Abstract

The growth plate is a cartilage tissue near the ends of children’s long bones and is responsible for bone growth. Injury to the growth plate can result in the formation of a ‘bony bar’ which can span the growth plate and result in bone growth abnormalities in children. Biomaterials such as chitosan microgels could be a potential treatment for growth plate injuries due to their chondrogenic properties, which can be enhanced through loading with biologics. They are commonly fabricated via an emulsion method, which involves solvent rinses that are cytotoxic. Here, we present a high throughput, non-cytotoxic, non-emulsion-based method to fabricate chitosan-genipin microgels. Chitosan was crosslinked with genipin to form a hydrogel network, and then pressed through a syringe filter using mesh with various pore sizes to produce a range of microgel particle sizes. The microgels were then loaded with chemokines and growth factors and their release was studied in vitro. To assess the applicability of the microgels to be used for growth plate cartilage regeneration, they were injected into a rat growth plate injury. They led to increased cartilage repair tissue and were fully degraded by 28 days in vivo. This work demonstrates that chitosan microgels can be fabricated without solvent rinses and demonstrates their potential for the treatment of growth plate injuries.

Keywords: Chitosan, microgels, cartilage regeneration, injectable biomaterials, growth plate

INTRODUCTION

Chitosan is a natural cationic polysaccharide derived from chitin that has been used extensively for tissue engineering1. In addition to its abundance in the natural world and its high degree of N-acetylation, it possesses favorable properties for biomedical use, such as nontoxicity, biocompatibility, and biodegradability2. When crosslinked with genipin, it forms a hydrogel network that can be used for drug or protein delivery3, and for biomimetic scaffolds for tissue repair4. Chitosan crosslinked with genipin can also form microgels, which are three-dimensional cross-linked polymeric particles with dimensions in the range from tens of nanometers to hundreds of micrometers.

Chitosan-genipin microgels have been used to repair a wide variety of tissues including bone, cartilage, liver, cardiac tissue, and intervertebral disks5–8. They are commonly fabricated by an oil in water emulsion method, in which an aqueous mixture of the chitosan polymer and genipin are homogenized in oil9. Alternatively, microfluidic devices using a similar approach have been used10. Depending on the homogenization settings, this creates micron-sized chitosan-genipin microspheres that must be subsequently washed with solvents to solubilize and remove the oil9. Commonly used solvents such as hexanes or ethanol are toxic to cells and must be removed prior to use. This introduces additional steps in the fabrication process and also reduces microgel yield. This study presents a novel approach for the fabrication of chitosan-genipin microgels in the absence of harsh organic solvents or emulsion-based techniques with precise control over microgel size and high-throughput fabrication, which may allow for a greater number of applications that could benefit from microgel technology.

One potential, untested application of chitosan microgels is for treating growth plate injuries. The growth plate is a thin, cartilage tissue found near the ends of children’s long bones and is responsible for long bone elongation. Injury to the growth plate can result in the formation of a ‘bony bar’ which if untreated can lead to skeletal growth deformities. Current treatments involve surgical resection of the bony bar followed by insertion of an inert material, such as silicone with the hopes of preventing bone growth abnormalities. Unfortunately these treatments frequently fail, the bony bar returns, and the pediatric patient must undergo corrective surgeries throughout their childhood11. New treatments that prevent bony bar formation and repair the growth plate cartilage could restore long bone growth, prevent growth abnormalities, and improve patient outcomes. Given that chitosan-based biomaterials have been shown to enhance chondrogenesis of cultured cells, and promote repair of articular cartilage defects, chitosan microgels could be an effective treatment for growth plate injuries4, 12–16.

The goal of this study was to develop an emulsion-free, noncytotoxic method to fabricate chitosan-genipin microgels that could then be applied in a rat model of growth plate injury to regenerate growth plate cartilage. We characterized microgel swelling, size, and degradation properties. In addition, we tested the loading and release of stromal cell derived factor-1α (SDF-1α, positively charged 7.9kDa protein), a stem cell attracting chemokine, and Transforming Growth Factor-β3 (TGF-β3, slightly positively charged 25kDa protein), a chondrogenic growth factor, from these microgels17, 18. SDF-1α and TGF- β3 have been widely investigated in cartilage tissue engineering due to their high efficacy in stem cell recruitment and chondrogenic differentiation, respectively. Release of these factors could enhance growth plate repair by increasing stem cell recruitment and inducing chondrogenesis19. Lastly, we tested the in vivo behavior of these microgels +/− SDF-1α and +/− TGF-β3 in a rat model of growth plate injury.

METHODS

Microgel Fabrication

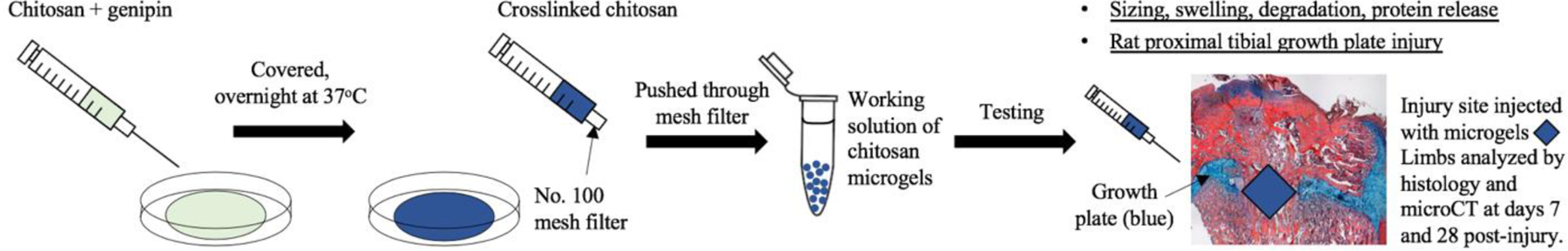

Chitosan microgels were fabricated via an emulsion-free and solvent-free method. An overview of the microgel fabrication process and subsequent testing is presented in Figure 1. Low molecular weight chitosan (75–80% deacetylation, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, 448869) was purified as previously described20. In brief, the chitosan was dissolved at 1 wt% in 1% glacial acetic acid, filtered to 0.22 µm, and dialyzed in cellulose bags with a 3500 Da MW cutoff for 1 week in distilled water. The chitosan was then lyophilized and frozen until further use. A 6 wt% chitosan solution was formed by mixing 2 mL of 1 M acetic acid and 120 mg of purified and lyophilized chitosan between two 10 mL syringes connected together with a luer-lock for about 2 min until the chitosan was dissolved. 100 µL of 100 mM genipin in absolute ethanol was placed in another 10 mL syringe and then connected with a leur-lock connector to the syringe containing the chitosan solution. The chitosan-genipin solution was mixed vigorously for 30 seconds then injected onto a 35mm petri dish, covered, and incubated at 37 ⁰C overnight.

Figure 1:

Schematic of study.

After crosslinking, the gel was broken into pieces with a spatula and deposited into a 10 mL syringe with a No. 100 wire mesh sieve (McMaster-Carr, Cleveland, OH, Cat. # 9317T86, 152 µm pore size). The syringe was then filled with excess diH2O and this mixture was strained forcefully through the filter to break up the gel. These microgels were then transferred into the same 10 mL syringe, and this process of pushing the microgel/diH2O mixture through the filter was repeated three times to ensure breakdown of the gel into microgel sized particles. To remove very small particles (<75 µm sized gels), the mixture was transferred to a conical tube and centrifuged at low speed (100 x g for 1 minute). The supernatant with the very small gel particles was removed and discarded. Then excess diH2O was added, the tube vortexed, and the process repeated until the supernatant became clear. A working solution of microgels was prepared by centrifuging the microgels, removing the water supernatant, and adding an equal volume of water to the microgels. This yielded a 1:1 microgel:water solution which was used for the subsequent experiments.

Microgel characterization

To measure the size of the chitosan microgels, 100 µL of the 1:1 microgel dilution was mixed with 1 mL of diH2O and imaged with a fluorescent microscope at an excitation wavelength (λex) of 560 nm and emission wavelength (λem) of 645 nm. Five representative images were taken, and microgel size was determined using image processing software with particle analysis capabilities (Analyze Particles, ImageJ; NIH) after automatic thresholding on images of non-aggregated and monodispersed particles (n = 69, circularity: 0–1). Briefly, a 100 μm scale bar was imaged as a basis, and automatically thresholded particles were sized according to their relation to the scale bar. The auto-fluorescent blue pigment of genipin-crosslinked chitosan microgels is believed to be due to oxygen radical-induced genipin crosslinking and dehydrogenation of intermediate compounds, which has previously been shown to be useful as a fluorescent probe while monitoring microgel interactions21.

To measure swelling of the particles in response to pH, 100 µL of the 1:1 microgel dilution was mixed with 1 mL of 20 mM HEPES (pH 6.8, 7.4, or 8.0) and allowed to equilibrate for 18 hours at 4 ⁰C. 100 µL was pipetted onto a glass slide and imaged with a fluorescent microscope. Five representative images were chosen for each pH and the distribution of Feret diameters for the particles was calculated using the normal distribution function in Microsoft Excel (Version 1908). The normal distribution curves and average Feret diameters were plotted using MATLAB (2019) version 9.7.0.1247435 (R2019b).

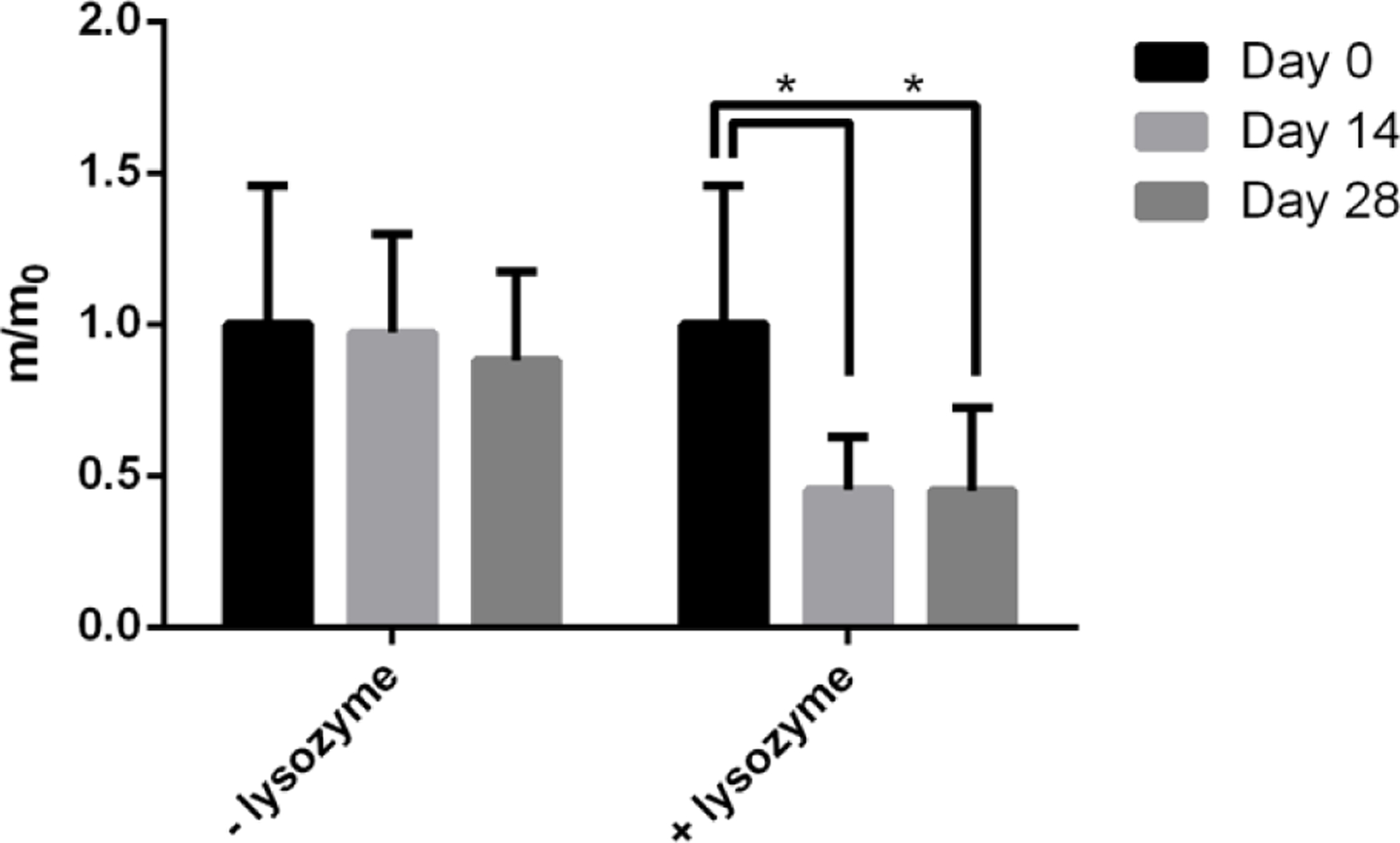

Lysozyme degradation

Lysozyme is commonly used to test the degradation of chitosan-based biomaterials. To test the degradation, 400 µL of the 1:1 microgel dilution was added to a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube in addition to 1 mL of 20 mM HEPES at pH=6.8 with or without lysozyme (0.5 mg/mL, n= 4). The tubes were mixed by inversion and incubated at 37 ⁰C with rotation at 20 RPM. At days 0, 14, and 28, the tubes were centrifuged (10,000 x g for 5 min) and the supernatant was removed. The tubes were frozen at −20 ⁰C and lyophilized overnight to yield a dried microgel pellet. The mass of the dried pellet was taken, and the degradation ratio was calculated by m/m0, where m is the average microgel dry mass at day 14 or 28, and m0 is the average microgel dry mass on day 0.

Protein loading and release

To determine whether these chitosan microgels could be loaded with and release proteins, release curves were performed. 1 ml of 20 mM HEPES pH 6.8 was added to 400 µl of the 1:1 microgel dilution, and then 200 ng of SDF-1α (Peprotech 300–28A) or TGF-β3 (Peprotech 100–36E) in 20 µl water was added (n=3). Samples were allowed to incubate for two days at 4°C with rotation to load the microgels with protein. Then samples were centrifuged at 2000 x g for 5 mins, 1 ml of the supernatant was collected (supernatant), and the sample was washed with 1 ml of 20 mM HEPES pH 7.4 to adjust the pH. The mass of protein loaded was determined by taking the total protein loaded (200 ng) and subtracting the protein in the supernatant, which was measured via ELISA according to manufacturer’s instructions (RnD Systems, Minneapolis, MN; DY350 for SDF-1α , and DY243 for TGF-β3). Samples were centrifuged again, supernatant was collected (wash), and 1 ml of 1X PBS pH 7.4 was added. The mass of protein in the wash was also determined by ELISA. Then the encapsulation efficiency of protein loading was calculated as:

Samples were incubated at 37°C, and at specified time points, the sample was centrifuged, and 1 ml of supernatant was collected and replaced with 1 ml PBS. At the time of collection, supernatant was frozen at −80°C until further use. The mass of protein in the supernatant at each time point was determined by ELISA according to manufacturer’s instructions. Protein release is reported as cumulative release.

Rat growth plate injury surgery

To assess the effects of chitosan microgel treatments on growth plate injury repair, a rat growth plate injury model was used as previously reported22. All animal procedures were approved by the University of Colorado Denver Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Briefly, a 2.0 mm drill-hole injury were created in the right proximal tibial growth plate of 6-week old male Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 3–4 animals per group)22. The injury site was flushed with saline and animals were left untreated, or injected with the chitosan microgels only, microgels + SDF-1α, or microgels + TGF-β3 (day 28 animals only). Following surgery, the wound was closed, animals were administered post-surgical analgesics, allowed to bear weight, and were observed to ambulate freely. Animals were euthanized by CO2 overdose at days 7 or 28 post-surgery, at which time the limbs were excised and processed for histology to assess repair tissue at the injury site.

MicroCT imaging and bony bar formation

MicroCT was used to determine bony bar formation within the growth plate injury site, as mineralized bone tissue can easily be measured within the radiolucent growth plate cartilage tissue. Limbs were harvested, and scanned by Micro-Computed Tomography (MicroCT) using a Siemens Inveon animal MicroCT scanner. Tibiae were scanned at an isotropic voxel size of 15 μm, and the image stacks were used to calculate bony bar formation within the growth plate injury site using ImageJ23. A standardized 2.5mm x 2.5mm region of interest (ROI) was drawn around the newly formed bony bar tissue within the growth plate injury site. Bony bar formation is reported as bone volume/total volume.

Alcian blue hematoxylin histology

To determine the effects of the chitosan microgels on physeal injury, visualize the type of repair tissue formed in response to the different treatments, and assess microgel degradation in vivo, histology was employed. After fixation in formalin for 2 days at room temperature, tibiae were decalcified in 14% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, which was changed 3 times per week for 2 weeks.24 Tibiae were dehydrated, paraffin embedded, and sectioned in the sagittal plane. Sections in the middle of the injury site were stained using ABH (a composite stain of Alcian Blue, Hematoxylin, Orange G, Phloxine B, and Eosin Y), which has been used extensively in growth plate research and stains cartilage blue, bone orange to red, and fibrous tissue pink., and the chitosan microgels dark red.20, 25–27 While ABH stain cannot specifically stain for the chitosan microgels, they seem to appear as a dark red fibrous tissue which is not observed in the untreated group that does not receive chitosan microgels. Based on this dark red staining, the degradation of the chitosan microgels at each time point could be evaluated.

Statistical analysis

To determine statistical significance, data was analyzed using a Student’s t-test and Tukey post-hoc analysis using GraphPad software version 6.01. Data is presented as the mean +/− SD.

RESULTS

Chitosan-genipin microgels were fabricated via an emulsion-free method

In this study, an emulsion-free crosslinking method was developed, which required no solvent rinses, and therefore used fewer steps than standard emulsion or homogenization methods. The fabrication process is summarized in Figure 1. Chitosan and genipin could be homogenously mixed using syringes, which resulted in a polymer network that was solidified in 12–16 hours at 37°C. The microgels used for the experiments throughout this study were made using a No. 100 mesh metal sieve, which produced irregularly shaped microgel particles ~ 124.5 µm average Feret diameter at pH 7.4 (Figure 2). We also demonstrated that smaller particles could be fabricated in large quantities using a No. 200 mesh sieve (76 µm pore size) (Figure 2). The microgels exhibited significant swelling and de-swelling behavior in response to pH. Microgels had the largest and smallest Feret diameter at pH 6.8 and 8.0, respectively, which is indicative of amine protonation at the lower pH (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

(a) Normal distribution graph of the Feret Diameter showing swelling behavior of microgels in response to pH changes. (b) Fluorescent images of microgels fabricated using No. 200 mesh (upper image. <75 µm sized microgels), and No. 100 mesh (lower image. ~75–150 µm sized microgels).

Chitosan-genipin microgels demonstrated lysozyme-dependent degradation

We next investigated degradation of the microgels in the presence of lysozyme, a natural protease that cleaves and degrades chitosan polymers. The chitosan microgels demonstrated significant degradation in the presence of lysozyme after 14 days in vitro (Figure 3). There was no further degradation of the microgels after day 14. Additionally, there was no microgel degradation without lysozyme.

Figure 3:

Microgel degradation in the presence of lysozyme in 20 mM HEPES pH 6.8 buffer at Day 0, Day 14 and Day 28. * p<0.05 compared to the Day 0 time point.

Microgels exhibited high efficiency of protein loading

To investigate the ability of chitosan microgels to be loaded with and release bioactive factors, release studies were performed. Two different growth factors were each loaded at an acidic pH 6.8, at which the microgels are partially swollen (Figure 2)9.

SDF-1α and TGF-β3 had a 95.9 +/− 0.2% and 96.1 +/− 0.4% encapsulation efficiency, respectively, as reported in Table 1, indicating that the majority of proteins were loaded and retained in the microgels. SDF-1α showed a delayed release beginning after day 7 and continuing until day 33 (Figure 4). TGF-β3 showed a quicker release which leveled off by day 9 (Figure 4). While ~200 ng of protein was loaded into the microgels, only ~2 ng of SDF-1α and ~4 ng of TGF-β3 was released, suggesting that the majority of protein remained within the microgels during these release studies in which no lysozyme was present and thus degradation of the chitosan microgels was minimal.

Table 1.

Encapsulation Efficiency of Growth Factors in Microgels.

| Growth Factor | Encapsulation Efficiency | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| SDF-1α | 95.9 % | 0.2 % |

| TGF-β3 | 96.1 % | 0.4 % |

Figure 4:

Release curves showing the cumulative protein release over time of SDF-1α (a) and TGF-β3 (b) from microgels.

Microgels degraded in vivo and showed increased cartilage repair tissue in a rat growth plate injury

We next tested the in vivo behavior of the microgels, and their influence on growth plate cartilage repair following injury. At days 7 and 28 post-injury, tibiae were harvested to assess repair tissue histologically using ABH, which stains cartilage blue, bone orange to red, and fibrous tissue pink. While the stain is not specific for chitosan microgels, they appear as a fibrous dark red tissue that is not present in the untreated group (Figure 5c,d, compared to b). At day 7, the untreated limbs showed fibrous tissue at the injury site, while chitosan microgels appeared to be present at the injury site of all treated animals (Figure 5b–d). MicroCT analysis showed significantly less bony bar formation at day 7 in the microgel only and microgel + SDF-1α treated groups than in the untreated group (Figure 6a).

Figure 5:

10x histological images showing growth plate repair tissue of intact (a, e), untreated (b, f), microgel treated (c, g), microgel + SDF-1α treated (d, h), and microgel + TGF-β3 (i) limbs. No day 7 animals were treated with microgel + TGF-β3. ABH stains the bone orange to red, fibrous tissue pink, and cartilage blue. The microgel appears as a dark red fibrous-like tissue. Scale bars = 500 µm.

Figure 6:

Graphs showing bony bar formation at 7 (a) and 28 (b) days post-injury within the growth plate injury site as determined by microCT. (c–k) are microCT images of the tibiae, showing the growth plate and bony bar formation in response to the different treatments at both time points. The growth plate is the thin, radiolucent tissue (c, g). * indicates statistical significance (p < 0.05) versus the untreated group within the day 7 time point. The yellow box in (d) indicates how the ROI was drawn to measure bone growth within the growth plate injury. N =3–4 animals per group.

By day 28, microCT analysis also showed no differences in bony bar formation among the different groups (Figure 6b), indicating that these treatments did not prevent bony bar formation at this time. However, histology showed that all treated animals had increased amounts of cartilage tissue (Figure 5, blue tissue) at the injury site compared to untreated animals, suggesting that the microgels elicited a chondrogenic response of the repair tissue. There were no noticeable differences in the amount of cartilage repair tissue among the different microgel treated groups, suggesting that the TGF-β3 as used here did not elicit a robust chondrogenic response. Further, the microgels, which seem to stain a dark red color, were absent from the injury site suggesting that they had fully degraded in this environment. These results indicate that these microgels degrade over time in vivo, and also induce a chondrogenic response of growth plate repair tissue in this model.

DISCUSSION

In children, injury to the growth plate cartilage that is found at the ends of all long bones can result in severe skeletal growth deformities. At the injury site where the cartilage is damaged, a bony bar can form and impede normal bone elongation in the bone, with potentially devastating impacts on the child. Current clinical treatments involve surgical resection of the bony bar followed by insertion of an inert material, such as silicone or fat tissue, with the hopes of preventing abnormalities in the growth of the bone. However, these treatments often are not successful and the bony bar returns, and then the child must undergo corrective surgeries throughout their childhood11. Novel treatments that are able to prevent bony bar formation and repair the growth plate cartilage would be powerful, as they could restore the long bone growth, prevent growth abnormalities, and improve patient outcomes. In this work we investigated the ability of chitosan microgels to act as an insertional material that may help delay the formation of a bony bar and that could provide sustained delivery of stem cell attractant molecules and growth factors to encourage the formation of cartilage tissue at the defect.

The fabrication method presented here resulted in injectable chitosan-genipin microgels made without the use of oils or solvents that are detrimental to cells. This required fewer steps in the workflow process and no rinses, resulting in a higher yield of microgels. While 6 wt.% chitosan was used in this study, lower wt.% chitosan and lower concentrations of genipin can also produce chitosan microgels (data not shown). Here, a No. 100 wire sieve (152 µm pore size) resulted in microgels with diameters less than 150 µm, and a No. 200 sieve (76 µm pore size) resulted in microgels with a diameter less than 75 µm. Other sized wire sieves could be used to make microgels of different size fractions, depending on desired size range.

We demonstrated that these chitosan microgels respond to changes in pH, and also degrade in the presence of lysozyme, which is similar to microgels fabricated using a standard emulsion method9. Our release studies showed that the growth factors SDF-1α and TGF-β3 are loaded with very high efficiency, which could reduce the amount of protein required for the encapsulation process. While these microgels had a high encapsulation efficiency, most of the protein remained entrapped in the microgels over the course of our release study. Given that these microgels showed no degradation without lysozyme, the use of lysozyme for the release study would likely have increased protein release via microgel degradation. In contrast, the microgels in the animal studies were completely degraded by day 28, and thus the loaded proteins would have become available as the microgels degraded over time. We expect that proteins with a similar size and charge as the proteins used here would load and release similarly to what we observed.

Our in vivo study showed that microgels can be injected at the site of injury in a rat growth plate injury model. The microgels were still present 7 days post-injection and inhibited new bone tissue formation, demonstrating that they prevent bony bar formation at this time point. This is promising as reductions in bony bar formation can result in positive clinical outcomes in terms of restored bone growth11. While there was no difference in bony bar formation between the untreated and treated animals at day 28, there was increased cartilage repair tissue in microgel-treated animals suggesting that they induce chondrogenesis in the injured growth plate. The lack of a robust chondrogenic response in the microgel + TGF-β3 treated group could be due to an insufficient dose or delivery rate, which will be addressed in future studies. Future studies will also address in vivo protein release rate, and methods for assessing stem cell migration.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we have developed a noncytotoxic, nonemulsion-based method to fabricate chitosan microgels that have similar properties to microgels made by standard emulsion and homogenization processes. We have demonstrated the ability of these microgels to prevent early bony bar formation in growth plate cartilage defects in vivo. Given our results, these chitosan microgels should be further developed to enhance growth plate cartilage restoration following injury, as they could have positive implications for children suffering from these injuries. This method avoids the use of solvent rinses, uses fewer processing steps, and results in increased microgel yield. This process could likely be extended to the fabrication of microgels that share a similar crosslinking method to chitosan and genipin21.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R03AR068087 and R21AR071585 and by the Boettcher Foundation (#11219) to MDK. CBE was supported by NIH/NCATS Colorado CTSA Grant Number TL1 TR001081.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pella MCG, Lima-Tenorio MK, Tenorio-Neto ET, et al. Chitosan-based hydrogels: From preparation to biomedical applications. Carbohydr Polym 2018; 196: 233–245. 2018/06/13. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Felt O, Buri P and Gurny R. Chitosan: a unique polysaccharide for drug delivery. Drug development and industrial pharmacy 1998; 24: 979–993. 1999/01/07. DOI: 10.3109/03639049809089942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karnchanajindanun J, Srisa-ard M and Baimark Y. Genipin-cross-linked chitosan microspheres prepared by a water-in-oil emulsion solvent diffusion method for protein delivery. Carbohydrate Polymers 2011; 85: 674–680. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2011.03.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan L-P, Wang Y-J, Ren L, et al. Genipin-cross-linked collagen/chitosan biomimetic scaffolds for articular cartilage tissue engineering applications. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A 2010; 95A: 465–475. DOI: 10.1002/jbm.a.32869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muzzarelli RA, El Mehtedi M, Bottegoni C, et al. Genipin-Crosslinked Chitosan Gels and Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering and Regeneration of Cartilage and Bone. Mar Drugs 2015; 13: 7314–7338. 2015/12/23. DOI: 10.3390/md13127068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, Wang QS, Yan K, et al. Preparation, characterization, and evaluation of genipin crosslinked chitosan/gelatin three-dimensional scaffolds for liver tissue engineering applications. Journal of biomedical materials research Part A 2016; 104: 1863–1870. 2016/03/31. DOI: 10.1002/jbm.a.35717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fang Y, Zhang T, Song Y, et al. Assessment of various crosslinking agents on collagen/chitosan scaffolds for myocardial tissue engineering. Biomedical materials (Bristol, England) 2019. 2019/09/19. DOI: 10.1088/1748-605X/ab452d. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Mwale F, Iordanova M, Demers CN, et al. Biological evaluation of chitosan salts cross-linked to genipin as a cell scaffold for disk tissue engineering. Tissue engineering 2005; 11: 130–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riederer MS, Requist BD, Payne KA, et al. Injectable and microporous scaffold of densely-packed, growth factor-encapsulating chitosan microgels. Carbohydrate Polymers 2016; 152: 792–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zamora-Mora V, Velasco D, Hernández R, et al. Chitosan/agarose hydrogels: Cooperative properties and microfluidic preparation. Carbohydrate polymers 2014; 111: 348–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaw N, Erickson C, Bryant SJ, et al. Regenerative Medicine Approaches for the Treatment of Pediatric Physeal Injuries. Tissue Engineering Part B: Reviews 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Xia W, Liu W, Cui L, et al. Tissue engineering of cartilage with the use of chitosan-gelatin complex scaffolds. Journal of biomedical materials research Part B, Applied biomaterials 2004; 71: 373–380. 2004/09/24. DOI: 10.1002/jbm.b.30087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Comblain F, Rocasalbas G, Gauthier S, et al. Chitosan: A promising polymer for cartilage repair and viscosupplementation. Biomed Mater Eng 2017; 28: S209–s215. 2017/04/05. DOI: 10.3233/bme-171643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohan N, Mohanan PV, Sabareeswaran A, et al. Chitosan-hyaluronic acid hydrogel for cartilage repair. Int J Biol Macromol 2017; 104: 1936–1945. 2017/04/01. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.03.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silva SS, Motta A, Rodrigues MT, et al. Novel genipin-cross-linked chitosan/silk fibroin sponges for cartilage engineering strategies. Biomacromolecules 2008; 9: 2764–2774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Islam MM, Shahruzzaman M, Biswas S, et al. Chitosan based bioactive materials in tissue engineering applications-A review. Bioactive materials 2020; 5: 164–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dealwis C, Fernandez EJ, Thompson DA, et al. Crystal structure of chemically synthesized [N33A] stromal cell-derived factor 1α, a potent ligand for the HIV-1 “fusin” coreceptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1998; 95: 6941–6946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim SK, Barron L, Hinck CS, et al. An engineered transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) monomer that functions as a dominant negative to block TGF-β signaling. The Journal of biological chemistry 2017; 292: 7173–7188. 2017/02/24. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M116.768754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oh JK, Drumright R, Siegwart DJ, et al. The development of microgels/nanogels for drug delivery applications. Progress in Polymer Science 2008; 33: 448–477. DOI: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2008.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erickson CB, Newsom JP, Fletcher NA, et al. In vivo degradation rate of alginate-chitosan hydrogels influences tissue repair following physeal injury. Journal of biomedical materials research Part B, Applied biomaterials 2020. 2020/02/09. DOI: 10.1002/jbm.b.34580. [DOI]

- 21.Butler MF, Ng YF and Pudney PD. Mechanism and kinetics of the crosslinking reaction between biopolymers containing primary amine groups and genipin. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry 2003; 41: 3941–3953. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erickson CB, Shaw N, Hadley-Miller N, et al. A Rat Tibial Growth Plate Injury Model to Characterize Repair Mechanisms and Evaluate Growth Plate Regeneration Strategies. Journal of visualized experiments: JoVE 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Doube M, Klosowski MM, Arganda-Carreras I, et al. BoneJ: Free and extensible bone image analysis in ImageJ. Bone 2010; 47: 1076–1079. DOI: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chung R, Foster BK and Xian CJ. The potential role of VEGF-induced vascularisation in the bony repair of injured growth plate cartilage. The Journal of endocrinology 2014; 221: 63–75. DOI: 10.1530/JOE-13-0539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Su YW, Chung R, Ruan CS, et al. Neurotrophin-3 Induces BMP-2 and VEGF Activities and Promotes the Bony Repair of Injured Growth Plate Cartilage and Bone in Rats. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research 2016. 2016/01/15. DOI: 10.1002/jbmr.2786. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Xian CJ, Zhou FH, McCarty RC, et al. Intramembranous ossification mechanism for bone bridge formation at the growth plate cartilage injury site. Journal of orthopaedic research : official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society 2004; 22: 417–426. 2004/03/12. DOI: 10.1016/j.orthres.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erickson CB, Newsom JP, Fletcher NA, et al. Anti-VEGF antibody delivered locally reduces bony bar formation following physeal injury in rats. Journal of orthopaedic research : official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society 2020. 2020/11/13. DOI: 10.1002/jor.24907. [DOI] [PubMed]