Abstract

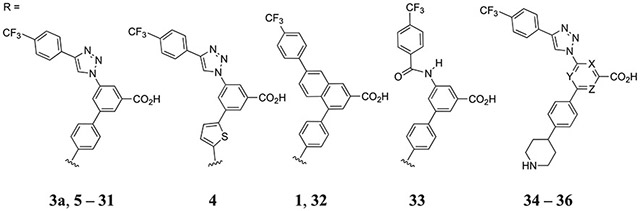

A known zwitterionic, heterocyclic P2Y14R antagonist 3a was substituted with diverse groups on the central phenyl and terminal piperidine moieties, following a computational selection process. The most potent analogues contained an uncharged piperidine bioisostere, prescreened in silico, while an aza-scan (central phenyl ring) reduced P2Y14R affinity. Piperidine amide 11, 3-aminopropynyl 19, and 5-(hydroxymethyl)isoxazol-3-yl) 29 congeners in the triazole series maintained moderate receptor affinity. Adaption of 5-(hydroxymethyl)isoxazol-3-yl gave the most potent naphthalene-containing (32; MRS4654; IC50, 15 nM) and less active phenylamide-containing (33) scaffolds. Thus, a zwitterion was nonessential for receptor binding, and molecular docking and dynamics probed the hydroxymethylisoxazole interaction with extracellular loops. Also, amidomethyl ester prodrugs were explored to reversibly block the conserved carboxylate group to provide neutral analogues, which were cleavable by liver esterase, and in vivo efficacy demonstrated. We have, in stages, converted zwitterionic antagonists into neutral molecules designed to produce potent P2Y14R antagonists for in vivo application.

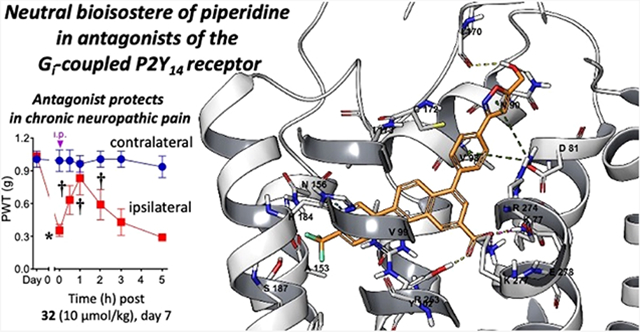

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The P2Y14 receptor (P2Y14R) is a target for the treatment of inflammatory diseases, including pulmonary and renal conditions, and selective P2Y14R antagonists have demonstrated efficacy in animal models of asthma, pain, diabetes, and acute kidney injury.1-8 Its endogenous agonists are uridine-5′-diphosphoglucose (UDPG) and other UDP-sugars, and UDP itself acts as a partial agonist. This Gi protein-coupled receptor is one of three P2Y12R-like receptors in purinergic signaling pathways.9 UDPG acts as damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP), and thus, competitive P2Y14R antagonists have antiinflammatory effects.3 P2Y14R antagonists are considered for the development of new treatments of asthma and peripheral inflammation, although antagonist effects in the CNS are not well characterized and might be detrimental. For example, tonic P2Y14R activation helps to maintain astrocytes by preventing the secretion of matrix metalloproteinase-9.10

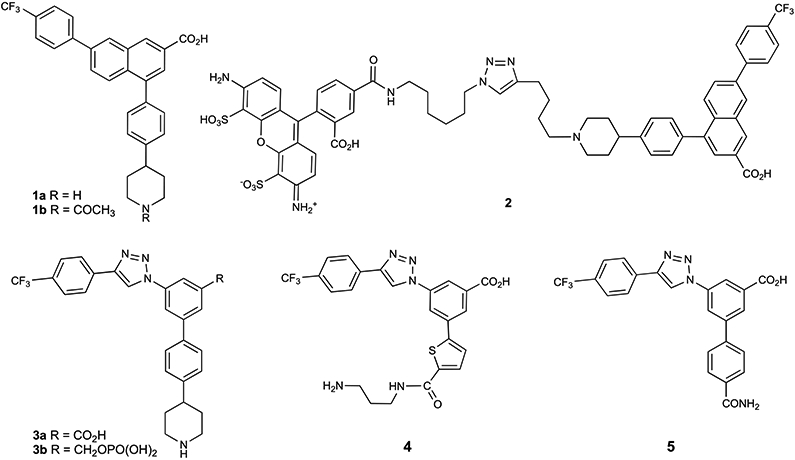

Various P2Y14R antagonists have been reported, and the most well explored class is derived from 7-phenyl-2-naphthalenecarboxylic acid.1,2,11-14. Although there is no report yet of a P2Y14R X-ray crystallographic structure, we have applied a structure-guided approach using homology modeling and molecular dynamics (MD) simulation to the design of new antagonist ligands.1,2,14 The nucleotide agonist-bound P2Y12R structure15 serves as a suitable protein template for P2Y14R homology, with 44% sequence identity between P2Y12R and P2Y14R.1,2,14 Previous studies have analyzed the structure–activity relationship (SAR) of high affinity antagonist 4-[4-(4-piperidinyl)phenyl]-7-[4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-2-naphthalene-carboxylic acid (PPTN, 1a, Chart 1) and its analogues, e.g., potent N-acetyl derivative 1b and triazole derivatives 3a, 4, and 5.1,2,7,11,14,16 Compound 1a is a highly selective antagonist for the P2Y14R among the family of eight P2YRs; this chemical series has no evidence of an interaction with other P2YRs or of residual receptor agonism.16,17 Therefore, we consider this to be a viable, high affinity scaffold for the design of new P2Y14R antagonists. As a screening tool, we previously introduced a high affinity fluorescent antagonist 2, which shows a functional Ki of 80 pM and serves as a versatile screening tool in a flow cytometry assay using Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells overexpressing the human (h) P2Y14R and human embryonic kidney (HEK)293 cells overexpressing the mouse (m) P2Y14R.2,7,16 Consistently reproducible IC50 values can be obtained for newly synthesized antagonists, although these inhibitory constants underestimate the compounds’ affinity by at least one order of magnitude.2

Chart 1. Structure of Reported P2Y14R Antagonist Ligands, Including High Affinity Fluorescent Conjugate 2 Used to Determine Receptor Affinity in a Whole Cell Flow Cytometry Assaya.

aOne of the compounds shown, 3b, was synthesized and characterized in the present study.

However, the prototypical antagonist 1a is not optimal for in vivo administration as it shows a high cLogP and low oral bioavailability (5%, mouse).18 Its hydrophobicity precluded the use of [3H]1a as a radioligand for P2Y14R assays due to high nonspecific binding.2 Furthermore, 1a is a zwitterionic ligand, which affects assessment of its drug-likeness, lipophilicity and absorption in vivo, although various zwitterionic drugs are used therapeutically.19 Previously, we introduced alternative scaffolds to replace the phenyl-naphthalene moiety and substituted the phenyl-piperidine moiety with extended polar chains that reduced the cLogP but did not increase the receptor affinity of 1a and in some cases introduced other liabilities, such as human ether-a-go-go-related gene (hERG) inhibition.1,2,14 One possible solution to overcome the deficiencies of 1a is described in a report on its prodrug derivative in which the essential benzoic acid group was protected as a neutral ester moiety.18 Here, we applied the same prodrug approach that was reported for the prodrug of 1a, by introducing a N,N-dimethylamidomethyl ester at the essential aryl carboxylate group in three high affinity P2Y14R antagonists. We demonstrated that the parent, active drug in each case could be recovered upon treatment of the prodrug form with purified liver esterase in vitro. Furthermore, several prodrug derivatives showed efficacy in a mouse asthma model that surpassed the efficacy of the parent drugs.

Another structural modification of 1a found to lower its hydrophobicity was the bioisosteric replacement of the hydrophobic naphthalene moiety of 1a in the form of a triazolyl-phenyl group, which was the starting point of our SAR study.14 This biaryl moiety is predicted to maintain a similar conformation to the naphthalene when receptor-bound, as we showed previously for moderately potent P2Y14R antagonists 3a, 4, and 5. A further impediment to attaining drug-like properties in this chemical series is the secondary amine in the piperidine moiety. Finding an alternative terminal group in place of piperidine, especially one that lacks a positively charged group, would be desirable and has been attempted in previous SAR reports.1,2 For example, compound 5 provides moderate affinity and enhanced aqueous solubility with a simple 4-carboxamido group in place of piperidine. However, this compound shows rapid clearance in vivo and unacceptable hERG inhibition.2 In this study, we have modified the piperidine moiety and the central phenyl ring of the triazole derivatives to search for alternatives that might be more druglike than reference zwitterionic compounds 1a and 3a. Piperidine bioisosteres were screened by modeling the proposed analogues’ interaction with a P2Y14R model, and the most affinity enhancing group (5-(hydroxymethyl)isoxazol-3-yl) was predicted as a high scoring hit. Subsequently, we combined this neutral bioisostere of piperidine with the naphthalene core. Thus, both structure-based and empirical approaches were followed to probe the P2Y14R SAR.

RESULTS

Computational Selection of Substituent Groups and Initial Chemical Synthesis.

A previously reported hP2Y14R homology model was used to guide scaffold and functional group modification in this antagonist series, featuring a conserved aryl carboxylate on the central ring of the scaffold interacting with three polar side chains in TMs (transmembrane helices) 2, 3, and 7, specifically Lys772.60, Tyr1023.33, and Lys2777.35, respectively.1,14 These interactions were found to be maintained during MD simulation of receptor–antagonist complexes.1,14

Following our earlier SAR studies of heterocyclic P2Y14R antagonists,1,2,14 we turned our attention to the replacement of the piperidine moiety of 3a initially and subsequently of 1a, with diverse groups, including cyclic and acyclic and charged and uncharged moieties. The selection of groups was based both on the commercial availability of functionalized p-substituted phenyl starting materials for the Suzuki coupling (Schemes 1-3) and on computational predictions. We initiated this study with a computational selection of favored p-substituted phenyl derivatives to enable high affinity receptor binding, by varying group “R” in the triazole series related to 3a (Scheme 1). A hP2Y14R homology model,14 based on a nucleotide-bound hP2Y12R15 structure (sequence identity, 44%) and refined with induced fit docking of high affinity antagonist 1a followed by MD simulations, was used for the computational work. A computational screening based on docking and MD simulation of analogues containing the proposed R groups was employed to prioritize the candidate synthesis.

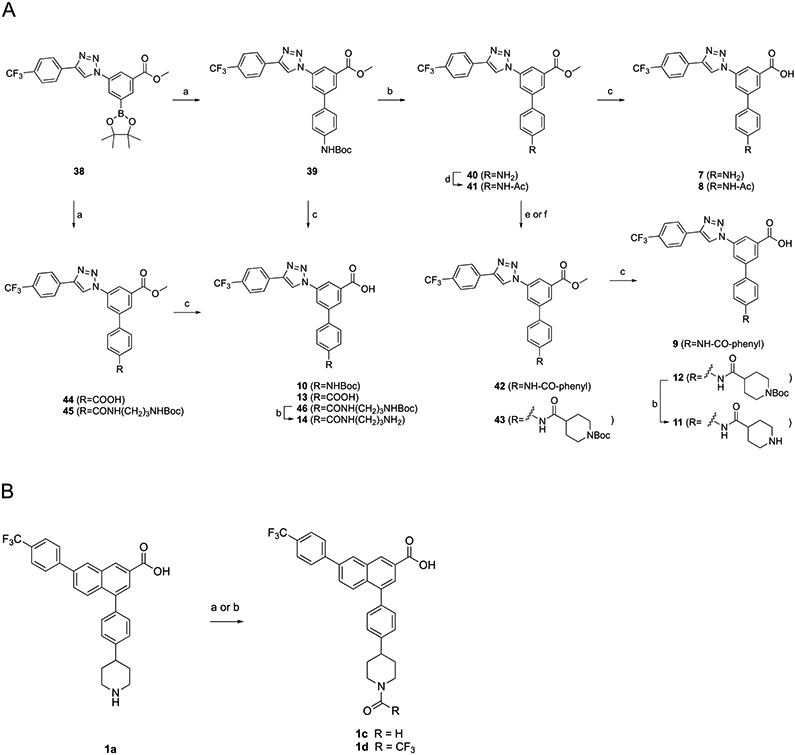

Scheme 1. (A) Synthesis of Triazole-Containing Derivatives with Acyl or Acylamino Replacement of the Piperidine Ring of 3aa.

aReagents and conditions: (a) tert-butyl (4-bromophenyl)carbamate, Pd(PPh3)4, K2CO3, DMF, 85 °C, 5 h, and 40–68%; (b) TFA/THF = 2:1, rt, 0.5 h, and 57–87%; (c) KOH, MeOH/H2O = 2:1, 50 °C, and 50–82%; (d) acetic anhydride, DCM, rt, 2 h, and 76%; (e) benzoyl chloride, TEA, DCM, rt, 18 h, and 63%; and (f) boc-isonipecotic acid (Boc-Inp-OH), HATU, DIPEA, DMF, rt, 2 h, and 94%. (B) Synthesis of N-acyl naphthalene-containing derivatives. reagents and conditions: 1c: (a) Acetic formic anhydride (from Ac2O/formic acid = 2:1, v/v), 0 °C for 3 h → room temperature for 12 h, and 71%. 1d: (b) Trifluoroacetic Anhydride and 92%.

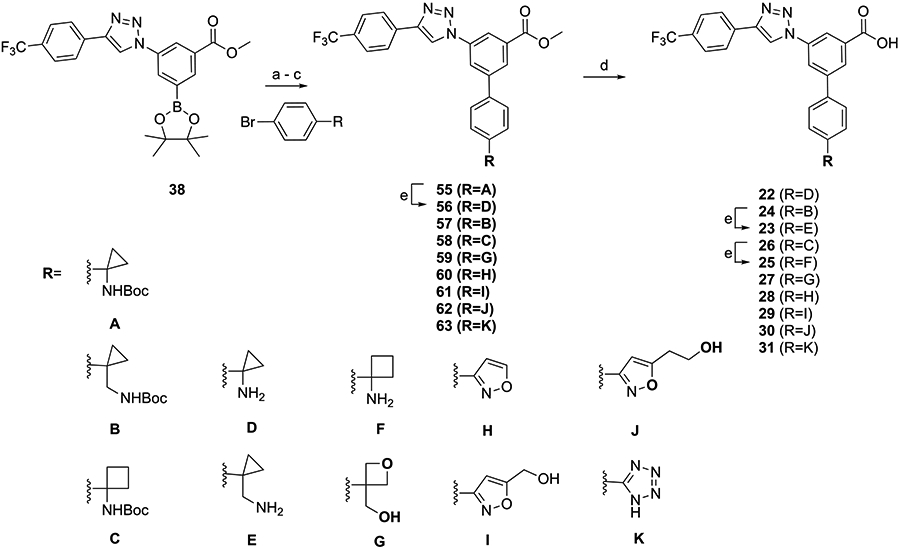

Scheme 3. Synthesis of Triazole-Containing Derivatives with Cyclic Replacement of the Piperidine Ring of 3aa.

aReagents and conditions: (a) Pd(PPh3)4, K2CO3, DMF, 85 °C, 5 h, and 46–91%; (b) Pd(PPh3)4, K2CO3, DMF, μW, 100 °C, 0.5 h, and 80–91%; (c) Pd(PPh3)4, K2CO3, DMF/H2O = 1:1, 90 °C, 12 h, and 30–70%; (d) KOH, MeOH/H2O = 2:1, 50 °C, and 43–74%; and (e) TFA/THF = 2:1, rt, 0.5 h, and 52–90%.

The R groups were selected from a manually assembled list of 20 commercially available bromo-aryl precursors for the Suzuki reaction with intermediate 38 (Scheme 1), together with five compounds that could be easily synthesized using commercial precursors (compounds 8, 9, 11, 14, and 19). The list of 24 screened compounds is reported in Figure S1 (Supporting Information). The azido R group in 93 was discarded and not included in computation and subsequent synthesis because of lack of MD parameters for this substituent. The R groups were incorporated on the antagonist scaffold computationally, the resulting compounds were docked to the receptor structure, and the stability of the receptor-bound complexes was assessed using MD. Three 30 ns MD replicates were run for each complex, and the average results over the three replicates were compared to reference compounds 1a and 3a. With the objective being to account for both enduring geometric and energetic stabilities of the complexes, we employed the weighted dynamic scoring function20 (wDSF) method to evaluate the outcome of the simulations. This method computes the cumulative ligand–receptor energy during the MD simulation (here the sum of electrostatic and van der Waals contributions), which is frame-by-frame weighted by the RMSD of the ligand heavy atoms (eq 1)

| (1) |

The slope of the line fitting the wDSF values versus the number of frames was used to compare the complexes. This scoring system evaluates the enduring strength of the interaction, as previously reported,20 and a lower slope value (higher absolute value) identifies a more stable ligand pose. We used the average slope of 3a over the three MD replicates as cutoff to prioritize the synthesis of our dataset of compounds. In the case of compound 31, whose tetrazole moiety might exist as two possible tautomers, both tautomers were simulated, and the 1H-tetrazole was selected as the one minimizing the wDSF/time slope. Thus, compounds 8, 11, 14, 18, 19, 22, 23, 25, 27, 29, and 31, showing a lower wDSF/time slope as compared to 3a (Table S1, Supporting Information), were selected as best candidates of the series and consequently prioritized for synthesis and testing, followed then by all the other compounds of the series (Table 1). Compound 6 with a piperazine substituent, already synthesized and whose binding affinity was reported to be 233 nM,2 showed a wDSF/time slope lower than 3a. Two compounds reported in Figure S1 have not been synthesized: the synthesis of the hydroxy-oxadiazole-bearing compound 91 was not successful, while compound 92 with the 4-hydroxy-piperidine substituent, selected for its low wDSF/time slope value, was not synthesized because this moiety combined with the naphthoic acid scaffold was previously reported to provide high affinity.58

Table 1.

Inhibition of Fluorescent Antagonist (2) Binding in hP2Y14R-Expressing CHO Cells (X, Y, and Z = CH, Unless Noted)

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Structurea = | IC50, hP2Y14R (nM, mean±SEM) |

cLogPc |

| Archival compounds and close analogues | |||

| 1ab | 7.96±3.5 | 6.18 | |

| 1bb | 27.6±4.3 | 6.47 | |

| 1c | 36.6±10.9 | 5.99 | |

| 1d | 240±21 | 6.70 | |

| 3ab | 31.7±8.0 | 4.64 | |

| 3b | 60,500±6900 | 3.89 | |

| 4b | R-CONH(CH2)3NH2 | 169±42 | 0.84 |

| 5b | R-CONH2 | 269±121 | 3.63 |

| 6b | 233±26 | 3.95 | |

| Phenyl-CO or NH | |||

| 7 | R-NH2 | 1480±160 | 4.03 |

| 8 | R-NH-Ac | 811±95 | 4.07 |

| 9 | R-NH-CO-phenyl | 1860±540 | 5.19 |

| 10 | R-NH-Boc | 3160±310 | 4.98 |

| 11 | 197±29 | 3.85 | |

| 12 | 22,500±3700 | 4.85 | |

| 13 | R-COOH | 632±23 | 3.88 |

| 14 | R-CONH(CH2)3NH2 | 588±43 | 0.92 |

| Phenyl-halo or acyclic | |||

| 15 | R-Br | >10,000 | 4.71 |

| 16 | R-CH2CONH2 | 1290±320 | 3.65 |

| 17 | R-(CH2)2-CN | 17,800±2900 | 4.74 |

| 18 | R-(CH2)3-NH2 | 292±67 | 1.60 |

| 19 | R-C≡CCH2-NH2 | 308±63 | 1.47 |

| 20 | R-(CH2)3-NH-Boc | 42,500±27,000 | 5.37 |

| 21 | R-(CH2)4-OH | 9220±1220 | 4.84 |

| Phenyl-cyclic | |||

| 22 | 14,100±900 | 1.36 | |

| 23 | 8910±750 | 1.57 | |

| 24 | 18,800±2000 | 5.41 | |

| 25 | 2000±180 | 1.70 | |

| 26 | >10,000 | 5.41 | |

| 27 | 2860±440 | 4.73 | |

| 28 | 2230±380 | 4.98 | |

| 29 | 296±13 | 4.44 | |

| 30 | 389±42 | 4.59 | |

| 31 | 895±122 | 3.65 | |

| Alternative scaffolds | |||

| 32 | 15.0±144 | 5.77 | |

| 33 | 7400±1050 | 4.36 | |

| Aza-scan of 3a | |||

| 34 | 1690±280 | 4.16 | |

| 35 | 4900±540 | 4.10 | |

| 36 | 2920±310 | 4.01 | |

The synthetic routes for R group substitution, either according to modeling predictions for bioisosteres or with other substitution, are shown in Schemes 1-Scheme 5 Among the synthesized analogues in the triazole series, the terminal group contained an aryl–CO or aryl–NH linker (7–14), a halogen (15), a carbon-linked acyclic moiety (16–21), or a carbon-linked cyclic moiety (22–31). Scheme 1 shows the synthetic route to triazole analogues containing an aryl–CO or aryl–NH linker (7–14). The Suzuki reaction of 38 with N-(tert-butoxycarbonyl)-4-bromoaniline, 4-bromobenzoic acid, or tert-butyl (3-(4-bromobenzamido)propyl)carbamate yielded 39, 44, and 45, respectively, followed by deprotection reactions (removal of methyl ester and N-Boc protecting groups) to provide 7, 10, 13, and 14. The primary amine of compound 40 was N-acetylated (41), N-benzoylated (42), or coupled with the piperidinyl group (43), and the products were then deprotected to yield 8, 9, 11, and 12. Since the N-acetyl derivative 1b was particularly potent in binding and in vivo efficacy,2,7 we prepared the corresponding N-formyl derivative 1c using reported formylation conditions using acetic formic anhydride21 and N-trifluoroacetyl derivative 1d.

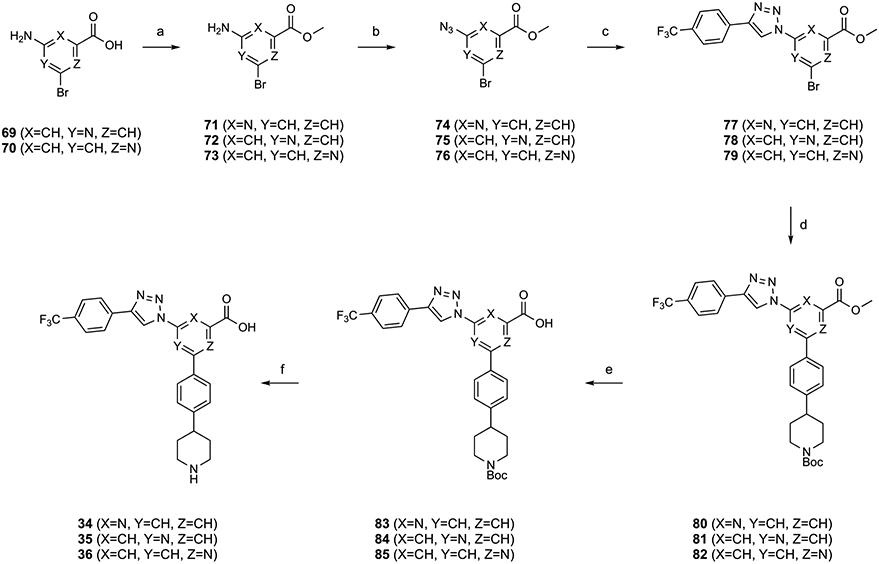

Scheme 5. Synthesis of Triazole-Containing Derivatives 34–36 for the Aza-Scan of the Central Phenyl Ringa.

aReagents and Conditions: (a) SOCl2, MeOH, rt, 15 h, and 40%; (b) tert-butyl nitrite, azidotrimethylsilane, acetonitrile, rt, 1 h, and 37–65%; (c) 4-ethynyl-α,α,α-trifluorotoluene, CuSO4·5H2O, Na ascorbate, TBTA, tert-BuOH/H2O = 1:1, rt, 45 min, and 36–69%; (d) tert-butyl 4-(4-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-2-yl)phenyl)piperidine-1-carboxylate, Pd(PPh3)4, K2CO3, DMF, 85 °C, 4 h, and 35–91%; (e) KOH, MeOH/H2O = 2:1, 50 °C, 5 h, and 68–91%; and (f) TFA/THF = 2:1, rt, 0.5 h, and 60–65%.

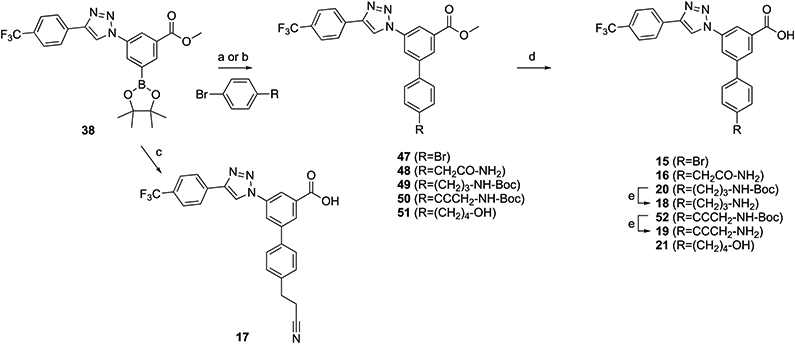

The triazole series containing a halogen (15), a carbon-linked acyclic moiety (16–21), or a carbon-linked cyclic moiety (22–31) was synthesized, as shown in Schemes 2 and 3, to provide 15–31. The Suzuki reaction of 38 with various aryl groups containing a halogen (47), a carbon-linked acyclic moiety (17 and 48–51), or a carbon-linked cyclic moiety (55-63) followed by deprotection reactions provided 15, 16, 18-21, and 22-31.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Triazole-Containing Derivatives with Acyclic Replacement of the Piperidine Ring of 3aa.

aSynthesis of intermediate 54 is in Scheme S1 (Supporting Information). Reagents and conditions: (a) Pd(PPh3)4, K2CO3, DMF, 85 °C, 5 h, and 27–55%; (b) PdCl2(dppf), dimethoxyethane/Na2CO3 (aq, 2 M) = 10:1, 60 °C, 4 h, and 73%; (c) 3-(4-bromophenyl)propanenitrile, Pd(PPh3)4, K2CO3, DMF/H2O = 1:1, 90 °C, 12 h, and 64%; (d) KOH, MeOH/H2O = 2:1, 50 °C, and 39–88%; and (e) TFA/THF = 2:1, rt, 0.5 h, and 62–98%.

Combination of Favored Groups: Extended SAR and Modeling.

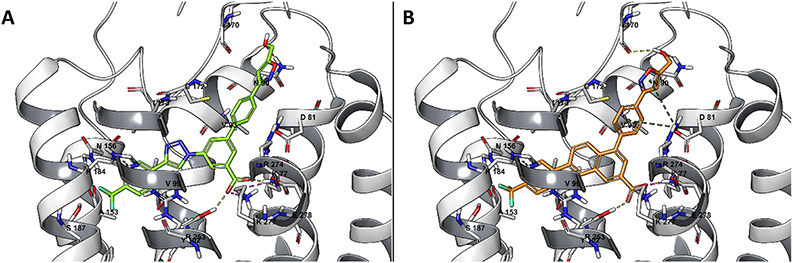

The main success of the computational screening and of the consequent synthetic effort in the triazole series was the identification of a piperidine bioisostere in compound 29, where the removal of the zwitterionic character was compatible with relatively high P2Y14R affinity (IC50, 296 nM). For this reason, we focused on this compound and we report here its hypothetical binding mode. The docking pose of compound 29 (Figure 1) resembles the one previously reported for its piperidine-bearing analogue 3a.1,14 The carboxylate moiety is involved in electrostatic and H bond interactions with Lys772.60, Lys2777.35, and Tyr1023.33. Arg2747.32, Arg2536.55, and His1845.36 (using Ballesteros–Weinstein notation22) are compatible with π–charge and π–π interactions with the p-CF3-phenyl, triazolyl, and peripheral aryl substituents of the central benzoic acid (Figure 1A). During 30 ns MD simulation, the ligand appeared stable (Figure S2A, Supporting Information), with an inter-replicate average RMSD of 2.23 Å (Table S2, Supporting Information). The interaction energy fluctuated slightly around a plateau during the simulations (Figure S2B), with an inter-replicate average value of −207 kcal mol−1. The H bond interactions between the ligand carboxylate moiety and Lys772.60, Tyr1023.33, and Lys2777.35 were endured during the simulations, with an inter-replicate average persistence of about 93, 88, and 77%, respectively. Compound 29 was in contact with 15 residues for more than 95% of the time in all three replicates (Figure S2C). In addition to Lys772.60, Lys2777.35, and Tyr1023.33, the central scaffold was surrounded by Asp812.64, Val933.24, Ala983.29, Val993.30, Cys172EL2, and Phe1915.43. More externally, Gly802.63, Gly832.66, Leu84EL1, Gly85EL1, Asn903.21, and Ile170EL2 surrounded the 5-(hydroxymethyl)isoxazol-3-yl substituent of 29. This particular R group appeared involved in a H bond with Asn903.21 in the docking pose, which was transient during the MD simulations. During the three MD replicates, the 5-(hydroxymethyl)-isoxazol-3-yl group transiently interacted with residues in EL1 and EL2 or on the extracellular tip of TMs, making H bonds especially with Gly85EL1, Asn903.21, and Ile170EL2 (Figure S4A,C,E for the three replicates and Video S1, Supporting Information). The capability of the hydroxymethyl moiety to stabilize the ligand through H bonds supports the binding affinity improvement of compound 29 (5-(hydroxymethyl)isoxazole) as compared to compound 28 (plain isoxazole), which was not included in the list of prioritized compounds (wDSF/time slope lower than compound 3a, Table S1).

Figure 1.

Docking pose of compound 29 (A), in green, and compound 32 (B), in orange, at the P2Y14R structure (gray), obtained by MD-refined homology modeling using an agonist-bound P2Y12R structure (PDB ID: 4PXZ34) as the template.

The piperidine ring substitution with a 5-(hydroxymethyl)-isoxazol-3-yl moiety was thus able to contribute to ligand stabilization with the aforementioned interaction pattern. Given the success of this biososteric group in the initial triazole series, its receptor interactions were analyzed in the context of naphthalene-containing (32) and phenyl-amide-containing (33) scaffolds.2,11 The hypothetical binding mode of compound 32 at the hP2Y14R model (Figure 1B) resembles the pose previously reported for 1a.14 As previously discussed for compound 29, the carboxylate of compound 32 makes H bonds with Lys772.60, Lys2777.35, and Tyr1023.33 that are maintained on average during the three MD replicates for 77, 81, and 62% of the simulation time, respectively (Table S2 and Figure S4B,D,F, Supporting Information). As compared to 29, compound 32 appeared more geometrically stable during the simulations, with small RMSD deviations from a plateau: the inter-replicate average RMSD value was 2.07 Å, with fluctuations within a 1–3 Å range (Table S2 and Figure S3A, Supporting Information). With an inter-replicate average interaction energy of −211 kcal mol−1 and a wDSF/time slope of −100.70 (Table S2, Supporting Information), compound 32 seemed encouraging, and in fact, its affinity for hP2Y14R turned out to be 15 nM, as will be discussed below. In addition to Lys772.60, Lys2777.35, and Tyr1023.33, compound 32 was surrounded by residues Gly802.63, Asp812.64, Gly85EL1, Asn903.21, Val933.24, Cys943.25, Ala983.29, Val993.30, Asn1564.60, Cys172EL2, His1845.36, Ser1875.39, Asn1885.40, Phe1915.43, and Arg2536.55 for more than 95% of the simulation time. A stable H bond was maintained between Gly85EL1 and the hydroxyl group of the 5-(hydroxymethyl)isoxazol-3-yl substituent, especially in replicates 1 and 2 (Figure S4B,D,F, Supporting Information). The isoxazole oxygen and nitrogen atoms transiently interacted with Cys172EL2, bridging interactions between EL1 and EL2 (Video S2, Supporting Information).

The same stability was not reached in the case of compound 33, where the 5-(hydroxymethyl)isoxazol-3-yl substituent was combined to the phenyl-amide-containing scaffold. An average inter-replicate RMSD of 4.53 Å was experienced by the ligand, with huge deviations from the initial state especially in replicate 2 (Table S2 and Figure S5A,E, Supporting Information). The H bond with Lys2777.35 was not conserved during the three replicates, and the interaction with Lys772.60 was lost in replicate 2. The average ligand–receptor interaction energy (−148 kcal mol−1) significantly worsened as compared to compounds 29 and 32, with the 5-(hydroxymethyl)isoxazol-3-yl substituent not making stable contacts with specific residues. The amido group replacing half of the naphthalene scaffold introduced higher flexibility to the molecule, which rotated to interact mainly with Arg2536.55 in replicates 1 and 3, and with His1845.36 in replicate 2, with a general deviation from the initial state and the binding mode of compounds 29 and 32.

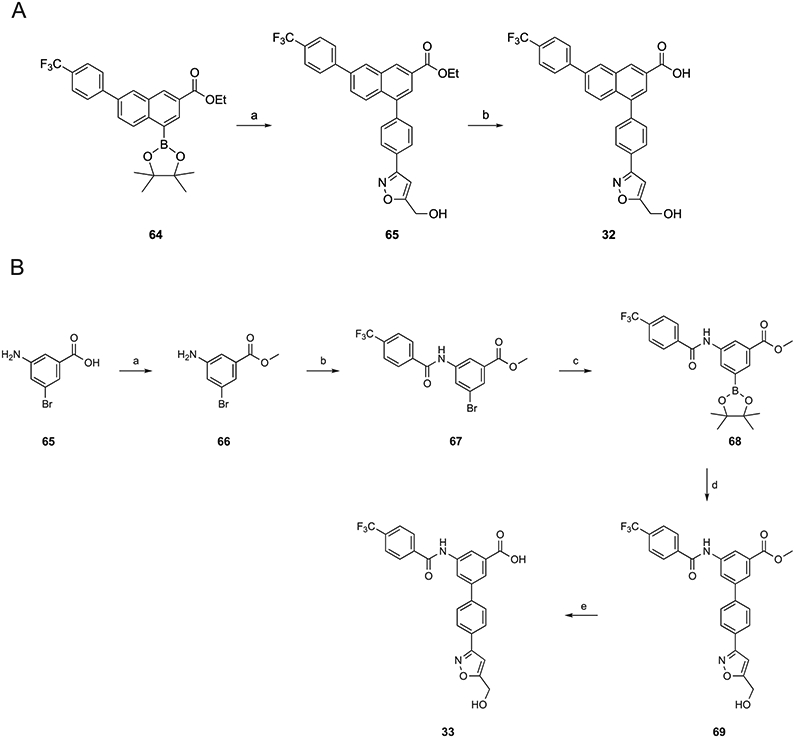

Scheme 4A shows the combination of the 5-(hydroxymethyl)isoxazol-3-yl group of potent derivative 29 with the naphthalene ring of 1a to give compound 32. The Suzuki reaction product of 64 with (3-(4-bromophenyl)-isoxazol-5-yl)methanol was hydrolyzed to yield 32. A 5-(hydroxymethyl)isoxazol-3-yl analogue 33 with an amide group replacing the triazole ring was synthesized, as shown in Scheme 4B. This follows our previous report and that of Zhang et al. on amide incorporation.2,11 For synthesis of amide analogue 33, the carboxylic acid of 65 was converted into a methyl ester in 66, which then coupled with 4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoic acid. Compound 67 reacted with bis(pinacolato)diboron (B2pin2, 68) followed by the Suzuki reaction to yield 69. Subsequently, 69 was hydrolyzed to afford 33.

Scheme 4. (A) Synthesis of Naphthalene-Containing Isoxazole Derivative 32a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) (3-(4-bromophenyl)isoxazol-5-yl)methanol, Pd(PPh3)4, K2CO3, DMF, μW, 100 °C, 1.5 h, and 50% and (b) KOH, MeOH/H2O = 2:1, 50 °C, and 98%. (B) Synthesis of amide-containing isoxazole derivative 33. Reagents and conditions: (a) SOCl2, MeOH, rt, 15 h, and 98%; (b) 4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoic acid, HATU, DIPEA, DMF, rt, 5 h, and 70%; (c) B2pin2, PdCl2(dppf), KOAc, dioxane, 70 °C, 6 h, and 65%; (d) (3-(4-bromophenyl)isoxazol-5-yl)methanol, Pd(PPh3)4, K2CO3, DMF, 85 °C, 5 h, and 45%; and (e) KOH, MeOH, H2O, 50 °C, 3 h, and 62%.

Subsequently, with the aim to further explore modifications of the central scaffold in this antagonist series, we empirically modified the central phenyl ring with nitrogen substitution (“aza-scan”), leading to triazole derivatives 34–36 (Scheme 5), which could be compared to 3a. Adding a ring nitrogen or shifting its position within an aromatic ring is a known approach to modulate the activity of bioactive molecules.23,24

The aza-scan of the central phenyl ring of 3a was accomplished, as shown in Scheme 5. The carboxylic groups of 69 and 70 were protected as methyl esters in 72 and 73. The amine functionality of 71–73 was converted into an azide in 74–76 followed by the click reaction with 4-ethynyl-α,α,α-trifluorotoluene to yield 77–79. Subsequently, a Suzuki reaction with tert-butyl 4-(4-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxa-borolan-2-yl)phenyl)piperidine-1-carboxylate yielded 80–82, which then were deprotected to afford 34–36, respectively.

Since many P2YR ligands contain anionic groups, we wanted to test experimentally if a phosphate monoester could serve the same role as the essential carboxylate of 3a.2,16 Therefore, we synthesized phosphate ester 3b (Scheme S1, Supporting Information) and determined its hP2Y14R affinity. The synthetic route to phosphate derivative 3b began with LAH reduction of the methyl ester of compound 88 to a primary alcohol 89, which was phosphorylated with di-tert-butyl N,N-diethylphosphoramidite to afford 90. Subsequently, a deprotection reaction yielded 3b.

Pharmacological Characterization.

The inhibition by the newly synthesized analogues of binding of fluorescent tracer 2 was measured in hP2Y14R-expressing CHO cells (Table 1).1,2 The computational screening procedure adopted enabled the discrimination of submicromolar ligands, with some false negative and false positive exceptions. In particular, 13 out of 24 compounds showed a wDSF/time slope lower than compound 3a (−70.55), in addition to 1b, compounds 8, 11, 14, 18, 19, 22, 23, 25, 27, 29, and 31 and the piperazine 6 and 4-hydroxy-piperidine 92 compounds (Table S1, Supporting Information). A threshold of 1 μM was used to define positive compounds, and according to this metric, we were able to identify 8 true positives out of the 13 selected compounds: ligands 8, 11, 14, 18, 19, 29, and 31 and the piperazine compound 62 had submicromolar affinity. The compound bearing the 4-hydroxy-piperidine substituent 92 was not part of this study, aimed to explore chemical groups different than piperidine. However, this modification in the naphthoic acid series was associated with high affinity for the chimpanzee P2Y14R.58 Compounds 22, 23, 25, and 27 were false positives (affinity higher than 1 μM), while ligands 13 and 30, whose IC50 turned out to be <1 μM, were missed (false negatives). This screening was not meant to accurately predict a precise ranking of binding affinities. Given the limitations of a structure obtained by homology modeling, we did not expect a perfect correlation between computational and experimental results, but we exploited modeling to drive the synthesis of new compounds, and we were able to identify seven new submicromolar hP2Y14R ligands.

Compounds 1a, 3a, and 4–6 (Table 1) are included as archival compounds for comparison. The N-trifluoroacetyl derivative 1d in the naphthalene series had 8.7-fold lower hP2Y14R affinity than the corresponding N-acetyl 1b, which was similar to the corresponding N-formyl analogue 1c (IC50 ≈ 30 nM). Four aniline and simple acylated aniline derivatives in the triazole series 7–10 had relatively weak affinity (1–3 μM). Two zwitterionic molecules, i.e., piperidine amide 11 and 3-aminopropyl 18 derivatives, and anionic isoxazole 29 were found to maintain moderate receptor affinity with IC50 values ≤300 nM. The N-Boc protected forms of 11 and 18, i.e., 12 and 20, were >100-fold weaker in binding than the parent amines. p-Carboxyphenyl derivative 13 and its amino-propylamide 14 were equipotent (IC50 ≈ 0.6 μM), with 14 having 3.5-fold lower affinity than the corresponding thienyl derivative 4.1 Neutral functional group substitutions of the phenyl ring, 15–17, showed only weak to intermediate affinity. Tetrazole, a common carboxylate bioisostere,1 in compound 31 (IC50 ≈ 0.9 μM) maintained the intermediate affinity of the corresponding carboxylate 13.

Homologues of potent 18 and 29 (unsaturated chain in equipotent 19 and isoxazole derivatives 28 and 30, respectively) were compared. Hydroxybutyl derivative 21 and small cycloalkyl-amino derivatives, 22–26, either Boc-protected or unprotected, and oxetane 27 all bound weakly. The hydroxymethylisoxazole derivative 29 showed higher affinity than its hydroxyethyl homologue 30, and the unsubstituted isoxazole 28 was 7.5-fold weaker than 29. The 5-(hydroxymethyl)isoxazol-3-yl group was incorporated into naphthalene-containing 32 and phenyl-amide-containing 33 scaffolds. Compound 32 proved to be antagonist of the highest hP2Y14R affinity in the present set of compounds with an IC50 of 15 nM. Thus, the restoration of the naphthalene scaffold in 32 increased the affinity by 20-fold, but the phenyl-amide scaffold reduced affinity 25-fold compared to the triazole series.

We turned our attention to the central phenyl ring’s SAR in the triazole series. An aza-scan of this ring indicated reduced P2Y14R affinity of compounds 34–36 in relation to parent 3a. 4-Phenylpicolinic acid derivative 34 had slightly greater affinity than 2-phenylisonicotinic 35 and 6-phenylpicolinic 36 acid derivatives, but the affinities were nevertheless in the μM range. Thus, an aza-scan at any of the three CH positions failed to enhance the affinity (≥53-fold weaker) compared to 3a. Efforts to replace the important carboxylate group of 3a with a different anionic group, i.e., phosphate 3b, greatly reduced affinity. The measured affinity of 3b was 1900-fold weaker (IC50, 60.5 ± 6.9 μM) than 3a. Thus, this carboxylate group that we propose to be buried deeply in the binding site remained an essential requirement for high P2Y14R affinity.

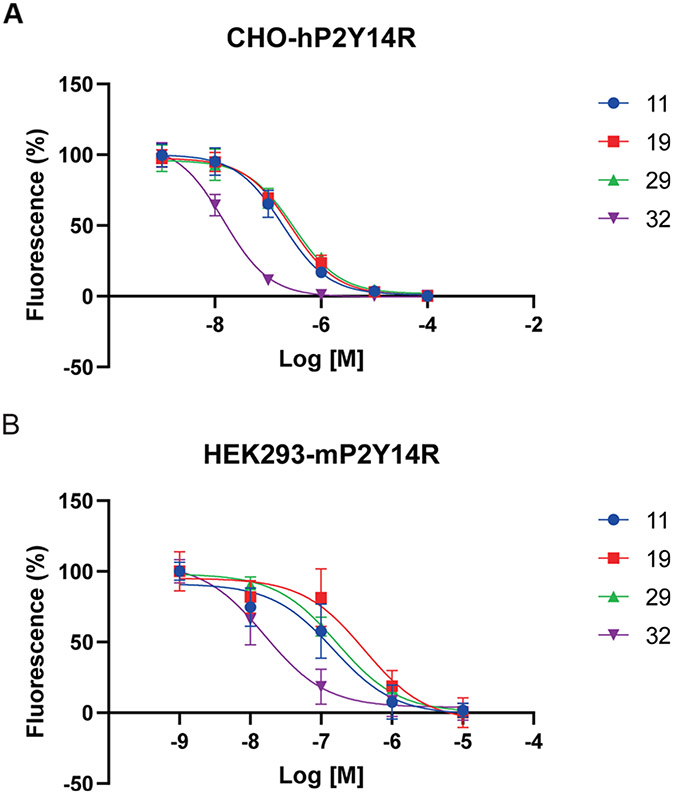

It is important to maintain receptor affinity across species, in order to perform in vivo preclinical testing in small animals, with the mouse being the most commonly used species in initial evaluation.3-7 Therefore, several of the new compounds (11, 19, 29, and 32) were compared in affinity at hP2Y14R and mP2Y14R (Figure 2 and Table 2) using our reported fluorescence binding procedures.2 Compound 29 had slightly enhanced affinity (IC50, 184 nM) at the mP2Y14R versus the human homologue, while 11, 19, and 32 had nearly the same affinity in the two species.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of binding of fluorescent antagonist 2 at hP2Y14R (A) and at mP2Y14R (B) by four novel P2Y14R antagonist analogues (mean ± SD, n = 3–4 independent determinations, performed in triplicate).

Table 2.

Species Dependence of Binding of Various P2Y14R Antagonists, as Determined in a Fluorescent Antagonist Binding Assay in Whole Cells (n = 3–4)c

The solubility (using the pION method)2,25,26 and lipophilicity (based on the HPLC retention time)2,27 were determined for the 5-(hydroxymethyl)isoxazol-3-yl compounds 29 and 32. The aqueous solubility (mean ± SEM) of 29 was 3.72 ± 0.87 μg mL−1 (7.34 μM) at pH 7.4 and 0.60 ± 0.09 μg mL−1 at pH 4.0, and the compound showed a hydrophilicity gain of −1.06 cLogP units compared to 1a. The aqueous solubility values of 32 were 2.43 ± 0.13 μg mL−1 (4.96 μM, pH 7.4) and 0.14 ± 0.02 μg mL−1 (pH 4.0). Potent antagonist 32 showed a hydrophilicity gain of −0.80 cLogP units compared to 1a. It is worth noting that the three prodrugs 37a–37c (Table 3) were readily soluble in DMSO at 20 mg mL−1 as this solvent has been required for the in vivo testing of this chemical series. Reference compound 1a could not dissolve at a concentration of 20 mg mL−1 in DMSO and required the addition of 1 N NaOH (1 equiv) in order to dissolve in DMSO at a near maximal concentration of 5 mM (2.38 mg mL−1).

Table 3.

Properties of Amidomethyl Ester Prodrugs 37a–37ca

| compound (molecular charge, pH 7) |

MW, TPSA (Å2) |

cLogPb | parent drug |

t1/2 (min, mean ± SEM) for esterase cleavagec |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 37a (+1) | 577.2, 86.6 | 4.59 | 3a | 20.2 ± 1.9 |

| 37b (uncharged) | 574.6, 88.4 | 5.65 | 32 | >72 (32.6 ± 0.9%)d |

| 37c (uncharged) | 602.7, 66.9 | 6.27 | 1b | >72 (27.2 ± 0.3%)d |

Structures are shown in Scheme 6.

cLogP calculated using the ALOGPS 2.1 program (www.vcclab.org/lab/alogps/).57

At pH 7.3 in the aqueous medium in the presence of PLE. See Experimental Procedures and Supporting Information (Figures S7-S9) for conditions and graphical representation of results. The prodrugs are stable under the same incubation conditions for 24 h in the absence of PLE.

Percent cleavage at 72 h in parentheses.

Off-target interactions of selected analogues (11, 13, 18, 16, 18, 19, 29–32, 37a, and 37c) were analyzed by radioligand binding at 46 receptors and channels by the Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP, Figure S6, Supporting Information), performed as reported previously.28 Several compounds in this chemical series previously were found to have off-target activity at DOR (δ-opioid receptor, 2.75 μM, 1a).1 Weak off-target interactions were detected, but not extensively (Ki, μM, receptor): 11, 2.33 ± 0.15 (σ1R), 2.0 ± 0.4 (DOR); 16, 0.931 ± 0.388 (σ2R), 2.81 ± 0.18 (TSPO); 29, 2.65 ± 0.74 (H1R), 0.751 ± 0.101 (TSPO), 6.9 ± 1.9 (DOR); 31, 2.26 ± 1.28 (σ2R), 3.30 ± 1.76 (DOR); and 32, 2.68 ± 0.21 (σ1R), 4.78 ± 1.00 (σ2R), 4.63 ± 0.87 (TSPO). Compounds 6, 13, 18, and 19 did not show any off-target interactions in the standard PDSP screen. N-Formyl 1c (% inhibition at 10 μM or Ki, μM: 5HT1D, 81%; α1B, 2.65; α2A, 3.97; α2B, 82%; D1, 0.52; D5, 1.44; σ1, 0.759; σ2, 84%; H4, 1.70) and previously reported7 N-acetyl 1b (5HT1D, 1.75 ± 0.54; 5HT1E, 3.91 ± 0.35; 5HT5A, 2.34 ± 1.25; D1, 1.39 ± 0.12; α1A, 3.14 ± 0.68; α2C, 4.31 ± 0.82; β3, 0.86 ± 0.40; TSPO, 0.508 ± 0.044) analogues showed some off-target interactions. Prodrug 37a was promiscuous in off-target binding, with 18 interactions found in the μM range, while prodrug 37c only inhibited binding at σ2R (0.59 μM).

Absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicology (ADMET) properties were determined for compound 32 (Tables 4 and 5), by the same methods as in Jung et al.2 Moderate inhibition by 32 of CYP2C9 was observed (IC50, 10 μM), but there was no inhibition of four other CYPs. The compound was stable in simulated gastric and intestinal fluids, in plasma of three species, and in human and mouse liver microsomes. However, the half-life in rat microsomes was 48 min. The rat and mouse plasma protein binding of 10 μM 32 was measured as ~100%. High plasma protein binding has been a recurrent disadvantage of this series of P2Y14R antagonists.1,2,23 In vivo pharmacokinetics in the rat (Table 5 and Figure S10, Supporting Information) indicated a high i.p. bioavailabilty, with a much longer half-life than the reference carboxamide 5, and linear systemic exposure with increasing dose. We did not determine oral biovailability of 32 because of the reported low %F of 1a and 5 in this chemical series.1,18 The peak concentration of 32 (10 mg kg−1, i.p., 4 h post-injection) was 786 ng mL−1 (1.61 μM). The clinical signs for all rat groups at all time points (up to 24 h) were normal.

Table 4.

In Vitro and In Vivo ADMET Data for Compound 32 Compared to Known P2Y14R Antagonist 5a

| test | 5b | 32 |

|---|---|---|

| simulated intestinal fluid (t1/2, min) | >240 | >240 |

| simulated gastric fluid (t1/2, min) | >240 | 161 |

| CYP1A2 (IC50, μM) | >30 | >30 |

| CYP2C9 (IC50, μM) | >30 | 10.4 |

| CYP2C19 (IC50, μM) | >30 | >30 |

| CYP2D6 (IC50, μM) | >30 | >30 |

| CYP3A4 (IC50, μM) | >30 | >30 |

| plasma stability (species)c (t1/2, min) | >240 (h), >240 (r), >240 (m) | >240 (r), >240 (m) |

| microsomal stability (t1/2, min) | 145 (m), 108 (r), 145 (h) | >240 (h), 47.7 (r), >240 (m) |

| hERG, IC50 (μM)d | 0.166 (fluorescent) | >30 (patch clamp) |

| HepG2 cell toxicity, IC50 μM) | >30 | 8.47 |

| t1/2 (r)e | 0.20 (0.5 mg kg −1, i.v.) | 7.23 (1.0 mg kg−1, i.p.) |

| aqueous solubilityf (pH 7.4, μg mL−1) | 138 ± 4 | 7.63 ± 1.93 |

| aqueous solubilityf (pH 4.0, μg mL−1) | NDg | 0.14 ± 0.02 |

Procedures are in the Supporting Information and in Yu et al.1 Dosing formulation: for i.v., DMSO/20% 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodetrin (Sigma-Aldrich, 10:90); for i.p., DMSO/Kolliphor EL (Sigma-Aldrich)/PBS (15:15:70).

Data determined by Yu et al.1

Species tested for plasma stability were human, rat, and mouse; species as indicated for microsomal stability.

Method noted in parentheses.

By administration in rat (plasma half-life, h). See Table 5 for complete results for 32.

Mean ± SD, pION method.

ND, not determined.

Table 5.

Pharmacokinetic Parametersa for Compound 32 Administered by Intravenous and Intraperitoneal Routes

| dose (mg kg−1) |

Cmax (ng mL−1) |

Tmax (h) |

AUC0-last (h ng mL−1) |

AUC0-∞ (h ng mL−1) |

t1/2 (h) | MRTlast (h) |

Vd (mL kg−1) |

Kel (1 h−1) |

F (%) |

Cl (mL h−1 kg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5, i.v. | 359 | 0.083 | 234 | 238 | 0.689 | 0.703 | 2090 | 1.01 | 100 | 2110 |

| 1.0, i.p. | 88.4 | 2.0 | 650 | 700 | 7.23 | 6.24 | 14,900 | 0.096 | 139 | 1430 |

| 3.0, i.p. | 315 | 2.0 | 2060 | 2120 | 4.68 | 5.68 | 9570 | 0.148 | 147 | 1420 |

| 10, i.p. | 786 | 4.0 | 4900 | 4920 | 2.98 | 5.02 | 8730 | 0.233 | 105 | 2030 |

In healthy adult male Wistar rats; with 3 per group. Dosing formulation: for i.v., DMSO/20% 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodetrin (Sigma-Aldrich, 10:90); for i.p., DMSO/Kolliphor EL (Sigma-Aldrich)/PBS (15:15:70). Abbreviations: Cmax, maximal concentration; Tmax, time at which maximal concentration observed; AUC0-last, area under the plasma drug concentration–time curve up to the last quantifiable time point; AUC0-∞, area under the plasma drug concentration–time curve to infinite time; T1/2, terminal half-life; MRTlast, mean residence time; Vd, volume of distribution; Kel, elimination rate constant; F, biovailability; and Cl, total body clearance.

Carboxamide analogue 5 was previously shown to potently inhibit hERG (Table 4). hERG inhibition was determined by two methods (fluorescence and electrophysiological)29,30 as have been done for other P2Y14R antagonists.2 The fluorescence assay utilized a commercial hERG binding fluorescence polarization assay with a tetramethyl-6-carbox-yrhodamine (TAMRA) fluorophore.30 This fluorescence method indicated an IC50 of >30 μM for the novel antagonist 32. Also, compounds 1a, 1b, and 32 were measured using a patch clamp assay with CHO cells expressing the full length hERG protein, by measuring the block of hERG outward current amplitude (Supporting Information).29 By this electro-physiological method, compounds 1a and 32 did not inhibit hERG (IC50 or EC50, >30 μM), while compound 1b showed a slight activation at high concentrations (EC50, 16.0 μM). Thus, an improvement in the hERG liability was demonstrated for the bioisostere-containing compound 32.

Prodrug Synthesis and Cleavage by Liver Esterases.

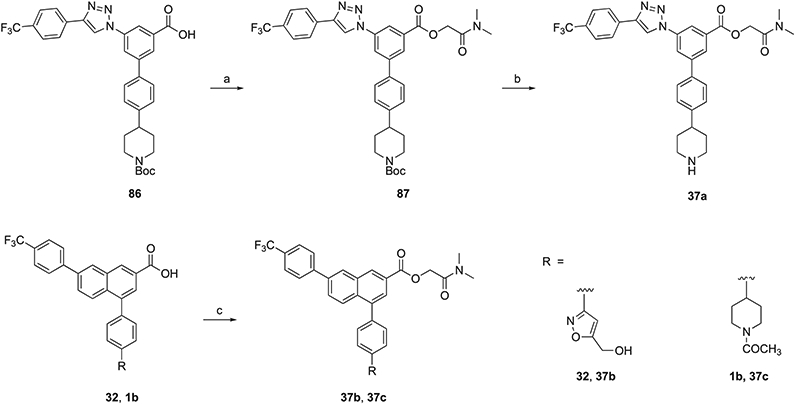

Following the lead of Robichaud et al.18 with the report of a N,N-dimethylamidomethyl ester prodrug of potent zwitter-ionic antagonist 1a, prodrug derivatives of novel, potent P2Y14R antagonists were synthesized. Fully uncharged prodrug derivative of the 5-(hydroxymethyl)isoxazol-3-yl derivative 32, the potent bioisostere of the piperidine moiety, was synthesized in the naphthalene series (37b). Also, the prodrug 37c derived similarly from N-acetyl derivative 1b is fully uncharged. For comparison, we also applied the same prodrug derivatization to reference triazole derivative 3a to provide the cationic molecule 37a. Scheme 6 shows the preparation of prodrugs (37a– 37c) having a N,N-dimethylamidomethyl ester as a promoiety. The Boc-protected piperidine 86, 5-(hydroxymethyl)isoxazol-3-yl derivative 32, and N-acetyl derivative 1b were utilized for esterifying the free carboxylic acid using 2-chloro-N,N-dimethylacetamide in the presence of K2CO3 or Cs2CO3 as the base to provide 87, 37b, and 37c, respectively. Subsequently, the deprotection reaction of the Boc group of 87 yielded 37a.

Scheme 6. Synthesis of Prodrug Derivatives 37a–37ca.

aReagents and conditions: (a) 2-chloro-N,N-dimethylacetamide, K2CO3, DMF, 45 °C, 1 h, and 70–72%; (b) TFA/THF = 2:1, rt, 0.5 h, and 78%; and (c) 2-chloro-N,N-dimethylacetamide, Cs2CO3, DMF, 45 °C, 1 h, and 68–72%.

As an in vitro model system for studying the relative cleavage rates of the ester prodrugs, we used porcine liver esterase (PLE).31 The prodrug derivatives 37a–37c were shown to regenerate the corresponding parent drugs, 3a, 32, and 1b, respectively, upon incubation with PLE (Table 3 and Figures S7-S9, Supporting Information). The triazole-containing prodrug 37a was the most rapidly cleaved, while the naphthalene-containing prodrugs 37b and 37c did not reach 50% cleavage after 72 h at 37 °C. All of the prodrugs were stable for 24 h upon aqueous incubation in the absence of PLE.

In Vivo Efficacy of Novel P2Y14R Antagonist 32.

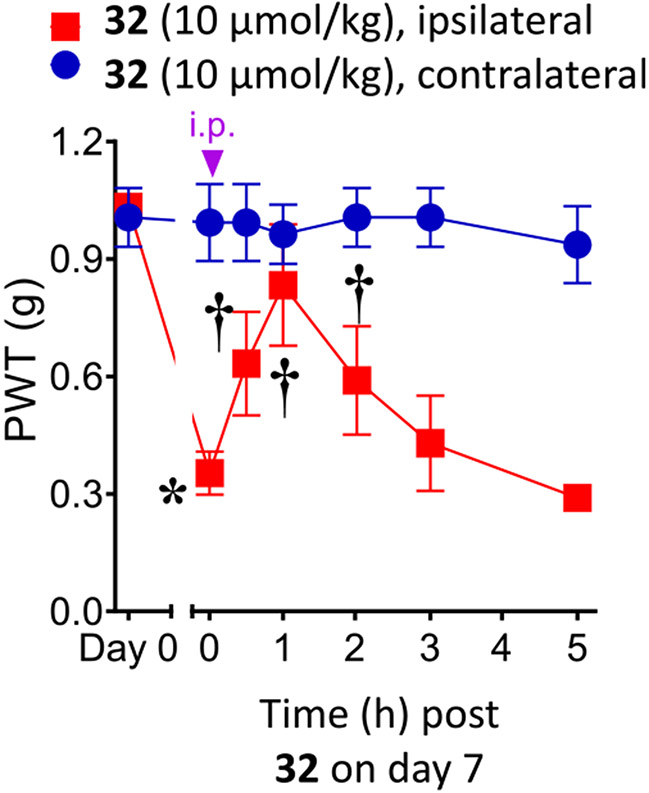

We first tested the potent 5-(hydroxymethyl)isoxazol-3-yl derivative 32 in a well-established mouse model of neuropathic pain caused by chronic constriction of the sciatic nerve (CCI)32 at a dose of 10 μmol kg−1 (4.9 mg kg−1, i.p., Figure 3). Previously, we demonstrated that 1a, 1b, and 3a and other P2Y14R antagonists of this series were effective in reducing chronic pain in this model and reached full reversal in some cases (Table S3, Supporting Information).2,7 A maximal 71.0 ± 17.4% reversal of CCI-induced mechano-allodynia was observed 1 h post-injection of 32, and the degree of protection declined during the following 2 h and was not statistically significant at 3 or 5 h. No side effects were evident at this dose.

Figure 3.

Reversal of CCI-induced mechano-allodynia in the mouse induced by compound 32 (10 μmol kg−1, i.p.). Mean ± SD is shown, n = 3; ANOVA, *P < 0.05 vs day 0 and †P < 0.05 vs day 7 post-injury. 32 was dissolved in 5% DMSO in water as a vehicle, and a volume of 0.2 mL was injected.

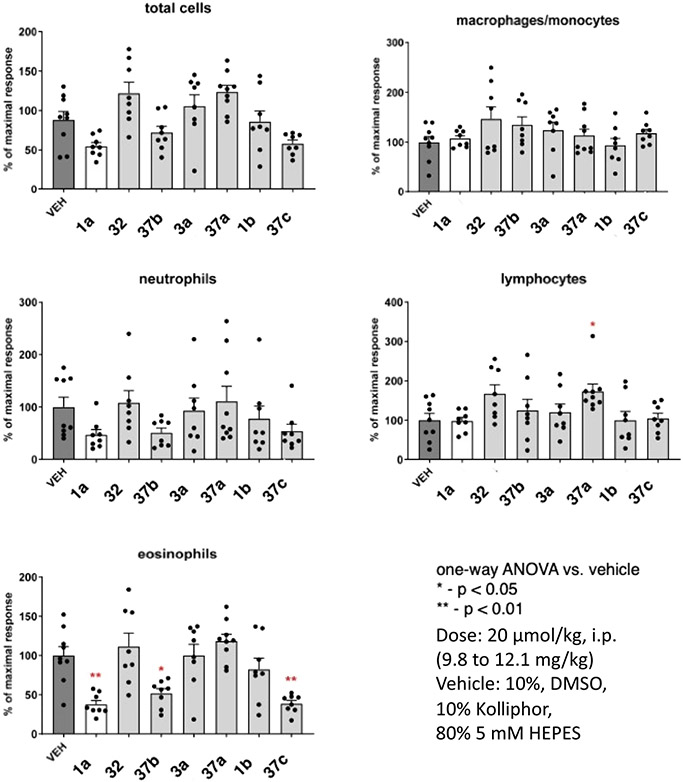

Selected compounds were examined for their ability to reduce eosinophils in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) in an ovalbumin/Aspergillus mouse asthma model.2,17,33 Compounds 1a, 1b, 3a, and 32 (10 mg kg−1) were administered prior to allergen challenge at a dose of 20 μmol kg−1, i.p. Airway inflammation was determined 2 days post-challenge (Figure 4). Also, the corresponding prodrug derivatives 37a–37c of triazole 3a, 5-(hydroxymethyl)-isoxazole 32, and N-acetyl-piperidine 1b derivatives, respectively, were administered at the same dose. Eosinophil counts in the BALF were reduced following administration of reference antagonist 1a or several of the prodrugs. In fact, 37b and 37c significantly reduced eosinophils to a greater extent than the parent antagonists, which showed no significant reduction. Other immune cells showed no significant effect, except the lymphocyte count following administration of prodrug 37a trended higher than in a vehicle control.

Figure 4.

Effects of P2Y14R antagonists and their prodrugs, compared to reference antagonist 1a, during allergen challenge reduce eosinophilic airway inflammation in the protease model of asthma. Effect on BALF leukocytes of i.p. injection of the P2Y14R antagonists 2 days post-challenge of ASP/OVA-sensitized mice. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 vs vehicle by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test.

DISCUSSION

This study has been guided by insights from P2Y14R molecular modeling. The potent analogues 29 and 32 contained an uncharged piperidine bioisostere, which was among the hits selected using in silico prescreening. The hypothetical receptor interactions of the favored 5-(hydroxymethyl)isoxazol-3-yl moiety were analyzed by subsequent docking and MD simulations. Although the piperidine-amide derivative 11 in the triazole series showed comparable affinity to 29, it was poorly soluble in aqueous medium, and we did not prepare the corresponding naphthalene derivative.

We have sought to increase the druglikeness34 of this chemical series of potent P2Y14R antagonists. Through SAR exploration, we have, in stages, removed the zwitterionic character of the widely used antagonist 1a. We have identified the uncharged 5-(hydroxymethyl)isoxazol-3-yl substituent in compounds 29 and 32 as a piperidine bioisostere in the P2Y14R binding site. The discovery of potent antagonist 32 having the preferred naphthalene scaffold and active in vivo in a chronic pain model greatly improved the unacceptable hERG activity of a previously reported non-amino containing carboxamide 5, but it showed high plasma protein binding. Another concern was that isoxazole rings have been reported to be susceptible to ring opening biotransformations, although many experimental drugs, even some approved drugs (sulfisoxazole, risperidone, and leflunomide), contain this moiety.35,36 For example, an isoxazole moiety was found to be beneficial in a series of antinociceptive σ1R antagonists.37 The high microsomal stability and in vivo rat pharmacokinetics of compound 32 indicated that it is not rapidly metabolized. Nevertheless, it will be useful to further study the in vivo metabolism of 29 and 32.

Affinity differences between two species, human and mouse, are not a major concern for this compound class.2 In the more potent naphthalene series, compound 32 showed IC50 values of 15 and 19 nM at the hP2Y14R and mP2Y14R, respectively, which are similar to the affinity of compound 1a. This chemically neutral substituent allowed us to prepare a completely neutral prodrug derivative 37b, which was shown to be cleaved with liver esterase to regenerate the active drug 32. Although we determined the relative parent drug recovery in all three cases after ester cleavage catalyzed by liver esterase, this model system cannot be used to predict the cleavage kinetics in vivo for a given route of administration. There are multiple esterases present in the plasma, stomach, intestines, and other organs, which would also be expected to catalyze this cleavage. Interspecies differences would also apply to generalizing the in vitro results to the in vivo biotransformation.38

The activity of 32 in a mouse model of chronic neuropathic pain establishes the ability of this bioisosteric approach to discover P2Y14R antagonists with substantial in vivo efficacy. However, it is to be noted that at the dose of 10 μmol kg−1, the reversal of mechano-allodynia was less prolonged or efficacious than with 1a or 1b.7

The lack of in vivo activity of the prodrug 37a in the protease model of murine asthma might be a result of its relatively rapid enzymatic cleavage to 3a, which itself was inactive in the same in vivo assay. Thus, the prodrug 37a might be largely cleaved prior to reaching the site of action. The other prodrugs 37b and 37c were highly efficacious in the asthma assay and were more slowly cleaved to the active drugs in the model esterase system. The correlation of slower ester cleavage with the naphthalene scaffold suggests that these esters might be more sterically hindered than the triazole 37a in the esterase active site to attenuate hydrolysis. The higher in vivo efficacy might also be related to 37b and 37c both being neutral molecules as the lack of a formal charge could promote their distribution/diffusion to the site of action followed by cleavage to the active parent drug. However, additional pharmacokinetic studies of the prodrugs are needed in order to point to a mechanism for the differential activities.

CONCLUSIONS

In a structure-guided approach, we systematically replaced the piperidine and central phenyl groups of P2Y14R antagonist 3a with diverse groups. A computational selection process provided a priority list for the initial synthetic foray. A suitable bioisostere for the piperidine moiety was identified as the 5-(hydroxymethyl)isoxazol-3-yl group, which was transferred from the triazole-containing scaffold of 3a to the naphthalene series to provide 32 with high affinity at both hP2Y14R and mP2Y14R. However, an empirical aza-scan of the central phenyl ring of 3a was unsuccessful in maintaining affinity.

Thus, a zwitterion was nonessential for receptor binding, which was probed through docking and MD simulation. Also, a reported N,N-dimethylamidomethyl ester prodrug moiety was used to reversibly block the conserved carboxylate group to provide neutral analogues, which were proven cleavable by liver esterase. We have, in stages, converted zwitterionic antagonists into neutral molecules that are designed to produce potent P2Y14R antagonists for in vivo application. Among the analogues derivatized as prodrugs are the novel and potent compound 32 containing a neutral bioisostere of the piperidine group present in reference antagonist 1a. The resulting prodrug 37b and N-acetyl derivative 37c showed substantial efficacy in a protease mouse model of allergic asthma, which surpassed the parent drugs’ efficacy. Thus, by searching for piperidine bioisosteres and applying a prodrug strategy, we have, in stages, arrived at novel, tractable P2Y14R antagonists for in vivo studies. Thus, by using insights into the drug–receptor interaction, we have expanded this heterocyclic class of potent P2Y14R antagonists, which hold promise for treating a range of inflammatory diseases.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Molecular Modeling.

Molecular Docking.

A previously published model of hP2Y14R14 was employed in this study. The structure was obtained by homology modeling using an agonist-bound hP2Y12R X-ray structure (PDB ID: 4PXZ15) as a template and then refined through induced fit docking of the antagonist 1a and MD simulations of the complex. The Schrödinger suite (Maestro 2020-1)39 was used for general modeling operations, like protein preparation through the Protein Preparation Wizard40 tool and drawing and minimization of the compounds using the OPLS3 force field.41 All His residues were protonated at the Nδ nitrogen (designated HSD in the CHARMM nomenclature).

Docking was performed with Glide SP,42 employing a grid centered on the previously published pose of the antagonist 1a, with an inner box of 10 Å and an outer box of 30 Å. Maximum 20 poses were generated for each compound, and a post-docking minimization was included. One pose was selected for each compound by visual inspection, considering the presence of interactions with Lys772.60, Y1023.33, and K2777.35, similarly to the previously published 1a binding mode.

Molecular Dynamics.

The complexes between hP2Y14R and each compound were prepared for MD simulations using the HTMD43 module and then inserted in a 90 Å × 90 Å 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) lipid bilayer generated through the VMD Membrane Plugin,44 according to the orientation provided by the Positioning of Proteins in Membrane (PPM)45 web server. TIP3P46 water molecules were added to the systems (with a positive and negative padding of 15 Å on the z axis), which were then neutralized by Na+/Cl− counterions at a concentration of 0.154 M.

The MD simulations were carried out with ACEMD47 as a molecular dynamics engine. The CHARMM3648,49 force field was employed for proteins, lipids, water, and ions and the CGenFF50,51 force field for the ligands, with assignment of missing parameters by analogy through the ParamChem52 web service.

The systems were minimized (5000 conjugate gradient steps) and then submitted to an equilibration stage of 40 ns MD simulation in the NPT ensemble, applying positional harmonic restraints to ligand and protein atoms (0.8 kcal mol−1 Å−2 for ligand atoms, 0.85 kcal mol−1 Å−2 for Cα carbon atoms, and 0.4 kcal mol−1 Å−2 for the other protein atoms) that were linearly reduced after 20 ns. Three 30 ns replicates of MD simulations were run in the NVT ensemble, starting from the equilibrated system. A pressure around 1 atm was maintained by a Berendsen barostat (relaxation time, 800 fs) during the equilibration, and a temperature of about 310 K was kept by a Langevin thermostat (damping constants of 1 and 0.1 ps−1 for equilibration and production, respectively). The time step was set to 2 fs, and the hydrogen-containing bonds were constrained by the M-SHAKE53 algorithm. A 9 Å nonbonded interaction cutoff and a 7.5 Å switching distance were employed, and long-range electrostatic interactions beyond the cutoff were computed with the particle mesh Ewald (PME)54 method (1 Å grid spacing). All the simulations were run on NVIDIA Tesla P100 GPUs of the NIH HPC Biowulf cluster.

Molecular Dynamics Analysis.

The MD trajectories were analyzed with an in-house script written in Tcl, employing VMD 1.9.3.44 The complexes were aligned to their initial conformation by superposition of the protein Cα carbon atoms. H bonds were estimated using the VMD Hbonds plugin, using a donor–acceptor distance of 3.5 Å and a donor–H–acceptor angle of 30°. Ligand–protein electrostatic and van der Waals interactions were computed with NAMD.55 The data were plotted using gnuplot56 (version 5.0) software. The weighted dynamic scoring function (wDSF) was computed with a python3 script, employing Pandas and SciPy for the linear fitting of the points and slope computation. Frames every 100 ps were taken into account for the wDSF analysis.

Chemical Synthesis.

Reagents and Instrumentation.

All reagents and solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), Enamine, Ltd. (Monmouth Jct., NJ; compound 69), Alchem Pharmtech, Inc. (Monmouth Jct., NJ; compound 70), or ChemScene, LLC (Monmouth Jct., NJ; compound 71) unless noted. 1H NMR spectra were obtained with a Bruker 400 spectrometer using CDCl3, CD3OD, and DMSO-d6 as solvents. Chemical shifts are expressed in δ values (ppm) with tetramethylsilane (δ 0.00) for CDCl3 and water (δ 3.30) for CD3OD. NMR spectra were collected with a Bruker AV spectrometer equipped with a z-gradient [1H,13C,15N]-cryoprobe. TLC analysis was carried out on glass sheets precoated with silica gel F254 (0.2 mm) from Sigma-Aldrich. The purity of final compounds was checked using an Agilent 1260 Infinity HPLC equipped with an Agilent Eclipse 5 μm XDB-C18 analytical column (250 × 4.6 mm; Agilent Technologies Inc.; Palo Alto, CA). Mobile phase: linear gradient solvent system, 10 mM triethylammonium acetate/CH3CN from 95:5 to 5:95 in 20 min or CH3CN/0.1% formic acid and 5% methanol in water from 30:70 to 55:45 in 20 min; the flow rate was 1.0 mL min−1. Peaks were detected by UV absorption with a diode array detector at 210, 254, and 280 nm. All derivatives tested for biological activity showed >95% purity by HPLC analysis (detection at 254 nm). Low-resolution mass spectrometry was performed with a JEOL SX102 spectrometer with 6 kV Xe atoms following desorption from a glycerol matrix or on an Agilent LC/MS 1100 MSD, with a Waters (Milford, MA) Atlantis C18 column. High-resolution mass spectroscopic (HRMS) measurements were performed on a proteomics optimized Q-TOF-2 (MicromassWaters) using external calibration with polyalanine, unless noted. Observed mass accuracies are those expected based on known instrument performance as well as trends in masses of standard compounds observed at intervals during the series of measurements. Reported masses are observed masses uncorrected for this time-dependent drift in mass accuracy. tPSA (total polar surface area) was calculated using ChemDraw Professional (PerkinElmer, Boston, MA, v. 16.0). cLogP was calculated as reported.57 The synthesis of 1b was recently described.7

General Procedures: Deprotection Reactions. Method A.

A mixture of compound (1 equiv) and potassium hydroxide (5 equiv) in methanol/water (2:1) was stirred at 50 °C. This mixture was neutralized with 1 N HCl until pH was 5–6. The slightly acidic mixture was evaporated under reduced pressure and purified by silica gel column chromatography (dichloromethane/methanol/acetic acid = 95:5:0.1) or semipreparative HPLC (10 mM triethylammonium acetate buffer/acetonitrile = 80:20 to 20:80 in 40 min) to afford the compound as a white solid.

Method B.

A solution of compound in trifluoroacetic acid/tetrahydrofuran (2:1) was stirred at room temperature. The solvent was evaporated with toluene under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (dichloromethane/methanol = 95:5) or semipreparative HPLC (10 mM triethylammonium acetate buffer/acetonitrile = 80:20 to 20:80 in 40 min) to afford the compound as a white solid.

General Procedures: Suzuki Reaction. Method C.

The mixture of compound 38 (1 equiv), Pd(PPh3)4 (0.06 equiv), and potassium carbonate (3 equiv) in N,N-dimethylformamide was purged with nitrogen gas for 15 min, and then various aryl halides (1.2 equiv) were added to the mixture. The mixture was stirred at 85 °C for 5 h and then allowed to be cooled to room temperature. This mixture was partitioned between ethyl acetate (5 mL) and water (10 mL). The aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (5 mL × 2), and then the combined organic layer was washed with brine (3 mL), dried (MgSO4 or Na2SO4), filtered, and evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography to afford the compound as a white solid.

Method D.

The mixture of compound 38 (1 equiv) and aryl halide (1.2 equiv) in dimethoxyethane/2 M Na2CO3 aqueous solution (10:1) was purged with nitrogen gas for 30 min, and then PdCl2(dppf) (0.1 equiv) was added to the mixture. The mixture was stirred at 60 °C for 4 h. After cooling at room temperature, this mixture was partitioned between ethyl acetate (5 mL) and water (10 mL). The aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (5 mL × 2), and then the combined organic layer was washed with brine (3 mL), dried (MgSO4 or Na2SO4), filtered, and evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography to afford the compound as a white solid.

Method E.

A mixture of compound 38 (1 equiv) and aryl bromide (1.2 equiv) in DMF/H2O (10:1; 20 mM) was purged with nitrogen gas for 30 min, and then Pd(PPh3)4 (0.05 equiv) and Na2CO3 (3 equiv) were added to the mixture, which was stirred for 1 h at 40–120 °C. The aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate twice, and then the combined organic layer was washed with brine, dried (MgSO4 or Na2SO4), filtered, and evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography to afford the compound as white solids.

Method F.

The mixture of compound 38 (1 equiv), Pd(PPh3)4 (0.06 equiv), potassium carbonate (3 equiv), and various aryl halides (1.2 equiv) in N,N-dimethylformamide was purged with nitrogen gas for 15 min. The mixture was stirred at 100 °C for 30–90 min in microwave. After microwave irradiation, the mixture was allowed to be cooled at room temperature. This mixture was partitioned between ethyl acetate (5 mL) and water (10 mL). The aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (5 mL × 2), and then the combined organic layer was washed with brine (3 mL), dried (Na2SO4), filtered, and evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography to afford the compound as a white solid.

4-(4-(1-Formylpiperidin-4-yl)phenyl)-7-(4-(trifluoromethyl)-phenyl)-2-naphthoic Acid (1c).

To a solution of acetic formic anhydride (1 mL from Ac2O and formic acid = 2:1, v/v) was slowly added compound 1a (10 mg, 0.019 mmol) at 0 °C. After complete addition, cooling was continued for 3 h, and the mixture was then stirred at rt for 12 h. The reaction mixture was evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (dichloromethane/methanol = 50:1) to afford the compound 1c (7.0 mg, 71%) as a white solid. HPLC purity: 98% (Rt = 14.62 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.73 (s, 1H), 8.64 (s, 1H), 8.08–7.96 (m, 5H), 7.90–7.88 (m, 3H), 7.50–7.44 (m, 4H), 4.37–4.34 (m, 1H), 3.85–3.81 (m, 1H), 3.22–3.16 (m, 1H), 2.97–2.90 (m, 1H), 2.77–2.70 (m, 1H), 1.96–1.89 (m, 2H), 1.68–1.47 (m, 2H). MS (ESI, m/z): 504.2 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): calcd [M + 1]+ for C30H25NO3F3, 503.1787; found, 504.1792.

4-(4-(1-(2,2,2-Trifluoroacetyl)piperidin-4-yl)phenyl)-7-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-2-naphthoic Acid (1d).

To trifluoroacetic anhydride (100 μL) was slowly added compound 1a (10 mg, 0.019 mmol) at 0 °C. After complete addition, cooling was continued for 1 h, and the mixture was then stirred at rt for 2 h. The reaction mixture was evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (dichloromethane/methanol = 50:1) to afford compound 1d (10.0 mg, 92%) as a white solid. HPLC purity: 99% (Rt = 16.92 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.80 (s, 1H), 8.27 (s, 1H), 8.12–8.07 (m, 2H), 7.86–7.77 (m, 5H), 7.53 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 7.39 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 4.81–4.78 (m, 1H), 4.25–4.22 (m, 1H), 3.37–3.30 (m, 1H), 3.01–2.92 (m, 2H), 2.15–2.11 (m, 2H), 1.91–1.81 (m, 2H). MS (ESI, m/z): 570.1 [M – 1]−. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M – 1]− calcd for C31H22NO3F6, 570.1504; found, 570.1493.

(4′-(Piperidin-4-yl)-5-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-yl)methyl Dihydrogen Phosphate (3b).

Method B. Yield: 69%. HPLC purity: 96% (Rt = 8.58 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 9.20–9.19 (m, 1H), 8.05–8.03 (m, 2H), 7.96 (s, 1H), 7.85 (s, 1H), 7.79 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 7.74 (s, 1H), 7.67 (d, J = 8.40 Hz, 2H), 7.34 (d, J = 7.60 Hz, 2H), 4.82–4.80 (m, 2H), 2.96–2.92 (m, 2H), 2.66–2.58 (m, 3H), 1.71–1.67 (m, 2H), 1.56–1.49 (m, 2H). MS (ESI, m/z): 559.2 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C27H27N4O4F3P, 559.1722; found, 559.1716.

4′-Amino-5-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic Acid (7).

Method A. Yield: 62%. HPLC purity: 97% (Rt = 8.96 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 9.25 (s, 1H), 8.48 (s, 1H), 8.37 (s, 2H), 8.16 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 7.79 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 7.73 (d, J = 8.40 Hz, 2H), 7.62 (d, J = 8.40 Hz, 2H). MS (ESI, m/z): 425.1 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C22H16N4O2F3, 425.1225; found, 425.1221.

4′-Acetamido-5-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic Acid (8).

Method A. Yield: 76%. HPLC purity: 99% (Rt = 7.95 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 9.21 (s, 1H), 8.46 (s, 1H), 8.34 (d, J = 7.20 Hz, 2H), 8.13 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 7.76 (d, J = 8.40 Hz, 2H), 7.72 (s, 4H), 2.15 (s, 3H). MS (ESI, m/z): 467.1 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C24H18N4O3F3, 467.1331; found, 467.1330.

4′-Benzamido-5-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic Acid (9).

Method A. Yield: 73%. HPLC purity: 99% (Rt = 9.48 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 9.70 (s, 1H), 8.41 (s, 1H), 8.29 (broad s, 2H), 8.21 (d, J = 7.60 Hz, 2H), 8.00–7.97 (m, 4H), 7.90–7.83 (m, 4H), 7.62–7.54 (m, 3H). MS (ESI, m/z): 529.1 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C29H20N4O3F3, 529.1488; found, 529.1489.

4′-((tert-Butoxycarbonyl)amino)-5-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)-phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic Acid (10).

Method A. Yield: 50%. HPLC purity: 99% (Rt = 10.36 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 9.25 (s, 1H), 8.48 (s, 1H), 8.37–8.35 (m, 2H), 8.16 (d, J = 8.40 Hz, 2H), 7.78 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 7.71 (d, J = 8.40 Hz, 2H), 7.58 (d, J = 8.40 Hz, 2H), 1.54 (s, 9H). MS (ESI, m/z): 525.2 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C27H24N4O4F3, 525.1750; found, 525.1755.

4′-(Piperidine-4-carboxamido)-5-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic Acid (11).

Method B. Yield: 87%. HPLC purity: 99% (Rt = 21.20 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.03–8.01 (m, 4H), 7.83 (s, 1H), 7.68 (d, J = 8.40 Hz, 2H), 7.30–7.25 (m, 5H), 2.70–2.68 (m, 2H), 2.23–2.20 (m, 2H), 2.00–1.93 (m, 1H), 1.44–1.27 (m, 4H). MS (ESI, m/z): 536.2 [M + Na]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C28H25N5O3F3, 536.1909; found, 536.1913.

4′-(1-(tert-Butoxycarbonyl)piperidine-4-carboxamido)-5-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic Acid (12).

Method A. Yield: 82%. HPLC purity: 98% (Rt = 24.10 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 9.73 (s, 1H), 8.43 (s, 1H), 8.38 (s, 1H), 8.27 (s, 1H), 8.20 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 7.90 (d, J = 8.40 Hz, 2H), 7.91–7.77 (m, 4H), 4.05–3.97 (m, 2H), 2.92–2.75 (m, 3H), 1.85–1.76 (m, 2H), 1.56–1.45 (m, 2H), 1.41 (s, 9H). MS (ESI, m/z): 658.2 [M + Na]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + Na]+ calcd for C33H32N5O5F3Na, 658.2253; found, 658.2256.

5-(4-(4-(Trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-[1,1′-bi-phenyl]-3,4′-dicarboxylic Acid (13).

Method A. Yield: 68%. HPLC purity: 99% (Rt = 13.46 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 9.77 (s, 1H), 8.56–8.53 (m, 2H), 8.36 (broad s, 1H), 8.20 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 8.11 (d, J = 8.40 Hz, 2H), 8.00 (d, J = 8.40 Hz, 2H), 7.91 (d, J = 8.40 Hz, 2H). MS (ESI, m/z): 454.1 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C23H15N3O4F3, 454.1015; found, 454.1017.

4′-((3-Aminopropyl)carbamoyl)-5-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)-phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic Acid (14).

Method B. Yield: 63%. HPLC purity: 97% (Rt = 12.68 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 9.73 (s, 1H), 8.55 (s, 1H), 8.51 (s, 1H), 8.37 (s, 1H), 8.23–8.20 (m, 4H), 8.00 (d, J = 8.40 Hz, 2H), 7.90 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 3.51–3.46 (m, 2H), 3.00–2.99 (m, 2H), 1.93–1.90 (m, 2H). MS (ESI, m/z): 510.2 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C26H23N5O3F3, 510.1753; found, 510.1754.

4′-Bromo-5-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic Acid (15).

Method A. Yield: 77%. HPLC purity: 99% (Rt = 12.93 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 9.17 (s, 1H), 8.43 (s, 1H), 8.35 (s, 1H), 8.25 (s, 1H), 8.16 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 7.79 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 7.72 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 7.66 (d, J = 8.40 Hz, 2H). MS (ESI, m/z): 488.0, 490.0 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C22H14N3O2F3Br, 488.0221; found, 488.0218.

4′-(2-Amino-2-oxoethyl)-5-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic Acid (16).

Method A. Yield: 64%. HPLC purity: 99% (Rt = 8.55 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 9.24 (s, 1H), 8.50 (s, 1H), 8.38 (s, 2H), 8.16 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 7.79–7.74 (m, 4H), 7.48 (d, J = 7.60 Hz, 2H), 3.60 (s, 2H). MS (ESI, m/z): 467.1 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C24H18N4O3F3, 467.1331; found, 467.1332.

4′-(2-Cyanoethyl)-5-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic Acid (17).

The mixture of compound 38 (30 mg, 0.063 mmol), Pd(PPh3)4 (4 mg, 0.003 mmol), and 2 M K2CO3 aqueous solution (90 μL, 0.180 mmol) in N,N-dimethylformamide/water (1:1, 3 mL) was purged with nitrogen gas for 15 min, and then 3-(4-bromophenyl)propionitrile (16 mg, 0.076 mmol) was added to the mixture. The mixture was stirred at 90 °C for 12 h and then allowed to be cooled at room temperature. This mixture was partitioned between ethyl acetate (5 mL) and water (10 mL). The aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (5 mL × 2), and then the combined organic layer was washed with brine (3 mL), dried (MgSO4), filtered, and evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (chloroform/methanol = 10:1) to afford the compound 17 (18 mg, 61%) as a white solid. HPLC purity: 99% (Rt = 7.63 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 9.27 (s, 1H), 8.53 (s, 1H), 8.40 (m, 2H), 8.17 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 7.80–7.77 (m, 4H), 7.48 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 3.03 (t, J = 7.20 Hz, 2H), 2.81 (t, J = 7.20 Hz, 2H). MS (ESI, m/z): 463.1 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C25H18N4O2F3, 463.1382; found, 463.1381.

4′-(3-Aminopropyl)-5-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic Acid (18).

Method B. Yield: 98%. HPLC purity: 98% (Rt = 8.14 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 9.27 (s, 1H), 8.52 (s, 1H), 8.42 (s, 1H), 8.38 (s, 1H), 8.17 (d, J = 7.60 Hz, 2H), 7.80–7.75 (m, 4H), 7.43 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 2.99 (t, J = 7.60 Hz, 2H), 2.82 (t, J = 7.60 Hz, 2H), 2.05–2.02 (m, 2H). MS (ESI, m/z): 467.2 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C25H22N4O2F3, 467.1695; found, 467.1689.

4′-(3-Aminoprop-1-yn-1-yl)-5-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic Acid (19).

Method B. Yield: 62%. HPLC purity: 97% (Rt = 10.49 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 9.67 (s, 1H), 8.42 (s, 1H), 8.26 (s, 1H), 8.21 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 8.16 (s, 1H), 7.88 (d, J = 8.40 Hz, 2H), 7.79 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 7.53 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 3.53 (s, 2H). MS (ESI, m/z): 463.1 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C25H18N4O2F3, 463.1382; found, 463.1380.

4′-(3-((tert-Butoxycarbonyl)amino)propyl)-5-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic Acid (20).

Method A. Yield: 66%. HPLC purity: 99% (Rt = 10.56 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 9.24 (s, 1H), 8.49 (s, 1H), 8.38–8.36 (m, 2H), 8.16 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 7.78 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 7.70 (d, J = 8.40 Hz, 2H), 7.37 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 3.10 (t, J = 7.20 Hz, 2H), 2.71 (t, J = 7.20 Hz, 2H), 1.87–1.78 (m, 2H), 1.45 (s, 9H). MS (ESI, m/z): 589.2 [M + Na]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C30H29N4O4F3Na, 589.2039; found, 589.2043.

4′-(4-Hydroxybutyl)-5-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic Acid (21).

Method A. Yield: 39%. HPLC purity: 99% (Rt = 7.40 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 9.25 (s, 1H), 8.50 (s, 1H), 8.38 (s, 2H), 8.16 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 7.79 (d, J = 8.40 Hz, 2H), 7.70 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 7.37 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 3.59 (t, J = 6.40 Hz, 2H), 2.72 (t, J = 7.60 Hz, 2H), 1.78–1.71 (m, 2H), 1.64–1.57 (m, 2H). MS (ESI, m/z): 482.2 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C26H23N3O3F3, 482.1692; found, 482.1694.

4′-(1-Aminocyclopropyl)-5-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic Acid (22).

Method A. Yield: 69%. HPLC purity: 98% (Rt = 6.80 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 9.27 (s, 1H), 8.55–8.39 (m, 3H), 8.15 (broad s, 2H), 7.88 (broad s, 2H), 7.78 (broad s, 2H), 7.63 (broad s, 2H), 1.43–1.38 (m, 4H). MS (ESI, m/z): 465.2 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C25H20N4O2F3, 465.1538; found, 465.1539.

4′-(1-(Aminomethyl)cyclopropyl)-5-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)-phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic Acid (23).

Method B. Yield: 52%. HPLC purity: 97% (Rt = 10.85 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 9.08 (s, 1H), 8.38 (s, 1H), 8.30 (s, 1H), 8.16 (s, 1H), 8.09 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 7.77–7.73 (m, 4H), 7.55 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 3.22 (s, 2H), 1.09–1.06 (m, 4H). MS (ESI, m/z): 479.2 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C26H22N4O2F3, 479.1695; found, 479.1693.

4′-(1-(((tert-Butoxycarbonyl)amino)methyl)cyclopropyl)-5-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic Acid (24).

Method A. Yield: 51%. HPLC purity: 99% (Rt = 21.57 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 9.26 (s, 1H), 8.51 (s, 1H), 8.40–8.38 (m, 2H), 8.17 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 7.80 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 7.73 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 7.51 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 3.34 (s, 2H), 1.39–1.28 (m, 9H), 0.94–0.86 (m, 4H). MS (ESI, m/z): 601.2 [M + Na]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + Na]+ calcd for C31H29N4O4F3Na, 601.2039; found, 601.2040.

4′-(1-Aminocyclobutyl)-5-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic Acid (25).

Method B. Yield: 65%. HPLC purity: 99% (Rt = 8.69 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 9.27 (s, 1H), 8.55 (s, 1H), 8.45 (s, 1H), 8.41 (s, 1H), 8.16 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 7.93 (d, J = 8.40 Hz, 2H), 7.79 (d, J = 8.40 Hz, 2H), 7.69 (d, J = 8.40 Hz, 2H), 2.89–2.82 (m, 2H), 2.70–2.63 (m, 2H), 2.33–2.24 (m, 1H), 2.07–1.97 (m, 1H). MS (eSI, m/z): 479.3 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C26H22N4O2F3, 479.1695; found, 479.1696.

4′-(1-((tert-Butoxycarbonyl)amino)cyclobutyl)-5-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic Acid (26).

Method A. Yield: 47%. HPLC purity: 99% (Rt = 10.76 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 9.18 (s, 1H), 8.40–8.39 (m, 2H), 8.26 (s, 1H), 8.17 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 7.80–7.76 (m, 4H), 7.59 (d, J = 8.40 Hz, 2H), 2.60–2.46 (m, 4H), 2.16–2.07 (m, 1H), 1.99–1.88 (m, 1H), 1.40–1.25 (m, 9H). MS (ESI, m/z): 579.2 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C31H30N4O4F3, 579.2219; found, 579.2219.

4′-(3-(Hydroxymethyl)oxetan-3-yl)-5-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)-phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic Acid (27).

Method A. Yield: 47%. HPLC purity: 99% (Rt = 8.71 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 9.25 (s, 1H), 8.51 (s, 1H), 8.41 (s, 1H), 8.39 (s, 1H), 8.15 (d, J = 8.40 Hz, 2H), 7.80–7.77 (m, 4H), 7.32 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 4.97 (d, J = 5.60 Hz, 2H), 4.89 (d, J = 6.00 Hz, 2H), 3.94 (s, 2H). MS (ESI, m/z): 496.2 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C26H21N3O4F3, 496.1484; found, 496.1488.

4′-(Isoxazol-3-yl)-5-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic Acid (28).

Method A. Yield: 74%. HPLC purity: 98% (Rt = 11.86 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 9.28 (s, 1H), 8.75 (s, 1H), 8.57 (s, 1H), 8.46 (s, 2H), 8.17 (d, J = 7.60 Hz, 2H), 8.05 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 7.94 (d, J = 8.40 Hz, 2H), 7.79 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 7.00 (s, 1H). MS (ESI, m/z): 477.1 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C25H16N4O3F3, 477.1175; found, 477.1177.

4′-(5-(Hydroxymethyl)isoxazol-3-yl)-5-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)-phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic Acid (29).

Method A. Yield: 43%. HPLC purity: 98% (Rt = 20.10 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 9.77 (s, 1H), 8.57 (s, 1H), 8.54 (s, 1H), 8.36 (s, 1H), 8.20 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 8.08–8.01 (m, 4H), 7.91 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 7.05 (s, 1H), 5.75 (t, J = 6.00 Hz, 1H), 4.64 (d, J = 6.00 Hz, 2H). MS (ESI, m/z): 507.1 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C26H18N4O4F3, 507.1280; found, 507.1271.

4′-(5-(2-Hydroxyethyl)isoxazol-3-yl)-5-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)-phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic Acid (30).

Method A. Yield: 55%. HPLC purity: 95% (Rt = 10.69 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 9.74 (s, 1H), 8.51 (s, 1H), 8.46 (s, 1H), 8.35 (s, 1H), 8.20 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 8.03–7.98 (m, 4H), 7.90 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 6.93 (s, 1H), 3.77 (t, J = 6.40 Hz, 2H), 2.97 (d, J = 6.40 Hz, 2H). MS (ESI, m/z): 521.1 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C27H20N4O4F3, 521.1437; found, 521.1435.

4′-(1H-Tetrazol-5-yl)-5-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic Acid (31).

Method A. Yield: 43%. HPLC purity: 98% (Rt = 15.95 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 9.24 (s, 1H), 8.49 (s, 1H), 8.45 (s, 1H), 8.35 (s, 1H), 8.22–8.17 (m, 4H), 7.92 (d, J = 8.40 Hz, 2H), 7.80 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H). MS (ESI, m/z): 478.1 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C23H15N7O2F3, 478.1239; found, 478.1242.

4-(4-(5-(Hydroxymethyl)isoxazol-3-yl)phenyl)-7-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-2-naphthoic Acid (32).

Method A. Yield: 93%. HPLC purity: 98% (Rt = 12.07 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.79 (s, 1H), 8.68 (s, 1H), 8.09–8.05 (m, 5H), 8.01–7.98 (m, 1H), 7.95 (m, 1H), 7.91–7.89 (m, 2H), 7.70 (d, J = 8.40 Hz, 2H), 7.04 (s, 1H), 5.80–5.73 (m, 1H), 4.66–4.63 (m, 2H). MS (ESI, m/z): 490.1 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C28H19NO4F3, 490.1266; found, 490.1269.

4′-(5-(Hydroxymethyl)isoxazol-3-yl)-5-(4-(trifluoromethyl)-benzamido)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic Acid (33).

Method A. Yield: 62%. HPLC purity: 99% (Rt = 10.29 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 8.35 (broad s, 2H), 8.17–8.13 (m, 3H), 7.97 (d, J = 8.40 Hz, 2H), 7.86–7.81 (m, 4H), 6.82 (s, 1H), 4.74 (s, 2H). MS (ESI, m/z): 483.1 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C25H18N2O5F3, 483.1168; found, 483.1170.

4-(4-(Piperidin-4-yl)phenyl)-6-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)picolinic Acid (34).

Method B. Yield: 60%. HPLC purity: 99% (Rt = 7.87 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 9.55 (s, 1H), 8.31–8.26 (m, 4H), 7.91–7.85 (m, 4H), 7.47 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 3.68–3.65 (m, 1H), 3.02–2.88 (m, 4H), 1.95–1.83 (m, 4H). MS (ESI, m/z): 494.2 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C26H23N5O2F3, 494.1804; found, 494.1805.

2-(4-(Piperidin-4-yl)phenyl)-6-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)isonicotinic Acid (35).

Method B. Yield: 65%. HPLC purity: 95% (Rt = 10.72 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 9.79 (s, 1H), 8.42 (s, 2H), 8.34–8.33 (m, 4H), 7.89 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 7.44 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 3.62–3.59 (m, 1H), 3.07–2.92 (m, 4h), 2.03–1.89 (m, 4H). MS (ESI, m/z): 494.2 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C26H23N5O2F3, 494.1804; found, 494.1805.

6-(4-(Piperidin-4-yl)phenyl)-4-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)picolinic Acid (36).

Method B. Yield: 65%. HPLC purity: 99% (Rt = 11.24 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 9.94 (s, 1H), 8.71 (s, 1H), 8.56 (s, 1H), 8.28 (d, J = 7.20 Hz, 2H), 8.19 (d, J = 7.60 Hz, 2H), 7.93 (d, J = 7.20 Hz, 2H), 7.46 (d, J = 7.20 Hz, 2H), 3.43–3.40 (m, 2H), 3.07–2.92 (m, 3h), 2.03–2.00 (m, 2H), 1.91–1.84 (m, 2H). MS (ESI, m/z): 494.2 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C26H23N5O2F3, 494.1804; found, 494.1808.

2-(Dimethylamino)-2-oxoethyl 4′-(Piperidin-4-yl)-5-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxylate (37a).

Method B. Yield: 78%. HPLC purity: 97% (Rt = 20.45 min). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 9.29 (s, 1H), 8.59 (s, 1H), 8.47 (s, 1H), 8.45 (s, 1H), 8.17 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 7.82–7.79 (m, 4H), 7.47 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H), 5.18 (s, 2H), 3.56–3.53 (m, 2H), 3.23–3.16 (s, 2H), 3.13 (s, 3H), 3.05–2.99 (m, 1H), 3.02 (s, 3H), 2.18–2.14 (m, 2H), 2.03–1.92 (m, 2H). MS (ESI, m/z): 578.3 [M + 1]+. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + 1]+ calcd for C31H31N5O3F3, 578.2379; found, 578.2390.