Abstract

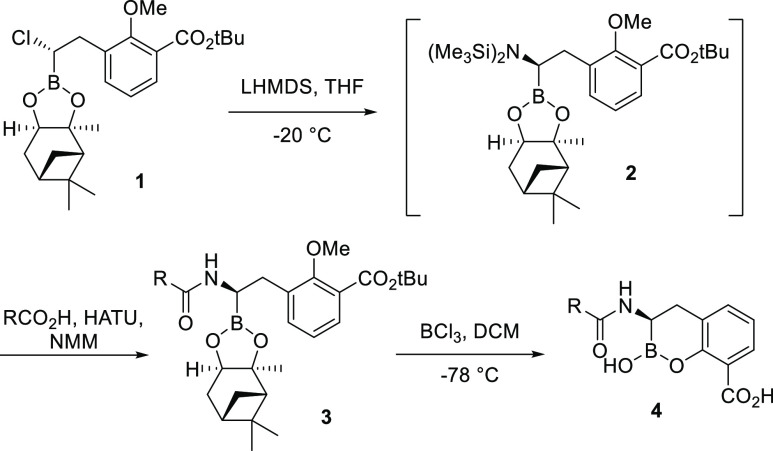

A major antimicrobial resistance mechanism in Gram-negative bacteria is the production of β-lactamase enzymes. The increasing emergence of β-lactamase-producing multi-drug-resistant “superbugs” has resulted in increases in costly hospital Emergency Department (ED) visits and hospitalizations due to the requirement for parenteral antibiotic therapy for infections caused by these difficult-to-treat bacteria. To address the lack of outpatient treatment, we initiated an iterative program combining medicinal chemistry, biochemical testing, microbiological profiling, and evaluation of oral pharmacokinetics. Lead optimization focusing on multiple smaller, more lipophilic active compounds, followed by an exploration of oral bioavailability of a variety of their respective prodrugs, provided 36 (VNRX-7145/VNRX-5236 etzadroxil), the prodrug of the boronic acid-containing β-lactamase inhibitor 5 (VNRX-5236). In vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated that 5 restored the activity of the oral cephalosporin antibiotic ceftibuten against Enterobacterales expressing Ambler class A extended-spectrum β-lactamases, class A carbapenemases, class C cephalosporinases, and class D oxacillinases.

Introduction

β-Lactams are the most widely used class of antibiotics in both the community and hospital setting, representing over 60% of the total world antibiotic market.1 This preferred, safe, and efficacious class of antibiotics is under constant threat by expansion of multi-drug-resistant (MDR) Gram-negative bacteria including increasing hospital and community prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales2 (CRE) and extended spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacterales.3,4 Similarly, the rates of co-resistance to other classes of antibacterial agents including trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and fluoroquinolones are higher than recommendations for use (2010 IDSA Uncomplicated UTI and Pyelonephritis clinical guidelines) for most of the US and, in many areas, are increasing steadily.5−7 This growing prevalence of MDR bacteria in the community has led to an increase in costly emergency department visits and hospitalizations required to manage resistant infections by administration of intravenous (IV) or intramuscular antibiotic therapy, including carbapenems. As a result, additional economic and resource burdens are placed on healthcare systems and patient care while potentially increasing selective pressure for resistance growth,8 including CRE, and subsequent transmission to other hospitalized patients.9 To avoid unnecessary institutional escalations for the treatment of community-associated infections, such as complicated urinary tract infections (cUTI) and acute pyelonephritis, new oral treatment options are urgently needed. An effective oral therapeutic could also benefit hospitalized patients who are ready for discharge before completing a full course of IV antibacterial therapy if an effective IV to oral step-down therapy is available. This has the potential to significantly reduce hospital stay length, decrease hospital-related costs, and allow the patient to regain a normal quality of life sooner.

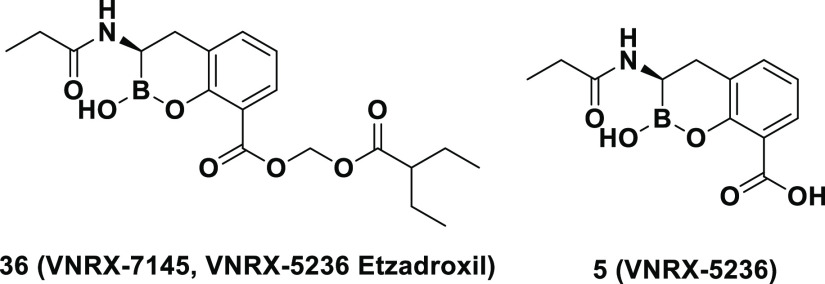

Currently, there are no approved orally bioavailable β-lactams or β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor (BL/BLI) combinations that cover Enterobacterales expressing key class A or D carbapenemases or class C cephalosporinases. Resistance and co-resistance to fluoroquinolones and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole among ESBL- and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales further limit oral treatment options.10 The only approved oral BL/BLI is amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, which demonstrates limited activity against Gram-negative organisms expressing Ambler class A ESBLs and lacks activity against class A carbapenemases, class C cephalosporinases, and class D oxacillinases. An investigational oral carbapenem (tebipenem pivoxil hydrobromide)11 and an investigational oral thiopenem (sulopenem etzadroxil, administered with probenecid)12 are under development for UTIs due to ESBL-producing Enterobacterales; however, their spectrum of activity does not include carbapenem-resistant organisms.13 Recent studies have shown that boron-based covalent and slowly reversible inhibitors, such as vaborbactam (RPX7009),14 taniborbactam (formerly VNRX-5133),15,16 and QPX772817 (Figure 1), efficiently inhibit class A and C (vaborbactam) and class A, B, C, and D enzymes (taniborbactam and QPX7728). However, the early work on boronic acid-based BLIs by academic groups18−22 and the pharmaceutical industry focused on IV products.14−17,23−25 Recognizing the lack of effective oral agents against the increasingly resistant pathogens described above, our efforts focused on the development of an orally bioavailable boronic acid-based β-lactamase inhibitor capable of restoring antibacterial activity of the third-generation oral cephalosporin ceftibuten. We present herein the lead optimization, structure–activity relationship (SAR), microbiological profiling, and prodrug pharmacokinetics (PK) that led to the discovery of VNRX-7145 (VNRX-5236 etzadroxil).26,27 This broad-spectrum BLI is currently in Phase 1 clinical studies (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04243863).

Figure 1.

Boronic acid-based BLIs approved (vaborbactam), in Phase 3 development (taniborbactam), and in Phase 1 development (QPX7728).

Results and Discussion

Design of BLIs to Protect Oral Cephalosporins against Serine-β-Lactamases

Identification of an oral cephalosporin partner was key in the development of an orally bioavailable BLI. For cUTI and uUTI, approved oral cephalosporin candidates, such as cefpodoxime proxetil and ceftibuten, were once reliable treatments, but their effectiveness has been eroded by the spread of β-lactamase-mediated resistance in Gram-negative organisms. Comparative susceptibilities of clinical isolates producing extended spectrum β-lactamases to ceftibuten relative to other oral β-lactams indicate that ceftibuten is far less susceptible to hydrolysis by ESBLs, while maintaining significant affinity to penicillin binding proteins to provide intrinsic potency.28−30 These features facilitate restoration of antibacterial activity of the β-lactam by a BLI, and combined with its high absorption and favorable PK profile, ceftibuten is the optimal choice for combination with an oral BLI.31

Utilizing the structure-based design work by Ness et al.(32) and the extensive SAR studies and microbiological profiling by Burns et al.(25) and Liu et al.,15 the authors determined that the need to balance the attributes that allow for Gram-negative bacterial penetration with the attributes necessary for oral absorption was the key hurdle to overcome. To protect β-lactam activity against the targeted clinically relevant β-lactamase-producing bacteria, the partner BLI must cross the outer membrane of diverse Gram-negative pathogens. O’Shea and Moser33 observed that high-molecular-weight compounds with clog P < 1 and a topological polar surface area (tPSA) > 150 A2 have preferred access into Gram-negative bacteria. However, it has been well established that lower-molecular-weight compounds with higher clog P and tPSA < 140 A2 have an increased oral absorption.34,35

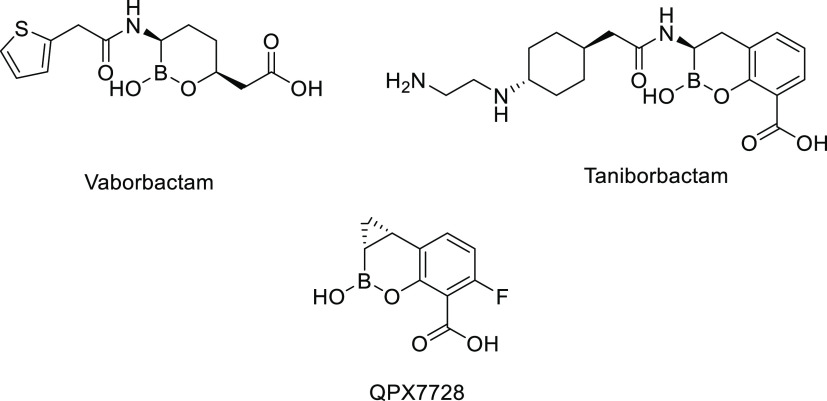

Keeping these conflicting attributes in mind, our design strategy was to maintain the cyclic boronate scaffold that interacts covalently with the active-site serine residue with the plan to create a prodrug of the carboxylic acid group to increase lipophilicity and aid oral absorption (Figure 2). The amide side of the molecule would focus on small lipophilic groups that maintained BLI activity but limited the molecular weight and the tPSA.

Figure 2.

Strategy for designing a cyclic boronate-based BLI with potential for oral absorption.

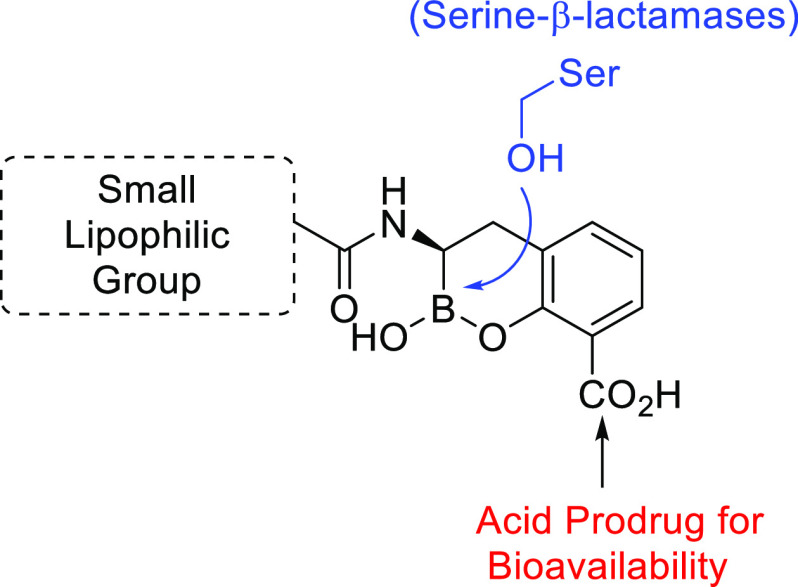

Synthesis of the Cyclic Boronate-Based BLIs

The cyclic boronate-based BLIs were prepared using modifications of previously reported procedures (Scheme 1).15,25 Compound 1, isolated from two consecutive homologation reactions following Matteson’s protocol,36 was treated with lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide at −20 °C to afford the desired stereoisomer intermediate 2. The α-silylaminoboronate intermediate was treated in situ with HATU and N-methylmorpholine and coupled with the desired carboxylic acid. The carboxylic acids (RCO2H) used for the SAR studies were either commercially available or readily synthesized from available starting materials. The resultant amides 3 were deprotected and cyclized by treatment with BCl3 (1 M in DCM) at −78 °C to afford the crude boronates 4 which were purified by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and then lyophilized to dryness.

Scheme 1. Generalized Synthesis of Cyclic Boronate-Based BLIs.

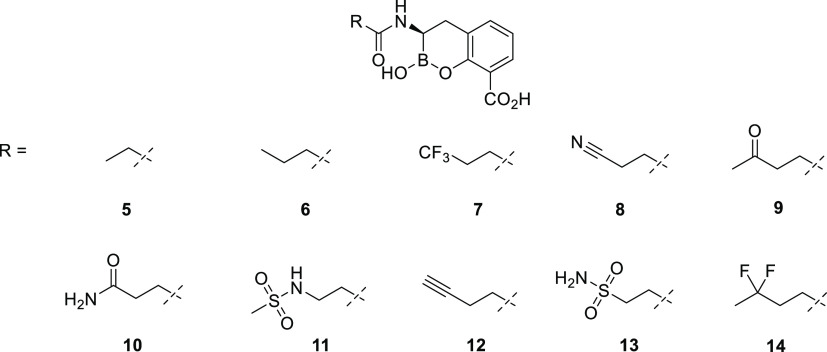

SAR: β-Lactamase Inhibitor

A set of cyclic boronates (Figure 3) was evaluated for both inhibition of purified β-lactamase enzymes and in vitro rescue of ceftibuten activity against selected ceftibuten-resistant Enterobacterales strains. Our primary in-house biochemical screening panel was composed of four β-lactamases belonging to Ambler class A (SHV-5, KPC-2), class C (AmpC), and class D (OXA-48). Antibacterial activity assays were performed using ceftibuten-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli isolates; the minimum concentration of each BLI necessary to restore the antibacterial activity of ceftibuten (fixed at 1 μg/mL) against clinical isolates of E. coli and K. pneumoniae expressing various β-lactamases, by enzyme category, was determined to rank-order the level of BLI potentiation of ceftibuten activity. This concentration of ceftibuten is clinically relevant as it corresponds to the EUCAST Susceptible breakpoint for treatment of infections originating in the urinary tract (EUCAST 2021).37

Figure 3.

Chemical structures of screened BLIs.

Keeping the emphasis on balancing the clog P and tPSA to maximize Gram-negative bacterial penetration with oral absorption of the prodrug, our efforts focused on small amide side chains with limited functionality and moderate-to-high lipophilicity. When evaluated against a primary panel of β-lactamases, all the analogues displayed similar potent inhibition of the class A SHV-5 ESBL and KPC-2 carbapenemase and the class C AmpC cephalosporinase (Table 1). Potency against the class D OXA-48 carbapenemase was more varied, with IC50’s ranging from 0.32 to 8.55 μM. The BLIs generally exhibited comparable potency (≤8-fold variation across BLIs, by strain) in rescuing ceftibuten fixed at 1 μg/mL against individual representative ceftibuten-resistant strains of K. pneumoniae and E. coli expressing ESBL, KPC, class C, and OXA-48 β-lactamases, with certain exceptions (Table 2). Some increased variation in potency among the BLIs against strains expressing class C and OXA-48 β-lactamases was observed. In particular, compounds 7, 12, and 14 exhibited reduced activity that could be attributed to their higher clog P and lower tPSA values. The remaining BLIs possessed the requisite biochemical and microbiological activity to be progressed to the next stage of SAR development.

Table 1. Biochemical Activity of BLIs 5–14 against Purified β-Lactamasesa.

| IC50 (μM) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | clog P | tPSA | SHV-5 (class A) | KPC-2 (class A) | AmpC (class C) | OXA-48 (class D) |

| 5 | 0.48 | 96 | 0.126 | 0.080 | 0.014 | 0.317 |

| 6 | 1.01 | 96 | 0.036 | 0.093 | 0.009 | 0.426 |

| 7 | 0.72 | 96 | 0.008 | 0.043 | 0.009 | 1.62 |

| 8 | 0.07 | 120 | 0.012 | 0.033 | 0.014 | 0.687 |

| 9 | 0.23 | 113 | 0.025 | 0.116 | 0.008 | 1.45 |

| 10 | –0.64 | 139 | 0.514 | 0.069 | 0.006 | 1.79 |

| 11 | –0.26 | 142 | 0.012 | 0.028 | 0.005 | 4.67 |

| 12 | 0.53 | 96 | 0.017 | 0.031 | 0.006 | 0.627 |

| 13 | –0.92 | 156 | 0.008 | 0.035 | 0.003 | 8.55 |

| 14 | 0.68 | 96 | 0.006 | 0.041 | 0.007 | 2.39 |

IC50 values reported as the mean from duplicate measurements on separate days with automatic repeat if data differed by more than 20% from the previous result.

Table 2. Concentrations of BLIs 5–14 to Restore the Antibacterial Activity of Ceftibuten (Fixed at 1 μg/mL) against β-Lactamase-Producing Isolates of E. coli and K. pneumoniaea.

| BLI concentration (μg/mL)b |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESBL |

KPC |

Class C |

OXA-48 |

|||||

| entry | E. coli ESBL 5 (CTX-M-15, TEM-1) | K. pneumoniae ESBL 10 (SHV-12, TEM-1) | E. coli 786978 (KPC) | K. pneumoniae 156309 (SHV-11, TEM-1, KPC-2) | E. coli J53 (SHV-5, AmpC, TEM-1) | K. pneumoniae 196477 (AmpC, CMY-2, TEM-1, CTX-M-15) | E. coli 664507 (OXA-48) | K. pneumoniae SI-C17 (OXA-48) |

| CTBc | 128 | 32 | 8 | 256 | 256 | 4 | 128 | 256 |

| 5 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.03 | 0.016 | 0.03 | 1 |

| 6 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.016 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 1 |

| 7 | 1 | 0.06 | 1 | 2 | 0.03 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 8 |

| 8 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 2 |

| 9 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 1 | 2 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 4 |

| 10 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0.016 | 0.06 | 0.5 |

| 11 | 0.12 | 0.016 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.016 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 2 |

| 12 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 4 |

| 13 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 1 | 2 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 2 |

| 14 | 0.5 | 0.03 | 1 | 4 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 4 |

Abbreviations: ESBL = extended-spectrum β-lactamase; K. pneumoniae = Klebsiella pneumoniae; E. coli = Escherichia coli; CTB = ceftibuten.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of BLIs titrated with ceftibuten fixed at 1 μg/mL.

MIC of ceftibuten titrated alone.

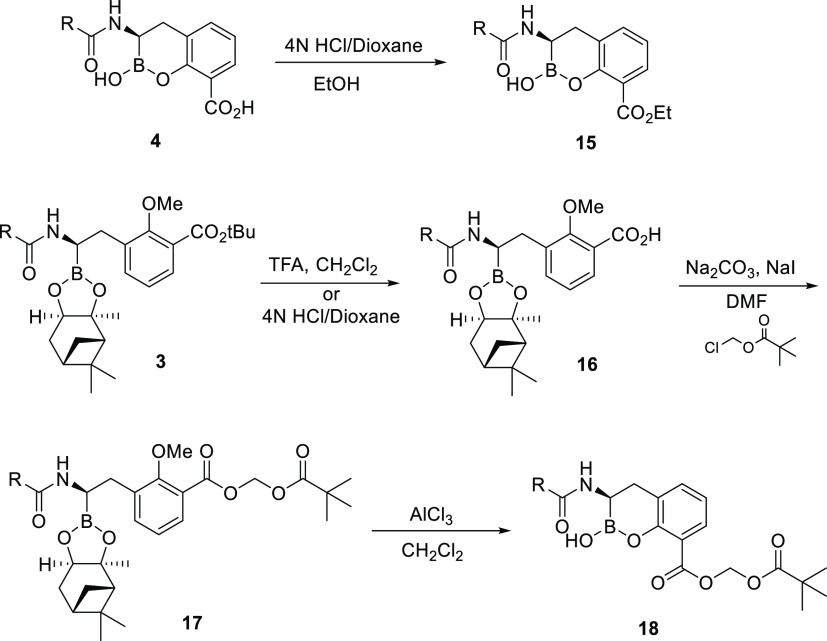

Synthesis of the Cyclic Boronate-Based BLI Prodrugs

With the focus of the program on discovering an orally bioavailable BLI, comparison of prodrugs of the active BLIs was initiated to differentiate between BLIs with similar biochemical and antibacterial activity. A pair of carboxylic acid ester prodrugs of each BLI were prepared. Two types of ester prodrugs were utilized: alkyl ester (ethyl) and acyloxy ester (pivoxyl). Ethyl esters 15 were synthesized from the carboxylic acids by addition of 4 N HCl in dioxane in the presence of ethanol (Scheme 2). For pivoxyl esters 18, intermediate 3 was treated with trifluoroacetic acid in dichloromethane (DCM) or 4 N HCl in dioxane to provide acid 16. Reaction of 16 with sodium carbonate, sodium iodide, and chloromethyl pivalate in N,N-dimethylformamide afforded ester 17. The pinanediol and methyl ether were selectively removed by treatment with aluminum chloride in DCM to provide the desired pivoxyl esters 18 (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. Generalized Synthesis of Cyclic Boronate-Based BLI Ethyl and Pivoxyl Prodrugs.

Oral Bioavailability of β-Lactamase Inhibitors

Ethyl and pivoxyl prodrugs of the remaining BLIs were prepared and dosed via oral gavage to rats. The oral bioavailability data demonstrated a clear effect of clog P and tPSA on the oral absorption of the BLI prodrugs tested (Table 3). Prodrug analogues with clog P < 1.00 and/or tPSA > 120 exhibited poor bioavailability. The BLI analogues whose prodrugs demonstrated reasonable to good (F ∼ 20–99%) absorption included compounds 5, 6, 8, and 9. The pivoxyl prodrugs increased the clog P of the BLIs above 1.00, which appeared to maximize absorption when compared with the ethyl versions. One exception to this was the ethyl prodrug of 5 which had a higher clog P (1.23) but had lower bioavailability (F < 5%) due to lack of hydrolysis of the ethyl ester (F ∼ 20–30% of 19 was observed).

Table 3. Oral Bioavailability of BLI Esters in Rats.

| entry | ester | clog P | tPSA | dose (mg/kg) | F (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 19 (ethyl) | 1.23 | 85 | 3b | <5 |

| 20 (pivoxyl) | 1.54 | 111 | 10 | 99 | |

| 6 | 21 (ethyl) | 1.76 | 85 | NT | NT |

| 22 (pivoxyl) | 2.07 | 111 | 3b | 31 | |

| 8 | 23 (ethyl) | 0.69 | 109 | 5 | <5 |

| 24 (pivoxyl) | 1.00 | 135 | 10 | 20 | |

| 9 | 25 (ethyl) | 0.98 | 102 | 5 | <5 |

| 26 (pivoxyl) | 1.29 | 128 | 10 | 95 | |

| 10 | 27 (ethyl) | 0.12 | 128 | 3b | <5 |

| 28 (pivoxyl) | 0.43 | 154 | 3b | <5 | |

| 11 | 29 (ethyl) | 0.50 | 131 | NT | NT |

| 30 (pivoxyl) | 0.81 | 157 | 3b | <5 | |

| 13 | 31 (ethyl) | –0.16 | 145 | 3b | <5 |

| 32 (pivoxyl) | 0.15 | 171 | NT | NT |

F (%) = percent absolute oral bioavailability corrected for MW difference between the prodrug and parent.

Dosed as a cassette with another ester; NT—not tested.

Based on the high oral bioavailability data of pivoxyl prodrugs 20 and 26, studies were undertaken to select the most promising BLI. To further differentiate between BLIs 5 and 9, the compounds were tested against a challenge set of clinical isolates of E. coli and K. pneumoniae expressing ESBL (n = 5), KPC (n = 11), class C (n = 4), and OXA-48 (n = 5) β-lactamases. Against this set of 25 strains, with ceftibuten fixed at 1 μg/mL, 5 rescued ceftibuten with a minimum inhibitory concentration required to inhibit the growth of 90% of organisms tested (MIC90) = 1 μg/mL, while 9 had an MIC90 = 4 μg/mL (Table 4). As a result, 5 was selected as the active BLI to further evaluate and maximize its oral absorption.

Table 4. Concentration of BLIs 5 and 9 to Restore the Antibacterial Activity of Ceftibuten (Fixed at 1 μg/mL) against Clinical Isolates of E. coli and K. pneumoniae Expressing Various β-Lactamases by Enzyme Category.

| BLI concentration (μg/mL) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| category | strain | designation | β-lactamases | 5 | 9 |

| ESBL | E. coli | ESBL 5 | CTX-M-15, TEM-1 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| K. pneumoniae | ESBL 10 | SHV-12, TEM-1 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |

| E. coli | SI LP377 | CTX-M-2 | 0.004 | ≤0.002 | |

| E. coli | 3327 | TEM-1, SHV-12 | 0.03 | 0.016 | |

| K. pneumoniae | 304487 | SHV-12, TEM-1 | 0.016 | 0.016 | |

| KPC | K. pneumoniae | UMM | SHV-5, KPC-2, TEM-1 | ≤0.002 | ≤0.002 |

| E. coli | 233 | AmpC SHV-12, CTX-M-15, TEM-1 | 0.016 | 0.016 | |

| K. pneumoniae | 136928 | SHV-1, TEM-1, KPC-2 | 1 | 4 | |

| K. pneumoniae | 137052 | SHV-11, KPC-3, TEM-1 | 0.06 | 0.25 | |

| K. pneumoniae | 155140 | SHV-12, KPC-2, AmpC, TEM-1 | 0.25 | 0.5 | |

| K. pneumoniae | 156309 | SHV-11, TEM-1, KPC-2 | 0.5 | 2 | |

| K. pneumoniae | 166964 #1 | KPC-3, TEM-1, AmpC | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| E. coli | 786978 | KPC | 0.5 | 1 | |

| E. coli | 849121 | KPC | ≤0.002 | ≤0.002 | |

| K. pneumoniae | 845661 | KPC | 2 | 4 | |

| K. pneumoniae | 845670 | KPC | ≤0.002 | ≤0.002 | |

| class C | E. coli | J53 | SHV-5, AmpC, TEM-1 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| E. coli | SI-P026TC | CMY-2, TEM-1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| K. pneumoniae | 196477 | AmpC, CMY-2, TEM-1, CTX-M-15 | 0.016 | 0.06 | |

| K. pneumoniae | 217917 | CMY-2, TEM-1 | 0.12 | 0.12 | |

| OXA-48 | K. pneumoniae | DOV | OXA-48 | 0.016 | 0.06 |

| K. pneumoniae | SI-C05 | OXA-48 | 0.03 | 0.06 | |

| K. pneumoniae | SI-C17 | OXA-48 | 1 | 4 | |

| E. coli | 664507 | OXA-48 | 0.03 | 0.06 | |

| E. coli | 664520 | OXA-48 | 0.03 | 0.5 | |

| BLI concentration to rescue activity of ceftibuten (fixed at 1 μg/mL) against >90% of tested strains | 1 | 4 | |||

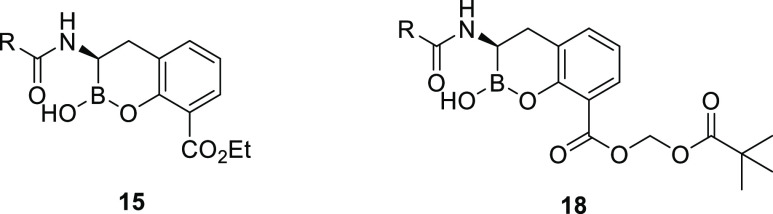

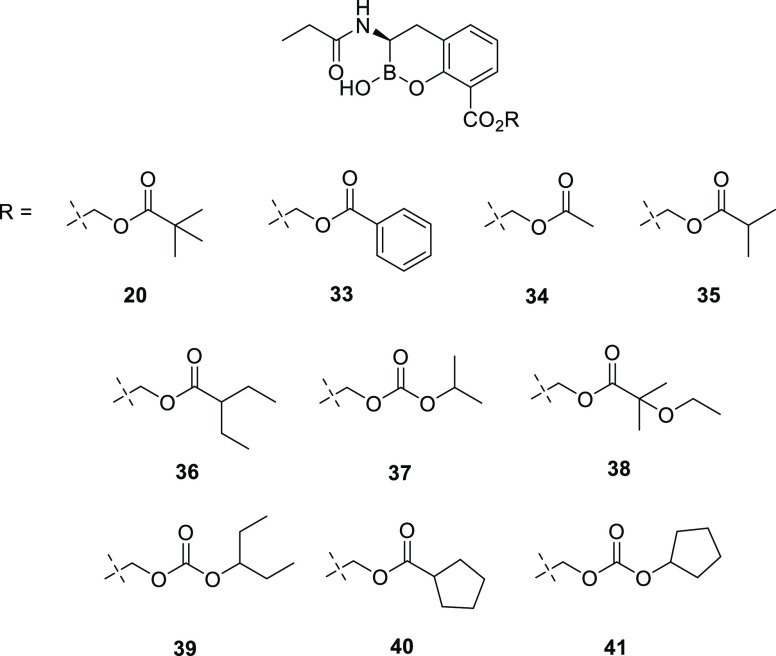

Optimization of Oral Bioavailability of Compound 5

A series of acyloxy and alkyl carbonate prodrugs were prepared following the synthesis presented in Scheme 2 (Figure 4). Following a similar protocol, all compounds were dosed via oral gavage in rats. The majority of prodrugs exhibited reasonable oral bioavailability (Table 5). Despite clog P values ranging from 1.09 to 2.15, the various alkyl carbonate prodrugs tested showed similar results with bioavailability (F) values from 23 to 33%. Among the acyloxy prodrugs tested, the pivoxyl- (20) and 3-pentylacyloxy- (36) prodrugs demonstrated the highest oral bioavailability and were tested in additional species.

Figure 4.

Chemical structures of compound 5 prodrugs.

Table 5. Oral Bioavailability of Compound 5 Prodrugs in Rats.

| entry | clog P | tPSA | dose (mg/kg) | F (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 1.54 | 111 | 10 | 99 |

| 33 | 2.19 | 111 | 5 | 29 |

| 34 | 0.31 | 111 | 10 | 10 |

| 35 | 1.14 | 111 | 10 | 38 |

| 36 | 2.20 | 111 | 5 | 82 |

| 37 | 1.09 | 120 | 10 | 23 |

| 38 | 1.09 | 120 | 10 | 28 |

| 39 | 2.15 | 120 | 10 | 33 |

| 40 | 1.78 | 111 | 10 | 19 |

| 41 | 1.72 | 120 | 10 | 24 |

F (%) = percent absolute oral bioavailability corrected for MW difference between the prodrug and parent.

Upon dosing the pivoxyl- (20) and 3-pentylacyloxy- (36) prodrugs in mice, dogs, and monkeys, 36 demonstrated the most consistent oral bioavailability across species (Table 6). While 20 exhibited excellent oral bioavailability in rats (F = 99%), bioavailability was considerably lower in the other three tested species. In addition, prodrugs that liberate pivalate (trimethylacetic acid) upon hydrolysis have resulted in the generation of pivaloylcarnitine which, upon elimination in the urine, leads to depletion of the limited carnitine pool in the body.38,39 While the potential toxicity resulting from carnitine depletion is dependent on the amount of pivalate dosed/generated, 36 does not have this liability and as a result, based on these data and its consistent and high oral bioavailability data across species, was selected as the candidate for further development.

Table 6. Oral Bioavailability of 20 and 36 across Species.

| rat |

mouse |

dog |

monkey |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | dose (mg/kg) | F (%)a | dose (mg/kg) | F (%)a | dose (mg/kg) | F (%)a | dose (mg/kg) | F (%)a |

| 20 | 10 | 99 | 5 | 42 | 10 | 42 | 10 | 52 |

| 36 | 5 | 82 | 10 | 72 | 5 | 62 | 5 | 61 |

F (%) = percent absolute oral bioavailability corrected for MW difference between the prodrug and parent.

Compound 36 Demonstrated Nearly Complete Hydrolysis to 5 in Various Matrixes across Species

With the goal of creating a prodrug that allowed for complete biological conversion upon absorption to the active BLI, the metabolic stability of 36 was assessed in vitro in intestinal S9, liver S9, and plasma from CD-1 mice, Sprague-Dawley rats, beagle dogs, cynomolgus monkeys, and humans.40

In intestinal S9, 36 was rapidly cleaved with short half-lives in all species with the exception of beagle dogs (Table 7). Very short half-lives were also observed in liver S9 across all species. No effect on the half-life of 36 was observed when including or excluding NADPH in either intestinal S9 or liver S9, indicating that cytochrome P450 enzymes do not play a role in the hydrolysis. The half-life in human plasma was short at about 11 min, which was closer to what was observed in the rodent species compared to the longer half-lives in dogs (43.9 min) and monkeys (22.0 min). In addition, 5 demonstrated long half-lives (>120 min) in intestinal S9, liver S9, and plasma across all species (data not shown). Overall, 36 was nearly completely hydrolyzed to 5 in all tested matrixes from all species.

Table 7. Metabolic Stability of 36 across Multiple Speciesa.

| intestinal

S9 T1/2 (min) |

liver S9 T1/2 (min) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| species | +NADPH | –NADPH | +NADPH | –NADPH | plasma T1/2 (min) |

| CD-1 mouse | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 4.6 |

| Sprague-Dawley rat | 3.9 | 4.0 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 1.6 |

| beagle dog | 49.0 | 119 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 43.9 |

| cynomolgus monkey | 11.2 | 10.1 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 22.0 |

| human | 2.9 | 3.3 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 10.7 |

Abbreviations: NADPH = nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate.

Compound 36 Yielded Only One Metabolite, 5, in Hepatocytes across Species

An in vitro study to investigate the biotransformation of 36 in cryopreserved hepatocytes from mice, rats, rabbits, beagle dogs, cynomolgus monkeys, and humans was performed.40 After incubation, one metabolite was detected resulting from hydrolysis of 36. The metabolism was extensive in all species with 0–5% 36 remaining. The structure of the metabolite was positively identified as 5 by comparing the observed accurate mass of the metabolite with the observed accurate mass of the authentic chemical standard for 5. No other metabolites were detected in any species tested.

Compound 36 Shows High Permeability through Caco-2 Monolayers

In an effort to gain insight into the absorption potential of 36 in humans, a Caco-2 cell permeability study was undertaken.40

The apparent permeability (Papp) for 36 averaged to 9.22 × 10–6 cm/s, which classifies it as having a high absorption potential in humans (Table 8).41 The active BLI (5) demonstrated poor absorption potential, which further emphasized the need for the prodrug approach for oral delivery.

Table 8. Caco-2 Permeability Results for 36 and 5.

|

Papp (10–6 cm/s) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| test article | direction | recovery (%) | R1 | R2 | avg | efflux Ratioa | absorption potential classificationb | significant effluxc |

| 36 | A-to-B | 90 | 8.25 | 10.2 | 9.22 | 3.2 | high | yes |

| B-to-A | 98 | 28.3 | 30.5 | 29.4 | ||||

| 5 | A-to-B | 103 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 1.4 | low | no |

| B-to-A | 106 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.15 | ||||

Efflux ratio (ER) is Papp (B-to-A)/Papp (A-to-B).

Papp (A-to-B) < 1.0 × 10–6 cm/s: low, Papp (A-to-B) ≥ 1.0 × 10–6 cm/s: high.

ER ≥ 2.0 and Papp (B-to-A) ≥ 1.0 × 10–6 cm/s.

Combination of Ceftibuten and 5 Showed In Vivo Efficacy

In vivo efficacy was demonstrated in a lethal murine septicemia model42 by dosing 5 (subcutaneously) and 36 (orally) with ceftibuten (dosed both subcutaneously with 5 and orally with 36). A comparison of ceftibuten/5 dosed subcutaneously and ceftibuten/36 dosed orally demonstrated similar activity with ED50 (median effective dose) values of 13.5 and 12.9 mg/kg, respectively.43 Additionally, the ability to demonstrate in vivo efficacy in a UTI model which more closely mimics the target cUTI indication in humans was explored. A PK study was performed to guide selection of dosing regimens for the cUTI efficacy study. Oral dosing of 10 and 90 mg/kg of 36 in mice resulted in F = 72% and F = 38% of 5, respectively. The lack of dose proportionality of 5 by oral dosing prompted a transition to subcutaneous dosing for the in vivo efficacy study. A PK study utilizing subcutaneous injections of 1.2, 12, and 38 mg/kg of 5 showed dose proportionality of AUC (7.8, 76, and 250 mg∗h/L, respectively). These results would allow for more control over the exposure of 5 in the efficacy study.

Once the route of administration was selected, the in vivo efficacy study of ceftibuten with and without co-administration of 5 was conducted in the murine ascending the UTI model with three strains of E. coli expressing TEM-1 + CTX-M-15, CTX-M-15, or KPC-2 + SHV-12.44 To establish the ascending UTI model, groups of five female C3H/HeJ mice were placed on 5% glucose water for 6 days and then transurethrally infected with approximately 9 log10 colony forming units (cfu) of each bacterial isolate. Treatments of ceftibuten alone (1–300 mg/kg), ceftibuten with compound 5 1:1 (1–300 mg/kg), and a comparator agent (amoxicillin-clavulanate, 2:1, 10–300 mg/kg) were initiated 4 days post infection and administered subcutaneously every 12 h for 3 days. At day 7 post infection, mean bacterial titers for the three bacterial strains were 6.7 log10 cfu in the kidney, 5.8 log10 cfu in the bladder, and 6.7 log10 cfu/mL in urine for the untreated controls. Administration of ceftibuten alone resulted in minimal cfu reductions in the kidneys and cfu reductions in the bladder and urine that did not exceed 2 log10 at ceftibuten doses of 100 and 300 mg/kg. The addition of 5 to ceftibuten in a 1:1 ratio resulted in increased efficacy, with bacterial titers that were up to 2.0 log10 cfu lower in kidneys, up to 3.2 log10 cfu lower in bladders, and up to 4.0 log10 cfu/mL lower in urine than the corresponding ceftibuten alone doses. The combination of ceftibuten and 5 also showed improved efficacy compared to amoxicillin-clavulanate (2:1) with bacterial titers that were up to 2.3 log10 cfu lower in kidneys, 2.4 log10 cfu lower in bladders, and 3.7 log10 cfu/mL lower in urine. The UTI model demonstrated that 5 rescues ceftibuten activity against uropathogenic strains of E. coli expressing ESBLs or a combination of ESBLs and a KPC carbapenemase.

Conclusions

Starting from a cyclic boronate template, we discovered highly potent inhibitors of Ambler class A, C, and D β-lactamase enzymes that rescued the activity of an oral cephalosporin, ceftibuten, against ceftibuten-resistant E. coli and K. pneumoniae, two frequently isolated species of Enterobacterales causing clinical infections. The synthesis of prodrugs of these active BLIs, followed by comparisons of oral bioavailability in rats, led to the selection of 36. Compound 36 demonstrated excellent oral bioavailability in rats, dogs, and monkeys. Hydrolysis of the prodrug ester to release the active BLI, 5, was demonstrated in multiple species. Compound 5 restored ceftibuten activity in a mouse model of UTI due to ESBL- and KPC-carbapenemase-producing strains of E. coli and K. pneumoniae. Compound 36 is in Phase 1 clinical studies (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04243863).

Experimental Section

General Methods

All solvents and reagents were purchased from commercial vendors and were used without further purification unless otherwise mentioned. Column chromatography was conducted using prepacked silica gel cartridges (Biotage) on a Biotage Isolera Prime system. LC–MS was conducted on an Agilent 1100 series HPLC and 6120 Quadrupole LC/MS in the API-ES mode using a Waters Xbridge C18 column (4.6 mm × 50 mm, 3.5 μm). Mobile phase A was 0.01% trifluoroacetic acid in water, and mobile phase B was 0.01% trifluoroacetic acid in acetonitrile. 1H NMR spectra were recorded using a Varian Mercury 300 MHz spectrometer. The final products were purified by preparative HPLC on a Waters XBridge C18 column (19 mm × 100 mm, 5 μm). The purity of all tested compounds was ≥95%, as determined by HPLC with UV detection at 220 nm and 1H NMR analyses.

Calculations of clog P and tPSA were performed using ChemDraw (Pro, Version 19.0). For clog P, ChemDraw uses the calculator from Biobyte Corp, Claremont, CA (www.biobyte.com).45 For tPSA, calculations were based on fragment contributions using the SMILES Daylight Toolkit module.46

All animal experiments performed in the article were conducted in compliance with institutional guidelines as defined by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

General Method for the Preparation of 3

To a solution of tert-butyl 3-((S)-2-chloro-2-((3aS,4S,6S,7aR)-3a,5,5-trimethylhexahydro-4,6-methanobenzo[d][1,3,2]dioxaborol-2-yl)ethyl)-2-methoxybenzoate (1)15,24 (1.35 g, 3 mmol) in THF (9 mL) at −78 °C was added dropwise a solution of lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide (3.0 mL, 1 M in THF, 3 mmol). Following addition, the bath was removed and stirring was continued for 17 h. The resulting solution, containing approximately 0.25 M of intermediate 2 in THF, was used without further purification.

To a mixture of carboxylic acid (1 mmol) and HATU (1.1 mmol) was added dimethylacetamide (DMA) (3 mL), followed by N-methyl-morpholine (1.1 mmol). The resulting solution was stirred for 90 min. To this solution was added a solution of 2 (1 mmol). The resulting mixture was stirred for 2.5 h, diluted with ethyl acetate (EtOAc), washed with water and brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated. The residue was purified by silica gel chromatography (10 g of silica; eluted with 20–100% EtOAc/hexanes) to provide amide 3 (50–70% yield).

General Method for the Preparation of 4

To a solution of amide 3 (0.30 mmol) in anhydrous DCM (5 mL) at −78 °C was added BCl3 (1 M in DCM, 2.1 mmol). After 1 h, the reaction mixture was warmed to 0 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred for 1 h and quenched by addition of water (5 mL) at 0 °C. The aqueous phase was washed with DCM and then purified by reverse-phase preparative HPLC. The product-containing fractions were combined and lyophilized to dryness to give carboxylic acids 5–14 (40–70% yield).

(R)-2-Hydroxy-3-propionamido-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylic Acid (5)

Prepared from the general methods for 3 and 4. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 10.19 (s, 1H), 7.82 (d, 1H, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.25 (d, 1H, J = 7.1 Hz), 6.98 (t, 1H, J = 7.5 Hz), 3.20 (s, 1H), 2.90 (m, 2H), 2.20 (m, 2H), 0.90 (t, 3H, J = 7.5 Hz). ESI-MS m/z: 264 (M + H)+.

(R)-3-Butyramido-2-hydroxy-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylic Acid (6)

Prepared from the general methods for 3 and 4. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 10.22 (s, 1H), 7.85 (d, 1H), 7.32 (d, 1H), 6.90 (t, 1H), 3.27 (s, 1H), 2.94 (m, 2H), 2.31 (m, 1H), 2.22 (m, 1H), 1.43 (q, 2H), 0.53 (t, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 278 (M + H)+.

(R)-2-Hydroxy-3-(4,4,4-trifluorobutanamido)-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylic Acid (7)

Prepared from the general methods for 3 and 4. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 10.45 (s, 1H), 7.85 (d, 1H), 7.33 (d, 1H), 6.97 (t, 1H), 4.80 (m, 1H), 2.96 (m, 2H), 2.69 (m, 2H), 2.64 (m, 2H). ESI-MS m/z: 332 (M + H)+.

(R)-3-(3-Cyanopropanamido)-2-hydroxy-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylic Acid (8)

Prepared from the general methods for 3 and 4. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 10.6 (s, 1H), 7.38 (d, 1H), 7.32 (d, 1H), 6.97 (t, 1H), 4.90 (m, 1H), 2.94 (m, 2H), 2.62 (m, 2H), 2.40 (m, 2H). ESI-MS m/z: 289 (M + H)+.

(R)-2-Hydroxy-3-(4-oxopentanamido)-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylic Acid (9)

Prepared from the general methods for 3 and 4. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 10.2 (s, 1H), 7.74 (d, 1H), 7.24 (d, 1H), 6.90 (t, 1H), 4.78 (m, 1H), 3.22 (m, 1H), 2.62 (m, 2H), 2.38 (m, 2H), 1.91 (s, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 306 (M + H)+.

(R)-3-(4-Amino-4-oxobutanamido)-2-hydroxy-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylic Acid (10)

Prepared from the general methods for 3 and 4. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 7.85 (d, 1H), 7.33 (d, 1H), 6.98 (t, 1H), 4.85 (m, 1H), 3.92 (m, 2H), 2.35–2.60 (m, 4H). ESI-MS m/z: 307 (M + H)+.

(R)-2-Hydroxy-3-(3-(methylsulfonamido)propanamido)-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylic Acid (11)

Prepared from the general methods for 3 and 4. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 7.83 (d, 1H), 7.32 (d, 1H), 6.97 (t, 1H), 4.90 (m, 1H), 3.18–3.26 (m, 2H), 2.95 (m, 2H), 2.85 (s, 3H), 2.55 (m, 2H). ESI-MS m/z: 357 (M + H)+.

(R)-2-Hydroxy-3-(pent-4-ynamido)-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylic Acid (12)

Prepared from the general methods for 3 and 4. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 10.4 (s, 1H), 7.83 (d, 1H), 7.32 (d, 1H), 6.98 (t, 1H), 4.95 (m, 1H), 2.95 (m, 2H), 2.45–2.80 (m, 2H), 2.40 (m, 2H), 1.95 (s, 1H). ESI-MS m/z: 288 (M + H)+.

(R)-2-Hydroxy-3-(3-sulfamoylpropanamido)-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylic Acid (13)

Prepared from the general methods for 3 and 4. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 7.83 (d, 1H), 7.34 (d, 1H), 6.98 (t, 1H), 4.95 (m, 1H), 3.05–3.25 (m, 2H), 2.95 (m, 2H), 2.80 (m, 2H). ESI-MS m/z: 343 (M + H)+.

(R)-3-(4,4-Difluoropentanamido)-2-hydroxy-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylic Acid (14)

Prepared from the general methods for 3 and 4. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 10.38 (s, 1H), 7.83 (d, 1H), 7.30 (d, 1H), 6.96 (t, 1H), 4.85 (m, 1H), 2.92 (m, 2H), 2.50 (m, 2H), 2.05 (m, 2H), 1.43 (t, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 328 (M + H)+.

General Method for the Preparation of 15

To a solution of carboxylic acid 4 (1.28 mmol) in ethanol (30 mL) was added 4 N HCl in dioxane (6 mL). The solution was stirred at 40 °C for 18 h, concentrated in vacuo, purified by reverse-phase flash chromatography, and dried using lyophilization (20–40% yield).

Ethyl (R)-2-Hydroxy-3-propionamido-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylate (19)

Prepared from the general method for 15. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 7.35 (d, 1H), 7.19 (d, 1H), 6.85 (t, 1H), 4.05 (m, 2H), 3.45 (m, 1H), 2.58 (m, 2H), 2.03–2.45 (m, 2H), 1.10 (m, 3H), 0.92 (m, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 292 (M + H)+.

Ethyl (R)-3-Butyramido-2-hydroxy-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylate (21)

Prepared from the general method for 15. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 9.05 (s, 1H), 7.45 (d, 1H), 7.12 (d, 1H), 6.78 (t, 1H), 4.30 (m, 2H), 3.05 (m, 1H), 2.79 (m, 2H), 2.20 (m, 2H), 1.38 (m, 5H), 0.50 (m, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 306 (M + H)+.

Ethyl (R)-3-(3-Cyanopropanamido)-2-hydroxy-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylate (23)

Prepared from the general method for 15. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 10.15 (s, 1H), 7.48 (d, 1H), 7.17 (d, 1H), 6.80 (t, 1H), 4.30 (q, 2H), 3.10 (m, 1H), 2.83 (m, 2H), 2.62 (m, 4H), 1.38 (t, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 317 (M + H)+.

Ethyl (R)-2-Hydroxy-3-(4-oxopentanamido)-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylate (25)

Prepared from the general method for 15. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 9.85 (s, 1H), 7.45 (d, 1H), 7.18 (d, 1H), 6.81 (t, 1H), 4.32 (q, 2H), 3.05 (m, 1H), 2.82 (m, 2H), 2.62 (m, 2H), 2.42 (m, 2H), 1.98 (s, 3H), 1.38 (t, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 334 (M + H)+.

Ethyl (R)-3-(4-Amino-4-oxobutanamido)-2-hydroxy-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylate (27)

Prepared from the general method for 15. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 9.90 (s, 1H), 7.45 (d, 1H), 7.18 (d, 1H), 6.80 (t, 1H), 4.32 (q, 2H), 3.05 (m, 1H), 2.80 (m, 2H), 2.48 (m, 2H), 2.30 (m, 2H), 1.38 (t, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 335 (M + H)+.

Ethyl (R)-2-Hydroxy-3-(3-(methylsulfonamido)propanamido)-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylate (29)

Prepared from the general method for 15. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 10.02 (s, 1H), 7.45 (d, 1H), 7.18 (d, 1H), 6.81 (t, 1H), 4.34 (q, 2H), 3.18 (m, 2H), 3.05 (m, 1H), 2.82 (m, 2H), 2.80 (s, 3H), 2.50 (m, 2H), 1.40 (t, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 385 (M + H)+.

Ethyl (R)-2-Hydroxy-3-(3-sulfamoylpropanamido)-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylate (31)

Prepared from the general method for 15. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 10.05 (s, 1H), 7.42 (d, 1H), 7.12 (d, 1H), 6.78 (t, 1H), 4.25 (q, 2H), 3.18 (m, 2H), 3.03 (m, 1H), 2.85 (m, 2H), 2.65 (m, 2H), 1.36 (t, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 371 (M + H)+.

General Methods for the Preparation of 16

Method A: A solution of benzoic acid tert-butyl ester 3 (2.35 mmol) and 4 N HCl in dioxane (18 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 7 h. The reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo and azeotroped two times with toluene. The crude product was carried forward without purification.

Method B: Trifluoroacetic acid (1.6 mL) was added to a solution of benzoic acid tert-butyl ester 3 (0.71 mmol) in DCM (8 mL), and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 30 min. The reaction mixture was concentrated, and the product was azeotroped with toluene and carried forward without further purification.

General Method for the Preparation of 17

To a solution of 16 (0.53 mmol) in DMF (2.5 mL) under argon was added sodium carbonate (1.07 mmol), and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 5 min. Chloromethyl pivalate (0.902 mmol) in DMF (0.4 mL) was added, followed by sodium iodide (0.280 mmol), and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 18 h. The reaction mixture was quenched with water and extracted three times with EtOAc. The combined organic layers were washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel (10–100% EtOAc/hexanes) (50–70% yield).

General Method for the Preparation of 18

Aluminum chloride (3.31 mmol) was added to a solution of 17 (0.41 mmol) in DCM (10 mL), and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 18 h. The reaction mixture was quenched with water and methanol, concentrated, purified by reverse-phase HPLC, and dried using lyophilization to provide the desired prodrugs (20–40% yield).

(Pivaloyloxy)methyl (R)-2-Hydroxy-3-propionamido-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylate (20)

Prepared from general methods for 16–18. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 9.80 (s, 1H), 7.58 (d, 1H, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.20 (d, 1H, J = 7.1 Hz), 6.80 (t, 1H, J = 7.5 Hz), 5.98 (s, 2H), 3.05 (s, 1H), 2.82 (m, 2H), 2.20 (m, 2H), 1.20 (s, 9H), 0.90 (t, 3H, J = 7.5 Hz). ESI-MS m/z: 400 (M + Na)+.

(Pivaloyloxy)methyl (R)-3-Butyramido-2-hydroxy-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylate (22)

Prepared from general methods for 16–18. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 10.18 (s, 1H), 7.85 (d, 1H), 7.50 (d, 1H), 7.12 (t, 1H), 6.23 (s, 2H), 3.38 (m, 1H), 3.15 (m, 2H), 2.50 (m, 2H), 1.68 (m, 2H), 1.52 (s, 9H), 0.82 (t, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 414 (M + Na)+.

(Pivaloyloxy)methyl (R)-3-(3-Cyanopropanamido)-2-hydroxy-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylate (24)

Prepared from general methods for 16–18. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 10.0 (s, 1H), 7.53 (d, 1H), 7.20 (d, 1H), 6.81 (t, 1H), 5.94 (s, 2H), 3.12 (m, 1H), 2.83 (m, 2H), 2.61 (m, 2H), 1.23 (s, 9H). ESI-MS m/z: 424 (M + Na)+.

(Pivaloyloxy)methyl (R)-2-Hydroxy-3-(4-oxopentanamido)-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylate (26)

Prepared from general methods for 16–18. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 9.90 (s, 1H), 7.53 (d, 1H), 7.20 (d, 1H), 6.82 (t, 1H), 5.93 (s, 2H), 3.03 (m, 1H), 2.82 (m, 2H), 2.62 (m, 2H), 2.41 (m, 2H), 1.98 (s, 3H), 1.21 (s, 9H). ESI-MS m/z: 442 (M + Na)+.

(Pivaloyloxy)methyl (R)-3-(4-Amino-4-oxobutanamido)-2-hydroxy-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylate (28)

Prepared from general methods for 16–18. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 9.92 (s, 1H), 7.53 (d, 1H), 7.20 (d, 1H), 6.80 (t, 1H), 5.98 (d, 2H), 3.05 (m, 1H), 2.85 (m, 2H), 2.62 (m, 2H), 2.43 (m, 2H), 1.21 (s, 9H). ESI-MS m/z: 443 (M + Na)+.

(Pivaloyloxy)methyl (R)-2-Hydroxy-3-(3-(methylsulfonamido)propanamido)-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylate (30)

Prepared from general methods for 16–18. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 7.68 (d, 1H), 7.47 (m, 1H), 7.20 (m, 1H), 5.98 (s, 2H), 3.38 (m, 1H), 3.15 (m, 2H), 2.97 (s, 3H), 2.80 (m, 2H), 2.63 (m, 2H), 1.21 (s, 9H). ESI-MS m/z: 493 (M + Na)+.

(Pivaloyloxy)methyl (R)-2-Hydroxy-3-(3-sulfamoylpropanamido)-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylate (32)

Prepared from general methods for 16–18. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 7.65 (d, 1H), 7.52 (m, 1H), 7.18 (m, 1H), 5.95 (s, 2H), 3.79 (m, 2H), 3.19 (m, 1H), 2.88 (m, 2H), 2.75 (m, 2H), 1.20 (s, 9H). ESI-MS m/z: 479 (M + Na)+.

(Benzoyloxy)methyl (R)-2-Hydroxy-3-propionamido-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylate (33)

Prepared from general methods for 16–18 utilizing chloromethyl benzoate in place of chloromethyl pivalate in the preparation of 17. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 9.02 (s, 1H), 8.08 (d, 2H), 7.62 (m, 2H), 7.53 (m, 2H), 7.20 (d, 1H), 6.81 (t, 1H), 6.22 (dd, 2H), 3.05 (s, 1H), 2.83 (m, 2H), 2.18 (q, 2H), 0.88 (t, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 420 (M + Na)+.

Acetoxymethyl (R)-2-Hydroxy-3-propionamido-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylate (34)

Prepared from general methods for 16–18 utilizing chloromethyl acetate in place of chloromethyl pivalate in the preparation of 17. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 7.59 (m, 1H), 7.21 (m, 1H), 6.82 (m, 1H), 5.97 (m, 2H), 3.06 (s, 1H), 2.80 (m, 2H), 2.22 (m, 2H), 2.12 (s, 3H), 0.90 (m, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 336 (M + H)+.

(Isobutyryloxy)methyl (R)-2-Hydroxy-3-propionamido-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylate (35)

Prepared from general methods for 16–18 utilizing chloromethyl isobutyrate in place of chloromethyl pivalate in the preparation of 17. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 9.02 (s, 1H), 7.58 (d, 1H), 7.21 (d, 1H), 6.81 (t, 1H), 5.98 (m, 2H), 3.04 (s, 1H), 2.83 (m, 2H), 2.23 (m, 3H), 1.60 (m, 6H), 0.92 (t, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 386 (M + Na)+.

((2-Ethylbutanoyl)oxy)methyl (R)-2-Hydroxy-3-propionamido-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylate (36)

Prepared from the general methods for 16–18 utilizing chloromethyl 2-ethylbutanoate in place of chloromethyl pivalate in the preparation of 17. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 9.82 (s, 1H), 7.60 (d, 1H, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.21 (d, 1H, J = 7.1 Hz), 6.80 (t, 1H, J = 7.5 Hz), 5.98 (s, 2H), 3.12 (s, 1H), 2.82 (m, 2H), 2.20 (m, 3H), 1.60 (m, 4H), 0.91 (m, 9H). ESI-MS m/z: 414 (M + Na)+.

((Isopropoxycarbonyl)oxy)methyl (R)-2-Hydroxy-3-propionamido-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylate (37)

Prepared from general methods for 16–18 utilizing chloromethyl isopropyl carbonate in place of chloromethyl pivalate in the preparation of 17. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 9.03 (s, 1H), 7.59 (d, 1H), 7.21 (d, 1H), 6.81 (t, 1H), 5.95 (m, 2H), 4.85 (m, 1H), 3.04 (s, 1H), 2.83 (m, 2H), 2.22 (m, 2H), 1.28 (m, 6H), 0.92 (t, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 402 (M + Na)+.

((2-Ethoxy-2-methylpropanoyl)oxy)methyl (R)-2-Hydroxy-3-propionamido-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylate (38)

Prepared from general methods for 16–18 utilizing chloromethyl 2-ethoxy-2-methylpropanoate in place of chloromethyl pivalate in the preparation of 17. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 9.02 (s, 1H), 7.59 (d, 1H), 7.21 (d, 1H), 6.81 (t, 1H), 5.99 (m, 2H), 3.45 (m, 2H), 3.04 (s, 1H), 2.82 (m, 2H), 2.21 (m, 2H), 1.40 (s, 6H), 1.12 (t, 3H), 0.89 (t, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 430 (M + Na)+.

(((Pentan-3-yloxy)carbonyl)oxy)methyl (R)-2-Hydroxy-3-propionamido-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylate (39)

Prepared from general methods for 16–18 utilizing chloromethyl pentan-3-yl carbonate in place of chloromethyl pivalate in the preparation of 17. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 9.02 (s, 1H), 7.59 (m, 1H), 7.21 (m, 1H), 6.81 (m, 1H), 5.94 (m, 2H), 4.60 (m, 1H), 3.04 (s, 1H), 2.82 (m, 2H), 2.20 (m, 2H), 1.62 (m, 4H), 0.90 (m, 9H). ESI-MS m/z: 430 (M + Na)+.

((Cyclopentanecarbonyl)oxy)methyl (R)-2-Hydroxy-3-propionamido-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylate (40)

Prepared from general methods for 16–18 utilizing chloromethyl cyclopentanecarboxylate in place of chloromethyl pivalate in the preparation of 17. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 9.02 (s, 1H), 7.58 (d, 1H), 7.20 (d, 1H), 6.81 (t, 1H), 5.93 (m, 2H), 3.04 (s, 1H), 2.82 (m, 2H), 2.21 (m, 2H), 1.55–1.98 (m, 9H), 0.90 (t, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 412 (M + Na)+.

(((Cyclopentyloxy)carbonyl)oxy)methyl (R)-2-Hydroxy-3-propionamido-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinine-8-carboxylate (41)

Prepared from general methods for 16–18 utilizing chloromethyl cyclopentyl carbonate in place of chloromethyl pivalate in the preparation of 17. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 9.02 (s, 1H), 7.58 (d, 1H), 7.21 (d, 1H), 6.81 (t, 1H), 5.93 (m, 2H), 5.10 (m, 1H), 3.04 (s, 1H), 2.82 (m, 2H), 2.22 (m, 2H), 1.58–1.95 (m, 8H), 0.93 (t, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 428 (M + Na)+.

Acknowledgments

This project has been funded in whole or in part from the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract no. HHSN272201600029C and grant nos. R44AI109879, R01AI089512, R01AI111539, and R43AI109879.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AUC

area under the concentration–time curve

- BL

β-lactam antibiotic

- BLI

β-lactamase inhibitor

- cfu

colony-forming unit

- CRE

carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae spp.

- DCM

dichloromethane

- DMA

dimethyl acetamide

- DMF

N,N-dimethylformamide

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- ESBL

extended spectrum β-lactamase

- EtOAc

ethyl acetate

- F

absolute oral bioavailability

- HATU

1-[bis(dimethylamino)methylene]-1H-1,2,3-triazolo[4,5-b]pyridinium-3-oxide hexafluorophosphate

- HR-MS/MS

hi-res tandem mass spectrometry

- KPC

Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase

- MBL

metallo-β-lactamase

- MDR

multi-drug-resistant

- MIC

minimum inhibitory concentration

- NADPH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- PK

pharmacokinetics

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

- SBL

serine-β-lactamase

- UPLC

ultra-performance liquid chromatography

- UTI

urinary tract infection

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00437.

Inhibition assays, antimicrobial susceptibility testing, PK screening studies, mouse PK studies, metabolic stability, metabolite profiling, bidirectional permeability through Caco-2 monolayers, mouse efficacy study, HPLC method and HPLC of compounds 5 and 36, and 1H NMR of compounds 5 and 36 (PDF)

Molecular formula strings (CSV)

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): R.T., A.Z., E.M., R.J., S.B., B.L., J.H., D.D., C.C., K.J., L.M., S.C., D.P., G.M., L.X., C.B. are employees of and/or shareholders in Venatorx Pharmaceuticals.

Supplementary Material

References

- Klein E. Y.; Van Boeckel T. P.; Martinez E. M.; Pant S.; Gandra S.; Levin S. A.; Goossens H.; Laxminarayan R. Global Increase and Geographic Convergence in Antibiotic Consumption Between 2000 and 2015. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2018, 115, E3463–E3470. 10.1073/pnas.1717295115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley A. M.; Mathema B.; Larson E. L. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in the Community: a Scoping Review. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2017, 50, 127–134. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tooke C. L.; Hinchliffe P.; Bragginton E. C.; Colenso C. K.; Hirvonen V. H. A.; Takebayashi Y.; Spencer J. β-Lactamases and β-lactamase Inhibitors in the 21st Century. J. Mol. Biol. 2019, 431, 3472. 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K.; Bradford P. A. Interplay Between Beta-lactamases and New Beta-lactamase Inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 295–306. 10.1038/s41579-019-0159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrill H. J.; Morton J. B.; Caffrey A. R.; Jiang L.; Dosa D.; Mermel L. A.; LaPlante K. L. Antimicrobial Resistance of Escherichia coli Urinary Isolates in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e02236 10.1128/AAC.02236-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . Antimicrobial Resistance in the EU/EEA (EARS-Net)-Annual Epidemiological Report 2019; ECDC: Stockholm, 2020.

- Gupta K.; Hooton T. M.; Naber K. G.; Wullt B.; Colgan R.; Miller L. G.; Moran G. J.; Nicolle L. E.; Raz R.; Schaeffer A. J.; Soper D. E. Infectious Diseases Society of America; European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. International Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Acute Uncomplicated Cystitis and Pyelonephritis in Women: A 2010 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 52, e103–e120. 10.1093/cid/ciq257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamma P. D.; Aitken S. L.; Bonomo R. A.; Mathers A. J.; van Duin D.; Clancy C. J. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidance on the Treatment of Extended-Spectrum β-lactamase Producing Enterobacterales (ESBL-E), Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales (CRE), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa with Difficult-to-Treat Resistance (DTR-P. aeruginosa). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, e169–e183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslikowska J. A.; Walker S. A. N.; Elligsen M.; Mittmann N.; Palmay L.; Daneman N.; Simor A. Impact of Infection with Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli or Klebsiella Species on Outcome and Hospitalization Costs. J. Hosp. Infect. 2016, 92, 33–41. 10.1016/j.jhin.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley I. A.; Cotroneo N.; Pucci M. J.; Mendes R. The Burden of Antimicrobial Resistance Among Urinary Tract Isolates of Escherichia coli in the United States in 2017. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0220265 10.1371/journal.pone.0220265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain A.; Utley L.; Parr T. R.; Zabawa T.; Pucci M. J. Tebipenem, the First Oral Carbapenem Antibiotic. Expert Rev. Anti-infect. Ther. 2018, 16, 513–522. 10.1080/14787210.2018.1496821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlowsky J. A.; Adam H. J.; Baxter M. R.; Denisuik A. J.; Lagace-Wiens P. R. S.; Walkty A. J.; Puttagunta S.; Dunne M. W.; Zhanel G. G. In vitro Activity of Sulopenem, an Oral Penem, Against Urinary Osolates of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 63, e01832 10.1128/aac.01832-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theuretzbacher U.; Bush K.; Harbarth S.; Paul M.; Rex J. H.; Tacconelli E.; Thwaites G. E. Critical Analysis of Antibacterial Agents in Clinical Development. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 286–298. 10.1038/s41579-020-0340-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecker S. J.; Reddy K. R.; Totrov M.; Hirst G. C.; Lomovskaya O.; Griffith D. C.; King P.; Tsivkovski R.; Sun D.; Sabet M.; Tarazi Z.; Clifton M. C.; Atkins K.; Raymond A.; Potts K. T.; Abendroth J.; Boyer S. H.; Loutit J. S.; Morgan E. E.; Durso S.; Dudley M. N. Discovery of a Cyclic Boronic Acid β-lactamase Inhibitor (RPX7009) with Utility vs Class A Serine Carbapenemases. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 3682–3692. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B.; Trout R. E. L.; Chu G.-H.; McGarry D.; Jackson R. W.; Hamrick J. C.; Daigle D. M.; Cusick S. M.; Pozzi C.; De Luca F.; Benvenuti M.; Mangani S.; Docquier J.-D.; Weiss W. J.; Pevear D. C.; Xerri L.; Burns C. J. Discovery of Taniborbactam (VNRX-5133): A Broad-Spectrum Serine- and Metallo-β-lactamase Inhibitor for Carbapenem-Resistant Bacterial Infections. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 2789–2801. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamrick J. C.; Docquier J. D.; Uehara T.; Myers C. L.; Six D. A.; Chatwin C. L.; John K. J.; Vernacchio S. F.; Cusick S. M.; Trout R. E. L.; Pozzi C.; De Luca F.; Benvenuti M.; Mangani S.; Liu B.; Jackson R. W.; Moeck G.; Xerri L.; Burns C. J.; Pevear D. C.; Daigle D. M. VNRX-5133 (Taniborbactam), a Broad-Spectrum Inhibitor of Serine- and Metallo-β-lactamases, Restores Activity of Cefepime in Enterobacterales and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e01963 10.1128/AAC.01963-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecker S. J.; Reddy K. R.; Lomovskaya O.; Griffith D. C.; Rubio-Aparicio D.; Nelson K.; Tsivkovski R.; Sun D.; Sabet M.; Tarazi Z.; Parkinson J.; Totrov M.; Boyer S. H.; Glinka T. W.; Pemberton O. A.; Chen Y.; Dudley M. N. Discovery of Cyclic Boronic Acid QPX7728, an Ultrabroad-Spectrum Inhibitor of Serine and Metallo-β-lactamases. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 7491–7507. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiener P. A.; Waley S. G. Reversible Inhibitors of Penicillinases. Biochem. J. 1978, 169, 197–204. 10.1042/bj1690197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eidam O.; Romagnoli C.; Dalmasso G.; Barelier S.; Caselli E.; Bonnet R.; Shoichet B. K.; Prati F. Fragment-guided Design of Subnanomolar β-lactamase Inhibitors Active In Vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012, 109, 17448–17453. 10.1073/pnas.1208337109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morandi F.; Caselli E.; Morandi S.; Focia P. J.; Blázquez J.; Shoichet B. K.; Prati F. Nanomolar Inhibitors of AmpC Beta-lactamase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 685–695. 10.1021/ja0288338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morandi S.; Morandi F.; Caselli E.; Shoichet B. K.; Prati F. Structure-based Optimization of Cephalothin-analogue Boronic Acids as β-lactamase Inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 1195–1205. 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.10.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strynadka N. C. J.; Martin R.; Jensen S. E.; Gold M.; Jones J. B. Structure-based Design of a Potent Transition State Analogue for TEM-1 Beta-lactamase. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1996, 3, 688–695. 10.1038/nsb0896-688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns C. J.; Jackson R. W.. Beta-lactamase Inhibitors. WO 2009064413 A1, 2009.

- Burns C. J.; Jackson R. W.; Goswami R.; Xu H.. Beta-lactamase Inhibitors. WO 2009064414 A1, 2009.

- Burns C. J.; Goswami R.; Jackson R. W.; Lessen T.; Li W.; Pevear D.; Tirunahari P. K.; Xu H.. Beta-lactamase Inhibitors. WO 2010130708 A1, 2010.

- Burns C. J.; Trout R.; Zulli A.; Mesaros E.; Jackson R.; Boyd S.; Liu B.; McLaughlin L.; Chatwin C.; Hamrick J.; Daigle D.; Pevear D.. Discovery of VNRX-7145: A Broad-spectrum Orally Bioavailable Beta-lactamase Inhibitor (BLI) for Highly Resistant Bacterial Infections (“Superbugs”). Presented at the 257th National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society: U.S.: Orlando, FL, Mar 31–Apr 4, 2019; MEDI-0259.

- Burns C. J.; Pevear D. C.; Trout R. E. L.; Jackson R. W.; Hamrick J.; Zulli A. L.; Mesaros E. F.; Boyd S. A.. Preparation of Oxaborinine Compounds Useful as Beta-lactamase Inhibitors. WO 2017100537 A1, 2017.

- Jones R. N.; Barry A. L. Ceftibuten (7432-S, SCH 39720): Comparative Antimicrobial Activity Against 4735 Clinical Isolates, Beta-lactamase Stability and Broth Microdilution Quality Control Guidelines. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1988, 7, 802–807. 10.1007/bf01975055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tärnberg M.; Östholm-Balkhed Å.; Monstein H.-J.; Hällgren A.; Hanberger H.; Nilsson L. E. In Vitro Activity of Beta-lactam Antibiotics Against CTX-M-producing Escherichia coli. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2011, 30, 981–987. 10.1007/s10096-011-1183-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T.; Komatsu M.; Yamasaki K.; Fukuda S.; Higuchi T.; Ono T.; Nishio H.; Sueyoshi N.; Kida K.; Satoh K.; Toda H.; Toyokawa M.; Nishi I.; Sakamoto M.; Akagi M.; Mizutani T.; Nakai I.; Kofuku T.; Orita T.; Zikimoto T.; Natsume S.; Wada Y. Susceptibility of Various Oral Antibacterial Agents Against Extended Spectrum β-lactamase Producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Infect. Chemother. 2014, 20, 48–51. 10.1016/j.jiac.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatwin C. L.; Hamrick J. C.; John K. J.; Burns C. J.; Xerri L.; Moeck G.; Pevear D. C.. Selection of Ceftibuten as the Partner Antibiotic for the Oral β-lactamase Inhibitor VNRX-7145; European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ECCMID): Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ness S.; Martin R.; Kindler A. M.; Paetzel M.; Gold M.; Jensen S. E.; Jones J. B.; Strynadka N. C. J. Structure-based Design Guides the Improved Efficacy of Deacylation Transition State Analogue Inhibitors of TEM-1 Beta-lactamase. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 5312–5321. 10.1021/bi992505b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea R.; Moser H. E. Physicochemical Properties of Antibacterial Compounds: Implications for Drug Discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 2871–2878. 10.1021/jm700967e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veber D. F.; Johnson S. R.; Cheng H.-Y.; Smith B. R.; Ward K. W.; Kopple K. D. Molecular Properties that Influence the Oral Bioavailability of Drug Candidates. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 2615–2623. 10.1021/jm020017n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J. J.; Crimin K.; Goodwin J. T.; Crivori P.; Orrenius C.; Xing L.; Tandler P. J.; Vidmar T. J.; Amore B. M.; Wilson A. G. E.; Stouten P. F. W.; Burton P. S. Influence of Molecular Flexibility and Polar Surface Area Metrics on Oral Bioavailability in the Rat. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 6104–6107. 10.1021/jm0306529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matteson D. S. α-Halo Boronic Esters in Asymmetric Synthesis. Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 10555–10607. 10.1016/s0040-4020(98)00321-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing . Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters, Version 11.0, 2021. http://www.eucast.org (accessed 30 Apr 2021).

- Brass E. P. Pivalate-Generating Prodrugs and Carnitine Homeostasis in Man. Pharmacol. Rev. 2002, 54, 589–598. 10.1124/pr.54.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todesco L.; Bodmer M.; Vonwil K.; Häussinger D.; Krähenbühl S. Interaction Between Pivaloylcarnitine and L-Carnitine Transport into L6 Cells Overexpressing hOCTN2. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2009, 180, 472–477. 10.1016/j.cbi.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trout R. E.; Chatwin C. L.; McLaughlin L.; Hamrick J. C.; Moeck G.; Pevear D. C.. In Vitro Permeability and Metabolic Biotransformation of Oral β-lactamase Inhibitor VNRX-7145 across Species; American Society for Microbiology (ASM) Microbe: San Francisco, CA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Artursson P.; Karlsson J. Correlation Between Oral Drug Absorption in Humans and Apparent Drug Permeability Coefficients in Human Intestinal Epithelial (Caco-2) Cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1991, 175, 880–885. 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91647-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss W. J.; Petersen P. J.; Murphy T. M.; Tardio L.; Yang Y.; Bradford P. A.; Venkatesan A. M.; Abe T.; Isoda T.; Mihira A.; Ushirogochi H.; Takasake T.; Projan S.; O’Connell J.; Mansour T. S. In Vitro and In Vivo Activities of Novel 6-methylidene Penems as Beta-lactamase Inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 4589–4596. 10.1128/aac.48.12.4589-4596.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatwin C. L.; Hamrick J. C.; Trout R. E. L.; Myers C. L.; Cusick S. M.; Weiss W. J.; Pulse M. E.; Xerri L.; Burns C. J.; Moeck G.; Daigle D. M.; John K.; Uehara T.; Pevear D. C. Microbiological Characterization of VNRX-5236: a Broad Spectrum β-lactamase Inhibitor for Rescue of the Orally Bioavailable Cephalosporin Ceftibuten as a Carbapenem-sparing Agent Against Strains of Enterobacterales Expressing Extended Spectrum β-lactamases and Serine Carbapenemases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, AAC.00552-21. 10.1128/aac.00552-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; . in press

- Pulse M. E.; Weiss W. J.; Nguyen P.; Valtierra D.; Peterson K.; Carter K.; Weiss J.; Deviney A.; Elmquist G.; Moeck G.; Trout R. E.; Hamrick J.; Pevear D. C.. Efficacy of Ceftibuten + VNRX-7145, a Novel β-lactamase Inhibitor, against KPC-2 and ESBL E. coli Strains in a Murine UTI Model; American Society for Microbiology (ASM) Microbe: San Francisco, CA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Leo A. J. Calculating log Poct from Structures. Chem. Rev. 1993, 93, 1281–1306. 10.1021/cr00020a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ertl P.; Rohde B.; Selzer P. Fast Calculation of Molecular Polar Surface Area as a Sum of Fragment-based Contributions and Its Application to the Prediction of Drug Transport Properties. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43, 3714–3717. 10.1021/jm000942e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.