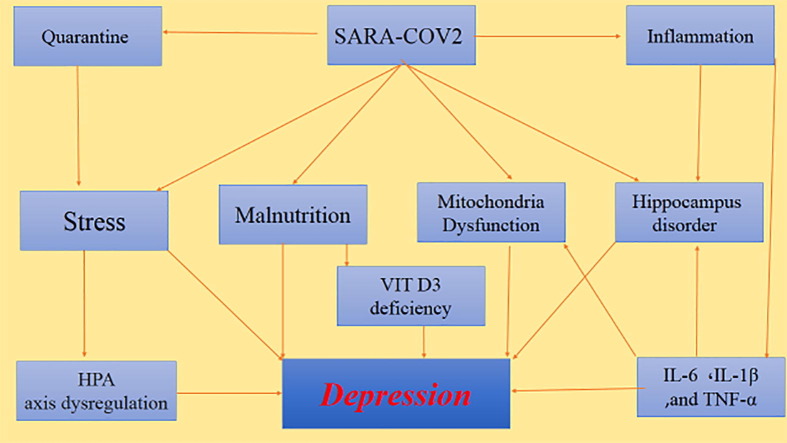

Graphical abstract

Keywords: COVID-19, Depression, Stress

Abstract

The new coronavirus (COVID-19) has emerged now in the world as a pandemic. The SARS-CoV-2 infection causes variant common symptoms, such as dry cough, tiredness, dyspnea, fever, myalgia, chills, headache, chest pain, and conjunctivitis. Different organs may be affected by COVID-19, such as the respiratory system, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, and CNS. However, the information about the COVID-19 infection in the CNS is insufficient. We do know that the virus can enter the central nervous system (CNS) via different routes, causing symptoms such as dizziness, headache, seizures, loss of consciousness, and depression. Depression is the most common disorder among all neurological symptoms following COVID-19 infection, although the mechanism of COVID-19-induced depression is not yet clear.

The aim of the present study is to investigate the probable mechanisms of COVID-19-induced depression.

The reasons for depression in infected patients may be due to social and pathological factors including social quarantine, economic problems, stress, changes in the HPA axis, inflammation due to the entry of proinflammatory cytokines into the CNS, production of inflammatory cytokines by microglia, mitochondrial disorders, damage to the hippocampus, and malnutrition.

By evaluating different factors involved in COVID-19-induced depression, we have concluded that depression can be minimized by controlling stress, preventing the cytokine storm with appropriate anti-inflammatory drugs, and proper nutrition.

1. Introduction

Coronaviruses are a large family of viruses, including SARS, MERS, and COVID. Seven types of coronavirus that can transmit to humans have been identified. The latest (SARS-CoV-2) started in Wuhan, China in December 2019, and spread worldwide very rapidly. Although most COVID-19 patients initially have mild symptoms similar to the common cold, more severe symptoms appear a few days after infection [1], [2], [3]. These symptoms include dry cough, tiredness, dyspnea, fever, chills, headache, chest pain, conjunctivitis, dizziness, sore throat, myalgia, and loss of sense of smell [4], [5]. The SARS-CoV-2 infection can be associated with different consequences in the CNS [6]. Nervous manifestations include seizures, stroke, Guillain-Barre syndrome, memory impairment, PTSD, delirium, insomnia, sleep disorder, anxiety, and depression [7], [8].

Because more COVID-19 infected patients have flu-like symptoms, more attention has been paid to the respiratory complications, and the adverse consequences in the central nervous system such as seizure and depression have been mostly neglected [9]. The peripheral neural pathways are the most important entrance routes for the virus to the CNS [10], [11]. The unique anatomy of the olfactory nerves converts this pathway into a channel between the nasal epithelium and the CNS [12].

It has been reported that some infected patients show nonspecific neurological symptoms such as delirium, headache, and loss of consciousness without any signs of respiratory failure [13]. The entry of the virus into the CNS is followed by inflammation. In some conditions, diseases such as MS, seizures, and depression can develop in these patients [11], [13], [14].

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is a common, multifactorial heterogeneous, and chronic complex that affects approximately 350 million people worldwide [14]. MDD causes emotional, behavioral, and physical problems. Common symptoms of depression include boredom, inability to enjoy, feelings of hopelessness, social isolation, and worthlessness. Problems in concentration, inability to make decisions, sleep disorders (insomnia or excessive sleep), anorexia, loss of libido, and various physical aches are more symptoms of major depression [15], [16], [17]. In patients with COVID-19, most depression symptoms can be clearly seen during the illness and after a partial recovery [18], [19].

Anxiety and depression induced by COVID-19 infection can worsen the prognosis of the disease and have a negative effect on the immune system [20].

Previous studies have shown the prevalence of depression in COVID-19 infected patients is 45%, anxiety 47%, and sleeping disturbances 34%. No significant difference was detected between genders [21].

The most important reasons for developing depression in COVID-19 infected patients can be divided into social and pathological factors.

1.1. Psychological mechanisms involved in COVID-19 induced depression

1.1.1. Quarantine

The policy of quarantine leads to loneliness and social isolation, and these two are causes of stress, anxiety, and other psychological complications [22], [23], [24]. In experimental animal models, social isolation stress (SIS) alters activity, social behavior, neurochemical function, and the neuroendocrine system. This may cause physiological and anatomical changes in animals. Animals with SIS have been shown to exhibit symptoms of psychiatric disorders such as anxiety, depression, and memory loss. Social isolation stress also activates the hypothalamic–pituitaryadrenal (HPA) axis, which ultimately releases cortisol and catecholamines. In general, SIS is accepted as an experimental method to induce depression in animals [25].

Considering the potential negative impact of quarantine on depression, it is a very important factor in maintaining public health. Receiving support from family, friends, and medical staff can be a major palliative factor that helps patients to deal with stress and depression induced by quarantine [26], [27].

1.1.2. Stress

Studies have shown that stress that occurs during a pandemic may play a major role in the development of depression in Covid-19 patients. Stress may be due to psychosocial factors such as the fear of contact possibility with infected people, quarantine, lack of access to tests and medical care, receiving conflicting messages and even constant media coverage of epidemic reports or instructions about public health practices, increased workload, economic problems, and lack of available resources (e.g., masks and personal protective equipment) [27], [28].

Elevated blood cortisol concentrations and abnormalities in the Hypothalamus-hypophysis axis (HPA axis) following virus infection are responsible for depression following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Although high cortisol levels may have short-term beneficial effects, enabling the brain to overcome stress, chronically elevated cortisol levels can affect voltage-gated ion channels and increase calcium uptake. Chronic stress is the main factor involved in the development of depression caused by COVID-19. Reducing stress can prevent or reduce depressive symptoms [29], [30], [31].

1.2. Central mechanisms involved in COVID-19 induced depression

1.2.1. COVID-19, inflammation and depression

The entry of COVID-19 into the CNS causes uncontrolled activation of microglia, which leads to the release of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1B), nitric oxide, prostaglandin E2, and free radicals in the brain. In the case of a severe immune response (cytokine storm), destructive damage in the blood–brain barrier occurs, leading more inflammatory factors to enter the CNS (31, 32) and release even more cytokines from the microglia into the CNS [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37].

Among pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-6 (an important member of the cytokine storm) increases during SARS-CoV-2 infection and plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of depression in COVID-19 patients. The concentrations of IL-6 is probably directly related to the severity of depression in infected patients [38], [39].

Inflammation induced by COVID-19 can also increase the production of free radicals and decrease the total level of glutathione, which has been previously detected in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) (42). Pro-inflammatory cytokines also play an essential role in regulating the response to stress and neurogenesis in the CNS as they destroy the neurotrophic support, alter glutamate release, and increase oxidative stress. Finally, these cytokines cause cytotoxicity, neuronal loss, decreased neurogenesis, and neurological complications in depression [41], [42].

1.2.2. COVID-19, mitochondria disorder and depression

The mitochondria are damaged by COVID-19 either directly by the hijack of the organelle for transcription of the virus genome or indirectly by increasing pro-inflammatory cytokines and ROS production [40], [41]. In the direct way, COVID-19 either induced the localization of its RNA transcripts or RNA itself in the host cell’s mitochondria, manipulating mitochondrial function [41].

In patients with COVID-19 inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6, inhibit mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and ATP production and increase ROS production, which may cause impaired mitochondrial function and dynamics eventually leading to apoptosis and cell death .[40]

Mitochondria are very sensitive to oxidative stress. Increased inflammation in the brain as a result of COVID-19 leads to increased oxidative stress and damage to mitochondria [42].

It is well established that mitochondria have a pivotal role in ATP production, calcium hemostasis, the balance of oxidative factors, regulation of apoptosis, and neurotransmitter release in the axonal terminal. Mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to the pathogenesis of many diseases, including depression [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48]. So, the dysfunction of mitochondria caused by COVID-19 may be a mechanism of COVID-19 induced depression.

Inflammatory cytokine exerts part of their neurodegenerative effects by disrupting mitochondrial axonal transport [49]. Kinesis and dynein are the motor proteins required for mitochondrial transport and are affected by the Coronavirus [50].

1.2.3. COVID-19, hippocampus disorder and depression

While the human coronavirus (HCoV) infection appears to spread rapidly throughout the CNS, it is more concentrated in the temporal lobe [51]. Several studies point out the vulnerability of the hippocampus to HCoV accompanied by a neuronal reduction in CA1 and CA3 areas and a detrimental effect on learning and spatial memory [52]. The specific vulnerability of the hippocampus to other respiratory virus infections, like the influenza virus, has been previously observed in mice [53]. In this study, the influenza virus alters hippocampal morphology and function and reduces hippocampal spatial memory and LTP. Even if the COVID-19 does not enter the CNS, severe hypoxia induced by respiratory system involvement can be enough to damage the hippocampus [54].

Depression induced by COVID-19 may exacerbate the hippocampus damage in COVID-19. Indeed, the hippocampus is the most interesting structure in the brain for studies related to depression. There are several reasons for this interest: 1. The hippocampus plays an essential role in memory and learning performance; so, its dysfunction may be the cause of inappropriate emotional responses (64). 2. The hippocampus is rich in corticosteroid receptors and has a close anatomical and physiological relationship with the hypothalamus stress axis through the axons of the fornix, which sends regulatory (inhibitory) feedback to the HPA axis.

3. The hippocampus is one of the few areas in the brain with continuous neurogenesis in adulthood; hence, it has a high capacity to activate the process of neuroplasticity [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61].

Studies have shown that depressive disorders are associated with a decrease in the number of neurons and glial cells as well as a decrease in the volume of some areas of the CNS, especially in the hippocampus [62], [63]. A patient with a history of depression shows a significant reduction in hippocampal volume. The frequency and duration of depression periods are also associated with a reduction in the volume of the hippocampus [64].

Because MDD treated patients have a larger hippocampal volume than untreated, the clinical treatment appears to be associated with a return to normal structural changes [65], [66]. Impairment of hippocampal synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis, as well as neurodegeneration and reduction of the volume of the hippocampus due to factors such as inflammation or neurotrophins reduction, contributes to the progression of the depression symptoms [67]. BDNF plays a key role in the growth, maturation, and survival of neurons and synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus. Stress reduces hippocampal BDNF and impairs neuronal survival [68]. The damaged hippocampus cannot adequately regulate (inhibit) the HPA axis allowing high cortisol levels to persist, which is likely to occur in COVID-19 infection disease [69], [70]. Decreased hippocampal neurogenesis is another possible mechanism for the detrimental effects of proinflammatory cytokines. Neurogenesis has been implicated as a key contributing mechanism in the pathophysiology and treatment of depression [61], [71], [72].

1.3. COVID-19, malnutrition and depression

Clinical observations have shown that many patients with COVID-19 suffer from malnutrition. Some symptoms of COVID-19, such as dyspnea, anosmia, anorexia, dysphagia, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, are likely to lead to weight loss and malnutrition. SARS-CoV-2 can invade the epithelium of the oral mucosa and cause painful oral lesions and canker sores that significantly reduce nutrition in COVID-19 patients. Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 increases anxiety in patients, which reduces the patient's appetite and exacerbates malnutrition [73], [74], [75].

COVID-19 induced-malnutrition affects peripheral and central serotonergic pathways through tryptophan (TRP) deficiency (essential amino acid and serotonin precursor). Disruption of the serotonergic system (5-HT) plays an important role in a variety of psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety. Reduced TRP intake leads to decreased serotonin synthesis in the brain. Consumption of essential amino acids seems to increase the TRP / LNAA ratio. This ratio predicts the transfer of tryptophan through the blood–brain barrier to the CSF. Tryptophan is then used to synthesize brain serotonin, which reduces depressive symptoms. The consequences of malnutrition in the serotonergic pathways and depression have been proven [76], [77].

1.4. COVID-19 vitamin D deficiency and depression

Malnutrition reduces the amount of essential vitamins in the body, which causes many neurological side effects such as depression. Some reports indicate that the level of vitamin D3, Zinc, and magnesium in blood serum are significantly related to depression. Vitamin D is one of the most important vitamins for normal CNS function [78], [79]. The active form of vitamin D plays a protective role in the brain by decreasing the calcium concentration in neurons [80], and the vitamin D receptors (VDR) are detected in many parts of the brain. Vitamin D receptors are present in the hippocampus, and vitamin D deficiency is associated with a decrease in the hippocampus volume. Vitamin D also facilitates the production of serotonin in the brain [81], [82], [83], [84].

Vitamin D can protect the neural progenitor of the hippocampus against the negative effects of glucocorticoids, which are high in chronic depression. Moreover, Vitamin D shows its neuroprotective effects in the hippocampus, mainly through its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Vitamin D3 also displays neuroprotection against calcium-induced neurotoxicity in the hippocampus. However, the exact effect of Vitamin D3 on BDNF is not fully understood [84], [85], [86], [87]. An association between depression and vitamin D deficiency has been proven in many studies [81], [82], [88].

People with vitamin D deficiency are more prone to depression [80]. A meta-analysis study confirmed this relationship [89]. Magnesium is important for psychomotor function in major depression [90], and it is effective in the treatment of depression via glutamate [91], and some neurotransmitter systems [92]. Additionally, a negative relationship has been detected between zinc and depression [93].

There is a significant reverse relationship between the mean level of vitamin D and COVID-19 infections in European countries. Studies have shown a correlation between vitamin D levels and COVID-19 severity and mortality. The role of vitamin D in reducing acute viral respiratory tract infections and pneumonia through direct inhibition of virus replication or anti-inflammatory property has been established. Vitamin D supplementation has been shown to be safe and effective against acute respiratory infections. Therefore, people with vitamin D deficiency during the pandemic should consume vitamin D supplements to maintain an optimal blood concentration [75], [94], [95], [96].

Vitamin D can be also useful in the correction of depression induced by COVID-19.

2. Conclusion

COVID-19 has emerged as a pandemic that may have long-term effects on human health. SARS-Cov-2 causes damage to various systems, including the respiratory, gastrointestinal, kidneys, and CNS. Among other common neurological symptoms, COVID-19 patients have also experienced depression. Depression and stress inducted by COVID-19 reduce the immune system and aggravate the infection. SARS-Cov-2 spreads directly and indirectly into the CNS, causes microglia over-activation, and produces inflammatory cytokines. A cytokine storm damages the BBB and exacerbates inflammation. This will ultimately cause apoptosis in various areas of the nervous system, especially the hippocampus. The severity of depression depends on the level of pro-inflammatory cytokines, particularly IL-6. Elevated cortisol levels, changes in the HPA axis, damage to the mitochondria, vitamin D3 deficiency, and malnutrition are some factors involved in the development of depression after infection with SARS-Cov-2. Understanding the mechanisms and factors involved in the development of depression in SARS-Cov-2 is an important factor in finding basic and appropriate therapeutic strategies for the treatment of infected patients.

Conflict of interest statement

There is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Wu F., Zhao S., Yu B., Chen Y.-M., Wang W., Song Z.-G., et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579:265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Su S., Wong G., Shi W., Liu J., Lai A.C., Zhou J., et al. Epidemiology, genetic recombination, and pathogenesis of coronaviruses. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24:490–502. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang W., Tang J., Wei F. Updated understanding of the outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Wuhan, China. J Med Virol. 2020;92:441–447. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hopkins C, Kumar N. Loss of sense of smell as marker of COVID-19 infection. ENT UK [https://www entuk org/sites/default/files/files/Loss of sense of smell as marker of COVID pdf] Date accessed. 2020;26:2020.

- 5.Ren L.-L., Wang Y.-M., Wu Z.-Q., Xiang Z.-C., Guo L., Xu T., et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus causing severe pneumonia in human: a descriptive study. Chin Med J. 2020 doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baud D., Qi X., Nielsen-Saines K., Musso D., Pomar L., Favre G. Real estimates of mortality following COVID-19 infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30195-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rogers J.P., Chesney E., Oliver D., Pollak T.A., McGuire P., Fusar-Poli P., et al. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30203-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmad I., Rathore F.A. Neurological manifestations and complications of COVID-19: a literature review. J Clin Neurosci. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2020.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li H., Xue Q., Xu X. Involvement of the nervous system in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Neurotox Res. 2020;38:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s12640-020-00219-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salinas S., Schiavo G., Kremer E.J. A hitchhiker's guide to the nervous system: the complex journey of viruses and toxins. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:645–655. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swanson P.A., II, McGavern D.B. Viral diseases of the central nervous system. Curr Opin Virol. 2015;11:44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bohmwald K., Galvez N., Ríos M., Kalergis A.M. Neurologic alterations due to respiratory virus infections. Front Cell Neurosci. 2018;12:386. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desforges M., Le Coupanec A., Dubeau P., Bourgouin A., Lajoie L., Dubé M., et al. Human coronaviruses and other respiratory viruses: underestimated opportunistic pathogens of the central nervous system? Viruses. 2020;12:14. doi: 10.3390/v12010014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kessler R.C., Bromet E.J. The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Annu Rev Public Health. 2013;34:119–138. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cavanagh A., Wilson C.J., Kavanagh D.J., Caputi P. Differences in the expression of symptoms in men versus women with depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Harvard Rev Psych. 2017;25:29–38. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winkler D., Pjrek E., Kasper S. Gender-specific symptoms of depression and anger attacks. J Men's Health Gender. 2006;3:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krynicki C.R., Upthegrove R., Deakin J., Barnes T.R. The relationship between negative symptoms and depression in schizophrenia: a systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;137:380–390. doi: 10.1111/acps.12873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parker C., Shalev D., Hsu I., Shenoy A., Cheung S., Nash S., et al. Depression, anxiety, and acute stress disorder among patients hospitalized with COVID-19: a prospective cohort study. Psychosomatics. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2020.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bouças A.P., Rheinheimer J., Lagopoulos J. Why severe COVID-19 patients are at greater risk of developing depression: a molecular perspective. Neuroscientist. 2020 doi: 10.1177/1073858420967892. 1073858420967892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramezani M., Simani L., Karimialavijeh E., Rezaei O., Hajiesmaeili M., Pakdaman H. The role of anxiety and cortisol in outcomes of patients with Covid-19. Basic Clin Neurosci. 2020;11:179. doi: 10.32598/bcn.11.covid19.1168.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deng J., Zhou F., Hou W., Silver Z., Wong C.Y., Chang O., et al. The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances in COVID-19 patients: a meta-analysis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1111/nyas.14506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Röhr S., Müller F., Jung F., Apfelbacher C., Seidler A., Riedel-Heller S.G. Psychosocial impact of quarantine measures during serious coronavirus outbreaks: a rapid review. Psychiatr Prax. 2020;47:179–189. doi: 10.1055/a-1159-5562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cava M.A., Fay K.E., Beanlands H.J., McCay E.A., Wignall R. The experience of quarantine for individuals affected by SARS in Toronto. Public Health Nurs. 2005;22:398–406. doi: 10.1111/j.0737-1209.2005.220504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xin M., Luo S., She R., Yu Y., Li L., Wang S., et al. Negative cognitive and psychological correlates of mandatory quarantine during the initial COVID-19 outbreak in China. Am Psychol. 2020;75:607. doi: 10.1037/amp0000692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mumtaz F., Khan M.I., Zubair M., Dehpour A.R. Neurobiology and consequences of social isolation stress in animal model—A comprehensive review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;105:1205–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.05.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samrah S.M., Al-Mistarehi A.-H., Aleshawi A.J., Khasawneh A.G., Momany S.M., Momany B.S., et al. Depression and coping among COVID-19-infected individuals after 10 days of mandatory in-hospital quarantine, Irbid, Jordan. Psychol Res Behav Manage. 2020;13:823–830. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S267459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N., et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salari N., Hosseinian-Far A., Jalali R., Vaisi-Raygani A., Rasoulpoor S., Mohammadi M., et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Globalization Health. 2020;16:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Misiak B., Łoniewski I., Marlicz W., Frydecka D., Szulc A., Rudzki L., et al. The HPA axis dysregulation in severe mental illness: Can we shift the blame to gut microbiota? Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2020:109951. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.109951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan T., Khoo B., Mills E.G., Phylactou M., Patel B., Eng P.C., et al. Association between high serum total cortisol concentrations and mortality from COVID-19. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:659–660. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30216-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Menke A. Is the HPA axis as target for depression outdated, or is there a new hope? Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:101. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vargas D.L., Nascimbene C., Krishnan C., Zimmerman A.W., Pardo C.A. Neuroglial activation and neuroinflammation in the brain of patients with autism. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:67–81. doi: 10.1002/ana.20315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Block M.L., Calderón-Garcidueñas L. Air pollution: mechanisms of neuroinflammation and CNS disease. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:506–516. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang W-Y, Tan M-S, Yu J-T, Tan L. Role of pro-inflammatory cytokines released from microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Transl Med. 2015;3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Smith J.A., Das A., Ray S.K., Banik N.L. Role of pro-inflammatory cytokines released from microglia in neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Res Bull. 2012;87:10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Balcioglu Y.H., Yesilkaya U.H., Gokcay H., Kirlioglu S.S. May the central nervous system be fogged by the cytokine storm in COVID-19?: An appraisal. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2020;1–2 doi: 10.1007/s11481-020-09932-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Y., Fu L., Gonzales D.M., Lavi E. Coronavirus neurovirulence correlates with the ability of the virus to induce proinflammatory cytokine signals from astrocytes and microglia. J Virol. 2004;78:3398–3406. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.7.3398-3406.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wan S., Yi Q., Fan S., Lv J., Zhang X., Guo L., et al. Characteristics of lymphocyte subsets and cytokines in peripheral blood of 123 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia (NCP) MedRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ting E.-Y.-C., Yang A.C., Tsai S.-J. Role of interleukin-6 in depressive disorder. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:2194. doi: 10.3390/ijms21062194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saleh J., Peyssonnaux C., Singh K.K., Edeas M. Mitochondria and microbiota dysfunction in COVID-19 pathogenesis. Mitochondrion. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2020.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singh K.K., Chaubey G., Chen J.Y., Suravajhala P. Decoding SARS-CoV-2 hijacking of host mitochondria in COVID-19 pathogenesis. Am J Physiol-Cell Physiol. 2020 doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00224.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Onyango I.G., Khan S.M., Bennett J.P., Jr Mitochondria in the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2017;22:854–872. doi: 10.2741/4521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang D.T., Reynolds I.J. Mitochondrial trafficking and morphology in healthy and injured neurons. Prog Neurobiol. 2006;80:241–268. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Messina F., Cecconi F., Rodolfo C. Do you remember Mitochondria? Front Physiol. 2020;11:271. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.00271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bader V., Winklhofer K.F. Seminars in cell & developmental biology. Elsevier; 2020. Mitochondria at the interface between neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation; pp. 163–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sheng Z.-H., Cai Q. Mitochondrial transport in neurons: impact on synaptic homeostasis and neurodegeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:77–93. doi: 10.1038/nrn3156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen J., Vitetta L. Mitochondria could be a potential key mediator linking the intestinal microbiota to depression. J Cell Biochem. 2020;121:17–24. doi: 10.1002/jcb.29311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gardner A., Boles R.G. Beyond the serotonin hypothesis: mitochondria, inflammation and neurodegeneration in major depression and affective spectrum disorders. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35:730–743. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guo W., Dittlau K.S., Van Den Bosch L. Seminars in cell & developmental biology. Elsevier; 2020. Axonal transport defects and neurodegeneration: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications; pp. 133–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wen Z., Zhang Y., Lin Z., Shi K., Jiu Y. Cytoskeleton—a crucial key in host cell for coronavirus infection. J Mol Cell Biol. 2020 doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjaa042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morgello S. Coronaviruses and the central nervous system. J Neurovirol. 2020;26:459–473. doi: 10.1007/s13365-020-00868-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ritchie K., Chan D., Watermeyer T. The cognitive consequences of the COVID-19 epidemic: collateral damage? Brain Commun. 2020;2:fcaa069. doi: 10.1093/braincomms/fcaa069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hosseini S., Wilk E., Michaelsen-Preusse K., Gerhauser I., Baumgärtner W., Geffers R., et al. Long-term neuroinflammation induced by influenza A virus infection and the impact on hippocampal neuron morphology and function. J Neurosci. 2018;38:3060–3080. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1740-17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sharma D., Barhwal K.K., Biswal S.N., Srivastava A.K., Bhardwaj P., Kumar A., et al. Hypoxia-mediated alteration in cholesterol oxidation and raft dynamics regulates BDNF signalling and neurodegeneration in hippocampus. J Neurochem. 2019;148:238–251. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gazzaniga M.S. MIT press; 2009. The cognitive neurosciences. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim G.E., Han J.W., Kim T.H., Suh S.W., Bae J.B., Kim J.H., et al. Hippocampus mediates the effect of emotional support on cognitive function in older adults. J Gerontol: Series A. 2020;75:1502–1507. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glz183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kino T. Stress, glucocorticoid hormones, and hippocampal neural progenitor cells: implications to mood disorders. Front Physiol. 2015;6:230. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li Y., Mu Y., Gage F.H. Development of neural circuits in the adult hippocampus. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2009;87:149–174. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(09)01205-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lucassen P.J., Fitzsimons C.P., Salta E., Maletic-Savatic M. Adult neurogenesis, human after all (again): classic, optimized, and future approaches. Behav Brain Res. 2020;381 doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2019.112458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Terranova J.I., Ogawa S.K., Kitamura T. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis for systems consolidation of memory. Behav Brain Res. 2019;372 doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2019.112035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jesulola E., Micalos P., Baguley I.J. Understanding the pathophysiology of depression: from monoamines to the neurogenesis hypothesis model-are we there yet? Behav Brain Res. 2018;341:79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2017.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cobb J.A., Simpson J., Mahajan G.J., Overholser J.C., Jurjus G.J., Dieter L., et al. Hippocampal volume and total cell numbers in major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rajkowska G., Miguel-Hidalgo J. Gliogenesis and glial pathology in depression. CNS Neurol Disorders-Drug Targets (Formerly Current Drug Targets-CNS & Neurological Disorders) 2007;6:219–233. doi: 10.2174/187152707780619326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Videbech P., Ravnkilde B. Hippocampal volume and depression: a meta-analysis of MRI studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1957–1966. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.MacQueen G.M., Campbell S., McEwen B.S., Macdonald K., Amano S., Joffe R.T., et al. Course of illness, hippocampal function, and hippocampal volume in major depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2003;100:1387–1392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337481100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Katsuki A., Watanabe K., Nguyen L., Otsuka Y., Igata R., Ikenouchi A., et al. Structural changes in hippocampal subfields in patients with continuous remission of drug-naive major depressive disorder. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:3032. doi: 10.3390/ijms21093032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Frodl T., Meisenzahl E.M., Zetzsche T., Höhne T., Banac S., Schorr C., et al. Hippocampal and amygdala changes in patients with major depressive disorder and healthy controls during a 1-year follow-up. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004 doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Miranda M., Morici J.F., Zanoni M.B., Bekinschtein P. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor: a key molecule for memory in the healthy and the pathological brain. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019;13:363. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2019.00363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen X., Zhao B., Qu Y., Chen Y., Xiong J., Feng Y., et al. Detectable serum SARS-CoV-2 viral load (RNAaemia) is closely correlated with drastically elevated interleukin 6 (IL-6) level in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shimizu E., Hashimoto K., Okamura N., Koike K., Komatsu N., Kumakiri C., et al. Alterations of serum levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in depressed patients with or without antidepressants. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:70–75. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00181-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Green H.F., Nolan Y.M. Inflammation and the developing brain: consequences for hippocampal neurogenesis and behavior. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;40:20–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sahay A., Hen R. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis in depression. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1110–1115. doi: 10.1038/nn1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fore H.H., Dongyu Q., Beasley D.M., Ghebreyesus T.A. Child malnutrition and COVID-19: the time to act is now. Lancet. 2020;396:517–518. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31648-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bedock D., Lassen P.B., Mathian A., Moreau P., Couffignal J., Ciangura C., et al. Prevalence and severity of malnutrition in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2020.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li T., Zhang Y., Gong C., Wang J., Liu B., Shi L., et al. Prevalence of malnutrition and analysis of related factors in elderly patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2020:1–5. doi: 10.1038/s41430-020-0642-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gauthier C., Hassler C., Mattar L., Launay J.-M., Callebert J., Steiger H., et al. Symptoms of depression and anxiety in anorexia nervosa: links with plasma tryptophan and serotonin metabolism. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;39:170–178. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.O’Mahony S.M., Clarke G., Borre Y., Dinan T., Cryan J. Serotonin, tryptophan metabolism and the brain-gut-microbiome axis. Behav Brain Res. 2015;277:32–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Merker M., Amsler A., Pereira R., Bolliger R., Tribolet P., Braun N., et al. Vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent in malnourished inpatients and associated with higher mortality: a prospective cohort study. Medicine. 2019;98 doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000018113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Parker G.B., Brotchie H., Graham R.K. Vitamin D and depression. J Affect Disord. 2017;208:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ganji V., Milone C., Cody M.M., McCarty F., Wang Y.T. Serum vitamin D concentrations are related to depression in young adult US population: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Int Arch Med. 2010;3:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1755-7682-3-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Anglin R.E., Samaan Z., Walter S.D., McDonald S.D. Vitamin D deficiency and depression in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202:100–107. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.106666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Spedding S. Vitamin D and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis comparing studies with and without biological flaws. Nutrients. 2014;6:1501–1518. doi: 10.3390/nu6041501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Józefowicz O., Rabe-Jablonska J., Wozniacka A., Strzelecki D. Analysis of vitamin D status in major depression. J Psychiatric Practice. 2014;20:329–337. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000454777.21810.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Eyles D.W., Smith S., Kinobe R., Hewison M., McGrath J.J. Distribution of the vitamin D receptor and 1α-hydroxylase in human brain. J Chem Neuroanat. 2005;29:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhu D.-m., Zhao W., Zhang B., Zhang Y., Yang Y., Zhang C., et al. The relationship between serum concentration of vitamin D, total intracranial volume, and severity of depressive symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:322. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Karakis I., Pase M.P., Beiser A., Booth S.L., Jacques P.F., Rogers G., et al. Association of serum vitamin D with the risk of incident dementia and subclinical indices of brain aging: The Framingham Heart Study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;51:451–461. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Patrick R.P., Ames B.N. Vitamin D hormone regulates serotonin synthesis. Part 1: relevance for autism. FASEB J. 2014;28:2398–2413. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-246546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hastie C.E., Mackay D.F., Ho F., Celis-Morales C.A., Katikireddi S.V., Niedzwiedz C.L., et al. Vitamin D concentrations and COVID-19 infection in UK Biobank. Diab Metab Syndr. 2020;14:561–565. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ju S.-Y., Lee Y.-J., Jeong S.-N. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and the risk of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nutr Health Aging. 2013;17:447–455. doi: 10.1007/s12603-012-0418-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Barra A., Camardese G., Tonioni F., Sgambato A., Picello A., Autullo G., et al. Plasma magnesium level and psychomotor retardation in major depressed patients. Magnes Res. 2007;20:245–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Murck H. Ketamine, magnesium and major depression–from pharmacology to pathophysiology and back. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:955–965. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sotoudeh G., Raisi F., Amini M., Majdzadeh R., Hosseinzadeh M., Khorram Rouz F., et al. Vitamin D deficiency mediates the relationship between dietary patterns and depression: a case–control study. Ann General Psychiatry. 2020;19:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12991-020-00288-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Amani R., Saeidi S., Nazari Z., Nematpour S. Correlation between dietary zinc intakes and its serum levels with depression scales in young female students. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2010;137:150–158. doi: 10.1007/s12011-009-8572-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ali N. Role of vitamin D in preventing of COVID-19 infection, progression and severity. J Infect Public Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ilie PC, Stefanescu S, Smith L. The role of vitamin D in the prevention of coronavirus disease 2019 infection and mortality. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020:1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 96.Hastie C.E., Mackay D.F., Ho F., Celis-Morales C.A., Katikireddi S.V., Niedzwiedz C.L., et al. Vitamin D concentrations and COVID-19 infection in UK Biobank. Diab Metab Syndr. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]