Abstract

There is evidence of an association between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and criminal justice involvement among military veterans. For this study, we systematically reviewed the literature to examine the association between PTSD and criminal justice involvement among military veterans, assess the magnitude of this association, and identify strengths and limitations of the underlying evidence. Five databases were searched for a larger scoping review, and observational studies that assessed PTSD and criminal justice involvement were selected from the scoping review database (N = 191). Meta-analyses were conducted, pooling odds ratios (ORs) via restricted maximum likelihood random-effects models. The main outcomes were criminal justice involvement (i.e., documentation of arrest) and PTSD (i.e., PTSD assessment score indicating probable PTSD). Of 143 unique articles identified, 10 studies were eligible for the meta-analysis. Veterans with PTSD had higher odds of criminal justice involvement (OR = 1.61, 95% CI [1.16, 2.23], p = .002) and arrest for violent offenses (OR = 1.59, 95% CI [1.15, 2.19], p = .002) compared to veterans without PTSD. The odds ratio of criminal justice involvement among military veterans with PTSD assessed using the PTSD Checklist was 1.98, 95% CI [1.08, 3.63], p = .014. Considerable heterogeneity was identified, but no evidence of publication bias was found. Criminal justice involvement and PTSD are linked among military veterans, highlighting an important need for clinicians and healthcare systems working with this population to prioritize PTSD treatment to reduce veterans’ new and recurring risk of criminal justice involvement.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is an important mental health condition, with a lifetime prevalence of 6.8% among the general United States population (Harvard Medical School, 2007). Military veterans are at an increased risk for PTSD due combat exposure and other traumatic military experiences (Xue et al., 2015); the lifetime prevalence of PTSD is between 8% and 30% in this population, depending on the era of military service (Gradus, 2013; Wisco et al., 2014). Additionally, PTSD has been linked to chronic pain, health-related disability, alcohol use disorder, migraines, sleep disturbances, and mortality (Ahmadi et al., 2011; El-Gabalawy, Blaney, Tsai, Sumner, & Pietrzak, 2018; Outcalt et al., 2015; Walton et al., 2018). Untreated PTSD has been associated with both economic burdens and individual health consequences, yet treatment engagement is low. For example, in a large sample of veterans who had been diagnosed with PTSD, only one-third of participants received at least three sessions of mental health treatment (Doran, Pietrzak, Hoff, & Harpaz-Rotem, 2017; McCrone, Knapp, & Cawkill, 2003).

Additionally, PTSD has been linked with criminal justice involvement, including being arrested or incarcerated (Anderson, Geier, & Cahill, 2016; Elbogen et al., 2012; Sherman, Fostick, & Zohar, 2014). Veterans who screen positive for PTSD and military sexual trauma have been shown to be more likely to report legal problems compared to those who do not (Backhaus, Gholizadeh, Godfrey, Pittman, & Afari, 2016). The associations among PTSD, combat exposure, and violence are less clear. Among military veterans in the United Kingdom, PTSD and combat exposure have been significantly associated with violent offending (Macmanus et al., 2013). However, in a sample of U.S. veterans, the link between PTSD and past-year violence was only shown to be present in those who also reported anger symptoms (Novaco & Chemtob, 2015).

Justice-involved military veterans have demonstrated higher rates of PTSD and trauma exposure compared to the general justice-involved population. National data from a U.S. Department of Justice report demonstrated that male veterans in jails and prisons in the United States were twice as likely to have been diagnosed with PTSD compared to civilian incarcerated males (Bronson, Carson, Noonan, & Berzofsky, 2015). Additionally, incarcerated male veterans have been shown to be more likely than incarcerated male civilians to have experienced at least one physical trauma (Greenberg & Rosenheck, 2012). Understanding the association between PTSD and criminal justice involvement, as well as the strengths and limitations of the studies examining this association, will aid clinicians and healthcare systems that serve military veterans.

Identifying an association between PTSD and criminal justice involvement has both theoretical and clinical implications. First, establishing a link between PTSD and criminal justice involvement could inform theoretical models of causal pathways between mental health conditions and criminal justice involvement. Second, understanding if and how PTSD and criminal justice involvement are related could support effective treatment planning, including prioritizing trauma-informed care within the criminal justice system to simultaneously address a mental health need (i.e., PTSD) and reduce criminal recidivism. Finally, describing a link between PTSD and criminal justice involvement could support the need for systems-level interventions, such as the need to screen for and treat PTSD early to prevent criminal justice involvement and reduce PTSD symptoms that can be perpetuated by involvement in the justice system. The purpose of the present study was to systematically review and analyze published studies that have examined veterans (a) with and without PTSD and (b) their criminal justice involvement, including current or past arrests, incarceration, or criminal charges. Due to notable differences in oversight and operations between the active duty and veteran healthcare and justice systems, we examined only studies of veteran populations. We hypothesized that veterans with PTSD would have higher odds of criminal justice involvement compared to veterans without PTSD.

Method

Search Strategy

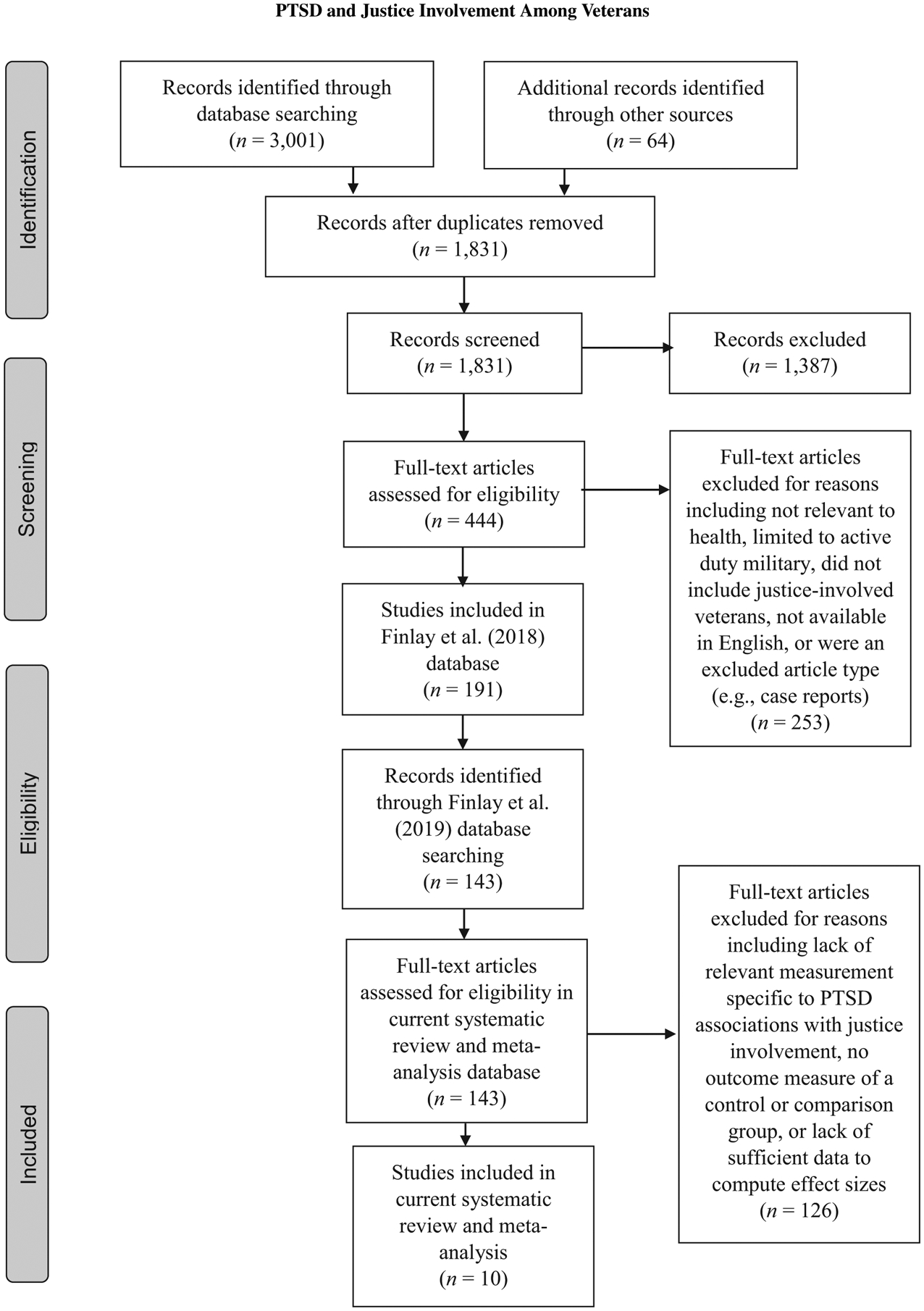

For this systematic review and meta-analysis, we followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009). As this was a review and meta-analysis of publicly available and deidentified data, it was not subject to institutional review board approval. Figure 1 is a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) that maps the records identified and excluded. Relevant articles were pulled from a larger scoping review on justice-involved veterans, health, and healthcare (Finlay et al., 2019). The purpose of a scoping review is to map key concepts underlying a larger field of research to identify gaps in the extant literature and areas for new research (Peters et al., 2015). For the scoping review, five databases were searched: MEDLINE/PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, CINAHL, and PsychInfo. Keywords included veterans or former military, as well as justice-related terms such as prisoners, jail, court, or probation. There were no date restrictions on searched articles (see the Supplementary Materials for a full list of search algorithms and terms used). The initial search was implemented on June 2, 2017. Alerts were created in the selected search engines and articles were added through November 2017. Duplicates were removed prior to abstract review. Rayyan, a free web application used in systematic reviews for screening abstracts and titles, was used to conduct the abstract review (Ouzzani, Hammady, Fedorowicz, & Elmagarmid, 2016).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection (Moher et al., 2009).

In the larger scoping review, there were 1,831 abstracts reviewed and 1,387 excluded studies. Studies were excluded if they did not include justice-involved veterans, were not relevant to health or healthcare (e.g., the authors reported only criminal justice–related outcomes), were limited to active duty military, or did not include results specific to justice-involved veterans. Additionally, consistent with previous studies, some types of articles were excluded (Danan et al., 2017), including case reports, law articles or briefs, meeting abstracts, editorials, letters, protocols, and literature or systematic reviews and brief news articles that did not contain original empirical results. Articles that were not in English or did not have a published English translation were also excluded. Non–peer-reviewed publications and dissertations were included if they were publicly available in a published form (e.g., government reports) and exhibited scientifically rigorous methods (e.g., had a sufficient sample size for statistical analysis). The research team completed a full-text review of 444 articles, and a 10% random sample of full-text articles was independently reviewed for agreement by two authors. There was initially 91% agreement, with disagreements discussed among the research team to reach 100% consensus. Additionally, we mined references from articles to identify any missing work. A total of 191 studies were selected for inclusion in the larger scoping review. The current systematic review and meta-analysis focused specifically on PTSD, which was included in the broader scope of health and healthcare of the parent study. Using the larger scoping review database (N = 191), the following keywords were searched: PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder, trauma, and/or combat. Using this search, 143 articles were identified, and the lead author reviewed the full texts.

Study Selection

Studies were excluded after full-text review if they lacked relevant measurement specific to PTSD associations with criminal justice involvement (e.g., current or past arrest, incarceration, or criminal charges). Additionally, we excluded studies that did not report criminal justice outcomes of a control or comparison group of veterans without PTSD. A total of 13 studies met the initial inclusion criteria. Of those 13 studies, five were missing sufficient data to compute effect sizes. We requested the missing information from the lead author of each of these studies; two authors provided the requested information, two did not respond, and one no longer had access to the requested data.

Data Extraction

Based on prior reviews (Danan et al., 2017), 11 study characteristics were extracted independently by one author and reviewed by the senior author. These characteristics included (a) study design (e.g., observational–cohort, observational–case-control), (b) sample size, (c) population, (d) participant sex/gender, (e) participant age range, (f) racial/ethnic breakdown, (g) country, (h) era of military service, (i) type of research data used (e.g., administrative data, survey data), (j) method of ascertainment of PTSD, and (k) method of ascertainment of criminal justice involvement (see Table 1). Criminal justice involvement included self-report or administrative documentation of current or past probation, parole, crimial charge, arrest, or incarceration, and PTSD was measured as a dichotomous variable (yes or no) based on a diagnosis recorded in a clinical record, patient self-report of diagnosis, screening tool score indicating diagnosis, or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) diagnostic criteria from structured clinical interviews. Additionally, we extracted the necessary quantitative information required to compute effect sizes and assessed study quality using the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine’s (OCEBM) 2011 Levels of Evidence (OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group, 2011).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Studies Included in the Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

| First Author (Year) | Study design | Sample size | % Male | M age (years) (SD) | % White race | Country | Military service era | Data type | PTSD assessment | Justice involvement | Study quality scorea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black (2005) | Observational | > 1,000 | NR | NR | NR | USA | Persian Gulf | Survey | PCL | Incarceration | 4 |

| Bennett (2017) | Observational | 100–1,000 | 92.5 | 47.5 (13.5) | 73.0 | USA | NR | Survey | PCL-C | Violent charges | 4 |

| Elbogen (2012) | Observational | > 1,000 | 84.4 | NR | 70.3 | USA | Afghanistan and Iraq | Survey | DTS | Arrest | 4 |

| Erickson (2008) | Observational | > 1,000 | 100.0 | 57.5 (15.5) | 38.5 | USA | NR | Administrative data | Clinical diagnosis | Any incarceration | 4 |

| Macmanus (2013) | Observational | > 1,000 | 89.2 | 37.0 (6.4) | NR | United Kingdom | Afghanistan and Iraq | Administrative data; Survey | PCL-C | Violent offending | 3 |

| McFall (1991) | Observational | 100–1,000 | 100.0 | NR | 70.0 | USA | Vietnam | Survey | M-PTSD | Current parole or probation; arrest for assault | |

| Shaw (1987) | Observational, case control | < 100 | 100.0 | NR | 82.0 | USA | Vietnam | Survey | DSM III | Current incarceration | 3 |

| Sherman (2014) | Observational, semi-prospective | > 1,000 | 100.0 | NR | NR | Israel | NR | Administrative data; Survey | DSM IV | Criminal record (violent and non-violent offending) | 2 |

| Tsai (2013) | Observational | > 1,000 | 100.0 | 43.0 (8.0) | 47.6 | USA | NR | Survey | Clinical diagnosis | Charge for criminal offense | 3 |

| Tsai (2016) | Observational | > 1,000 | 100.0 | NR | 44.5 | USA | NR | Survey | PTSD self-report | Criminal history of major or severe crimes | 4 |

Note. NR = not reported; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; PCL = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist; PCL-C = PCL-Civilian version; DSM = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Study quality score was determined using the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine’s (OCEBM) 2011 Levels of Evidence and Grade Recommendation (OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group, 2011).

Data Analysis

The effect size of interest was the odds ratio (OR) of criminal justice involvement among veterans with PTSD compared to those without PTSD. We conducted a meta-analysis to generate pooled odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Heterogeneity among studies was estimated using Cochran’s Q and the I2 statistic, with an I2 value of 25% indicating low heterogeneity, 50% for moderate, and 75% for considerable heterogeneity. We used a restricted maximum likelihood random-effects model (REML), conducted in R (R Core Team, 2017), and RStudio (Version 1.1.447; RStudio Team, 2016), using the metafor package (Viechtbauer, 2010). A random-effects model was chosen due to the considerable heterogeneity observed among studies. We ran an additional model to estimate the magnitude of the association between combat exposure and criminal justice involvement.

To address the heterogeneity of effects sizes, we performed leave-one-out analyses, whereby each study was excluded once to examine its influence on the overall effect size estimate, as well as subgroup analyses that were based on the method of PTSD ascertainment and type of criminal justice involvement. We also performed a series of metaregressions to assess for the influence of moderator variables, including study quality, publication year, sample size, participant race, participant sex, and method of PTSD ascertainment. To identify the presence of publication bias, a funnel plot for the primary model was tested for asymmetry, using a regression test for funnel plot asymmetry and graphical assessment (Egger, Smith, Schneider, & Minder, 1997; Light & Pillemer, 1984; Viechtbauer, 2010).

Results

Study Characteristics

Ten studies were selected for final inclusion in the review and meta-analysis (Figure 1; (Bennett, Morris, Sexton, Bonar, & Chermack, 2017; Black et al., 2005; Elbogen et al., 2012; Erickson, Rosenheck, Trestman, Ford, & Desai, 2008; Macmanus et al., 2013; McFall, Mackay, & Donovan, 1991; Shaw, Churchill, Noyes, & Loeffelholz, 1987; Sherman et al., 2014; Tsai & Rosenheck, 2013, 2016). The included studies’ samples were drawn from populations of the United States (n = 8), United Kingdom (n = 1), and Israeli (n = 1) military veterans. Nine studies reported the sex composition of their sample, and all samples were predominately or exclusively male. Seven studies reported race, with the proportion of White veterans in the samples ranging from 38.5% to 82.0%. Two studies limited their sample to veterans of recent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, two studies included only veterans of the Vietnam era, and one study comprised only veterans of the Persian Gulf War era. Five studies did not report the service era. All studies had an observational design; sample sizes ranged from 61 to over 36,000 veterans. Study quality scores ranged from 2 to 4 (possible range: 1–5), with higher scores indicative of lower study quality and a higher risk of bias (OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group, 2011). Studies used survey data (n = 7), healthcare and criminal justice system administrative data (n = 1), or both (n = 2). The sociodemographic characteristics of each study’s sample and the methods used for the ascertainment of PTSD and criminal justice involvement are listed in Table 1.

Meta-Analysis

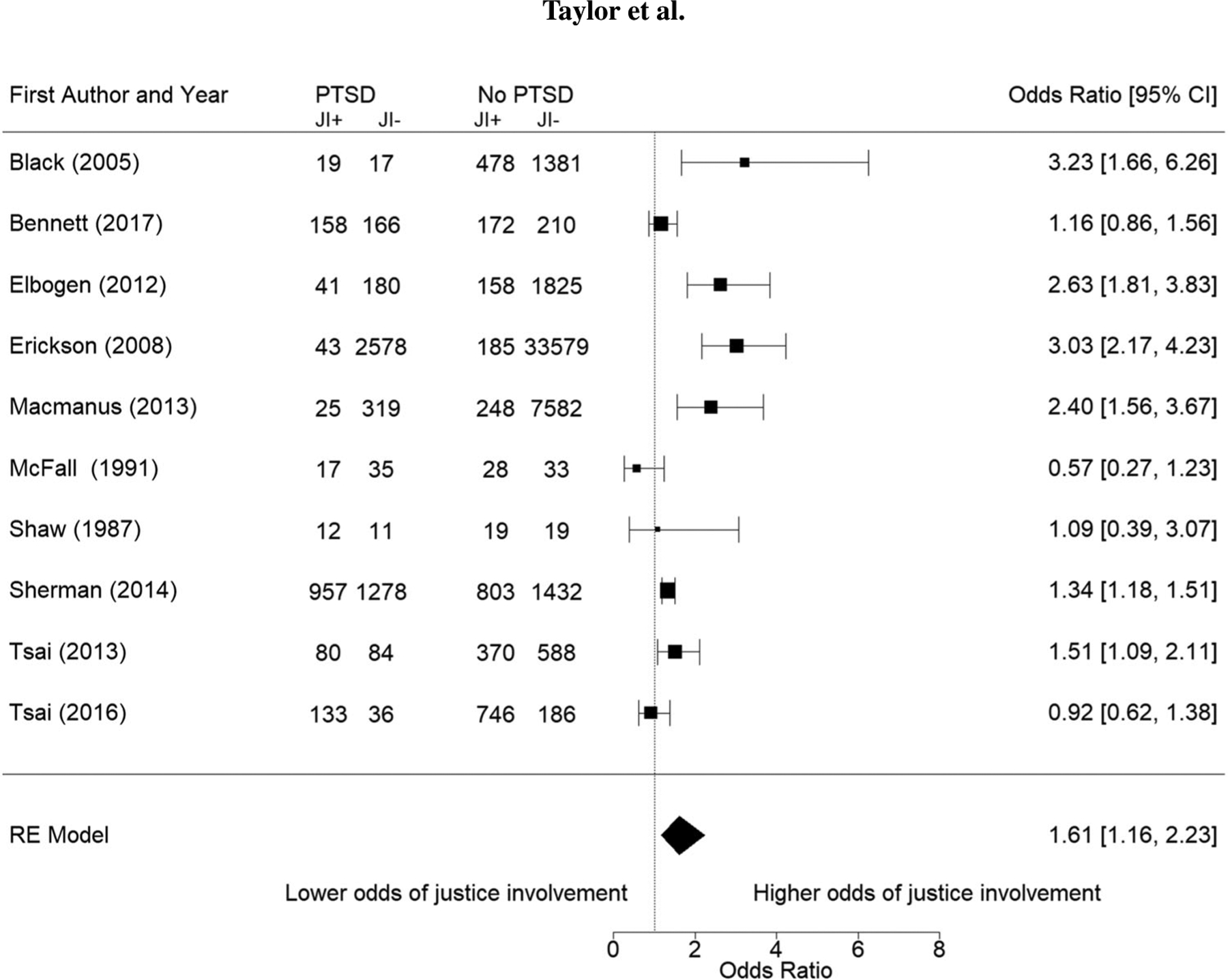

In our primary model, we examined the association between PTSD and all types of criminal justice involvement (n = 10). For each study, a person’s PTSD and justice-involved status were measured as dichotomous variables (i.e., yes or no). The odds of criminal justice involvement were significantly higher among veterans with PTSD compared to veterans without PTSD, OR = 1.61, 95% CI [1.16, 2.23], p = .002 (Figure 2). Additionally, we examined the association between combat exposure and criminal justice involvement and found no significant results. There was considerable heterogeneity in the model that examined any criminal justice involvement, Q = 53.77, p = .000, I2 = 88.2%, indicating high variation in study outcomes between studies. We assessed the presence of publication bias using a funnel plot and Egger’s test and graphical assessment for asymmetry, but we found none, p > .10 (Egger et al., 1997; Light & Pillemer, 1984; Viechtbauer, 2010). The results of the leave-one-out analyses resulted in significant odds ratios for criminal justice involvement among veterans with PTSD, ranging from 1.49 to 1.78, ps = .008–.001.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of odds ratios (ORs) for studies examining posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and any criminal justice involvement (JI) among military veterans. A considerable amount of heterogeneity was observed, Q = 53.77, p = .000, I2 = 88.2%, with no indication of publication bias (i.e., no funnel plot asymmetry, p > .10). RE = random effects.

Subgroup analyses were conducted to determine if subgroups based on method of PTSD ascertainment or type of criminal justice involvement yielded different results from the original model. The first subgroup model was used to examine the association between PTSD and a history of arrest for violence (n = 4). Similar to the full model, the odds of having an arrest for violence were 1.59 times higher among veterans with PTSD compared to veterans without PTSD, 95% CI [1.15, 2.19], p = .002. Heterogeneity in this model was moderate, Q 7.23, p = .065, I2 = 66.8%. We conducted a second subgroup model that examined only studies in which PTSD was measured using the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL; n = 3). We examined the PCL because it was the only method of PTSD ascertainment that was used in enough studies to perform such an analysis. We found that the odds of being justice-involved were 1.98 times higher among veterans with PTSD compared to veterans without PTSD, 95% CI [1.08, 3.63], p = .014. Heterogeneity was considerable, Q = 12.2, P = .002,I2 = 82.4%.

All models moderate-to-considerable heterogeneity; therefore, we conducted a series of metaregressions with our primary model to examine study quality, publication year, sample size, proportion of White veterans compared to all other races/ethnicities combined, and proportion of male veterans compared to female veterans. We conducted univariate metaregression models because of the small number of studies. In the single-predictor models, only sample size was found to significantly moderate the association between PTSD and criminal justice involvement, QM = 5.42, df = 1, p = .001, such that larger sample sizes yielded a larger association and accounted for some of the heterogeneity in our model, R2 = 66.7%.

Discussion

The results of the present meta-analysis indicate that PTSD is associated with higher odds of any criminal justice involvement, such as a history of incarceration or self-reported arrest history, and arrest for a violent crime. The same pattern of results was found in the subsample of studies that used the PCL to identify veterans with PTSD. Understanding the magnitude of the association between PTSD and justice involvement, as well as the strengths and limitations of the underlying evidence, allows clinicians and systems serving veterans with PTSD and criminal justice involvement to provide more tailored treatments that address the link between these factors.

Although the direction of a causal association cannot be determined by the results of this study, PTSD may be a factor that increases the risk of criminal justice involvement among veterans. A positive screen for PTSD was seen in 13.5% of veterans who served in Iraq or Afghanistan, and an individual’s response to trauma may play a role in their criminal behavior (Dursa, Reinhard, Barth, & Schneiderman, 2014; Owens, Wells, Pollock, Muscat, & Torres, 2008). The “general strain” theory, which asserts that the risk of criminal behavior is higher among individuals who have experienced traumatic events and subjectively report negative affect such as anger and irritability (Agnew, 1999), may partially explain the results of this study. Congruent with this theory, research indicates a higher likelihood of arrest among veterans with PTSD who report high levels of anger and/or irritability symptoms compared to those who do not report these symptoms (Elbogen et al., 2012).

Screening and early identification of PTSD allow for timely treatment, which may help attenuate any risk of justice involvement faced by veterans with PTSD. Congressional mandates exist within the United States and require PTSD screening by the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) and Department of Veterans Affairs (VA); however, there is a lack of consistency in the screening tools used, and little is known about how these screenings impact clinical care and coordination of care when someone is diagnosed with PTSD (Gates et al., 2012; Spoont et al., 2013; Lee, Warner, & Hoge, 2014). Implementing standardized procedures for intervention when veterans screen positive for probable PTSD may provide an opportunity for the DoD and VA to more efficiently connect veterans with either VA or community mental health support. Additionally, education for family members of military personnel and veterans about PTSD and how to recognize signs of PTSD may also help to identify people who would benefit from PTSD screening and early intervention. Screening for PTSD may also be necessary in criminal justice settings. Involvement in the criminal justice system may result in traumatic experiences that contribute to the development or worsening of PTSD. Over 30% of incarcerated individuals have experienced physical or sexual victimization while incarcerated (Wolff & Shi, 2010). Although criminal justice settings conduct general mental health screens, screening for PTSD is not universal in jails and prisons (Kubiak, Beeble, & Bybee, 2012). As trauma exposure occurs within criminal justice settings, correctional healthcare systems should consider screening for PTSD at both entry into and exit from a criminal justice setting as well as throughout the time a person is incarcerated.

Prioritizing PTSD treatment and trauma-informed care among clinicians, healthcare systems, and criminal justice systems that serve veterans is critical in attenuating the risk of criminal justice involvement. Mental illness is often exacerbated in the corrections system, and inadequate treatment of PTSD, whether the condition resulted from an experience prior to or during justice involvement, may perpetuate a cycle of incarceration (Crisanti & Frueh, 2011; Hagan et al., 2018; Kubiak, 2004; Mollard & Brage Hudson, 2016). Trauma-informed care may increase safety within jails and prisons among both individuals who are incarcerated and jail and prison staff (Miller & Najavits, 2012). In addition to the benefits of trauma-informed care, cognitive behavioral therapies for PTSD, such as cognitive processing therapy, have been shown to reduce overall PTSD symptoms and maladaptive behaviors and to decrease anger and aggression, which may help address factors related to criminal justice involvement and prevent first-time justice involvement (Feingold, Fox, & Galovski, 2018; Taft, Creech, & Kachadourian, 2012; Zalta, 2015).

In addition to trauma-informed care and PTSD treatment interventions, broader systems interventions may help support veterans with PTSD and justice involvement and break the cycle of incarceration. Veterans treatment courts are designed to divert veterans from jails and prisons when possible, and they provide specialized collaborative court interventions with wraparound services for veterans in the criminal justice system. Preliminary evidence suggests that behavioral health treatment during veterans treatment court participation has been associated with improvements in posttraumatic stress symptoms (Knudsen & Wingenfeld, 2016). Creating safe environments in which incarcerated veterans can disclose their traumatic experiences and receive treatment are critical but may be difficult in some prison or jail settings (Wainwright, McDonnell, Lennox, Shaw, & Senior, 2016). Another system-level intervention currently being tested in jails and prisons and may help to address this issue is veteran units within correctional settings. These units provide a safe space and support to veterans while also benefiting the institution and enabling easier care coordination between the corrections setting and outside organizations such as the VA and other veteran organizations (Edelman & Benos, 2018). The commonality of military service may create a therapeutic milieu and strong partnership between criminal justice settings and the VA (Tsai & Goggin, 2017) and make these settings more conducive to addressing PTSD by, for example, providing relevant psychoeducation or introducing evidence-based treatments for PTSD.

For this study, we conducted an extensive literature search and an in-depth analysis of relevant studies, but there were limitations. The sample size was small as few studies met inclusion criteria; however, a successful meta-analysis can be conducted with a small number of studies (Valentine, Pigott, & Rothstein, 2010). Three studies were excluded because they lacked the data needed to calculate effect sizes. Possibly, the inclusion of those studies would have influenced the results. Most of the studies included only a small number of women such that the results of this meta-analysis are most relevant to male veterans. Although we used metaregression models to examine some possible sources of heterogeneity, these models may lack robustness given the small number of studies examined. More consistency in outcome measures may have reduced the observed heterogeneity among studies. Studies lacked attention to specific PTSD symptoms, other mental health conditions (e.g., antisocial personality disorder), crime type, and timing of trauma and justice involvement, which may have accounted for some of the heterogeneity. The mechanism for how these may interplay with PTSD and the risk of criminal justice involvement should be examined as this may help to explain the link between PTSD and justice involvement and highlight treatment options to consider in the prevention of justice involvement and recidivism. Furthermore, we cannot make causal inferences or conclusions about any temporal association between PTSD and criminal justice involvement. Assessment of the timing of trauma exposure and involvement in the justice system is necessary to elucidate the directionality of the association between PTSD and criminal justice involvement.

The findings of this meta-analysis support an association between PTSD and criminal justice involvement among military veterans and highlight an important need for clinicians to address PTSD among military veterans to potentially reduce these veterans’ risk of criminal justice involvement. Trauma-informed care and trauma-specific cognitive behavioral interventions show promise as treatments to address the association between PTSD and criminal justice involvement among veterans. Early screening for PTSD in healthcare and criminal justice settings as well as interventions, such as veterans treatment courts, may help to connect veterans with PTSD to the treatments they need while breaking the link to criminal justice involvement. Although the results of this meta-analysis identified a link between PTSD and criminal justice involvement, it is unclear what factors may be driving this association. Research on premilitary risk factors for PTSD and criminal justice involvement may help identify areas for early intervention among active duty military and recently separated veterans. Grounding future research on PTSD and criminal justice involvement in theoretical frameworks, such as the general strain theory, may help clarify pathways between PTSD and criminal justice involvement.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Drs. Timko, Harris, and Finlay were supported by U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research & Development Career Development Awards (CDA 13-279, Research Career Scientist [RCS] 14-232, and Senior RCS 00-001, respectively). The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

References

- Agnew R (1992). Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminology, 30, 47–88. 10.1111/j.1745-9125.1992.tb01093.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi N, Hajsadeghi F, Mirshkarlo HB, Budoff M, Yehuda R, & Ebrahimi R (2011). Post-traumatic stress disorder, coronary atherosclerosis, and mortality. American Journal of Cardiology, 108, 29–33. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.02.340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RE, Geier TJ, & Cahill SP (2016). Epidemiological associations between posttraumatic stress disorder and incarceration in the National Survey of American Life. Criminal Behaviour & Mental Health, 26, 110–123. 10.1002/cbm.1951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backhaus A, Gholizadeh S, Godfrey KM, Pittman J, & Afari N (2016). The many wounds of war: The association of service-related and clinical characteristics with problems with the law in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 49, 205–213. 10.1016/j.ijlp.2016.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DC, Morris DH, Sexton MB, Bonar EE, & Chermack ST (2017). Associations between posttraumatic stress and legal charges among substance using veterans. Law and Human Behavior, 42, 135–144. 10.1037/lhb0000268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DW, Carney CP, Peloso PM, Woolson RF, Letuchy E, & Doebbeling BN (2005). Incarceration and veterans of the first Gulf War. Military Medicine, 170, 612–618. 10.7205/milmed.170.7.612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronson J, Carson EA, Noonan M, & Berzofsky M (2015). Veterans in prison and jail, 2011–12 (Report No.: NCJ 249144). Washington, DC: Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Crisanti AS, & Frueh BC (2011). Risk of trauma exposure among persons with mental illness in jails and prisons: What do we really know? Current Opinions in Psychiatry, 24, 431–435. 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328349bbb8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danan ER, Krebs EE, Ensrud K, Koeller E, MacDonald R, Velasquez T, … Wilt TJ (2017). An evidence map of the women veterans’ health research literature (2008–2015). Journal of General Internal Medicine, 32, 1359–1376. 10.1007/s11606-017-4152-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doran JM, Pietrzak RH, Hoff R, & Harpaz-Rotem I (2017). Psychotherapy utilization and retention in a national sample of vet erans with PTSD. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73, 1259–1279. 10.1002/jclp.22445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dursa EK, Reinhard MJ, Barth SK, & Schneiderman AI (2014). Prevalence of a positive screen for PTSD among OEF/OIF and OEF/OIF-era veterans in a large population-based cohort. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27, 542–549. 10.1002/jts.21956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelman B, & Benos D (2018). Barracks behind bars: In veteran-specific housing units, veterans help veterans help themselves. Retrieved from https://info.nicic.gov/jiv/sites/info.nicic.gov.jiv/files/Barracks-Behind-Bars-508.pdf

- Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, & Minder C (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ, 315(7109), 629–634. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Gabalawy R, Blaney C, Tsai J, Sumner JA, & Pietrzak RH (2018). Physical health conditions associated with full and subthreshold PTSD in U.S. military veterans: Results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 227, 849–853. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbogen EB, Johnson SC, Newton VM, Straits-Troster K, Vasterling JJ, Wagner HR, & Beckham JC (2012). Criminal justice involvement, trauma, and negative affect in Iraq and Afghanistan war era veterans. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80, 1097–1102. 10.1037/a0029967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson SK, Rosenheck RA, Trestman RL, Ford JD, & Desai RA (2008). Risk of incarceration between cohorts of veterans with and without mental illness discharged from inpatient units. Psychiatric Services, 59, 178–183. 10.1176/ps.2008.59.2.178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feingold ZR, Fox AB, & Galovski TE (2018). Effectiveness of evidence-based psychotherapy for posttraumatic distress within a jail diversion program. Psychological Services, 15, 409–418. http://doi.org.libproxy.uccs.edu/10.1037/ser0000194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay AK, Owens MD, Taylor E, Nash A, Capdarest-Arest N, Rosenthal J, … Timko C (2019). A scoping review of military veterans involved in the criminal justice and their health and healthcare. Health and Justice, 7, 1–18. 10.1186/s40352-019-0086-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates MA, Holowka DW, Vasterling JJ, Keane TM, Marx BP, & Rosen RC (2012). Posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans and military personnel: Epidemiology, screening, and case recognition. Psychological Services, 9, 361–382. 10.1037/a0027649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradus JL (2018). Epidemiology of PTSD. Retrieved from https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/treat/essentials/epidemiology.asp

- Greenberg GA, & Rosenheck RA (2012). Incarceration among male veterans: Relative risk of imprisonment and differences between veteran and non-veteran inmates. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 56, 646–667. 10.1177/0306624X11406091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan BO, Wang EA, Aminawung JA, Albizu-Garcia CE, Zaller N, Nyamu S, … Network TC (2018). History of solitary confinement is associated with post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms among individuals recently released from prison. Journal of Urban Health, 95, 141–148. 10.1007/s11524-017-0138-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvard Medical School. (2007). National Comorbidity Survey (NCS). Data Table 1: Lifetime prevalence DS-IV/WMH-CIDI disorders by sex and cohort. Retrieved from https://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/ftpdir/NCS-R_Lifetime_Prevalence_Estimates.pdf

- Knudsen K, & Wingenfeld S (2016). A specialized treatment court for veterans with trauma exposure: Implications for the field. Community Mental Health Journal, 52, 127–135. 10.1007/s10597-015-9845-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubiak SP (2004). The effects of PTSD on treatment adherence, drug relapse, and criminal recidivism in a sample of incarcerated men and women. Research on Social Work Practice, 14, 424–433. 10.1177/1049731504265837 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kubiak SP, Beeble M, & Bybee D (2012). Comparing the validity of the K6 when assessing depression, anxiety, and PTSD among male and female jail detainees. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 56, 1220–1238. 10.1177/0306624X11420106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DJ, Warner CH, & Hoge CW (2014). Advances and controversies in military posttraumatic stress disorder screening. Current Psychiatry Reports, 16(9). 10.1007/s11920-014-0467-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light RJ, & Pillemer DB (1984). Summing up: The science of reviewing research. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Macmanus D, Dean K, Jones M, Rona RJ, Greenberg N, Hull L, … Fear NT (2013). Violent offending by UK military personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan: A data linkage cohort study. Lancet, 381(9870), 907–917. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60354-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrone P, Knapp M, & Cawkill P (2003). Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the armed forces: Health economic considerations. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 16, 519–522. 10.1023/A:1025722930935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFall ME, Mackay PW, & Donovan DM (1991). Combat-related PTSD and psychosocial adjustment problems among substance abusing veterans. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 179, 33–38. 10.1097/00005053-199101000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller NA, & Najavits LM (2012). Creating trauma-informed correctional care: A balance of goals and environment. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 3, 17246. 10.3402/ejpt.v3i0.17246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, & Altman DG (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ, 339, b2535. 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollard E, & Brage Hudson D (2016). Nurse-led trauma-informed correctional care for women. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 52, 224–230. 10.1111/ppc.12122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novaco RW, & Chemtob CM (2015). Violence associated with combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder: The importance of anger. Psychological Trauma, 7, 485–492. 10.1037/tra0000067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outcalt SD, Kroenke K, Krebs EE, Chumbler NR, Wu J, Yu Z, & Bair MJ (2015). Chronic pain and comorbid mental health conditions: Independent associations of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression with pain, disability, and quality of life. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 38, 535–543. 10.1007/s10865-015-9628-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, & Elmagarmid A (2016). Rayyan: A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5, 210. 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens B, Wells J, Pollock J, Muscat B, & Torres S (2008). Gendered violence and safety: a contextual approach to improving security in women’s facilities (Document No. 225338). Washington, DC: National Institute of Corrections. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. (2011). The Oxford levels of evidence 2. Retrieved from https://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653

- Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, & Soares CB (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13, 141–146. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2017). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved from https://www.R-project.org [Google Scholar]

- RStudio Team. (2016). RStudio: Integrated development environment for R. Boston, MA: RStudio, Inc. Retrieved from http://www.rstudio.com [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DM, Churchill CM, Noyes R Jr., & Loeffelholz PL (1987). Criminal behavior and post-traumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 28, 403–411. 10.1016/0010-440x(87)90057-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman S, Fostick L, & Zohar J (2014). Comparison of criminal activity between Israeli veterans with and without PTSD. Depression & Anxiety, 31, 143–149. 10.1002/da.22161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoont M, Arbisi P, Fu S, Greer N, Kehle-Forbes S, Meis L, … Wilt TJ (2013). Screening for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in primary care: A systematic review. VA-ESP Project #09–009. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Creech SK, & Kachadourian L (2012). Assessment and treatment of posttraumatic anger and aggression: A review. Journal of Rehabilitation Research & Development, 49, 777—788. 10.1682/JRRD.2011.09.0156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J, & Goggin E (2017). Characteristics, needs, and experiences of U.S. veterans on a specialized prison unit. Evaluation and Program Planning, 64, 44–48. 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2017.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J, & Rosenheck RA (2013). Homeless veterans in supported housing: Exploring the impact of criminal history. Psychological Services, 10, 452–458. 10.1037/a0032775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J, & Rosenheck RA (2016). Psychosis, lack of job skills, and criminal history: Associations with employment in two samples of homeless men. Psychiatric Services, 67, 671–675. 10.1176/appi.ps.201500145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine JC, Pigott TD, & Rothstein HR (2010). How many studies do you need? A primer on statistical power for meta-analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 35, 215–247. 10.3102/1076998609346961 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Viechtbauer W (2010). Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of Statistical Software, 36, 48. 10.18637/jss.v036.i03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wainwright V, McDonnell S, Lennox C, Shaw J, & Senior J (2016). Treatment barriers and support for male ex-armed forces personnel in prison: Professional and service user perspectives. Qualitative Health Research, 27, 759–769. 10.1177/1049732316636846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton JL, Raines AM, Cuccurullo LJ, Vidaurri DN, Villarosa-Hurlocker MC, & Franklin CL (2018). The relationship between DSM-5 PTSD symptom clusters and alcohol misuse among military veterans. American Journal on Addictions, 27, 23–28. 10.1111/ajad.12658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisco BE, Marx BP, Wolf EJ, Miller MW, Southwick SM, & Pietrzak RH (2014). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the U.S. veteran population: Results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 75, 1338–1346. 10.4088/JCP.14m09328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff N, & Shi J (2010). Trauma and incarcerated persons. In Scott CL (Ed.), Handbook of correctional mental health (2nd ed., pp. 277–320). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Xue C, Ge Y, Tang B, Liu Y, Kang P, Wang M, & Zhang L (2015). A meta-analysis of risk factors for combat-related PTSD among military personnel and veterans. PLoS One, 10(3), e0120270. 10.1371/journal.pone.0120270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalta AK (2015). Psychological mechanisms of effective cognitive–behavioral treatments for PTSD. Current Psychiatry Reports, 17, 23. 10.1007/s11920-015-0560-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.