Abstract

Background:

In 2016, at least 20% of people with opioid use disorder (OUD) were involved in the criminal justice system, with the majority of individuals cycling through jails. Opioid overdose is the leading cause of death and a common cause of morbidity after release from incarceration. Medications for OUD (MOUD) are effective at reducing overdoses, but few interventions have successfully engaged and retained individuals after release from incarceration in treatment.

Objective:

To assess whether follow-up care in the Transitions Clinic Network (TCN), which provides OUD treatment and enhanced primary care for people released from incarceration, improves key measures in the opioid treatment cascade after release from jail. In TCN programs, primary care teams include a community health worker with a history of incarceration, which attend to social needs such as housing, food insecurity and criminal legal system contact, along with patients’ medical needs.

Methods and Analysis:

We will bring together six correctional systems and community health centers with TCN programs to conduct a hybrid type 1 effectiveness/implementation study among individuals who were released from jail on MOUD. We will randomize 800 individuals on MOUD released from seven local jails (Bridgeport, CT; Niantic, CT; Bronx, NY; Caguas, PR; Durham, NC; Minneapolis, MN; Ontario County, NY) to compare the effectiveness of a TCN intervention versus referral to standard primary care to improve measures within the opioid treatment cascade. We will also determine what social determinants of health are mediating any observed associations between assignment to the TCN program and opioid treatment cascade measures. Lastly, we will study the cost effectiveness of the approach, as well as individual, organizational, and policy level barriers and facilitators to successfully transitioning the care of individuals on MOUD from jail to the TCN.

Ethics and Dissemination:

Investigation Review Board the University of North Carolina (IRB Study # 19-1713), the Office of Human Research Protections, and the NIDA JCOIN Data Safety Monitoring Board approved the study. We will disseminate study findings through peer-reviewed publications and academic and community presentations. We will disseminate study data through a web-based platform design to share data with TCN PATHS participants and other TCN stakeholders. Clinicaltrials.gov registration: NCT04309565.

Keywords: Incarceration, Re-entry, Opioid-use Disorders, Primary Health Care, Medications for Opioid-use disorders (MOUD)

1. Introduction

As correctional facilities increase availability of medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD), few interventions have successfully engaged and retained people with OUD in evidence-based addiction treatment after release. Individuals with a history of incarceration carry a disproportionately high risk of morbidity and mortality from opioid overdose following release from correctional facilities (Binswanger, 2013; Ranapurwala et al., 2018). Between 2000 and 2014, as the United States experienced a 200% increase in opioid-related overdose mortality (Rudd, Aleshire, Zibbell, & Gladden, 2016), individuals with criminal justice involvement accounted for 10-50% of overdose deaths (Hennepin County Criminal Justice Coordinating Committee, 2018; Kuzyk, Baudoin, & Bobula, 2017). The high risk of mortality is due, in part, to low rates of MOUD availability in jail (Alex et al., 2017).

Even in settings where individuals are released from jail to the community on MOUD, engagement in care following release is low. A study from Connecticut suggests that only 40% of individuals continued on methadone during incarceration return to methadone treatment following release (Moore, Oberleitner, Smith, Maurer, & McKee, 2018). There are a number of individual, community, health system, and policy barriers which contribute to low patient engagement. At the individual level, many people with OUD leaving jail face housing instability, food insecurity, and transportation barriers, which can impact treatment engagement (Binswanger et al., 2012; Fox et al., 2015; van Olphen, Freudenberg, Fortin, & Galea, 2006). People often return to social networks or neighborhoods that trigger a return to substance use (Lichtenstein, 1997; Lindquist, 2000; Richie, Freudenberg, & Page, 2001). People with OUD and criminal justice involvement also face stigma and discrimination in the health system because of their criminal record, which affects their treatment decisions after release (Fox et al., 2015; Fu, Zaller, Yokell, Bazazi, & Rich, 2013; Maradiaga, Nahvi, Cunningham, Sanchez, & Fox, 2016). Further, community-based methadone treatment providers and buprenorphine prescribers do not typically have the ability or capacity to coordinate timely care upon release from jail (Jones, Campopiano, Baldwin, & McCance-Katz, 2015). These substantial barriers may be compounded by addiction treatment and community health centers which often have restrictive policies on drug testing, MOUD dispensing, and required ancillary treatments which create a high threshold for treatment. In addition, there are barriers caused by policies in community corrections programs, where use of MOUD can be at the discretion of individual parole and probation officers or outright banned (Beletsky et al, 2015).

A key knowledge gap that remains is how to overcome the individual, social, and contextual factors that decrease post-release engagement in treatment and increase overdose morbidity and mortality. In 2008, we developed a model of primary care for individuals recently released from correctional facilities in partnership with people with a history of incarceration, which has grown into a national network of 40 community health centers, known as Transitions Clinic Network (TCN) (Bedell, Wilson, White, & Morse, 2015; Fox, Anderson, Bartlett, Valverde, MacDonald, et al., 2014; Fox, Anderson, Bartlett, Valverde, Starrels, et al., 2014; Morse et al., 2017; Shavit et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2012). The TCN aims to promote healthy return to the community for individuals who are released from correctional facilities. At the core of TCN programs are formerly incarcerated community health workers (CHWs) who are embedded within primary care teams to address social determinants of health, provide social support, coordinate care, and address stigma and discrimination. Unlike intensive case management, which has not improved post-release health care utilization (Wohl et al., 2011), CHWs work directly with clinicians providing team-based care and care coordination. TCN programs offer open-access primary care, office-based OUD treatment, and support for interactions with the criminal justice system.

We aim to evaluate the effectiveness and implementation of the TCN program on post-release outcomes of people treated with MOUD. We hypothesize that TCN participants will have higher rates of OUD treatment engagement and retention, higher rates of MOUD continuation, and lower rates of illicit opioid use compared to those referred to standard primary care (SPC). Further, we hypothesize that attending to social factors (housing, food insecurity, social support, and criminal justice contact) within the TCN program is driving these improved outcomes.

2. Methods

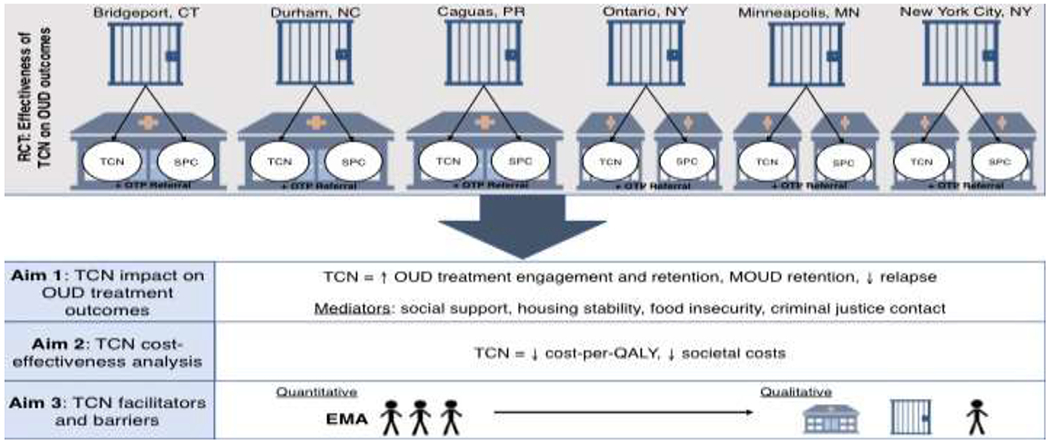

We propose a hybrid type 1 study that allows for the simultaneous collection of effectiveness and implementation data (Figure 1) (Curran, Bauer, Mittman, Pyne, & Stetler, 2012). The Transitions Clinic Network: Post Incarceration Addiction Treatment, Healthcare, and Social Support (TCN-PATHS) study will bring together six correctional systems and community health centers from across the country (Bridgeport and Niantic, CT; Bronx, NY; Ponce, PR; Bayamon, PR; Durham, NC; Minneapolis, MN; Ontario County, NY) to recruit 800 individuals on MOUD in jail who will be randomized into either a referral into the TCN primary care program or a referral into SPC after release. Participants will be followed for 12 months to examine differences in opioid treatment cascade (i.e., engagement, medication continuation, retention, and relapse) between the groups (Williams, Nunes, Bisaga, Levin, & Olfson, 2018).

Figure 1: TCN PATHS Hybrid Type 1 Effectiveness Implementation Study Schema.

Legend: TCN = Transition Clinic Network intervention arm, SPC = Standard Primary Care comparison arm, OUD = Opioid Use Disorder, MOUD = Medications for Opioid Use Disorder, QALY = Quality Adjusted Life Year, OTP = opioid treatment program

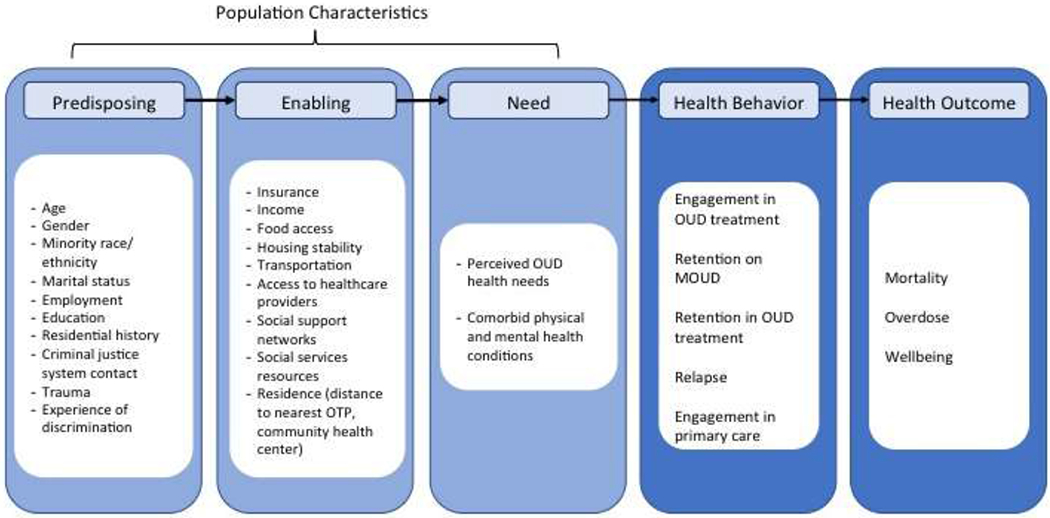

2.1. Conceptual framework: Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations

People with OUD released from correctional facilities have intertwined health and social needs, which present barriers to engaging in OUD treatment (Figure 2). In the Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations (Gelberg, Andersen, & Leake, 2000), predisposing, enabling, and need factors, both in traditional and vulnerable domains, predict engagement in OUD treatment, which in turn predicts health outcomes.

Figure 2: Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations adapted for people with OUD.

Legend: OUD = Opioid Use Disorder, MOUD = Medications for Opioid Use Disorder

Beyond predisposing traditional factors, individuals released from jail have many predisposing vulnerable factors, including minority race, high rates of discrimination, and criminal justice system contact. They also have limited access to stable housing and food. Fifteen percent report homelessness immediately before their incarceration (Greenberg & Rosenheck, 2008), and housing status is strongly associated with OUD treatment outcomes (Damian, Mendelson, & Agus, 2017; Roux et al., 2014). More than 90% of individuals released from correctional facilities meet United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) criteria for food insecurity, and hunger is associated with increased rates of injection drug use (Wang et al., 2013). Rates of recidivism, or return to jail, are high in the first-year post release and can be a significant disruption in one’s engagement in OUD treatment (Binswanger et al., 2012).

Enabling factors in the vulnerable domain, such as resources that facilitate OUD treatment, including health insurance access, transportation, and access to healthcare providers and social support networks (Spjeldnes, Jung, Maguire, & Yamatani, 2012), are also impacted by jail incarceration. Vulnerable need factors, individuals’ perceived and evaluated health needs, are multiple and more common for individuals released from jail, including OUD and other chronic health conditions (Binswanger, Krueger, & Steiner, 2009; Lim et al., 2012; Winkelman, Chang, & Binswanger, 2018). Interventions that address the predisposing and need factors while promoting enabling factors lead to engagement in OUD treatment and improved long-term outcomes.

2.2. Hybrid Type 1 Study: Recruitment, Eligibility and Randomization

Potential participants will be identified in collaboration with medical staff from the local jails and will be referred for eligibility screening. TCN PATHS research staff will screen participants in private rooms and details of study participation will be not disclosed to jail staff. Individuals will be eligible for study participation if they are 18 years of age or older, speak English or Spanish, and have been on MOUD while in jail, in jail for at least 14 days, and are likely to be released in the next 30 days. Individuals can either be continued or initiated on MOUD while in jail. Individuals will not be eligible if they have active severe psychiatric disease (psychosis, suicidality, or homicidality), require prescribed opioids for acute pain or palliative care, are planning to relocate out of the study area, have an established relationship with a primary care provider, or are currently pregnant.

Consented participants will be randomized at the time of recruitment with even allocation between the TCN intervention and SPC. Randomization will be achieved via the Pocock-Simon minimization algorithm, a covariate-adaptive randomization method to ensure balance in the study groups (Pocock & Simon, 1975) with regards to gender, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and other), MOUD initiation versus continuation in jail, and MOUD modality. Based on the demographics of the jails from which we are recruiting, we anticipate the racial/ethnic breakdown of participants will be the following: 44% non-Latino Black, 23% non-Latino White, 16% Latino, and 17% other. Similarly, we anticipate 20% female and 80% male participants. Participants will be given an appointment within 2 weeks of release for either TCN or SPC and a referral to opioid treatment program (OTP) no matter the modality of MOUD.

2.3. Intervention and Comparison Arm

Participants randomized to the TCN intervention will be referred to a TCN program at the time of release. All TCN programs are embedded in safety-net primary care clinics which have the capability of prescribing buprenorphine and extended-release naltrexone (XR-NTX). The TCN CHW will connect with participants prior to release from jail when possible and continue support participants following release, connecting them to resources to address social determinants of health, self-stigma, and discrimination related to a history of incarceration. At the first TCN visit, health care providers will assess the impact of substance use on participants’ functioning, discuss OUD treatment preferences and experiences, educate participants about relapse prevention, and identify and address co-morbid health and conditions. At this visit and all subsequent visits, the CHW will assess social determinants of health and provide connections to community organizations depending on patient preference and prioritization of needs.

CHW will log daily interactions with participants to measure fidelity to the treatment intervention. These logs will be reviewed and the research team will also conduct regular calls across sites to troubleshoot obstacles and share successful strategies. At six-month intervals, we will measure penetration of and fidelity to the TCN model use a standard implementation and fidelity assessment tool.

Participants randomized to SPC will be referred to an OTP and given an appointment with a community primary care clinic within 2 weeks of their release. The referral will either be to a different clinic location in the same community health center system of the TCN program or to a different provider in the same community health center clinic if no alternate clinic exists.

Beyond the TCN intervention or expedited referral, participants in both arms will be eligible to receive all typical services provided at that site, such as jail-based care, discharge planning, community correctional supervision, health insurance access, and community-based services.

2.4. Data Collection

Survey data will be collected in person by the research team at the time of enrollment as well as one month, 6 months, and 12 months post release. The research team will also connect with participants via telephone at 3 and 9 months post release for a brief survey and update of contact information (Table 1). Participants completing all of the core study protocols including six surveys and seven phone check-ins will receive $315.

Table 1:

Study measurements for TCN PATHS study

| Domain | Components/method of assessment/measurement instrumenta | When Assessed | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | Age, sex, race, ethnicity, marital status, level of education | BL | Covariate |

|

Residential data distance to nearest OTP, buprenorphine prescriber, community health center |

Zip Code | 1, 6, 12 months | Covariate |

| Health | |||

| Medical and mental health comorbidities History of OUD and MOUD treatment |

List of medical and mental health conditions | BL | Covariate |

| Addiction severity, use of other illicit drugs, and trauma | Self-report | BL, 1, 6, 12 months | Covariate |

| Wellbeing/quality of life, pain, and depression symptoms Discrimination |

Self-report via PROMIS 29+2/PROPr instrument Self-report via Everyday Discrimination Scale (short version) |

BL, 1, 6 and 12 months | Secondary outcome |

| Opioid Use Disorder treatment cascade and related outcomes | |||

| Engagement in OUD treatment Retention in OUD treatment Retention on MOUD Illicit opioid use: # of days of use in the past month |

Self-report confirmed with electronic health record or treatment facility Self-report using TimeLine FollowBack; urine toxicology positive for illicit opioids |

1 month 1, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months |

Primary Outcome |

| Overdose | Self-report; electronic health record | BL, 1, 3, 6, 9, 12 months | Secondary Outcome Cost analysis |

| Death | Electronic health record | 1, 6, 12 months | Secondary Outcome; CEA |

| Health Care Utilization and Experience | |||

| Drug Abuse Treatment Cost Analysis Program | Self-report | 1, 6 and 12 months | CEA |

| Primary Care Engagement, Acute care utilization | Self-report; electronic health record | 1, 3, 6, 9, 12 months | Secondary Outcome; CEA |

| Social determinants of health | |||

| Housing stability Food insecurity Social support Criminal Justice Contact |

Self-report; Self-report; criminal justice contact confirmed via Department of Corrections data |

1, 3, 6, 9, 12 months | Putative mediator; Putative mediator and CEA |

| Psychosocial factors | |||

| Self-stigma | Self-report | BL, 1, 6 and 12 months after release; | Covariate Cost Analysis (QOL) |

| Policy measures | |||

| Criminal Justice System Policies Collateral consequences |

Access to MOUD in halfway house, Access to naloxone, Access to benefits; Housing, food stamp, licensure bans | 1, 6, 12 months | Covariate |

- validated instruments used are listed where applicable

Legend: BL = Baseline assessment, OTP = Opioid Treatment Program, OUD = Opioid Use Disorder, MOUD = Medications for Opioid Use Disorder, CEA = Cost effectiveness Analysis, QOL - Quality of Life

2.5. Primary Outcome: OUD treatment engagement

The primary study outcome will be engagement in OUD treatment within 30 days of release, defined as treatments consistent with the American Society of Addiction Medicine’s levels of care (1-4), which allows for a range of treatments and clinical settings consistent with patient’s needs and preference. Patients do not need to be receiving MOUD to be considered engaged in OUD treatment. We will use this 30-day outcome based on the key role that initial short term engagement plays in OUD treatment outcomes (D’Onofrio et al., 2015). We will define retention on MOUD as receipt of any of the 3 Food and Drug Administration-approved medications within 7 days of the release from jail regardless of what MOUD they were on at baseline. We will use TimeLine FollowBack method to identify how many days in the past month participants have used illicit opioids.

2.6. Secondary Outcomes and Covariates

We will examine secondary outcomes: wellbeing, retention in primary care, emergency department visits, overdose, and death. We will also use linkages of administrative data from electronic health records/Medicaid and corrections, where available, to examine the durability of the intervention through two years. We will gather self-reported demographic information and health measures, including medical and mental health conditions, OUD history, previous experience with MOUD, and measures of addiction severity at baseline, 1, 6, and 12 months following release. We will also gather measures of social needs and social determinants of health including housing stability, food security, criminal justice contact (including reincarceration), and social support, as potential mediators.

2.7. Data Analysis

We will conduct an intention-to-treat analysis for each of the primary and secondary outcomes. Several types of descriptive and advanced statistical techniques will be used to test the main hypothesis. For the primary outcomes of engagement in OUD treatment and retention on any MOUD at 30 days, multivariate logistic regression will be applied to determine the TCN intervention effect. For other repeated measured outcomes, such as opioid use or retention on MOUD, the primary statistical method to determining the intervention effects will be the 2-level hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) (Gibbons et al., 1993; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). When applying 2-level HLM to analyze longitudinal data, the repeated observations at 1, 3, 6, 9 and 12 month follow-ups are level-1 data nested within individuals (level-2 data). Depending on the distribution of outcome measures, different functions such as logit for binary outcome measures (i.e., re-engagement in MOUD), Poisson for count data (days of illicit opioid use) or normal for continuous outcomes (e.g., wellbeing, quality of life) will be linked to estimate the TCN intervention effect. We will use HLM because it accounts for the lack of statistical independence for the repeated measures by incorporating the intra-class correlation and it can accommodate unbalanced data due to attrition at the follow-up measures. HLM also allows treating time as continuous variable, accommodating either time-varying or invariant covariates like recidivism or days in the community. Given natural variation across TCN program sites and jails, we will also conduct a sensitivity analysis where TCN site will be included in multivariate models as a covariate.

For the mediation analysis, we will first use longitudinal 2-level HLM analysis to compare how housing status (yes/no) and number of moves, food insecurity (yes/no), social support (yes/no), and criminal justice contact (days re-incarcerated) vary between the TCN and SPC arm. We will then employ a Latent Growth Curve Model analysis (McArdle & Bell, 2000), a class of models for longitudinal data that can be analyzed in structural equation modeling (SEM), to assess the mediating effects of these social determinants on the primary outcomes. SEM can incorporate complex path models and is especially effective and efficient in testing mediating effects, as well as complex theoretically-derived models (Bollen, 1989). Lastly, using linked administrative data from Medicaid/electronic health record and the Department of Corrections we will conduct survival analysis using Cox proportional-hazards model to determine whether participants assigned to the TCN remain in OUD treatment and continue taking MOUD longer than the comparison group, and whether and when participants die as the result of overdose.

2.8. Cost Effectiveness Analysis

The ability to conduct Cost Effectiveness Analysis (CEA) alongside the TCN PATHS clinical trial allows for more precise micro-costing of intervention resources and more robust cost effectiveness findings after controlling for potentially confounding factors. The primary effectiveness outcome will be cost per Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALY) collected using the PROMIS 29+2/PROPr, using the consensus that interventions resulting in an average cost-per-QALY gained of less than $100,000 in the U.S. are cost effective (Neumann, Cohen, & Weinstein, 2014; Neumann, Sanders, Russell, Siegel, & Ganiats, 2016). The CEA will be conducted from the healthcare sector and societal perspectives.

Costs will be estimated using financial information received by the study team and will be measured at baseline, 6 months and 12 months. These data will be supplemented with data collected in semi-structured interviews with community clinical leaders that will allow us to assign individual resources (time and materials) used to deliver the intervention, including the costs of the CHW. Outcomes include total annual program cost, average annual cost per patient; average cost per treatment episode (per patient). Notably, all research related costs and start-up costs such as training of CHWs will not be included because these would not be incurred if TCN programs were standard care. Healthcare sector, criminal justice sector, and other societal costs will be estimated using measures collected as part of the main outcome assessments.

2.9. Implementation evaluation

We will measure the acceptability and appropriateness of the intervention and multi-level barriers and facilitators in real time, which will optimize the intervention and improve future efforts to disseminate and scale. Using a mixed methods sequential explanatory model, we will use intensive longitudinal assessment (ILA) to measure multi-level facilitators and barriers of OUD treatment engagement in the first 30 days following release that will then inform subsequent qualitative interviews and focus groups (Scheider, Junghaenel, Gutsche, Mak, & Stone, 2020).

For the ILA, 20 participants randomized to each TCN site (a total of 120 people) will be offered participation. Participants will be compensated $20 if they contact the research assistant within 3 days after release and download the app onto their phones. The participants will receive two short surveys each day. They will receive an additional $10/week if they complete 75% (11/14) of the diary entries that week.

We will customize an electronic data collection application, TryCycle, designed for use on smartphones that pushes questions to participants at pre-programmed times. The app captures a time and date stamp at the moment each question is pushed to a participant. We will include questions that are related to TCN intervention acceptability (e.g. have you been contacted by your CHW today; is the way s/he contacted you your preferred method); and appropriateness (e.g. does speaking with your CHW help deal with the issues you may be facing today). We will also ask questions relevant to engaging in OUD treatment (e.g., discrimination, psychosocial stress, self-reported health, socioeconomic factors), followed by questions about how various policies and organizational barriers and facilitators support engagement.

Guided by data from the ILA, we will conduct 60 interviews with key correctional and community health center staff and focus groups will be conducted with TCN participants stratified by gender at each TCN site. Focus groups will be done separately for women and men to understand if and how factors affect them differently. These interviews and focus groups will uncover multi-level barriers and facilitators to TCN program and the transition of MOUD treatment from jail to the community.

2.10. COVID-19 Adaptations

We will adapt the study protocol as necessary for the safety of participants and study personnel, as dictated by public health, university, and jail policies and the incidence of COVID-19 in the community and jail. Study participants will be recruited and consented from jail using video conferencing procedures to minimize in-person contact. Correctional staff will help set up video conferencing, but will then leave the potential participant alone in a private office for consent and survey. Should in-person recruitment and follow up surveys be permitted, study personnel will don personal protective equipment that protect staff from COVID-19 transmission.

2.11. Ethical Considerations

All study procedures, materials, and protocols will be approved by institutional review board through a single IRB application at the University of North Carolina and the Office of Human Research Protections. Study data will be protected by a Certificate of Confidentiality. These protections prevent disclosure of study data to any entity, including law enforcement, without consent of the participant. All efforts will be made by the research team, in collection, storage, analysis, and dissemination of data, to protect participant’s privacy and confidentiality. All research staff will also be trained on how to engage with correctional staff, community corrections or other community service agencies in ways that protect participant’s privacy. National Institute of Drug Abuse JCOIN Data Safety Monitoring Board will approve the study protocol and monitor adverse events and study progress.

Our study is unique in that we include people with a history of incarceration in the design, implementation, conduct, analysis, and dissemination of study findings. Not only does TCN PATHS study the integration of CHWs with histories of incarceration in a primary care-based program, but we have also convened an expert panel which includes a community leader and people with histories of incarceration who are teaching CHWs on OUD and implementation of the TCN program.

We will adapt a health informatics platform designed with input from TCN participants and CHWs to share de-identified study data with participants, policymakers, and the public. The study team has significant experience disseminating study results and translating findings into clinical practice and program development, including developing a health informatics platform (Web Analytics Research Platform, WARP) designed using community-based participatory research methods to enable people with a history of incarceration to access and analyze research data (Elumn et al., 2019; Wang, Marenco, Madera, Aminawung, Wang, & Cheung, 2017). We will work with the JCOIN Methodology and Advanced Analytics Resource Center to ensure our data can be shared and merged with data across other JCOIN initiatives.

3. Anticipated Results

TCN PATHS will be among the first multi-site study among individuals just released from jail on MOUD to evaluate the effectiveness of an enhanced primary care program staffed by a CHW with a history of incarceration on improving OUD treatment cascade. We will determine several questions about the TCN intervention such as:

If the TCN program is effective in improving engagement and retention in OUD treatment, what factors are associated with improved outcomes?

Is this a cost-effective intervention?

Which sectors are likely to benefit from the intervention?

What are barriers and facilitators of successful TCN programs?

4. Conclusions

Correctional facilities are increasingly implementing MOUD programs, but the transitions of care back to the community are often ineffective. TCN-PATHS is a hybrid type 1 effectiveness/implementation study which will measure the effectiveness of the TCN intervention in improving opioid use disorder treatment cascade measures and identify potential mechanisms by which TCN intervention may improve OUD outcomes. The study will also provide data on the cost effectiveness and facilitators for implementing TCN in community health centers. This proposal will lead to actionable next steps for patients, health systems, correctional systems, and taxpayers on how best to use CHWs embedded within primary care to improve the health of people with OUD.

Highlights:

Few interventions have successfully engaged and retained people with OUD in evidence-based addiction treatment after release from jail.

No randomized controlled trial has tested whether an enhanced primary care model is effective for longitudinal and comprehensive care for this high-risk population with OUD.

TCN PATHS will be the first multi-site study to evaluate the effectiveness of an enhanced primary care program for individuals released from jail on MOUD on measures within the OUD treatment cascade.

TCN PATHS with also evaluate whether addressing social determinants of health after release from jail impacts measures within the OUD treatment cascade.

Acknowledgements

This work is funded by NIH/NIDA (UG1DA050072).

References

- Alex B, Weiss DB, Kaba F, Rosner Z, Lee D, Lim S, … MacDonald R (2017). Death after jail release: matching to improve care delivery. Journal of Correctional Health Care, 23(1), 83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedell P, Wilson JL, White AM, & Morse DS (2015). “Our commonality is our past:” a qualitative analysis of re-entry community health workers’ meaningful experiences. Health & justice, 3(1), 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beletsky L, LaSalle L, Newman M, Pare J, Tam J, & Tochka A (2015). Fatal re-entry: legal and programmatic opportunities to curb opioid overdose among individuals newly released from incarceration. NEULJ, 7, 149. [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger IA (2013). Mortality After Prison Release: Opioid Overdose and Other Causes of Death, Risk Factors, and Time Trends From 1999 to 2009. Ann Intern Med Annals of Internal Medicine, 159(9), 592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger IA, Krueger PM, & Steiner JF (2009). Prevalence of chronic medical conditions among jail and prison inmates in the USA compared with the general population. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 63(11), 912–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger IA, Nowels C, Corsi KF, Glanz J, Long J, Booth RE, & Steiner JF (2012). Return to drug use and overdose after release from prison: a qualitative study of risk and protective factors. Addict Sci Clin Pract, 7(1), 3. doi: 10.1186/1940-0640-7-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA (1989). Structural equations with latent variables Wiley. New York. [Google Scholar]

- Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, & Stetler C (2012). Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Medical care, 50(3), 217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio G, O’Connor PG, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, Busch SH, Owens PH, Fiellin DA (2015). Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 313(16), 1636–1644. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.3474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damian AJ, Mendelson T, & Agus D (2017). Predictors of buprenorphine treatment success of opioid dependence in two Baltimore City grassroots recovery programs. Addictive behaviors, 73, 129–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elumn Madera J, Aminawung JA, Carroll-Scott A, Calderon J, Cheung KH, Marenco L, Wang K, & Wang EA (2019). The Share Project: building capacity of justice-involved individuals, policymakers, and researchers to collectively transform health care delivery. American journal of public health, 109(1), 113–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox AD, Anderson MR, Bartlett G, Valverde J, MacDonald RF, Shapiro LI, & Cunningham CO (2014). A description of an urban transitions clinic serving formerly incarcerated persons. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved, 25(1), 376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox AD, Anderson MR, Bartlett G, Valverde J, Starrels JL, & Cunningham CO (2014). Health outcomes and retention in care following release from prison for patients of an urban post-incarceration transitions clinic. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved, 25(3), 1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox AD, Maradiaga J, Weiss L, Sanchez J, Starrels JL, & Cunningham CO (2015). Release from incarceration, relapse to opioid use and the potential for buprenorphine maintenance treatment: a qualitative study of the perceptions of former inmates with opioid use disorder. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 10(1), 2. doi: 10.1186/s13722-014-0023-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu JJ, Zaller ND, Yokell MA, Bazazi AR, & Rich JD (2013). Forced withdrawal from methadone maintenance therapy in criminal justice settings: a critical treatment barrier in the United States. Journal of substance abuse treatment, 44(5), 502–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelberg L, Andersen RM, & Leake BD (2000). The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health services research, 34(6), 1273. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons RD, Hedeker D, Elkin I, Waternaux C, Kraemer HC, Greenhouse JB, … Watkins JT (1993). Some conceptual and statistical issues in analysis of longitudinal psychiatric data: Application to the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program dataset. Archives of General Psychiatry, 50(9), 739–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg GA, & Rosenheck RA (2008). Jail incarceration, homelessness, and mental health: a national study. Psychiatric services, 59(2), 170–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennepin County Criminal Justice Coordinating Committee (2018). The Opioid Epidemic: Public Safety Intnerventions & Justice-Invovled Supports. Retrieved from https://www.hennepin.us/-/media/hennepinus/your-government/leadership/documents/cjcc-opioid-report-jul-2018.pdf?la=en. Accessed November 25, 2020.

- Jones CM, Campopiano M, Baldwin G, & McCance-Katz E (2015). National and state treatment need and capacity for opioid agonist medication-assisted treatment. American journal of public health, 105(8), e55–e63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzyk I, Baudoin K, & Bobula K (2017). Opioid and criminal justice in CT. Retrieved from https://www.ct.gov/opm/lib/opm/cjppd/cjabout/opioid_presentation_06092017.pdf

- Lichtenstein B (1997). Women and Crack-Cocaine Use: A Study of Social Networks and HIV Risk in An Alabama Jail Sample. Addiction Research, 5(4), 279–296. doi: 10.3109/16066359709004343 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S, Seligson AL, Parvez FM, Luther CW, Mavinkurve MP, Binswanger IA, & Kerker BD (2012). Risks of drug-related death, suicide, and homicide during the immediate post-release period among people released from New York City jails, 2001-2005. Am J Epidemiol, 175(6), 519–526. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist C (2000). Social integration and mental well-being among jail inmates. Paper presented at the Sociological Forum 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Maradiaga JA, Nahvi S, Cunningham CO, Sanchez J, & Fox AD (2016). “I kicked the hard way. I got incarcerated.” Withdrawal from methadone during incarceration and subsequent aversion to medication assisted treatments. Journal of substance abuse treatment, 62, 49–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle J, & Bell R (2000). Recent trends in modeling longitudinal data by latent growth curve methods. Modeling longitudinal and multiple-group data: practical issues, applied approaches, and scientific examples, 69–107. [Google Scholar]

- Moore KE, Oberleitner L, Smith KMZ, Maurer K, & McKee SA (2018). Feasibility and Effectiveness of Continuing Methadone Maintenance Treatment During Incarceration Compared With Forced Withdrawal. J Addict Med, 12(2), 156–162. doi: 10.1097/adm.0000000000000381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse DS, Wilson JL, McMahon JM, Dozier AM, Quiroz A, & Cerulli C (2017). Does a primary health clinic for formerly incarcerated women increase linkage to care? Women’s Health Issues, 27(4), 499–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann PJ, Cohen JT, & Weinstein MC (2014). Updating cost-effectiveness—the curious resilience of the $50,000-per-QALY threshold. New England Journal of Medicine, 371(9), 796–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann PJ, Sanders GD, Russell LB, Siegel JE, & Ganiats TG (2016). Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pocock SJ, & Simon R (1975). Sequential treatment assignment with balancing for prognostic factors in the controlled clinical trial. Biometrics, 31(1), 103–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranapurwala SI, Shanahan ME, Alexandridis AA, Proescholdbell SK, Naumann RB, Edwards D, & Marshall SW (2018). Opioid Overdose Mortality Among Former North Carolina Inmates: 20002015. American Journal of Public Health, 108(9), 1207–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, & Bryk AS (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods (Vol. 1): Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Richie BE, Freudenberg N, & Page J (2001). Reintegrating women leaving jail into urban communities: a description of a model program. Journal of Urban Health-Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 78(2), 290–303. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.2.290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux P, Lions C, Michel L, Cohen J, Mora M, Marcellin F, … Karila L (2014). Predictors of non-adherence to methadone maintenance treatment in opioiddependent individuals: Implications for clinicians. Current pharmaceutical design, 20(25), 4097–4105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, & Gladden RM (2016). Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2000–2014. American Journal of Transplantation, 16(4), 1323–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider S, Junghaenel DU, Gutsche T, Mak HW, Stone AA (2020) Comparability of Emotion Dynamics Derived From Ecological Momentary Assessments, Daily Diaries, and the Day Reconstruction Method: Observational Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(9):e19201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shavit S, Aminawung JA, Birnbaum N, Greenberg S, Berthold T, Fishman A, … Wang EA (2017). Transitions Clinic Network: Challenges And Lessons In Primary Care For People Released From Prison. Health Aff (Millwood), 36(6), 1006–1015. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spjeldnes S, Jung H, Maguire L, & Yamatani H (2012). Positive family social support: Counteracting negative effects of mental illness and substance abuse to reduce jail ex-inmate recidivism rates. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 22(2), 130–147. [Google Scholar]

- van Olphen J, Freudenberg N, Fortin P, & Galea S (2006). Community reentry: perceptions of people with substance use problems returning home from New York City jails. Journal of Urban Health-Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 83(3), 372–381. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9047-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang EA, Hong CS, Samuels L, Shavit S, Sanders R, & Kushel M (2010). Transitions clinic: creating a community-based model of health care for recently released California prisoners. Public Health Rep, 125(2), 171–177. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang EA, Hong CS, Shavit S, Sanders R, Kessell E, & Kushel MB (2012). Engaging individuals recently released from prison into primary care: a randomized trial. American Journal of Public Health, 102(9), e22–e29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang EA, Zhu GA, Evans L, Carroll-Scott A, Desai R, & Fiellin LE (2013). A pilot study examining food insecurity and HIV risk behaviors among individuals recently released from prison. AIDS Education and Prevention, 25(2), 112–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang KH, Marenco L, Madera JE, Aminawung JA, Wang EA, & Cheung KH (2017). Using a community-engaged health informatics approach to develop a web analytics research platform for sharing data with community stakeholders. In AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings (Vol. 2017, p. 1715). American Medical Informatics Association. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AR, Nunes EV, Bisaga A, Levin FR, & Olfson M (2018). Development of a Cascade of Care for responding to the opioid epidemic. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkelman TNA, Chang VW, & Binswanger IA (2018). Health, Polysubstance Use, and Criminal Justice Involvement Among Adults With Varying Levels of Opioid Use. JAMA Netw Open, 1(3), e180558. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohl DA, Scheyett A, Golin CE, White B, Matuszewski J, Bowling M, … Kaplan A (2011). Intensive case management before and after prison release is no more effective than comprehensive pre-release discharge planning in linking HIV-infected prisoners to care: a randomized trial. AIDS and Behavior, 15(2), 356–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]