Abstract

Vinyl fluorides play an important role in drug development as bioisosteres for peptide bonds and are found in a range of bioactive molecules. The discovery of safe, general and practical procedures to prepare vinyl fluorides from readily available precursors remains a synthetic challenge. The metal-free hydrofluorination of alkynes constitutes an attractive though elusive strategy for their preparation. Here we introduce an inexpensive and easily-handled reagent that enabled the development of simple and scalable protocols for the regioselective hydrofluorination of alkynes to access both the E and Z isomers of vinyl fluorides. These conditions were suitable for a diverse collection of alkynes, including several highly-functionalized pharmaceutical derivatives. Computational and experimental mechanistic studies support C–F bond formation through vinyl cation intermediates, with the (E)- and (Z)-hydrofluorination products forming under kinetic and thermodynamic control, respectively.

Keywords: vinyl fluoride, fluorinating reagent, pharmaceutical derivatization, vinyl cation, DFT study

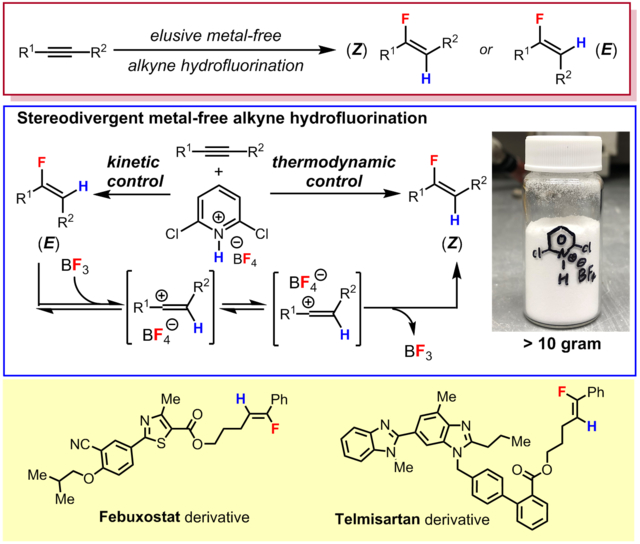

Graphical Abstract

An inexpensive new reagent enables the development of metal-free protocols for stereodivergent hydrofluorination. Computations and mechanistic data support the intermediacy of vinyl cations, which are trapped to deliver (E)- and (Z)-vinyl fluorides under kinetic and thermodynamic control, respectively.

Introduction

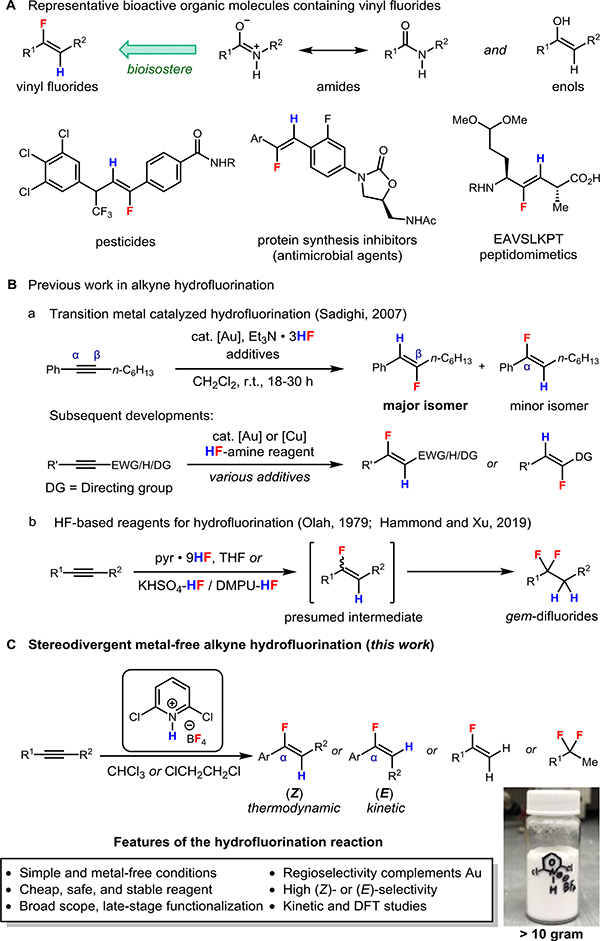

The incorporation of fluorine into organic compounds plays a significant role in the pharmaceutical and agrochemical sciences, due to the element’s distinctive capability for modulating the physical and chemical properties of a biologically active scaffold, including its solubility, metabolic stability, potency, and bioavailability.[1] Among organofluorine derivatives, vinyl fluorides constitute a privileged substructure and an important target of chemical synthesis. In particular, they can serve as metabolically and chemically stable bioisosteres of amides and enols by mimicking the charge distribution and dipole moments of these functional groups.[2] In other contexts, they can also function as irreversible enzyme inhibitors by acting as Michael acceptors (Scheme 1A).[2c]

Scheme 1.

Strategies for the synthesis of vinyl fluorides

Established synthetic methods to access vinyl fluorides primarily employ olefination or elimination reactions that require multistep transformations and the preparation or commercial availability of prefunctionalized fluorinated precursors.[3] Among methods that directly establish the carbon–fluorine bond, the Pd-catalyzed synthesis of vinyl fluorides from the corresponding triflates employs an alkali metal fluoride as a readily available fluorine source.[4] In contrast, the metal-catalyzed and noncatalytic electrophilic fluorination of various vinylmetal species constitutes a flexible and versatile approach that has given rise to a multitude of synthetic protocols.[5] Finally, the dehydrative fluorination of ketones using difluorosulfur(IV) reagents is another approach that has appeared in the patent literature.[6]

As an alternative to the aforementioned approaches, the hydrofluorination of alkynes represents a particularly general and atom-economical synthesis of vinyl fluorides, especially considering the broad range of alkyne substrates that are easily accessed from inexpensive, commercially available building blocks. Several metal-catalyzed systems for the hydrofluorination of alkynes have been developed in recent years.[7–15] Following the initial disclosure of a Au-catalyzed process by Sadighi and co-workers,[7] a number of coinage metal complexes have been employed as catalysts for the hydrofluorination of alkynes using Lewis base adducts of hydrogen fluoride as the fluorinating reagents (Scheme 1B).[7–13] In the Au-catalyzed systems, (Z)-vinyl fluorides are formed with high stereoselectivity, and for aryl alkyl alkynes, the major regioisomer formed is the one in which the fluorine is delivered to the carbon adjacent to the alkyl group (β to the aryl group, Scheme 1B, a). Since the initial report of Au-catalyzed alkyne hydrofluorination in 2007, the scope of this process has seen considerable expansion and now includes alkynes bearing electron-withdrawing groups or directing groups, as well as terminal alkynes. Nevertheless, the control of the regioselectivity and E/Z-selectivity remains an outstanding issue in a number of cases (Scheme 1B, a).[3b]

While the development of methods for the direct synthesis of vinyl fluorides via C–F bond formation has provided more opportunities to introduce the functional group and expanded the range of synthetically accessible vinyl fluorides, currently available methods suffer from one or more significant drawbacks, including the expense and poor atom economy of electrophilic fluorinating reagents ultimately derived from F2 gas,[3a] the corrosivity and toxicity hazards associated with HF-based reagents, and the challenges of accessing large quantities of well-engineered ligands and transition metal catalysts. These drawbacks limit the scalability and applicability of current protocols. Consequently, the development of operationally simple protocols and practical reagents for accessing vinyl fluorides with control of regio- and stereochemistry remains an ongoing challenge.

Considering their low cost, high fluoride content, as well as excellent safety, stability, and handling profiles, tetrafluoroborate (BF4−) salts are particularly attractive sources of nucleophilic fluorine.[16] However, aside from the well-developed Balz-Schiemann process, they have seldom been employed in the formation of C(sp2)−F bonds due to the weak nucleophilicity of this anion, and the handful of examples in which they are employed as fluorine sources in vinyl fluoride synthesis generally entail the use of exotic functional groups or strongly oxidizing conditions.[17] Given the canonical status of the alkyne hydrochlorination, –bromination, and –iodination reactions[18a] and mechanistic studies supporting a concerted AdE3 mechanism or an AdE2 mechanism featuring a vinyl cation intermediate for these processes,[18b,18c] we hypothesized that a metal-free hydrofluorination could result from a mild and selective protonation of the alkyne, followed by trapping of the resultant Brønsted acid–alkyne complex or vinyl cation intermediate by BF4−. Therefore, we posited that a suitable fluoroboric acid (HBF4) equivalent could serve as a general and practical hydrofluorinating reagent for alkynes.

By employing pyridine•9HF, the hydrofluorination of alkynes using a base-modulated source of hydrogen fluoride was already the subject of pioneering investigations by Olah and coworkers in the 1970s.[19] More recent studies by Hammond, Xu, and co-workers lead to the development of several ‘designer’ base-complexed sources of hydrogen fluoride.[20] However, both reports indicate that, in general, even with careful control of the reaction temperature (0 to 50 °C), HF-amine reagents deliver the gem-difluoride bis(hydrofluorination) product (Scheme 1B, b), without allowing for the isolation of the presumed vinyl fluoride intermediate except in special cases where the alkyne bears a donor heteroatom substituent (e.g., ynamide[21] or alkynyl sulfide substrates[22]).

We reasoned that an acidic reagent based on the tetrafluoroborate ion, [B–H]+[BF4]– (‘B•HBF4’), where B is a weak Brønsted base, could serve as an attenuated and better controlled source of nucleophilic fluorine. Moreover, we expected that the acidity, and thus, the reactivity of these reagents could be rationally tuned through the variation of the electronic properties of B. From the point of view of cost and availability, such a reagent would be nearly ideal for the hydrofluorination of alkynes, provided that the hydrofluorination reactions proceed with functional group tolerance and control over the reaction stoichiometry, as well as the regiochemical and stereochemical outcomes. Here, we report the discovery and development of a simple and practical reagent for the stereodivergent hydrofluorination of alkynes which, in most cases, delivers products with excellent control of the regio- and stereoselectivity (Scheme 1C). For certain substitution patterns, we report complementary conditions for the synthesis of either the E or Z isomer of the hydrofluorination product with good to excellent E/Z ratios. The conditions reported here are tolerant of a variety of functional groups, and we applied them to the late-stage functionalization of drug derivatives and the synthesis of fluorinated drug analogs.

A mechanistic study of the process was performed through kinetics experiments and density functional theory (DFT) calculations. These studies support the intermediacy of vinyl cations in the hydrofluorination reaction. They also provide insight into the excellent stereochemical control and account for the ability to selectively obtain the E or Z isomer through the variation of reagent and reaction conditions. Previously, vinyl cations have been generated through several approaches,[23] including metal catalysis,[24,25] photochemical processes,[26] ionization of vinyl iodonium[27] and diazonium species,[28] (pseudo)halide abstraction with Lewis acids,[29,30] as well as protonation of alkynes with strong Brønsted acid or a Brønsted/Lewis acid complex.[31,32] Despite the challenging and specialized conditions that are often required for their generation, the versatility of this intermediate has led to a recent renaissance in their synthetic applications.[33] In this context, the hydrofluorination conditions reported here represent an unprecedentedly mild, stereocontrolled, and functional group compatible approach for utilizing these intermediates.

Results and Discussion

Reaction development

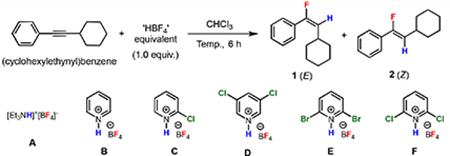

We began the exploration of our hydrofluorination strategy using (cyclohexylethynyl)benzene as a starting material, inspired by the lack of literature precedent employing secondary alkyl-substituted phenylacetylenes as substrates for hydrofluorination (Table 1). We anticipated that the preparation of various amine salts of HBF4 would allow for the tuning of reagent acidity and provide control over hydrofluorination reactivity. Thus, a diverse collection of amine salts of HBF4 was evaluated. While it was found that reagents based on triethylamine (A), pyridine (B), and 2-chloropyridine (C) were unreactive in CHCl3 at room temperature or 70 °C (entries 1–3), the more electron-poor 3,5-dichloropyridinium salt (D) provided a trace of the desired product (entry 4). Continuing with more electron-deficient and strongly acidic pyridinium salts, we found that the 2,6-dihalopyridinium salts (E and F) were more efficient reagents, with the more electron-deficient chlorinated reagent providing the desired product with good yield and excellent stereoselectivity (Z/E > 50:1, entry 6). During the course of optimization, the major side product was identified as 2-cyclohexylacetophenone, formed from adventitious hydration of the alkyne. To further favor fluorination over hydration, additional tetrafluoroborate sources were investigated as additives. When LiBF4 (25 mol %) was added, the yield of the vinyl fluoride was indeed enhanced (entry 7). While diminished, the formation of the ketone could not be suppressed altogether, and under optimized conditions, the ketone was still formed in approximately 10% isolated yield. Importantly, we did not detect the formation of the regioisomeric vinyl fluoride or the gem-difluoride product upon careful examination of the 19F NMR of the crude material.

Table 1.

Optimization of reaction conditions for hydrofluorination

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Fluorinating reagent | Temp./°C | Yield/% | Z/E |

| 1 | A | 70 | 0 | — |

| 2 | B | 70 | 0 | — |

| 3 | C | 70 | 0 | — |

| 4 | D | 70 | < 5 | 1 : 5 |

| 5 | E | 70 | 45 | 36 : 1 |

| 6 | F | 70 | 74 | > 50 : 1 |

| 7 | F | 70 | 82[a] (76)[b] | > 50 : 1 |

| 8 | F | r.t. | < 5 | 1 : 5 |

| 9 | HBF4•Et2O | r.t. | 42[b] | 1 : 11 |

| 10 | HBF4•Et2O | 70 | 0[c] | — |

LiBF4 (25 mol %) was added as an additive.

Isolated yield.

Reaction time: 1 h, with complete conversion of the starting alkyne to tarry materials.

As anticipated, optimization of the reagent structure proved critical for the development of a protocol for hydrofluorination. The tetrafluoroborate salts were generated by the treatment of an ethereal solution of the amine or pyridine with commercially available HBF4•Et2O, followed by filtration to isolate the solid product. This straightforward procedure was readily scaled to allow for the synthesis of reagents on 50 mmol (> 10 g) scale. The acidity of the pyridinium species was found to be a key factor, and pyridinium salts effective for hydrofluorination had aqueous pKa values of –2 or lower. On the other hand, for very weakly basic pyridines (e.g., pentachloropyridine, pKaaq. ~ –8),[34] the abovementioned procedure did not result in an isolable solid material, presumably because the acidity of ethereal fluoroboric acid was insufficient for quantitative protonation of the pyridine. Among the pyridinium salts examined (see SI for details), 2,6-dichloropyridinium tetrafluoroborate (F, pKaaq. = –2.86)[35] possessed the best reactivity and handling properties. In particular, reagent F precipitated from ether as easily filtered crystals. On the other hand, its solubility in hot halogenated solvents (> 0.2 M in CHCl3 at 70 °C) was beneficial for its reactivity. In terms of its handling properties, F was not especially hygroscopic and could be stored as a colorless solid in the desiccator for at least a week or in the glovebox indefinitely (> 3 months) without noticeable deterioration or loss of activity. Thus, when the hydrofluorination of (cyclohexylethynyl)benzene was repeated with the starting materials weighed and reaction tube sealed under air, the decrease in yield was found to be modest, with the yield of 2 decreased to 78% yield by 19F NMR, compared to 82% under standard conditions.

Lastly, we also examined HBF4•Et2O itself as another potential reagent. Surprisingly, we found that treatment of the model substrate with HBF4•Et2O (1.0 equiv) at room temperature for 6 h resulted in the formation of desired hydrofluorination product 1 in moderate yield (42% yield) and good selectivity for the opposite E stereoisomer (E/Z = 11:1, entry 9). Under these conditions, alkyne hydration was a significant side reaction, with 2-cyclohexylacetophenone formed in 30–35% isolated yield. On the other hand, the use of this reagent at 70 °C resulted after 1 h in the complete consumption of starting material and formation of a complex mixture of products (tar), with neither of the stereoisomeric vinyl fluoride products observed by 19F NMR. These results indicate that HBF4•Et2O is a powerful though harsh reagent for hydrofluorination, in contrast to the tempered reactivity of the pyridinium tetrafluoroborates. In spite of the modest yields, we felt that this complementary protocol for generating the E isomer may be of some synthetically utility. Moreover, this intriguing stereochemical outcome prompted us to apply experimental and computational tools to scrutinize the mechanism of the hydrofluorination process.

Substrate scope

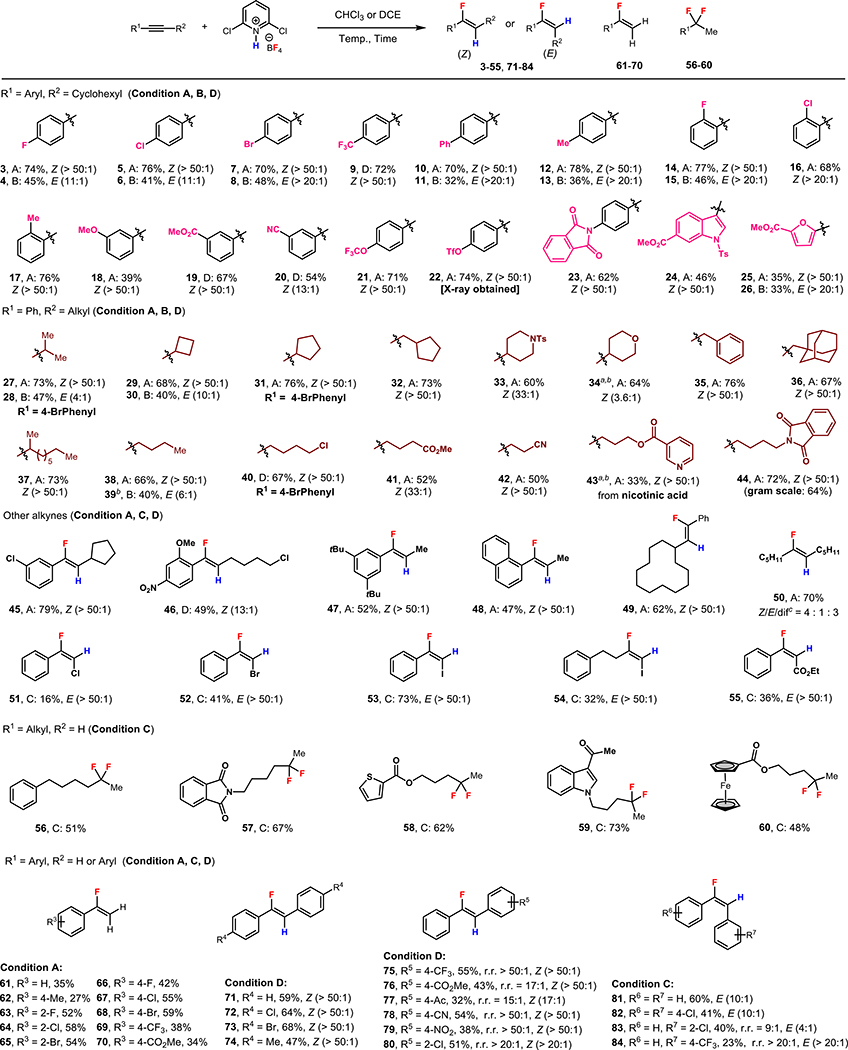

Under these optimized conditions, we set out to investigate the scope of this hydrofluorination reaction (Scheme 2). Using reagent F for hydrofluorination, alkyl aryl acetylenes bearing electron-withdrawing (e.g., products 9, 19, 20, 22) to electron-donating (e.g., products 23, 24, 25) aryl substituents reacted effectively to afford the (Z)-configured fluoroalkene products in moderate to good yields and excellent regio- and stereoselectivities. Moreover, several common functional groups on the aryl ring including a methyl ester (19), a cyano group (20), a trifluoromethanesulfonyl ester (22), and a phthalimide (23) were tolerated. Heteroaryl alkyl acetylenes, including an indole and a furan likewise delivered the desired product (24, 25). The structure of 22 was determined by single crystal X-ray diffraction for confirmation of the alkene stereochemistry.

Scheme 2.

Substrate scope of alkynes. Condition A: fluorinating reagent F (1.0 equiv), LiBF4 (25 mol%), CHCl3 (0.2 M), 70 to 90 °C. Condition B: HBF4·Et2O (1.0 equiv), CHCl3 (0.2 M), r.t., 6 h. Condition C: fluorinating reagent F (3.0 equiv), CHCl3, 80 to 100 °C, 12 h. Condition D: fluorinating reagent F (2.0 equiv), DCE, 70 to 100 °C, 12 h. a1.0 equiv of Et2O•BF3 was used as additive. bgem-difluoroalkane (<5 % 19F NMR yield) was detected. cgem-difluoroalkane; the yield shown is the combined yield of the vinyl fluoride and gem-difluoroalkane products. See the Supporting Information for detailed conditions.

We next explored the scope of alkyl substituents on the substrate. A range of primary, secondary, cyclic or acyclic alkyl-substituted alkynes could be employed in the hydrofluorination to furnish respective products again with moderate to good yields and excellent regio- and stereoselectivities (27-39). Remarkably, substrates with potentially sensitive functional groups including a primary chloro (40, 46), a carboxymethyl (41), a cyano (42), a pyridyl (43), and a phthalimido group (44) also delivered the vinyl fluoride products in moderate to good yields, highlighting the mildness and good functional group tolerance of this protocol. This scalability of the procedure was demonstrated by the gram-scale preparation of 44, which proceeded with unchanged regio- and stereoselectivities and only a slightly reduced yield (1.65 g, 64%). The protocol was insensitive to steric effects on the alkyl substituent, with a methyl group (47, 48) and a cyclododecyl (49) group giving similar yields, both with excellent regio- and stereoselectivities.

It is noteworthy that in hydrofluorination reactions employing alkyl aryl acetylenes, the vinyl fluoride products were delivered exclusively with C–F bond formation taking place adjacent (α) to the aryl group. These results complement Au-catalyzed hydrofluorination procedures, which deliver the fluorine to the carbon adjacent to the alkyl group, β to the aryl group.[7–12] This divergence likely stems from the ability for the aryl group to stabilize both an adjacent positive charge in the case of the current metal-free process and an adjacent C(sp2)–Au bond in case of the Au-catalyzed protocols to give the α– and β–fluorinated regioisomers, respectively.

We also explored the scope of the complementary E-selective hydrofluorination with HBF4•Et2O using a subset of the previously investigated alkyl aryl acetylenes (condition B). Substrates bearing mildly electron-withdrawing or electron-donating substituents could afford the vinyl fluoride products with moderate to very good E-selectivity (E/Z ratio from 4:1 to > 20:1) and modest to moderate yields (32% to 48% yield).

Electron poor substrates like 1-haloalkynes and ethyl phenylpropiolate were also suitable substrates for this reaction. In each case, a single regio- and stereoisomer was produced (51-55). The reactivity order of the 1-halo-2-phenylacetylenes was I > Br > Cl, reflecting the inductive electron withdrawing power of the halogen. In the case of Cl and Br, the low and moderate isolated yields resulted from incomplete conversion of the starting material to the vinyl fluoride product.

The hydrofluorination reaction could also be applied to terminal alkynes and diarylacetylenes. When using terminal alkyl-substituted alkynes as substrates, gem-difluorides were obtained as the primary products with exclusive internal regioselectivity. A variety of functional groups such as a phthalimide (57), a ketone (59), esters (58, 60), an indole (59), as well as a ferrocene derivative (60) were well tolerated. On the other hand, terminal aryl-substituted alkynes could be employed in this hydrofluorination to give the corresponding monofluoroalkene as the major fluorination product with low to moderate yields (61-70). In cases where yield was low (e.g., 61, 62) the major side product observed was the ketone hydration product. With 1,2-dichloroethane as the solvent, symmetrical diarylacetylenes could give corresponding monofluoroalkene products in moderate to good yields and excellent Z-selectivities (71-74). For unsymmetrical substrates, when one of the benzene rings was substituted by an electron-withdrawing group (e.g., 4-CO2Me, 2-Cl), the hydrofluorination proceeded with excellent Z-selectivities and was regioselective for fluorination nearer the more electron-rich aryl group (75-80). Finally, it was found that by switching to chloroform as the solvent, the monofluoroalkene product could be formed with E-selectivity (81-84).

With the exception of dialkyl acetylenes, the gem-difluoride product was either not observed (<1%) or observed as very minor components (1–5% yield by 19F NMR) of the crude product. However, a reduction in selectivity was observed for a dialkylacetylene substrate, which gave the gem-difluoroalkane in addition monofluorinated product (50, 4:1 Z/E, 5:3 vinyl fluorides/difluoroalkane). In the alkyl aryl acetylenes and terminal acetylenes, no evidence of the other regioisomeric hydrofluorination product could be observed (< 1%) in the crude material by 19F NMR. In the case of the hydrofluorination of diarylacetylenes, regioisomeric products were sometimes observed. When direct comparisons were available (for 75, 77, 82), the regioisomeric ratios (15:1 to > 20:1) exceeded those previous reported for the Au-catalyzed transformation (2:1 to 4.3:1).[12]

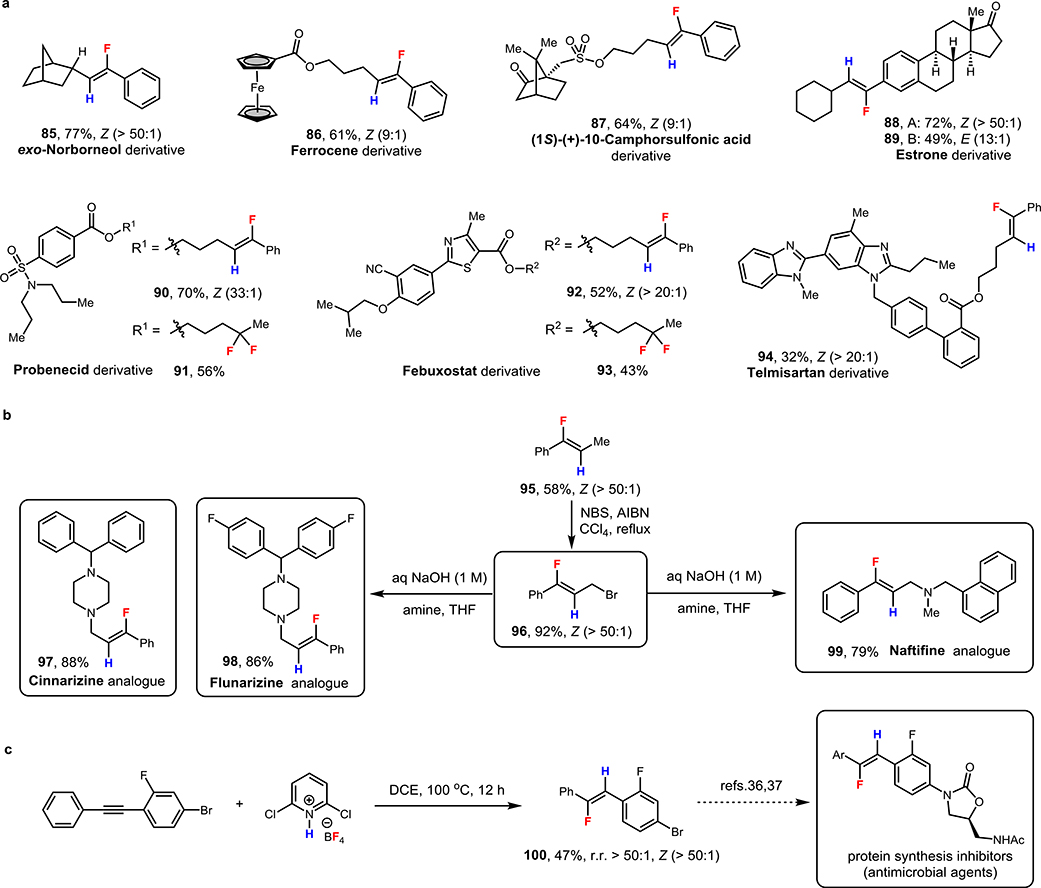

Synthetic applications

To demonstrate the potential applicability of this new hydrofluorination method to the late-stage modification of structurally complex substrates, including biologically active molecules and natural products, we explored several readily available alkynes derived from exo-norborneol (85) and ferrocene (86), natural products (1S)-(+)-10-camphorsulfonic acid (87) and estrone (88, 89), as well as drug molecules probenecid (90), febuxostat (92) and telmisartan (94) to afford monofluoroalkene products with moderate to good yields and high regio- and stereoselectivities (Scheme 3a). In addition, terminal alkyl-substituted alkynes derived from drug molecules probenecid and febuxostat could also be employed in the dihydrofluorination to form gem-difluorides with moderate yields and exclusive regioselectivity (91, 93). These examples demonstrated that our hydrofluorination and difluorination protocols were suitable for the late-stage, protecting-group-free modification of biologically active molecules and could tolerate a range of functional groups and heterocycles including ketones (87-89), esters (90-94), a ferrocene (86), a sulfonate (87), a sulfonamide (90, 91), a nitrile (92, 93), a thiazole (92, 93), and benzimidazoles (94).

Scheme 3.

Synthetic applications of stereodivergent alkyne hydrofluorination. a, The late-stage modification of biologically active molecules or complex natural products. b, The synthesis of different fluorinated analog of drug molecules. c, The preparation of key intermediate for the synthesis of antimicrobial agents with high regio- and Z/E-selectivities. See supporting information for detailed conditions.

To explore other applications of this chemistry, we prepared 95 on 5-mmol scale to access fluorinated analogs of antihistamines cinnarizine (97), flunarizine (98) and antifungal drug naftifine (99) (Scheme 3b). Via allylic bromination of 95, we prepared a common brominated intermediate 96, which could be applied to synthesize all three analogs. Moreover, we also prepared vinyl fluoride 100, a known precursor for the synthesis of antimicrobial agents (protein synthesis inhibitors) through the coupling with 2-oxazolidone (Scheme 3c).[36,37] These transformations demonstrate the excellent potential of this method for future applications in a drug discovery setting.

Mechanistic discussion

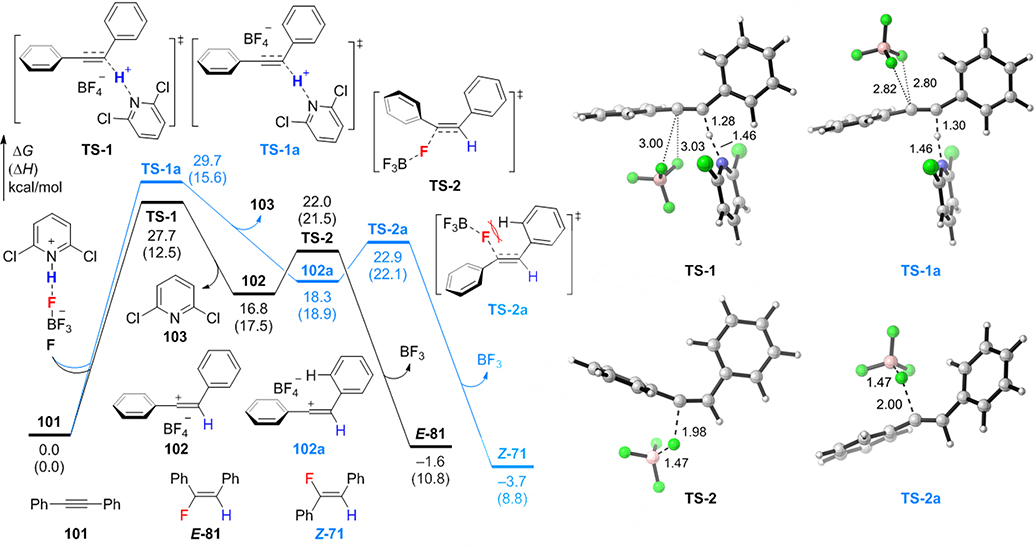

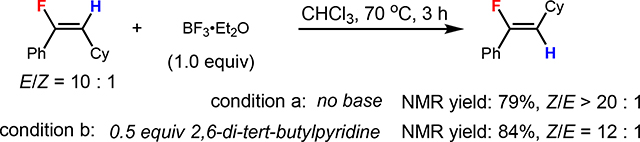

The experimental results have demonstrated that 2,6-dichloropyridinium tetrafluoroborate is an effective fluorinating reagent for stereodivergent alkyne hydrofluorination. As shown in Scheme 2, high levels of Z-selectivity are obtained in a polar solvent (i.e. DCE, condition D), while reactions in a less polar solvent (i.e. chloroform, condition C) or under lower temperatures (see SI) completely switch the stereoselectivity to favor E-products. Mechanistic studies were then performed to investigate whether the hydrofluorination occurs through a concerted or stepwise mechanism and the origin of the divergent stereoselectivity. DFT calculations[38] of the hydrofluorination of 1,2-diphenylacetylene 101 indicated a stepwise AdE2-type protonation-fluorination mechanism with a BF4−/vinyl cation ion-pair intermediate (Figure 1). Prior to the alkyne protonation, the H⋯F hydrogen bond in the fluorinating reagent F dissociates to release a free pyridinium cation as the proton source. Two protonation transition states were located (TS-1 and TS-1a), in which the tetrafluoroborate anion is syn and anti to the pyridinium, respectively. Bonding interactions between BF4− and the alkyne were not observed in either protonation transition state, which is likely due to the weak nucleophilicity of BF4−. The stepwise hydrofluorination mechanism is confirmed by intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) calculations, which indicated that TS-1 and TS-1a lead to BF4−/vinyl cation ion pairs 102 and 102a, respectively, rather than the direct formation of hydrofluorination products. Fluorination of the highly electrophilic vinyl cation with BF4− (via TS-2 and TS-2a) is facile, which makes protonation (TS-1) the rate-determining step. This mechanistic picture is consistent with experimental Hammett analysis (Scheme 4C) and kinetics studies (see SI for details), which indicated a ρ value of –3.43 consistent with previously reported vinyl cation-mediated reactions[23] and first-order kinetics in alkyne and H+ and zero-order kinetics in excess BF4− (Scheme 4C). The E-selective pathway (shown in black in Fig. 1) is kinetically favored in both protonation and fluorination steps. The syn-protonation transition state TS-1 is more stable than the anti-TS (TS-1a) due to more favorable electrostatic interactions between BF4– and the pyridinium cation. The E-selective fluorination transition state TS-2 is 0.9 kcal/mol more stable than the Z-selective fluorination (TS-2a) because of steric repulsions[21] between BF4− and the β-phenyl group in TS-2a.[39] Therefore, regardless of whether ion pairs 102 and 102a have sufficient lifetime to interconvert prior to the fluorination, kinetic E-selectivity is expected. The relatively low barrier for the reverse reaction of E-81 (via TS-2, ΔG‡ = 23.6 kcal/mol) to generate the vinyl cation indicates the E-to-Z vinyl fluoride isomerization may occur at elevated temperatures through BF3-mediated fluoride anion elimination followed by fluorination of the vinyl cation via TS-2a. A polar solvent, which could stabilize ion-pair intermediates 102 and 102a, is expected to promote such isomerization (see Fig. S15 in the SI for energy profiles computed in DCE). Because the Z-stereoisomer Z-71 is 2.3 kcal/mol more stable than E-71, high Z-selectivity is expected under these thermodynamically controlled conditions.

Figure 1.

Reaction energy profiles of the hydrofluorination of 1,2-diphenylacetylene 101 with 2,6-dichloropyridinium tetrafluoroborate. The bond lengths are in angstrom. All energies were calculated at the M06–2X/6–311+G(d,p)/SMD(chloroform)//M06–2X/6–31+G(d)/SMD(chloroform) level of theory. See Fig. S10 and S11 in SI for the computational results with the cyclohexyl and methyl-substituted alkynes.

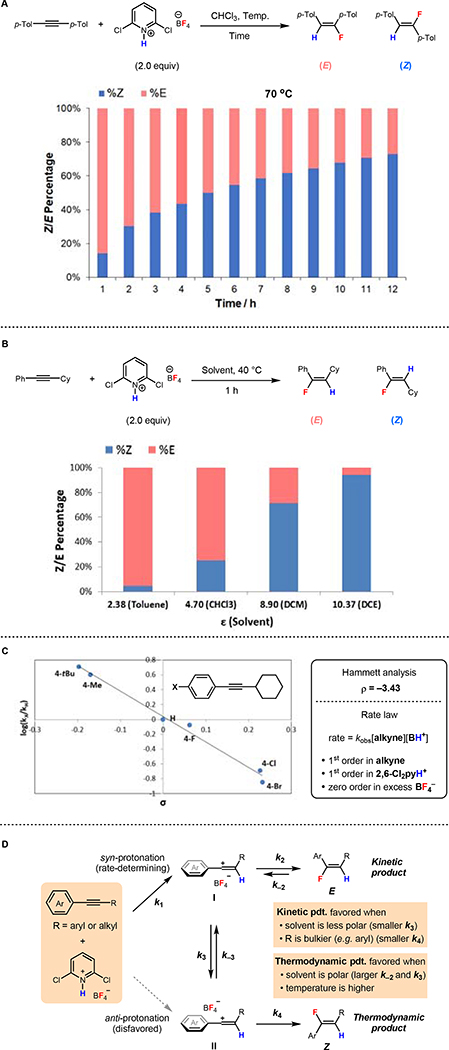

Scheme 4.

Mechanistic studies A. Change of the Z/E-ratio of the hydrofluorination product over the course of reaction and the variation of temperature. B. Dielectric constant study. C. Hammett-plot analysis for para-substituted aryl cyclohexyl alkynes and kinetic studies. See supporting information for detailed conditions. D. Proposed mechanism for the stereodivergent hydrofluorination of alkyne

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

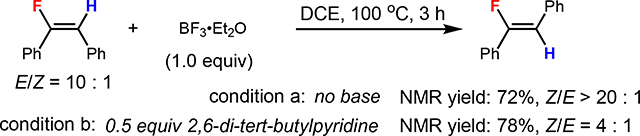

In light of the strength of the C(sp2)–F bond (124 kcal/mol),[40] the reversibility of C–F bond formation seemed surprising, and we sought to obtain experimental support. The BF3-mediated E/Z-vinyl fluoride isomerization was verified experimentally under conditions with Et2O•BF3 (eqs 1 and 2). The addition of 2,6-di-tert-butylpyridine did not shut down the BF3-mediated isomerization, which excludes the possibility that the presence of a Brønsted acid is required for isomerization.[41] In certain cases, (e.g., 86 and 87), we observed that better Z-selectivity could be obtained by addition of exogenous Et2O•BF3 to promote E-to-Z-isomerization (see the SI for detailed conditions). In addition, the increase of the Z-product ratio over a reaction time of 12 h at 70 °C further confirmed the isomerization of the kinetic E-isomer to Z-vinyl fluoride in the hydrofluorination of di-p-tolylacetylene (E/Z ratio from 6:1 to 1:2.4) (Scheme 4A). Further experimental study of the dielectric constant of solvent suggested that higher Z-selectivity could be obtained when increasing the dielectric constant of solvent (E/Z ratio from 20:1 to 1:16.2) (Scheme 4B), which verified the hypothesis that polar solvent could promote E-to-Z-vinyl fluoride isomerization. The increase of reaction temperature was also found to favor the formation of Z-vinyl fluoride (see the SI for details).

Based on these mechanistic studies, a general mechanism is proposed to elucidate the stereoselectivity control in the alkyne hydrofluorination (Scheme 4D). The rate-determining syn-protonation of alkyne (k1) leads to an ion pair intermediate (I), which then undergoes fluorination (k2) to afford the kinetically favored E-vinyl fluoride. The thermodynamically more stable Z-product is formed from the isomerization of the E-vinyl fluoride, which takes place via BF3-mediated fluoride dissociation (k-2) and isomerization of the ion pair intermediate (k3) followed by Z-selective fluorination with BF4– (k4). The experimental and computational mechanistic studies revealed several factors that control the rate of the E-to-Z isomerization and thus the E/Z-selectivity. Higher temperatures and polar solvents (e.g. DCE) promote the BF3-mediated fluoride dissociation (k-2) to form the ion pair intermediate (I). Experimentally, excess BF4− (condition A) was also found to favor the formation of the Z-isomer (see SI), an effect that may be ascribed to the increased availability of BF4− for anti-attack (k4) or a change in the solvent polarity due to higher ionic content. In addition, our DFT calculations suggested that sterically less hindered alkyne substituents (e.g. R = methyl) lead to lower barriers to the Z-selective fluorination (k4) due to diminished steric repulsions with BF4– in the fluorination transition state. On the other hand, lower temperatures (e.g. in the HBF4•Et2O mediated hydrofluorination), less polar solvents, and bulkier alkyne substituents (e.g. R = aryl) that suppress the ion pair isomerization (k3) and the Z-selective fluorination (k4) would lead to higher E-selectivity under kinetic control.

Conclusion

We have developed a simple, practical, and metal-free strategy for the regio- and stereoselective controlled mono- and dihydrofluorination of alkynes by employing 2,6-dichloropyridinium tetrafluoroborate as a new, safe, and stable fluorinating reagent. Mechanistic and DFT studies reveal that the stereoselectivity of hydrofluorination results from either kinetic or thermodynamic control in a stepwise protonation-fluorination pathway. We anticipate that this hydrofluorination protocol will find wide applications in drug discovery and related fields by facilitating the preparation of fluorinated molecules of biological interest. Studies further exploiting the synthetic applications of vinyl cation intermediates generated under similar mild conditions are ongoing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the University of Pittsburgh and the NIH (R35GM128779) for financial support for this work. DFT calculations were performed at the Center for Research Computing at the University of Pittsburgh and the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE) supported by the National Science Foundation grant number ACI-1548562.

Contributor Information

Rui Guo, Department of Chemistry, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15260, United States.

Xiaotian Qi, Department of Chemistry, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15260, United States.

Hengye Xiang, Department of Chemistry, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15260, United States.

Paul Geaneotes, Department of Chemistry, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15260, United States.

Ruihan Wang, Department of Chemistry, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15260, United States.

Peng Liu, Department of Chemistry, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15260, United States.

Yi-Ming Wang, Department of Chemistry, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15260, United States.

References

- [1].(a) Haufe G, Leroux FR, Fluorine in Life Sciences: Pharmaceuticals, Medicinal Diagnostics, and Agrochemicals; Elsevier: London, 2019. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang J, Sánchez-Roselló M, Aceña JL, del Pozo C, Sorochinsky AE, Fustero S, Soloshonok VA, Liu H, Fluorine in pharmaceutical industry: fluorine-containing drugs introduced to the market in the last decade. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 2432–2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Purser S, Moore PR, Swallow S, Gouverneur V, Fluorine in medicinal chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 320–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Müller K, Faeh C, Diederich F, Fluorine in Pharmaceuticals: Looking Beyond Intuition. Science 2007, 317, 1881–1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Bégué JP, Bonnet-Delpon D, Recent advances (1995–2005) in fluorinated pharmaceuticals based on natural products. J. Fluorine Chem. 2006, 127, 992–1012. [Google Scholar]; (f) Isanbor C, O’Hagan D, Fluorine in medicinal chemistry: A review of anti-cancer agents. J. Fluorine Chem. 2006, 127, 303–319. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Overviews of vinyl fluorides in medicinal chemistry: [Google Scholar]; (a) Meanwell NA, Fluorine and Fluorinated Motifs in the Design and Application of Bioisosteres for Drug Design. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 5822–5880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bégué J-P, Bonnet-Delpon D, Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry of Fluorine. p.18, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey, 2008. Applications of vinyl fluorides in medicinal chemistry: [Google Scholar]; (c) Milczek EM, Bonivento D, Binda C, Mattevi A, McDonald IA, Edmondson DE, Structural and Mechanistic Studies of Mofegiline Inhibition of Recombinant Human Monoamine Oxidase B. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 8019–8026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Edmondson SD, Wei L, Xu J, Shang J, Xu S, Pang J, Chaudhary A, Dean DC, He H, Leiting B, Lyons KA, Patel RA, Patel SB, Scapin G, Wu JK, Beconi MG, Thornberry NA, Weber AE, Fluoroolefins as amide bond mimics in dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 2409–2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Dutheuil G, Couve-Bonnaire S, Pannecoucke X, Diastereomeric fluoroolefins as peptide bond mimics prepared by asymmetric reductive amination of ɑ-fluoroenones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 1290–1292; Angew. Chem. 2007, 119, 1312–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].(a) Caron S Where Does the Fluorine Come From? A Review on the Challenges Associated with the Synthesis of Organofluorine Compounds. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2020, 24, 470–480. [Google Scholar]; (b) Liang S; Hammond GB; Xu B Functionalization of Alkynes for Preparing Alkenyl Fluorides. In: Hu J; Umemoto T (eds) Fluorination. Synthetic Organofluorine Chemistry. Springer: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar]; (c) Champagne PA, Desroches J, Hamel J-D, Vandamme M, Paquin J-F, Monofluorination of Organic Compounds: 10 Years of Innovation. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 9073–9174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Besset T; Poisson T; Pannecoucke X Direct Vicinal Difunctionalization of Alkynes: An Efficient Approach Towards the Synthesis of Highly Functionalized Fluorinated Alkenes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 2765–2789. [Google Scholar]; (e) Landelle G; Bergeron M; Turcotte-Savard MO; Paquin JF Synthetic Approaches to Monofluoroalkenes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 2867–2908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Yanai H, Taguchi T, Synthetic Methods for Fluorinated Olefins. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 5939–5954. [Google Scholar]; (g) Koh MJ, Nguyen TT, Zhang H, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH, Direct synthesis of Z-alkenyl halides through catalytic cross-metathesis. Nature 2016, 531, 459–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Steenis JH, Gen A, Synthesis of terminal monofluoro olefins. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1, 2002, 19, 2117–2133. [Google Scholar]; (i) Zajc B, Kumar R, Synthesis of Fluoroolefins via Julia-Kocienski Olefination. Synthesis 2010, 11, 1822–1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Hara S, Stereoselective Synthesis of Mono-fluoroalkenes. In: Wang J (eds) Stereoselective Alkene Synthesis. Topics in Current Chemistry, vol 327, 59. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Pfund E, Lequeux T, Gueyrard D, Synthesis of Fluorinated and Trifluoromethyl-Substituted Alkenes through the Modified Julia Olefination: An Update. Synthesis 2015, 47, 1534–1546. [Google Scholar]; (l) Drouin M, Hamel J-D, Paquin J-F, Synthesis of Monofluoroalkenes: A Leap Forward. Synthesis 2018, 50, 881–955. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ye Y, Takada T, Buchwald SL, Palladium-Catalyzed Fluorination of Cyclic Vinyl Triflates: Effect of TESCF3 as an Additive. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 15559–15563; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 15788–15792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].(a) Lee SH, Schwartz J, Stereospecific Synthesis of Alkenyl Fluorides (with Retention) via Organometallic Intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 2445–2447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Petasis NA, Yudin AK, Zavialov IA, Prakash GKS, Olah GA, Facile Preparation of Fluorine-containing Alkenes, Amides and Alcohols via the Electrophilic Fluorination of Alkenyl Boronic Acids and Trifluoroborates. Synlett 1997, 5, 606–608. [Google Scholar]; (c) Greedy B, Gouverneur V, Fluorodesilylation of alkenyltrimethylsilanes: a new route to fluoroalkenes and difluoromethyl-substituted amides, alcohols or ethers. Chem.Commun. 2001, 233–234. [Google Scholar]; (d) Matthews DP, Miller SC, Jarvi ET, Sabol JS, McCarthy JR, A new method for the electrophilic fluorination of vinyl stannanes. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993, 34, 3057–3060. [Google Scholar]; (e) Tius MA, Kawakami JK, Vinyl Fluorides from Vinyl Stannanes. Synth. Commun. 1992, 22, 1461–1471. [Google Scholar]; (f) Tius MA, Kawakami JK, Rapid Fluorination of Alkenyl Stannanes with Silver Triflate and Xenon Difluoride. Synlett 1993, 3, 207–208. [Google Scholar]; (g) Tius MA, Kawakami JK, The reaction of XeF2 with trialkylvinylstannanes: Scope and some mechanistic observations. Tetrahedron 1995, 51, 3997–4010. [Google Scholar]; (h) Furuya T, Ritter T, Fluorination of Boronic Acids Mediated by Silver(I) Triflate. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 2860–2863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Sommer H, Fürstner A, Stereospecific Synthesis of Fluoroalkenes by Silver-Mediated Fluorination of Functionalized Alkenylstannanes. Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 558–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Makaravage KJ, Brooks AF, Mossine AV, Sanford MS, Scott PJH, Copper-Mediated Radiofluorination of Arylstannanes with [18F]KF. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 5440–5443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].G. A. Jr., U. S. Patent 4 212 815, 1980.

- [7].Akana JA, Bhattacharyya KX, Muller P, Sadighi JP, Reversible C−F Bond Formation and the Au-Catalyzed Hydrofluorination of Alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 7736–7737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gorske BC, Mbofana CT, Miller SJ, Regio- and Stereoselective Synthesis of Fluoroalkenes by Directed Au(I) Catalysis. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 4318–4321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Okoromoba OE, Han J, Hammond GB, Xu B, Designer HF-Based Fluorination Reagent: Highly Regioselective Synthesis of Fluoroalkenes and gem-Difluoromethylene Compounds from Alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 14381–14384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].(a) Nahra F, Patrick SR, Bello D, Brill M, Obled A, Cordes DB, Slawin AM, O’Hagan D, Nolan SP, Hydrofluorination of Alkynes Catalysed by Gold Bifluorides. ChemCatChem 2015, 7, 240–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gómez-Herrera A, Nahra F, Brill M, Nolan SP, Cazin CSJ, Sequential functionalization of alkynes and alkenes catalyzed by gold(I) and palladium (II) N-heterocyclic carbene complexes. ChemCatChem 2016, 8, 3381–3388. [Google Scholar]

- [11].(a) Zeng X, Liu S, Hammond GB, Xu B, Divergent Regio- and Stereoselective Gold-catalyzed Synthesis of α-Fluorosulfones and β- Fluorovinylsulfones from Alkynylsulfones. Chem. - Eur. J. 2017, 23, 11977–11981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) O’Connor TJ, Toste FD, Gold-Catalyzed Hydrofluorination of Electron-Deficient Alkynes: Stereoselective Synthesis of β-Fluoro Michael Acceptors. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 5947–5951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gauthier R, Mamone M, Paquin J-F, Gold-Catalyzed Hydrofluorination of Internal Alkynes Using Aqueous HF. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 9024–9027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].(a) He G, Qiu S, Huang H, Zhu G, Zhang D, Zhang R, Zhu H, Cu(I)- or Ag(I)-catalyzed regio- and stereocontrolled trans-hydrofluorination of ynamides. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 1856–1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhu G, Qiu S, Xi Y, Ding Y, Zhang D, Zhang R, He G, Zhu H, (IPr)CuF-catalyzed ɑ-site regiocontrolled trans-hydrofluorination of ynamides. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14, 7746–7753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].(a) Li Y, Liu X, Ma D, Liu B, Jiang H, Silver-assisted difunctionalization of terminal alkynes: highly regio- and stereoselective synthesis of bromofluoroalkenes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012, 354, 2683–2688. [Google Scholar]; (b) Che J, Li Y, Zhang F, Zheng R, Bai Y, Zhu G, Silver-promoted trans-hydrofluorination of ynamides: a regio- and stereoselective approach to (Z)-a-fluoroenamides. Tetrahedron Lett 2014, 55, 6240–6242. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Brown JM, Gouverneur V, Transition-Metal-Mediated Reactions for Csp2-F Bond Construction: The State of Play. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 8610–8614; Angew. Chem. 2009, 121, 8762–8766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Davies SG, Roberts PM, Tetrafluoroborate Salt Fluorination for Preparing Alkyl Fluorides; Springer: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Cresswell AJ, Davies SG, Roberts PM, Thomson JE, Beyond the Balz−Schiemann Reaction: The Utility of Tetrafluoroborates and Boron Trifluoride as Nucleophilic Fluoride Sources. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 566–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].(a) Vollhardt KPC, Schore NE, Organic Chemistry: Structure and Function. 8th ed., p.607, W. H. Freeman and Company, New York, 2018. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fahey RC, Payne MT, Lee D-J, Reaction of acetylenes with hydrogen chloride in acetic acid. Effect of structure upon AdE2 and Ad3 reaction rates. J. Org. Chem. 1974, 39, 1124–1130. [Google Scholar]; (c) Marcuzzi F, Melloni G, Electrophilic additions to acetylenes. V. Stereochemistry of the electrophilic addition of alkyl halides and hydrogen halides to phenyl-substituted acetylenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976, 98, 3295–3300. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Olah GA, Welch JT, Vankar YD, Nojima M, Kerekes I, Olah JA, Synthetic Methods and Reactions. 63. Pyridinium Poly(hydrogen fluoride) (30% Pyridine-70% Hydrogen Fluoride): A Convenient Reagent for Organic Fluorination Reactions. J. Org. Chem. 1979, 44, 3872–3881. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lu Z, Bajwa BS, Liu S, Lee S, Hammond GB, Xu B, Solventless and metal-free regioselective hydrofluorination of functionalized alkynes and allenes: an efficient protocol for the synthesis of gem-difluorides. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 1467–1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Compain G, Jouvin K, Martin-Mingot A, Evano G, Marrot J, Thibaudeau S, Stereoselective hydrofluorination of ynamides: a straightforward synthesis of novel α-fluoroenamides. Chem. Commun, 2012, 48, 5196–5198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bello D, O’Hagan D, Lewis acid-promoted hydrofluorination of alkynyl sulfides to generate α-fluorovinyl thioethers. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2015, 11, 1902–1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Stang PJ, Rappoport Z, Hanack M, Subramanian LR, Vinyl Cations; Academic Press: San Diego, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kreuzahler M, Daniels A, Wölper C, Haberhauer G, 1,3-Chlorine Shift to a Vinyl Cation: A Combined Experimental and Theoretical Investigation of the E‑Selective Gold(I)-Catalyzed Dimerization of Chloroacetylenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 1337–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Walkinshaw AJ, Xu W, Suero MG, Gaunt MJ, Copper-Catalyzed Carboarylation of Alkynes via Vinyl Cations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 12532–12535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kitamura T, Kobayashi S, Taniguchi H, Photochemistry of vinyl halides. Vinyl cation from photolysis of 1,1-diaryl-2-halopropenes. J. Org. Chem. 1982, 47, 2323–2328. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hinkle RJ, McNeil AJ, Thomas QA, Andrews MN, Primary Vinyl Cations in Solution: Kinetics and Products of β,β-Disubstituted Alkenyl(aryl)iodonium Triflate Fragmentations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 32, 7437–7438. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Cleary SE, Hensinger MJ, Qin Z-X, Hong X, Brewer M, Migratory Aptitudes in Rearrangements of Destabilized Vinyl Cations. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 15154–15164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Popov S, Shao B, Bagdasarian AL, Benton TR, Zou L, Yang Z, Houk KN, Nelson HM, Teaching an old carbocation new tricks: Intermolecular C–H insertion reactions of vinyl cations. Science 2018, 361, 381–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wigman B, Popov S, Bagdasarian AL, Shao B, Benton TR, Williams CG, Fisher SP, Lavallo V, Houk KN, Nelson HM, Vinyl Carbocations Generated under Basic Conditions and Their Intramolecular C−H Insertion Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 9140–9144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Schroeder S, Strauch C, Gaelings N, Niggemann M, Vinyl Triflimides—A Case of Assisted Vinyl Cation Formation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 5119–5123; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 5173–5177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Pons A, Michalland J, Zawodny W, Chen Y, Tona V, Maulide N, Vinyl Cation Stabilization by Silicon Enables a Formal Metal-Free α-Arylation of Alkyl Ketones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 17303–17306; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 17463–17467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Niggemann M, Gao S, Are Vinyl Cations Finally Coming of Age? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 16942–16944; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 17186–17188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Paukshtis EA, Yurchenko EN, Study of the Acid–Base Properties of Heterogeneous Catalysts by Infrared Spectroscopy. Russ. Chem. Rev. 1983, 52, 242–258. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Tehan BG, Lloyd EJ, Wong MG, Pitt WR, Gancia E, D.T. Manallack, Estimation of pKa Using Semiempirical Molecular Orbital Methods. Part 2: Application to Amines, Anilines and Various Nitrogen Containing Heterocyclic Compounds. Quant. Struct.-Act. Relat. 2002, 21, 473–485. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sciotti RJ, Pliushchev M, Wiedeman PE, Balli D, Flamm R, Nilius AM, Marsh K, Stolarik D, Jolly R, Ulrich R, Djuric SW, The Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of a Novel Series of Antimicrobials of the Oxazolidinone Class. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2002, 12, 2121–2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Li J, Zhang Y, Jiang Y, Ma D, CuI/N,N-dimethylglycine-catalyzed synthesis of N-aryloxazolidinones from aryl bromides. Tetrahedron Letters 2012, 53, 3981–3983. [Google Scholar]

- [38].All density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed using Gaussian 16 package at M06-2X/6-311+G(d,p)/SMD(chloroform)//M06-2X/6-31+G(d)/SMD(chloroform) level of theory. See SI for computational details.

- [39].In the fluorination of ion pair complex formed in the reaction with phenyl methyl acetylene, the Z-selective fluorination transition state has a 0.9 kcal/mol lower barrier than the E-selective fluorination TS (see Figure S11 in SI for complete reaction pathway with this alkyne) because of the diminished steric repulsion between BF4- and the smaller methyl substituent on the vinyl cation.

- [40].Pedley JB, Naylor RD, Kirby SP, Thermochemical Data of Organic Compounds 2nd ed., Chapman and Hall, New York, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- [41].We cannot completely exclude the presence of a second Brønsted acid mediated isomerization pathway that takes place concurrently. Such a pathway was computed to have an overall barrier of 27.2 kcal/mol, making it less favorable than the BF3-mediated isomerization. See the Supporting Information for details.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.