Abstract

This community-based participatory research (CBPR) project used a collaborative process to develop a culturally relevant workbook for parents of overweight children. We followed a mixed methods iterative process to assess clear communication using a CBPR approach. Materials were evaluated using readability tests, the Clear Communication Index (CCI), and the Suitability Assessment of Materials (SAM). In addition, we used surveys and focus groups to investigate parents’ perceptions and gather feedback from delivery staff using the workbook. While workbook materials maintained adequate grade reading levels, our iterative process and the use of CCI and SAM led to significant improvements in (a) clearly communicating the objectives of the program, (b) being culturally relevant, and (c) reaching a high satisfaction among users. These findings suggest that evaluative measures for written materials should move beyond readability and need to account for level of clarity and cultural appropriateness of messages. Furthermore, we found that that an iterative process to intervention’s material development using clear communication strategies while involving community members, parents, and research partners can lead to workbook materials that are culturally relevant to the target audience, and better communicate program objectives. Finally, this is a potentially generalizable process for improving clear communication of written health information materials.

Keywords: childhood obesity, clear communication, community-based participatory research, medically underserved area, health literacy, mixed methods, health communication, human communication, communication studies, communication, social sciences

Introduction

Health literacy (HL) among the general public has become progressively more important for public health because many aspects of health care depend on understanding written information and verbal instruction (McCormack et al., 2010). HL includes addressing individual skill development as well as providing the delivery of actionable information that is easily understood in a manner appropriate to the audience (U.S. Department of Health Human Services and Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2010). Many of the same populations at risk for limited HL also suffer from disparities in health outcomes (Berkman et al., 2011; Mantwill, Monestel-Umaña, & Schulz, 2015). Not surprisingly, both low HL and childhood obesity disproportionately affect rural and low-income populations (Paasche-Orlow, Parker, Gazmararian, Nielsen-Bohlman, & Rudd, 2005; Zahnd, Scaife, & Francis, 2009), with children from parents with low HL having greater obesity risk (Chari, Warsh, Ketterer, Hossain, & Sharif, 2014; Sanders, Federico, Klass, Abrams, & Dreyer, 2009). Thus, it is critical to determine the degree to which written materials clearly and effectively communicate health information when adapting evidence-based childhood obesity interventions for families in health disparate communities.

National initiatives have focused on incorporating health communication approaches to provide accessible information targeting individuals’ literacy and cultural preferences (National Institutes of Health, 2015; Plain Language Action and Information Network, 2010; U.S. Department of Health Human Services and Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2010). The goal is to develop materials that attract and hold the readers’ attention, make them feel respected and understood, and motivate action (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2010). Accordingly, a number of tools have been created to guide the development and evaluation of written materials for programs and interventions (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013; Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2010). However, despite being highly recommended (Brach et al., 2012; Koh et al., 2012), these tools are rarely used in the development of health promotion materials within a research setting.

The lack of use of health communication approaches may be one of the underlying reasons that HL emerges as a contributing factor of childhood obesity (Chari et al., 2014). Various family-based treatment interventions have been developed to address childhood obesity (Ash, Agaronov, Young, Aftosmes-Tobio, & Davison, 2017; Bleich et al., 2018) and, while all include written materials (White et al., 2013), there is limited evidence that those materials have been adapted and or developed using clear communication strategies. In addition, written materials used in efficacy studies with narrowly defined study populations may be less clear for audiences beyond the original study population (Brach et al., 2012), highlighting the potential low generaliz-ability of written materials used in efficacy trials.

A potential strategy to deliver actionable audience-appropriate information is to engage individuals, familiar with the cultural and linguistic patterns of the intended audience, representing a broad range of expertise, skills, and interests in the development and evaluation of health materials. In this context, effectively engaging the targeted community and research organizations in community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach may lead to improved health communication and the use of culturally appropriate materials (Israel, Eng, Schulz, & Parker, 2013; Lytle, 2009). In addition, a CBPR approach allows team members that interact with patients/participants on a regular basis to provide feedback on communication styles that may be more or less effective within the target population. Finally, obtaining feedback from members of the target population is an essential component in the process to ensure participant-level relevance of the written materials (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2010).

This article describes the development of a culturally relevant workbook for parents of overweight children that used clear communication strategies to address key learning objectives from Bright Bodies (Savoye et al., 2005), an efficacious childhood obesity treatment program. To assess clear communication using a community-academic partnership approach, we used an iterative and systematic mixed methods process in the development and assessment of the intervention materials. We hypothesized that an iterative process that included the engagement of program participants and community staff in the development, evaluation, and revision of a program workbook would result in materials that were consistent with local culture (e.g., ways of thinking, communicating, and behaving specific to a given location and/or population) and clear communication strategies.

Method

Setting and Intervention Description

The Dan River Region (DRR) is a predominantly rural, health disparate and federally designated medically underserved area (Virginia Department of Health, 2008, 2012b) located in south-central Virginia and north-central North Carolina. The region currently has some of the lowest HL and highest rates of childhood obesity in the country (County Health Rankings & Roadmaps, 2015; Virginia Department of Health, 2012a). The Dan River Partnership for a Healthy Community (DRPHC) was formed as a community-academic partnership using CBPR principles with a primary mission to address obesity in the region. Under the larger DRPHC umbrella, clinical and community partners serving children in the region formed the Partnering for Obesity Planning and Sustainability (POPS) community advisory board (CAB) to develop programming specifically to treat childhood obesity (Zoellner, Hill, Brock, et al., 2017). This advisory board, collaboratively selected the Bright Bodies intervention, an evidence and family-based childhood obesity treatment program tested in metropolitan areas in Connecticut (Savoye et al., 2005), and adapted the content and structure for local delivery in the form of the iChoose program.

iChoose was developed based on the underlying principles and learning objectives of Bright Bodies, but differed in structure and duration, based on locally available resources to address childhood obesity (Zoellner, Hill, Brock, et al., 2017). iChoose is a 3-month family-based program that includes the following components: (a) biweekly 120-min family sessions over the 12-week program, including a nutrition lesson, exercise time, and behavioral skills training; (b) biweekly 25-min telephone support calls to set goals, resolve barriers, and reinforce content using the 5 A’s (Assess, Advise, Agree, Assist, Arrange), teach-back and teach-to-goal strategies on weeks between family sessions; (c) two 60-min exercise sessions per week; (d) workbooks for the parent and the child; and (e) biweekly child newsletters that reinforced content and provided fun activities.

Clear Communication Strategies

The foundation of clear communication strategies to help produce “low barrier” health information material includes plain language and a reader-centered approach (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2010). Plain language simplifies information without sacrificing the content or compromising the meaning. This approach gives special attention to graphic design and issues of cultural appropriateness, thereby making materials appealing to readers at all literacy levels. A reader-centered approach strives to understand the intended audiences by taking the reader’s perspective in identifying possible barriers within the written material. Most clear communication guidelines are derived from the social marketing framework and seek to improve communication of health messages (U.S. Department of Health Human Services, 1992). This framework proposes tailoring messages to fulfill the interests of those who would benefit from a behavior change and those who want to promote the desired behavior (Maibach, Rothschild, & Novelli, 2002). Messages are implemented as a systematic, continuous process driven by decision-based research in which feedback is used to adjust the message to ensure that all efforts are integrated and consistently support the intervention’s goals and objectives (Glanz & Rimer, 1997).

Participatory Approach

We used a CBPR approach to engage community and research organizations to review, adapt, implement, and evaluate (Lytle, 2009) written materials used in the intervention. This participatory approach has been shown to reduce health disparities and enhance study relevance, validity, effectiveness, cultural sensitivity, and translation into practice (Choudhry et al., 2011; K. J. Coleman et al., 2005; Economos et al., 2007; Economos et al., 2013). The POPS-CAB was composed of academic researchers and community partners. The community and clinic partners are from the Pittsylvania/Danville Health District (PDHD), Children’s Healthcare Center (CHC), Danville Parks Recreation & Tourism, and Boys & Girls Club. Planning process and first-year experiences of the POPS-CAB were described elsewhere (Zoellner, Hill, You, et al., 2017). The CBPR approach also aligned with an important strategy to improve clear communication—the team approach (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2010). The team approach included members from the community, engaged delivery staff, parents from the intended audience, and researchers.

Development and Evaluation Process of iChoose Workbooks

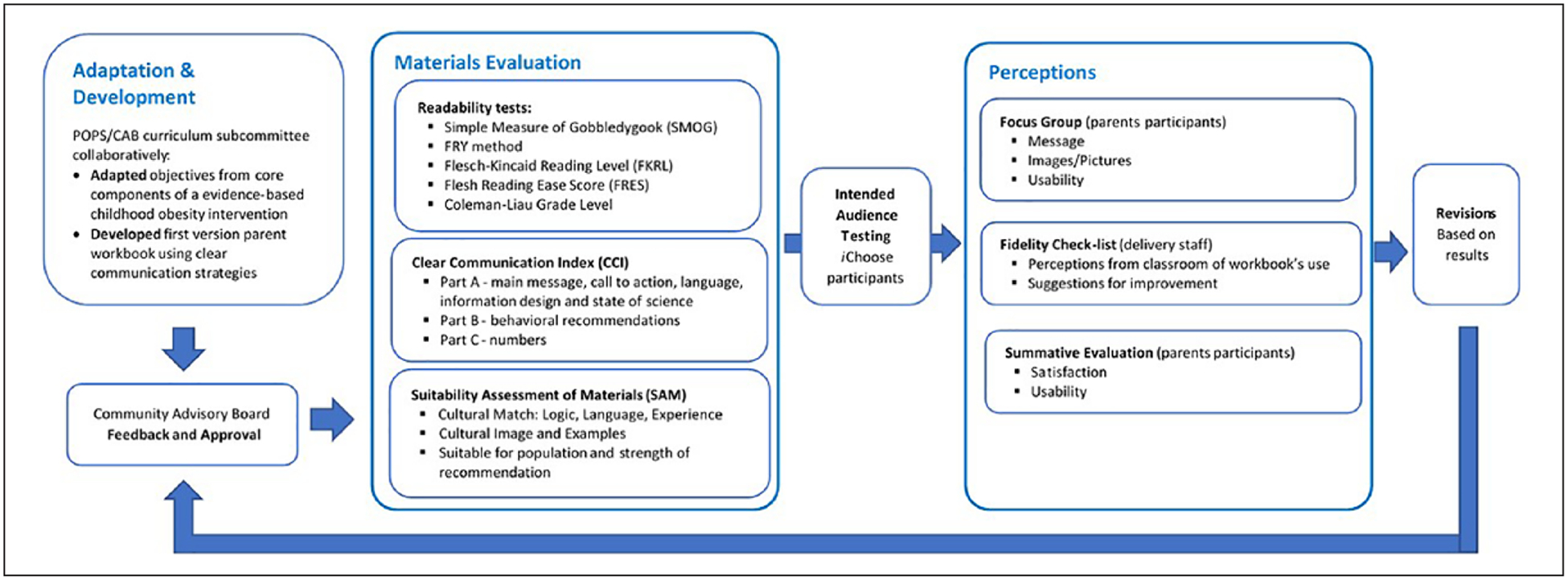

One objective of the POPS-CAB was to create materials that would be relevant to local families. Thus, we designed a mixed methods approach that would engage the POPS-CAB and end users of the workbook in a process to review and adapt materials. Accordingly, we developed a formative evaluation process of the iChoose workbook using CBPR in a reader-centered approach. Our systematic process included a multistep process for each module to ensure that materials were appropriate for a low health literate audience (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Development of workbook content using clear communication strategies.

Note. POPS = Partnering for Obesity Planning and Sustainability; CAB = community advisory board.

The overall research design for the development and evaluation of the iChoose workbook was a participatory and iterative mixed method design. Due the prolonged dynamic and complex contact with the community the use of mixed methods are useful in CBPR research (Lucero et al., 2018), as it allow us to draw upon the strengths of both the depth of qualitative research and the breath of quantitative work (Fetters, Curry, & Creswell, 2013). In addition, our participatory and iterative approach allows for the use of qualitative data to provide direction for improvements in the written materials—where quantitative data indicated improvements were necessary (Fetters et al., 2013). The mixed method data collection was used to strengthen the validity of the conclusions reached by the study (Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, 2004). During the process, we performed triangulation of quantitative (Clear Communication Index [CCI], Suitability Assessment of Materials [SAM], readability tests and surveys) and qualitative (interviews, classroom feedback and focus groups [FGs]) methods from different sources (i.e., community and academic partners, delivery staff, and parents) to increase the likelihood that refined materials met the needs of participants and delivery personnel while also adhering to the evidence-based principles at the core of the program. Triangulation is considered a useful means of capturing more detail, minimizing the effects of bias, and ensuring a balanced interpretation of available data and soundness of study conclusions in qualitative studies (Jakob, 2001). Both participatory and formative evaluation approaches (Israel et al., 2013) were designed to involve the POPS-CAB members and program participants, in multiple components of the process. The intent was not only to develop an evidence-based workbook but also incorporate HL best practices to achieve a clear and effective communication with the target population. This case study occurred over a period of 3 years and is embedded within a larger CBPR pilot trial of the iChoose program (NIMHD-R24MD008005). The Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Virginia Tech approved this study, and all participants gave written informed consent prior to participation.

Adaptation and development of the workbook.

After the intervention selection process by the POPS-CAB members, community partners identified that the written materials from the selected intervention (Bright Bodies) needed adaptations to better fit their community profile, including more culturally relevant content and images as well as the need to address different levels of HL. As the Bright Bodies (Savoye et al., 2005) materials were under a copyright and could not be modified, we identified the core principles and intervention objectives from the literature and used them to develop a workbook to accompany the iChoose program. We, then, established a curriculum subcommittee, composed of both researchers and community partners, to develop the workbook, based on those core principles and learning objectives. Themes for the intervention modules were reviewed and incorporated as individual chapters in the workbook. Six chapters were created, one for each intervention module. Following the family class format, the chapters were divided into content areas (sections) of Nutrition, Physical Activity (PA), and Behavioral Strategies. Each chapter included the module objectives (Table 4), educational content, a class activity, and homework. The subcommittee presented a first version of the workbook to the POPS-CAB to approve and/or make suggestions and followed this with two rounds of evaluation for readability, clear communication, and cultural appropriateness (Figure 1).

Table 4.

Sample of Perceptions That Leaded Workbook Changes and Adaptation.

| Chapter | Learning objectives | POPS/CAB feedback From CCI open questions | Delivering staff feedback From fidelity checklist | Parent/caregiver participant’s feedback From focus group | Workbook’s change—adaptations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall |

|

Include most of the intervention handouts in the workbook Change activities—Simplify to facilitate time management at classroom Change activities—Use “rounded” number to facilitate calculation |

|

Reorganized content to focus in one main message with is stated in the first paragraph Changed pictures for include more diverse ethnicity. Included most of the handouts as part of the workbook. Made the tracking sheets and goal settings as “tear out” without compromising the content (blank back) Added the Tips for You section Changed remained passive voice sentences to active voice |

|

| Chapter 1 |

|

|

|

|

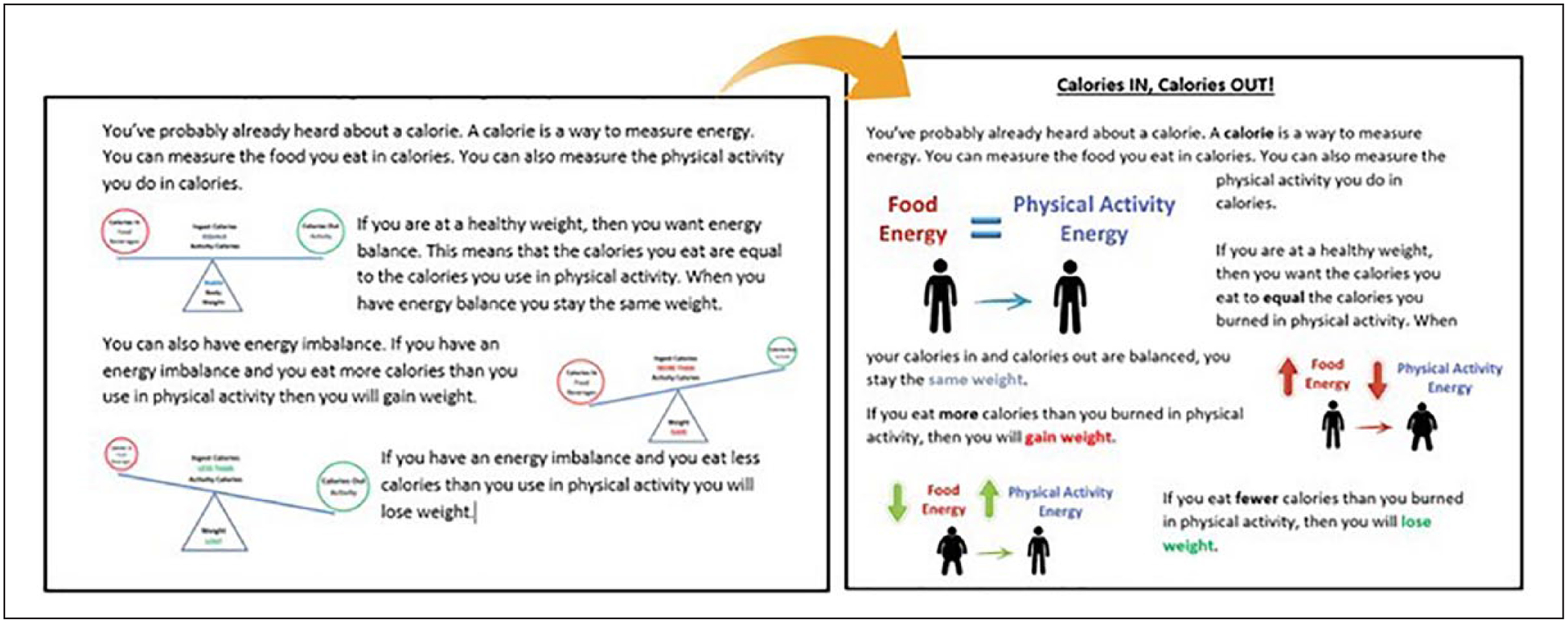

Changed energy balance content language (energy “in-burned” to “in-out”), and pictures (changed scale to body outlines) Reduced the SMART goals to kids |

| Chapter 2 |

|

|

Families were not using the tracking system. |

|

Made the tracking sheets and goal settings as “tear out” without compromising the content (blank back) Changed layout to include more pictures, less text dense and more colorful. Made a new adapted version of the excise pyramid which was more clear and included race variety images. Added legend to food pictures Added an annex section with health snacks options that are quick, easy and affordable. |

| Chapter 3 |

|

|

|

|

Changed “hand portion activity” to match the instructions and include race diverse pictures. Changed the Screen time section including all screen types no just TV and added a screen time calendar for families. Made the home environment quiz a “tear out.” |

| Chapter 4 |

|

Need to better outline ways to help to be successful. |

|

Added more information on label section including sugar and sodium (the “5/10 rule”), and ingredients information. Added more pictures illustrating recommended actions. |

|

| Chapter 5 |

|

None |

|

Included an appendix which exercises that families did in the exercise class (circuit), and also which exercise that could be done at home Improved bulling section by reducing content and focusing in strategies. Included in all sections a “recap” paragraph at the beginning of each chapter. |

|

| Chapter 6 |

|

|

Replace Desserts image with a culturally more appropriate image of health stress management methods such as those in the text next to the image. |

|

Replaced images with a culturally more appropriate image of health stress management methods. Review bullet list to contain less up to seven items. Reviewed content to be more goal based and focused in the family plan after the program. Kept lapse and relapse (strong language) to motivate the family planning for maintenance phase. Added more stress management tools for families. Included a family contract to stimulate parents keeping changes after program ends. |

Note. POPS = Partnering for Obesity Planning and Sustainability; CAB = community advisory board; CCI = Clear Communication Index.

Tools for workbook evaluation.

A readability evaluation of the workbook content was performed to ensure that the reading level was adequate to the proposed target population. The workbook writing aimed a fifth-grade reading level. To evaluate the reading level, we used five different measures of readability: Simple Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG; Fitzsimmons, Michael, Hulley, & Scott, 2010), Flesch-Kincaid Reading Level (FKRL; Kincaid, Fishburne, Rogers, & Chissom, 1975), FRY method (Fry, 1968), Coleman-Liau Grade Level (M. Coleman & Liau, 1975), and Flesh Reading Ease Score (FRES; Flesch, 1948). All measures were applied in a plain document with no pictures or tables included in the calculations. We decided to use different measures for readability because each one focused on a different aspect of the text (e.g., word and/or syllable count, sentence length). While readability scores provide an estimation of grade level necessary to read the material, however, those scores do not provide information on reading ease, prominence of main messages, behavioral strategies to initiate action, or cultural relevance, and thus, they can be misleading when determining the likelihood that materials clearly and effectively deliver information. Therefore, in addition to the readability tests we performed a more comprehensive assessment of written materials that explicitly addresses the degree to which information is clearly communicated to intervention participants. After a literature review, we decided to use the CCI (Baur & Prue, 2014) and the SAM (Doak, Doak, & Root, 1994). Both evaluations were conducted by POPS-CAB team members (n = 14).

The CCI (Baur & Prue, 2014) was developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to guide the development, implementation, and assessment of messages and written materials to make them easier for people to read, understand, and use. Items on the CCI aim to represent the most important characteristics to enhance clarity and aid people’s understanding of information. The CCI assesses materials in seven key areas divided into four parts: (a) Part A includes the main message and call to action, language, information design, and state of the science; (2) Part B evaluates the clarity of behavioral recommendations; (3) Part C focuses on the use of numbers and clarity of expressing numbers; while (4) Part D focuses on providing a clear description of associated risks of taking or not taking a certain action. Not all parts of the CCI are applicable to all written materials and depend on the presence or absence of information on behavioral goals, the use of numbers, or if risk factors are presented in the materials. The CCI consists of 20 items that produce a numerical score to objectively assess materials. The scores from each part were tallied to obtain an overall score (out of 100%), with a recommended standard of 90% or above to make materials easy to understand and use (Baur & Prue, 2014).

The SAM (Doak et al., 1994) enables reviewers to consider six categories: content, literacy demand, graphics, layout and typography, learning stimulation, and cultural appropriateness. The SAM’s score falls into one of three categories: superior, adequate, or not suitable. As the SAM is redundant, in some areas, to other assessment tools used in this study, we only used the SAM items related to cultural appropriateness, cultural images and examples, and strength of recommendation, which were not covered by the CCI.

Training and procedures for workbook evaluation and refinement.

POPS-CAB members (n = 16) completed training on the CCI and SAM evaluations. A daylong training was offered by a CDC expert and developer of the CCI instrument via videoconferencing, and a SAM presentation hosted by academic partners targeted local capacity development and shared learning between the partners. Trained POPS-CAB members (n = 14) were subsequently randomly assigned to conduct the evaluation individually on specific chapters of the workbook (two to three members per chapter). Six small groups composed of members of the research team (n = 7) and community partners (n = 7) that had individually assessed the respective chapters reconciled and consolidated their individual CCI ratings into a shared rating. During these small group sessions, POPS-CAB members used the materials to resolve differences in ratings. Across all groups, consensus on rating was achieved and used as the CCI value for the given chapters. As a group consensus, Parts A and B were applied to all chapters. Part C was pertinent to Chapters 1 to 3 and Part D was not pertinent to the material evaluated in this study.

Intended audience testing.

The workbook versions were pilot tested in the first and second wave of families enrolled in the iChoose program. During the first wave, the workbook was tested while it was being developed by the POPS-CAB curriculum subcommittee. At the end of the first wave, we revised the workbook and incorporated the initial feedback and results from Wave 1 creating a second version of the workbook. Parents and caregivers (Waves 1 and 2) had an average age of 40 years (SD = 8.5 years), were predominantly female (95%), with most having at least a high school education (91%), and nearly half having income less than US$25,000 (46%). In addition, participants completed the Newest Vital Sign (NVS) to assess HL and numeracy (Weiss et al., 2005). The NVS results in our sample indicated that approximately 34% of the parents and caregivers had low HL (Zoellner, Hill, Brock, et al., 2017).

Summative evaluation interviews (n = 38) and FGs (n = 11) were used to gather parent’s feedback on the workbook. Trained research personnel conducted both activities. The summative evaluation was completed with all parents who completed a postprogram assessment and included questions about satisfaction (e.g., “How satisfied were you with the parent workbook?) and usability (e.g., “How often did you use the workbook outside of the family class?”). For the FG, the curriculum subcommittee developed a script with CCI-based questions to guide the discussions for each workbook chapter following their objectives (e.g., “How well do you think these messages were explained in the workbook?,” “What things in the workbook helped you to better understand these messages?”). Eleven of 14 invited parents agreed to participate in the FG. To accommodate participant schedules, we conducted two small FGs and offered child care. FGs were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim to provide information on areas that contributed to potential workbook adaptations.

During the intervention period, fidelity checklists were also completed for each family class and included opportunities for delivery staff to provide comments about how the workbook was used during the sessions and if parents suggested adaptations. We collected all comments (open ended) related to the workbook from the fidelity checklists across two waves of intervention delivery for analysis.

Workbook revisions.

Following the first CCI evaluation, the curriculum subcommittee went through FG transcripts, field notes, delivery staff qualitative feedback, and CCI open ended questions, selecting quotes that indicate proposed changes. The findings were then summarized as a “proposed revision list” for each workbook chapter and chapter section (i.e., content area). The curriculum subcommittee then made adaptations to the workbook based on the revision list. The final documents were presented and reviewed by the POPS-CAB using an iterative process. Feedback from the POPS-CAB was used to confirm, correct, or clarify the changes made to the workbook.

Analysis

The quantitative data from instruments and surveys were analyzed in SPSS version 21, and analyses included frequencies, means, standard deviations, paired t tests, with results presented in tabular format. Individual and reconciled ratings were summarized and “within subjects” t tests were used to determine differences in individual and overall CCI and SAM ratings. Though the sample size of stake-holders was small, we also compared community and academic partner ratings to determine whether differences emerged in ratings. The transcripts from the FGs and qualitative portion of the forms were reduced to meaning units by the curriculum subcommittee and inductively categorized across the areas used to evaluate and improve the workbook chapters—representative quotes were provided within the results section indicated by quotation marks and italics (Table 3). All results are presented based on the initial version of the workbook used in Wave 1 (before) and the revised workbook (after) used in Wave 2.

Table 3.

Suitability Assessment of Materials Results Before and After Revisions.

| Suitability Assessment of Materials | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Cultural match in logic, language and experience | 2. Cultural image and examples | 3. Suitable for your population? | ||||

| Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | |

| Overall | Superior | Superior | Superior** | Superior** | 8* | 9* |

| Community | Superior | Superior | Adequate* | Superior* | 7*** | 9*** |

| Researchers | Superior | Superior | Superior | Superior | 9 | 9 |

Note: SAM = Suitability Assessment of Materials.

p < .1.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Results

Material Evaluation

Readability tests.

Readability tests revealed an overall workbook mean reading level to be at fifth grade. Table 1 shows results for all five tests performed in which no statistically significant changes were observed between tests conducted on the before revisions and on the after revisions. Variability between the measures of years of education required to understand the text showed results ranging from below fourth grade for SMOG (3.8) which considered the complexity of words (polysyllabic count), and seventh grade for Coleman-Liau (6.8) that considered the length of words (character count). In the Flesch Reading Score, where scores indicate on a scale of 0 to 100 how easy to read the material is, the overall result by chapters found it to be easy (80) to fairly easy (78). In addition, variability was found between chapters in ease of reading ranging from standard (62) to easy (80–86).

Table 1.

Readability Tests Results Before and After Revisions.

| Measure of years of education required to understand the text | Easiness to read | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMOG score (grade level) | Flesh-Kincaid score (grade level) | Fry score (grade level) | Coleman-Liau score (grade level) | Flesch reading ease score (0 very confusing; 100 very easy) | ||||||

| Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | |

| Overall | 3.8 | 3.8 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 6.7 | 6.8 | 80 | 78 |

| Chapter 1 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 6.1 | 5.8 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 7.3 | 6.9 | 74 | 77 |

| Chapter 2 | 4.2 | 3.8 | 6.1 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 7.1 | 7.5 | 75 | 62 |

| Chapter 3 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 85 | 84 |

| Chapter 4 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 4.3 | 4.6 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.8 | 6.3 | 86 | 83 |

| Chapter 5 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 5.1 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 6.9 | 7.0 | 82 | 81 |

| Chapter 6 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 6.9 | 6.9 | 80 | 81 |

Note: No significant differences between the first and second version of the materials were identified. SMOG = Simple Measure of Gobbledygook.

CCI.

The initial POPS-CAB CCI evaluation resulted in an overall score of 76% reflecting an inadequate clarity level (Table 2). Qualitative comments (e.g., need to address multiple main messages and include more ethnically diverse pictures) described in detail on Table 4 demonstrated the need for a revision. For the final product, the evaluation resulted in a significant improvement in overall rating with a score of 90% (p < .01), reaching the level where materials are considered to be clear (i.e., ≥90%). Both before and after revisions mean ratings were nearly identical between community and academic partners, as well as individual and group reconciled ratings. When considering results by workbook content area, overall ratings showed a mean increase of 19.2% (range = 5%–45%) across all chapters. Results also show improvement (μ = 13%) in all CCI component Parts. Changes to the clarity of Main Message (Part A) showed larger improvement (μ = 24%). Both before and after revisions, the workbook had strong Behavioral recommendations (Part B = 94%−100% across content area).

Table 2.

CCI “Within Subjects” t Test Results Before and After Workbook Revisions.

| CCI scores | Before (%) | After (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workbook CCI scores (n = 14) | ||||||

| Overall | 76** | 90** | ||||

| Community (n = 7) | 77* | 89* | ||||

| Researchers (n = 7) | 75* | 90* | ||||

| CCI scores by chapters (n = 14) | ||||||

| Chapter 1 | 49 | 94 | ||||

| Chapter 2 | 73 | 88 | ||||

| Chapter 3 | 57 | 87 | ||||

| Chapter 4 | 69 | 87 | ||||

| Chapter 5 | 83 | 85 | ||||

| Chapter 6 | 88 | 93 | ||||

| CCI components parts scores by workbook’s content area (n = 14) | ||||||

| A—Core/main message | B—Behavioral recommendations | C—Numbers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before (%) | After (%) | Before (%) | After (%) | Before (%) | After (%) | |

| Overall | 63** | 87** | 96** | 98** | 67** | 80** |

| Nutrition | 62* | 88* | 100 | 100 | 58 | 60 |

| Physical activity | 67* | 86* | 94* | 100* | 75* | 92* |

| Behavioral | 59** | 88** | 94 | 94 | 67** | 89** |

Note: CCI = Clear Communication Index.

p < .1.

p < .05.

SAM.

SAM results indicate that the cultural appropriateness of material remained rated as superior (μ = 2) before and after for overall results and when considered by research members (Table 3). However, community partner ratings for the Cultural Image and Examples went from adequate (μ = 1) to superior (μ = 2). Before the evaluation, most of the comments in the SAM’s comments section were related to improving pictures to “represent more race/ethnicities.” This improvement can be exemplified by comments left by community members after revision “Great improvement regarding different ethnicities/cultures.” Strength of recommendation was strong overall for both revisions (before = 8/10; after = 9/10).

Results from the FGs.

FGs revealed that the workbook accomplished its objectives and was easy to understand. They also reported that the workbook helped them rethink their behaviors and influenced them to promote health changes. Furthermore, parents reported that the written materials supported the other intervention components and was used as a reference resource. Finally, FGs also revealed workbook’s areas that needed improvement in format (e.g., more visual cues and separation of sections) and content (e.g., screen time focused in all types of media not only on TV) were also highlighted (Table 4).

Results from the fidelity checklist.

Delivery staff feedback revealed areas for improvement related to comprehension (e.g., difficulty in understanding energy balance) and format (e.g., Use “rounded” number to facilitate calculations). Table 4 shows sample of selected quotes by chapter from the transcripts and from the delivery staff feedback that influence changes in the workbook’s first version and Figure 2 provides a sample of changes.

Figure 2.

Sample of change in Chapter 1—Energy balance section based on qualitative feedback.

Results from the summative evaluation.

Data gathered from the parent/caregiver summative evaluation presented no significant difference between waves. Results indicated that parents felt satisfied with the workbook (μ = 9.2/10, SD = 1.08) and found it to be helpful (μ = 9.3/10, SD = 1.5), and agreed that was easy to find information that they need in the workbook (μ = 9/10, SD = 1.4). Lower rates were found about the usability with parents indicating that they did not often use the workbook outside the classes (μ = 3.5/10, SD = 1.4), did not often use the goal setting and tracking sheets (μ = 3.4/10, SD = 1.5), or think they will often use the workbook after the program ended (μ = 2.8/10, SD = 1.6). Qualitatively, parents indicated they liked that it was easy to read and follow, used plain simple examples, and thought the illustrations were nice. Parents reported lack of time, often due to work or other commitments, as the primary barrier to using the workbooks.

Discussion

We have described an iterative and systematic formative evaluation using a CBPR approach to develop, evaluate, and improve a childhood obesity workbook for parents of overweight children that used clear communication strategies to address key learning objectives. Because written materials are often used as an important intervention component (White et al., 2013), the main objective of this study was to offer a process guide for the development and evaluation of written materials using a collaborative approach. The study adds to the current literature by providing a process to combine available HL tools (White et al., 2013), such as the CCI evaluation system, SAM, and readability statistics using a CBPR approach.

We documented that the intervention materials developed for this study were written at a fifth-grade reading level which was below the average grade level required for our participants (>ninth grade; County Health Rankings & Roadmaps, 2015). The SAM ratings improved following revision in our study, primarily due to changes in community partner assessments. This is consistent with research on written materials targeting parents to prevent childhood obesity (White et al., 2013) where the findings from the SAM measure identified specific areas related to cultural appropriateness that reduced the overall suitability of materials in their original form. White et al. (2013) also documented superior ratings after making specific revisions in response to SAM scores. Common revisions in response to these scores included rewording passive sentences, enhancing the color schemes, reframing of health information to better coincide with typical reading patterns, and adding in culturally appropriate visuals (White et al., 2013).

This is the first study, to our knowledge, that incorporated the CCI in the evaluation of childhood obesity treatment materials for parents. The CCI added evaluative factors for written materials beyond readability statistics and cultural appropriateness, and provided actionable information to improve the original workbook materials. Consistent with Baur and Prue (Baur & Prue, 2014), revisions based on the CCI resulted in written materials that were rated higher than original materials. These changes are hypothesized to increase the likelihood of parents, regardless of their educational level, to identify and understand the main message, and interpret numbers in each workbook section. Unfortunately, this hypothesis cannot be directly tested with the current study due to the multicomponent intervention (e.g., changes in comprehension could be due to adaptations made to in-person class or telephone support sessions rather than due to workbook changes)—though this would be an excellent area for future research.

Our study findings also highlight the importance of moving beyond readability statistics as a sole indicator of the appropriateness of written materials for a given audience. It is of note that the results of the readability assessments did not change when comparing to the original and revised materials—both were ~5th-grade reading level. In contrast, both the CCI and SAM assessments provided actionable information for revisions and demonstrated significant improvements in ratings between the original and revised materials. Despite the finding that approximately 34% of the parents in our sample had limited HL (Zoellner, Hill, Brock, et al., 2017) and that 18% of the adults in the region lack basic literacy skills (National Center for Education Statistics, 2003), readability assessments would have suggested that the original materials were appropriate. However, readability scores do not provide information on reading ease, prominence of main messages, behavioral strategies to initiate action, or cultural relevance—as the CCI and SAM provide—and can be misleading when determining the likelihood that the materials clearly and effectively communicate intervention information (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2010). Therefore, the use of clear communication strategies has the potential to enhance program efficacy, perceived cultural relevance from community members, and satisfaction among participants.

The CBPR approach that actively engaged community partners in the workbook planning and adaptation process increased community capacity related to HL. Community members of the POPS-CAB played a critical role in the design and implementation of the written materials. Incorporating CAB feedback was important to develop clear and suitable materials for the regional childhood obesity treatment program. Their involvement in the interpretation and application of the evaluation findings also enhanced the quality of the materials while developed feelings of inclusion and ownership by community partners. The engagement of community partners in training on the CCI and SAM included the added value of increasing capacity in community members and may also lead and contribute to improved organizational HL and the quality of practice (Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 2001).

An interesting finding was the similarities between community and academic reviewers where the mean ratings were nearly identical while evaluating the communication strategies (CCI). However, the differences arouse in the evaluation of the cultural appropriateness where community reviewers indicated that they wanted to see more racial and ethnic representation in the images and examples despite highly rating the adequacy of the workbook. Based on that evaluation, the curriculum committee became aware and made sure to keep this aspect in mind while addressing participants’ requests (table 4) to add more pictures and food/recipes examples to the chapters. This example highlights how the CBPR approach influenced the changes to the content reflecting the community expertise of the local context. This input improved the cultural appropriateness of the materials, which otherwise could have been unnoticed by the researchers and readability tests.

Finally, to recognize and praise the significant time commitment of our community partners in the participatory evaluation process, our approach had an ongoing emphasis on optimizing the process, for example, by adapting to the resources available and determining the minimum data necessary for workbook development. At the same time, our community partners also indicated that they valued receiving specific details about detail the process, such as detailed reports by chapter of each indicator evaluated and perceptions that led to workbook changes and adaptation.

Our study included a number of limitations. First, we did not conduct a final round of FGs to assess the final version of the parent workbook. Although the use of the FG interviews in Phase 1 contributed to understanding of the problem from a reader-centered point of view, it was extremely labor and time intensive, including time needed to conduct the analysis collaboratively with community partners. Therefore, we decided not to conduct a second round of FGs after the final revisions because the materials showed a significant improvement and reached acceptable clear communication and suitability levels. Second, the sample size of CAB members that evaluated the documents before and after revisions was small. This is due to the nature of the study and our goal to report on the process of assessment and adaptation. Third, we developed the workbook and tested it within a multicomponent intervention, which does not allow for independent comparison of changes in the workbook with comprehension and study outcomes. Still, the findings provide a process for developing clear written materials for adults from an ethnically diverse, low income, and low literate community.

Conclusion

This article describes a CBPR approach to applying clear communication strategies in the development of childhood obesity intervention materials. The approach is driven by and tailored to community needs and involved contributions from individuals who would ultimately deliver the intervention and participants who have engaged with the intervention materials. We found that a process that included the engagement of community members and program participants in the development, evaluation, and revision of a program workbook to be both feasible to our CAB and staff and acceptable to potential participants who represented the target population. Our iterative process resulted in improved written materials that are written in an adequate grade reading level, clearly communicated the objectives of the program, and were culturally relevant while achieving a high satisfaction among users. The findings of this study suggest that, first, evaluative factors for written materials need to move beyond readability and include measures of the level of clarity of the messages and cultural appropriateness to provide actionable information to improve health information materials and that, second, an iterative process to intervention’s material development using clear communication strategies while involving community members, parents, and research partners may lead to workbook materials that are culturally relevant to the target audience, and better communicate program objectives.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledged the participation of our community partners from the Partnering for Obesity Planning and Sustainability (POPS) community advisory board for their collaboration on this research project and their generous feedback. Thanks to our community members Bryan E. Price, Ruby Marshall, and Kathryn Plumb who have greatly contributed with the workbooks development. Our extended gratitude to Donna Brock for her assistance with the workbook editing, focus groups, and feedback on earlier drafts of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Biographies

Fabiana A. Brito, PhD, MSPH, BSN, is a research assistant professor in the University of Nebraska Medical Center, College of Public Health Department of Health Promotion. She has expertise in health communication, cultural adaptation and program evaluation, implementation science, mixed quantitative-qualitative research approaches, and real world experience working in public healthcare systems serving underserved populations.

Jamie M. Zoellner, PhD, RD is an associate professor and registered dietitian in the Department of Public Health Sciences at the University of Virginia and the associate director of the Cancer Center Without Walls. Her research focuses on obesity and cancer, rural health disparities, health literacy, and engaging medically underserved areas in community-based participatory research.

Jennie Hill, PhD, is an associate professor in the Department of Epidemiology, College of Public Health at University of Nebraska Medical Center. She has 10 years of research experience in health disparate and rural communities and is experienced in community-based participatory research (CBPR) and family-based childhood obesity treatment programs.

Wen You, PhD, is an associate professor of both Agricultural and Applied Economics and Health Sciences, at Virginia Tech. She is invested in multidisciplinary scientific research and the focus of her research program has been to understand the economic causes of health disparities through the creative integration of economics and other disciplines.

Ramine Alexander, PhD, MPH, is an assistant professor of Food and Nutritional Sciences at North Carolina A&T State University. Her research focuses on using community-based approaches to develop interventions that target obesity-related behaviors in youth and adults.

Xiaolu Hou, MS, is recently graduated from Virginia Tech with an MS degree in Human Nutrition, Foods and Exercise. Her research focuses on improving the lives of others through evidence-based promotion of healthful eating and physical activity.

Paul A. Estabrooks, PhD, is the Harold M. Maurer distinguished chair of health promotion and professor in the College of Public Health at UNMC. He is an expert in implementation science methodologies and is widely recognized for his innovative views and work on mechanisms to develop interventions that combine internal validity with achieving large public health impact.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Ash T, Agaronov A, Young T, Aftosmes-Tobio A, & Davison KK (2017). Family-based childhood obesity prevention interventions: A systematic review and quantitative content analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14(1), Article 113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baur C, & Prue C (2014). The CDC Clear Communication Index is a new evidence-based tool to prepare and review health information. Health Promotion Practice, 15, 629–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Viera A, Crotty K, … Viswanathan M (2011). Health literacy interventions and outcomes: An updated systematic review. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment, 199(1), 1–941. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleich SN, Vercammen KA, Zatz LY, Frelier JM, Ebbeling CB, & Peeters A (2018). Interventions to prevent global childhood overweight and obesity: A systematic review. The Lancet: Diabetes & Endocrinology, 6, 332–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brach C, Keller D, Hernandez LM, Baur C, Parker R, Dreyer B, … Schillinger D (2012). Ten attributes of health literate health care organizations. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Retrieved from https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/BPH_Ten_HLit_Attributes.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Clear communication index user guide. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/ccindex/tool/index.html

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2010). Toolkit for making written material clear and effective. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, U.S. Department of Health & Human Resources. Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/Outreachand-Education/Outreach/WrittenMaterialsToolkit/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Chari R, Warsh J, Ketterer T, Hossain J, & Sharif I (2014). Association between health literacy and child and adolescent obesity. Patient Education & Counseling, 94, 61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhry S, McClinton-Powell L, Solomon M, Davis D, Lipton R, Darukhanavala A, … Burnet DL (2011). Power-up: A collaborative after-school program to prevent obesity in African American children. Progress in Community Health Partnerships, 5, 363–373. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman KJ, Tiller CL, Sanchez J, Heath EM, Sy O, Milliken G, & Dzewaltowski DA (2005). Prevention of the epidemic increase in child risk of overweight in low-income schools: The El Paso coordinated approach to child health. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 159, 217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman M, & Liau TL (1975). A computer readability formula designed for machine scoring. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60, 283–284. [Google Scholar]

- County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. (2015). County health rankings–Danville. Retrieved from http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/app/virginia/2015/rankings/danville-city/county/outcomes/overall/snapshot

- Doak C, Doak L, & Root J (1994). Suitability assessment of materials (SAM). Washington, DC: American Public Health Association. [Google Scholar]

- Economos CD, Hyatt RR, Goldberg JP, Must A, Naumova EN, Collins JJ, & Nelson ME (2007). A community intervention reduces BMI z-score in children: Shape Up Somerville first year results. Obesity, 15, 1325–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Economos CD, Hyatt RR, Must A, Goldberg JP, Kuder J, Naumova EN, & Nelson ME (2013). Shape Up Somerville two-year results: A community-based environmental change intervention sustains weight reduction in children. Preventive Medicine, 57, 322–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetters MD, Curry LA, & Creswell JW (2013). Achieving integration in mixed methods designs—Principles and practices. Health Services Research, 48(6, Pt. 2), 2134–2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimmons P, Michael B, Hulley J, & Scott G (2010). A readability assessment of online Parkinson’s disease information. The Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, 40, 292–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flesch R (1948). A new readability yardstick. Journal of Applied Psychology, 32, 221–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry E (1968). A readability formula that saves time. Journal of Reading, 11, 513–578. [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, & Rimer BK (1997). Theory at a glance: A guide for health promotion practice. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, & Parker EA (Eds.). (2013). Methods in community-based participatory research for health (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, & Becker AB (2001). Community-based participatory research: Policy recommendations for promoting a partnership approach in health research. Education for Health, 14, 182–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakob A (2001, February). On the triangulation of quantitative and qualitative data in typological social research: Reflections on a typology of conceptualizing “uncertainty” in the context of employment biographies. Paper presented at the Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum Qualitative Social Research. Retrieved from http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/981 [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RB, & Onwuegbuzie AJ (2004). Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher, 33(7), 14–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kincaid JP, Fishburne RP Jr., Rogers RL, & Chissom BS (1975). Derivation of new readability formulas (automated readability index, fog count and flesch reading ease formula) for navy enlisted personnel. Retrieved from https://stars.library.ucf.edu/istlibrary/56/

- Koh HK, Berwick DM, Clancy CM, Baur C, Brach C, Harris LM, & Zerhusen EG (2012). New federal policy initiatives to boost health literacy can help the nation move beyond the cycle of costly “crisis care”. Health Affairs, 31, 434–443. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucero J, Wallerstein N, Duran B, Alegria M, Greene-Moton E, Israel B, … White Hat ER (2018). Development of a mixed methods investigation of process and outcomes of community-based participatory research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 12, 55–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytle LA (2009). Examining the etiology of childhood obesity: The IDEA study. American Journal of Community Psychology, 44, 338–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maibach E, Rothschild M, & Novelli W (2002). Social marketing. In Glanz K, Rimer BK, & Lewis FM (Eds.), Health behavior and health education: Theory, research and practice (3rd ed., pp. 437–461). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Mantwill S, Monestel-Umaña S, & Schulz PJ (2015). The relationship between health literacy and health disparities: A systematic review. PLoS ONE, 10(12), e0145455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack L, Bann C, Squiers L, Berkman ND, Squire C, Schillinger D, … Hibbard J (2010). Measuring health literacy: A pilot study of a new skills-based instrument. Journal of Health Communication, 15(Suppl. 2), 51–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2003). National assessment of adult literacy. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/naal/

- National Institutes of Health. (2015). Clear communication. Retrieved from http://www.nih.gov/clearcommunication/

- Paasche-Orlow MK, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nielsen-Bohlman LT, & Rudd RR (2005). The prevalence of limited health literacy. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 20, 175–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plain Language Action and Information Network. (2010). Federal plain language guidelines. Available from http://www.plainlanguage.gov/

- Sanders LM, Federico S, Klass P, Abrams MA, & Dreyer B (2009). Literacy and child health: A systematic review. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 163, 131–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savoye M, Berry D, Dziura J, Shaw M, Serrecchia JB, Barbetta G, … Caprio S (2005). Anthropometric and psychosocial changes in obese adolescents enrolled in a Weight Management Program. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 105, 364–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (1992). Making health communication programs work (NIH Publication [92–1493]). Retrieved from https://www.cancer.gov/publications/health-communication/pink-book.pdf

- U.S. Department of Health Human Services and Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2010). National action plan to improve health literacy. Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Virginia Department of Health. (2008). Spatial analysis and high priority target areas. Retrieved from http://www.vdh.virginia.gov/health-equity/spatial-analysis-and-high-priority-target-areas/

- Virginia Department of Health. (2012). Virginia health statistics annual report. Retrieved from http://www.vdh.virginia.gov/HealthStats/documents/2010/pdfs/VDHS12.pdf

- Virginia Department of Health. (2016). Virginia medically underserved areas (VMUA). Retrieved from http://www.vdh.virginia.gov/content/uploads/sites/76/2016/06/VMUA.pdf

- Weiss BD, Mays MZ, Martz W, Castro KM, DeWalt DA, Pignone MP, … Hale FA (2005). Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: The newest vital sign. The Annals of Family Medicine, 3, 514–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RO, Thompson JR, Rothman RL, Scott AMM, Heerman WJ, Sommer EC, & Barkin SL (2013). A health literate approach to the prevention of childhood overweight and obesity. Patient Education & Counseling, 93, 612–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahnd WE, Scaife SL, & Francis ML (2009). Health literacy skills in rural and urban populations. American Journal of Health Behavior, 33, 550–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoellner JM, Hill JL, Brock D, Barlow ML, Alexander R, Brito F, … Estabrooks PA (2017). One-year mixed-methods case study of a community–academic advisory board addressing childhood obesity. Health Promotion Practice, 18, 833–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoellner JM, Hill JL, You W, Brock D, Frisard M, Alexander R, … Estabrooks PA (2017). The influence of parental health literacy status on reach, attendance, retention, and outcomes in a family-based childhood obesity treatment program, Virginia, 2013–2015. Preventing Chronic Disease, 14, Article E87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]