Abstract

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is the most common neurodevelopmental disorder in children and shows high heritability. However, how inherited variants contribute to ASD in multiplex families remains unclear. Using whole-genome sequencing (WGS) in a family with three affected children, we identified multiple inherited DNA variants in ASD-associated genes and pathways (RELN, SHANK2, DLG1, SCN10A, KMT2C and ASH1L). All are shared among the three children, except ASH1L, which is only present in the most severely affected child. The compound heterozygous variants in RELN, and the maternally inherited variant in SHANK2, are considered to be major risk factors for ASD in this family. Both genes are involved in neuron activities, including synaptic functions and the GABAergic neurotransmission system, which are highly associated with ASD pathogenesis. DLG1 is also involved in synapse functions, and KMT2C and ASH1L are involved in chromatin organization. Our data suggest that multiple inherited rare variants, each with a subthreshold and/or variable effect, may converge to certain pathways and contribute quantitatively and additively, or alternatively act via a 2nd-hit or multiple-hits to render pathogenicity of ASD in this family. Additionally, this multiple-hits model further supports the quantitative trait hypothesis of a complex genetic, multifactorial etiology for the development of ASDs.

Keywords: Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), whole-genome sequencing (WGS), gene variants, RELN gene, SHANK2 gene, quantitative trait hypothesis, complex genetics

1. Introduction

According to the National Autism Spectrum Disorder Surveillance System (NASS) (2018), Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is diagnosed in 1 in 66 Canadian children and youth (ages 5–17), making it one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders in children. Almost half of the cases have unknown causes. Although both environmental and genetic factors are known to be involved in ASD pathogenesis, the genetic heritability of autism can reach up to 90% in early twin studies [1], indicating a strong genetic influence on ASD. To date, hundreds of genes and DNA copy number variant (CNV) loci have been reported to be associated with ASD susceptibility [2]. However, even the most common single-nucleotide variant (SNV) or genomic CNV micro-deletion or -duplication account for no more than 3% of ASD cases [3], suggesting a highly heterogeneous genetic background. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS), as a state-of-the-art high-throughput technology, has improved ASD diagnosis by 20% and has shown the potential to become a first-tier genetic test for neurodevelopmental disorders [4,5]. Using WGS and genome-wide chromosomal microarray, it has now been demonstrated that de novo mutations can be found in 5–30% of ASDs, especially in simplex families with sporadic cases [6]. However, the genetics of inherited rare variants are poorly understood, despite the fact that they can be found in 3–5% of cases of ASD [3]. Therefore, the cause of ASD in multiplex (MPX) families, in which more than one member is affected, remains largely unknown.

As part of a collaboration established between the iTARGET Autism project (http://www.itargetautism.ca/) and the Autism Speaks MSSNG project (https://www.mss.ng/), we used WGS to detect SNVs, small insertions and deletions (indels), and genomic CNVs in an MPX family with three affected children, aiming to investigate disease-causing/disposing variants which are segregated with the phenotype in this family.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS)

WGS was performed using the following platforms (the Illumina HiSeq X WGS platform for Sib-2 and Sib-3; Complete Genome on Sib-1) at the Toronto Sick Kids Hospital through our collaboration. The data were aligned with the reference genome (GRCh38). Both vcf and bam files were imported into a commercial software VarSeq (GoldenHelix, Inc., Bozeman, MT, USA) for SNVs/Indels and CNVs analysis. In brief, CNVs were generated by the Binned Region Coverage (minimum 10 Kb) and CNV algorithm in VarSeq. The SNVs/Indels were filtered by quality control (QC), annotated by over 20 databases in VarSeq, and interpreted by our internal pipeline. Our major criteria include QC for Read Depth ≥ 10, Genotype Quality ≥ 20); MAF ≤ 0.05 in gnomAD [7] for homozygous recessive and compound heterozygous variants; MAF ≤ 0.01 for de novo, X-linked, ASD candidate genes, imprinting genes, incidental findings (59 genes on the ACMG incidental finding list), loss-of-function (LOF) variants, and others on our in-house gene lists. Our criteria on variants with a disease-causing effect include: (1) Missense (missense, inframe-deletion/insertion, 5_prime_UTR_premature_start_codon) and LOF (stop-gain, stop-loss, frameshift, essential splice, and initiator codon) variants. (2) Frequency in gnomAD meets the criteria for different inheritance patterns, described above. (3) The PHRED score of CADD [8] is >20 on VarSeq software. (4) At least 2 out of 5 bioinformatics tools were predicted as damaging according to the algorithm on VarSeq software (SIFTPred, Polyphen2HumVarPred, MutationTasterPred, MutationAssessorPred, FATHMMPred). (5) Genes listed on SFARI (https://gene.sfari.org/, accessed on 1 October 2020). (6) Other evidence from OMIM (https://omim.org, accessed on 1 October 2020), HGMD (Professional 2021.1), ClinGen (https://clinicalgenome.org/, accessed on 1 October 2020), Genereviews (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1116/, accessed on 1 October 2020), ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/, accessed on 1 October 2020), PubMed, GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/, accessed on 1 October 2020), AutDB (http://autism.mindspec.org/autdb/Welcome.do, accessed on 1 October 2020), Genatlas (http://genatlas.medecine.univ-paris5.fr/, accessed on 01 October 2020), Locus Reference Genomic (LRG) (https://www.lrg-sequence.org/, accessed on 1 October 2020), Decipher (https://www.deciphergenomics.org/, accessed on 1 October 2020), etc. (7) Correlation analysis with phenotypes collected from patient’s charts.

2.2. Subjects

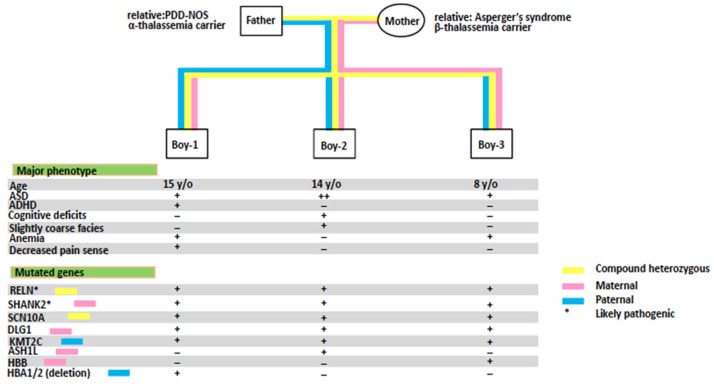

The participating family for this study has three boys with ASD, born to phenotypically normal, non-consanguineous parents. The mother is a β-thalassemia carrier. The mother’s paternal aunt and uncle both exhibit symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and anxiety disorder (unconfirmed). The mother’s father is anemic and is strongly suspected to have high-functioning ASD. The father is an α-thalassemia carrier, and the father’s nephew has Pervasive Developmental Disorder—Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS). All of the boys were diagnosed with ASD using gold-standard Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule—Generic (ADOS-G) and Autism Diagnostic Interview—Revised (ADI-R) psychometric measures. Sib-1 (15 years old) has Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), anemia, decreased pain sensitivity, and no outwardly syndromic features. Sib-2 (14 years old) has slightly coarse facies. He shows the most prominent cognitive deficits and a greater severity of ASD. He has a history of dysphagia and no anemia (not a thalassemia carrier). Sib-3 (8 years old) has suspected IUGR, anemia since birth, astigmatism, and dysphagia with problematic swallowing. None of the affected siblings show any outwardly syndromic or dysmorphic features.

3. Results

3.1. Single Nucleotide Variant (SNV) Findings

No rare de novo variants with significant disease-causing effects were found in this family. Instead, we identified multiple rare inherited variants in ASD candidate genes, mostly shared by all three siblings, which we assert collectively contribute to the pathogenesis of ASD in these three siblings (Figure 1 and Table 1).

Figure 1.

Clinical features and genomic findings distributed in the multiplex family.

Table 1.

ASD-related genes and variants identified in the multiplex family.

| Gene | Variant | Inheritance | Frequency | CADD PHRED Score | Gene Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RELN | NM_005045.3:c.3457G>A;NP_005036.2:p.Val1153Ile;/NM_005045.3:c.1888A>C;NP_005036.2:p.Ser630Arg | Compound heterozygous (in all 3 boys) | <0.0004/<0.026 | 19/25 | Synaptic function and neuronal migration |

| SHANK | NM_133266.4:c.3550C>T;NP_573573.2:p.Pro1184Ser | Mat (in all 3 boys) | ≤8.236 × 10−6 | 24 | Synapse formation, maturation and structural plasticity |

| KMT2C | NM_170606.2:c.12898T>C;NP_733751.2:p.Ser4300Pro | Pat (in all 3 boys) | <0.0004 | 24 | Leukemogenesis and chromatin organization |

| DLG1 | NM_004087.2:c.884C>T; NP_004078.2:p.Ala295Val | Mat (in all 3 boys) | <0.0016 | 33 | Synapse formation and function |

| SCN10A | NM_006514.3:c.3425G>C;NP_006505.3:p.Arg1142Pro/NM_006514.3:c.3542C>T;NP_006505.3:p.Thr1181Met | Compound heterozygous (in all 3 boys) | NR/<0.0022 | 34/14 | Sodium channel, modulating the activity of CNS neurons |

| ASH1L | NM_018489.2:c.1298A>C;NP_060959.2:p.Gln433Pro | Mat (only in Boy-2) | ≤0.00003 | 20 | Chromatin remodeling and organization |

Note: Mat: maternal. Pat: paternal.

First, all three affected children were found to share rare compound heterozygous variants in RELN (NP_005036.2: p.Ser630Arg and p.Val1153Ile). These variants are located in exons 15 and 25 within repeat 1 and 2 of the Reelin protein domain, respectively. Both variant loci are highly conserved in many species. The missense p.Ser630Arg variant was inherited from the mother, present in dbSNP with <3% in normal population databases, including gnomAD, 1000 Genome, and NHLBI ESP6500. Multiple bioinformatics tools predict this variant as damaging (SIFT, MutationTaster, Polyphen2 HDIV, LRT, FATHMM MKL) with the PHRED score of CADD as 25. The missense p.Val115Ile variant was paternally inherited, absent from dbSNP or ClinVar, with <0.05% in normal population databases and a PHRED score of CADD as 19. Meanwhile, we also detected a paternally inherited missense coding single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) mutation of RELN (rs36269) in dbSNP in exon 22 (NP_005036.2: p.Leu997Val). All three siblings share this SNP. Contradictory results from the literature suggest that this variant either significantly contributes to the susceptibility of ASD [9,10,11], or does not [12,13,14].

The second possibly disease-associated, rare variant found to be shared by all three affected boys was a maternal missense variant in SHANK2 (NP_573573.2:p.Pro1184Ser). This missense variant is absent from dbSNP, ClinVar, 1000 Genome, and NHLBI ESP6500 with <0.001% in gnomAD. The variant in our proband occurred at a location 10 amino acids away from the conserved SAM domain of Shank family proteins. It was predicted to be damaging by multiple bioinformatics tools (SIFT, MutationTaster, Polyphen2 HDIV, PROVEAN, FATHMM MKL) with the PHRED score of CADD as 24.

In addition to SNVs in RELN and SHANK2, several other inherited variants were also found in the three affected siblings, which involve ASD candidate genes and pathways. These include a paternal variant in KMT2C (NP_733751.2:P.Ser4300Pro), a maternal variant in DLG1 (NP_004078.2:P.Ala295Val), and compound heterozygous variants in SCN10A (NP_006505.3:P.Arg1142Pro and P.Thr1181Met). A maternal variant in ASH1L (NP_060959.2:p.Gln433Pro) was identified only in Sib-2. They are all rare missense variants with high CADD scores (20–34).

3.2. Copy Number Variants (CNVs) Findings

Using genome-wide chromosomal microarray (Affymetrix CytoScan HD platform; Affymetrix Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA), we did not find any abnormal CNVs in Sib-2 or Sib-3. However, we identified an 18 kb deletion in Sib-1: arr[hg38]16p13.3(166421-184365)x1, involving HBA1, HBA2, HBQ1, and HBM (α hemoglobin locus). CNV analysis from WGS confirmed that this deletion was inherited from the father, who is an α-thalassemia carrier. Consistent with the family history of thalassemia (mother is a β-thalassemia carrier), a maternal pathogenic LOF mutation in HBB (c.126_129delCTTT, p.Phe42Leufs) was identified in Sib-3. Both Sib-1 and Sib-3 have anemia, while Sib-2, without anemia, does not have either of these two mutations.

4. Discussion

Using WGS, we identified multiple rare inherited variants in a multiplex family with three affected children. The major ASD risk factors include compound heterozygous variants in RELN and a maternal missense variant in SHANK2, which are shared in all three children. RELN encodes Reelin, a large glycoprotein secreted by GABAergic interneurons and glutamatergic cerebellar neurons. It plays a vital role in Purkinje cell positioning during brain development and in modulating adult synapse transmission and plasticity [15,16]. A deficiency in Reelin signaling and pathologic impairment of Reelin secretion was found to contribute to ASD risk [17]. Reeler mice, which lack the Reln gene, show impaired GABAergic Purkinje neuron expression/positioning during cerebellar development [18], and exhibit abnormal social and repetitive behaviors similar to ASD behaviors [19]. RELN is a high-confidence ASD-associated gene with many rare de novo and inherited missense variants identified in patients with ASD [20]. However, most of these variants lack functional analysis, and some of them are inherited from unaffected parents, suggesting that the RELN mutation shows variable expression or incomplete penetrance; hence, it is unable to cause ASD by itself [2,20,21,22]. Instead, RELN variants may act as risk factors to co-act and synergize with other genetic or environmental factors, collectively contributing to an ASD phenotype. Recently, Sanchez-Sanchez et al. identified rare compound heterozygous missense variants in RELN in a patient with ASD [23]. Using iPSC-derived neural progenitor cells (NPCs) from their patient, they provided experimental evidence that the identified variants are deleterious, and lead to diminished Reelin secretion and impaired Reelin–DAB1 and mTORC1 signal pathways. Moreover, they found a de novo splice-site variant in the CACNA1H gene and an inherited missense variant in the CYFIP1 gene, both of which are connected with mTORC1 and Reelin–DAB1 signaling cascades. The findings of Sanchez-Sanchez et al. support our hypothesis and results for a multiple-hits or quantitative risk variant model of ASD etiology, and confirm that heterozygous or compound heterozygous recessive variants in the RELN gene are cannot cause ASD by themselves.

SHANK2 is a post-synaptic scaffolding gene located at the post-synaptic density of glutamatergic synapses. It plays a crucial role in the excitatory synaptic transmission [24,25], and the formation of dendritic spines [26,27]. Shank2 knockout mouse models show defects in excitatory synapse function and display an ASD-like phenotype, including abnormalities in motor behavior, vocalization, and socialization [25,28]. In humans, inherited variants in SHANK2 were found to be shared by multiple affected siblings and their slightly affected or unaffected parents [26,29,30], suggesting that additional genetic/epigenetic factors, together with inherited SHANK2 mutations, might be necessary to develop ASD [30,31].

Interestingly, both RELN and SHANK2 are associated with neuron activities, including synaptic function and GABAergic interneuron signaling pathways. An imbalance in these pathways has been hypothesized as an underlying mechanism of ASD (for review, see [32]). RELN-involved Reelin-signaling pathway interacts with neuroligins indirectly through a scaffolding protein, PSD-95, which is anchored to the cytoskeletons through SHANK proteins [21,33]. However, the co-existence of variants in both RELN and SHANK2 genes found in subjects with ASD has not previously been reported.

Additionally, we identified several other rare inherited variants in ASD associated genes and pathways among the affected children, including DLG1, SCN10A, KMT2C, and ASH1L. DLG1 gene encodes a scaffolding protein that plays a vital role in normal development, including synaptogenesis [34]. It is hypothesized that alterations in scaffolding protein dynamics could be part of the pathophysiology of ASD [35]. SCN10A gene is a part of the sodium channel family and is involved in modulating the activity of neurons [36]. A limited number of rare missense variants in DLG1 and SCN10A have been reported in cases with ASDs [35,37]. Whether or not they are novel ASD candidate genes needs further functional analysis. Both KMT2C and ASH1L are histone methyltransferases genes with shared domains (an AT hook DNA-binding domain and a PHD-finger motif) and functions. They are important histone regulator genes and involved in chromatin organization [38,39]. Disruption of histone methylation has been reported in neurodevelopmental disorders and ASDs [20]. Variants in these two strong ASD candidate genes are also widely reported in ASD cases [2,20,40].

All of the above detected familial variants were found to be shared by all three children, except for the variant in ASH1L that was only detected in Sib-2. Sib-2 is the most severely affected among the three children. It has been demonstrated that patients with two or more de novo mutations in ASD candidate genes showed more severe phenotypes [41,42]. Whether this inherited ASH1L missense variant may contribute to the more severe ASD phenotype in Sib-2 needs further functional studies.

Noticeably, RELN, SHANK2, and DLG1 are all involved in synapse functions, while KMT2C and ASH1L share chromatin organization in function. The regulation and maintenance of synapse activity and chromatin organization are closely associated with ASD pathogenesis [2,20,43]. Our data suggest that the convergence of the variants of these genes in certain ASD relevant pathways might contribute to the risk of ASD. Individually, each of the variants that we identified in this family, was found not to play a significant role in causing ASD. However, their co-occurrence and co-segregation amongst the three affected children, especially their interconnected gene functions and mechanistic pathways, might indicate their involvement in the ASD pathogenesis in this family. For example, they may co-act and synergize together to increase the genetic mutation load resulting in the disruption of one or multiple gene signal pathways. In addition, these data further support that there is advantage to using WGS in genotype-phenotype and pathway-based analysis of genomic data, which is essential to genetic counseling and management decisions based on ASD genomic etiology, rather than symptoms alone.

One of the limitations of our study is the lack of functional testing of these variants. The pathogenicity of these identified variants isbased solely on in silico prediction tools, although they are widely used in the current sequencing analysis. Additionally, more evidence is required for future family-based WGS analysis in more ASD multiplex families.

5. Conclusions

We identified multiple inherited missense variants of the six ASD-related genes and pathways shared in this MPX family. Our data suggest that each of the variants may have a variable subthreshold or subtle clinical impact. However, together they may collectively and quantitatively contribute to an additive “tipping over the ASD threshold” effect, supporting a multiple-gene hit model for the complex genetic basis and development of ASD.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our sincere thanks to the study participants/families involved in this study. iTARGET is supported by Genome British Columbia (Strategic Initiative B22ITG).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Q.; Data curation, Y.Q., A.G., S.J. and S.L.; Formal analysis, Y.Q.; Funding acquisition, K.C. and S.L.; Methodology, Y.Q.; Project administration, K.C., E.R.-S. and S.L.; Resources, S.R., C.C., A.G. and S.W.S.; Supervision, S.W.S. and S.L.; Validation, S.M.; Visualization, S.W.S.; Writing—original draft, J.D.; Writing—review and editing, J.D., Y.Q., K.C. and S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Genome BC (PI: MESL; Grant # B22ITG) and the Canadian Foundation for Innovation (CFI-LEF 19924). MESL is a senior clinician scientist supported by the B.C. Children’s Hospital Research Institute Investigator Grant Award Program (iGAP).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the University of British Columbia and Children’s & Women’s Health Centre of British Columbia (H01-70507; 2001 to present).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the manuscript, or can be obtained from the authors upon written request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sandin S., Lichtenstein P., Kuja-Halkola R., Hultman C., Larsson H., Reichenberg A. The Heritability of Autism Spectrum Disorder. JAMA. 2017;318:1182–1184. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.12141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yuen R.K.C., Merico D., Bookman M., Howe J.L., Thiruvahindrapuram B., Patel R.V., Whitney J., Deflaux N., Bingham J., Wang Z., et al. Whole genome sequencing resource identifies 18 new candidate genes for autism spectrum disorder. Nat. Neurosci. 2017;20:602–611. doi: 10.1038/nn.4524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramaswami G., Geschwind D.H. Genetics of autism spectrum disorder. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2018;147:321–329. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63233-3.00021-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernandez B.A., Scherer S.W. Syndromic autism spectrum disorders: Moving from a clinically defined to a molecularly defined approach. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2017;19:353–371. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2017.19.4/sscherer. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trost B., Walker S., Haider S.A., Sung W.W.L., Pereira S., Phillips C.L., Higginbotham E.J., Strug L.J., Nguyen C., Raajkumar A., et al. Impact of DNA source on genetic variant detection from human whole-genome sequencing data. J. Med. Genet. 2019;56:809–817. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2019-106281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sebat J., Muotri A.R., Iakoucheva L.M. Getting to the cores of autism. Cell. 2019;178:1287–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karczewski K.J., Francioli L.C., Tiao G., Cummings B.B., Alföldi J., Wang Q., Collins R.L., Laricchia K.M., Ganna A., Birnbaum D.P., et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature. 2020;581:434–443. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2308-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rentzsch P., Schubach M., Shendure J., Kircher M. CADD-Splice—Improving genome-wide variant effect prediction using deep learning-derived splice scores. Genome Med. 2021 doi: 10.1186/s13073-021-00835-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li H., Li Y., Shao J., Li R., Qin Y., Xie C., Zhao Z. The association analysis of RELN and GRM8 genes with autistic spectrum disorder in Chinese Han population. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2008;147B:194–200. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Serajee F.J., Zhong H., Huq A.H.M. Association of Reelin gene polymorphisms with autism. Genomics. 2006;87:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Z., Hong Y., Zou L., Zhong R., Zhu B., Shen N., Chen W., Lou J., Ke J., Zhang T., et al. Reelin gene variants and risk of autism spectrum disorders: An integrated meta-analysis. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2014;165B:192–200. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonora E., Beyer K.S., Lamb J.A., Parr J.R., Klauck S.M., Benner A., Paolucci M., Abbott A., Ragoussis I., Poustka A., et al. International Molecular Genetic Study of A. Analysis of reelin as a candidate gene for autism. Mol. Psychiatry. 2003;8:885–892. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dutta S., Sinha S., Ghosh S., Chatterjee A., Ahmed S., Usha R. Genetic analysis of reelin gene (RELN) SNPs: No association with autism spectrum disorder in the Indian population. Neurosci. Lett. 2008;441:56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma J.R., Arieff Z., Gameeldien H., Davids M., Kaur M., van der Merwe L. Association analysis of two single-nucleotide polymorphisms of the RELN gene with autism in the South African population. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomark. 2013;17:93–98. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2012.0212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bottner M., Ghorbani P., Harde J., Barrenschee M., Hellwig I., Vogel I., Ebsen M., Forster E., Wedel T. Expression and regulation of reelin and its receptors in the enteric nervous system. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2014;61:23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maloku E., Covelo I.R., Hanbauer I., Guidotti A., Kadriu B., Hu Q., Davis J.M., Costa E. Lower number of cerebellar Purkinje neurons in psychosis is associated with reduced reelin expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:4407–4411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914483107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weeber E.J., Beffert U., Jones C., Christian J.M., Forster E., Sweatt J.D., Herz J. Reelin and ApoE receptors cooperate to enhance hippocampal synaptic plasticity and learning. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:39944–39952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205147200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goffinet A.M. Events governing organization of postmigratory neurons: Studies on brain development in normal and reeler mice. Brain Res. 1984;319:261–296. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(84)90013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salinger W.L., Ladrow P., Wheeler C. Behavioral phenotype of the reeler mutant mouse: Effects of RELN gene dosage and social isolation. Behav. Neurosci. 2003;117:1257–1275. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.6.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Rubeis S., He X., Goldberg A.P., Poultney C.S., Samocha K., Cicek A.E., Kou Y., Liu L., Fromer M., Walker S., et al. Synaptic, transcriptional and chromatin genes disrupted in autism. Nature. 2014;515:209–215. doi: 10.1038/nature13772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lammert D.B., Howell B.W. RELN Mutations in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2016;10:84. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2016.00084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neale B.M., Kou Y., Liu L., Ma’ayan A., Samocha K.E., Sabo A., Lin C.F., Stevens C., Wang L.S., Makarov V., et al. Patterns and rates of exonic de novo mutations in autism spectrum disorders. Nature. 2012;485:242–245. doi: 10.1038/nature11011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanchez-Sanchez S.M., Magdalon J., Griesi-Oliveira K., Yamamoto G.L., Santacruz-Perez C., Fogo M., Passos-Bueno M.R., Sertie A.L. Rare RELN variants affect Reelin-DAB1 signal transduction in autism spectrum disorder. Hum. Mutat. 2018;39:1372–1383. doi: 10.1002/humu.23584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sala C., Piech V., Wilson N.R., Passafaro M., Liu G., Sheng M. Regulation of dendritic spine morphology and synaptic function by Shank and Homer. Neuron. 2001;31:115–130. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00339-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmeisser M.J., Ey E., Wegener S., Bockmann J., Stempel A.V., Kuebler A., Janssen A.L., Udvardi P.T., Shiban E., Spilker C., et al. Autistic-like behaviours and hyperactivity in mice lacking ProSAP1/Shank2. Nature. 2012;486:256–260. doi: 10.1038/nature11015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berkel S., Tang W., Trevino M., Vogt M., Obenhaus H.A., Gass P., Scherer S.W., Sprengel R., Schratt G., Rappold G.A. Inherited and de novo SHANK2 variants associated with autism spectrum disorder impair neuronal morphogenesis and physiology. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011;21:344–357. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grabrucker A.M., Knight M.J., Proepper C., Bockmann J., Joubert M., Rowan M., Nienhaus G.U., Garner C.C., Bowie J.U., Kreutz M.R., et al. Concerted action of zinc and ProSAP/Shank in synaptogenesis and synapse maturation. EMBO J. 2011;30:569–581. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Won H., Lee H.R., Gee H.Y., Mah W., Kim J.I., Lee J., Ha S., Chung C., Jung E.S., Cho Y.S., et al. Autistic-like social behaviour in Shank2-mutant mice improved by restoring NMDA receptor function. Nature. 2012;486:261–265. doi: 10.1038/nature11208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Homann O.R., Misura K., Lamas E., Sandrock R.W., Nelson P., McDonough S.I., DeLisi L.E. Whole-genome sequencing in multiplex families with psychoses reveals mutations in the SHANK2 and SMARCA1 genes segregating with illness. Mol. Psychiatry. 2016;21:1690–1695. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leblond C.S., Heinrich J., Delorme R., Proepper C., Betancur C., Huguet G., Konyukh M., Chaste P., Ey E., Rastam M., et al. Genetic and functional analyses of SHANK2 mutations suggest a multiple hit model of autism spectrum disorders. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chilian B., Abdollahpour H., Bierhals T., Haltrich I., Fekete G., Nagel I., Rosenberger G., Kutsche K. Dysfunction of SHANK2 and CHRNA7 in a patient with intellectual disability and language impairment supports genetic epistasis of the two loci. Clin. Genet. 2013;84:560–565. doi: 10.1111/cge.12105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maloney S.E., Rieger M.A., Dougherty J.D. Identifying essential cell types and circuits in autism spectrum disorders. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2013;113:61–96. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-418700-9.00003-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ebert D.H., Greenberg M.E. Activity-dependent neuronal signalling and autism spectrum disorder. Nature. 2013;493:327–337. doi: 10.1038/nature11860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murata Y., Constantine-Paton M. Postsynaptic density scaffold SAP102 regulates cortical synapse development through EphB and PAK signaling pathway. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:5040–5052. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2896-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soler J., Fananas L., Parellada M., Krebs M.O., Rouleau G.A., Fatjo-Vilas M. Genetic variability in scaffolding proteins and risk for schizophrenia and autism-spectrum disorders: A systematic review. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2018;43:223–244. doi: 10.1503/jpn.170066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blasius A.L., Dubin A.E., Petrus M.J., Lim B.K., Narezkina A., Criado J.R., Wills D.N., Xia Y., Moresco E.M., Ehlers C., et al. Hypermorphic mutation of the voltage-gated sodium channel encoding gene Scn10a causes a dramatic stimulus-dependent neurobehavioral phenotype. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:19413–19418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117020108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xing J., Kimura H., Wang C., Ishizuka K., Kushima I., Arioka Y., Yoshimi A., Nakamura Y., Shiino T., Oya-Ito T., et al. Resequencing and Association Analysis of Six PSD-95-Related Genes as Possible Susceptibility Genes for Schizophrenia and Autism Spectrum Disorders. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:27491. doi: 10.1038/srep27491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koemans T.S., Kleefstra T., Chubak M.C., Stone M.H., Reijnders M.R.F., de Munnik S., Willemsen M.H., Fenckova M., Stumpel C., Bok L.A., et al. Functional convergence of histone methyltransferases EHMT1 and KMT2C involved in intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorder. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1006864. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taniguchi H., Moore A.W. Chromatin regulators in neurodevelopment and disease: Analysis of fly neural circuits provides insights: Networks of chromatin regulators and transcription factors underlie Drosophila neurogenesis and cognitive defects in intellectual disability and neuropsychiatric disorder models. Bioessays. 2014;36:872–883. doi: 10.1002/bies.201400087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stessman H.A., Xiong B., Coe B.P., Wang T., Hoekzema K., Fenckova M., Kvarnung M., Gerdts J., Trinh S., Cosemans N., et al. Targeted sequencing identifies 91 neurodevelopmental-disorder risk genes with autism and developmental-disability biases. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:515–526. doi: 10.1038/ng.3792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo H., Wang T., Wu H., Long M., Coe B.P., Li H., Xun G., Ou J., Chen B., Duan G., et al. Inherited and multiple de novo mutations in autism/developmental delay risk genes suggest a multifactorial model. Mol. Autism. 2018;9:64. doi: 10.1186/s13229-018-0247-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yuen R.K., Thiruvahindrapuram B., Merico D., Walker S., Tammimies K., Hoang N., Chrysler C., Nalpathamkalam T., Pellecchia G., Liu Y., et al. Whole-genome sequencing of quartet families with autism spectrum disorder. Nat. Med. 2015;21:185–191. doi: 10.1038/nm.3792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Faundes V., Newman W.G., Bernardini L., Canham N., Clayton-Smith J., Dallapiccola B., Davies S.J., Demos M.K., Goldman A., Gill H., et al. Histone Lysine Methylases and Demethylases in the Landscape of Human Developmental Disorders. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018;102:175–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the manuscript, or can be obtained from the authors upon written request to the corresponding author.