Abstract

Toxoplasmosis is a disease, which was discovered in 1908, caused by the intracellular parasite Toxoplasma gondii. T. gondii infects neuronal, glial, and muscle cells, and chronic infections are characterized by the presence of cysts, in the brain and muscle cells, formed by bradyzoites. T. gondii is capable of synthesizing L-DOPA, a precursor of dopamine. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that is key in the etiology of neuropsychological disorders such as schizophrenia. Previous studies have shown high levels of IgG Toxoplasma antibodies in schizophrenia patients. Many published studies show that the prevalence of toxoplasmosis is higher in schizophrenia patients. In this study, we aimed to identify the prevalence of Toxoplasma infection in patients with schizophrenia and the relationships between, sociodemographic factors and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. A total of 27 schizophrenic patients were included and IgG anti-T. gondii was determined in serum samples by ELISA. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, sociodemographic factors were associated with seropositivity. We found that the prevalence of Toxoplasma antibodies was 51.7%. In the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, statistical significant association (p = 0.024) was found in Item 13 which is related to motor retardation, however, the association turned non-significant after of correction for multiple tests or after of analyzed with a logistic regression p = 0.059, odds ratio (OR) = 2.316 with a 95% confidence interval [0.970 to 5.532]. Other association was not found between toxoplasmosis and others factors. The prevalence of toxoplasmosis on our population under study was significantly higher than that reported by general population or other group of Mexican schizophrenia patients.

Keywords: Toxoplasma gondii, Toxoplasma infection, schizophrenic patients, prevalence, anti-Toxoplasma antibodies

1. Introduction

Toxoplasmosis is a disease, which was discovered in 1908, caused by an intracellular protozoan called Toxoplasma gondii. The infection can be acquired by various mechanisms such as vertical transmission from mother to child and orally through cysts present in raw or undercooked meat [1] and oocysts present in water or fruit and vegetables watered with sewage water and eaten without hand washing. Other infecting mechanisms are infected organ transplants, blood transfusions, and direct contamination, when working in laboratories with hand wounds or when contaminated raw meat is handled [2]. Recently, a new route of infection has been suggested that toxoplasmosis could also be transmitted sexually and by oral sex [3].

The genome of T. gondii contains two genes encoding tyrosine hydroxylase that produces levodopa (L-DOPA), which is a precursor to dopamine. The encoded enzymes metabolize phenylalanine as well as tyrosine with a preference for the tyrosine substrate. One of the genes of Toxoplasma, TgAaaH1, is constitutively expressed, while the other gene, TgAaaH2, is induced by the bradyzoite formation during the life cycle of cyst formation, inducing high levels of dopamine in brain infected with Toxoplasma which can produce some schizophrenic symptoms [4].

Other studies have detected that T. gondii produced L-DOPA in brain of infected rodents [5]. This has led to the hypothesis that an increase in dopamine during infection is associated with observed behavioral changes [5,6,7,8]. Treatment with a dopamine inhibitor (GBR 12909), has been shown to alter the behavior of T. gondii-infected mice [9].

Schizophrenia is a multifactorial disease, which can cause a disabling neuropsychological condition; there is a high incidence of schizophrenia in the general population. Many studies published over the last 20 years show strong association between latent toxoplasmosis and Schizophrenia [10,11]. The first study conducted in schizophrenia patients with primary episodes found that anti-Toxoplasma antibodies were significantly higher as compared with that in a control group [12].

With respect to epidemiology, a prospective follow-up study by Butajira, in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, of 80 patients with schizophrenia, showed that 87.9% of the patients were positive for anti-T. gondii antibodies class IgG [13]. In France, a study of patients with schizophrenia found that 184 (73.6%) of the patients had latent Toxoplasma infection associated with an increased risk in specific symptoms, for example, delusion OR = 3.6 (1.2–10.6) (p = 0.01) [14]. In Iran, 99 patients with schizophrenia and 41 patients with a suicide attempt were studied and IgG anti-Toxoplasma antibodies were positive in 42% of the patients with schizophrenia and 27% of the patients with a suicide attempt, with a significant difference of p = 0.04. [15]. In a Russian study of 155 patients with schizophrenia and 152 healthy people in a control group, IgM and IgG anti-Toxoplasma were determined. In both groups, IgM was negative but IgG anti-Toxoplasma antibodies were positive in 40% of patients and 25% of the control group. The absence of IgM immunoglobulin and the presence of IgG suggested a latent form of toxoplasmosis in both the patient and control groups [16]. In a Brazil study, IgG and IgM antibodies determined that there was a higher prevalence of anti-T. gondii IgG in patients with schizophrenia than in a control group (91.18% vs. 70.59% of the control group) (p = 0.017). Interestingly, in this study, IgM anti-T. gondii antibodies the marker of an acute form of toxoplasmosis were not detected in any patient studied [17]. A cross-sectional study was conducted, in Egypt, with 177 individuals, where IgG and IgM anti-T. gondii antibodies from schizophrenic patients and a control group were determined. Toxoplasma antibodies among schizophrenic patients were higher (31.75%) as compared with the controls (14.55%). Only three patients, all with schizophrenia, had positive IgM antibodies [18].

A study conducted in Mexico, involving 137 hospitalized patients diagnosed with schizophrenia, 93 patients with acute psychiatric illness and 44 patients with chronic psychiatric disease, found that 25/137 (18.2%) of the psychiatric patients and 16/180 of the controls (8.9%) were positive for IgG anti-T. gondii antibodies. There was no statistically significant difference between acute and chronic schizophrenia [19]. Another study, also carried out in Mexico, used meta-analysis and found that the average prevalence of anti-Toxoplasma antibodies was 27.97% and the weighted prevalence was 19.27%; however, it was almost two times higher in mentally ill patients (38.52%) [20].

The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), developed by Overall and Gorham (1962), is used to assess changes in the symptoms of psychiatric patients. Depending on the version of the scale, there are a total of 18–24 symptoms and each symptom is rated on a scale from one to seven points [21].

In this study, we analyzed the prevalence of Toxoplasma infection in patients with schizophrenia and searched for the association of the Toxoplasma seropositivity with sociodemographic factors and the traits monitored by the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS).

2. Results

2.1. Anti-Toxoplasma Antibodies

Among 27 patients, the ELISA test results for Toxoplasma antibodies were negative in 12 and positive in 15 patients’ samples, which corresponded to a prevalence of 51.7%; Was higher than 27.97% in the general population, X2 = 32.42, (p < 0.0001); Is was also higher that prevalence reported in mentally ill patients 38.52%, X2 = 10.76, (p < 0.0005).

2.2. Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)

No association was detected between having high BPRS score (20 or more points on the BPRS scale) and being Toxoplasma seropositive and seronegative.

The relative frequencies (percentages) of the responses given by the patients, 15 positive and nine negative to Toxoplasma, as well as the items on the BPRS scale were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney test, no association significant differences in any symptom item of the BPRS with Fisher’s exact test (p = 0.057). When the mean scores for the BPRS items and the positivity for anti-Toxoplasma antibodies were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney test for the total of 27 patients, 18 items for 24 patients were analyzed and we found a statistically significant difference in Item 13 related to motor retardation with (p = 0.024). However, the association turned non-significant after of correction for multiple tests or after of analyzed with a logistic regression multivariate p = 0.059, odds ratio (OR) = 2.316 with a 95% confidence interval 2.316 [0.970 to 5.532] Table 1).

Table 1.

Mean of items in the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) and the seropositivity of anti-Toxoplasma antibodies.

| Items | Mean | ± | EE | Mean | ± | EE | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) |

Positive (>6 UI/mL) |

Negative (<6 UI/mL) |

Mann–Whitney | ||||

| BPRS01, somatic concern | 2.20 | ± | 0.38 | 2.11 | ± | 0.56 | 0.808 |

| BPRS02, psychic anxiety | 2.67 | ± | 0.41 | 3.78 | ± | 0.80 | 0.286 |

| BPRS03, emotional Isolation | 3.00 | ± | 0.47 | 2.67 | ± | 0.60 | 0.694 |

| BPRS04, conceptual disorganization (inconsistency) | 3.20 | ± | 0.52 | 3.89 | ± | 0.68 | 0.439 |

| BPRS05, self-contempt and feelings of guilt | 1.87 | ± | 0.50 | 1.78 | ± | 0.40 | 0.828 |

| BPRS06, tension and somatic anxiety | 2.67 | ± | 0.45 | 3.11 | ± | 0.61 | 0.549 |

| BPRS07, mannerism and strange postures | 2.20 | ± | 0.55 | 2.11 | ± | 0.56 | 0.885 |

| BPRS08, greatness | 1.87 | ± | 0.50 | 1.78 | ± | 0.57 | 0.903 |

| BPRS09, depressive humor | 2.20 | ± | 0.48 | 2.67 | ± | 0.44 | 0.310 |

| BPRS10, hostility | 2.64 | ± | 0.46 | 2.78 | ± | 0.70 | 0.986 |

| BPRS11, suspicion | 2.93 | ± | 0.51 | 3.22 | ± | 0.83 | 0.961 |

| BPRS12, hallucinations | 2.40 | ± | 0.56 | 3.33 | ± | 0.83 | 0.33 |

| BPRS13, motor retardation | 2.67 | ± | 0.30 | 1.56 | ± | 0.38 | 0.024* |

| BPRS14, lack of cooperation | 2.73 | ± | 0.41 | 2.33 | ± | 0.60 | 0.412 |

| BPRS15, unusual content of thought | 3.53 | ± | 0.54 | 3.89 | ± | 0.75 | 0.725 |

| BPRS16, dullness and affective flattening | 3.40 | ± | 0.40 | 3.11 | ± | 0.48 | 0.687 |

| BPRS17, excitement | 2.20 | ± | 0.55 | 1.56 | ± | 0.29 | 0.780 |

| BPRS18, disorientation and confusion | 1.40 | ± | 0.19 | 3.22 | ± | 0.83 | 0.067 |

2.3. Sociodemographic Data

There was a total of 12 women and 15 men in the sample studied. The distribution by age group was similar, i.e., approximately one-third of the patients were younger than 30, one-third were in the range from 30 to 49 years old, and the remaining third of adults were aged 50 and over. Non-statistically significant differences were observed in the distribution of age groups between genders with the chi-square test (X2) (p = 0.869) or with Fisher’s exact test (p = 0.893). The mean age of the women was 46.3 years with a standard deviation of ±17.5 years, the minimum age was 20 years, and the maximum age was 71 years; in the case of the men, the mean age was 38.3 ± 14.6 years with a minimum age of 16 years and a maximum age of 64 years. The median ages were 47.5 years for women and 33 years for men. When comparing the ages of men and women to the Student’s t-test and the Mann–Whitney non-parametric test, we did not observe any statistically significant differences (p = 0.207 and p = 0.261, respectively).

Concerning the schooling of the patients studied, 10 patients had elementary school studies, 5 patients had middle school studies, 4 patients had high school studies, only 1 patient had a college degree, and there were 7 patients who did not answer the question concerning schooling. Regarding occupation, the majority of patients did not work (22 cases), four patients were employees, and one patient was a merchant.

The associations between anti-Toxoplasma antibodies and sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender) were analyzed using contingency tables and no statistically significant effect was detected Table 2.

Table 2.

Age, gender and seropositivity of Toxoplasma gondii by ELISA, in psychiatric patients.

| No. (+) | % | No. (−) |

% | Total | p | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cat. | ||||||||

| Age group | 0.691 | |||||||

| <30 years | 4 | 50 | 4 | 50 | 8 | 0.391 | 0.429 | [0.062–2.972] |

| 30–49 years | 4 | 44 | 5 | 55.6 | 9 | 0.266 | 0.343 | [0.052–2.261] |

| 50 and over | 7 | 70 | 3 | 30 | 10 | 1 | 1 | - - - - - |

| Total | 15 | 55.6 | 12 | 44.4 | 27 | |||

| Gender | 0.707 | |||||||

| Male | 9 | 60 | 6 | 40 | 15 | 0.707 | 1.5 | [0.324–6.942] |

| Female | 6 | 50 | 6 | 50 | 12 | 1 | 1 | ----------------- |

| Total | 15 | 55.6 | 12 | 44.4 | 27 |

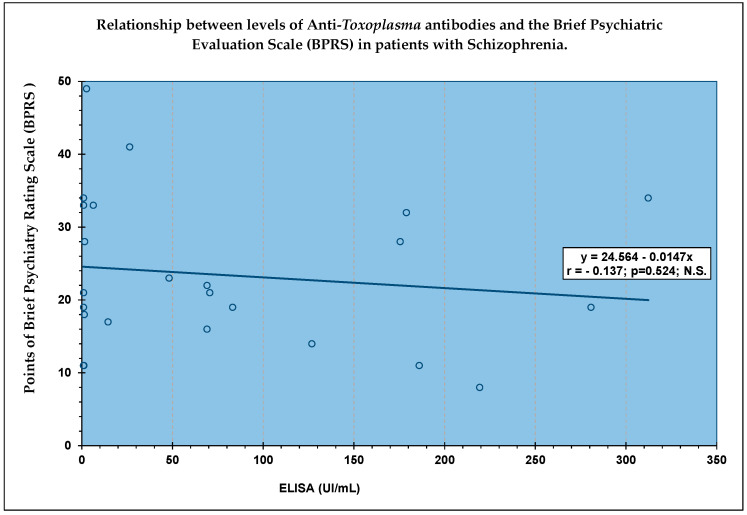

Finally, when using the Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficient between the ELISA results (UI/mL) and the Brief Psychiatric Assessment Scale to assess 24 schizophrenia patients, there was no relationship between these two measurements Figure 1.

Figure 1.

No significant correlation between the ELISA test results and the Brief 160 Evaluation Scale Psychiatric (BPRS) score in 24 patients.

3. Discussion

In our study, we found the current prevalence was 51.7%, which was higher than 27.97% in the general population, X2 = 32.42, (p < 0.0001); Is was also higher that prevalence reported in mentally ill patients the prevalence was 38.52%, which was significantly higher, X2 = 10.76, (p < 0.0005) [20,22].

We only determined IgG antibodies, since most studies have shown that Toxoplasma seropositivity in patients with schizophrenia was mainly associated with chronic infection [13,16,19]. There have been studies where IgM and IgG antibodies were determined, however, no patient was positive for IgM [17] or a minimal number of such subjects was present [18].

In this study, we investigated the associations of toxoplasmosis with each item on the BPRS. No association was significant after the correction for multiple tests. Toxoplasma infection of the brain undoubtedly affects neuro-inflammatory processes, including microglial activation, the levels of inflammatory cytokines, and the number of peripheral immune cells occurring during the infection. All these biochemical and cellular processes alter behavior in various ways and might affect the risk of schizophrenia and the course of the disease [23,24,25].

Our study, indeed, found an increased prevalence of toxoplasmosis in schizophrenia patients, however, the number of participants was probably not high enough for the detection of the effect of toxoplasmosis on the course of the disease.

Elevated antibody levels have also been linked to schizophrenia as compared with other patient groups [23,24]. The results of our study did not show a statistically significant correlation with antibody levels. One explanation for our results may be that they are latent-stage infections with low levels of IgG antibodies and a reactivation did not occur in which IgGs rise exponentially. Another possibility may be the different methods reported and their cut-off values [23], the probable explanation of this difference is the very small number of patients involved in our study.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patients

The inclusion criterion was the provision of a blood sample, which was obtained from 29 patients diagnosed with schizophrenia at the Psychiatric Service of the “Fray Antonio Alcalde” Civil Hospital in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico, from March to August 2019. That met the criteria of the Statistical Diagnostic Manual, fourth edition [21].

The exclusion criteria excluded patients who had a history of drug use or whose family did not accept their participation.

4.2. Clinical Aspects

The data obtained from patients were immunodeficiency, evidence of neurological disease, blood transfusion, transplants, behavior, and treatment.

4.3. Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)

The items on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale include the following; BPRS01, somatic concern; BPRS02, psychic anxiety; BPRS03, emotional isolation; BPRS04, conceptual disorganization (incoherence); BPRS05, self-contempt and guilt feelings; BPRS06, tension, somatic anxiety; BPRS07, mannerism and strange Postures; BPRS08, greatness; BPRS09, depressive humor; BPRS10, hostility; BPRS11, suspicion; BPRS12, hallucinations; BPRS13, motor retardation; BPRS14, lack of cooperation; BPRS15, unusual thought content; BPRS16, dullness, affective flattening; BPRS17, excitement; BPRS18, disorientation, confusion. Scores and meaning of the responses to the items comprising the Brief Psychiatric Assessment Scale (BPRS) are as follows: (1) not present, (2) very mild, (3) mild, (4) moderate (5) moderate-severe, (6) serious, and (7) very serious.

4.4. Sociodemographic Factors

The sociodemographic factors included age, birthplace, residence, marital status, occupation, educational level, and socioeconomic level [26].

4.5. Serological Testing for T. gondii Antibodies

Blood samples were processed in the Neurophysiology Laboratory at the University Center for Health Sciences, University of Guadalajara. The serum samples were obtained by centrifugation and kept frozen at –20 °C until they were processed. IgG anti-T. gondii (Platelia TM Toxo, Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France) antibody titers were determined in all samples by ELISA. Plates were read at 450/620 nm. Optical density values obtained were plotted along a standard curve to determine the levels of antibody titers (IU/mL). Samples with titers less than 6 IU/mL were considered to be negative and those with titers ranging from 9 to 200 IU/mL were considered to be positive for latent infection. Samples with values greater than 200 IU/mL were checked twice. All tests were performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

4.6. Statistical Analysis

SPSS Version 20.0 and SPSS (v. 18) packages (IBM, Los Angeles, CA, USA) were used to perform all statistical analysis. Quantitative variables included age, the BPRS scores, and the ELISA test results. The Shapiro–Wilk test of “normality” was applied as well as measures of central and dispersion tendency for the seropositivity ELISA results. The statistical significance between the two groups (positive vs. negative to ELISA) for the differences observed in these variables was obtained with the Student’s t-test for independent samples and with the Mann–Whitney U test. We calculated the Pearson (r) and Spearman (Rho) correlation coefficient between the ELISA values and the BPRS test scores. Linear regression was also performed between the total BPRS score and the ELISA values of these subjects.

The qualitative variables included age groups (under 30 years, 30–49 years, and 50 and older). There were two BPRS groups, i.e., schizophrenic patients with a BPRS score greater than or equal to 20 points and those patients with a score of less than 20 points.

Qualitative variables were analyzed using contingency tables, contrasting positive and negative results for ELISA from patients. The statistical significance with Fisher’s exact test and the odds ratio were also calculated. Multivariate analysis, namely the logistic regression, was also used for the assessment of the others factors.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the prevalence of latent toxoplasmosis observed in schizophrenia patients was significantly higher than that reported earlier for General population in Mexico. We did not found significant effects of toxoplasmosis on the symptoms of schizophrenia measured with BPRS, or a significant association of the Toxoplasma infection with any monitored factors. These negative outputs are most probably caused by rather low sample size.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank COECYTJAL and the Civil Hospital Fray Antonio Alcalde in Guadalajara.

Author Contributions

Experiments were conceived and designed by M.d.l.L.G.-R., G.N.M., and S.A.C.C.; clinical diagnostic and control of patients were performed by G.N.M. and S.A.C.C.; J.C.B.G. conducted interviews with patients, applied questionnaires, and prepared the database; L.R.R.P. completed immunoassays of anti-Toxoplasma antibodies; S.H.D.J. and J.M.D.J. revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was partially funded by the Support Program for the Improvement of Production Conditions for Members of the National System of Researchers 2018, University of Guadalajara (COECYTJAL grant number PSS788).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was registered with number CUCS/CINV/0457/17 and approved by the biosafety, research, and ethics committees of the University Center for Health Sciences at the University of Guadalajara.

Informed Consent Statement

All study participants and their tutors were informed about the purpose and procedures of the study and signed a written informed consent form.

Data Availability Statement

All data is in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Galván-Ramírez M.L., Madriz Elisondo A.L., Rico Torres C.P., Luna-Pastén H., Rodríguez Pérez L.R., Rincón-Sánchez A.R., Franco R., Salazar-Montes A., Correa D. Frequency of T. gondii in pork meat in Ocotlán, Jalisco, Mexico. J. Food Prot. 2010;73:1121–1123. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-73.6.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de la Luz Galván-Ramírez M., Flores R.M. Toxoplasmosis Humana. 1st ed. Ecorfan; Ciudad de México, México: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hlaváčová J., Flegr J., Řežábek K., Calda P., Kaňková Š. Male-to-Female Presumed Transmission of Toxoplasmosis between Sexual Partners. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2021;190:386–392. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwaa198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaskell E.A., Smith J.E., Pinney J.W., Westhead D.R., McConkey G.A. A Unique Dual Activity Amino Acid Hydroxylase in Toxoplasma gondii. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Novotná M., Hanusova J., Klose J., Preiss M., Havlicek J., Roubalová K., Flegr J. Probable neuroimmunological link between Toxoplasma and cytomegalovirus infections and personality changes in the human host. BMC Infect. Dis. 2005;6:54. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-5-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stibbs H.H. Changes in brain concentrations of catecholamines and indoleamines in Toxoplasma gondii infected mice. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 1981;79:153–157. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1985.11811902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Webster J.P., Lamberton P.H., Donnelly C.A., Torrey E.F. Parasites as causative agents of human affective disorders? The impact of anti-psychotic, mood-stabilizer and anti-parasite medication on Toxoplasma gondii ability to alter host behavior. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2006;273:1023–1030. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berdoy M., Webster J.P., Macdonald D.W. Fatal attraction in rats infected with Toxoplasma gondii. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2000;267:1591–1594. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vyas A., Kim S.K., Giacomini N., Boothroyd J.C., Sapolsky R.M. Behavioral changes induced by Toxoplasma infection of rodents are highly specific to aversion of cat odors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:6442–6447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608310104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skallová A., Kodym P., Frynta D., Flegr J. The role of dopamine in Toxoplasma-induced behavioural alterations in mice: An ethological and ethopharmacological study. Parasitology. 2006;133:525–535. doi: 10.1017/S0031182006000886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flegr J. Effects of Toxoplasma on human behavior. Schizophr. Bull. 2007;33:757–760. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yolken R.H., Bachmann S., Rouslanova I., Lillehoj E., Ford G., Torrey F., Schroeder J. Antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii in individuals with first-episode schizophrenia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001;32:842–844. doi: 10.1086/319221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shibre T., Alem A., Abdulahi A., Araya M., Beyero T., Medhin G., Deyassa N., Negash A., Nigatu A., Kebede D., et al. Trimethoprim as adjuvant treatment in schizophrenia: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Schizophr. Bull. 2010;36:846–851. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fond G., Boyer L., Schürhoff F., Berna F., Godin O., Bulzacka E. Latent Toxoplasma infection in real-world schizophrenia: Results from the national FACE-SZ cohort. Schizophr. Res. 2018;201:373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ansari-Lari M., Farashbandi H., Mohammadi F. Association of Toxoplasma gondii infection with schizophrenia and its relationship with suicide attempts in these patients. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2017;22:1322–1327. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stepanova E.V., Kondrashin A.V., Sergiev V.P., Morozova L.F., Turbabina N.A., Maksimova M.S., Morozov E.N. Toxoplasmosis and mental disorders in the Russian Federation (with special reference to schizophrenia) PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0219454. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morais F.B., Arantes T.E.F.e., Muccioli C. Seroprevalence and Manifestations of Ocular Toxoplasmosis in Patients with Schizophrenia. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2019;27:134–137. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2017.1408843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Hussainy N.H., Al-Saedi A.M., Al-Lehaibi J.H., Al-Lehaibi Y.A., Al-Sehli Y.M., Afifi M.A. Serological evidences link toxoplasmosis with schizophrenia and major depression disorder. J. Microsc. Ultrastruct. 2015;3:148–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jmau.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alvarado-Esquivel C., Mercado-Suarez M.F., Rodríguez-Briones A., Fallad-Torres L., Ayala-Ayala J., Nevarez-Piedra L., Duran-Morales E., Estrada-Martínez S., Liesenfeld O., Márquez-Conde J.A., et al. Seroepidemiology of infection with Toxoplasma gondii in healthy blood donors of Durango, Mexico. BMC Infect. Dis. 2007;7:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-7-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galvan-Ramirez M.d.L., Troyo R., Roman S., Calvillo-Sanchez C., Bernal-Redondo R. A systematic review and meta-analysis of Toxoplasma gondii infection among the Mexican population. Parasite Vectors. 2012;5:271. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frances A., Pincus H.A., Michael B. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC, USA: 2000. text reviewed, (DSM-IV-TR) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galván-Ramírez M.d.l.L., Rodríguez Pérez L.R., Ledesma Agraz S.Y., Ávila L.M.S., Armenta Ruíz A.S., Bayardo Corella D., Ramírez Fernández B.J., Sanromán R.T. Seroepidemiology of toxoplasmosis in high-school students in the metropolitan area of Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico. [(accessed on 6 April 2021)];Sci. Med. 2010 20:59–63. Available online: https://revistaseletronicas.pucrs.br/index.php/scientiamedica/article/view/5639. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emelia O., Amal R.N., Ruzanna Z.Z., Shahida H., Azzubair Z., Tan K.S., Adaila Noor S., Siri N.A.M., Aisah M.Y. Seroprevalence of anti-Toxoplasma gondii IgG antibody in patients with schizophrenia. Trop. Biomed. 2012;29:151–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muflikhah N.D., Supargiyono Artama W.T. Seroprevalence and Risk Factor of Toxoplasmosis in Schizophrenia Patients Referred to Grhasia Psychiatric Hospital, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Afr. J. Infect. Dis. 2018;7:76–82. doi: 10.21010/ajid.v12i1S.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Achaw B., Tesfa H., Zeleke A.J., Worku L., Addisu A., Yigzaw N., Tegegne Y. Sero-prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii and associated risk factors among psychiatric outpatients attending University of Gondar Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019;19:581. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4234-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bronfman M., Guiscafré H., Castro V., Castro R., Gutiérrez G. La medición de la desigualdad: Una estrategia metodológica, análisis de las características socioeconómicas de la muestra. Arch. Investig. Med. 1988;19:351–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data is in the manuscript.