 | ||

| Ⅲ−53 To provide information on neonatal vaccinations | 4.73±0.52 | 4.58±0.57 | 4.61±0.62 | ||

| Ⅲ−54 To provide postpartum mental healthcare | 4.89±0.32 | 4.61±0.63 | 4.10±0.79 | ||

| Ⅲ−55 To provide postnatal follow-up | 4.72±0.45 | 4.42±0.69 | 3.73±0.71 | ||

| Ⅲ−56 To provide postnatal care and neonatal care | 4.87±0.32 | 4.47±0.63 | 4.49±0.50 | ||

| Ⅱ−13 First-line management of postnatal complications | 4.59±0.80 | 4.54±0.63 | 4.00±0.78 | ||

| Ⅲ−57 To cooperate with medical staff for treatment of abnormal women | 4.96±0.19 | 4.62±0.56 | 4.66±0.62 | ||

| Ⅲ−58 To cooperate with medical staff for treatment of abnormal neonates | 4.88±0.32 | 4.58±0.63 | 4.57±0.63 | ||

Figure 3.

Diagram of the midwifery-led task list. The final three-level midwifery service task list was comprised of 3 domains of midwifery practice, 13 types of task and 58 midwifery service items throughout antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal periods.

Discussion

This multicentre Delphi study, which included a panel of experts nationwide with broad expertise in maternity care and management, sought to determine the key task items of midwifery services for Chinese midwives. We developed a midwifery-led task list for Chinese midwives covering antenatal, intrapartum and postpartum periods to fill the gap in literature of this field. Finally a total of 58 midwifery task items were identified and categorised into 13 types of task and 3 domains of midwifery practice, which are well suited for midwifery practice in current China.

In this study, we used Renfrew et al’s evidence-informed framework for maternal and newborn care to map the scope of practice of Chinese midwives throughout prepregnancy, pregnancy, birth and post partum.27 Thus these four periods constituted the phase dimension of four first-level indicators of the Chinese midwifery task list draft. Beyond that, we selected the first four midwifery practice categories from Renfrew et al’s framework as the task type dimension (second-level indicators) of our task list draft, including (1) education, information and health promotion; (2) assessment, screening and care planning; (3) promotion of normal processes and prevention of complications; and (4) first-line management of complications. These components coincided with midwives’ scope of practice defined by the ICM.15 And on this basis the service items containing 67 third-level indicators in our study were drafted, and each item fell within the first four midwifery practice categories of Renfrew et al’s evidence-informed framework.27

During the Delphi rounds, 1 first-level indicator, 3 second-level indicators and 10 third-level indicators, which were all related to prepregnancy care, were eventually removed from the task list (see table 2), due to its infeasibility when provided by midwives at the current stage. This amendment reflected the high consistency of the experts’ opinion and consisted with the ICM’s statement that the midwife works in partnership with women during pregnancy, labour and the postpartum period.38 Also, our findings are consistent with a previous study by Devane et al who sought to identify and prioritise midwifery care process metrics and indicators in Ireland. And these metrics span the pregnancy, birth and postpartum periods as well.39

In this study, the draft contents of midwifery service task list were revised with the expert argumentation after two rounds of Delphi survey. And consensus was reached to generate a final task list for Chinese midwives. Compared with midwives’ current role and job task in China,22 40 the task list in this study focused on expanding midwives’ scope of practice throughout the entire period of pregnancy, childbirth, and post partum. In this finalised list, the midwifery tasks related to health education, consultation and health promotion covered the entire three phase dimensions of midwifery services. It was also stated by the ICM that the midwife has an important task in health counselling and education, which involves antenatal education and preparation for parenthood and may extend to women’s health, sexual or reproductive health and child care.15 Besides, in this study, midwifery task items with regard to assessment, screening, referral and care planning were formed within the three phase dimensions. During the Delphi round, a new third-level indicator named as ‘to identify women with previous or potential breastfeeding problems and to offer a referral if necessary’ was added to the task list according to experts’ comments (see table 3, Ⅲ−15). Swerts et al pointed out that midwives value breastfeeding support as a significant part of their role.41 Wallenborn et al’s study findings also highlighted the importance of prenatal midwifery care providers on breastfeeding duration.42 In addition, midwives were proved to be most effective when integrated into the health system in the context of effective referral mechanisms.27 43 44 Therefore, it is essential for midwives to provide health promotion information on maternal and newborn care (eg, breastfeeding), to identify abnormalities, and to make appropriate referrals.

Concurrently, in our newly developed midwifery service task list, promotion of normal processes and prevention of complications became midwives’ essential tasks during pregnancy, childbirth and postnatal periods. This is because pregnancy and childbirth are, in the main, normal physiological events.38 The promotion of normal childbirth and preventative measures are also included in the ICM’s midwifery scope of practice.15 Aune et al’s study unfolded that the midwives had a great desire to promote normal births with a minimum of interventions.45 In this regard, midwives should have the competence to support the physiology of pregnancy and childbirth, to provide women-centred continuity of care, and to confirm normalcy throughout perinatal periods.46

However, due to the uncertainty of pregnancy and childbirth, women with uncomplicated pregnancies might subsequently develop high risks or encounter with obstetric emergencies.24 47 As such, in our study, experts reached a consensus to include first-line management of complications, and obstetric critical/emergency care and collaboration as additional important midwifery task types, which consisted of 10 specific task items (third-level indicators) in the list (see table 3, Ⅲ−20~23, Ⅲ−38~41, Ⅲ−57~58). The midwife is recognised as a responsible professional who gives the woman necessary support and care, including detection of complications in mother and child, the accessing of medical care or other appropriate assistance and the carrying out of emergency measures.15 This means midwives work in collaboration as part of interdisciplinary teams providing integrated care. And other studies have also shown that the midwife has an important contribution to providing effective and quality midwifery care for women and infants with complications.27 45 These types of task were perceived by midwives as not constituting ‘normal’ midwifery work, but still they felt competent in the expanded role task.45 48–50 Accordingly, with regard to management of complications, incorporating collaborative teamwork with other colleagues in medical, obstetric, neonatal services should be one of the midwife’s competencies as well.

In this study, the Delphi method was used as it was considered the most ideal methods for reaching group consensus on a specific topic. On basis of literature review and through rigorous task item generation and the provision of expert professional judgement, the Delphi method provides evidence of content validity of the proposed midwifery-led task list and helps to enhance the generalisability of the findings. As 20–40 persons were considered to be most appropriate for a Delphi survey,36 we recruited a total of 28 experts nationwide who were interested in our study and thus could guarantee the completion of the questionnaire at the given time. During each Delphi round, we collected experts’ comments, provided timely feedback to the experts, and sought advice from them again. In this study, two rounds of Delphi survey were conducted to formulate a comprehensive range of midwifery tasks suitable for Chinese midwives. We found that the effective response rate during the two rounds was 96.4% and 100%, respectively, which reflected the experts’ high concern to this study and guaranteed the reliability of our findings.

In the global task-shifting context and during the transitional period for the rebirth of Chinese midwifery, our study focused on developing an appropriate midwifery-led task list that was tailored to guide China’s midwifery practice. The implementation of China’s new birth policies has profound implications for the role and practice of midwives.23 Beyond that, as China moves towards a thriving goal—namely, towards ensuring health and well-being,51 the contribution of midwives has been increasingly recognised by the Chinese government. At the present stage, the government has realised that a more midwife-led model of maternal care is urgently needed, and placed great emphasis on further clarifying the definition and scope of practice of midwives to improve the capacity of midwifery services.52 Therefore, we believe that our newly developed midwifery task list could be adopted by relevant government departments and help policymakers develop effective strategies to enhance the role of midwifery to provide comprehensive healthcare for women and children. Nonetheless, the main existing challenges towards advocating this task list may include shortage of midwifery workforce, degradation of midwives’ competency, and lack of related regulations and formal midwifery registration system, which also poses a great need to strengthen midwifery in China.51 53

Limitations

First, due to the nature of Delphi method combining literature review with the opinions of a panel of experts, the findings of our study might be subjective to a certain extent. Second, this midwifery service task list is still at a theoretical level and no practical experiences have been gained yet. It has not fully illustrated how to functionally integrate these midwifery task items into current health system to optimise midwives’ roles. Hence, the findings could not reflect the effectiveness and efficacy of midwifery practices and maternal and neonatal health outcomes. Third, China is a large country encompassing different cultural groups and traditions, but the respondents of our study were only from various urban cities of China, meaning that their views might not be representative of those from rural areas. Fourth, the number of experts was limited and we just recruited a panel of Chinese experts to formulate the task list that could be only applicable to midwifery practice in current China. Therefore, this might cause a limitation of its generalisability and applicability to other countries and regions. However, this was the first multicentre Delphi study to develop and validate a midwifery-led task list that was tailored to midwifery practice in the current critical transition period of Chinese midwifery. The new task list expands Chinese midwives’ current scope of practice and will provide a foundational framework for the development of specific midwifery-led task shifting interventions in maternity settings.

Conclusion

In this study, the new midwifery task list provides a foundation for expanding midwifery scope of practice in China. It implies that further research and development of midwifery-led task shifting interventions are needed. The list also enables intervention programmes to customise midwifery-led tasks to serve women’s needs and local context. Concurrently, it is important to note that the newly developed task list is only at a theoretical level and therefore needs to be further tested in maternity settings in China. Moving forward, it will be important and essential to prioritise these task items and involve experts and stakeholders from across China when developing a national midwifery-led task shifting intervention throughout perinatal periods to ensure transferability across different settings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors would like to thank all experts who participated in our study and pay tribute to Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital of Fudan University for supporting this study.

Footnotes

YD and XQ contributed equally.

Contributors: XQ, YD and CG contributed to the study concept and literature review. CG wrote the first draft of the manuscript. XW, ZZ and SL conducted the Delphi survey. XQ, CG and HL participated in the interpretation of the results. XQ, YD and HL contributed to revising the manuscript and approved the final version. XQ and YD contributed equally to this article.

Funding: This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.71874030).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

No additional data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital of Fudan University (OGHEC201951).

References

- 1.Pallangyo ES, Ndirangu E, Mwasha L, et al. Task shifting to attain sustainable development goals and universal health coverage: what are the consequences to the nursing and midwifery profession? Int J Nurs Stud 2020;102:103453. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosa WE, Kurth AE, Sullivan-Marx E, et al. Nursing and midwifery advocacy to lead the United nations sustainable development agenda. Nurs Outlook 2019;67:628–41. 10.1016/j.outlook.2019.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . WHO recommendations: optimizing health worker roles to improve access to key maternal and newborn health interventions through task shifting. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2012Available:. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK148518/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK148518.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization . Task shifting: rational redistribution of tasks among health workforce teams: global recommendations and guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2007Available:. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43821/1/9789241596312_eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deller B, Tripathi V, Stender S, et al. Task shifting in maternal and newborn health care: key components from policy to implementation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2015;130 Suppl 2:S25–31. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.International Labour Office . International standard classification of occupations ISCO-08: volume 1: structure, group definitions and correspondence tables. Geneva, 2012. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/-dgreports/-dcomm/-publ/documents/publication/wcms_172572.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sandall J. Every woman needs a midwife, and some women need a doctor too. Birth 2012;39:323–6. 10.1111/birt.12010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colvin CJ, de Heer J, Winterton L, et al. A systematic review of qualitative evidence on barriers and facilitators to the implementation of task-shifting in midwifery services. Midwifery 2013;29:1211–21. 10.1016/j.midw.2013.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perriman N, Davis DL, Ferguson S. What women value in the midwifery continuity of care model: a systematic review with meta-synthesis. Midwifery 2018;62:220–9. 10.1016/j.midw.2018.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandall J, Soltani H, Gates S, et al. Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;4:CD004667. 10.1002/14651858.CD004667.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization . A global call to action: strengthen midwifery to save lives and promote health of women and newborns. Washington DC: United Nations Population Fund; 2010. https://unfpa.org/sites/default/files/jahia-news/documents/news/2010/midwifery_jointstatement.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dawson AJ, Buchan J, Duffield C, et al. Task shifting and sharing in maternal and reproductive health in low-income countries: a narrative synthesis of current evidence. Health Policy Plan 2014;29:396–408. 10.1093/heapol/czt026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.ten Hoope-Bender P, de Bernis L, Campbell J, et al. Improvement of maternal and newborn health through midwifery. Lancet 2014;384:1226–35. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60930-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Long Q, Allanson ER, Pontre J, et al. Onsite midwife-led birth units (OMBUs) for care around the time of childbirth: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health 2016;1:e000096. 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.International Confederation of Midwives . Core document: international definition of the midwife, 2017. Available: http://www.internationalmidwives.org

- 16.International Confederation of Midwives . Essential competencies for midwifery practice: updated 2019, 2019. Available: https://internationalmidwives.org/assets/files/general-files/2019/10/icm-competencies-en-print-october-2019_final_18-oct-5db05248843e8.pdf

- 17.CY G, Wang XJ, Li L L, et al. Midwives’ views and experiences of providing midwifery care in the task shifting context: a meta-ethnography approach. J Glob Health 2020;4:96–106. 10.1016/j.glohj.2020.08.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gu CY, Wang XJ, Zhang ZJ, et al. Pregnant women's clinical characteristics, intrapartum interventions, and duration of labour in urban China: a multi-center cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020;20:386. 10.1186/s12884-020-03072-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.International Confederation of Midwives . Position statement: midwifery led care, the first choice for all women, 2017. Available: http://www.internationalmidwives.org

- 20.National Health Commission . China maternal and child health development report (2019). China, 2019. Available: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/fys/s7901/201905/bbd8e2134a7e47958c5c9ef032e1dfa2.shtml

- 21.Moore B. Appropriate technology for birth. The Lancet 1985;326:787–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(85)90673-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gu CY, Wu XD, Ding Y, et al. The effectiveness of a Chinese midwives' antenatal clinic service on childbirth outcomes for primipare: a randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 2013;50:1689–97. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao LL, Lu H, Leap N, et al. A review of midwifery in mainland China: contemporary developments within historical, economic and sociopolitical contexts. Women Birth 2019;32:e279–83. 10.1016/j.wombi.2018.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gu CY, Zhu XL, Ding Y, et al. A qualitative study of nulliparous women's decision making on mode of delivery under China's two-child policy. Midwifery 2018;62:6–13. 10.1016/j.midw.2018.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou N, Lu H, Zhao H, et al. Midwifery service and midwifery human resource demand in Western China: a cross-sectional study. The Lancet 2019;394:S34. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32370-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yao J, Zhu X, Lu H. Assessing the midwifery workforce demand: utilising birthrate plus in China. Midwifery 2016;42:61–6. 10.1016/j.midw.2016.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Renfrew MJ, McFadden A, Bastos MH, et al. Midwifery and quality care: findings from a new evidence-informed framework for maternal and newborn care. Lancet 2014;384:1129–45. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60789-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheung NF, Mander R, Wang X, et al. Clinical outcomes of the first midwife-led normal birth unit in China: a retrospective cohort study. Midwifery 2011;27:582–7. 10.1016/j.midw.2010.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheung NF, Mander R, Wang X, et al. Views of Chinese women and health professionals about midwife-led care in China. Midwifery 2011;27:842–7. 10.1016/j.midw.2010.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang H, Tang S, Li J, et al. Task shifting of traditional birth attendants in rural China: a qualitative study of the implementation of institution-based delivery policy. The Lancet 2015;386:S41. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00622-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hua J, Zhu L, Du L, et al. Effects of midwife-led maternity services on postpartum wellbeing and clinical outcomes in primiparous women under China's one-child policy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018;18:329. 10.1186/s12884-018-1969-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Villiers MR, de Villiers PJT, Kent AP. The Delphi technique in health sciences education research. Med Teach 2005;27:639–43. 10.1080/13611260500069947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Graham B, Regehr G, Wright JG. Delphi as a method to establish consensus for diagnostic criteria. J Clin Epidemiol 2003;56:1150–6. 10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00211-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keeney S, Hasson F, McKenna HP. A critical review of the Delphi technique as a research methodology for nursing. Int J Nurs Stud 2001;38:195–200. 10.1016/S0020-7489(00)00044-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McMillan SS, King M, Tully MP. How to use the nominal group and Delphi techniques. Int J Clin Pharm 2016;38:655–62. 10.1007/s11096-016-0257-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akins RB, Tolson H, Cole BR. Stability of response characteristics of a Delphi panel: application of bootstrap data expansion. BMC Med Res Methodol 2005;5:37. 10.1186/1471-2288-5-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, et al. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:401–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.International Confederation of Midwives . Position statement: appropriate maternity services for normal pregnancy, childbirth and the postnatal period, 2017. Available: http://www.internationalmidwives.org

- 39.Devane D, Barrett N, Gallen A, et al. Identifying and prioritising midwifery care process metrics and indicators: a Delphi survey and stakeholder consensus process. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019;19:198. 10.1186/s12884-019-2346-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Z, Gu CY, Zhu XL, et al. Factors associated with Chinese nulliparous women's choices of mode of delivery: a longitudinal study. Midwifery 2018;62:42–8. 10.1016/j.midw.2018.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swerts M, Westhof E, Bogaerts A, et al. Supporting breast-feeding women from the perspective of the midwife: a systematic review of the literature. Midwifery 2016;37:32–40. 10.1016/j.midw.2016.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wallenborn JT, Lu J, Perera RA, et al. The impact of the professional qualifications of the prenatal care provider on breastfeeding duration. Breastfeed Med 2018;13:106–11. 10.1089/bfm.2017.0133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Lerberghe W, Matthews Z, Achadi E, et al. Country experience with strengthening of health systems and deployment of midwives in countries with high maternal mortality. Lancet 2014;384:1215–25. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60919-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Homer CSE, Friberg IK, Dias MAB, et al. The projected effect of scaling up midwifery. Lancet 2014;384:1146–57. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60790-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aune I, Holsether OV, Kristensen AMT. Midwifery care based on a precautionary approach: promoting normal births in maternity wards: the thoughts and experiences of midwives. Sex Reprod Healthc 2018;16:132–7. 10.1016/j.srhc.2018.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patterson J, Mącznik AK, Miller S, et al. Becoming a midwife: a survey study of midwifery alumni. Women Birth 2019;32:e399–408. 10.1016/j.wombi.2018.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Munro S, Janssen P, Corbett K, et al. Seeking control in the midst of uncertainty: women's experiences of choosing mode of birth after caesarean. Women Birth 2017;30:129–36. 10.1016/j.wombi.2016.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eadie IJ, Sheridan NF. Midwives' experiences of working in an obstetric high dependency unit: a qualitative study. Midwifery 2017;47:1–7. 10.1016/j.midw.2017.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singleton G, Furber C. The experiences of midwives when caring for obese women in labour, a qualitative study. Midwifery 2014;30:103–11. 10.1016/j.midw.2013.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lim M, Riggs E, Shankumar R. Midwives' and women’s views on accessing dental care during pregnancy: an Australian qualitative study. Aust Dent J 2018. 10.1111/adj.12611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qiao J, Wang Y, Li X, et al. A Lancet Commission on 70 years of women’s reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health in China. The Lancet 2021;314. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32708-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Reply to proposal No. 0356 (healthcare and sports No. 030) of the second session of the 13th National Committee of the CPPCC. Available http://www.nhc.gov.cn/wjw/tia/202007/2b61c42b5f844a66850d84f3974702fe.shtml [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhu X, Yao J, Lu J, et al. Midwifery policy in contemporary and modern China: from the past to the future. Midwifery 2018;66:97–102. 10.1016/j.midw.2018.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No additional data are available.