Abstract

Introduction: Aberrations in cell cycle control is defined as one of the hallmarks of cancer, while cyclin D1 is an essential protein to cell cycle which promote G1 phase into S phase, and frequently overexpressed in many human cancers. However, new functions have been identified in transgenic mice models, including the transcription of genome, the development of chromosome instability and DNA repair. In this research, our aim is to find the function of cyclin D1 in transcription in human cancers.

Methods: The correlation of the cyclin D1 expression levels and prognosis of cervical cancer patients were analyzed in tissue microarray (TMA) cohort. We chose C33A as our main research object. Using chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) coupled with RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), to find out the genes differentially expressed in C33A, cyclin D1 knock-in C33A and cyclin D1 knock-down C33A.

Results: We found that upregulation of cyclin D1 was associated with shorter overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS). Functionally, we identified 422 genes differentially expressed through analysis of the results of ChIP-seq and RNA-seq. These genes are highly enriched in Gene Ontology categories and involve in diverse cellular functions via KEGG classification, including replication and repair, signal transduction, cell growth and death.

Conclusion: These findings suggested that the expression of cyclin D1 was associated with the prognosis of patients with cervical cancer. Cyclin D1 can serve both to activate and downregulate gene expression as a transcriptional role directly binding with genome DNA, which means that cyclin D1 may be a key protein during oncogenesis and tumor development.

Keywords: Cyclin D1, Prognosis, Transcriptional role, ChIP-seq, RNA-seq

Introduction

Cancer has caused more deaths than all coronary heart disease or stroke since from 2011, which is still a major public health problem 1. The cancer burden is increasing these years particularly in low and middle income countries, although many new cancer treatments or strategies are developed and used nowadays. The results show that in 2017 there were 24.5 million incident cases and 9.6 million deaths due to cancer; the incident cases increased by 33% between 2007 and 2017 2. Based on these data, it is necessary to find the factors of leading the tumorigenesis and cancer development. It has been found that aberrations in cell cycle control is defined as one of the hallmarks of cancer 3. Cyclin D1 is a key protein to regulate the cell cycle which promote G1 phase into S phase by binding with CDK4 or CDK6, then phosphorylates and inactivates pRb proteins to regulate nuclear DNA synthesis and mitochondrial biogenesis 4, 5, and frequently overexpressed in many human cancer, such as breast cancer 6, pancreatic cancer 7, colorectal carcinoma 8, lung cancer 9, 10. Scientists designed the CDK4/6 inhibitors to treat cancer based on this target 11-14, but it doesn't work in some tumor patients or cancer cells unexpectedly 15-18. What's more, it was reported that the new functions of cyclin D1 have been identified in transgenic mice models, including the transcription of genome, the development of chromosome instability and DNA repair 19-21. We think cyclin D1 may regulate downstream genes independent of cell cycle, which could be a cause of drug resistance as a transcriptional role.

In order to find the clinic correlation of cyclin D1 and reveal the mechanism of the genome-wide cyclin D1 binding sites and the changes of downstream genes in cancer, we firstly analyzed the correlation between cyclin D1 expression and prognosis in the tissue microarray (TMA) cohort. And then performed the ChIP-seq (Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by high-throughput sequencing), which is a method to analysis the comprehensive identification of the binding sites of DNA-associating proteins across the genome at high resolution22, then established the overexpression and down-regulation cell models, obtained the transcriptomics by RNA-seq. Through analysis of the results of ChIP-seq and RNA-seq, we can study the new function of cyclin D1 protein.

Materials and Methods

Tissue microarray

The tissue microarray, purchased from Shanghai Outdo Biotech, contained 126 cervical cancer specimens and 42 paired non-tumor specimens (Outdo cervical cancer cohort, HUteS168Su01). The study protocols were approved by the hospital's research ethics committee and were conducted in accordance with the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Cell line and cell culture

The human cervical cancer cell line C33A was maintained in our laboratory. The cell line was cultured in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum and incubated in 5% CO2 at 37 °C (for more details, please refer to the materials and methods in our other article 17).

Cell transfection

The plasmids contained the ShRNA duplexes were designed against CCND1 with the following sequences: 5′- ATTGGAATAGCTTCTGGAAT-3′, and the negative control sequences: 5′-AATTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3′. The plasmids containing these sequences were named pLKO.1-Puro-shRNA-CCND1 and pLKO.1-Puro-shRNA.The stable transfection cell lines were named C33A-shNC and C33A-sh, respectively. The plasmids contained the whole CCND1 coding region were named pHAGE-Puro-HA-Flag-CCND1, the negative control plasmids were named pHAGE-Puro-HA-Flag. Therefore, the stable transfection cell lines were named C33A-OENC and C33A-OE. All these plasmids were bought from Bioeagle (Wuhan, China).

Immunofluorescence assay

The immunofluorescence of cyclin D1 and Flag were used to determine the expression of C33A-shNC and C33A-sh, C33A-OENC and C33A-OE. Cells were grown in 12-well plates and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. The cells were incubated with the cyclin D1 primary antibody (1:100 dilution,#A10757, ABclonal, USA) and HA-Tag antibody (1:100 dilution,#AE008, ABclonal, USA) and then incubated with FITC-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit antibody (1:100 dilution, #SA00003-8, Proteintech, China) or CoraLite594-conjugated donkey anti-mouse antibody (1:200 dilution, #SA00013-7, Proteintech, China) for 2h. The cells were imaged on a fluorescence microscope. (For more details, please refer to the materials and methods in our other article 17).

RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cells using Tirol reagent (Vazyme, China) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Then the cDNA was synthesized from about 1 μg of total RNA by the HiScript® Q RT SuperMix for qPCR (+gDNA wiper) (#R123, Vazyme, China) at 25 °C for 10 min, followed by 50 °C for 30 min, and finally 85 °C for 5 min. Real-time PCR was performed with ChamQTMSYBR®qPCR Master Mix(#Q321-02, Vazyme, China) in a 20 μL reaction volume (10 μL SYBR Master Mix, 10 μM forward and reverse primers, 7.2 μL H2O and 1 μL cDNA template) on a CFX Connect™ instrument (Bio-Rad, CA). The human GAPDH gene was performed as an internal control. The following protocol was used for GAPDH and CCND1: preincubated at 95 °C for 30 sec followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 sec, 58 °C for 15 sec and 72 °C for 30 sec. (For more details, please refer to the materials and methods in our other article 17).

Western blotting

Protein lysates were extracted from cells treated with PMSF and phosphatase inhibitor tablets. The concentrations of the protein lysates were quantified by BCA assay. These samples were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes which followed with incubated with primary antibodies Cyclin D1 and GAPDH at 4 °C overnight. The membranes were visualized by ECL after the incubation with the secondary antibody. The bands were detected using the ChemiDoc XRS+ system.

ChIP-seq

ChIP material was performed in accordance with the Magna ChIP (Millipore) manufacturer's guidelines. Briefly, the C33A cells were harvested in 1.5 mL ice-cold PBS and fixed for 15 minutes with 37% paraformaldehyde (final concentration, 1%). 2 mol/L glycine (final concentration, 0.125 mol/L) was added into the unreacted formaldehyde for 10 min. Then washing the cells with ice-cold PBS twice, and the pellets were harvested into PBS (1 ml) with protease inhibitor cocktail and pooled together in a 1.5 mL tube for obtaining the cells. The DNA fragmentation of the pellets was achieved by sonication. IP was performed with 5 uL cyclin D1 antibody (1:5000 dilution, #60186-1-lg, Proteintech, China) and the Input as negative control. Washes and elution of the IP DNA were also prepared according to the Magna ChIP protocol (Millipore). Sample libraries were made by using Rubicon ThruPLEX® DNA-seq Kit and sequenced by using the HiSeq platform (Illumina).

RNA-seq

RNA extraction, rRNA depletion, library construction, and sequencing were done by mega genomics company. The sequenced Reads were from the HiSeq platform (Illumina) which were saved as FASTQ reads.

Statistical analyses of ChIP-seq

The raw data was filtered to give high-quality data (clean data) by Trimmomatic (version 0.30). Then, the clean data was mapped with human reference genome-hg 19 by BWA software package. The enrichment interval was obtained by using MACS (version 1.4.2), and the Motif of the enrichment interval was predicted by MEME 23.

Statistical analyses of RNA-seq

The data was mapped by using HISAT2 24. The raw data was analyzed in R (version 3.5.1). Differential analysis was performed with DESeq 2 25.

Pathway enrichment analysis

The pathway enrichment analysis for GO and KEGG was performed using the safe package 26.

Statistical analysis

Differences in clinicopathologic factors between the cyclin D1 high- or low-expression groups were analyzed via the Chi-square test. The Kaplan-Meier and log-rank test methods were used to determine the survival rate. Student's t- test was applied into the analysis of data statistically. It was considered statistically significant that the P value of <0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics v20.0 software.

Results

Upregulated cyclin D1 expression is associated with poor prognosis in cervical cancer TMA cohort

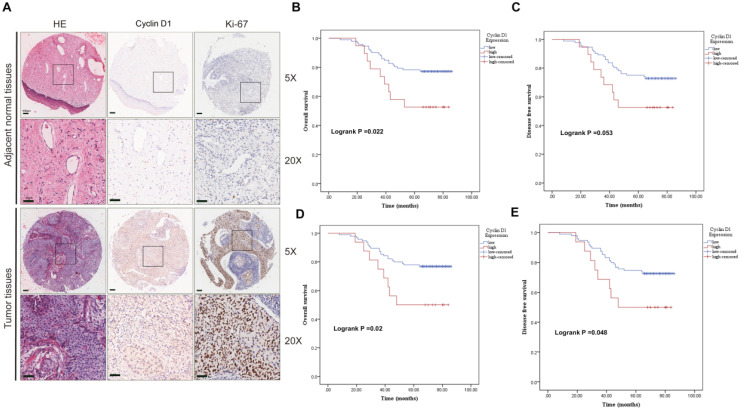

We first evaluated the clinic correlation of cyclin D1 through the cervical cancer TMA cohort. To study the transcription of cyclin D1, we analyzed the expression of cyclin D1 in the cytoplasm and nucleus separately. IHC staining showed cyclin D1 and Ki-67 protein expression in the cervical cancer tissues compared with that in normal tissues (Fig. 1A). Statistical analysis showed that there was no significant difference of cyclin D1 expression between cancer and adjacent tissues (Table 1A cytoplasm, p=0.051. Table 1B nucleus, p=0.125). We found that cervical cancer patients with high cyclin D1 expression had significant lower probabilities of OS (Fig. 1B, p=0.022) and tend to lower DFS (Fig. 1C, p=0.053) in comparison with patients with low cyclin D1 expression in the cytoplasm. Moreover, Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed shorter OS (Fig. 1D, p=0.02) and DFS times (Fig. 1E, p=0.048) in patients with high cyclin D1 expression in the nucleus.

Figure 1.

Upregulated cyclin D1 expression is associated with poor prognosis in cervical cancer TMA cohort. (A) Representative cyclin D1 and Ki-67 IHC staining patterns in cervical cancer tissue and adjacent normal tissues. Scale bar, 100 µm and 50 µm. (B and C) The probability of OS and RFS were analyzed by Kaplan-Meier analysis, according to cyclin D1 staining scores in cytoplasm of the TMA cohort. (D and E) The probability of OS and RFS were analyzed by Kaplan-Meier analysis, according to cyclin D1 staining scores in the nucleus of the TMA cohort.

Table 1A.

Differential expression of Cyclin D1 in cancer and adjacent tissues

| n | Cyclin D1 expression | Chi-square value | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low | ||||

| Cancer | 111 | 18 | 93 | 0.355 | 0.551 |

| Adjacent tissues | 26 | 3 | 23 | ||

Table 1B.

Differential expression of Cyclin D1 in cancer and adjacent tissues

| n | Cyclin D1 expression | Chi-square value | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low | ||||

| Cancer | 111 | 16 | 95 | 2.359 | 0.125 |

| Adjacent tissues | 26 | 7 | 19 | ||

We also analyzed the correlation between cyclin D1 expression and clinicopathologic characteristics. It was showed that the cyclin D1 expression in the cytoplasm was related to age (p=0.014) and grade (p=0.002) (Table 2A), the cyclin D1 expression in the nucleus was also related to age (p=0.04) and grade (p=0.049) (Table 2B). Next, we performed univariate and multivariate analysis of the factors correlated with overall survival of uterine cervix cancer patients with Cox's regression model in the tissue microarray cohort. Age (p=0.013 HR=2.388), FIGO stage (p<0.001, HR=16.975) and high cyclin D1 expression in the cytoplasm (p=0.005, HR=3.494) were significantly associated with poor survival (Table 3A). On the other hand, age (p=0.013 HR=4.599) and FIGO stage (p<0.001, HR=12.332) were also significantly associated with poor survival in the nucleus group (Table 3B). The results suggest that cyclin D1 in the cytoplasm is an independent prognostic factor and that high cyclin D1 expression is associated with poorer survival in cervical cancer.

Table 2A.

Correlation between Cyclin D1 expression and clinicopathologic characteristics

| Variables | Cyclin D1 expression | Total | χ2 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| low | high | ||||

| Age (year) | 6.091 | 0.014 | |||

| ≤42 | 37 | 2 | 39 | ||

| >42 | 55 | 17 | 72 | ||

| Grade | 9.367 | 0.002 | |||

| I/II | 9 | 7 | 16 | ||

| III | 67 | 9 | 76 | ||

| T stage | 0.496 | 0.481 | |||

| T1 | 50 | 12 | 62 | ||

| T2/T3/T4 | 42 | 7 | 49 | ||

| N stage | 0.068 | 0.794 | |||

| N0 | 75 | 15 | 90 | ||

| N1 | 17 | 4 | 21 | ||

| FIGO stage | 0.496 | 0.481 | |||

| I | 50 | 12 | 62 | ||

| II/III/IV | 42 | 7 | 49 | ||

Table 2B.

Correlation between Cyclin D1 expression and clinicopathologic characteristics

| Variables | Cyclin D1 expression | Total | χ2 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| low | high | ||||

| Age (year) | 4.203 | 0.04 | |||

| ≤42 | 37 | 2 | 39 | ||

| >42 | 58 | 14 | 72 | ||

| Grade | 3.859 | 0.049 | |||

| I/II | 11 | 5 | 16 | ||

| III | 67 | 9 | 76 | ||

| T stage | 0.260 | 0.61 | |||

| T1 | 54 | 8 | 62 | ||

| T2/T3/T4 | 41 | 8 | 49 | ||

| N stage | 1.853 | 0.173 | |||

| N0 | 79 | 11 | 90 | ||

| N1 | 16 | 5 | 21 | ||

| FIGO stage | 0.260 | 0.61 | |||

| I | 54 | 8 | 62 | ||

| II/III/IV | 41 | 8 | 49 | ||

Table 3A.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of the factors correlated with overall survival of uterine cervix cancer patients

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p value | HR | 95%CI | p value | HR | 95%CI | |

| Expression | 0.027 | 2.415 | 1.105-5.279 | 0.005 | 3.494 | 1.453-8.4 |

| Age | 0.002 | 6.453 | 1.967-21.164 | 0.013 | 4.577 | 1.374-15.25 |

| Grade stage | 0.233 | 2.068 | 0.627-6.821 | |||

| FIGO stage | <0.001 | 13.525 | 4.741-38.583 | <0.001 | 16.975 | 4.51-63.897 |

| T stage | <0.001 | 13.525 | 4.741-38.583 | NA | NA | NA |

| N stage | <0.001 | 5.363 | 2.689-10.7 | 0.361 | 1.463 | 0.647-3.306 |

Table 3B.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of the factors correlated with Overall survival of uterine cervix cancer patients

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p value | HR | 95%CI | p value | HR | 95%CI | |

| Expression | 0.025 | 2.525 | 1.123-5.681 | 0.14 | 1.966 | 0.801-4.827 |

| Age | 0.002 | 6.453 | 1.967-21.164 | 0.013 | 4.599 | 1.374-15.397 |

| Grade stage | 0.233 | 2.068 | 0.627-6.821 | |||

| FIGO stage | <0.001 | 13.525 | 4.741-38.583 | <0.001 | 12.332 | 3.44-44.21 |

| T stage | <0.001 | 13.525 | 4.741-38.583 | NA | NA | NA |

| N stage | <0.001 | 5.363 | 2.689-10.7 | 0.258 | 1.609 | 0.705-3.671 |

Cyclin D1 is down-regulated or up-regulated in C33A model cells

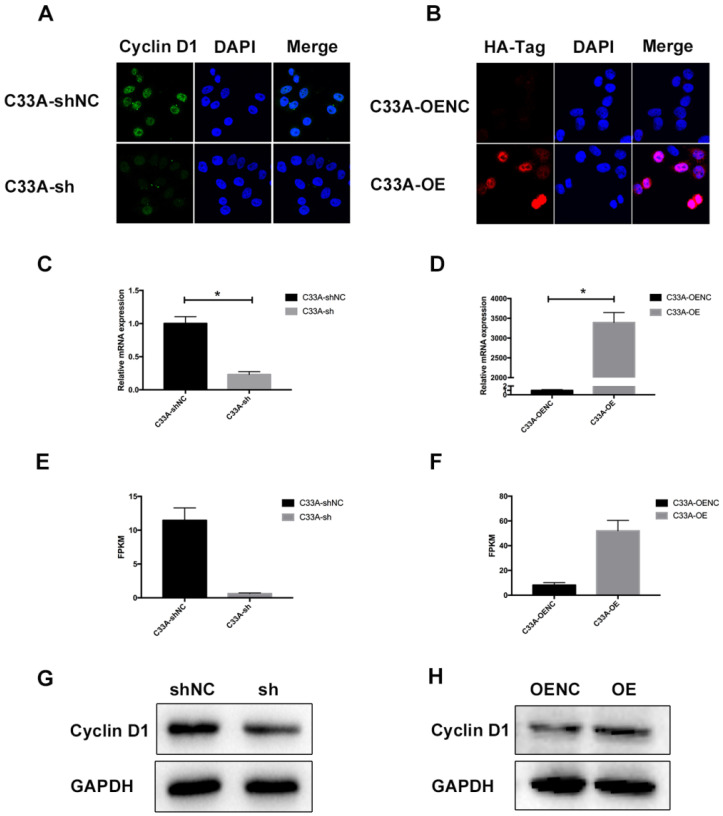

It was demonstrated that we have successfully established the cyclin D1 knock-in C33A and cyclin D1 knock-down C33A by western blotting (Fig. 2G-H). Immunofluorescence assay was also performed so that we could assess the subcellular localization of cyclin D1 in these cells where the green staining represents the cyclin D1 protein and the blue staining represents the nucleolus, and the red staining represents the HA-Tag and the blue staining represents the nucleolus (Fig. 2A-B). As shown in the Figure, most cyclin D1 protein are localized in the nucleus of cervical cancer cells. Furthermore, we also detected the relative mRNA expression of cyclin D1 by real-time PCR (Fig. 2C-D), and the FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million fragments mapped) by RNA-seq (Fig. 2E-F). These results indicated that we successfully established stable transfected cell lines of C33A.

Figure 2.

Cyclin D1 is down-regulated or up-regulated in C33A model cells. (A and B) Immunofluorescence assay was performed in order to assess the subcellular localization of cyclin D1 in these cells where the green staining represents the cyclin D1 protein and the blue staining represents the nucleolus, and the red staining represents the HA-Tag and the blue staining represents the nucleolus (the magnification is 200X). (C and D) The relative mRNA expression of cyclin D1 was decreased in the C33A-sh cells compared to the C33A-shNC cells (P < 0.05), also increased in the C33A-OE cells compared to the C33A-OENC cells (P < 0.05). (E and F) The FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million fragments mapped) were measured by RNA-seq in C33A model cells, which were Statistically different (P < 0.05). (G and H) The results of western blotting demonstrated that we have successfully established the cyclin D1 knock-in C33A and cyclin D1 knock-down C33A.

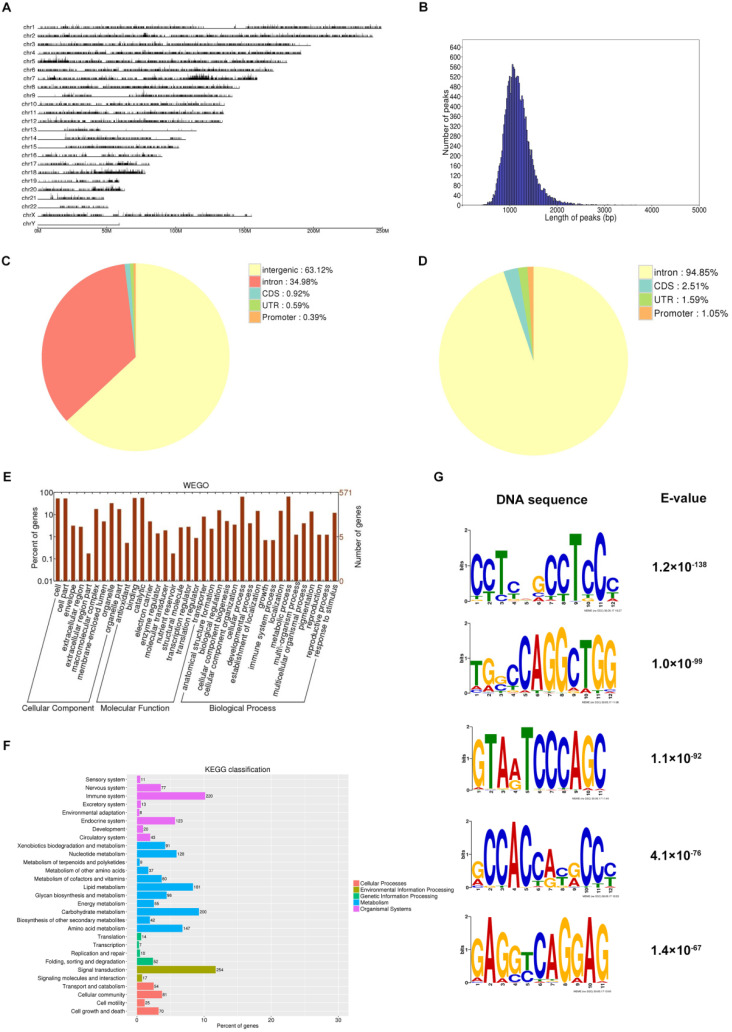

Analyses of cyclin D1 interaction with the C33A genome

Cyclin D1 occupies region of abundantly genes from the distribution of potential peak in genome (Fig. 3A), and the length of peaks focused on nearly 1000 bp (Fig. 3B). Most of the binding sites were located in intergenic or intron (Fig. 3C-D). Totally we detected 5590 genes involved in binding with cyclin D1 (Supplement 1), and we could find the function of these genes, for example, cellular component, molecular function, biological process; based on the functional annotation analysis, there were a large number of gene sets associated with signal transduction (Fig. 3E-F). We selected five examples of conserved TF motifs enriched within the interval regions associated with cyclin D1, which suggested that cyclin D1 bound promoter regions with a high content of CpG dinucleotide (Fig. 3G).

Figure 3.

Analyses of cyclin D1 interaction with the C33A genome. (A) Cyclin D1 occupies region of abundantly genes from the distribution of potential peak in genome. (B) The length of peaks mostly are between 500 and 2000, while focused on nearly 1000 bp. (C and D) Most of the binding sites were located in intergenic or intron. (E and F) The function of the downstream genes, for example, cellular component, molecular function, biological process; based on the functional annotation analysis, there were a large number of gene sets associated with signal transduction. (G) The TF motifs enriched within the interval regions associated with cyclin D1, which suggested that cyclin D1 bound promoter regions with a high content of CpG dinucleotide.

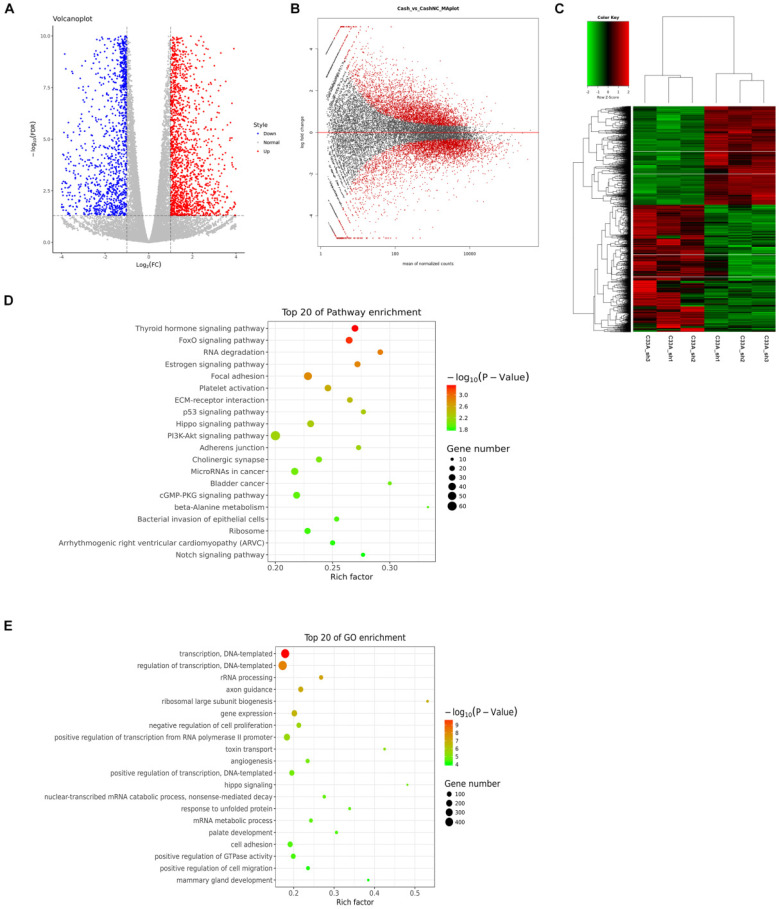

Analyses of differential genes in cyclin D1 knock-down C33A cells

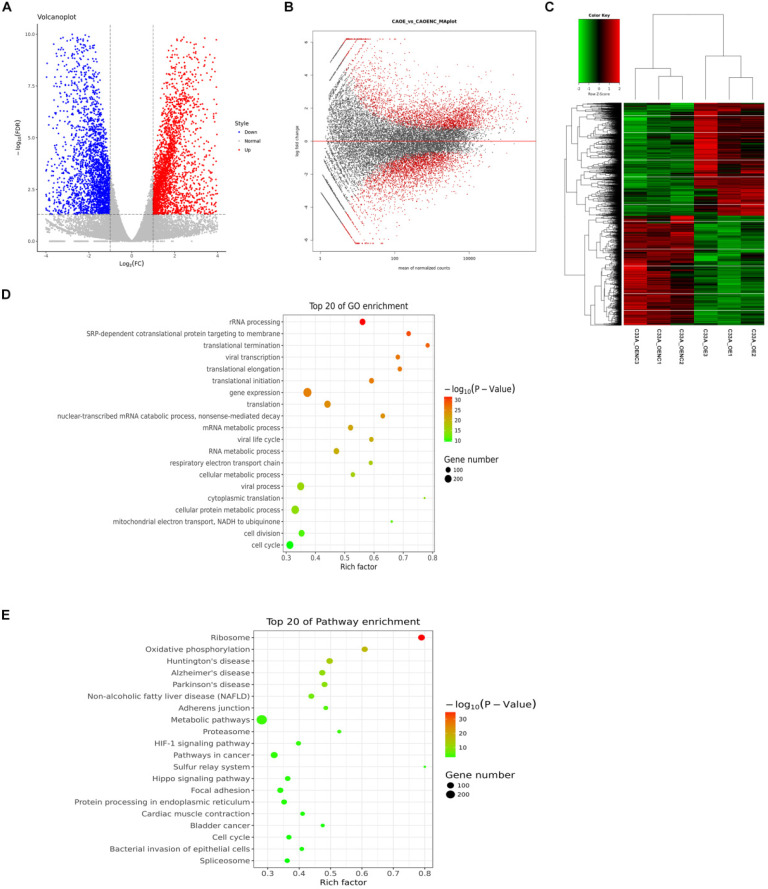

We set fold change ≥2 or fold change ≤1/2 and FDR< 0.05 as a standard for screening differential genes. We detected 2244 genes up-regulation, 1738 genes down-regulation in cyclin D1 knock-down cells by RNA-seq (Supplement 2-3). In Figure 4A, each dot represents a gene, the red dots represent up-regulated differentially expressed genes, the blue dots in the figure represent down-regulated differentially expressed genes, and the gray dots represent non-differentiated genes. In Figure 4B, the red dots represent differentially expressed genes, and the black dots represent non-differentiated genes. The heat maps displayed genes differentially regulated by cyclin D1, the three biological replicates also had good consistency from the hierarchical clustering analyses (Fig. 4C). We analyzed the differentially expressed genes with KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes: systematic analysis of gene function or genomic information database). We selected the top 20 of pathway enrichment which were most significant based on the Rich factor and p value, it was found that these genes involved several important pathways such as PI3K-Akt signaling pathway (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, we also selected the top 20 of pathway enrichment by GO-analysis (Gene Ontology), it was found that these genes involved several important pathways such as transcription (Fig. 4E).

Figure 4.

Analyses of differential genes in cyclin D1 knock-down C33A cells. (A and B) Each dot represents a gene, the red dots represent up-regulated differentially expressed genes, the blue dots in the figure represent down-regulated differentially expressed genes, and the gray dots represent non-differentiated genes. While the red dots represent differentially expressed genes, and the black dots represent non-differentiated genes. (C) The heat maps displayed genes differentially regulated by cyclin D1, the three biological replicates also had good consistency from the hierarchical clustering analyses. (D) The differentially expressed genes with KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes: systematic analysis of gene function or genomic information database). We selected the top 20 of pathway enrichment which were most significant based on the Rich factor and p value, it was found that these genes involved several important pathways such as PI3K-Akt signaling pathway. (E) The top 20 of pathway enrichment by GO-analysis (Gene Ontology), it was found that these genes involved several important pathways such as transcription.

Analyses of differential genes in cyclin D1 knock-in C33A cells

In the same way, we screened 2811 genes up-regulation, 2727 genes down-regulation in cyclin D1 knock-in cells by RNA-seq (Supplement 4-5). We could find that the down-regulated differentially expressed genes and the up-regulated differentially expressed genes from Figure 5A and 5B. The heat maps displayed genes differentially regulated by cyclin D1, the three biological replicates also had good consistency from the hierarchical clustering analyses (Fig. 5C). What's more, we analyzed the differentially expressed genes with KEGG and selected the top 20 of pathway enrichment which were most significant, it was found that these genes involved several important pathways such as metabolic pathways and pathways in cancer (Fig. 5E). We also selected the top 20 of pathway enrichment by GO-analysis, it was found that these genes involved several important pathways such as gene expression and transcription (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

Analyses of differential genes in cyclin D1 knock-in C33A cells. (A and B) The down-regulated differentially expressed genes and the up-regulated differentially expressed genes were picked out. (C) The heat maps displayed genes differentially regulated by cyclin D1 from the hierarchical clustering analyses. (D) The top 20 of pathway enrichment by GO-analysis (Gene Ontology), it was found that these genes involved several important pathways such as gene expression and transcription. (E) The differentially expressed genes with KEGG and selected the top 20 of pathway enrichment which were most significant, it was found that these genes involved several important pathways such as metabolic pathways and pathways in cancer.

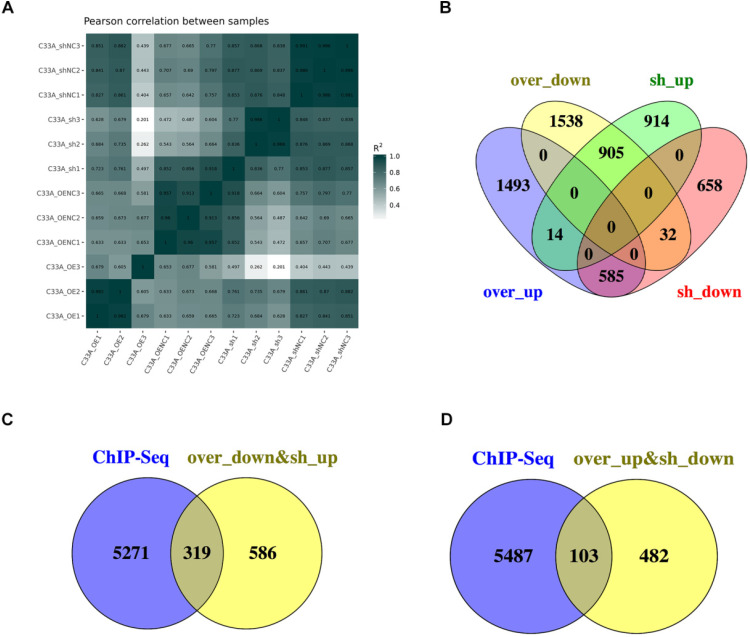

Analyses of combination the ChIP-seq with RNA-seq

The Pearson's correlation coefficient, R as an indicator of biological repeat relevance, whose square is closer to 1 represents the correlation is stronger. The most biological replicates had strong correlation from the Figure 6A. To find the downstream genes of cyclin D1, there were 905 genes in the intersection contained the 2244 genes which is up-regulation in cyclin D1 knock-down cells and 2727 genes down-regulation in cyclin D1 knock-in cells; 585 genes in the intersection contained the 1738 genes which is down-regulation in cyclin D1 knock-down cells and 2811 genes up-regulation in cyclin D1 knock-in cells (Fig. 6B). Combination with the ChIP-seq, it suggested that cyclin D1 could activate 103 genes expression and downregulate 319 genes expression by binding with DNA regions (Fig. 6C-D) (Supplement 6).

Figure 6.

Analyses of combination the ChIP-seq with RNA-seq. (A) The Pearson's correlation coefficient, R as an indicator of biological repeat relevance, whose square is closer to 1 represents the correlation is stronger. It was showed that the most biological replicates had strong correlation. (B) There were 905 genes in the intersection contained the 2244 genes which is up-regulation in cyclin D1 knock-down cells and 2727 genes down-regulation in cyclin D1 knock-in cells; 585 genes in the intersection contained the 1738 genes which is down-regulation in cyclin D1 knock-down cells and 2811 genes up-regulation in cyclin D1 knock-in cells. (C and D) Combination with the ChIP-seq, it suggested that cyclin D1 could activate 103 genes expression and downregulate 319 genes expression by binding with DNA regions.

Discussion

As we know, nuclear cyclin D1 accumulation results into uncontrolled cell cycle progression and oncogenesis 27. Most researches about cyclin D1 focus on the cell cycle progression, to form a cyclin D-CDK4/CDK6 complex and phosphorylate the Rb protein. Hyperphosphorylation of Rb leads to the release of the E2F family transcription factors and the activation of the transcriptional genes that control cell cycle progression, development, and metabolism 28-30. Some studies reported that cyclin D1 governs DNA damage repair through recruiting DNA repair complexes 21, 31-33.

It remains unclear how the molecular patterns described here are established and maintained, but with the advancement of technology in recent years, it is convenient for us to investigate the genome size, transcription factor binding sites, transcript discovery, and the expression quantification by deep DNA sequencing methods (ChIP-seq and RNA-seq) 34. But we have not found the researches concerning the new function of cyclin D1 on human cancer cells. In order to find the clinic correlation of cyclin D1, we analyzed the correlation of the cyclin D1 expression levels and prognosis of cervical cancer patients in tissue microarray (TMA) cohort. We found that there was no significant difference of cyclin D1 expression between cancer and adjacent tissues, which may due to lack of enough samples. The expression of cyclin D1 in the cytoplasm or nucleus was connected with age and grade (p<0.05). High expression of cyclin D1 in the cytoplasm or nucleus was significantly associated with poor survival. What's more, high expression of cyclin D1 in the nucleus was significantly associated with shorter OS and DFS. Then, in order to find and confirm that the transcriptional role of cyclin D1 in cervical cancer, we performed the ChIP-seq and RNA -seq on the C33A cells. We found that cyclin D1 was localized in the nucleus by immunofluorescence staining, which occupied abundantly DNA sequences. Our finding confirmed the finding of Bienvenu, F et al. mentioned that during mouse development cyclin D1 occupies promoters of abundantly expressed genes as a transcriptional role, in this research they found the cyclin D1-bound promoters were highly enriched for CpG dinucleotide (P<1X10-15) 20, because it has been proved that genes that are highly expressed in many tissues were shown to have a high content of CpG dinucleotides in their promoter regions 35. Then, we found the expression of abundantly genes changed as the expression of cyclin D1 changed, which suggested that cyclin D1 could serve both to activate and downregulate gene expression. To find out the genes whose expression changed as a result of cyclin D1-bound promoters, we analyzed the data of ChIP-seq and RNA seq. 422 genes were distinguished, of which 103 genes were positive correlation with the expression of cyclin D1 and 319 genes were negative correlation with the expression of cyclin D1.

Here, we found the clinic correlation of cyclin D1 which related to prognosis, and then conducted a genome-wide analysis of cyclin D1 binding in the context of local chromatin by using ChIP-seq analysis. The intrinsic DNA sequence-specific binding of cyclin D1 can be conjectured by the motifs. But it is still not very clear how the cyclin D1 protein is recruited to DNA, a study proposed it could be recruited to DNA through sequence-specific binding proteins 22, 33. The main discovery of this work is the demonstration that cyclin D1 plays a transcriptional function in cervical cancer cell line C33A by acting at gene promoters. Although our mechanistic analyses focused on the downstream genes, it remains to be seen whether this transcriptional function contributes to cellular component, molecular function and biological process, such as PI3K signaling pathway. It will be also of interest to determine whether this function of cyclin D1 contributes to oncogenesis and tumor development.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our investigation improves the study about the clinic correlation and function of cyclin D1, because it not only has the function of regulating the cell cycle and it is not necessary for pRB-negative cancer cells to proliferation such as HeLa 36, 37. We find the downstream genes are highly enriched in Gene Ontology categories and involve in diverse cellular functions via KEGG classification, including translation, replication and repair, signal transduction, cell growth and death, which means that cyclin D1 may be a key protein during oncogenesis and tumor development. It shows that cyclin D1 may be a potential therapeutic target in cancer therapy. However, the mechanisms of how these genes specifically affect the biological behavior of tumors and their development still require further research.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81472799), and Project of Hubei Medical Talents Training Program. The authors thank members of Hubei Key Laboratory of Tumor Biological Behaviors for helping to process the study.

Author Contributions

FX Zhou and YF Zhou designed and guided the experiments. YD Xiong and Y Wang performed major experiments and analyzed data. TQ Li, XY Yu, YY Zeng and GH Xiao assisted partly experiments. YD Xiong wrote the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- CDK

cyclin-dependent kinase

- pRb

retinoblastoma gene product

- ChIP-seq

chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by high-throughput sequencing

- RNA-seq

RNA-sequencing

- HA-Tag

human influenza hemagglutinin tag

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- FPKM

fragmentsper kilobase of transcript per million fragments mapped

- TF motifs

transcription factor motifs

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R. et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitzmaurice C, Abate D, Abbasi N. et al. Global, Regional, and National Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived With Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life-Years for 29 Cancer Groups, 1990 to 2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(12):1749–1768. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.2996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malumbres M, Barbacid M. Cell cycle, CDKs and cancer: a changing paradigm. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(3):153–166. doi: 10.1038/nrc2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang C, Li Z, Lu Y. et al. Cyclin D1 repression of nuclear respiratory factor 1 integrates nuclear DNA synthesis and mitochondrial function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(31):11567–11572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603363103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burandt E, Grunert M, Lebeau A. et al. Cyclin D1 gene amplification is highly homogeneous in breast cancer. Breast Cancer-Tokyo. 2016;23(1):111–119. doi: 10.1007/s12282-014-0538-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcea G, Neal CP, Pattenden CJ, Steward WP, Berry DP. Molecular prognostic markers in pancreatic cancer: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41(15):2213–2236. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Musgrove EA, Caldon CE, Barraclough J, Stone A, Sutherland RL. Cyclin D as a therapeutic target in cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2011;11(8):558–572. doi: 10.1038/nrc3090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santarius T, Shipley J, Brewer D, Stratton MR, Cooper CS. A census of amplified and overexpressed human cancer genes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(1):59–64. doi: 10.1038/nrc2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gautschi O, Ratschiller D, Gugger M, Betticher DC, Heighway J. Cyclin D1 in non-small cell lung cancer: a key driver of malignant transformation. Lung Cancer. 2007;55(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Leary B, Finn RS, Turner NC. Treating cancer with selective CDK4/6 inhibitors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016;13(7):417–430. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beaver JA, Amiri-Kordestani L, Charlab R. et al. FDA Approval: Palbociclib for the Treatment of Postmenopausal Patients with Estrogen Receptor-Positive, HER2-Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(21):4760–4766. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hortobagyi GN, Stemmer SM, Burris HA. et al. Ribociclib as First-Line Therapy for HR-Positive, Advanced Breast Cancer. New Engl J Med. 2016;375(18):1738–1748. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1609709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sosman JA, Kittaneh M, Lolkema MPJK. et al. A phase 1b/2 study of LEE011 in combination with binimetinib (MEK162) in patients with NRAS-mutant melanoma: Early encouraging clinical activity. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(Suppl.15):9009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knudsen ES, Witkiewicz AK. The Strange Case of CDK4/6 Inhibitors: Mechanisms, Resistance, and Combination Strategies. Trends Cancer. 2017;3(1):39–55. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Min A, Kim JE, Kim YJ. et al. Cyclin E overexpression confers resistance to the CDK4/6 specific inhibitor palbociclib in gastric cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2018;430:123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiong Y, Li T, Assani G. et al. Ribociclib, a selective cyclin D kinase 4/6 inhibitor, inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis of human cervical cancer in vitro and in vivo. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;112:108602. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.108602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teh JLF, Aplin AE. Arrested Developments: CDK4/6 Inhibitor Resistance and Alterations in the Tumor Immune Microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(3):921–927. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park PJ. ChIP-seq: advantages and challenges of a maturing technology. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(10):669–680. doi: 10.1038/nrg2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bienvenu F, Jirawatnotai S, Elias JE. et al. Transcriptional role of cyclin D1 in development revealed by a genetic-proteomic screen. Nature. 2010;463(7279):374–378. doi: 10.1038/nature08684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jirawatnotai S, Hu YD, Michowski W. et al. A function for cyclin D1 in DNA repair uncovered by protein interactome analyses in human cancers. Nature. 2011;474(7350):230–234. doi: 10.1038/nature10155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Casimiro MC, Crosariol M, Loro E. et al. ChIP sequencing of cyclin D1 reveals a transcriptional role in chromosomal instability in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(3):833–843. doi: 10.1172/JCI60256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bailey TL, Elkan C. Fitting a mixture model by expectation maximization to discover motifs in biopolymers. Proc Int Conf Intell Syst Mol Biol. 1994;2:28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12(4):357–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11(10):R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barry WT, Nobel AB, Wright FA. Significance analysis of functional categories in gene expression studies: a structured permutation approach. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(9):1943–1949. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alt JR, Cleveland JL, Hannink M, Diehl JA. Phosphorylation-dependent regulation of cyclin D1 nuclear export and cyclin D1-dependent cellular transformation. Gene Dev. 2000;14(24):3102–3114. doi: 10.1101/gad.854900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burkhart DL, Sage J. Cellular mechanisms of tumour suppression by the retinoblastoma gene. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(9):671–682. doi: 10.1038/nrc2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kato J, Matsushime H, Hiebert SW, Ewen ME, Sherr CJ. Direct binding of cyclin D to the retinoblastoma gene product (pRb) and pRb phosphorylation by the cyclin D-dependent kinase CDK4. Genes Dev. 1993;7(3):331–342. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kato JY, Sherr CJ. Inhibition of granulocyte differentiation by G1 cyclins D2 and D3 but not D1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(24):11513–11517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sakamaki T, Casimiro MC, Ju XM. et al. Cyclin D1 determines mitochondrial function in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(14):5449–5469. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02074-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fu MF, Rao M, Bouras T. et al. Cyclin D1 inhibits peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma-mediated adipogenesis through histone deacetylase recruitment. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(17):16934–16941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500403200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang C, Fan S, Li Z. et al. Cyclin D1 antagonizes BRCA1 repression of estrogen receptor alpha activity. Cancer Res. 2005;65(15):6557–6567. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pepke S, Wold B, Mortazavi A. Computation for ChIP-seq and RNA-seq studies. Nat Methods. 2009;6(11 Suppl):S22–32. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saxonov S, Berg P, Brutlag DL. A genome-wide analysis of CpG dinucleotides in the human genome distinguishes two distinct classes of promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(5):1412–1417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510310103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bates S, Parry D, Bonetta L, Vousden K, Dickson C, Peters G. Absence of cyclin D/cdk complexes in cells lacking functional retinoblastoma protein. Oncogene. 1994;9(6):1633–1640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lukas J, Parry D, Aagaard L. et al. Retinoblastoma-protein-dependent cell-cycle inhibition by the tumour suppressor p16. Nature. 1995;375(6531):503–506. doi: 10.1038/375503a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data.