Abstract

Background

Although achieving histologic remission in ulcerative colitis is established, the incremental benefit of achieving histologic remission in patients with Crohn disease (CD) treated to a target of endoscopic remission is unclear. We evaluated the risk of treatment failure in patients with CD in clinical and endoscopic remission by histologic activity status.

Methods

In a single-center retrospective cohort study, we identified adults with active CD who achieved clinical and endoscopic remission through treatment optimization. We evaluated the risk of treatment failure (composite of clinical flare requiring treatment modification, hospitalization, and/or surgery) in patients who achieved histologic remission vs persistent histologic activity through Cox proportional hazard analysis.

Results

Of 470 patients with active CD, 260 (55%) achieved clinical and endoscopic remission with treatment optimization; 215 patients with histology were included (median age, 33 years; 46% males). Overall, 132 patients (61%) achieved histologic remission. No baseline demographic, disease, or treatment factor was associated with achieving histologic remission. Over a 2-year follow-up, patients with CD in clinical and endoscopic remission who achieved histologic remission experienced a 43% lower risk of treatment failure (1-year cumulative risk: 12.9% vs 18.2%; adjusted hazard ratio, 0.57 [95% confidence interval, 0.35-0.94]) as compared with persistent histologic activity.

Conclusions

Approximately 61% of patients with active CD who achieved clinical and endoscopic remission with treatment optimization simultaneously achieved histologic remission, which was associated with a lower risk of treatment failure. Whether histologic remission should be a treatment target in CD requires evaluation in randomized trials.

Keywords: treat-to-target, biologics, biopsy, IBD

INTRODUCTION

Treatment targets in patients with Crohn disease (CD) have evolved from resolving symptoms to achieving a combination of symptomatic remission (based on patient-reported outcomes) and endoscopic remission, pragmatically defined as the resolution of mucosal ulcers.1 More recently, there has been considerable interest in evaluating histologic remission as a treatment target. Several observational studies have shown that achieving histologic remission may be beneficial in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) who have achieved symptomatic and endoscopic remission.2-4 However, whether histological remission is beneficial in patients with CD has not been well-studied.

Contrary to UC, inflammation in CD is patchy and transmural. As a result, histological remission on segmental biopsies in patients with CD may not accurately reflect a deeper state of remission.5-8 In a recent study from the University of Chicago, Christensen, Erlich, et al7 observed that among 101 patients with ileal CD in clinical remission, histologic remission but not endoscopic remission was associated with favorable long-term outcomes. In contrast, Hu and colleagues8 observed that histologic disease activity was not predictive of risk of relapse in 129 patients with ileal and/or colonic CD in clinical and endoscopic remission.

Hence, we conducted a retrospective study to further evaluate whether achieving histologic remission is beneficial in patients with CD who achieve clinical and endoscopic remission through treatment optimization.

METHODS

Patients

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at a tertiary referral center for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that serves San Diego, California, and surrounding areas. The study was approved by the University of California San Diego (UCSD) Institutional Review Board (IRB #191127).

Inclusion criteria

Patients were included if they met the following criteria: (1) a diagnosis of CD, with a minimum duration of 3 months, based upon standard clinical, endoscopic, and histologic criteria; (2) were seen and followed at UCSD for at least 6 months between 2012 and 2019; (3) underwent at least 2 endoscopic evaluations, with the first evaluation showing clinically and endoscopically active disease; (4) underwent CD-directed therapy with corticosteroids, anti-metabolites, and/or biologic agents under the care of UCSD IBD specialists; and (5) achieved symptomatic remission and endoscopic remission with treat-to-target interventions.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria included the following: (1) the diagnosis of CD was unclear, (2) the terminal ileum was not examined endoscopically, (3) patients with a stoma or history of total proctocolectomy and ileoanal anastomosis, (4) patients with active cancer or a history of organ transplantation or short-bowel syndrome, (5) histological assessment was not performed at the time of endoscopy when endoscopic remission was confirmed, or (6) follow-up duration was <3 months after achieving clinical and endoscopic remission.

Routine Clinical Practice

A team of 5 IBD-trained subspecialists, 2 nurse practitioners, and 1 advanced fellow in IBD manage all patients with IBD at UCSD based on contemporary guidelines. Patients with CD are treated to a target of endoscopic remission (resolution of ulcers) in which they undergo colonoscopy every ~6 months, and if persistent ulcers are observed, then treatment is intensified initially based on therapeutic drug monitoring and then consideration for treatment change, with endoscopic re-evaluation after each treatment change. Patients are not routinely treated to specifically achieve histologic remission given that it is not currently an accepted standard of care. All colonoscopies follow a standard biopsy protocol. If endoscopy is performed for disease activity assessment, then we obtain 2 biopsies each from the worst affected area of the terminal ileum and right and left colon; for dysplasia surveillance, we obtain 32 segmental biopsies from the colon and 4 from the terminal ileum. All slides are reviewed by 1 of 5 gastrointestinal pathologists during routine clinical care. Histologic classifications were modeled based upon the Nancy index (discussed in the following section).

Data Abstraction and Definitions

A single reviewer collected data using a standardized data abstraction form on the following covariates: age at cohort entry, sex, family history of IBD, smoking status, disease duration, age at diagnosis, location and behavior, history of perianal disease, history of abdominal surgery, medication history, medication used for achieving remission, and time taken to achieve endoscopic remission.

Clinical remission was defined as the near-normalization of stool frequency and no abdominal pain according to the treating provider’s documentation. Endoscopic remission was defined as the disappearance of all visible ulcers including aphthae; the presence of erosions, erythema, and bland strictures (without inflammation) was classified as endoscopic remission.9 For patients with multiple colonoscopies showing endoscopic remission, the earliest procedure since the initial colonoscopy was used in the analysis. Histologic remission was evaluated based upon the review of pathology reports generated by subspecialized gastrointestinal pathologists blinded to clinical information.

Because there is no consensus on the definition of histologic remission and no validated histologic activity CD index,10,11 we classified histologic disease activity using 4 categories specified by the Nancy index,12 a validated instrument used in UC: normalization (no evidence of disease), quiescent disease (chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate or architectural changes/distortion without acute inflammatory cell infiltrate), mildly/moderately active disease (neutrophilic infiltrate without erosions and/or ulcers), and severely active disease (erosion or ulcers). Patients who achieved either complete mucosal normalization or quiescent disease with architectural changes without any neutrophilic infiltrate were classified as having achieved histologic remission. Persistent histologic activity was defined as architectural changes with superimposed findings of an acute neutrophilic infiltrate. For patients with biopsies from multiple bowel segments, the segment with the most severe disease was used as the default choice in the analysis to provide the most conservative estimate. For biopsies taken within a segment, the biopsy with the most severe activity for each feature was scored.

Exposure and Outcomes

The population of interest was the subset of patients who achieved clinical and endoscopic remission, classified depending on whether they simultaneously achieved histologic remission or not. The primary outcome measure used to compare these 2 groups was time to treatment failure, which was defined as an increase in stool frequency and/or abdominal pain confirmed objectively to be related to inflammation (on endoscopy, radiology, or biochemically) and requiring a change in medication, initiation of corticosteroids, CD-related hospitalization, and/or CD-related surgery. Intensification of therapy in response to endoscopic or radiologic activity without clinical relapse and without adding corticosteroids was not considered as treatment failure. Surgery for a known fibrotic stricture without definite inflammation was also excluded from treatment failure.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were presented as median plus interquartile range (IQR), and continuous variables were presented as the number (percentage). In the primary analysis, we calculated the cumulative risk of treatment failure using survival analysis, comparing differences in the risk of treatment failure with histologic remission vs persistent histologic activity using the log-rank test. Multivariable Cox proportional hazard analysis was performed to evaluate the independent effect of histologic remission on the risk of treatment failure, adjusting for important covariates that were associated with the risk of treatment failure on univariate analysis at a P value threshold <0.10. All analyses were performed using STATA version 16.0 (StataCorp LLC, Texas), with statistical significance set at a P value threshold of <0.05.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Of 470 patients with clinically and endoscopically active CD, 260 patients (55.3%) successfully achieved clinical and endoscopic remission through iterative treatment modifications over 10 months of follow-up (IQR, 6-20 months; Fig. 1). After excluding patients in whom histology was not evaluated and whose follow-up period after achieving clinical and endoscopic remission was <3 months, 215 patients (median age, 33 years; 46% men) were included in the final analysis.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of patients included in the study.

Histologic Activity Status

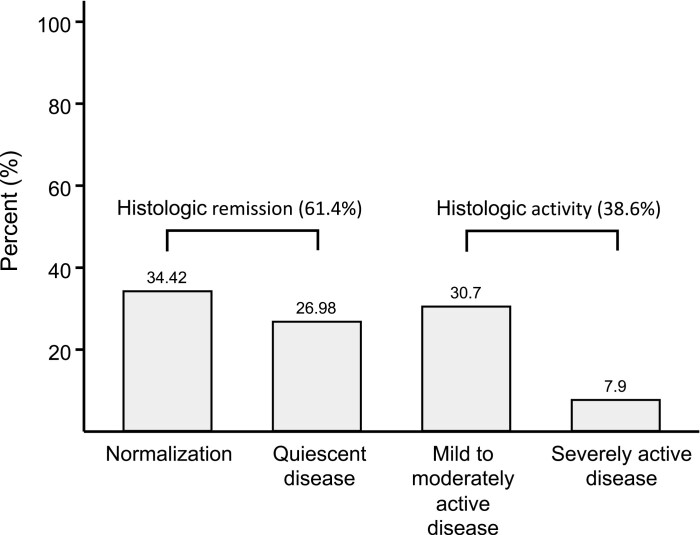

Of the 215 patients with CD in clinical and endoscopic remission, 132 patients (61.4%) simultaneously achieved histologic remission, with 34% achieving complete mucosal normalization. Fig. 2 shows the distribution of histologic activity in included patients. Biopsies in the terminal ileum, right colon, and left colon were performed in approximately 90% of patients; in addition, biopsies in the rectum and transverse colon were performed in approximately 50% and 25% of patients, respectively. No association was observed between the number of segments where biopsies were taken vs the prevalence of histologic remission (P value for trends = 0.11).

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of histologic activity in patients with CD in clinical and endoscopic remission.

Table 1 compares the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients who achieved histologic remission and those with persistent histologic activity. No clinically relevant differences were observed in demographic (age, sex, smoking, family history of IBD), disease (age at onset, disease duration, location, behavior, perianal disease, prior surgery), and treatment characteristics (prior exposure to biologic agents and/or antimetabolites, current pharmacotherapy with which endoscopic remission was achieved, time taken to achieve remission) of patients who did vs those who did not achieve histologic remission after achieving clinical and endoscopic remission.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Patients With CD Treated to Target of Clinical and Endoscopic Remission According to Histologic Results

| Variables | Patients With Persistent Histologic Activity (n = 83) | Patients With Histologic Remission (n = 132) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at enrollment (y) | 33 (24-48) | 33 (24-51) | 0.919 |

| Sex (male) | 44 (53.0) | 55 (41.7) | 0.123 |

| Smoking status | 0.885 | ||

| Never | 63 (75.9) | 100 (75.8) | — |

| Ex-smoker | 14 (16.9) | 20 (15.2) | — |

| Current smoker | 6 (7.2) | 12 (9.1) | — |

| Family history of IBD | 4 (4.8) | 11 (8.3) | 0.416 |

| Disease duration (y) | 7 (1-12) | 5 (1-14) | 0.468 |

| Early CD* | 25 (30.1) | 49 (37.1) | 0.306 |

| Age at diagnosis (y) | 1.0 | ||

| A1 (≤16) | 17 (20.5) | 26 (19.7) | — |

| A2 (17-40) | 52 (62.7) | 83 (62.9) | — |

| A3 (>40) | 14 (16.9) | 23 (17.4) | — |

| Location of disease | 0.888 | ||

| L1 (ileum) | 17 (20.5) | 31 (23.5) | — |

| L2 (colon) | 28 (33.7) | 44 (33.3) | — |

| L3 (ileocolon) | 38 (45.8) | 57 (43.2) | — |

| Behavior of disease | 0.888 | ||

| B1 (nonstricturing and nonpenetrating) | 48 (57.8) | 74 (56.1) | — |

| B2 or B3 | 35 (42.2) | 58 (43.9) | — |

| History of perianal disease | 19 (22.9) | 30 (22.7) | 1.0 |

| History of abdominal surgery | 24 (28.9) | 38 (28.8) | 1.0 |

| Prior exposure to TNF antagonists (before current therapy) | 41 (49.4) | 59 (44.7) | 0.575 |

| Number of prior biologics exposed (before current therapy) | 0.627 | ||

| 0 | 41 (49.4) | 72 (54.6) | — |

| 1 | 23 (27.7) | 29 (22.0) | — |

| ≥2 | 19 (22.9) | 31 (23.5) | — |

| Medication used for achieving remission (current therapy) | 0.724 | ||

| Nonbiologic medications† | 6 (7.2) | 12 (9.1) | — |

| TNF antagonists | 57 (68.7) | 88 (66.7) | — |

| Vedolizumab | 7 (8.4) | 16 (12.1) | — |

| Ustekinumab | 13 (15.7) | 16 (12.1) | — |

| Time taken to achieve ER (mo) | 9 (6-20) | 11 (7-20) | 0.175 |

Variables are expressed as median (interquartile range) or n (%).

*Definition of early CD: disease duration <2 years.

†Nonbiologic medications included antimetabolites, steroids, 5-aminosalicylic acids, or no treatment.

ER indicates endoscopic remission.

Treatment Failure

During a follow-up of median 24 months (IQR, 12-41 months) after achieving endoscopic remission, 67 patients (31.2%) had a treatment failure: 57 patients needed a change in medication and/or initiation of corticosteroids, 8 patients needed CD-related hospitalization, and 2 patients needed CD-related surgery. Among patients with CD who achieved clinical and endoscopic remission, the risk of treatment failure was significantly lower in patients who simultaneously achieved histologic remission (cumulative risk of treatment failure at 1 year and 3 years: 12.9% [95% confidence interval (CI), 8.1-20.2] and 28.4% [95% CI, 20.5-38.6], respectively) compared with patients with persistent histologic activity (18.2% [95% CI, 11.2-28.8] and 39.6% [95% CI, 28.4-53.2], respectively; P = 0.026; Fig. 3). On subgroup analysis, no significant differences were observed in the magnitude of the benefit of histologic remission based on disease location (ileal vs ileocolonic vs colonic CD; P = 0.20), prior exposure to anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents (patients naïve to anti-TNF agents vs patients exposed to anti-TNF agents; P = 0.21), or depth of histologic remission (complete normalization vs quiescent disease vs neutrophilic infiltration; P = 0.08).

FIGURE 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve for time to treatment failure in patients with CD in clinical and endoscopic remission according to histology.

On univariate analysis, colonic CD, nonstricturing and nonpenetrating behavior, no history of abdominal surgery, being naïve to anti-TNF agents, and histologic remission were associated with a lower risk of treatment failure (Table 2). On Cox proportional hazard analysis, only histologic remission (hazard ratio, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.35-0.94) and exposure to anti-TNF agents (hazard ratio, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.03-2.81) were associated with risk for treatment failure.

TABLE 2.

Cox Proportional Hazards Model for Treatment Failure in Patients With CD Treated to Target of Clinical and Endoscopic Remission

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Age (y) | 0.995 | 0.980-1.012 | 0.580 | — | — | — |

| Female | 0.914 | 0.563-1.483 | 0.716 | — | — | — |

| Current smoker | 0.882 | 0.354-2.195 | 0.787 | — | — | — |

| Early CD* | 0.798 | 0.473-1.347 | 0.398 | — | — | — |

| Age at diagnosis (y) | ||||||

| A1 (≤16) | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| A2 (17-40) | 1.350 | 0.698-2.612 | 0.373 | — | — | — |

| A3 (>40) | 1.295 | 0.561-2.992 | 0.545 | — | — | — |

| Location of disease | ||||||

| L1 (ileum) | 1 | — | — | 1 | — | — |

| L2 (colon) | 0.545 | 0.274-1.087 | 0.085 | 0.700 | 0.317-1.546 | 0.378 |

| L3 (ileocolon) | 0.802 | 0.439-1.467 | 0.474 | 0.901 | 0.474-1.713 | 0.750 |

| Behavior of disease | ||||||

| B1 (nonstricturing and nonpenetrating) | 1 | — | — | 1 | — | — |

| B2 or B3 | 1.640 | 1.001-2.687 | 0.049 | 1.344 | 0.706-2.558 | 0.369 |

| History of perianal disease | 1.150 | 0.670-1.976 | 0.612 | — | — | — |

| History of abdominal surgery | 1.702 | 1.021-2.836 | 0.041 | 1.116 | 0.585-2.130 | 0.739 |

| Prior exposure to anti-TNF agent (before current therapy) | 1.769 | 1.087-2.878 | 0.022 | 1.703 | 1.033-2.806 | 0.037 |

| Time taken to achieve ER (mo) | 0.985 | 0.962-1.009 | 0.224 | — | — | — |

| Histologic remission | 0.584 | 0.362-0.943 | 0.028 | 0.574 | 0.352-0.936 | 0.026 |

*Definition of early CD: disease duration <2 years.

ER indicates endoscopic remission; HR, hazard ratio.

DISCUSSION

In this cohort study of well-characterized patients with active CD treated systematically to a target of clinical and endoscopic remission, we made several important observations on the prevalence and impact of histologic remission. First, through iterative treatment modification, we achieved clinical and endoscopic remission in 55% of patients with active CD over a median follow-up of 10 months; approximately 45% of patients with CD failed to meet the proposed treatment endpoint of clinical and endoscopic remission, even though 92% of patients were treated with biologic agents, representing an important treatment gap. Second, among patients with CD who achieved endoscopic remission, approximately 61% simultaneously achieved histologic remission; no demographic, disease, or treatment factors were associated with the ability to achieve histologic remission with treatment optimization. Third, patients with CD with clinical and endoscopic remission who simultaneously achieved histologic remission had a 43% lower risk of treatment failure on follow-up. This finding suggests that incorporating histologic remission beyond conventional clinical and endoscopic remission is worthy of consideration as a treatment target of CD in clinical trials and real-world practice.

Although there is considerable interest in targeting histologic remission, especially in patients with UC, there has been limited evaluation of the feasibility and impact of achieving this target in routine clinical practice in patients with CD. It is notable that in our treat-to-target paradigm, with iterative treatment modifications in response to persistent clinical and/or endoscopic activity, we were able to achieve remission in approximately 55% of patients with CD with current treatment strategies. This rate is comparable to findings observed in the SONIC trial,13 in which 56% of patients with active CD achieved clinical and endoscopic remission by week 26 with a combination of infliximab and thiopurines. However, note that unlike patients in the SONIC trial, approximately 50% of patients in our cohort were biologic-exposed at the time of initial assessment, representing a more refractory population. Of the patients who achieved clinical and endoscopic remission, 34% achieved complete histologic normalization and an additional 27% had quiescent disease without neutrophilic infiltrate. These rates are slightly lower than the rates observed by Hu and colleagues,8 who observed that approximately 75% of patients who achieved endoscopic remission also achieved histologic remission, similar to rates observed in prior studies in patients with CD. In their cohort, however, 90% of patients had complete endoscopic remission (simple endoscopic score-CD score = 0), whereas we defined endoscopic remission based on the absence of ulcers, consistent with STRIDE consensus statements.1 Similar to UC, we could not identify the determinants of histologic remission with the treat-to-target paradigm for managing CD.2,4,14 Future studies that identify the biologic characteristics of patients who are likely to achieve histologic remission beyond endoscopic remission with effective therapies are warranted.

Inflammation in CD is often discontinuous and segmental or may be transmural, beyond the mucosal assessment of a biopsy forceps. Therefore, the predictive value of randomly sampled mucosal histology may be more limited than in UC.15 It has not been determined where and in how many bowel segments the biopsies should be taken in patients with CD to get a representative sample for prediction of disease prognosis, nor have the minimal number of biopsies to assess histological inflammation been assessed. In addition, patients with CD have a high risk of segmental bowel resection, resulting in a reduced number of segments in which to evaluate healing.16 The issue is thus more complicated; the distribution and number of remaining bowel segments vary in patients with CD who have undergone intestinal resection. To explore the potential bias stemming from these variable sampling strategies, we assessed the number and distribution of bowel segments biopsies taken. The proportion of patients achieving histologic remission did not change with the number of segments biopsied. In previous studies, patients who had undergone colectomy were excluded7 or a history of abdominal surgery was not reported.8 In our study, approximately one-third of patients had a history of bowel resection. Because we included patients who had segmental colectomy or subtotal colectomy, our results imply that the protective association between histologic remission and the risk of treatment failure is robust regardless of the remaining bowel segments.

The prognostic significance of incrementally achieving histologic remission beyond clinical and endoscopic remission in patients with CD is unclear. In a retrospective cohort study of 101 patients with isolated ileal CD in clinical remission, Christensen and colleagues7 observed that approximately 62% of patients were in endoscopic remission and 55% of patients were in histologic remission. Only histologic remission, but not endoscopic remission, was associated with decreased clinical relapse, medication escalation, and corticosteroid use. In contrast, Hu and colleagues8 observed no significant difference in the risk of relapse or quality of life in patients with CD in endoscopic remission who did or did not achieve histologic remission. However, by focusing on patients in endoscopic remission in a registry (including 90% with simple endoscopic score-CD = 0) without assessing the duration of endoscopic remission or prior clinical disease activity, their cohort may have been enriched with patients with deep remission at a lower risk of relapse, where the incremental value of histologic disease activity may not have been significant. In contrast, we included only patients with confirmed active CD who achieved clinical and endoscopic remission with iterative treatment modification, to reflect contemporary clinical practice.

Recently, the results of a long-term follow-up study of patients with CD from the CALM trial was reported.17 Achieving deep remission, defined as clinical/endoscopic remission and no steroids for ≥8 weeks, was associated with an 81% decrease in the risk of adverse outcomes over a median of 3 years. The study17 was performed in patients with early CD (disease duration: median 0.2 years), and the original CALM study was a premediated clinical trial. By contrast, our study was performed in patients with a relatively long disease history (disease duration: median 5.4 years) and was a retrospective cohort study based on daily clinical practice. Therefore, it is not appropriate to put these 2 studies on the same line. However, our study suggests that the pursuit of achieving histologic remission in addition to deep remission deserves consideration in patients with CD.

There are several strengths to our study. First, by focusing only on patients with active CD who achieved clinical and endoscopic remission through routine treatment optimization, we were able to review the incremental benefits of simultaneously achieving histologic remission in the context of current practice recommendations. Second, the endoscopy and biopsy sampling protocols and treatment approach were standardized with a small group of IBD experts; 90% of patients had biopsies taken in at least 3 ileocolonic segments. Third, we included patients who had undergone intestinal surgery, and to compensate for the potential bias from biopsy sampling error, we performed analysis adjusting the number of bowel segment biopsies taken.

There are important limitations to our study. First, we did not use a validated histologic scoring system, although none are validated in patients with CD. However, our pathologists routinely model histologic assessment on the Nancy index, based upon its simplicity for routine clinical practice, with levels of classification ranging from the absence of histologic disease to a chronic inflammatory infiltrate with increasing levels of overlying acute inflammatory infiltrate. We were also unable to evaluate the impact of other histological components such as paneth cell metaplasia, plasma cell or eosinophilic infiltrate, and granuloma on risk of treatment failure. Second, we did not use validated indices to assess endoscopic activity. Although these indices are well-suited for clinical trials, they are cumbersome to use in clinical practice. By focusing on the resolution of mucosal ulcers, we were able to adequately comment on achieving current endoscopic treatment targets. Third, because cross-sectional imaging was performed in a limited set of patients at the time of colonoscopy, we were unable to correlate histologic remission with transmural healing. Fourth, very few patients underwent surgery, so it could not be evaluated as a separate outcome. Finally, our findings do not inform the feasibility or outcomes of patients treated specifically toward achieving histologic remission but rather focus on outcomes of patients who simultaneously achieve histologic remission in the context of conventional treat-to-target practices. Patients who achieve histologic remission (61% of cohort) vs those with ongoing histologic activity may be intrinsically more responsive to therapy. Future clinical trials comparing different endpoints in treat-to-target strategies in patients with CD are warranted.

CONCLUSIONS

More than half of patients with active CD were treated to the target of clinical and endoscopic remission through treat-to-target in routine clinical practice. Of these patients, ~61% simultaneously achieved histologic remission, although no demographic, disease, or treatment-related determinants of histologic remission were identified. Patients who achieved histologic remission had a lower risk of treatment failure compared with patients with persistent histologic activity. Our findings support examining histologic remission as a potential treatment endpoint in patients with CD, notwithstanding that this endpoint may difficult to achieve in individual patients.

Author contributions: Concept of the study: Siddharth Singh and William Sandborn; design of the study protocol: Hyuk Yoon and Siddharth Singh; data extraction: Hyuk Yoon; statistical analysis: Hyuk Yoon; manuscript draft: Hyuk Yoon; critical review: Sushrut Jangi, Parambir Dulai, Brigid Boland, Vipul Jairath, Brian Feagan, William Sandborn, and Siddharth Singh.

Supported by: Parambir Dulai was supported by an American Gastroenterology Association Research Scholar Award. Brigid Boland was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (K23DK123406). Siddharth Singh was supported by an American College of Gastroenterology Junior Faculty Development Award #144271, Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation Career Development Award #404614, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (K23DK117058). William Sandborn was supported by the NIDDK-funded San Diego Digestive Diseases Research Center (P30 DK120515). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of interest: Hyuk Yoon and Sushrut Jangi report no conflicts of interest. Parambir Dulai has received research support from Takeda, Pfizer, AbbVie, Janssen, Polymedco, ALPCO, and Buhlmann and consulting fees from Takeda, Pfizer, AbbVie, and Janssen. Brigid Boland has received research support from Prometheus Biosciences and consulting fees from Pfizer. Vipul Jairath has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Genentech, Pendopharm, Sandoz, Merck, Takeda, Janssen, Robarts Clinical Trials, Topivert, and Celltrion and speaker’s fees from Takeda, Janssen, Shire, Ferring, AbbVie, and Pfizer. Brian Feagan has received grant/research support from Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Tillotts Pharma, AbbVie, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Centocor, Elan/Biogen, UCB Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, ActoGenix, and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals; consulting fees from Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Centocor, Elan/Biogen, Janssen-Ortho, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, UCB Pharma, AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Serono, Genentech, Tillotts Pharma, Unity Pharmaceuticals, Albireo Pharma, Given Imaging, Salix Pharmaceuticals, Novonordisk, GSK, ActoGenix, Prometheus Therapeutics and Diagnostics, Athersys, Axcan, Gilead, Pfizer, Shire, Wyeth, Zealand Pharma, Zyngenia, GiCare Pharma, and Sigmoid Pharma; and speaker’s bureau fees from UCB, AbbVie, and J&J/Janssen. William Sandborn has received research grants from Atlantic Healthcare Limited, Amgen, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, AbbVie, Janssen, Takeda, Lilly, Celgene/Receptos, Pfizer, Prometheus Laboratories; consulting fees from AbbVie, Allergan, Amgen, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Avexegen Therapeutics, BeiGene, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Celltrion, Conatus, Cosmo, Escalier Biosciences, Ferring, Forbion, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Gossamer Bio, Incyte, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin Pharmaceutical Research, Landos Biopharma, Lilly, Oppilan Pharma, Otsuka, Pfizer, Progenity, Prometheus Biosciences, Reistone, Ritter Pharmaceuticals, Robarts Clinical Trials, Series Therapeutics, Shire, Sienna Biopharmaceuticals, Sigmoid Biotechnologies, Sterna Biologicals, Sublimity Therapeutics, Takeda, Theravance Biopharma, Tigenix, Tillotts Pharma, UCB Pharma, Ventyx Biosciences, Vimalan Biosciences, and Vivelix Pharmaceuticals; and stock or stock options from BeiGene, Escalier Biosciences, Gossamer Bio, Oppilan Pharma, Prometheus Biosciences, Progenity, Ritter Pharmaceuticals, Ventyx Biosciences, and Vimalan Biosciences. His spouse has been a consultant for Opthotech and Progenity; received stock options from Opthotech, Progenity, Oppilan Pharma, Escalier Biosciences, Prometheus Biosciences, Ventyx Biosciences, and Vimalan Biosciences; and has been an employee of Oppilan Pharma, Escalier Biosciences, Prometheus Biosciences, Ventyx Biosciences, and Vimalan Biosciences. Siddharth Singh has received research grants from AbbVie and Janssen, and personal fees from Pfizer.

REFERENCES

- 1. Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sandborn W, Sands BE, et al. Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE): determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1324–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Christensen B, Hanauer SB, Erlich J, et al. Histologic normalization occurs in ulcerative colitis and is associated with improved clinical outcomes. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1557–1564.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ozaki R, Kobayashi T, Okabayashi S, et al. Histological risk factors to predict clinical relapse in ulcerative colitis with endoscopically normal mucosa. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12:1288–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cushing KC, Tan W, Alpers DH, et al. Complete histologic normalisation is associated with reduced risk of relapse among patients with ulcerative colitis in complete endoscopic remission. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51:347–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baars JE, Nuij VJ, Oldenburg B, et al. Majority of patients with inflammatory bowel disease in clinical remission have mucosal inflammation. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1634–1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brennan GT, Melton SD, Spechler SJ, et al. Clinical implications of histologic abnormalities in ileocolonic biopsies of patients with Crohn’s disease in remission. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51:43–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Christensen B, Erlich J, Gibson PR, et al. Histologic healing is more strongly associated with clinical outcomes in ileal Crohn’s disease than endoscopic healing. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:2518–2525.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hu AB, Tan W, Deshpande V, et al. Ileal or colonic histologic activity is not associated with clinical relapse in patients with Crohn’s disease in endoscopic remission. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Published online April 29, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Daperno M, Castiglione F, de Ridder L, et al. ; Scientific Committee of the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization . Results of the 2nd part Scientific Workshop of the ECCO. II: measures and markers of prediction to achieve, detect, and monitor intestinal healing in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:484–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mojtahed A, Khanna R, Sandborn WJ, et al. Assessment of histologic disease activity in Crohn’s disease: a systematic review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:2092–2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Novak G, Parker CE, Pai RK, et al. Histologic scoring indices for evaluation of disease activity in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7:CD012351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Marchal-Bressenot A, Salleron J, Boulagnon-Rombi C, et al. Development and validation of the Nancy histological index for UC. Gut. 2017;66:43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, et al. ; SONIC Study Group . Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1383–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kanazawa M, Takahashi F, Tominaga K, et al. Relationship between endoscopic mucosal healing and histologic inflammation during remission maintenance phase in ulcerative colitis: a retrospective study. Endosc Int Open. 2019;7:E568–E575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pai RK, Jairath V. What is the role of histopathology in the evaluation of disease activity in Crohn’s disease? Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2019;38–39:101601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Frolkis AD, Dykeman J, Negrón ME, et al. Risk of surgery for inflammatory bowel diseases has decreased over time: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:996–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ungaro RC, Yzet C, Bossuyt P, et al. Deep remission at 1 year prevents progression of early Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:139–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]