Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To develop and validate a nomogram assessing cancer and all-cause mortality following radical cystectomy. Given concerns regarding the morbidity associated with surgery, there is a need for incorporation of cancer-specific and competing risks into patient counseling and recommendations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 5325 and 1257 diagnosed with clinical stage T2-T4a muscle-invasive bladder cancer from January 1, 2006 to December 31, 2011 from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Medicare and Texas Cancer Registry-Medicare linked data, respectively. Cox proportional hazards models were used and a nomogram was developed to predict 3- and 5-year overall and cancer-specific survival with external validation.

RESULTS

Patients who underwent radical cystectomy were mostly younger, male, married, non-Hispanic white and had fewer comorbidities than those who did not undergo radical cystectomy (P < .001). Married patients, in comparison with their unmarried counterparts, had both improved overall (hazard ratio 0.76; 95% confidence interval 0.70–0.83, P < .001) and cancer-specific (hazard ratio 0.76; 95% confidence interval 0.68–0.85, P < .001) survival. A nomogram developed using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Medicare data, predicted 3- and 5-year overall and cancer-specific survival rates with concordance indices of 0.65 and 0.66 in the validated Texas Cancer Registry-Medicare cohort, respectively.

CONCLUSION

Older, unmarried patients with increased comorbidities are less likely to undergo radical cystectomy. We developed and validated a generalizable instrument that has been converted into an online tool (Radical Cystectomy Survival Calculator), to provide a benefit-risk assessment for patients considering radical cystectomy.

There were an estimated 79,030 new cases and 16,870 deaths from bladder cancer in the United States in 2016.1 Radical cystectomy with extended pelvic lymphadenectomy is recommended for patients with recurrent non–muscle-invasive and muscle-invasive bladder cancer.2 Despite these longstanding guidelines, radical cystectomy is markedly underused as historically only 21% of patients with muscle-invasive disease are offered this potentially curative surgery.3 We recently published an updated analysis confirming a slight decrease in radical cystectomy utilization rates at 19% with significant predictors for underuse, namely advanced age and increased comorbidities.4

The European Association of Urology and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network have updated guidelines supporting the use of radical cystectomy in recurrent non–muscle-invasive and muscle-invasive bladder cancer with multimodal reserved for select patients.2,5,6 Radical cystectomy continues to be associated with a non-negligible risk of morbidity and all-cause mortality.7,8 These concerns, as well as prior reports concerning underuse due to advanced age and increased comorbidities, suggest that cancer-specific as well as all-cause mortality rates should be incorporated into patient counseling and guideline recommendations.4,7 Prior literature has suggested that risk assessment and prediction tools may enhance clinical decision-making and counseling of patients with bladder cancer.9 However, many of the available decision tools either do not incorporate all-cause mortality or lack external validation.9 The purpose of the present study was to assess cancer-specific and overall survival outcomes in patients diagnosed with bladder cancer according to use of radical cystectomy. Moreover, we wanted to identify predictors for survival to develop and validate a population-based nomogram that may be used for preoperative counseling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data Source

We used Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare linked data from the National Cancer Institute. The most recent release of the SEER dataset contained information on patients with newly diagnosed cancers in 18 US regions that are generalizable to the US population. The cancer identified in the SEER database conformed to the standards of the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries, and case ascertainment in the SEER data was 98% complete.10 The SEER database contains information on patient demographics, tumor characteristics (stage, grade, histology), and follow-ups. The Medicare database contains information on inpatient and outpatient claims.

To validate the predictive accuracy of the nomogram, we used study subjects selected from the Texas Cancer Registry (TCR), a statewide population-based registry that meets the high-quality data standards of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Central Cancer Registries. Under the supervision of the National Cancer Institute, registry records from the TCR have been linked to Medicare claims with case ascertainment rate of 97% and linkage rate of 98%. The study was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board at The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston and MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Ascertainment of Study Cohorts

For both the discovery and validation cohorts (ie, SEER- and TCR-Medicare cohorts, respectively), we restricted our analysis to patients with clinical stage II-IVa bladder cancer diagnosed as transitional cell or urothelial carcinoma from January 1, 2006 through December 31, 2011 with claims data available through December 31, 2013. For model validation, the predicted probability of overall and cancer-specific survival in the validation set (TCR-Medicare cohort) calculated by the nomogram created from the SEER-Medicare cohort was compared with the actual survival outcome of patients in the validation set to generate a c-index to quantify the discrimination of the nomogram. We excluded subjects who were diagnosed with locally advanced cancers defined according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network definition as clinical stage T4b or node-positive and metastatic disease to restrict our sample to patients with unambiguous treatment options.2 We restricted the study sample to subjects who had Medicare Fee-for-Service coverage and for whom Medicare Part A and Part B claims data were available. The final cohort consisted of 5325 and 1257 patients from SEER and TCR, respectively (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2).

Identification of Bladder Cancer Treatments

Radical cystectomy was identified based on procedure codes that are indicative of radical cystectomy. Radical cystectomy captured in this study included both open and robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery. Patients who received radiation were classified on the basis of diagnosis and procedure codes in Medicare claims that are consistent with radiotherapeutic procedures (Supplementary Table S3). We identified subjects who received chemotherapy based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision and Current Procedural Terminology, Fourth Edition codes that are consistent with chemotherapeutic agents commonly used to manage bladder cancer in the absence of a concomitant code for radical cystectomy (Supplementary Table S3). Subjects who underwent surgery alone or in combination with radiation or chemotherapy were categorized as the radical cystectomy group. Among patients who underwent radical cystectomy, use of pelvic lymph node dissection was defined as “yes” or “no.” Among those without radical cystectomy, we combined subjects who received chemotherapy alone, radiation alone, or combination chemotherapy and radiation into 1 treatment group because bladder-sparing therapeutic protocols for invasive bladder cancer typically combine radiation and chemotherapy. Subjects who did not have SEER-Medicare variable specifications consistent with radical cystectomy, chemotherapy, or radiation were deemed to have received no further aggressive cancer-directed care and thus were categorized as having received no curative treatment.

Study Covariates

From the SEER data, we determined patient age, race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic other races), gender, marital status (single, married, and unknown), and SEER region (Northeast, South, Midwest, and West). County-level median household income was acquired via linkage to the Area Health Resource File and then divided into quartiles. Clinical and tumor characteristics include clinical stage, tumor grade, and presence of hydronephrosis, which have been previously associated with survival outcomes.11,12 Comorbidity was assessed using the Klabunde modification of the Charlson index during the year before cancer diagnosis.12 The Klabunde modification uses comorbid conditions identified by the Charlson comorbidity index and incorporates the diagnostic and procedure data contained in hospital claims and physician or outpatient claims.

Statistical Analysis

We conducted bivariate analyses to assess the association of surgeries (radical cystectomy) with the list of covariates described previously, using the Pearson chi-square test.

Kaplan-Meier curves were used to estimate overall and bladder cancer-specific survival according to utilization of radical cystectomy and whether lymph node dissection was performed. Cox proportional hazards models controlling for patient demographics and clinical covariates were performed to assess the relationship between the use of radical cystectomy and patients’ overall survival, as well as cancer-specific survival. Similar analysis was performed to assess the relationship between radical cystectomy and noncancer-related survival. Prior research has suggested that an effect on noncancer survival is strong evidence for unmeasured confounding by indication, or selection bias. Cox proportional hazards models were used to quantify the association between survival outcomes and these characteristics of which a nomogram was created. A nomogram was developed based on the results of Cox proportional hazards models to predict 3- and 5-year overall and cancer-specific survival, containing the associated risk factors (Radical Cystectomy Survival Calculator), available at https://www.utmb.edu/surgery/urology/). We used TCR-Medicare bladder cancer cohort to validate the predictive accuracy of the nomogram model and concordance index (c-index) was calculated.

All statistical tests were 2-sided, and all analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R version 3.2.4 software (http://www.r-project.org/). Statistical significance was defined as P < .05.

RESULTS

Patient demographics are summarized in Table 1. Overall, 1377 (25.9%) of the 5325 patients underwent radical cystectomy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer. A significantly higher proportion of patients who underwent cystectomy were younger, male, and married, and had no to minimal comorbidities when compared with those who did not undergo surgery (all P < .01). Patients who underwent radical cystectomy more often had clinical stage II cancer, high-grade disease, and no hydronephrosis (all P < .05). Moreover, 229 (16.6%) patients underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy, whereas 1227 (89.1%) patients had pelvic lymph node dissection at the time of radical cystectomy.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the SEER-Medicare cohort

| Radical Cystectomy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Total | No | Col. %* | Yes | Col. %* | P Value† |

| Year of diagnosis | <.001 | |||||

| 2006 | 942 | 689 | 17.5 | 253 | 18.4 | |

| 2007 | 905 | 651 | 16.5 | 254 | 18.4 | |

| 2008 | 908 | 655 | 16.6 | 253 | 18.4 | |

| 2009 | 848 | 622 | 15.8 | 226 | 16.4 | |

| 2010 | 866 | 631 | 16.0 | 235 | 17.1 | |

| 2011 | 856 | 700 | 17.7 | 156 | 11.3 | |

| Age group | <.001 | |||||

| 66–69 | 748 | 454 | 11.5 | 294 | 21.4 | |

| 70–74 | 1029 | 650 | 16.5 | 379 | 27.5 | |

| 75–79 | 1217 | 852 | 21.6 | 365 | 26.5 | |

| 80+ | 2331 | 1992 | 50.5 | 339 | 24.6 | |

| Sex | <.001 | |||||

| Male | 3612 | 2758 | 69.9 | 854 | 62.0 | |

| Female | 1713 | 1190 | 30.1 | 523 | 38.0 | |

| Race | .01 | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 4605 | 3425 | 86.8 | 1180 | 85.7 | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 306 | 240 | 6.1 | 66 | 4.8 | |

| Hispanic | 170 | 114 | 2.9 | 56 | 4.1 | |

| Other | 244 | 169 | 4.3 | 75 | 5.4 | |

| Marital status | <.001 | |||||

| Single | 843 | 628 | 15.9 | 215 | 15.6 | |

| Married | 2875 | 2049 | 51.9 | 826 | 60.0 | |

| Unknown | 1607 | 1271 | 32.2 | 336 | 24.4 | |

| Median household income, $ | <.01 | |||||

| <$45,470 | 1412 | 1086 | 27.5 | 326 | 23.7 | |

| $45,470–$54,375 | 1305 | 986 | 25.0 | 319 | 23.2 | |

| $54,376–$63,511 | 1304 | 943 | 23.9 | 361 | 26.2 | |

| ≥$63,511 | 1304 | 933 | 23.6 | 371 | 26.9 | |

| Stage | <.001 | |||||

| II | 3036 | 2461 | 62.3 | 575 | 41.8 | |

| III | 881 | 468 | 11.9 | 413 | 30.0 | |

| IV | 1408 | 1019 | 25.8 | 389 | 28.2 | |

| Hydronephrosis | .02 | |||||

| No | 4704 | 3464 | 87.7 | 1240 | 90.1 | |

| Yes | 621 | 484 | 12.3 | 137 | 9.9 | |

| Grade | <.001 | |||||

| Low | 253 | 207 | 5.2 | 46 | 3.3 | |

| High | 4738 | 3440 | 87.1 | 1298 | 94.3 | |

| Unknown | 334 | 301 | 7.6 | 33 | 2.4 | |

| Comorbidity score | <.001 | |||||

| 0 | 2736 | 1938 | 49.1 | 798 | 58.0 | |

| 1 | 1359 | 985 | 24.9 | 374 | 27.2 | |

| 2 | 613 | 494 | 12.5 | 119 | 8.6 | |

| 3+ | 617 | 531 | 13.4 | 86 | 6.2 | |

| Lymph node dissection | ||||||

| No | 150 | - | - | 150 | 10.9 | |

| Yes | 1227 | - | - | 1227 | 89.1 | |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | ||||||

| No | 1148 | - | - | 1148 | 83.4 | |

| Yes | 229 | - | - | 229 | 16.6 | |

Percentages reported in each row is column percentage calculated by dividing the number of patients in each row by the total number of patients in that column.

P values derived using chi-square test.

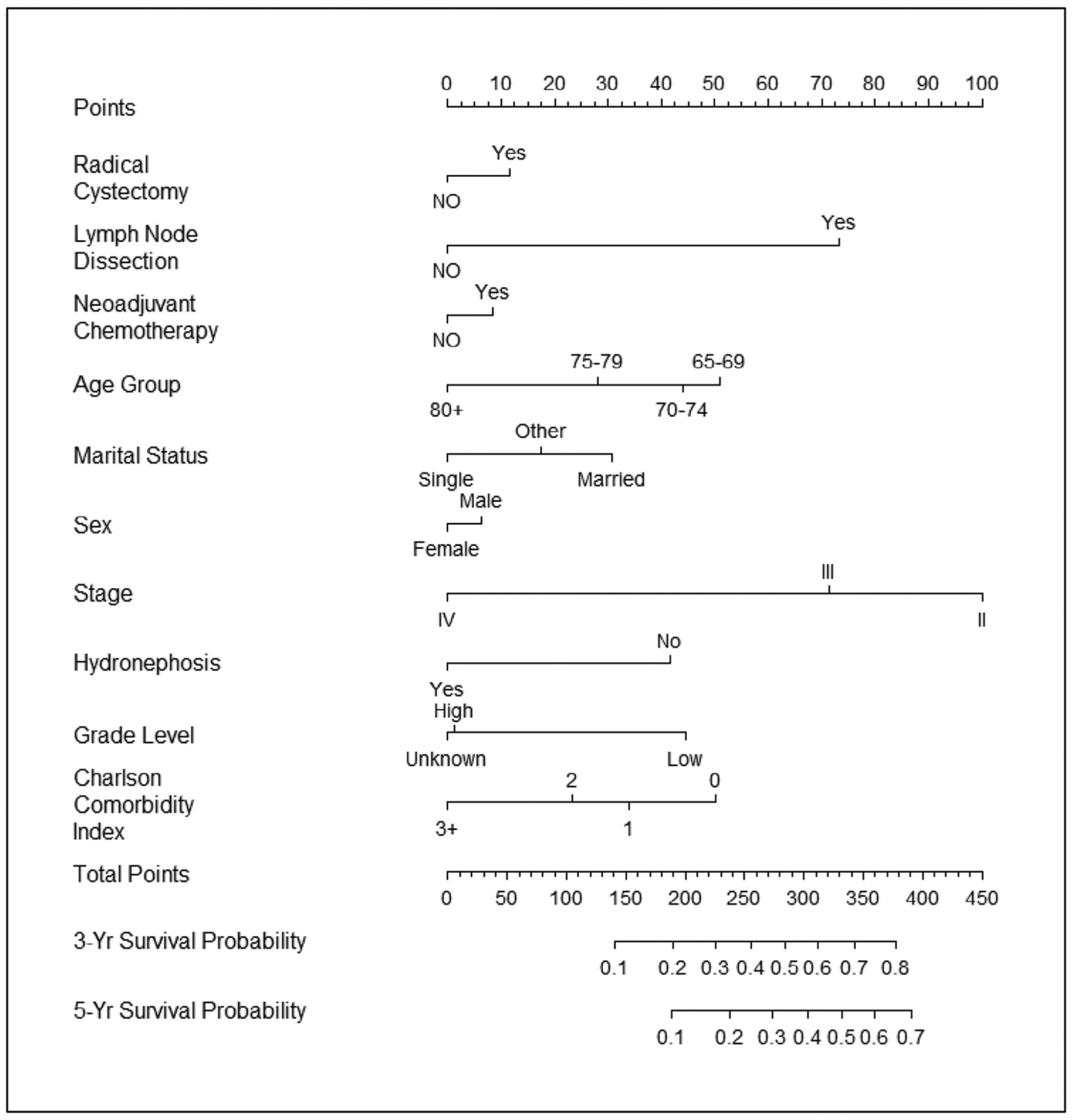

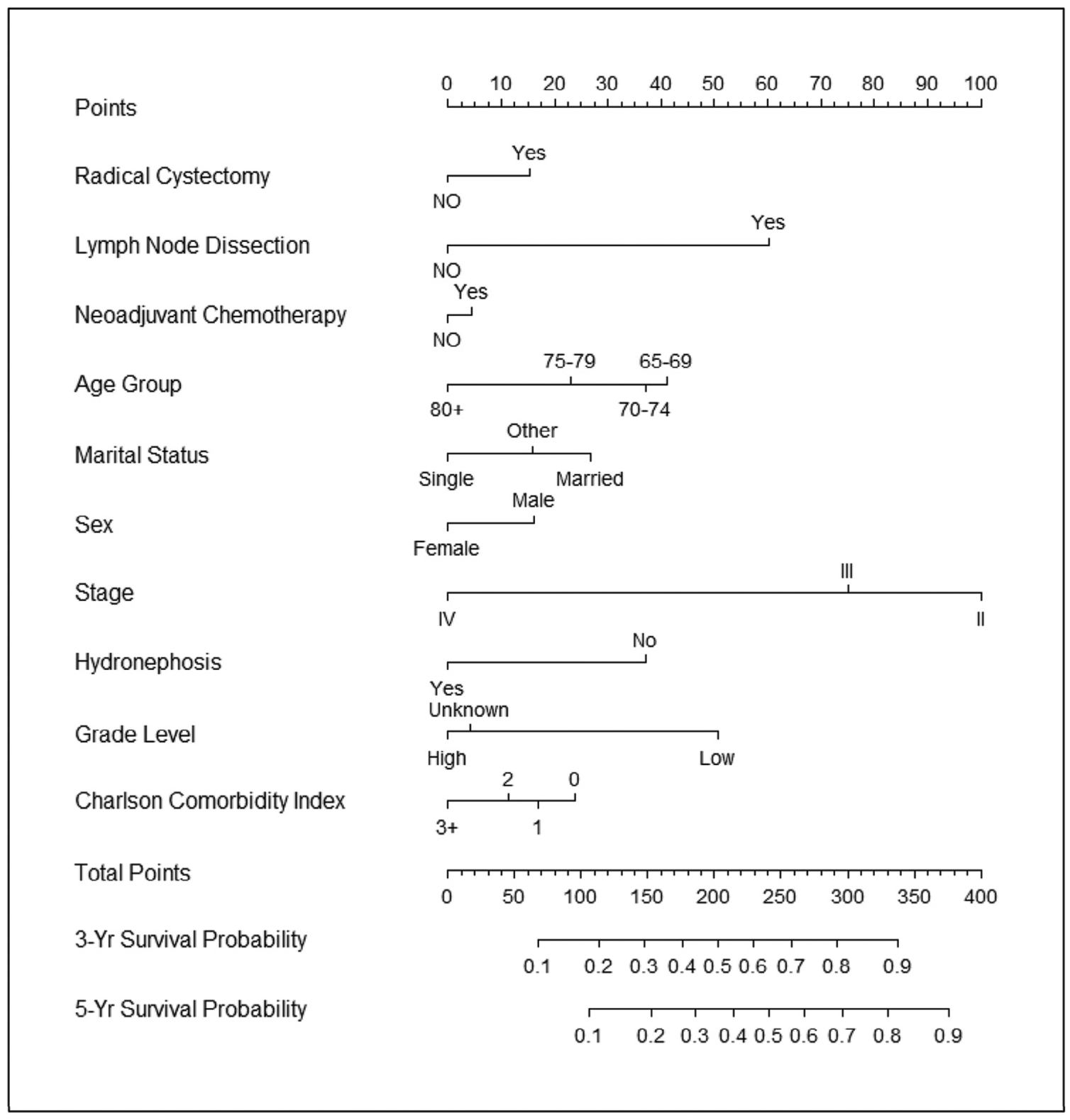

We assessed predictors for overall and cancer-specific survival as shown in Table 2. Married in comparison with unmarried patients had both improved overall (hazard ratio [HR] 0.76; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.70–0.83, P < .001) and cancer-specific (HR 0.76; 95% CI 0.68–0.85, P < .001) survival. Radical cystectomy was associated with improved overall (HR 0.89; 95% CI 0.78–1.01, P = .06) and cancer-specific survival (HR 0.83; 95% CI 0.70–0.97, P = .02), respectively. Older age at diagnosis (>80 vs 66–69 years old, HR 1.63; 95% CI 1.47–1.81, P < .001), higher comorbidity (Charlson comorbidity index 3+ vs 0, HR 1.68; 95% CI 1.53–1.85, P < .001), and non-Hispanic black vs white patients (HR 1.28; 95% CI 1.12–1.45, P < .001) were associated with decreased overall survival. Moreover, adverse tumor characteristics including advanced stage IV vs II (HR 2.82; 95% CI 2.62–3.04, P < .001), high vs low grade (HR 1.55; 95% CI 1.32–1.81, P < .001) and presence of hydronephrosis yes vs no (HR 1.50; 95% CI 1.37–1.64, P < .001) were associated with worse overall survival. Similar findings for cancer-specific survival persisted; specifically advanced age, increased comorbidities, and non-Hispanic black patients were associated with worse survival outcomes (all P < .001). In addition, female patients had worse cancer-specific survival than their male counterparts (HR 1.21; 95% CI 1.11–1.32, P < .001). Median annual income was not associated with cancer-specific survival except for patients with $45,470–$54,375 vs <$45,470 median income (HR 0.90; 95% CI 0.80–1.00, P < .05). Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the overall and cancer-specific survival estimates, respectively, using estimated predictors to generate nomograms. Furthermore, using patient data derived from TCR-Medicare (Supplementary Table S2) we further validated the utility of these nomograms, which had concordance indices of 0.65 and 0.66, respectively. To further determine a valid association between radical cystectomy and improved cancer-specific survival, we assessed noncancer survival by treatment with radical cystectomy (rather than all-cause survival). We did not observe a significant association between radical cystectomy and noncancer survival (HR 1.00; 95% CI 0.81–1.23, P = .999).

Table 2.

Cox regression model assessing factors predicting overall survival and cancer-specific survival

| Overall Survival | Cancer-Specific Survival | Other-Cause Survival | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P Value | HR | 95% CI | P Value | ||||

| Radical cystectomy | ||||||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Yes | 0.89 | 0.78 | 1.01 | .06 | 0.83 | 0.70 | 0.97 | .02 | 1.00 | 0.81 | 1.23 | .999 |

| Lymph node dissection | ||||||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Yes | 0.51 | 0.45 | 0.58 | <.001 | 0.51 | 0.43 | 0.59 | <.001 | 0.52 | 0.43 | 0.64 | <.001 |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | ||||||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Yes | 0.97 | 0.83 | 1.15 | .75 | 0.94 | 0.77 | 1.16 | .58 | 1.02 | 0.79 | 1.32 | .89 |

| Year of diagnosis | ||||||||||||

| 2006 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 2007 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 1.10 | .92 | 0.96 | 0.85 | 1.09 | .55 | 1.06 | 0.90 | 1.26 | .476 |

| 2008 | 0.94 | 0.85 | 1.04 | .21 | 0.86 | 0.76 | 0.98 | .02 | 1.09 | 0.92 | 1.29 | .317 |

| 2009 | 0.90 | 0.81 | 1.00 | .05 | 0.86 | 0.76 | 0.98 | .03 | 0.99 | 0.83 | 1.18 | .891 |

| 2010 | 0.95 | 0.85 | 1.06 | .33 | 0.83 | 0.72 | 0.95 | .01 | 1.23 | 1.03 | 1.47 | .024 |

| 2011 | 0.91 | 0.81 | 1.01 | .09 | 0.66 | 0.57 | 0.76 | <.001 | 1.53 | 1.28 | 1.83 | <.001 |

| Age group | ||||||||||||

| 66–69 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 70–74 | 1.05 | 0.94 | 1.19 | .37 | 1.04 | 0.89 | 1.20 | .64 | 1.08 | 0.90 | 1.31 | .409 |

| 75–79 | 1.24 | 1.11 | 1.38 | <.001 | 1.20 | 1.04 | 1.38 | .01 | 1.30 | 1.08 | 1.56 | .005 |

| 80+ | 1.63 | 1.47 | 1.81 | <.001 | 1.55 | 1.36 | 1.77 | <.001 | 1.76 | 1.48 | 2.08 | <.001 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Female | 1.04 | 0.97 | 1.12 | .25 | 1.22 | 1.12 | 1.34 | <.001 | 0.78 | 0.69 | 0.88 | <.001 |

| Race | ||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 1.28 | 1.12 | 1.45 | <.001 | 1.20 | 1.02 | 1.41 | .03 | 1.44 | 1.17 | 1.78 | <.001 |

| Hispanics | 0.93 | 0.77 | 1.11 | .42 | 0.90 | 0.71 | 1.14 | .40 | 0.98 | 0.74 | 1.31 | .909 |

| Other | 0.94 | 0.81 | 1.10 | .44 | 0.83 | 0.68 | 1.02 | .08 | 1.13 | 0.90 | 1.42 | .298 |

| Marital status | ||||||||||||

| Single | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Married | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.83 | <.001 | 0.76 | 0.68 | 0.85 | <.001 | 0.77 | 0.67 | 0.90 | <.001 |

| Unknown | 0.86 | 0.78 | 0.95 | <.01 | 0.83 | 0.74 | 0.94 | <.01 | 0.92 | 0.78 | 1.08 | .282 |

| Median household income, $ | ||||||||||||

| <$45,470 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| $45,470–$54,375 | 0.94 | 0.86 | 1.02 | .14 | 0.90 | 0.80 | 1.00 | .05 | 1.01 | 0.88 | 1.15 | .934 |

| $54,376–$63,511 | 0.95 | 0.87 | 1.04 | .26 | 0.96 | 0.86 | 1.07 | .43 | 0.95 | 0.83 | 1.10 | .51 |

| ≥$63,511 | 0.93 | 0.86 | 1.02 | .12 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 1.12 | .94 | 0.82 | 0.71 | 0.95 | .008 |

| Stage | ||||||||||||

| II | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| III | 1.33 | 1.21 | 1.45 | <.001 | 1.35 | 1.19 | 1.52 | <.001 | 1.28 | 1.11 | 1.47 | <.001 |

| IV | 2.82 | 2.62 | 3.04 | <.001 | 3.45 | 3.15 | 3.77 | <.001 | 1.82 | 1.59 | 2.07 | <.001 |

| Hydronephrosis | ||||||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Yes | 1.50 | 1.37 | 1.64 | <.001 | 1.50 | 1.34 | 1.68 | <.001 | 1.49 | 1.28 | 1.74 | <.001 |

| Grade | ||||||||||||

| Low | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| High | 1.55 | 1.32 | 1.81 | <.001 | 1.72 | 1.38 | 2.12 | <.001 | 1.36 | 1.09 | 1.72 | .008 |

| Unknown | 1.57 | 1.29 | 1.90 | <.001 | 1.65 | 1.27 | 2.14 | <.001 | 1.51 | 1.12 | 2.02 | .006 |

| Comorbidity score | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 1 | 1.16 | 1.08 | 1.25 | <.001 | 1.08 | 0.98 | 1.19 | .12 | 1.32 | 1.17 | 1.49 | <.001 |

| 2 | 1.34 | 1.22 | 1.48 | <.001 | 1.18 | 1.04 | 1.34 | .01 | 1.65 | 1.41 | 1.93 | <.001 |

| 3+ | 1.68 | 1.53 | 1.85 | <.001 | 1.34 | 1.17 | 1.52 | <.001 | 2.34 | 2.02 | 2.71 | <.001 |

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Figure 1.

Nomogram for predicting overall survival. Validated with Texas Cancer Registry-Medicare cohort: C-index = 0.657.

Figure 2.

Nomogram for predicting cancer-specific survival. Validated with Texas Cancer Registry-Medicare cohort: C-index = 0.663.

COMMENT

Radical cystectomy is an underutilized treatment option, especially among patients with advanced age and increased comorbidities, despite being a guideline-recommended treatment with improved survival outcomes. Given concerns regarding increased morbidity and mortality associated with the procedure, we developed a nomogram with moderate concordance indices in a validation cohort. Using population-based cohorts combined with validation further enhances the generalizability of these data.

Our study has several important findings. First, we observed significant underutilization of radical cystectomy among patients with advanced age and increased comorbidities. These findings corroborate prior reports given concerns of increased morbidity and mortality associated with the procedure, prompting concerns regarding the oncologic benefit of this procedure in those deemed “unsatisfactory” surgical candidates.3,8 Indeed, up to 3% of patients die within 90 days of radical cystectomy of which increased patient comorbidity increases the morbidity and mortality of the procedure.13 Although radical cystectomy is a complex surgery, prior studies have suggested a survival benefit in the elderly even among octogenarians and those with increased comorbidities.14 However, as noted in those studies, there remains a significant complication, hospital readmission, and perioperative mortality risk with radical cystectomy, which requires further research to determine which subgroups of elderly patients may benefit from this surgery.14 In addition, preliminary studies have demonstrated varying perioperative risks using robotic cystectomy as a means to possibly reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with radical cystectomy.15 Nonetheless, it appears further research discerning the risks vs benefits among “high-risk” surgical patients undergoing radical cystectomy is needed in the decision-making process.

Second, we noticed racial and ethnic disparity, with non-Hispanic black patients having worse overall and cancer-specific survival than non-Hispanic white patients. We have previously noted racial and ethnic disparities with decreased utilization of radical cystectomy among non-Hispanic black patients after controlling for other demographic characteristics, neighborhood socioeconomic status, and clinical factors.4 Racial and ethnic disparities have been previously implicated for the decreased survival outcomes of many cancers.16 We did not take into account the delay of diagnosis, proximity to providers who perform radical cystectomy and other predictors for quality of bladder cancer care which are important predictors for cancer-specific and overall survival.3 Moreover, although we cannot comment on the extent to which biological aggressiveness of tumors among non-Hispanic black patients this disparity may underlie, it is disconcerting that both overall and cancer-specific survival are decreased among these patients.

Third, married patients had significantly increased use of radical cystectomy with improved overall and cancer-specific survival. Married patients have been previously shown with other cancers to be associated with improved survival outcomes.17 Marital status has been previously associated, regardless of gender, with survival outcomes following radical cystectomy, with worse overall and cancer-specific survival outcomes among single, divorced, or widowed patients.18 Rationale for these findings include improved social network among married patients with additional reinforcement of health and improved quality of life.17 Furthermore, although not assessed in the present study, married patients are less likely to be depressed, which may contribute to adverse survival outcomes.19 Patient support groups and survivorship programs are an essential component to cancer care, and these data support the effectiveness of these programs especially among unmarried patients.18 Further research evaluating the integration of such programs into bladder cancer care is needed.

Lastly, we developed nomograms taking into account predictors for overall and cancer-specific survival. Using these predictors, we estimated 3- and 5-year survival for patients and providers considering radical cystectomy as a treatment option. Moreover, we validated the nomograms using the TCR-Medicare database with moderate concordance indices enhancing the generalizability of our findings. For example, a 75-year-old married man with no comorbidities and high-grade cT2 bladder cancer who undergoes neoadjuvant chemotherapy, radical cystectomy, and bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection would have a 27% and 43% 5-year risk of cancer-specific and all-cause mortality, respectively. Conversely, a 90-year-old single woman with significant comorbidities (ie, CCI 3+) and high-grade cT2 disease who undergoes the same treatment would have a 60% and 81% 5-year risk of cancer-specific and all-cause mortality, respectively. Prior studies have developed similar nomograms to estimate perioperative mortality and morbidity.8,20 However, these nomograms either lacked long-term follow-up beyond 90 days or were limited to fewer than 200 patients and less than 30 deaths.8,20 The present study had a total of 5035 patients with 4074 deaths analyzed to develop the nomogram and validated in 1257 patients with 946 deaths over a 5-year period. In addition to using patient clinical and pathologic predictors, our nomogram included determinants previously not analyzed such as marital status and hydronephrosis. Although such single institution-derived nomograms are useful in the treatment decision-making process, quite often calibration of these nomograms reveals overestimation of their estimates and limits the generalizability of their findings.20 The nomograms in the present study represent an improvement over the current decision-making process for patients with invasive bladder cancer.

Although our findings are policy and clinically relevant, they must be interpreted within the context of the study design. First, patients identified in the present study are older and the results may not be generalizable to younger patients. However, because a majority of patients diagnosed with bladder cancer are in the sixth decade of life or greater, this investigation provides a contemporary assessment of predictors for both overall and cancer-specific survival that is relevant to most bladder cancer patients. Moreover, we further evaluated noncancer survival by treatment with radical cystectomy (rather than all-cause survival). Whereas we noticed significantly improved cancer-specific survival with use of radical cystectomy, surgery was not significantly associated with noncancer survival. An effect on noncancer survival is strong evidence for unmeasured confounding by indication, or selection bias, which we did not observe in the present study. Second, there is level 1 evidence supporting neoadjuvant chemotherapy with significant downstaging and improved survival benefit at radical cystectomy. The use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy was not associated with a significant survival benefit in the present analysis due to low utilization rates observed in the present cohort, and quality of chemotherapy administered in the community may vary. Third, we used population-based data to provide cancer-specific and overall survival estimates. Information on risk factors was obtained from diagnosis codes included in charges for outpatient and hospitalization services. Such diagnoses are not always accurate or complete. Although there are certain criticisms regarding the validity of using population-based databases21 as well as the ability to not control for unknown confounders, we believe the present nomograms and validation present generalizable estimates that may be used as part of the treatment decision-making process.

CONCLUSION

In summary, clinical uncertainty in high-risk procedures such as radical cystectomy in at-risk populations are critically important to consider in the treatment decision-making process. Married patients had significantly improved utilization of surgery and improved overall and cancer-specific survival. The current study provides a graphical aid for discussion of cancer-specific and other-cause mortality at the time of treatment counseling. This graphical aid has been converted into an online instrument (Radical Cystectomy Survival Calculator available at https://www.utmb.edu/surgery/urology/RCSC.asp). Further research will be conducted to determine the clinical impact the calculator has on treatment decision-making.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment.

This study used the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare linked and Texas Cancer Registry (TCR)-Medicare linked databases. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Program, NCI; the Office of Research, Development and Information, CMS; Information Management Services (IMS), Inc.; and the SEER program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER database. The authors thank Alexander Vo, Ryan S. Westberry, and Scott T. Moen for the development of the Radical Cystectomy Survival Calculator available at https://www.utmb.edu/surgery/urology/RCSC.asp.

Funding Support:

This study was conducted with the support of the Institute for Translational Sciences at the University of Texas Medical Branch, supported in part by a Clinical and Translational Science Award Mentored Career Development (KL2) Award (KL2TR001441) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (NIH). This study was funded, in part, by the NIH Bladder SPORE (5P50CA091846-03) (AMK).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

APPENDIX

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2017.08.024.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark PE, Agarwal N, Biagioli MC, et al. Bladder cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:446–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gore JL, Litwin MS, Lai J, et al. Use of radical cystectomy for patients with invasive bladder cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:802–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams SB, Huo J, Chamie K, et al. Underutilization of radical cystectomy among patients diagnosed with clinical stage T2 muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Eur Urol Focus. 2016;doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gakis G, Efstathiou J, Lerner SP, et al. ICUD-EAU International Consultation on Bladder Cancer 2012: radical cystectomy and bladder preservation for muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Eur Urol. 2013;63:45–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitin T, George A, Zietman AL, et al. Long-term outcomes among patients who achieve complete or near-complete responses after the induction phase of bladder-preserving combined-modality therapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a pooled analysis of NRG oncology/ RTOG 9906 and 0233. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;94:67–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boorjian SA, Kim SP, Tollefson MK, et al. Comparative performance of comorbidity indices for estimating perioperative and 5-year all cause mortality following radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. J Urol. 2013;190:55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor JM, Feifer A, Savage CJ, et al. Evaluating the utility of a preoperative nomogram for predicting 90-day mortality following radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. BJU Int. 2012;109:855–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kluth LA, Black PC, Bochner BH, et al. Prognostic and prediction tools in bladder cancer: a comprehensive review of the literature. Eur Urol. 2015;68:238–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weir HK, Johnson CJ, Mariotto AB, et al. Evaluation of North American Association of Central Cancer Registries’ (NAACCR) data for use in population-based cancer survival studies. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2014;2014:198–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Culp SH, Dickstein RJ, Grossman HB, et al. Refining patient selection for neoadjuvant chemotherapy before radical cystectomy. J Urol. 2014;191:40–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, Warren JL. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:1258–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Novara G, De Marco V, Aragona M, et al. Complications and mortality after radical cystectomy for bladder transitional cell cancer. J Urol. 2009;182:914–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Izquierdo L, Peri L, Leon P, et al. The role of cystectomy in elderly patients—a multicentre analysis. BJU Int. 2015;116(suppl 3):73–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Groote R, Gandaglia G, Geurts N, et al. Robot-assisted radical cystectomy for bladder cancer in octogenarians. J Endourol. 2016; 30:792–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barocas DA, Alvarez J, Koyama T, et al. Racial variation in the quality of surgical care for bladder cancer. Cancer. 2014;120:1018–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahal BA, Inverso G, Aizer AA, et al. Incidence and determinants of 1-month mortality after cancer-directed surgery. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sammon JD, Morgan M, Djahangirian O, et al. Marital status: a gender-independent risk factor for poorer survival after radical cystectomy. BJU Int. 2012;110:1301–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prasad SM, Eggener SE, Lipsitz SR, Irwin MR, Ganz PA, Hu JC. Effect of depression on diagnosis, treatment, and mortality of men with clinically localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2471–2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brooks M, Godoy G, Sun M, Shariat SF, Amiel GE, Lerner SP. External validation of bladder cancer predictive nomograms for recurrence, cancer-free survival and overall survival following radical cystectomy. J Urol. 2016;195:283–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun M, Trinh QD. A Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database malfunction: perceptions, pitfalls and verities. BJU Int. 2016;117:551–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.