Abstract

Objective

To describe patient characteristics, symptoms, patterns of care and outcomes for patients hospitalised with COVID-19 in Michigan.

Design

Multicentre retrospective cohort study.

Setting

32 acute care hospitals in the state of Michigan.

Participants

Patients discharged (16 March–11 May 2020) with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 were identified. Trained abstractors collected demographic information on all patients and detailed clinical data on a subset of COVID-19-positive patients.

Primary outcome measurements

Patient characteristics, treatment and outcomes including cardiopulmonary resuscitation, mortality and venous thromboembolism within and across hospitals.

Results

Demographic-only data from 1593 COVID-19-positive and 1259 persons under investigation discharges were collected. Among 1024 cases with detailed data, the median age was 63 years; median body mass index was 30.6; and 51.4% were black. Cough, fever and shortness of breath were the top symptoms. 37.2% reported a known COVID-19 contact; 7.0% were healthcare workers; and 16.1% presented from congregated living facilities.

During hospitalisation, 232 (22.7%) patients were treated in an intensive care unit (ICU); 558 (54.9%) in a ‘cohorted’ unit; 161 (15.7%) received mechanical ventilation; and 90 (8.8%) received high-flow nasal cannula. ICU patients more often received hydroxychloroquine (66% vs 46%), corticosteroids (34% vs 18%) and antibiotic therapy (92% vs 71%) than general ward patients (p<0.05 for all). Overall, 219 (21.4%) patients died, with in-hospital mortality ranging from 7.9% to 45.7% across hospitals. 73% received at least one COVID-19-specific treatment, ranging from 32% to 96% across sites.

Across 14 hospitals, the proportion of patients admitted directly to an ICU ranged from 0% to 43.8%; mechanical ventilation on admission from 0% to 12.8%; mortality from 7.9% to 45.7%. Use of at least one COVID-19-specific therapy varied from 32% to 96.3% across sites.

Conclusions

During the early days of the Michigan outbreak of COVID-19, patient characteristics, treatment and outcomes varied widely within and across hospitals.

Keywords: COVID-19, quality in healthcare, protocols & guidelines

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Using rigorous data collection including a well-defined sampling strategy and trained data abstractors, our paper is the largest multihospital study to examine clinical aspects related to COVID-19 in Michigan.

This is the first study to examine variations in clinical care processes, treatment approaches and outcomes across hospitals.

The high rate of use of non-evidence-based therapies for treating COVID-19 has significant safety, economic and policy implications for the most critically ill subsets in the hospital.

Given the observational nature of the study and potential missing documentation on symptoms, comorbidities or treatments in the medical record, rationales for treatment or management decisions cannot be determined.

Our sampling frame may be biased as patients who remain hospitalised may not be included in our cohort.

Introduction

Since detection in Wuhan, China,1 2 over 4.5 million cases of COVID-19, caused by SARS-CoV-2, have been reported.3 The USA leads the world in the total number of cases, with over 1.5 million cases and 92 000 deaths reported as of 20 May 2020.4 Within the USA, Michigan remains one of the hardest hit states, with over 52 000 cases and 5000 deaths as of 20 May 2020.5

In the early days of the pandemic, data regarding patient characteristics, symptoms and signs and presentation and care strategies, including aspects such as oxygenation, laboratory testing and therapeutics, were unclear. As well, short-term and long-term outcomes of patients exposed to these varying approaches were unknown. Some studies reported substantial variation in patient characteristics and treatment modalities across hospitals. However, the extent of such variation and impact on outcomes remained unknown.

Michigan has a long history of collaborative quality improvement work that spans several disciplines including cardiovascular medicine, emergency medicine and hospital medicine, among others.6 These consortia collect detailed clinical variables from hospitals to populate a central registry, allowing benchmarking and comparisons of care and outcomes. As the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded in Southeast Michigan, several consortia came together to focus data collection on patients hospitalised with COVID-19.

Using a well-established data collection strategy, we examined variations in clinical care processes, treatment approaches and clinical outcomes across Michigan hospitals.

Methods

A retrospective cohort design was used. Data were collected from medical records of patients discharged between 16 March 2020 and 11 May 2020 from 1 of 32 Michigan hospitals who participated in collaborative quality initiatives sponsored by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and Blue Care Network. Trained abstractors at each hospital identified adult patients >18 years of age who underwent testing for COVID-19 via reverse-transcriptase PCR, including both positive cases and persons under investigation (PUIs) who eventually had a negative test. Abstractors were asked to abstract as many eligible cases as possible for their hospital. Demographic data (age, gender, race, ethnicity and payor) and in-hospital mortality were collected for all confirmed and PUI cases. A sample of COVID-19-positive cases from each hospital was selected for detailed abstraction. Positive cases were sorted by day of admission (eg, Monday–Sunday) and, for each day, a pseudo-random number (minute of hospital discharge) was used to select patients for detailed abstraction. Patients who were pregnant, transitioned to hospice within 3 hours of hospital admission or discharged against medical advice were excluded. All data were entered into a registry (Mi-COVID19) using a structured data collection template. Of the 92 non-critical access, non-federal hospitals in Michigan, data from 32 hospitals (34.8%) were included in the sample. Included hospitals are diverse in terms of size, teaching status and ownership structure (online supplemental appendix 1).

bmjopen-2020-044921supp001.pdf (108.4KB, pdf)

Patient characteristics including comorbidities, home medications, presenting symptoms and risk factors for COVID-19 (eg, exposure to sick contacts and healthcare workers) were collected. Clinical data during hospitalisation including location of care (ward vs intensive care unit (ICU), a ‘cohorted’ COVID-19 only unit), vital signs, body mass index, laboratory and radiology findings and therapeutics were abstracted. Organ supports such as mechanical ventilation and other respiratory support, vasopressor use and renal replacement therapy (continuous renal replacement therapy and intermittent haemodialysis were also collected.

The primary outcomes of interest included hospital mortality, receipt of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and occurrence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE) (based on positive imaging findings or initiation of empiric therapy for presumed thrombosis). In addition, we performed prespecified exploratory analyses in hospitals with at least 25 detailed abstractions (n=14 hospitals) to examine variation in patient characteristics, management and outcomes. Specifically, we assessed variation in use of COVID-19-specific treatments (defined as hydroxychloroquine, combination hydroxychloroquine plus azithromycin, vitamin C (oral or intravenous), interleukin (IL)-6 inhibitors or remdesivir), antibiotic therapy, use of organ support (eg, use of vasopressors, mechanical ventilation and CPR), occurrence of venous thrombosis and in-hospital mortality.

Descriptive statistics (eg, mean, median and proportion) with measures of dispersion (eg, SE and IQR) were used to summarise data. Data that were not documented in medical records (eg, values of certain laboratory tests) were reported as missing. Pairwise comparisons were made using t-tests for continuous data and χ2 tests for categorical data, respectively. Differences across hospitals were tested using the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and Pearson χ2 test for categorical variables. All statistical tests were two-sided with p<0.05 considered statistically significant. It was not appropriate or possible to involve patients or the public in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of our research.

Patient and public involvement

Patients receiving care at a participating hospital were included in the study.

Data availability

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.

Results

Demographic data

Demographic-only data from 1593 COVID-19-positive and 1259 PUI discharges from 32 Michigan hospitals were collected. PUIs had a median age of 64.4 years; 52.6% were male; and 32.0% were black. COVID-19-positive patients had similar age and gender as PUIs (63.9 years and 52.1% male, respectively) but were more commonly black (57.1% vs 32.0%, p<0.01). In the demographic-only cohort, 398 (25.0%) COVID-19-positive patients died during hospitalisation.

Detailed data were abstracted on 1024 (64.3%) randomly selected COVID-19-positive patients. The most prevalent comorbidities were hypertension (65.4%), diabetes (36.8%), cardiovascular disease (26.0%) and chronic kidney disease (23.3%); 14.9% of the patients had no comorbidities. Though 12.8% of patients had a diagnosis of asthma and 11.2% had a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, prehospital use of inhaled steroids, long-acting beta agonists and long-acting antimuscarinic agents was low at 4.2%, 2.9% and 0.5%, respectively. Current smoking or vaping was uncommon, but 27.3% were former smokers, and 35.8% reported former vaping. A total of 115 (11.3%) patients were on immunosuppressive medications prior to hospitalisation, including 62 (6.1%) who were on oral steroids. Essential workers comprised 12.8% of the cohort, including healthcare workers (7.0%) and service workers (5.8%, eg, postal, food service and transportation). Prior to admission, 16.1% of patients resided in congregated living facilities, including nursing homes and homeless shelters (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of COVID-19-positive patients (n=1024)

| Residence prior to hospitalisation, n (%) | |

| Home | 824 (80.5) |

| Congregated living facility* | 165 (16.1) |

| Subacute rehabilitation facility | 9 (0.9) |

| Unknown | 18 (1.8) |

| Admission location, n (%) | |

| Emergency department | 951 (92.9) |

| Transfer from another hospital | 60 (5.9) |

| Direct admission | 7 (0.7) |

| Median age (years) (IQR) | 63.3 (50.9–74.4) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 533 (52.1) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Black | 526 (51.4) |

| White | 390 (38.1) |

| Unknown | 45 (4.4) |

| Asian | 30 (2.9) |

| Other | 26 (2.5) |

| Native | 4 (0.4) |

| Islander | 3 (0.3) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 873 (85.3) |

| Hispanic | 30 (2.9) |

| Unknown | 117 (11.4) |

| Insurance, n (%) | |

| Medicare | 497 (48.5) |

| Commercial | 251 (24.5) |

| Medicaid | 128 (12.5) |

| Self-pay | 29 (2.8%) |

| Other† | 117 (11.4) |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 30.6 (25.9–37.1) |

| Smoking history, n (%) | |

| Never | 615 (60.2) |

| Former | 279 (27.3) |

| Current | 61 (6.0) |

| Unknown | 65 (6.4) |

| Vaping history, n (%) | |

| Never | 645 (63.2) |

| Former | 366 (35.8) |

| Current | 6 (0.6) |

| Unknown | 3 (0.3) |

| Coexisting disorder, n (%) | |

| Hypertension | 670 (65.4) |

| Diabetes | 377 (36.8) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 266 (26.0) |

| Moderate/severe kidney disease | 239 (23.3) |

| Asthma | 132 (12.9) |

| CHF/cardiomyopathy | 131 (12.8) |

| Dementia | 123 (12.0) |

| COPD | 115 (11.2) |

| Cerebrovascular disease/paraplegia | 97 (9.5) |

| Cancer‡ | 77 (7.5) |

| Peripheral vascular disorders | 41 (4.0) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease (non-asthma/COPD) | 35 (3.4) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 29 (2.8) |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 10 (1.0) |

| HIV/AIDS | 7 (0.7) |

| Organ transplant | 8 (0.8) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 8 (0.8) |

| No reported comorbidities | 152 (14.9) |

| Home medications | |

| ACE inhibitors | 180 (17.6) |

| Steroids/immunosuppressive therapy | 115 (11.3) |

| ARBs | 136 (13.3) |

| NSAIDs | 182 (17.8) |

| Statins | 378 (37.0) |

| Beta blockers | 298 (29.2) |

| Anticoagulants | 149 (14.6) |

| Oral steroids§ | 62 (6.1) |

| Inhaled steroids | 43 (4.2) |

| Inhaled long-acting beta agonist | 30 (2.9) |

| Inhaled long-acting anticholinergic | 5 (0.5) |

| Home oxygen therapy | 36 (3.5) |

| Duration of symptoms before admission (days), median (IQR) | 6 (3–9) |

| Respiratory symptoms, n (%) | |

| Cough (new or worsening) | 751 (73.3) |

| Fever, n (%) | 735 (71.8) |

| Fever (99.0°F–100.4°F) | 151 (14.7) |

| Fever (>100.4°F) | 390 (38.1) |

| Subjective fever | 194 (18.9) |

| Dyspnoea/shortness of breath | 739 (72.2) |

| Nausea/vomiting or diarrhoea | 403 (39.4) |

| Fatigue | 361 (35.3) |

| Myalgias | 264 (25.8) |

| Weakness | 253 (24.7) |

| Sputum production | 146 (14.3) |

| Altered mental status | 144 (14.1) |

| Non-pleuritic chest pain | 100 (9.8) |

| Generalised malaise | 91 (8.9) |

| Rhinorrhoea | 75 (7.3) |

| Pleuritic chest pain | 75 (7.3) |

| No reported symptoms | 14 (1.4) |

| Sick contacts, n (%) | 381 (37.2) |

| Known COVID-19 positive | 244 (23.8) |

| Unknown COVID-19 status | 236 (23.0) |

| Healthcare worker, n (%) | 72 (7.0) |

| Service worker, n (%)¶ | 59 (5.8) |

| Initial location of admission, n (%) | |

| General medical/surgical ward | 608 (59.5) |

| ICU | 138 (13.5) |

| Step-down unit | 160 (15.7) |

| Observation unit | 115 (11.3) |

| Missing/uknown | 3 (0.3) |

| Admitted to COVID-19-specific (ie, cohorted) unit | 419 (40.9) |

| Advanced directives on admission | |

| DNR/DNI | 64 (6.3) |

| No CPR (intubation OK) | 19 (1.9) |

| No intubation (CPR OK) | 3 (0.3) |

*Includes assisted living, group home, skilled nursing facility, homeless shelters, correctional facilities, community living and inpatient psychiatric facilities.

† Includes other payers, Michigan, out-of-state and government.

‡ Includes leukaemia, lymphoma, haematological cancer and any malignancy.

§ Includes oral prednisone, prednisolone, hydrocortisone and dexamethasone.

¶ Service workers include food service, transportation, postal/delivery and other related fields.

ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; DNI, do not intubate; DNR, do not resuscitate; ICU, intensive care unit; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Clinical presentation and initial evaluation

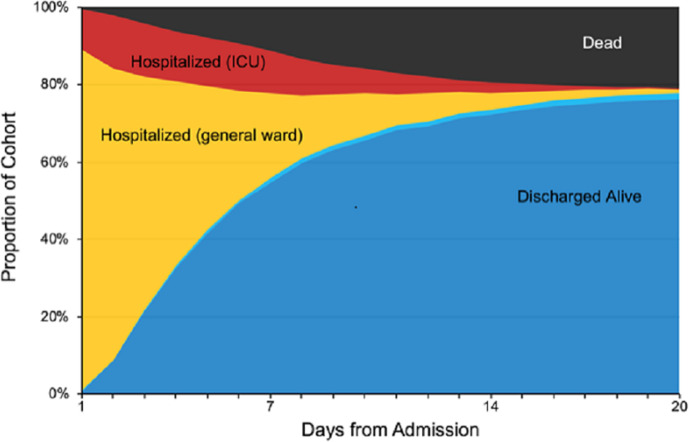

In the detailed abstraction cohort (n=1024), median duration of symptoms prior to hospitalisation was 6 days (IQR 3–9). The most common presenting symptoms were cough (73.3%), fever (71.8%) and shortness of breath (72.2%); only 8% of patients did not report one of these three complaints (table 1). Gastrointestinal symptoms including nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea occurred in 39.4% of patients. Over a third of patients (37.2%) reported sick contacts at the time of admission, and 23.8% reported contact with a patient known to have COVID-19. The location of diagnostic testing for COVID-19 varied: 67.5% of patients were tested in hospital laboratories, 23.2% in commercial laboratories and 8.0% in the state laboratory. Patients were most commonly admitted to a general medical/surgical ward (59.5%), but 15.7% were admitted to intermediate care; 13.5% were admitted directly to the ICU; and 11.3% were admitted to an observation unit (figure 1). A total of 419 (40.9%) of patients were admitted to a cohorted (COVID-19 only) unit. At admission, 6.3% of patients had do not resuscitate/do not intubate orders, which increased to 13.8% by discharge.

Figure 1.

Depiction of the proportion of the N=1024 patient cohort who are hospitalised on general care/ward (yellow), hospitalised in ICU (red), discharged alive (blue), transferred to a new hospital (light blue) and deceased over time to day 20 of hospital admission. ICU, intensive care unit.

Common laboratory testing on admission included white blood cell count (93.7%), absolute lymphocyte count (75.8%), troponin (57.4%), lactate (57.2%), C reactive protein (CRP) (44.9%) and procalcitonin (42.4%) (missingness by laboratory test are reported in the online supplemental e-appendix 2). Among those with available laboratory data, patients who received ICU treatment had higher levels of inflammatory markers at admission including d-dimer (2.88 mg/L vs 1.65 mg/L), ferritin (872 ng/mL vs 559 ng/mL), CRP (24.3 mg/dL vs 13.8 mg/dL) and lactate dehydrogenase (476 U/L vs 346 U/L) (table 2). Chest imaging (X-ray or CT) was performed in 528 (51.6%) patients within 1 day of admission and was more common in ICU than general care patients (59.9% vs 49.1%, p=0.004). ICU patients were more likely to have radiographic abnormalities on presentation. Viral respiratory panels, blood cultures and sputum cultures were collected in 722 (51.0%) patients but were positive in only 48 (4.7%) patients; 9.5% of ICU patients vs 3.3% of general care patients had a viral or bacterial pathogen identified (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Clinical and laboratory data in COVID-19-positive patients by ICU status (n=1024)

| Ever ICU (n=232) |

General ward (n=792) |

P value | |

| Vital signs on day of hospital admission, n (%) | |||

| Fever (>100.4°F) | 95 (40.9) | 295 (37.2) | 0.3073 |

| Hypoxia/new or escalated O2 requirement | 142 (61.2) | 257 (32.4) | <0.0001 |

| Supplemental oxygen use | 96 (41.4) | 145 (18.3) | <0.0001 |

| Respiratory rate>20 breaths/min | 139 (59.9) | 306 (38.6) | <0.0001 |

| Heart rate>100 beats/min | 99 (42.7) | 321 (40.5) | 0.5596 |

| Systolic blood pressure<100 mm Hg | 27 (11.6) | 45 (5.7) | 0.0018 |

| Day 1 laboratory measures, median (IQR) | |||

| Haemoglobin | 13.2 (11.4–14.7) | 13.2 (12.0–14.6) | 0.4573 |

| White blood cell count (K/μL) | 7.3 (5.5–9.7) | 6.5 (4.8–8.4) | <0.0001 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count (K/μL) | 0.80 (0.60–1.20) | 1.00 (0.70–1.30) | 0.3440 |

| Platelet count (K/μL) | 197 (149–256) | 204 (159–268) | 0.4875 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 32.0 (20.0–60.0) | 27.0 (18.0–41.0) | 0.2228 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 1.6 (1.2–2.5) | 1.4 (1.0–1.8) | 0.0010 |

| Troponin (pg/mL) | 9 (0–38) | 0 (0–12) | 0.5872 |

| Brain natriuretic peptide (pg/mL) | 79 (34–236) | 49 (18–157) | 0.0088 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL) | 0.30 (0.17–0.94) | 0.12 (0.06–0.29) | 0.5054 |

| D-dimer (mg/L) | 2.88 (1.19–35.00) | 1.65 (0.59–368.00) | 0.8240 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 872 (379–1531) | 559 (237–1019) | 0.1074 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 24.3 (12.0–107.1) | 13.8 (5.8–66.2) | 0.0031 |

| LDH (IU/L) | 476 (337–668) | 346 (254–455) | <0.0001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.3 (1.0–2.0) | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | 0.5736 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | 0.5 (0.4–0.8) | 0.7147 |

| Respiratory viral panel positive for non-COVID-19 respiratory virus, n (%) | 2 (0.9) | 7 (0.9) | 0.9443 |

| Positive blood culture within 1 day of admission, n (%) | 7 (3.0) | 9 (1.1) | 0.0422 |

| Positive respiratory culture within 1 day of admission, n (%) | 4 (1.7) | 4 (0.5) | 0.0636 |

| Any chest imaging*, n (%) | 139 (59.9) | 389 (49.1) | 0.0038 |

| Chest X-ray, n (%) | 118 (50.9) | 322 (40.7) | 0.0058 |

| Chest CT, n (%) | 34 (14.7) | 106 (13.4) | 0.6201 |

| Imaging findings, n (%) | |||

| Pneumonia | 61 (26.3) | 100 (12.6) | <0.0001 |

| Non-specified opacities/air-space disease | 84 (36.2) | 161 (20.3) | <0.0001 |

| Pleural effusion | 32 (13.8) | 37 (4.7) | <0.0001 |

| Normal/no abnormalities | 5 (2.2) | 30 (3.8) | 0.2287 |

| Pulmonary oedema | 25 (10.8) | 29 (3.7) | <0.0001 |

| CT with ground-glass infiltrates | 14 (6.0) | 58 (7.3) | 0.4995 |

| Respiratory support on day of admission, n (%) | |||

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 46 (19.8) | 2 (0.3) | <0.0001 |

| Non-invasive positive pressure | 5 (2.2) | 2 (0.3) | 0.0020 |

| HHFNC | 5 (2.2) | 5 (2.2) | 0.1905 |

| Oxygen mask (>40% FiO2) | 17 (7.3) | 20 (2.6) | 0.0006 |

| Nasal cannula oxygen, 1–6 L | 76 (32.8) | 261 (33.0) | 0.9555 |

| No supplemental oxygen | 83 (8.1) | 502 (49.0) | <0.0001 |

| Treatments during hospitalisation, n (%) | |||

| COVID-19-specific treatment(s), n (%) | |||

| Hydroxychloroquine | 154 (66.4) | 364 (46.0) | <0.0001 |

| Hydroxychloroquine+azithromycin | 112 (48.3) | 260 (32.8) | <0.0001 |

| Vitamin C (PO or intravenous) | 35 (15.1) | 68 (8.6) | 0.0038 |

| Remdesivir | 7 (3.0) | 10 (1.3) | 0.0658 |

| IL-6 receptor inhibitor | 27 (11.6) | . (%) | <0.0001 |

| Corticosteroids,†† n (%) | 79 (34.1) | 143 (18.1) | <0.0001 |

| Antibiotics, n (%) | 213 (91.8) | 558 (70.5) | <0.0001 |

| Azithromycin | 149 (64.2) | 415 (52.4) | 0.0014 |

| Ceftriaxone | 124 (53.4) | 345 (43.6%) | 0.0079 |

| Cefepime | 90 (38.8) | 79 (10.0) | <0.0001 |

| Doxycycline | 37 (15.9) | 111 (14.0) | 0.4615 |

| Vancomycin | 115 (49.6) | 106 (13.4) | <0.0001 |

| Linezolid | 12 (5.2) | 8 (1.0) | <0.0001 |

| Antipseudomonals‡ | 123 (53.0) | 115 (14.5) | <0.0001 |

| Antivirals,§§ n (%) | 1 (0.4) | 13 (1.6) | 0.1626 |

| Enrolled in clinical trial | 10 (4.3) | 12 (1.5) | 0.0098 |

*Includes chest imaging results 7 days before hospital encounter.

†Hydrocortisone, methylprednisolone, prednisolone or prednisone.

‡Cefepime, gentamicin, imipenem, meropenem, piperacillin–tazobactam, ceftazadime, aztreonam or tobramycin.

§Non-remdesivir antivirals including oseltamivir, lopinavir/ritonavir, ribavirin, others.

ALT, alanine transaminase; CRP, C reactive protein; FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; HHFNC, heated high-flow nasal cannula; ICU, intensive care unit; IL, interleukin; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

bmjopen-2020-044921supp002.pdf (73.9KB, pdf)

Critical care treatment

Overall, 232 patients (22.7%) were treated in an ICU, including 138 (13.5%) who were admitted directly to an ICU and 94 (9.2%) who were transferred to ICU within a median of 2 days following admission. Median length of ICU stay was 6 days (IQR 3–9), which was similar in survivors versus non-survivors (5 vs 6 days, p=0.790). Among 1024 patients with detailed abstraction, the maximum respiratory support received was invasive mechanical ventilation in 161 patients (15.7%), non-invasive positive pressure ventilation in 15 (1.5%), heated high-flow nasal cannula (HHFNC) in 60 (5.9%), oxygen mask (>40% fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) or >6 L/min) in 88 (8.6%) and nasal cannula oxygen (1–6 L/min) in 441 (43.1%) (table 3). A total of 259 (25.3%) patients had no respiratory support or oxygen therapy during hospitalisation. Among 78 patients initiated on HHFNC, 13 (16.7%) progressed to invasive mechanical ventilation. Among 25 patients initiated on NIPPV, 10 (40.0%) progressed to invasive mechanical ventilation. An additional 12 patients and 2 patients, respectively, used HHFNC and NIPPV after extubation.

Table 3.

Organ support for COVID-19-positive patients by discharge status (n=1024)

| All patients (n=1024) |

Discharged alive (n=805) |

Died in hospital (n=219) |

|

| Treated in an ICU, n (%) | 232 (22.7) | 101 (12.5) | 131 (59.8) |

| Respiratory support ever received, n (%)* | |||

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 161 (15.7) | 47 (5.8) | 114 (52.1) |

| Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation | 27 (2.6) | 10 (1.2) | 17 (7.8) |

| HHFNC | 90 (8.8) | 57 (7.1) | 33 (15.1) |

| Oxygen mask (>40% FiO2) | 159 (15.5) | 76 (9.4) | 83 (37.9) |

| Maximum respiratory support received, n (%)† | |||

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 161 (15.7) | 47 (5.8) | 114 (52.1) |

| Non-invasive positive pressure | 15 (1.5) | 6 (0.7) | 9 (4.1) |

| HHFNC | 60 (5.9) | 40 (5.0) | 20 (9.1) |

| Oxygen mask (>40% FiO2) | 88 (8.6) | 48 (6.0) | 40 (18.3) |

| Nasal canula oxygen, 1–6 L/min | 441 (43.1) | 415 (51.6) | 26 (11.9) |

| No respiratory support | 259 (25.3) | 249 (30.9) | 10 (4.6) |

| Max FiO2 received, n (%) | |||

| 91%–100% | 126 (12.3) | 34 (4.2) | 92 (42) |

| 81%–90% | 30 (2.9) | 13 (1.6) | 17 (7.8) |

| 71%–80% | 86 (8.4) | 42 (5.2) | 44 (20.1) |

| 61%–70% | 16 (1.6) | 9 (1.1) | 7 (3.2) |

| 51%–60% | 26 (2.5) | 14 (1.7) | 12 (5.5) |

| 41%–50% | 24 (2.3) | 20 (2.5) | 4 (1.8) |

| 31%–40% | 170 (16.6) | 144 (17.9) | 26 (11.9) |

| 21%–30% | 287 (28) | 280 (34.8) | 7 (3.2) |

| Non-respiratory organ support received, n (%) | |||

| Vasopressor | 141 (13.8) | 35 (4.3) | 106 (48.4) |

| Any dialysis‡ | 53 (5.2) | 17 (2.1) | 36 (16.4) |

| CRRT only | 17 (1.7) | 1 (0.1) | 16 (7.3) |

| iHD only | 28 (2.7) | 15 (1.9) | 13 (5.9) |

| CPR | 41 (4.0) | 1 (0.1) | 40 (18.3) |

*Represents any use of respiratory support. Numbers are greater than 100% as one patient may have received multiple treatments.

†Represents the highest level of respiratory support a patient has received during hospitalisation.

‡Includes iHD, dialysis and ultrafiltration.

CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; HHFNC, heated high-flow nasal cannula; ICU, intensive care unit; iHD, intermittent haemodialysis.

On initiation of mechanical ventilation, patients were predominantly treated with a volume control mode (75%), with high FiO2 (≥80% in 49.1% of ventilated patients), and modest tidal volumes (median tidal volume 7.0 mL/kg predicted body weight, IQR 6.2–8.0). The median duration of mechanical ventilation was 6 days (IQR 3–8 days). Prone positioning was documented in 18 patients, pulmonary vasodilators in 2 patients and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in 2 patients. CPR was administered to 41 patients (4.0%), with only 1 patient surviving to hospital discharge.

Vasopressors were used in 141 patients (13.8%); dialysis was performed in 53 (5.2%) and corticosteroids in 222 (21.7%) patients. A total of 771 (75.3%) patients received broad-spectrum antibiotics, with use being more common in the ICU than in general wards (91.8% vs 70.5%, p<0.001).

COVID-19-specific therapies

A total of 747 (72.9%) patients were treated with therapies targeting COVID-19, or the body’s response to COVID-19, most commonly hydroxychloroquine (51%), hydroxychloroquine plus azithromycin (36%) and vitamin C (10%). Treatment with IL-6 inhibitors and remdesivir was infrequent (27 and 17 patients, respectively). Use of COVID-19 treatments was more common in ICU than in general care patients (88% vs 69%, p<0.001). No patients in our sample received convalescent plasma. The proportion of patients treated with COVID-19-specific therapies decreased over time from 78.1% of patients admitted during 8–31 March to 65.0% of patients admitted during 1 April–11 May (p<0.001). Only 21 (2.0%) patients were enrolled in a clinical trial (table 2).

Clinical outcomes

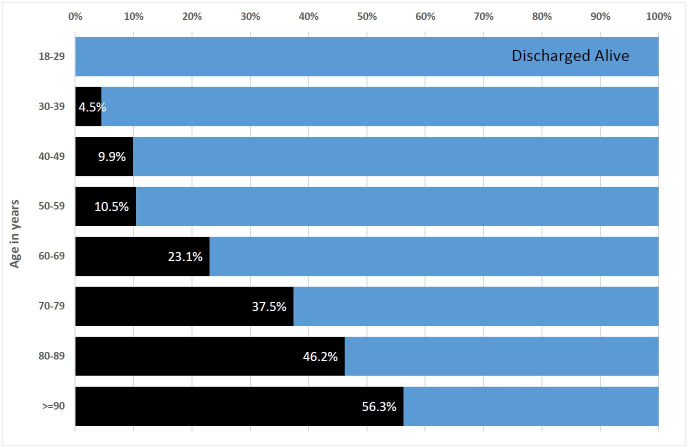

The in-hospital mortality rate for the full cohort of COVID-19-positive patients (demographic plus detailed abstractions) was 25.0%. Mortality varied by decade of age, ranging from 4.5% among patients aged 30–39% to 37.5% in patients aged 70–79 years (figure 2). Among 219 decedents with detailed abstraction, 134 (61.5%) died following ICU treatment and 114 (52.1%) died after undergoing mechanical ventilation. Of 219 decedents, 40 (18.3%) received CPR, and 91 (41.6%) were transitioned to comfort care prior to death. The most common causes of death were refractory hypoxaemia (29.4%), cardiac arrhythmia (15.9%) and refractory shock (10.7%). Venous thromboembolism occurred in 32 (3.1%) patients, of which 9 experienced proximal lower-extremity DVT; 21 experienced PE; and 2 experienced both DVT and PE.

Figure 2.

Graph depicting the proportion of the demographic cohort (n=1593) who died in the hospital by decade of age. Black shading indicates death, whereas blue shading indicates being discharged alive.

Among the 805 patients that survived to hospital discharge, 86% were discharged home and 8% were discharged to a skilled nursing facility or rehabilitation centre. Only one patient (0.1%) was discharged to the Detroit field hospital (table 3).

Variation across hospitals

Among 14 hospitals with at least 25 detailed abstractions, substantial variation in demographics, illness severity, care processes, treatments and outcomes of COVID-19-positive patients was observed (table 4). The proportion of patients over 65 years of age ranged from 30.2% to 65.5%, while the proportion of black patients ranged from 0% to 94.6%. Similarly, the proportion of patients admitted directly to an ICU ranged from 0% to 43.8%, while the proportion of patients who were transferred to an ICU after admission ranged from 0% to 24.1%. Treatment in cohorted units ranged from 0% to 100%. Mechanical ventilation on admission ranged from 0% to 12.8%, while use of vasopressors on admission ranged from 0% to 14.8% across hospitals. Critical illness on presentation (defined as admission to an ICU with receipt of vasopressors or mechanical ventilation on admission) varied from 0% to 7.7%.

Table 4.

Variation in clinical care and outcomes in COVID-19-positive patients across hospitals

| Range across hospitals | P value* | |||||||

| Min | 10th Pctl | 25th Pctl | Median | 75th Pctl | 90th Pctl | Max | ||

| Patient characteristics | ||||||||

| Age >65 years (%) | 30.2 | 35.3 | 39.6 | 51.3 | 56.8 | 64.4 | 65.5 | <0.0001 |

| Black (%) | 0.0 | 17.7 | 29.7 | 46.2 | 76.4 | 93.7 | 94.6 | <0.0001 |

| Male (%) | 39.2 | 45.6 | 47.1 | 53.0 | 56.8 | 72.4 | 73.8 | 0.07 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, median | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.01 |

| BMI, median | 24.3 | 28.4 | 29.5 | 31.1 | 33.3 | 36.5 | 36.9 | 0.09 |

| Median age (years) | 39.0 | 46.5 | 60.8 | 62.4 | 66.4 | 73.5 | 76.0 | <0.0001 |

| Admission information (%) | ||||||||

| Hospital-to-hospital transfer | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.00 | 2.8 | 10.7 | 20.9 | <0.0001 |

| Admitted directly to ICU | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 6.15 | 14.8 | 20.5 | 43.8 | <0.0001 |

| Transferred from floor to ICU | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8.4 | 17.6 | 18.8 | 24.1 | 0.09 |

| Admitted to a cohorted unit | 0.0 | 2.1 | 18.6 | 67.9 | 85.71 | 96.3 | 97.1 | <0.0001 |

| Severe illness on presentation† | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 3.7 | 7.1 | 7.7 | 0.09 |

| Vasopressor use on day 1 | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.1 | 6.4 | 10.3 | 14.8 | 0.04 |

| Mechanical ventilation on day 1 | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.51 | 8.6 | 11.1 | 12.8 | 0.03 |

| Treatment (%) | ||||||||

| Treated in a cohorted unit | 0.0 | 0.00 | 6.3 | 57.1 | 90.9 | 100.0 | 100.0 | <0.0001 |

| Treated in an ICU | 4.2 | 5.4 | 14.0 | 19.1 | 31.0 | 38.5 | 62.5 | <0.0001 |

| COVID-19-specific treatment | 32.4 | 57.1 | 69.2 | 76.4 | 81.4 | 90.2 | 96.3 | <0.0001 |

| Concurrent antibiotic and COVID-19-specific treatment(s) | 24.3 | 42.9 | 59.4 | 69.8 | 76.7 | 84.3 | 96.3 | <0.0001 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 13.5 | 31.4 | 42.3 | 59.7 | 65.5 | 81.5 | 82.4 | <0.0001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 2.1 | 2.7 | 6.4 | 10.9 | 31.0 | 38.5 | 40.6 | <0.0001 |

| Vasopressors | 2.2 | 2.9 | 7.0 | 12.1 | 25.0 | 32.1 | 32.5 | <0.0001 |

| CPR before death | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8.3 | 14.3 | 33.3 | 40.0 | 66.7 | 0.0102 |

| Outcomes (%) | ||||||||

| Days of mechanical ventilation, median‡ | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 9.0 | 0.01 |

| Length of stay, median | 2.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 4.5 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 8.5 | <0.0001 |

| ICU length of stay, median§ | 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.5 | 5.0 | 6.5 | 7.5 | 9.5 | 0.01 |

| DVT | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.1 | 3.5 | 7.1 | 0.05 |

| VTE | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 5.2 | 6.3 | 10.7 | 0.20 |

| PE | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 3.9 | 6.3 | 7.1 | 0.72 |

| Discharge status (%) | ||||||||

| Death | 7.9 | 8.3 | 14.6 | 21.3 | 31.0 | 41.4 | 45.7 | <0.0001 |

| Transferred to another hospital | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.6 | 2.7 | 5.1 | 0.07 |

| Discharged home | 42.3 | 48.2 | 62.1 | 67.5 | 72.9 | 80.0 | 82.5 | <0.0001 |

*Differences across hospitals were tested using the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and Pearson χ2 test for categorical variables.

†Defined as admission to ICU on day 1 of hospitalisation and treatment with both mechanical ventilation and vasopressors.

‡For patients ever on mechanical ventilation.

§For patients ever in ICU.

¶Variables marked with asterisks represent variation from the demographic cohort.

BMI, body mass index; ICU, intensive care unit; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; VTE, venous thromboembolism; PE, pulmonary embolism

Of the total number of patients, 72.9% received at least one COVID-19-specific therapy (eg, hydroxychloroquine, hydroxychloroquine plus azithromycin, IL-6 inhibitor and antiviral therapy), but use varied from 32% to 96.3% across sites. Similarly, 65% of patients received concurrent antibiotics and COVID-19-specific treatment during hospitalisation, with frequency varying from 50% to 100% in ICU patients versus 17% to 95% in general care patients.

Mortality across hospitals varied from 7.9% to 45.7% of patients, and rates of CPR before death ranged from 0% to 66.7%. Finally, rates of VTE also varied, occurring in 0%–11% of patients across hospitals.

Discussion

While reports of patients with COVID-19 from New York, Washington and California exist,7–9 this is the first multicentre study to examine epidemiology, treatment and outcomes of COVID-19 hospitalisations in Michigan. Also, in contrast to prior multihospital US cohorts, the Mi-COVID19 registry includes a large sample of patients treated at a diverse set of 32 academic and community hospitals.

The demographics of our cohort differ from those of other cohorts. First, patients with confirmed COVID-19 in Michigan are disproportionally black (over half of our cohort). This is in contrast to 32% of PUIs—indicating that the predominance of black patients with COVID-19 is not a reflection of local demographics, but rather a disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on black patients. Second, in contrast to prior studies,1 7 10 our cohort was nearly 50:50 male:female, rather than male dominant. The reasons for this difference are unclear.

Consistent with prior reports, the main presenting symptoms were cough, dyspnoea and fever. Similar to other studies,11 a substantial proportion of patients had multiple comorbidities, but notably, 15% of our cohort had no known medical problems.12 We found that a substantial proportion of patients reported contact with a known COVID-19-positive patient prior to developing symptoms. These findings mirror those of a study from Shenzen, China, where contacts of those with disease experienced a significantly higher rate of infection than the general public.13 Additionally, patients underwent COVID-19 testing through a number of venues including hospital, commercial and state-run laboratories, illustrating the myriad ways in which diagnosis was obtained early in the outbreak when testing was limited.14 Although only 14% of the sample was admitted directly to an ICU, an additional 9% was transferred to an ICU later in hospitalisation. Hospital mortality in cases with detailed abstractions was 21% but increased with age, consistent with prior studies.15

A key finding of our study is that a majority of patients hospitalised for COVID-19 were treated with therapies intended to mitigate SARS-CoV-2 viral replication or the body’s immune response. More than half of patients were treated with hydroxychloroquine, and an additional 6% were treated with antivirals or immune modulating agents. Experts have increasingly questioned the use of unproven COVID-19 therapies outside of a clinical trial16 and have argued that supportive care and trial enrolment are the best options until data regarding efficacy of therapies accrue.17 18 Accumulating observational and trial data now suggest no benefit from hydroxychloroquine,19–21 and concerns regarding harm from empiric use remain.22 Unfortunately, only 2% of our sample was enrolled in clinical trials. The high rate of experimental COVID-19 therapies outside empiric studies represents a lost opportunity for learning. It is also emblematic of the strong desire—particularly early in the pandemic—to use therapies with a theoretical potential to target the virus even though improved survival from critical illness is largely attributed to improvements in supportive care.23 Notably, we still do not have targeted therapies for sepsis or acute respiratory distress syndrome, which are the major mechanisms by which patients die from COVID-19 infection.

Another strength of our study is the variation in clinical presentation and outcomes we observed across a heterogeneous sample of hospitals. Use of COVID-19-specific treatments, corticosteroids and antibiotics varied markedly across hospitals. While we were unable to ascertain reasons for such variation, we anecdotally observed that practice evolved across hospitals over time. For example, at some Michigan hospitals, routine use of hydroxychloroquine was common in the first few weeks of the pandemic but curbed as trial data became available. In contrast, use of hydroxychloroquine continues to be encouraged at other hospitals even today.24 While it is unclear if these practice changes influenced outcomes, future studies exploring the rationale and impact of these changes on patients will be valuable.

Our findings provide corroboratory information regarding the first COVID-19 wave within Michigan. For example, in a single-centre retrospective study, Imam and colleagues found that advanced age and increasing number of comorbidities were independent predictors of in-hospital mortality in hospitalised Michigan patients, just as we did in our cohort.25 Similarly, in two national population-level studies led by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, individuals over 65 years of age and those with ≥3 comorbidities experienced greater risk of hospitalisation and adverse outcomes, again consistent with our findings.26 27 Our findings are also similar to others regarding disparities in COVID-19 care and outcomes, especially among minority populations.28 Despite these findings, our study also differs from other national studies in important ways. For example, we observed a low rate of readmissions in our cohort. In contrast, Donnelly et al using Veterans Health Affairs data reported a readmission rate of 19.9% at 60 days.29 While the reasons for this discrepancy are unclear, it is possible that practice pattern differences including variation in threshold for readmission and differences in patient characteristics may account for these discrepancies. As we begin to understand and manage the chronic sequelae of acute COVID-19,30 studies understanding reasons for these pattern differences would be important. Another important difference lies in the use of therapeutics targeting COVID-19. For example, reports from New York City and Seattle show greater rates of use of remdesivir and IL-6 inhibitors.8 31 Whether these differences were due to practice variation (which occurred widely in the early US waves of COVID-19) versus lack of access to therapeutics which was also reported is unclear.

Our study has limitations. First, given the observational nature of the study, rationales for treatment or management decisions cannot be determined. Second, because our sampling frame included patients who were discharged or deceased, our findings may be biased as patients who remain hospitalised may not be included in our cohort (potentially explaining lower duration of mechanical ventilation and hospital stay). However, COVID-19 hospitalisations in Southeastern Michigan have been declining since mid-April—limiting the degree of bias from exclusion of patients still in the hospital. Third, while variation in care was observed, the implications of such variability on clinical outcomes are unknown. Nevertheless, given that therapeutic modalities are scarce and not without risks, reducing variation may improve patient safety and resource use. Fourth, our study depends on available documentation, so symptoms, comorbidities or treatments not documented in the medical record may be omitted. For example, it is possible that the low use of prone positioning observed in our cohort may be due to incomplete documentation of this practice. Finally, we did not collect patient identifiers, so interhospital transfers could be reported as two separate hospitalisations. However, we did collect admission and discharge locations, and only 6% of the cohort was transferred from another hospital.

Our study also has strengths. First, ours is the first multihospital study to examine clinical aspects related to COVID-19 in Michigan. Through a rigorous data collection structure including a well-defined sampling strategy and trained data abstractors, we provide novel and detailed insights into clinical care during the pandemic. Second, we were able to examine variation across sites, finding substantial differences in clinical care and outcomes across hospitals. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine differences in these important care processes, treatment approaches and outcomes across sites. Third, we report a high rate of use of non-evidence-based therapies for treating COVID-19. This finding has significant safety, economic and policy implications for the most critically ill subsets in the hospital. Finally, data collection for this effort remains ongoing, including longitudinal monitoring of patients after discharge. These data will help shed new light on the post hospital sequelae of COVID-19.

Michigan remains one of the regions most affected by COVID-19. This multicentre study provides granular clinical data regarding patients, care practices and clinical outcomes in the state. The wide variation in observed practices and outcomes suggests caution when interpreting findings from single-centre studies. Our study also demonstrates the value of hospital collaboratives to help inform best practices.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Qisu (Sue) Zhang, MPH; Tawny Czilok, RN, MHI; Liz Vasher, RN; Jessica Southwell, RN, MSN; Danny Nielsen, MS; and Jennifer Horowitz, MA, for help with data analytics and project management. We also thank all the BCBSM Collaborative Quality Initiatives that partnered together on data collection and offered project management/analytics support. Lastly, we are grateful to all of the hospitals who volunteered to be part of MiCOVID-19, including Beaumont-Dearborn, Beaumont-Grosse Pointe, Beaumont- Farmington Hills, Beaumont- Royal Oak, Beaumont- Taylor, Beaumont- Trenton, Beaumont- Troy, Beaumont- Wayne, Bronson Battle Creek, Bronson Methodist, Detroit Medical Center-Detroit Receiving, Detroit Medical Center-Harper Hutzel, Detroit Medical Center-Detroit-Huron Valley Sinai, Henry Ford, Henry Ford Allegiance, Henry Ford Macomb, Henry Ford West Bloomfield, Henry Ford West Wyandotte, Holland Hospital, Hurley Medical Center, Lakeland Hospital, McLaren Flint, McLaren Greater Lansing, McLaren Port Huron, Mercy Health Muskegon, Mercy Health St. Mary's, Metro Health, Michigan Medicine, MidMichigan Alpena, MidMichigan Gratiot, MidMichigan Midland, Munson Medical Center, Oaklawn Hospital, Sinai Grace, Sparrow, St. Joseph Mercy Ann Arbor, St. Joseph Mercy Chelsea, St. Joseph Mercy Livingston, St. Joseph Mercy Oakland, St. Mary Mercy Livonia.

Footnotes

Twitter: @vineet_chopra

Contributors: VC: manuscript planning, interpretation of the data, manuscript drafting/revisions and final approval to be published; SAF, VV, LP, TG, JIMcS, AM and EMcL: manuscript planning, manuscript drafting/revisions and final approval to be published; MOM: data analysis, interpretation of the data and final approval to be published; TK: manuscript planning and final approval to be published; HP: manuscript planning, interpretation of the data, manuscript drafting/revisions and final approval to be published

Funding: Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and Blue Care Network as part of the BCBSM Value Partnerships program.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The study was deemed 'not regulated' by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (HUM 00179611).

References

- 1.Guan WJ, ZY N, Hu Y. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020. (published Online First: 2020/02/29). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med 2020;382:727–33. 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.COVID-19 Dashboard by the center for systems science and engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University. Available: https://coronavirusjhuedu/maphtml [Accessed 20 Apr 2020].

- 4.Centers for disease control cases of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in the US. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html [Accessed 20 Apr 2020].

- 5.Michigan.gov . Coronavirus Resources - Confirmed cases by Jurisdiction. Available: https://www.michigan.gov/coronavirus/0,9753,7-406-98163-520743-,00.html [Accessed 20 Apr 2020].

- 6.Blue cross blue shield collaborative quality initiatives. Available: https://www.bcbsm.com/providers/value-partnerships/collaborative-quality-initiatives.html [Accessed 20 Apr 2020].

- 7.Goyal P, Choi JJ, Pinheiro LC, et al. Clinical characteristics of Covid-19 in New York City. N Engl J Med 2020;382:2372–4. 10.1056/NEJMc2010419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhatraju PK, Ghassemieh BJ, Nichols M, et al. Covid-19 in Critically Ill Patients in the Seattle Region - Case Series. N Engl J Med 2020;382:2012–22. 10.1056/NEJMoa2004500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myers LC, Parodi SM, Escobar GJ, et al. Characteristics of hospitalized adults with COVID-19 in an integrated health care system in California. JAMA 2020;323:2195. 10.1001/jama.2020.7202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy region, Italy. JAMA 2020;323:1574. 10.1001/jama.2020.5394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xie J, Tong Z, Guan X, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients who died of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e205619. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.5619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gold JAW, Wong KK, Szablewski CM, et al. Characteristics and clinical outcomes of adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19 - Georgia, March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:545–50. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6918e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bi Q, Wu Y, Mei S, et al. Epidemiology and transmission of COVID-19 in 391 cases and 1286 of their close contacts in Shenzhen, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2020;20:911–9. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30287-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharfstein JM, Becker SJ, Mello MM. Diagnostic testing for the novel coronavirus. JAMA 2020;323:1437. 10.1001/jama.2020.3864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the new York City area. JAMA 2020;323:2052. 10.1001/jama.2020.6775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhimraj A, Morgan RL, Shumaker AH, et al. Infectious diseases Society of America guidelines on the treatment and management of patients with COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis 2020:ciaa478. 10.1093/cid/ciaa478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rice TW, Janz DR. In defense of evidence-based medicine for the treatment of COVID-19 ARDS. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2020;17:787–9. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202004-325IP [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waterer GW, Rello J, Wunderink RG. COVID-19: first do no harm. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020;201:1324–5. 10.1164/rccm.202004-1153ED [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang W, Cao Z, Han M. Hydroxychloroquine in patients with mainly mild to moderate coronavirus disease 2019: open label, randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2020;369:m1849. 10.1136/bmj.m1849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahévas M, Tran V-T, Roumier M, et al. Clinical efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in patients with covid-19 pneumonia who require oxygen: observational comparative study using routine care data. BMJ 2020;369:m1844. 10.1136/bmj.m1844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenberg ES, Dufort EM, Udo T, et al. Association of treatment with hydroxychloroquine or azithromycin with in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19 in New York state. JAMA 2020;323:2493. 10.1001/jama.2020.8630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bessière F, Roccia H, Delinière A, et al. Assessment of QT intervals in a case series of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection treated with hydroxychloroquine alone or in combination with azithromycin in an intensive care unit. JAMA Cardiol 2020;5:1067. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Angus DC. Optimizing the trade-off between learning and doing in a pandemic. JAMA 2020;323:1895. 10.1001/jama.2020.4984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wells K. Hospitals Vary Treatment for Coronavirus Patients. National Public Radio, 2020. Available: https://www.npr.org/2020/05/18/857727140/hospitals-vary-treatment-for-coronavirus-patients [Accessed 19 May 2020].

- 25.Imam Z, Odish F, Gill I, et al. Older age and comorbidity are independent mortality predictors in a large cohort of 1305 COVID-19 patients in Michigan, United States. J Intern Med 2020;288:469–76. 10.1111/joim.13119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim L, Garg S, O'Halloran A, et al. Risk Factors for Intensive Care Unit Admission and In-hospital Mortality Among Hospitalized Adults Identified through the US Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)-Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (COVID-NET). Clin Infect Dis 2021;72:e206–14. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ko JY, Danielson ML, Town M, et al. Risk Factors for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)-Associated Hospitalization: COVID-19-Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network and Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Clin Infect Dis 2021;72:e695–703. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Price-Haywood EG, Burton J, Fort D, et al. Hospitalization and mortality among black patients and white patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020;382:2534–43. 10.1056/NEJMsa2011686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donnelly JP, Wang XQ, Iwashyna TJ, et al. Readmission and death after initial hospital discharge among patients with COVID-19 in a large multihospital system. JAMA 2021;325:304–6. 10.1001/jama.2020.21465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahase E. Covid-19: What do we know about "long covid"? BMJ 2020;370:m2815. 10.1136/bmj.m2815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the new York City area. JAMA 2020;323:2052–9. 10.1001/jama.2020.6775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-044921supp001.pdf (108.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-044921supp002.pdf (73.9KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.