Abstract

Introduction

In recent years, multiple studies have aimed to develop and validate portable technological devices capable of monitoring the motor complications of Parkinson’s disease patients (Parkinson’s Holter). The effectiveness of these monitoring devices for improving clinical control is not known.

Methods and analysis

This is a single-blind, cluster-randomised controlled clinical trial. Neurologists from Spanish health centres will be randomly assigned to one of three study arms (1:1:1): (a) therapeutic adjustment using information from a Parkinson’s Holter that will be worn by their patients for 7 days, (b) therapeutic adjustment using information from a diary of motor fluctuations that will be completed by their patients for 7 days and (c) therapeutic adjustment using clinical information collected during consultation. It is expected that 162 consecutive patients will be included over a period of 6 months.

The primary outcome is the efficiency of the Parkinson’s Holter compared with traditional clinical practice in terms of Off time reduction with respect to the baseline (recorded through a diary of motor fluctuations, which will be completed by all patients). As secondary outcomes, changes in variables related to other motor complications (dyskinesia and freezing of gait), quality of life, autonomy in activities of daily living, adherence to the monitoring system and number of doctor–patient contacts will be analysed. The noninferiority of the Parkinson’s Holter against the diary of motor fluctuations in terms of Off time reduction will be studied as the exploratory objective.

Ethics and dissemination approval for this study has been obtained from the Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge Ethics Committee. The results of this study will inform the practical utility of the objective information provided by a Parkinson’s Holter and, therefore, the convenience of adopting this technology in clinical practice and in future clinical trials. We expect public dissemination of the results in 2022.

Trial registration

Keywords: Parkinson's disease, neurology, clinical trials

Strengths and limitations of this study.

First clinical trial to assess efficacy of a Parkinson’s Holter to improve patients’ motor symptoms.

Three-arm trial comparing the symptomatic control of patients monitored with a Parkinson’s holter, monitored with a patient’s diary or not monitored.

Patients are blind to the study arm.

Neurologists are not blind to the study arm.

Observer bias could happen in some secondary outcomes, which are measured by the neurologists.

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the most common form of chronic and progressive hypokinetic syndrome among the elderly population and is the second most common neurodegenerative disease after Alzheimer’s disease.1 In early stages, PD responds well to dopaminergic therapy; however, as the disease progresses, the duration of the effect decreases and motor complications develop due to ‘wearing off’ effects (end-of-dose deterioration) or due to a delayed or no response to medication, which requires frequent therapeutic adjustments to achieve good symptom control throughout the day.2 Despite all therapeutic adjustment efforts, 90% of patients have motor complications or fluctuations after 10 years.3 These fluctuations consist of changes between periods called Off, in which the medication has no effect and mobility is difficult, and periods called On, in which patients can move fluidly because the medication is having its best effect.4 In addition, in the transition between these two states (On and Off) or during the period of maximum medication effect, patients may present with dyskinesias, that is, involuntary movements of the head, torso or extremities, which may interfere with the patient’s activity.5

Motor complications in patients with advanced disease are not easy to control; they can have a variable character, fluctuating, as mentioned, throughout the day and between different days. The chronology of symptoms throughout the day and between different days is of great value for the precise adjustment of the medication dosage, adapting the scheduled doses to the most prevalent symptoms in the postdose period. However, neurologists do not currently have detailed information on their patients’ symptom chronology; therefore, they have serious difficulties in obtaining good results with medication adjustments. Currently, the information available to neurologists on the hourly course of symptoms comes from the patient’s self-report during consultation, or in the best case, from diaries kept by the patient at home noting their motor state (On or Off) periodically (eg, every hour).6 Although the latter method continues to be the reference standard in research and care, it has serious limitations, as patients often forget to make notes (especially when they are Off), many do not recognise their motor state well, and few can adhere to such a laborious system beyond a few days.7 Thus, a system for measuring motor fluctuations, that is objective, does not require intervention on the part of the patient and can, therefore, be part of their day-to-day for the long term, if necessary, can be of great utility in clinical practice to help optimise medication regimens and improve disease control.8

During the last decade, our research group has developed a system for monitoring patients with PD based on accelerometry that can be comfortably worn at the waist during daily activities. This system is capable of detecting various motor symptoms, including bradykinesia, freezing of gait and dyskinesia,9–11 establishing the chronology of motor fluctuations (On and Off periods) and detecting falls.12 13 This system, which, henceforth, will be generically referred to as Parkinson’s Holter, is possibly the only such system that is easy to carry, is validated under real conditions of use and provides sufficient information to improve the medication regimen. However, it remains a hypothesis that detailed knowledge of the motor symptoms of patients leads to better disease control, thanks to optimisation of the therapeutic regimen. To confirm or refute this hypothesis, we propose a clinical trial in which the clinical effectiveness of this device will be analysed in patients with moderate PD and motor fluctuations.

The primary objective of this trial is to compare the clinical outcomes in patients with PD, measured as changes from baseline to last visit in daily Off time, in three different arms, according to different sources of information in regards of motor fluctuations: (1) Parkinson’s Holter, (2) patient’s diary and (3) no information (the only information that the patient can provide at the visit).

As secondary objectives, besides security issues and user satisfaction with the Parkinson’s Holter, the following efficacy results will be measured: number of medical contacts, adherence to monitoring system, severity of motor complications, severity of freezing of gait, quality of live and performance in activities of daily living performance.

Methods and analysis

Study design

A single-blind, cluster-randomised controlled clinical trial with three arms (1:1:1): group A (therapeutic adjustment using information from a Parkinson’s Holter); group B (therapeutic adjustment using information from a diary of motor fluctuations) and group C (the therapeutic adjustment is not supported by additional information, other than the clinical information collected during consultation).

Study setting and duration

The study will last a maximum of 9 months for each patients (3 months from inclusion to basal visit at maximum and 6 months of follow-up period). The first patient was included in November 2019; the estimated last visit for the last patient is March 2022. Neurologists from at least 40 hospitals in Spain will participate in the study.

Investigational device

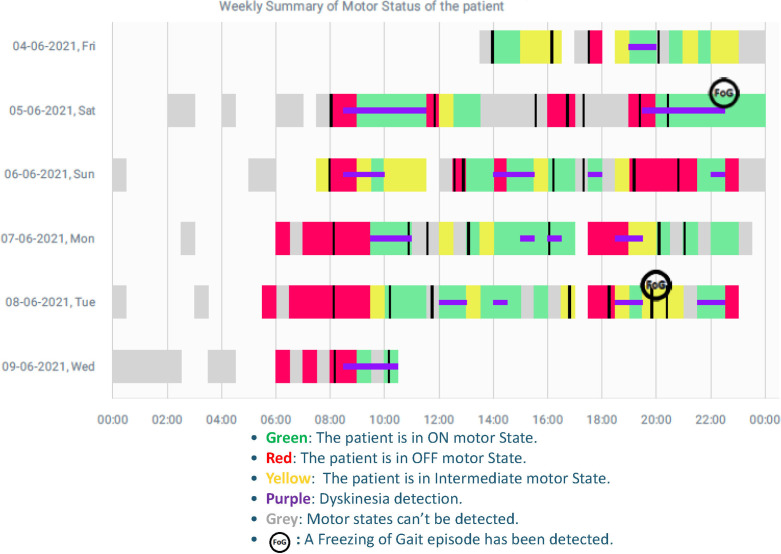

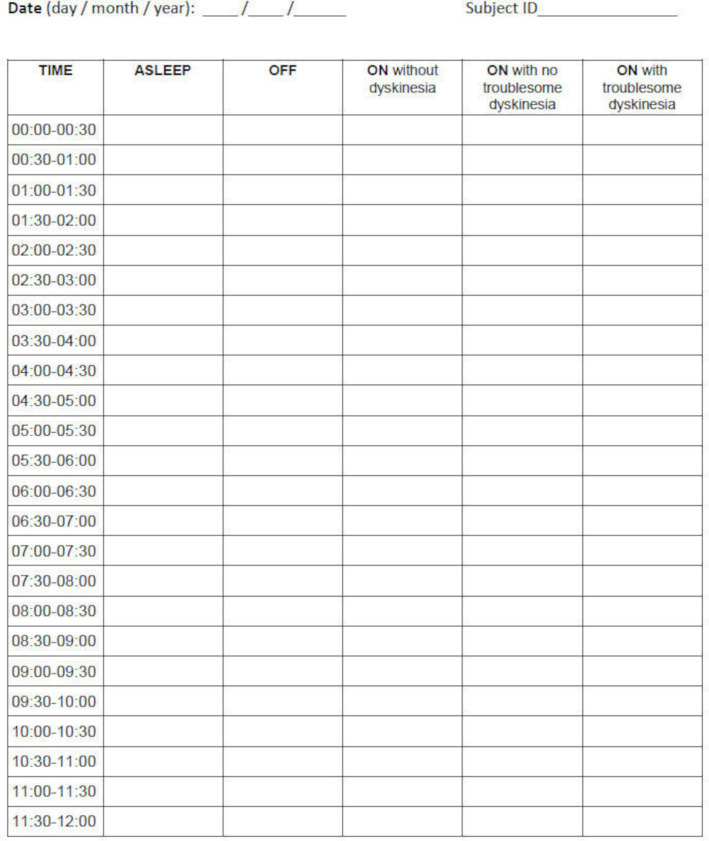

The Parkinson’s Holter is a commercial product (STAT-ON) manufactured by Sense4Care SL (www.sense4care.com). This medical device is intended to ambulatory monitor motor manifestations and activity of Parkinson’s patients. The Holter records motor fluctuations (On and Off periods) during daily activities,14 in addition to dyskinesias, bradykinesia and freezing of gait episodes9–11 (figure 1). Holter’s data are stored in its internal memory and can be downloaded by users (patients or neurologists) to any mobile phone that has the application provided by the manufacturer installed. This application produces reports in PDF, like the ones shown in figures 2 and 3.

Figure 1.

Parkinson’s Holter.

Figure 2.

Parkinson’s Holter summary data table.

Figure 3.

Parkinson’s Holter weekly record.

The first report (figure 2) shows a summary of the data obtained from the patient during the time monitored, including the number of freezing of gait episodes detected and the percentage of time in On, in Off and in status intermediate between the two. The graph shown in figure 3 is the most important for clinicians, since it shows the time course of the different motor symptoms, over a week of time. It needs to be taken into account that a proportion of the time monitored cannot be classified in any of these three motor states (On, Off or intermediate states). As a result, the sum of the time in each motor state does not reach 100%. Time without classification (represented in grey in figure 3) corresponds to the time in which there is not enough data for the device algorithms to reach a conclusion, which occurs frequently in prolonged periods of rest of the patient (in some patients this happens in Off, but this information must be confirmed by the neurologist, through an interview with the patient).

The Parkinson’s Holter must be used a minimum of 3 days, for calibration reasons, and has no upper temporary limit of use (it can be used indefinitely). The manufacturer recommends using it for 7 days to capture the specific changes in motor manifestations and patient’s routines, which often occur on the weekend. The Parkinson’s Holter user manual is available as online supplemental material.

bmjopen-2020-045272supp001.pdf (23.7MB, pdf)

Participants

The target population is patients with PD and difficult-to-control motor fluctuations.

The neurologists participating in the study will select patients from those undergoing follow-up in their outpatient clinic. In line with the clinical use envisaged for Parkinson’s Holter, neurologists are advised to offer the study to those patients who could benefit from daily monitoring of their motor symptoms, in order to better control them. It is planned to include 162 patients who meet all the following inclusion criteria: (1) idiopathic PD according to the clinical criteria of the Brain Bank of the UK,15 (2) moderate to severe disease (Hoehn & Yahr ≥2, in the Off state),16 (3) motor fluctuations present, with at least 2 hours/ day in the Off state. The time in off will be estimated by the neurologist in a first stage (according to the clinical information available) and will be later confirmed by means of a patient’s diary, which all candidates will fill in at home before the baseline study visit (see the Procedures section). To be included in the study, previously informed patients will agree to participate voluntarily and sign a written consent form.

Patients who are unable to walk independently or with Hoehn & Yahr=5, patients participating in another clinical trial, patients with acute intercurrent disease, patients with psychiatric or cognitive disorders preventing collaboration (mini-mental status examination <24)17 and patients with difficulty understanding the study procedures will be excluded.

The neurologists will be professionals who care for patients with PD and who recognise the potential of recruiting five patients with difficult-to-control motor fluctuations at the time of recruitment foreseen in the study.

Interventions and randomisation

Prior to each visit with their neurologist, all patients participating in the study will be monitored using a Parkinson’s Holter during 7 days at home. In addition, all patients of the study will keep a diary of motor fluctuations for 7 days at home, prior to the first and last study visit to the neurologist. The Holter and the diary will be delivered and collected by courier.

The neurologists participating in the study will be randomly assigned to one of the following three groups:

Group A: for therapeutic adjustment, neurologists will have access to the information from the Parkinson’s Holter (study device) and to the information collected during consultation.

Group B: for therapeutic adjustment, neurologists will have access to the information from the diary of motor fluctuations (reference standard) and to the information collected during consultation. In this specific group, patients will fill a motor fluctuations diary, prior to every scheduled visit (not only in the first and last visits).

Group C: for therapeutic adjustment, neurologists will only have access to the information collected during a typical consultation, without information from the Holter’s Parkinson or diary of motor symptoms (traditional clinical practice).

The staff responsible for implementing the randomisation sequence will receive the patient’s clinical information by courier: (1) Holter with data stored on the memory card and (2) patient’s diary of motor fluctuations. This staff will be responsible for sending this information to the patient’ neurologist by encrypted email and before the next appointment: information from the Parkinson’s Holter, diary of motor fluctuations or no additional information. The randomisation sequence will have been performed by independent staff with the help of a table of random numbers and following a balanced blocks model, whose size and composition will not be revealed to the researchers or to the staff responsible for implementing the sequence.18

Procedures

All study patients will wear the sensor 7 days before prior consultation with the neurologist, although this information will not be shown to the neurologist if they are not expected to see it by randomisation arm (group A). Similarly, all patients will keep a diary of motor fluctuations prior to the first and last consultation with the neurologist, although the information will not be shown to the neurologists, unless they belongs to group B. Patients whose neurologist has been assigned to group B will also fill in the diary in the intermediate visits of the study.

The Parkinson’s Holter will be delivered to patients by courier along with the user manual and a quick start guide. There will be a technical assistance telephone line at their disposal to answer questions on how to handle the device. The device will have been previously configured, so that patients only have to turn it on the first time it is taken out of the box by pressing the only button on the device. From that time on, the device will turn on and off autonomously depending on the movement detected by its sensors, so patients do not have to perform any other operation. The device will have a charged battery and autonomy longer than 7 days, so no charger will be provided nor will patients have to worry about recharging the batteries. After the last day of use, the device will be picked up by courier and transported to the centre that manages the deliveries (which is a centre independent of the sponsoring entity) to download the collected data.

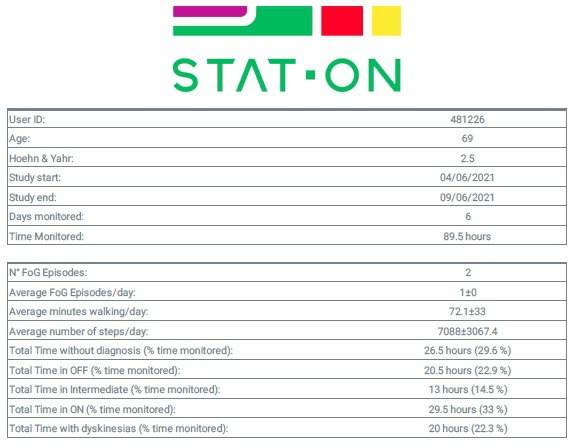

Simultaneously, patients will fill out a diary of motor fluctuations at home. The motor fluctuation diary was designed by the researchers (figure 4), and the neurologists participating in the study will explain to the patients how to fill it out. To do this, the neurologists will follow a common procedure that involves showing instructional videos to patients that provide examples of the different phases (On/Off) and motor complications. The diary of motor fluctuations will be collected by courier on the same day as the Holter device. All patients’ diaries will be reviewed by a devoted team at baseline. Those diaries with completeness problems, duplicates (simultaneous On and Off entries) or mayor inconsistencies will be dismissed, and the investigator will be contacted to make a decision on the convenience of repeating the diary, after retraining the patient or excluding the patient. Patients who have less than 2 hours Off in the first study diary (before the baseline visit) will be considered screening failures and will not be able to continue the study.

Figure 4.

Page 1 of the diary of motor fluctuations.

The results of the measurements taken at home (Holter or diary of motor fluctuations) will be sent to the corresponding neurologists by encrypted email before their next consultation with the patient. All the neurologists will receive specific training in interpreting the Parkinson’s Holter data and will have a manual and an explanatory video available during the study time.

The home monitoring procedure will be repeated systematically before each appointment with the neurologist. The study’s first follow-up visit will take place in week 12 (±2 weeks) after the baseline visit. The study’s last evaluation will be carried out by week 26 (±2 weeks). The neurologist is free to schedule intermediate appointments if necessary, before which the home monitoring process will also be repeated. The efficacy variables described in the next section will be recorded at each study evaluation and at the last appointment, usability and satisfaction questionnaires will also be administered to both the patients and neurologists (table 1).

Table 1.

Schedule of the study evaluations.

| Inclusion | Baseline evaluation | Visit week 12±2 | Unscheduled visit | Visit week 26±2 | |

| Inclusion criteria | X | ||||

| Informed consent | X | ||||

| Sociodemographic data | X | ||||

| Year of diagnosis | X | ||||

| Hoehn and Yahr Scale | X | ||||

| Baseline treatment | X | ||||

| Freezing of Gait Questionnaire | X | X | X | X | |

| Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale | X | X | X | X | |

| 39-item Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire | X | X | X | X | |

| Diary of motor fluctuations | X | X | X | ||

| Parkinson’s Holter | X | X | X | ||

| Record of health visits and contacts | X | X | X | ||

| Record of therapeutic changes/exercise programmes | X | X | X | ||

| Adherence | X | X | X | ||

| Record of adverse effects | X | X | X | ||

| Usability and satisfaction | X |

At the end of the study, the neurologists will receive the complete information from the records of all their patients (regardless of the study group to which they belong) by email, including the diaries of motor fluctuations filled out at home and the complete information from the Parkinson’s Holter.

In this study, there are no concomitant treatments prohibited, although information systems or patient monitoring systems, other than those tested, cannot be used.

Outcome variables and measurement instruments

The efficacy of clinical control will be measured using the following variables.

Primary:

Daily Off time: through a diary of motor fluctuations (On/Off).19 20

Secondary:

Number of medical visits and telephone contacts for medication adjustment.

Record of therapeutic changes.

Record of prescribed exercise programmes.

Adherence to the motor fluctuations recording system (On/Off diary and Parkinson’s Holter).

Motor complications (Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) part IV,21 administered by the neurologist).

Daily On time: through a diary of motor fluctuations (patient’s diary).19

Presence and severity of freezing of gait episodes: Freezing of Gait Questionnaire (FOG-Q, administered to the patient by phone).22

Quality of life: using the 39-item Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39, self-administered by the patient).23

Autonomy in activities of daily living: UPDRS part II21 (administered by the neurologist).

In addition, a record of adverse effects during the study period will be kept and the usability of and user satisfaction with the Parkinson’s Holter will be evaluated using the System Usability Scale (SUS)24 and the Quebec User Evaluation of Satisfaction with Assistive Technologies scale (QUEST),25 respectively.

Other PD-related data will be recorded as control variables (year of PD diagnosis, stage according to the Hoehn & Yahr scale in the Off state,15 patient sociodemographic data (age, sex, educational level) and neurologist data: age, sex, years of practice, type of activity (consultation, ward etc) and number of patients treated per year at each care level.

Monitoring

All study data and procedures will be supervised by an independent monitor. The supervision will be carried out in accordance with Best Clinical Practices, ISO 14155:2011.

Blinding

The participating patients are responsible for recording the main variable (Off time) in their diary of motor fluctuations. Patients will be blinded to the neurologist’s randomisation arm, who will not disclose what information is available to adjust the therapeutic regimen. Patients are also responsible for recording the On time (diary of motor fluctuations) and the variables related to FOG-Q and quality of life (PDQ-39); therefore, there is blinding to these data. The neurologists are responsible for collecting the UPDRS data and recording the therapeutic changes and adverse effects; therefore, there is no blinding to these secondary variables. The data analysts will also be blinded to the type of intervention in each group.

Blinding could be broken in the event the patient’s physician deems it vital to access any of the study information (especially the patient’s diary filled out at home) because the patient’s clinical situation requires it. This fact will be recorded for later exclusion from all analyses potentially affected by the infringement of the protocol

Sample size

Assuming a mean reduction from baseline of 75 min of Off time daily (SD 130) between arm A and C, a sample size of 49 patients per group would provide 80% power to show superiority at a significance level alpha of 5% (two sided).

Unassessable patients will be those that signed the informed consent form (inclusion visit) but are lost to follow-up before the baseline visit. The rest of the subjects will be assessable even if they are not adherent to the motor fluctuation measurement systems. To cover loss to follow-up and unassessable patients, the sample size will be increased by 10%, so that, in principle, 162 patients will be necessary (54/arm). A standard method to handle missing data (last observation carried forward) will be used.

The inclusion of 40 physicians is proposed, assuming that each physician will include four or five patients in the study

Data analysis plan

In the patient’s diary (main outcome variable), lost data will be imputed, by interpolation between equal data, provided that the period without data does not exceed the hour of duration. No other lost data of the study will be imputed.

A fixed effects analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the baseline Off time as a covariate will be used to test the superiority of group A versus group C in the overall analysis and the noninferiority of group B in the per-protocol analysis.

A descriptive analysis of all the variables included in the study will be performed. For the quantitative variables, robust estimators of central tendency (mean, winsorized mean, trimmed mean, Huber estimator) and of sample variability (SD, standardised median absolute deviation, sample quasi-α-Winsorised-standard deviation, weighted root mean variance and the adjusted percentage root mean variance) will be used. CIs will be calculated by applying bootstrap or resampling methods. The maximum, minimum, skewness and kurtosis of the distributions will be calculated. For comparison of two related means, the Wilcoxon test or the robust generalisation of repeated measures ANOVA will be used.

For qualitative variables, the frequency of the distributions will be calculated with percentages. For comparisons, Pearson’s χ2 or McNemar’s test will be used as appropriate.

The total score on the usability and user satisfaction scales (SUS and QUEST) will be calculated according to the instructions of each instrument, and a descriptive analysis of these results will be performed for the overall sample. The results for the usability of and the physician satisfaction with the device will be analysed for the overall sample.

Finally, a descriptive analysis of the frequency and severity of the adverse effects and device-related adverse effects will be performed.

Patients lost to follow-up will be included in the analysis if at least one therapeutic adjustment was made before dropout. The baseline data of the patients lost before this point, will be also analysed in order to study the potential impact of these dropouts in the balance between groups, regarding the main confounding factors.

The analysts will be blinded to the type of diagnostic intervention in each group.

Patient involvement

Patients were not involved in the design, recruitment or choice of outcome measures of this research protocol. However, patients played a central role in the development of the Parkinson’s Holter, carried out by the research team in previous research projects. Selected groups of patients, who were involved from first stages, contributed to identify needs and use cases, provided information on their symptoms and feedback on design and usability, which have served to improve the product in various iterations. Parkinson’s patient associations will be involved in development of the dissemination plan of the results.

Ethics and dissemination

This protocol and the informed consent form were approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge (code AC012/19). Any protocol change that may increase the risk or present new risks for the patient, or that may affect the validity of the study, must be approved by the sponsor in writing before being implemented. All study participants will sign the written consent form, after being properly informed by a study local investigator.

In all of the reports and communications related to the study subjects, the subjects will be identified only by their case numbers. Data will be handled strictly in accordance with the professional standards of confidentiality, under the terms stipulated in Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and the Council of 27 April 2016 on Information Protection (General Data Protection Regulation).

The sponsor has a civil liability insurance policy that covers the potential damages for participants that could derive from the application of this protocol.

The results will be disseminated to the scientific community in the form of a publication, preferably in an open access journal, and to the general population, by press release for the national media. Various Spanish and European patient associations will receive direct communication of the results.

Discussion

This study will evaluate the efficacy of a PD symptom monitoring device for improving the clinical control of patients. This improvement will be measured in the form of a reduction in the daily Off time and according to other health outcomes as well as the neurologists’ and patients’ satisfaction with the device.

Although multiple studies have explored the validity of various devices for monitoring PD symptoms, currently there is no evidence of the therapeutic efficacy of monitoring by such means.26 That the developed devices correctly monitor motor symptoms, does not necessarily imply that this monitoring improves clinical control. This is the first study to examine the efficacy, in terms of clinical control, of these new sensors. Additionally, the same data may be used to test the efficacy of motor fluctuation diaries, considered a reference standard, which have been previously validated but for which there are also no available clinical efficacy studies.19 The results of this study will provide information on the practical utility of the objective information that these devices provide and, therefore, on the convenience of adopting this technology in clinical practice, in future clinical trials and in various studies on PD.

It is important to clarify that although the Parkinson’s Holter has a fall detection functionality, it has not been fully implemented in the study (the verification step by the user was omitted), so the information related to falls will not be analysed.

This study has some limitations, such as the lack of blinding of the neurologists, which is inherent to the objective of the study: neurologists must necessarily know the monitoring information that has been assigned to them by chance. This could lead to a greater effort to optimise the medication regimen by neurologists with access to Holter data and by neurologists with access to the diary. While this phenomenon is not due to a Hawthorne effect (neurologists try harder because they know they are being observed in the study), it is not necessarily a negative phenomenon, since it is possible that part of the improvement potentially produced by these means of monitoring is due to the neurologist’s increased attention to the case. That is, it is possible that the diary or Holter produce better clinical results not only because of the information they produce but also because they encourage neurologists to better adjust medication, which is one of the positive effects that should be included in the observation.

In contrast, neurologists may in fact be subjected to the aforementioned Hawthorne effect.27 Given that the protocol is identical in all arms of the study, if the Hawthorne effect is symmetrical, that is, if it has the same consequences in all arms, it will not affect the relative comparisons between arms. However, if the effect is more marked in any of the arms (eg, in the case of neurologists who do not have additional information but who particularly strive due to being observed in the study), then the differences observed in the study may vary with respect to the real ones in clinical practice.

In addition, observer bias may occur in this study because the neurologists, who know the information they have managed, are also responsible for applying some instruments to measure the secondary outcomes.28 That is, knowledge of the study arm can lead to changes in the way the UPDRS is applied or interpreted, for example. This bias has been reduced as much as possible by removing the responsibility of applying the scales from the participating neurologists: the scales will be self-applied or applied by telephone by a blinded evaluator, except for the UPDRS, which requires a physical examination by the neurologist. In any case, the results to which the neurologists were not blinded will be analysed with techniques that attempt to determine the presence of this bias: observer bias tends to more strongly affect less severe patients; therefore, if the intervention is effective only in less severe patients, the possible presence of this bias will be reported.29

Finally, the duration of the clinical review has not been considered as a variable, thus, there will not be possible to draw conclusions on the time consumed in patient attention in the different study arms.

In conclusion, this clinical trial has been designed to determine whether automated symptom monitoring systems (Parkinson’s Holter) improve the clinical control of patients with motor fluctuations. We expect the first results in 2022.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Collaborators: This research is being conducted by the 'Monitoring Parkinson’s patients Mobility for therapeutic purposes' (MoMoPa) research group, which includes, in addition to the authors of this papers: Hospital de Sant Joan Despí Moisès Broggi (Nuria Caballol Pons, Anna Planas-Ballvé), Hospital Universitari Mútua Terrassa (Mariateresa Buongiorno, Pau Pastor, Ignacio Alvarez), Hospital Universitario de Toledo (Núria López Ariztegui, Mª Isabel Morales Casado), Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal (Gema Sánchez), Hospital General de l'Hospitalet (María Asunción Ávila Rivera), Terapia Integral Uparkinson (Anna Prats), Hospital General Universitario de Elche (María Álvarez Saúco), Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau (Alexandre Gironell Carreró), Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre (Álvaro Sánchez-Ferro, Antonio Méndez Guerrero), Hospital Sant Camil (Elisabet Franquet Gomez), Hospital de Tortosa Verge de la Cinta (Sonia Escalante Arroyo), Instituto de Biomedicina de Sevilla, Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío/CSIC/Universidad de Sevilla (Laura Muñoz-Delgado, Daniel Macías-García, Silvia Jesús, Astrid Adarmes-Gómez, Pablo Mir), Hospital Clínico de Valencia (José Mª Salom Juan, Antonio Salvador Aliaga), Hospital General de Alicante (Silvia Martí Martínez, Carlos Leiva Santana), Hospital del Mar (Victor M. Puente Pérez, Irene Navalpotro Gómez), Hospital Vall d'Hebron (Sara Lucas del Pozo), Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón (Lydia Vela Desojo), Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro (Antonio Koukoulis Fernández, Mª Gema Alonso Losada), Hospital Universitario de Burgos (Mª Esther Cubo Delgado), Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla (Jon Infante Ceberío, María Sierra Peña, Isabel González Aramburu, Mª Victoria Sánchez Peláez), Hospital Universitario Infanta Sofía (Marina Mata Álvarez-Santullano, Carmen Borrúe Fernández, Mª Concepción Jimeno Montero), Clínico Virgen de la Victoria (Mª José Gómez Heredia, Francisco Pérez Errazquin, Lina Carazo Barrios), Hospital Royo Villanova (Alfredo López López), Hospital de Llíria (Mª Pilar Solís Pérez), Hospital Univ Lucus Augusti (Rubén Alonso Redondo, Jessica González Ardura), Hospital Universitario Donostia (Javier Ruiz Martínez, Ana Vinagre Aragón, Ioana Croitoru), Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro Majadahonda (Pilar Sánchez Alonso, Elisa Gamo Gonzalez, Sabela Novo Ponte), Hospital Moraleja (Esteban Peña Llamas), Hospital Alcázar de San Juan (Esther Blanco Vicente, Rafael García Ruiz, Ana Rita Santos Pinto, Marta Recio-Bermejo), Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca de Murcia (José López Sánchez, Judith Jiménez Veiga), Hospital Regional de Málaga (Teresa Muñoz Ruiz, Lucía Flores García), Hospital Clínico San Carlos (Rocío García-Ramos, Eva López Valdés), Hospital German Trias i Pujol (Lourdes Ispierto González, Ramiro Álvarez Ramo, Dolores Vilas Rolan), Hospital Comarcal de l'Alt Penedès (Esther Catena Ruiz), Hospital Universitari General de Catalunya (Ernest Balaguer, Antonio Hernández Vidal), Hospital Universitari de Girona Doctor Josep Trueta (Berta Solano Vila, Anna Cots Foraster, Daniel López Domínguez), Hospital la Princesa (Lydia López‐Manzanares)

Contributors: AR-M conceived and designed the study, and drafted this paper. JH-V, AB, JCM-C and DADAP-M contributed to the study design. CP-L contributed to study logistics preparation, including software for managing Parkinson’s Holter data during the trial. AM contributed to the statistical analysis plan. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding: This work is supported by AbbVie S.L.U, the Instituto de Salud Carlos III [DTS17/00195] and the European Fund for Regional Development, 'A way to make Europe'.

Competing interests: AR-M and CP-L are shareholders of Sense4Care, the company that will market the tested device in the short term. AR-M participated with other authors in obtaining funding for the study and in the protocol design. Given his conflict of interest, he will manage the project as the sponsoring centre’s coordinator but will not participate in the data collection, study monitoring, statistical analysis or interpretation of results. CP-L only contributed to study logistics preparation, including software for managing Parkinson’s Holter data during the trial.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Contributor Information

Monitoring Parkinson’s patients Mobility for therapeutic purposes research group:

Nuria Caballol, Anna Planas-Ballvé, Mariateresa Buongiorno, Pau Pastor, Ignacio Alvarez, Núria López, Mª Isabel Morales, Gema Sánchez, María Asunción Ávila, Anna Prats, María Álvarez, Alexandre Gironell, Álvaro Sánchez-Ferro, Antonio Méndez, Elisabet Franquet, Sonia Escalante, Laura Muñoz-Delgado, Daniel Macías-García, Silvia Jesús, Astrid Adarmes-Gómez, Pablo Mir, José Mª Salom, Antonio Salvador, Silvia Martí, Carlos Leiva, Victor M. Puente, Irene Navalpotro, Sara Lucas, Lydia Vela, Antonio Koukoulis, Mª Gema Alonso, Mª Esther Cubo, Jon Infante, María Sierra, Isabel González, Mª Victoria Sánchez, Marina Mata, Carmen Borrúe, Mª Concepción Jimeno, Mª José Gómez, Francisco Pérez, Lina Carazo, Alfredo López, Mª Pilar Solís, Rubén Alonso, Jessica González, Javier Ruiz, Ana Vinagre, Ioana Croitoru, Pilar Sánchez, Elisa Gamo, Sabela Novo, Esteban Peña, Esther Blanco, Rafael García, Ana Rita Santos, José López, Judith Jiménez, Teresa Muñoz, Lucía Flores, Rocío García-Ramos, Eva López, Lourdes Ispierto, Ramiro Álvarez, Dolores Vilas, Esther Catena, Ernest Balaguer, Antonio Hernández, Berta Solano, Anna Cots, Daniel López, Lydia López Manzanares, and Marta Recio-Bermejo

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1. Hirtz D, Thurman DJ, Gwinn-Hardy K, et al. How common are the "common" neurologic disorders? Neurology 2007;68:326–37. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000252807.38124.a3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kalia LV, Lang AE. Parkinson's disease. Lancet 2015;386:896–912. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61393-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. García-Ruiz PJ, Del Val J, Fernández IM, et al. What factors influence motor complications in Parkinson disease?: a 10-year prospective study. Clin Neuropharmacol 2012;35:1–5. 10.1097/WNF.0b013e31823dec73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fahn S, Oakes D, Shoulson I, et al. Levodopa and the progression of Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med 2004;351:2498–508. 10.1056/NEJMoa033447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ahlskog JE, Muenter MD. Frequency of levodopa-related dyskinesias and motor fluctuations as estimated from the cumulative literature. Mov Disord 2001;16:448–58 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11391738 10.1002/mds.1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reimer J, Grabowski M, Lindvall O, et al. Use and interpretation of on/off diaries in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004;75:396–400. 10.1136/jnnp.2003.022780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Papapetropoulos SS. Patient diaries as a clinical endpoint in Parkinson's disease clinical trials. CNS Neurosci Ther 2012;18:380–7. 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2011.00253.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maetzler W, Domingos J, Srulijes K, et al. Quantitative wearable sensors for objective assessment of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2013;28:1628–37. 10.1002/mds.25628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sam A, Pérez-López C, Rodríguez-Martín D. Estimating bradykinesia severity in Parkinson’s disease by analysing gait through a waist-worn sensor. Comput Biol Med 2017;84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rodríguez-Martín D, Samà A, Pérez-López C, et al. Home detection of freezing of gait using support vector machines through a single waist-worn triaxial accelerometer. PLoS One 2017;12:e0171764. 10.1371/journal.pone.0171764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pérez-López C, Samà A, Rodríguez-Martín D, et al. Dopaminergic-induced dyskinesia assessment based on a single belt-worn accelerometer. Artif Intell Med 2016;67:47–56. 10.1016/j.artmed.2016.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rodríguez-Molinero A, Pérez-López C, Samà A, et al. A kinematic sensor and algorithm to detect motor fluctuations in Parkinson disease: validation study under real conditions of use. JMIR Rehabil Assist Technol 2018;5:e8. 10.2196/rehab.8335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rodríguez-Molinero A, Samà A, Pérez-Martínez DA, et al. Validation of a Portable Device for Mapping Motor and Gait Disturbances in Parkinson’s Disease. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2015;3:e9. 10.2196/mhealth.3321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rodríguez-Molinero A, Pérez-López C, Samà A, et al. A kinematic sensor and algorithm to detect motor fluctuations in Parkinson disease: validation study under real conditions of use. JMIR Rehabil Assist Technol 2018;5:e8. 10.2196/rehab.8335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Kilford L, et al. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: a clinico-pathological study of 100 cases. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 1992;55:181–4. 10.1136/jnnp.55.3.181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology 1967;17:427–42 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6067254 10.1212/WNL.17.5.427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–98 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1202204 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Altman DG, Bland JM. Statistics notes: how to randomise. BMJ 1999;319:703–4 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1116549/ 10.1136/bmj.319.7211.703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hauser RA, Deckers F, Lehert P. Parkinson's disease home diary: further validation and implications for clinical trials. Mov Disord 2004;19:1409–13. 10.1002/mds.20248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hauser RA, Friedlander J, Zesiewicz TA, et al. A home diary to assess functional status in patients with Parkinson's disease with motor fluctuations and dyskinesia. Clin Neuropharmacol 2000;23:75–81 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10803796 10.1097/00002826-200003000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fahn S. Elton R M of the UDC. In: Fahn S, Mardsen CD, Jenner P, eds. Recent Developments in Parkinson’s Disease. New York, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Giladi N, Tal J, Azulay T, et al. Validation of the freezing of gait questionnaire in patients with Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2009;24:655–61. 10.1002/mds.21745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Martínez-Martín P, Frades Payo B. Quality of life in Parkinson's disease: validation study of the PDQ-39 Spanish version. The Grupo Centro for study of movement disorders. J Neurol 1998;245 Suppl 1:S34–8 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9617722 10.1007/pl00007737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brooke J. Sus: a retrospective 2013;8:29–40 http://www.usabilityprofessionals.org [Google Scholar]

- 25. Demers L, Weiss-Lambrou R, Ska B. Development of the Quebec user evaluation of satisfaction with assistive technology (quest). Assist Technol 1996;8:3–13. 10.1080/10400435.1996.10132268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Odin P, Chaudhuri KR, Volkmann J. Viewpoint and practical recommendations from a movement disorder specialist panel on objective measurement in the clinical management of Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Park Dis 2018;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Parsons HM. What happened at Hawthorne?: new evidence suggests the Hawthorne effect resulted from operant reinforcement contingencies. Science 1974;183:922–32. 10.1126/science.183.4128.922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hróbjartsson A, Thomsen ASS, Emanuelsson F, et al. Observer bias in randomized clinical trials with measurement scale outcomes: a systematic review of trials with both blinded and nonblinded assessors. CMAJ 2013;185:E201–11. 10.1503/cmaj.120744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Szklo M, Nieto FJ. Epidemiología Intermedia : Conceptos Y Aplicaciones. Díaz de Santos, 2003. Available: https://www.casadellibro.com/libro-epidemiologia-intermedia-conceptos-y-aplicaciones/9788479785956/927995 [Accessed 4 Dec 2017].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-045272supp001.pdf (23.7MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study.