Abstract

Objectives

To investigate superiority of a telerehabilitation programme for COVID-19 (TERECO) over no rehabilitation with regard to exercise capacity, lower limb muscle strength (LMS), pulmonary function, health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and dyspnoea.

Design

Parallel-group randomised controlled trial with 1:1 block randomisation.

Setting

Three major hospitals from Jiangsu and Hubei provinces, China.

Participants

120 formerly hospitalised COVID-19 survivors with remaining dyspnoea complaints were randomised with 61 allocated to control and 59 to TERECO.

Intervention

Unsupervised home-based 6-week exercise programme comprising breathing control and thoracic expansion, aerobic exercise and LMS exercise, delivered via smartphone, and remotely monitored with heart rate telemetry.

Outcomes

Primary outcome was 6 min walking distance (6MWD) in metres. Secondary outcomes were squat time in seconds; pulmonary function assessed by spirometry; HRQOL measured with Short Form Health Survey-12 (SF-12) and mMRC-dyspnoea. Outcomes were assessed at 6 weeks (post-treatment) and 28 weeks (follow-up).

Results

Adjusted between-group difference in change in 6MWD was 65.45 m (95% CI 43.8 to 87.1; p<0.001) at post-treatment and 68.62 m (95% CI 46.39 to 90.85; p<0.001) at follow-up. Treatment effects for LMS were 20.12 s (95% CI 12.34 to 27.9; p<0.001) post-treatment and 22.23 s (95% CI 14.24 to 30.21; p<0.001) at follow-up. No group differences were found for lung function except post-treatment maximum voluntary ventilation. Increase in SF-12 physical component was greater in the TERECO group with treatment effects estimated as 3.79 (95% CI 1.24 to 6.35; p=0.004) at post-treatment and 2.69 (95% CI 0.06 to 5.32; p=0.045) at follow-up.

Conclusions

This trial demonstrated superiority of TERECO over no rehabilitation for 6MWD, LMS, and physical HRQOL.

Trial registration number

ChiCTR2000031834.

Keywords: COVID-19, pulmonary rehabilitation

Key messages.

What is the key question?

Can functional exercise capacity, pulmonary function, lower limb muscle strength and quality of life of COVID-19 survivors discharged from hospital be improved with a telerehabilitation programme?

What is the bottom line?

Our study suggests that a telerehabilitation programme for COVID-19 survivors (TERECO) that is delivered via smartphone, remotely monitored and can be carried out at home was safe and improved functional exercise capacity, lower limb muscle strength and physical quality of life.

Why read on?

Many COVID-19 survivors worldwide suffer from persistent symptoms, impairment of function and reduced quality of life.

The TERECO programme is inexpensive and could be implemented on a large scale to improve physical health of COVID-19 survivors after discharge from hospital.

Introduction

After discharge from acute care, many survivors of COVID-19 experience ongoing symptoms, impairment of pulmonary function, decreased exercise capacity, reduced muscle strength, activity limitations and reduced quality of life.1–7 Problems may persist for at least 6 months.1 This indicates the need for the provision of rehabilitation services that can decrease the burden on patients and the health system.8 Pulmonary rehabilitation measures with demonstrated effectiveness in COPD9 and, with low-certainty evidence (one trial), SARS10 are obvious candidates.

Evidence from high-quality trials on the effectiveness of such programmes in COVID-19 survivors is, however, lacking to date.11 Moreover, delivery of conventional inpatient or outpatient rehabilitation is complicated through diminished capacity in postacute care as well as clinical and public health measures imposed to reduce the risk of viral transmission.12 Telerehabilitation provides a viable alternative that could be superior to no rehabilitation and as effective as conventional rehabilitation.13 14

We investigated possible superiority of a telerehabilitation programme for COVID-19 (TERECO) over no rehabilitation with regard to functional exercise capacity, lower limb muscle strength (LMS), pulmonary function, perceived dyspnoea and health-related quality of life in formerly hospitalised COVID-19 survivors. We further report on the occurrence of adverse events.

Methods

Study design

Multicentre, parallel-group randomised controlled trial. The original protocol for this study is available from (URL: http://idmr.scu.edu.cn/info.htm?id=1841614474692833).

Setting, recruitment and consent

Three centres from Jiangsu (Jiangsu Province Hospital/Nanjing Medical University First Affiliated Hospital), Hubei Wuhan (Hubei Province Hospital of Integrated Chinese and Western Medicine) and Hubei Huangshi (Hubei Huangshi Hospital of Chinese Medicine) recruited patients recovering from COVID-19. In total, 1242 patients had been discharged from these hospitals when we stopped recruitment on 28 May 2020 of which about one-third (n=377) was deemed potentially eligible after prescreening of hospital records. Possible candidates were then contacted by telephone and an appointment for a baseline visit was made. At this baseline visit, further assessment of eligibility was performed and written informed consent was obtained.

Participants

Participants were aged 18–75 years, discharged from one of the participating hospitals after inpatient treatment for COVID-19, and had modified British Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnoea15 score of 2–3. The latter inclusion criterion was chosen as we anticipated that patients with moderate remaining dyspnoea symptoms could actively participate in the programme and most benefit from it. Moreover, as this was an unsupervised intervention, patients with mMRC dyspnoea of 4–5 were excluded for reasons of safety. Other exclusion criteria were: resting heart rate over 100 bpm, uncontrolled hypertension, uncontrolled chronic disease (eg, diabetes with random blood glucose >16.7 mmol/L, haemoglobin A1C >7.0%), cerebrovascular disease within 6 months, intra-articular drug injection or surgical treatment of lower extremities within 6 months, taking medication affecting cardiopulmonary function such as bronchodilators or β-blockers, unable to walk independently with assistive device, unable or unwilling to collaborate with assessments, enrolled or participated in other trials within past 3 months, having history of severe cognitive or mental disorder or substance abuse, enrolment in other rehabilitation programme.

Random sequence generation and allocation concealment

Permutated allocation sequences for 1:1 block randomisation (block size 10–14) stratified by hospital were computer-generated by an independent statistician. Allocation was concealed by central randomisation and only revealed after baseline assessment through call to study centre.

Blinding of assessors

Baseline visits of each potential study participant involved one assessor (rehabilitation doctor) and one independent allocator (therapist). Assessors left the study site after the baseline measurements. Allocators then contacted the study centre in the presence of the patient to reveal allocation. Patients and therapists were requested to not disclose allocation to assessors at any time during the study.

Procedures

Control group

Participants in the control group received short educational instructions at baseline.

TERECO group

Participants took part in an unsupervised 6-week home exercise programme delivered through a smartphone application called RehabApp and monitored with a chest-worn heart rate (HR) telemetry device. Teleconsultations with therapists were carried out once per week. The exercise programme involved 3–4 sessions per week. It included (i) breathing control and thoracic expansion, (ii) aerobic exercise and (iii) LMS exercises specified in a three-tiered exercise plan with difficulty and intensity scheduled to increase over time. Initial exercise types and intensity were determined by physiotherapists contingent on the baseline assessment in accordance with the American College of Sports Medicine’s guidelines for exercise preparticipation.16 Exercise intensity prescribed for aerobic exercise was based on HR reserve determined by Karvonen’s formula.17 Intensity ranged from 30%–40% for tier 1 to 40%–60% for tier 3. Having reached at least two-thirds (66.7%) of the scheduled total and effective target time as given in online supplemental table S1 or modified by the therapist in any given week for at least 5 of the 6 weeks was considered compliant with the exercise protocol. Details on interventions and determination of compliance are provided in online supplemental text S1 and table S1.

thoraxjnl-2021-217382supp001.pdf (153.1KB, pdf)

Assessments

Assessments were conducted between 26 April and 9 December 2020. For each patient, home visits were scheduled at baseline, at 6 weeks (post-treatment) and at 24 weeks (follow-up). Additional assessments for dyspnoea and adverse events were performed by consultation via cell phone or WeChat voice call at 2 and 4 weeks. Due to a change of administrative regulations, home visits were no longer permitted for the final follow-up assessment. Participants were thus invited to return to the hospitals where they had originally received treatment. This adjustment led to a delay in the final assessment for about 4 weeks on average.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was functional exercise capacity at post-treatment measured with the 6 min walking test (6MWT) administered in accordance with guidelines from the European Respiratory Society and American Thoracic Society18 and recorded as 6 min walking distance (6MWD) in metres. For the first two assessment points a course was arranged outside, near the patients’ home. For the final follow-up assessment a course was arranged in the hospital ward according to the same criteria. In each case, the walking course was arranged on flat territory, hard surface, 30 m straight with every 3 m marked by coloured tape and two small cones placed at the turnaround points. Blood pressure was taken before and after the 6MWT and intermittently if indicated. HR and pulse-oxygen saturation were continuously monitored. If patients used walking aids in daily life (eg, rollator, cane), they were allowed to use those during the test. Patients could rest at any time and then continue the 6MWT based on their own assessment and that of the supervising therapist. If the 6MWT could not be completed, distance walked until final interruption was recorded.

Secondary outcomes

The 6MWD at follow-up was assessed as described in the previous section. LMS was measured with the static squat test.19 This involved a squat against the wall with both feet flat on the ground approximating a 90° angle at hip and knees. Time in seconds participants could remain in squatting position was recorded. Static testing was preferred over dynamic (eg, sit to stand) for ease of standardisation in the home setting. Pulmonary function was evaluated by spirometry according to guidelines of the American Thoracic Society (grade C).20 A portable pulmonary function device (MINATO, AS-507, Japan) was used. The following parameters were recorded: FEV1 in litres, FVC in litres, FEV1/FVC, maximum voluntary ventilation (MVV) in litres per minute and peak expiratory flow (PEF) in litres per second. Per cent of predicted value for FEV1, FVC and FEV1/FVC, and per cent below lower limit of normal (LLN) were calculated with Global Lung Initiative 2012 equations for South-East Asia.21 Per cent of predicted PEF and MVV were calculated with equations for mainland China.22 Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) was evaluated with the Short Form Health Survey-12 (SF-12).23 24 Physical component score (PCS) and mental component score (MCS) are reported, with higher scores indicating better health. Due to the absence of reference equations for mainland China scores were standardised according to US norms.24 Perceived dyspnoea was assessed with the mMRC scale.25 Since only patients with moderate dyspnoea (mMRC score of 2 or 3) were included in this study, being dyspnoea-free (mMRC score=0) was defined as a favourable outcome (coded 1 in analysis). All other mMRC scores were defined as non-favourable outcome (coded 0 in analysis).

Adverse events

Participants could report adverse events at any time during the study via phone call or WeChat message. They were also asked for adverse events during regular assessments. In addition, participants in the TERECO group received a prompt by RehabApp after each session and were asked for adverse events in weekly consultations with therapists. Death, cardiovascular events, other life-threatening events and re-hospitalisation for events related to the intervention or COVID-19 were defined as serious adverse events. All reported adverse events were rated by two independent doctors who had access to event and medical history but were blinded to group allocation. Severity was rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from very mild to life threatening. Relationship with the intervention was rated on a 3-point Likert scale (unlikely, possible, likely). Disagreement was resolved by discussion or, if necessary, involvement of a third reviewer.

Sample size

While a minimal important difference (MID) of 30 m is recommended for the 6MWT in chronic lung disease,26 an MID for COVID-19 has not yet been established. Given limited knowledge about the long-term course of COVID-19 including spontaneous recovery, a more conservative MID of 50 m was assumed. With 80% power and 5% alpha error, a sample size of 96 participants (48 per group) was needed to detect a statistically significant signal for a between-group difference in mean change in 6MWD. We assumed SD 99 in the control and SD 71 in the intervention group as reported for a trial in patients with SARS that randomly assigned 62 patients to control and 71 to intervention.10 The latter trial reported a between-group difference in mean change of 56.7 m in favour of the intervention group which is close to the MID supposed here. Assuming 20% attrition we aimed to recruit 120 participants.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed with STATA V.14.0. Main analyses were conducted on intention-to-treat (ITT) basis without imputations. Statistical significance was set at alpha=5% with two-sided tests. Data were assumed to be missing at random (MAR) with missing values depending on observed model parameters.27 This assumption was tested with sensitivity analysis. The statistical analysis plan (SAP) is available in online supplemental material S2.

thoraxjnl-2021-217382supp002.pdf (2.2MB, pdf)

The 6MWD was evaluated with constrained longitudinal data analysis, that is a linear mixed effects model that imposed an equality constraint on baseline means.28 29 Analogous to analysis of covariance, such equality constraint is imposed to counteract regression to the mean, that is, the statistical phenomenon that a group of patients with worse average baseline scores generally improves more than the group with better scores, independent of a possible intervention effect.30 The model was adjusted for centre (fixed effect) and dependence of longitudinal observations within study participants was modelled with a random intercept. Parameters for interaction terms between time and treatment represent the estimated treatment effects at post-treatment and follow-up, and are reported with 95% CIs. All secondary outcomes apart from mMRC-dyspnoea were analysed analogously. Occurrence of a favourable outcome in mMRC-dyspnoea was analysed with a generalised linear model of the Poisson family with a log link, adjusted for centre and using the natural logarithm of the number of observed occasions until the respective data point as offset. Cluster robust SEs (cluster variable: participant ID; number of clusters: 115, average cluster size: 3.9 (min 1, max 4)) were used for the estimation of 95% CIs.31 Treatment effects are presented as rate ratios (RR) along with logistic 95% CIs. A graphical illustration of trajectories presents estimated marginal means and probabilities (mMRC-dyspnoea) as predicted with the above models by intervention group and time point with 84% CIs (logistic CIs for mMRC) serving as comparisons bars. In contrast to 95% CIs, 84% CIs allow for visual inspection of statistical significance of mean differences at the 5% level by looking at non-overlap of CI bounds for the group means.32

Prespecified sensitivity analysis included estimation of the above models on the per-protocol sample, as well as on two types of multiply imputed datasets. First, multiple imputation with chained equations33 (70 sets) was performed under an extended MAR assumption, that is, that missing values were also dependent on observed values of auxiliary variables not included in aforementioned models (gender, age, disease severity, time from hospital admission to baseline assessment, presence of comorbidities, smoking history, body mass index). Second, controlled multiple imputation (50 sets) was used for simulating a non-MAR scenario where patients with missing assessments in the TERECO group followed the pattern of change in controls (copy increments in reference (CIR)).34

As a delay in the planned follow-up assessment occurred for several patients and unequal time periods between post-treatment and follow-up assessment resulted, additional post hoc sensitivity analysis was conducted, fitting models with two additional terms for time since onset of symptoms (TOS) and TOS squared.

Analysis of harms

Adverse events were descriptively analysed.

Protocol deviations

Deviations from the study protocol and SAP are described and explained in detail in online supplemental material S3.

thoraxjnl-2021-217382supp003.pdf (99.5KB, pdf)

Role of the funding source

Funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of this report. The corresponding author had full access to all data in the study and final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Figure 1 illustrates the flow of patients through the study. After prescreening of hospital records, 140 patients were contacted for further evaluation of eligibility between 22 April and May 28 2020. Of those 20 were ineligible or refused consent. One hundred twenty patients were randomised with one person in the TERECO group and one in the control group not receiving the allocated intervention. One patient was withdrawn from the TERECO group before the start of the exercise programme due to premature beat. One patient in the control group had been randomised mistakenly because the assessor forgot to inform the allocator about the patient’s ineligibility due to refusal to collaborate in baseline assessments. Six patients of the TERECO group did not complete the post-treatment assessment. Two patients who discontinued the intervention, one because of chest pain and one for unspecified reasons, missed the post-treatment assessment but returned for the follow-up assessment. We had lost contact with four additional patients in the TERECO group and five patients from the control group at the final follow-up point. Overall, 36 participants in the TERECO group complied with the exercise protocol, 61.02% of those randomised (n=59) and 69.2% of those who remained in the programme for the full 6 weeks (n=52). Compliance increased until week 4, dropped in week 5 and increased again in week 6. More information on missing data and compliance with the exercise protocol is given in online supplemental material S4.

Figure 1.

Flow of patients through the study. ITT, intention to treat; PP, per protocol.

thoraxjnl-2021-217382supp004.pdf (208.9KB, pdf)

Baseline characteristics of the study participants by intervention group are provided in table 1. The overall mean age of the study population was 50.61 (SD 10.98), 53 (44.5%) were male and 73 (61.3%) had at least one comorbidity. Length of hospital stay for acute treatment was 26.2 days on average (SD 15.3). Time from hospital discharge to baseline assessment was 70 days on average (SD 16.9). Fifty (43.5%) patients were below LLN for FEV1, 45 (39.1%) for FVC and 26 (22.6%) for FEV1/FVC.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics and outcomes at baseline

| Descriptor | Total (n=119*) |

Control (n=60*) | Intervention (n=59*) |

| Demographics | |||

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 50.61 (10.98) | 52.03 (11.10) | 49.17 (10.75) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 53 (44.5) | 26 (43.3) | 27 (45.8) |

| Female | 66 (55.5) | 34 (56.7) | 32 (54.2) |

| In-hospital treatment modalities | |||

| Days from onset to admission, mean (SD) | 7.47 (9.80) | 7.05 (10.60) | 7.90 (8.97) |

| Disease severity†, n (%) | |||

| Not severe | 81 (68.1) | 44 (73.3) | 37 (62.7) |

| Severe | 38 (31.9) | 16 (26.7) | 22 (37.3) |

| Oxygen support or non-invasive ventilation, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 103 (86.6) | 54 (90.0) | 49 (83.1) |

| Treatment with corticosteroids, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 49 (41.2) | 23 (38.3) | 26 (44.1) |

| Length of inpatient stay, mean (SD) | 26.18 (15.25) | 23.73 (11.00) | 28.66 (18.37) |

| Medical history (baseline) | |||

| Comorbidity presence, n (%) | |||

| None | 46 (38.7) | 21 (35.0) | 25 (42.4) |

| Single | 45 (37.8) | 24 (40.0) | 21 (35.6) |

| Multi | 28 (23.5) | 15 (25.0) | 13 (22.0) |

| Comorbidity types, n (%) | |||

| Heart disease | 9 (7.6) | 7 (11.7) | 2 (3.4) |

| Hypertension | 26 (21.9) | 18 (30.0) | 8 (13.6) |

| Diabetes | 17 (14.3) | 9 (15.0) | 8 (13.6) |

| Obesity | 17 (14.3) | 8 (13.33) | 9 (15.3) |

| Lung disease (including inactive TB) | 7 (5.9) | 3 (5.0) | 4 (6.8) |

| Other comorbidity | 28 (23.5) | 12 (20.0) | 16 (27.1) |

| Smoking history, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 15 (12.6) | 6 (10.0) | 9 (15.3) |

| Trial information | |||

| Days from hospital discharge to baseline, mean (SD) | 70.07 (16.85) | 71.15 (13.22) | 68.97 (19.94) |

| Days from baseline to post-treatment assessment, mean (SD)‡ | 42.86 (2.12) | 43.02 (1.87) | 42.67 (2.37) |

| Days from baseline to follow-up assessment, mean (SD)§ | 197.30 (8.41) | 196.87 (8.26) | 197.78 (8,62) |

| Outcomes (baseline) | |||

| 6MWD (m), mean (SD) | 507.18 (88.27) | 499.98 (93.41) | 514.52 (82.87) |

| Squat time (s), mean (SD) | 36.66 (23.51) | 38.60 (25.07) | 34.68 (21.85) |

| Spirometry¶ | |||

| FEV1 (L), mean (SD) | 2.19 (0.71) | 2.14 (0.69) | 2.24 (0.74) |

| FEV1 (% predicted), mean (SD) | 78.53 (16.86) | 77.95 (15.45) | 79.10 (18.25) |

| FEV1 below LLN, n (%) | 50 (43.5) | 24 (42.1) | 26 (44.8) |

| FVC (L), mean (SD) | 2.77 (0.82) | 2.69 (0.87) | 2.85 (0.75) |

| FVC (% predicted), mean (SD) | 82.04 (15.20) | 80.43 (15.39) | 83.62 (14.99) |

| FVC below LLN, n (%) | 45 (39.1) | 22 (38.6) | 23 (39.7) |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.80 (0.13) | 0.81 (0.12) | 0.79 (0.14) |

| FEV1/FVC (% predicted), mean (SD) | 96.43 (15.93) | 97.86 (15.03) | 95.03 (16.78) |

| FEV1/FVC below LLN, n (%) | 26 (22.6) | 12 (21.1) | 14 (24.1) |

| MVV (L/min) | 68.72 (28.90) | 63.05 (26.12) | 74.30 (30.60) |

| MVV (% predicted), mean (SD) | 62.69 (22.13) | 58.94 (20.86) | 66.37 (22.88) |

| PEF (L/s) | 3.93 (2.07) | 3.66 (1.75) | 4.21 (2.33) |

| PEF (% predicted), mean (SD) | 48.94 (21.77) | 46.41 (18.20) | 51.42 (24.70) |

| SF-12 PCS, mean (SD) | 39.42 (7.09) | 39.69 (7.06) | 39.15 (7.16) |

| SF-12 MCS, mean (SD) | 44.40 (8.48) | 44.13 (8.25) | 44.67 (8.76) |

| mMRC-dyspnoea, n (%) | |||

| 2 ‘On level ground, walks slower than people of same age because of breathlessness or has to stop for breath when walking at own pace’. | 116 (97.5) | 58 (96.7) | 58 (98.3) |

| 3 ‘Stops for breath after walking about 100 yards or after a few minutes on level ground’. | 3 (2.5) | 2 (3.3) | 1 (1.7) |

*Unless otherwise stated.

†Cases were defined as severe when patients met one of the following criteria at any time during hospitalisation: acute respiratory distress, respiratory rate ≥30 breath/min; pulse oxygen saturation (SpO2) ≤93% at rest; arterial blood partial pressure of oxygen/fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) ≤300 mm Hg (1 mm Hg=0.133 kPa); respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation; septic shock; failure of other organs requiring intensive care unit treatment.42

‡n=112 (control=60, intervention=52).

§n=105 (control=55, intervention=50).

¶For spirometry n=115 (control=57, intervention=58); one baseline value missing, three invalid entries in case record form. FEV1, FCV, FEV1/FVC predictions and lower limits of normal according to Global Lung Initiative 2012,21 MVV, PEF predictions according to Mu and Liu.22

MCS, mental component score; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; MVV, maximum voluntary ventilation; PCS, physical component score; PEF, peak expiratory flow; SF-12, Short Form Health Survey-12.

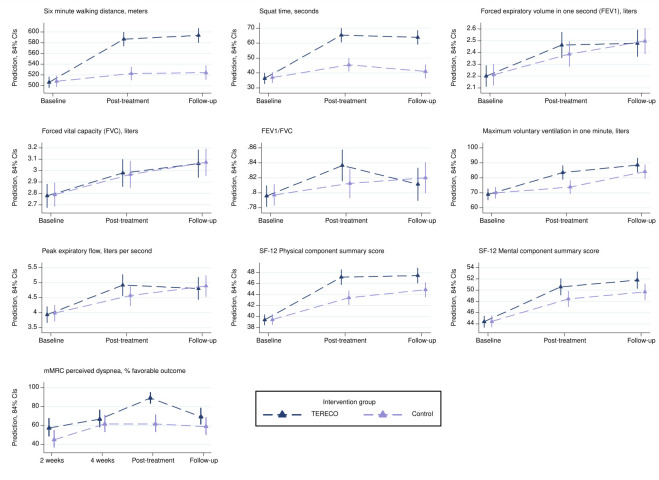

Table 2 gives an overview of crude change and adjusted treatment effects for all outcomes. Figure 2 depicts marginal trajectories over time by study group with 84% CIs (comparison bars) serving as a visual aid for inspecting statistical significance of mean differences at the 5% level (see online supplemental material S5 for detailed estimates).

Table 2.

Crude change in outcomes from baseline at the different assessment points and estimated adjusted treatment effects with 95% CIs (on intention-to-treat basis)

| Number of participants | Crude change from baseline* or % endorsing favourable outcome† | Estimated treatment effect (group difference in mean change‡ or risk ratio§) with 95% CI | P value¶ | |||

| Control | TERECO | Control | TERECO | |||

| Primary outcome | ||||||

| 6MWD (m) | ||||||

| Post-treatment (6 weeks) | 60 | 52 | 17.09±63.94 | 80.20±74.66 | 65.45 (43.80 to 87.10) | <0.001 |

| Follow-up (~28 weeks) | 55 | 50 | 15.17±70.02 | 84.81±80.38 | 68.62 (46.39 to 90.85) | <0.001 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||

| Squat time (s) | ||||||

| Post-treatment (6 weeks) | 60 | 52 | 7.98±19.53 | 29.35±27.22 | 20.12 (12.34 to 27.90) | <0.001 |

| Follow-up (~28 weeks) | 55 | 50 | 4.16±19.62 | 28.12±27.17 | 22.23 (14.24 to 30.21) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary function | ||||||

| FEV1 (L) | ||||||

| Post-treatment (6 weeks) | 56 | 51 | 0.18±0.53 | 0.28±0.51 | 0.08 (−0.08 to 0.25) | 0.327 |

| Follow-up (~28 weeks) | 53 | 47 | 0.29±0.43 | 0.29±0.48 | 0.00 (−0.18 to 0.17) | 0.969 |

| FVC (L) | ||||||

| Post-treatment (6 weeks) | 56 | 51 | 0.19±0.40 | 0.21±0.47 | 0.02 (−0.14 to 0.18) | 0.818 |

| Follow-up (~28 weeks) | 53 | 47 | 0.27±0.43 | 0.30±0.38 | 0.01 (−0.16 to 0.17) | 0.95 |

| FEV1/FVC | ||||||

| Post-treatment (6 weeks) | 56 | 51 | 0.01±0.16 | 0.04±0.17 | 0.03 (−0.02 to 0.07) | 0.224 |

| Follow-up (~28 weeks) | 53 | 47 | 0.02±0.15 | 0.02±0.18 | −0.01 (−0.05 to 0.03) | 0.732 |

| MVV (L/min) | ||||||

| Post-treatment (6 weeks) | 56 | 51 | 5.61±17.31 | 14.49±21.60 | 10.57 (3.26 to 17.88) | 0.005 |

| Follow-up (~28 weeks) | 53 | 47 | 13.81±20.78 | 18.47±22.31 | 5.20 (−2.33 to 12.73) | 0.176 |

| PEF (L/s) | ||||||

| Post-treatment (6 weeks) | 56 | 51 | 0.66±1.95 | 0.98±1.90 | 0.38 (−0.24 to 1.00) | 0.229 |

| Follow-up (~28 weeks) | 53 | 47 | 0.97±1.84 | 0.76±1.92 | −0.02 (−0.66 to 0.62) | 0.954 |

| Quality of life | ||||||

| SF-12 PCS | ||||||

| Post-treatment (6 weeks) | 60 | 52 | 3.84±7.60 | 7.81±7.02 | 3.79 (1.24 to 6.35) | 0.004 |

| Follow-up (~28 weeks) | 55 | 50 | 5.20±9.13 | 8.2±10.05 | 2.69 (0.06 to 5.32) | 0.045 |

| SF-12 MCS | ||||||

| Post-treatment (6 weeks) | 60 | 52 | 4.17±8.79 | 6.15±10.78 | 2.18 (−0.54 to 4.90) | 0.116 |

| Follow-up (~28 weeks) | 55 | 50 | 5.51±7.79 | 6.92±10.28 | 1.99 (−0.81 to 4.79) | 0.164 |

| mMRC perceived dyspnoea, to favourable outcome | ||||||

| Interim 2 weeks | 60 | 54 | 45.0 | 57.4 | 1.27 (0.88 to 1.82) | 0.197 |

| Interim 4 weeks | 60 | 54 | 61.7 | 66.7 | 1.08 (0.82 to 1.42) | 0.605 |

| Post-treatment (6 weeks) | 60 | 52 | 61.7 | 90.4 | 1.46 (1.17 to 1.82) | 0.001 |

| Follow-up (~28 weeks) | 55 | 50 | 60.0 | 72.0 | 1.22 (0.92 to 1.61) | 0.162 |

*Crude change from baseline is given as mean change±SD of this change for all outcomes apart from for mMRC (favourable outcome).

†For mMRC, per cent being dyspnoea-free is provided.

‡Estimated treatment effects for all outcomes apart from mMRC-dyspnoea (favourable outcome) are between-group mean differences in change from baseline derived from mixed effects regression with random intercept for study participant; models are constrained to a common baseline mean across groups and adjusted for centre. Estimation includes all available observations from participants randomised (number of participants with valid observations at baseline is 115 for pulmonary function parameters and 119 for all other outcomes).

§Estimated treatment effects for mMRC-dyspnoea (favourable outcome) are risk ratios derived from generalised linear model from Poisson family with log link adjusted for centre and ln(number valid observations up to data point) as offset; 95% CIs are based on cluster robust SEs (cluster variable: participant ID).

¶Probability of treatment effect being zero.

CI, confidence interval; MCS, mental component score; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; MVV, maximum voluntary ventilation; 6MWD, six min walking distance; PCS, physical component score; PEF, peak expiratory flow; SF-12, Short Form Health Survey-12; TERECO, telerehabilitation intervention for COVID-19 survivors.

Figure 2.

Marginal trajectories for outcomes estimated from models used for main analysis (intention to treat) and presented with visual comparison bars (84% CIs). Note that models for continuous outcomes impose equality constraints on baseline means, while some variation is reintroduced by adjustment for centre. Post-treatment is at 6 weeks after baseline and follow-up is at approximately 28 weeks after baseline (average). mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; SF-12, Short Form Health Survey-12; TERECO, telerehabilitation intervention for COVID-19 survivors.

thoraxjnl-2021-217382supp005.pdf (136.5KB, pdf)

Primary outcome

The mean 6MWD in the control group increased by 17.1 m (SD 63.9) from baseline to post-treatment assessment, whereas 6MWD in the TERECO group improved by 80.2 m (SD 74.7). The adjusted between-group difference in change in 6MWD from baseline (treatment effect) was 65.45 m (95% CI 43.8 to 87.1; p<0.001).

Secondary outcomes

With estimated 68.62 m (95% CI 46.39 to 90.85; p<0.001), the treatment effect regarding 6MWD increased somewhat at follow-up. LMS improved to a larger degree in the TERECO group as compared with control with estimated treatment effects of 20.12 s in squat position (95% CI 12.34 to 27.9; p<0.001) post-treatment, and 22.23 s (95% CI 14.24 to 30.21; p<0.001) at follow-up. Lung function parameters improved in both group over time (figure 2). No group differences were found apart from an adjusted between-group difference in change from baseline of 10.57 L/min (95% CI 3.26 to 17.88; p=0.005) in post-treatment MVV in favour of the TERECO group. SF-12 PCS increased to a larger degree in the TERECO group with treatment effects estimated as 3.79 points (95% CI 1.24 to 6.35; p=0.004) at post-treatment and 2.69 (95% CI 0.06 to 5.32; p=0.045) at follow-up. Improvement in SF-12 MCS was somewhat greater in the TERECO group but 95% CIs were also compatible with greater improvement in control at both assessment points. With 90.4% being dyspnoea-free (favourable outcome) in the TERECO group as opposed to 61.7% in the control group (adjusted RR 1.46, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.82; p=0.001), a treatment effect for mMRC-dyspnoea was found immediately after the intervention period but not at the other time points.

Sensitivity analysis

Estimates from sensitivity analysis are provided in table 3. Per-protocol analysis showed larger effect estimates for 6MWD and LMS. For the per-protocol sample the estimated between-group difference in change from baseline for the primary outcome was 72.25 m (95% CI 47.54 to 96.97; p>0.001). With the exception of 6MWD at follow-up, treatment effects were lowest under the CIR scenario, followed by the extended MAR scenario. A long-term effect of TERECO on SF-12 PCS was unstable in all preplanned sensitivity analyses. Estimates from post hoc sensitivity analysis that added parameters for TOS to the models were almost identical with those from main analysis.

Table 3.

Results of sensitivity analysis

| Outcome | Estimates of treatment effects from different scenarios with 95% CIs | ||||

| ITT, primary analysis (n=119, nint=59, nobs=336) |

Per protocol‡ (n=91, nint=36) |

ITT, extended MAR multiple imputation* (n=119, nint=59, 70 sets) |

ITT, CIR multiple imputation† (n=119, nint=59, 50 sets) |

ITT, model including time from symptoms onset§ (n=119, nint=59, nobs=336) |

|

| Primary outcome: 6MWD (m) | |||||

| Post-treatment (6 weeks) | 65.45 (43.80 to 87.10) | 72.25 (47.54 to 96.97) | 62.23 (40.07 to 84.39) | 57.18 (35.42 to 78.95) | 65.12 (44.50 to 85.74) |

| Follow-up (~28 weeks) | 68.62 (46.39 to 90.85) | 75.92 (51.21 to 100.64) | 61.99 (39.22 to 84.76) | 63.07 (40.87 to 85.27) | 67.99 (46.77 to 89.20) |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||

| Squat time (s) | |||||

| Post-treatment (6 weeks) | 20.12 (12.34 to 27.90) | 22.67 (13.91 to 31.43) | 20.32 (11.72 to 28.91) | 17.81 (10.01 to 25.61) | 20.15 (12.44 to 27.86) |

| Follow-up (~28 weeks) | 22.23 (14.24 to 30.21) | 25.94 (17.18 to 34.70) | 21.48 (12.73 to 30.24) | 20.07 (12.09 to 28.06) | 22.38 (14.45 to 30.31) |

| Pulmonary function | |||||

| FEV1 (L) | |||||

| Post-treatment (6 weeks) | 0.08 (−0.08 to 0.25) | 0.09 (−0.1 to 0.28) | 0.07 (−0.11 to 0.25) | 0.06 (−0.11 to 0.24) | 0.08 (−0.08 to 0.25) |

| Follow-up (~28 weeks) | 0.00 (−0.18 to 0.17) | −0.03 (−0.22 to 0.16) | −0.05 (−0.23 to 0.13) | 0.00 (−0.18 to 0.18) | 0.00 (−0.18 to 0.17) |

| FVC (L) | |||||

| Post-treatment (6 weeks) | 0.02 (−0.14 to 0.18) | 0.09 (−0.08 to 0.27) | −0.01 (−0.18 to 0.16) | 0.03 (−0.13 to 0.20) | 0.02 (−0.14 to 0.18) |

| Follow-up (~28 weeks) | 0.01 (−0.16 to 0.17) | 0.07 (−0.11 to 0.25) | −0.06 (−0.23 to 0.12) | 0.01 (−0.16 to 0.18) | 0.01 (−0.15 to 0.17) |

| FEV1/FVC | |||||

| Post-treatment (6 weeks) | 0.03 (−0.02 to 0.07) | 0.02 (−0.02 to 0.07) | 0.02 (−0.02 to 0.06) | 0.02 (−0.02 to 0.06) | 0.02 (−0.02 to 0.06) |

| Follow-up (~28 weeks) | −0.01 (−0.05 to 0.03) | −0.02 (−0.07 to 0.03) | −0.01 (−0.05 to 0.03) | 0.00 (−0.04 to 0.04) | −0.01 (−0.05 to 0.03) |

| MVV (L/min) | |||||

| Post-treatment (6 weeks) | 10.57 (3.26 to 17.88) | 14.3 (6.1 to 22.5) | 10.09 (2.11 to 18.07) | 10.32 (2.91 to 17.73) | 10.57 (3.3 to 17.85) |

| Follow-up (~28 weeks) | 5.20 (−2.33 to 12.73) | 7.29 (−1.00 to 15.59) | 3.04 (−5.38 to 11.46) | 6.01 (−1.77 to 13.78) | 5.25 (−2.27 to 12.76) |

| PEF (L/s) | |||||

| Post-treatment (6 weeks) | 0.38 (−0.24 to 1.00) | 0.52 (−0.17 to 1.22) | 0.35 (−0.29 to 0.99) | 0.35 (−0.29 to 0.99) | 0.38 (−0.24 to 1.00) |

| Follow-up (~28 weeks) | −0.02 (−0.66 to 0.62) | −0.16 (−0.86 to 0.55) | −0.18 (−0.83 to 0.48) | 0.03 (−0.62 to 0.67) | −0.03 (−0.67 to 0.61) |

| Quality of life | |||||

| SF-12 PCS | |||||

| Post-treatment (6 weeks) | 3.79 (1.24 to 6.35) | 3.70 (0.76 to 6.63) | 3.68 (1.13 to 6.24) | 3.27 (0.69 to 5.86) | 3.75 (1.22 to 6.27) |

| Follow-up (~28 weeks) | 2.69 (0.06 to 5.32) | 2.37 (−0.57 to 5.30) | 2.31 (−0.43 to 5.05) | 2.44 (−0.28 to 5.16) | 2.72 (0.12 to 5.33) |

| SF-12 MCS | |||||

| Post-treatment (6 weeks) | 2.18 (−0.54 to 4.90) | 1.92 (−1.14 to 4.97) | 2.17 (−0.57 to 4.91) | 1.65 (−1.07 to 4.38) | 2.18 (−0.53 to 4.89) |

| Follow-up (~28 weeks) | 1.99 (−0.81 to 4.79) | 1.48 (−1.58 to 4.54) | 2.30 (−0.48 to 5.09) | 1.82 (−0.96 to 4.61) | 1.93 (−0.87 to 4.73) |

| mMRC-dyspnoea, to favourable outcome | |||||

| Interim 2 weeks | 1.27 (0.88 to 1.82) | 1.33 (0.90 to 1.98) | 1.26 (0.87 to 1.81) | 1.26 (0.88 to 1.82) | 1.28 (0.89 to 1.85) |

| Interim 4 weeks | 1.08 (0.82 to 1.42) | 1.04 (0.76 to 1.42) | 1.06 (0.80 to 1.4) | 1.06 (0.80 to 1.40) | 1.09 (0.82 to 1.43) |

| Post-treatment (6 weeks) | 1.46 (1.17 to 1.82) | 1.43 (1.14 to 1.80) | 1.42 (1.13 to 1.79) | 1.40 (1.11 to 1.77) | 1.47 (1.17 to 1.84) |

| Follow-up (~28 weeks) | 1.22 (0.92 to 1.61) | 1.15 (0.84 to 1.57) | 1.21 (0.92 to 1.58) | 1.23 (0.92 to 1.63) | 1.23 (0.93 to 1.62) |

Apart from estimates for mMRC perceived dyspnoea (favourable outcome), estimates are between-group differences in mean change from baseline derived from linear mixed effects models adjusted for study centre (fixed effect) and with baseline means constrained to be equal across comparison groups. Estimates for mMRC perceived dyspnoea are rate ratios derived from a general linear mixed model of the Poisson family with log link adjusted for centre and ln(number valid observations up to data point) as offset. CIs are estimated with cluster robust standard errors (cluster variable: participant ID).

*Based on multiple imputation using chained equations assuming data were missing at random. The imputation model included all outcomes and the following auxiliary variables with complete baseline information: gender, age, smoking history (no vs yes), presence of any comorbidity (no vs yes), COVID-19 severity (non-severe vs severe), body mass index, time from admission to hospital to baseline assessment in days.

†Used reference-based controlled multivariate normal imputation for each outcome assuming increments in both comparison groups followed the observed pattern of the control group where data points were not observed. Auxiliary variables employed were as in the MAR model. After imputation adaptive rounding was used for imputed values of mMRC-dyspnoea (favourable outcome).

‡Based on per-protocol sample, that is, participants who completed all assessments and completed the intervention programme at or above minimum intensity and duration required for compliance as defined in the protocol (intervention group).

§Same as main analysis but providing additional adjustment for time from onset of symptoms to measurement point in days and time from onset of symptoms to measurement point in days squared. A likelihood ratio test confirmed superior fit of the model that also included the squared term.

CI, confidence interval; CIR, copy increments from reference; ITT, intention to treat; MAR, missing at random; MCS, mental component score; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; MVV, maximum voluntary ventilation; 6MWD, six min walking distance; PCS, physical component score; PEF, peak expiratory flow; SF-12, Short Form Health Survey-12.

Adverse events

No serious adverse events occurred during the study period. Eight patients (five in the TERECO and three in the control group) were hospitalised, all for non-life-threatening reasons unrelated to COVID-19 or the intervention and all in the follow-up period. A detailed account of adverse events is provided in online supplemental material S6 and table S6.1.

thoraxjnl-2021-217382supp006.pdf (132.9KB, pdf)

Discussion

In this trial, the TERECO programme was superior to no rehabilitation with regard to functional exercise capacity, LMS and physical HRQOL. All these effects could be sustained over a 7-month period. Pronounced differences in exercise capacity and LMS remained between intervention and control group. For physical HRQOL, the difference between TERECO and the control group decreased at follow-up due to improvements in controls. We also found a short-term effect of TERECO on MVV and mMRC-dyspnoea. Both effects, however, decreased at follow-up with differences no longer being statistically significant. No effects of TERECO on the four other pulmonary function parameters and on mental HRQOL were found. Adherence to the intervention programme was satisfactory and no serious adverse events occurred. While attrition and missing data may have influenced effect sizes, the estimates of exercise capacity and LMS in ITT analysis were consistent with MAR scenarios and more conservative estimates when non-MAR was assumed.

This study evaluated a relatively inexpensive, patient-centred, adaptable telerehabilitation intervention with a wide range of parameters of relevance to function and HRQOL. With a few exceptions, this trial was executed according to the original protocol and attrition was low (about 12%). Sensitivity analysis demonstrated stability of most results under different scenarios.

Limitations of this research include participant characteristics: only COVID-19 survivors with moderate dyspnoea symptoms who had previously been hospitalised for treatment were included. The results are thus not generalisable to persons with mild or severe dyspnoea, nor to people who contracted SARS CoV-2 but were not hospitalised. We further excluded patients taking β-blockers or bronchodilators precluding inference for this population. It should be noted that the intervention might not be suitable for people with very severe impairment and sequelae due to COVID-19 or those not familiar with smartphone technology. Another important weakness is the unexpected change of the location and resulting delay of the final follow-up assessment. It is unclear how this may have affected patient-reported assessments and pulmonary function testing. Low-certainty evidence (one randomised crossover trial) suggests that 6MWT performed outdoors yields comparable results to centre-based testing.35 Emerging evidence suggest that the most profound impairment of lung function in COVID-19 occurs in diffusion capacity.1 36 This was unclear at the time of study design and the required measurement procedures are difficult to perform at home. SDs of 6MWD used for sample size calculation were based on a study of patients with SARS.10 This was done for pragmatic reason as no respective data were available for COVID-19 in April 2020. However, although coronaviruses causing both diseases show some degree of genetic similarity, there are also some marked differences in genome and pathology.37 Future trials may thus refer to the growing body of research in patients with COVID-19. Finally, this trial was not powered for subgroup analysis and effect sizes in specific subpopulations hence remain unclear. For example, length of inpatient stay was longer, and the proportion of patients with severe COVID-19 was somewhat greater in the intervention group which may have enabled a larger effect size.

At the time of writing, there are no other randomised controlled studies on rehabilitation effectiveness for COVID-19. Demonstrating clinically meaningful and sustainable effects of the TERECO programme on 6MWD and LMS, this study adds to previous low-certainty evidence on the effectiveness of telerehabilitation in respiratory disease.14 The effect size for 6MWD in the present study at 6 weeks is comparable to results from a randomised controlled trial from Hong Kong,10 which evaluated a 6-week outpatient exercise programme for SARS survivors with baseline and post-treatment assessment. In contrast to our findings, the latter study did not detect any effects of the programme on HRQOL (SF-36) or LMS (measured as gluteus maximum and anterior deltoid strength with dynamometer). While a recent systematic review and meta-analysis reported superior effects of breathing exercise on lung function parameters (FEV1 and FEV1/FVC) as compared with control for COPD,38 no such effects were found in the present study. A possible explanation is that, in contrast to physical endurance and strength, lung function was not sufficiently targeted by the exercises included in the TERECO programme. This interpretation is supported by our finding that MVV was the only pulmonary parameter that showed a larger increase in TERECO than control at post-treatment. The MVV is not a measure of lung volume but rather of respiratory muscle strength and endurance.39 Obviously, the latter but not other lung function parameters were targeted by the breathing control and thoracic expansion exercises in the TERECO programme. Similar to the HRQOL physical component, mental HRQOL also improved in both groups but no statistically significant between-group differences in increments were detected, although the SF-12 MCS score of the TERECO group remained at about 2 points above control at follow-up. This result is difficult to interpret due to the unavailability of an MID for SF-12 in the target population. It is possible that our study was simply underpowered to detect a clinically relevant difference. In contrast, the proportion of patients free of subjective dyspnoea clearly decreased in the TERECO group between a peak at post-treatment and follow-up, returning to about the value at 4 weeks. This suggests that effects on perceived dyspnoea could not be sustained. It is further possible that the post-treatment effect in the participants of the TERECO group is partly due to their need to reduce cognitive dissonance,40 that is, after the completion of a 6-week exercise programme participants felt the cognitive need to change the perception of dyspnoea even if it had not objectively improved.

The TERECO programme is targeted at improving physical fitness including physical aspects of subjective HRQOL and should be applied in populations with moderate deficits. Clearly, other patients who have been hospitalised with COVID-19 will be in need of more comprehensive and interdisciplinary programmes. The programme can also not replace early rehabilitation delivered during acute treatment.41 Effects of the programme on pulmonary function seem largely absent while those on mental well-being remain unclear. Components better targeting these outcomes could be added in future evaluations of similar programmes. The TERECO programme appears to be safe but more mild adverse events occurred in the TERECO group in the first 6 weeks. The occurrence of uncomfortable symptoms during and after exercise can possibly be reduced by including additional resting periods and warm-up elements. The TERECO programme is inexpensive and suitable for large-scale implementation dependent on smartphone coverage, digital literacy and the availability of therapists for remote supervision and consultations.

Conclusions

The TERECO programme was superior over no rehabilitation with regard to functional exercise capacity, LMS and physical HRQOL. Only short-term effects were found for self-reported dyspnoea and MVV. Effects of the intervention on pulmonary function are otherwise unlikely and effects on mental aspects of quality of life are small at best.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate the work of all our colleagues from The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Hubei Province Hospital of Integrated Chinese and Western Medicine and Hubei Huangshi Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine who were involved in the conduct of this trial. Special thanks go to Dr Yongqiang Li, Puyang Zhang, Wei Zhang and Wenzhong Zou. We cordially thank all study participants and our other patients with COVID-19 for their feedback and ideas on how to design and improve the TERECO programme. We thank Jiayi Zhang for cross-checking the English translation of the Chinese protocol. We like to thank our friend and linguistics expert Dr Michael Herrera for his help with describing the different exercises. We are grateful to our friend Dr Andrew ‘Randy’ Pennycott for review of style and language. JR would like to thank Lili and Binhua Reinhardt for their patience and continuous support and Dr Dietrich Reinhardt for excellent discussions about the lung function parameters and other aspects of data interpretation.

Footnotes

JL, WX, CZ and SL contributed equally.

Contributors: JL, WX, CZha, SL and JR designed the study with support from ZY, JW, YC and CZhe; JL led the overall investigation and WX, CZha, SL and YZ led the investigations at the respective centres; JL acquired the primary funding; WX, CZha, SL, JW, ZY, YC, CZhe, XF and WC acquired and curated the data with JR responsible for data checks and preparing the data for statistical analysis; JR planned and performed the statistical analysis with support from SL and JW; JR created all figures and tables for this article with support from JW; JR wrote the original draft with support from SL and JW; all other authors revised the draft for critical content; JL and JR supervised the study. All authors have read and agreed with the submitted version of the manuscript. JL and JR act as guarantors for this work and accept full responsibility for the work and the conduct of the study, they had access to the data and controlled the decision to publish.

Funding: This research was funded by Jiangsu CF PharmTech (to JL); Department of Science and Technology of Sichuan Province (21ZDYF1918, to JR), the Fundamental Research Funds of Central Universities in China (20 827 041D4161, to JR), Xi'an Science and Technology Bureau (XA2020-HWYZ-0043, to JR). CF PharmTech provided technical and financial support for the conduct of the study. Department of Science and Technology of Sichuan Province, the Fundamental Research Funds of Central Universities in China and Xi'an Science and Technology Bureau provided financial support for the conduct of the study.

Disclaimer: The funders did not have any influence on the design, conduct, analysis, data interpretation and conclusions of his study.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work. JL reports a research grant from Jiangsu CF PharmTech. JR reports research grants from Xi’an Bureau of Technology, China; from the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, China and from Sichuan Bureau of Science and Technology, China during the conduct of the study. No other relationships or activities exist that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Anonymised patient-level data on which the analysis, results and conclusions reported in this paper are based are available as Dryad dataset. Reinhardt, Jan D. (2021), Telerehabilitation program for COVID-19 survivors (TERECO) - randomized controlled trial, Dryad, Dataset, https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.59zw3r27n

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

This study was registered at the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry on 11 April 2020 (ChiCTR2000031834). Ethical approval was first received from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University/Jiangsu Province Hospital (2020-SR-171, 9 April 2020) and then subsequently from the IRBs of Hubei Province Hospital of Integrated Chinese and Western Medicine (2020016, 14 April 2020), and Huangshi Hospital of Chinese Medicine (HSZYPJ-2020-026-01, 20 April 2020).

References

- 1. Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, et al. 6-Month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from Hospital: a cohort study. Lancet 2021;397:220–32. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Huang Y, Tan C, Wu J, et al. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on pulmonary function in early convalescence phase. Respir Res 2020;21:163. 10.1186/s12931-020-01429-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lopez-Leon S, Wegman-Ostrosky T, Perelman C, et al. More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. medRxiv 2021. 10.1101/2021.01.27.21250617. [Epub ahead of print: 30 Jan 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mo X, Jian W, Su Z, et al. Abnormal pulmonary function in COVID-19 patients at time of hospital discharge. Eur Respir J 2020;55:2001217. 10.1183/13993003.01217-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Belli S, Balbi B, Prince I, et al. Low physical functioning and impaired performance of activities of daily life in COVID-19 patients who survived hospitalisation. Eur Respir J 2020;56:2002096. 10.1183/13993003.02096-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Paneroni M, Simonelli C, Saleri M, et al. Muscle strength and physical performance in patients without previous disabilities recovering from COVID-19 pneumonia. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2021;100:105–9. 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhu S, Gao Q, Yang L, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of disability and anxiety in a retrospective cohort of 432 survivors of coronavirus Disease-2019 (Covid-19) from China. PLoS One 2020;15:e0243883. 10.1371/journal.pone.0243883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li Z, Zheng C, Duan C, et al. Rehabilitation needs of the first cohort of post-acute COVID-19 patients in Hubei, China. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2020;56:339–44. 10.23736/S1973-9087.20.06298-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McCarthy B, Casey D, Devane D, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;3:CD003793. 10.1002/14651858.CD003793.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lau HM-C, Ng GY-F, Jones AY-M, et al. A randomised controlled trial of the effectiveness of an exercise training program in patients recovering from severe acute respiratory syndrome. Aust J Physiother 2005;51:213–9. 10.1016/s0004-9514(05)70002-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Negrini F, de Sire A, Andrenelli E, et al. Rehabilitation and COVID-19: a rapid living systematic review 2020 by Cochrane rehabilitation field. update as of October 31st, 2020. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2021;57:166–70. 10.23736/S1973-9087.20.06723-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Grabowski DC, Joynt Maddox KE. Postacute care preparedness for COVID-19: thinking ahead. JAMA 2020;323:2007–8. 10.1001/jama.2020.4686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Suso-Martí L, La Touche R, Herranz-Gómez A, et al. Effectiveness of Telerehabilitation in physical therapist practice: an umbrella and mapping review with Meta–Meta-Analysis. Phys Ther 2021;101. 10.1093/ptj/pzab075. [Epub ahead of print: 04 May 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cox NS, Dal Corso S, Hansen H, et al. Telerehabilitation for chronic respiratory disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021;1:CD013040. 10.1002/14651858.CD013040.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fletcher CM, Elmes PC, Fairbairn AS, et al. The significance of respiratory symptoms and the diagnosis of chronic bronchitis in a working population. Br Med J 1959;2:257–66. 10.1136/bmj.2.5147.257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. American College of Sports Medicine . ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 9th ed. Philadelphia, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Karvonen MJ, Kentala E, Mustala O. The effects of training on heart rate; a longitudinal study. Ann Med Exp Biol Fenn 1957;35:307–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Holland AE, Spruit MA, Troosters T, et al. An official European respiratory Society/American thoracic Society technical standard: field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur Respir J 2014;44:1428–46. 10.1183/09031936.00150314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cho M. The effects of modified wall squat exercises on average adults' deep abdominal muscle thickness and lumbar stability. J Phys Ther Sci 2013;25:689–92. 10.1589/jpts.25.689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Culver BH, Graham BL, Coates AL, et al. Recommendations for a standardized pulmonary function report. An official American thoracic Society technical statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;196:1463–72. 10.1164/rccm.201710-1981ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Quanjer PH, Stanojevic S, Cole TJ, et al. Multi-Ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3–95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J 2012;40:1324–43. 10.1183/09031936.00080312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mu K, Liu S. National compilation of reference values of pulmonary function. Beijing, China: The Associated Press of Beijing Medical University and Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lins L, Carvalho FM. Sf-36 total score as a single measure of health-related quality of life: Scoping review. SAGE Open Med 2016;4:205031211667172. 10.1177/2050312116671725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996;34:220–33. 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Papiris SA, Daniil ZD, Malagari K, et al. Τhe medical Research Council dyspnea scale in the estimation of disease severity in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Med 2005;99:755–61. 10.1016/j.rmed.2004.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Singh SJ, Puhan MA, Andrianopoulos V, et al. An official systematic review of the European respiratory Society/American thoracic Society: measurement properties of field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur Respir J 2014;44:1447–78. 10.1183/09031936.00150414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Coffman CJ, Edelman D, Woolson RF. To condition or not condition? Analysing 'change' in longitudinal randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open 2016;6:e013096. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. J T, L B, T H, et al. Different ways to estimate treatment effects in randomised controlled trials. Contemp Clin Trials Commun 2018;10:80–5. 10.1016/j.conctc.2018.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bland JM, Altman DG. Regression towards the mean. BMJ 1994;308:1499. 10.1136/bmj.308.6942.1499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zou GY, Donner A. Extension of the modified poisson regression model to prospective studies with correlated binary data. Stat Methods Med Res 2013;22:661–70. 10.1177/0962280211427759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Goldstein H, Healy MJR. The graphical presentation of a collection of means. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc 1995;158:175–7. 10.2307/2983411 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med 2011;30:377–99. 10.1002/sim.4067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cro S, Morris TP, Kenward MG, et al. Sensitivity analysis for clinical trials with missing continuous outcome data using controlled multiple imputation: a practical guide. Stat Med 2020;39:2815–42. 10.1002/sim.8569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Holland AE, Malaguti C, Hoffman M, et al. Home-based or remote exercise testing in chronic respiratory disease, during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: a rapid review. Chron Respir Dis 2020;17:1479973120952418. 10.1177/1479973120952418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Torres-Castro R, Vasconcello-Castillo L, Alsina-Restoy X, et al. Respiratory function in patients post-infection by COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pulmonology 2020. 10.1016/j.pulmoe.2020.10.013. [Epub ahead of print: 25 Nov 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hu T, Liu Y, Zhao M, et al. A comparison of COVID-19, SARS and MERS. PeerJ 2020;8:e9725. 10.7717/peerj.9725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lu Y, Li P, Li N, et al. Effects of home-based breathing exercises in subjects with COPD. Respir Care 2020;65:377–87. 10.4187/respcare.07121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gold W, Koth L. Pulmonary Function testing. In: Broaddus V, Mason R, Ernst J, et al., eds. Murray and Nadel’s Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. Sixth ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2016: 407–35. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Festinger L, Carlsmith JM. Cognitive consequences of forced compliance. J Abnorm Psychol 1959;58:203–10. 10.1037/h0041593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kiekens C, Boldrini P, Andreoli A, et al. Rehabilitation and respiratory management in the acute and early post-acute phase. "Instant paper from the field" on rehabilitation answers to the COVID-19 emergency. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2020;56:323–6. 10.23736/S1973-9087.20.06305-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. National Health Commission of the PR China [国家卫生健康委员会] . Diagnostic criteria of the Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Diagnosis and Treatment Program (Trial Version 7) [in Chinese; 关于印发新型 状病毒肺炎诊疗方案 (试行第七版)的通知), 2020. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

thoraxjnl-2021-217382supp001.pdf (153.1KB, pdf)

thoraxjnl-2021-217382supp002.pdf (2.2MB, pdf)

thoraxjnl-2021-217382supp003.pdf (99.5KB, pdf)

thoraxjnl-2021-217382supp004.pdf (208.9KB, pdf)

thoraxjnl-2021-217382supp005.pdf (136.5KB, pdf)

thoraxjnl-2021-217382supp006.pdf (132.9KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Anonymised patient-level data on which the analysis, results and conclusions reported in this paper are based are available as Dryad dataset. Reinhardt, Jan D. (2021), Telerehabilitation program for COVID-19 survivors (TERECO) - randomized controlled trial, Dryad, Dataset, https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.59zw3r27n