Abstract

Here we describe a biomimetic microsystem that reconstitutes the critical functional alveolar-capillary interface of the human lung. This bioinspired microdevice reproduces complex integrated organ-level responses to bacteria and inflammatory cytokines introduced into the alveolar space. In nanotoxicology studies, this lung mimic revealed that cyclic mechanical strain accentuates toxic and inflammatory responses of the lung to silica nanoparticles. Mechanical strain also enhances epithelial and endothelial uptake of nanoparticulates and stimulates their transport into the underlying microvascular channel. Similar effects of physiological breathing on nanoparticle absorption are observed in whole mouse lung. Mechanically active ‘organ-on-a-chip’ microdevices that reconstitute tissue-tissue interfaces critical to organ function may therefore expand the capabilities of cell culture models, and provide low-cost alternatives to animal and clinical studies for drug screening and toxicology applications.

One of the causes of the high cost of pharmaceuticals and the major obstacles to rapidly identifying new environmental toxins is the lack of experimental model systems that can replace costly and time-consuming animal studies. Although considerable advances have been made in the development of cell culture models as surrogates of tissues and organs for these types of studies (1), cultured cells commonly fail to maintain differentiation and expression of tissue-specific functions. Improved tissue organization can be promoted by growing cells in three-dimensional extracellular matrix (ECM) gels (2); however, these methods still fail to reconstitute structural and mechanical features of whole living organs that are central to their function. In particular, existing model systems do not recreate the active tissue-tissue interface between the microvascular endothelium and neighboring parenchymal tissues where critical transport of fluids, nutrients, immune cells, and other regulatory factors occur, nor do they permit application of dynamic mechanical forces (e.g., breathing movements in lung, shear in blood vessels, peristalsis in gut, tension in skin, etc.) that are critical for the development and function of living organs (3).

Microscale engineering technologies first developed to create microchips, such as microfabrication and microfluidics, enable unprecedented capabilities to control the cellular microenvironment with high spatiotemporal precision and to present cells with mechanical and biochemical signals in a more physiologically relevant context (4–7). This approach has made it possible to microfabricate models of blood vessels (8, 9), muscles (10), bones (11), airways (12), liver (13–16), brain (17, 18), gut (19), and kidney (20, 21). However, it has not yet been possible to engineer integrated microsystems that replicate the complex physiological functionality of living organs by incorporating multiple tissues, including active vascular conduits, and placing them in a dynamic and mechanically relevant organ-specific microenvironment.

To provide the proof-of-principle for a biomimetic microsystems approach, we developed a multifunctional microdevice that reproduces key structural, functional, and mechanical properties of the human alveolar-capillary interface, which is the fundamental functional unit of the living lung. This was accomplished by microfabricating a microfluidic system containing two closely apposed microchannels separated by a thin (10 µm) porous flexible membrane made of poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS). The intervening membrane was coated with ECM (fibronectin or collagen), and human alveolar epithelial cells and human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells were cultured on opposite sides of the membrane (Fig. 1A). Once the cells were grown to confluence, air was introduced into the epithelial compartment to create an air-liquid interface and more precisely mimic the lining of the alveolar air space. The compartmentalized channel configuration of the microdevice makes it possible to manipulate fluid flow, as well as delivery of cells and nutrients, to the epithelium and endothelium independently.

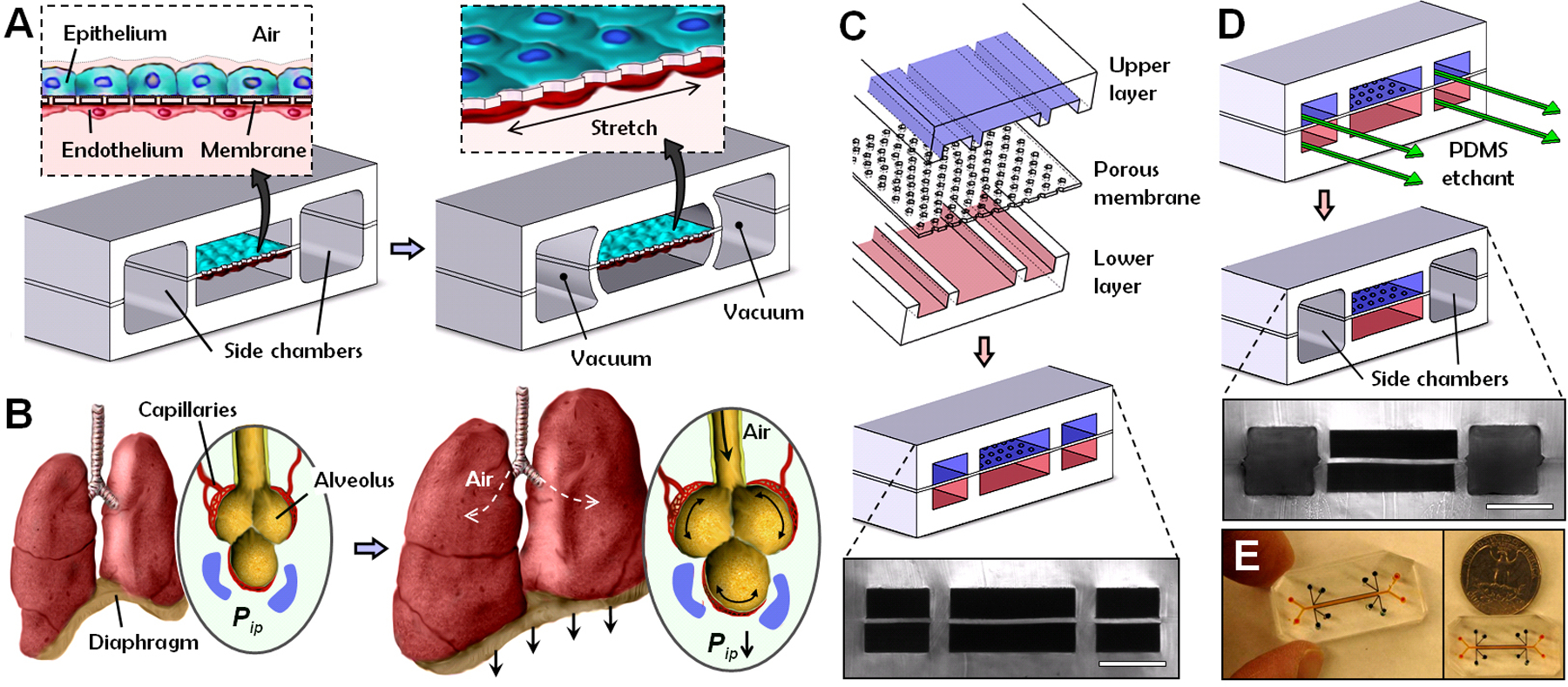

Fig. 1.

Biologically inspired design of a human breathing lung-on-a-chip microdevice. (A) The microfabricated lung mimic device utilizes compartmentalized PDMS microchannels to form an alveolar-capillary barrier on a thin porous flexible PDMS membrane coated with ECM. The device recreates physiological breathing movements by applying vacuum to the side chambers and causing mechanical stretching of the PDMS membrane forming the alveolar-capillary barrier. (B) During inhalation in the living lung, contraction of the diaphragm causes a reduction in intrapleural pressure (Pip), leading to distension of the alveoli and physical stretching of the alveolar-capillary interface. (C) Three PDMS layers are aligned and irreversibly bonded to form two sets of three parallel microchannels separated by a 10 μm-thick PDMS membrane containing an array of through-holes with an effective diameter of 10 μm (scale bar, 200 μm). (D) Following permanent bonding, PDMS etchant is flowed through the side channels. Selective etching of the membrane layers in these channels produces two large side chambers to which vacuum is applied to cause mechanical stretching (scale bar, 200 μm). (E) Images of an actual lung-on-a-chip microfluidic device viewed from above.

During normal inspiration, intrapleural pressure decreases, causing the alveoli to expand; this pulls air into the lungs, resulting in stretching of the alveolar epithelium and the closely apposed endothelium in adjacent capillaries (Fig. 1B). We mimicked this sub-atmospheric, pressure-driven stretching by incorporating two larger, lateral microchambers into the device design. When vacuum is applied to these chambers, it produces elastic deformation of the thin wall that separates the cell-containing microchannels from the side chambers; this causes stretching of the attached PDMS membrane and the adherent tissue layers (Fig. 1A, right vs. left). When the vacuum is released, elastic recoil of PDMS causes the membrane and adherent cells to relax to their original size. This design replicates dynamic mechanical distortion of the alveolar-capillary interface caused by breathing movements.

These hollow microchannels were fabricated via soft lithography in conjunction with a new method that utilizes chemical etching of PDMS (22) to form the vacuum chambers. Fabrication begins with alignment and permanent bonding of a 10 μm-thick porous PDMS membrane (containing 10 μm-wide pentagonal pores) and two PDMS layers containing recessed microchannels (Fig. 1C). A PDMS etching solution composed of tetrabutylammonium fluoride and N-methylpyrrolidinone is then pumped through the side channels (Fig. 1D). Within a few minutes, PDMS etchant completely dissolves away portions of the membrane in the side channels, creating two large chambers directly adjacent to the culture microchannels. The entire integrated device is only one to two centimeters in length with the central channels only millimeters in width (Fig. 1E), and thus, it is fully amenable to high density integration into a highly multiplexed microdevice in the future.

Reconstitution of a Functional Alveolar-Capillary Interface

When human alveolar epithelial cells and microvascular endothelial cells were introduced into their respective channels, they attached to opposite surfaces of the ECM-coated membrane and formed intact monolayers composed of cells linked by continuous junctional complexes containing the epithelial and endothelial junctional proteins, occludin and VE-cadherin, respectively (Fig. 2A). These cells remained viable for prolonged periods (> 2 weeks) after air was introduced into the epithelial microchannel and the alveolar cells were maintained at an air-liquid interface (fig. S1). Addition of air to the upper channel resulted in increased surfactant production by the epithelium (Fig. 2B and fig. S1), which stabilizes the thin liquid layer in vitro as it does in whole lung in vivo, such that no drying was observed. This was also accompanied by an increase in electrical resistance across the tissue layers (Fig. 2C), and enhanced molecular barrier function relative to cells cultured under liquid medium (Fig. 2D). These differences in barrier integrity and permeability likely result from strengthening of intercellular junctions in air-liquid interface culture (12), and from the observed changes in pulmonary surfactant production that can influence alveolar-capillary barrier function (23). Moreover, the low level of protein permeability (2.1%/hr for fluorescently-labeled albumin) exhibited by cells cultured at the air-liquid interface (Fig. 2D) closely approximated that observed in vivo (1~2 %/hr; 24). It should be noted that although we mimic the alveolar microenvironment by generating an air-liquid interface in contact with the apical surface of epithelium in our microdevice, there is likely a large variation in the microscale properties of this interface in vivo. Thus, it would be difficult to interpret these results in any way other than functional measures at this time. Our results clearly show that the epithelial cells not only remained viable, but they also increased their surfactant production, enhanced their structural integrity, and restored normal barrier permeability in this biomimetic microsystem.

Fig. 2.

On-chip formation and mechanical stretching of an alveolar-capillary interface. (A) Long-term microfluidic co-culture produces a tissue-tissue interface consisting of a single layer of the alveolar epithelium (Epithelium; stained with CellTracker Green) closely apposed to a monolayer of the microvascular endothelium (Endothelium; stained with CellTracker Red), both of which express intercellular junctional structures stained with antibodies to Occludin or VE-cadherin, separated by a flexible ECM-coated PDMS membrane (bar, 50 μm). (B) Surfactant production by the alveolar epithelium during air-liquid interface culture in our device detected by cellular uptake of the fluorescent dye, quinacrine that labels lamellar bodies (white dots; bar, 25 μm). (C) Air-liquid interface (ALI) culture leads to a greater increase in trans-bilayer electrical resistance (TER) and produces tighter alveolar-capillary barriers with higher TER (over 800 Ω·cm2), as compared to the tissue layers formed under submerged liquid culture conditions. (D) Alveolar barrier permeability measured by quantitating the rate of fluorescent albumin transport is significantly reduced in air-liquid interface (ALI) cultures compared to liquid cultures (*p < 0.001). Data in (C) and (D) represent the mean ± SEM from three separate experiments. (E) Membrane stretching-induced mechanical strain visualized by the displacements of individual fluorescent quantum dots that were immobilized on the membrane in hexagonal and rectangular patterns before (red) and after (green) stretching (bar, 100 μm). (F) Membrane stretching exerts tension on the cells and causes them to distort in the direction of the applied force, as illustrated by the overlaid outlines of a single cell before (blue) and after (red) application of 15% strain. The pentagons in the micrographs represent microfabricated pores in the membrane. Endothelial cells were used for visualization of cell stretching.

The microfluidic device was then integrated with computer-controlled vacuum to produce cyclic stretching of the tissue-tissue interface to mimic physiological breathing movements (Movie S1). The level of applied strain ranged from 5% to 15% to match normal levels of strain observed in alveoli within whole lung in vivo, as previously described (25). Vacuum application generated uniform, unidirectional mechanical strain across the channel length, as demonstrated by measured displacements of fluorescent quantum dots immobilized on the PDMS membrane (Fig. 2E and Movie S2). Membrane stretching also resulted in cell shape distortion, as visualized by concomitant increases in the projected area and length of the adherent cells in the direction of applied tension (Fig. 2F and Movie S3).

The permeability of the alveolar-capillary barrier to fluorescent albumin remained unchanged during cyclic stretching over 4 hours with physiological levels of strain (5~15%), or after pre-conditioning with 10% strain for varying amounts of time (fig. S1). Application of physiological cyclic strain (10% at 0.2 Hz) also induced cell alignment in the endothelial cells in the lower compartment (fig. S2 and Movie S4), and hence, mimics physiological responses previously observed in cultured endothelium and in living blood vessels in vivo (26, 27). Cyclic stretching caused some pulsatility in the fluid flow, but this unsteady effect was negligible due to the small channel size and low stretching frequency (see Supporting Text). Thus, this microdevice extends far beyond previously described cell stretching systems by permitting the application of cyclic stretch and fluid shear stress to two opposing cell layers separated by a permeable and flexible ECM, while simultaneously enabling analysis of tissue barrier permeability and transport.

Recapitulation of Whole Organ Responses

We then explored whether this microsystem could recapitulate more complex integrated organ-level responses observed in whole living lung, such as pulmonary inflammation, by incorporating blood-borne immune cells in the fluid flowing through the vascular channel. Pulmonary inflammatory responses involve a highly coordinated multistep cascade, including epithelial production and release of early response cytokines, activation of vascular endothelium through upregulation of leukocyte adhesion molecules (e.g., ICAM-1), and subsequent leukocyte infiltration into the alveolar space from the pulmonary microcirculation (28–30). As cytokines are produced by cells of the lung parenchyma, we simulated this process by introducing medium containing the potent pro-inflammatory mediator, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), into the alveolar microchannel in the presence of physiological mechanical strain and examined activation of the underlying microvascular endothelium by measuring ICAM-1 expression.

TNF-α stimulation of the epithelium dramatically increased endothelial expression of ICAM-1 within 5 hours after addition (Fig. 3A and fig. S3), whereas physiological cyclic strain had no effect on ICAM-1 expression. The activated endothelium also promoted firm adhesion of fluorescently-labeled human neutrophils flowing in the vascular microchannel, which do not adhere to the endothelium without TNF-α stimulation (Fig. 3B and Movies S5, S6). Real-time, high resolution, fluorescent microscopic visualization revealed that soon after adhering, the neutrophils flattened (fig. S3) and migrated over the apical surface of the endothelium until they found cell-cell junctions where they underwent diapedesis and transmigrated across the capillary-alveolar barrier through the membrane pores over the period of several minutes (Fig. 3C and Movie S7). Phase contrast microscopic visualization on the opposite side of the membrane revealed neutrophils crawling up through the spaces between neighboring cells and emerging on the surface of the overlying alveolar epithelium (Fig. 3D) where they remained adherent in spite of active fluid flow and cyclic stretching. Similar adhesion and transmigration of neutrophils were observed in response to alveolar stimulation with other pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-8. These sequential events successfully replicate the entire process of neutrophil recruitment from the microvasculature to the alveolar compartment, which is a hallmark of lung inflammation.

Fig. 3.

Reconstitution and direct visualization of complex organ-level responses involved in pulmonary inflammation and infection in the lung-on-a-chip device. (A) Epithelial stimulation with TNF-α (50 ng/ml) upregulates ICAM-1 expression (red) on the endothelium; control shows lack of ICAM-1 expression in the absence of TNF-α treatment. Cells were stretched with 10% strain at 0.2 Hz in both cases. (B) Fluorescently-labeled human neutrophils (white dots) avidly to the activated endothelium within one minute after introduction into the vascular channel. (C) Time-lapse microscopic images showing a captured neutrophil (white arrow) that spreads via firm adhesion and then crawls over the apical surface of the activated endothelium (not visible in this view; direction indicated by yellow arrows) until it forces itself through the cell-cell boundary within about 2 minutes after adhesion (times indicated in seconds). During the following 3 to 4 minutes, the neutrophil transmigrates through the alveolar-capillary barrier by passing through a pentagonal pore in the PDMS membrane, and then it moves away from the focal plane, causing it to appear blurry in the micrographs. (D) Phase contrast microscopic images show a neutrophil (arrow) emerging from the apical surface of the alveolar epithelium at the end of its transmigration over a period of approximately 3 minutes; thus, complete passage takes approximately 6 minutes in total. (E) Time-lapse fluorescence microscopic images showing phagocytosis of two GFP-expressing E. coli (green) bacteria on the epithelial surface by a neutrophil (red) that transmigrated from the vascular microchannel to the alveolar compartment. (bar, 50 μm in (A), (B) and 20 μm in (C)-(E)).

We also demonstrated that this system could mimic the innate cellular response to pulmonary infection of bacterial origin. Living Escherichia coli bacteria constitutively expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) were added to the alveolar microchannel. The presence of these pathogens on the apical surface of the alveolar epithelium for 5 hours was sufficient to activate the underlying endothelium, as indicated by capture of circulating neutrophils and their transmigration into the alveolar microchannel. Upon reaching the alveolar surface, the neutrophils displayed directional movement towards the bacteria, which they then engulfed over a period of a few minutes (Fig. 3E and Movies S8, S9), and the phagocytic activity of the neutrophils continued until most bacteria were cleared from the observation area. We specifically excluded the air-liquid interface in the experiments shown in Figure 3 because inflammatory cytokines are produced by the epithelial tissue, and alveoli often become filled with fluid exudate during early stages of lung infections. These results show that this bioinspired microdevice can effectively recapitulate the normal integrated cellular immune response to microbial infection in human lung alveoli. It also can be used to visualize these cellular responses in real-time via high-resolution microscopic imaging during mechanical stimulation, which has been difficult in most existing cell stretching systems.

Identification of Novel Mechanosensitive Responses to Nanoparticulates

We also explored the potential value of this lung-on-a-chip system for toxicology applications by investigating the pulmonary response to nanoparticulates delivered to the epithelial compartment. Despite the widespread use of nanomaterials, much remains to be learned about their risks to health and the environment (31–33). Existing toxicology methods rely on oversimplified in vitro models or lengthy and expensive animal testing.

When nanoparticles are delivered to the alveoli of the lung in an aerosol, they are deposited in a thin fluid layer supported by surfactant on the surface of the epithelium. To mimic delivery of airborne nanoparticles into the lung using our microdevice, we injected nanoparticle solution into the alveolar microchannel and then gently aspirated the solution to leave a thin liquid layer containing nanoparticles covering the epithelial surface. When alveolar epithelial cells were exposed for 5 hours to 12 nm silica nanoparticles that are commonly used to model the toxic effects of ultrafine airborne particles (34–36), the underlying endothelium in the microvascular channel became activated and exhibited high levels of ICAM-1 expression (Fig. 4A). Although physiological breathing movements (10% cyclic strain) had no effect on ICAM-1 expression on their own, mechanical stretching significantly augmented endothelial expression of ICAM-1 induced by the silica nanoparticles (Fig. 4A). Moreover, this effect was sufficient to induce endothelial capture of circulating neutrophils (Fig. 4A) and to promote their transmigration across the tissue-tissue interface and their accumulation on the epithelial surface (fig. S4).

Fig. 4.

Microengineered model of pulmonary nanotoxicology. (A) Ultrafine silica nanoparticles introduced through an air-liquid interface overlying the alveolar epithelium induce ICAM-1 expression (red) in the underlying endothelium and adhesion of circulating neutrophils (white dots) in the lower channel (bar, 50 μm). Graph shows that physiological mechanical strain and silica nanoparticles synergistically upregulate ICAM-1 expression (*p < 0.005; **p < 0.001). (B) Alveolar epithelial cells increase ROS production when exposed to silica nanoparticles (100 μg/ml) in conjunction with 10% cyclic strain (square) (p < 0.0005), whereas nanoparticles (triangle) or strain (diamond) alone had no effect on intracellular ROS levels relative to control cells (circle); ROS generation was normalized to the mean ROS value at time 0. (C) The alveolar epithelium responds to silica nanoparticles in a strain-dependent manner (*p < 0.001). (D) Addition of 50 nm superparamagnetic nanoparticles produced only a transient elevation of ROS in the epithelial cells subjected to 10% cyclic strain (p < 0.0005). (E) Application of physiological mechanical strain (10%) promotes increased cellular uptake of 100 nm polystyrene nanoparticles (magenta) relative to static cells, as illustrated by representative sections (a-d) through fluorescent confocal images. Internalized nanoparticles are indicated with arrows; green and blue show cytoplasmic and nuclear staining, respectively. (F) Transport of nanomaterials across the alveolar-capillary interface of the lung is simulated by nanoparticle transport from the alveolar chamber to the vascular channel of the lung mimic device. (G) Application of 10% mechanical strain (closed square) significantly increased the rate of nanoparticle translocation across the alveolar-capillary interface compared to static controls in this device (closed triangle) or in a Transwell culture system (open triangle) (p < 0.0005). (H) Fluorescence micrographs of a histological section of the whole lung showing 20 nm fluorescent nanoparticles (white dots, indicated with arrows in the inset at upper right that shows the region enclosed by the dashed square at higher magnification) present in the lung after intratracheal injection of nebulized nanoparticles and ex vivo ventilation in the mouse lung model. Nanoparticles cross the alveolar-capillary interface and are found on the surface of the alveolar epithelium, in the interstitial space, and on the capillary endothelium (PC, pulmonary capillary; AS, alveolar space; blue, epithelial nucleus; bar, 20 μm). (I) Physiological cyclic breathing generated by mechanical ventilation in whole mouse lung produces more than a 5-fold increase in nanoparticle absorption into the blood perfusate when compared to lungs without lung ventilation (p < 0.0005). The graph indicates the number of nanoparticles detected in the pulmonary blood perfusate over time, as measured by drying the blood (1 μl) on glass and quantitating the number of particles per unit area (0.5 mm2). (J) The rate of nanoparticle translocation was significantly reduced by adding NAC to scavenge free radicals (*p < 0.001).

Nanoparticles have been previously shown to induce lung inflammation by stimulating pulmonary epithelial cells to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines and by causing endothelial cells to express ICAM-1 and recruit circulating leukocytes (31–33, 37). However, our results extend this observation by providing evidence to suggest that breathing motions might greatly accentuate the pro-inflammatory activities of silica nanoparticles and contribute significantly to development of acute lung inflammation. This finding also could be relevant for design of artificial lung motions in positive pressure lung ventilator devices, which can sometimes induce dangerous inflammatory responses in the clinic. This effect of mechanical stress would never have been detected in conventional culture models based on static cultures, including Transwell culture systems, that fail to incorporate mechanical force regimens.

Next, various nanomaterials were added to the alveolar microchannel, and the cellular oxidative stress response was quantitated by measuring intracellular production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) using microfluorimetry (31). When the ultrafine (12 nm) silica nanoparticles were added to the alveolar epithelium in the absence of mechanical distortion, there was little or no ROS production. However, when the cells were subjected to physiological levels of cyclic strain (10% at 0.2 Hz), the same nanoparticles induced a steady increase in ROS production that increased by more than 4-fold within 2 hours (Fig. 4B), and this response could be inhibited with the free radical scavenger, N-acetylcysteine (NAC) (fig. S5). ROS levels in the underlying endothelium also increased by almost 3-fold over 2 hrs, but initiation of this response was delayed by about 1 hr compared to the epithelium (fig. S5). Experiments with carboxylated Cd/Se quantum dots (16 nm) produced similar results (fig. S6), whereas cyclic strain alone had no effect on ROS even when applied for 24 hours (fig. S7). Nanomaterial-induced ROS production also increased in direct proportion to the level of applied strain (Fig. 4C). In contrast, exposure of alveolar epithelial cells to 50 nm superparamagnetic iron nanoparticles under the same conditions only exhibited a small transient increase in ROS production (Fig. 4D).

Indeed, this mechanical strain-induced oxidative response appeared to be specific for the silica nanoparticles and carboxylated quantum dots as it was not induced by treatment with various other nanomaterials, including single-walled carbon nanotubes, gold nanoparticles, polystyrene nanoparticles, or polyethylene glycol-coated quantum dots (fig. S8 and Table S1). On the other hand, we found that longer exposure to silica nanoparticles alone for 24 hours induced similar high levels of ROS production even in the absence of mechanical strain (fig. S7), confirming findings of past pulmonary nanotoxicology studies that analyzed the effects of ultrafine silica nanoparticles in static cell cultures (34). Taken together, these data suggest that physiological mechanical stresses due to breathing might act in synergy with nanoparticles to exert early toxic effects or accelerate nanoparticle toxicity in the lung.

Mechanical strain enhanced cellular uptake of nanoparticulates in the alveolar epithelium and underlying endothelium. For example, confocal microscopic analysis revealed that the number of fluorescent nanoparticles (100 nm in diameter) or their aggregates present within the intracellular compartment of alveolar epithelial cells was much greater for the first hour after exposure when cells were subjected to physiological breathing movements (Fig. 4E). Over 70% of cells within mechanically active epithelium and endothelium internalized nanoparticles, whereas this fraction was 10-fold lower in the absence of strain (fig. S9).

Modeling Nanoparticle Transport from Alveoli into the Lung Vasculature

Increasing in vivo evidence suggests that nanomaterials introduced into the alveolar space have the capacity to cross the alveolar-capillary barrier and enter the pulmonary circulation, potentially impacting other organs and causing systemic toxicity (31, 33). When we introduced fluorescent nanoparticles (20 nm in diameter) into the alveolar microchannel and monitored nanoparticle translocation across the alveolar-capillary barrier in air-liquid interface culture by measuring the fraction of particles retrieved from the underlying microvascular channel by continuous fluid flow (Fig. 4F), we observed only a low level of nanoparticle absorption under static conditions. The level was similar to that measured via a static Transwell culture system containing a rigid, porous, ECM-coated membrane lined with opposing layers of alveolar epithelium and capillary endothelium (Fig. 4G). In contrast, there was more than a 4-fold increase in nanoparticle transport into the vascular compartment when our microdevice experienced physiological breathing motions (10% strain at 0.2 Hz) (Fig. 4G). This was striking given that transport of fluorescent albumin remained unchanged under similar loading conditions (fig. S1). Thus, strain-induced increases in nanoparticle absorption across the alveolar-capillary barrier are not due to physical disruption of cell-cell junctions and simple convective transport. Instead, they more likely result from altered transcellular translocation or from a change in paracellular transport that somehow selectively permits passage of these nanoparticulates while restricting movement of small molecules, such as albumin. The presence of an air-liquid interface on the epithelial surface did not appear to produce significantly higher mechanical stresses or change nanoparticle absorption across the alveolar-capillary barrier in our microdevice. An air-liquid interface has been previously shown to exert higher stress on cells (12,38); however, those studies focused mainly on the deleterious effects of a moving air-liquid interface (e.g., as might occur with a mucus plug), which generates much larger forces that are more relevant to small airway closure and reopening.

To determine the physiological relevance of these observations, we conducted similar studies in a whole mouse lung ventilation-perfusion model, which enables intratracheal injection of nebulized nanoparticles and monitoring of nanoparticle uptake into the pulmonary vasculature ex vivo (fig. S10). When 20 nm nanoparticles were injected into whole breathing mouse lung, they were delivered into the deep lung, and histological analysis revealed that they reached the surface of the alveolar epithelium, as well as the underlying interstitial space and microvasculature (Fig. 4H). These findings confirm that these nanoparticles are transported across the alveolar-capillary barrier in vivo as we observed in vitro. When we monitored the number of absorbed nanoparticles collected from the pulmonary venous circulation after nanoparticle injection into the whole perfused lung, we found that nanoparticle transport from the alveoli into the microvasculature was significantly increased in the presence of cyclic breathing in vivo (Fig. 4I), just as we observed in the lung mimic device in vitro (Fig. 4G). Similar studies carried out with Transwell systems that represent the state-of-the-art for in vitro analysis of tissue barrier permeability only exhibited low levels of nanoparticle translocation (Fig. 4G).

This mechanical force-induced increase in nanoparticle translocation was reduced significantly when the cells were incubated with the antioxidant, NAC (Fig. 4J). This finding implies that elevated intracellular production of ROS due to a combination of mechanical strain and nanoparticle exposure might be responsible for the observed increase in barrier permeability to these nanoparticles. We also found that pre-conditioning of endothelial cells with physiological levels of shear stress (15 dyne/cm2) slightly increased the rate of nanoparticle translocation in the presence of mechanical stretch (fig. S11), presumably due to a shear-induced increase in endothelial permeability, as previously demonstrated by others (39). Taken together, these results highlight the advantages of our microengineered device over existing in vitro model systems and provide evidence that the inherent mechanical activity of the living lung may contribute significantly to the transport of air-borne nanoparticulates from the alveolar space into the bloodstream.

Biomimetic Microsystems as Replacements for Animal Testing

Development of cell-based biochips that reproduce complex, integrated organ-level physiological and pathological responses could revolutionize many fields, including toxicology and development of pharmaceuticals and cosmetics that rely on animal testing and clinical trials. This human breathing lung-on-a-chip microdevice provides a proof-of-principle for this novel biomimetic strategy that is inspired by the integrated chemical, biological, and mechanical structures and functions of the living lung. This versatile system enables direct visualization and quantitative analysis of diverse biological processes of the intact lung organ in ways that have not been possible in traditional cell culture or animal models.

There are still differences between our lung mimic device and the alveolar-capillary barrier in vivo (e.g., barrier thickness, cellular composition, lack of alveolar macrophages, changes in air pressure and flow), and the transformed lung cells used in our study might not fully reproduce the responses of native alveolar epithelial cells. However, our data clearly demonstrate that this biomimetic microsystem can reconstitute multiple physiological functions observed in the whole breathing lung. Specifically, the lung mimic device reconstitutes the microarchitecture of the alveolar-capillary unit, maintains alveolar epithelial cells at an air-liquid interface, exerts physiologically relevant mechanical forces to the entire structure, and enables analysis of the influence of these forces on various physiological and pathological lung functions, including interactions with immune cells and pathogens, epithelial and endothelial barrier functions, as well as toxicity and absorption of nanoparticulates across this critical tissue-tissue interface. Existing in vitro mechanical stimulation models fail to offer any of these integrated capabilities, and the fact that our system allows one to study all of these complex physiological phenomena in a single device makes it even more novel. Moreover, this microdevice represents an innovative and low cost screening platform that could potentially replace in vivo assays, or significantly improve the outcome of animal and clinical studies, by enhancing the predictive power of in vitro or in silico computational models.

Microengineering approaches developed in this research also might offer new opportunities to more accurately model critical tissue-tissue interfaces and specialized physical microenvironments found in other organs, such as the gut, kidney, skin, and bone marrow, as well as in human cancers. These biomimetic microsystems are miniaturized (Fig. 1E), and can be easily multiplexed and automated. Hence, with simplified designs and careful choice of biocompatible device materials, they might be useful for high-throughput analysis and screening of cellular responses to drugs, chemicals, particulates, toxins, pathogens, or other environment stimuli relevant to pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and environmental applications. Furthermore, these microengineering approaches might open the possibility of integrating multiple miniaturized organ model systems into a single device to recapitulate interactions between different organs and enable more realistic in vitro assays of the whole body’s response to drugs and toxins (19, 40, 41).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. K. Thodeti for his help with ROS assays, G. M. Whitesides and P. Cherukuri for providing carbon nanotubes and helpful comments, N. Korin for helpful discussions, R. Ruch for providing alveolar epithelial cells, R. Mannix for his imaging assistance, and M. Butte for help with neutrophil isolation. This work was supported by grants from NIH (R01-ES016665), AHA (0835618D), and the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University; D.H. is a recipient of a Wyss Technology Development Fellowship, and D.E.I. is a recipient of a DoD Breast Cancer Innovator Award.

References and Notes

- 1.Davila JC, Rodriguez RJ, Melchert RB, Acosta D., Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol 38, 63 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pampaloni F, Reynaud EG, Stelzer EHK, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 8, 839 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ingber DE, FASEB J 20, 811 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitesides GM, Ostuni E, Takayama S, Jiang XY, Ingber DE, Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng 3, 335 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khademhosseini A, Langer R, Borenstein J, Vacanti JP, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 103, 2480 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Ali J, Sorger PK, Jensen KF, Nature 442, 403 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyvantsson I, Beebe DJ, Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem 1, 423 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shin M et al. , Biomed. Microdevices 6, 269 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song JW et al. , Anal. Chem 77, 3993 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lam MT, Huang YC, Birla RK, Takayama S., Biomaterials 30, 1150 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jang K, Sato K, Igawa K, Chung UI, Kitamori T., Anal. Bioanal. Chem 390, 825 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huh D et al. , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 104, 18886 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carraro A et al. , Biomed. Microdevices 10, 795 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee PJ, Hung PJ, Lee LP, Biotechnol. Bioeng 97, 1340 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powers MJ et al. , Biotechnol. Bioeng 78, 257 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khetani SR, Bhatia SN, Nat. Biotechnol 26, 120 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park JW, Vahidi B, Taylor AM, Rhee SW, Jeon NL, Nat. Protoc 1, 2128 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris SG, Shuler ML, Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng 8, 246 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahler GJ, Esch MB, Glahn RP, Shuler ML, Biotechnol. Bioeng 104, 193 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baudoin R, Griscom L, Monge M, Legallais C, Leclerc E., Biotechnol. Prog 23, 1245 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jang KJ, Suh KY, Lab Chip 10, 36 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takayama S et al. , Adv. Mater 13, 570 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frerking I, Gunther A, Seeger W, Pison U., Intens. Care Med 27, 1699 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim KJ, Malik AB, Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol 284, 247 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Birukov KG et al. , Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol 285, L785 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iba T, Sumpio BE, Microvasc. Res 42, 245 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thodeti CK et al. , Circ. Res 104, 1123 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wagner JG, Roth RA, Pharmacol. Rev 52, 349 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hermanns MI et al. , Cell Tissue Res 336, 91 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wong D, Dorovinizis K., J. Neuroimmunol 39, 11 (1992) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nel A, Xia T, Madler L, Li N., Science 311, 622 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colvin VL, Nat. Biotechnol 21, 1166 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oberdorster G, Oberdorster E, Oberdorster J. Environ. Health Perspect 113, 823 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin WS, Huang YW, Zhou XD, Ma YF, Toxicol. Appl. Pharm 217, 252 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Napierska D et al. , Small 5, 846 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Merget R et al. , Arch. Toxicol 75, 625 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mills NL et al. , Nat. Clin. Pract. Cardiovasc. Med 6, 36 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bilek AM, Dee KC, Gaver DP, J. Appl. Physiol 94, 770 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sill HW et al. , Am. J. Physiol 268, H535 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sin A, Chin KC, Jamil MF, Kostov Y, Shuler ML, Biotechnol. Prog 20, 338 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang C, Zhao ZQ, Rahim NAA, van Noort D, Yu H., Lab Chip 9, 3185 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.