Abstract

We assessed adherence in an infant TB prevention trial in Kenya with a urine isoniazid metabolite-detecting dipstick. Ninety-seven infants had 155 assays performed; 77 (49.7%) were positive despite caregiver-reported adherence. Positive assays were associated with maternal secondary education, HIV suppression, and no reported missed doses in past 3 days, suggesting caregiver education and self-medication use influenced infant adherence.

Keywords: infant, tuberculosis, prevention, isoniazid, adherence, urine

Introduction

Over 15 million children are exposed to tuberculosis (TB) each year(1). For young children, risk of TB is ~20% within 2 years of exposure(2). Isoniazid (INH) preventative therapy (IPT) reduces pediatric TB risk by 60%(3). However, efficacy depends on adherence, often reported as low in programmatic settings. INH metabolites are detectable in urine, providing a noninvasive objective means of adherence assessment.

We performed a biomarker-based assessment of infant IPT adherence comparing caregiver-reported adherence to urine INH metabolite testing using a urine dipstick in a TB prevention trial of HIV-exposed uninfected Kenyan infants.

Methods

In the parent trial, HIV-exposed uninfected infants 6 weeks of age without known TB exposure were randomized to 12 months daily INH (~10 mg/kg) vs. no INH to evaluate INH efficacy to prevent primary M. tuberculosis infection(4). Follow-up visits were at 10 and 14 weeks, and 6, 9, and 12 months of age with final study visit at 12 months post-randomization at ~14 months of age. Standardized adherence questionnaires were administered to caregivers of infants randomized to INH.

Urine was collected using a pediatric collection bag. Dipsticks designed at the Lutz laboratory (University of Washington Bioengineering) used a modified Arkansas method based on a colorimetric change which occurs when INH metabolite isonicotinic acid reacts with cyanogen chloride and barbituric acid (see text, figure, supplementary table 1 and 2)(5). INH metabolite is typically detectable in urine up to 24–30 hours after ingestion. A positive test was defined as any color change and considered negative if no color change occurred. Cost to make each strip is <1 USD. A subset of tests were compared to the commercially available IsoScreen (~8 USD per test) (GFC Diagnostics Limited, Oxfordshire, UK) with reported 95–99% sensitivity within 24 hours and 85% within 48 hours of INH ingestion, with 98% specificity in evaluations of adults(6, 7).

Statistical Analysis.

We compared caregiver-reported adherence measures to assay results and evaluated correlates of a positive INH dipstick using generalized linear models with a log-binomial link and clustered by participant. Agreement to IsoScreen was assessed and concordance measured using kappa (κ) statistics and sensitivity and specificity with IsoScreen as reference. Time between caregiver-reported INH dose and urine collection was compared using Mann-Whitney U test. Statistical significance was evaluated at alpha 0.05 and regression estimates reported with 95% confidence intervals.

Ethics Approval

Caregivers provided written informed consent. Study procedures were approved by University of Washington Institutional Review Board and Kenyatta National Hospital/University of Nairobi Ethics and Research Committee. The parent trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02613169).

Results

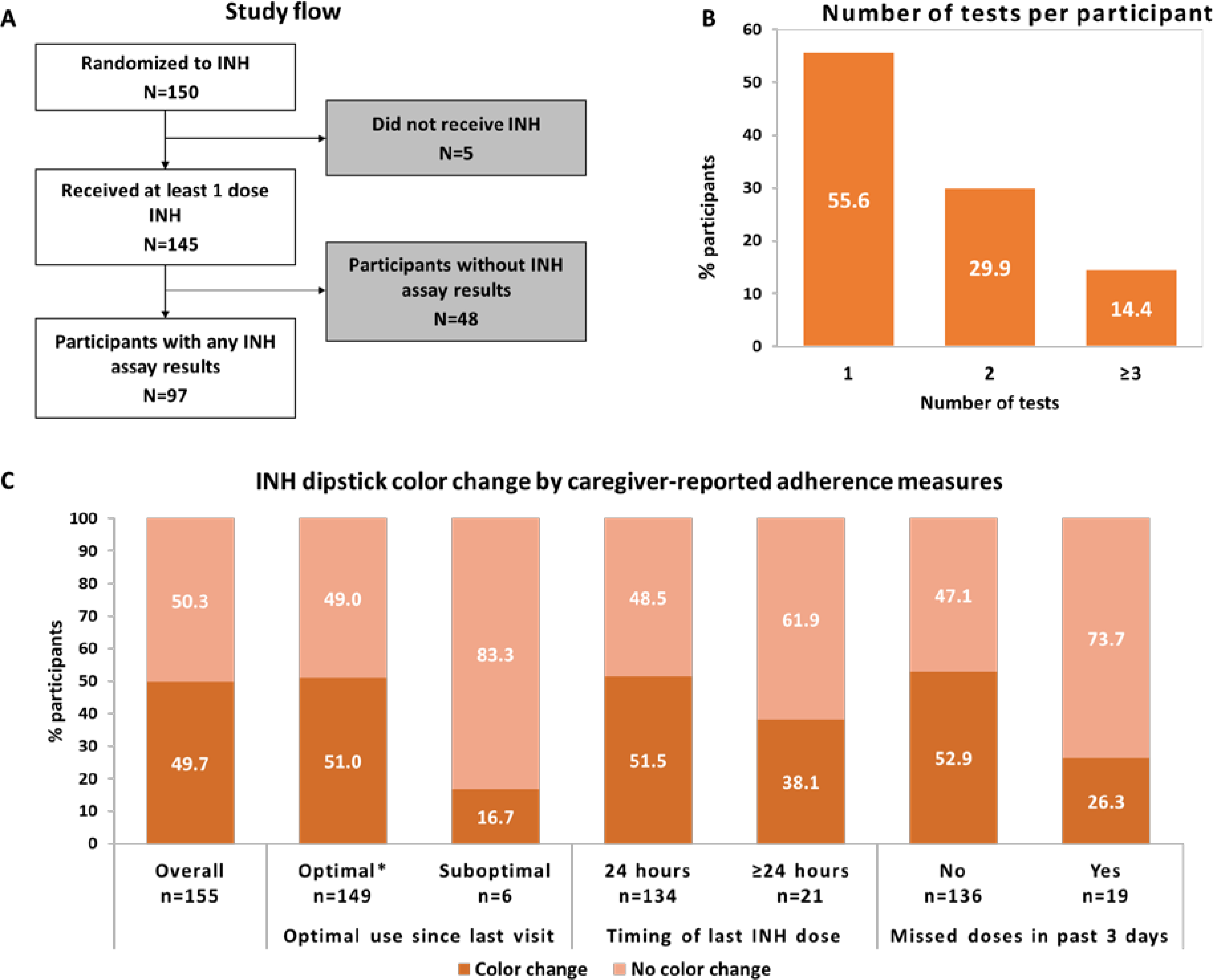

In the parent trial, 150 HIV-exposed infants were randomized to INH; 145 received at least one dose. Ninety-seven of 145 infants (67%) had 155 urine tests performed (Figure 1, Panels A & B). Among 97 infants with urine results, median enrollment age was 6.3 weeks (IQR 6.0–6.4) and 56 (57.7%) were male (see supplementary table 3). On enrollment all mothers had received antiretroviral therapy (ART) and 83 (93.3%) had HIV viral load (VL) <1000 copies/ml. Seventy-three mothers (75.3%) had ever received programmatic IPT (26 [37.0%] current use), 10 (10.3%) reported TB history, and 43 (44.3%) initiated secondary education.

Figure 1. Urine biomarker testing for isoniazid (INH) adherence among infants in a primary TB infection prevention trial in Kenya.

Panel A: Study flow. Panel B: Number of tests per participant. Panel C: INH dipstick color change by caregiver-reported adherence measures. *≥ 90% reported adherence since last study visit.

Among 155 INH metabolite assays performed, 77 (49.7%) were positive (see Figure 1, Panel C; see supplementary table 4). Overall, median caregiver-reported time since last INH dose was 15.1 hours (IQR 5.0–17.1) with 134 (86.5%) taken <24 hours since urine testing (see supplementary table 3). Dipstick results by caregiver-reported adherence measures by visit are shown in supplementary table 5 (table). Median caregiver-reported time since last INH dose was 14.5 hours (IQR 4.6–16.3) among infants with a positive urine INH assay vs. 15.5 hours (IQR 6.3–17.5) (p=0.04) for those with a negative result. Urine tests were positive in ~50% of infants with maternal-reported optimal INH use (≥90% pills taken since last visit) (76/149), INH taken <24 hours (69/134), or no missed doses past 3 days (72/136) (Figure 1, Panel C). Positive urine INH test was associated with increased infant weight-for-age Z score (RR 1.3 [95%CI 1.1–1.6, p=0.002]), maternal secondary education (RR 1.5 [95%CI 1.1–2.2, p=0.02]), maternal HIV VL <1000 copies/ml (RR 2.1 [95%CI 1.1–4.0], p=0.02]), and no missed doses past 3 days (RR 2.4 [95%CI 1.0–5.6], p=0.05) (see supplementary table 3). There was a trend for caregiver-reported last dose <24 hours (vs. >48 hours, RR 4.9 [95% CI 0.8–28.9], p=0.08) and positive urine INH result. Infant sex, age at visit, time since enrollment, and maternal history of TB or IPT were not associated with biomarker-confirmed adherence.

Fifteen urine samples were tested concurrently with the commercial IsoScreen test. Among 8 IsoScreen positive samples, 7 were positive by the in-house dipstick (sensitivity 87.5%); among 7 negative IsoScreen tests, 6 in-house dipsticks were negative (specificity 85.7%) (see supplementary table 6). Overall agreement was 86.7% (kappa 0.73, p=0.002). Similar to the whole cohort, IsoScreen results were positive in ~50–60% of children with caregiver-reported optimal INH use, INH taken in past 24 hours, or no missed doses past 3 days (see supplementary table 7).

Discussion

In our study, urine biomarker assessment suggested over-reported infant isoniazid adherence in a primary TB infection prevention trial in Kenya. A low-cost urine dipstick assay performed reasonably well compared to a more expensive commercially available test. Although the assay did not strongly correlate with caregiver report of >90% adherence between study visits, there was a significant 2.4-fold increased likelihood of positive tests among infants who reportedly missed no doses in past 3 days and a trend for >4-fold increased likelihood of positive test if last dose was received within past 24 hours. Association of maternal secondary education and HIV viral suppression with infant INH adherence suggests maternal education and success in their own medication use predicts infant adherence.

This is one of the first studies to evaluate TB prevention adherence using a biomarker approach in young infants, specifically HIV-exposed infants, a population with high risk of TB exposure and disease(8). The large proportion of infants with negative biomarker tests despite caregiver-reported adherence (~50%) may be due to or assay performance, infants not receiving doses, social desirability bias to report adherence, or infant drug metabolism characteristics. Previous urine INH biomarker evaluations have focused primarily in adults with few pediatric assessments, with non-adherence ranging from 23–35%(5, 9–15). In a Gambian evaluation among child contacts of adults with smear-positive TB (median age 2.3 years) with IsoScreen, 77% completed a 6-month course of IPT with ‘good’ adherence (consuming >80% of pills); 85% of which had a positive urine test(13). This higher biomarker-assessed adherence compared to our study could be due to parental motivation related to prophylaxis indication (primary prevention vs. known contact), younger age, or mode of IPT delivery and urine testing (IPT pickup and urine collection during study visit vs. monthly home delivery and urine collection). In our pilot testing, the urine dipstick performed well using positive controls in the lab with good diagnostic performance compared to the commercial test using clinical samples, with performance relative to commercial testing similar to previous reports(9). Previous evaluation of commercial IsoScreen reported 95% sensitivity within 24 hours of INH dose taken under direct supervision with98% specificity(12); it is possible the discrepant positive urine dipstick detected INH missed by the commercial test. In studies evaluating test performance at different time points, sensitivity of urine INH assays were lower at 24 vs. 12 hours in South African adults (77% vs. 93%, respectively)(16) and at 24 vs. 4 hours in South African children with HIV (median age 7.7 years) (78% vs. 94%, respectively)(11). Median time between reported dose and urine testing was 15 hours in our study. Metabolism differences, including acetylator status, are an unlikely explanation for low test positivity in our study; pharmacokinetic data for INH in South African HIV-exposed infants demonstrated >98% of infants achieved therapeutic levels at similar doses regardless of N-acetyltransferase 2 enzyme (NAT2) genotype(17).

Our study had limitations. Despite urine collection bags placed at each visit, many infants did not produce urine, limiting samples for biomarker testing. This could potentially be addressed by home urine collection. Urine INH metabolite testing only assesses recent adherence and may be prone to ‘white-coat’ dosing with administration before clinic visits. Hair analyses are planned, which provide a longer-term objective measure but require significant lab infrastructure/expertise and do not provide real-time results. We did not supervise INH dosing or repeat urine testing after administration, which would have allowed direct evaluation at different time points. Study visits were aligned with routine outpatient infant follow-up and caregivers were encouraged to give infants INH at the same time daily. This study represented initial prototype testing; there are ongoing evaluations of next generation INH dipsticks in other settings and contexts (South Africa, Argentina, and Kenya), including direct comparisons with the commercially available test in children living with HIV receiving IPT, and planned evaluation in cohorts receiving combine INH and rifapentine for TB prevention which will further inform test characteristics.

Point-of-care biomarker monitoring may be useful to assess and motivate infant TB prevention medication adherence. Further evaluation is needed regarding whether the newer generation of assays have improved performance in this population and whether a biomarker-based intervention such as urine adherence testing can improve TB prevention outcomes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

This study is funded by the Thrasher Research Fund. We would like to acknowledge the iTIPS Study Clinic Staff, the Kisumu and Siaya County Directors of Health, health facility staff, UW-Kenya and Kenyatta National Hospital Research and Programs operational staff. We thank the University of Washington Global Center for the Integrated Health of Women, Adolescents, and Children (Global WACh) for comments and insights provided during study design and manuscript development. We appreciate the editorial advice from Adrienne Shapiro and Sarah Iribarren. Most of all, we thank the families who have participated in the study.

Funding: This work was supported by the Thrasher Research Fund, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences at National Institutes of Health (NIH) (Thrasher to GJS, NIH/NIAID K23AI120793 to SML, and NIH UL1TR000423 for REDCap). The funders had no role in the design, collection of data, data analysis, interpretation, or decision to submit the manuscript to this journal.

Funding: Thrasher Research Fund, USA

FUNDING: This work was supported by the Thrasher Research Fund, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences at National Institutes of Health (NIH) (Thrasher to GJS, NIH/NIAID K23AI120793 to SML, NIH/NIAID 2K24AI137310 to TRH, and NIH UL1TR000423 for REDCap). The funders had no role in the design, collection of data, data analysis, and interpretation or decision to submit the manuscript to this journal.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dodd PJ, Gardiner E, Coghlan R, Seddon JA. Burden of childhood tuberculosis in 22 high-burden countries: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e453–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martinez L, Cords O, Horsburgh R, Andrews JR, Pediatric TB Contact Studies Consortium. The risk of tuberculosis in children after close exposure: a systematic review and individual-participant meta-analysis. Lancet. 2020;395:973–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ayieko J, Abuogi L, Simchowitz B, Bukusi EA, Smith AH, Reingold A. Efficacy of isoniazid prophylactic therapy in prevention of tuberculosis in children: a meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.LaCourse SM, Richardson BA, Kinuthia J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of isoniazid to prevent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in Kenyan HIV-exposed uninfected infants. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szakacs TA, Wilson D, Cameron DW, et al. Adherence with isoniazid for prevention of tuberculosis among HIV-infected adults in South Africa. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soobratty MR, Whitfield R, Subramaniam K, et al. Point-of-care urine test for assessing adherence to isoniazid treatment for tuberculosis. European Respiratory Journal. 2014;43:1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guerra RL, Conde MB, Efron A, et al. Point-of-care Arkansas method for measuring adherence to treatment with isoniazid. Respir Med. 2010;104:754–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cotton MF, Schaaf HS, Lottering G, et al. Tuberculosis exposure in HIV-exposed infants in a high-prevalence setting. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12:225–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meissner PE, Musoke P, Okwera A, Bunn JE, Coulter JB. The value of urine testing for verifying adherence to anti-tuberculosis chemotherapy in children and adults in Uganda. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2002;6:903–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eidlitz-Markus T, Zeharia A, Baum G, Mimouni M, Amir J. Use of the urine color test to monitor compliance with isoniazid treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. Chest. 2003;123:736–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amlabu V, Mulligan C, Jele N, et al. Isoniazid/acetylisoniazid urine concentrations: markers of adherence to isoniazid preventive therapy in children. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18:528–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kendall EA, Durovni B, Martinson NA, et al. Adherence to tuberculosis preventive therapy measured by urine metabolite testing among people with HIV. AIDS. 2020;34:63–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egere U, Sillah A, Togun T, et al. Isoniazid preventive treatment among child contacts of adults with smear-positive tuberculosis in The Gambia. Public Health Action. 2016;6:226–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perry S, Hovell MF, Blumberg E, et al. Urine testing to monitor adherence to TB preventive therapy. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:235–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mueller Y, Mpala Q, Kerschberger B, et al. Adherence, tolerability, and outcome after 36 months of isoniazid-preventive therapy in 2 rural clinics of Swaziland: A prospective observational feasibility study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e7740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanifa Y, Mngadi K, Lewis J, Fielding K, Churchyard G, Grant AD. Evaluation of the Arkansas method of urine testing for isoniazid in South Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007;11:1232–1236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiser JJ, Zhu R, DʼArgenio DZ, et al. Isoniazid pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and dosing in South African infants. Ther Drug Monit. 2012;34:446–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.