Abstract

Background

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) imposes a high mortality and economic burden. Effective treatment is available, though underutilized.

Objective

Describe trends in AUD pharmacotherapy, variation in prescribing, and associated patient factors.

Design

Retrospective cohort using electronic health records from 2010 to 2019.

Participants

Primary care patients from 39 clinics in Ohio and Florida with diagnostic codes for alcohol dependence or abuse plus social history indicating alcohol use. PCPs in family or internal medicine with at least 20 AUD patients.

Main Measures

Pharmacotherapy for AUD (naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram), abstinence from alcohol, patient demographics, and comorbidities. Generalized linear mixed models were used to identify patient factors associated with prescriptions and the association of pharmacotherapy with abstinence.

Key Results

We identified 13,250 patients; average age was 54 years, 66.9% were male, 75.0% were White, and median household income was $51,776 per year. Over 10 years, the prescription rate rose from 4.4 to 5.6%. Patients who were Black (aOR 0.74; 95% CI 0.58, 0.94) and insured by Medicare versus commercial insurance (aOR 0.61; 95% CI 0.48, 0.78) were less likely to be treated. Higher median household income ($10,000 increment, aOR 1.06; 95% CI 1.03, 1.10) and Medicaid versus commercial insurance (aOR 1.52; 95% CI 1.24, 1.87) were associated with treatment. Receiving pharmacotherapy was associated with subsequent documented abstinence from alcohol (aOR 1.60; 95% CI 1.33, 1.92). We identified 236 PCPs. The average prescription rate was 3.6% (range 0 to 24%). The top decile prescribed to 14.6% of their patients. The bottom 4 deciles had no prescriptions. Family physicians had higher rates of pharmacotherapy than internists (OR 1.50; 95% CI 1.21, 1.85).

Conclusions

Medications for AUD are infrequently prescribed, but there is considerable variation among PCPs. Increasing the use of pharmacotherapy by non-prescribers may increase abstinence from alcohol.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-020-06454-1.

INTRODUCTION

Between 20 and 36% of primary care patients have alcohol use disorder (AUD).1,2 Excessive alcohol use has been linked to an estimated 90,000 annual deaths,3 and the rate of alcohol-related deaths has doubled over the past two decades.4 The economic burden of alcohol use, including healthcare costs, exceeds $250 billion annually in the USA.5

Evidence-based treatment for AUD is effective.6 Treatment can be divided into psychosocial interventions and pharmacotherapy. Psychosocial options include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) which has a modest effect on drinking outcomes.7,8 Others like motivational interviewing and contingency management may have similar efficacy,9 while data is mixed for interpersonal therapy and 12-step facilitation like Alcoholics Anonymous (AA).7,10 A recent Cochrane review found no evidence for benefit of 12-step programs compared with other non-pharmacologic interventions.11 The heterogeneous nature of these interventions makes them difficult to study.9,12

Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved medications recommended by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) for treatment of AUD include naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram. Disulfiram, the first to obtain FDA approval, has demonstrated efficacy in some randomized trials, mostly in supervised settings,13–16 but a 2014 meta-analysis found it was not superior to placebo.15 Acamprosate and oral naltrexone are more effective, reducing return to drinking with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 12 and 20, respectively.15 Naltrexone is also available in a long-acting injectable (LAI) formulation which has also demonstrated efficacy,17 but has not been compared to the oral formulation.

Despite its efficacy, pharmacotherapy is likely underutilized by primary care providers (PCPs). Prior studies reported prescription rates ranging from 2.0 to 16.4% but did not distinguish between PCPs and psychiatrists.18–20 In studies of pharmacy transactions, PCPs were responsible for approximately 25% of prescriptions.21,22 These did not differentiate between PCP-initiated treatment and refills of medication initiated by others. Since then, the opioid epidemic has hastened the acceptance of medication-assisted treatment for the treatment of substance use disorders (SUD).23,24 Treatment of AUD may have been influenced as well.

Our objective was to describe recent trends in pharmacotherapy for AUD in primary care, to identify patient factors associated with pharmacotherapy, and to understand the contribution of individual physicians to the variation in pharmacotherapy.

METHODS

We used electronic health record (EHR) data from the Cleveland Clinic Health System, which is comprised of 39 hospital-based and free-standing clinics in Ohio and Florida. Data were internally validated against a manual chart review to ensure accuracy. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Cleveland Clinic.

Population

We included patients aged ≥ 18 years who had at least 3 primary care visits within a 5-year period with the same internal medicine or family medicine provider between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2019, and an AUD-related diagnosis based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9/10 codes. To increase specificity, we also required alcohol use to be documented in the social history at least once. We excluded patients whose social history was missing or which documented “no alcohol use.” ICD codes had to be documented during or prior to the date of the last PCP visit to ensure PCPs had an opportunity to prescribe pharmacotherapy. We included codes for alcohol dependence and alcohol abuse (303.9, 305.0, F10.10, F10.12-10.20, F10.22-10.28).18–20 AUD is a DSM-5 code without a corresponding ICD code; prior studies utilized alcohol dependence and abuse because fidelity in distinguishing between these categories in clinical practice is low.25

Given the low sensitivity of ICD codes in identifying AUD,26 we considered alternative approaches, including excessive alcohol use in the social history or ICD codes for related diseases (e.g., alcoholic liver disease). These approaches were rejected because neither identified a significant number of new patients; both had low specificity.

To ensure stable estimates of prescribing rates, we included only PCPs who cared for ≥ 20 patients with AUD.

Data

For each patient, we collected demographics (age, sex, race, marital status, and address), insurance type, and comorbidities, including ICD codes for drug abuse—a surrogate for SUD. Patient addresses were correlated with median household income based on census tract and were linked with homelessness status based on known homeless shelter addresses using the Sociome R package.

Physician information included age, sex, length of time in practice, total visits with study patients, clinician title, and board certification. We categorized them as PCPs if they saw patients in Family or Internal Medicine office visits and non-PCPs if they did not. Non-PCPs likely represent addiction medicine specialists or psychiatrists.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was treatment with any pharmacotherapy, including acamprosate, disulfiram, or naltrexone (oral or LAI) based on EHR orders. If pharmacotherapy was prescribed, we noted the date and prescriber. We distinguished between treatment initiation and continuation (refills). As a secondary outcome, we examined abstinence, defined as the presence of an ICD remission code (305.03 or F10.11) confirmed by a social history indicating no alcohol use. We chose this highly specific definition to avoid false positives which would bias any association toward the null. Because the outcome is rare, false negatives have a smaller impact. For patients who were prescribed pharmacotherapy, we noted if abstinence occurred at any point after the prescription. For the remaining patients, we noted if abstinence occurred at any point after the initial AUD diagnosis.

Analysis

We assessed overall prescribing trends by calculating the prescription rate for each of the medications in each calendar year using the number of total prescriptions as the numerator and the number of AUD patients who were established with a PCP as the denominator, even if they did not have a PCP visit that year.

The overall prescription initiation rate among patients was determined and then stratified to prescriptions by PCP versus other. We then created two multivariable models. First, we used a generalized linear mixed model with PCPs as a random effect and patient variables as fixed effects to identify patient factors associated with a prescription by a PCP. Patients with prescriptions from non-PCPs were excluded from this analysis. Because some providers may refer AUD patients to specialists for treatment (e.g., to psychiatrists), we were also interested in factors which correlate with any treatment, including by psychiatrists and addiction medicine specialists who are not PCPs. Therefore, using the entire population, we created a second generalized linear mixed model using the same predictors, again with PCP as a random effect, to identify patient factors associated with any prescription for pharmacotherapy.

We then calculated an adjusted prescribing rate for each PCP, controlling for all patient factors associated with pharmacotherapy. Variability in non-adjusted prescribing rates was demonstrated using a bar graph showing deciles of prescribing rate, and adjusted rates were used to create a caterpillar plot. Because the prescribing rate in the bottom 5 deciles was essentially 0, we compared the top two deciles of prescribers with the bottom five deciles based on adjusted rates using ANOVA, the Kruskal-Wallis test, and Pearson’s chi-square test to identify PCP factors associated with prescribing.

To determine whether receipt of pharmacotherapy was associated with subsequent abstinence, we created a third generalized linear mixed model, again with PCPs as random effects, to measure the association of pharmacotherapy with abstinence, adjusting for all the patient factors included in the previous models. Lastly, to avoid any potential selection bias among patients who received pharmacotherapy, we compared the abstinence rates between patients of physicians in the top two deciles with those of patients in the bottom five deciles based on their adjusted prescribing rates and adjusted for patient characteristics.

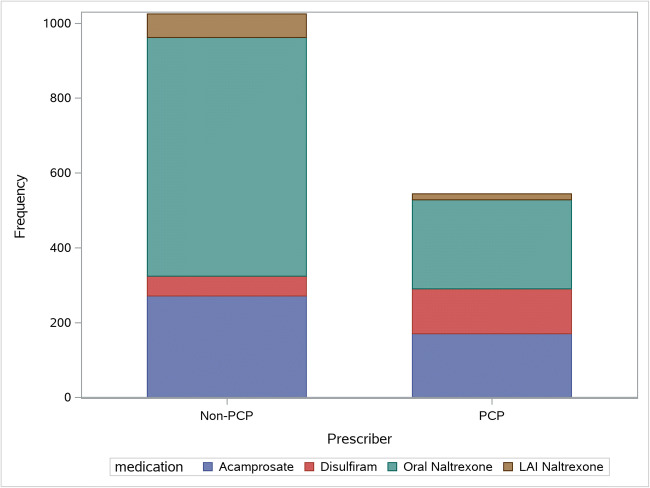

RESULTS

A flowchart of patient inclusion is shown in eFigure 1. Of 13,250 patients who met the inclusion criteria, 1281 (9.7%) received pharmacotherapy for AUD, including 450 (3.4%) prescribed by their PCP. Over the 10-year period, overall prescriptions decreased from 2010 to 2014, then increased again, driven by a rise in naltrexone (eFigure 2). Across the entire period, use of oral and LAI naltrexone increased (from 2.1 to 4.4% and from 0 to 0.5%, respectively), acamprosate decreased (from 2.5 to 1.1%), and disulfiram remained essentially unchanged. Oral naltrexone accounted for 62% of prescriptions by non-PCPs and 44% by PCPs. Disulfiram accounted for 5% of prescriptions by non-PCPs and 22% by PCPs (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Medications prescribed by PCPs versus non-PCPs.

Patients were on average 54 years old, median annual household income was $51,776, and 1.5% were homeless; 66.9% were male; 75.0% were White; 54.3% had a comorbid mood disorder, 57.7% had an anxiety disorder, and 24.4% had SUD (Table 1). Patients who were Black (aOR 0.74; 95% CI 0.58, 0.94) were less likely to be prescribed any pharmacotherapy, while those with higher income (aOR per $10,000: 1.06; 95% CI 1.03, 1.10) and psychiatric comorbidities including mood disorder (aOR 2.95; 95% CI 2.44, 3.57), anxiety disorder (aOR 1.44; 95% CI 1.20, 1.73), and SUD (aOR 1.50; 95% CI 1.28, 1.75) were more likely to receive it (Table 2). Compared to those with commercial insurance, patients with Medicare (aOR 0.61; 95% CI 0.48, 0.78) were less likely and those with Medicaid (aOR 1.52; 95% CI 1.24, 1.87) were more likely to receive pharmacotherapy. The results of the model for prescriptions by PCPs were similar except that patients with SUD were less likely to receive treatment by their PCP.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

| Factor | Total (N = 13,250) | Not treated (N = 11,969) | Treated by a PCP (N = 450) | Treated by non-PCP (N = 831) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 53.9 ± 14.4 | 54.3 ± 14.6 | 50.5 ± 11.7 | 49.8 ± 12.3 | < 0.001a |

| Male, N (%) | 8866 (66.9) | 8130 (67.9) | 270 (60.0) | 466 (56.1) | < 0.001c |

| Race, N (%) | < 0.001c | ||||

| Black | 2749 (20.7) | 2581 (21.6) | 50 (11.1) | 118 (14.2) | |

| White | 9934 (75.0) | 8894 (74.3) | 370 (82.2) | 670 (80.6) | |

| Other | 567 (4.3) | 494 (4.1) | 30 (6.7) | 43 (5.2) | |

| Married, N (%) | 5464 (41.2) | 4975 (41.6) | 202 (44.9) | 287 (34.5) | < 0.001c |

| Household income*, median [Q1, Q3] | 51,776 [36,432, 70,096] | 51,429 [36,058, 69,390] | 59,592 [44,357, 80,787] | 55,020 [39,650, 74,161] | < 0.001b |

| Mood disorder, N (%) | 7190 (54.3) | 6176 (51.6) | 317 (70.4) | 697 (83.9) | < 0.001c |

| Anxiety disorder, N (%) | 7648 (57.7) | 6641 (55.5) | 340 (75.6) | 667 (80.3) | < 0.001c |

| Psychosis, N (%) | 1210 (9.1) | 1091 (9.1) | 27 (6.0) | 92 (11.1) | 0.011c |

| Liver failure, N (%) | 525 (4.0) | 455 (3.8) | 23 (5.1) | 47 (5.7) | 0.013c |

| Substance use disorder, N (%) | 3235 (24.4) | 2756 (23.0) | 114 (25.3) | 365 (43.9) | < 0.001c |

| Homeless, N (%) | 205 (1.5) | 175 (1.5) | 2 (0.44) | 28 (3.4) | < 0.001c |

| Insurance, N (%) | < 0.001c | ||||

| Commercial | 7498 (55.8) | 6624 (55.3) | 289 (64.2) | 485 (58.4) | |

| Medicaid | 1751 (13.2) | 1501 (12.5) | 71 (15.8) | 179 (21.5) | |

| Medicare | 2951 (22.3) | 2766 (23.1) | 58 (12.9) | 127 (15.3) | |

| Other | 1150 (8.7) | 1078 (9.0) | 32 (7.1) | 40 (4.8) |

*Data not available for all subjects (missing values = 46)

aANOVA, bKruskal-Wallis test, cPearson’s chi-square test, and dFisher’s exact test

Table 2.

Generalized Linear Mixed Model Predicting Treatment

| Factor | OR for any prescription (95% CI) | OR for prescription by PCP (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (per 10 years) | 0.97 (0.92, 1.03) | 1.003 (0.91, 1.11) |

| Male | 0.86 (0.74, 1.01) | 0.74 (0.57, 0.95) |

| Race | ||

| White (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Black | 0.74 (0.58, 0.94) | 0.78 (0.51, 1.18) |

| Other | 1.42 (1.04, 1.95) | 1.75 (1.09, 2.80) |

| Married | 0.95 (0.81, 1.11) | 1.18 (0.92, 1.52) |

| Mood disorder | 2.95 (2.44, 3.57) | 2.06 (1.54, 2.74) |

| Anxiety disorder | 1.44 (1.20, 1.73) | 1.36 (1.01, 1.82) |

| Psychosis | 0.86 (0.68, 1.11) | 0.69 (0.44, 1.09) |

| Liver failure | 1.42 (1.03, 1.95) | 1.65 (0.998, 2.71) |

| Substance use disorder | 1.50 (1.28, 1.75) | 0.91 (0.69, 1.20) |

| Insurance | ||

| Commercial (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medicaid | 1.52 (1.24, 1.87) | 1.40 (0.98, 2.00) |

| Medicare | 0.61 (0.48, 0.78) | 0.57 (0.38, 0.84) |

| Other | 0.56 (0.41, 0.77) | 0.84 (0.53, 1.34) |

| Median household income (per $10,000) | 1.06 (1.03, 1.10) | 1.08 (1.03, 1.13) |

| Homeless | 1.26 (0.79, 2.02) | 0.38 (0.09, 1.57) |

| PCP age (per 10 years) | 0.95 (0.86, 1.05) | 0.98 (0.79, 1.23) |

| Female PCP | 0.94 (0.77, 1.15) | 0.85 (0.55, 1.32) |

| PCP degree | ||

| MD (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| DO | 1.02 (0.79, 1.33) | 1.07 (0.61, 1.88) |

| CNP | 0.45 (0.17, 1.19) | N/A |

| PCP specialty | ||

| Family practice (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Internal medicine | 0.83 (0.69, 1.004) | 0.61 (0.41, 0.92) |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; N/A, insufficient data to estimate

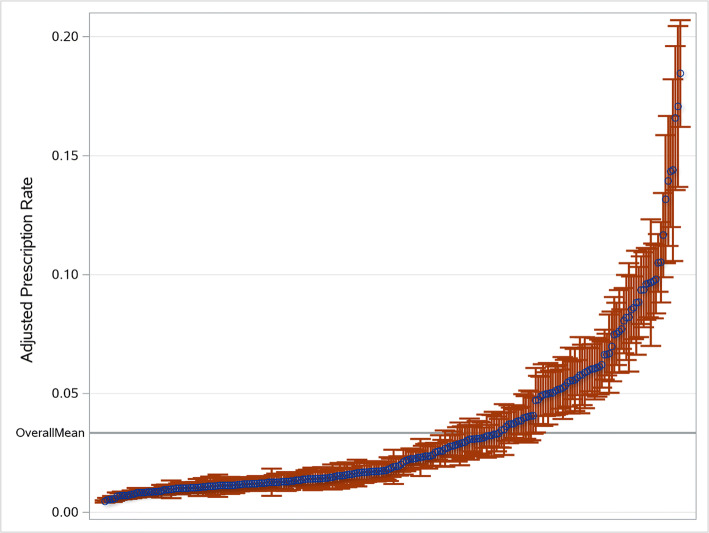

We identified 575 PCPs and removed 339 who did not have at least 20 patients with AUD. The remaining 236 PCPs cared for an average of 44 AUD patients each (range 20 to 142). Average PCP age was 51.5 and 61.9% were male; 39.8% were family physicians, 59.7% were internists, and 2.1% were nurse practitioners (NPs) (Table 3). The mean unadjusted prescription rate was 3.6% with a range of 0 to 24%. There was considerable variation among individual providers. The bottom 45% of PCPs did not prescribe any pharmacotherapy, while the top 10% prescribed to 14.6% of their patients (eFigure 3). Of the 129 prescribing PCPs, 50% prescribed only one medication—half prescribed naltrexone, 23% disulfiram, and 27% acamprosate—while 14% prescribed medications from all three classes. After adjustment for patient factors, 25% of PCPs had prescribing rates significantly above and 60% significantly below the mean (Fig. 2). The only PCP characteristic which correlated with prescribing was specializing in family medicine versus internal medicine (OR 1.50, 95% CI 1.21, 1.85).

Table 3.

PCP Demographics Based on Adjusted Prescription Rate

| Factor | Total (N = 236) | Bottom 5 deciles (N = 118) | Top 2 deciles (N = 47) | Remainder (N = 71) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age*, mean ± SD | 51.5 ± 9.5 | 52.1 ± 9.9 | 51.9 ± 7.7 | 50.4 ± 9.8 | 0.89a |

| Sex | 0.81c | ||||

| Female, no. (%) | 90 (38.1) | 40 (33.9) | 15 (31.9) | 35 (49.3) | |

| Male, no. (%) | 146 (61.9) | 78 (66.1) | 32 (68.1) | 36 (50.7) | |

| Practice years, mean ± SD | 8.1 ± 2.1 | 7.7 ± 2.3 | 8.5 ± 2.1 | 8.4 ± 1.8 | 0.055a |

| Patient visits, mean ± SD | 581.9 ± 356.5 | 592.5 ± 382.3 | 645.1 ± 389.4 | 522.4 ± 276.0 | 0.43a |

| Prescription initiation, mean ± SD | 1.5 ± 2.4 | 0.10 ± 0.30 | 5.1 ± 3.2 | 1.6 ± 0.82 | < 0.001a |

| Patients, mean ± SD | 43.9 ± 22.5 | 45.4 ± 24.5 | 45.9 ± 23.2 | 40.3 ± 18.0 | 0.91a |

| Degree | 0.34d | ||||

| CNP, no. (%) | 5 (2.1) | 5 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| DO, no. (%) | 33 (14.0) | 10 (8.5) | 6 (12.8) | 17 (23.9) | |

| MD, no. (%) | 198 (83.9) | 103 (87.3) | 41 (87.2) | 54 (76.1) | |

| Specialty | < 0.001c | ||||

| Family practice, no. (%) | 94 (39.8) | 34 (28.8) | 27 (57.4) | 33 (46.5) | |

| Internal medicine, no. (%) | 142 (60.2) | 84 (71.2) | 20 (42.6) | 38 (53.5) |

*Data not available for all subjects. Missing values: age = 11

p values: aANOVA, bKruskal-Wallis test, cPearson’s chi-square test, dFisher’s exact test

Figure 2.

Adjusted PCP prescription rates. Blue circles represent the individual adjusted prescription rates of each of the 236 PCPs, and vertical lines represent the associated 95% confidence intervals.

Based on a diagnostic code and documentation in the social history, 1012 patients had documented abstinence. It was more common among patients who received pharmacotherapy than those who did not (14% vs. 7%, p < 0.001) with a NNT of 14. After adjustment for patient variables, prescription of pharmacotherapy was positively associated with abstinence (aOR 1.60; 95% CI 1.33, 1.92) (eTable 1). Moreover, patients of PCPs in the top two deciles of prescribers compared to the bottom five were more likely to have documented abstinence (aOR 1.23; 95% CI 1.01, 1.49). The rate of abstinence documentation for patients not prescribed pharmacotherapy was 7.3% for prescribers in the top two deciles versus 6.4% in the bottom five (p = 0.19).

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective cohort study of 13,250 patients with AUD in a large healthcare system, we found that fewer than 1 in 10 patients received effective pharmacotherapy over a 10-year period, and PCPs were responsible for only about 1/3 of prescriptions. Wealthier, White patients and those with psychiatric comorbidities, including SUD, were most likely to be treated. Insurance coverage was also associated with pharmacotherapy, with patients insured by Medicaid more likely and those with Medicare less likely to receive it. While treatment by PCPs was overall rare, there was substantial variation in prescribing rates, with 45% of physicians never prescribing pharmacotherapy, while the top 10% prescribed it to about 15% of their patients. This is important because patients who received pharmacotherapy were 60% more likely to have documented abstinence.

There is a paucity of studies regarding pharmacotherapy for AUD in primary care. One analysis of pharmacy transactions determined that PCPs account for 25% of naltrexone, 29% of acamprosate, and 42% of disulfiram prescribed in 2006,21 but could not determine how many were refills of prescriptions started by others. By limiting our analysis to prescriptions initiated by the PCP, we better captured the variation in drug starts. We found that PCP starts accounted for 26% of naltrexone, 38% of acamprosate, and 69% of disulfiram. That more than 25% of PCP-initiated prescriptions were for disulfiram, the least effective therapy, suggests that PCPs may need more education regarding effective pharmacotherapy for AUD.

Naltrexone prescriptions more than doubled and represented the largest increase. The rapid increase in LAI naltrexone was notable given the lack of head-to-head trials demonstrating a benefit of LAI over oral naltrexone, which costs less than 1/10 as much.27 It is possible that advertising for the LAI form encouraged prescribing of generic naltrexone.

While prior studies have considered physicians in aggregate, ours appears to be the first to document individual variation.18–20 This is important because individual providers have tremendous influence over whether patients receive pharmacotherapy. The fact that 45% of PCPs did not treat a single patient over 10 years highlights an important quality gap. While our study cannot explain why these physicians did not prescribe pharmacotherapy, qualitative studies have identified a number of barriers, including complexity of treatment, time constraints, lack of knowledge, and physician attitudes towards patients (e.g., viewing patients as unmotivated and dishonest).28,29 The heavy reliance on disulfiram, which punishes patients for drinking rather than relieving them of the urge to drink, may suggest that negative attitudes persist.

Previous research examining patient factors associated with AUD treatment has produced discordant results. Two studies found treatment to be associated with lower income.19,25,30 These studies, which contradict our findings, are hampered by smaller sample sizes,19,30 older data,19,25 or limited populations (e.g., Veterans Administration (VA) health system).25 We found that wealthier, White patients were more likely to receive treatment. This disparity could reflect physician bias—it is well documented that physicians under-prescribe opioid analgesia for Black and Hispanic patients31—or patient preferences regarding medication use could contribute to the disparity, as is the case for statins.32 Further research is needed. Given our population of predominantly Black or White patients with few Hispanics, Asians, and Native Americans, we were unable to report disparities and outcomes for these other racial groups.

Two studies support our findings that comorbid psychiatric illnesses are associated with pharmacotherapy.19,25 This makes sense, because psychiatrists are the primary prescribers of pharmacotherapy. It may also explain why Black patients were less likely to receive it, perhaps reflecting racial disparities in access to mental health.33 Our study appears to be the first to assess the association between insurance coverage and pharmacotherapy. That Medicare coverage was inversely related to pharmacotherapy may also reflect decreased access to mental health services by Medicare recipients due to poor reimbursement.34 In contrast, Medicaid, which has relatively good reimbursement for mental health,35 was positively associated with receipt of pharmacotherapy. Improving access to mental health services, while laudable, cannot be the solution for 14 million Americans with AUD because there are not enough mental health providers to meet this demand.36,37 Instead, PCPs must initiate treatment, but they will need to be properly educated and incentivized to do so.

AUD is highly prevalent in primary care.1,2 Social and economic upheaval has led to the rise of so-called deaths of despair and the recent doubling of alcohol-related deaths.4 Despite the feasibility and efficacy of utilizing AUD pharmacotherapy in primary care,38,39 we found that pharmacotherapy remains the exception rather than the rule. Despite the potential barriers already described, the existence of high-prescribing outliers demonstrates the feasibility of incorporating addiction pharmacotherapy into practice. Further research is needed to determine how such physicians are able to attain high rates of prescribing and how to spread their practices.

One important target may be physician attitudes. Despite scientific advancement in understanding addiction, the model of addiction as a moral failure remains pervasive among PCPs.40,41 Applying medication to a moral problem may feel inappropriate. Instead, religion-based 12-step programs such as AA, which emphasize abstinence and the moral aspects of addiction, have been the traditional mainstay of AUD treatment.19,42 Unfortunately, AA is inferior to medical management in terms of return to heavy drinking and days of abstinence.15,42 Convincing physicians to use pharmacotherapy may require education regarding the science of addiction. Our finding that patients who received pharmacotherapy were more likely to have documented abstinence adds to the evidence in favor of pharmacotherapy in primary care. Despite the effectiveness of pharmacotherapy, no major internal medicine organizations have issued clinical guidelines endorsing its use. However, the immediacy of the opioid epidemic may be changing perceptions regarding medication-assisted therapy for other addictions.

Conclusion

Limitations

The association of pharmacotherapy with documented abstinence could be biased by patient or PCP behaviors. Our findings that patients with prescriptions were more likely to be abstinent (NNT = 14) were similar to those observed in clinical trials for acamprosate and naltrexone (NNT = 12 and 20). While we only characterized abstinence, reduction in drinking is also associated with reduced harm even without complete cessation.43 Because naltrexone can reduce drinking without abstinence,44 increasing its use would likely improve outcomes for patients not committed to abstinence, as the erroneous belief that treatment requires abstinence is a patient-level barrier to seeking treatment.45

There are limitations to estimates of AUD and prescriptions from the EHR. ICD codes have low sensitivity and moderate specificity for alcohol misuse.26 Our requirement of alcohol use in the social history strengthens our results by improving specificity. On the other hand, we likely underestimated the prevalence AUD and consequently over-estimated prescription rates among the entire population with AUD.46 Our results are limited to one health system. Some prescriptions by psychiatrists outside of the health system may not have been captured in our data, but we did identify these prescriptions if medication reconciliation was performed. To the extent that missed prescriptions occurred at random, our conclusions about patient factors associated with treatment remain valid.

Medications for AUD are infrequently prescribed by most PCPs, particularly for lower income patients, African Americans, older patients, Medicare recipients, and uninsured patients. There is considerable variation in PCP prescriptions with many PCPs not prescribing at all and a few high prescribing outliers. Because pharmacotherapy was associated with increased rates of documented abstinence, it is important to identify strategies to increase prescribing of pharmacotherapy in primary care.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 42 kb)

(XLSX 14.7 kb)

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cleary PD, Miller M, Bush T, Warburg MM, L.Delbanco T, Aronson MD. Prevalence and recognition of alcohol abuse in a primary care population. Am J Med. 1988. 10.1016/S0002-9343(88)80079-2 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Buchsbaum DG, Buchanan RG, Centor RM, Schnoll SH, Lawton MJ. Screening for alcohol abuse using CAGE scores and likelihood ratios. Ann Intern Med. 1991. 10.7326/0003-4819-115-10-774 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Prevention. C for DC and. Alcohol and Public Health: Alcohol Related Disease Impact (ARDI).; 2012.

- 4.White AM, Castle IP, Hingson RW, Powell PA. Using Death Certificates to Explore Changes in Alcohol- Related Mortality in the United States, 1999 to 2017. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2020:1–10. 10.1111/acer.14239 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Sacks JJ, Gonzales KR, Bouchery EE, Tomedi LE, Brewer RD. 2010 National and State Costs of Excessive Alcohol Consumption. Am J Prev Med. 2015. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.031 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Reus VI, Fochtmann LJ, Bukstein O, et al. The American psychiatric association practice guideline for the pharmacological treatment of patients with alcohol use disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.1750101 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Ray LA, Meredith LR, Kiluk BD, Walthers J, Carroll KM, Magill M. Combined Pharmacotherapy and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Adults With Alcohol or Substance Use Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, et al. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: The COMBINE study: A randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2006. 10.1001/jama.295.17.2003 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Magill M, Ray LA. Cognitive-behavioral treatment with adult alcohol and illicit drug users: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009. 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Magill M, Kiluk B, Tonigan JS, et al. A meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral therapy for alcohol or other drug use disorders: Treatment efficacy by contrast condition. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2019;87(12):1093–1105. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly JF, Humphreys K, Ferri M. Alcoholics Anonymous and other 12-step programs for alcohol use disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020. 10.1002/14651858.CD012880.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Smedslund G, Berg RC, Hammerstrøm KT, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011. Motivational interviewing for substance abuse. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laaksonen E, Koski-Jännes A, Salaspuro M, Ahtinen H, Alho H. A randomized, multicentre, open-label, comparative trial of disulfiram, naltrexone and acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008. 10.1093/alcalc/agm136 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Azrin NH, Sisson RW, Meyers R, Godley M. Alcoholism treatment by disulfiram and community reinforcement therapy. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1982. 10.1016/0005-7916(82)90050-7 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, et al. Pharmacotherapy for Adults With Alcohol Use Disorders in Outpatient Settings. JAMA. 2014. 10.1001/jama.2014.3628 [PubMed]

- 16.Garbutt JC, West SL, Carey TS, Lohr KN, Crews FT. Pharmacological treatment: Of alcohol dependence - A review of the evidence. J Am Med Assoc. 1999. 10.1001/jama.281.14.1318 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Garbutt JC, Kranzler HR, O’Malley SS, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of long-acting injectable naltrexone for alcohol dependence: A randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2005. 10.1001/jama.293.13.1617 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Thomas CP, Garnick DW, Horgan CM, Miller K, Harris AHS, Rosen MM. Establishing the feasibility of measuring performance in use of addiction pharmacotherapy. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2013. 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Cohen E, Feinn R, Arias A, Kranzler HR. Alcohol treatment utilization: Findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Fernandes-Taylor S, Harris AHS. Comparing alternative specifications of quality measures: Access to pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2012. 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Mark TL, Kassed CA, Vandivort-Warren R, Levit KR, Kranzler HR. Alcohol and opioid dependence medications: Prescription trends, overall and by physician specialty. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Rittenberg A, Hines AL, Alvanzo AAH, Chander G. Correlates of alcohol use disorder pharmacotherapy receipt in medically insured patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths — United States, 2010-2015. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016. 10.15585/mmwr.mm655051e1 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Blanco C, Volkow ND. Management of opioid use disorder in the USA: present status and future directions. Lancet. 2019. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33078-2 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Harris AHS, Oliva E, Bowe T, Humphreys KN, Kivlahan DR, Trafton JA. Pharmacotherapy of Alcohol Use Disorders by the Veterans Health Administration: Patterns of Receipt and Persistence. Psychiatr Serv. 2012. 10.1176/appi.ps.201000553 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Boscarino JA, Moorman AC, Rupp LB, et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2017. Comparison of ICD-9 Codes for Depression and Alcohol Misuse to Survey Instruments Suggests These Codes Should Be Used with Caution. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prescription Prices, Coupons & Pharmacy Information - GoodRx. goodrx.com. Published 2020.

- 28.Hagedorn HJ, Wisdom JP, Gerould H, et al. Implementing alcohol use disorder pharmacotherapy in primary care settings: a qualitative analysis of provider-identified barriers and impact on implementation outcomes. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2019. 10.1186/s13722-019-0151-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Williams EC, Achtmeyer CE, Young JP, et al. Barriers to and Facilitators of Alcohol Use Disorder Pharmacotherapy in Primary Care: A Qualitative Study in Five VA Clinics. J Gen Intern Med. 2018. 10.1007/s11606-017-4202-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Watkins KE, Ober A, McCullough C, et al. Predictors of treatment initiation for alcohol use disorders in primary care. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.06.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Lee P, Le Saux M, Siegel R, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the management of acute pain in US emergency departments: Meta-analysis and systematic review. Am J Emerg Med. 2019. 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Nanna MG, Navar AM, Zakroysky P, et al. Association of patient perceptions of cardiovascular risk and beliefs on statin drugs with racial differences in statin use: Insights from the patient and provider assessment of lipid management registry. JAMA Cardiol. 2018. 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.1511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Mcguire TG, Miranda J. Racial and ethnic disparities in mental health care: evidence and policy implications. Health Aff. 2008. 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Bishop TF, Press MJ, Keyhani S, Pincus HA. Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Zur J, Musumeci M, Garfield R. Medicaid’s Role in Financing Behavioral Health Services for Low-Income Individuals. Henry J Kaiser Fam Found. 2017.

- 36.Analysis NC for HW. State-Level Projections of Supply and Demand for Behavioral Health Occupations: 2016-2030. US Dep Heal Hum Serv Heal Resour Serv Adm Natl Cent Heal Work Anal. 2018.

- 37.Alcoholism NI on AA and. Alcohol Facts and Statistics. calm Clin. 2013. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.10.004

- 38.Oslin DW, Lynch KG, Maisto SA, et al. A Randomized Clinical Trial of Alcohol Care Management Delivered in Department of Veterans Affairs Primary Care Clinics Versus Specialty Addiction Treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 2014. 10.1007/s11606-013-2625-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Lee JD, Grossman E, DiRocco D, et al. Extended-release naltrexone for treatment of alcohol dependence in primary care. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010. 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Leshner AI. Addiction is a brain disease, and it matters. Science (80- ). 1997. 10.1126/science.278.5335.45 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Lawrence RE, Rasinski KA, Yoon JD, Curlin FA. Physicians’ beliefs about the nature of addiction: A survey of primary care physicians and psychiatrists. Am J Addict. 2013. 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.00332.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Roman PMJJ. Treatment Center Study Summary Report: Public Treatment Centers. Athens; 2004. http://ntcs.uga.edu/reports/NTCSsummaryreports/NTCSReportNo.7.pdf.

- 43.Witkiewitz K, Hallgren KA, Kranzler HR, et al. Clinical Validation of Reduced Alcohol Consumption After Treatment for Alcohol Dependence Using the World Health Organization Risk Drinking Levels. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2017. 10.1111/acer.13272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Falk DE, O’Malley SS, Witkiewitz K, et al. Evaluation of Drinking Risk Levels as Outcomes in Alcohol Pharmacotherapy Trials: A Secondary Analysis of 3 Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Wallhed Finn S, Bakshi AS, Andréasson S. Alcohol consumption, dependence, and treatment barriers: Perceptions among nontreatment seekers with alcohol dependence. Subst Use Misuse. 2014. 10.3109/10826084.2014.891616 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Mitchell AJ, Meader N, Bird V, Rizzo M. Clinical recognition and recording of alcohol disorders by clinicians in primary and secondary care: Meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2012. 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.091199 [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 42 kb)

(XLSX 14.7 kb)