Abstract

Antidepressants are very widely used and associated with traumatic injury, yet little is known about their potential for harmful drug interactions. We aimed to identify potential drug interaction signals by assessing concomitant medications (precipitant drugs) taken with individual antidepressants (object drugs) that were associated with unintentional traumatic injury. We conducted pharmacoepidemiologic screening of 2000–2015 Optum Clinformatics data, identifying drug interaction signals by performing self-controlled case series studies for antidepressant + precipitant pairs and injury. We included persons aged 16–90 years co-dispensed an antidepressant and ≥1 precipitant drug(s), with an injury during antidepressant therapy. We classified antidepressant person-days as either precipitant-exposed or precipitant-unexposed. The outcome was an emergency department or inpatient discharge diagnosis for unintentional traumatic injury. We used conditional Poisson regression to calculate confounder adjusted rate ratios (RRs) and accounted for multiple estimation via semi-Bayes shrinkage. We identified 330,884 new users of antidepressants who experienced an injury. Among such persons, we studied concomitant use of 7,953 antidepressant + precipitant pairs. Two hundred fifty-six (3.2%) pairs were positively associated with injury and deemed potential drug interaction signals; twenty-two of these signals had adjusted RRs > 2.00. Adjusted RRs ranged from 1.06 (95% confidence interval: 1.00–1.12, p=0.04) for citalopram + gabapentin to 3.06 (1.42–6.60) for nefazodone + levonorgestrel. Sixty-five (25.4%) signals are currently reported in a seminal drug interaction knowledgebase. We identified numerous new population-based signals of antidepressant drug interactions associated with unintentional traumatic injury. Future studies, intended to test hypotheses, should confirm or refute these potential interactions.

Keywords: Antidepressive agents, drug interactions, injury, pharmacoepidemiology, population health, self-controlled case series

INTRODUCTION

Antidepressants are the most commonly used drug class among Americans aged 20–59 years,1 and the second most common among persons of all ages.2 Antidepressants have been consistently associated with many types of unintentional traumatic injuries,3–6 which may be mediated through their known effects on central nervous system (CNS) sedation, hypotension, hypoglycemia, and other adverse effects. Unintentional injury is a major cause of morbidity and disability;7,8 it is the leading and fourth leading cause of death in Americans <45 years of age and persons of all ages, respectively.9 Among older adults, falls and motor vehicle crashes predominate,10 leading to dramatic increases in mortality from injury beginning at 70 years of age.9

The majority of persons with depression have multiple chronic conditions, which greatly increases the likelihood of polypharmacy and therefore predisposes such individuals to potentially deleterious drug interactions. This may be of particular concern for the co-prescribing of antidepressants with other drugs having sedation potential.4 Such a pharmacodynamic mechanism, in addition to interactions with pharmacokinetic underpinnings,11 may contribute to antidepressant-attributed unintentional traumatic injuries. Reducing these events is of major public health importance, as such injuries often result in hospitalization and death, yet the precipitating drug interactions are potentially preventable. Therefore, it is understandable that numerous clinical practice guidelines11–16 consider drug interaction potential as a factor to consider when selecting an antidepressant, especially in older adults. Relatedly, the United States (US) Senate Special Committee on Aging recently emphasized the potential role of interactions between CNS-active drugs on fall risk in older adults.17 Further, the US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration considers the identification of antidepressant drug interactions as a critical countermeasure to prevent drug-impaired driving leading to injurious crashes.18

Prior population-based studies of antidepressant drug interactions and injury have been largely limited to concomitant use with alcohol,19,20 benzodiazepines,20–31 opioids,27,29 and/or anticholinergic drugs.23,29 While an initial focus on these CNS-active agents is intuitive, this leaves a critical knowledge gap. Antidepressants are co-prescribed with hundreds of other commonly used medications that may interact through known and unknown pharmacodynamic and/or pharmacokinetic mechanisms. The lack of evidence is especially worrisome given the high prevalence of polypharmacy among persons treated for depression.

Responding to the critical need to identify antidepressant drug interactions, we conducted high-throughput pharmacoepidemiologic screening of healthcare billing data to identify signals of potential clinically important interactions with antidepressants that might increase unintentional traumatic injury rates. We sought to provide researchers with an evidence-based list of signals, so that limited available resources could be directed to confirm or refute these potential interactions in future etiologic studies.

METHODS

Overview of pharmacoepidemiologic screening: Identifying antidepressant drug interaction signals

We conducted semi-automated, high-throughput pharmacoepidemiologic screening of US healthcare billing data to identify antidepressant drug interaction signals. We created new user cohorts of individuals who received antidepressants of interest (object drugs, the affected drugs of drug pairs32). Within these cohorts, we identified: exposure to candidate interacting precipitants (the affecting drugs of drug pairs32), operationalized as orally administered drugs frequently co-dispensed with antidepressants; and outcomes of interest. Of note, object-precipitant nomenclature is most intuitive for pharmacokinetic interactions.32 We subsequently identified signals by performing thousands of confounder-adjusted self-controlled case series studies to examine associations between individual antidepressant + candidate precipitant pairs and unintentional traumatic injury (the primary outcome), typical hip fracture (a secondary outcome), and motor vehicle crash while the subject was driving (a secondary outcome).

For each antidepressant-precipitant pair, we conducted a bi-directional (defined in Supplemental Methods) self-controlled case series study to examine outcome rates in an antidepressant-treated individual during time exposed vs. unexposed to the precipitant. The self-controlled case series is a rigorous self-matched epidemiologic study design built on the framework of a cohort study, limited to persons experiencing an outcome of interest. The design is well-suited for drug interaction screening because: a) the causal contrast is made within an individual and thus inherently controls for confounding by static factors over an individual’s observation period (e.g., genetics); b) the statistical model can (and does) control for dynamic factors; c) the approach is computationally-efficient, as it is limited to persons experiencing an outcome; and d) there is ample precedent for the use of high-throughput applications. Analogous screening studies have identified drugs associated with hypoglycemia in persons using insulin secretagogues,33 rhabdomyolysis in persons using statins,34 serious bleeding in persons using clopidogrel35 and anticoagulants,34,36,37 and injury in persons using opioids38 as examples. Methods detailed below were adapted from our prior work on opioids.38

Data source

We used longitudinal enrollment and healthcare billing data within Optum Clinformatics Data Mart (May 1, 2000–September 30, 2015). The Data Mart includes >71 million commercially insured and Medicare Advantage beneficiaries from the largest US-based private health insurer by market share. See detail in Supplemental Methods.

Creating new user cohorts

We constructed a study cohort for new users, aged 16–90 years, of each antidepressant object drug. We required a 183-day baseline period that was devoid of a dispensed prescription for the given antidepressant. We utilized pharmacy claim dates and days’ supply values to build object drug exposure episodes consisting of ≥1 dispensed prescription of the object antidepressant. We allowed a grace period—length calculated as days’ supply × 0.20, assuming 80% adherence—between contiguous antidepressant dispensings and at the end of the terminal dispensing.

Defining observation and baseline periods

For each antidepressant new user meeting inclusion criteria, we started the observation period upon antidepressant initiation and stopped it upon the earliest of: a) lapsed antidepressant exposure (permitting the grace period); b) a switch from a solid to non-solid formulation of the antidepressant; c) a switch from the antidepressant to an alternative antidepressive medication; d) health plan disenrollment (permitting a 45-day maximum enrollment gap); or e) the dataset end date. Given the case-only design, we required an outcome occurrence during each new use observation period. To ensure the validity of the self-controlled case series design, we did not censor the observation period upon outcome occurrence.

The baseline period was the 183 days immediately preceding yet excluding the observation period begin date. We required it to be devoid of: an interruption in insurance coverage; and a dispensing for the given antidepressant. To allow us to study second- and later-line antidepressant therapies, we did not exclude object episodes preceded by a baseline dispensing for an alternative antidepressant.

Identifying candidate interacting precipitant drugs during antidepressant use

We used pharmacy claim dates and days’ supply values (including grace periods) to identify dispensed prescriptions for oral route solid formulation antidepressants, as object drugs. During periods of apparent antidepressant use, we used pharmacy claim dates and days’ supply values (excluding grace periods, to minimize exposure misclassification) to identify dispensed prescriptions for any orally administered concomitant medication (precipitant drugs of interest). We utilized Facts & Comparisons eAnswers to categorize objects and precipitants by medication class. We lacked explicit data on clinical indications for objects and precipitants. See detail in Supplemental Methods.

Using precipitant drug exposure to categorize observation period time

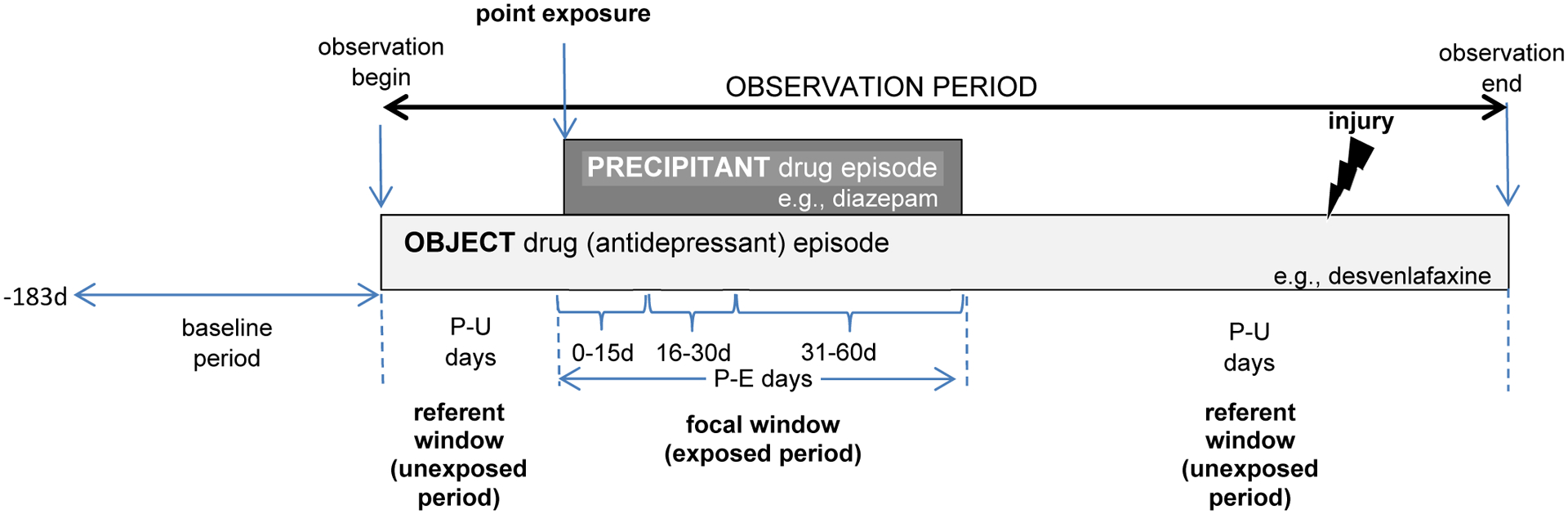

We classified each observation day as precipitant-exposed or precipitant-unexposed. The former was defined by concomitant exposure to the object and candidate interacting precipitant drug and constituted focal windows, i.e., precipitant-exposed periods. The latter was all other observation days and constituted referent windows, i.e., precipitant-unexposed periods. We permitted referent windows before and after focal windows. Figure 1 provides a graphical representation of the design.

Figure 1. Example of antidepressant object drug episode eligible for inclusion.

The focal window is comprised of precipitant-exposed person-days. The referent windows are comprised of precipitant-unexposed person-days. The presence of a referent window before and after the focal window is indicative of a bi-directional implementation of the self-controlled case series design. P-E = precipitant-exposed; P-U = precipitant-unexposed.

Several studies have found that the risk of an adverse event due to a drug interaction often peaks shortly after initiating concomitant therapy and declines thereafter.39–41 Therefore, we examined a duration-response relationship for each object-precipitant pair by stratifying focal window time as follows: 0–15, 16–30, 31–60, 61–120, and 121–180 days from the point exposure.

Defining the exposure and covariates

Exposure was defined by candidate precipitant drug use. The self-controlled case series design implicitly controls for static, but not dynamic, covariates. To address the latter, we included in the regression model for each antidepressant the following covariates assessed during each observation day: a) antidepressant average daily dose based on the most recent prescription dispensing; and b) ever prior injury diagnosis on any claim type. Accounting for the latter is important since prior injury may predict subsequent injury, and the self-controlled case series design does not censor upon outcome occurrence.

Identifying outcomes

We defined unintentional traumatic injury, the primary outcome, as an emergency department or inpatient hospitalization for fracture, dislocation, sprain/strain, intracranial injury, internal injury of thorax, abdomen, or pelvis, open wound, injury to blood vessels, crushing injury, injury to nerves or spinal cord, or certain traumatic complications and unspecified injuries. Consistent with the American College of Surgeons’ National Trauma Data Standard, this excluded: late effects of injuries, poisonings, toxic effects, and other external causes; superficial injuries; contusions with intact skin surface; and effects of a foreign body entering through orifice. Consistent with work by Sears et al,42 we also excluded burns; such injuries seem unlikely due to antidepressant use.

Inpatient hospitalization for typical hip fracture was a secondary outcome; prior meta-analyses found antidepressants to be associated with hip fracture.43,44 We excluded: pathologic hip fractures, since often due to a localized process (e.g., malignancy); and atypical hip fractures, since infrequently traumatic and commonly attributed to bisphosphonate and/or corticosteroid use. We also examined, as a secondary outcome, motor vehicle crash while the subject was driving; antidepressants have been associated with motor vehicle crash.20,23,29,45,46 We defined this endpoint as an unintentional traumatic injury with an external cause of injury code for an unintentional traffic or nontraffic accident. Consistent with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s injury mortality framework, we excluded crashes of a self-inflicted, assault, or undetermined manner. Our study of motor vehicle crash resulted in our decision to study persons as young as 16 years, the minimum driving age for the vast majority of states. We provide operational outcome definitions, their operating characteristics, and other support for their use in Table S1.

Statistical analysis

For each antidepressant-outcome pair, we created an analytic file in which the unit of observation was the person-day during an active prescription for that antidepressant. The dichotomous dependent variable was whether an unintentional traumatic injury occurred on that day. Independent variables were: subject ID, whether a person-day was exposed or unexposed to the precipitant; and the dynamic covariates previously discussed. The parameter of interest was the outcome occurrence rate ratio during focal vs. referent windows, i.e., rateobject+precipitant / rateobject. We separately examined, in a secondary analysis, rate ratios for the mutually exclusive focal window strata discussed above. We used conditional Poisson regression models (xtpoisson with fe option, Stata v.16) to estimate rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We did not estimate rate ratios in settings of statistical instability. See detail in Supplemental Methods.

We used a semi-Bayes shrinkage method to address multiple estimation inherent in calculating numerous rate ratios. This increases effect estimate validity and minimizes false positive findings. See detail in Supplemental Methods.

To contextualize findings, we compared drug interaction signals generated by our screening approach to putative interactions documented in two drug interaction knowledgebases: Micromedex and Facts & Comparisons eAnswers.

Institutional review board approval and role of funding

The University of Pennsylvania’s institutional review board approved this research as protocol #831486. The US National Institutes of Health had no input on the conduct or interpretation of this research.

RESULTS

Table S2 summarizes characteristics of persons constituting object drug cohorts for analyses of unintentional traumatic injury. Twelve of 26 antidepressants under study provided ≥1 million (M) person-days of observation (range: 1.3M for nortriptyline to 15.6M for sertraline); agents included five selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs: citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline), two serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs: duloxetine, venlafaxine), two tricyclics (amitriptyline, nortriptyline), one 5-hydroxytryptamine2 receptor antagonist (trazodone), one dopamine reuptake blocker (bupropion), and one noradrenergic antagonist (mirtazapine). For these commonly used antidepressants, cohorts ranged from 5,442 new users of nortriptyline to 55,756 new users of sertraline, all of whom by design experienced an injury; the three most commonly occurring injuries were sprain/strain (47.7%), certain traumatic complications and unspecified injuries (24.2%), and dislocation (20.3%). Median durations of observation ranged from 92 days for trazodone to 185 days for venlafaxine. Users were predominantly female and Caucasian; the plurality were South Atlantic US residents. Median age upon initiation of new use ranged from 49.8 years for bupropion to 79.1 years for mirtazapine. In analyses of secondary outcomes, 10 and four antidepressants under study provided ≥100,000 person-days of observation for typical hip fracture and motor vehicle crash, respectively. Cohorts ranged from 468 new users of paroxetine with a motor vehicle crash to 3,267 new users of sertraline with a typical hip fracture. Table S3 and Table S4 summarize characteristics of persons constituting object drug cohorts for analyses of secondary outcomes.

For the study of unintentional traumatic injury, we identified 713 candidate interacting precipitant drugs co-prescribed with one of the 26 antidepressants of interest. After application of inclusion criteria, we examined 617 precipitants in at least one confounder-adjusted self-controlled case series study. The number of precipitants studied ranged from two for trimipramine to 567 for sertraline. Table 1 provides summary data on rate ratios for unintentional traumatic injury, before and after confounder adjustment; Table S5 and Table S6 provide summary data for typical hip fracture and motor vehicle crash, respectively. Heat maps in Figure S1, Figure S2, and Figure S3 graphically depict confounder-adjusted rate ratios for all outcomes using the primary variance parameter for semi-Bayes shrinkage, corresponding findings using the alternate variance parameter (which yielded similar results), and duration-response findings for the primary outcome, respectively. Fifty-four (87.1%) of 62 viable conditional Poisson models were able to accommodate the inclusion of antidepressant average daily dose as a time-varying covariate (Table S7).

Table 1.

Summary data on candidate interacting precipitants and semi-Bayes shrunk rate ratios for unintentional traumatic injury, by antidepressant object drug

| Object drug | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amitriptyline | Amoxapine | Bupropion | Citalopram | Clomipramine | Desipramine | Desvenlafaxine | Doxepin | Duloxetine | |

| Unadjusted analyses | |||||||||

| Candidate interacting precipitants examined, count | 495 | 21 | 483 | 549 | 121 | 175 | 303 | 341 | 485 |

| DDI signals, count (%) | 33 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 37 (7.7) | 50 (9.1) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (3.0) | 13 (3.8) | 30 (6.2) |

| Increased rate* | 11 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (2.7) | 19 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.3) | 4 (1.2) | 13 (2.7) |

| Decreased rate** | 22 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 24 (5.0) | 31 (5.6) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (1.7) | 9 (2.6) | 17 (3.5) |

| RR range, min to max | 0.40 – 1.92 | 0.69 – 1.27 | 0.55 – 2.15 | 0.41 – 2.52 | 0.45 – 1.85 | 0.63 – 2.08 | 0.50 – 2.09 | 0.54 – 1.89 | 0.58 – 2.60 |

| Confounder-adjusted analyses | |||||||||

| Candidate interacting precipitants examined, count | 495 | 21 | 483 | 549 | 121 | 174 | 303 | 341 | 484 |

| DDI signals, count (%) | 40 (8.1) | 0 (0.0) | 38 (7.9) | 55 (10.0) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (1.1) | 10 (3.3) | 11 (3.2) | 32 (6.6) |

| Increased rate* | 16 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (3.3) | 27 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.1) | 5 (1.7) | 5 (1.5) | 16 (3.3) |

| Decreased rate** | 24 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 22 (4.6) | 28 (5.1) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (1.7) | 6 (1.8) | 16 (3.3) |

| RR range, min to max | 0.39 – 1.94 | 0.60 – 1.26 | 0.55 – 2.19 | 0.42 – 2.45 | 0.52 – 1.98 | 0.59 – 2.10 | 0.50 – 2.08 | 0.50 – 2.05 | 0.55 – 2.62 |

| Escitalopram | Fluoxetine | Fluvoxamine | Imipramine | Levomilna. | Maprotiline | Mirtazapine | Nefazodone | Nortriptyline | |

| Unadjusted analyses | |||||||||

| Candidate interacting precipitants examined, count | 560 | 546 | 181 | 296 | 11 | 13 | 449 | 206 | 384 |

| DDI signals, count (%) | 39 (7.0) | 39 (7.1) | 6 (3.3) | 3 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 30 (6.7) | 4 (1.9) | 17 (4.4) |

| Increased rate* | 18 (3.2) | 16 (2.9) | 5 (2.8) | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 25 (5.6) | 3 (1.5) | 9 (2.3) |

| Decreased rate** | 21 (3.8) | 23 (4.2) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (1.1) | 1 (0.5) | 8 (2.1) |

| RR range, min to max | 0.43 – 1.95 | 0.59 – 2.18 | 0.43 – 2.24 | 0.55 – 2.10 | 1.23 – 2.31 | 0.91 – 2.06 | 0.55 – 2.22 | 0.59 – 3.05 | 0.57 – 2.44 |

| Confounder-adjusted analyses | |||||||||

| Candidate interacting precipitants examined, count | 560 | 545 | 181 | 294 | 11 | 13 | 449 | 206 | 383 |

| DDI signals, count (%) | 39 (7.0) | 41 (7.5) | 7 (3.9) | 5 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 34 (7.6) | 5 (2.4) | 16 (4.2) |

| Increased rate* | 20 (3.6) | 20 (3.7) | 5 (2.8) | 3 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 24 (5.3) | 5 (2.4) | 10 (2.6) |

| Decreased rate** | 19 (3.4) | 21 (3.9) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (1.6) |

| RR range, min to max | 0.41 – 2.06 | 0.48 – 2.28 | 0.45 – 2.26 | 0.48 – 2.15 | 1.36 – 2.54 | 0.91 – 2.06 | 0.52 – 2.38 | 0.61 – 3.06 | 0.53 – 2.96 |

| Paroxetine | Protriptyline | Sertraline | Trazodone | Trimipramine | Venlafaxine | Vilazodone | Vortioxetine | ||

| Unadjusted analyses | |||||||||

| Candidate interacting precipitants examined, count | 529 | 36 | 567 | 490 | 2 | 510 | 164 | 44 | |

| DDI signals, count (%) | 35 (6.6) | 0 (0.0) | 62 (10.9) | 30 (6.1) | 0 (0.0) | 45 (8.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Increased rate* | 13 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 23 (4.1) | 13 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Decreased rate** | 22 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 39 (6.9) | 17 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) | 27 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| RR range, min to max | 0.50 – 2.01 | 0.78 – 1.87 | 0.48 – 2.44 | 0.40 – 1.99 | 0.81 – 0.86 | 0.51 – 1.79 | 0.57 – 2.05 | 0.73 – 1.72 | |

| Confounder-adjusted analyses | |||||||||

| Candidate interacting precipitants examined, count | 528 | 36 | 567 | 490 | 2 | 510 | 164 | 43 | |

| DDI signals, count (%) | 35 (6.6) | 0 (0.0) | 60 (10.6) | 30 (6.1) | 0 (0.0) | 46 (9.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Increased rate* | 17 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | 28 (4.9) | 16 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 21 (4.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Decreased rate** | 18 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | 32 (5.6) | 14 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 25 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| RR range, min to max | 0.48 – 1.98 | 0.80 – 1.88 | 0.47 – 2.44 | 0.42 – 2.02 | 1.20 – 1.26 | 0.46 – 1.81 | 0.57 – 2.02 | 0.67 – 1.63 | |

DDI = drug-drug interaction; levomilna. = levomilnacipran; max = maximum; min = minimum; RR = rate ratio

lower bound of the 95% confidence interval for the RR of interest excluded the null value

upper bound of the 95% confidence interval for the RR of interest excluded the null value

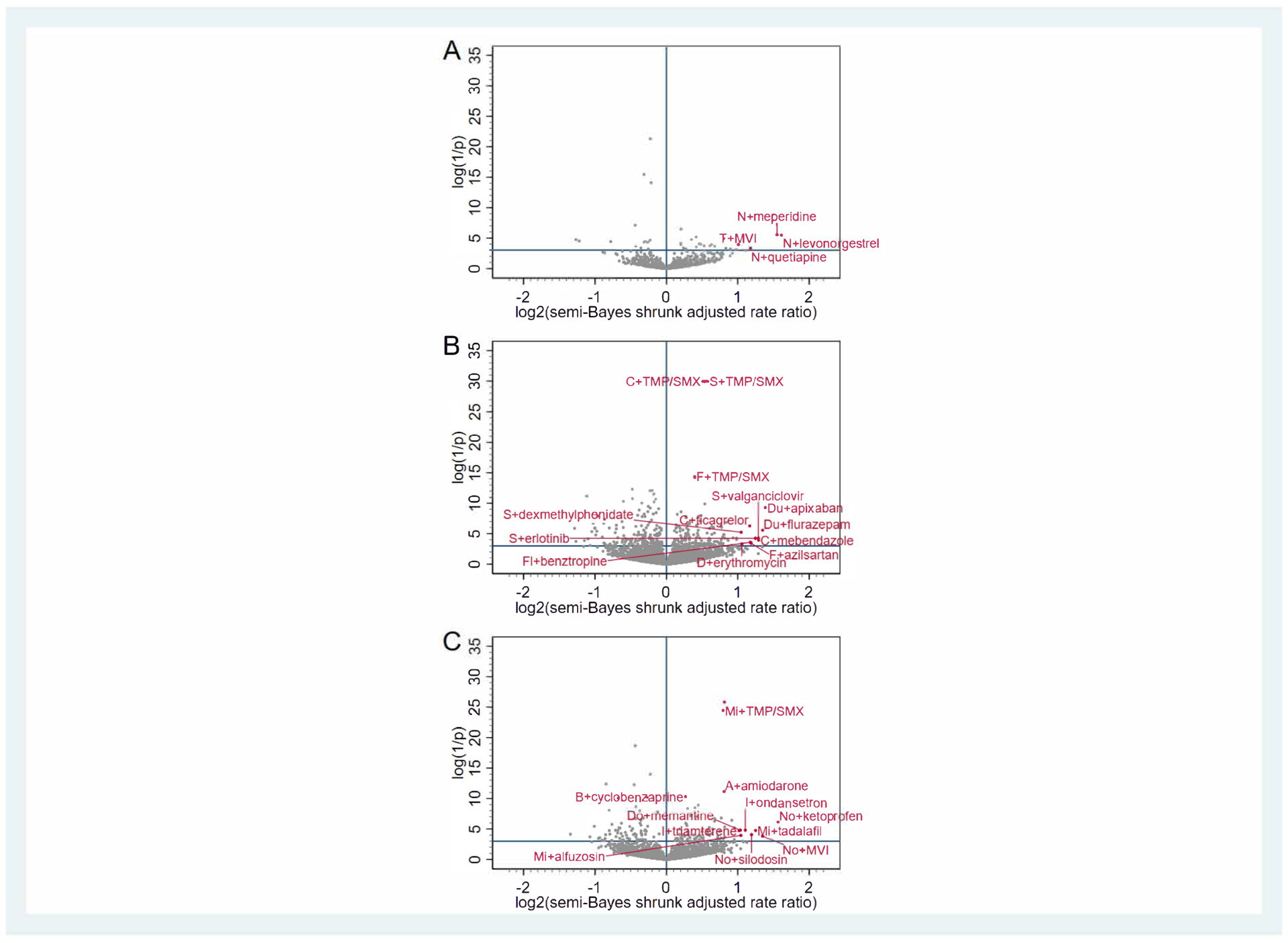

Among 7,953 antidepressant + precipitant pairs included for study, 256 (3.2%, consisting of 158 unique precipitants) had statistically significantly elevated adjusted rate ratios for unintentional traumatic injury after semi-Bayes shrinkage. We therefore deemed these pairs as potential drug interaction signals (Table 2 and Figure 2). Signals for unintentional traumatic injury included precipitants in the following therapeutic classes: CNS agents (N = 81 of 256 signals, including 17 benzodiazepines, 10 muscle relaxants, and 9 opioids); anti-infective agents (N = 40); endocrine and metabolic agents (N = 31); renal and genitourinary agents (N = 28); cardiovascular agents (N = 27); gastrointestinal agents (N = 16); hematologic agents (N = 10); nutrients and nutritional agents (N = 10); respiratory agents (N = 6); biologic and immunologic agents (N = 4); and antineoplastic agents (N = 3). Semi-Bayes shrunk adjusted rate ratios for unintentional traumatic injury signals ranged from 1.06 (95% CI 1.00–1.12, p = 0.042) for citalopram + gabapentin to 3.06 (1.42–6.60) for nefazodone + levonorgestrel; among users of antidepressants with benzodiazepines, muscle relaxants, or opioids, signals were strongest for duloxetine + flurazepam (2.54, 1.35–4.79), desvenlafaxine + metaxalone (1.53, 1.07–2.18), and nefazodone + meperidine (2.94, 1.41–6.12), respectively. Sixty-five (25.4%), 39 (15.2%), and 31 (12.1%) of the 256 potential drug interaction signals are currently reported in Micromedex, Facts & Comparisons eAnswers, and both knowledgebases, respectively.

Table 2.

Antidepressant drug interaction signals, given statistically significantly increased rates of unintentional traumatic injury, by pharmacologic class of antidepressant, by therapeutic category of precipitant drug, by magnitude of association

| Object drug (ASO rating) | Precipitant drug | Precipitant drug therapeutic category | RR, semi-Bayes shrunk | Lower bound of 95% CI | Upper bound of 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-hydroxytryptamine2 receptor antagonist | |||||

| Nefazodone (4) | meperidine*,**,*** | CNS | 2.94 | 1.41 | 6.12 |

| quetiapine†,‡ | 2.26 | 1.06 | 4.83 | ||

| levonorgestrel | Endocrine and metabolic | 3.06 | 1.42 | 6.60 | |

| finasteride | Renal and genitourinary | 1.86 | 1.03 | 3.38 | |

| cetirizine | Respiratory | 1.55 | 1.07 | 2.25 | |

| Trazodone (3) | cefaclor*** | Anti-infective | 1.96 | 1.01 | 3.81 |

| hydroxychloroquine* | Biologic and immunologic | 1.38 | 1.06 | 1.80 | |

| hydralazine | CV | 1.40 | 1.06 | 1.85 | |

| indomethacin†,*** | CNS | 1.45 | 1.05 | 2.00 | |

| nabumetone†,*** | 1.34 | 1.03 | 1.75 | ||

| donepezil* | 1.18 | 1.01 | 1.38 | ||

| lorazepam* | 1.15 | 1.03 | 1.29 | ||

| desogestrel | Endocrine and metabolic | 1.75 | 1.16 | 2.64 | |

| liothyronine | 1.53 | 1.06 | 2.21 | ||

| risedronate | 1.28 | 1.07 | 1.54 | ||

| levothyroxine | 1.15 | 1.06 | 1.26 | ||

| sodium biphosphate* | GI | 1.78 | 1.04 | 3.06 | |

| metoclopramide | 1.34 | 1.09 | 1.65 | ||

| multivitamin with iron | Nutrients and nutritional | 2.02 | 1.12 | 3.64 | |

| spironolactone | Renal and genitourinary | 1.21 | 1.01 | 1.45 | |

| homatropine | Respiratory | 1.60 | 1.05 | 2.44 | |

| Dopamine reuptake blocking compound | |||||

| Bupropion (1) | nebivolol†,‡ | CV | 1.41 | 1.03 | 1.92 |

| valsartan | 1.23 | 1.05 | 1.43 | ||

| atorvastatin | 1.10 | 1.01 | 1.19 | ||

| rizatriptan | CNS | 1.26 | 1.03 | 1.54 | |

| buspirone | 1.23 | 1.04 | 1.45 | ||

| pregabalin | 1.23 | 1.01 | 1.49 | ||

| cyclobenzaprine*** | 1.21 | 1.10 | 1.32 | ||

| glimepiride | Endocrine and metabolic | 1.37 | 1.05 | 1.79 | |

| glipizide | 1.31 | 1.02 | 1.69 | ||

| allopurinol | 1.27 | 1.00 | 1.60 | ||

| lubiprostone | GI | 1.70 | 1.24 | 2.34 | |

| metolazone | Renal and genitourinary | 1.76 | 1.08 | 2.89 | |

| silodosin | 1.70 | 1.05 | 2.74 | ||

| furosemide | 1.21 | 1.07 | 1.36 | ||

| sildenafil | 1.17 | 1.00 | 1.36 | ||

| cetirizine | Respiratory | 1.15 | 1.01 | 1.32 | |

| Noradrenergic antagonist | |||||

| Mirtazapine (3) | clarithromycin*** | Anti-infective | 1.94 | 1.21 | 3.09 |

| trimethoprim*** | 1.76 | 1.50 | 2.06 | ||

| sulfamethoxazole*** | 1.74 | 1.48 | 2.05 | ||

| metronidazole | 1.37 | 1.02 | 1.86 | ||

| levofloxacin*** | 1.34 | 1.13 | 1.60 | ||

| rosuvastatin | CV | 1.57 | 1.13 | 2.16 | |

| amiodarone | 1.32 | 1.00 | 1.74 | ||

| caffeine | CNS | 1.89 | 1.27 | 2.80 | |

| butalbital*** | 1.76 | 1.19 | 2.61 | ||

| primidone | 1.62 | 1.02 | 2.57 | ||

| lamotrigine | 1.60 | 1.19 | 2.14 | ||

| pregabalin | 1.60 | 1.20 | 2.12 | ||

| alprazolam* | 1.32 | 1.14 | 1.54 | ||

| tramadol*,**,*** | 1.23 | 1.10 | 1.38 | ||

| lorazepam* | 1.22 | 1.07 | 1.40 | ||

| megestrol | Endocrine and metabolic | 1.24 | 1.04 | 1.49 | |

| rabeprazole | GI | 1.74 | 1.05 | 2.89 | |

| clopidogrel | Hematological | 1.37 | 1.16 | 1.60 | |

| tadalafil | Renal and genitourinary | 2.38 | 1.25 | 4.53 | |

| alfuzosin | 2.06 | 1.12 | 3.77 | ||

| solifenacin | 1.43 | 1.01 | 2.03 | ||

| spironolactone | 1.35 | 1.04 | 1.76 | ||

| hydrochlorothiazide | 1.21 | 1.07 | 1.38 | ||

| furosemide | 1.12 | 1.01 | 1.23 | ||

| Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors | |||||

| Desvenlafaxine (0) | erythromycin*** | Anti-infective | 2.08 | 1.04 | 4.14 |

| fenofibrate | CV | 1.48 | 1.01 | 2.17 | |

| lisinopril | 1.23 | 1.00 | 1.50 | ||

| metaxalone*,*** | CNS | 1.53 | 1.07 | 2.18 | |

| methylprednisolone | Endocrine and metabolic | 1.44 | 1.02 | 2.03 | |

| Duloxetine (0) | famciclovir | Anti-infective | 1.75 | 1.16 | 2.65 |

| trimethoprim*** | 1.25 | 1.09 | 1.43 | ||

| sulfamethoxazole*** | 1.24 | 1.07 | 1.43 | ||

| levofloxacin*** | 1.19 | 1.03 | 1.37 | ||

| methotrexate | Antineoplastic | 1.35 | 1.09 | 1.68 | |

| hydroxychloroquine | Biologic and immunologic | 1.34 | 1.12 | 1.61 | |

| flurazepam | CNS | 2.54 | 1.35 | 4.79 | |

| valproic acid | 1.82 | 1.10 | 3.03 | ||

| tapentadol*,*** | 1.64 | 1.06 | 2.54 | ||

| metaxalone*,‡,*** | 1.25 | 1.04 | 1.51 | ||

| gabapentin | 1.07 | 1.00 | 1.15 | ||

| liothyronine | Endocrine and metabolic | 1.58 | 1.18 | 2.12 | |

| apixaban† | Hematological | 2.62 | 1.62 | 4.26 | |

| multivitamin with minerals | Nutrients and nutritional | 1.91 | 1.14 | 3.19 | |

| multivitamin prenatal | 1.59 | 1.06 | 2.39 | ||

| levocetirizine | Respiratory | 1.38 | 1.07 | 1.79 | |

| Venlafaxine (0) | proguanil | Anti-infective | 1.81 | 1.11 | 2.95 |

| atovaquone | 1.69 | 1.03 | 2.79 | ||

| isosorbide dinitrate | CV | 1.58 | 1.02 | 2.44 | |

| ramipril | 1.34 | 1.11 | 1.62 | ||

| atorvastatin | 1.09 | 1.01 | 1.17 | ||

| oxymorphone*,*** | CNS | 1.67 | 1.04 | 2.66 | |

| valdecoxib†,*** | 1.55 | 1.18 | 2.06 | ||

| chlordiazepoxide | 1.41 | 1.02 | 1.93 | ||

| etodolac†,‡,*** | 1.36 | 1.08 | 1.71 | ||

| tizanidine*** | 1.25 | 1.10 | 1.43 | ||

| rizatriptan*,** | 1.23 | 1.00 | 1.50 | ||

| metaxalone*,**,*** | 1.22 | 1.01 | 1.46 | ||

| tramadol*,**,*** | 1.11 | 1.02 | 1.22 | ||

| ethynodiol | Endocrine and metabolic | 1.76 | 1.12 | 2.77 | |

| liothyronine | 1.33 | 1.04 | 1.70 | ||

| methylprednisolone | 1.18 | 1.00 | 1.38 | ||

| clidinium | GI | 1.51 | 1.04 | 2.19 | |

| methscopolamine | 1.36 | 1.00 | 1.85 | ||

| cholecalciferol | Nutrients and nutritional | 1.71 | 1.21 | 2.41 | |

| bumetanide | Renal and genitourinary | 1.59 | 1.14 | 2.22 | |

| metolazone | 1.44 | 1.03 | 2.02 | ||

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | |||||

| Citalopram (0) | mebendazole | Anti-infective | 2.45 | 1.15 | 5.20 |

| ampicillin*** | 1.61 | 1.06 | 2.43 | ||

| amantadine | 1.55 | 1.12 | 2.15 | ||

| sulfamethoxazole*** | 1.45 | 1.33 | 1.57 | ||

| trimethoprim*** | 1.43 | 1.32 | 1.55 | ||

| losartan | CV | 1.09 | 1.00 | 1.18 | |

| valproic acid | CNS | 1.51 | 1.01 | 2.25 | |

| pramipexole | 1.37 | 1.15 | 1.63 | ||

| haloperidol*,** | 1.34 | 1.06 | 1.69 | ||

| modafinil | 1.33 | 1.02 | 1.73 | ||

| metaxalone*,‡,*** | 1.25 | 1.04 | 1.49 | ||

| lamotrigine | 1.20 | 1.04 | 1.38 | ||

| sumatriptan*,** | 1.16 | 1.01 | 1.33 | ||

| tramadol*,**,*** | 1.11 | 1.05 | 1.18 | ||

| codeine*,*** | 1.11 | 1.01 | 1.23 | ||

| cyclobenzaprine*,‡,*** | 1.08 | 1.01 | 1.15 | ||

| clonazepam | 1.08 | 1.01 | 1.16 | ||

| lorazepam | 1.08 | 1.01 | 1.15 | ||

| gabapentin | 1.06 | 1.00 | 1.12 | ||

| norgestrel | Endocrine and metabolic | 1.52 | 1.16 | 2.00 | |

| mesalamine | GI | 1.29 | 1.02 | 1.62 | |

| ticagrelor† | Hematological | 2.25 | 1.35 | 3.74 | |

| prasugrel† | 1.50 | 1.02 | 2.20 | ||

| multivitamin | Nutrients and nutritional | 1.36 | 1.02 | 1.80 | |

| omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid | 1.25 | 1.01 | 1.54 | ||

| metolazone | Renal and genitourinary | 1.45 | 1.21 | 1.74 | |

| bumetanide | 1.36 | 1.11 | 1.68 | ||

| Escitalopram (0) | amantadine | Anti-infective | 1.70 | 1.22 | 2.37 |

| sulfamethoxazole*** | 1.21 | 1.09 | 1.34 | ||

| trimethoprim*** | 1.21 | 1.09 | 1.34 | ||

| cyclosporine | Biologic and immunologic | 1.88 | 1.02 | 3.49 | |

| aliskiren | CV | 1.46 | 1.02 | 2.09 | |

| ranolazine* | 1.41 | 1.00 | 1.99 | ||

| terazosin | 1.33 | 1.00 | 1.77 | ||

| losartan | 1.15 | 1.03 | 1.27 | ||

| pramipexole | CNS | 1.30 | 1.07 | 1.58 | |

| aripiprazole* | 1.24 | 1.07 | 1.43 | ||

| carisoprodol*** | 1.20 | 1.05 | 1.38 | ||

| clonazepam | 1.15 | 1.07 | 1.24 | ||

| thyroid desiccated | Endocrine and metabolic | 1.20 | 1.01 | 1.43 | |

| glimepiride | 1.19 | 1.01 | 1.40 | ||

| rabeprazole | GI | 1.16 | 1.02 | 1.32 | |

| omeprazole*,** | 1.07 | 1.01 | 1.14 | ||

| dabigatran† | Hematological | 1.56 | 1.01 | 2.39 | |

| fesoterodine | Renal and genitourinary | 1.46 | 1.02 | 2.09 | |

| tolterodine* | 1.20 | 1.03 | 1.40 | ||

| theophylline | Respiratory | 1.49 | 1.03 | 2.16 | |

| Fluoxetine (1) | ampicillin*** | Anti-infective | 1.69 | 1.05 | 2.72 |

| sulfamethoxazole*,*** | 1.32 | 1.18 | 1.48 | ||

| trimethoprim*,*** | 1.32 | 1.18 | 1.47 | ||

| nitrofurantoin | 1.22 | 1.06 | 1.41 | ||

| azilsartan | CV | 2.28 | 1.07 | 4.83 | |

| carvedilol | 1.13 | 1.00 | 1.29 | ||

| nabumetone†,‡,*** | CNS | 1.25 | 1.05 | 1.50 | |

| divalproex sodium‡ | 1.24 | 1.06 | 1.45 | ||

| carisoprodol*** | 1.16 | 1.02 | 1.32 | ||

| cyclobenzaprine*,**,*** | 1.10 | 1.03 | 1.19 | ||

| budesonide | Endocrine and metabolic | 1.73 | 1.04 | 2.89 | |

| desogestrel | 1.25 | 1.02 | 1.53 | ||

| levothyroxine | 1.10 | 1.04 | 1.16 | ||

| esomeprazole | GI | 1.14 | 1.04 | 1.25 | |

| cilostazol†,‡ | Hematological | 1.70 | 1.09 | 2.65 | |

| clopidogrel†,‡ | 1.17 | 1.05 | 1.31 | ||

| acetazolamide | Renal and genitourinary | 1.74 | 1.16 | 2.62 | |

| solifenacin* | 1.20 | 1.00 | 1.44 | ||

| Furosemide | 1.08 | 1.01 | 1.16 | ||

| Pseudoephedrine | Respiratory | 1.11 | 1.00 | 1.23 | |

| Fluvoxamine (1) | Lisinopril | CV | 1.71 | 1.04 | 2.81 |

| Ezetimibe | 1.62 | 1.06 | 2.48 | ||

| Benztropine | CNS | 2.26 | 1.09 | 4.67 | |

| buspirone** | 1.52 | 1.08 | 2.14 | ||

| esomeprazole‡ | GI | 1.79 | 1.26 | 2.54 | |

| Paroxetine (3) | quinine* | Anti-infective | 1.47 | 1.02 | 2.11 |

| terbinafine** | 1.33 | 1.04 | 1.69 | ||

| sulfamethoxazole*** | 1.22 | 1.07 | 1.38 | ||

| trimethoprim*** | 1.22 | 1.08 | 1.38 | ||

| ciprofloxacin*** | 1.16 | 1.03 | 1.30 | ||

| Methotrexate | Antineoplastic | 1.33 | 1.02 | 1.72 | |

| propafenone* | CV | 1.98 | 1.15 | 3.40 | |

| Primidone | CNS | 1.41 | 1.05 | 1.88 | |

| prochlorperazine | 1.38 | 1.02 | 1.87 | ||

| Eszopiclone | 1.24 | 1.00 | 1.53 | ||

| Lorazepam | 1.14 | 1.05 | 1.25 | ||

| tramadol*,**,*** | 1.09 | 1.00 | 1.19 | ||

| Gabapentin | 1.09 | 1.00 | 1.18 | ||

| Hydrocortisone | Endocrine and metabolic | 1.73 | 1.13 | 2.64 | |

| Sitagliptin | 1.25 | 1.01 | 1.54 | ||

| Omeprazole | GI | 1.11 | 1.04 | 1.19 | |

| multivitamin with iron | Nutrients and nutritional | 1.61 | 1.01 | 2.58 | |

| Sertraline (0) | Valganciclovir | Anti-infective | 2.44 | 1.20 | 4.98 |

| sulfamethoxazole*** | 1.50 | 1.38 | 1.63 | ||

| trimethoprim*** | 1.46 | 1.35 | 1.59 | ||

| levofloxacin*,*** | 1.12 | 1.02 | 1.23 | ||

| Erlotinib | Antineoplastic | 2.37 | 1.19 | 4.74 | |

| mycophenolate mofetil | Biologic and immunologic | 1.50 | 1.06 | 2.12 | |

| nebivolol† | CV | 1.39 | 1.14 | 1.68 | |

| Midodrine | 1.33 | 1.02 | 1.74 | ||

| dexmethylphenidate‡ | CNS | 2.07 | 1.24 | 3.44 | |

| pyridostigmine | 1.98 | 1.13 | 3.47 | ||

| triazolam† | 1.51 | 1.09 | 2.11 | ||

| chlordiazepoxide | 1.32 | 1.00 | 1.74 | ||

| haloperidol†,‡ | 1.29 | 1.02 | 1.63 | ||

| butalbital*** | 1.23 | 1.06 | 1.43 | ||

| Caffeine | 1.22 | 1.05 | 1.42 | ||

| Diazepam | 1.13 | 1.01 | 1.26 | ||

| Temazepam | 1.13 | 1.00 | 1.28 | ||

| tramadol†,**,*** | 1.10 | 1.03 | 1.16 | ||

| alprazolam* | 1.08 | 1.02 | 1.14 | ||

| thyroid desiccated‡ | Endocrine and metabolic | 1.21 | 1.03 | 1.41 | |

| Progesterone | 1.20 | 1.03 | 1.40 | ||

| Megestrol | 1.18 | 1.01 | 1.39 | ||

| dipyridamole† | Hematological | 1.33 | 1.03 | 1.70 | |

| clopidogrel† | 1.13 | 1.05 | 1.22 | ||

| omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid | Nutrients and nutritional | 1.40 | 1.16 | 1.68 | |

| Indapamide | Renal and genitourinary | 1.54 | 1.03 | 2.29 | |

| Mirabegron | 1.48 | 1.12 | 1.97 | ||

| Metolazone | 1.39 | 1.15 | 1.69 | ||

| Tricyclic and related antidepressants | |||||

| Amitriptyline (9) | sulfamethoxazole*,**,*** | Anti-infective | 1.28 | 1.11 | 1.47 |

| trimethoprim*,**,*** | 1.27 | 1.10 | 1.45 | ||

| amiodarone** | CV | 1.76 | 1.36 | 2.27 | |

| Ramipril | 1.52 | 1.13 | 2.03 | ||

| isosorbide mononitrate | 1.30 | 1.05 | 1.62 | ||

| risperidone* | CNS | 1.52 | 1.07 | 2.16 | |

| Lamotrigine | 1.49 | 1.11 | 2.00 | ||

| Lorazepam | 1.17 | 1.01 | 1.34 | ||

| Pregabalin | 1.17 | 1.03 | 1.34 | ||

| Prednisone | Endocrine and metabolic | 1.13 | 1.02 | 1.26 | |

| levothyroxine** | 1.09 | 1.00 | 1.18 | ||

| Esomeprazole | GI | 1.12 | 1.00 | 1.26 | |

| Clopidogrel | Hematological | 1.15 | 1.02 | 1.31 | |

| potassium chloride | Nutrients and nutritional | 1.14 | 1.04 | 1.26 | |

| Darifenacin | Renal and genitourinary | 1.68 | 1.13 | 2.48 | |

| Metolazone | 1.48 | 1.08 | 2.04 | ||

| Desipramine (4) | Atorvastatin | CV | 1.50 | 1.00 | 2.25 |

| Methylprednisolone | Endocrine and metabolic | 1.93 | 1.04 | 3.60 | |

| Doxepin (9) | sulfamethoxazole*,**,*** | Anti-infective | 1.43 | 1.04 | 1.96 |

| trimethoprim*,**,*** | 1.38 | 1.01 | 1.88 | ||

| Memantine | CNS | 2.05 | 1.20 | 3.49 | |

| Diazepam | 1.56 | 1.09 | 2.21 | ||

| Pantoprazole | GI | 1.41 | 1.09 | 1.84 | |

| Imipramine (6) | ondansetron*,** | CNS | 2.15 | 1.22 | 3.80 |

| Omeprazole | GI | 1.39 | 1.05 | 1.85 | |

| Triamterene | Renal and genitourinary | 2.02 | 1.19 | 3.43 | |

| Nortriptyline (3) | sulfamethoxazole*,**,*** | Anti-infective | 1.33 | 1.03 | 1.73 |

| trimethoprim*,**,*** | 1.33 | 1.03 | 1.73 | ||

| ketoprofen†,*** | CNS | 2.96 | 1.48 | 5.91 | |

| oxaprozin†,*** | 1.67 | 1.02 | 2.74 | ||

| Glipizide | Endocrine and metabolic | 1.65 | 1.05 | 2.60 | |

| pioglitazone | 1.65 | 1.07 | 2.53 | ||

| estradiol*,** | 1.50 | 1.08 | 2.07 | ||

| omeprazole | GI | 1.19 | 1.03 | 1.39 | |

| multivitamin with iron | Nutrients and nutritional | 2.55 | 1.14 | 5.67 | |

| silodosin | Renal and genitourinary | 2.28 | 1.16 | 4.51 | |

ASO = anticholinergic activity, sedation, and orthostasis; CV = cardiovascular; CNS = central nervous system; GI = gastrointestinal; RR = rate ratio

Rate ratios > 2.00 are bolded to highlight N = 22 potential signals that may warrant particular attention in future etiologic work.

Categorization of object drugs by severity of anticholinergic activity, sedation, and orthostasis: Within the Facts & Comparisons eAnswers central nervous system agents therapeutic category, we used the antidepressants monograph to categorize object drugs by severity of anticholinergic activity, sedation, and orthostasis. Our rationale for focusing on these adverse effects was their potential relationships with the unintentional traumatic injury outcomes being examined. For each antidepressant, we calculated a composite score by summing numeric severity ratings (0 = none or very low, 1 = low, 2 = moderate, 3 = high) for each of the three adverse effects. Therefore, each antidepressant was assigned a score of zero through nine, with a nine indicating a drug with high severity for anticholinergic activity, sedation, and orthostasis.

drug interaction with impact on object documented in Micromedex

drug interaction with impact on object documented in Facts & Comparisons eAnswers

finding may be particularly affected by protopathic bias

drug interaction with impact on precipitant documented in Micromedex

drug interaction with impact on precipitant documented in Facts & Comparisons eAnswers

Figure 2. Antidepressant + precipitant drug associations with unintentional traumatic injury.

Panel A depicts associations for antidepressants with 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor antagonist properties (nefazodone [N], trazodone [T], vortioxetine [V]). Panel B depicts associations for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (citalopram [C], escitalopram [E], fluoxetine [F], fluvoxamine [Fl], paroxetine [P], sertraline [S], vilazodone [Vi]) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (desvenlafaxine [D], duloxetine [Du], levomilnacipran [L], venlafaxine [Ve]). Panel C depicts associations for other antidepressants (amitriptyline [A], amoxapine [Am], bupropion [B], clomipramine [Cl], desipramine [De], doxepin [Do], imipramine [I], maprotiline [M], mirtazapine [Mi], nortriptyline [No], protriptyline [Pr], trimipramine [Tr]). The x-axis represents the log base 2 semi-Bayes shrunk adjusted rate ratio for antidepressant + precipitant vs. antidepressant. The y-axis represents the log (1 / p-value) for the semi-Bayes shrunk adjusted rate ratio. Data points in the upper right quadrant represent statistically significant elevated semi-Bayes shrunk adjusted rate ratios for the association between antidepressant + precipitant (vs. antidepressant) and unintentional traumatic injury (i.e., putative drug interaction signals). For ease of reading, we limited labeling to upper right quadrant data points with log base 2 semi-Bayes shrunk adjusted rate ratio ≥1 or log (1 / p-value) for the semi-Bayes shrunk adjusted rate ratio ≥10. MVI = multivitamin with iron, SMX = sulfamethoxazole, TMP = trimethoprim.

DISCUSSION

We conducted pharmacoepidemiologic screening of billing data to identify potential antidepressant drug interactions associated with unintentional traumatic injury, a clinical outcome of public health importance. Among nearly 8,000 antidepressant-precipitant pairs, 256 were associated with an increased rate of injury (22 with adjusted rate ratios > 2.00); the plurality of these drug interaction signals involved co-administered CNS drugs. We identified substantially fewer pairs (37 and 1) associated with increased rates of typical hip fracture and motor vehicle crash, respectively. Given our investigation’s high-throughput nature, we consider our findings to be hypothesis generating. Our results may help researchers target limited available resources to assess etiology.

Despite the well-established associations between antidepressants and injury, few studies have examined the role of antidepressant drug interactions. A notable exception includes investigations of antidepressants with benzodiazepines,20–29 although prior work has been limited to injuries of specific anatomical sites and specific causes, and ignored the potential for intraclass variation. Our study yielded many expected results for antidepressant-benzodiazepine combinations, although some had modestly elevated adjusted rate ratios. Concomitant use (vs. antidepressant use alone) was associated with statistically significantly increased injury rates for: short-acting benzodiazepines and related drugs21 (sertraline [adjusted RR = 1.1] and mirtazapine [1.3] with alprazolam; paroxetine with eszopiclone [1.2]; citalopram [1.1], paroxetine [1.1], amitriptyline [1.2], mirtazapine [1.2], and trazodone [1.2] with lorazepam; sertraline with temazepam [1.1]; and sertraline with triazolam [1.5]); and long-acting benzodiazepines21 (sertraline [1.3] and venlafaxine [1.4] with chlordiazepoxide; citalopram [1.1] and escitalopram [1.2] with clonazepam; sertraline [1.1] and doxepin [1.6] with diazepam; and duloxetine with flurazepam [2.5]). For secondary outcomes, although no pairs signaled for motor vehicle crash, concomitant use of venlafaxine with lorazepam [2.1] and citalopram with diazepam [2.3] was associated with a statistically significantly increased rate of typical hip fracture. A case-control study of US long-term care residents reported an odds ratio [OR] = 6.9 for falls among users of antidepressants with a sedative-hypnotic-anxiolytic (vs. OR = 2.6 among users of antidepressants alone).25 A cohort study of US Medicare beneficiaries reported hazard ratios [HRs] for hip fracture among female and male users of SSRI/SNRIs with (4.5 and 7.1) and without (2.3 and 3.0) benzodiazepines, respectively.27 Other observational studies of falls,24 hip fracture,26,28 and motor vehicle crash20 found no associations or did not examine benzodiazepine interaction effects separate from a heterogeneous group of psychoactive drugs.21,30,31

Interactions between antidepressants and benzodiazepines are biologically plausible given additive or synergistic pharmacodynamic (e.g., CNS depression) and/or pharmacokinetic (e.g., hepatic metabolism) effects. As an example of the former, prominent anticholinergic, sedative, and orthostatic effects of doxepin could be compounded by diazepam’s long half-life and debated anticholinergic properties. Our identification of antidepressant-benzodiazepine signals, supported by mechanistic expectations and prior epidemiologic data, bolsters the validity of our drug interaction screening approach. The lack of signaling for some expected pairs (e.g., nefazodone with clonazepam, adjusted rate ratioinjury = 1.3, 0.9–1.9) may be driven by limited statistical precision and suggests that assumptions employed during semi-Bayes shrinkage were appropriately conservative for use in this hypothesis-generating screening context.

Our study also yielded expected results for antidepressants with opioids, although some had modestly elevated adjusted rate ratios. Concomitant use was associated with statistically significantly increased injury rates for: opioid prodrugs (citalopram with codeine [1.1]; and citalopram [1.1], paroxetine [1.1], sertraline [1.1], venlafaxine [1.1], and mirtazapine [1.2] with tramadol); and active parent opioids (nefazodone with meperidine [2.9]; venlafaxine with oxymorphone [1.7]; and duloxetine with tapentadol [1.6]). For secondary outcomes, while no pairs signaled for motor vehicle crash, concomitant use of amitriptyline [1.4], citalopram [1.3], and maprotiline [5.3] with hydrocodone, duloxetine with oxycodone [1.8], and citalopram [1.4] and paroxetine [1.7] with tramadol were associated with a statistically significantly increased rate of typical hip fracture. Potential pharmacokinetic mechanisms (e.g., nefazodone’s inhibition of cytochrome P450 [CYP] 3A4, an isozyme partly responsible for converting meperidine to a nonopioid metabolite) and pharmacodynamic effects (e.g., maprotiline’s potentiation of hydrocodone’s sedative effects) may support these associations. A cohort study of US Medicare beneficiaries reported HRs for hip fracture among female and male users of SSRI/SNRIs with (3.9 and 6.3) and without (2.3 and 3.0) opioids, respectively.27

We also identified signals for antidepressants with muscle relaxants—timely findings given substantial nationwide increases in chronic use of the latter.47 Concomitant use was associated with statistically significantly increased injury rates for: escitalopram [1.2] and fluoxetine [1.2] with carisoprodol; citalopram [1.1], fluoxetine [1.1], and bupropion [1.2] with cyclobenzaprine; venlafaxine [1.2], citalopram [1.3], duloxetine [1.3], and desvenlafaxine [1.5] with metaxalone; and venlafaxine with tizanidine [1.3]. For secondary outcomes, although no pairs signaled for motor vehicle crash, concomitant use of escitalopram with cyclobenzaprine [1.9] was associated with a statistically significantly increased rate of typical hip fracture. Potential pharmacokinetic mechanisms (e.g., duloxetine’s inhibition of CYP2D6, an isozyme that converts metaxalone to an inactive metabolite) and pharmacodynamic effects (e.g., cyclobenzaprine’s augmentation of fluoxetine’s serotonergic effects, potentially causing altered mental status and instability) may support these associations. A cohort study of US Medicare beneficiaries reported a HR for hip fracture among female users of SSRI/SNRIs with (2.9) and without (2.3) muscle relaxants.27

Of other potential drug interaction signals identified, many are biologically plausible. For example, inhibition of CYP3A4 by nefazodone and/or additive or synergistic sedative effects may precipitate the apparent 2.3-fold increase in injury rate when used with quetiapine. Sequelae of serotonin syndrome (e.g., mental status changes, autonomic instability) may explain the apparent 2.2-fold increase in injury rate during concomitant use of imipramine and ondansetron. Such associations, arising from concurrent use of two CNS drugs, may be viewed as unsurprising findings. Yet, we identified numerous plausible signals with concomitant use of non-CNS drugs. As a pharmacokinetic example, inhibition of CYP3A4 by ticagrelor may precipitate the apparent 2.3- increase in injury rate when used with citalopram. As a pharmacodynamic example, the hypotensive effects of tadalafil may precipitate the apparent 2.4-fold increase in injury rate when used with mirtazapine.

For signals that lack an obvious mechanism (e.g., sertraline with dipyridamole), it is especially unclear whether findings reflect unknown mechanisms that place patients at risk of injury, chance, reverse causality, or confounding by indication. Concerns about spurious findings may be especially relevant for precipitants used to treat injuries (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opioids, muscle relaxants) or their sequelae (e.g., anti-infectives). This should be a focus of future work.

Our study has strengths. First, we used a self-controlled case series design—well-suited to drug interaction screening32—to eliminate between-person and decrease within-person confounding. Second, we studied clinically meaningful outcomes identified by well-supported algorithms. Finally, we minimized type I error via semi-Bayes shrinkage.

Our study has limitations. First, drug dispensings may be imperfect markers for drug ingestion. This may be especially true for non-prescription drugs and those taken on an as needed basis. Second, we did not examine higher order drug interactions (e.g., triplets). Such findings may be of future interest given the prevalence of polypharmacy in persons with multiple chronic conditions. Third, we did not examine interactions among persons taking concurrent antidepressants. Fourth, the self-controlled case series design may be susceptible to reverse causality/event dependent exposure. This may be of particular concern for precipitants prescribed to treat early symptoms or sequelae of an injury and may result in a spuriously elevated rate ratio for the precipitant even if concomitant antidepressant + precipitant use had no causal effect on injury. Fifth, our design precluded us from distinguishing a drug interaction from an inherent effect of a precipitant. Sixth, given the hypothesis generating intent of our work, we did not consider injury severity or within-patient changes in depression symptoms or severity; the latter two would be very challenging to directly capture or infer from billing data. Seventh, in addition to the potential for bias and confounding, one must consider the role of chance despite our use of semi-Bayes shrinkage. Finally, our findings may not be generalizable beyond commercially insured and Medicare Advantage ambulatory care populations.

Identifying potential drug interactions resulting in unintentional traumatic injury is a major unmet information need. We used healthcare billing data to screen for antidepressant interactions associated with unintentional traumatic injury, typical hip fracture, and/or motor vehicle crash. Our findings, intended to stimulate future work, provide an evidence-based list of antidepressant interaction signals, such that limited resources can be directed to confirm or refute these potential drug interactions in follow-on etiologic studies.

Supplementary Material

STUDY HIGHLIGHTS.

What is the current knowledge on the topic?

Antidepressant use has been associated with unintentional traumatic injuries. Population-based studies of injury (and sequelae) for drugs used concomitantly with antidepressants have been largely limited to alcohol and class effects of benzodiazepines, opioids, and select anticholinergics.

What question did this study address?

Among beneficiaries of a large United States health insurer, which drugs when used concomitantly with one of twenty-six different antidepressants were associated with an increased rate of unintentional traumatic injury?

What does this study add to our knowledge?

A small proportion (3%), yet large number (N = 256), of antidepressant-precipitant drug pairs were associated with unintentional traumatic injury. The majority of associations were with precipitant drugs outside of the central nervous system class (e.g., anti-infective, endocrine/metabolic, renal/genitourinary agents), most of which have not been previously described yet represent drug interaction signals of potential clinical concern.

How might this change clinical pharmacology or translational science?

Researchers should use our evidence-based list of drug interaction signals to direct limited available resources to confirm or refute these potential interactions in future etiologic studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Ms. Min Du and Ms. Qing Liu for their computer programming support and Dr. Meijia Zhou for sharing Python programming language code to facilitate heat map generation.

Sources of Funding

The United States National Institutes of Health supported this work (R01AG060975, R01DA048001, R01AG064589, and R01AG025152).

Disclosures

Dr. Leonard is an Executive Committee Member of and Dr. Hennessy directs the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for Pharmacoepidemiology Research and Training. The Center receives funds from Pfizer and Sanofi to support pharmacoepidemiology education. Dr. Leonard recently received honoraria from the American College of Clinical Pharmacy Foundation and the University of Florida College of Pharmacy. Dr. Leonard is a Special Government Employee of the United States (US) Food and Drug Administration. Dr. Horn is coauthor and publisher of The Top 100 Drug Interactions: A Guide to Patient Management and a consultant to Urovant Sciences and Seegnal US. Dr. Bilker serves on multiple data safety monitoring boards for Genentech. Dr. Dublin has a pending grant from GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Hennessy has consulted for multiple pharmaceutical companies. All other authors declared no competing interests for this work.

Footnotes

Prior Publication

An abstract summarizing this work was accepted for presentation at the American Society for Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2021 Annual Meeting.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

Supplemental Methods and Refs

Supplemental Tables

Supplemental Figure 1 Panel A

Supplemental Figure 1 Panel B

Supplemental Figure 1 Panel C

Supplemental Figure 2 Panel A

Supplemental Figure 2 Panel B

Supplemental Figure 2 Panel C

Supplemental Figure 3

REFERENCES

- (1).Martin CB, Hales CM, Gu Q & Ogden CL Prescription drug use in the United States, 2005–2016. NCHS Data Brief #344 (2019). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).National Center for Health Statistics. Table 80: Selected prescription drug classes used in the past 30 days, by sex and age: United States, selected years 1988–1994 through 2011–2014. Trend Tables. Health, United States (2016). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/2016/080.pdf. Last accessed: 12/14/2020.

- (3).Tamblyn R, et al. Multinational investigation of fracture risk with antidepressant use by class, drug, and indication. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 68, 1494–1503 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Hill LL, Lauzon VL, Winbrock EL, Li G, Chihuri S & Lee KC Depression, antidepressants and driving safety. Inj. Epidemiol 4, 10-017-0107-x. Epub 2017 Apr 3 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Bloch F, Thibaud M, Dugue B, Breque C, Rigaud AS & Kemoun G Psychotropic drugs and falls in the elderly people: Updated literature review and meta-analysis. J. Aging Health 23, 329–346 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Derijks HJ, Heerdink ER, De Koning FH, Janknegt R, Klungel OH & Egberts AC The association between antidepressant use and hypoglycaemia in diabetic patients: A nested case-control study. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf 17, 336–344 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. WISQARS™—Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (2020). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html. Last accessed: 12/14/2020. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Haagsma JA, et al. The global burden of injury: Incidence, mortality, disability-adjusted life years and time trends from the Global Burden of Disease study 2013. Inj. Prev 22, 3–18 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. WISQARS: Ten leading causes of death, United States. (2018). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/LeadingCauses.html. Last accessed: 12/14/2020.

- (10).Hannan EL, Waller CH, Farrell LS & Rosati C Elderly trauma inpatients in New York State: 1994–1998. J. Trauma 56, 1297–1304 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Trangle M, Gursky J, Haight R, Hardwig J, Hinnenkamp T, Kessler D, Mack N, Myszkowski M. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Adult depression in primary care (2016). Available at: https://www.icsi.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Depr.pdf. Last updated: 03/2016. Last accessed: 12/14/2020. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Work Group on Major Depressive Disorder. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder, 3rd edition. (2010). Available at: https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf. Last accessed: 12/14/2020. [Google Scholar]

- (13).American Psychological Association Guideline Development Panel for the Treatment of Depressive Disorders. Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of depression across three age cohorts. (2019). Available at: https://www.apa.org/depression-guideline/guideline.pdf. Last accessed: 12/14/2020.

- (14).MDD Clinical Practice Review Task Force. Clinical practice review for major depressive disorder. (2016). Available at: https://adaa.org/resources-professionals/practice-guidelines-mdd. Last updated: 11/2020. Last accessed: 12/14/2020.

- (15).Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of major depressive disorder, version 3.0. (2016). Available at: https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/mdd/VADoDMDDCPGFINAL82916.pdf. Last accessed: 12/14/2020.

- (16).O’Connor E, et al. screening for depression in adults: An updated systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, Evidence Synthesis #128. AHRQ Publication No. 14–05208-EF-1 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- (17).United States Senate Special Committee on Aging. Falls prevention: National, state, and local solutions to better support seniors (2019). Available at: https://www.aging.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/307989%20Falls%20Book%20Final.pdf. Last accessed: 12/14/2020.

- (18).National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, LeRoy AA & Morse ML Multiple medications and vehicle crashes: Analysis of databases. DOT HS 810 858 (2008). Available at: https://trid.trb.org/view/863878. Last accessed: 12/14/2020. [Google Scholar]

- (19).National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Drug and alcohol crash risk: A case-control study. DOT HS 812 355 (2016). Available at: https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.dot.gov/files/documents/812355_drugalcoholcrashrisk.pdf. Last accessed: 12/14/2020.

- (20).Orriols L, et al. Risk of injurious road traffic crash after prescription of antidepressants. J. Clin. Psychiatry 73, 1088–1094 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Zint K, Haefeli WE, Glynn RJ, Mogun H, Avorn J & Sturmer T Impact of drug interactions, dosage, and duration of therapy on the risk of hip fracture associated with benzodiazepine use in older adults. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf 19, 1248–1255 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Ray WA, Fought RL & Decker MD Psychoactive drugs and the risk of injurious motor vehicle crashes in elderly drivers. Am. J. Epidemiol 136, 873–883 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Rapoport MJ, Zagorski B, Seitz D, Herrmann N, Molnar F & Redelmeier DA At-fault motor vehicle crash risk in elderly patients treated with antidepressants. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 19, 998–1006 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Gales BJ & Menard SM Relationship between the administration of selected medications and falls in hospitalized elderly patients. Ann. Pharmacother 29, 354–358 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Granek E, et al. Medications and diagnoses in relation to falls in a long-term care facility. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 35, 503–511 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Ray WA, Griffin MR, Schaffner W, Baugh DK & Melton LJ 3rd. Psychotropic drug use and the risk of hip fracture. N. Engl. J. Med 316, 363–369 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Emeny RT, et al. Association of receiving multiple, concurrent fracture-associated drugs with hip fracture risk. JAMA Netw. Open 2, e1915348 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Bolton JM, Metge C, Lix L, Prior H, Sareen J & Leslie WD Fracture risk from psychotropic medications: A population-based analysis. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol 28, 384–391 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Leveille SG, Buchner DM, Koepsell TD, McCloskey LW, Wolf ME & Wagner EH Psychoactive medications and injurious motor vehicle collisions involving older drivers. Epidemiology 5, 591–598 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Weiner DK, Hanlon JT & Studenski SA Effects of central nervous system polypharmacy on falls liability in community-dwelling elderly. Gerontology 44, 217–221 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Thapa PB, Gideon P, Fought RL & Ray WA Psychotropic drugs and risk of recurrent falls in ambulatory nursing home residents. Am. J. Epidemiol 142, 202–211 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Hennessy S, et al. Pharmacoepidemiologic methods for studying the health effects of drug-drug interactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther 99, 92–100 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Han X, Chiang CW, Leonard CE, Bilker WB, Brensinger CM & Hennessy S Biomedical informatics approaches to identifying drug-drug interactions: Application to insulin secretagogues. Epidemiology 28, 459–468 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Bykov K, Schneeweiss S, Glynn RJ, Mittleman MA & Gagne JJ A case-crossover-based screening approach to identifying clinically relevant drug-drug interactions in electronic healthcare data. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther 106, 238–244 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Leonard CE, et al. Clopidogrel drug interactions and serious bleeding: generating real-world evidence via automated high-throughput pharmacoepidemiologic screening. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther 106, 1067–1075 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Pottegard A, dePont Christensen R, Wang SV, Gagne JJ, Larsen TB & Hallas J Pharmacoepidemiological assessment of drug interactions with vitamin K antagonists. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf 23, 1160–1167 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Martin-Perez M, Gaist D, de Abajo FJ & Rodriguez LAG Population impact of drug interactions with warfarin: A real-world data approach. Thromb. Haemost 118, 461–470 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Leonard CE, et al. Screening to identify signals of opioid drug interactions leading to unintentional traumatic injury. Biomed. Pharmacother 130, 110531 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Juurlink DN, Mamdani M, Kopp A, Laupacis A & Redelmeier DA Drug-drug interactions among elderly patients hospitalized for drug toxicity. JAMA 289, 1652–1658 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Schelleman H, Bilker WB, Brensinger CM, Wan F & Hennessy S Anti-infectives and the risk of severe hypoglycemia in users of glipizide or glyburide. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther 88, 214–222 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Douketis JD, Melo M, Bell CM & Mamdani MM Does statin therapy decrease the risk for bleeding in patients who are receiving warfarin? Am. J. Med 120, 369.e9–369.e14 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Sears JM, Bowman SM, Rotert M & Hogg-Johnson S A new method to classify injury severity by diagnosis: Validation using workers’ compensation and trauma registry data. J. Occup. Rehabil 25, 742–751 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Oderda LH, Young JR, Asche CV & Pepper GA Psychotropic-related hip fractures: Meta-analysis of first-generation and second-generation antidepressant and antipsychotic drugs. Ann. Pharmacother 46, 917–928 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Rabenda V, Nicolet D, Beaudart C, Bruyere O & Reginster JY Relationship between use of antidepressants and risk of fractures: A meta-analysis. Osteoporos. Int 24, 121–137 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Yang BR, et al. The association between antidepressant use and deaths from road traffic accidents: A case-crossover study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol 54, 485–495 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Meuleners LB, Duke J, Lee AH, Palamara P, Hildebrand J & Ng JQ Psychoactive medications and crash involvement requiring hospitalization for older drivers: A population-based study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 59, 1575–1580 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Soprano SE, Hennessy S, Bilker WB & Leonard CE Assessment of physician prescribing of muscle relaxants in the United States, 2005–2016. JAMA Netw Open. 3, e207664 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.