Abstract

Psychostimulant use disorders remain an unabated public health concern worldwide, but no FDA approved medications are currently available for treatment. Modafinil (MOD), like cocaine is a dopamine reuptake inhibitor, and one of the few drugs evaluated in clinical trials that has shown promise for the treatment of cocaine or methamphetamine use disorders, in some patient sub-populations. Recent structure-activity relationship and preclinical studies on a series of MOD analogs have provided insight into modifications of its chemical structure that may lead to advancements in clinical efficacy.

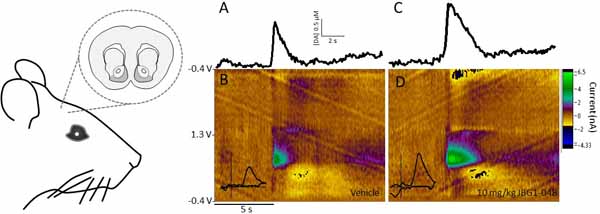

Here we have tested the effects of the clinically available (R)-enantiomer of MOD on extracellular dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens shell, a mesolimbic dopaminergic projection field that plays significant roles in various aspects of psychostimulant use disorders, measured in vivo by fast-scan cyclic voltammetry and by microdialysis in Sprague-Dawley rats. We have compared these results with those obtained under identical experimental conditions, with two novel and enantiopure bis(F) analogs of MOD, JBG1–048 and JBG1–049.

The results show that (R)-modafinil (R-MOD), JBG1–048, and JBG1–049, when administered intravenously with cumulative drug doses, will block the dopamine transporter and reduce the clearance rate of dopamine, increasing its extracellular levels. Differences among the compounds in their maximum stimulation of dopamine levels, and in their time course of effects were also observed. These data highlight mechanistic underpinnings of R-MOD and its bis(F) analogs as pharmacological tools to guide the discovery of novel medications to treat psychostimulant use disorders.

Keywords: cocaine use disorder, addiction, dopamine microdialysis, nucleus accumbens shell, fast scan cyclic voltammetry

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Psychostimulant use disorders continue to be a significant public health concern. Consumption of cocaine and methamphetamine, the two most abused psychostimulants worldwide, have continued to plague our communities and contribute to increasing overdose deaths. Statistical data describing “trends in prevalence” collected for the 2017 Monitoring the Future study show only a small increase in cocaine use from 8th to 12th grade students in the U.S. (Miech et al., 2018). Nevertheless, overdose deaths continue to rise (Seth et al., 2018). Some of these deaths have been the unintended result of cocaine tainted with the powerful opioid fentanyl, one of the primary drivers of the opioid epidemic in the U.S. (McCall Jones et al., 2017).

There are currently no FDA approved medication assisted treatment options for those who are addicted to psychostimulants (Czoty et al., 2016). Thus, there remains an unmet public health need for the development of medications and therapeutic strategies to assist this patient population in reducing the physiological and psychological harm posed by these drugs, with the ultimate goal of achieving long-term abstinence. Among the pharmacotherapeutics clinically tested as potential medications to treat cocaine and methamphetamine use disorders, modafinil (MOD; Provigil®) has shown promise (Dackis et al., 2005; Hart et al., 2008; Shearer et al., 2009). Although in a larger clinical trial the overall results were less convincing (Dackis et al., 2012), a subpopulation of patients who were addicted to cocaine without concurrent alcohol abuse, as well as those addicted to only methamphetamine without polysubstance use, responded positively to this clinically available medication (Anderson et al., 2009; Shearer et al., 2009; Kampman et al., 2015). These and other clinical studies suggest that the patient population who suffers from substance use disorders, like many other diseases, is diverse and that medications will likely need to be tailored to each patient population to be most effective for individuals seeking to discontinue their use of addictive drugs.

MOD and its (R)-enantiomer (R-MOD, Armodafinil, Nuvigil®) are approved by the FDA for specific medical conditions (Food and Drug Administration, 2007b; a), such as narcolepsy and sleep disorders, but they have also been used off-label for the treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and to improve symptoms related to excessive daytime sleepiness in patients with Parkinson’s Disease (Adler et al., 2003; Rodrigues et al., 2016). MOD is also used by healthy subjects, and especially by college students, to increase attention and cognitive function (Randall et al., 2005; Cakic, 2009; Partridge et al., 2011; Sahakian et al., 2015).

MOD and R-MOD show very low, if any, abuse liability even though their primary mechanism of action is to block the neuronal membrane dopamine (DA) transporter (DAT) preventing the physiological recycling of DA into its neurons, which results in an excess of synaptic DA (Mignot et al., 1994; Mereu et al., 2013, for review). Interestingly, this mechanism is shared by cocaine, although it has been demonstrated that the rapid increases in mesolimbic DA in response to cocaine exceed those produced by MOD, as measured by microdialysis in the nucleus accumbens shell (NAS) of mice (Loland et al., 2012). Indeed, there are only a few clinical case reports describing MOD abuse or dependence (Ozturk & Deveci, 2014; Krishnan & Chary, 2015). Preclinically, there is only one report that shows intravenous (i.v.) self-administration behavior maintained by MOD at levels higher than its vehicle in monkeys (Gold & Balster, 1996), while other reports show that MOD does not maintain self-administration behavior in rodents (Deroche-Gamonet et al., 2002; Heal et al., 2013). We have recently shown, in mouse microdialysis studies, how MOD and its (R)- and (S)-enantiomers affect DA levels in brain areas related to natural- and drug-induced reward (Loland et al., 2012; Mereu et al., 2017). Taken together, the results from these studies show MOD potential as a safe medication for psychostimulant use disorder, although its efficacy may be limited to a subpopulation of patients. The recent discovery of novel MOD analogs (Cao et al., 2011; Okunola-Bakare et al., 2014; Cao et al., 2016) is of interest because these compounds may be as safe as MOD, but with the potential of improved therapeutic effectiveness on a larger and more diverse population of psychostimulant-addicted patients than the parent compound. Since changes in NAS DA signaling have been linked to acute effects of abused psychostimulants (Pontieri et al., 1995; Aragona et al., 2008) and also of MOD and R-MOD (Murillo-Rodriguez et al., 2007; Loland et al., 2012; Mereu et al., 2017), herein our goal was to compare the effects of the novel (S)- and (R)-enantiomers of para-bis(F)MOD, (JBG1–048 and JBG1–049, respectively) to those of R-MOD. These compounds were evaluated in rat NAS for DA dynamics, release, and uptake, as measured by fast scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV) and time course changes in extracellular DA levels measured by brain microdialysis. Previous structure-activity relationship studies have demonstrated that para-bis(F) substituents were well tolerated on the (±)-MOD scaffold (Cao et al., 2011) (Fig. 1) and para-bis(F) groups can improve water solubility, which was an objective of our study due to the inherently poor solubility of R-MOD. These studies may provide further guidance toward the discovery of therapeutic strategies in treating psychostimulant use disorders.

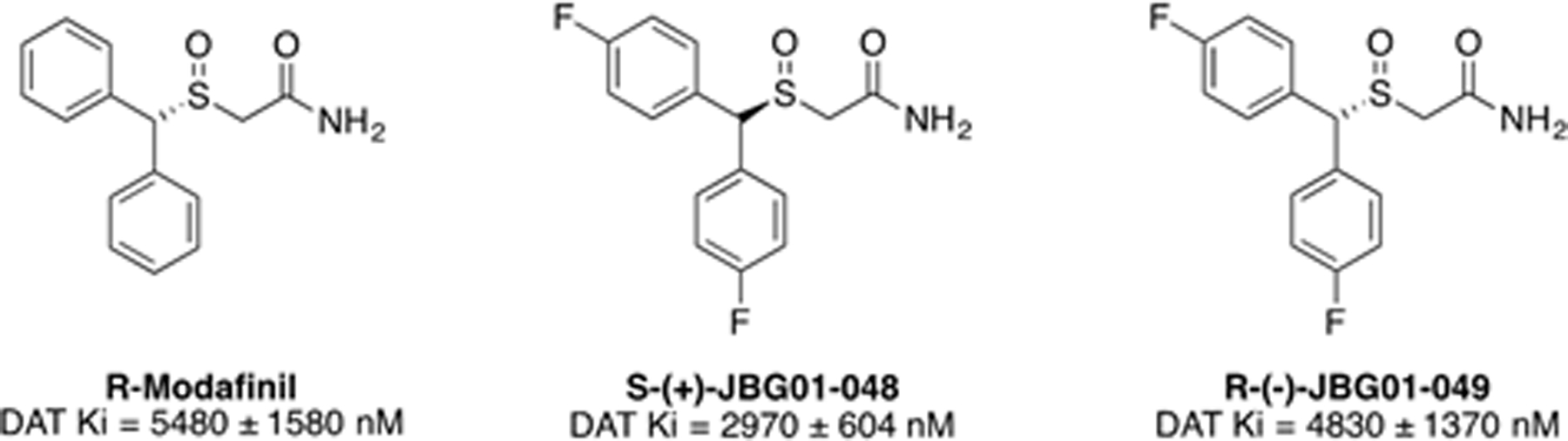

Figure 1:

Chemical structures and DAT binding affinities for R-MOD and the novel bis(F) analogs

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects.

Experimentally-naïve male Sprague-Dawley rats (CD sub-strain 001, Charles River, Wilmington, MA), 275–350g, were maintained in an environmentally-controlled vivarium. They were housed in pairs and habituated for at least one week before experiments. Experiments were conducted during the light phase of a 12-h cycle.

The animals in the present study were maintained in an AAALAC International accredited facility in accordance with NIH Policy Manual 3040–2, Animal Care and Use in the Intramural Program (released 1 November 1999). The present study was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Intramural Research Program, Baltimore MD, USA.

Compounds.

The compounds used in the present study were as follows: R-MOD was synthesized in the Medicinal Chemistry Section, NIDA-IRP as previously described (Prisinzano et al., 2004; Cao et al., 2011). (S)-(+)-JBG1–048, and (R)-(−)-JBG1–049 (Fig. 1) were prepared according to the experimental methods described in the Supplementary Materials and are referred to as JBG1–048 and JBG1–049 in the text. All compounds were dissolved in a vehicle containing DMSO, TWEEN-80 and sterile water (10, 15 and 75% v/v, respectively), and administered in a 2 ml/kg solution.

DAT radioligand binding in rat striatum

Tissue preparation.

Frozen brain striata dissected from male Sprague-Dawley rat brains (supplied in ice cold PBS buffer from Bioreclamation IVT (Hicksville, NY)) were homogenized in 10–20 volumes (w/v) of modified sucrose phosphate buffer (0.32M Sucrose, 7.74 mM Na2HPO4, 2.26mM NaH2PO4 adjusted to pH 7.4 at 25 °C) using a Brinkman Polytron (two cycles at setting 6 for 10 s each). The tissue was centrifuged at 20,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The pellet was suspended in cold buffer and centrifuged again using the same settings. The resulting pellet was resuspended in cold buffer at a concentration of 15 mg/mL OWW (original wet weight). On test day, all test compounds were freshly diluted in 30% DMSO and 70% H2O to a stock concentration of 1 mM or 100 µM. Each test compound was then diluted into 10 half-log serial dilutions using 30% DMSO vehicle.

Radioligand competition experiments.

Experiments were conducted in 96-well plates containing 50 µL of diluted test compound, 300 µL of fresh binding buffer, 50 µL of radioligand diluted in binding buffer ([3H]-WIN35,428: 1.5 nM final concentration; ARC, Saint Louis, MO) and 100 µL of tissue preparation (2 mg of brain striatum membranes per well). Non-specific binding was determined using 10 µM Indatraline and total binding was determined with 30% DMSO vehicle. The reaction was started with the addition of the tissue. All compound dilutions were tested in triplicate and the reaction incubated for 120 min at 4 OC. The reaction was terminated by filtration through Perkin Elmer Uni-Filter-96 GF/B, presoaked for 120 min in 0.05% polyethyleneimine, using a Brandel 96-Well Plates Harvester Manifold (Brandel Instruments, Gaithersburg, MD). The filters were washed 3 times with 3 mL (3 × 1 mL/well) of ice-cold binding buffer. 65 µL Perkin Elmer MicroScint20 Scintillation Cocktail was added to each well and filters were counted using a Perkin Elmer MicroBeta Microplate Counter (calculated efficiency: 34.8%).

Binding data analysis.

IC50 values for each compound were determined from dose-response curves and Ki values were calculated using the equation by Cheng and Prusoff (1973); Kd value for [3H]- WIN35,428 (28.2 ± 1.07 nM) was determined via separate homologous competitive binding experiments. These analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 6.00 for Macintosh (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Ki values were determined from at least 3 independent experiments and are reported as mean ± SEM.

FSCV procedures

FSCV Surgery

Previously jugular catheterized (see below for details) Sprague-Dawley rats (300–330g) were anesthetized with 1.2 g/kg (i.p.) urethane in sterile saline and given boosters of one third the original dose until properly anesthetized. Rats were placed in a stereotaxic apparatus where the skull was exposed, and four small holes were drilled to expose the dura. Rats were then implanted with a bipolar tungsten stimulation electrode [uncorrected coordinates (Paxinos & Watson, 1998), posterior −4.6 mm, and lateral ±1.0 mm from bregma, and ventral −6.5 from dura]; the stimulation electrode was tested by applying a train of 24 pulses of 180 µA, 60 Hz, 4 ms in duration which produced a detectable movement of the whiskers. A carbon-fiber microelectrode (CFME) working electrode was slowly lowered to its final position in the ipsilateral hemisphere (anterior +1.7, lateral ±0.8, ventral −7.0 to −8.0) while testing the DA response to stimulus as the electrode was lowered to its final position, assuring a location with a robust DA signal was found. An Ag/AgCl reference electrode secured by a screw was implanted in the contralateral hemisphere. At the conclusion of the experiment the electrode placement was marked by applying 10 V cathodically for 30 s to the working electrode.

Electrochemistry

DA was detected with a cylindrical glass sealed CFME (Huffman & Venton, 2009). The CFME was created by enclosing a carbon fiber (0.007 mm diameter; Goodfellow Cambridge Limited, Huntingdon, England, UK) in a borosilicate glass capillary tube (1.2 mm o.d.; A-M Systems, Sequim, WA, USA) and then pulled to a tapered point with a micropipette puller (Narishige, Tokyo, Japan). The carbon fiber was cut, extending 100 µm past the tapered end, and pre-calibrated in vitro with known concentrations of DA. DA was identified via FSCV with a triangular waveform scan from −0.4 to 1.3 V at 400 V/s with a holding potential of −0.4 V. During the experiment a stimulus of 24 pulses of 180 µA, 60 Hz, 4 ms in duration was applied at five-minute intervals. Data was collected using a UEI potentiostat and breakout box running Tarheel-CV (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill electronics shop) using a pair of Digitimer Neurolog NL800A (Digitimer North America LLC, Ft. Lauderdale, Fl. USA) current stimulus isolators to control the stimulation. The presence of DA was confirmed by cyclic voltammogram produced by the peak after stimulation. See also Supplementary Figure 1.

Histology

At the end of the experiment rats were euthanized with an excess of urethane and an electrolytic lesion was created by applying a cathodic current to the electrode in place, brains were removed and fixed in a 4% formalin solution. Following fixation brains were transferred to a 30% sucrose solution for several days before being sectioned (30 µm slices) with a cryostat (Leica Biosystems, Richmond, Il). Sections were mounted and stained with cresyl violet, placement in the NAS was confirmed by the location of the electrolytic lesion in relation to anatomical landmarks.

FSCV Data Analysis

Amperometric data recorded by each stimulus was analyzed using HDCV (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill) to determine the concentrations of the chemical components contributing to the stimulated peak (Bucher et al., 2013) (See also Supplementary Figure 1). The DAMax and DA clearance rate were determined by using a custom macro written in Igor Pro (Wavemetrics) which identified peaks greater than 3 X root mean square noise and fit the descending portion of the peak to equation 1 (Sabeti et al., 2002; Berglund et al., 2013).

| (1) |

Data were analyzed for significance using a two-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni post-hoc test analysis.

Microdialysis procedures

Surgeries.

Probes had an active dialyzing surface of 1.8–2.0 mm, and were implanted into the NAS in Sprague Dawley Rats (290–330 g) during surgical procedures [uncorrected coordinates (Paxinos & Watson, 1998): anterior = + 2.0 mm, and lateral = ± 1.0 mm from bregma; ventral = −7.9 mm from dura] performed under a mixture of ketamine and xylazine anesthesia, 60.0 and 12.0 mg/kg intraperitoneally (i.p.), respectively, as described (Tanda et al., 2005; Tanda et al., 2007; Tanda et al., 2013). A silastic catheter was implanted into the right external jugular vein during the same surgery session as described (Tanda et al., 2008; Garces-Ramirez et al., 2011). Post-surgical care included animal observation for pain or distress, with topic and/or systemic delivery of analgesics, and a subcutaneous injection of saline solution to replenish body fluids, as approved by NIDA-IRP ACUC. Animals recovered overnight in hemispherical CMA-120 cages (CMA/Microdialysis AB, Solna, Sweden) equipped with overhead quartz-lined fluid swivels (Instech Laboratories Inc., Plymouth Meeting, PA) for connections to the dialysis probes. All tests were conducted in these cages.

Sample collection

Approximately 22–24 hours after probe implantation, Ringer’s solution (Di Chiara et al., 1996; Tanda et al., 2007) was delivered to the probes at 1.0 µL/min, and dialysates (10µL) were collected every 10 min and immediately analyzed. After reaching stable DA values (2–4 consecutive samples, <10% variability), different groups of rats received a treatment of either R-MOD, JBG1–048, JBG1–049, or vehicle. The treatments were intravenously administered in incremental (cumulative) doses, each being 30 minutes apart. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was sampled every 10 min for the entire time course after drug treatments.

Analytical Procedure

DA was detected in dialysate samples by high-performance liquid chromatography (Tanda et al., 2008) coupled with a coulometric detector (5200a Coulochem II, or Coulochem III, ESA, Chelmsford, MA, USA). Potentials for the oxidation and reduction electrodes of the analytical cell (5014B; ESA) were set at +125 mV and −125 mV, respectively. The mobile phase, containing 100 mM NaH2PO4, 0.1 mM Na2EDTA, 0.5 mM n-octyl sulfate, and 18% (v/v) methanol (pH adjusted to 5.5 with Na2HPO4), was pumped by an ESA 582 (ESA) solvent delivery module at a flow rate of 0.50 ml/min. Assay sensitivity for DA was 2 fmoles per sample.

Histology

At the end of the experiment, rats were euthanized by pentobarbital overdose, brains were removed and left to fix in 4% formaldehyde in saline solution. Brains were sliced, using a vibratome (Vibratome Plus, The Vibratome Company, St. Louis, MO), in serial coronal slices oriented according to Paxinos and Watson (1998) in order to identify the location of the probes. Data were only used from subjects with probe tracks within the correct NAS boundaries.

Behavioral activity

Activity was assessed with a TSE InfraMot system (TSE Systems, Bad Homburg, Germany) which uses infrared sensors to record behavioral activities of the subject by sensing infrared radiation from its body and spatial displacement over time. The sensor assembly was mounted on the top of the microdialysis test chamber, and data was automatically collected in spreadsheets from an interfaced computer. The collected data provides a relative measure of the duration and intensity of the activity. The scanning interval was set to 5 min. The first 30 min of activity counts after each drug-dose/vehicle administration were analyzed.

Data analyses.

Microdialysis data were expressed as the percentage of basal DA values, and behavioral activity data were expressed as activity counts during the first 30 minutes after vehicle/drug administration. Results are expressed as group means (± SEM). Statistical analyses were carried out using one- and two-way ANOVA (factors: time, and drug-dose) for repeated measures over time (only for microdialysis data) with significant results subjected to post-hoc Tukey`s test.

RESULTS

In Vitro binding experiments

DAT binding affinities for R-MOD and the bis(F)-analogues JBG1–048 and JBG1–049 are shown in Fig. 1. The addition of the para-F substituents had little effect on DAT binding, with all three compounds showing low micromolar affinities. We previously reported that the racemic bis(F)-analogue had a similar DAT affinity to (±)MOD (Cao et al., 2011).

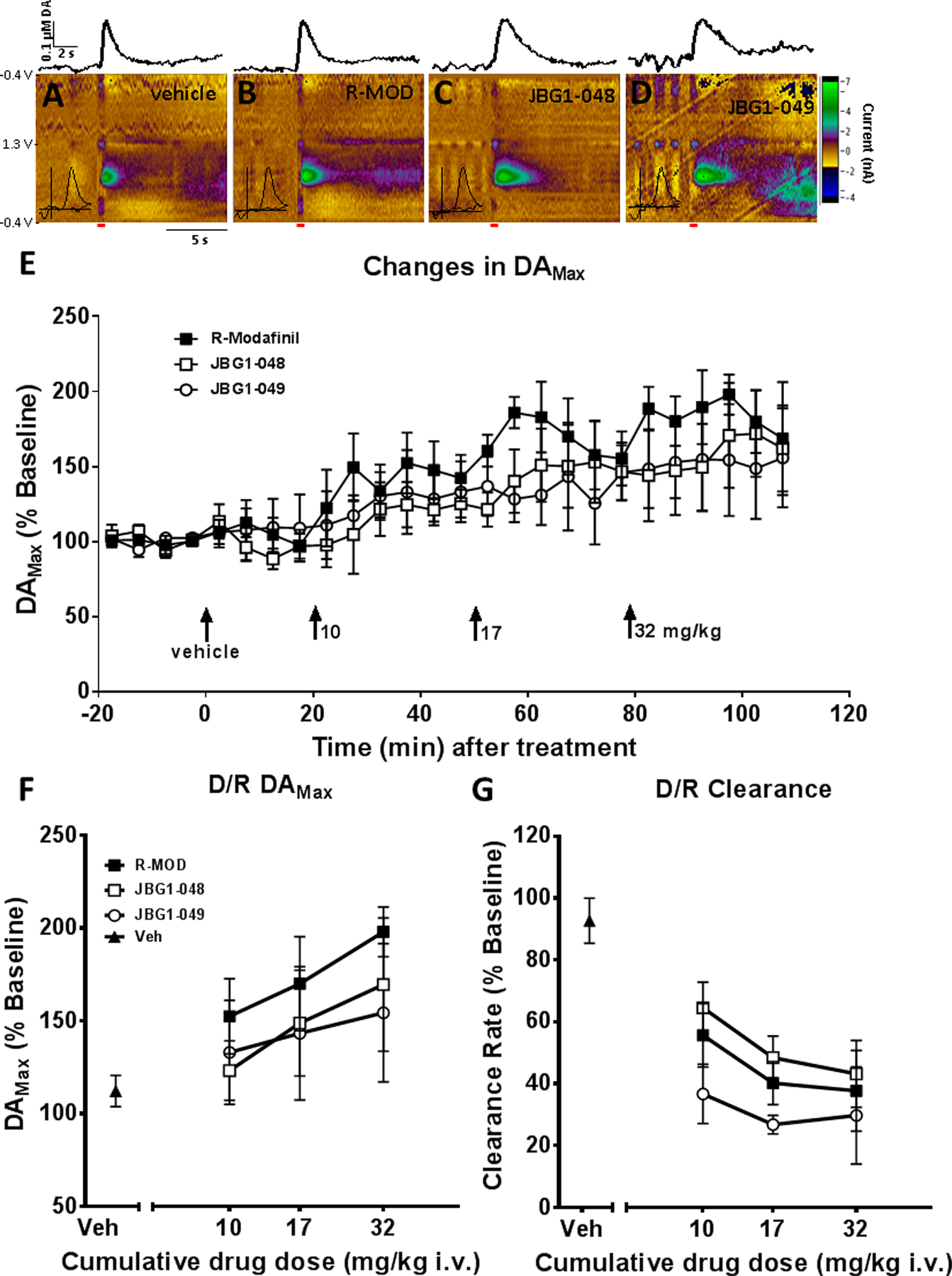

Fast scan cyclic voltammetry

FSCV was used to measure the sub-second dynamics of extracellular DA in the NAS following stimulation. These experiments conducted in urethane anesthetized rats using an electrical stimulation allowed for the detection of changes in elicited DA release and the function of DAT with a uniform stimulus across animals and doses of each compound. Figure 2A-D shows representative colorplots from rats receiving 2 ml/kg vehicle (i.v.), or 17 mg/kg (i.v.) of R-MOD, JBG1–048 or JBG1–049. In each case, the extracellular DA concentration rapidly rises after the stimulation begins, and then is cleared from the extracellular space, largely through the DAT. The inset cyclic voltammogram (CV) of each panel confirms the elicited substance as DA while the amplitude and duration of each DA stimulation shows the effect of each compound on the phasic properties of DA in the NAS of individual rats. The time course of the effects of cumulative dosing on DAMax for each compound is shown in Figure 2E. The vehicle used to administer R-MOD, JBG1–048, and JBG1–049 had no significant effect on either DAMax or the clearance rate. Each dose of compound resulted in a corresponding increase in DAMax, with R-MOD having a slightly greater impact than either bis(F) analog. Figure 2F shows the effect of each compound on the maximum elicited DA peak or DAMax once the maximal effect of each dose was detected. The time point approximately 17.5 min after i.v. administration was chosen to generate dose-response curves. This point represented the largest changes from baseline values across the compounds and doses tested. The 17 mg/kg dose of R-MOD was the one exception to this trend showing a maximal increase after 7.5 min; to keep the analysis consistent, the same time point was used for all cumulative dosing analyses. All of the compounds tested were able to increase DAMax in a dose-dependent manner, with no significant difference between JBG1–048 and JBG1–049 and the parent compound. The maximal effect was seen in the first 5–10 min post injection with DAMax rising to 150–200% of baseline values. No significant difference was found between R-MOD and either of the bis(F) analogs (ANOVA, F1,18=1.724, p=0.2056, F1,18=1.711, p=0.2074, for JBG1–048 and JBG1–049 respectively). The same data set was used to calculate the rate of DA clearance from the electrode after the elicited DA release (Figure 2G). Here, each compound significantly lowered the rate of DA clearance over vehicle alone, demonstrating a blockade of DAT. Both of the bis(F) analogs decreased the clearance rate with the same efficacy as R-MOD, reducing the clearance rate by 50% or more. The maximal effect was seen in the first 10–15 min post injection with the clearance rate falling to 30–60% of baseline values. Again, no significant difference was found between R-MOD and either bis(F) analog (ANOVA, F1,18=0.9146, p=0.3516, F1,16=2.39, p=0.1417, for JBG1–048 and JBG1–049 respectively), though JBG1–049 did have slightly lower DA clearance rate at the doses tested.

Figure 2:

FSCV analysis of cumulative dosing experiments with R-MOD and each bis(F) analog. (A-D) Representative colorplots from individual animals showing the effects of the vehicle (10% DMSO, 15% Tween), and 17 mg/kg of R-MOD, JBG1–048, and JBG1–049. Inset into each colorplot is the CV corresponding to the peak oxidation wave indicating the presence of DA. Above each colorplot is the corresponding plot showing the change in DA concentration over time. The time and duration of stimulation is indicated by the red bar. (E) The time course of the cumulative dosing experiment for DAMax showing a change in elicited DA with dose of DAT inhibitor after an initial baseline period and vehicle treatment. (F) Cumulative dose-response curves showing the effect of each compound on DAMax with doses of 10–32 mg/kg (i.v.). The peak effect across doses and compounds was found to after 15 min, which was used to generate the dose-response curve. (G) Cumulative dose-response curves showing the effect of each compound on the rate of DA clearance from the electrode. The greatest effect of each dose was found to be after 15 min for each compound which was used to generate the dose-response curve.

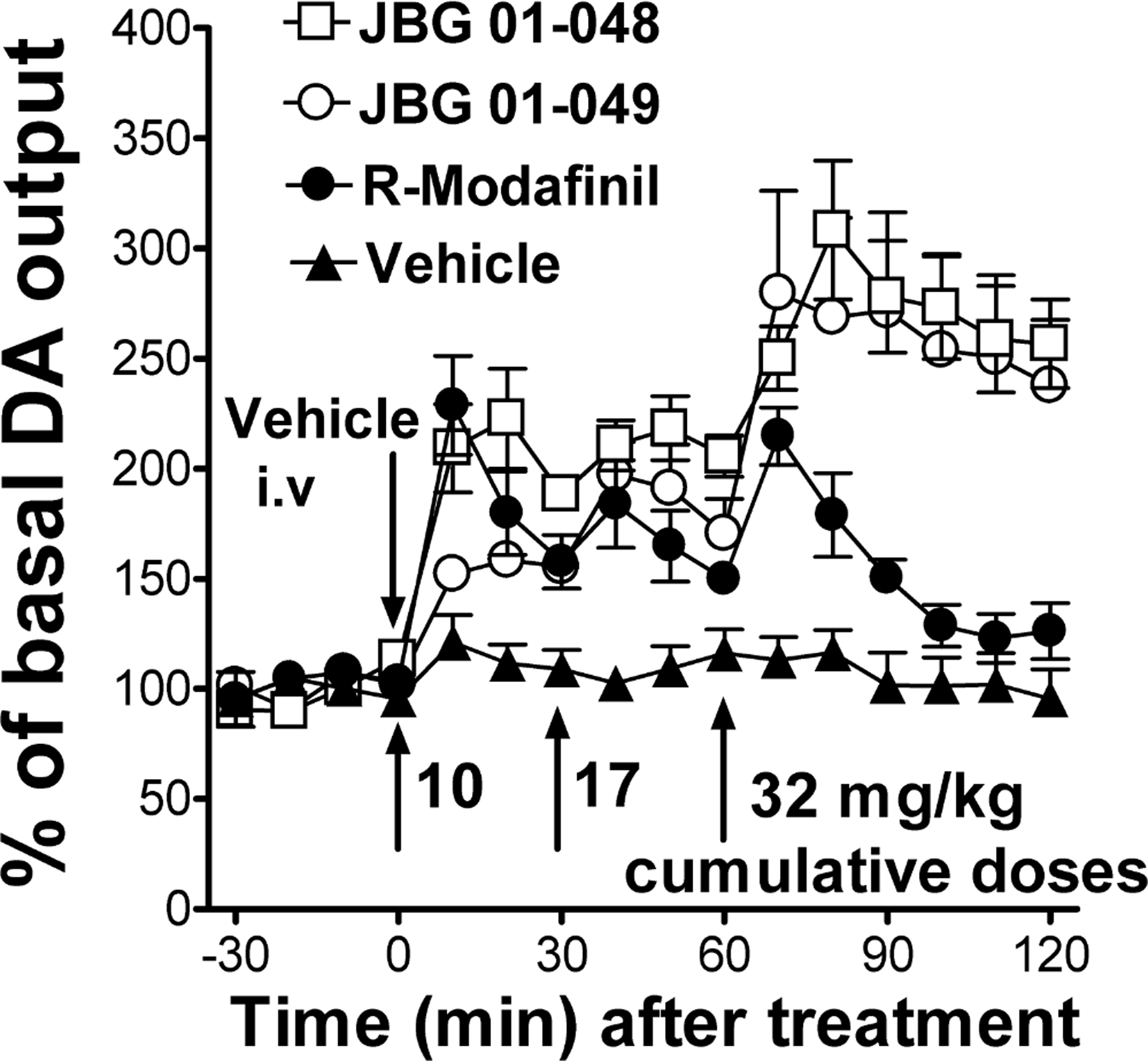

Brain microdialysis.

The average basal DA level found in dialysates from the NAS in the present experiments was 47.33 ± 6.5 fmoles (±S.E.M.) per 10 µl sample, n=22. No significant differences (p>0.05) were found in basal DA concentrations across the different experimental groups (ANOVA, F3,18 = 0.533, p=0.665).

Intravenous administration of cumulative doses of R-MOD, 10–32 mg/kg, induced a rapid increase in DA levels in dialysates from the NAS (two-way ANOVA: main effect Dose: F2,12 = 0.624, p=NS; main effect Time: F3,36 = 61.47, p<0.001; Time X Dose interaction: F6,36 = 1.061, p=NS) (Figure 3). The maximum increase in DA, ≈ 220% of basal values, was obtained 10 min after receiving the 10 and the 32 mg/kg doses (Figure 3 and 4A). The effects of R-MOD on DA levels rapidly dissipated following the last treatment dose.

Figure 3:

Time course of effects of intravenous administration of cumulative doses (10–32 mg/kg) of R-MOD, JBG1–048, JBG1–049, or their vehicle (2ml/kg) on DA levels in dialysates from the NAS. The first drug-dose was administered at time=0. Subsequent doses were then administered 30 min apart. The results suggest a slower onset of effects on DA levels for JBG1–049 compared to the other tested drugs. Also, R-MOD effects on DA levels appear to dissipate more rapidly compared to the JBG-compounds. Results are means, with vertical bars representing SEM, of the amount of DA in 10-min dialysate samples, expressed as percentage of basal values, uncorrected for probe recovery.

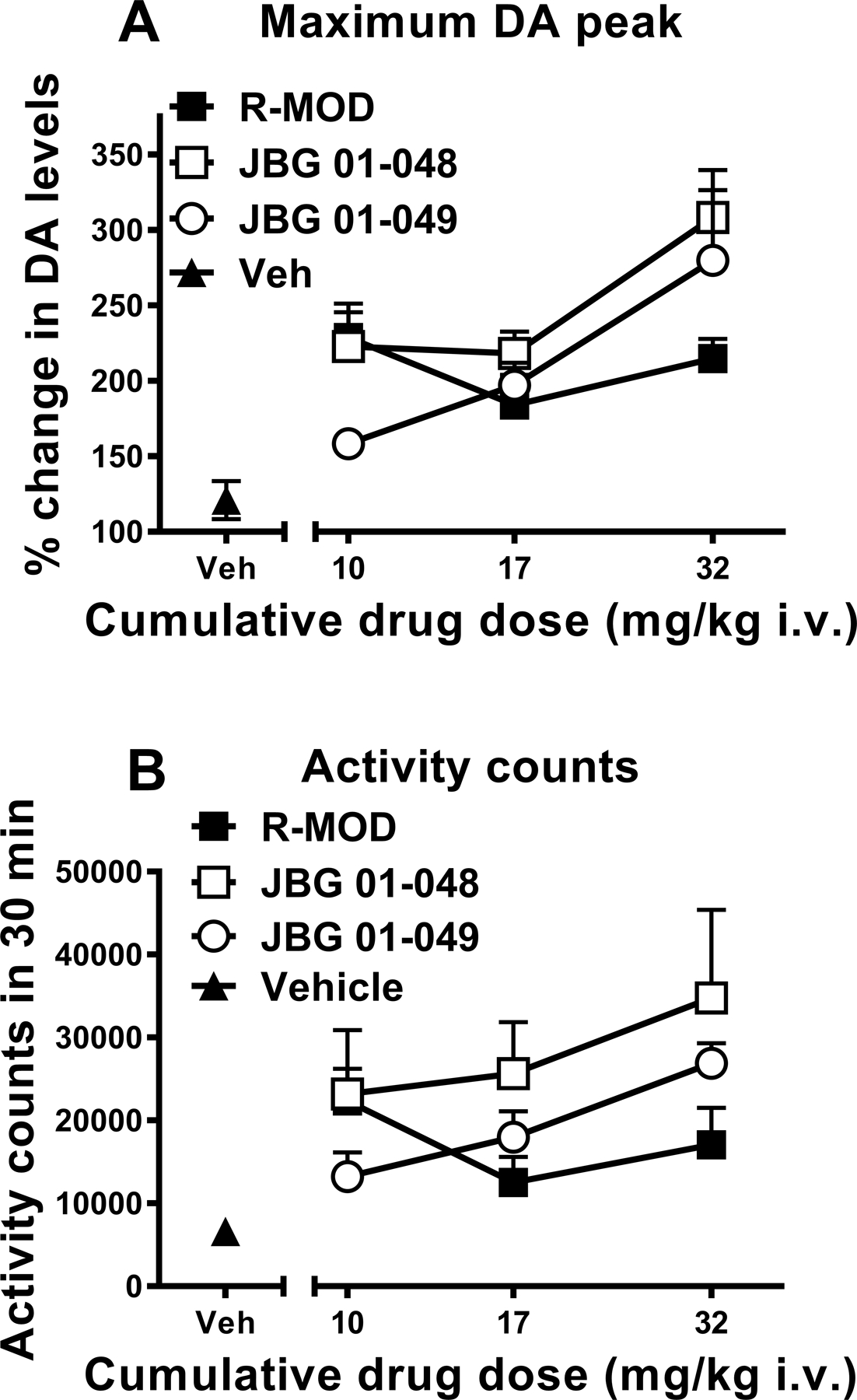

Figure 4:

Panel (A): Maximum increase in DA levels in dialysates from the NAS in rats obtained following intravenous administration of cumulative doses (10–32 mg/kg) of R-MOD, JBG1–048 and JBG1–049, or their vehicle (2ml/kg). The effects of R-MOD resemble those already reported for MOD and its enantiomers in mice (Loland et al., 2012), where the slope of the dose-response curve was shallow as compared to that for a widely abused psychostimulant like cocaine. Results are means, with vertical bars representing SEM, of the amount of DA in 10-min dialysate samples, expressed as percentage of basal values, uncorrected for probe recovery.

Panel (B): Behavioral activity counts obtained during the first 30 minutes after each intravenous administration of cumulative doses (10–32 mg/kg) of R-MOD, JBG1–048 and JBG1–049, or their vehicle (2ml/kg). Our results show that the pattern of changes in behavioral effects related to these drugs appears similar to the pattern of changes in maximum increase in DA levels obtained with the same cumulative drug doses shown on panel A.

Administration of cumulative doses of JBG1–048 and JBG1–049, 10–32 mg/kg (i.v.), elicited a dose dependent, significant stimulation in DA levels in NAS dialysates (JBG1–048, two-way ANOVA: main effect Dose: F2,15 = 7.026, p<0.01; main effect Time: F3,45 = 90.55, p<0.001; Time X Dose interaction: F6,45 = 3.817, p<0.01; JBG1–049, two-way ANOVA: main effect Dose: F2,15 = 5.301, p<0.02; main effect Time: F3,45 = 31.40, p<0.001; Time X Dose interaction: F6,45 = 3.735, p<0.01) (Figure 3). JBG1–048 resulted in a greater increase in DA levels than JBG1–049 after administration of the 10 mg/kg dose (≈ 220% vs 150% increase, respectively) (Figure 4A), while DA increased to similar levels following the administration of the highest dose (32 mg/kg) of both bis(F) enantiomers, JBG1–048 and JBG1–049 (Figure 3). Additionally, administration of the 32 mg/kg dose for both JBG1–048 and JBG1–049 elicited similar maximum increases in DA levels (308% VS 279% increase, respectively), which were also greater than those obtained by R-MOD at the same dose (Figure 4A). Also, DA levels still exceeded 200% of baseline for both the bis(F) analogs of MOD at 1 hour after the administration of the last drug dose.

Behavioral activity.

All drugs elicited a dose dependent increases in activity counts as compared to those elicited by the vehicle (ANOVA, F 3,23=6.402, p<0.005; F 3,20=7.03, p<0.005; F 3,26=14.45, p<0.005, for R-MOD, JBG1–048, and JBG1–049, respectively; Figure 4B). The administration of cumulative doses of R-MOD produced its maximum effects on activity counts during the first 30 minutes following administration of the 10 mg/kg dose, while under the same conditions the bis(F) analogs (i.e. JBG1–048 and JBG1–049) produced their maximum effects at the highest dose tested, 32 mg/kg (Figure 4B).

DISCUSSION

Our results show that administration of R-MOD and its (S)- and (R)-bis(F)enantiomers, JBG1–048 and JBG1–049, respectively, significantly increase the levels of extracellular DA in dialysates from the NAS. This effect is likely due to a blockade of DAT, as evidenced by the significant reduction in DA clearance rates obtained from the voltammetry experiments and their comparable binding affinities at DAT.

The microdialysis experiments also show that the time course for the changes in DA levels obtained after administration of all the tested compounds did not fully overlap. For instance, the onset of effects on DA levels elicited by administration of the first dose of JBG1–049 were slightly delayed compared to effects elicited by R-MOD and JBG1–048. Additionally, after the highest drug-dose injection, the offset of R-MOD effects on DA levels occurred at earlier time points than with the other drugs. DA levels approached basal values from about 40 min after injection of the highest R-MOD dose. The offset of effects of the bis(F) analogs on DA levels was slower than that observed for R-MOD. DA levels were still at about 200% of basal values 1 hour after administration of the last, highest dose of the bis(F) analogs. This rapid dissipation of R-MOD effects on DA levels might explain its lower stimulation of DA levels when compared to the effects of its bis(F) analogs after administration of cumulative drug doses. Indeed, a reduced accumulation of the drug, i.e. due to a faster metabolism or excretion, would potentially reduce its effects. However, such faster offset is not apparent when comparing the (similar) DA levels obtained with its bis(F) analogs during the last time-point (time=30 and 60 min) after administration of the low and intermediate drug-doses. Taken together, our microdialysis results suggest that under the present experimental conditions differences in the pharmacokinetics and/or pharmacodynamics of R-MOD compared to the bis(F) analogs might lead to distinct outcomes in stimulating extracellular DA levels in the NAS, with R-MOD showing an unexpectedly faster offset of DAergic effects compared to its bis(F) analogs (Zolkowska et al., 2009; Loland et al., 2012).

The effects of R-MOD and both bis(F) analogs in the FSCV experiments on both the DAMax and DA clearance rates, suggest that each are able to alter both the reuptake rate of DA by blocking the transporter and increase the concentration of DA produced by the stimulus, as seen in Figure 2E-G. While there is a trend for R-MOD to produce higher DAMax values, and for JBG1–049 to produce lower rates of DA clearance, neither of these two effects were found to be significant.

A reduction in the clearance rate by DAT inhibitors has been published several times (Jones et al., 1995; Venton et al., 2006; Ramsson et al., 2011). R-MOD and both bis(F) analogs had similar effects on the clearance rate, which may relate to their similar affinities for DAT (Figure 1), though JBG1–049 had a slightly higher impact on the clearance rate at the lowest dose of 10 mg/kg, while JBG1–048 was very similar to R-MOD over the entire dose range. At a dose of 32 mg/kg all three inhibitors decreased the clearance rate as much as a large dose of amphetamine (20 mg/kg) or cocaine (40 mg/kg) (Ramsson et al., 2011). The similar effects of the two bis(F) analogs and R-MOD indicate that the structural changes made to the compound had little effect on their availability or ability to bind to the DAT as compared to R-MOD. This also indicates that the differences in stereochemistry between the two bis(F) analogs are not critical for their interactions with the DAT.

JBG1–048 and JBG1–049 had similar, but not quite as large, effects on DAMax as R-MOD, which is also consistent with their similar binding affinities for DAT. Each inhibitor dose dependently increased the DAMax up to 150–200% of the original baseline, with the largest dose being 32 mg/kg. A similar, but much larger trend has been found for amphetamine and cocaine in the ventral striatum of similarly urethane anesthetized rats (Ramsson et al., 2011). In comparison, R-MOD, JBG1–048 and JBG1–049 had a much lower effect on the elicited DA peak, which may relate to the differences in preferred DAT conformation (compared to cocaine). Additionally, this effect can be explained because R-MOD, JBG1–048, and JBG1–049 are DAT inhibitors and are not substrates (e.g. amphetamine), which cause DA release from the presynaptic terminals. The similarities in the effects on DAMax between R-MOD and the two bis(F) analogs may also indicate that the changes made to the chemistry of R-MOD did not, in this case, change the nature of how the analogs interact with the DAT. Neither JBG1–048 or JBG1–049 produced an increase in DAMax above the level produced by R-MOD, indicating that they likely have the same effects on the DAT as R-MOD.

In this study, the effects on tonic and phasic DA in the NAS were examined. Even though lower levels of extracellular DA might have been reported for the NAS compared to other striatal areas (Di Chiara et al., 1993; Kalivas & Duffy, 1995; Jones et al., 1996; Aragona et al., 2008), its response to acute psychostimulant administration shows larger changes in DA signaling compared to other striatal areas (Pontieri et al., 1995; Aragona et al., 2008). Those changes have also been related to its role in drug and natural reward (Di Chiara et al., 1999). Microdialysis and FSCV provide complementary data on the tonic and phasic effects of drugs on a specific brain region. Previous reports have demonstrated the relationship between microdialysis and FSCV data in the rat model, suggesting that the extracellular level of DA, as measured by microdialysis, is largely established by phasic firing, as measured by FSCV (Owesson-White et al., 2012). The microdialysis and FSCV data presented here suggest that enhancements in basal DA levels detected by microdialysis are likely due not only to the blockade of DAT but also to a small increase in DAMax, leading to more DA being released upon stimulation.

Our results also show that all tested compounds increased behavioral activity counts at levels higher than those produced by vehicle. As already shown for changes in DA levels, R-MOD produced its largest effects on behavior during the 30 minutes after the first, initial dose of 10 mg/kg. The bis(F) analogs, instead, produced a more dose-dependent increase in activity counts, showing their maximum effects at the highest dose tested, 32 mg/kg. These effects suggest a likely interaction between changes in stimulation of DA levels elicited by the different doses of these drugs and their ability to produce behavioral activation.

One of the clinically interesting features of R-MOD is its longer half-life as compared to the (S)-enantiomer (Robertson & Hellriegel, 2003). Our microdialysis results suggest that under our conditions the novel bis(F) analogs of MOD have a longer offset of their effects on the time-course of DA levels (likely the most important target for MOD in the brain), as compared to R-MOD. These features, together with the similar onset of dopaminergic effects for JBG1–048 and R-MOD, informs our drug design for future analogs with similar features. These modifications might allow for a lower daily dosage to reach therapeutic efficacy, thus reducing potential undesirable side effects and increasing compliance, a problem that was evident even in the clinical trials with MOD (Anderson et al., 2012).

CONCLUSIONS

R-MOD increases DA in the NAS, a brain area related to the rewarding and reinforcing effects of abused substances, as well as the motivation to seek them. Interestingly, this change in extracellular DA does not seem to influence its very low (if any) abuse liability in experimental animal models and in humans (Volkow et al., 2009). Our preclinical assessment of the (R)- and (S)-enantiomers of para-bis(F)substituted MOD, under the same conditions, shows a similar profile with some potentially beneficial exceptions. FSCV results indicate that the compounds have nearly identical effects on phasic DA and DA reuptake rates. Of note, tonic DA levels were similar, but longer lasting compared to those produced by cocaine at much lower doses (0.5–1 mg/kg i.v.) (Tanda et al., 1997; Garces-Ramirez et al., 2011), which has been suggested as a hallmark of a class of atypical DAT inhibitors that do not demonstrate reinforcing behaviors in animal models (Tanda et al., 2009; Reith et al., 2015). These tonic levels of DA and related activity counts were increased to higher levels by the bis(F) analogs than by R-MOD, which might translate into similar levels of therapeutic efficacy by administering lower doses of the bis(F) analogs of MOD. Additional evaluation will need to be performed to understand if these increases in DA translate into significant psychostimulant-like behavioral effects in models of drug-taking and relapse. Nevertheless, these data suggest that modifications of the MOD chemical structure, as in these novel bis(F) analogs, could lead to therapeutically useful differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacological activities. These studies will guide future drug design toward the discovery of potential pharmacotherapeutics for the treatment of psychostimulant use disorders.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A special thank you goes to Drs. Mark Wightman and Gina Carelli, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and to all the members of their labs, especially Drs. F. Cacciapaglia, C. Owesson-White, E. Bucher and Z. McElligott, for giving GT the opportunity to visit their labs and receive fundamental training to learn the basics of FSCV first-hand. We would like to thank Dr. Alessandro Bonifazi for helping obtain DAT binding affinities reported herein. We also would like to thank Dr. Jeff Deschamps at the Naval Research Laboratory for his work in obtaining x-ray crystal structures of JBG1–048 and JBG1–049 to assign absolute configurations. Support for this research was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse - Intramural Research Program, NIH/DHHS (Z1A DA000389 21 and Z1A DA000611 2).

Abbreviations.

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- CFME

carbon-fiber microelectrode

- DA

dopamine

- DAT

dopamine transporter

- FSCV

fast-scan cyclic voltammetry

- i.v.

intravenously

- NS

non-significant

- NAS

nucleus accumbens shell

- S.E.M.

standard error of the mean

Footnotes

Authors’ competing interest.

All Authors declare that there are not competing financial interests of any kind in relation to the work described in the present manuscript.

Data Accessibility.

Data supporting the results in the paper will be archived in an appropriate NIH public repository.

REFERENCES

- Adler CH, Caviness JN, Hentz JG, Lind M & Tiede J (2003) Randomized trial of modafinil for treating subjective daytime sleepiness in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord, 18, 287–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AL, Li SH, Biswas K, McSherry F, Holmes T, Iturriaga E, Kahn R, Chiang N, Beresford T, Campbell J, Haning W, Mawhinney J, McCann M, Rawson R, Stock C, Weis D, Yu E & Elkashef AM (2012) Modafinil for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend, 120, 135–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AL, Reid MS, Li SH, Holmes T, Shemanski L, Slee A, Smith EV, Kahn R, Chiang N, Vocci F, Ciraulo D, Dackis C, Roache JD, Salloum IM, Somoza E, Urschel HC 3rd & Elkashef AM (2009) Modafinil for the treatment of cocaine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend, 104, 133–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aragona BJ, Cleaveland NA, Stuber GD, Day JJ, Carelli RM & Wightman RM (2008) Preferential enhancement of dopamine transmission within the nucleus accumbens shell by cocaine is attributable to a direct increase in phasic dopamine release events. J Neurosci, 28, 8821–8831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglund EC, Makos MA, Keighron JD, Phan N, Heien ML & Ewing AG (2013) Oral administration of methylphenidate blocks the effect of cocaine on uptake at the Drosophila dopamine transporter. ACS Chem Neurosci, 4, 566–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucher ES, Brooks K, Verber MD, Keithley RB, Owesson-White C, Carroll S, Takmakov P, McKinney CJ & Wightman RM (2013) Flexible software platform for fast-scan cyclic voltammetry data acquisition and analysis. Anal Chem, 85, 10344–10353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cakic V (2009) Smart drugs for cognitive enhancement: ethical and pragmatic considerations in the era of cosmetic neurology. J Med Ethics, 35, 611–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J, Prisinzano TE, Okunola OM, Kopajtic T, Shook M, Katz JL & Newman AH (2011) Structure-Activity Relationships at the Monoamine Transporters for a Novel Series of Modafinil (2-[(diphenylmethyl)sulfinyl]acetamide) Analogues. ACS Med Chem Lett, 2, 48–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J, Slack RD, Bakare OM, Burzynski C, Rais R, Slusher BS, Kopajtic T, Bonifazi A, Ellenberger MP, Yano H, He Y, Bi GH, Xi ZX, Loland CJ & Newman AH (2016) Novel and High Affinity 2-[(Diphenylmethyl)sulfinyl]acetamide (Modafinil) Analogues as Atypical Dopamine Transporter Inhibitors. J Med Chem, 59, 10676–10691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y & Prusoff WH (1973) Relationship between the inhibition constant (K1) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem Pharmacol, 22, 3099–3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czoty PW, Stoops WW & Rush CR (2016) Evaluation of the “Pipeline” for Development of Medications for Cocaine Use Disorder: A Review of Translational Preclinical, Human Laboratory, and Clinical Trial Research. Pharmacol Rev, 68, 533–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dackis CA, Kampman KM, Lynch KG, Pettinati HM & O’Brien CP (2005) A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of modafinil for cocaine dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology, 30, 205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dackis CA, Kampman KM, Lynch KG, Plebani JG, Pettinati HM, Sparkman T & O’Brien CP (2012) A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of modafinil for cocaine dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat, 43, 303–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deroche-Gamonet V, Darnaudery M, Bruins-Slot L, Piat F, Le Moal M & Piazza PV (2002) Study of the addictive potential of modafinil in naive and cocaine-experienced rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 161, 387–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G, Tanda G, Bassareo V, Pontieri F, Acquas E, Fenu S, Cadoni C & Carboni E (1999) Drug addiction as a disorder of associative learning. Role of nucleus accumbens shell/extended amygdala dopamine. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 877, 461–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G, Tanda G & Carboni E (1996) Estimation of in-vivo neurotransmitter release by brain microdialysis: the issue of validity. Behav Pharmacol, 7, 640–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G, Tanda G, Frau R & Carboni E (1993) On the preferential release of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens by amphetamine: further evidence obtained by vertically implanted concentric dialysis probes. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 112, 398–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration, U. (2007a) FDA Approved Labeling for NUVIGIL® (Armodafinil) Tablets, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration, U. (2007b) FDA Approved Labeling, PROVIGIL® (modafinil) Tablets [Google Scholar]

- Garces-Ramirez L, Green JL, Hiranita T, Kopajtic TA, Mereu M, Thomas A, Mesengeau C, Narayanan S, McCurdy CR, Katz JL & Tanda G (2011) Sigma Receptor Agonists: Receptor Binding And Effects On Mesolimbic Dopamine Neurotransmission Assessed By Microdialysis. Biol Psychiatry, 69, 208–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold LH & Balster RL (1996) Evaluation of the cocaine-like discriminative stimulus effects and reinforcing effects of modafinil. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 126, 286–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart CL, Haney M, Vosburg SK, Rubin E & Foltin RW (2008) Smoked cocaine self-administration is decreased by modafinil. Neuropsychopharmacology, 33, 761–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heal DJ, Buckley NW, Gosden J, Slater N, France CP & Hackett D (2013) A preclinical evaluation of the discriminative and reinforcing properties of lisdexamfetamine in comparison to D-amfetamine, methylphenidate and modafinil. Neuropharmacology, 73, 348–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman ML & Venton BJ (2009) Carbon-fiber microelectrodes for in vivo applications. Analyst, 134, 18–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SR, Garris PA, Kilts CD & Wightman RM (1995) Comparison of dopamine uptake in the basolateral amygdaloid nucleus, caudate-putamen, and nucleus accumbens of the rat. J Neurochem, 64, 2581–2589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SR, O’Dell SJ, Marshall JF & Wightman RM (1996) Functional and anatomical evidence for different dopamine dynamics in the core and shell of the nucleus accumbens in slices of rat brain. Synapse, 23, 224–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW & Duffy P (1995) Selective activation of dopamine transmission in the shell of the nucleus accumbens by stress. Brain Res, 675, 325–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampman KM, Lynch KG, Pettinati HM, Spratt K, Wierzbicki MR, Dackis C & O’Brien CP (2015) A double blind, placebo controlled trial of modafinil for the treatment of cocaine dependence without co-morbid alcohol dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend, 155, 105–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan R & Chary KV (2015) A rare case modafinil dependence. J Pharmacol Pharmacother, 6, 49–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loland CJ, Mereu M, Okunola OM, Cao J, Prisinzano TE, Mazier S, Kopajtic T, Shi L, Katz JL, Tanda G & Newman AH (2012) R-modafinil (armodafinil): a unique dopamine uptake inhibitor and potential medication for psychostimulant abuse. Biol Psychiatry, 72, 405–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall Jones C, Baldwin GT & Compton WM (2017) Recent Increases in Cocaine-Related Overdose Deaths and the Role of Opioids. Am J Public Health, 107, 430–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mereu M, Bonci A, Newman AH & Tanda G (2013) The neurobiology of modafinil as an enhancer of cognitive performance and a potential treatment for substance use disorders. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 229, 415–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mereu M, Chun LE, Prisinzano TE, Newman AH, Katz JL & Tanda G (2017) The unique psychostimulant profile of (+/−)-modafinil: investigation of behavioral and neurochemical effects in mice. Eur J Neurosci, 45, 167–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE & Patrick ME (2018) Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2017: Volume I, Secondary school students In Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, T.U.o.M. (ed). NIDA, Bethesda, MD, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Mignot E, Nishino S, Guilleminault C & Dement WC (1994) Modafinil binds to the dopamine uptake carrier site with low affinity. Sleep, 17, 436–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murillo-Rodriguez E, Haro R, Palomero-Rivero M, Millan-Aldaco D & Drucker-Colin R (2007) Modafinil enhances extracellular levels of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens and increases wakefulness in rats. Behav Brain Res, 176, 353–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okunola-Bakare OM, Cao J, Kopajtic T, Katz JL, Loland CJ, Shi L & Newman AH (2014) Elucidation of structural elements for selectivity across monoamine transporters: novel 2-[(diphenylmethyl)sulfinyl]acetamide (modafinil) analogues. J Med Chem, 57, 1000–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owesson-White CA, Roitman MF, Sombers LA, Belle AM, Keithley RB, Peele JL, Carelli RM & Wightman RM (2012) Sources contributing to the average extracellular concentration of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurochem, 121, 252–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozturk A & Deveci E (2014) Drug Abuse of Modafinil by a Cannabis User. Bulletin of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 24, 405–407. [Google Scholar]

- Partridge BJ, Bell SK, Lucke JC, Yeates S & Hall WD (2011) Smart drugs “as common as coffee”: media hype about neuroenhancement. PLoS One, 6, e28416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G & Watson C (1998) The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates Academic Press, Sydney. [Google Scholar]

- Pontieri FE, Tanda G & Di Chiara G (1995) Intravenous cocaine, morphine, and amphetamine preferentially increase extracellular dopamine in the “shell” as compared with the “core” of the rat nucleus accumbens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 92, 12304–12308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prisinzano TE, Tidgewell K, Podobinski J, Luo M & Swenson D (2004) Synthesis and determination of the absolute configuration of the enantiomers of modafinil. Tetrahedron-Asymmetr, 15, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsson ES, Howard CD, Covey DP & Garris PA (2011) High doses of amphetamine augment, rather than disrupt, exocytotic dopamine release in the dorsal and ventral striatum of the anesthetized rat. J Neurochem, 119, 1162–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall DC, Viswanath A, Bharania P, Elsabagh SM, Hartley DE, Shneerson JM & File SE (2005) Does modafinil enhance cognitive performance in young volunteers who are not sleep-deprived? J Clin Psychopharmacol, 25, 175–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reith ME, Blough BE, Hong WC, Jones KT, Schmitt KC, Baumann MH, Partilla JS, Rothman RB & Katz JL (2015) Behavioral, biological, and chemical perspectives on atypical agents targeting the dopamine transporter. Drug Alcohol Depend, 147, 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson P Jr. & Hellriegel ET (2003) Clinical pharmacokinetic profile of modafinil. Clin Pharmacokinet, 42, 123–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues TM, Castro Caldas A & Ferreira JJ (2016) Pharmacological interventions for daytime sleepiness and sleep disorders in Parkinson’s disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Parkinsonism Relat Disord, 27, 25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabeti J, Adams CE, Burmeister J, Gerhardt GA & Zahniser NR (2002) Kinetic analysis of striatal clearance of exogenous dopamine recorded by chronoamperometry in freely-moving rats. J Neurosci Methods, 121, 41–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahakian BJ, Bruhl AB, Cook J, Killikelly C, Savulich G, Piercy T, Hafizi S, Perez J, Fernandez-Egea E, Suckling J & Jones PB (2015) The impact of neuroscience on society: cognitive enhancement in neuropsychiatric disorders and in healthy people. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 370, 20140214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth P, Scholl L, Rudd RA & Bacon S (2018) Overdose deaths involving opioids, cocaine, and psychostimulants - United States, 2015–2016. Am J Transplant, 18, 1556–1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearer J, Darke S, Rodgers C, Slade T, van Beek I, Lewis J, Brady D, McKetin R, Mattick RP & Wodak A (2009) A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of modafinil (200 mg/day) for methamphetamine dependence. Addiction, 104, 224–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanda G, Ebbs A, Newman AH & Katz JL (2005) Effects of 4’-chloro-3 alpha-(diphenylmethoxy)-tropane on mesostriatal, mesocortical, and mesolimbic dopamine transmission: comparison with effects of cocaine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 313, 613–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanda G, Ebbs AL, Kopajtic TA, Elias LM, Campbell BL, Newman AH & Katz JL (2007) Effects of muscarinic M1 receptor blockade on cocaine-induced elevations of brain dopamine levels and locomotor behavior in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 321, 334–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanda G, Kopajtic TA & Katz JL (2008) Cocaine-like neurochemical effects of antihistaminic medications. J Neurochem, 106, 147–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanda G, Li SM, Mereu M, Thomas AM, Ebbs AL, Chun LE, Tronci V, Green JL, Zou MF, Kopajtic TA, Newman AH & Katz JL (2013) Relations between stimulation of mesolimbic dopamine and place conditioning in rats produced by cocaine or drugs that are tolerant to dopamine transporter conformational change. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 229, 307–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanda G, Newman AH & Katz JL (2009) Discovery of drugs to treat cocaine dependence: behavioral and neurochemical effects of atypical dopamine transport inhibitors. Adv Pharmacol, 57, 253–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanda G, Pontieri FE, Frau R & Di Chiara G (1997) Contribution of blockade of the noradrenaline carrier to the increase of extracellular dopamine in the rat prefrontal cortex by amphetamine and cocaine. Eur J Neurosci, 9, 2077–2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venton BJ, Seipel AT, Phillips PE, Wetsel WC, Gitler D, Greengard P, Augustine GJ & Wightman RM (2006) Cocaine increases dopamine release by mobilization of a synapsin-dependent reserve pool. J Neurosci, 26, 3206–3209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Logan J, Alexoff D, Zhu W, Telang F, Wang GJ, Jayne M, Hooker JM, Wong C, Hubbard B, Carter P, Warner D, King P, Shea C, Xu Y, Muench L & Apelskog-Torres K (2009) Effects of modafinil on dopamine and dopamine transporters in the male human brain: clinical implications. Jama, 301, 1148–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolkowska D, Jain R, Rothman RB, Partilla JS, Roth BL, Setola V, Prisinzano TE & Baumann MH (2009) Evidence for the involvement of dopamine transporters in behavioral stimulant effects of modafinil. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 329, 738–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.