Abstract

Background:

Short cervix at mid-gestation, the presence of intra-amniotic debris, and cervical funneling are risk factors for preterm birth (PTB), however cervical length (CL) measurements and cutoffs are not well documented among pregnant patients of different gestational ages (GA) and self-reported races and ethnicities.

Objective:

To describe the distribution of CL, and frequency of funneling and debris, at mid-gestation in nulliparous women by gestational age (GA) and race/ethnicity.

Study Design:

Secondary analysis of screening data from a multicenter treatment trial of singleton nulliparous patients with short cervix, conducted at 14 geographically distribued, university affiliated medical centers in the U.S. Singleton nulliparous patients with no known risk factors for PTB were screened for trial participation and asked to undergo a transvaginal ultrasound to measure CL by a certified sonographer. The distribution of CL and the frequency of funneling and debris, were assessed for each GA week (16 to 22 weeks) and stratified by self-reported race and ethnicity, which for this study were catgorized as White, Black, Hispanic and other. Patients enrolled in the randomized trial were excluded from this analysis.

Results:

12,407 nulliparous patients were included in this analysis. The racial/ethnic distribution of study participants was as follows: White 41.6%, Black 29.6%, Hispanic 24.2%, and others 4.6%. The 10th percentile CL for the entire cohort was 31.1 mm, and when stratified by race and ethnicity, 31.9 mm for White, 30.2 mm for Black, 31.4 mm for Hispanic, and 31.2 mm for patients of other race and ethnicity (p<0.001). At each GA, the CL corresponding to tenth percentile was shorter in Black patients. The 25 mm value commonly used to define a short cervix, and thought to represent the 10th percentile, ranged from 1.3 to 5.4 percent across GA weeks and 1.0 to 3.8 percent across race and ethnicity groups. Black patients had the highest rate of funneling (2.6%), whereas Hispanic and Black patients had higher rates of intra-amniotic debris compared with White and other patients (p<0.001).

Conclusions:

Black patients had shorter CL and higher rates of debris and funneling compared with White patients. The racial and ethnic disparities in sonographic mid-trimester cervical findings may provide insight into the racial disparity in preterm birth rates in the US.

Keywords: short cervix, intraamniotic debris, cervical funneling, preterm birth, race, ethnicity

Condensation:

We describe the distribution of cervical lengths and rates of funneling and debris in nulliparous US women per gestational age, race, and ethnicity.

Introduction

Preterm birth (PTB) remains a major public health issue, with estimated annual cost of more than $26 billion.1–4 Despite advancements in neonatology and obstetrical care, the rate of PTB itself has not improved substantially over the past decades, and currently complicates more than 10% of pregnancies in the U.S.1,2 Additionally, PTB remains a leading cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality worldwide, accounting for 60% to 80% of deaths of infants without congenital anomalies.1,5 Moreover, it is estimated that PTB accounts for more than half of childhood blindness and a third of cerebral palsy and neurodevelopmental delay, and has been increasingly implicated in the development of chronic adult conditions in the offspring.6–12 There is a marked maternal racial and ethnic disparity in preterm-related infant mortality and morbidity, with 44% of non-Hispanic Black infant deaths attributed to PTB related causes, a 3-times higher rate compared with non-Hispanic White infants.13

Having a short cervix has emerged as a major risk factor for PTB and many, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine, and several health care systems have supported cervical length screening of both low- and high-risk pregnant patients in order to identify those at greatest risk for PTB, who may benefit from interventions, such as progesterone or cerclage.14–16 However, controversies exist on the best cervical length cutoff to be used to trigger those interventions, since the cutoffs to define a short cervix, that were used in various PTB prevention studies have not been consistent.15–25 Besides short cervix, other findings obtained on transvaginal ultrasound, which are associated with increased risk of PTB, include the presence of intra-amniotic sludge (or debris) at the internal os and cervical funneling.26

Cervical length, funneling, and the presence of debris appear to vary by gestational age (GA), plurality, and, although not well documented, race and ethnicity.19,27 Therefore, our objective in this study is to describe the variation and distribution of mid-trimester cervical lengths and other findings in an ethnically diverse population of pregnant patients with no known risk factors for preterm birth and singleton gestations in the U.S.

Methods

Study Design

We performed a secondary analysis of screening data collected from a multicenter double blind, placebo controlled trial of asymptomatic patients between 16 0/7 and 22 3/7 weeks of gestation with a singleton gestation and short cervix who were randomized to weekly intramuscular injections of either 250 mg of 17 hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17OHP) or placebo for the prevention of PTB (SCAN trial).28 Unselected nulliparous patients with singleton pregnancies, presenting for routine prenatal care visit, underwent a screening transvaginal ultrasound to measure CL by a certified sonographer, using a standardized protocol. Those with a CL < 30 mm were approached for participation in the trial. A cutoff of 30 mm was used as it was thought to represent the 10th to 25th percentile in the mid-trimester for nulliparous patients in the US, who are at clinically increased risk of PTB once their cervix is below this threshold.28–30 This trial was conducted between April 2007 and May 2011 at 14 centers of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) – Maternal Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network. Institutional review board approval for the trial was obtained from all participating clinical sites and the data-coordinating center.

The full methods and results of the primary study have been previously reported. For this secondary analysis, we included all patients with singleton, non-anomalous gestations randomly selected for screening in the SCAN trial. We excluded patients with known uterine or cervical anomalies, prior cervical surgery, or who at the time of screening had or planned to have a cerclage, already received progesterone, or had prolapsed or premature rupture of membranes. For this analysis, we excluded patients who were referred to participate in the SCAN trial because a short cervix was found. Few (n=109, 0.8%) patients randomly selected for screening whose CL was just above 30 mm, had another cervical length measurement screen repeated at a later time, as long as the patient remained eligible for the trial. Repeat cervical length exams were excluded from this analysis.

Study outcomes

For the study, our primary outcome was cervical length measured using an endovaginal ultrasound, as previously described.30 Secondary outcomes included the overall rates of funneling and debris in this unselected population. Cervical funneling was defined as “protrusion of the amniotic membranes ≥ 3 mm into the internal os, as measured from the midpoint of the funnel to the midpoint of the internal os”, and intra-amniotic debris adjacent to the cervix was defined as “areas of increased echodensity within the amniotic cavity that are variable in shape and size, and that move or float away in response to pressure on the abdomen or probe”.28

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC). Race and ethnicity were self-reported and categorized in accordance with the NIH categorization of ethnicity (Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic) and race (Black or African American, White, Asian, native Hawaiian, American Indian and others). Due to limited number of participants precluding meaningful analyses, we broadened the “others” category to include Asian, native Hawaiian, American Indian, and those who reported more than one race, or with unknown race or ethnicity. According, for this analysis, race and ethnicity are reported as Black, White, Hispanic, and other. Since data for this analysis were obtained from screening logs, only limited demographic information on participants is available, as was regulated by local Institutional Review Boards (IRBs). In addition, the last GA week (22 weeks) included patients who underwent ultrasound exams at 22 0/7– 22 3/7 weeks only. Standard descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation, or median and interquartile range) were used to summarize continuous variables and frequency and percentage for categorical variables. CL was measured and reported as a continuous variable. We then calculated the mean, standard deviation, and 5th, 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 90th and 95th percentiles. We used quantile regression models to compare CL distributions by race and ethnicity at the 10th percentile. Linear regression was used to compare differences in CL distributions at each week gestation. The distribution of CL, and the rates of intra-amniotic debris and cervical funneling were determined for the entire cohort and then for each completed GA (16 to 22 weeks) and self-reported race and ethnicity. We then constructed CL reference ranges by GA specific for race and ethnicity. We used the chi-square test and Cochran-Armitage trend test, for categorical variables. All tests were two-tailed and P < 0.05 was used to define statistical significance.

Results

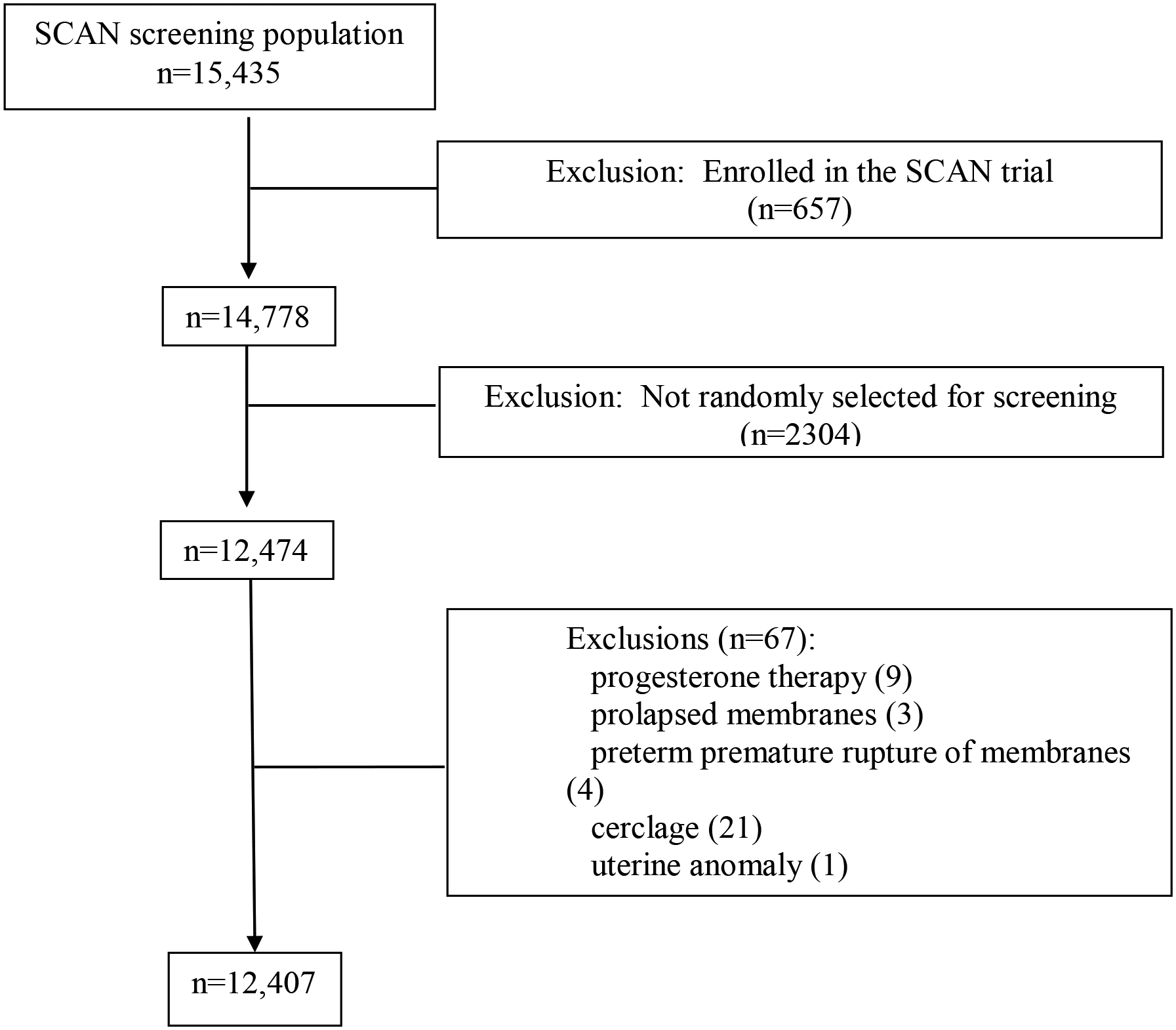

Out of 15,435 patients screened during the study, 12,407 (80.4%) met inclusion criteria for this analysis. (Figure 1) The ethnic and racial distribution of screened patients was as follows: White 41.6%, Black 29.6%, Hispanic 24.2%, and others 4.6%. The CL distribution for the entire cohort, per race and ethnicity, and for each GA week are described in Table 1. The details of the CL distribution for each GA week and for race and ethnicity are included in Table 2 (and supplementary Table 1 and supplementary Figures 1 and 2). Overall, the CL distributions were shorter in Black patients at each GA, compared with White patients. Differences in mean CL for Black patients compared with White were significantly different at 18 to 21 weeks (p < 0.001).

Figure 1:

Study flow chart.

Table 1.

Overall cervical length (in mm) distribution for the entire cohort and per race, ethnicity, and weeks of gestational age.

| Mean ± SD | 5th | 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 90th | 95th | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n=12,407) | 38.9±7.5 | 29.2 | 31.1 | 34.1 | 38.2 | 43.0 | 48.0 | 51.7 |

| Distribution per race and ethnicity | ||||||||

| White (n=5,161) | 39.9±7.4 | 30.4 | 31.9 | 34.9 | 39.0 | 44.0 | 49.3 | 53.4 |

| Black (n=3,667) | 37.4±7.6 | 26.6 | 30.2 | 32.8 | 37.0 | 41.4 | 46.4 | 49.8 |

| Hispanic (n=3,005) | 38.9±7.2 | 30.1 | 31.4 | 34.2 | 38.2 | 43.2 | 47.6 | 50.4 |

| Other (n=574) | 39.6±7.6 | 30.2 | 31.2 | 34.6 | 38.7 | 44.1 | 49.1 | 54.3 |

| Distribution per week gestational age | ||||||||

| 16 weeks (n=625) | 38.2±6.8 | 30.5 | 31.7 | 33.8 | 37.2 | 42.1 | 46.6 | 49.2 |

| 17 weeks (n=1,169) | 38.7±7.1 | 30.1 | 31.2 | 34.0 | 37.9 | 42.9 | 47.3 | 50.7 |

| 18 weeks (n=2,728) | 39.0±7.1 | 30.0 | 31.2 | 34.3 | 38.2 | 43.0 | 47.9 | 51.2 |

| 19 weeks (n=2,956) | 39.0±7.5 | 29.5 | 31.2 | 34.3 | 38.3 | 43.1 | 48.3 | 52.0 |

| 20 weeks (n=3,106) | 39.6±7.7 | 29.7 | 31.4 | 34.6 | 38.8 | 43.8 | 49.1 | 53.3 |

| 21 weeks (n=1,363) | 38.1±8.2 | 26.9 | 30.5 | 33.3 | 37.8 | 42.6 | 47.6 | 51.0 |

| 22 weeks (n=460) | 37.1±7.6 | 24.3 | 29.3 | 33.1 | 37.1 | 41.8 | 45.9 | 48.5 |

Table 2.

Cervical length (in mm) distribution for each gestational age week and race and ethnicity.

| 16 weeks | Mean ± SD | 5th | 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 90th | 95th |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (219) | 38.1±6.2 | 30.9 | 31.9 | 34.2 | 36.9 | 41.7 | 46 | 49 |

| Black (110) | 37.7±8.6 | 25.3 | 30.5 | 33 | 36.9 | 42.2 | 47.1 | 53.4 |

| Hispanic (282) | 38.5±6.6 | 31.1 | 31.7 | 33.8 | 37.5 | 42.7 | 46.9 | 48.7 |

| Other (14) | 39.6±4.7 | 32.8 | 33 | 35.6 | 40 | 43.9 | 45.7 | 46 |

| 17 weeks | ||||||||

| White (399) | 39.2±7.0 | 30 | 31.4 | 34.4 | 38.2 | 43.5 | 48.2 | 51.4 |

| Black (304) | 38.3±7.3 | 28.1 | 30.8 | 33.4 | 38.1 | 42.4 | 47.8 | 50.7 |

| Hispanic (425) | 38.5±7.0 | 30.3 | 31.4 | 33.8 | 37.6 | 42.8 | 46.4 | 48.8 |

| Other (41) | 38.7±8.5 | 30.5 | 30.7 | 32.6 | 37.1 | 41.4 | 46.5 | 55.8 |

| 18 weeks | ||||||||

| White (1074) | 39.8±7.3 | 30.4 | 31.6 | 34.9 | 39 | 43.9 | 49 | 52.8 |

| Black (935) | 38.1±7.0 | 28.4 | 30.5 | 34 | 37.6 | 41.8 | 46.9 | 50 |

| Hispanic (627) | 39.0±6.7 | 30.4 | 31.6 | 34.1 | 38 | 43.3 | 47.5 | 50 |

| Other (92) | 39.5±7.3 | 28.9 | 30.5 | 34.5 | 39.1 | 44.5 | 49 | 52.6 |

| 19 weeks | ||||||||

| White (1294) | 40.2±7.5 | 30.3 | 32 | 35.1 | 39.2 | 44.1 | 49.8 | 53.7 |

| Black (865) | 37.1±7.1 | 27 | 30.3 | 32.8 | 37 | 41 | 45.5 | 48.6 |

| Hispanic (660) | 39.2±7.3 | 29.9 | 31.5 | 34.6 | 38.5 | 43.9 | 48.1 | 51.1 |

| Other (137) | 39.8±7.9 | 29.1 | 31 | 34 | 38.5 | 44.3 | 49.1 | 54.7 |

| 20 weeks | ||||||||

| White (1467) | 41.0±7.6 | 31.1 | 32.4 | 35.7 | 40 | 45 | 50.6 | 55.6 |

| Black (844) | 37.3±7.5 | 26 | 30 | 32.5 | 36.7 | 41.4 | 46.4 | 49.9 |

| Hispanic (594) | 39.4±7.4 | 29.9 | 31.4 | 34.7 | 38.8 | 43.7 | 48.2 | 51.7 |

| Other (201) | 39.2±7.6 | 28.1 | 31.6 | 34.4 | 38.5 | 43.6 | 49.1 | 52.8 |

| 21 weeks | ||||||||

| White (531) | 38.8±7.4 | 28.5 | 31.1 | 33.8 | 38.2 | 43 | 48.2 | 52 |

| Black (452) | 36.4±9.1 | 22.4 | 27.6 | 31.5 | 36.1 | 41.2 | 45.6 | 49.3 |

| Hispanic (306) | 38.9±7.9 | 30 | 31.2 | 34.6 | 38.6 | 43 | 48.1 | 50.1 |

| Other (74) | 40.6±7.3 | 30.5 | 32 | 35.5 | 39.8 | 45.2 | 49.1 | 55 |

| 22 weeks | ||||||||

| White (177) | 37.1±7.2 | 26.4 | 29.7 | 33.2 | 37 | 41.7 | 46.1 | 48.4 |

| Black (157) | 36.1±8.3 | 23.6 | 27.4 | 32.4 | 36 | 40.6 | 45.7 | 49.3 |

| Hispanic (111) | 37.9±7.3 | 24 | 30 | 34.2 | 39 | 42.1 | 45.8 | 48.2 |

| Other (15) | 41.4±6.8 | 32.1 | 33.4 | 37.5 | 41.4 | 43 | 55 | 55.5 |

In general, CLs differed as pregnancy progressed by GAs from 16 to 22 weeks. Specifically, the cutoffs for the 5th and 10th percentiles decreased with advancing GAs, and that decline was more pronounced in Black patients. The 10th percentile CL for the entire cohort was 31.1 mm. When stratified by race and ethnicity, the 10th percentile for CL was as follows: 31.9 mm for White, 30.2 mm for Black, 31.4 mm for Hispanic, and 31.2 mm for patients of other race and ethnicity (p<0.001 Black vs. all other races and ethnicities). (Table 1) In addition, the commonly used 25 mm cutoff (which is thought to represent the 10th percentile) ranged between 1.3 to 5.4 percent across all weeks gestation and from 1.0 to 3.8 percent for any race and ethnicity (Table 3)

Table 3:

Frequency (%) corresponding to cervical length cutoffs of 15, 25 and 30 mm per each race and ethnicity and GA (weeks)

| Cervical length cutoff | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Race and Ethnicity | 15 mm | 25 mm | 30 mm |

| White | 0.2 | 1.0 | 3.9 |

| Black | 0.9 | 3.8 | 9.0 |

| Hispanic | 0.5 | 1.7 | 4.5 |

| Other | 0.5 | 1.2 | 4.5 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | |||

| 16 | 0.5 | 1.8 | 3.0 |

| 17 | 0.2 | 1.7 | 4.8 |

| 18 | 0.2 | 1.3 | 4.6 |

| 19 | 0.5 | 1.7 | 5.5 |

| 20 | 0.3 | 1.9 | 5.3 |

| 21 | 1.3 | 3.7 | 8.4 |

| 22 | 2.0 | 5.4 | 10.9 |

Funneling and intra-amniotic debris in this cohort occurred in 1.5% and 4.2% of patients, respectively. Both findings were more common in patients with CL < 30 mm (18.4% funneling and 13.2% debris) compared with those whose CL ≥ 30 mm (0.5% funneling and 3.6% debris; p<0.001 for both). Black patients had the highest rate of funneling (2.6%) compared with patients of other races and ethnicities (p<0.001), whereas Hispanic and Black patients had higher rates of intra-amniotic debris compared with White and other patients (p<0.001). Moreover, the rate of funneling increased (1.0% at 16 weeks to 2.8% at 22 weeks) and intra-amniotic debris decreased (9.3% at 16 weeks and 3.5% at 22 weeks) with GA (p<0.001 for both). (Table 4)

Table 4:

Frequency (%) of cervical funneling and intra-amniotic debris per each gestational age and race and ethnicity

| Working GA (weeks) | Funneling | Debris |

|---|---|---|

| 16 | 1.0 | 9.3 |

| 17 | 1.0 | 6.3 |

| 18 | 1.0 | 5.5 |

| 19 | 1.5 | 3.7 |

| 20 | 1.5 | 2.4 |

| 21 | 2.8 | 2.6 |

| 22 | 2.8 | 3.5 |

| Cochrane-Armitage trend test p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Race and Ethnicity | Funneling | Debris |

| White | 0.5 | 2.8 |

| Black | 2.6 | 4.6 |

| Hispanic | 1.8 | 6.4 |

| Other | 1.9 | 2.1 |

| Chi-square test p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Discussion

Principal Findings

In this large cohort of nulliparous patients, CL measurements and cutoffs varied at different GAs and among patients of different race and ethnicity, with Black patients demonstrating shorter CL and higher rates of debris and funneling compared with White patients.1,2

Results and Research and Clinical implications

In the United States, race and ethnicity are significant risk markers for PTB. For example, in 2018 birth data, non-Hispanic Black patients had a prematurity rate of 14.1%, in comparison with 9.1 % for non-Hispanic White patients. Similarly, the rate of PTB < 34 weeks in non-Hispanic Black patients (4.9%) was more than double that of non-Hispanic White patients (2.3%).1 Even after controlling for typically available demographic and socioeconomic factors (e.g. extremes of maternal age, education, and socioeconomic status) Black patients still have higher rates of PTB compared with White patients.15 The findings from our study showing that Black patients have shorter CL at various GAs and higher rates of debris and funneling, may provide further insight into the racial and ethnic disparities that exist, as it demonstrates that the pathways that lead to PTB are disparate long before the disparity of actual PTB manifests.

A short cervix has emerged as a major risk factor for PTB.2,30–32 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine, and other professional organizations have commented that a cervical length measurement be considered at the time the ultrasound examination is undertaken for fetal anatomic survey at around 18–22 weeks of gestation, and that practitioners who decide to implement such universal CL screening should follow strict guidelines.16 Patients with short cervix, defined as < 20 mm, have been shown to benefit from vaginal progesterone.14,16 Similarly, for patient with prior PTB <34 weeks, serial cervical length screening is recommended starting at 16 weeks, in order to identify those with cervix < 25 mm who may be benefit from cervical cerclage.16,23 While the CL cutoffs were chosen based on prior trials, there is no universal agreement that these cutoffs are the best to overall represent high-risk patients who may benefit from current or future interventions.15,16,19

Various studies have demonstrated that the shorter the cervix is in mid-gestation, the higher is the risk of PTB. However, the cutoff that was used in various studies to define a short cervix has not been consistent (<15 mm, 10–20 mm, < 25 mm, <30 mm), and some prior studies have included multiparous patients, and those with other risk factors for short cervix (prior PTB, cervical surgery).15–25,33 For instance, data from the preterm prediction study of the MFMU (N=2,915) showed that the 50th, 25th, 10th, and 5th percentiles for cervical lengths in singleton patients at 24 weeks are 35, 30, 26, and 22 mm respectively,30 whereas Hibbard et al reported in a cohort of unselected nulliparous and multiparous patients that a CL of 30 mm measured at 16–22 weeks was at the 10th percentile.34 However, data from a Finnish cohort of unselected patients, reported that 30 mm represents only the 3rd percentile at 18–22 weeks.35 On the other hand, data from a high-risk cohort of patients with prior PTB from the U.S. showed that, when measured at 16–18 weeks, CL of 25 mm represents the 7th percentile and 30 mm the 20th percentile.33 Various interventions (or analyses) targeting high-risk patients with short cervix used various cutoffs. In the vaginal progesterone studies, patients were selected based on cutoffs of 15 mm (3rd percentile) by Fonseca et al.,25 10–20 mm by Hassan et al.,21 and 25 mm in the OPPTIMUM study,36 whereas in a secondary analysis, DeFranco et al used a cutoff of 28 mm.37 On the other hand, several prospective studies have been conducted using cervical length as a marker to determine who may best benefit from cerclage placement for the prevention of recurrent PTB.38–42 These cutoffs have included 25 mm by Althuisius et al.,38 and Owen et al.,24 and 15 mm by To et al.42 The variability in the selected cutoffs may explain the different results observed in these studies and support the need to use racial and ethnic and GA specific CL cutoffs, if the goal is to identify patients with a similar post-test probability for preterm birth.

When performing transvaginal ultrasound for CL measurement, additional findings may be noted which may have value in determining the risk of PTB. Two such findings in particular have received attention: the presence of intra-amniotic sludge (or debris) at the internal os and cervical funneling. Some studies have shown an association between these findings and PTB while others have not.21–27 Limitations of prior studies include small sample size, a combination of low-risk and high-risk pregnant patients, and a lack of standardized sonographic evaluation. Moreover, the frequency of “intra-amniotic debris” decreased between 16 and 22 weeks from 9.3% to 3.5% which is surprising since at the same time the frequency of funneling increased and the CL was shorter. It is plausible that the association between “debris” early in pregnancy may not have the same clinical significance compared to “debris” that persist at a later gestational age.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study was a secondary analysis of a large contemporary cohort of nulliparous pregnant patients, in which cervical length was measured accoring to a validated protocol. We excluded patients who were referred specifically for short cervix. The latter, along with this multicenter aspect of the study and the geographically and ethnically diverse patient population favors the generalizability of our results. However, as with any observational study, it remains possible selection bias may have confounded our data. Despite our relatively large study, and the diverse settings from which the data were collected, we may have underrepresented racial or ethnic groups at certain GA. In addition, our study was limited by the lack of clinical outcomes for these patients, who were screened for, but not enrolled in, the randomized trial. Thus, only limited data collection was allowed among the screened population by the local IRBs. It is plausible that differences among ethnic groups may have been confounded by differences in maternal weight and height.43 In addition, since some of the patients from our cohort may have had spontaneous preterm birth, it is possible that the resulting cut-offs obtained in our analysis normalize pathology instead of allowing to find that more Black women are at risk, had it been that all our data were collected from women who delivered at term.43 Other study limitations include the focus on CL descriptive data without any mechanistic explanation. In addition, the last GA week (22 weeks) was limited by only including patients who underwent ultrasdound exams at 22 0/7– 22 3/7, and thus findings from that GA may not be representatibe of the entire GA week. Moreover, since this is not a longitudinal study, weekly differences in percentiles may have been related to differences in maternal characteristics of women in each gestational age bin, such as weight and height, as suggested in other studies.43 Last this study was limited to patients with singleton gestations, and cannot be extrapolated to patients with twins.

Conclusions

In conclusion, in this large cohort of nulliparous US pregnant patients without additional risk factors for short cervix, we determined the CL measurements and cutoffs at different GA and between race and ethnicity. This study demonstrated that Black patients have shorter CL and higher rates of debris and funneling compared with White patients. Our findings may provide at least partial insight that factors on the pathway to PTB are differentially present long before the racial disparity in PTB manifests. This secondary analysis will provide valuable information that will help researchers in designing future trials, and clinicians in better identifying, counseling and treating high-risk pregnant patients.

Supplementary Material

AJOG at a Glance.

- Why was this study conducted?

- Short cervix at mid-gestation, the presence of intra-amniotic debris, and cervical funneling are risk factors for preterm birth.

- Cervical length measurements and cutoffs, and the frequency of intra-amniotic debris, and cervical funneling are not well documented among pregnant patients of different gestational ages and self-reported races and ethnicities.

- What are the key findings?

- In this secondary analysis of screening data from a randomized trial, we describe the distribution of mid-gestation cervical lengths and other sonographic findings in a large cohort of nulliparous US patients by gestational age, race and ethnicity.

- Black patients demonstrate shorter cervical length as well as higher rates of debris and funneling compared with White patients

- What does this study add to what is already known?

- The racial and ethnic differences in sonographic mid-trimester cervical findings may provide insight into the racial disparity in preterm birth rates in the US.

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank Gail Mallett, R.N., B.S.N., C.C.R.C. for protocol development and coordination between clinical research centers; Vinay Bhandaru, MS for statistical programming; and Elizabeth A. Thom, Ph.D., Catherine Y. Spong, M.D., Jay D. Iams, M.D., and George Saade, M.D. for protocol development and oversight.

Funding Sources: The project described was supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) [HD21410, UL1 RR024153; UL1 TR000005; HD27869, HD27915, HD27917, HD34116, HD34208, 5UL1RR025764, U10HD36801, HD40500, HD40512, HD40544, M01 RR00080, UL1 RR024989 (NCRR), HD40545, HD40560, HD40485, HD53097, HD53118]. Comments and views of the authors do not necessarily represent views of the NIH.

Appendix:

In addition to the authors, other members of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network are as follows:

University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX – J. Moss, G. Saade, A. Salazar, G. Hankins, G. Olson, A. Jackson, C. Sutherland

Northwestern University, Chicago, IL – A. Peaceman, M. Dinsmoor (NorthShore University HealthSystem), G. Mallett, J. Senka (NorthShore University HealthSystem)

The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH – F. Johnson, J. Iams, D. Cline, C. Latimer, S. Frantz, S. Fyffe, P. Shubert (St. Ann’s), L. Gerwig (St. Ann’s)

Case Western Reserve University-MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, OH – C. Milluzzi, W. Dalton, J. Russo, S. Myers, T. Waters, T. Dotson

University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL – W. Andrews, A. Northen, J. Sheppard, J. Grant, D. Rouse

Brown University, Providence, RI – D. Allard, J. Hunt, J. Tillinghast, M. Bethelemy, D. Gardner, C. Duquette

Wayne State University, Detroit, MI – N. Hauff, G. Norman, M. King (RDMS), D. Allen (RDMS), T. Smith

Columbia University, New York, NY – R. Miller, S. Bousleiman, L. Plante (Drexel), C. Tocci (Drexel), A. Ranzini (St. Peter’s), M. Lake (St. Peter’s), M. Hoffman (Christiana), S. Lynch (Christiana)

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX –J. Dashe, K. Leveno (deceased), L. Moseley, J. Kingsbery, V. Bludau, R. Benezue

The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston-Children’s Memorial Hermann Hospital, Houston, TX – F. Ortiz, P. Givens, B. Rech, C. Moran

University of Utah Health Sciences Center, Salt Lake City, UT – P. Reed (deceased), K. Hill, M.W. Varner, M. S. Esplin, A. Weaver (McKay-Dee), S. Alexander (LDS Hospital), D. Thompson-Garbrecht (Intermountain Medical Center), J. Miller (UVRMC)

Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR – R. Acosta (Providence Sacred Heart Medical Center), C. Flores (Providence Sacred Heart Medical Center), M. Ricon, W. Smith (Kaiser Permanente), S. Butcher (Kaiser Permanente), S. Segel, L. Pereira

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC – K. Dorman, K. Pena-Centeno, K. Clark, S. Timlin

University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA – M.H. Birkland, H. Simhan, P. Cotroneo, R. Zubic, D. Nowinski

The George Washington University Biostatistics Center – E. Thom, S. Gilbert, A. Lozitska

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, MD – C. Spong, S. Tolivaisa

MFMU Network Steering Committee Chair (Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC) – J. P. VanDorsten

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest

Presentation Information: Presented at the 35th Annual Meeting of the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine, San Diego, CA.

References:

- 1.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK. Births in the United States, 2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2019(346):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371(9606):75–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williamson DM, Abe K, Bean C, Ferre C, Henderson Z, Lackritz E. Current research in preterm birth. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17(10):1545–1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Societal costs of preterm birth. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saigal S, Doyle LW. An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. Lancet. 2008;371(9608):261–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jarjour IT. Neurodevelopmental outcome after extreme prematurity: a review of the literature. Pediatr Neurol. 2015;52(2):143–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubens CE, Sadovsky Y, Muglia L, Gravett MG, Lackritz E, Gravett C. Prevention of preterm birth: harnessing science to address the global epidemic. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(262):262sr265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Romero R, Dey SK, Fisher SJ. Preterm labor: one syndrome, many causes. Science. 2014;345(6198):760–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyle AK, Rinaldi SF, Norman JE, Stock SJ. Preterm birth: Inflammation, fetal injury and treatment strategies. J Reprod Immunol. 2017;119:62–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blencowe H, Lawn JE, Vazquez T, Fielder A, Gilbert C. Preterm-associated visual impairment and estimates of retinopathy of prematurity at regional and global levels for 2010. Pediatr Res. 2013;74 Suppl 1:35–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers LK, Velten M. Maternal inflammation, growth retardation, and preterm birth: insights into adult cardiovascular disease. Life Sci. 2011;89(13–14):417–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hack M, Schluchter M, Andreias L, et al. Change in prevalence of chronic conditions between childhood and adolescence among extremely low-birth-weight children. JAMA. 2011;306(4):394–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matthews TJ, MacDorman MF, Thoma ME. Infant Mortality Statistics From the 2013 Period Linked Birth/Infant Death Data Set. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(9):1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Committee opinion no. 522: incidentally detected short cervical length. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(4):879–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics TACoO, Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 130: prediction and prevention of preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(4):964–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Electronic address pso, McIntosh J, Feltovich H, Berghella V, Manuck T. The role of routine cervical length screening in selected high- and low-risk women for preterm birth prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(3):B2–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nicolaides KH, Syngelaki A, Poon LC, et al. A Randomized Trial of a Cervical Pessary to Prevent Preterm Singleton Birth. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(11):1044–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hui SY, Chor CM, Lau TK, Lao TT, Leung TY. Cerclage pessary for preventing preterm birth in women with a singleton pregnancy and a short cervix at 20 to 24 weeks: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Perinatol. 2013;30(4):283–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Publications Committee waoVB. Progesterone and preterm birth prevention: translating clinical trials data into clinical practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(5):376–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romero R, Nicolaides K, Conde-Agudelo A, et al. Vaginal progesterone in women with an asymptomatic sonographic short cervix in the midtrimester decreases preterm delivery and neonatal morbidity: a systematic review and metaanalysis of individual patient data. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(2):124 e121–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hassan SS, Romero R, Vidyadhari D, et al. Vaginal progesterone reduces the rate of preterm birth in women with a sonographic short cervix: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38(1):18–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berghella V, Rafael TJ, Szychowski JM, Rust OA, Owen J. Cerclage for short cervix on ultrasonography in women with singleton gestations and previous preterm birth: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(3):663–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iams JD, Berghella V. Care for women with prior preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(2):89–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Owen J, Hankins G, Iams JD, et al. Multicenter randomized trial of cerclage for preterm birth prevention in high-risk women with shortened midtrimester cervical length. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(4):375 e371–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fonseca EB, Celik E, Parra M, Singh M, Nicolaides KH, Fetal Medicine Foundation Second Trimester Screening G. Progesterone and the risk of preterm birth among women with a short cervix. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(5):462–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saade GR, Thom EA, Grobman WA, et al. Cervical funneling or intra-amniotic debris and preterm birth in nulliparous women with midtrimester cervical length less than 30 mm. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018;52(6):757–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berghella V, Bega G, Tolosa JE, Berghella M. Ultrasound assessment of the cervix. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2003;46(4):947–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grobman WA, Thom EA, Spong CY, et al. 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate to prevent prematurity in nulliparas with cervical length less than 30 mm. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(5):390 e391–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldenberg RL, Iams JD, Mercer BM, et al. The preterm prediction study: the value of new vs standard risk factors in predicting early and all spontaneous preterm births. NICHD MFMU Network. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(2):233–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iams JD, Goldenberg RL, Meis PJ, et al. The length of the cervix and the risk of spontaneous premature delivery. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal Fetal Medicine Unit Network. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(9):567–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spong CY. Prediction and prevention of recurrent spontaneous preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2 Pt 1):405–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldenberg RL, Iams JD, Mercer BM, et al. The Preterm Prediction Study: toward a multiple-marker test for spontaneous preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185(3):643–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Owen J, Yost N, Berghella V, et al. Mid-trimester endovaginal sonography in women at high risk for spontaneous preterm birth. JAMA. 2001;286(11):1340–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hibbard JU, Tart M, Moawad AH. Cervical length at 16–22 weeks’ gestation and risk for preterm delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(6):972–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taipale P, Hiilesmaa V. Sonographic measurement of uterine cervix at 18–22 weeks’ gestation and the risk of preterm delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92(6):902–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Norman JE, Marlow N, Messow CM, et al. Vaginal progesterone prophylaxis for preterm birth (the OPPTIMUM study): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10033):2106–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DeFranco EA, O’Brien JM, Adair CD, et al. Vaginal progesterone is associated with a decrease in risk for early preterm birth and improved neonatal outcome in women with a short cervix: a secondary analysis from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30(5):697–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Althuisius SM, Dekker GA, Hummel P, Bekedam DJ, van Geijn HP. Final results of the Cervical Incompetence Prevention Randomized Cerclage Trial (CIPRACT): therapeutic cerclage with bed rest versus bed rest alone. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185(5):1106–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Belej-Rak T, Okun N, Windrim R, Ross S, Hannah ME. Effectiveness of cervical cerclage for a sonographically shortened cervix: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(6):1679–1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Groom KM, Bennett PR, Golara M, Thalon A, Shennan AH. Elective cervical cerclage versus serial ultrasound surveillance of cervical length in a population at high risk for preterm delivery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;112(2):158–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berghella V, Mackeen AD. Cervical length screening with ultrasound-indicated cerclage compared with history-indicated cerclage for prevention of preterm birth: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(1):148–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.To MS, Alfirevic Z, Heath VC, et al. Cervical cerclage for prevention of preterm delivery in women with short cervix: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363(9424):1849–1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gudicha DW, Romero R, Kabiri D, et al. Personalized assessment of cervical length improves prediction of spontaneous preterm birth: a standard and a percentile calculator. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.