Abstract

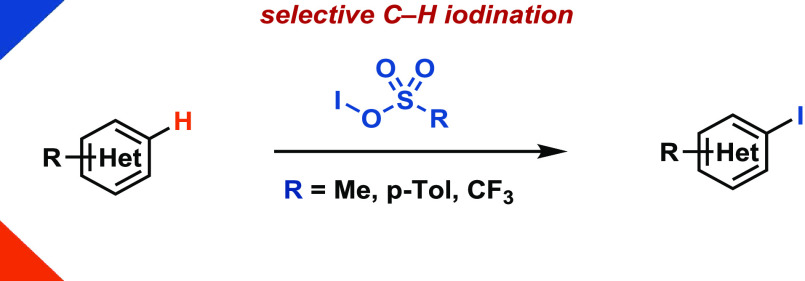

Iodoarenes are versatile intermediates and common synthetic targets in organic synthesis. Here, we present a strategy for selective C–H iodination of (hetero)arenes with a broad functional group tolerance. We demonstrate the utility and differentiation to other iodination methods of supposed sulfonyl hypoiodites for a set of carboarenes and heteroarenes.

Aromatic C–I bonds are among the most versatile synthetic handles in organic synthesis1,2 because they exhibit desirable reactivity, often superior to the other C–halogen bonds, such as in cross coupling reactions,3−7 when transformed into λ3-iodanes,8 for lithium-halogen exchange,9 or for the generation of aryl radicals.10,11 Electrophilic aromatic substitution (SEAr) reactions are among the most widely used synthetic methods to install C–I bonds but typically afford mixtures of isomers.12 Iodination of arenes is generally more difficult to achieve than chlorination and bromination due to the limited availability of electrophilic iodination reagents that are comparable in reactivity to their chlorine and bromine counterparts. Molecular iodine (I2) and other electrophilic iodinating reagents such as N-iodosuccinimde (NIS),13 and 1,3-diiodo-5,5-dimethylhydantoin (DIH)14 are generally not sufficiently reactive to react with electron-deficient arenes and many heterocycles and, if so, commonly give mixtures of constitutional isomers.15 Herein, we demonstrate the discovery of a novel regioselective (hetero)arene iodination reaction by a mixture of bis(methanesulfonyl) peroxide (1) and iodide (Figure 1). We presumed the formation of previously unexplored sulfonyl-based hypoiodite as an electrophilic iodination reagent and subsequently designed its independent in situ formation by the synthetically more convenient addition of silver mesylate to molecular iodine to result in a previously unappreciated, practical iodination reaction that expands the scope of contemporary electrophilic aromatic iodination chemistry.

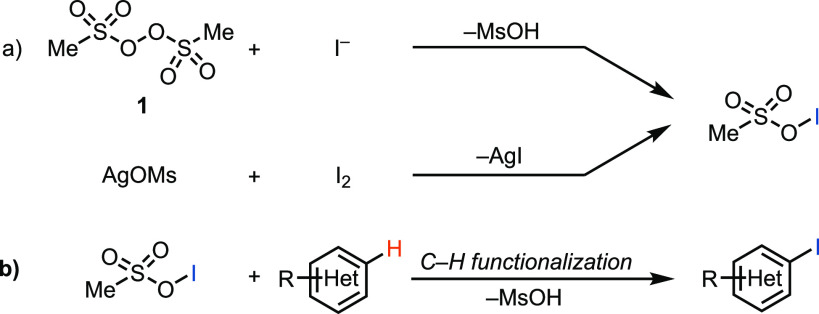

Figure 1.

(a) Two different methods to obtain hypoiodites. (b) Aromatic C–H iodination of (hetero)arenes via sulfonyl hypoiodites.

Notwithstanding rare enzyme-catalyzed aromatic C–H iodination,16,17 many of the reported arene iodination methods often require strongly acidic and harsh reaction conditions such as the use of 95% H2SO4 as a solvent or reaction temperatures in excess of 120 °C, which limits the functional group tolerance and overall utility of iodination chemistry.18−21 Activation of molecular iodine for aromatic iodination, by modifying its electrophilicity, has been achieved by using oxidizing reagents such as Pb(OAc)4, or CrO3 dissolved in a mixture of acetic acid with acetic anhydride,22 which can result in overiodination of electron-rich arenes. Olah and co-workers reported a C–H iodination of deactivated arenes with NIS in neat TfOH23 and BF3–H2O.24 In 2018, the Crousse group reported halogenation of (hetero)arenes in HFIP that is limited to electron-rich substrates.25 Furthermore, the Nagib group reported the site-selective incorporation of various anions including Cl–, Br–, OMs–, OTs–, and OTf– to heteroarenes via an iodane intermediate; however, the incorporation of iodide was not shown.26 Moreover, the iodination of simple arenes such as toluene and benzene has been reported by using AgOTf/I2, Ag2SO4/I2, and AgNO2/I2.27−31 In 2011, the Lehmler group reported the iodination of chlorinated arenes using Ag2SO4/I2, AgSbF6/I2, AgBF4/I2, and AgPF6/I2, which introduce the iodine in the para position to the Cl-substituent.32 In addition, significant progress has been made to enhance the reactivity of NIS by using Brønsted and Lewis acids as well as Lewis base catalysts; however, such methods have only been shown to perform on relatively simple arenes, such as anisole.33 Iodination of more complex small molecules has not been described with any of the methods described above. Hence, there is still a demand for developing mild and effective methods for selective C–H iodination of complex arenes. Herein, we methodically explore the regioselective aromatic C–H iodination of complex (hetero)arenes, with a special emphasis on the use of Ag(I) sulfonates. Sulfonates could react with iodine to sulfonyl hypoiodites that are not accessible in reactions with other silver salts exhibiting counterions, which had been evaluated before, such as BF4 or SbF6. The reactivity profile of the putative sulfonyl hypoiodites is adaptable through the appropriate choice of the silver salt and enlarges the currently available scope for (hetero)aromatic iodination chemistry.

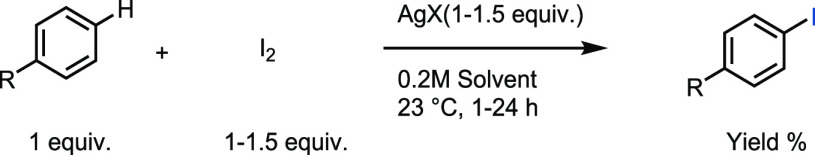

Based on our reaction chemistry developed with 1,34 we have discovered a productive, high-yielding iodination reaction in the presence of iodide and 1 (Table 1). Because 1 is explosive, we attempted to reproduce the observed reactivity with reagents that are more convenient and safer. We assumed the formation of methanesulfonylhypoiodite as the reactive electrophilic iodinating reagent that formed in situ upon mixing 1 and iodide and attempted to intercept it independently through the reaction of molecular iodine with silver mesylate. We successfully observed a similar reactivity, which is superior when compared to conventional iodination reagents and reactions (Table 1). Because the putative sulfonyl hypoiodites are prepared in situ in solution, this reaction setup does not share the same safety concerns associated with the explosiveness of bis(methansulfonyl) peroxide that was used as an isolated solid.

Table 1. Comparison of Sulfonyl Hypoiodites with Other Known Electrophilic Iodinating Methodsa.

| comparison with electrophilic iodinating methods | yieldb |

|---|---|

| (MsO)2 (1, 1.8 equiv) + TBAI (2.0 equiv) in 0.2 M MeCN | 84% |

| I2 (1.3 equiv) + AgOMs (1.3 equiv) in 0.2 M MeCN | 90% |

| I2 (1 equiv) + AgOTf (1 equiv) in 0.2 M DCM | 18% |

| NIS (1 equiv) in 0.2 M HFIP | 54% |

| NIS (10 equiv) in 0.2 M TfOH | 0% |

| Ph2S2 (5 mol %) + DIH (0.75 equiv) in 0.3 M MeCN | 29% |

| I2 (1 equiv) + AgPF6 (1 equiv) in 0.2 M DCM | 16% |

Reactions were carried out on a 0.1 mmol scale.

Yields determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy with dibromomethane as an internal standard.

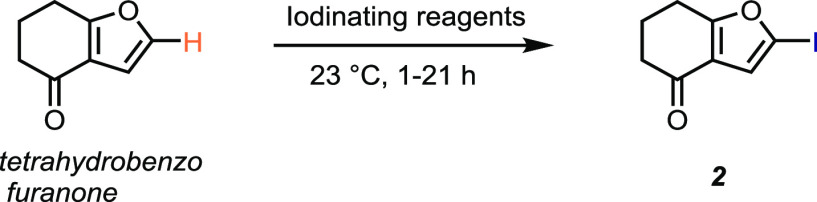

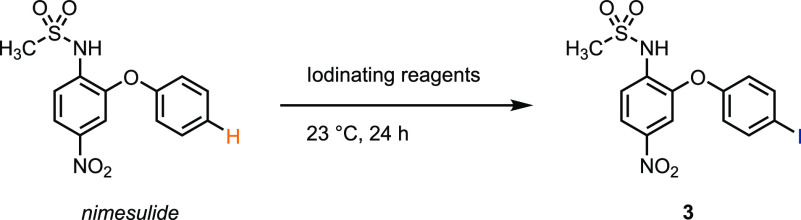

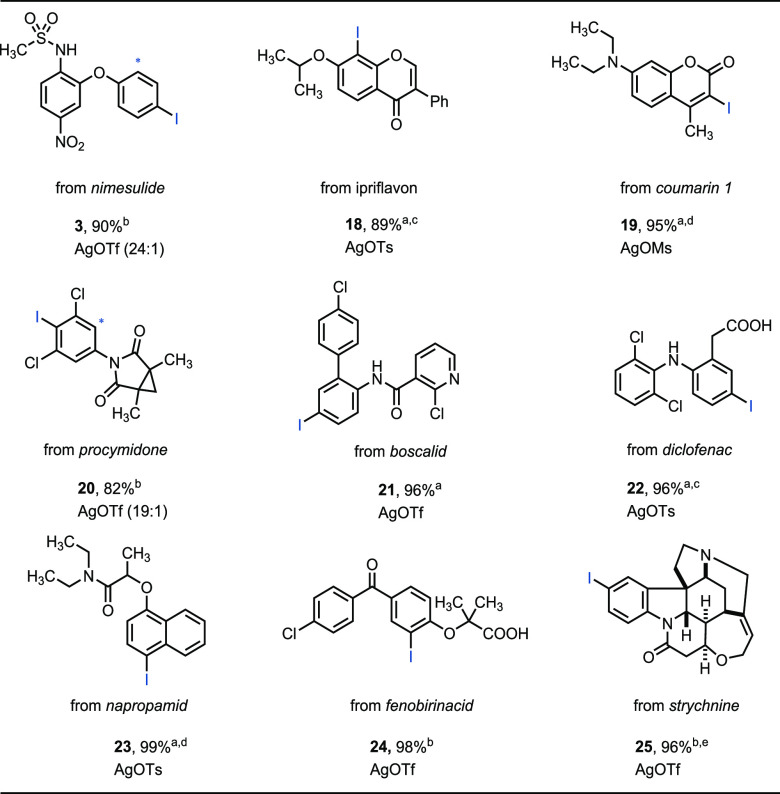

Although NIS is a practical and convenient reagent for the iodination of simple, electron-rich (hetero)arenes, its utility is severely limited for less electron-rich substrates. While NIS can furnish the same iodinated product 2 (Table 1), albeit in a substantially lower yield, for more complex, functionalized, or electron-poor substrates, it often fails, as shown in Table 2, and for a selection of a dozen compounds in the Supporting Information, Table S1.

Table 2. C–H Iodination of Nimesulidea.

| electrophilic C–H iodination method | yieldb |

|---|---|

| I2 (2.0 equiv) + AgOMs (2.0 equiv) in 0.2 M MeCN | 92%c |

| NIS (1 equiv) in 0.2 M HFIP | <1% |

Reactions were carried out on a 0.1 mmol scale.

Yields determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy with dibromomethane as an internal standard.

Isolated yield.

The simple reaction setup of mixing a silver salt that could form a putative iodine–oxygen bond potentially enables the in situ generation of a variety of hypoiodites that could, in the best case, be adapted to the required reactivity for efficient iodination of a given arene. In other words, tuning the reactivity of the presumed hypoiodite would allow for an appropriate electrophilicity for any given (hetero)arene.

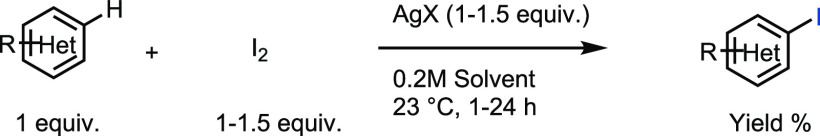

After a brief evaluation of simple arenes (Table 3), we focused our attention on the C–H iodination of various heteroarenes because N-containing heterocycles represent an important class of compounds in medicinal chemistry.35 A variety of functional groups such as electron-rich pyridines, carboxylic acids, esters, amines, sulfonamides, and phthalimides are well tolerated. If acid-sensitive functional groups are present, the addition of Li2CO3 as a base to neutralize the in situ formed acid byproduct results in productive iodination. The iodination reaction reported here could be extended to electron-rich heteroarenes such as N-methylpyrrole (10) and 2,6–dimethoxypyridine (11), with the best results obtained when using silver acetate. Compounds containing ketones are generally challenging for iodination; however, ketone 2 was obtained in 80% isolated yield with less than 5% α-iodination byproduct. Other 5-membered heteroarenes such as thiazole (14) and pyrroles (17) afforded the highest yields with silver tosylate.

Table 3. C–H Iodination of Various (Hetero)arenesg.

Reaction was conducted in 0.2 M MeCN.

Reaction was conducted in 0.2 M DCM.

I2 (1.3 equiv) and AgX (1.3 equiv).

Li2CO3 (1.0 equiv) was used.

I2 (1.2 equiv) and AgOTf (1.2 equiv).

I2 (1.5 equiv) and AgOTs (1.5 equiv).

General conditions except where otherwise noted: arene (0.2 mmol), AgX (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv), I2 (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv), 23 °C.

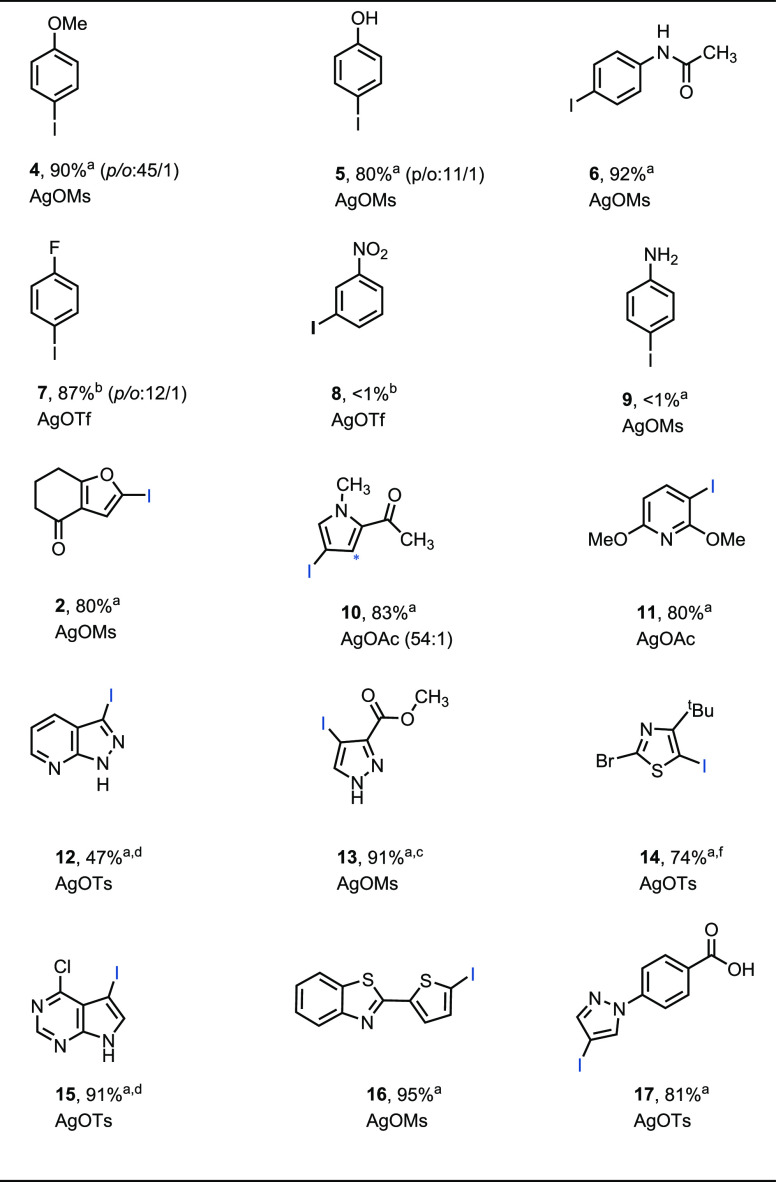

As can be seen in Table 4, the scope of the new iodination reaction includes a range of small-molecule pharmaceutical carboarenes. The reaction condition proved to be compatible with structurally complex arenes, such as nimesulide (3), procymidone (20), boscalid (21), and strychnine (25). Notably, no competing addition of iodine to double bonds was observed for arenes 18, 19, and 25. The method often affords a high yield and high positional selectivity. A detailed study of the hypothesis that the magnitude of the selectivity can be rationalized by a charge transfer complex between hypoiodite and arene as we observed in the related mesyloxylation reaction34 was prevented by in situ formation of the reactive intermediate. Scale-up to the gram scale was established for iodination of coumarin1 with silver methanesufonate to afford product 19 in 91% yield. Electron-withdrawing arenes gave low yields for the corresponding iodinated products.

Table 4. C–H Iodination of Small-molecule Drugsg.

Reaction was conducted in 0.2 M MeCN.

Reaction was conducted in 0.2 M DCM.

I2 (1.3 equiv) and AgX (1.3 equiv).

Li2CO3 (1.0 equiv) was used.

I2 (1.2 equiv) and AgOTf (1.2 equiv).

I2 (1.5 equiv) and AgOTs (1.5 equiv).

General conditions except where otherwise noted: arene (0.2 mmol), AgX (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv), I2 (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv), 23 °C.

We observed chemoselective iodination for sp2 C–H functionalization with no benzylic or α-carbonyl oxidation observed, an advantage when compared to the combination of iodine and other oxidants.36 The reaction is insensitive to oxygen or traces of water and thus can be carried out under an ambient atmosphere. For most substrates, clean conversion of the starting material to the product was observed, which renders purification straightforward. When compared to conventional iodinating reagents such as NIS, the reaction conditions shown here typically afforded substantially higher yields, higher selectivity, and no overiodination (see Table S1 in the Supporting Information for a comparison).

In summary, we have presented a simple C–H iodination of various carboarenes and heteroarenes via putative sulfonyl hypoiodites that has not been appreciated before and extends the substrate scope of iodination chemistry. The operational ease, scalability, broad functional group tolerance, and substrate scope make this protocol suitable for both academic and industrial settings.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Farés, M. Leutzsch, and M. Kochius (MPI KOFO) for assistance with NMR structural assignments, and S. Marcus and D. Kampen (MPI KOFO) for mass spectroscopy analysis.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.orglett.1c01530.

Detailed experimental procedures and spectroscopic characterization (PDF)

Author Contributions

L.T. developed the C–H iodination reaction protocol. J.B. and J.L. helped in the synthesis of the peroxide and the mechanism study. L.T. and T.R. wrote the manuscript. T.R. directed the project.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Abe H.; Kikuchi S.; Hayakawa K.; Iida T.; Nagahashi N.; Maeda K.; Sakamoto J.; Matsumoto N.; Miura T.; Matsumura K.; Seki N.; Inaba T.; Kawasaki H.; Yamaguchi T.; Kakefuda R.; Nanayama T.; Kurachi H.; Hori Y.; Yoshida T.; Kakegawa J.; Watanabe Y.; Gilmartin A. G.; Richter M. C.; Moss K. G.; Laquerre S. G. Discovery of a highly potent and selective MEK inhibitor: GSK1120212 (JTP-74057 DMSO solvate). ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 2, 320–324. 10.1021/ml200004g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble G. W. Natural organohalogens: A new frontier for medicinal agents?. J. Chem. Educ. 2004, 81, 1441. 10.1021/ed081p1441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magano J.; Dunetz J. R. Large-scale applications of transition metal-catalyzed couplings for the synthesis of pharmaceuticals. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 2177–2250. 10.1021/cr100346g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weix D. J. Methods and mechanisms for cross-electrophile coupling of Csp2 halides with alkyl electrophiles. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 1767–1775. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadunce N. T.; Reisman S. E. Nickel-catalyzed asymmetric reductive cross-coupling between heteroaryl iodides and α-chloronitriles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 10480–10483. 10.1021/jacs.5b06466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaou K. C.; Bulger P. G.; Sarlah D. Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions in total synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 4442–4444. 10.1002/anie.200500368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyaura N.; Suzuki A. Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of organoboron compounds. Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 2457–2483. 10.1021/cr00039a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura A.; Zhdankin V. V. Advances in synthetic applications of hypervalent iodine compounds. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 3328–3435. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappoport Z.; Marek I.. The chemistry of organolithium compounds; Wiley: Chichester, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kvasovs N.; Gevorgyan V. Contemporary methods for generation of aryl radicals. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 2244–2259. 10.1039/D0CS00589D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantin T.; Juliá F.; Sheikh N. S.; Leonori D. A case of chain propagation: α-aminoalkyl radicals as initiators for aryl radical chemistry. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 12822–12828. 10.1039/D0SC04387G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor R.Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution; John Wiley & Sons, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- a Bergström M.; Suresh G.; Naidu V. R.; Unelius C. R. N-Iodosuccinimide (NIS) in direct aromatic iodination. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 2017, 3234–3239. 10.1002/ejoc.201700173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Tanemura K.; Suzuki T.; Nishida Y.; Satsumabayashi K.; Horaguchi T. Halogenation of aromatic compounds by N-chloro-, N-bromo-, and N-iodosuccinimide. Chem. Lett. 2003, 32, 932–933. 10.1246/cl.2003.932. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iida K.; Ishida S.; Watanabe T.; Arai T. Disulfide-catalyzed iodination of electron-rich aromatic compounds. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 7411–7417. 10.1021/acs.joc.9b00769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly N. C.; Barik S. K.; Dutta S. Ecofriendly iodination of activated aromatics and coumarins using potassium iodide and ammonium peroxodisulfate. Synthesis 2010, 2010, 1467–1472. 10.1055/s-0029-1218698. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sdahl M.; Conrad J.; Braunberger C.; Beifuss U. Efficient and sustainable laccase-catalyzed iodination of p-substituted phenols using KI as iodine source and aerial O2 as oxidant. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 19549–19559. 10.1039/C9RA02541C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huwiler M.; Bürgi U.; Kohler H. Mechanism of enzymatic and non-enzymatic tyrosine iodination inhibition by excess hydrogen peroxide and/or iodide. Eur. J. Biochem. 1985, 147, 469–476. 10.1111/j.0014-2956.1985.00469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barluenga J.; Gonzalez J. M.; Garcia-Martin M. A.; Campos P. J.; Asensio G. Acid-mediated reaction of bis(pyridine)iodonium(I) tetrafluoroborate with aromatic compounds. A selective and general iodination method. J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 2058–2060. 10.1021/jo00060a020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kraszkiewicz L.; Sosnowski M.; Skulski L. Easy, inexpensive and effective oxidative iodination of deactivated arenes in sulfuric acid. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 9113–9119. 10.1016/j.tet.2004.07.095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kraszkiewicz L.; Sosnowski M.; Skulski L. Oxidative iodination of deactivated arenes in concentrated sulfuric acid with I2/NaIO4 and KI/NaIO4 iodinating systems. Synthesis 2006, 1195–1199. 10.1055/s-2006-926374. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song S.; Sun X.; Li X.; Yuan Y.; Jiao N. Efficient and practical oxidative bromination and iodination of arenes and heteroarenes with DMSO and hydrogen halide: A mild protocol for late-Stage functionalization. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 2886–2889. 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piotr L.; Lech S. The direct iodination of arenes with chromium(VI) oxide as the oxidant. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1997, 70, 1665–1669. 10.1246/bcsj.70.1665. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olah G. A.; Qi W.; Sandford G.; Surya Prakash G. K. Iodination of deactivated aromatics with N-iodosuccinimide in trifluoromethanesulfonic acid (NIS-CF3SO3H) via in situ generated superelectrophilic iodine(I) trifluoromethanesulfonate. J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 3194–3195. 10.1021/jo00063a052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash G. K. S.; Mathew T.; Hoole D.; Esteves P. M.; Wang Q.; Rasul G.; Olah G. A. N-Halosuccinimide/BF3–H2O, Efficient electrophilic halogenating systems for aromatics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 15770–15776. 10.1021/ja0465247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang R. J.; Milcent T.; Crousse B. Regioselective halogenation of arenes and heterocycles in hexafluoroisopropanol. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 930–938. 10.1021/acs.joc.7b02920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fosu S. C.; Hambira C. M.; Chen A. D.; Fuchs J. R.; Nagib D. A. Site-selective C–H functionalization of (hetero)Arenes via transient, non-symmetric iodanes. Chem. 2019, 5, 417–428. 10.1016/j.chempr.2018.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulholland G. K.; Zheng Q. H. A direct iodination method with iodine and silver triflate for the synthesis of SPECT and PET imaging agent precursors. Synth. Commun. 2001, 31, 3059–3068. 10.1081/SCC-100105877. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sy W. W.; Lodge B. A.; By A. W. Aromatic iodination with iodine and silver sulfate. Synth. Commun. 1990, 20, 877–880. 10.1080/00397919008052334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Yusubov M. S.; Tveryakova E. N.; Krasnokutskaya E. A.; Perederyna I. A.; Zhdankin V. V. Solvent-free iodination of arenes using iodine–silver nitrate combination. Synth. Commun. 2007, 37, 1259–1265. 10.1080/00397910701216039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Sy W. W.; Lodge B. A. Iodination of alkylbenzenes with iodine and silver nitrite. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989, 30, 3769–3772. 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)80650-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giri R.; Yu J. Q.. Iodine monoacetate. In e-EROS, encyclopedia of reagents for organic synthesis; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Henne A. L.; Zimmer W. F. Positive halogens from trifluoroacetyl hypohalites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951, 73, 1362–1363. 10.1021/ja01147a514. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi S. N.; Vyas S. M.; Wu H.; Duffel M. W.; Parkin S.; Lehmler H.-J. Regioselective iodination of chlorinated aromatic compounds using silver salts. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 7461–7469. 10.1016/j.tet.2011.07.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Nishii Y.; Ikeda M.; Hayashi Y.; Kawauchi S.; Miura M. Triptycenyl Sulfide: A practical and active catalyst for electrophilic aromatic halogenation using N-halosuccinimides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 1621–1629. 10.1021/jacs.9b12672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Racys D. T.; Sharif S. A. I.; Pimlott S. L.; Sutherland A. Silver(I)-catalyzed iodination of arenes: tuning the lewis acidity of N-iodosuccinimide activation. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 772–780. 10.1021/acs.joc.5b02761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Börgel J.; Tanwar L.; Berger F.; Ritter T. Late-stage aromatic C–H oxygenation J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 16026. 10.1021/jacs.8b09208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Tanwar L.; Börgel J.; Ritter T. Synthesis of benzylic alcohols by C–H oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 17983–17988. 10.1021/jacs.9b09496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaku E.; Smith D. T.; Njardarson J. T. Analysis of the structural diversity, substitution patterns, and frequency of nitrogen heterocycles among U.S. FDA approved pharmaceuticals. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 10257–10274. 10.1021/jm501100b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vekariya R. H.; Balar C. R.; Sharma V. S.; Prajapati N. P.; Vekariya M. K.; Sharma A. S. Preparation of α-Iodocarbonyl compounds: An overall development. Chemistry Select 2018, 3, 9189–9203. 10.1002/slct.201801778. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.