Abstract

Purpose

To characterise the dynamics and consequences of bullying in academic medical settings, report factors that promote academic bullying and describe potential interventions.

Design

Systematic review.

Data sources

We searched EMBASE and PsycINFO for articles published between 1 January 1999 and 7 February 2021.

Study selection

We included studies conducted in academic medical settings in which victims were consultants or trainees. Studies had to describe bullying behaviours; the perpetrators or victims; barriers or facilitators; impact or interventions. Data were assessed independently by two reviewers.

Results

We included 68 studies representing 82 349 respondents. Studies described academic bullying as the abuse of authority that impeded the education or career of the victim through punishing behaviours that included overwork, destabilisation and isolation in academic settings. Among 35 779 individuals who responded about bullying patterns in 28 studies, the most commonly described (38.2% respondents) was overwork. Among 24 894 individuals in 33 studies who reported the impact, the most common was psychological distress (39.1% respondents). Consultants were the most common bullies identified (53.6% of 15 868 respondents in 31 studies). Among demographic groups, men were identified as the most common perpetrators (67.2% of 4722 respondents in 5 studies) and women the most common victims (56.2% of 15 246 respondents in 27 studies). Only a minority of victims (28.9% of 9410 victims in 25 studies) reported the bullying, and most (57.5%) did not perceive a positive outcome. Facilitators of bullying included lack of enforcement of institutional policies (reported in 13 studies), hierarchical power structures (7 studies) and normalisation of bullying (10 studies). Studies testing the effectiveness of anti-bullying interventions had a high risk of bias.

Conclusions

Academic bullying commonly involved overwork, had a negative impact on well-being and was not typically reported. Perpetrators were most commonly consultants and men across career stages, and victims were commonly women. Methodologically robust trials of anti-bullying interventions are needed.

Limitations

Most studies (40 of 68) had at least a moderate risk of bias. All interventions were tested in uncontrolled before–after studies.

Keywords: medical education & training, general medicine (see internal medicine), health services administration & management

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This systematic review is comprehensive, including 68 studies with 82 349 consultants and trainees, across several countries and including all levels of training.

We defined inclusion criteria a priori and used established tools to assess the risk of bias of included studies.

The included studies varied in their definitions of bullying, sampling bias was noted among the surveys and intervention studies were suboptimally designed.

Background

Bullying behaviours have been described as repeated attempts to discredit, destabilise or instil fear in an intended target.1 Bullying can take many forms from overt abuse to subtle acts that erode the confidence, reputation and progress of the victim.2 Bullying is common in medicine, likely impacting mental health, professional interactions and career advancement.3–6 It may also impact a physician’s ability to care for patients.7 Surveys from the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK showed that 55% of staff experienced at least one type of bullying; 31% were doctors in training.8 Bullying is closely related to harassment and discrimination, in which mistreatment is based on personal characteristics or demographics such as sex, gender or race.9 Within academic settings, victims may experience all three and the distinction may be less clear. Unlike harassment and discrimination, which have specific legal definitions, bullying is an amorphous term and victims are often left without legal recourse.

The hierarchical structure of academic medicine—in which there are power imbalances, subjective criteria for recruitment and career advancement, and siloed departments with few checks in place for toxic behaviours—may offer an operational environment in which bullying may be more widespread than in non-academic medical settings. Academic bullying is a seldom-used term within the literature, but is intended to describe the forms of bullying that may exist in academic settings. Academic bullying can be defined as mistreatment in academic institutions with the intention or effect of disrupting the academic or career progress of the victim.10 The prevalence of academic bullying in medical settings is unknown likely due to a lack of definition of bullying behaviours, a fear of reporting and insufficient research. There is not much known about the characteristics of perpetrators and victims, and about the impact of bullying on academic productivity, career growth and patient care. Furthermore, institutional barriers and facilitators of bullying behaviour have not been reported, and the effectiveness of interventions in addressing academic bullying has not been evaluated.

The purpose of this systematic review is to define and classify patterns of academic bullying in medical settings; assess the characteristics of perpetrators and victims; describe the impact of bullying on victims; review institutional barriers and facilitators of bullying; and identify possible solutions.

Methods

Data sources and searches

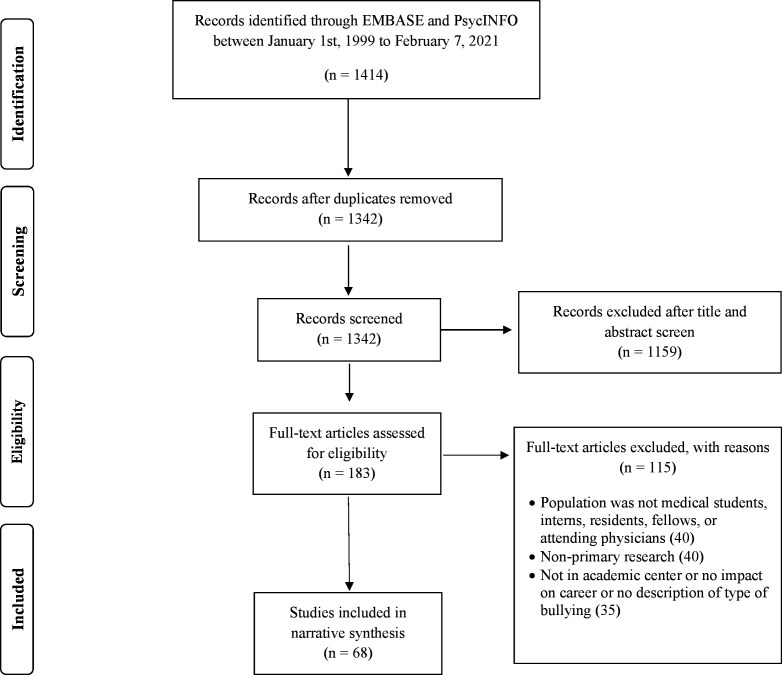

This study followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses reporting guidelines. Two reviewers (TA, YE) searched two online databases (EMBASE and PsycINFO) for English-language articles published between 1 January 1999 and 7 February 2021, and relevant to academic bullying in medicine. An outline of the search is provided in figure 1. A combination of medical subject heading, title, and abstract text terms encompassing ‘Medicine’; ‘Bullying’ and ‘Academia’ were used for the full search. The terms of the search are included in online supplemental figure S1. Two authors (TA, YE) independently screened articles for inclusion. Differences were resolved by discussion, and if necessary, by a third author (HGCVS).

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram of included studies. We identified 68 articles relevant to academic bullying. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

bmjopen-2020-043256supp001.pdf (31.6KB, pdf)

Study selection

We included studies conducted in academic medical settings in which victims were either consultants or trainees. We defined academic medical settings as hospitals or clinics that were either university affiliated or involved trainees. In the case of preclinical medical students, academic medical settings included the university where medical instruction took place. Studies were included if they described: the method and impact of bullying; the characteristics of perpetrators and victims; or interventions used to address the bullying. Studies that included trainees or consultants in both academic and non-academic settings were included. We excluded editorials, opinion pieces, reviews, conference abstracts, theses, dissertations and grey literature.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two reviewers (TA, YE) independently extracted data on: study design, setting (academic or non-academic), definition, description and impact of academic bullying, characteristics of perpetrators and victims, barriers and facilitators of bullying, and interventions and their outcomes. Two reviewers independently assessed studies for risk of bias. We assessed before–after studies using the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute quality assessment tool11 and assessed prevalence surveys using the Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tool.12 We classified survey studies as low risk of bias if at least 8 of 9 criteria were met, medium risk of bias if 7 of 9 were met, and high risk of bias if less than 7 were met. We classified bias in before–after studies as low if at least 11 of 12 criteria were met, medium if at least 9 of 12 were met, and high if less than 9 were met.

Data synthesis and analysis

We developed a definition for academic bullying through narrative synthesis of the definitions provided by studies included in this systematic review. We pooled the results of surveys on the basis of similarity of survey themes to facilitate a descriptive analysis. For survey studies on the prevalence or impact of bullying, we solely pooled the results of studies that asked respondents about specific bullying behaviours or impacts, respectively. We then separated results by gender and level of training. We classified groups ensuring consensus between authors. We presented our results as numbers and percentages. We calculated the denominators from the total number of individuals who completed surveys on types of bullying behaviours, the impact of bullying, characteristics of bullies and victims, or barriers to addressing academic bullying. The numerators were calculated from the number of individuals who experienced a specific behaviour or impact, were bullied by a perpetrator at a specified level of training or endorsed a specific reason for not making a formal report. We also reported the number of studies that described each specific bullying behaviour or impact, demographic characteristics of victims and perpetrators, barriers and facilitators of academic bullying, and specific reasons for not making a formal report. We could not perform a meta-analysis due to the conceptual heterogeneity between studies.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of our research.

Results

Screening results

We identified 1342 unique articles, 68 of which met inclusion criteria. Reasons for exclusion are described in figure 1.

Characteristics of included studies

Studies were most frequently set in the USA (reported in 31 studies)3 13–41 and the UK (reported in 5 studies)8 42–45 and were set in academic hospitals (reported in 54 studies)1 3–6 13–15 17 19–21 23 24 26 27 29 30 32–35 37–39 41–65 at both teaching and non-teaching sites (reported in 14 studies).8 16 25 28 36 40 66–73 Twenty-five studies included medical students,3–5 13 15 21 22 24 26 33–35 37 39 48 50 52 57–60 63 64 74 75 27 included residents or fellows1 14 16–18 20 22 23 25 27–32 44 45 49–51 55 56 61 62 65 69 72 and 25 included consultants6 8 16 19 20 25 28 36 38 40–43 46 47 53 66–73 75 (table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of studies investigating bullying in academic medicine

| Author (year), country | Study design | Setting | Definition of academic bullying | Target | Perpetrator | Source of bias | Risk of bias |

| Huber et al (2020), USA18 | Survey | Academic and non-academic hospitals | Data not provided | Residents | Consultant (83.0%) and resident (63.0%) | Inadequate sample size | Low |

| Hammoud et al (2020), USA22 | Survey | Academic hospitals | Study-based graduation questionnaire | Residents and medical students | For resident victims: consultant (58.7%), resident (27.9%), nurses (26.4%), other employees (10.2%) and administration (5.4%) For medical student victims: consultant (66.4%), resident (50.9%), nurses (22.4%), other employees (13.8%), administration (5.2%) and students (12.0%) |

Low response rate | Low |

| Balch Samora et al (2020), USA28 | Survey | Academic hospitals | A behaviour that a reasonable person would expect might victimise, humiliate, undermine or threaten a person to whom the behaviour is directed | Residents, fellows and consultants | Multiple* | Inappropriate statistical analysis and low response rate | Moderate |

| Brown et al (2020), Canada65 | Survey | Academic hospitals | Gender-based discrimination included belittling remarks, inappropriate comments and jokes, denial of opportunities, and behaviours that are perceived as hostile or humiliating | Residents | Nurses, consultants and residents | Inadequate sample size, analysis not conducted in full coverage of the sample, inappropriate identification of bullying and low response rate | High |

| Zhang et al (2020), USA29 | Survey | Academic and non-academic hospitals | NAQ† used | Residents | Consultants, co-residents, nurses and administrators | Study subjects not described in details | Low |

| Lind et al (2020), USA26 | Before–after | Academic | Public belittlement or humiliation; physical harm; denied opportunities for training or rewards, or receiving lower evaluations or grades, based solely on gender; and being subjected to racially or ethnically offensive remarks | Medical students | Data not provided | Unblinded outcome assessors, small sample size, high loss to follow-up and analysis of change score not applied | High |

| Colenbrander et al (2020), Australia64 | Survey | Academic hospitals | Data not provided | Medical students | Data not provided | Inadequate sample size, analysis plan, data analysis coverage and unreliable measurement of bullying | High |

| Iqbal et al (2020), Pakistan68 | Survey | Academic and non-academic hospitals | NAQ† used | Consultants | Data not provided | Inadequate sample size and statistical analysis | Moderate |

| Elghazally and Atallah (2020), Egypt63 | Survey | Academic | Behaviour that is intended to cause physical or psychological damage due to the imbalance of power, strength or status between the aggressor and the victim | Medical students | Professors (30.1%), students (51.2%) and staff (18.7%) | None | Low |

| Raj et al (2020), USA19 | Survey | Academic | Harassment defined as unwanted sexual advances, subtle bribery to engage in sexual behaviour, threats to engage in sexual behaviour or coercive advances* | Consultants | Data not provided | None | Low |

| Kemper and Schwartz (2020), USA17 | Survey | Academic and non-academic hospitals | Data not provided | Residents | Faculty (43.0%), clinical staff (60.0%), resident (28.0%), medical student (3.0%) and admin (9.0%) | None | Low |

| Stasenko et al (2020), USA16 | Survey | Academic and non-academic hospitals | Harassment is defined as an unwelcome sexual advances or other forms of physical and verbal aggression that is sexual in nature | Consultants and fellows | Data not provided | Low response rate | Low |

| Afkhamzadeh et al (2019), Iran75 | Survey | Academic hospitals | Physical or verbal violence, or bullying | Medical students and consultants | Data not provided | None | Low |

| Wolfman and Parikh (2019), USA32 | Survey | Academic and non-academic hospitals | Repeated negative actions and practices that are carried out as a deliberate act or unconsciously; these behaviours cause humiliation, offence and distress to the target | Residents | Data not provided | Inappropriate sampling frame, and identification of bullying condition, low response rate | High |

| Chowdhury et al (2019), USA31 | Survey | Academic and non-academic hospitals | NAQ† used | Residents | Data not provided | Inadequate sample size, description of subjects and setting and low response rate | High |

| Ayyala et al (2019), USA30 | Survey | Academic and non-academic hospitals | Harassment that occurs repeatedly (>once) by an individual in a position of greater power | Residents | Data not provided | Inappropriate methods of bullying identification | Low |

| Hu et al (2019), USA27 | Survey | Academic and non-academic hospitals | Discrimination and harassment on the basis of gender, race, or pregnancy or childcare | Residents | Consultants (52.4%), admin (1.1%), co-residents (20.2%) and nurses (7.9%) | None | Low |

| Brown et al (2019), International69 | Survey | Academic and non-academic hospitals | Data not provided | Residents or fellow and consultant | Data not provided | Inappropriate methods of bullying identification and low response rate | Moderate |

| Zurayk et al (2019), USA25 | Survey | Academic and non-academic clinics | Study-based sexual experience questionnaire | Consultants and residents | Residents (60.0%), lecturers (33.0%), professors (44.0%), nurses (10.0%) and hospital staff (29.0%) | Inadequate sample size, inappropriate sample frame | Moderate |

| Castillo-Angeles et al (2019), USA23 | Before–after | Academic hospital | Study-based abuse sensitivity questionnaire | Residents | Data not provided | Small sample size, inadequate blinding of outcome assessors and loss to follow-up | High |

| Kappy et al (2019), USA21 | Before–after | Academic hospital | Harassment; discrimination; humiliation; physical punishment; and the use of grading and other forms of assessment in a punitive manner | Medical students | Consultant, co-resident and nurse | Intervention and outcomes not well defined | Moderate |

| D’Agostino et al (2019), USA20 | Survey | Academic and non-academic hospitals | Abuse or harassment particularly of a sexual type | Residents, fellows and attending | Consultants (64.5%), co-resident (38.7%), ancillary staff (25.8%) | Inappropriate methods of bullying identification, inadequate statistical analysis plan and low response rate | High |

| Chung et al (2018), USA33 | Survey | Academic | Feeling of intimidation, dehumanisation, or threat to grade, or career advancement | Medical students | Attending physician (68.4%), resident (26.3%) and nurse (10.5%) | Inappropriate sample methods, non-validated method of bullying identification | High |

| Kemp et al (2018), USA34 | Survey | Academic hospital | Disrespect for the dignity of others that interferes with the learning process | Residents, consultants and fellows | Data not provided | Inadequate statistical analysis plan and low response rate | Moderate |

| Benmore et al (2018), England42 | Before–after | Academic hospital* | Data not provided | Residents | Senior consultants | Insufficient enrolment, inadequate sample size, no blinding of outcome assessors, high loss to follow-up, lack of statistical analysis or ITS design | High |

| Duru et al (2018), Turkey46 | Survey | Academic hospital | Data not provided | Consultants, researchers, administrators, nurses | Specific occupations of bullies not specified | Inappropriate sampling and inadequate sample size | Moderate |

| Chambers et al (2018), New Zealand47 | Survey | Academic and non-academic hospitals | Data not provided | Specialist consultants | Primarily men. Senior medical staff (52.5%), non-clinical managers (31.8%) and clinical leaders (24.9%) | Low response rate | Low |

| House et al (2018), USA24 | Before–after | Academic hospital | Data not provided | Medical students | Faculty most frequently were the source of bullying followed by residents. Exact breakdown not specified | Insufficient enrolment, inadequate sample size, no blinding of outcome assessors, outcomes not clearly described, lack of statistical analysis, individual-level analysis or ITS design | High |

| Kulaylat et al (2017), USA5 | Survey | Academic hospital | Verbal abuse, specialty-choice discrimination, non-educational tasks, withholding/denying learning opportunities, neglect and gender/racial insensitivity | Medical students | Faculty (57.0%), residents, fellows (49.0%) and nurses (33.0%) | Inappropriate sampling, inadequate sample size, classification bias, and non-validated identification or measurement of bullying | High |

| Malinauskiene et al (2017), Lithuania6 | Survey | Academic hospitals | Data not provided | Family consultants | Supervisor (25.3%), colleague (9.8%), subordinate (2.9%) | Inappropriate sampling, inadequate sample size and coverage bias | Moderate |

| Chrysafi et al (2017), Greece70 | Survey | Academic and non-academic hospitals | Data not provided | Consultants | Surgeons most frequently followed by internal medicine consultants, then radiologists/laboratory consultants | Low response rate and coverage bias | Moderate |

| Kapoor et al (2016), India58 | Survey | Academic hospital | Data not provided | Medical students | Data not provided | Inappropriate sampling and inadequate description of study population | Moderate |

| Chadaga et al (2016), USA14 | Survey | Academic hospitals | NAQ† used | Residents and fellows | Consultants (29.0%), nurses (27.0%), patients (23.0%), peers (19.0%) | Low response rate, inadequate sample size and coverage bias | Moderate |

| Llewellyn et al (2016), Australia62 | Survey | Academic hospitals | Data not provided | Residents | Senior medical staff: (58.3%) in 2015, (60.6%) in 2016 Non-medical staff: (33.2%) 2015, (33.9%) 2016 Manager: (5.2%) in 2015, (1.2%) in 2016 Junior resident: (3.3%) in 2015, (4.3%) in 2016 |

Low response rate, biased sampling, coverage and classification bias | High |

| Rouse et al (2016), USA36 | Survey | Academic clinics | NAQ used | Family medicine consultants | Data not provided | Low response rate | Low |

| Shabazz et al (2016), UK43 | Survey | Academic and non-academic hospitals | Belittle and undermine an individual’s work; undermining an individual’s integrity; persistent and unjustified criticism and monitoring of work; freezing out, ignoring or excluding and continual undervaluing of an individual’s effort | Gynaecology consultants | Senior consultants (50.9%), junior consultants (22.3%), medical director (4.5%) | Low response rate and classification bias | Moderate |

| Peres et al (2016), Brazil59 | Survey | Academic hospital | Data not provided | Medical students | Data not provided | Low response rate and classification bias | Moderate |

| Ling et al (2016), Australia49 | Survey | Academic hospitals | NAQ used | General surgery residents and consultants | For trainee victims: staff surgeon (48.0%), trainee surgeon (13.0%), admin (13.0%), nurses (11.0%), other consultants (6.0%) For consultant victims: (31.0%) staff surgeons, (28.0%) admin, (13.0%) other consultants, (11.0%) nurses, other (10.0%), trainees (4.0%) |

Low response rate | Low |

| Kulaylat et al (2016), USA37 | Before–after | Academic hospital | Data not provided | Medical students | Faculty (57.0%), residents/fellows (49.0%) and nurses (33.0%) | Inadequate sample size, no blinding of outcome assessors | Moderate |

| Ahmadipour and Vafadar (2016), Iran50 | Survey | Academic hospital | Being assigned tasks as punishment, being threatened with an unjustly bad score or failure | Medical students, interns and residents | Data not provided | Inadequate sample size | Low |

| Jagsi et al (2016), USA38 | Survey | Academic hospital | Data not provided | Consultants who won a career advancement award | Data not provided | Inadequate sampling frame and classification bias | Moderate |

| Crebbin et al (2015), Australia and New Zealand72 | Survey | Academic hospitals | Data not provided | Residents, fellows and consultants | Surgical consultants (50.0%), other medical consultants (24.0%) and nursing staff (26.0%) | Low response rate | Low |

| Cresswell et al (2016), UK44 | Before–after | Academic hospital | Data not provided | Residents | Data not provided | Insufficient description of study purpose, inadequate enrolment and sample size, no blinding of outcome assessors, outcomes not clearly described, lack of statistical analysis or ITS design and high loss to follow-up | High |

| Loerbroks et al (2015), Germany51 | Survey | Academic hospitals | Data not provided | Residents | Data not provided | None | Low |

| Malinauskiene and Bernotaite (2014), Lithuania73 | Survey | Non-academic clinics | NAQ used | Family medicine consultants | Bullying from patients (11.8%), from colleagues by (8.4%), from superiors by (26.6%) | None | Low |

| Mavis et al (2014), USA15 | Survey | Academic hospitals | Mistreatment either intentional or unintentional occurs when behaviour shows disrespect for the dignity of others and unreasonably interferes with the learning process | Medical students | Clinical faculty in the hospital (31.0%) residents/interns (28.0%), nurses (11.0%) | Low response rate, inadequate description of study population and statistical analysis | Moderate |

| Oser et al (2014), USA13 | Survey | Academic hospital | Data not provided | Medical students | Residents>clerkship faculty>other attendings>other students>preceptors =nurses | None | Low |

| Oku et al (2014), Nigeria4 | Survey | Academic hospital | Data not provided | Medical students | Medical students (23.7%), consultants (21.7%), lecturers (17.5%), consultants (16.5%), nurses (16.5%), other staff (4.1%) |

None | Low |

| Gan and Snell (2014), Canada60 | Survey | Academic hospital | Data not provided | Medical students | Consultants | Low response rate, inappropriate sampling, small sample size and classification bias | High |

| Fried et al (2015), USA3 | Before–after | Academic hospital | Power mistreatment defined as made to feel intimidated, dehumanised, or had a threat made about a recommendation, your grade, or your career | Medical students | Residents (49.7%), clinical faculty (36.9%), preclinical faculty (7.9%) | None | Low |

| Al-Shafaee et al (2013), Oman48 | Survey | Academic hospitals | Being coerced into carrying out personal services unrelated to the expected role of interns and instances in which interns were excluded from reasonable learning opportunities offered to others, or threatened with failure or poor evaluations for reasons unrelated to academic performance | Residents | Internal medicine (60.3%), surgery (29.0%), paediatrics (15.5%), specialists (51.7%), consultants (50.0%), residents (12.1%), nurses (24.1%) | Inappropriate sampling, inadequate sample size, inadequate description of study population and coverage bias | High |

| Owoaje et al (2012), Nigeria52 | Survey | Academic hospital | Data not provided | Medical students | Consultants (69.1%), residents/fellows (52.4%), other students (15.7%), nurses (7.8%), laboratory technicians (4.1%) | Low response rate | Low |

| Askew et al (2012), Australia66 | Survey | Academic and non-academic hospitals | Data not provided | Consultants | Consultants (44.0%), managers (27.0%), patients (15.0%), nurses/midwives (4.0%), junior consultants (1.0%) | Low response rate | Low |

| Meloni and Austin (2011), Australia53 | Before–after | Academic hospital | Data not provided | Hospital employees | Data not provided | Lack of blinding of outcome assessors, high loss to follow-up, lack of statistical analysis or ITS design, and unit of analysis not clearly described | High |

| Dikmetas et al (2011), Turkey61 | Survey | Academic hospital | Data not provided | Residents | Surgeons>internists | Low response rate | Moderate |

| Eriksen et al (2011), Norway67 | Survey | Academic hospital | NAQ used | Hospital employees | Colleagues; specific occupations not described | Low response rate, inappropriate sampling and inadequate statistical analysis | Moderate |

| Imran et al (2010), Pakistan54 | Survey | Academic hospitals | Threats to professional status, threats to personal standing, isolation, overwork and destabilisation | Residents | Consultants | Inappropriate sampling, classification and coverage bias | Moderate |

| Ogunsemi et al (2010), Nigeria55 | Survey | Academic hospital | Data not provided | Residents | Administrative staff (58.0%), from the hospital chief executive (41.4%), from patient relatives (40.4%), nurses (32.7%), residents (30.0%), patients (20.0%) | Inadequate sample size | Low |

| Best et al (2010), USA39 | Before–after | Academic hospital | Data not provided | Unspecified | Data not provided | Study purpose not clearly described, insufficient enrolment, no blinding of outcome assessors, lack of statistical or individual-level analysis or ITS design | High |

| Nagata-Kobayashi et al (2009), Japan56 | Survey | Academic hospitals | Assigned you tasks as punishment; threatened to fail you unfairly in residency; competed maliciously or unfairly with you; made negative remarks to you about becoming a consultant or pursuing a career in medicine | Residents | Surgery (27.6%), internal medicine (21.4%), emergency medicine (11.5%), anaesthesia (11.3%), consultants (34.1%), patients (21.7%), nurses (17.2%) | Low response rate | Low |

| Scott et al (2008), New Zealand1 | Survey | Academic hospital | A threat to professional status and personal standing, isolation, enforced overwork, destabilisation | Residents | Consultants (30.0%), nurses (30.0%), patients (25.0%), radiologists (8.0%), residents/fellows (7.0%) | Low response rate, inadequate sample size and description of study population | Moderate |

| Gadit and Mugford (2007), Pakistan71 | Survey | Academic and non-academic hospitals | Data not provided | Consultants | Senior colleagues | Inadequate sample size | Low |

| Shrier et al (2007), USA40 | Survey | Academic and non-academic hospitals | Data not provided | Consultants | Colleagues (24.0%), patients (19.0%), teachers (18.0%), supervisors (15.0%) | Inappropriate sampling, inadequate sample size and coverage bias | Moderate |

| Cheema et al (2005), Ireland45 | Survey | Academic hospitals | Data not provided | Residents | Senior residents (51.0%–70.0%), nursing staff (47.0%–59.0%), administration (15.0%–16.0%), colleagues (12.0%–13.0%) | Low response rate | Low |

| Rautio et al (2005), Finland57 | Survey | Academic hospital | Data not provided | Medical students | Lecturers (27.9%), research/senior research fellows (27.7%), professors (16.6%), associate professors (13.6%) | Low response rate, inappropriate sampling, inadequate sample size and coverage bias | High |

| Wear and Aultman (2005), USA35 | Survey | Academic hospital | Data not provided | Medical students | General surgeons and obstetricians | Low response rate, inappropriate sampling, inadequate sample size, classification and lack of validated measurement tool | High |

| Carr et al (2000), USA41 | Survey | Academic hospitals | Data not provided | Consultants | Superiors and colleagues | None | Low |

| Quine (1999), UK8 | Survey | Non-academic clinics | Data not provided | Consultants | 54.0% greater seniority, 34.0% same seniority, 12.0% less senior; 49.0% of bullies older than victims | None | Low |

Academic hospitals/clinics were defined as teaching hospitals/clinics with a university affiliation.

*Regarding sexual harassment: the most common sources were attending surgeons (69% overall, 71% women, 18% men); trainees (46% overall, 47% women, 9% men); attending non-surgical (22%, 22% women, 18% men); other allied health professionals (16%, 15% women, 36% men); nursing (14%, 12% women, 73% men); admin staff (4%, 2% women, 36% men). Regarding harassing behaviours: the most common sources were attending orthopaedic surgeons (76% overall, 75% women, 86% men); trainees (30%, 32% women, 14% men); attending physicians; non-surgical (eg, anaesthesiologist, internist) (20%, 21% women, 11% men); nursing staff (18%,18% women, 20% men); administration staff (13%, 12% women, 17% men); and other allied health professionals (9%, 10% women, 9% men).

†The NAQ is a validated tool for assessing the prevalence of workplace bullying.

ITS, interrupted time series; NAQ, Negative Acts Questionnaire.

Definition of academic bullying

Six papers provided definitions for academic bullying.33 48 50 56 58 63 Common behaviours included abusing and punishing the victim through overwork, isolation, blocked career advancement and threats to academic standing. Thus, we defined academic bullying as the abuse of authority by a perpetrator who targets the victim in an academic setting through punishing behaviours that include overwork, destabilisation, and isolation in order to impede the education or career of the target. Multiple studies used the complete or partial Negative Acts Questionnaire, a standardised list of bullying behaviours (reported in 24 studies).1 3 4 6 13–15 24 29 31 36 47–52 54 55 57 60 61 67 73

Patterns of academic bullying behaviours

There were 35 779 consultant and trainee respondents to surveys of bullying behaviours (reported in 28 studies), but not all were offered the same options to select from (table 2). Bullying behaviours were grouped into destabilisation (reported in 15 studies), threats to professional status (reported in 23 studies), overwork (reported in 7 studies) and isolation (reported in 17 studies). Undue pressure to produce work was commonly reported (38.2% of respondents affected, reported in 7 studies).14 36 45 47 49 54 67 Of the 15 studies that described destabilisation, common methods included being ordered to work below one’s competency level (36.1%, reported in 10 studies)31 36 45 47–49 52 67 71 72 and withholding information that affects performance (30.7%; reported in 9 studies).14 29 31 36 47–49 54 67 Of the 23 studies that described threats to professional status, common methods were excessive monitoring (28.8%; reported in 6 studies)14 36 47 49 54 67 and criticism (26.9%; reported in 12 studies).14 21 29 36 45 47 49 52 54 67 71 72 Of the 17 studies that described isolation, the most common method was social and professional exclusion (29.1%; reported in 17 studies).4 14 21 24 29 31 36 40 47–49 52 54 63 67 70 72

Table 2.

Self-reported description of specific bullying behaviours

| Behaviour | No of studies/ total studies* |

Total cohort No affected/total participants who completed surveys on behaviours (%)* |

Men No affected/total men who completed surveys on behaviours (%)† |

Women No affected/total women who completed surveys on behaviours (%)† |

| Threats to professional status | ||||

| Persistent unjustified criticism | 12/28 | 4495/16 700 (26.9) | 535/1690 (31.7) | 552/1402 (39.4) |

| Excessive monitoring of work | 6/28 | 1752/6079 (28.8) | 442/1525 (27.7) | 441/1298 (34.0) |

| Intimidatory use of discipline | 15/28 | 1531/19 471 (7.9) | 366/2381 (15.4) | 363/2209 (16.4) |

| Spread of gossip/rumours | 7/28 | 2977/10 060 (29.6) | 88/596 (14.8) | 94/453 (20.8) |

| False allegations | 6/28 | 613/3796 (16.1) | 59/596 (9.9) | 54/453 (11.9) |

| Refusal of leave, training or promotion | 9/28 | 1604/8551 (18.8) | 296/2594 (11.4) | 458/2340 (19.6) |

| Isolation | ||||

| Social/professional exclusion | 17/28 | 6160/21 099 (29.1) | 420/2027 (20.7) | 1064/2814 (37.8) |

| Overwork | ||||

| Undue pressure to produce work | 7/28 | 2509/6562 (38.2) | 233/1525 (15.3) | 355/1570 (22.6) |

| Setting impossible deadlines | 6/28 | 1571/6079 (25.8) | 164/1525 (10.8) | 189/1298 (14.6) |

| Destabilisation | ||||

| Shifting goalposts | 1/28 | 54/417 (12.9) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Removal of areas of responsibility without consultation | 8/28 | 1397/6193 (22.6) | 160/1525 (10.5) | 171/1298 (13.2) |

| Withholding information that affects performance | 9/28 | 3836/12 503 (30.7) | 219/1553 (14.1) | 267/1328 (20.1) |

| Ordered to work below one’s competence level | 10/28 | 2934/8119 (36.1) | 81/625 (13.0) | 99/483 (20.5) |

*Total number of studies that described types of bullying behaviours, including studies that did not stratify results by sex. As a result, the denominator for the number of participants in total is not the sum of the denominators for men and women. The denominator was calculated from the total number of individuals who completed surveys on specific bullying behaviours, while the numerator was calculated from the number of individuals who indicated they experienced the specified bullying behaviour. Not all survey studies offered respondents the same options to respond to, and as a result the denominators for each bullying behaviour differ.

†Of the studies that separated data by gender or solely included the results of one gender and included the specified bullying behaviour.

There were 6179 consultant and trainee respondents to surveys that separated the prevalence of bullying behaviours by gender (reported in 11 studies). A greater proportion of women experienced all bullying behaviours (reported in 11 studies)14 16 19 22 36 40 48 52 57 63 65 (table 2). There were 34 175 respondents to surveys that analysed results by level of training (reported in 24 studies) (online supplemental table S1). A greater proportion of consultants experienced refusal of applications for leave, training or promotion (26.3%, reported in 3 studies),19 36 47 and removal of areas of responsibility (27.8%, reported in 2 studies)36 47 than residents (11.0%, reported in 3 studies; 10.7%, reported in 3 studies, respectively)14 22 54 55 or medical students (13.4%; 19.6%, reported in 1 study).22 24 Compared with medical students (4.6%, reported in 6 studies)13 15 22 24 52 57 and consultants (3.4%, reported in 2 studies),36 71 a greater proportion of residents experienced the intimidatory use of discipline procedures (17.8%, reported in 6 studies).14 22 48 54 55 65 A greater proportion of medical students experienced persistent criticism (66.4%, reported in 2 studies)21 52 than residents (28.3%, reported in 5 studies)14 29 45 54 72 and consultants (20.8%, reported in 3 studies).36 47 71

bmjopen-2020-043256supp002.pdf (76.8KB, pdf)

Characteristics of bullies

Thirty-one unique studies representing 15 868 consultants and trainees described the characteristics of bullies, although not all were offered the same options to select from. Common perpetrators included consultants (53.6%, reported in 30 studies),1 3 4 6 8 14 15 17 18 20 22 27 28 33 37 40 43 45 47–49 52 54 56 60 62 63 66 72 73 residents (22.0%, reported in 22 studies)1 3 6 8 15 17 18 20 22 25 27 28 33 37 45 48 49 54 56 60 62 and nurses (14.9%, reported in 21 studies).1 3 4 14 15 17 20 22 25 27 28 33 37 45 48 49 54 56 60 62 73 Of the 4277 individuals who identified the gender of their bullies, most reported primarily men (67.2%, reported in 5 studies),8 36 43 47 72 followed by primarily women (26.1%, reported in 5 studies),8 36 43 47 72 and both (6.7%, reported in 3 studies).8 43 47 Among 6084 medical students, perpetrators were commonly consultants (43.1%, reported in 8 studies),3 4 15 22 33 37 52 60 residents (35.7%, reported in 6 studies),3 15 22 33 37 60 nurses (12.4%, reported in 7 studies)3 4 15 22 33 37 60 and other medical students (8.8%, reported in 5 studies).3 4 22 52 63 Among 6289 residents, perpetrators were commonly consultants (52.2%, reported in 12 studies),1 14 17 18 22 27 45 48 49 54 56 62 nurses (24.3%, reported in 11 studies)1 14 17 22 27 45 48 49 54 56 62 and other residents (20.6%, reported in 12 studies).1 14 17 18 22 27 45 48 49 54 56 62 Of the 1500 consultants, perpetrators were their peers (39.2%, reported in 7 studies),6 8 40 47 49 66 73 senior consultants (23.7%, reported in 5 studies)6 8 40 43 73 and administration (17.7%, reported in 4 studies).43 47 49 66

Six unique studies representing 1698 interns and medical students described the prevalence of academic bullying according to the specialty rotation of the learner. Academic bullying was common in surgery (32.9% of respondents, reported in 6 studies),1 13 34 48 56 60 72 obstetrics and gynaecology (25.5%, reported in 2 studies)13 60 and internal medicine (21.4%, reported in 5 studies).1 13 48 56 60 72

Characteristics of victims

Forty-one unique studies described the characteristics of victims, and 29 included the proportion of those who experienced bullying. Of the 15 704 women and 19 495 men who responded to surveys that analysed results by gender, women were more likely to report being bullied than men (54.6% of all women compared with 34.2% of all men, reported in 27 studies).3 4 14 16 17 19 20 27 28 36 38 41 47–52 55–57 62 63 65 69 72 75 There were 10 730 consultant and trainee respondents to surveys that separated the results by demographic characteristics other than gender, but not all characteristics were captured by each study. A greater proportion of international graduates/non-citizens experienced bullying than citizens (48.0% compared with 43.3%, reported in 4 studies),14 17 45 72 and a greater proportion of overweight participants (body mass index (BMI) >25) experienced bullying than those with a BMI ≤25 (17.8% compared with 11.8%, reported in 1 study).51 The relationship between age and bullying varied based on the cut-off used and the survey sample in each study. Among consultants, a greater proportion of those with full professorship experienced bullying than assistant professors (68.0% compared with 51.9%, reported in study).41

Impact of academic bullying

There were 24 894 consultant and trainee respondents to surveys on the psychological (reported in 20 studies) and career impact (reported in 25 studies) of academic bullying (table 3), although not all were offered the same options to select from. Respondents commonly reported psychiatric distress (39.2%; reported in 14 studies),6 17 18 27 29 30 43 47 52 56 59 62 71 73 considerations of quitting (35.9%; reported in 7 studies)25 31 43 47 66 70 72 and reduced clinical ability (34.6%; reported in 8 studies).25 30 31 45 47 52 56 59 Respondents agreed that academic bullying negatively affected patient safety (68.0%; reported in 2 studies).18 31 Nine studies representing 13 418 individuals described the impact of bullying according to gender (table 3). A greater proportion of women experienced loss of career opportunities (43.6%, reported in 8 studies),16 19 36 38 40 41 52 65 while a greater proportion of men experienced decreased confidence (32.1%, reported in 2 studies)41 52 and clinical ability (26.1%, reported in 1 study).52

Table 3.

Self-reported impact of academic bullying

| Effect of academic bullying | No of studies/ total studies* |

Total cohort No of affected participants/total participants who completed surveys on the impact of bullying (%)* |

Men No of affected men/total men who completed surveys on the impact of bullying (%)† |

Women No of affected women/total women who completed surveys on the impact of bullying (%)† |

| Psychological | ||||

| Psychological distress including depressive/PTSD symptoms | 14/33 | 5597/14 285 (39.1) | 1750/5172 (33.8) | 1636/3529 (46.4) |

| Reduced confidence in clinical skill | 8/33 | 564/2112 (26.7) | 68/212 (32.1) | 97/597 (16.2) |

| Career | ||||

| Missed career opportunities | 17/33 | 2823/9442 (29.9) | 357/1898 (18.8) | 1104/2530 (43.6) |

| Considerations of quitting | 7/33 | 1034/2880 (35.9) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Termination of employment | 5/33 | 228/4419 (5.2) | 4/139 (2.9) | 4/150 (2.7) |

| Leave of absence | 2/33 | 50/748 (6.7) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Self-reported worsening of clinical performance | 8/33 | 1673/4841 (34.6) | 42/161 (26.1) | 22/101 (21.8) |

*Total number of studies that described the impact of bullying, including studies that did not stratify results by gender. Not all participants were given the same options to select from.

†Of the studies that separated data by gender or solely included the results of one gender and included the impact of bullying.

PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

There were 16 523 consultant and trainee respondents to surveys that separated results by level of training (online supplemental table S2). A greater proportion of medical students experienced psychiatric distress (72.9%; reported in 2 studies)52 59 than residents (40.8%; reported in 6 studies)17 18 29 30 56 62 and consultants (17.9%; reported in 4 studies).43 47 71 73 A greater proportion of residents endorsed loss of career opportunities (35.0%; reported in 3 studies)55 65 72 compared with medical students (16.0%; reported in 3 studies)13 15 52 and consultants (30.6%; reported in 8 studies).19 36 38 40 41 47 70 71

Barriers and facilitators of academic bullying

Thirty-five unique studies pertained to barriers to victims making a formal report (reported in 26 studies) and institutional facilitators (reported in 25 studies) of academic bullying (table 4). There were 9239 consultant and trainee respondents to surveys on their actions taken in response to bullying and reasons for not making a formal report, although not all were given the same options to select from. Victims commonly did not formally report the bullying1 3 4 15 36 43 47 49 50 54 56 60 62 66 72; only 28.9% of respondents made a formal report. Deterrents to reporting included concern regarding career implications (41.1%; reported in 15 studies),1 4 15 25 28 35 47 48 50 56 62 65 66 70 72 not knowing who to report to (26.5%; reported in 15 studies)1 4 16 22 25 33 47 48 50 56 62 65 66 70 75 and poor recognition of bullying (11.4%; reported in 5 studies).5 15 25 33 35 37 42 48 56 Of the 26 studies, 7 studies representing 1139 individuals reported the outcomes of reporting1 36 43 47 49 65 72 although only a small range of outcomes were offered among options. Submitting a formal report often had no perceived effect on bullying (35.6%; reported in 5 studies)36 43 47 49 72; a greater proportion of victims endorsed worsening (21.9%; reported in 3)36 49 65 than improvement (13.7%; reported in 5 studies)1 36 43 49 72 in bullying following reporting.

Table 4.

Barriers to addressing academic bullying

| Barrier | No of studies/total studies* | No of participants/total participants (%) |

| Low reporting rates | ||

| Lack of awareness of what constitutes bullying | 5/35 | 73/642 (11.4) |

| Lack of awareness of reporting process | 15/35 | 1115/4215 (26.5) |

| Lack of perceived benefit | 9/35 | 667/1621 (41.1) |

| Fear that bullying would worsen | 13/35 | 969/2696 (35.9) |

| Fear of career ramifications | 15/35 | 1094/2664 (41.1) |

| Concerns regarding confidentiality | 4/35 | 56/445 (12.6) |

| Institutional factors | ||

| Hierarchical nature of medicine | 7/35 | Not reported |

| Recurring cycle of abuse | 3/35 | Not reported |

| Normalisation of bullying | 10/35 | Not reported |

| Lack of enforcement | 13/35 | 586/1400 (41.9) |

*Total number of studies that described barriers of bullying behaviours.

In the 25 unique studies that described institutional facilitators of bullying, common facilitators were lack of enforcement (reported in 13 studies),1 16 20 25 28 36 43 47 49 50 54 56 65 the hierarchical structure of medicine (reported in 7 studies)26 54 56 57 63 64 71 and normalisation of bullying (reported in 10 studies).3 15 19 23 26 31 34 47 62 65 Individual-level data were not pooled as institutional facilitators of bullying were most commonly elicited via free-response portions of surveys with varying completion rates.

Suggested strategies, interventions and outcomes

Forty-nine unique studies suggested strategies to address academic bullying. These strategies included promoting anti-bullying policies (reported in 13 studies),3 14–16 35 45 53 54 56 58 59 66 71 education to prevent academic bullying (reported in 20 studies),1 3 4 14 15 20 25 26 31 33 35 45 48 54 59 63–65 71 72 establishing an anti-bullying oversight committee (reported in 10 studies),21 22 26 28 30 34 39 58 69 71 institutional support for victims (reported in 5 studies)35 46 58 62 72 and internal reviews in which hospitals develop targeted solutions for their environment (reported in 5 studies)15 22 24 60 63 (online supplemental table S3).

Of the 49 unique studies, 10 implemented organisation-level interventions which included workshops with vignettes to improve recognition of bullying (reported in 4 studies)23 37 42 44; a gender and power abuse committee that established reporting mechanisms and held mandatory workshops on mistreatment (reported in 1)3; a gender equity office to handle reporting (reported in 1)39; a professionalism-focused approach that included professionalism in employee contracts and performance reviews, and a professionalism office to handle student complaints (reported in 1)26; zero-tolerance policies (reported in 1)53 and institutional-level tracking of mistreatment to provide targeted staff education (reported in 2).21 24 All 10 studies had an uncontrolled before–after design, and as such, did not establish causality. In the studies of vignettes, common bullying behaviours were demonstrated to improve recognition of both subtle and overt acts of bullying. Of the 4 studies that involved bullying recognition workshops, 3 reported an associated improvement in bullying recognition.37 42 44 In a study that developed a gender equity office, reporting was handled through an intermediary; decisions were binding with consequences for retaliation including termination of employment39 and 96% of all formal reports were resolved. In a study where a gender and power abuse committee was formed, there was an associated reduction in academic abuse.3 Similarly, in a study that used a multifaceted approach of developing a professionalism committee, and including professionalism in contracts and performance reviews, there was a 35.9% decrease in reporting of mistreatment and improved awareness of the reporting process.26 In a study where a clerkship committee monitored unprofessionalism, there was an associated reduction in narrative comments regarding unprofessionalism on end of rotation surveys.21 In a study assessing the impact of a professionalism retreat about mistreatment for consultants, there was no reduction in medical student mistreatment.13 In a study assessing the implementation of zero-tolerance policies, there was an associated improvement in awareness of bullying reporting processes.53

Assessment of bias

Twenty-eight studies had a low risk of bias,3 4 8 13 16–19 22 27 29 30 36 41 45 47 49–52 55 56 63 66 71–73 75 21 had a moderate risk of bias1 6 14 15 21 25 28 34 37 38 40 43 46 54 58 59 61 67–70 and 19 had a high risk of bias.20 23 24 26 31–33 35 37 39 42 44 48 53 57 60 62 64 65 Among the 58 survey studies, 14 sampled participants inappropriately,5 6 14 19 33 35 40 46 48 54 57 58 60 62 67 19 had inadequate sample sizes or did not justify their sample size,1 5 6 14 18 25 31 35 40 46 48 50 55 57 60 64 68 69 71 7 did not sufficiently describe the participants,1 15 29 31 35 48 58 9 had coverage bias,6 14 40 48 54 57 62 64 65 8 did not have an appropriate statistical analysis15 20 28 34 35 64 67 68 and 30 had a low response rate1 5 14–16 20 22 28 31 32 34–36 43 45 47 49 52 56 57 59–62 65–67 69 70 72 (online supplemental figure S2). Among the 10 before–after trials, 1 did not have prespecified inclusion criteria44; 5 had low sample sizes or did not justify their sample size23 24 37 42 44; 3 did not have clearly defined, prespecified, consistently measured outcomes21 24 44; 9 did not blind participants3 23 24 26 37 39 42 44 53; 5 did not account for loss to follow-up in their analysis23 26 42 44 53 and 6 lacked statistical tests to assess for significant pre-intervention to post-intervention changes24 26 39 42 44 53 (online supplemental figure S3).

bmjopen-2020-043256supp003.pdf (7.9MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043256supp004.pdf (3.6MB, pdf)

Discussion

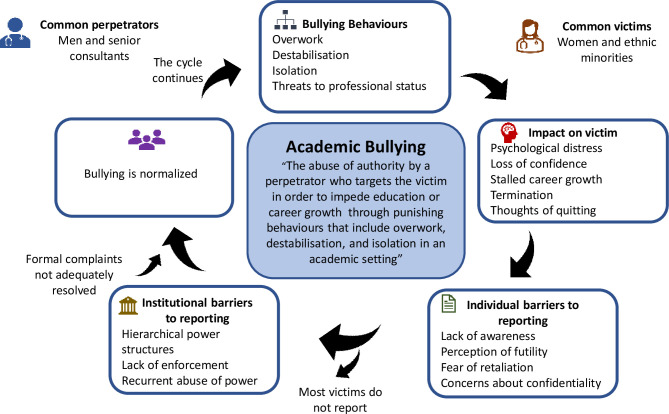

In this systematic review, we established a definition for academic bullying, identified common patterns of bullying and reported the impact on victims. We defined academic bullying as the abuse of authority by a perpetrator who targets the victim in order to impede their education or career through punishing behaviours that include overwork, destabilisation and isolation in an academic setting. Victims reported that academic bullying often resulted in stalled career advancement and thoughts of leaving the position. A majority of academic bullies were senior men, and a majority of victims were women. Barriers to reporting academic bullying included fear of reprisal, perceived hopelessness and institutional non-enforcement of anti-bullying policies. Strategies to overcome academic bullying, such as anti-bullying committees and adding professionalism as a requirement for career advancement, were associated with an improvement in the prevalence of bullying and resolution of formal reports (figure 2). Our review differs from other systematic reviews of bullying in medicine in its scope and population studied. We included studies involving all medical and surgical disciplines, but limited our analysis to physicians and physician trainees. While prior reviews have focused on the prevalence of bullying76 or anti-bullying interventions,77 our comprehensive review expanded the focus to also include characteristics of bullies and victims, impact and outcomes of bullying, anti-bullying strategies and facilitators of academic bullying.

Figure 2.

The definition, manifestations, impact, victims and perpetrators of academic bullying. Academic bullying is defined as an abuse of authority through punishing behaviours that include overwork, destabilisation and isolation. Victims are commonly women and ethnic minorities, while perpetrators are commonly men consultants. Individual and institutional factors contribute to the ongoing cycle of bullying.

Several factors contribute to the prevalence of bullying within academia. The hierarchical structure lends itself to power imbalances and prevents victims from speaking out, especially when the aggressor is tenured.78 The relative isolation of departments within universities allows poor behaviour to go unchecked. Furthermore, the closed networks within departments lend themselves to mobbing behaviour and cause victims to fear of being blacklisted for speaking out.79

A lack of clarity around the definition can limit awareness and reporting.50 The Graduation Questionnaire administered to all American medical students found that in years where respondents were asked if they had been bullied, the estimated prevalence was lower than when they were asked about specific bullying behaviours.15 Surveys on bullying should include a list of defining behaviours to increase clarity and accuracy in responses.80 Even in institutions with established reporting systems, respondents were often unaware of how to file a report.47 We found that victims of academic bullying rarely filed reports, primarily due to fear of retaliation. Reporting was not consistently effective and was more likely to worsen bullying.

We found that consultants were the most common perpetrators of bullying at all levels of training. Residents often bullied medical students. No studies assessed the relative contribution of fellows and senior residents to resident bullying. Among studies that analysed bullying among consultants by seniority, senior consultants were a commonly reported source of bullying.6 8 40 43 73 Women and ethnic minorities reported higher rates of bullying among demographic groups surveyed, although race and ethnicity were infrequently assessed in the surveys included in this study. While some argue that the increasing proportion of women trainees81 82 may change dynamics in healthcare settings, the leaky academic pipeline in which women remain under-represented in several academic specialties and in positions of leadership makes them vulnerable to the power asymmetries in academic medicine.83

Our review illustrates the self-reported harms of academic bullying. Victims experienced depressive symptoms, self-perceived loss of clinical ability and termination of employment. Academic bullying has been linked to depression,51 substance abuse,84 and hospitalisation for coronary artery or cerebrovascular disease.85 Bullying costs the NHS of the UK £325 million annually due to reduced performance and increased staff turnover.86 Disruptive behaviour, linked to bullying in the perioperative setting, has been linked to 27% of patient deaths, 67% of adverse events and 71% of medical errors.7 Reasons for consultant error include intimidation leading to a fear of communicating sources of harm and slow response times.87 We found that academic bullying negatively impacted patient safety. In a study of emergency medicine residents, 90% reported examples in which disruptive behaviour affected patient care, and 51% were less likely to call an abusive consultant.18

Interventions reported as effective were organisation level. Anti-bullying committees involving staff and learners can research bullying within their institution and address the most common disruptive behaviours through targeted interventions.67 An organisation-level, rather than individual-level approach, may address the root causes of academic bullying as well as the organisational culture that facilitates ongoing bullying. We found that anti-bullying committees typically included three elements: (1) a multidisciplinary team that includes clinicians and other front-line staff; (2) development of anti-bullying policies and a reporting process; and (3) an education campaign to promote awareness of policies. Owing to their multifaceted nature, it is challenging to evaluate the relative contributions of their components. Without well-designed trials, the effects of anti-bullying interventions are unknown. All of the intervention studies used before–after designs, which did not account for confounding variables, co-interventions, and background changes in policy or practice; the majority were at high risk of bias. Furthermore, among studies that implemented anti-bullying workshops, the majority interviewed participants immediately after the workshop without longitudinal follow-up to determine if benefits were sustained.

The need for a confidential reporting process was raised in the studies included in this review, but few described how confidentiality could be maintained when the report has to describe details of the bullying that may be only privy to the perpetrator and victim. The reporting process could take the form of the Office of Gender Equity at the University of California, where the accuser and the accused do not meet face to face; the discipline process is through an intermediary.39 A unique, non-punitive approach is the restorative justice approach used at Dalhousie University where victims, offenders, and administrators work collaboratively to address sexual harassment and reintegrate offenders.88 Reporting may have been ineffective in this review due to the impunity offered to prominent consultants. Senior personnel, particularly those who are well-known and successful in grant funding, are often considered ‘untouchable’, beyond reproach by their institutions.89 Behaviour is often learnt and modelling positive behaviours may break the cycle of bullying in medicine.90 One approach would be making professionalism a requirement for promotion and career advancement, as in the Department of Medicine at the University of Toronto in Canada91 or the University of Colorado School of Medicine.26

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this review include its broad scope, capturing several aspects of academic bullying, and its size (n=68 studies, 82 349 consultants and trainees). The cohort included was diverse, comprising several specialties and countries. We explicitly defined eligibility criteria and extracted data in duplicate. We used established tools to assess the risk of bias.

There are several limitations that should be acknowledged. There is no validated definition of academic bullying, and the included studies varied in their description of bullying. Most studies used questionnaires that were not previously validated. The survey instruments across studies differed from each other, and their results had to be pooled according to themes. We could not account for differences in institutional culture and hospital systems in the responses of survey participants. Estimates of the prevalence of bullying must be interpreted in light of the self-reported nature of bullying surveys. Data on bully/victim demographics were under-represented. Selection bias was a significant concern: 14 studies used convenience sampling, and 2 included voluntary focus groups for victims of bullying. Overall, the response rate was 59.2%, with a range of 12%–100%. Surrogate outcomes such as awareness of bullying were used, and the reporting of outcomes was inconsistent. As such, the effect of anti-bullying interventions must be interpreted cautiously.

Future directions

Significant gaps exist in the quality of the academic bullying literature, particularly with inconsistent definitions and limitations in study methodology. Our definition may be used to provide the breadth and granularity required to sufficiently capture cases of academic bullying in medicine. Studies on the impact of academic bullying would benefit from standardised, validated survey instruments. Although randomisation and blinding are not always possible to test the effect of interventions, a control group should be included in anti-bullying intervention studies.

Conclusions

Academic bullying refers to specific behaviours that disrupt the learning or career of the intended target and commonly consists of exclusion and overwork. The consequences include significant psychiatric distress and loss of career opportunities. Bullies tend to be men and senior consultants, whereas victims tend to be women. The fear of reprisal and non-enforcement of anti-bullying policies are the greatest barriers to addressing academic bullying. Results of bullying interventions must be interpreted with caution due to their methodological quality and reliance on surrogate measures. There is a need for well-designed trials with transparent reporting of relevant outcomes and accounting for temporal trends.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: TA contributed to study design, informed the search strategy, extracted and synthesised study data, and drafted and edited the manuscript. YE informed the search strategy, extracted and synthesised study data, and edited the manuscript. HGCVS conceived the study idea, informed the search strategy, analysed the data, drafted and edited the manuscript, and supervised the conduct of the study. HGCVS affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Funding: HGCVS receives support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Heart and Stroke Foundation, the Women As One Escalator Award and McMaster Department of Medicine.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplemental information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.Scott J, Blanshard C, Child S. Workplace bullying of junior doctors: cross-sectional questionnaire survey. N Z Med J 2008;121:10–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis D. Workplace bullying. Body Qual Res 2019;42:91–106. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fried JM, Vermillion M, Parker NH, et al. Eradicating medical student mistreatment: a longitudinal study of one institution's efforts. Acad Med 2012;87:1191–8. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182625408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oku AO, Owoaje ET, Oku OO, et al. Mistreatment among undergraduate medical trainees: a case study of a Nigerian medical school. Niger J Clin Pract 2014;17:678–82. 10.4103/1119-3077.144377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kulaylat AN, Qin D, Sun SX, et al. Perceptions of mistreatment among trainees vary at different stages of clinical training. BMC Med Educ 2017;17:1–6. 10.1186/s12909-016-0853-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malinauskiene V, Bernotaite L, Leisyte P. Bullying behavior and mental health. Med Pr 2017;68:307–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lavelle-Jones M. Bullying and Undermining Campaign – Let’s Remove it, 2017The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. Available: https://www.rcsed.ac.uk/news-public-affairs/news/2017/june/bullying-and-undermining-campaign-let-s-remove-it [Accessed 03 Mar 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quine L. Workplace bullying in NHS community trust: staff questionnaire survey. BMJ 1999;318:228–32. 10.1136/bmj.318.7178.228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okechukwu CA, Souza K, Davis KD, et al. Discrimination, harassment, abuse, and bullying in the workplace: contribution of workplace injustice to occupational health disparities. Am J Ind Med 2014;57:573–86. 10.1002/ajim.22221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKay R, Arnold DH, Fratzl J, et al. Workplace bullying in academia: a Canadian study. Employ Respons Rights J 2008;20:77–100. 10.1007/s10672-008-9073-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute . Quality assessment tool for before-after (pre-post) studies with no control group. Available: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

- 12.Joanna Briggs Institute . Checklist for prevalence studies. Available: http://joannabriggs.org/research/critical-appraisal-tools.html

- 13.Oser TK, Haidet P, Lewis PR, et al. Frequency and negative impact of medical student mistreatment based on specialty choice: a longitudinal study. Acad Med 2014;89:755–61. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chadaga AR, Villines D, Krikorian A. Bullying in the American graduate medical education system: a national cross-sectional survey. PLoS One 2016;11:e0150246. 10.1371/journal.pone.0150246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mavis B, Sousa A, Lipscomb W, et al. Learning about medical student mistreatment from responses to the medical school graduation questionnaire. Acad Med 2014;89:705–11. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stasenko M, Tarney C, Seier K, et al. Sexual harassment and gender discrimination in gynecologic oncology. Gynecol Oncol 2020;159:317–21. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kemper KJ, Schwartz A, Pediatric Resident Burnout-Resilience Study Consortium . Bullying, discrimination, sexual harassment, and physical violence: common and associated with burnout in pediatric residents. Acad Pediatr 2020;20:991–7. 10.1016/j.acap.2020.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huber M, Lopez J, Messman A, et al. Emergency medicine resident perception of abuse by consultants: results of a national survey. Ann Emerg Med 2020;76:814–5. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.06.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raj A, Freund KM, McDonald JM, et al. Effects of sexual harassment on advancement of women in academic medicine: a multi-institutional longitudinal study. EClinicalMedicine 2020;20:100298. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D'Agostino JP, Vakharia KT, Bawa S, et al. Intimidation and sexual harassment during plastic surgery training in the United States. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2019;7:e2493. 10.1097/GOX.0000000000002493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kappy MD, Holman E, Kempner S, et al. Identifying medical student mistreatment in the obstetrics and gynecology clerkship. J Surg Educ 2019;76:1516–25. 10.1016/j.jsurg.2019.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammoud MM, Appelbaum NP, Wallach PM, et al. Incidence of resident mistreatment in the learning environment across three institutions. Med Teach 2021;43:334–40. 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1845306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castillo-Angeles M, Calvillo-Ortiz R, Acosta D, et al. Mistreatment and the learning environment: a mixed methods approach to assess knowledge and raise awareness amongst residents. J Surg Educ 2019;76:305–14. 10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.House JB, Griffith MC, Kappy MD, et al. Tracking student mistreatment data to improve the emergency medicine clerkship learning environment. West J Emerg Med 2018;19:18–22 https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9md5263b 10.5811/westjem.2017.11.36718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zurayk LF, Cheng KL, Zemplenyi M, et al. Perceptions of sexual harassment in oral and maxillofacial surgery training and practice. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2019;77:2377–85. 10.1016/j.joms.2019.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lind KT, Osborne CM, Badesch B, et al. Ending student mistreatment: early successes and continuing challenges. Med Educ Online 2020;25:1690846. 10.1080/10872981.2019.1690846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu Y-Y, Ellis RJ, Hewitt DB, et al. Discrimination, abuse, harassment, and burnout in surgical residency training. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1741–52. 10.1056/NEJMsa1903759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balch Samora J, Van Heest A, Weber K, et al. Harassment, discrimination, and bullying in orthopaedics: a work environment and culture survey. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2020;28:e1097–104. 10.5435/JAAOS-D-19-00822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang LM, Ellis RJ, Ma M, Prevalence MM, et al. Prevalence, types, and sources of bullying reported by US general surgery residents in 2019. JAMA 2020;323:2093–5. 10.1001/jama.2020.2901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ayyala MS, Rios R, Wright SM. Perceived bullying among internal medicine residents. JAMA 2019;322:576–8. 10.1001/jama.2019.8616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chowdhury ML, Husainat MM, Suson KD. Workplace bullying of urology residents: implications for the patient and provider. Urology 2019;127:30–5. 10.1016/j.urology.2018.11.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolfman DJ, Parikh JR. Resident bullying in diagnostic radiology. Clin Imaging 2019;55:47–52. 10.1016/j.clinimag.2019.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chung MP, Thang CK, Vermillion M, et al. Exploring medical students’ barriers to reporting mistreatment during clerkships: a qualitative study. Med Educ Online 2018;23:1478170. 10.1080/10872981.2018.1478170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kemp MT, Smith M, Kizy S, et al. Reported mistreatment during the surgery clerkship varies by student career choice. J Surg Educ 2018;75:918–23. 10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wear D, Aultman J. Sexual harassment in academic medicine: persistence, Non-Reporting, and institutional response. Med Educ Online 2005;10:4377–11. 10.3402/meo.v10i.4377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rouse LP, Gallagher-Garza S, Gebhard RE, et al. Workplace bullying among family physicians: a gender focused study. J Womens Health 2016;25:882–8. 10.1089/jwh.2015.5577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kulaylat AN, Qin D, Sun SX, et al. Aligning perceptions of mistreatment among incoming medical trainees. J Surg Res 2017;208:151–7. 10.1016/j.jss.2016.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Jones R, et al. Sexual harassment and discrimination experiences of academic medical faculty. JAMA 2016;315:2120–1. 10.1001/jama.2016.2188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Best CL, Smith DW, Raymond JR, et al. Preventing and responding to complaints of sexual harassment in an academic health center: a 10-year review from the medical University of South Carolina. Acad Med 2010;85:721–7. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d27fd0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shrier DK, Zucker AN, Mercurio AE, et al. Generation to generation: discrimination and harassment experiences of physician mothers and their physician daughters. J Womens Health 2007;16:883–94. 10.1089/jwh.2006.0127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carr PL, Ash AS, Friedman RH, et al. Faculty perceptions of gender discrimination and sexual harassment in academic medicine. Ann Intern Med 2000;132:889–96. 10.7326/0003-4819-132-11-200006060-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Benmore G, Henderson S, Mountfield J, et al. The Stopit! programme to reduce bullying and undermining behaviour in hospitals. J Health Organ Manag 2018;32:428–43. 10.1108/JHOM-02-2018-0047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shabazz T, Parry-Smith W, Oates S, et al. Consultants as victims of bullying and undermining: a survey of Royal College of obstetricians and gynaecologists consultant experiences. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011462. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cresswell K, Sivashanmugarajan V, Lodhi W, et al. Bullying workshops for obstetric trainees: a way forward. Clin Teach 2015;12:83–7. 10.1111/tct.12261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheema S, Ahmad K, Giri SK, et al. Bullying of junior doctors prevails in Irish health system: a bitter reality. Ir Med J 2005;98:12–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duru P, Ocaktan ME, Çelen Ümit, et al. The effect of workplace bullying perception on psychological symptoms: a structural equation approach. Saf Health Work 2018;9:210–5. 10.1016/j.shaw.2017.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chambers CNL, Frampton CMA, McKee M, et al. ‘It feels like being trapped in an abusive relationship’: bullying prevalence and consequences in the New Zealand senior medical workforce: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020158. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Al-Shafaee M, Al-Kaabi Y, Al-Farsi Y, et al. Pilot study on the prevalence of abuse and mistreatment during clinical internship: a cross-sectional study among first year residents in Oman. BMJ Open 2013;3:1–7. 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ling M, Young CJ, Shepherd HL, et al. Workplace bullying in surgery. World J Surg 2016;40:2560–6. 10.1007/s00268-016-3642-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ahmadipour H, Vafadar R. Why mistreatment of medical students is not reported in clinical settings: perspectives of trainees. Indian J Med Ethics 2016;1:215–8. 10.20529/IJME.2016.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Loerbroks A, Weigl M, Li J, et al. Workplace bullying and depressive symptoms: a prospective study among junior physicians in Germany. J Psychosom Res 2015;78:168–72. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Owoaje ET, Uchendu OC, Ige OK. Experiences of mistreatment among medical students in a university in South West Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract 2012;15:214–9. 10.4103/1119-3077.97321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meloni M, Austin M. Implementation and outcomes of a zero tolerance of bullying and harassment program. Aust Health Rev 2011;35:92–4. 10.1071/AH10896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Imran N, Jawaid M, Haider II, et al. Bullying of junior doctors in Pakistan: a cross-sectional survey. Singapore Med J 2010;51:592–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ogunsemi OO, Alebiosu OC, Shorunmu OT. A survey of perceived stress, intimidation, harassment and well-being of resident doctors in a Nigerian teaching hospital. Niger J Clin Pract 2010;13:183–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nagata-Kobayashi S, Maeno T, Yoshizu M, et al. Universal problems during residency: abuse and harassment. Med Educ 2009;43:628–36. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03388.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rautio A, Sunnari V, Nuutinen M, et al. Mistreatment of university students most common during medical studies. BMC Med Educ 2005;5:1–12. 10.1186/1472-6920-5-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kapoor S, Ajinkya S, Jadhav PR. Bullying and Victimization Trends in Undergraduate Medical Students - A Self-Reported Cross-Sectional Observational Survey. J Clin Diagn Res 2016;10:VC05–8. 10.7860/JCDR/2016/16905.7323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peres MFT, Babler F, Arakaki JNL, et al. Mistreatment in an academic setting and medical students' perceptions about their course in São Paulo, Brazil: a cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med J 2016;134:130–7. 10.1590/1516-3180.2015.01332210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gan R, Snell L. When the learning environment is suboptimal: exploring medical students' perceptions of "mistreatment". Acad Med 2014;89:608–17. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dikmetaş E, Top M, Ergin G. An examination of mobbing and burnout of residents. Turk Psikiyatri Derg 2011;22:137–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Llewellyn A, Karageorge A, Nash L. Bullying and sexual harassment of junior doctors in New South Wales, Australia: rate and reporting outcomes. Aust Heal Rev 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Elghazally NM, Atallah AO. Bullying among undergraduate medical students at Tanta University, Egypt: a cross-sectional study. Libyan J Med 2020;15:1816045. 10.1080/19932820.2020.1816045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Colenbrander L, Causer L, Haire B. ‘If you can’t make it, you’re not tough enough to do medicine’: a qualitative study of Sydney-based medical students’ experiences of bullying and harassment in clinical settings. BMC Med Educ 2020;20:1–12. 10.1186/s12909-020-02001-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brown A, Bonneville G, Glaze S, Nevertheless GS. Nevertheless, they persisted: how women experience gender-based discrimination during postgraduate surgical training. J Surg Educ 2021;78:17–34. 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.06.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Askew DA, Schluter PJ, Dick M-L, et al. Bullying in the Australian medical workforce: cross-sectional data from an Australian e-Cohort study. Aust Health Rev 2012;36:197–204. 10.1071/AH11048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eriksen GS, Nygreen I, Rudmin FW. Bullying among hospital staff: use of psychometric triage to identify intervention priorities. E-Journal of Applied Psychology 2011;7:26–31. 10.7790/ejap.v7i2.252 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Iqbal A, Khattak A, Malik FR. Bullying behaviour in operating theatres. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 2020;32:352-355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]