Abstract

Although tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) is a known major inflammatory mediator in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and has various effects on intestinal epithelial cell (IEC) homeostasis, the changes in IECs in the early inflammatory state induced during short-time treatment (24 h) with TNF-α remain unclear. In this study, we investigated TNF-α-induced alterations in IECs in the early inflammatory state using mouse jejunal organoids (enteroids). Of the inflammatory cytokines, i.e., TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-17, only TNF-α markedly increased the mRNA level of macrophage inflammatory protein 2 (MIP-2; the mouse homologue of interleukin-8), which is induced in the early stages of inflammation. TNF-α stimulation (3 h and 6 h) decreased the mRNA level of the stem cell markers leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein-coupled receptor 5 (Lgr5) and polycomb group ring finger 4 and the progenitor cell marker prominin-1, which is also known as CD133. In addition, TNF-α treatment (24 h) decreased the number of Lgr5-positive cells and enteroid proliferation. TNF-α stimulation at 3 h and 6 h also decreased the mRNA level of chromogranin A and mucin 2, which are respective markers of enteroendocrine and goblet cells. Moreover, enteroids treated with TNF-α (24 h) not only decreased the integrity of tight junctions and cytoskeletal components but also increased intercellular permeability in an influx test with fluorescent dextran, indicating disrupted intestinal barrier function. Taken together, our findings indicate that short-time treatment with TNF-α promotes the inflammatory response and decreases intestinal stem cell activity and barrier function.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10616-021-00487-y.

Keywords: Enteroids, TNF-α, Inflammation, Stem cells, Proliferation, Barrier function

Introduction

Intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) are inherently exposed to a variety of external stresses, such as food-derived stimulating substances, environmental chemicals, and enterobacteria. Excessive exposure to these stresses induces inflammation in IECs, leading to epithelial cell damage and intestinal dysfunction (Shimizu 2017). Typical intestinal inflammation includes inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease (CD). In recent years, the number of patients with IBD has increased, but no fundamental treatment for the disease has been established.

The pro-inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) has been proposed as a mediator of inflammation in IBD, and studies have reported that it is elevated in the stool, mucous membranes, and blood of patients with IBD (Braegger et al. 1992; Breese et al. 1994; MacDonald et al. 1990; Murch et al. 1991). Several studies have also reported that TNF-α has various effects on IECs. Iwashita et al. (2003) reported that TNF-α increases mRNA expression of mucin 2 (MUC2) in HT29 cells and also decreases the expression of tight junction proteins specifically claudin-1, occludin, and zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) and induces cytoskeletal F-actin rearrangement in Caco-2 cells (Watari et al. 2017; Ye and Sun 2017). However, the intestinal epithelial cell lines used in these previous studies are composed of enterocyte monolayers; thus, they are different from the in situ intestinal cell functions of proliferation and differentiation, making it difficult to examine the behavior of IECs as a whole.

In contrast, intestinal organoids (enteroids) are three-dimensional (3D) structures that are composed of all differentiated cell types of the intestinal epithelium and intestinal stem cells (Sugimoto and Sato 2017). Therefore, this culture method has been widely used to analyze stem cell behavior and gene function and create new disease models. Furthermore, this culture system has revealed that TNF-α treatment (10 ng/mL for 5 days and 30 ng/mL for 96 h) increases stem cell activity (Bradford et al. 2017; Onozato et al. 2020). Schreurs et al. (2019) reported that TNF-α treatment (0.2 ng/mL for 12 days) increases the number of organoids in fetal intestinal epithelium-derived organoids, whereas TNF-α treatment at two different concentrations (20 and 200 ng/mL for 12 days) reduces the number of developing organoids and proliferation. In another study, TNF-α treatment (30 ng/mL for 96 h) destroyed the structure of tight junctions in human intestinal organoids (Onozato et al. 2020). Although some such reports have investigated the effects of long-time treatment with TNF-α on IECs and on tight junctions in enteroids, the direct effect of short-time stimulation (24 h) with TNF-α on enteroids in the early stages of inflammation remains unclear. Characterization of IECs and tight junctions in the early stage of inflammation would lead to the elucidation of ways to inhibit the progression of severe chronic inflammation such as IBD.

Therefore, we investigated the effect of early inflammation induced by short-time treatment (24 h) with TNF-α on stem cells and intestinal barrier function using organoid culture systems in this study. Our findings improve the basic understanding of how early inflammation induced by short-time stimulation with TNF-α affects IECs and intestinal integrity.

Materials and methods

Animals

Wild-type C57BL/6J mice were obtained from CLEA Japan, Inc. (Tokyo, Japan), and leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein-coupled receptor 5 (Lgr5)-enhanced green fluorescence protein (EGFP)-internal ribosome entry site (IRES)-creERT2 (Lgr5-EGFP) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Mice were housed in standard plastic cages in an animal room maintained at 23–25 °C and 50–56% humidity under a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle (lights on 8:00–20:00) with ad libitum access to tap water and standard laboratory rodent feed (Oriental Yeast Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines for the maintenance and handling of experimental animals established by the Tokyo University of Agriculture Ethics Committee (Approval No: No. 2020037).

Enteroid culture

Enteroids were isolated from fresh jejunal crypts obtained from wild-type and Lgr5-EGFP mice as previously described (Hanyu et al. 2020). In brief, the jejunum was collected from animals euthanized by cervical dislocation, washed with ice-cold Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) without Ca2+ and Mg2+, and cut vertically. The villi were scraped with a scalpel in a dish containing ice-cold DPBS with the luminal side facing up. The tissue was minced, agitated in 5 mL of 2.5 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)-3Na/DPBS for 30 min at 4 °C, placed in an ice-cold dissociation buffer consisting of 43.3 mM sucrose (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan) and 54.9 mM d-sorbitol (Nacalai Tesque, Inc., Kyoto, Japan) in DPBS, and shaken by hand for 60 to 90 s to dissociate the individual crypts. The crypt suspension was then filtered using a 70 μm cell strainer (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY, USA) and centrifuged at 400×g for 4 min at 4 °C. After removing the supernatant, the crypts were suspended in 60% Matrigel® (Corning Incorporated). The crypts suspended in 60% Matrigel® were added to 24-well plates (Nippon Gene Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at 200 crypts (40 μL) per well. After Matrigel® polymerization at 37 °C for 10 min, 400 μL of the enteroid culture medium consisting of advanced Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium/Ham’s F-12 (DMEM/F-12) (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 1 × B27 supplement (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.), 1 × penicillin/streptomycin, 10 mM 2-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl) piperazin-1-yl] ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 2 mM l-alanyl-l-glutamine (all three reagents are from Nacalai Tesque, Inc.), 10% R-spondin conditioned medium (CM) (kindly supplied by Dr. Eitaro Aihara, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine), 5% Noggin CM (kindly supplied by Dr. Hans Clevers, Utrecht University), 1 mM N-acetyl-l-cysteine (Sigma-Aldrich, Co., St. Louis, MO, USA), and 50 ng/mL recombinant murine epidermal growth factor (EGF; Funakoshi Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was added to the wells. The medium was replaced every 2–3 days. For passage, enteroids from wild-type mice were collected in ice-cold DPBS, mechanically disrupted by passage through a syringe with a 27 G needle (Terumo Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), and subsequently transferred to fresh 60% Matrigel®. The enteroids were passaged every 3–4 days. Enteroids from Lgr5-EGFP mice were freshly prepared before each experiment because fluorescence intensity gradually diminishes with repeated passage.

Quantification of target gene expression

The enteroids from wild-type mice were passaged and cultured with enteroid culture medium in 24-well culture plates until Day 3, at which point 400 μL of the enteroid culture medium containing recombinant murine TNF-α (0, 15, 30, and 60 ng/mL) (Funakoshi Co., Ltd.), interleukin (IL)-1β (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation), IL-6 (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation), or IL-17 (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) (each 15 ng/mL) were added. After 0, 1, 3, 6, or 24 h, total RNA was isolated from the enteroids using ISOGEN II (Nippon Gene Co., Ltd.). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using a PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Perfect Real Time) (Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed using THUNDERBIRD™ SYBR® qPCR mix (Toyobo Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) and the primer sets listed in Online Resource 1 in Supplementary Information with the following thermocycle protocol: 1 min at 95 °C followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 60 °C, and 1 min at 72 °C, as previously described (Saito et al. 2017).

Measurement of macrophage inflammatory protein 2 (MIP-2) secretion by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Enteroids from wild-type mice were passaged and cultured with enteroid culture medium in 96-well culture plates until Day 3, at which point 100 μL of the enteroid culture medium containing recombinant murine TNF-α (15 ng/mL) (Funakoshi Co., Ltd.) were added. The supernatants were collected after incubation for 0, 1, 3, 6, 12, or 24 h and the protein level of MIP-2 was analyzed using a Mouse MIP2 ELISA kit (Cat #ab204517; Abcam PLC, Cambridge, UK) according to the manufacturers’ protocols.

Monitoring of EGFP signals from Lgr5-positive cells

Enteroids from Lgr5-EGFP mice were cultured in 24-well cell culture plates. On Day 3, they resuspended in 60% Matrigel® were transferred to 35 mm dishes (AGC Techno Glass Co., Ltd., Shizuoka, Japan) at approximately 30 organoids (30 μL) per dish and cultured in 1.5 mL of the enteroid culture medium with or without TNF-α (15, 30, and 60 ng/mL) for 24 h at 37 °C under 5% CO2. During the culture period, changes in EGFP signals from Lgr5-positive cells were monitored using a FLUOVIEW FV10i confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The number of Lgr5-positive cells was measured using ImageJ 1.52 k from the National Institutes of Health (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

5-Ethynyl-2-deoxyuridine (EdU) assay

For EdU assay, passaged enteroids were cultured in 24-well cell culture plates until Day 3 and were then suspended in 60% Matrigel® before being transferred to Nunc™ Lab-Tek™ II 8-well glass bottom chambers (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) at approximately 20 organoids (5 μL) per well. After 10-min polymerization at 37 °C, the enteroids were cultured in 200 μL of the enteroid culture medium with or without TNF-α (15, 30, and 60 ng/mL). After 24 h, enteroids were incubated in the enteroid culture medium containing 10 μM EdU solution for 3 h, followed by incubation in enteroid culture medium with 10 μg/mL of Hoechst 33342 (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) for 30 min prior to fixation with 4% cold paraformaldehyde (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.)/PBS for 15 min at room temperature. The enteroids were stained using a Click-iT® EdU Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Thereafter, the enteroids were observed under a confocal laser scanning microscope (FLUOVIEW FV10i; Olympus Corporation). The proportion of EdU-positive cells was calculated as the number of red-stained (proliferating) cells relative to the total number of nuclei (blue).

Immunofluorescence staining and actin/phalloidin staining

Similar to the EdU assay, enteroids were cultured and treated with TNF-α. After 24 h, the enteroids were fixed in 200 μL of 4% cold paraformaldehyde/PBS for 30 min at room temperature, washed three times for 20 min with 200 μL PBS, and blocked in 200 μL blocking buffer (PBS containing 5% donkey serum and 0.1% Triton X-100) for 1 h at room temperature before incubating with 200 μL anti-Lyz (1:400, kindly supplied by Dr. Tokiyoshi Ayabe, Hokkaido University), anti-ChgA (1:400; Cat #ab15160; Abcam PLC), anti-DCLK1 (1:400; Cat #ab31704; Abcam PLC), anti-ZO-1 (1:100; Cat #33-9100; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.), anti-claudin 2 (Cldn2) (1:250; Cat #351-6100; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.), or anti-occludin (Ocln) (1:250; Cat #33-1500; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) antibody solutions at 4 °C overnight. After three 30-min washes with 200 μL of 0.1% Triton X-100/PBS, the samples were incubated with 200 μL of Alexa Fluor® 488, 555, or 647 (1:1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) secondary antibodies at 4 °C overnight under darkness. F-actin was stained with 200 μL of Phalloidin Alexa Fluor® 555 (1:40; Cat #A34055; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) for 20 min at room temperature. Nuclei were counterstained with 200 μL of 10 μg/mL Hoechst 33342 (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) for 30 min at room temperature. After two washes with 200 μL of PBS, the enteroids were observed using a FLUOVIEW FV10i confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus Corporation). The proportions of Lyz-, ChgA-, and DCLK1-positive cells were calculated as the number of green-stained cells (positive cells) relative to the total number of nuclei (blue). To evaluate changes of tight junction and actin integrity, a five-point enteroid integrity scoring system was used as follows: normal condition, 5; single point loss, 4; loss of multiple points, 3; morphological alteration, 2; and disappearance, 1.

Assessment of intestinal barrier function

To perform our fluorescent dextran influx experiment, passaged enteroids were cultured in 24-well cell culture plates until Day 3 and then suspended in 60% Matrigel®. The enteroids were transferred to 35 mm dishes (AGC Techno Glass Co., Ltd.) at approximately 30 organoids (30 μL) per dish and cultured in 1.5 mL of the enteroid culture medium with or without TNF-α (15, 30, and 60 ng/mL) and with 10 μM fluorescent dextran [Alexa Fluor™ 647; molecular weight (MW) 10,000; Cat #D22914; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.] for 24 h at 37 °C under 5% CO2. During enteroid culture, fluorescent dextran permeability was monitored using a confocal laser scanning microscope (FLUOVIEW FV10i; Olympus Corporation). The fluorescence intensity inside enteroids at 24 h was measured using ImageJ 1.52 k (NIH).

Statistics

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error (SE) or proportion (%). Statistical differences were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test or Dunnett’s T3 test. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). All differences with p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

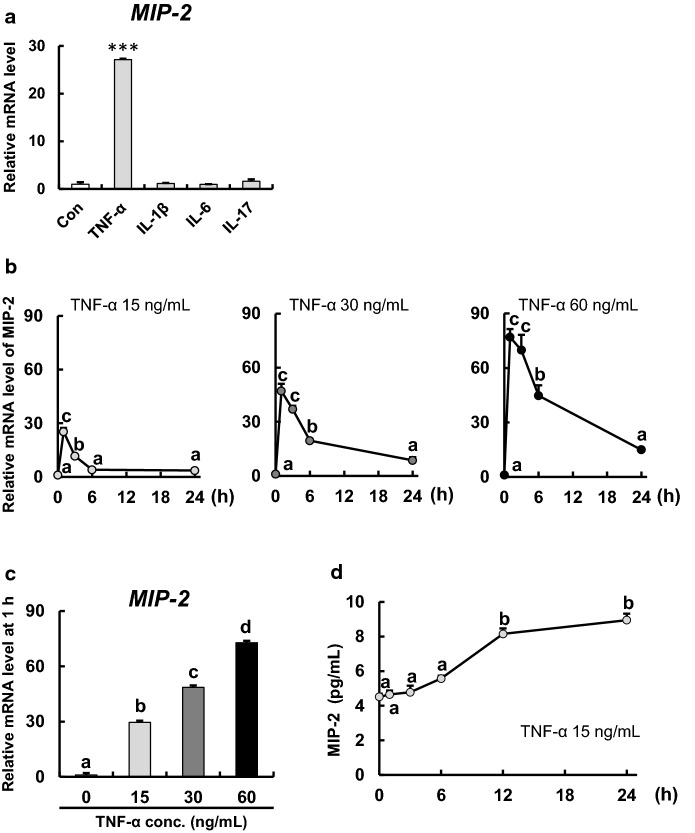

TNF-α stimulation significantly increases the gene expression and secretion of MIP-2

We examined gene expression of MIP-2, a known trigger for inflammatory response, in enteroids after 1 h of stimulation with representative pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-17) at a common concentration of 15 ng/mL. Of these inflammatory cytokines, only TNF-α stimulation markedly increased the level of MIP-2 mRNA (Fig. 1a). MIP-2 mRNA levels peaked at 1 h for all TNF-α concentrations and then gradually decreased with time (Fig. 1b). TNF-α also increased MIP-2 mRNA levels in a dose-dependent manner at 1 h of stimulation (Fig. 1c). Furthermore, TNF-α (15 ng/mL) significantly increased MIP-2 secretion after 12 and 24 h of stimulation (Fig. 1d).

Fig. 1.

TNF-α markedly increases the mRNA level of MIP-2 in enteroids. a Effect of pro-inflammatory cytokines on MIP-2 expression in enteroids. Enteroids were cultured in enteroid culture medium with or without TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-17 (15 ng/mL) for 1 h. The expression levels of MIP-2 were measured by qPCR and are relative to those of beta-2 microglobulin (B2m). The bar represents mean ± SE (n = 3). Asterisks (***) indicate a significant difference (p < 0.001) as determined by Dunnett’s T3 test. b Time course of MIP-2 expression in enteroids after stimulation with various concentrations of TNF-α. Enteroids were cultured in enteroid culture medium with TNF-α (15, 30, and 60 ng/mL) for 0–24 h. Expression levels of MIP-2 were measured by qPCR and are relative to those of B2m. The data represents mean ± SE (n = 3). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05). c MIP-2 expression in enteroids at 1 h after TNF-α stimulation (0–60 ng/mL). Data were

taken from b. The bar represents mean ± SE (n = 3). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05). d Time course of MIP-2 level secreted by enteroids after stimulation of 15 ng/mL TNF-α. Enteroids were cultured in enteroid culture medium with TNF-α (15 ng/mL) for 0–24 h. MIP-2 secretion was measured using ELISA. The data represents mean ± SE (n = 3). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05)

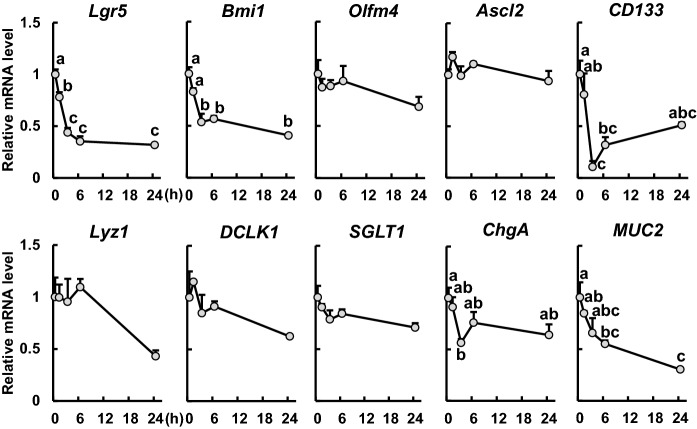

TNF-α stimulation alters expression of several IEC markers

TNF-α stimulation (15 ng/mL) significantly reduced gene expression of the stem cell marker Lgr5 in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 2). For the other stem cell markers, we found that the mRNA level of Bmi1 was significantly reduced after 3 h of TNF-α stimulation, but not for Olfm4 and Ascl2. Moreover, TNF-α stimulation significantly reduced the mRNA level of CD133, a transit-amplifying (TA) cell marker, at 3 and 6 h. In the context of differentiated cell lineages, no changes were observed in the expression of Lyz1, DCLK1, and SGLT1, which are respective markers of Paneth cells, tuft cells, and absorptive epithelial cells. However, we found that the gene expression level of ChgA, an enteroendocrine cell marker, was significantly decreased at 3 h and that the level of MUC2, a goblet cell marker, was markedly decreased at 6 and 24 h, after TNF-α stimulation.

Fig. 2.

Effects of TNF-α on intestinal epithelial cell markers in enteroids. Enteroids were cultured in enteroid culture medium containing TNF-α (15 ng/mL) for 0, 1, 3, 6, and 24 h. The mRNA expression levels of the markers Lgr5, Bmi1, Olfm4, Ascl2 (stem cells), CD133 (TA cells), Lyz1 (Paneth cells), DCLK1 (tuft cells), SGLT1 (absorptive epithelial cells), ChgA (enteroendocrine cells), and MUC2 (goblet cells) were measured using qPCR and normalized to those of B2m. The data represents the mean ± SE (n = 3). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05)

TNF-α stimulation decreases the number of intestinal stem cells and the proliferative response of enteroids

A 24-h time-lapse live imaging of enteroids generated from Lgr5-EGFP mice showed that TNF-α stimulation (15, 30, and 60 ng/mL) reduced the number of Lgr5-positive cells (Fig. 3a) and also significantly decreased the ratio of Lgr5-positive stem cells (Fig. 3c). Based on EdU assay, we found that TNF-α treatment dose-dependently reduced the proliferative response of enteroids (Fig. 3b), and furthermore, TNF-α treatment at 30 and 60 ng/mL significantly decreased the ratio of EdU-positive cells (Fig. 3d).

Fig. 3.

Effects of TNF-α on Lgr5-positive cells and cell proliferation. a Confocal images of Lgr5-EGFP enteroids treated with TNF-α (0, 15, 30, and 60 ng/mL) for 24 h. Changes in EGFP signal from Lgr5-positive cells were monitored using a confocal laser scanning microscope. Lgr5-positive cells are shown in green. Scale bar: 20 μm. b Proliferative response of enteroids treated with TNF-α. Enteroids were cultured in enteroid culture medium with or without TNF-α (15, 30, and 60 ng/mL) for 24 h. Proliferating cells and total cell nuclei were detected using EdU (red) and Hoechst (blue), respectively. Scale bar: 20 μm. c The ratio of Lgr5-positive cells in enteroids at 24 h-to-0 h after TNF-α stimulation. The number of Lgr5-positive cells was measured using ImageJ. The bar represents the mean ± SE (n = 10–15). d Proportion of EdU-positive cells in enteroids treated with TNF-α. The number of proliferating cells (red) and total number of nuclei (blue) were counted using ImageJ. The bar represents the mean ± SE (n = 10). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05). (Color figure online)

TNF-α stimulation does not affect secretory cells

Figure 4 shows the immunofluorescence staining of Paneth, enteroendocrine, and tuft cells in enteroids after 24 h of TNF-α stimulation (15, 30, and 60 ng/mL). We found that TNF-α stimulation at these concentrations had no effect on Lyz-positive cells (Paneth cells) (Fig. 4a), ChgA-positive cells (enteroendocrine cells) (Fig. 4b), and DCLK1-positive cells (tuft cells) (Fig. 4c). In addition, TNF-α treatment did not change the ratio of Paneth (Fig. 4d), enteroendocrine (Fig. 4e), and tuft (Fig. 4f) cells in enteroids.

Fig. 4.

Effects of TNF-α on differentiated cell markers in enteroids. a–c Immunofluorescence staining of Lyz (a Paneth cell marker), ChgA (an enteroendocrine cell marker), and DCLK1 (a tuft cell marker) in enteroids cultured with or without TNF-α (15, 30, and 60 ng/mL) for 24 h. Paneth, enteroendocrine, and tuft cells are shown in green and nuclei in blue. Scale bar: 20 μm. d–f The ratio of Lyz-, ChgA-, and DCLK1-positive cells in enteroids treated with TNF-α. The number of target cells (green) and total number of cell nuclei (blue) were counted using ImageJ. The bar represents the mean ± SE (n = 10–18). (Color figure online)

TNF-α stimulation alters intestinal epithelial integrity

Figure 5a–d shows the change of ZO-1, Cldn-2, Ocln, and F-actin, respectively, after 24 h of TNF-α stimulation at 15, 30, and 60 ng/mL. Based on our integrity score evaluation (Fig. 5e), we found that TNF-α stimulation significantly reduced the integrity of assembled structures of tight junction-associated proteins and F-actin (Fig. 5f–i). An influx test using a fluorescent dextran (MW: 10 kDa) showed that 24 h of TNF-α treatment increased IEC permeability (Fig. 6a). In addition, the fluorescence intensity ratio was significantly increased after TNF-α treatment at these concentrations (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 5.

Effects of TNF-α on tight junction-associated proteins and F-actin in enteroids. a–d Immunofluorescence staining of ZO-1 (green), Cldn2 (red), and Ocln (yellow) and actin/phalloidin staining (pink) in enteroids cultured with or without TNF-α (15, 30, and 60 ng/mL) for 24 h. Nuclei are shown in blue. Scale bar: 20 μm. e Enteroid barrier integrity scoring system. Scale bar: 20 μm. f–i Integrity scores of enteroids cultured with or without TNF-α (15, 30, and 60 ng/mL). A five-point enteroid integrity scoring system was used as follows: normal condition, 5; single point loss, 4; loss of multiple points, 3; morphological alteration, 2; and disappearance, 1. The bar represents the mean ± SE (n = 16–28). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05). (Color figure online)

Fig. 6.

Effects of TNF-α on intestinal barrier function in enteroids. a Representative confocal images of enteroids treated with 10 μM of fluorescent dextran (MW 10,000) (blue) and TNF-α (0, 15, 30, and 60 ng/mL) for 24 h. Scale bar: 20 μm. b Fluorescence intensity ratio inside enteroids at 24 h after TNF-α stimulation. The bar represents the mean ± SE (n = 10). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05)

Discussion

In the early phase of the inflammatory response, IECs secrete the chemokine MIP-2, which is the mouse homologue of IL-8, that triggers an inflammatory response. Zhao et al. (2008) showed that TNF-α treatment (50 ng/mL for 1 h) of Caco-2 cells markedly increased IL-8 gene expression and Satsu et al. (2009) demonstrated that TNF-α treatment (100 ng/mL for 24 h) of Caco-2 cells also significantly increased IL-8 secretion. Based on these previous studies, the experimental conditions of the current study were planned assuming that the initial stage of the inflammatory response was within 24 h after TNF-α stimulation. Since a study (Grabinger et al. 2014) using an organoid culture system have expressed a dose-dependent increase in the ratio of cell death when stimulated with TNF-α (0, 10, 30, and 100 ng/mL for 24 h), we set 30 ng/mL as a medium level, half that amount, 15 ng/mL, twice that amount, and 60 ng/mL.

To determine whether the increase in gene expression and secretion of IL-8 are specific to TNF-α, we measured MIP-2 mRNA levels in enteroids after stimulation with TNF-α and other pro-inflammatory cytokines and found that only TNF-α stimulation (15 ng/mL for 1 h) markedly increased gene expression of MIP-2 for a short period of time (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, mRNA expression of MIP-2 increased in a dose-dependent manner after TNF-α stimulation (15, 30, and 60 ng/mL for 1 h) (Fig. 1c), reaching a peak at 1 h post-stimulation, and then gradually decreased in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 1b). An increase in MIP-2 secretion was also observed after 12 and 24 h of TNF-α stimulation (15 ng/mL) (Fig. 1d). Additionally, the mRNA expression of other pro-inflammatory cytokines, TNF-α and monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1), increased after TNF-α stimulation (15–60 ng/mL and 30–60 ng/mL, respectively) (Online Resource 2). These results indicate that TNF-α stimulations induced the inflammatory response in enteroids within 24 h. Based on these findings, we focused on the effect of TNF-α on IECs under experimental conditions when exposed to 15, 30, and 60 ng/mL of TNF-α for up to 24 h.

To clarify the effects of TNF-α-induced inflammatory responses on IECs, we then examined the effects on intestinal stem cells, which are the original source of all IECs. TNF-α treatment (15 ng/mL) significantly reduced the mRNA level of the stem cell marker Lgr5 (Fig. 2) and the ratio of Lgr5-EGFP positive cells (Fig. 3a and c) and reduced mRNA levels of Bmi1 and CD133, which are markers of stem cells and progenitor cells, respectively (Fig. 2). Furthermore, TNF-α stimulation (15 ng/mL for 24 h) significantly decreased the number of EdU-positive cells exhibiting high proliferative activity (Fig. 3b and d). These results suggest that TNF-α treatment reduces stem cell activity. Hou et al. (2018) reported that TNF-α stimulation (60 ng/mL for 24 h) decreases Lgr5 expression level and the number of EdU-positive cells in enteroids. However, our present study has shown that even lower concentrations of TNF-α (15 and 30 ng/mL for 24 h) inhibit stem cell activity and proliferation in enteroids. After Lgr5-positive cells are damaged, progeny production by Bmi1-positive cells is increased, indicating that Bmi1-positive stem cells compensate for the loss of Lgr5-positive cells (Tian et al. 2011). Furthermore, Lgr5-positive stem cells and Bmi1-positive cells can be replenished when each is depleted (Takeda et al. 2011). However, since mRNA levels of both Lgr5 and Bmi1 and the ratio of Lgr5-EGFP positive cells were significantly decreased in the present study, our results suggest that damaged Lgr5-positive cells were not regenerated when stimulated with TNF-α within 24 h, thereby leading to impairing the function of stem cell maintenance and proliferation. Wnt/β-catenin signaling is a known signaling pathway involved in cell proliferation, and TNF-α induces the release of Dickkopf-related protein 1 (DKK-1), a Wnt/β-catenin signaling antagonist, in various cells (Diarra et al. 2007; González-Sancho et al. 2005; Niida et al. 2004; Rossini et al. 2013). Plasma levels of DKK-1 and DKK-1 mRNA expression in colonic mucosa of patients with CD were significantly higher than in healthy controls, whereas β-catenin expression was lower in patients with CD than in controls (Kim and Choe 2019). Therefore, it is possible that TNF-α stimulation increases DKK-1 expression and inhibits Wnt/β-catenin signaling, resulting in the observed decrease in cell proliferative activity. Although the short-term TNF-α stimulation (15 ng/mL for 24 h) reduced the stem cell activity (Fig. 2 and 3), long-term TNF-α stimulation (10 ng/mL for 5 days and 30 ng/mL for 96 h) significantly increased the mRNA levels of Ascl2 and Olfm4, respectively (Bradford et al. 2017; Onozato et al. 2020). Thus, the discrepancy in these results may be attributed to the duration of exposure to TNF-α stimulus because the concentrations used are similar. Furthermore, intestinal organoids derived from CD patients (CD organoids) have more stem cells because of high organoid reformation efficiency compared with those derived from non-IBD controls (Suzuki et al. 2018). The increased number of stem cells in CD organoids may contribute to the regeneration of damaged intestinal mucosa. Therefore, during early inflammation, TNF-α damages stem cells and reduce their activity, but if the inflammatory state lasts for a long time, the recovery mechanism for tissue repair kicks in, and stem cell activities increase. The suppressed stem cell activity observed in this study may be transient.

In terms of differentiated cells, no changes were observed in the mRNA levels of Lyz1, DCLK1, and SGLT1, which are respective markers of Paneth cells, tuft cells, and absorptive epithelial cells (Fig. 2). Fluorescence immunostaining also showed that our different TNF-α treatments did not change the number of Paneth or tuft cells (Fig. 4a, c, d, and f). These results were consistent with the findings of Joans et al. (2019) that showed that TNF-α stimulation did not alter the number of Paneth cells in the small intestine nor the number of enteroids derived from the mid-small intestine. Concerning absorptive epithelial cells, Omonjio et al. (2019) reported that lipopolysaccharide stimulation (10 μg/mL for 4 h) increased IL-8 secretion and TNF-α mRNA level, and decreased SGLT1 mRNA level in porcine intestinal epithelial cells IPEC-J2. Whether or not the decreased SGLT1 level is a direct effect of TNF-α is unclear. It cannot rule out the possibility that TNF-α affects absorptive epithelial cells. However, we have no appropriate antibody for SGLT1 at present. Further investigation is needed. Although mRNA expression of ChgA was significantly reduced only at 3 h of TNF-α stimulation (Fig. 2), fluorescence immunostaining showed that TNF-α treatment at any tested concentration did not alter the number of ChgA-positive cells (Fig. 4b and e). The result suggests that TNF-α does not affect enteroendocrine cells. However, we did not measure the number of ChgA-positive cells from 3 to 24 h after TNF-α stimulation. Thus, it is possible that TNF-α affects the number of enteroendocrine cells from 3 to 24 h. Regarding MUC2, 6 and 24 h of TNF-α stimulations reduced its mRNA expression (Fig. 2). In colon cancer cells, TNF-α decreases gene expression of MUC2 by activating the JNK pathway (Ahn et al. 2005). Even in small intestinal epithelial cells, TNF-α may reduce MUC2 gene expression via activation of the JNK pathway. In this study, it remains unclear whether TNF-α decreases the number of goblet cells because we do not have a good anti-MUC2 antibody for immunofluorescence staining. Further investigations on this aspect are warranted in the future.

The intestinal epithelial barrier is important to protect organs from harmful substances in the lumen, and it is mainly dependent on intercellular tight junctions (Luissint et al. 2016). Dysfunction of these tight junctions causes several chronic inflammatory diseases. Among pro-inflammatory cytokines, TNF-α is an important factor in the dysfunction of intestinal epithelial tight junctions found in inflammatory conditions (Satsu et al. 2006; Zhang et al. 2017). Therefore, we investigated whether TNF-α stimulation affects tight junction proteins and cytoskeletal components using enteroids. Tight junction proteins and F-actin, a cytoskeletal component, were evaluated for their integrity by scoring stained images from 1 (disappearance) to 5 (normal condition). We found that TNF-α treatment significantly reduced integrity of the assembled structure disrupting ZO-1, Cldn2, Ocln, and F-actin (Fig. 5a–i). Furthermore, an influx test using fluorescent dextran demonstrated that TNF-α treatment disrupts intestinal epithelial barrier function (Fig. 6a and b). These results indicate that TNF-α stimulation alters intestinal epithelial integrity and disrupts intestinal barrier function. Although the molecular mechanism was not examined in this study, a study using human intestinal organoids derived from induced pluripotent stem cells also showed that TNF-α stimulation disrupted ZO-1 and Ocln (Onozato et al. 2020). In Caco-2 cells, activation of the NF-κB pathway by TNF-α has been shown to increase intestinal tight junction permeability and decrease ZO-1 protein expression (Ma et al. 2004). In addition, downregulation of Cldn-1, Cldn-2, Cldn-4, and Ocln and activation of PI3K signaling were observed in T84 cells by stimulating with TNF-α (Fischer et al. 2013). Activation of the PI3K/Akt and NF-κB signaling pathways plays an important role in the development and progression of ulcerative colitis (Huang et al. 2011; Li et al. 2019). Ozes et al. (1999) reported that the Akt serine-threonine kinase is involved in the activation of NF-κB signaling by TNF-α and that TNF-α activates PI3K and its downstream target Akt. Taken together, even in enteroids, TNF-α is likely to activate NF-κB signaling via activation of PI3K/Akt signaling, thereby resulting in decreased expression of tight junction proteins and disrupted epithelial barrier function, as part of the inflammatory response.

These effects of TNF-α are expected to be mediated by TNF receptors (TNFR1 or TNFR2), which receptor cells on IECs express is still unclear. However, TNFR1 is ubiquitously expressed on almost all cells, whereas TNFR2 expression is restricted to certain cell types, such as neurons, oligodendrocytes, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, regulatory T cells, and monocytes (Atretkhany et al. 2020). In addition, TNFR1 may be activated upon binding with both membrane-bound and soluble TNF, whereas TNFR2 is primarily activated by membrane-bound TNF (Atretkhany et al. 2020; Gough and Myles 2020). TNFR1 is expressed in intestinal epithelial cells of the enteroids. Since TNFR1 promotes inflammation (Yang et al. 2018), the increased secretion of MIP-2 and the decreased stem cell number and barrier function in our study may be associated with inflammatory responses through TNFR1 signaling.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that TNF-α causes damage to intestinal stem cells and disrupts intestinal integrity in enteroids, leading to reduced stem cell activity and intestinal barrier function. Our study has shown for the first time that short-time treatment with TNF-α for up to 24 h reduces the maintenance and proliferation of intestinal stem cells and impairs intestinal barrier function in enteroids. Although further studies on the underlying mechanisms are required, our study using the intestinal organoid culture system will be useful in the search for anti-inflammatory substances to suppress inflammatory reactions in the preliminary stages of severe inflammation such as IBD.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to Dr. Hans Clevers (Hubrecht Institute) for the kind gift of the Noggin-secreting cell line, Dr. Eitaro Aihara (Cincinnati University) for kindly donating the R-spondin-secreting cell line, and Dr. Tokiyoshi Ayabe (Hokkaido University) for the kind gift of anti-lysozyme antibody.

Author contributions

YS, MS, KI, MT, YSK, and KKH designed the experiments. YS and HH performed the experiments. YS, MS, and KKH wrote the paper.

Funding

This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grant-in-Aid for JSPS fellows Grant Number JP18J22466.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval

Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines for the maintenance and handling of experimental animals established by the Tokyo University of Agriculture Ethics Committee (Approval No: No. 2020037).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ahn DH, Crawley SC, Hokari R, Kato S, Yang SC, Li JD, Kim YS. TNF-alpha activates MUC2 transcription via NF-kappaB but inhibits via JNK activation. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2005;15:29–40. doi: 10.1159/000083636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atretkhany KN, Gogoleva VS, Drutskaya MS, Nedospasov SA. Distinct modes of TNF signaling through its two receptors in health and disease. J Leukoc Biol. 2020;107:893–905. doi: 10.1002/JLB.2MR0120-510R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford EM, Ryu SH, Singh AP, Lee G, Goretsky T, Sinh P, Williams DB, Cloud AL, Gounaris E, Patel V, Lamping OF, Lynch EB, Moyer MP, De Plaen IG, Shealy DJ, Yang GY, Barrett TA. Epithelial TNF receptor signaling promotes mucosal repair in inflammatory bowel disease. J Immunol. 2017;199:1886–1897. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braegger CP, Nicholls S, Murch SH, Stephens S, MacDonald TT. Tumour necrosis factor alpha in stool as a marker of intestinal inflammation. Lancet. 1992;339:89–91. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90999-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breese EJ, Michie CA, Nicholls SW, Murch SH, Williams CB, Domizio P, Walker-Smith JA, MacDonald TT. Tumor necrosis factor alpha-producing cells in the intestinal mucosa of children with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:1455–1466. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90398-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diarra D, Stolina M, Polzer K, Zwerina J, Ominsky MS, Dwyer D, Korb A, Smolen J, Hoffmann M, Scheinecker C, van der Heide D, Landewe R, Lacey D, Richards WG, Schett G. Dickkopf-1 is a master regulator of joint remodeling. Nat Med. 2007;13:156–163. doi: 10.1038/nm1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer A, Gluth M, Pape UF, Wiedenmann B, Theuring F, Baumgart DC. Adalimumab prevents barrier dysfunction and antagonizes distinct effects of TNF-α on tight junction proteins and signaling pathways in intestinal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013;304:G970–G979. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00183.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Sancho JM, Aguilera O, García JM, Pendás-Franco N, Peña C, Cal S, García de Herreros A, Bonilla F, Muñoz A. The Wnt antagonist DICKKOPF-1 gene is a downstream target of beta-catenin/TCF and is downregulated in human colon cancer. Oncogene. 2005;24:1098–1103. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough P, Myles IA. Tumor necrosis factor receptors: pleiotropic signaling complexes and their differential effects. Front Immunol. 2020;11:585880. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.585880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabinger T, Luks L, Kostadinova F, Zimberlin C, Medema JP, Leist M, Brunner T. Ex vivo culture of intestinal crypt organoids as a model system for assessing cell death induction in intestinal epithelial cells and enteropathy. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1228. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanyu H, Yokoi Y, Nakamura K, Ayabe T, Tanaka K, Uno K, Miyajima K, Saito Y, Iwatsuki K, Shimizu M, Tadaishi M, Kobayashi-Hattori K. Mycotoxin deoxynivalenol has different impacts on intestinal barrier and stem cells by its route of exposure. Toxins (Basel) 2020;12:610. doi: 10.3390/toxins12100610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Q, Ye L, Liu H, Huang L, Yang Q, Turner JR, Yu Q. Lactobacillus accelerates ISCs regeneration to protect the integrity of intestinal mucosa through activation of STAT3 signaling pathway induced by LPLs secretion of IL-22. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:1657–1670. doi: 10.1038/s41418-018-0070-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang XL, Xu J, Zhang XH, Qiu BY, Peng L, Zhang M, Gan HT. PI3K/Akt signaling pathway is involved in the pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Res. 2011;60:727–734. doi: 10.1007/s00011-011-0325-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwashita J, Sato Y, Sugaya H, Takahashi N, Sasaki H, Abe T. mRNA of MUC2 is stimulated by IL-4, IL-13 or TNF-alpha through a mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in human colon cancer cells. Immunol Cell Biol. 2003;81:275–282. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2003.t01-1-01163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LG, Vaida A, Thompson LM, Ikuomola FI, Caamaño JH, Burkitt MD, Miyajima F, Williams JM, Campbell BJ, Pritchard DM, Duckworth CA. NF-κB2 signalling in enteroids modulates enterocyte responses to secreted factors from bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:896. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-2129-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MJ, Choe YH. Correlation of Dickkopf-1 with inflammation in Crohn disease. Indian Pediatr. 2019;56:929–932. doi: 10.1007/s13312-019-1649-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Sun W, Zhou X, Gong H, Chen Y, Chen D, Xiang F. Dihydroartemisinin protects against dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in mice through inhibiting the PI3K/AKT and NF-κB signaling pathways. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:1415809. doi: 10.1155/2019/1415809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luissint AC, Parkos CA, Nusrat A. Inflammation and the intestinal barrier: leukocyte-epithelial cell interactions, cell junction remodeling, and mucosal repair. Gastroenterology. 2016;151:616–632. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma TY, Iwamoto GK, Hoa NT, Akotia V, Pedram A, Boivin MA, Said HM. TNF-alpha-induced increase in intestinal epithelial tight junction permeability requires NF-kappa B activation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;286:G367–G376. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00173.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald TT, Hutchings P, Choy MY, Murch S, Cooke A. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma production measured at the single cell level in normal and inflamed human intestine. Clin Exp Immunol. 1990;81:301–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1990.tb03334.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murch SH, Lamkin VA, Savage MO, Walker-Smith JA, MacDonald TT. Serum concentrations of tumour necrosis factor alpha in childhood chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1991;32:913–917. doi: 10.1136/gut.32.8.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niida A, Hiroko T, Kasai M, Furukawa Y, Nakamura Y, Suzuki Y, Sugano S, Akiyama T. DKK1, a negative regulator of Wnt signaling, is a target of the beta-catenin/TCF pathway. Oncogene. 2004;23:8520–8526. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omonijo FA, Liu S, Hui Q, Zhang H, Lahaye L, Bodin JC, Gong J, Nyachoti M, Yang C. Thymol improves barrier function and attenuates inflammatory responses in porcine intestinal epithelial cells during lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammation. J Agric Food Chem. 2019;67:615–624. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b05480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onozato D, Akagawa T, Kida Y, Ogawa I, Hashita T, Iwao T, Matsunaga T. Application of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived intestinal organoids as a model of epithelial damage and fibrosis in inflammatory bowel disease. Biol Pharm Bull. 2020;43:1088–1095. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b20-00088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozes ON, Mayo LD, Gustin JA, Pfeffer SR, Pfeffer LM, Donner DB. NF-kappaB activation by tumour necrosis factor requires the Akt serine-threonine kinase. Nature. 1999;401:82–85. doi: 10.1038/43466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossini M, Gatti D, Adami S. Involvement of WNT/β-catenin signaling in the treatment of osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int. 2013;93:121–132. doi: 10.1007/s00223-013-9749-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito Y, Iwatsuki K, Hanyu H, Maruyama N, Aihara E, Tadaishi M, Shimizu M, Kobayashi-Hattori K. Effect of essential amino acids on enteroids: methionine deprivation suppresses proliferation and affects differentiation in enteroid stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;488:171–176. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satsu H, Ishimoto Y, Nakano T, Mochizuki T, Iwanaga T, Shimizu M. Induction by activated macrophage-like THP-1 cells of apoptotic and necrotic cell death in intestinal epithelial Caco-2 monolayers via tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:3909–3919. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satsu H, Hyun JS, Shin HS, Shimizu M. Suppressive effect of an isoflavone fraction on tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced interleukin-8 production in human intestinal epithelial Caco-2 cells. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2009;55:442–446. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.55.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreurs RRCE, Baumdick ME, Sagebiel AF, Kaufmann M, Mokry M, Klarenbeek PL, Schaltenberg N, Steinert FL, van Rijn JM, Drewniak A, The SML, Bakx R, Derikx JPM, de Vries N, Corpeleijn WE, Pals ST, Gagliani N, Friese MA, Middendorp S, Nieuwenhuis EES, Reinshagen K, Geijtenbeek TBH, van Goudoever JB, Bunders MJ. Human fetal TNF-α-cytokine-producing CD4+ effector memory T cells promote intestinal development and mediate inflammation early in life. Immunity. 2019;50:462–476.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu M. Multifunctions of dietary polyphenols in the regulation of intestinal inflammation. J Food Drug Anal. 2017;25:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto S, Sato T. Establishment of 3D intestinal organoid cultures from intestinal stem cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1612:97–105. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7021-6_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Murano T, Shimizu H, Ito G, Nakata T, Fujii S, Ishibashi F, Kawamoto A, Anzai S, Kuno R, Kuwabara K, Takahashi J, Hama M, Nagata S, Hiraguri Y, Takenaka K, Yui S, Tsuchiya K, Nakamura T, Ohtsuka K, Watanabe M, Okamoto R. Single cell analysis of Crohn's disease patient-derived small intestinal organoids reveals disease activity-dependent modification of stem cell properties. J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:1035–1047. doi: 10.1007/s00535-018-1437-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda N, Jain R, LeBoeuf MR, Wang Q, Lu MM, Epstein JA. Interconversion between intestinal stem cell populations in distinct niches. Science. 2011;334:1420–1424. doi: 10.1126/science.1213214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian H, Biehs B, Warming S, Leong KG, Rangell L, Klein OD, de Sauvage FJ. A reserve stem cell population in small intestine renders Lgr5-positive cells dispensable. Nature. 2011;478:255–259. doi: 10.1038/nature10408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watari A, Sakamoto Y, Hisaie K, Iwamoto K, Fueta M, Yagi K, Kondoh M. Rebeccamycin attenuates TNF-α-induced intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction by inhibiting myosin light chain kinase production. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;41:1924–1934. doi: 10.1159/000472367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Wang J, Brand DD, Zheng SG. Role of TNF-TNF receptor 2 signal in regulatory T cells and its therapeutic implications. Front Immunol. 2018;9:784. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye X, Sun M. AGR2 ameliorates tumor necrosis factor-α-induced epithelial barrier dysfunction via suppression of NF-κB p65-mediated MLCK/p-MLC pathway activation. Int J Mol Med. 2017;39:1206–1214. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.2928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Yan J, Xiao Y, Shen Y, Wang J, Ge W, Chen Y. Inhibition of autophagic degradation process contributes to claudin-2 expression increase and epithelial tight junction dysfunction in TNF-α treated cell monolayers. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:157. doi: 10.3390/ijms18010157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z, Satsu H, Fujisawa M, Hori M, Ishimoto Y, Totsuka M, Nambu A, Kakuta S, Ozaki H, Shimizu M. Attenuation by dietary taurine of dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in mice and of THP-1-induced damage to intestinal Caco-2 cell monolayers. Amino Acids. 2008;35:217–224. doi: 10.1007/s00726-007-0562-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.