Summary

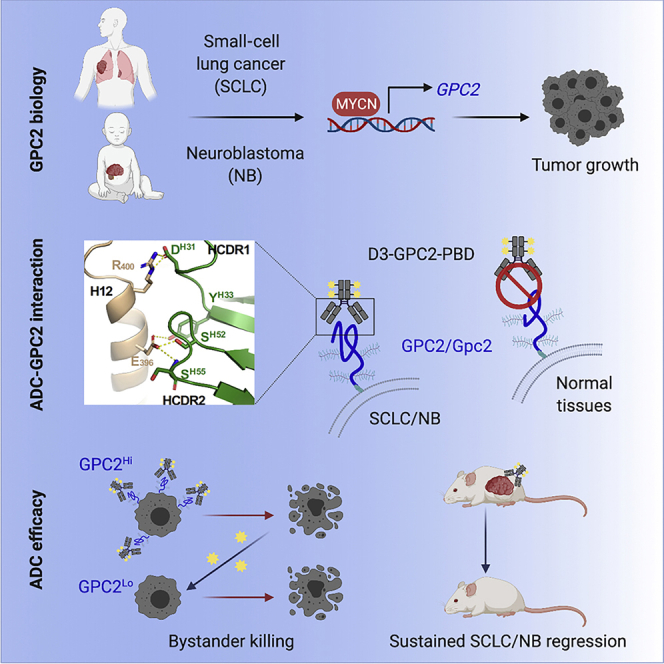

Glypican 2 (GPC2) is a MYCN-regulated, differentially expressed cell-surface oncoprotein and target for immune-based therapies in neuroblastoma. Here, we build on GPC2’s immunotherapeutic attributes by finding that it is also a highly expressed, MYCN-driven oncoprotein on small-cell lung cancers (SCLCs), with significantly enriched expression in both the SCLC and neuroblastoma stem cell compartment.By solving the crystal structure of the D3-GPC2-Fab/GPC2 complex at 3.3 Å resolution, we further illustrate that the GPC2-directed antibody-drug conjugate (ADC; D3-GPC2-PBD), that links a human GPC2 antibody (D3) to DNA-damaging pyrrolobenzodiazepine (PBD) dimers, binds a tumor-specific, conformation-dependent epitope of the core GPC2 extracellular domain. We then show that this ADC induces durable neuroblastoma and SCLC tumor regression via induction of DNA damage, apoptosis, and bystander cell killing, notably with no signs of ADC-induced in vivo toxicity. These studies provide preclinical data to support the clinical translation of ADCs targeting GPC2.

Keywords: glypican, small-cell lung cancer, neuroblastoma, antibody-drug conjugate, MYCN

Graphical abstract

Highlights

GPC2 is a MYCN transcriptionally regulated cell-surface oncoprotein on SCLCs

GPC2 is enriched in the SCLC and neuroblastoma stem cell compartment

The D3-GPC2 antibody binds a tumor-specific, GPC2 conformational epitope

The D3-GPC2-PBD ADC evokes durable neuroblastoma and SCLC tumor regression

Raman et al. report that GPC2 is a MYCN transcriptionally regulated cell-surface oncoprotein that is robustly differentially expressed on neuroblastomas and SCLCs, with enriched expression in the tumor stem cell compartment. An ADC that targets a GPC2 conformational epitope induces sustained neuroblastoma and SCLC tumor regression without any apparent toxicity.

Introduction

Despite dramatic therapy intensification, neuroblastoma remains one of the most incurable pediatric malignancies.1,2 However, neuroblastomas are a malignancy that offers unique opportunities to target with immunotherapeutic approaches as they represent a misappropriation of normal fetal nervous system development and thus continue to selectively express lineage-specific, tumor-dependent cell-surface molecules. However, despite remarkable efficacy with chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells in the pediatric leukemias,3 comparable clinical success for pediatric or adult solid tumors has not been realized to date, making it imperative to explore other immune-based therapies in these malignancies.4 Antibodies targeting the disialoganglioside GD2 have credentialed antibody-based protein therapeutics for neuroblastoma, and dinutuximab has recently become the only US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved therapy for this disease.5 Furthermore, this GD2 antibody is the cornerstone of maintenance therapy for children with an initial neuroblastoma diagnosis and has also revolutionized the treatment of relapsed disease.6 Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) similarly exploit the specificity of monoclonal antibodies and selectively and safely target potent drugs to antigen-expressing tumor tissues, largely eliminating the systemic side effects of these cytotoxic warheads.7,8 Importantly, ADCs can also induce potent bystander cytotoxicity of antigen low-expressing cells within the tumor,9, 10, 11 which is especially attractive for solid tumors that commonly have heterogeneous target molecule expression.

In an unbiased screen of the neuroblastoma surfaceome, we identified the cell-surface heparan sulfate (HS) proteoglycan signaling co-receptor glypican 2 (GPC2) to be an almost ubiquitously expressed oncoprotein on high-risk neuroblastoma tumors that is transcriptionally activated by MYCN.12 GPC2- and glypican 3 (GPC3)-bound antibodies are robustly internalized,12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 suggesting that glypicans may be particularly ideal to target with ADCs. Furthermore, given the growth dependence on glypicans and their critical role in tumor-promoting signaling pathways,12,13,15,16,19 these cell-surface molecules may be more difficult for the tumor to downregulate as a mechanism of immunotherapy evasion. Thus, we have engineered a GPC2-targeting ADC by linking a fully human GPC2 antibody (D3-GPC2-IgG1 [immunoglobulin G1]) to DNA-damaging pyrrolobenzadiazepine (PBD) dimers (D3-GPC2-PBD) that showed remarkable specificity in vitro and robust efficacy in a proof-of-concept neuroblastoma in vivo study.12 However, it remains unclear how broadly acting GPC2-targeting ADCs would be across different cancer histotypes and furthermore, what is the molecular basis of the D3-GPC2-PBD ADC’s specificity, potent efficacy, and favorable tolerability profile, all critical elements to the clinical translation of GPC2 ADCs.

We now report high levels of GPC2 across several other cancers, most notably small-cell lung cancers (SCLCs), and fully validate GPC2 as a robust immunotherapeutic target by showing enrichment of GPC2 expression in the cancer stem cell compartment. In turn, we provide a detailed molecular characterization of the D3-GPC2 antibody that explains its high specific affinity for tumor-associated GPC2 and its favorable in vivo safety profile. Finally, we demonstrate potent and sustained anti-tumor efficacy for this GPC2 ADC across a panel of genomically and clinically diverse neuroblastoma and SCLC preclinical models via induction of DNA damage, apoptosis, and robust bystander cytotoxicity.

Results

GPC2 is a MYCN transcriptionally activated cell-surface oncoprotein in SCLCs

We have previously validated high levels of GPC2 on the neural-derived pediatric cancers neuroblastoma, medulloblastoma, and retinoblastoma.12 Now to more comprehensively define the full spectrum of GPC2-expressing pediatric and adult malignancies, we queried GPC2 expression across a large number of cancers using multiple RNA-sequencing datasets, including data from the St. Jude PeCAN portal (https://pecan.stjude.cloud/home), the PedcBioPortal for Integrated Childhood Cancer Genomics (https://pedcbioportal.kidsfirstdrc.org), the R2: Genomics Analysis and Visualization Platform (http://r2.amc.nl), the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA; https://www.cancer.gov/about-nci/organization/ccg/research/structural-genomics/tcga), and the Broad Institute Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE; https://depmap.org/portal/; Figure S1A).20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 These data validated our prior findings showing that a majority of neuroblastomas, medulloblastomas, and retinoblastomas express high levels of GPC212 and also revealed appreciable GPC2 expression in a number of non-medulloblastoma pediatric brain tumors, as well as subsets of pediatric acute lymphocytic leukemias (ALLs; Figure S1B) and other pediatric solid tumors. Importantly, these data also revealed that several adult cancers have overexpression of GPC2, including SCLCs, uterine carcinosarcomas, and high-grade gliomas.

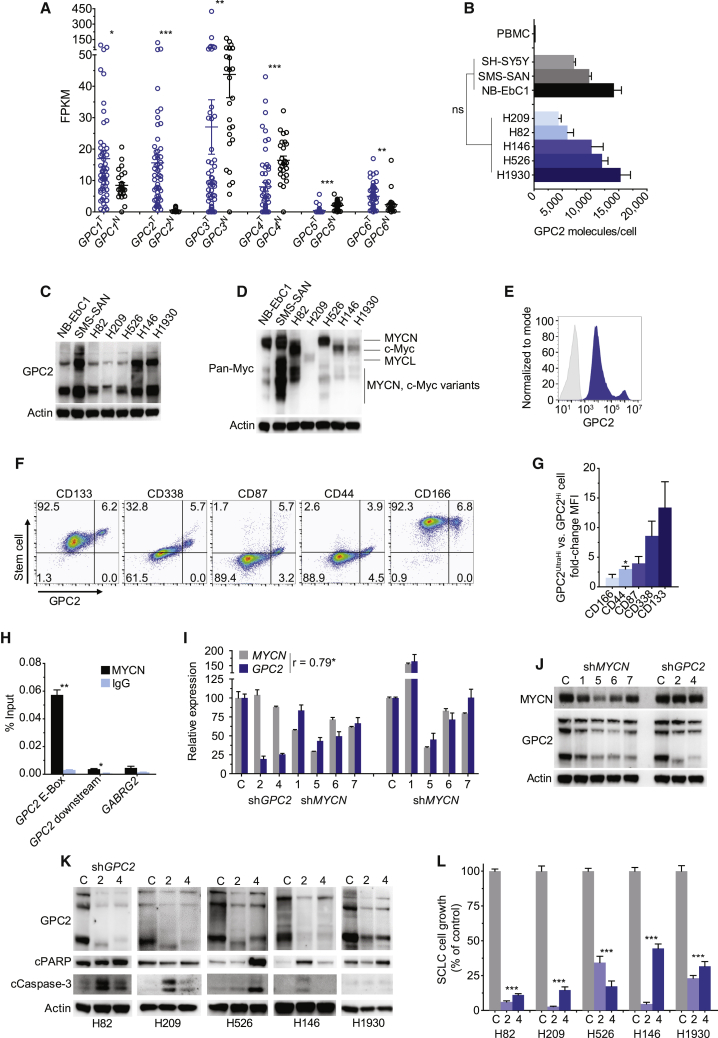

We next wanted to validate robust cell-surface GPC2 expression on SCLCs given the similarities between SCLCs and neuroblastomas, including neuroendocrine origin, common amplification/overexpression of a MYC gene family member, and continued poor outcomes despite multimodal toxic therapies.32 First, comparing GPC1–GPC6 expression in SCLCs with normal lung tissues revealed that the GPC2 tumor-normal differential expression pattern was the most significant among the glypican family and also that high levels of GPC2 were restricted to malignant lung cells (Figure 1A), similar to the GPC2 expression pattern in embryonal cancers such as retinoblastoma (Figure S1C). Next, we subjected five genomically diverse SCLC cell lines with varied GPC2 expression, genomic drivers, and MYC family expression profiles (Table S1) to GPC2-directed flow cytometry and western blot, confirming neuroblastoma-comparable GPC2 and MYC family expression (Figures 1B–1D; Figures S1D and S1E). To confirm high levels of GPC2 expression on SCLCs in vivo, we generated SCLC H526 xenografts and surprisingly found these tumors to have a bimodal GPC2 expression pattern (GPC2Hi and GPC2UltraHi cells), with GPC2UltraHi cells co-expressing higher levels of SCLC stem cell markers CD133, CD338, CD87, CD44, and CD166 (Figures 1E–1G).33, 34, 35 To assess for MYC family regulation of GPC2 in SCLCs, we next quantified MYCN binding to the canonical E-Box motif present upstream of the GPC2 transcription start site with chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) PCR in the MYCN-amplified H526 SCLC cell line, showing robust binding of MYCN to this region of the GPC2 promoter (Figure 1H). Furthermore, MYCN depletion in H526 cells resulted in concurrent GPC2 downregulation (Figures 1I and 1J). Finally, we also investigated the phenotypic consequences of depleting GPC2 in this SCLC cell line panel, which revealed robust apoptosis induction and significant growth inhibition in GPC2-depleted cells similar to what we have observed in neuroblastoma (Figures 1K and 1L).12 These data, taken together with our previous findings showing robust MYCN transcriptional activation in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma cell lines and broad GPC2 dependence in neuroblastoma,12 validate GPC2 as a MYCN-regulated protein critical to cancer cell growth.

Figure 1.

GPC2 is a MYCN-regulated oncogene in SCLC

(A) GPC1–GPC6 expression across normal lung tissue (N; n = 26) and SCLC (T; n = 31 SCLC tumors and 22 SCLC cell lines).29

(B) Plot of GPC2 molecules/cell in neuroblastoma and SCLC cell lines.

(C and D) GPC2 (C) and pan-Myc (D) western blot in neuroblastoma and SCLC cell lines.

(E and F) GPC2 histogram (E) and GPC2 versus SCLC stem cell marker (F) flow cytometry plots of the H526 xenograft.

(G) Fold-change mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of SCLC surface molecules in GPC2UltraHi versus GPC2Hi cells in the H526 xenograft.

(H) Percent input plot of MYCN ChIP PCR in the SCLC H526 cell line. GABRG2 is a non-MYCN-targeted gene.

(I and J) MYCN and GPC2 RNA quantification (left, 72 h and right, 96 h; I) and western blot (J) of H526 cells following MYCN and GPC2 depletion.

(K) Western blot of SCLC cells following GPC2 depletion.

(L) SCLC cell growth plot following GPC2 depletion.

Data in (A) represent mean ± SEM expression for each glypican. Data in (B), (G), and (L) represent mean ± SEM of 3–4, 2–4, and 2–3 independent experiments, respectively. Data in (H) and (I) represent mean ± SEM from a representative experiment done in technical triplicate with each experiment being done at least two independent times. NB-EbC1, SMS-SAN, and SH-SY5Y cells in (B)–(D) are representative neuroblastoma cells. C in (I)–(L) represents control non-targeting short hairpin RNA (shRNA); 2 and 4 in (I)–(L) represent unique GPC2-targeting shRNAs; and 1, 5, 6, and 7 in (I) and (J) represent unique MYCN-targeting shRNAs.

∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not significant. See also Figure S1.

GPC2 is significantly enriched in the neuroblastoma stem cell compartment

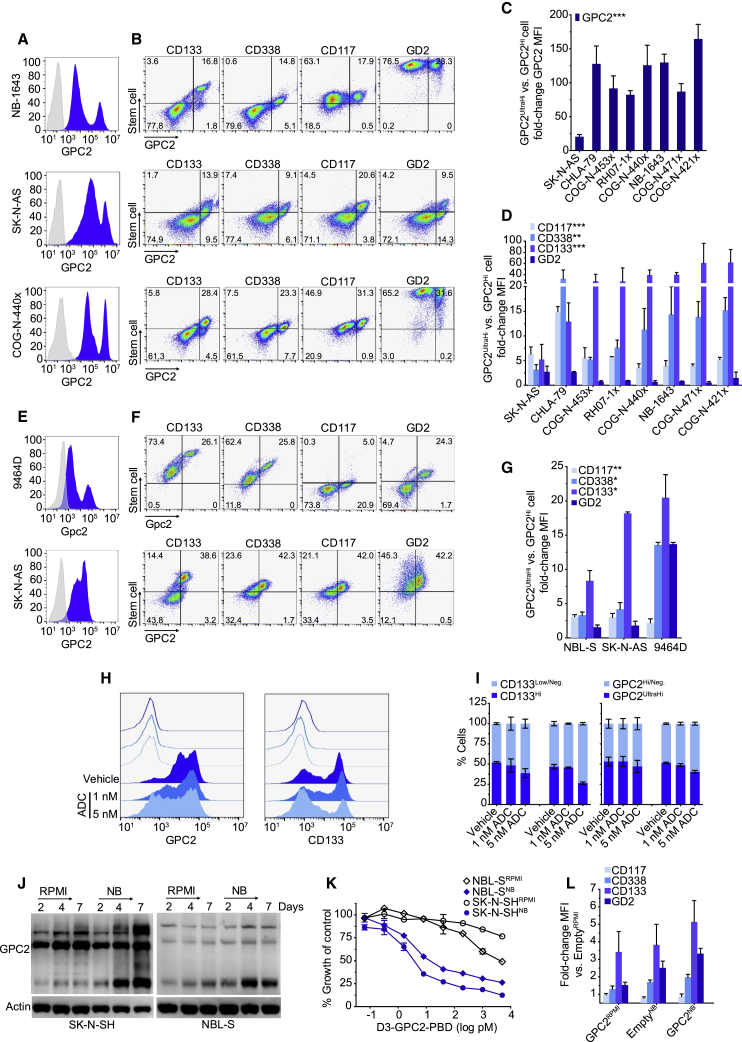

To further investigate the bimodal GPC2 expression pattern that we observed in the SCLC H526 xenograft and possible enriched GPC2 expression in the putative cancer stem cell compartment, we expanded our GPC2-directed flow cytometry studies to a panel of neuroblastoma patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) and cell line xenografts (Figures 2A and 2B; Figures S2A and S2B; Table S2). These analyses revealed a similar bimodal GPC2 expression pattern (GPC2Hi and GPC2UltraHi cell populations) in neuroblastoma in vivo models, with the GPC2UltraHi cells having a 20- to 164-fold higher GPC2 mean fluorescent intensity (MFI; Figure 2C). Co-staining this panel of neuroblastoma PDXs and xenografts with the neuroblastoma stem cell-surface markers CD133, CD338, and CD117,35, 36, 37, 38, 39 and as a control the disialoganglioside GD2, we found that the GPC2UltraHi population of cells also co-expressed significantly higher levels of stem cell molecules (Figures 2B and 2D; Figure S2B). Some human and murine neuroblastoma cell lines also showed a similar bimodal GPC2 expression pattern with GPC2UltraHi cells again co-expressing an enrichment of stem cell molecules (Figures 2E–2G). Importantly, in the relatively ADC-resistant cell line SK-N-AS, the GPC2UltraHi/CD133Hi population of cells could be preferentially eradicated with the GPC2-targeting D3-GPC2-PBD ADC, further validating their enriched GPC2 cell-surface expression (Figures 2H and 2I).

Figure 2.

Neuroblastoma stem cells have highly enriched GPC2 expression

(A and B) GPC2 histograms (A) and GPC2 versus CD133, CD338, CD117, and GD2 flow cytometry plots (B) of neuroblastoma PDXs/xenografts.

(C) Fold-change GPC2 MFI plot of GPC2UltraHi versus GPC2Hi cells in neuroblastoma PDXs/xenografts.

(D) Fold-change stem cell marker MFI plot of GPC2UltraHi versus GPC2Hi cells in neuroblastoma PDXs/xenografts.

(E and F) Gpc2/GPC2 histograms (E) and Gpc2/GPC2 versus CD133, CD338, CD117, and GD2 flow cytometry plots (F) of murine (9464D) and human (SK-N-AS) neuroblastoma cell lines.

(G) Fold-change stem cell marker MFI plot of GPC2UltraHi versus GPC2Hi cells in neuroblastoma cell lines.

(H) GPC2 (left) and CD133 (right) histograms in SK-N-AS cells after D3-GPC2-PBD ADC treatment.

(I) Quantification of CD133- and GPC2-positive SK-N-AS cells after D3-GPC2-PBD ADC treatment (left, ADC × 1; right, ADC × 2).

(J) GPC2 western blot of SK-N-SH/NBL-SRPMI/NB cells.

(K) Relative growth of SK-N-SH/NBL-SRPMI/NB cells 4 days after treatment with the D3-GPC2-PBD ADC.

(L) Fold-change MFI plot of SH-SY5Y-EmptyNB and -GPC2RPMI/NB isogenic cells.

Data in (C) and (D) are represented as mean ± SEM of PDXs/xenografts analyzed 2–3 independent times with 4 technical replicates each time for each PDX/xenograft in (C). Data in (G), (I), and (L) are represented as mean ± SEM of experiments done 2–3, 2, and 5 times, respectively. Data in (K) represent mean ± SEM from a representative experiment done in technical triplicate at least two independent times.

Neg, negative.

∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗p < 0.0001. See also Figure S2.

To further validate these findings, we compared GPC2 expression in two low-GPC2-expressing neuroblastoma cell lines (SK-N-SH and NBL-S) incubated in either RPMI-based media (10% FBS; SK-N-SH/NBL-SRPMI) or alternatively in neurobasal (NB) media with basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and epidermal growth factor (EGF) supplementation (SK-N-SH/NBL-SNB), which has been shown to facilitate growth of neural stem cells.40 Quantification of GPC2 expression in these paired cell lines showed higher levels of GPC2 expression in SK-N-SH/NBL-SNB cells (Figure 2J), which correlated with an acquired susceptibility to the D3-GPC2-PBD ADC (half-maximal inhibitory concentration [IC50] = 3.92 ± 0.03 pM for NBL-SNB and IC50 = 1.81 ± 1.33 pM for SK-N-SHNB versus IC50 > 1 nM for NBL-S/SK-N-SHRPMI; p < 0.05; Figure 2K). Also consistent with these findings, we found that stable overexpression of GPC2 in the low-GPC2-expressing neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y (SH-SY5Y-GPC2) was sufficient to induce increased co-expression of CD133, CD338, and CD117, similar to the level of co-expression of these stem cell markers observed when SH-SY5Y-Empty cells were incubated in neurobasal media (Figure 2L; Figure S2C). Finally, we also found that SH-SY5Y-GPC2 cells had a significantly higher frequency of tumor-initiating cells by limiting dilution assay (p = 4.02 × 10−53; Tables S3 and S4). Taken together, these data demonstrate highly enriched GPC2 expression in the putative neuroblastoma and SCLC stem cell compartment.

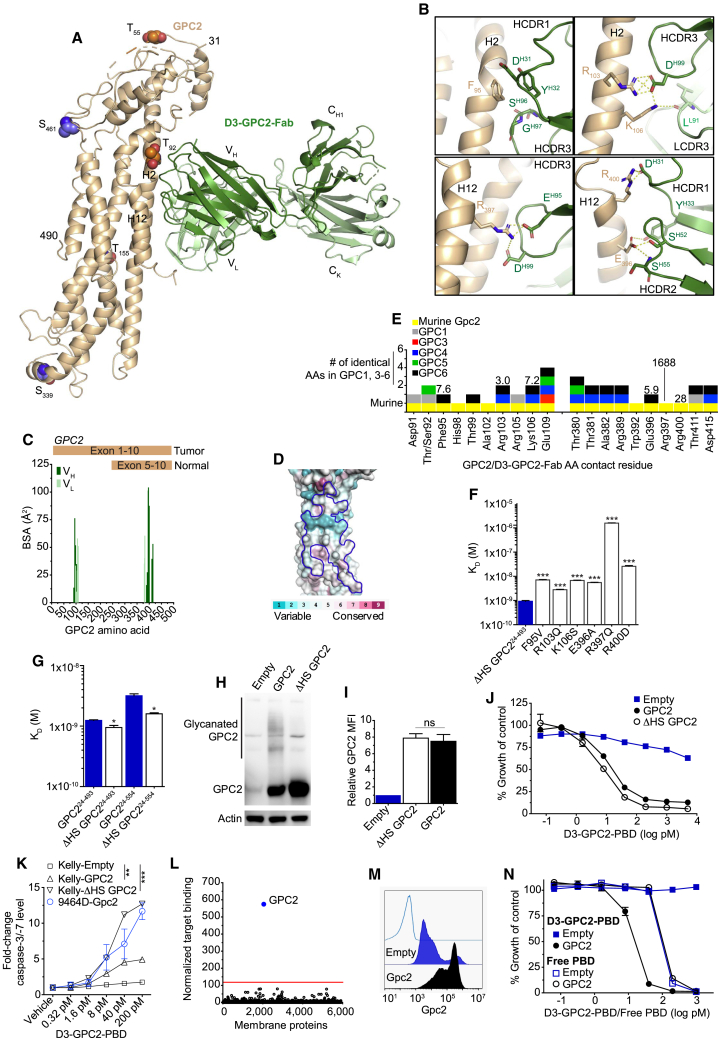

The D3-GPC2 antibody binds a core GPC2 conformational epitope

GPC2 is not only robustly differentially expressed between tumor and normal tissues but also distinct tumor and normal tissue GPC2 mRNA isoforms are present,12 making it imperative to understand where binders utilized in the development of GPC2-directed immunotherapeutics bind to the GPC2 protein. Therefore, we next solved the crystal structure of the D3-GPC2 antigen-binding fragment (D3-GPC2-Fab) in complex with ΔHS GPC224-493 (amino acids 24–493 of human GPC2 where the putative O-linked glycosylated serine residues [Ser55, Ser92, and Ser155] were replaced with threonine residues) to 3.3 Å resolution (Figure 3A; Figure S3A; Table S5). With a sequence identity of ∼40% to GPC1, the GPC2 crystal structure shows a similar core helical arrangement with an overall root-mean square deviation (RMSD) of 2.4 Å (Figure S3B). The D3-GPC2-Fab buries a 1,069 Å2 surface area on GPC2, forming several salt bridges in addition to multiple hydrophobic interactions, corroborating the high D3-GPC2-Fab binding affinity (Figure 3B; Figure S3C; Table S6). The D3-GPC2-Fab recognizes GPC2-specific residues from helices 2, 12, and 13, forming a discontinuous conformational epitope split between two sequentially distal GPC2 protein regions (Figure S3D; Table S6). GPC2 residues involved in interacting with the D3-GPC2 antibody explain the binding specificity toward the GPC2 variant expressed in neuroblastoma and other cancers, and these amino acid residues vary significantly across the glypican family, suggesting that there should be little if any binding to other glypican family members (Figures 3C–3E; Table S6). We further confirmed the specificity of the D3-GPC2-Fab toward GPC2 by mutating key GPC2 contact residues to the corresponding residues in GPC1 (Figures 3E and 3F; Figure S3E). All point mutants showed reduced affinity to the D3-GPC2-Fab (3.0- to 1,688-fold difference in dissociation constant (KD) from wild type [WT] ΔHS GPC224-493), in particular R397Q, where the affinity was decreased by over 1,000-fold.

Figure 3.

The D3-GPC2 antibody binds a conformation-specific core GPC2 epitope

(A) Crystal structure of GPC2 (left, wheat) in complex with the D3-GPC2-Fab (right, Fab heavy [dark green] and light [light green] chains). Putative sites of post-translational modifications are indicated (heparan sulfate, orange; phosphorylation, purple). Helices H2 and H12 that form part of the epitope are indicated on the GPC2 structure.

(B) Specific interactions between GPC2 (wheat) and D3-GPC2-Fab (green). Salt bridges or hydrogen bonds indicated in yellow.

(C) BSA plot for GPC2 residues interacting with D3-GPC2-Fab heavy (dark green) and light (light green) chain with tumor and normal tissue GPC2 isoforms indicated.

(D) Amino acid conservation plot across the different human glypicans (GPC1-GPC6), mapped on the GPC2 structure, calculated using the ConSurf server.41 The D3-GPC2-Fab epitope is outlined in blue.

(E) Plot of GPC2 residues interacting with D3-GPC2-Fab with conserved amino acids across murine Gpc2 and human glypican family (GPC1, 3–6) indicated. Numbers represent the fold-change in dissociation constant (KD) from the D3-GPC2-Fab/ΔHS GPC224-493 interaction when indicated amino acid is mutated.

(F and G) KD of the D3-GPC2-Fab to different GPC2 point mutants (F) and differentially glycanated GPC2 proteins (G).

(H–J) GPC2 western blot (H), D3-GPC2-IgG1 flow cytometry relative GPC2 MFIs (I), and relative cell growth after treatment with the D3-GPC2-PBD ADC (J) of isogenic Kelly-GPC2, -ΔHS GPC2, and -Empty cells.

(K) Fold-change caspase-3/-7 levels 96 h after D3-GPC2-PBD ADC treatment (p value indicated represents comparison of 200 pM ADC caspase-3/-7 levels versus Kelly-Empty cells).

(L) MPA-validated binding specificity testing of the D3-GPC2-IgG1 antibody.

(M and N) GPC2 flow cytometry histograms (M) and relative cell growth after treatment with the D3-GPC2-PBD ADC or free PBD dimer (N) of isogenic 9464D-Gpc2 cells.

Data in (F), (G), and (I) represent mean ± SEM of 3–5, 3, and 2 independent experiments, respectively. Data in (J), (K), and (N) represent mean ± SEM from a representative experiment done in technical triplicate with each experiment being done at least two independent times.

HCDR, heavy chain complementarity-determining region; LCDR, light chain complementarity-determining region; AA, amino acid. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

See also Figures S3 and S4.

Given the potential variability in the post-translational modification of GPC2 with HS moieties across neuroblastomas and other GPC2-expressing cancer histotypes (Figure 1C),12 we next sought to study the binding characteristics of the D3-GPC2-Fab to differentially glycanated recombinant GPC2 protein variants. First, mapping of the putative post-translational modification sites on the GPC2 structure shows that all except one residue are physically positioned distant from the D3-GPC2-Fab epitope (Figure 3A). The side chain of the sole GPC2 residue near the epitope (Ser/threonine 92) points away from any D3-GPC2-Fab interaction, so would not be expected to effect antibody binding (Figure S3F). Indeed, we found that ΔHS GPC224-493 and ΔHS GPC224-554 mutant variants showed only a minimal change in binding affinity to the D3-GPC2-Fab versus the fully glycanated proteins (1.3- to 2-fold difference in KD; Figure 3G). To further functionally validate these findings, we engineered 2 pairs of GPC2 isogenic lines from the low-GPC2-expressing neuroblastoma cellular models Kelly (has a heterozygous deletion of the GPC2 locus) and SH-SY5Y with and without HS chains (ΔHS GPC2). Stable lentiviral transduction induced comparable GPC2 expression, which bound to D3-GPC2-IgG1 similarly and dictated an equal response to the D3-GPC2-PBD ADC (Kelly mean IC50 = 12.9 ± 0.8 pM for GPC2 and 6.9 ± 0.6 pM for ΔHS GPC2 and SH-SY5Y mean IC50 = 17.7 ± 2.0 pM for GPC2 and 11.2 ± 2.3 pM for ΔHS GPC2; Figures 3H–3K; Figures S4A–S4C). Similarly, HEK293T cells transfected with the human GPC2 or ΔHS GPC2 cDNAs showed similar amounts of GPC2 expression, binding to D3-GPC2-IgG1, and response to D3-GPC2-PBD (Figures S4D–S4F). We next treated several high-GPC2-expressing cell lines with recombinant heparanase and did not observe any difference in binding of the D3-GPC2-IgG1 antibody (Figures S4G–S4I). Finally, to determine whether the D3-GPC2-IgG1 antibody displayed any cross-reactivity with any other human plasma membrane protein, we tested this antibody for reactivity against an array of over 6,000 human membrane proteins (Membrane Proteome Array [MPA];42 Figure 3L), which demonstrated very high specificity for GPC2 with no validated off-target antibody binding.

D3-GPC2-IgG1 binds human and mouse GPC2 similarly

To better understand the possibility of detecting any “on-target-off-tumor” toxicity of the D3-GPC2-PBD ADC in murine preclinical models, we next compared the ability of the D3-GPC2-IgG1 or ADC to bind to murine and human cell-surface GPC2. The human and mouse GPC2 homologs share a sequence identity of ∼83%, with all of the D3-GPC2 antibody epitope residues conserved between human and mouse GPC2 (Figure 3E; Figure S4J; Table S6). To functionally confirm these findings, we transiently transfected both the mouse and human GPC2 cDNAs into HEK293T cells and found cell-surface mouse and human GPC2 binds very similarly to the D3-GPC2-IgG1 antibody and dictates almost identical susceptibility to the D3-GPC2-PBD ADC (Figures S4E and S4F). We also treated the isogenic murine neuroblastoma cell line 9464D (9464D-Gpc2; Figure 3M) with the GPC2 ADC, which induced comparable cytotoxicity (mean IC50 = 10.6 ± 3.6 pM) and induction of apoptosis to human neuroblastoma cell lines (Figures 3K and 3N).12 Taken together, these data show that the D3-GPC2 binder is highly specific for a conformational epitope of both human and mouse GPC2, validating murine models as an appropriate initial species for D3-GPC2-PBD ADC safety profiling.

D3-GPC2-PBD induces a potent bystander cytotoxic effect

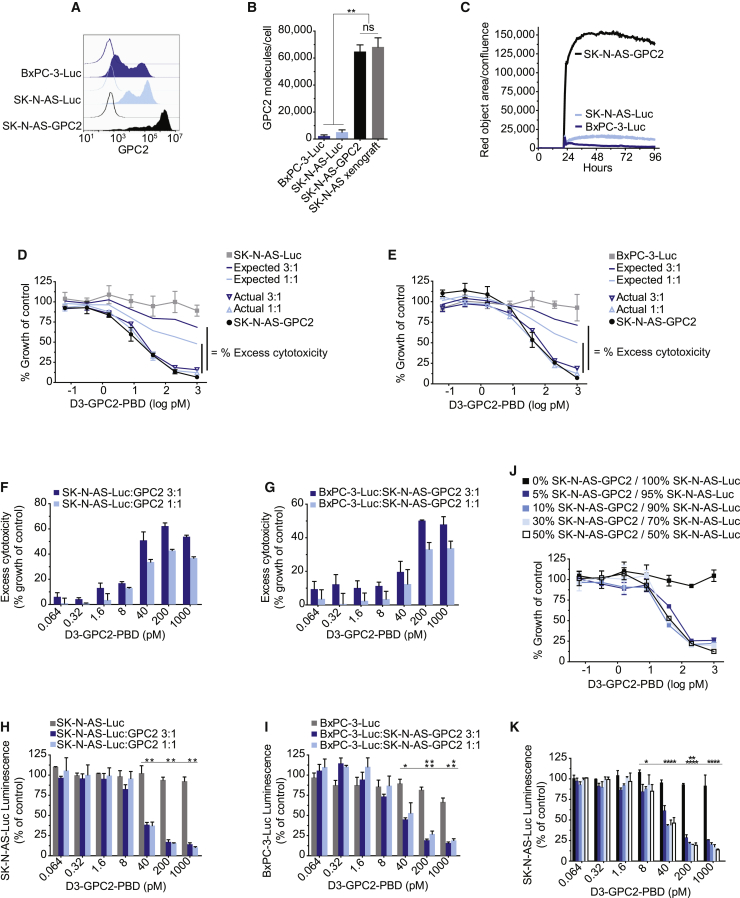

We next looked to comprehensively define the full complement of cytotoxic mechanisms of the GPC2-targeting D3-GPC2-PBD ADC using neuroblastoma as a model GPC2-expressing cancer. A potential benefit of ADCs over other immune-based cancer therapies is their ability to incite bystander cell killing.9, 10, 11 To test whether the D3-GPC2-PBD ADC exhibits bystander cytotoxic effects, we treated a combination of ADC-resistant, low-GPC2-expressing and ADC-responsive, high-GPC2-expressing cell line pairs. First, we engineered SK-N-AS-GPC2 isogenic cells to recapitulate the GPC2 cell-surface density of their matched xenografts and paired them with either luciferase-transduced SK-N-AS or pancreatic adenocarcinoma BxPC-3 cells (SK-N-AS-Luc and BxPC-3-Luc, respectively), both of which have low levels of cell-surface GPC2 expression, internalize limited amounts of the D3-GPC2-IgG1 antibody, and are resistant to the GPC2 ADC (Figures 4A–4E). We treated these paired cellular models (SK-N-AS-GPC2/SK-N-AS-Luc and SK-N-AS-GPC2/BxPC-3-Luc) with the D3-GPC2-PBD ADC and observed more cytotoxicity than expected, consistent with bystander cell killing (Figures 4D–4G). Furthermore, the differential expression of luciferase in the low-GPC2-expressing, ADC-resistant SK-N-AS/BxPC-3-Luc cells allowed direct measurement of the ADC-induced cytotoxicity to these cells with or without the presence of SK-N-AS-GPC2 cells, further validating potent bystander cytotoxicity (Figures 4H and 4I). Bystander cell killing was also observed in the co-incubated endogenous low- and high-GPC2-expressing cells NBL-S/SMS-SAN and NBL-S/NB-EbC1 (Figures S5A–S5G). Finally, we utilized a range of concentrations of paired SK-N-AS-GPC2/SK-N-AS-Luc cells to determine that 5% of SK-N-AS-GPC2 cells were enough to induce potent bystander cell killing in this in vitro system (Figures 4J and 4K).

Figure 4.

D3-GPC2-PBD induces bystander cell killing

(A–C) Representative GPC2 flow cytometry histograms (A), GPC2 molecules/cell (B), and internalization of D3-GPC2-IgG1-Red (C) of cells co-incubated in (D)–(K).

(D) Actual and expected relative growth plots of indicated ratios of SK-N-AS-GPC2/SK-N-AS-Luc co-incubated cells after treatment with D3-GPC2-PBD.

(E) Actual and expected relative growth plots of indicated ratios of SK-N-AS-GPC2/BxPC-3-Luc co-incubated cells after treatment with D3-GPC2-PBD.

(F and G) Summary plots of the excess cytotoxicity observed after treatment with D3-GPC2-PBD.

(H and I) Relative luminescence of SK-N-AS-Luc (H) or BxPC-3-Luc (I) cells alone and co-incubated with indicated ratios of SK-N-AS-GPC2 cells after treatment with D3-GPC2-PBD.

(J) Relative growth plots of indicated ratios of SK-N-AS-GPC2/SK-N-AS-Luc co-incubated cells after treatment with D3-GPC2-PBD.

(K) Relative luminescence of SK-N-AS-Luc cells alone and co-incubated with indicated ratios of SK-N-AS-GPC2 cells after treatment with D3-GPC2-PBD.

Data in (B), (F)–(I), and (K) represent mean ± SEM of 2–3 biological replicates with each replicate in (F)–(I) and (K) being done in at least technical duplicate. Data in (C)–(E) and (J) represent mean ± SEM from a representative experiment done in at least technical duplicate with each experiment being done at least two independent times. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.001; ns, not significant.

See also Figure S5.

D3-GPC2-IgG1 has no effect on cell growth and induces only modest antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity

Toward defining the full therapeutic potential of the D3-GPC2-IgG1 antibody, we next looked to study whether alone it induced neuroblastoma-specific cytotoxicity by blocking neuroblastoma signaling pathways or was able to induce antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) when co-incubated with immune effector cells. We first co-incubated GPC2- and GD2-expressing neuroblastoma cells (NB-EbC1 and SMS-SAN; Figures S6A and S6B) with D3-GPC2-IgG1 and a positive control GD2-targeting antibody dinutuximab, both alone and with human peripheral blood mononuclear or natural killer cells. Neither condition resulted in any D3-GPC2-IgG1-associated cytotoxicity (Figures S6C–S6J). To validate these in vitro findings, we created allografts from an engineered mouse neuroblastoma 9464D-Gpc2 isogenic cell line in the immunocompetent C57BL/6J mouse strain. Even considering apparent loss of the exogenously driven Gpc2 overexpression in vivo (Figure S6K), we observed only a modest growth inhibition and survival benefit with four treatments (2 times/week × 2 weeks) of 5 mg/kg of the D3-GPC2-IgG1 (Figures S6L and S6M). Taken together, these data suggest that despite being highly specific for GPC2, the D3-GPC2-IgG1 antibody alone or upon co-incubation with immune effector cells has limited growth-inhibitory properties, further supporting the development of this GPC2 antibody as an ADC.

D3-GPC2-PBD is cytotoxic to GPC2-expressing SCLCs

Considering the high levels of GPC2 on SCLCs, we next sought to investigate the targetability of this cancer histotype with the D3-GPC2-PBD ADC. First, we found comparable D3-GPC2-IgG1 internalization kinetics between SCLC and neuroblastoma cell lines (Figure 5A). We then treated this panel of SCLC cells with diverse MYC family drivers with the D3-GPC2-PBD ADC and free PBD dimer, which revealed IC50 values comparable with GPC2-expressing neuroblastoma cells (1.2 to >5,000 pM for the D3-GPC2-PBD ADC and 6.1–163 pM for free PBD dimer; Figure 5B; Table S1).12 Despite having abundant GPC2 cell-surface expression, the H146 cell line was more resistant to the D3-GPC2-PBD ADC (and free PBD), likely attributed to a dysfunctional TP53 protein similar to the NB-SD neuroblastoma cell line.12 H526 and H1930 SCLC cells treated with the D3-GPC2-PBD ADC exhibited increased DNA damage (γH2AX) and apoptosis (cleaved PARP and caspase-3) by western blot and caspase-3/-7 levels by luminescence assay, while H146 cells showed none of these protein elevations (Figures 5C and 5D; Figures S7A and S7B). Finally, D3-GPC2-PBD treatment of mice harboring H526 xenografts resulted in robust and sustained tumor regression and significantly increased survival with no side effects (Figures 5E and 5F; Figure S7C).

Figure 5.

D3-GPC2-PBD is potently cytotoxic to GPC2-expressing SCLCs

(A) Quantification of internalization of D3-GPC2-IgG1-Red in neuroblastoma and SCLC cell lines.

(B) Growth plots of SCLC cell lines 4 days after treatment with D3-GPC2-PBD.

(C) Western blot of H526 cells 3 days after treatment with D3-GPC2-PBD.

(D) Fold-change caspase-3/-7 levels of H526 cells 4 days after treatment with D3-GPC2-PBD.

(E) H526 xenograft volumes after treatment with D3-GPC2-PBD (n = 6–7 mice/cohort; represented as mean ± SEM).

(F) Progression-free survival (PFS) of treatment arms in (E). Median survival of 2.8 weeks for vehicle and >14.0 weeks for 1 mg/kg ADC, 1 mg/kg ADC × 4, and 3 mg/kg ADC treatment cohorts.

Data in (A), (B), and (D) represent mean ± SEM from a representative experiment done in technical triplicate with each experiment being done at least two independent times. Blue arrows in (E) and (F) represent initial ADC dose, and red arrows indicate subsequent 3 ADC doses for the 1 mg/kg ADC × 4 treatment cohort. ∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

See also Figure S7.

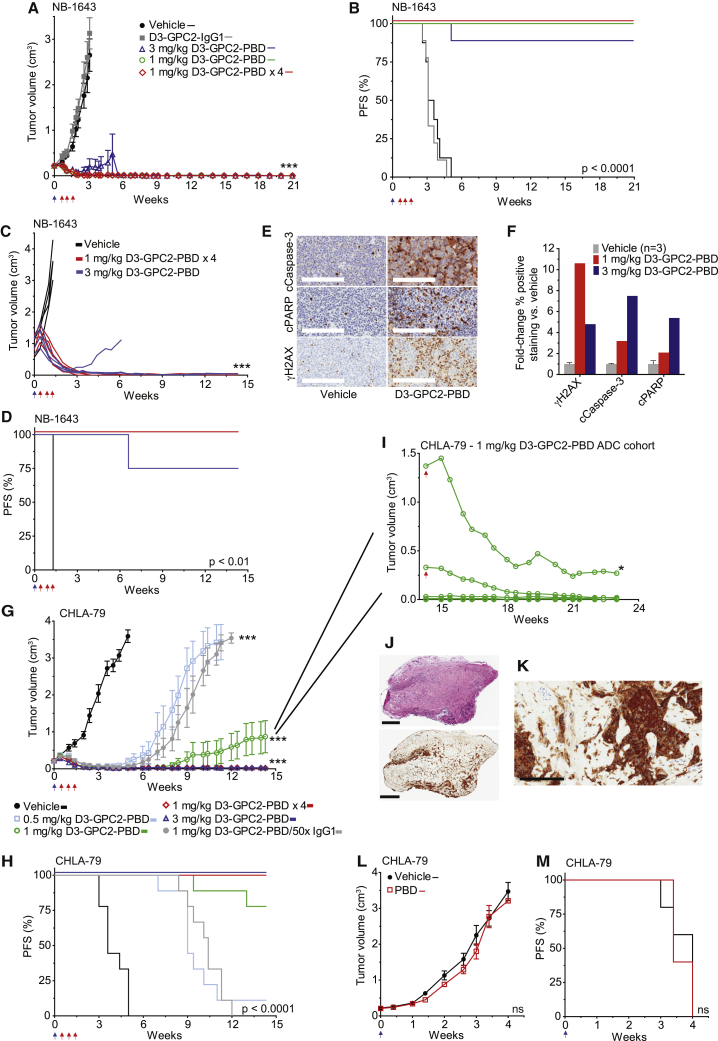

D3-GPC2-PBD induces tumor regression of neuroblastoma PDXs and xenografts with varying oncogenic drivers

To further validate robust in vivo efficacy of this ADC, we next tested it in diverse neuroblastoma PDXs and cell line xenografts with a range of GPC2 cell-surface expression and genomic aberrations that together recapitulate the clinical diversity of human neuroblastoma (Table S2). We have previously reported proof-of-concept anti-tumor efficacy of the GPC2-directed D3-GPC2-PBD ADC in the neuroblastoma NB-1643 PDX model.12 We now show additional longitudinal observation data from this study more than 20 weeks post-ADC dosing (Figures 6A and 6B). We saw no NB-1643 tumor recurrence in any of the 26 mice we continued to follow in this study, and they continued to maintain normal body weights (Figure S7D). Three of the 26 mice were taken off-study for reasons unrelated to tumor recurrence or drug-induced toxicity. We next found similar potency of this D3-GPC2-PBD ADC in treating more locally established NB-1643 PDXs with very large starting tumor volumes (Figures 6C and 6D). GPC2 ADC-treated NB-1643 tumors had increased expression of protein markers indicative of DNA damage and apoptosis throughout the tumor volume, suggesting an on-target cytotoxic effect and good ADC tumor penetration even in these significantly locally advanced cases (Figures 6E and 6F; Figures S7E and S7F).

Figure 6.

D3-GPC2-PBD induces specific, potent, and durable eradication of neuroblastomas by inducing DNA damage and apoptosis without GPC2 loss

(A) NB-1643 PDX tumor volumes after treatment with D3-GPC2-PBD (n = 8–9 mice/cohort; represented as mean ± SEM).

(B) PFS analysis of treatment arms in (A). Median survival of 3.4 weeks for vehicle; 3.1 weeks for D3-GPC2-IgG1; and >20.9 weeks for 1 mg/kg ADC, 1 mg/kg ADC × 4, and 3 mg/kg ADC treatment cohorts.

(C) Locally advanced NB-1643 PDX tumor volumes after treatment with D3-GPC2-PBD (starting mean tumor volumes = 0.98–1.01 cm3).

(D) PFS analysis of treatment arms in (C). Median survival of 1.3 weeks for vehicle and >14.3 weeks for 1 mg/kg ADC × 4 and 3 mg/kg ADC treatment cohorts.

(E) Immunohistochemistry (IHC) of locally advanced NB-1643 PDX tumors 4 days after treatment with 3 mg/kg D3-GPC2-PBD.

(F) Quantification of relative γH2AX, cleaved caspase-3, or cleaved PARP IHC staining after D3-GPC2-PBD treatment shown in (E) and Figures S7E and S7F.

(G) CHLA-79 xenograft volumes after treatment with D3-GPC2-PBD (n = 9 mice/cohort; represented as mean ± SEM).

(H) PFS analysis of treatment arms in (G). Median survival of 3.6 weeks for vehicle; 9 weeks for 0.5 mg/kg ADC; 10.4 weeks for 1 mg/kg ADC/50× IgG1; and >14.3 weeks for 1 mg/kg ADC, 1 mg/kg ADC × 4, and 3 mg/kg ADC cohorts.

(I) D3-GPC2-PBD ADC re-treatment (1 mg/kg; indicated with red arrow) of 2 tumors initially treated with 1 mg/kg of ADC in (G). Five additional mice in the initial 1 mg/kg ADC treatment cohort with stable tumor regression were also followed in parallel to the ADC re-treated mice.

(J) H&E (top) and GPC2 IHC (bottom) of indicated tumor (∗) from (I).

(K) High-power GPC2 IHC of indicated tumor (∗) from (I).

(L) CHLA-79 xenograft volumes after treatment with free PBD (n = 5 mice/cohort; represented as mean ± SEM).

(M) PFS analysis of treatment arms in (L). Median survival of 4.0 weeks for vehicle versus 3.4 weeks for free PBD.

Scale bars: 200 μm in (E) and (K) and 800 μm (top) and 900 μm (bottom) in (J). Blue arrows in (A)–(D), (G), (H), (L), and (M) represent initial ADC dose and red arrows in (A)–(D), (G), and (H) indicate subsequent 3 ADC doses for the 1 mg/kg ADC × 4 treatment cohort and in (I) indicate the ADC rechallenge dose given to 2 of 7 remaining mice on the CHLA-79 1 mg/kg ADC treatment arm.

cCaspase-3, cleaved caspase-3; cPARP, cleaved PARP.

∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

See also Figure S7.

GPC2 ADC treatment of the more modest GPC2-expressing CHLA-79 neuroblastoma xenograft (GPC2Mod, MYCN non-amplified, ALK wild type, TP53 wild type; Figure S2A) similarly showed potent tumor regression and significantly prolonged survival in a dose-dependent manner, with no observed toxicities (Figures 6G and 6H; Figure S7G). At study endpoint (100 days), we noted 2 tumors recurring in the 1 mg/kg ADC arm (tumor volumes of 1.37 and 0.33 cm3). To test whether these tumors remained susceptible to this GPC2 ADC, we re-dosed these mice with an additional 1 mg/kg of the D3-GPC2-PBD ADC and again observed rapid tumor regression, while additionally continuing to follow the other mice in this cohort (Figure 6I). After an additional 60 days, this 1 mg/kg ADC cohort was all taken off-study, and the residual 0.27 cm3 lesion (indicated by asterisk [∗] in Figure 6I) was analyzed showing a small fibrotic lesion, however, with very minimal viable tumor that continued to be GPC2 positive (Figures 6J and 6K). To further investigate the specificity of this ADC, we also dosed mice with 1 mg/kg D3-GPC2-PBD followed by 50× the D3-GPC2-IgG1 antibody, which abrogated a notable amount of the cytotoxicity induced by ADC treatment alone (gray circles [Figure 6G] and gray line [Figure 6H]). Finally, to further ensure that the in vivo efficacy we observed with this ADC was not due to free PBD dimer being released in the mouse circulation, we dosed mice harboring CHLA-79 xenografts with free PBD dimer (molar equivalent to 1 mg/kg ADC) and observed no tumor regression and no difference in survival (Figures 6L and 6M; Figure S7H).

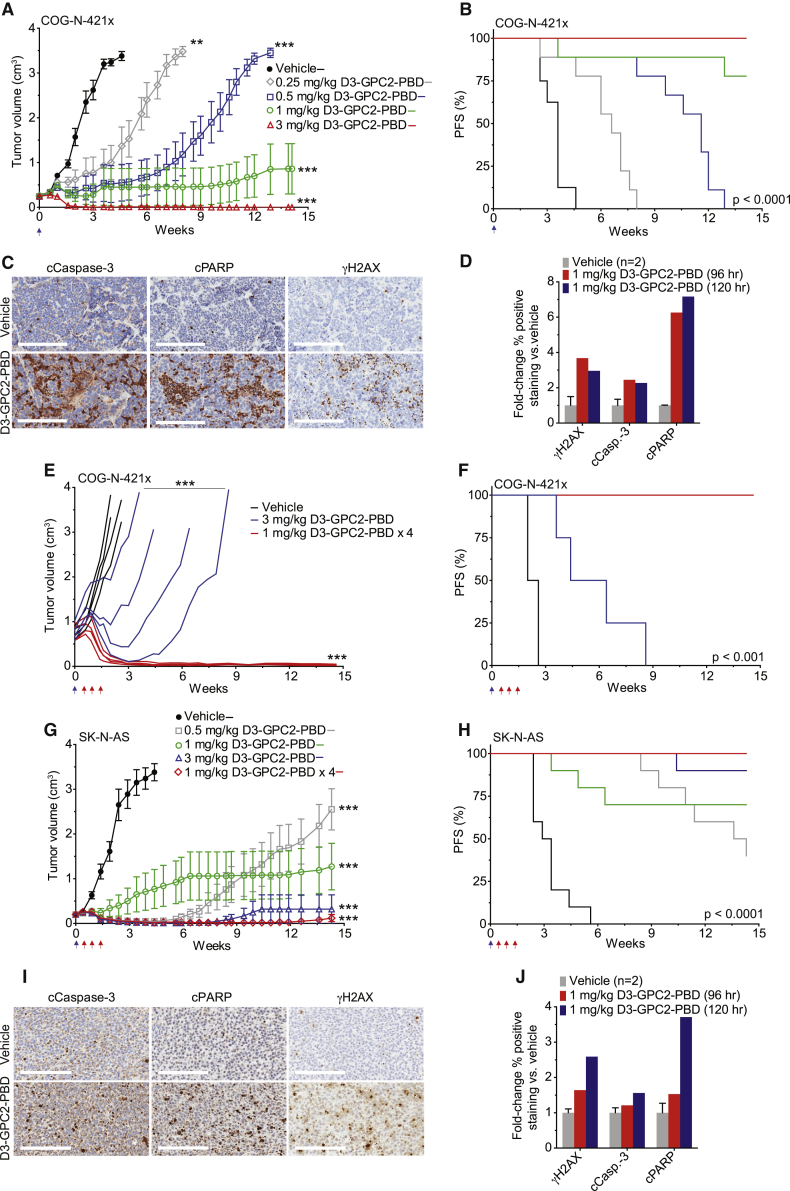

Finally, D3-GPC2-PBD ADC treatment of the neuroblastoma PDX model COG-N-421x (GPC2Hi, MYCN amplified, ALK wild type, TP53 wild type), significantly locally advanced COG-N-421x PDXs, and the high-GPC2-expressing neuroblastoma cell-line-derived xenograft SK-N-AS (GPC2Hi, MYCN non-amplified, ALK wild type, TP53 mutated) all resulted in significantly prolonged tumor regression and survival, upregulation of intratumoral DNA damage and apoptosis, and no observed toxicity (Figures 2A and 7A–7J; Figures S2A and S7I–S7K; Table S2). Together, these in vivo data demonstrate the ability of the D3-GPC2-PBD ADC to induce sustained tumor regression across a wide range of diverse neuroblastoma and SCLC preclinical models.

Figure 7.

D3-GPC2-PBD significantly extends the survival of mice with neuroblastoma COG-N-421x PDXs and SK-N-AS xenografts

(A) COG-N-421x PDX volumes after treatment with D3-GPC2-PBD (n = 8–9 mice/cohort; represented as mean ± SEM).

(B) PFS analysis of treatment arms in (A). Median survival of 3.6 weeks for vehicle, 6.6 weeks for 0.25 mg/kg ADC, 11.6 weeks for 0.5 mg/kg ADC, and >14.1 weeks for 1 and 3 mg/kg ADC treatment cohorts.

(C) IHC of COG-N-421x PDXs 5 days after treatment with 1 mg/kg D3-GPC2-PBD.

(D) Quantification of relative γH2AX, cleaved caspase-3, or cleaved PARP IHC staining after D3-GPC2-PBD treatment.

(E) Locally advanced COG-N-421x PDX volumes after treatment with D3-GPC2-PBD (n = 4 mice/cohort; starting mean tumor volumes = 0.75–0.77 cm3).

(F) PFS of treatment arms in (E). Median survival of 2.3 weeks for vehicle, 5.4 weeks for 3 mg/kg ADC, and >14.6 weeks for 1 mg/kg ADC × 4 treatment cohorts.

(G) Neuroblastoma SK-N-AS xenograft volumes after treatment with D3-GPC2-PBD (n = 10 mice/cohort; represented as mean ± SEM).

(H) PFS of treatment arms in (G). Median survival of 3.2 weeks for vehicle; 14.0 weeks for 0.5 mg/kg ADC; and >14.3 weeks for 1 mg/kg ADC, 1 mg/kg ADC × 4, and 3 mg/kg ADC treatment cohorts.

(I) IHC of SK-N-AS xenografts 5 days after treatment with 1 mg/kg D3-GPC2-PBD.

(J) Quantification of relative γH2AX, cleaved caspase-3, or cleaved PARP IHC staining after D3-GPC2-PBD treatment.

Scale bars: 200 μm in (C) and (I). Blue arrows in (A), (B), and (E)–(H) represent initial ADC dose, and red arrows in (E)–(H) indicate subsequent 3 ADC doses for the 1 mg/kg ADC × 4 treatment cohort.

∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

See also Figure S7.

Discussion

We propose that GPC2 is an optimal immunotherapeutic target for neuroblastoma, SCLCs, and other cancers because of its cell-surface location, tumor-specific expression, tumor dependence, transcriptional activation by MYCN, and possible enriched expression on cancer stem cells. The D3-GPC2-PBD ADC was potently efficacious across a diverse array of neuroblastoma and SCLC in vivo models, most of which were generated from heavily pretreated patients with chemotherapy-resistant disease. To fully understand the scope of this ADC’s efficacy, we also treated locally advanced neuroblastoma tumors and found that even one ADC dose could similarly eradicate these large tumors. Furthermore, the ability of this ADC to exert potent bystander cell killing is of utmost importance for solid tumors that often have heterogeneous target expression, thus making them susceptible to immune escape from outgrowth of low-target-expressing tumor clones. However, the precise contribution of bystander cell cytotoxicity to this ADC’s potent efficacy is difficult to fully quantify given GPC2’s prominent role in cell growth, which makes in vivo studies technically challenging. Additionally, here we have focused on transplantable PDX and cell line xenograft models to provide proof-of-concept targeting of GPC2 with the D3-GPC2-PBD ADC in these malignancies given their well-validated recapitulation of human neuroblastoma and SCLC. However, future studies in transgenic immunocompetent murine cancer models will also be important for studying the efficacy of this ADC in spontaneously occurring tumors with potentially less disruption of neovascularization and further to quantify the synergy of this ADC with the host immune system.

Despite its potent cytotoxicity, the D3-GPC2-PBD ADC, which binds human and murine GPC2 identically, induced no clinical signs of murine toxicity, supporting a potential wide therapeutic index of targeting GPC2 with ADCs in humans. Our findings of the D3-GPC2-PBD ADC targeting an extended GPC2 conformational epitope involving GPC2 exon 2 may lend additional support to the safety of targeting GPC2, as it is predicted that most normal tissues express a major GPC2 isoform that is lacking this domain.12 However, additional studies need to be performed to confirm the existence of this truncated GPC2 variant at the protein level in normal tissues to fully validate this additional aspect of potential tumor specificity. Ultimately, non-human primate toxicology studies will also need to be performed to further evaluate the clinical safety of this ADC. Another potential therapeutic advantage of this ADC is its binding to the GPC2 core protein with limited involvement of GPC2’s HS side chains, as the glycanation pattern of GPC2 is highly variable. However, the absence of D3-GPC2-IgG1 binding to these HS moieties, which have been found to be critical components in facilitating glypican ligand-receptor cell-surface interactions,15,16,43,44 may explain the fact that incubation of this antibody with GPC2-expressing neuroblastoma cells has no phenotypic consequences. Finally, the well-documented ability of GPC2 and other glypicans to undergo cleavage at their cell-surface GPI anchor45, 46, 47 makes it imperative to understand how ADC treatment may alter the kinetics of this process in neuroblastoma and SCLC in early phase human trials. However, the data presented here suggest that cell-surface GPC2 expression may persist despite ADC treatment. Taken together, these data comprehensively support the robust targetability of GPC2 with ADCs in neuroblastoma, SCLCs, and other GPC2-expressing histotypes and lay the framework for the clinical translation of these therapeutics.

Limitations of study

While here we focused on the D3-GPC2-IgG1 antibody and PBD dimers as our ADC components, clearly GPC2 antibodies targeting different epitopes or utilization of alternative ADC payloads needs to be studied and may generate equally or even more effective and safe ADCs that may have enhanced internalization kinetics, improved cytotoxicity, an increased therapeutic index, or the ability to concurrently inhibit critical GPC2 signaling pathways. We have focused some of our initial studies beyond neuroblastoma here on the MYCN-amplified SCLC H526 cell line given our initial goal to understand whether MYCN transcriptionally activates GPC2 in other malignancies. However, because MYCN amplification in SCLC is a rare event, we also chose a panel of SCLC cell lines with diverse MYC family drivers to validate both that high GPC2 expression and dependence, and susceptibility to this ADC is not limited to this rare MYCN-amplified SCLC subset. Nonetheless, additional work is needed to understand which particular SCLC subsets are more likely to harbor higher levels of cell-surface GPC2 and thus be the focus of ADC targeting in the clinic. Finally, given the shared MYCN transcriptional activation and tumor dependence between neuroblastomas and SCLCs, clearly the role that MYCN and also other MYC family members play in the regulation of GPC2 expression and the importance of GPC2 in tumorigenesis across all high-GPC2-expressing cancers warrants additional investigation.

Lastly, while we show ultra-high levels of GPC2 on possible neuroblastoma and SCLC stem cells within the preclinical models utilized here overall supporting a role for GPC2 in neuroblastoma and SCLC tumorigenesis, non-stem cells within these preclinical models also have sufficient GPC2 expression to be targeted by this ADC. Furthermore, cellular models without the presence of this stem cell-like population are equally susceptible to this GPC2 ADC. Thus, the contribution of this stem cell-like population with ultra-high GPC2 expression to the overall efficacy of this ADC remains unclear, and additional experiments such as lineage tracing and adoptive transfer studies will need to be performed to fully address this question. The function of GPC2 in neuroblastoma and SCLC stem cells and this protein’s specific role in the tumor self-renewal process also warrants further investigation. GPC2’s previously described role in WNT pathway signaling, shown by us and others,12,19 suggests the possibility of GPC2 also facilitating WNT signaling in the tumor stem cell compartment.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Human D3-GPC2-IgG1 | Bosse et al., 201712 | N/A |

| Human D3-GPC2-Fab | Bosse et al., 201712 | N/A |

| Human D3-GPC2-PBD | Bosse et al., 201712 | N/A |

| InVivoMAB Human IgG1 isotype control | BioXCell | Cat # BE0297; RRID: AB_2687817 |

| Dinutuximab | Laboratory of Dr. Paul Sondel | N/A |

| Glypican-2 Antibody (F-5) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat # sc-393824; RRID: AB_2714029 |

| β-Actin Antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat # 4967; RRID: AB_330288 |

| Cleaved Caspase-3 (Asp175) (5A1E) Rabbit mAb (Western blot and IHC) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat # 9664; RRID: AB_2070042 |

| Cleaved PARP1 (Asp214) Antibody (Human Specific; western blot and IHC) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat # 9541; RRID: AB_331426 |

| Phospho-Histone H2A.X (Ser139) Antibody (Western blot and IHC) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat # 2577; RRID: AB_2118010 |

| N-MYC Antibody (Western blot) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat # 9405; RRID: AB_10692664 |

| Anti-Pan-Myc Antibody (EPR18863) | Abcam | Cat # ab195207 |

| Anti-c-Myc Antibody (Y69) | Abcam | Cat # ab32072; RRID: AB_731658 |

| Normal Rabbit IgG | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat # 2729; RRID: AB_1031062 |

| Histone H3 (D2B12) XP® Rabbit mAb (ChIP Formulated) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat # 4620; RRID: AB_1904005 |

| N-Myc Antibody (pAb) (ChIP PCR) | Active Motif | Cat # 61185; RRID: AB_2793543 |

| APC Anti-Human CD117 (c-kit) Antibody (Clone 104D2) | BioLegend | Cat # 313206; RRID: AB_314985 |

| APC Anti-Human Ganglioside GD2 Antibody (Clone 14G2a) | BioLegend | Cat # 357306; RRID: AB_2563084 |

| CD166 Antibody, Anti-Human, REAfinity (APC, Clone REA442) | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat # 130-119-769; RRID: AB_2751830 |

| APC Anti-Human CD44 Antibody (Clone BJ18) | BioLegend | Cat # 338806; RRID: AB_1501195 |

| CD87 Antibody, Anti-Human (APC, Clone VIM5) | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat # 130-099-456; RRID: AB_2659423 |

| APC Anti-Human CD338 (ABCG2) Antibody (Clone 5D3) | BioLegend | Cat # 332020; RRID: AB_1227470 |

| CD133/2 Antibody, Anti-Human (APC, Clone 293C3) | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat # 130-113-184; RRID: AB_2726010 |

| PE/Cyanine7 Anti-Mouse CD133 Antibody (Clone 315-2C11) | BioLegend | Cat # 141210; RRID: AB_2564069 |

| ABCG2 Antibody (B-1) Alexa Fluor® 790 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat # sc-377176 AF790 |

| PerCP Anti-Mouse CD117 (c-kit) Antibody (Clone 2B8) | BioLegend | Cat # 105822; RRID: AB_2131599 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| One Shot Stbl3 Chemically Competent E. coli | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat # C737303 |

| Biological samples | ||

| SK-N-AS xenograft | CHOP Neuroblastoma Biobank | N/A |

| CHLA-79 xenograft | CHOP Neuroblastoma Biobank | N/A |

| COG-N-421x PDX | Children’s Oncology Group (COG) Cell Culture and Xenograft Repository | N/A |

| RH07-1x PDX | CHOP Neuroblastoma Biobank | N/A |

| COG-N-453x PDX | Children’s Oncology Group (COG) Cell Culture and Xenograft Repository | N/A |

| COG-N-440x PDX | Children’s Oncology Group (COG) Cell Culture and Xenograft Repository | N/A |

| COG-N-471x PDX | Children’s Oncology Group (COG) Cell Culture and Xenograft Repository | N/A |

| COG-N-453x PDX | Children’s Oncology Group (COG) Cell Culture and Xenograft Repository | N/A |

| NB-1643 PDX | Laboratory of Dr. Peter Houghton | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| PBD Dimer | Levena Biopharma US | Cat # D4008 |

| Recombinant Human Glypican 2 Protein, CF | R&D systems | Cat # 2304-GP-050 |

| Puromycin Dihydrochloride from Streptomyces alboniger | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat # P8833 |

| Recombinant Human Active heparanase/HPSE Protein, CF | R&D systems | Cat # 7570-GH-005 |

| Phenylmethanesulfonyl Fluoride (PMSF) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat # 8553 |

| Polybrene® | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat # sc-134220 |

| GIBCO FreeStyle 293 Expression Medium | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat # 12338026 |

| FectoPRO DNA Transfection Reagent | VWR | Cat # 10118-444 |

| CaptureSelect LC-kappa (Human) Affinity Ligand | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat # 1033270500 |

| FuGENE® 6 Transfection Reagent | Promega | Cat # E2691 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay | Promega | Cat # G7571 |

| Caspase-Glo® 3/7 Assay System | Promega | Cat # G8091 |

| ONE-Glo Luciferase Assay System | Promega | Cat # E6110 |

| SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat # 18080051 |

| RNeasy Mini Kit | QIAGEN | Cat # 74104 |

| QIAshredder | QIAGEN | Cat # 79654 |

| TaqMan™ Universal PCR Master Mix | Applied Biosystems | Cat # 4304437 |

| QuickChange Multi Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Agilent | Cat # 200515 |

| IncuCyte® Fabfluor-pH Red Antibody Labeling Reagent | Essen Bioscience | Cat # 4722 |

| SimpleChIP® Plus Sonication Chromatin IP Kit | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat # 56383S |

| PerfeCTa SYBR Green SuperMix ROX | Quantabio | Cat # 95055-100 |

| BD Quantibrite Beads PE Phycoerythrin Fluorescence Quantitation Kit | BD | Cat # 340495 |

| PE/R-Phycoerythrin Conjugation Kit – Lightning-Link® | Abcam | Cat # ab102918 |

| Ni-NTA biosensors | ForteBio | Cat # 185101 |

| Deposited data | ||

| GPC2-D3-Fab crystal structure | This paper | PDB code PDB: 6WJL (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/6WJL) |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| SMS-SAN | CHOP Cell Line Bank | RRID: CVCL_7136 |

| NB-EbC1 | CHOP Cell Line Bank | RRID: CVCL_E218 |

| SH-SY5Y | CHOP Cell Line Bank | RRID: CVCL_0019 |

| SK-N-AS | CHOP Cell Line Bank | RRID: CVCL_1700 |

| NBL-S | CHOP Cell Line Bank | RRID: CVCL_2136 |

| SK-N-SH | CHOP Cell Line Bank | RRID: CVCL_0531 |

| NB-SD | CHOP Cell Line Bank | RRID: CVCL_LF68 |

| NB-1643 | CHOP Cell Line Bank | RRID: CVCL_5627 |

| HEK293T | ATCC | Cat # CRL-3216; RRID: CVCL_0063 |

| H526 (NCI-H526) | ATCC | Cat # CRL-5811; RRID: CVCL_1569 |

| H209 (NCI-H209) | ATCC | Cat # HTB-172; RRID: CVCL_1525 |

| H146 (NCI-H146) | ATCC | Cat # HTB-173; RRID: CVCL_1473 |

| H1930 (NCI-H1930) | ATCC | Cat # CRL-5906; RRID: CVCL_1507 |

| H82 (NCI-H82) | ATCC | Cat # HTB-175; RRID: CVCL_1591 |

| FreeStyle 293-F Cells | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat # R79007; RRID: CVCL_D603 |

| 9464D | Laboratory of Dr. Paul Sondel | N/A |

| 9464D-Gpc2 | This paper | N/A |

| SH-SY5Y-Empty | This paper | N/A |

| SH-SY5Y-GPC2 | This paper | N/A |

| SH-SY5Y-ΔHS GPC2 | This paper | N/A |

| Kelly-Empty | This paper | N/A |

| Kelly-GPC2 | This paper | N/A |

| Kelly-ΔHS GPC2 | This paper | N/A |

| 293T-Empty | This paper | N/A |

| 293T-GPC2 | This paper | N/A |

| 293T-ΔHS GPC2 | This paper | N/A |

| SK-N-AS-GPC2 | This paper | N/A |

| SK-N-AS-Luc | This paper | N/A |

| BxPC-3-Luc | This paper | N/A |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse: C.B-17 scid (C.B-Igh-1b/IcrTac-Prkdcscid) | Taconic Biosciences | Cat # CB17SC-F; RRID: IMSR_TAC:cb17sc |

| Mouse: C57BL/6J | Jackson Laboratory | Cat # 000664; RRID: IMSR_JAX:000664 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| MYCN TaqMan® Gene Expression Assay | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat # Hs00232074_m1 |

| GPC2 TaqMan® Gene Expression Assay | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat # Hs00415099_m1 |

| UBC TaqMan® Gene Expression Assay | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat # Hs00824723_m1 |

| HPRT1 TaqMan® Gene Expression Assay | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat # Hs02800695_m1 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pMD2.G (encoding envelope plasmid VSV-G) | Laboratory of Dr. Robert Schnepp | N/A |

| psPAX2 (packaging plasmid) | Laboratory of Dr. Robert Schnepp | N/A |

| Gpc2 pDONR221 | This paper | N/A |

| pLenti CMV Puro DEST (w118-1) | Campeau et al., 200948 | Addgene plasmid # 17452; RRID: Addgene_17452 |

| Gpc2 pLenti CMV Puro Vector (Gpc2) | This Paper | N/A |

| GPC2 pLenti CMV Puro Vector (GPC2) | Bosse et al., 201712 | N/A |

| ΔHS GPC2 pLenti CMV puro vector (ΔHS GPC2) | This paper | N/A |

| GPC224-554 pHLsec vector (GPC224-554) | This paper | N/A |

| ΔHS GPC224-554 pHLsec vector (ΔHS GPC224-554) | This paper | N/A |

| GPC224-493 pHLsec vector (GPC224-493) | This paper | N/A |

| ΔHS GPC224-493 pHLsec vector (ΔHS GPC224-493) | This paper | N/A |

| D3-GPC2-Fab pcDNA3.4 vector | This paper | N/A |

| D3-GPC2-Fab-Heavy chain pcDNA3.4 vector | This paper | N/A |

| D3-GPC2-Fab-kappa light chain pcDNA3.4 vector | This paper | N/A |

| GPC2 MISSION® shRNA Plasmid | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat # TRCN0000220037; shGPC2 Exon 4 (2) |

| GPC2 MISSION® shRNA Plasmid | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat # TRCN0000147974; shGPC2 3′UTR (4) |

| MYCN MISSION® shRNA Plasmid | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat # TRCN00000358381; shMYCN-1 (1) |

| MYCN MISSION® shRNA Plasmid | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat # TRCN0000020695; shMYCN-5 (5) |

| MYCN MISSION® shRNA Plasmid | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat # TRCN0000020696; shMYCN-6 (6) |

| MYCN MISSION® shRNA Plasmid | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat # TRCN0000020697; shMYCN-7 (7) |

| MISSION® pLKO.1-puro Non-Mammalian shRNA Control Plasmid | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat # SHC002; shNTC (C) |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| STAR | Dobin et al., 201349 | https://github.com/alexdobin/STAR |

| RSEM | Li and Dewey, 201150 | https://github.com/deweylab/RSEM |

| Clustal omega | Sievers and Higgins, 201851 | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/services/web_clustalo/toolform.ebi |

| FlowJo 10.0 | FlowJo LLC | https://www.flowjo.com/ |

| XDS | Kabsch, 201052 | https://xds.mr.mpg.de/ |

| Phenix | Adams et al., 201053 | https://phenix-online.org/ |

| Coot | Emsley et al., 201054 | https://www2.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/personal/pemsley/coot/ |

| PyMOL | The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.8 Schrödinger, LLC. | https://pymol.org/2/#products |

| SBGrid | SBGrid Consortium | https://sbgrid.org/ |

| Octet Data Analysis Software 9.0.0.6 | ForteBio | https://www.sartorius.com/en/products/protein-analysis/octet-systems-software |

| GraphPad Prism | GraphPad Software | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

| Phyre2 | Kelley et al., 201555 | http://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/∼phyre2/html/page.cgi?id=index |

| UCLA anisotropy server | Strong et al., 200656 | http://services.mbi.ucla.edu/anisoscale/anisoscale_xds/ |

| Other | ||

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Kristopher R. Bosse (bossek@chop.edu).

Materials availability

All unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from the lead contact with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

Data and code availability

The data from public resources analyzed in this study is available from the references noted in the text. The data associated with the crystal structure has been deposited to the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under accession code 6WJL (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/6WJL). Any other dataset or code from this study is available from the Lead Contact.

Experimental model and subject details

PDX and xenograft models

Human neuroblastoma PDXs and cell line-derived xenografts were acquired from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Neuroblastoma biobank and the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) Cell Culture and Xenograft Repository. Tumors were typically implanted into the flanks of female 5-9 week-old C.B-17 scid mice (C.B-Igh-1b/IcrTac-Prkdcscid; Taconic Biosciences), typically each weighing 16-25 g. When a majority of mice had tumors at study enrollment tumor size, animals were randomly assigned into treatment cohorts and mean/median tumor volumes of each cohort were calculated to ensure similar starting tumor volumes. Each mouse was then given a single dose of their respective ADC treatments in PBS or vehicle (Day 0) via intraperitoneal (IP) injection. In some efficacy studies, one cohort of mice received 3 subsequent ADC 1 mg/kg IP injections over the following 2 weeks (1 mg/kg x 4 cohort). For the H526 xenograft and 9464D-Gpc2 allograft studies, tumors were implanted into the flanks of C.B-17 scid mice or C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME), respectively, utilizing matrigel, subsequently expanded into study mice and, after randomization, were treated with IP ADC, human IgG1 (BioXCell, #BE0297), or D3-GPC2-IgG1. For all studies, mouse weights and tumor volumes were measured at least twice weekly and tumor volumes were calculated as volume = ([diameter1/2 + diameter2/2]3∗0.5236)/1000. Mice, unless otherwise noted, were treatment naive and maintained in cages of up to 5 mice under barrier conditions with ready access to feed and water. Experiments were conducted using protocols and conditions approved by the CHOP Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC; Approved IACUC Protocol #643) with adherence to the NIH guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals in a pathogen-free facility fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC). Mice were euthanized when tumor volumes reached/exceeded 2-3 cm3 or an animal displayed any signs of clinical distress. The gender of each neuroblastoma or SCLC PDX or cell line xenograft is as follows, male: H526, NB-1643, COG-N-421x, and COG-N-453x and female: COG-N-440x, COG-N-471x, CHLA-79, and SK-N-AS.

Cell lines

Human-derived neuroblastoma, SCLC, and HEK293T cell lines were obtained from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia cell line bank, the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) Cell Culture and Xenograft Repository, or the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured in RPMI containing 10% FBS, 2 mM L-Glutamine, and 1% streptomycin/penicillin at 37°C under 5% CO2. Where noted, neuroblastoma cells were also cultured in Neurobasal media (DMEM/F12, 20 ng/mL bFGF, 20 ng/mL FGF, 2.5 ug/mL heparin, B27 minus Vitamin A, and N2 supplement). The murine 9464D neuroblastoma cell line was kindly provided by Dr. Paul Sondel.57 The genomic identity of each cell line was confirmed with genotyping using a GenePrint® 24 System (Promega) and cell lines were routinely tested to confirm the lack of mycoplasma contamination. The gender of each neuroblastoma or SCLC cell line is as follows, male: H146, H1930, H209, H526, H82, NB-EbC1, and NBL-S and female: SMS-SAN, SH-SY5Y, NB-SD, Kelly, SK-N-SH, and SK-N-AS.

Method details

Construct design, protein expression, and purification

The GPC2 pLenti CMV puro vector (GPC2) was constructed as previously described.12 To achieve the ΔHS GPC2 pLenti CMV puro vector (ΔHS GPC2), where putative post-translationally modified serine amino acids 55, 92, 155, 500, and 502 were each mutated to an alanine, the GPC2 pLenti CMV puro vector (GPC2) was mutated utilizing a QuickChange Multi Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Murine Gpc2 cDNA in a pCMV6 vector was purchased from Origene (MC202461), PCR amplified to attach attB sites, recombined with a pDONOR221 vector using a Gateway® BP Clonase® II enzyme and subsequently cloned into a pLenti CMV puro DEST (w118-1) plasmid, which was a gift from Eric Campeau48 and was purchased via Addgene (plasmid #17452), with a Gateway® LR clonase enzyme (Invitrogen) via the manufacturer’s instructions to make a Gpc2 pLenti CMV puro vector (Gpc2).

Genes for the human GPC2 constructs GPC224-554, ΔHS GPC224-554, GPC224-493, and ΔHS GPC224-493, all containing a C-terminal His6x tag were codon-optimized for expression in human cells and cloned into the pHLsec vector (GeneArt). The ΔHS GPC2 variants were synthesized by replacing putative post-translationally modified serine amino acid sites with threonine residues as indicated. GPC2 point mutants were generated using a KOD-Plus-Mutagenesis Kit per the manufacturer’s instructions. All constructs were transiently transfected and expressed in suspension HEK293F cells and purified using Ni-NTA affinity chromatography, followed by gel filtration in 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, and 150 mM NaCl. Genes for the heavy and light chains of the D3-GPC2-Fab were codon-optimized for expression in human cells and cloned into the pcDNA3.4 vector (GeneArt). The Fab was transiently expressed in HEK293F cells and purified using Kappa-Select affinity chromatography, followed by cation exchange chromatography and size exclusion chromatography in 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0 and 150 mM NaCl.

Crystallization and structure determination of the D3-GPC2-Fab complex

The purified D3-GPC2-Fab and ΔHS GPC224-493 protein were mixed at a 1:2.5 molar ratio. A ligand protein VHH was also added in 2.5 molar excess of the Fab to aid in the crystallization process.58 The complex was purified using size exclusion chromatography in 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, and 150 mM NaCl buffer and set up for crystallization at a 5 mg/mL concentration. The protein was mixed with conditions from sparse matrix screens (JCSG Top96 and Microlytic MCSG) in a 1:1 ratio using the sitting drop method with an Oryx4 crystallization robot (Douglas Instruments). Rod shaped crystals of dimension 0.5 × 0.1 × 0.1 mm were obtained from the Microlytic MCSG2 screen in a condition containing 0.2 M NaCl, 10% (w/v) PEG 3350, and 0.1 M disodium hydrogen phosphate. The crystals diffracted to a resolution of 3.3 Å at the GM/CA 23-ID-D beamline at the Argonne Photon Source. Data were processed and scaled using XDS.52 A small level of anisotropy was present in the data (spread in values of the three principle components = 28.34 A∗∗2) as detected using the UCLA anisotropy server (http://services.mbi.ucla.edu/anisoscale/anisoscale_xds/), and was scaled during refinement and map calculations by phenix.refine.53 The structure was determined by molecular replacement using Phaser59, with a homology model from Phyre255 generated using the GPC1 crystal structure (PDB ID: 4ACR)60, a Fab from our internal database, and the VHH ligand (from PDB ID: 6ANA) as starting models. Iterations of model building and refinement were performed using Coot54 and phenix.refine.53 Non-crystallographic symmetry restraints were used during refinement. All software were accessed through SBGrid.61

Binding assays using biolayer interferometry (BLI)

The binding affinity of the D3-GPC2-Fab to different ΔHS GPC2 variants and point mutants was measured by BLI on an Octet Red96 instrument (FortéBio) at 25°C. All proteins were diluted in 1X kinetics buffer (PBS, pH 7.4, 0.01% [w/v] BSA, 0.002% [v/v] Tween-20). GPC2 protein (ΔHS variants and point mutants) were immobilized on Ni-NTA sensors. The loaded biosensors were dipped into wells containing serial dilutions of the D3-GPC2-Fab to determine the rate of association. Sensors were then dipped back into kinetics buffer to monitor the dissociation rate. Curves were fitted to a 1:1 binding model and the kinetic parameters (kon and koff) and equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) were evaluated using FortéBio’s data analysis software (Version 9.0).

MYCN chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) PCR

The SCLC H526 cell line was crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde and cells were then washed with cold PBS and resuspended in 1.0 μM phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). The SimpleChIP® Plus Sonication Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Kit (Cell Signaling Technology) was then utilized per the manufacturer’s instructions. An active Motif Q800AMS Sonicator (power = 750 Watts) with a QSonica #4905 high capacity chiller was utilized. Chromatin fragmentation analysis was done using a Genomic DNA ScreenTape on an Agilent 2200 TapeStation. Antibodies utilized were normal rabbit IgG (4 μL; Cell Signaling, #2729), Histone H3 (D2B12) XP Rabbit mAb (10 μL; Cell Signaling, #4620), and N-MYC (4 μL; Active Motif, #61185). Millipore Sigma Protein A+G Magnetic Beads were used in place of the magnetic beads provided in the SimpleChIP® Kit. For PCR, 4 μL of DNA from the MYCN ChIP was combined with PerfeCTa SYBR Green SuperMix and primers at final concentrations of 1X SYBR Green ROX and 0.5 μM for each primer. The qPCR data were analyzed by normalizing the input value to 100%, determining the difference between the input and experimental Ct values (ΔCt), and finding the percent input (100x2ΔCt).

Real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from neuroblastoma cells utilizing Qiashredder and RNeasy Mini Kits (QIAGEN) and mRNAs were converted to cDNA using a SuperScript™ III First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Taqman® gene expression assays (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used to quantitate MYCN (Hs00232074_m1), GPC2 (Hs00415099_m1), UBC (Hs00824723_m1), and HPRT1 (Hs02800695_m1) mRNA levels. RT-PCR analysis was performed on an Applied Biosystems 7900HT Sequence Detection System using standard cycling conditions and mRNA expression values were quantified with corresponding standard curves. Ratios of mRNA quantities were normalized by comparing mRNA expression of interest to the geomean of mean UBC and HPRT1 mRNA expression values.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

γH2AX IHC was run on a Leica autostainer as previously described,12 except an E1 antigen retrieval solution was utilized for 20 minutes. The cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase-3 IHC were achieved with an overnight primary antibody incubation and an ABC Staining Kit (PK-6100, Vector Labs) with citrate (pressure cooker) antigen retrieval. The antibodies utilized were as follows: Cleaved PARP (1:100; Cell Signaling Technology, #9541), Cleaved caspase-3 (1:100; Cell Signaling Technology, #9664), and Phospho-Histone H2A.X (Ser139) (1:100; Cell Signaling Technology, #2577). Representative pictures were taken of, and the IHC staining quantified on, scanned IHC slides with the Aperio ImageScope program v12.2.2.5015.

Flow cytometry

Dissociated single cell suspensions were achieved with 0.02% EDTA in HBSS, washed with cold PBS, and cells were stained with LIVE/DEAD™ Fixable Violet Dead Cell Stain (Invitrogen) for 30 minutes in the dark on ice. Cells were then washed with cold PBS, incubated in the dark on ice for 30 minutes with the indicated primary antibody in 10% γ-Globulins (from human blood, Sigma-Aldrich G4386), washed with cold PBS x 2, and fixed in 1% formaldehyde. Neuroblastoma PDXs/xenografts were dissociated in a gentleMACS™ Dissociator at 37°C in the presence of enzymes supplied by the manufacturer, passed sequentially through 70 μm and 100 μm cell strainers, and depleted of red blood cells via incubation with 1X Red Blood Cell Lysis Solution (Miltenyi Biotech). Mouse cell depletion was achieved by magnetic separation with LS columns following cell labeling with Mouse Cell Depletion Cocktail (Miltenyi Biotech). Recovered tumor cells were stained as above. Stained samples were run on a Beckman CytoFLEX S or LX cytometer and analyzed using FlowJo software. To semi-quantitate GPC2 cell surface expression, a BD Quantibrite Beads PE Fluorescence Quantitation Kit was run in parallel with a subset of samples according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The D3-GPC2-IgG1 antibody was conjugated to PE using a PE/R-Phycoerythrin Conjugation Kit (Abcam, ab102918). Other primary antibodies utilized were as follows: APC anti-human CD117 (c-kit) antibody (clone 104D2, 5 ug/mL, BioLegend #313206), APC anti-human CD338 (ABCG2) antibody (clone 5D3, 5 ug/mL, BioLegend #332020), CD133/2 Antibody, anti-human (APC, clone 293C3, 10 ug/mL, Miltenyi Biotec #130-113-184), APC anti-human Ganglioside GD2 antibody (clone 14G2a, 25 ug/mL, BioLegend #357306), CD87 Antibody, anti-human (APC, clone VIM5, 10 ug/mL, Miltenyi Biotec #130-099-456), APC anti-human CD44 antibody (clone BJ18, 25 ug/mL, BioLegend #338806), and CD166 antibody, anti-human, REAfinity (APC, clone REA442, 10 ug/mL, Miltenyi Biotec #130-119-769) as well as murine antibodies PE/Cyanine7 anti-mouse CD133 antibody (clone 315-2C11, 10 ug/mL, BioLegend #141210), ABCG2 Antibody (B-1) Alexa Fluor® 790 (10 ug/mL, Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-377176), and PerCP anti-mouse CD117 (c-kit) antibody (clone 2B8, 25 ug/mL, BioLegend #105822).

Western blotting

Whole-cell lysates were prepared with cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, #9803), PMSF (Sigma-Aldrich), Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail 2 (Sigma-Aldrich, P5726) and 3 (Sigma-Aldrich, P0044), briefly sonicated, rotated for 15 minutes at 4°C, centrifuged for 10 minutes, and then supernatant was removed and protein concentration was quantified by Bradford assays. Lysates were separated on 10% or 4%–12% Bis-Tris gels (Life Technologies), transferred to a PVDF membrane, blocked in 5% non-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline and Tween-20 (TBS-T), and blotted using standard protocols. Membranes were typically incubated at 4°C overnight in primary antibody, washed x 3 in TBS-T, then incubated in 1:2,000 diluted HRP-labeled secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 hour, washed an additional x 3 with TBS-T, and then developed with a chemiluminescent reagent (SuperSignal West Femto, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The following primary antibodies were used: β-Actin (1:5,000, Cell Signaling Technology #4967), N-MYC (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology #9405), Anti-glypican-2 Antibody (F5, 1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-393824), Cleaved Caspase-3 (Asp175, 5A1E, 1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology #9664), Cleaved PARP1 (Asp214, 1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology #9541), Phospho-Histone H2A.X (Ser139, γH2AX, 1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology #2577), Anti-c-Myc (Y69, 1:1,000, Abcam ab32072), and Anti-Pan-Myc (EPR18863, 1:1,000, Abcam ab195207).

Lentiviral preparation and transduction and DNA transfection

pLKO.1 lentiviral shRNA plasmids targeting GPC2 and MYCN or a non-targeting control (NTC) shRNA were obtained from Sigma MISSION shRNA consortium: shGPC2-2 (2), TRCN0000220037; shGPC2-4 (4), TRCN0000147974; shMYCN-1 (1), TRCN00000358381; shMYCN-5 (5), TRCN0000020695; shMYCN-6 (6), TRCN0000020696; shMYCN-7 (7), TRCN0000020697; and shNTC (C; SHC002, MISSION® pLKO.1-puro non-mammalian shRNA control plasmid) and were transfected along with pMD2.G (encoding envelope plasmid VSV-G) and psPAX2 (packaging plasmid) into HEK293T cells utilizing FuGENE® 6. The pMD2.G and psPAX2 plasmids were a kind gift from the laboratory of Dr. Robert Schnepp. The virus-containing supernatant was collected 48 and 72 hours after transfection and filtered with 0.45 μM nitrocellulose membranes. To increase transduction efficiency, virus was added to cells in the presence of 8 μg/mL polybrene (Sigma). Media was changed the next day and puromycin (Sigma) was typically added for selection for at least 48 hours prior to further assaying.

For luciferase transduced cells, lentivirus was produced in a similar manner utilizing a pLenti CMV Puro LUC vector (w688-1), which was a gift from Eric Campeau48 and was purchased via Addgene (plasmid #17477). For GPC2, ΔHS GPC2, or murine Gpc2 isogenic cell line engineering, lentivirus was generated from GPC2, ΔHS GPC2, murine Gpc2, and empty pLENTI CMV Puro vectors as described above and lentivirus-containing supernatants were used to transduce indicated cells followed by antibiotic selection in puromycin.

For transfection experiments, HEK293T cells were transfected with either a human GPC2, human ΔHS GPC2, or murine Gpc2 pLenti CMV puro vector or the pLenti CMV puro DEST vector using Fugene® 6 according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega). After 3-4 days, cells were collected for analysis by western blot and flow cytometry and in parallel, plated for D3-GPC2-PBD ADC cytotoxicity assays as described below.

Cell proliferation assays

SCLC cells were transduced with GPC2 targeting shRNAs as above and after 48-72 hours, GPC2 depleted or control shNTC transduced cells were plated in at least triplicate in a 96-well plate. After 96 hours of additional growth, luminescence was measured with a CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions in a GloMax plate reader (Promega) and luminescence was quantified relative to shNTC transduced cells.

Bystander cytotoxicity assays

Cells were treated with the D3-GPC2-PBD ADC for 6 days at which point the plates were read for luminescence using either a CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assays (Promega) or a ONE-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega) in a GloMax plate reader (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For CellTiter-Glo® exposed cells, the expected cytotoxicity was estimated utilizing the vehicle normalized luminescence values of each of the cells treated alone and accounting for the dilution factor. The % excess cytotoxicity was estimated by subtracting the vehicle normalized actual luminescence values from the expected vehicle normalized luminescence values. The ONE-Glo Luciferase Assay System was utilized according to manufacturer’s instructions and luminescence values were normalized to vehicle treated cells.

Isolation and preparation of D3-GPC2-IgG1

A naive human Fab phage display library constructed from peripheral blood B cells of 50 healthy donors was used for selection of Fabs against purified recombinant GPC2 ectodomain (R&D Systems, Inc., #2304) as previously described.62 Briefly, the isolated Fabs were expressed, purified, and tested for binding to the GPC2 ectodomain through ELISA and the best binder, designated as D3-GPC2-Fab, was converted to a full-length human IgG1. The full length IgG1 DNA construct was transiently transfected into FreeStyle™ 293-F cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #R79007) for antibody production and the D3-GPC2-IgG1 was purified on a protein A column.

D3-GPC2-IgG1 internalization

Cells were plated on an Incucyte ZOOM live-cell monitoring system (Essen Bioscience, Inc.) and 5 μg/mL of D3-GPC2-IgG1-Red (generated using the IncuCyte® FabFluor pH Red antibody labeling reagent [# 4722] and D3-GPC2-IgG1 according to the manufacturer’s instructions) was added after 1 day. Treated wells of cells were quantified for red fluorescence (total object area) after background subtraction using Top-Hat and normalized to the % phase confluence of the identical cells.

ADCC studies

PBMCs and NK cells collected from healthy donors were purchased from the University of Pennsylvania Human Immunology Core facility. Target neuroblastoma cells (NB-EbC1 or SMS-SAN) were plated for 1 day, at which point PBMCs or NK cells were added immediately after the addition of either an isotype control human IgG1 (BioXCell, #BE0297), D3-GPC2-IgG1, or GD2 targeting dinutuximab antibody. Target cell lysis was measured either in real-time on an RT-CES system or by LDH quantification after 24 hours using an LDH-Glo™ Cytotoxicity Assay Kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. LDH concentrations were calculated from a standard curve and the % cytotoxicity normalized to the concentration of LDH released in the experimental sample compared to that of the GD2 targeting dinutuximab positive control (considered 100% cytotoxicity) according to the below equation:

Preparation of D3-GPC2-PBD

The purified D3-GPC2-IgG1 was directly used for glycan-based site-specific modification and conjugation as previously described12,63 except that C2-Azide-Galacotose was used as substrate for the Fc-glycan modification. Briefly, DBCO-PEG4-PBD was used as the payload for the conjugation following the click chemistry-based approach. To maintain solubility of the DBCO-linker-PBD, the azide-attached antibody itself was diluted with propylene glycol to a final concentration of 33%. The solution of DBCO-linker-PBD in propylene glycol was added to the antibody solution with a drug-to-antibody mole ratio of approximately 4:1. The final concentration of propylene glycol in the conjugation reaction was 50%. The reaction was allowed to proceed for at least 4 hours at room temperature and purified by size exclusion chromatography and concentrated in PBS.

D3-GPC2-PBD cytotoxicity and apoptosis assays

The cytotoxicity of D3-GPC2-PBD and free PBD Dimer (Levena Biopharma) was tested in a panel of cell lines including native neuroblastoma cell lines (NBL-SRPMI/NB, SK-N-SHRPMI/NB), stably transduced isogenic GPC2 cell lines (Kelly/SH-SY5Y GPC2/ΔHS GPC2), HEK293T cells transfected with human GPC2, ΔHS GPC2 or murine Gpc2 cDNAs, and murine neuroblastoma isogenic 9464D-Gpc2 cells. Cells were plated on Day 1 in a 96-well plate and on Day 2, serial dilutions of D3-GPC2-PBD or free PBD were added to duplicate or triplicate wells. After 4 days, cell viability was determined using a CellTiter-Glo® Assay (Promega) in a GloMax plate reader (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Luminescence values were normalized to vehicle treated wells and data were analyzed in GraphPad Prism software Version 5.01 to calculate IC50s.

For caspase-3/-7 activity levels, cells were treated as above with D3-GPC2-PBD and Caspase Glo®-3/-7 Assays (Promega) were utilized according to the manufacturer’s instructions at the indicated time points. Each ADC dose was quantified relative to vehicle treated cells and further normalized to the cell number using CellTiter-Glo® assay luminescence values performed in parallel as above.

Heparanase treatment of neuroblastoma cell lines