Abstract

Background

Psoriasis is a systemic inflammatory disease capable of creating stigmatization in the form of social exclusion and decrement of psychological conditions.

Aim

The aim of the study was to determine the level of stigmatization in patients with plaque psoriasis.

Methods

The study included 166 patients with plaque psoriasis (55.6% women and 44.3% men) with Psoriasis Area and Severity Index scores ≤10. The age of the study patients ranged between 18 and 72 years (arithmetic mean = 37.4; median = 38; standard deviation [SD] = 11.0). The mean age at the diagnosis of psoriasis was 21.5 years (median = 20; SD = 9.1) and disease duration varied from 2 to 59 years (arithmetic mean = 15.8; median = 15; SD = 11.3). The study patients completed the Polish version of the 6-item Stigmatization Scale and the 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire and a survey developed by the authors of this study, containing questions about the participants' sociodemographic characteristics (sex, age, place of residence, marital status, education, employment status) and information about their disease (location of psoriatic lesions, time elapsed since the diagnosis of psoriasis).

Results

The mean score for the 6-item Stigmatization Scale for the whole study group was 7.6 out of 18 points (median = 7; SD = 3.8; minimum = 0; maximum = 17). The average score for the 33-item Stigma Feelings Questionnaire in our series was 84.5 out of 165 points (median = 88; SD = 20.9; minimum = 30; maximum = 136). A statistically significant sex-related difference was observed in the 6-item Stigmatization Scale scores, with higher stigmatization levels found in men than in women (p = 0.0082). Moreover, significantly higher levels of stigmatization were observed in countryside dwellers (p = 0.0311) and unmarried persons (p = 0.0321). Patients with a longer history of the disease (≥15 years) scored significantly higher on the 6-item Stigmatization Scale (p = 0.0217) than those in whom psoriasis lasted less long, and presented with higher, at the threshold of statistical significance, scores for the 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire.

Conclusions

Stigmatization awareness should be promoted among physicians and psoriatic patients to improve psoriasis management.

Keywords: Psoriasis, Psychodermatology, Stigmatization

Introduction

Psoriasis is one of the most common dermatologic conditions worldwide. The most frequently diagnosed form of this chronic inflammatory disease of the skin is plaque psoriasis. Research has shown that psoriasis is not limited to the skin, but can produce systemic effects and be associated with many comorbidities. Psoriasis has been shown to coexist with psoriatic arthritis [1], cardiovascular disorders [1, 2], and diabetes mellitus [2, 3], and its systemic treatment is known to negatively affect alimentary function [4]. The link between psoriasis and other comorbidities, such as respiratory diseases [2], is not fully understood, and available results are conflicting. Due to its recurring clinical course, chronic character, and burdensome treatment, psoriasis may significantly deteriorate quality of life [5]. The disease is not infrequently an underlying cause of depression [1, 2] and other psychological problems, and since it is considered infectious by many, some patients with psoriasis may be stigmatized by people around them.

The term “stigmatization” refers to rejection as a result of having an attribute or physical feature which is deeply disapproved and discredited by society [6], as is the case in psoriasis patients. Stigmatization may not only lead to social exclusion of patients with psoriasis, but may also impair their psychological status, cause depression, or even trigger suicidal attempts [7, 8]. Patients with psoriasis avoid others, limit their social relations to their closest relatives, abandon their work, and eventually completely alienate from society. Furthermore, social stigmatization may eventually result in self-stigmatization, a condition in which the patient feels inferior after any interaction with others [6, 7]. It needs to be emphasized that not only psoriatic lesions visible to others, but also those that are usually covered, e.g., in the genital area, may be a cause of alienation. Stigmatization contributes to decrease in self-esteem, disruption of social roles, and impairment of normal functioning within the work and family environment.

The aim of this study was to determine the level of stigmatization in patients with plaque psoriasis and to analyze the relationships between stigmatization and sociodemographic and clinical variables.

Materials and Methods

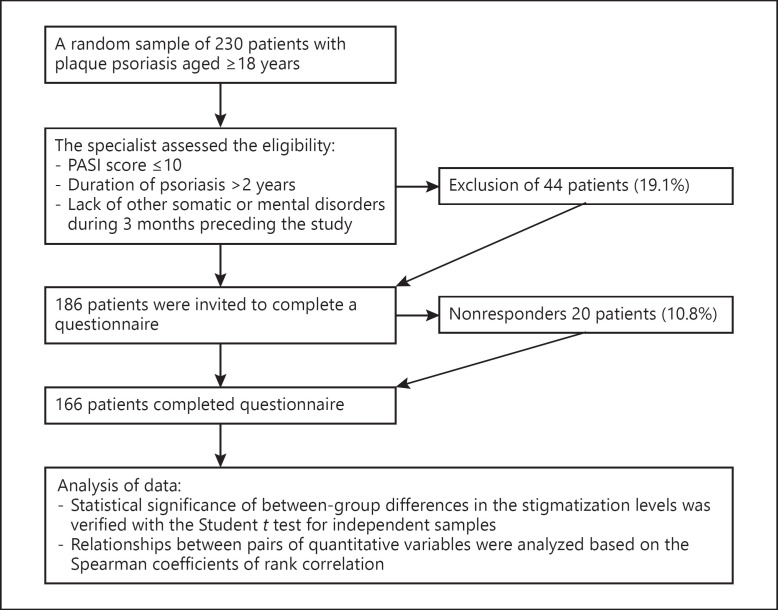

For further details, see the online supplementary material (see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000510654 for all online suppl. material) (Fig. 1) (Table 1) [9].

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of Materials and Methods. PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index.

Table 1.

Patients' detailed descriptive statistics

| Patient characteristics | Me | SD | Min. | Max. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 37.4 | 38 | 11.0 | 16 | 72 |

| Age at the diagnosis, years | 21.5 | 20 | 9.1 | 1 | 45 |

| Duration of the disease, years | 15.8 | 15 | 11.3 | 2 | 59 |

Results

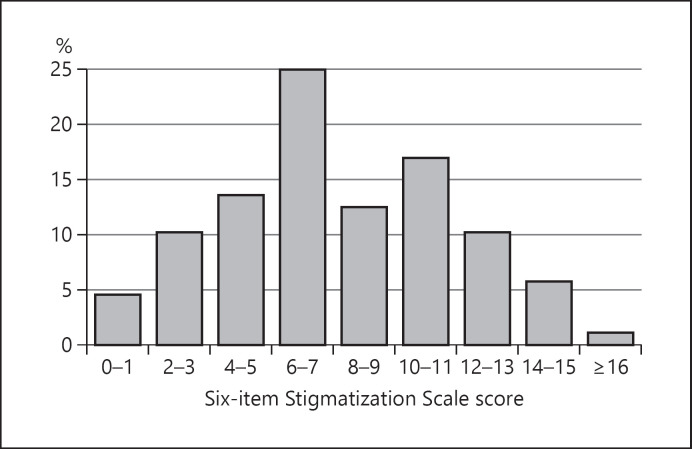

The mean score for the 6-item Stigmatization Scale for the whole study group was 7.6 out of 18 points (Table 2). The study group included 25% of respondents who scored 6–7 points and 34% of patients with scores of 10 points (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Scores for the 6-item Stigmatization Scale

| Me | SD | c25 | c75 | Min. | Max. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7.6 | 7 | 3.8 | 5 | 10 | 0 | 17 |

Fig. 2.

Distribution of the 6-item Stigmatization Scale scores.

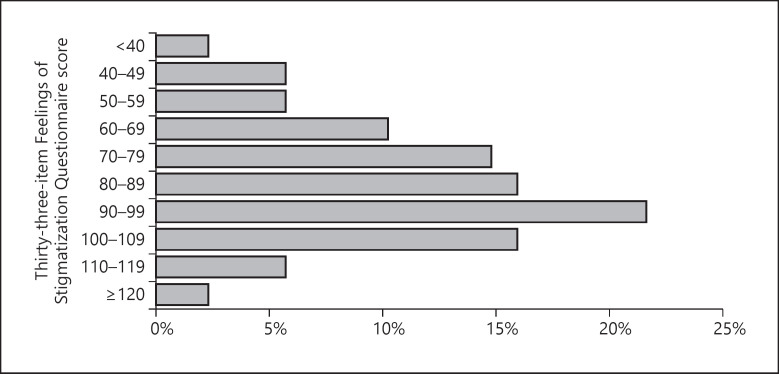

The 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire measures the stigmatization level in six domains: anticipation of rejection, feeling of being flawed, sensitivity to the opinions of others, guilt and shame, positive attitudes, and secretiveness. The mean score for the 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire in our series was 84.5 out of 165 points (Table 3). The results are also presented graphically as the distribution of the overall scores within 10-point brackets (Fig. 3). The largest proportion of the respondents (22%) scored 90–99 points.

Table 3.

Scores for the 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire

| Me | SD | c25 | c75 | Min. | Max. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summary measure | 84.5 | 88 | 20.9 | 70.5 | 99 | 30 | 136 |

| Anticipation of rejection | 21.9 | 22.5 | 6.6 | 17 | 27 | 1 | 35 |

| Feeling of being flawed | 13.8 | 14 | 5.4 | 10 | 18 | 3 | 24 |

| Sensitivity to the opinions of others | 13.3 | 13 | 4.9 | 10 | 17 | 0 | 25 |

| Guilt and shame | 15.3 | 15 | 3.6 | 13 | 17 | 7 | 24 |

| Positive attitudes | 9.2 | 9 | 2.7 | 8 | 11 | 3 | 17 |

| Secretiveness | 11.1 | 11 | 3.6 | 9 | 13.5 | 2 | 20 |

Fig. 3.

Distribution of the 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire scores.

The levels of stigmatization were also analyzed according to the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients with psoriasis (Table 4). A statistically significant sex-related difference was observed in the 6-item Stigmatization Scale scores, with higher stigmatization levels found in men than in women (p = 0.0082). Moreover, significantly higher levels of stigmatization were observed in countryside dwellers (p = 0.0311) and unmarried persons (p = 0.0321).

Table 4.

Scores for the 6-item Stigmatization Scale and the 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire stratified according to sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the patients

| Characteristics | 6-item Stigmatization Scale |

33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD | 95% CI | p value | SD | 95% CI | p value | |||

| Women | 6.7 | 3.2 | 5.8–7.6 | 0.0082** | 81.9 | 17.4 | 76.9–86.9 | 0.1991 |

| Men | 8.8 | 4.1 | 7.5–10.2 | 87.7 | 24.4 | 79.8–95.6 | ||

| Age <40 years | 7.6 | 3.7 | 6.6–8.6 | 0.8922 | 84.7 | 20.8 | 78.8–90.7 | 0.8932 |

| Age ≥40 years | 7.7 | 3.9 | 6.4–9.0 | 84.1 | 21.2 | 77.2–91.1 | ||

| Countryside | 9.1 | 3.6 | 7.5–10.7 | 0.0311* | 88.6 | 15.8 | 81.6–95.6 | 0.2883 |

| Town/city | 7.2 | 3.7 | 6.2–8.1 | 83.1 | 22.2 | 77.6–88.6 | ||

| Married | 7.0 | 3.5 | 6.0–8.0 | 82.5 | 17.9 | 77.3–87.7 | 0.3281 | |

| Unmarried | 8.4 | 4.0 | 7.1–9.7 | 0.0321* | 86.9 | 24.0 | 79.2–94.5 | |

| Higher education | 7.0 | 3.1 | 6.1–8.0 | 0.1335 | 82.4 | 16.3 | 77.4–87.3 | 0.3503 |

| Non-higher education | 8.2 | 4.2 | 7.0–9.5 | 86.6 | 24.6 | 79.1–94.1 | ||

| Blue-collar workers | 8.0 | 3.8 | 6.6–9.4 | 0.2838 | 81.3 | 23.3 | 73.0–89.7 | 0.3900 |

| White-collar workers | 7.1 | 3.3 | 6.1–8.1 | 85.3 | 16.4 | 80.2–90.4 | ||

| Duration of psoriasis <15 years | 6.6 | 3.4 | 5.6–7.7 | 0.0217* | 80.6 | 20.2 | 74.2–87.0 | 0.0965 |

| Duration of psoriasis ≥15 years | 8.5 | 3.8 | 7.3–9.7 | 88.3 | 21.7 | 81.6–95.0 | ||

| Location − exposed body parts | 7.4 | 3.8 | 6.1–8.7 | 0.5018 | 71.7 | 17.9 | 64.0–88.4 | 0.0360* |

| Location − unexposed body parts | 7.8 | 3.8 | 6.8–8.9 | 76.4 | 21.5 | 69.4–92.4 | ||

Statistical significance (p < 0.05).

Statistical significance (p < 0.01).

Both analyzed clinical variables, duration of psoriasis and location of skin lesions, turned out to be significant determinants of stigmatization in the study patients. Patients with a longer history of the disease (≥15 years) scored significantly higher on the 6-item Stigmatization Scale (p = 0.0217) than those in whom psoriasis lasted less long, and presented with higher, at the threshold of statistical significance, scores for the 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire.

Another significant clinical determinant of the stigmatization level was the location of psoriatic lesions, with patients with visible lesions scoring significantly higher on the 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire than those with the lesions invisible to others (p = 0.0360). The sense of stigmatization did not depend on patient age, education, or occupation.

Age and duration of psoriasis were also analyzed as potential correlates of stigmatization. While age did not turn out to be a significant determinant of stigmatization level, a correlation between the duration of psoriasis and stigmatization level determined with the 6-item Stigmatization Scale was at the threshold of statistical significance. The longer the disease, the higher the stigmatization levels found (Table 5).

Table 5.

Correlations of stigmatizations level with patient age and duration of psoriasis

| Psychometric measures | Age | Duration of psoriasis |

|---|---|---|

| 6-item Stigmatization Scale | –0.02 (p = 0.8221) | 0.19 (p = 0.0910) |

| 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire | –0.02 (p = 0.8458) | 0.10 (p = 0.3613) |

p values for Spearman coefficients of rank correlation (R).

Aside from completing the two standardized questionnaires, the study patients were also asked about their subjective feeling of stigmatization. According to 51.1% of the respondents, society does not show tolerance to patients with psoriasis, 57% of the study participants experienced uncomfortable questions about changes in their appearance caused by the disease, and 59.1% claimed that they felt discriminated due to the altered condition of their skin.

Discussion

Each disease, especially chronic, causes various emotional responses in the affected individual. Due to their location, the presence of dermatologic conditions is visible to others and can thus constitute the reason either for lack of acceptance of the disease or for lack of self-acceptance [10, 11, 12, 13].

Erving Goffman, a sociologist from the 1960s, was a pioneer of stigmatization studies. He defined stigma as a sign, a symptom which separates the affected individual from others. Stigmatization may have a direct (voiced opinions and behavior of others) or indirect form (observing the stigmatization of individuals affected with similar condition) or refer to self-stigmatization of a patient (the patient and his/her close relatives feel aversion to his/her body due to the presence of dermatologic lesions). The stigmatization may lead to the so-called “Golem effect,” in which lower expectations of a patient stimulate a deterioration of his/her status [11].

A growing number of studies have recently addressed the effect of psoriasis on mental status and social functioning of patients affected with this disease [14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19]. The results of Young [12], Vardy et al. [13], and Wahl et al. [11] unequivocally indicate that psoriatic patients usually experience insecurity, isolation, and stigmatization, which affects the quality of their lives.

The aim of our present study was to estimate the frequency of stigmatization among patients with psoriasis and to identify its sociodemographic and clinical determinants. Previous studies showed that psoriasis is a strongly stigmatizing disease [20, 21, 22, 23]. According to Zięciak et al. [24], approximately 78% of patients with psoriasis presented with moderate or high stigmatization levels, and in the study conducted by van Beugen et al. [21], up to 73% of patients stated that they experienced being stigmatized. Hrehorów et al. [23] also found moderate levels of stigmatization among patients with psoriasis examined with the 6-item Stigmatization Scale (5.0 ± 3.7 points). In our present study, 61% of the respondents presented with moderate stigmatization levels (7.6 points on the 6-item Stigmatization Scale and 84.5 points on the 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire), which is consistent with the results published by Dimitrov and Szepietowski [22].

According to the literature, the most substantial burdens experienced by patients with psoriasis include observation of their skin lesions by others (1.3 ± 0.9 points) and the misconception of psoriasis as a contagious disease (1.1 ± 0.9 points) [23]. The results of our previous study [25] were similar to those published by Hrehorów et al. [23]; moreover, we demonstrated that patients with psoriasis frequently considered their bodies impure.

Russo et al. [10] revealed that 58% of psoriatic patients experience anxiety due to their condition and that 42% of them suffer from uncertainty. However, it was the body image which proved to be the most harmful aspect of psoriasis; as many as 89% of the respondents declared being ashamed and embarrassed with their body image. Other authors also confirmed that unattractive appearance exerts a significant negative effect on one's self-image, which is reflected by the feelings of being stigmatized and problems in social functioning [7, 26].

Our present study demonstrated that the location of psoriatic lesions might be a significant determinant of stigmatization level. Our study is consistent with previous ones, indicating that the lesions visible to others prove the most harmful for the patients. Similarly, Krueger et al. [27] reported that patients with lesions on the head, hands, and arms perceive their condition as impairing their normal functioning more strongly than those whose psoriatic lesions are limited to the trunk and lower limbs.

The lesions located on the buttocks and in the genital area, usually invisible to others, play a significant role in intimate relationships, and hence may also contribute to a stronger feeling of stigmatization. In a study conducted by Russo et al. [10], >40% of patients with psoriasis experienced sexual problems related to their disease, and another study demonstrated low levels of sexual satisfaction in psoriasis patients [7]. However, in the study conducted by Hawro et al. [28], all patients with psoriasis, regardless of the location of their skin lesions, presented with similar stigmatization levels.

Duration of the disease and patient age were the other factors included in our analysis. In our present study, patients with a longer history of psoriasis presented with higher stigmatization levels than those in whom the disease had been diagnosed more recently (p = 0.0217). This observation is consistent with the results published by van Beugen et al. [21]. Interestingly, we did not find a significant association between patient age and stigmatization level. Patients aged <40 years and those aged ≥40 years had similar mean stigmatization scores: 7.6 and 7.7 points, respectively, for the 6-item Stigmatization Scale, and 84.7 and 84.1 points, respectively, for the 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire. In contrast, both Lu et al. [29] and van Beugen et al. [21] found higher stigmatization levels in younger patients.

Objective changes of image or their subjective perception significantly affect the self-image of psoriatic patients, who perceive themselves as less attractive, worse, or even disgusting. Our study showed that men with psoriasis had higher stigmatization scores than female patients with psoriasis, which is consistent with the results published previously by Miniszewska et al. [30] and Kostyła et al. [31]. However, the results of previous studies analyzing the link between sex and stigmatization are inconclusive. According to Schmid-Ott et al. [19], women presented with higher stigmatization levels than men; similar findings were also reported by Hawro et al. [28] and Krueger et al. [27].

Family situation is an important determinant of psychological status and comfort of life. Understanding and help from family members is of vital importance, as every patient needs large amounts of support from his/her closest relatives. This is equally important for individuals with extensive, visible lesions and for those with small, hidden psoriatic foci. Most patients with psoriasis participating in our study were married (54.5%). Unmarried patients had higher stigmatization scores on both the 6-item Stigmatization Scale and the 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire. Also, according to other authors [21, 29, 32], persons living alone were more prone to stigmatization than married patients.

Stigma can be considered as one of the most powerful social instruments to marginalize or exclude persons with undesirable traits. Stigmatization is a social response to a threat, especially one that cannot be avoided or controlled [6]. In the case of patients with psoriasis, the stigma is represented by the skin lesions which make the patients “different” in the opinion of others.

Conclusions

Stigmatization is an important problem in psoriasis, as it has profound effects on social functioning of the patients. The awareness of psoriasis among laymen should be improved, as better understanding of underlying mechanisms of the disease might be reflected by broader social acceptance and support offered to affected patients.

To improve the outcomes of psoriasis treatment, both physicians and patients should be aware that this disease can be stigmatizing. Holistic treatment is a modern therapeutic approach that should be undertaken by healthcare professionals. The mental condition of psoriatics should be assessed during each visit, and physicians should remember that for these patients, psychological and social problems often constitute a more significant burden than the biological consequences of the disease.

Key Message

In psoriasis, the stigma is represented by skin lesions, and patients are referred to as “others.”

Statement of Ethics

The protocol of the study was approved by the Local Bioethics Committee at the Medical University of Białystok in 2019. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This study were funded by the Medical University of Białystok, Poland. Neither honoraria nor other forms of payments were made for authorship.

Author Contributions

B. Jankowiak was a major contributor in writing the manuscript and supervised this study. She was responsible for patient recruitment, data collection, data analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. B. Kowalewska was a major contributor in writing the manuscript and was involved in the development of the idea, data analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. D.F. Khvorik, E. Krajewska-Kułak, and K. Kowalczuk were involved in the development of the idea and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the patients who participated in the survey.

References

- 1.Armstrong AW, Read C. Pathophysiology, clinical presentation and treatment of psoriasis: A review. JAMA. 2020 May;323((19)):1945–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santus P, Rizzi M, Radovanovic D, Airoldi A, Cristiano A, Conic R, et al. Psoriasis and respiratory comorbidities: the added value of fraction of exhaled nitric oxide as a new method to detect, evaluate and monitor psoriatic systemic involvement and therapeutic efficacy. Bio Med Research International. 2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/3140682. ID 3140682; DOI: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azfar RS, Seminara NM, Shin DB, Troxel AB, Margolis DJ, Gelfand JM. Increased risk of diabetes mellitus and likelihood of receiving diabetes mellitus treatment in patients with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 2012 Sep;148((9)):995–1000. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2012.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fiore M, Leone S, Maraolo AE, Berti E, Damiani G. Liver illness and psoriatic patients. Bio Med Research International. 2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/3140983. ID 3140983, DOI: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zachariae R, Zachariae C, Ibsen HH, Mortensen JT, Wulf HC. Psychological symptoms and quality of life of dermatology outpatients and hospitalized dermatology patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 2004;84((3)):205–12. doi: 10.1080/00015550410023284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. New York: Simon and Schuster; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devrimci-Ozguven H, Kundakci TN, Kumbasar H, Boyvat A. The depression, anxiety, life satisfaction and affective expression levels in psoriasis patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000 Jul;14((4)):267–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2000.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esposito M, Saraceno R, Giunta A, Maccarone M, Chimenti S. An Italian study on psoriasis and depression. Dermatology. 2006;212((2)):123–7. doi: 10.1159/000090652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hrehorów E, Szepietowski JC, Reich A, Evers A, Ginsburg IH. Narzędzia do oceny stygmatyzacji u chorych na łuszczycę: polskie wersje językowe. Derm Klin. 2006;8((4)):253–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Russo PA, Ilchef R, Cooper AJ. Psychiatric morbidity in psoriasis: a review. Australas J Dermatol. 2004 Aug;45((3)):155–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2004.00078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wahl AK, Gjengedal E, Hanestad BR. The bodily suffering of living with severe psoriasis: in-depth interviews with 22 hospitalized patients with psoriasis. Qual Health Res. 2002 Feb;12((2)):250–61. doi: 10.1177/104973202129119874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young M. The psychological and social burdens of psoriasis. Dermatol Nurs. 2005 Feb;17((1)):15–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vardy D, Besser A, Amir M, Gesthalter B, Biton A, Buskila D. Experiences of stigmatization play a role in mediating the impact of disease severity on quality of life in psoriasis patients. Br J Dermatol. 2002 Oct;147((4)):736–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Böhm D, Stock Gissendanner S, Bangemann K, Snitjer I, Werfel T, Weyergraf A, et al. Perceived relationships between severity of psoriasis symptoms, gender, stigmatization and quality of life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013 Feb;27((2)):220–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leibovici V, Canetti L, Yahalomi S, Cooper-Kazaz R, Bonne O, Ingber A, et al. Well being, psychopathology and coping strategies in psoriasis compared with atopic dermatitis: a controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010 Aug;24((8)):897–903. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tyring S, Gottlieb A, Papp K, Gordon K, Leonardi C, Wang A, et al. Etanercept and clinical outcomes, fatigue, and depression in psoriasis: double-blind placebo-controlled randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2006 Jan;367((9504)):29–35. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67763-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langley RG, Feldman SR, Han C, Schenkel B, Szapary P, Hsu MC, et al. Ustekinumab significantly improves symptoms of anxiety, depression, and skin-related quality of life in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010 Sep;63((3)):457–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niemeier V, Nippesen M, Kupfer J, Schill WB, Gieler U. Psychological factors associated with hand dermatoses: which subgroup needs additional psychological care? Br J Dermatol. 2002 Jun;146((6)):1031–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmid-Ott G, Künsebeck HW, Jäger B, Sittig U, Hofste N, Ott R, et al. Significance of the stigmatization experience of psoriasis patients: a 1-year follow-up of the illness and its psychosocial consequences in men and women. Acta Derm Venereol. 2005;85((1)):27–32. doi: 10.1080/000155550410021583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donigan JM, Pascoe VŁ, Kimball AB. Psoriasis and herpes simplex virus are highly stigmatizing compared with other common dermatologic conditions: A survey-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Sep;73((3)):525–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Beugen S, van Middendorp H, Ferwerda M, Smit JV, Zeeuwen-Franssen ME, Kroft EB, et al. Predictors of perceived stigmatization in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2017 Mar;176((3)):687–94. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dimitrov D, Szepietowski JC. Stigmatization in dermatology with a special focus on psoriatic patients. Postepy Hig Med Dosw. 2017 Dec;71((0)):1115–22. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0010.6879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hrehorów E, Salomon J, Matusiak L, Reich A, Szepietowski JC. Patients with psoriasis feel stigmatized. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012 Jan;92((1)):67–72. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zięciak T, Rzepa T, Król J, Żaba R. Feelings of stigmatization and depressive symptoms in psoriasis patients. Psychiatr Pol. 2017;51((6)):1153–63. doi: 10.12740/PP/68848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jankowiak B, Kowalewska B, Fiodaravich Khvorik D, Krajewska-Kułak E, Niczyporuk W. The level of stigmatization and depression of patients with psoriasis. Iran J Public Health. 2016 May;45((5)):690–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leichtman SR, Burnett JW, Robinson HM., Jr Body image concerns of psoriasis patients as reflected in human figure drawings. J Pers Assess. 1981 Oct;45((5)):478–84. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4505_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krueger G, Koo J, Lebwohl M, Menter A, Stern RS, Rolstad T. The impact of psoriasis on quality of life: results of a 1998 National Psoriasis Foundation patient-membership survey. Arch Dermatol. 2001 Mar;137((3)):280–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hawro M, Maurer M, Weller K, Maleszka R, Zalewska-Janowska A, Kaszuba A, et al. Lesions on the back of hands and female gender predispose to stigmatization in patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Apr;76((4)):648–654.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu Y, Duller P, van der Valk PG, Evers AW. Helplessness as predictor of perceived stigmatization in patients with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Psychosom. 2003;4((3)):146–50. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miniszewska J, Juczyński Z, Ograczyk A, Zalewska A. Health-related quality of life in psoriasis: important role of personal resources. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013 Sep;93((5)):551–6. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kostyła M, Tabała K, Kocur J. Illness acceptance degree versus intensity of psychopathological symptoms in patients with psoriasis. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2013 Jun;30((3)):134–9. doi: 10.5114/pdia.2013.35613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ginsburg IH, Link BG. Feelings of stigmatization in patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989 Jan;20((1)):53–63. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(89)70007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data