Abstract

Human coronaviruses (HCoVs) attracted attention in 2002 with the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak, caused by the SARS-CoV virus (mortality rate 9.6%), and gained further notoriety in 2012 with the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) (mortality rate 34.3%). Currently, the world is experiencing an unprecedented crisis due to the COVID-19 global pandemic, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus in 2019. The virus can pass to the faeces of some patients, as was the case of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV viruses. This suggests that apart from the airborne (droplets and aerosols) and person-to-person (including fomites) transmission, the faecal–oral route of transmission could also be possible for HCoVs. In this eventuality, natural water bodies could act as a virus reservoir of infection. Here, the temporospatial migration and attenuation of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in municipal wastewater, the receiving environment, and drinking water is evaluated, using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), in the South African setting. SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA was identified in raw wastewater influent but was below the detection limit in the latter treatment stages. This suggests that the virus decays from as early as primary treatment and this could be attributed to wastewater's hydraulic retention time (2–4 h), composition, and more importantly temperature (>25 °C). Therefore, the probability of SARS-CoV-2 virus transportation in water catchments, in the eventuality that the virus remains infective in wastewater, appears to be low in the South African setting. Finally, catchment-wide monitoring offers a snapshot of the status of the catchment in relation to contagious viruses and can play a pivotal role in informing the custodians and downstream water users of potential risks embedded in water bodies.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Municipal wastewater, Water quality monitoring, Real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR), Attenuation, SARS-CoV-2 migration

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Coronaviridae, commonly known as Coronaviruses (CoVs), is a family that comprise of large (the largest known) positive-strand RNA viruses (Payne, 2017). CoVs can be classed into four different genera, i.e., the alpha-, beta-, delta-, and gamma-coronavirus (Paules et al., 2020). Coronaviridae, along with Arteriviridae, Roniviridae, and Mesoniviridae families belong to Nidovirales order, with all exhibiting a characteristic replication strategy (Maclachlan and Dubovi, 2016). As is the case with most viruses, CoVs are enveloped viruses, i.e., viral envelopes act as outer layers between host cells. Members of the CoVs subfamily commonly affect mammals, with over 60 CoVs affecting bats, which serve as a large and mobile CoV reservoir (Payne, 2017). However, the genera that are known to infect humans, i.e., human coronaviruses (HCoVs), are only the alpha-CoVs (alphacoronaviruses) and beta-CoVs (betacoronaviruses) (Paules et al., 2020), while the gamma-CoVs (gammacoronaviruses) and delta-CoVs (deltacoronavirus), typically, but not exclusively, infect birds (Nakagawa et al., 2016).

Until the early 2000s, HCoVs were considered only minor pathogens (Payne, 2017), with only two groups, i.e., the HCoV-229E and HCoV-OC43, known to human (Trombetta et al., 2016). This perception changed rapidly in 2002 with the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak, which was caused by a previously unknown coronavirus, i.e., the SARS-CoV, that had a 9.6% mortality rate (Toyoshima et al., 2020). Specifically, 8096 probable cases were documented, resulting to 774 deaths across 30 countries (Trombetta et al., 2016). SARS outbreak increased awareness about HCoVs, which gained further notoriety with the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) outbreak in 2012 -probably of camel origin- (Tulchinsky and Varavikova, 2014), with 34.3% mortality rate (Toyoshima et al., 2020).

Currently, the global analysis of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2 or novel coronavirus), which is the virus responsible for the coronavirus disease that was documented in 2019 (COVID-19), suggest that the virus has infected over 188 million people and claimed 4 million lives as of 15 July 2021 (WHO, 2021). In South Africa, the first 3 COVID-19 cases were detected on the 2nd March 2020 and until the 15 of July 2021 more than 2 million people have been infected and 65,000 lives have been lost (WHO, 2021). It should be noted that South Africa has gone through three successive COVID-19 waves, with each one posing devastating effects (WHO, 2021). SARS-CoV-2 is highly contagious and spreads via droplets (from respiration), direct contact, and fomites (WHO, 2020), while it is genetically similar to the SARS-CoV (~79%) and MERS-CoV (~50%) viruses (Lu et al., 2020). Furthermore, the SARS-CoV RNA was detected in the digestive tract, as well as in human waste (faeces) of some infected patients, and subsequently in sewage through excretion, which raised the possibility that the virus could potentially spread via the faecal–oral route (Mattison et al., 2009). As such, SARS was classified as an emerging water-related diseases, since it could spread through aerosols in specific sanitary domestic or hospital situations (Bos, 2005). Alarmingly, the SARS-CoV RNA could survive for up to two weeks in untreated sewage at 4 °C, but typically for around 2 days at warmer temperatures (20 °C) (Wang et al., 2005a; Wang et al., 2005b). However, conventional water treatment methods, such as chlorination, are deemed sufficient for enveloped virus inactivation, including the SARS-CoV RNA (Wang et al., 2005a).

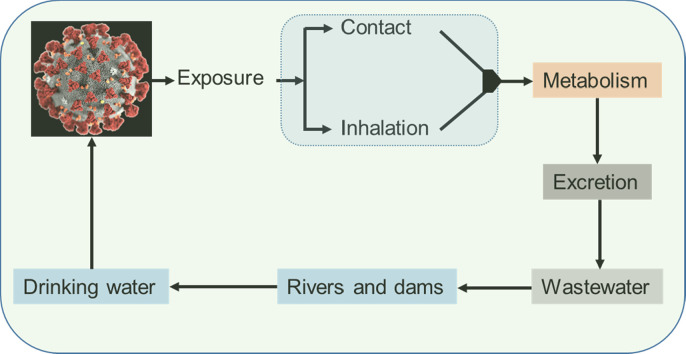

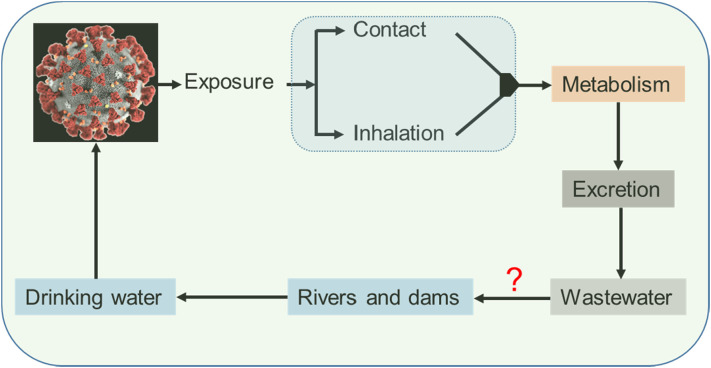

Regarding the SARS-CoV-2, it has been identified that the gastrointestinal shedding (viral RNA in faeces) last longer than the respiratory shedding (Xu et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020). The virus can persist even under the digestive tract's acidic conditions (Chin et al., 2020) and therefore viral RNA can pass from human excretions to wastewater (Medema et al., 2020; Ahmed et al., 2020; Randazzo et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020) and possibly to the environment (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in different spheres of the environment (modified from (Zhang et al., 2021)).

Therefore, environmental surveillance and early warning systems could play an important role in the fight against the spread of COVID-19, as is the case for a wide range of viruses (e.g., norovirus, hepatitis A, and poliovirus) (Hellmér et al., 2014; Asghar et al., 2014). Furthermore, as is the case with other pathogens (Kraay et al., 2018), natural water bodies can acts as environmental reservoir for SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

Finally, the World Health Organisation (WHO) has highlighted that some African countries are not able to test for the SARS-CoV-2 because they may lack infrastructure, equipment, human capital, and more importantly the required reagents (WHO, 2020). As a contingency and risk-based approach, wastewater surveillance provides a more practical option to identify hotspot areas (it can be less biased than case-reporting systems) and used to complement medical reports (Tegally et al., 2020). Here, a systematic assessment for a wide range of different water matrices in terms of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA is performed for the first time under the South African setting. Specifically, raw and treated (from different stages) municipal wastewater, along with surface water (river, canal, and dam) and drinking water samples were collected and assessed using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Insight is provided on both the existent of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in different water matrices and on the importance of catchment-wide environmental monitoring and assessment surveys. Catchment-wide assessments can provide insight on the decay mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in water and wastewater and could also help authorities into making evidence-based and informed decisions on lockdown relaxation strategies in South Africa and further afield.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sampling localities

In the context of this catchment-wide work, drinking water, surface water, i.e., river, canal, and dam water, and raw and treated municipal wastewater samples were tested for SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA. To this end, several field surveys were carried out between the end of October and middle of November 2020 (Table 1 ). In municipal wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), samples from the raw influent wastewater, the primary sedimentation tank (PST), the biological nutrient removal (BNR) step, as well as samples from the final treated effluent were collected and tested. Two municipal WWTPs, namely the Z and the B (for confidentiality reasons the full names are not provided), were examined. Both treatment facilities are equipped with tertiary treatment, i.e., chlorination with gas chlorine or high test hypochlorite (HTH), although chemicals procurement might be challenging in low and middle income countries (LMIC) due to numerous reasons. The design daily capacity of the Z and B WWTPs are ≈40,000 m3 and ≈65,000 m3 respectively.

Table 1.

Sampling localities along with the type of each sample and the corresponding sampling date.

| Sampling name | Region | Latitude(S) | Longitude (E) | Sampling dates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) | ||||

| WWTP Z | Tshwane | 25°37′23.52″S | 28°19′59.71″E | 27/10/2020 03/11/2020 |

| WWTP B | Tshwane | 25°41′23.66″S | 28°21′51.76″E | 27/10/2020 03/11/2020 |

| Water treatment plant (WTP) | ||||

| Vaalkop | North West | 25°18′28.26″S | 27°29′28.26″E | 27/10/2020 03/11/2020 10/11/2020 17/11/2020 |

| Klipdrift | Tshwane | 25°22′59.36″S | 28°18′34.99″E | 27/10/2020 03/11/2020 10/11/2020 17/11/2020 |

| Wallmansthal | Tshwane | 25°34′34.22″S | 28°19′40.66″E | 26/10/2020 03/11/2020 09/11/2020 16/11/2020 |

| Cullinan | Tshwane | 25°40′30.81″S | 28°31′45.78″E | 26/10/2020 03/11/2020 09/11/2020 16/11/2020 |

| Untreated surface water (surface water) | ||||

| Roodeplaat dam | Tshwane | 25°47′38.06″S | 28°46′58.21″E | 26/10/2020 03/11/2020 09/11/2020 16/11/2020 |

| Canal | Tshwane | 25°34′34.22″S | 28°19′40.66″E | 26/10/2020 03/11/2020 09/11/2020 16/11/2020 |

| River | Tshwane | 25°22′59.36″S | 28°18′34.99″E | 26/10/2020 03/11/2020 09/11/2020 16/11/2020 |

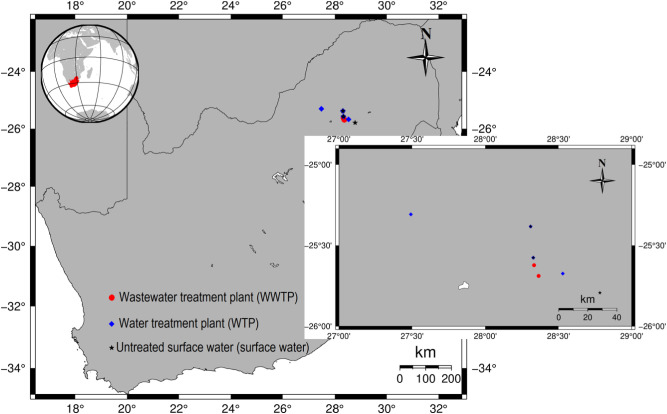

Surface water samples were collected from the catchment areas of Vaalkop, Cullinan, Klipdrift and Wallmansthal water treatment plants (WTPs), along with drinking water (tap water) from these facilities (Fig. 2 ). The main physicochemical and microbial parameters of the collected water and wastewater samples, including ammonia content, chemical oxygen demand (COD), free chlorine, E coli, electrical conductivity (EC), faecal coliforms, nitrate, orthophosphate, pH, somatic coliphages, temperature, free chlorine, and total suspended solids (TSS), were also measured. These parameters provide insight on the water chemistry and the decay mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in water and wastewater. The locations of the collected samples are listed in Table 1 and shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The sampling locations within the area of study.

2.2. Sample collection

For both water and wastewater matrices, samples were collected by means of sterilised SCHOTT DURAN® laboratory glass bottles (1 L volume). Before sampling, the bottles were exposed to 1.8% (mass per volume - m/v) sodium thiosulfate pentahydrate (Na2S2O3·5H2O) (diluted in ultrapure water) and then sterilised in an autoclavable. In the field, water and wastewater samples were collected using the grab sampling technique. Wastewater samples were collected from the influent and at the end of the PST, BNR (aeration), and tertiary (chlorination) treatment step. For drinking water samples, the tap was first disinfected with 99.9% ethanol and flamed before sampling. A total of 61 samples were acquired from these locations during several field surveys and for the timespan ranging from the 26/10/2020 to 17/11/2020 (Table 1).

2.3. Aqueous samples characterisation

The physicochemical characteristics of water and wastewater plays an indispensable role in HCoVs decay, since it has been suggested that the inactivation HCoVs has a close relationship with temperature, total organic matter, and hostile bacteria presence in water (Gundy et al., 2008). For this reason, the main parameters of the collected aqueous samples were measured following standard methods at Magalies Water Services Laboratory (ISO/IEC 17025:2017 accredited) in Brits, North West, South Africa. Specifically, the pH, temperature, and EC were measured using an HQ40d Portable Meter (Hach Company - US). The DR6000 spectrophotometer (Hach Company - US) was used to measure COD, orthophosphate, nitrate, and ammonia content in sewage water (highly concentrated samples) and the Gallery™ Plus Discrete Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. - US) was used to measure the same parameters in surface and potable water (less concentrated samples). Finally, free chlorine was measured using the DR900 colorimeter (Hach Company - US).

2.4. SARS-CoV-2 RNA analysis

2.4.1. Determination of the actual RNA concentration

The collected samples were first incubated in a water bath (60 °C for 15 min). Then, 35 mL of each sample was decanted into a centrifuge tube. This was performed in triplicates, so that sufficient RNA material would be collected from each sample. The tubes were centrifuged (4700 rpm and 4 °C) for 30 min. Then, 3.5 g of PolyEthylene Glycol 8000 (PEG 8000) and 0.788 g of sodium chloride (NaCl) were added. The centrifuge tubes, containing the PEG 8000 and NaCl, were then mixed and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 120 min. After centrifugation, the supernatant was carefully discarded without disturbing the pellet. The pellet was then re-suspended with 500 μL nuclease-free water.

2.4.2. RNA extraction

Genomic RNA was extracted from the collected samples or isolates using the NucleoMag DNA/RNA water kit (Macherey-Nagel, Germany). Specifically, 200 μL of each sample was dispensed in a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube along with 180 μL of lysis buffer. Then, 20 μL of Proteinase K and 10 μL of internal control template for extraction (RNA, high concentration) were added to the tube that contained the sample and lysis buffer. The mixture was then vortexed and incubated for 15 min at 56 °C. After incubation, 20 μL (magnetic beads) and 600 μL (binding buffer) were added to the lysed sample, vortexed, and left for 5–10 min at room temperature. The magnetic beads were separated from the sample by placing the tube in the magnetic separator and discarding the supernatant. The tube containing the beads was then removed from the magnetic separator and 600 μL of “wash buffer 1” was added, and left for 1 min at room temperature. The supernatant was discarded and the tube was removed from the magnetic separator, whereafter 600 μL of “wash buffer 2” was added and left for 1 min at room temperature. Similarly, the supernatant was discarded and the tube containing the beads was removed from the magnetic separator, however, in this case washing with 80% ethanol for 1 min at room temperature followed. The supernatant was discarded and 100 μL of elution buffer was added. The extracted genomic RNA was then measured using the real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) technique. The extracted RNA was assessed using a Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. - US).

2.4.3. PCR amplification for SAR- CoV-2 RNA detection

As mentioned above, the RT-qPCR technique was employed to detect the SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA, making use of the 2019-nCoV genesig® Advanced Kit (Primerdesign Ltd. - US) that targets the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) gene. Specifically, 20 μL of PCR reaction volume, consisting of: i) 10 μL of oasig OneStep master mix, ii) 1 μL 2019-nCoV primer, iii) 5 μL of template DNA (DNA <100 ng), and iv) 4 μL of nuclease free water, was prepared. The RT-qPCR assays were performed using Agilent's RT-qPCR instrument Mx3005P (Agilent Technologies, Inc. - US). The temperature program for the detection of the RNA of the SARS-CoV-2 virus (50 cycles) was as follows: reverse transcription at 55 °C for 10 min, followed by enzyme activation for 120 s at 95 °C, denaturation for 10 s at 95 °C and at 60 °C for 60 s for data collection. Results are reported in cycle threshold (Ct) values, i.e., the total number of cycles that are required for the fluorescent signal to cross the threshold (background level). The lowest positive control of this kit comes out at 36–38 Ct.

3. Results and discussion

First, the results for the physicochemical characteristics of the collected samples, i.e., wastewater, surface water (river, canal, dam), and tap water, are shown. Then, the RT-qPCR results, which can reveal the presence of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in the examined aqueous matrices, are presented. Finally, insight and recommendations on SARS-CoV-2 in water matrices in the South African setting are given. As a preamble, the amplification of SARS-CoV-2 RNA genes was successful in the collected wastewater samples. As mentioned above, the samples were collected at different field surveys carried out between 26/10/2020 to 17/11/2020, with the 03/11/2020 field survey being the most extensive one, since samples from all the examined water matrices were collected in this day (Table S1, Appendix). The examined timespan, i.e., end of October to mid November 2020, corresponds to the time when the South African COVID-19 variant (501Y.V2 variant, B.1.351 lineage) was first identified (Tegally et al., 2020). This was also the start of the second COVID-19 wave that hit South Africa. Therefore, the presented measurements document the onset of this devastating wave, from which South Africa is still reeling.

3.1. SARS-CoV-2 measurements in wastewater

Two WWTPs were examined in terms of SARS CoV-2 viral RNA, namely the Z and B facilities. The physicochemical properties were also examined, and results are shown, as mean values, in Table 2 (Table S1 in the Appendix list the result for the 27/10/2020 and the 03/11/2020 field survey separately).

Table 2.

The physicochemical and microbial properties, including the RT-qPCR results for SARS CoV-2 viral RNA copies, of wastewater sampled from different treatment steps at the Z and B WWTPs in South Africa.

| Parameters | Units | Influent |

PST |

BNR |

Effluent |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z | B | Z | B | Z | B | Z | B | ||

| Ammonia | mg/L | 41.9 ± 5.4 | 46.1 ± 11.9 | 45.5 ± 0 | 32.8 ± 7.2 | 5.9 ± 4.4 | 33.8 ± 1.6 | 2.0 ± 0 | 33.0 ± 1.1 |

| COD | mg/L | 714.5 ± 460.3 | 814.5 ± 483 | 331 ± 0 | 307 ± 248.9 | 4898.5 ± 6889.3 | 207 ± 224.9 | 27 ± 22.62 | 227.5 ± 255.3 |

| Free chlorine | mg/L | 0.01 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 |

| E. coli | count/100 mL | 705,000 ± 21,213.2 | 4,310,000 ± 282,842 | 38,500 ± 3535.5 | 4,590,000 ± 5,246,732 | 60,000 ± 41,012.2 | 3,820,000 ± 4,355,778 | 41,500 ± 233,334.52 | 7,300,000 ± 848,528.1 |

| EC* | mS/m | 102.5 ± 19.1 | 119.0 ± 37.7 | 94.0 ± 0 | 103.2 ± 22.3 | 70.7 ± 12.6 | 87.0 ± 4.0 | 78.9 ± 21.4 | 86.4 ± 5.2 |

| Faecal coliforms | count/100 mL | 860,000 ± 113,137.1 | 990,000 ± 28,284 | 48,000 ± 0 | 970,000 ± 14,142.1 | 35,500 ± 707.1 | 910,000 ± 0 | 28,500 ± 2121.3 | 890,000 ± 14,142.1 |

| Nitrate | mg/L N | 0.80 ± 0.1 | 0.75 ± 0.1 | 0.67 ± 0 | 0.49 ± 0.1 | 0.61 ± 0.2 | 0.41 ± 0 | 4.37 ± 3 | 0.44 ± 0.1 |

| Orthophosphate | mg/L P | 11.95 ± 1.1 | 14.6 ± 3.3 | 10.6 ± 0 | 6.08 ± 5.3 | 73.2 ± 74.7 | 1.6 ± 0 | 1.6 ± 0 | 1.6 ± 0 |

| pH* | pH | 7.05 ± 0.1 | 7.03 ± 0 | 7.08 ± 0 | 7.12 ± 0.3 | 6.64 ± 0.1 | 7.36 ± 0.1 | 7.18 ± 0.2 | 7.30 ± 0.1 |

| Somatic coliphages | count/10 mL | 49,500 ± 2121.3 | 22,500 ± 2121 | 23,060 ± 0 | 19,140 ± 848.5 | 0.0 ± 0 | 18,170 ± 1965.8 | 0.0 ± 0 | 15,325 ± 1591 |

| Temperature | °C | 25.75 ± 1.1 | 25.75 ± 1.1 | 26.6 ± 0 | 25.7 ± 1 | 25.75 ± 1.1 | 25.75 ± 1.1 | 25.75 ± 1.1 | 25.7 ± 1 |

| SARS Cov-2 | Ct | 39.5 ± 2.1 | 39.0 ± 5.7 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 |

Note: EC and pH were measured at 25 °C, and TDS at 105 °C. PST is the primary sedimentation tank and BNR is the biological nutrient removal treatment step. Zero values denote that the parameter is below the limit of detection. Finally, Z and B are the two wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) under study.

As was expected, water samples from different treatment steps have different chemical compositions. More importantly, the amplification of SARS-CoV-2 genes was successful in the collected WWTPs samples. Specifically, SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in the influent (raw wastewater) of both treatment facilities, however it was not identified in any of the other treatment steps, i.e., PST, BNR, and treated effluent (outflow). The absence of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in the aforementioned treatment steps is in agreement with what has been reported in literature (Amoah et al., 2020). This could be attributed to PST's high hydraulic retention time (2–4 h), wastewater's chemical composition, and more importantly wastewater's temperature (Table 2). It should be noted that the two main mechanisms that govern the attenuation/decay of HCoVs in wastewater are viral adsorption and inactivation (Amoah et al., 2020).

Even though both WWTPs, and particularly the B, exhibited a subpar performance in terms of contaminants removal, the SARS-CoV-2 RNA was attenuated/decayed from the early start of the treatment process (PST). Poor performance is typical in WWTPs operating in South Africa and across the developing world. This creates problems in the receiving environment, affects downstream human activities such as agriculture and recreation, while microbiological contamination affects human health and living organisms. Overall, results suggest that even with some basic wastewater treatment the SARS-CoV-2 RNA can be attenuated/decayed, while compared to other microbiological contaminants, such as E. coli, it appears that SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA is significantly less persistent. Nonetheless, it is possible that viral RNA copies were still present in the effluent from these treatment steps, but at concentrations below the RT-qPCR detection limit (Langone et al., 2021). Finally, the aqueous matrices under study could also potentially affect the PCR inhibitors.

As can be seen in Table 2, SARS-CoV-2 RNA was identified in both WWTPs and during the two different field surveys (Table S1 in the appendix). The existence of genetic material in raw sewage implies that attention should be paid in limiting potential airflows within WWTPs that could lead to the aerosolisation of the virus. In general, wastewater plumbing systems are considered a harbinger of pathogenic microorganisms and potentially of the SARS-CoV-2 virus (Gormley et al., 2020). Leaking pipelines and transportation networks could also act as SARS-CoV-2 transmission pathway (Amoah et al., 2020). Furthermore, focus should be placed on (onsite) sanitation facilities, such as pit latrines which are widespread in South Africa and across the developing world (Masindi and Foteinis, 2021). Similar to what was reported for the SARS-CoV airborne transmission route, i.e., through virus laden droplets from building's wastewater plumbing systems (Gormley et al., 2020), onsite sanitation systems could also enable this transmission route, in the eventuality that the virus remains infective.

Groundwater contaminated from onsite sanitation systems could also act as an environmental reservoir for viruses (Masindi and Foteinis, 2021). Nonetheless, no SARS-CoV-2 transmission has been reported from sewage or contaminated water until now. However, this mode of transmission could be possible, particularly when possible future SARS-CoV-2 mutations are considered (Giacobbo et al., 2021). Finally, in both WWTPs the threshold cycle (Ct) values were higher in the second field survey (03/11/2020) than in the first (27/10/2020) (note that lower Ct values indicates higher concentrations of viral genetic material). This suggest that the COVID-19 infection rate was relatively stable at that time, which was expected since the measurements recorded the onset of the second wave and not its peak. Furthermore, results also suggest that the South African variant, which had increased transmissibility compared to previously reported lineages (Tegally et al., 2020), was not yet the dominant strain in these areas. Therefore, wastewater surveillance can provide a snapshot of the scale of infection and also used as a wastewater-based epidemiology method for COVID-19 and for future epidemics (Barcelo, 2020).

3.2. SARS-CoV-2 measurements in surface and drinking water

As mentioned above, surface water samples from the catchment areas that feed four (4) WTPs, i.e., the Vaalkop, Klipdrift, Wallmansthal, and Cullinan, were collected and assessed. Apart from surface water, the treated water (tap water) was also assessed. Samples were collected in different field surveys carried out between 26/10/2020 to 17/11/2020 (Table 1). Results are presented as mean values in Table 3 (the reader can refer to Table S1 in the Appendix for the result of each field survey).

Table 3.

The physicochemical and microbial properties of water samples collected Wallmansthal, Cullinan, Klipdrift, and Vaalkop WTPs, along with the RT-qPCR results for SARS-CoV-2.

| Parameters | Units | Wallmansthal WTP |

Cullinan WTP |

Klipdrift WTP |

Vaalkop WTP |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw | Final | Raw | Final | Raw | Final | Raw | WTP1 | WTP2 | WTP3 | WTP4 | ||

| Ammonia | mg/L | 2.15 ± 0.9 | 0.67 ± 0.5 | 0.07 ± 0 | 0.04 ± 0 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.6 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.1 ± 0.1 |

| Chlorine free | mg/L | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.64 ± 0.25 | 0.0 ± 0 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 0.0 ± 0 | 1.9 ± 0.9 | 0.0 ± 0 | 2.2 ± 2.4 | 3.4 ± 0.7 | 3.2 ± 1.6 | 1.5 ± 1.2 |

| E. coli | count/100 mL | 256 ± 85 | 0.0 ± 0 | 2.25 ± 2.1 | 0.0 ± 0 | 263.8 ± 96.6 | 0.0 ± 0 | 2.8 ± 2.2 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 |

| Conductivity | mS/m | 55.5 ± 0.8 | 58.2 ± 2.2 | 46.1 ± 1.6 | 48.6 ± 2 | 55.5 ± 0.9 | 56.7 ± 0.6 | 76.4 ± 1.1 | 78.8 ± 3 | 78.7 ± 2.3 | 60.7 ± 35.5 | 78.5 ± 0.6 |

| Faecal coliforms | count/100 mL | 278 ± 110 | 0.0 ± 0 | 3.5 ± 2.9 | 0.0 ± 0 | 363.3 ± 118.6 | 0.0 ± 0 | 7.3 ± 6.9 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 |

| Nitrate | mg/L N | 4.59 ± 0.75 | 5.09 ± 0.5 | 0.38 ± 0.1 | 0.37 ± 0.1 | 4.5 ± 1.6 | 4.0 ± 2 | 0.2 ± 0.3 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.3 |

| Orthophosphate | mg/L P | 1.3 ± 0.31 | 0.98 ± 0.1 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.23 ± 0.4 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.1 ± 0 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.1 ± 0.1 |

| pH @ 25 °C | pH units | 7.6 ± 0.48 | 8.2 ± 0.3 | 6.9 ± 0.2 | 7.5 ± 0.3 | 7.2 ± 0.5 | 7.6 ± 0.1 | 7.9 ± 0.1 | 7.6 ± 0.5 | 7.5 ± 0.4 | 7.5 ± 0.4 | 7.5 ± 0.3 |

| Somatic coliphages | count/10 mL | 6.0 ± 1.41 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 8.5 ± 2.9 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 |

| Temperature | °C | 24.5 ± 2.65 | 24.3 ± 2.2 | 26 ± 1.8 | 24.5 ± 2.4 | 24.5 ± 1.7 | 24.8 ± 2 | 25.3 ± 1.5 | 25.3 ± 1.7 | 23.8 ± 4 | 24.5 ± 1.9 | 24.5 ± 1.9 |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Ct | 0.0 ± 00 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 |

As explicitly highlighted in Table 3, the SARS-CoV-2 RNA was not detected in any of the surface water samples, let alone drinking water samples. The absence of the viral RNA in surface water could be primarily explained by its decay in WWTPs. Specifically, even though both examined WWTPs, and particularly the B WWTP, had a poor performance in microbiological contaminants removal, they were still able to attenuate the SARS-CoV-2 RNA from the early start of the treatment process. This is also supported by the existing body of knowledge, where it has been highlighted that enveloped viruses, such as the SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, are extremely susceptible to oxidation and they have short lifespans (Wang et al., 2005a; Lim et al., 2010; Cromeans et al., 2019). Furthermore, as mentioned above, no case of SARS-CoV-2 transmission through contaminated water has been reported so far (Giacobbo et al., 2021), while SARS-CoV could be completely inactivated through simple chlorination (20 mg/L chlorine for 60 s), with free chlorine being more promising than chlorine dioxide (Wang et al., 2005a). Since the SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA was attenuated within the examined WWTPs, while drinking water is properly treated (and chlorinated), the possibility of SARS-CoV-2 transmission from tap water is deemed minuscule to non-existent.

4. Insights into aqueous distribution of HCoVs

Survival of HCoVs in wastewater, and particularly of SARS-CoV-2, has been well documented in the literature (Amoah et al., 2020; Street et al., 2020; Saththasivam et al., 2021; Tran et al., 2021; Weidhaas et al., 2021). Numerous routes and modalities that influence the decay of HCoVs and other viruses in water and wastewater have also been proposed (Nemudryi et al., 2020; Rimoldi et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021). Similar to SARS-CoV (Wang et al., 2005a), genetic material of the SARS-CoV-2 virus has been identified in wastewater (Barcelo, 2020), with its decay being affected by various factors, including virus physiology, time outside the host, wastewater composition, temperature, and pH (Amoah et al., 2020). Furthermore, when outside the host, enveloped viruses exhibit shorter lifespans (Firquet et al., 2015). Thenceforth, the shorter survival time for enveloped viruses is dictated by the proteolytic enzymes and effects of detergents on the external lipid envelope of the virus (Conley et al., 2017; Amoah et al., 2020).

Based on the results of this study, high retention time (>2 h) and wastewater physicochemical characteristics during the PST stage are possibly amongst the main factors that resulted to SARS-CoV-2 decay in PST in the South African setting. The body of knowledge also suggest that the one of the main factors contributing to the observed decay of the SARS-CoV-2 genetic material in the PST stage could be the high wastewater temperature (>25 °C). Furthermore, genetic material was not identified in any of the examined surface water samples nor in drinking water. Regarding the latter, this was expected since the drinking water had undergone chlorination and enveloped viruses, such as the SARS-CoV-2, can be completely inactivated by chlorine (Lim et al., 2010; Amoah et al., 2020; Young et al., 2020). Regarding the fact that no genetic material was identified in the examined surface water samples (Table 3), this could be probably attributed to the facts that, i) during the time of the measurements the recorded cases were relatively low, since the field surveys took place at the onset of the second COVID-19 wave that hit South Africa, and ii) wastewater treatment infrastructure is in place, which as discussed above is effective in decaying the SARS-CoV-2 genetic material. However, catchment-wide monitoring can offer a snapshot of the status of the catchment in relation to SARS-CoV-2 and other contagious viruses and play a pivotal role in informing the custodians and downstream water users of potential risks.

5. Conclusions and recommendations

Findings of this study revealed the treatment stages where SARS-CoV-2 RNA was present and the ones where it had been eliminated within two wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) in South Africa. It was also identified that at the time of sampling (end of October to mid November 2020) surface water resources (river, canal, and dam) did not contain SARS-CoV-2 viral copies (below detection limit), even though genetic material was identified in raw wastewater. This implies that at the time of measurements, SARS-CoV-2 migration from wastewater to river, canal, and dam water was limited to non-existence. This was also the case for the treated water from those sources, which is used as drinking (potable) water by local communities.

Overall, this study detected the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in WWTP inflow (raw wastewater), however, the subsequent treatment stages demonstrated the deficiency of the virus hence denoting that the viral RNA had been eliminated in the PST. This highlights the need for wastewater treatment in South Africa and in the developing world, to protect receiving water bodies, e.g., rivers, canals, and dams, and human health. Furthermore, wastewater and catchment-wide water surveillance is required to identify the scale of COVID-19 infection along with possible SARS-CoV-2 RNA hotspots attributed to faecal contamination, i.e., wastewater leaching to ground water or river water. In light of the above, SARS-CoV-2 transmission from surface and drinking water, in the eventuality that the virus remains infective in those matrices, appears to be non-existent at the time of the measurements. However, a precautionary approach for public health should be adopted, based on the preliminary nature of these findings. For this reason, tertiary treatment (chlorination) should be adequately preformed (chemicals procurement in the South African setting can be problematic) and included across WWTPs in South Africa and further afield. This will not only eliminate the possibility of SARS-CoV-2 survival in water but will also reduce the release of high microbial loads, which negatively affects receiving waterbodies.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Vhahangwele Masindi (Conceptualization of the study, study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of data, writing and revision of the manuscript). Spyros Foteinis (Conceptualization of the study, study design, data analysis, interpretation of data, writing and revision of the manuscript). Kefilwe Nduli (Conception and design of study, acquisition of data, data analysis and interpretation of data), and Vhahangwele Akinwekomi (Conception and design of study, acquisition of data, data analysis and interpretation of data).

Declaration of competing interest

There is no conflicts of interest observed between the authors of this manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the municipalities and water boards that granted access to the researchers in their facilities and allow for the collection of the examined water matrices. Special thanks is cascaded to Magalies water for research funding and for the resources extended towards this project.

Editor: Damia Barcelo

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149298.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- Ahmed W., Angel N., Edson J., Bibby K., Bivins A., O'Brien J.W., Choi P.M., Kitajima M., Simpson S.L., Li J. First confirmed detection of SARS-CoV-2 in untreated wastewater in Australia: a proof of concept for the wastewater surveillance of COVID-19 in the community. Sci. Total Environ. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asghar H., Diop O.M., Weldegebriel G., Malik F., Shetty S., El Bassioni L., Akande A.O., Al Maamoun E., Zaidi S., Adeniji A.J., Burns C.C., Deshpande J., Oberste M.S., Lowther S.A. Environmental surveillance for polioviruses in the global polio eradication initiative. J. Infect. Dis. 2014;210(Suppl. 1):S294–S303. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin A.W.H., Chu J.T.S., Perera M.R.A., Hui K.P.Y., Yen H.-L., Chan M.C.W., Peiris M., Poon L.L.M. Stability of SARS-CoV-2 in different environmental conditions. Lancet Microbiol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30003-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellmér M., Paxéus N., Magnius L., Enache L., Arnholm B., Johansson A., Bergström T., Norder H. Detection of pathogenic viruses in sewage provided early warnings of hepatitis A virus and norovirus outbreaks. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;80(21):6771–6781. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01981-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R., Zhao X., Li J., Niu P., Yang B., Wu H., Wang W., Song H., Huang B., Zhu N. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medema G., Heijnen L., Elsinga G., Italiaander R., Brouwer A. Presence of SARSCoronavirus- 2 RNA in sewage and correlation with reported COVID-19 prevalence in the early stage of the epidemic in the Netherlands. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2020 doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randazzo W., Cuevas-Ferrando E., Sanjuan R., Domingo-Calap P., Sanchez G. medRxiv preprint; 2020. Metropolitan Wastewater Analysis for COVID-19 Epidemiological Surveillance. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2020. COVID-19 Weekly Epidemiological Update. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2021. COVID-19 Weekly Epidemiological Update.https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19---29-june-2021 [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Xiao A., Zhang J., Gu X., Lee W.L., Kauffman K., Hanage W., Matus M., Ghaeli N., Endo N., Duvallet C., Moniz K., Erickson T., Chai P., Thompson J., Alm E. SARS-CoV-2 titers in wastewater are higher than expected from clinically confirmed cases. mSystems. 2020;5 doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00614-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Li X., Zhu B., Liang H., Fang C., Gong Y., Guo Q., Sun X., Zhao D., Shen J. Characteristics of pediatric SARS-CoV-2 infection and potential evidence for persistent feacal viral shedding. Nat. Med. 2020;26(4):502–505. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0817-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amoah I.D., Kumari S., Bux F. Coronaviruses in wastewater processes: source, fate and potential risks. Environ. Int. 2020;143:105962. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcelo D. An environmental and health perspective for COVID-19 outbreak: meteorology and air quality influence, sewage epidemiology indicator, hospitals disinfection, drug therapies and recommendations. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020;8 doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2020.104006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos R. A global picture of the diverse links between water and health. Compt. Rendus Geosci. 2005;337:277–278. doi: 10.1016/j.crte.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley L., Tao Y., Henry A., Koepf E., Cecchini D., Pieracci J., Ghose S. Evaluation of eco-friendly zwitterionic detergents for enveloped virus inactivation. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2017;114:813–820. doi: 10.1002/bit.26209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cromeans T., Jothikumar N., Lee J., Collins N., Burns C.C., Hill V.R., Vinjé J. A new solid matrix for preservation of viral nucleic acid from clinical specimens at ambient temperature. J. Virol. Methods. 2019;274 doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2019.113732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firquet S., Beaujard S., Lobert P.-E., Sané F., Caloone D., Izard D., Hober D. Survival of enveloped and non-enveloped viruses on inanimate surfaces. Microbes Environ. 2015;30:140–144. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME14145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacobbo A., Rodrigues M.a.S., Zoppas Ferreira J., Bernardes A.M., De Pinho M.N. A critical review on SARS-CoV-2 infectivity in water and wastewater. What do we know? Sci. Total Environ. 2021;774 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gormley M., Aspray T.J., Kelly D.A. COVID-19: mitigating transmission via wastewater plumbing systems. Lancet Glob. Health. 2020;8 doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30112-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundy P.M., Gerba C.P., Pepper I.L. Survival of coronaviruses in water and wastewater. Food Environ. Virol. 2008;1:10. [Google Scholar]

- Kraay A.N.M., Hayashi M.a.L., Hernandez-Ceron N., Spicknall I.H., Eisenberg M.C., Meza R., Eisenberg J.N.S. Fomite-mediated transmission as a sufficient pathway: a comparative analysis across three viral pathogens. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018;18:540. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3425-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langone M., Petta L., Cellamare C.M., Ferraris M., Guzzinati R., Mattioli D., Sabia G. SARS-CoV-2 in water services: presence and impacts. Environ. Pollut. 2021;268:115806. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Zhang S., Shi J., Luby S.P., Jiang G. Uncertainties in estimating SARS-CoV-2 prevalence by wastewater-based epidemiology. Chem. Eng. J. 2021;415 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2021.129039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim M.Y., Kim J.-M., Ko G. Disinfection kinetics of murine norovirus using chlorine and chlorine dioxide. Water Res. 2010;44:3243–3251. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maclachlan N.J., Dubovi E.J. Elsevier Science; 2016. Fenner's Veterinary Virology. [Google Scholar]

- Masindi V., Foteinis S. Groundwater contamination in sub-saharan Africa: implications for groundwater protection in developing countries. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2021;2 [Google Scholar]

- Mattison K., Bidawid S., Farber J. In: Foodborne Pathogens. Second edition. Blackburn C.D.W., McClure P.J., editors. Woodhead Publishing; 2009. 25 - Hepatitis viruses and emerging viruses. [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa K., Lokugamage K.G., Makino S. In: Advances in Virus Research. Ziebuhr J., editor. Academic Press; 2016. Chapter five - viral and cellular mRNA translation in coronavirus-infected cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemudryi A., Nemudraia A., Wiegand T., Surya K., Buyukyoruk M., Cicha C., Vanderwood K.K., Wilkinson R., Wiedenheft B. Temporal detection and phylogenetic assessment of SARS-CoV-2 in municipal wastewater. Cell Rep. Med. 2020;1 doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2020.100098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paules C.I., Marston H.D., Fauci A.S. Coronavirus infections—more than just the common cold. JAMA. 2020;323:707–708. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.0757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne S. In: Viruses. Payne S., editor. Academic Press; 2017. Chapter 17 - family Coronaviridae. [Google Scholar]

- Rimoldi S.G., Stefani F., Gigantiello A., Polesello S., Comandatore F., Mileto D., Maresca M., Longobardi C., Mancon A., Romeri F., Pagani C., Cappelli F., Roscioli C., Moja L., Gismondo M.R., Salerno F. Presence and infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 virus in wastewaters and rivers. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;744 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saththasivam J., El-Malah S.S., Gomez T.A., Jabbar K.A., Remanan R., Krishnankutty A.K., Ogunbiyi O., Rasool K., Ashhab S., Rashkeev S., Bensaad M., Ahmed A.A., Mohamoud Y.A., Malek J.A., Abu Raddad L.J., Jeremijenko A., Abu Halaweh H.A., Lawler J., Mahmoud K.A. COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) outbreak monitoring using wastewater-based epidemiology in Qatar. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;774 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street R., Malema S., Mahlangeni N., Mathee A. Wastewater surveillance for Covid-19: an African perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;743 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tegally H., Wilkinson E., Giovanetti M., Iranzadeh A., Fonseca V., Giandhari J., Doolabh D., Pillay S., San E.J., Msomi N., Mlisana K., Von Gottberg A., Walaza S., Allam M., Ismail A., Mohale T., Glass A.J., Engelbrecht S., Van Zyl G., Preiser W., Petruccione F., Sigal A., Hardie D., Marais G., Hsiao M., Korsman S., Davies M.-A., Tyers L., Mudau I., York D., Maslo C., Goedhals D., Abrahams S., Laguda-Akingba O., Alisoltani-Dehkordi A., Godzik A., Wibmer C.K., Sewell B.T., Lourenço J., Alcantara L.C.J., Pond S.L.K., Weaver S., Martin D., Lessells R.J., Bhiman J.N., Williamson C., De Oliveira T. medRxiv; 2020. Emergence and Rapid Spread of a New Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-related Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Lineage With Multiple Spike Mutations in South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Toyoshima Y., Nemoto K., Matsumoto S., Nakamura Y., Kiyotani K. SARS-CoV-2 genomic variations associated with mortality rate of COVID-19. J. Hum. Genet. 2020;65:1075–1082. doi: 10.1038/s10038-020-0808-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran H.N., Le G.T., Nguyen D.T., Juang R.-S., Rinklebe J., Bhatnagar A., Lima E.C., Iqbal H.M.N., Sarmah A.K., Chao H.-P. SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus in water and wastewater: a critical review about presence and concern. Environ. Res. 2021;193 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trombetta H., Faggion H.Z., Leotte J., Nogueira M.B., Vidal L.R.R., Raboni S.M. Human coronavirus and severe acute respiratory infection in Southern Brazil. Pathog. Glob. Health. 2016;110:113–118. doi: 10.1080/20477724.2016.1181294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulchinsky T.H., Varavikova E.A. In: The New Public Health. Third edition. Tulchinsky T.H., Varavikova E.A., editors. Academic Press; San Diego: 2014. Chapter 4 - communicable diseases. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.-W., Li J.-S., Jin M., Zhen B., Kong Q.-X., Song N., Xiao W.-J., Yin J., Wei W., Wang G.-J., Si B.-Y., Guo B.-Z., Liu C., Ou G.-R., Wang M.-N., Fang T.-Y., Chao F.-H., Li J.-W. Study on the resistance of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus. J. Virol. Methods. 2005;126:171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.W., Li J., Guo T., Zhen B., Kong Q., Yi B., Li Z., Song N., Jin M., Xiao W., Zhu X., Gu C., Yin J., Wei W., Yao W., Liu C., Li J., Ou G., Wang M., Fang T., Wang G., Qiu Y., Wu H., Chao F., Li J. Concentration and detection of SARS coronavirus in sewage from Xiao Tang Shan hospital and the 309th Hospital of the Chinese People's Liberation Army. Water Sci. Technol. 2005;52:213–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidhaas J., Aanderud Z.T., Roper D.K., Vanderslice J., Gaddis E.B., Ostermiller J., Hoffman K., Jamal R., Heck P., Zhang Y., Torgersen K., Laan J.V., Lacross N. Correlation of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater with COVID-19 disease burden in sewersheds. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;775 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young S., Torrey J., Bachmann V., Kohn T. Relationship between inactivation and genome damage of human enteroviruses upon treatment by UV254, free chlorine, and ozone. Food Environ. Virol. 2020;12 doi: 10.1007/s12560-019-09411-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Guo R., Kim S.H., Shah H., Zhang S., Liang J.H., Fang Y., Gentili M., Leary C.N.O., Elledge S.J., Hung D.T., Mootha V.K., Gewurz B.E. SARS-CoV-2 hijacks folate and one-carbon metabolism for viral replication. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:1676. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21903-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material