Abstract

Quantitative imaging biomarkers (QIBs) derived from MRI techniques have the potential to be used for the personalised treatment of cancer patients. However, large-scale data are missing to validate their added value in clinical practice. Integrated MRI-guided radiotherapy (MRIgRT) systems, such as hybrid MRI-linear accelerators, have the unique advantage that MR images can be acquired during every treatment session. This means that high-frequency imaging of QIBs becomes feasible with reduced patient burden, logistical challenges, and costs compared to extra scan sessions. A wealth of valuable data will be collected before and during treatment, creating new opportunities to advance QIB research at large. The aim of this paper is to present a roadmap towards the clinical use of QIBs on MRIgRT systems. The most important need is to gather and understand how the QIBs collected during MRIgRT correlate with clinical outcomes. As the integrated MRI scanner differs from traditional MRI scanners, technical validation is an important aspect of this roadmap. We propose to integrate technical validation with clinical trials by the addition of a quality assurance procedure at the start of a trial, the acquisition of in vivo test-retest data to assess the repeatability, as well as a comparison between QIBs from MRIgRT systems and diagnostic MRI systems to assess the reproducibility. These data can be collected with limited extra time for the patient. With integration of technical validation in clinical trials, the results of these trials derived on MRIgRT systems will also be applicable for measurements on other MRI systems.

Keywords: Biomarkers, Magnetic resonance imaging, Radiotherapy, Image-guided, Multicentre study

1. Introduction

Parameters derived from quantitative MRI (qMRI) techniques are used to assess tumour morphology, biology and function. Therefore, they are promising quantitative imaging biomarkers (QIBs) for personalised treatment of cancer patients [1]. The currently most investigated examples are the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) derived from diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and parameters derived from dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) MRI, such as Ktrans. ADC reflects tissue cell density, whereas parameters derived from DCE-MRI reflect the perfusion and vascular permeability of the tissue micro-environment. Unfortunately, most evidence is based on analysis of small patient cohorts originating from one or a few expert centres, leaving a translational gap [1,2]. Multicentre clinical trials are a critical next step to validate QIBs. One of the challenges in such trials is the reproducibility of the QIB values, attributed to the variation in acquisition protocols on different platforms and in data analysis methods. Many working groups have initiated programs to tackle this challenge [3]. Practical issues, such as the costs and burden for the patient involved with extra scanning sessions also hurt the feasibility of conducting multicentre clinical trials.

MRI-guided radiotherapy (MRIgRT) systems, such as hybrid MRI-linear accelerators, have been introduced clinically to enable personalised radiotherapy [4,5]. With MR guidance, the tumour and surrounding normal structures can be visualised just before and during treatment delivery, resulting in potentially more accurate targeting of the tumour [6]. As patients will be imaged with an MRI at every treatment session, high-frequency measurements of QIBs become feasible (Fig. 1). Such frequent imaging, occurring as often as daily, is unprecedented in the QIB research history. A wealth of valuable data can be collected during treatment, creating new opportunities to advance clinical oncological research. For radiotherapy, this opens the door to personalisation of the treatment based on changes seen in QIB values during treatment [6,7].

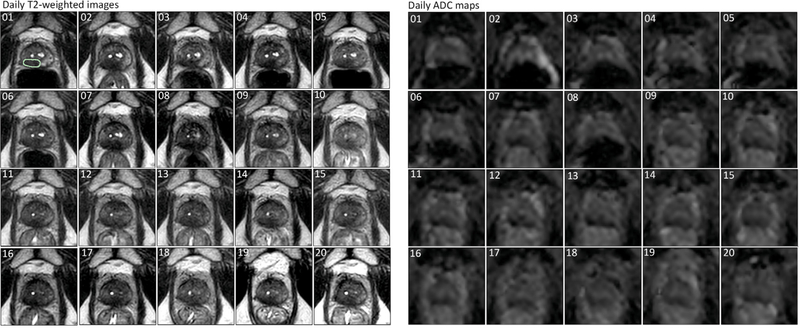

Fig. 1.

Example of daily imaging on an MRIgRT system. T2-weighted images and ADC maps are shown for a patient with prostate cancer who received 20 fractions of 3 Gy on the Unity system. The numbers in the corners indicate the fraction numbers. The green line in the first fraction of the T2-weighed image represents the tumour delineation. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

To make optimal use of the unique opportunity that MRIgRT systems offer for QIB research at large, we need to ensure that the results of clinical trials on MRIgRT systems are generalisable outside the MRIgRT domain. To this end, the values from qMRI metrics from MRIgRT systems should be comparable to those from traditional diagnostic systems. In addition, to advance QIB development for adaptive radiotherapy, it is important that qMRI values over time are reliable. Therefore, technical validation should be an important aspect in the next generation of clinical trials. This study describes the potential applications of QIBs for radiotherapy and presents a roadmap towards the clinical use of QIBs on MRIgRT systems.

2. Potential applications of QIBs in radiotherapy

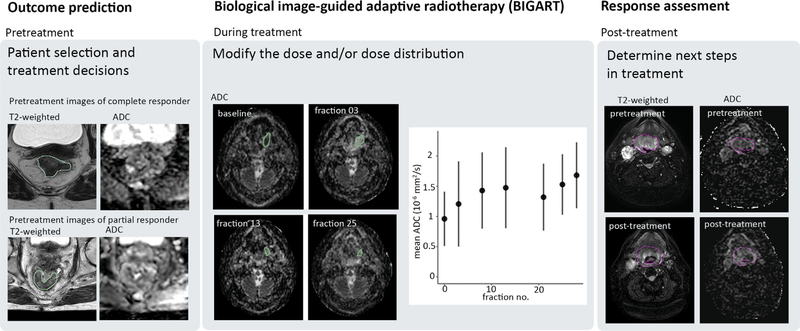

In the imaging biomarker roadmap for oncology proposed by O’Connor et al. QIBs are classified as screening QIBs, diagnostic QIBs and prognostic and predictive QIBs [1]. From those types, prognostic and predictive QIBs are the most relevant for further personalisation of radiotherapy as they have a direct relation with treatment outcome. The application of QIBs in radiotherapy can be further divided into three main categories applied during different phases of radiotherapy treatment: outcome prediction from pretreatment imaging, response assessment at the completion of radiotherapy, and biological image-guided adaptive radiotherapy (BIGART) during treatment (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

QIBs can be used during all phases of radiotherapy treatment: outcome prediction based on pretreatment or early treatment data, during treatment to adapt based on biological imaging information (BIGART), and post-treatment to assess the response after treatment. Example images are shown of patients treated on the Unity system.

The vast majority of clinical studies have focused on the potential of pretreatment imaging to predict outcomes [8,9], but also early changes in qMRI metrics have been promoted as potentially predictive for treatment outcome [10,11]. Pretreatment measurements are mostly done on diagnostic MR systems or MR simulation scanners used in radiation oncology. They can also be acquired on MRIgRT systems on the first treatment day, just before the start of irradiation. Early response measurements typically require extra scan sessions and with the availability of MRIgRT systems, the opportunity exists to collect this data without additional visits of the patient. Daily QIB measurements allow tracking changes in QIB values and determining the optimal time points for early response prediction.

Response assessment based on post-treatment images after completion of the radiation treatment can be used to determine the next steps in a patient’s treatment [11]. This is especially useful for combined treatment strategies. For example, in rectal cancer, a distinction based on QIB cutoff values between complete pathological responders and non-responders will help to select the patients that qualify for organ preservation [9].

An exciting prospect is the use of QIBs to adapt the radiation treatment in a strategy called BIGART [6]. This might involve escalating or de-escalating the intensity of the treatment by modifying the number of treatment fractions and/or total dose to the tumour. An even more sophisticated implementation of BIGART would be to modulate the dose distribution using the spatial information in QIB maps. For example, the dose can be escalated for radioresistant subregions identified with QIB maps (i.e. dose painting) [12]. Depending on the time scale at which the tumour characteristics change, adaptation of the dose distribution might be needed during treatment, possibly even on a daily basis. MRIgRT systems have the potential to bring BIGART into clinical practice, as they have the capability to adapt treatments during each fraction.

3. Clinical validation

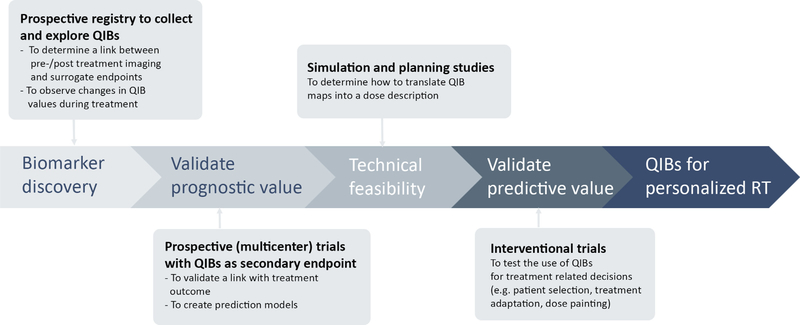

Clinical validation describes the clinical trials that are necessary to validate the link between a potential QIB and clinical application [1]. The exact path of clinical validation depends on the amount of previous research available from other MR systems for the qMRI metric and the specific application. Fig. 3 shows a general timeline.

Fig. 3.

Timeline for clinical trials going from biomarker discovery to QIBs for personalised RT in clinical practice.

Currently, most evidence is available for outcome prediction and response assessment to therapy. Although meta-analysis studies have been performed [8,13,14], the clinical validation of potential QIBs remains in its infancy. Establishing the link between qMRI metrics and clinical outcome, such as overall survival and disease-free survival, is very time consuming. Therefore, potential QIBs might be selected based using surrogate end-points measured at the conclusion of radiation treatment such as tumour regression. The formation of large-scale databases to collect multicentre data with fixed reported clinical items is crucial to explore potential QIBs, for example MOMENTUM registry [15]. With data from prospective trials prediction models can be built and validated. Interventional trials are necessary to test the use of these prediction models during clinical decision-making.

To select promising QIBs for BIGART, we first need to identify with observational studies which qMRI metrics demonstrate changes during radiotherapy as not much data are available on a daily basis [16]. The next step is to understand how these changes correlate with treatment outcome. To generate more specific hypotheses on how potential QIBs can be used for treatment adaptation, we need to know the time point at which the changes happen and whether they occur at tumour or at subregion level. An important, but still uninvestigated next step is to determine the most suitable approaches for the translation of the QIB maps into dose plans. Note that, the dose distributions will be patient specific. Therefore, the tolerance of how far the dose can be pushed will be different for each patient. Planning and simulation studies with retrospective data are necessary to assess the technical feasibility of these approaches. Finally, the efficacy of QIB-based treatment adaptation should be assessed with interventional trials [17].

4. Technical validation

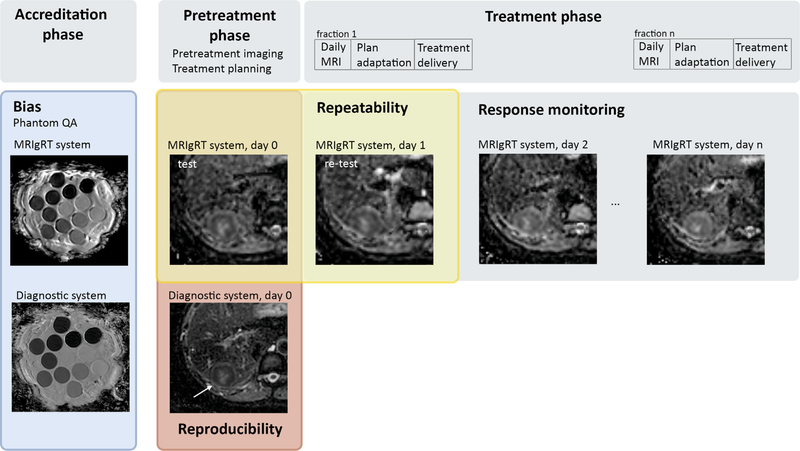

The success of potential QIBs depends on the technical confidence of the measurements, which is determined by the accuracy, repeatability and reproducibility of the measurements across institutes and over time [1]. Pilot studies have shown that quantitative imaging is feasible on commercial MRIgRT systems [18,19]: MRIdian (ViewRay Technologies Inc., Ohio) [20] and Unity (Elekta AB, Sweden) [21]. The design of the MRI scanner was adjusted to allow its integration with a linac head and a gantry system for simultaneous imaging and irradiation. The lower signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) must be considered during the development of acquisition protocols. Fig. 4 shows the integration of technical validation with clinical trials on MRIgRT systems.

Fig. 4.

Trial design for QIB studies on MRIgRT systems with integration of technical validation. Bias can be assessed with digital or physical phantoms by adding an accreditation phase at the start of a trial. Repeatability can be assessed by performing two measurements before the start of treatment (test-retest). The burden for the patient can be limited when the QIB measurements for the retest data are performed in the MR idle time of the first fraction before the actual treatment delivery. To assess the reproducibility on multiple systems, the test data of the MRIgRT system and the pretreatment imaging on a diagnostic scanner can be used. No extra scan session is needed for this comparison if test-retest data have already been acquired. The examples in this figure are ADC maps acquired from a patient with liver metastases treated on a 1.5T MRIgRT system (Unity). The diagnostic images were acquired on a 3T system. Phantom images are from the QIBA diffusion phantom.

Calibration phantoms are used to assess the bias of QIB values with respect to their true values [22,23]. First phantom studies have shown that for example ADC mapping can be done accurately on MRIgRT systems [18,24]. By including a quality assurance procedure with synthetically generated data or physical phantoms before the start of a clinical trial, the bias can be determined and potentially reduced by qMRI protocol optimisation and standardisation across participating institutes [25,26] (Fig. 3). Quality assurance should always be repeated after major changes to the MR system (upgrades, repairs).

Repeatability is determined with test-retest studies to give an estimation of the consistency of the QIB values over time, such that real changes in QIB values can be separated from measurement errors and noise [23,27]. Ideally, the time between the test and retest measurements should be short (i.e. days) to satisfy the assumption that the tissue characteristics do not change between the two measurements. On MRIgRT systems, test-retest scans can easily be integrated in a clinical trial (Fig. 3). For example, the test measurements on the MRIgRT system can be scheduled on the same day as the routine pretreatment MRI examination. The retest measurements can be done right before irradiation on the day of the first treatment fraction.

A good reproducibility, i.e., the degree to which QIB values from different systems can be compared, increases the clinical utility of a QIB. Reproducibility is an important aspect of multicentre clinical trials, but also when pretreatment measurements are done on a different system than the measurements during treatment. Efforts to develop consensus qMRI protocols will improve reproducibility among participating institutes [23,28]. Reproducibility of the acquisition can partly be assessed with the phantom-based quality assurance when performed on multiple systems [23]. Phantoms typically have higher SNR than patients and lack tissue complexity. Therefore, reproducibility should also be assessed in vivo. This can be achieved by comparing the QIB values from the pretreatment imaging session on a diagnostic platform with the pretreatment (i.e. test) measurements on an MRIgRT system (Fig. 3). Apart from data acquisition, variation in data analysis is another source affecting multicenter reproducibility [29]. For clinical trials during the early phases of development, such as biomarker discovery studies, centralised analysis of the data will maximise reproducibility. However, for interventional trials where the imaging results are used to adapt the treatment online, decentralised analysis is required. In this case, an accreditation phase is needed with digital reference objects, patient examples distributed, and contouring and analysis guidelines.

5. Discussion

MRIgRT systems offer the key advantage that integration of qMRI with the treatment is easy from a logistical and patient burden perspective. To make optimal use of this opportunity, the results of clinical trials should be generalised to other MRI platforms. Therefore, technical validation should be integrated in clinical trials. This can be achieved by performing quality assurance with phantoms before the start of a trial and adding an extra scan session on an MRIgRT system. With this extra scan session, patient test-retest data will be collected to assess the repeatability. In addition, this enables to assess the reproducibility between MRIgRT systems and diagnostic MRI scanners. In this way, the burden for the patient is limited to one extra scan session. The most important need for the next generation of clinical trials is to understand how the QIBs collected during treatment correlate with clinical outcome. Although the current focus is on DWI and DCE-derived metrics, the outline for clinical and technical validation are general and also apply for newer potential QIBs, such as chemical exchange saturation transfer imaging (CEST) [30].

The success of a QIB is also determined by the availability of a QIB in both expert and non-expert centres [1]. For example, QIBs using standard imaging techniques that are available on clinical MRIgRT systems are more likely to be scalable than imaging techniques that require additional research options or non-standard sequences. Similarly, QIBs that do not require administration of a contrast agent or an intervention are more likely to be scalable than, for example, QIBs derived from DCE-MRI.

In conclusion, integrating qMRI measurements with treatment on MRIgRT systems provides a unique opportunity to advance QIB research in oncology. With integration of technical validation in clinical trials, the results of these trials derived on MRIgRT systems will also be applicable for measurements on other MRI systems.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Simon Boeke and Jonas Habrich from the University of Tübingen and Femke Peters and Anja Betgen from the Netherlands Cancer Institute for providing images for Fig. 2.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare the following financial interests/ personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Dr. van der Heide receives industry grant support from Philips Healthcare and Elekta AB and ITEA project (‘Starlit’). Dr. Fuller received/receives funding and salary support related to this project from: the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB) Research Education Programs for Residents and Clinical Fellows Grant (R25EB025787–01); the National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research Establishing Outcome Measures Award (1R01DE025248/R56DE025248) and Academic Industrial Partnership Grant (R01DE028290); National Cancer Institute (NCI) Early Phase Clinical Trials in Imaging and Image-Guided Interventions Program (1R01CA218148); an NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG) Pilot Research Program Award from the UT MD Anderson CCSG Radiation Oncology and Cancer Imaging Program (P30CA016672); and an NCI-NSF Smart Connected Health Program (R01 CA257814). Direct infrastructure support is provided to Dr. Fuller by the multidisciplinary Stiefel Oropharyngeal Research Fund of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Charles and Daneen Stiefel Center for Head and Neck Cancer and the Cancer Center Support Grant (P30CA016672) and the MD Anderson Program in Image-guided Cancer Therapy. Dr. Fuller has received direct industry grant support, in-kind support, honoraria, and travel funding from Elekta AB related to this project. Ms. McDonald receives salary and funding support from the NIH NIDCR Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (NRSA) Individual Predoctoral Fellowship (F31DE029093) and a Dr. John J. Kopchick Fellowship through the UT MD Anderson UTHealth Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].O’Connor JPB, Aboagy EO, Adams JE, Aerts HJWL, Barrington SF, Beer AJ, et al. Imaging biomarker roadmap for cancer studies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2016;14:169–86. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hockings P, Saeed N, Simms R, Smith N, Hall MG, Waterton JC, et al. MRI biomarkers. 2020. 10.1016/B978-0-12-817057-1.00002-0. liii–lxxxvi. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Keenan KE, Biller JR, Delfino JG, Boss MA, Does MD, Evelhoch JL, et al. Recommendations towards standards for quantitative MRI (qMRI) and outstanding needs. J Magn Reson Imaging 2019;49:26–39. 10.1002/jmri.26598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Das IJ, McGee KP, Tyagi N, Wang H. Role and future of MRI in radiation oncology. Br J Radiol 2019;92:20180505. 10.1259/bjr.20180505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Winkel D, Bol GH, Kroon PS, van Asselen B, Hackett SS, Werensteijn-Honingh AM, et al. Adaptive radiotherapy: the Elekta unity MR-linac concept. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol 2019; 18:54–9. 10.1016/j.ctro.2019.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hall WA, Paulson ES, van der Heide UA, Fuller CD, Raaymakers BW, Lagendijk JJW, et al. The transformation of radiation oncology using real-time magnetic resonance guidance: a review. Eur J Cancer 2019;122:42–52. 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Gurney-Champion OJ, Mahmood F, van Schie M, Julian R, George B, Philippens MEP, et al. Quantitative imaging for radiotherapy purposes. Radiother Oncol 2020;146:66–75. 10.1016/j.radonc.2020.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Zhou Q, Zeng F, Ding Y, Fuller CD, Wang J. Meta-analysis of diffusion-weighted imaging for predicting locoregional failure of chemoradiotherapy in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Mol Clin Oncol 2017:197–203. 10.3892/mco.2017.1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Schurink NW, Lambregts DMJ, Beets-Tan RGH. Diffusion-weighted imaging in rectal cancer: current applications and future perspectives. Br J Radiol 2019;92:20180655. 10.1259/bjr.20180655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Martens RM, Noij DP, Ali M, Koopman T, Marcus JT, Vergeer MR, et al. Functional imaging early during (chemo) radiotherapy for response prediction in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; a systematic review. Oral Oncol 2019;88:75–83. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Leibfarth S, Winter RM, Lyng H, Zips D, Thorwarth D. Potentials and challenges of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in radiotherapy. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol 2018;13: 29–37. 10.1016/j.ctro.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bentzen SM, Gregoire V. Molecular imaging-based dose painting: a novel paradigm for radiation therapy prescription. Semin Radiat Oncol 2011;21:101–10. 10.1016/j.semradonc.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chung SR, Choi YJ, Suh CH, Lee JH, Baek JH. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging for predicting response to chemoradiation therapy for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review. Korean J Radiol 2019;20:649–61. 10.3348/kjr.2018.0446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Schreuder SM, Lensing R, Stoker J, Bipat S. Monitoring treatment response in patients undergoing chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced uterine cervical cancer by additional diffusion-weighted imaging: a systematic review. J Magn Reson Imaging 2015;42:572–94. 10.1002/jmri.24784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].de Mol van Otterloo SR, Christodouleas JP, Blezer ELA, Akhiat H, Brown K, Choudhury A, et al. The MOMENTUM study: an international registry for the evidence-based introduction of MR-guided adaptive therapy. Front Oncol 2020;10. 10.3389/fonc.2020.01328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].van Houdt PJ, Yang Y, van der Heide UA. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging for biological image-guided adaptive radiotherapy. Front Oncol 2021;10:1–9. 10.3389/fonc.2020.615643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Verkooijen HM, Kerkmeijer LGW, Fuller CD, Huddart R, Faivre-Finn C, Verheij M, et al. R-IDEAL: a framework for systematic clinical evaluation of technical innovations in radiation oncology. Front Oncol 2017;7:1–7. 10.3389/fonc.2017.00059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kooreman ES, van Houdt PJ, Nowee ME, van Pelt VWJ, Tijssen RHN, Paulson ES, et al. Feasibility and accuracy of quantitative imaging on a 1.5 T MR-linear accelerator. Radiother Oncol 2019;133:156–62. 10.1016/j.radonc.2019.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Yang Y, Cao M, Sheng K, Gao Y, Chen A, Kamrava M, et al. Longitudinal diffusion MRI for treatment response assessment: preliminary experience using an MRI-guided tri-cobalt 60 radiotherapy system. Med Phys 2016;43:1369–73. 10.1118/1.4942381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Klüter S. Technical design and concept of a 0.35 T MR-Linac. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol 2019;18:98–101. 10.1016/j.ctro.2019.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lagendijk JJW, Raaymakers BW, van Vulpen M. The magnetic resonance imaging-linac system. Semin Radiat Oncol 2014;24: 207–9. 10.1016/j.semradonc.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Tofts PS. QA: quality assurance, accuracy, precision and phantoms. In: Tofts PS, editor. Quantitative MRI of the Brain: Measuring Changes caused by Disease John Wiley & Sons; 2003. p. 55–81. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Shukla-Dave A, Obuchowski NA, Chenevert TL, Jambawalikar S, Schwartz LH, Malyarenko D, et al. Quantitative imaging biomarkers alliance (QIBA) recommendations for improved precision of DWI and DCE-MRI derived biomarkers in multicenter oncology trials. J Magn Reson Imaging 2019;49: e101–21. 10.1002/jmri.26518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Gao Y, Han F, Zhou Z, Cao M, Kaprealian T, Kamrava M, et al. Distortion-free diffusion MRI using an MRI-guided Tri-Cobalt 60 radiotherapy system: sequence verification and preliminary clinical experience. Med Phys 2017;44:5357–66. 10.1002/mp.12465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].van Houdt PJ, Kallehauge JF, Tanderup K, Nout R, Zaletelj M, Tadic T, et al. Phantom-based quality assurance for multicenter quantitative MRI in locally advanced cervical cancer. Radiother Oncol 2020;153:114–21. 10.1016/j.radonc.2020.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ford J, Dogan N, Young L, Yang F. Quantitative radiomics: impact of pulse sequence parameter selection on MRI-based textural features of the brain. Contrast Media Mol Imaging 2018;2018:1–9. 10.1155/2018/1729071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Paudyal R, Konar AS, Obuchowski NA, Hatzoglou V, Chenevert TL, Malyarenko DI, et al. Repeatability of quantitative diffusion-weighted imaging metrics in phantoms, head-and-neck and thyroid cancers: preliminary findings. Tomogr (Ann Arbor, Mich) 2019;5:15–25. 10.18383/j.tom.2018.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kooreman ES, van Houdt PJ, Keesman R, Pos FJ, van Pelt VWJ, Nowee ME, et al. ADC measurements on the Unity MR-linac – a recommendation on behalf of the Elekta Unity MR-linac consortium. Radiother Oncol 2020;153:106–13. 10.1016/j.radonc.2020.09.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Coolens C, Driscoll B, Foltz W, Svistoun I, Sinno N, Chung C. Unified platform for multimodal voxel-based analysis to evaluate tumour perfusion and diffusion characteristics before and after radiation treatment evaluated in metastatic brain cancer. Br J Radiol 2019;92:1–8. 10.1259/bjr.20170461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Chan RW, Chen H, Myrehaug S, Atenafu EG, Stanisz GJ, Stewart J, et al. Quantitative CEST and MT at 1.5T for monitoring treatment response in glioblastoma: early and late tumor progression during chemoradiation. J Neuro Oncol 2020. 10.1007/s11060-020-03661-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]